Abstract

The incorporation of difluoromethylene (CF2) group into chemical molecules often imparts desirable properties such as lipophilicity, binding affinity, and thermal stability. Consequently, the increasing demand for gem-difluoroalkylated compounds in drug discovery and materials science has continued to drive the development of practical methods for their synthesis. However, traditional synthetic methods such as deoxofluorination often confront challenges including complicated substrate synthesis sequences and poor functional group compatibility. In this context, we herein report a metal electron-shuttle catalyzed, modular synthetic methodology for difluoroalkylated compounds by assembling two C(sp3) fragments across CF2 unit in a single step. The approach harnesses a difluoromethylene synthon as a biradical linchpin, achieving the construction of two C(sp3)-CF2 bonds through radical addition to two different π-unsaturated molecules. This catalytic protocol is compatible with broad range of coupling partners including diverse olefins, iminiums, and hydrazones, supporting endeavors in the efficient construction of C(sp3)-rich difluoroalkylated molecules.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Homogeneous catalysis

The difluoromethylene subunit can confer advantageous biological properties to compounds of interest, and the incorporation of this moiety in mild and selective conditions is an active pursuit in synthetic organic chemistry. Here, the authors append a CF2 biradical synthon to two carbon units via cobalt catalysis.

Introduction

Difluoroalkylated compounds are ubiquitous and widely found in materials science, agrochemicals, and pharmaceuticals, such as lubiprostone, gemcitabine, and various 5-HT1D agonists1 (Fig. 1a). The strategic replacement of methylene and oxygen moieties with the difluoromethylene (CF2) fragment in drug molecules often endows them with improved structural and physicochemical properties2–5. Motivated by the demand for new fluorinated modules for medicinal chemistry, therefore, the development of efficient methods for providing difluoroalkylated compounds is one of the key tasks of organic synthesis6–9. Traditional synthetic methods for difluoroalkylated compounds often rely on laborious functional-group manipulation sequences such as deoxofluorination10, however, the harsh reaction conditions and complicated substrate synthesis protocols have significantly limited their practical use (Fig. 1b). To overcome these limitations, some innovations in synthetic methodology have been developed, focusing on the direct alkylation of CF2 synthons to flexibly assemble gem-difluorinated molecules. For instance, a series of elegant difluorocarbene transformations have been successively reported, facilitating a modular difluoroalkylation methodology with organozinc reagents/silyl enol ethers and allyl bromides as alkylating partners11–13. Moreover, a collection of refined cross-coupling methodologies utilizing olefin functionalization techniques have been crafted as new avenues to obtain gem-difluoroalkanes from BrCF2 analogs14,15. Despite these exceptional progresses, the C−CF2 bond construction methods still suffer from prominent restrictions on substrate scope and catalytic capacity when involving sp3-carbon-centered coupling agents. Thus, there is an urgent demand for novel, efficient, and robust methods to expand the diversity of difluoroalkylated compounds, especially those derived from unactivated aliphatic systems.

Fig. 1. Synthesis of difluoroalkylated compounds.

a Bioisostere design and examples of bioactive molecules containing CF2 moiety. b State-of-art on the synthesis of difluoroalkylated compounds. c Reaction design using CF2 biradical linchpin to synthesize difluoroalkylated compounds. d Radical addition tendency according to polarity matching. e This work: dialkylation of CF2 unit enabled by metal electron-shuttle catalysis. EWG electron-withdrawing group, Ar aryl, DPPBz 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphanyl)benzene.

As abundant feedstocks, alkenes, and other π-unsaturated compounds have been widely used in the radical cross-coupling reactions for constructing valuable sp3-rich carbon frameworks16–22. Recently, we have pioneered a practical and general metal electron-shuttle catalytic paradigm, successfully achieving the one-step construction of two alkyl-alkyl bonds across unactivated alkenes23,24. Building on this research, we envisioned a modular radical addition approach to introduce two alkyl moieties on both sides of the CF2 unit, aiming to synthesize functionalized difluoroalkylated compounds (Fig. 1c). By applying an easily accessible CF2 synthon as the biradical linchpin, difluoroalkyl radicals were sequentially triggered to undergo addition to unsaturated acceptors to construct two CF2−C(sp3) bonds. It is noteworthy that difluoroalkyl radicals exhibit a higher degree of steric pyramidality owing to the strong electronegativity of fluorine atoms25. This characteristic, together with the ambiphilic nature of difluoroalkyl radicals26,27, enhances their addition activity towards unsaturated bonds, which renders them compatible with an enlarged range of radical acceptors regardless of polarity matching limitations (Fig. 1d). Consequently, more extensive π-unsaturated molecules, including electron-rich or deficient olefins, iminium cations, and hydrazones, would be applicable in this transformation, amplifying molecular complexity and broadening the strategic landscape of difluoroalkylation methods.

Taking this into consideration, we herein describe a cobalt-catalyzed28,29, modular platform for the synthesis of difluoroalkylated compounds using two π-unsaturated radical acceptors and bromodifluoromethyl sulfone as the CF2 biradical synthon. As elucidated in Fig. 1e, difluoroalkyl radicals A and C are generated via Co-catalyzed single-electron transfer and Smiles rearrangement30–43 respectively, then undergo subsequent radical addition to acceptors to accomplish CF2–alkyl bonds construction. Notably, multiple radical adduct byproducts may be produced due to the presence of various radical species during the reaction process. Therefore, precisely controlling the reaction sequence by identifying an appropriate catalytic system to leverage differences in electronic property and addition reactivity of radicals is key to achieving good chemoselectivity.

Results

Reaction development and substrate scope evaluation

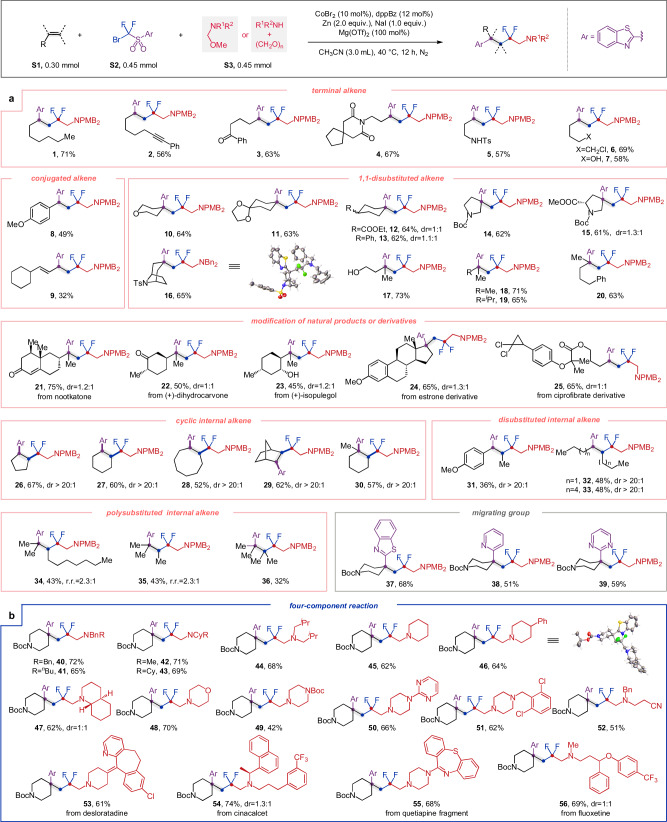

To validate the working hypothesis delineated in Fig. 1e, we started our investigations by optimizing key reaction parameters on model substrates, furnishing the desired difluoroalkylated products in good isolated yield (refer to Supplementary Material for details). The experiments were performed at 40 °C in CH3CN in the presence of Zn as reductant and CoBr2/DPPBz (1,2-bis(diphenylphosphanyl)benzene) as an electron-shuttle catalyst. Mg(OTf)2 and NaI were proved to be essential additives for the smooth progression of this reaction. With the optimized conditions in hand, we embarked on an exploration of the applicability of this protocol. The alkylation of CF2 fragment proved capable of accommodating diverse categories of alkenes (Fig. 2a). Simple 1-octene1 and alkenes bearing sensitive functional groups, including alkynyl, carbonyl, aminocarbonyl, imide, sulfamido, halide, and hydroxyl group (2 to 7), exhibited commendable performance, indicating the robustness of the catalytic system and providing ample opportunities for further derivatizations. Additionally, styrene and conjugated diene were also amenable in this reaction to deliver products 8 and 9, albeit with lower yield. Moreover, this transformation was compatible with diverse polysubstituted alkenes. For example, the reaction of exocyclic alkenes showed remarkable regioselectivity, furnishing products 10 to 16 with quaternary carbon centers constructed. The structure of product 16 was confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis (CCDC 2358855). Likewise, acyclic 1,1-disubstituted olefins were efficiently transformed into corresponding products 17 to 20 with good yields and regioselectivity. Moreover, natural products such as nootkatone(21), (+)-dihydrocarvone(22), (+)-isopulegol(23), estrone derivative(24), and ciprofibrate derivative25 could also serve as valuable templates for these transformations. Notably, cyclic alkenes with five- to eight-membered rings proved to be efficient substrates with remarkable stereo-selective control, leading to the formation of thermodynamically unfavorable cis-products (26 to 30) in good yields. Given that the 1,2-cis-disubstituted cyclic framework represents a pivotal structural motif within a wide range of molecules of pharmaceutical interest44, this stereo-specific method would enrich the synthetic toolbox available for drug discovery purposes. Disubstituted internal alkenes such as 4-octene were also amenable to the reaction, producing the desired products (31 to 33) with excellent diastereoselectivity. To our delight, this method could also be successfully applied to more sterically demanding tri- and tetra-substituted olefins (34 to 36), albeit with reduced yields. Furthermore, the scope of migratory group was also examined, revealing that other heteroaryl groups besides benzothiazolyl (37), such as pyridyl (38) and pyrimidyl (39), could be readily incorporated into the difluoroalkylated products. However, simple aryl group-substituted sulfones were not suitable for this reaction, possibly due to their sluggish reactivity for intramolecular radical addition, which resulted in a diminished rate of Smiles rearrangement.

Fig. 2. Scope of olefins, migrating groups and amines.

a Conditions: alkene S1 (0.30 mmol), bromodifluoromethyl sulfone S2 (0.45 mmol), N,O-acetal S3 (0.45 mmol) in CH3CN (3.0 mL), 40 °C, 12 h, under nitrogen atmosphere. b Conditions: alkene S1-37 (0.30 mmol), bromodifluoromethyl sulfone S2-1 (0.45 mmol), amine (0.45 mmol), paraformaldehyde (0.60 mmol) in CH3CN (3.0 mL), 40 °C, 12 h, under nitrogen atmosphere. Isolated yields after chromatography are given. Ar refers to benzothiazolyl group. DPPBz 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphanyl)benzene, Ts tosyl, Me methyl, Bn benzyl, OMe methoxy, Boc tert-butyloxycarbonyl, PMB p-methoxybenzyl, iPr isopropyl, Ph phenyl.

After examining the versatility of alkenes, we turned our attention to further exploring the range of alkylating reagents that could be applied to this transformative process. Employing a one-pot procedure by in-situ condensation of secondary amines and paraformaldehyde, we developed an effective four-component transformation for the aminomethylation reactions, resulting in the successful synthesis of compound 40 in 72% isolated yield (Fig. 2b). With this technique,

a diverse array of benzylic (40, 41), aliphatic (42–44), and cyclic (45–51) secondary amines could be readily employed, affording the desired β-difluoroalkylated amines in good yields. Moreover, electron-deficient amine (52) also displayed good reactivity under these conditions. The promising functional-group tolerance and synthetic convenience of this new protocol encouraged us to modify biologically relevant amines such as desloratadine, cinacalcet, quetiapine fragment and fluoxetine (53–56). Considering the prevalence of secondary amines in numerous pharmaceuticals and natural products, we anticipate that this approach will find widespread utility in the realm of synthetic chemistry.

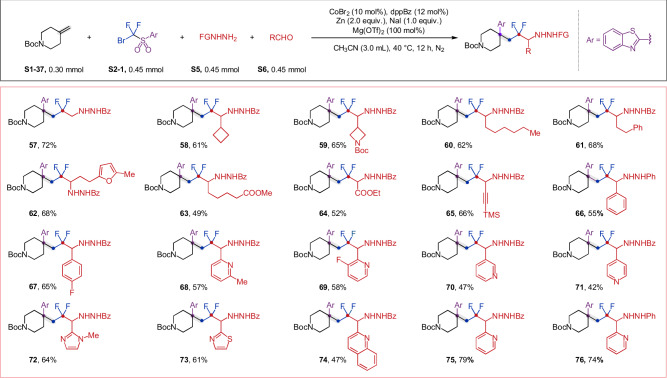

Having evaluated the scope of aminomethylation, we next sought to demonstrate the applicability of other radical acceptors in this method. As a result, an assortment of hydrazones, which were produced by a one-pot condensation of corresponding aldehydes and hydrazines, could efficiently act as coupling reagents to deliver C(sp3)-rich β-difluoroalkyl hydrazines45–47 (Fig. 3). It’s worth noting that various types of aldehydes, such as formaldehyde (57), aliphatic aldehydes (58–63), ethyl glyoxylate (64), conjugated alkynyl aldehyde (65), benzaldehydes (66, 67), and heteroaryl aldehydes (68–75) demonstrated favorable reactivity in this reaction. Additionally, hydrazines with various substituents, including benzoyl and phenyl group (76), were amenable to this transformation, ensuring the feasibility of the following modifications.

Fig. 3. Scope of hydrazones.

Conditions: alkene S1-37 (0.30 mmol), bromodifluoromethyl sulfone S2-1 (0.45 mmol), hydrazine S5 (0.45 mmol), aldehyde S6 (0.45 mmol) in CH3CN (3.0 mL), 40 °C, 12 h, under nitrogen atmosphere. Isolated yields after chromatography are given. Ar refers to benzothiazolyl group. DPPBz 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphanyl)benzene, Me methyl, Bz Benzoyl, Boc tert-butyloxycarbonyl, TMS trimethylsilyl, Ph phenyl.

To further demonstrate the versatility of the methodology, we subsequently explored a series of electron-deficient olefins as coupling partners48–52. As shown in Fig. 4, benzylidenemalononitriles bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents at the para site of phenyl groups were smoothly transformed to the corresponding products (77–84) with yields ranging from 53% to 83%. Meanwhile, difluoroalkyl malonitriles with polysubstituted benzyl or heteroaryl substituents (85–92) were also efficiently prepared. In addition, other tri-substituted electron-deficient olefins with ester or coumarin moieties successfully participated in this coupling method, affording the corresponding products (93– 96) in good yields. Surprisingly, allyl sulfones also proved to be suitable radical acceptors, resulting in the formation of the corresponding allyl products (97, 98) in moderate yields.

Fig. 4. Scope of electron-deficient olefins.

Conditions: alkene S1-37 (0.30 mmol), bromodifluoromethyl sulfone S2-1 (0.45 mmol), electron-deficient olefin S7 (0.45 mmol) in CH3CN (3.0 mL), 40 °C, 12 h, under nitrogen atmosphere. Isolated yields after chromatography are given. Ar refers to benzothiazolyl group. DPPBz 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphanyl)benzene, EWG electron-withdrawing group, PhSO2 benzenesulfonyl, Me methyl, Boc tert-butyloxycarbonyl, Ph phenyl.

Mechanistic investigations

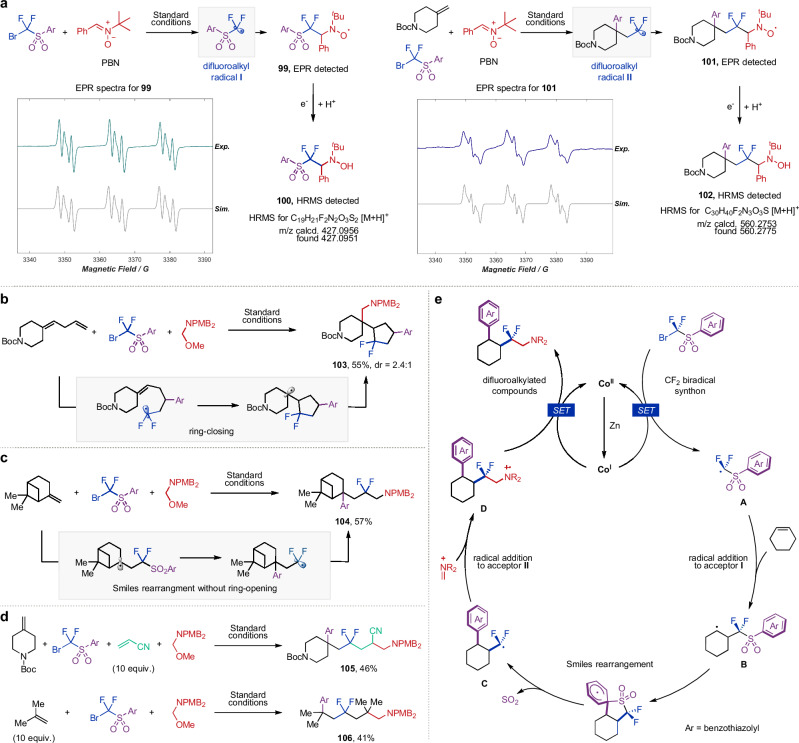

We next conducted a series of experiments to gain insights into the reaction mechanism. Initial investigations focused on electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spin-trapping experiments to investigate radical generation under standard conditions (Fig. 5a, refer to Supplementary Material for details). Using N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN) as the capture agent, two distinct EPR signals were observed for the reaction mixture with and without alkene, which could be ascribed to the spin adduct 99 and 101, respectively. The presence of these spin adducts was further confirmed by HRMS based on the detection of hydroxylamines 100 and 102, which were generated by the reduction of spin adducts under reductive conditions. These findings provided compelling evidence for the generation of difluoroalkyl radicals. Next, we conducted radical-clock experiment with 1,4-skipped diene as substrate, which exclusively furnished cyclopentyl product 103 in 55% yield via radical cyclization, confirming the involvement of a radical pathway in this reaction (Fig. 5b). Correspondingly, another radical-clock experiment with β-pinene yielded product 104 without ring opening, suggesting that the radical Smiles rearrangement is faster than the ring opening of cyclobutyl group53 (Fig. 5c). Moreover, by adjusting the concentration of radical acceptors to regulate the radical addition rate, we could incorporate multiple alkene fragments into difluoroalkylated products. In the presence of an excess amount of acrylonitrile or isobutene, cascade radical addition products 105 and 106 could be obtained in moderate yields (Fig. 5d, refer to Supplementary Material for details). These outcomes not only further demonstrate the ambiphilic nature of difluoroalkyl radical, but also suggest ample possibilities for synthesizing C(sp3)-enriched compounds through the one-step construction of multiple alkyl−alkyl bonds. On the basis of these experimental results and our previous results23,24, a plausible reaction pathway was proposed as follows (Fig. 5e): difluoroalkyl radical A is generated via Co-catalyzed single-electron transfer under reductive condition, which undergoes subsequent olefin addition and Smiles rearrangement to generate another difluoroalkyl radical C with the concomitant formation of the first CF2–alkyl bond. Subsequently, radical acceptor II, activated by Mg(OTf)2 functioning as a Lewis acid, is capable of capturing radical C to deliver radical D and accomplish another CF2–alkyl bond construction. Intermediate D is eventually reduced by cobalt to produce the desired dialkylation product. Notably, the Smiles rearrangement proceeded via five-membered cyclic transition state ensures that reactions with cyclic alkenes can yield the thermodynamically unfavorable cis-products, which are difficult to be obtained by other methods.

Fig. 5. Mechanistic investigations.

a EPR spin-trapping experiments with experimental spectra and simulation. b Radical ring-closing experiment under standard conditions. c Radical ring-opening experiment under standard conditions. d Reactions with excess electron-deficient or electron-rich alkenes. e Proposed reaction mechanism. Ar refers to benzothiazolyl group. PBN N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone, Me methyl, Boc tert-butyloxycarbonyl, PMB p-methoxybenzyl.

Synthetic applications

To emphasize the synthetic value of this protocol, we showcased the broad scope of transforming the products into various difluoroalkylated derivatives. The benzolthiazoyl is a transformative group that enables access to other functionalities. As shown in Fig. 6a, the benzolthiazoyl in difluoroalkyl amine 1 could be smoothly converted into 2-aminobenzenethiol moiety (107), which is a key pharmacophore in drug discovery54. Moreover, an operationally simple three-step one-pot treatment of 1 enabled the preparation of corresponding aldehyde 108 in good yield, which could be futher transformed into fluorinated amino acid or alcohol. Meanwhile, a large-scale experiment was performed on a 10.0 mmol scale under standard reaction conditions to yield product 109 in 62% yield (Fig. 6b). The geminal cyano groups in 109 could be converted into amide groups (110) in 88% yield, or be utilized to construct pyrazole ring (111) with hydrazine hydrate. The reductive decyanation of malononitriles, mediated by AIBN/(TMS)3SiH, proved to be effective in accessing functionalized difluoroalkylnitrile 112. Additionally, through palladium-catalyzed arylation of the cyano group with aryl boronic acid, the synthesis of aryl ketone 113 was achieved in 81% yield. These diverse synthetic transformations highlight the versatility of this synthetic methodology, which could open new avenues in the synthesis of difluoroalkylated molecules.

Fig. 6. Synthetic transformations.

a Transformations of the difluoroalkylated product 1. b Transformations of the difluoroalkylated product 109. Ar refers to benzothiazolyl group. AIBN azobisisobutyronitrile, (TMS)3SiH trimethylsilane, Ts tosyl, Ph phenyl.

Discussion

In summary, we described the development of a modular synthetic strategy for gem-difluoroalkylated compounds. With bromodifluoromethyl sulfone as a biradical linchpin, various π-unsaturated acceptors including olefins, iminium cations, and hydrazones could be employed in this transformation to construct CF2-C(sp3) bonds. We anticipate that this method will be attractive to the synthetic and medicinal chemistry communities seeking access to fluorinated molecules.

Methods

General procedure for three-component reactions

CoBr2 (6.6 mg, 10 mol%), dppBz (16.1 mg, 12 mol%), and CH3CN (3.0 mL) were added to a flame-dried Young-type tube under N2 atmosphere. The resulting mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 30 min. After that, alkene (0.30 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), alkyl bromide (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), N,O-acetal or electron-deficient olefins (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), Mg(OTf)2 (96.6 mg, 100 mol%), NaI (45 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and Zn (42.0 mg, 0.60 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were added under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was degassed with freeze-thaw method for 3 times and stirred at 40 °C for 12 h. After completion, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was quenched by saturated aq. NH4Cl (5.0 mL). The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (10 mL × 3), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the desired product.

General procedure for one-pot four-component reactions with paraformaldehyde and amines

CoBr2 (6.6 mg, 10 mol%), dppBz (16.1 mg, 12 mol%), and CH3CN (3.0 mL) were added to a flame-dried Young-type tube under N2 atmosphere. The resulting mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 30 min. Then, amine (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), paraformaldehyde (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), and Mg(OTf)2 (96.6 mg, 100 mol%) were added under N2 atmosphere. The resulting mixture was stirred at 40 °C for additional 3 h. After that, tert-butyl 4-methylenepiperidine-1-carboxylate (0.30 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2-((bromodifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)benzo[d]thiazole (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), NaI (45 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and Zn (43.2 mg, 0.60 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were added under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was degassed with freeze-thaw method for 3 times and stirred at 40 °C for 12 h. After completion, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was quenched by saturated aq. NH4Cl (5.0 mL). The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (10 mL × 3), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the desired product.

General procedure for one-pot four-component reactions with aldehydes and hydrazines

CoBr2 (6.6 mg, 10 mol%), dppBz (16.1 mg, 12 mol%), and CH3CN (3.0 mL) were added to a flame-dried Young-type tube under N2 atmosphere. The resulting mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 30 min. Then, hydrazine (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), aldehyde (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), and Mg(OTf)2 (96.6 mg, 100 mol%) were added under N2 atmosphere. After that, tert-butyl 4-methylenepiperidine-1-carboxylate (0.30 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2-((bromodifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)benzo[d]thiazole (0.45 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), NaI (45 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and Zn (43.2 mg, 0.60 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were added under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was degassed with freeze-thaw method for 3 times and stirred at 40 °C for 12 h. After completion, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was quenched by saturated aq. NH4Cl (5.0 mL). The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (10 mL × 3), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the desired product.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21925111, 92356302, 22301290, 22301289 and 22350008), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0450301) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1501003, 2023YFA1507500) (H.H.). This work was partially carried out at the Instruments Center for Physical Science, University of Science and Technology of China.

Author contributions

H.H. conceived the concept and directed the project. C.R. developed the reaction and investigated the substrate scope. C.R., T.Z. implemented mechanistic studies and synthetic transformations. C.R., T.Z. and H.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mingyou Hu, Jie Li and Fanke Meng for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the authors upon request. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, under deposition numbers CCDC 2358855 (16), 2358856 (46) and 2358857 (112). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Changqing Rao, Tianze Zhang.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51532-1.

References

- 1.Gribble, G. W. A recent survey of naturally occurring organohalogen compounds. Environ. Chem.12, 396–405 (2015). 10.1071/EN15002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huchet, Q. A. et al. Fluorination patterning: a study of structural motifs that impact physicochemical properties of relevance to drug discovery. J. Med. Chem.58, 9041–9060 (2015). 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fauber, B. P. et al. Structure-based design of substituted hexafluoroisopropanol-arylsulfonamides as modulators of RORc. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.23, 6604–6609 (2013). 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mimura, H., Kawada, K., Yamashita, T., Sakamoto, T. & Kikugawa, Y. Trifluoroacetaldehyde: a useful industrial bulk material for the synthesis of trifluoromethylated amino compounds. J. Fluor. Chem.131, 477–486 (2010). 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2009.12.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackburn, G. M. & Kent, D. E. Monofluoro- and difluoromethylenebisphosphonic acids: isopolar analogues of pyrophosphoric acid. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun.1981, 930–932 (1981). 10.1039/c39810000930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuya, T., Kamlet, A. S. & Ritter, T. Catalysis for fluorination and trifluoromethylation. Nature473, 470–477 (2011). 10.1038/nature10108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomashenko, O. A. & Grushin, V. V. Aromatic trifluoromethylation with metal complexes. Chem. Rev.111, 4475–4521 (2011). 10.1021/cr1004293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, X., Wu, T., Phipps, R. J. & Toste, F. D. Advances in catalytic enantioselective fluorination, mono-, di- and trifluoromethylation, and trifluoromethylthiolation reactions. Chem. Rev.115, 826–870 (2015). 10.1021/cr500277b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang, F., Xiao, Y.-L. & Zhang, X. Transition-metal (Cu, Pd, Ni)-catalyzed difluoroalkylation via cross-coupling with difluoroalkyl halides. Acc. Chem. Res.51, 2264–2278 (2018). 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Maharik, N. & O’Hagan, D. Organofluorine chemistry:deoxyfluorination reagents for C−F bond synthesis. Aldrichim. Acta44, 65–75 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin, V. V., Zemtsov, A. A., Struchkova, M. I. & Dilman, A. D. Reactions of difluorocarbene with organozinc reagents. Org. Lett.15, 917–919 (2013). 10.1021/ol400122k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilman, A. D. & Levin, V. V. Difluorocarbene as a building block for consecutive bond-forming reactions. Acc. Chem. Res.51, 1272–1280 (2018). 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng, X., Li, Y., Min, Q.-Q., Xue, X.-X. & Zhang, X. Copper-catalysed difluorocarbene transfer enables modular synthesis. Nat. Chem.15, 1064–1073 (2023). 10.1038/s41557-023-01236-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yue, W.-J., Day, C. S., Rucinski, A. J. B. & Martin, R. Catalytic hydrodifluoroalkylation of unactivated olefins. Org. Lett.24, 5109–5114 (2022). 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren, X., Gao, X., Min, Q.-Q., Zhang, S. & Zhang, X. (Fluoro)alkylation of alkenes promoted by photolysis of alkylzirconocenes. Chem. Sci.13, 3454–3460 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Giese, B. Formation of CC bonds by addition of free radicals to alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.22, 753–764 (1983). 10.1002/anie.198307531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo, J. C., Yabe, Y. & Baran, P. S. A practical and catalytic reductive olefin coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc136, 1304–1307 (2014). 10.1021/ja4117632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo, J. C., Gui, J., Yabe, Y., Pan, C.-M. & Baran, P. S. Functionalized olefin cross-coupling to construct carbon−carbon bonds. Nature516, 343–348 (2014). 10.1038/nature14006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crossley, S. W. M., Obradors, C., Martinez, R. M. & Shenvi, R. A. Mn-, Fe-, and co-catalyzed radical hydrofunctionalizations of olefins. Chem. Rev.116, 8912–9000 (2016). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green, S. A. et al. The high chemofidelity of metal-catalyzed hydrogen atom transfer. Acc. Chem. Res.51, 2628–2640 (2018). 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou, W., Dmitriev, I. A. & Melchiorre, P. Reductive cross-coupling of olefins via a radical pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 25098–25102 (2023). 10.1021/jacs.3c11285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarkar, S., Ghosh, S., Kurandina, D., Noffel, Y. & Gevorgyan, V. Enhanced excited-state hydricity of Pd–H allows for unusual head-to-tail hydroalkenylation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 12224–12232 (2023). 10.1021/jacs.3c02410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao, C., Zhang, T., Liu, H. & Huang, H. Double alkyl–alkyl bond construction across alkenes enabled by nickel electron-shuttle catalysis. Nat. Catal.6, 847–857 (2023). 10.1038/s41929-023-01015-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou, X., Liu, H. & Huang, H. Iron-catalyzed fluoroalkylative alkylsulfonylation of alkenes via radical-anion relay. Nat. Commun.15, 1480 (2024). 10.1038/s41467-024-45867-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernardi, F., Cherry, W., Shaik, S. & Epiotis, N. D. Structure of fluoromethyl radicals. Conjugative and inductive effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc.100, 1352–1356 (1978). 10.1021/ja00473a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsaee, F. et al. Radical philicity and its role in selective organic transformations. Nat. Rev. Chem.5, 486–499 (2021). 10.1038/s41570-021-00284-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schutter, C., Pfund, E. & Lequeux, T. Radical conjugate addition of ambiphilic fluorinated free radicals. Tetrahedron69, 5920–5926 (2013). 10.1016/j.tet.2013.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng, X. et al. Organozinc pivalates for cobalt-catalyzed difluoroalkylarylation of alkenes. Nat. Commun.12, 4366 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-24596-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, J. et al. Salt-stabilized alkylzinc pivalates: versatile reagents for cobalt-catalyzed selective 1,2-dialkylation. Chem. Sci.14, 8672–8680 (2023). 10.1039/D3SC02345A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loven, R. & Speckamp, W. N. A novel 1,4-aryl radical rearrangement. Tetrahedron Lett.13, 1567–1570 (1972). 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)84687-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monos, T. M., Mcatee, R. C. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Arylsulfonylacetamides as bifunctional reagents for alkene aminoarylation. Science361, 1369–1373 (2018). 10.1126/science.aat2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noten, E. A., Ng, C. H., Wolesensky, R. M. & Stephenson, C. R. J. A general alkene aminoarylation enabled by N-centred radical reactivity of sulfinamides. Nat. Chem.16, 599–606 (2024). 10.1038/s41557-023-01404-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hervieu, C. et al. Chiral arylsulfinylamides as reagents for visible light-mediated asymmetric alkene aminoarylations. Nat. Chem.16, 607–614 (2024). 10.1038/s41557-023-01414-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu, J., Wu, Z. & Zhu, C. Efficient docking–migration strategy for selective radical difluoromethylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 17156–17160 (2018). 10.1002/anie.201811346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, X. & Zhu, C. Radical-mediated remote functional group migration. Acc. Chem. Res.53, 1620–1636 (2020). 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, J. et al. Polarity umpolung strategy for the radical alkylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 8195–8202 (2020). 10.1002/anie.201915837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abrams, R. & Clayden, J. Photocatalytic difunctionalization of vinyl ureas by radical addition polar Truce–Smiles rearrangement cascades. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 11600–11606 (2020). 10.1002/anie.202003632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan, J. et al. A radical smiles rearrangement promoted by neutral eosin Y as a direct hydrogen atom transfer photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 11357–11362 (2020). 10.1021/jacs.0c02052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hervieu, C. et al. Asymmetric, visible light-mediated radical sulfinyl-Smiles rearrangement to access all-carbon quaternary stereocentres. Nat. Chem.13, 327–334 (2021). 10.1038/s41557-021-00668-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni, C., Hu, M. & Hu, J. Good partnership between sulfur and fluorine: sulfur-based fluorination and fluoroalkylation reagents for organic synthesis. Chem. Rev.115, 765–825 (2015). 10.1021/cr5002386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rong, J. et al. Radical fluoroalkylation of isocyanides with fluorinated sulfones by visible-light photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.55, 2743–2747 (2016). 10.1002/anie.201510533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei, J. et al. Transition-metal-free electrophilic fluoroalkanesulfinylation of electron-rich (het)arenes with fluoroalkyl heteroaryl sulfones via C(Het)−S and S=O bond cleavage. Adv. Synth. Catal.361, 5528–5533 (2019). 10.1002/adsc.201900959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou, X., Ni, C., Deng, L. & Hu, J. Electrochemical reduction of fluoroalkyl sulfones for radical fluoroalkylation of alkenes. Chem. Commun.57, 8750–8753 (2021). 10.1039/D1CC03258E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira, M. & Vale, N. Saquinavir: From HIV to COVID-19 and cancer treatment. Biomolecules12, 944 (2022). 10.3390/biom12070944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friestad, G. K. & Qin, J. Highly stereoselective intermolecular radical addition to aldehyde hydrazones from a chiral 3-amino-2-oxazolidinone. J. Am. Chem. Soc.122, 8329–8330 (2000). 10.1021/ja002173u [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen, Y. & Friestad, G. K. Comparison of electrophilic amination reagents for n-amination of 2-oxazolidinones and application to synthesis of chiral hydrazones. J. Org. Chem.67, 6236–6239 (2002). 10.1021/jo0259663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han, B. et al. Photocatalytic enantioselective α-aminoalkylation of acyclic imine derivatives by a chiral copper catalyst. Nat. Commun.10, 3804 (2019). 10.1038/s41467-019-11688-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du, Y.-D. et al. Organophotocatalysed synthesis of 2-piperidinones in one step via [1 + 2 + 3] strategy. Nat. Commun.14, 5339 (2023). 10.1038/s41467-023-40197-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo, H.-M. & Wu, X. Selective deoxygenative alkylation of alcohols via photocatalytic domino radical fragmentations. Nat. Commun.12, 5365 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-25702-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bloom, S. et al. Decarboxylative alkylation for site-selective bioconjugation of native proteins via oxidation potentials. Nat. Chem.10, 205–211 (2018). 10.1038/nchem.2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Streuff, J. & Gansäuer, A. Metal-catalyzed β-functionalization of Michael acceptors through reductive radical addition reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.54, 14232–14242 (2015). 10.1002/anie.201505231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang, H. & Studer, A. Iminyl-radicals by oxidation of α-imino-oxy acids: photoredox-neutral alkene carboimination for the synthesis of pyrrolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.56, 12273–12276 (2017). 10.1002/anie.201706270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin, J. & Newcomb, M. Rate constants and Arrhenius functions for ring opening of a cyclobutylcarbinyl radical clock and for hydrogen atom transfer from the Et3B−MeOH complex. J. Org. Chem.73, 4740–4742 (2008). 10.1021/jo800500e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shinkai, H., Maeda, K., Yamasaki, T., Okamoto, H. & Uchida, I. Bis(2-(Acylamino)phenyl) disulfides, 2-(Acylamino)benzenethiols, and S-(2-(acylamino)phenyl) alkanethioates as novel inhibitors of cholesteryl ester transfer protein. J. Med. Chem.43, 3566–3572 (2000). 10.1021/jm000224s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the authors upon request. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, under deposition numbers CCDC 2358855 (16), 2358856 (46) and 2358857 (112). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.