Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic interstitial lung disease with a high incidence of acute exacerbation and an increasing mortality rate. Currently, treatment methods and effects are limited. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of the incidence of acute exacerbation in patients with IPF, hoping to provide reference for the prevention and management of IPF. We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library and Web of Science databases. From the creation of the database to the cohort study on April 3, 2023, we collected studies on the incidence of acute exacerbation of IPF patients, and used Stata software (version 16.0) for meta analysis. We used the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) to assess the risk of bias for each study. We calculated the incidence of acute exacerbation in IPF patients and analyzed the risk factors for acute exacerbation in IPF patients and prognostic factors for overall survival from the initial IPF diagnosis. A total of ten cohort studies on the incidence of AE-IPF were included, including 11,855 IPF patients. The results showed that the incidence of acute exacerbation within one year was 9%; the incidence of acute exacerbation within 2 years is 13%; the incidence of acute exacerbation within 3 years is 19%; the incidence of acute exacerbation within 4 years is 11%. In addition, one study reported an acute exacerbation rate of 1.9% within 30 days. The incidence of acute exacerbation within ten years reported in one study was 9.8%. Mura et al.'s article included a retrospective cohort study and a prospective cohort study. The prospective cohort study showed that the incidence of acute exacerbation within 3 years was 18.6%, similar to the results of the retrospective cohort study meta-analysis. Our system evaluation and meta-analysis results show that the incidence of AE-IPF is relatively high. Therefore, sufficient attention should be paid to the research results, including the management and prevention of the disease, in order to reduce the risk of AE.

Trial registration: PROSPERO, identifier CRD42022341323.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Prevalence, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Subject terms: Diseases, Medical research

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic interstitial lung disease characterized by abnormal deposition of extracellular matrix leading to extensive lung remodeling1. Dry cough, dyspnea, progressive deterioration, and decreased lung function are the main clinical manifestations of IPF2. It mostly occurs in the elderly and has a high mortality3. The incidence rate of IPF is increasing year by year, and mortality is high. Research shows that the annual incidence rate of IPF is 6.8–16.3/100,0004, and there are about 40,000 newly diagnosed cases every year in Europe1; in Europe and North America, the estimated annual incidence rate is 2.8–18/100,000 people, and the median time from diagnosis to survival is 2–4 years5. IPF patients have a high risk of multiple comorbidities, such as lung cancer, infection, and cardiovascular disease, but the main cause of death in IPF patients is acute exacerbation6. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (AE-IPF) is rapid deterioration of lung function caused by acute lung injury that suddenly accelerates or accumulates in IPF patients7. The incidence rate of AE‑IPF can reach 1–20%, which has become the most common fatal disease of IPF patients. The proportion of short-term fatal diseases is as high as 85%, and will lead to more serious consequences8,9. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the prevention and treatment of acute exacerbation in IPF patients.

AE-IPF is a global health issue. Japanese scholars first proposed the definition and diagnostic criteria of AE-IPF in 199310. In 2007, the AE-IPF expert consensus was jointly released by international experts in the IPF field and the IPF Clinical Research Network11. With the continuous research on AE-IPF and the continuous improvement of understanding of AE-IPF, the definition and diagnostic criteria of AE-IPF were revised in 20169. This study showed that the mortality rate of IPF patients during hospitalization after acute exacerbation can reach 50%. The median survival time is 3–4 months9, and the prognosis is extremely poor. The patient's condition may continue to worsen after the first acute exacerbation, and the mortality rate can exceed 90% after six months, posing a serious challenge to clinical diagnosis and treatment. In the past two decades, with the development and revision of AE-IPF guidelines12, the emergence of new drugs and therapies has prompted the need to update epidemiological data on AE-IPF.

Although studies have found that acute exacerbation increases the risk of death in IPF patients, the literature on the incidence of AE-IPF is limited, the sample size is small, and there are differences in research cycles and types. There is still a lack of high-quality clinical research evidence to support this, and there is currently no consensus. At present, there has been a systematic evaluation on the global incidence rate and prevalence of IPF13, but there is still a lack of precise epidemiological conclusions on the evaluation of AE‑IPF incidence. In recent years, there have been new high-quality observational research reports on the evaluation of the incidence of AE-IPF. Therefore, this study systematically collected research on the incidence of AE-IPF, hoping to provide reference for the prevention and management of IPF.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines14, and the protocol has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42022341323).

Search strategy

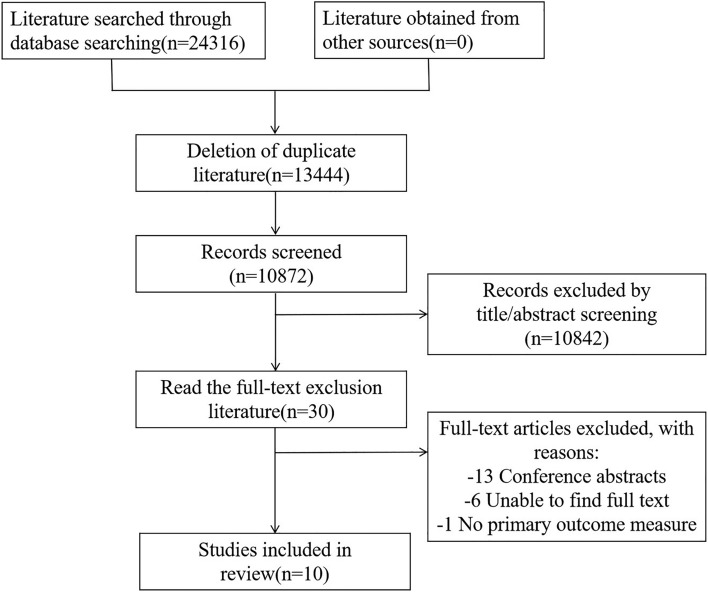

Our system searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases, and there were no language restrictions from the database creation until April 3, 2023. The search term is: "Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis" or "Acute exacerbation of Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis" or "Acute exacerbation of Idiopathic pulmonary interstitial fibrosis". During the literature selection process, relevant literature and its references were traced, and the specific search strategies are detailed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Literature selection process.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria of this study are as follows: (1) cohort study on the incidence of acute exacerbation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was included without language restrictions; (2) The exposure group was IPF patients, while the control group was non-IPF patients; (3) The main outcome measure is the incidence of acute exacerbation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for this study are as follows: (1) Repeated publications; (2) Conference abstract literature; (3) Literature that cannot extract outcome indicators; (4) Unable to obtain literature from the original text.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS)15 was used to evaluate the included literature, and the total score of each cohort study was between 0 and 9 points. A higher score indicates a higher quality of research, with scores of 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 for low, medium, and high quality, respectively.

Research selection

Two researchers (Y Wang and ZL Ji) independently searched for literature, screened literature, and extracted data based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Firstly, repetitive and unrelated literature were excluded based on the title and abstract, and relevant literature and its references were traced. For qualified literature, the full text was read one by one. When two researchers encounter disagreements, the third researcher (BC Xu) will decide until a consensus is reached.

Data extraction

The two researchers independently extracted information such as the lead author, publication time, country, research type, research time, diagnostic criteria, sample size, age, sex, conclusion indicators, risk factors, prognostic factors and other information using the pre designed form according to the guidelines for systematic evaluation and meta analysis of the preferred reporting items (PRISMA 2020)14, and cross checked them. When two researchers encounter disagreements, the third researcher (BC Xu) will decide until a consensus is reached.

Statistical analysis

Meta analysis was conducted using Stata software (version 16.0). We extracted data related to the incidence of acute exacerbation in IPF patients from the included studies. When I2 < 50%, it indicates low heterogeneity, and a fixed effects model was used; when I2 ≥ 50%, it indicates high heterogeneity, and a random effects model is used. We plan to conduct a group analysis of the incidence of acute exacerbation to determine whether it is influenced by country and gender. We used sensitivity analysis to explore the causes of heterogeneity by excluding individual studies one by one. Due to the inclusion of less than ten articles, funnel plot analysis cannot be used to determine whether there is publication bias. We summarized HR and 95% CI to evaluate the risk factors and prognostic factors for acute exacerbation in IPF patients.

Results

Search results

A total of 24,316 articles were retrieved, with 13,444 duplicate articles excluded. 10,842 irrelevant articles were excluded from the reading title and abstract. After reading the entire text, 21 articles were excluded, including 13 conference abstract articles, 1 article that could not extract outcome indicators, and 6 articles that could not obtain the original text. Finally, ten articles were included in the literature selection process, as shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of studies

A total of ten studies8,16–24 were included, of which 9 studies8,16,17,19–24 were purely retrospective cohort study, and Mura et al.'s article18 included retrospective cohort study and prospective cohort study. The data mainly comes from four countries, namely Republic of Korea, USA, Italy, and Japan, including 11,855 IPF patients, with a minimum sample size of 47 and a maximum sample size of 9961. Five studies16,18,21–23 reported on the number of males and females and median age of IPF, five studies17,19–22 reported on the number of males and females and median age of AE-IPF, and one study24 only reported on the proportion of males in IPF and AE-IPF, as well as the median age of AE-IPF, without specific values. The included studies were published from 2006 to 2022, with clear diagnostic criteria. The diagnostic criteria for three studies18–20 were the 2000 American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society criteria25, and the diagnostic criteria for three studies8,16,17 were the 2002 American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) Compensation Classification26, The diagnostic criteria for three studies21–23 were the 2011 official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement27, and the diagnostic criteria for one study24 were the 2022 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia28. Eight studies8,17–19,21–24 have clearly reported the definition for AE. The definition criteria for AE in three studies17,19,23 are based solely on an article published by Collard et al. in 200711. The definition criteria for AE in two studies22,24 are based solely on an article published by Collard et al. in 20169. A study8 reported that the definition criteria for AE are based on an article published by Kondoh et al. in 199310. A study18 reported that the definition criteria for AE are based on an article published by Akira et al. in 199729. A study21 reported that the definition criteria for AE are based on the articles published by Collard et al. in 200711 and Raghu et al. in 201127. The basic characteristics of the included study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included studies.

| References | Country | Study design | Study period | Sample size | Male/female | Mean or median age | Number of AE | Male/female of AE | Mean or median age of AE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (2006) | Republic of Korea | Retrospective | 1990–2003 | 147 | NM | NM | 11 | NM | NM |

| Fernández et al. (2010) | USA | Retrospective | 1997–2005 | 47 | 28/19 | 73.5 ± 7.8 | NM | NM | NM |

| Song et al. (2011) | Republic of Korea | Retrospective | 1990–2009 | 461 | NM | NM | 90 | 69/21 | 64.3 ± 8.9 |

| Collard et al. (2013) | USA | Retrospective | NM | 180 | NM | NM | 17 | 17/0 | Mean 71 |

| Kishaba et al. (2014) | Japan | Retrospective | 2001–2010 | 594 | NM | NM | 58 | 38/20 | 75.0 ± 9.6 |

| Kakugawa et al. (2016) | Japan | Retrospective | 1999–2014 | 65 | 51/14 | Mean 69 | 24 | 20/4 | Mean 68 |

| Okuda et al. (2019) | Japan | Retrospective | 2006–2015 | 107 | 82/25 | 66.9 ± 7.1 | 29 | 23/6 | 69.2 ± 7.7 |

| Kishaba et al. (2020) | Japan | Retrospective | 2009–2014 | 155 | 109/46 | Mean 66 | NM | NM | NM |

| Homma Sakae et al. (2022) | Japan | Retrospective | 2008–2019 | 9961 | NM | NM | 2629 | NM | Mean 74.8 |

| Mura et al. (2012) | Italy | Retrospective and prospective | 2005–2007 | 70 and 68 | 57/13 and 50/18 | 67 ± 8 and 62 ± 9 | NM | NM | NM |

Risk-of-bias assessment

We used the NOS scale to evaluate the quality of the included literature. According to the scoring criteria, all nine studies8,16–19,21–24 scored ≥ 7 points, and each of the 1–5 major studies scored 1 point, which is classified as a high-quality study; A study20 scored 6 points and was classified as a medium quality study. The overall quality of this study is relatively high, and the quality evaluation of the included studies is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality evaluation of included studies.

| References | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Scores | Overall of quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (2006) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | High |

| Fernández et al. (2010) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | High |

| Song et al. (2011) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | High |

| Mura et al. (2012) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | High |

| Collard et al. (2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | High |

| Kishaba et al. (2014) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | Moderate |

| Kakugawa et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | High |

| Okuda et al. (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | High |

| Kishaba et al. (2020) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | High |

| Homma Sakae et al. (2022) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | High |

(1) The representativeness of the exposure group; (2) selection methods for non-exposure groups; (3) the method for determining exposure factors, (4) there are no indicators to be observed before the start of the study; (5) the study controlled for the main factors; (6) the study controlled for other confounding factors; (7) evaluation of outcome events; (8) is the follow-up time long enough; (9) integrity of follow-up.

Meta-analysis results

Acute exacerbation rate within 30 days in IPF patients

Only one study23 reported an acute exacerbation rate of 1.9% within 30 days, so meta-analysis cannot be performed.

Incidence of acute exacerbation within one year in IPF patients

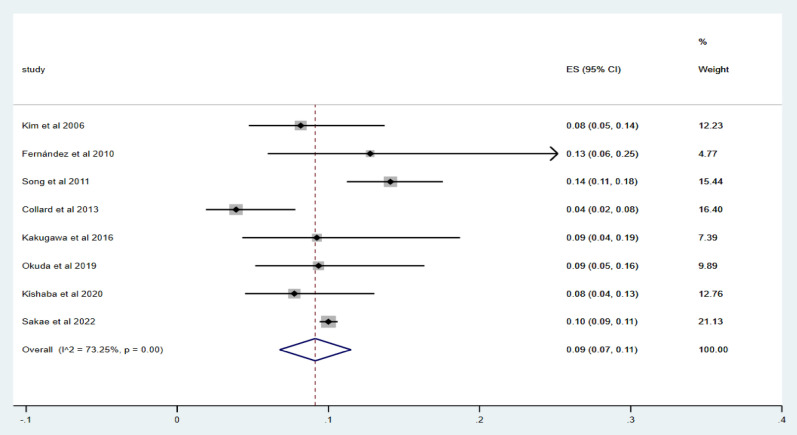

Eight studies8,16,17,19,21–24 were included to report the incidence of acute exacerbation within 1 year. Using Metoprop analysis, the incidence of acute exacerbation within 1 year in IPF patients ranged from 4 to 14%, and the overall incidence of acute exacerbation was 9% (95% CI 7–11%; I2 = 73.25%, p = 0.00), as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Forest map of the incidence of acute exacerbation within one year.

Acute exacerbation rate within 2 years in IPF patients

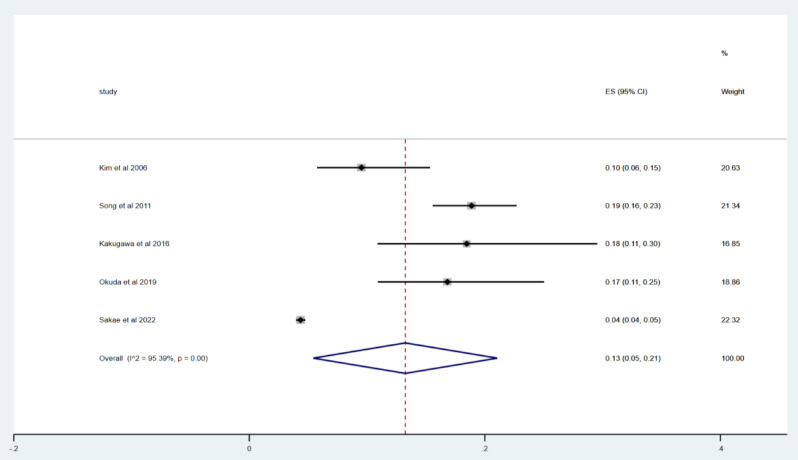

Five studies8,17,21,22,24 were included to report the incidence of acute exacerbation within 2 years. Using Metoprop analysis, the incidence of acute exacerbation within 2 years in IPF patients ranged from 4 to 19%, and the overall incidence of acute exacerbation was 13% (95% CI 5–21%; I2 = 95.39%, p = 0.00), as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Forest map of the incidence of acute exacerbation within 2 years.

Acute exacerbation rate within 3 years in IPF patients

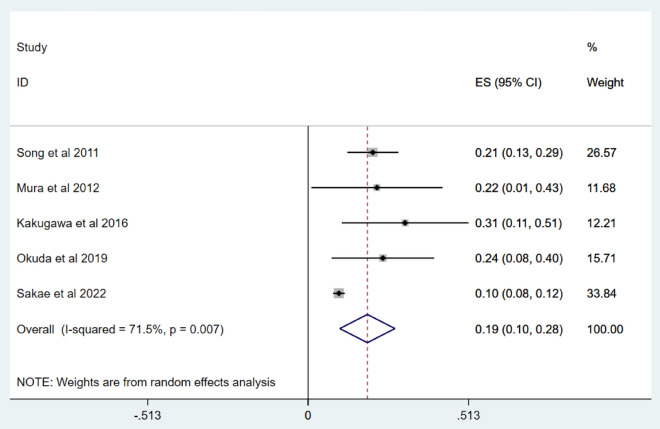

Five studies17,18,21,22,24 were included to report the incidence of acute exacerbation within 3 years. Mura et al.'s article18 included retrospective cohort study and prospective cohort study. Only retrospective cohort study was included for meta analysis. The incidence of acute exacerbation within three years in IPF patients ranged from 10 to 31%, and the overall incidence of acute exacerbation was 19% (95% CI 10–28%; I2 = 71.5%, p = 0.007), as shown in Fig. 4. Sensitivity analysis shows that after excluding individual studies one by one, the estimated total incidence of acute exacerbation is still ≥ 10%, confirming the high stability of the results in Table 3.

Fig. 4.

Forest map of the incidence of acute exacerbation within 3 years.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis.

| Deletion | Result |

|---|---|

| Song et al. (2011) | ES = 19%, 95% CI [8%, 30%] |

| Mura et al. (2012) | ES = 19%, 95% CI [9%, 28%] |

| Kakugawa et al. (2016) | ES = 17%, 95% CI [8%, 26%] |

| Okuda et al. (2019) | ES = 18%, 95% CI [8%, 28%] |

| Kishaba et al. (2020) | ES = 22%, 95% CI [16%, 29%] |

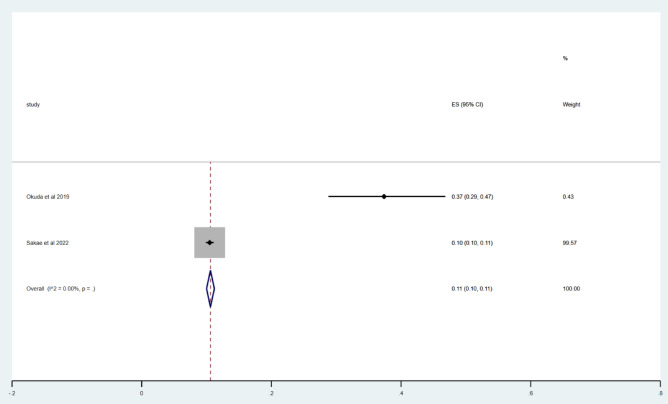

Acute exacerbation rate within 4 years in IPF patients

Two studies were included22,24 to report the incidence of acute exacerbation within 4 years. Using Metoprop analysis, no p-values were shown in the following three articles. The overall incidence of acute exacerbation within 4 years in IPF patients was 11% (95% CI 10–11%; I2 = 0.00%), as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Acute exacerbation rate within 4 years in forest.

Acute exacerbation rate within ten years in IPF patients

Only one study20 reported an acute exacerbation rate of 9.8% within ten years, so meta-analysis cannot be performed. This study included a total of 594 IPF patients from 2001 to 2010, including 58 AE—IPF patients.

Risk Factors for AE in IPF

The inclusion of four studies17,18,21,22 reported statistically significant risk factors in a multivariate model for acute exacerbation in IPF patients, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Statistically significant risk factors for AE-IPF patients in the included studies.

| References | Risk factors | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Song et al. (2011) | Smokers | 0.585 (0.342–1.001) | 0.05 |

| FVC, % pred | 0.979 (0.964–0.995) | 0.011 | |

| Mura et al. (2012) | |||

| Prospective cohort | DLco, % pred | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 0.0008 |

| Concomitant emphysema | 3.20 (1.06–10.67) | 0.04 | |

| Kakugawa et al. (2016) | Immunosuppressive agent | 3.35 (1.27–8.84) | 0.014 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 3.21 (1.24–8.32) | 0.016 | |

| Eosinophils, % (≥ 3.21%) | 2.89 (1.11–7.51) | 0.029 | |

| GAP stage (≥ II) | 3.23 (1.22–8.51) | 0.018 | |

| Okuda et al. (2019) | Minimum SpO2 in 6 MWT, 88% or less | 5.28 (1.44–19.32) | 0.012 |

| 10% or more FVC decline in 1 year | 4.14 (1.26–13.65) | 0.02 | |

| 15% or more DLco decline in 1 year | 4.66 (1.19–18.17) | 0.027 |

The FVC% value was obtained within one month after the first diagnosis. The DLCO% value is the baseline measurement value at the time of diagnosis.

FVC forced vital capacity, % pred % predicted, DLco diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, GAP gender-agephysiology, SpO2 arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry.

Prognostic factors for overall survival from the initial IPF diagnosis

Two studies17,21 were included and prognostic factors for overall survival from initial IPF diagnosis were reported in a multivariate model, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The prognostic factors for overall survival from the initial IPF diagnosis in the included studies.

| References | Risk factors | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Song et al. (2011) | Age | 1.017 (1.001–1.033) | 0.032 |

| FVC, % pred | 0.987 (0.977–0.997) | 0.009 | |

| DLco, % pred | 0.985 (0.976–0.994) | 0.001 | |

| Steroid with/without | 1.552 (1.113–2.164) | 0.01 | |

| cytotoxic agent occurrence of AE | 2.592 (1.888–3.560) | P < 0.001 | |

| Kakugawa et al. (2016) | Cardiovascular diseases | 2.37 (1.03–5.44) | 0.042 |

| GAP stage (≥ II) | 3.63 (1.47–8.93) | 0.005 | |

| SP-D, ng/mL | 3.21 (1.21–8.48) | 0.019 |

The FVC% value and the DLCO% value were obtained within one month after the first diagnosis.

FVC forced vital capacity, % pred % predicted, DLco diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, AE acute exacerbation, GAP gender-age physiology, SP-D surfactant protein-D.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic evaluation and meta-analysis on the incidence of AE-IPF. We included ten cohort studies on the incidence of AE-IPF, including 11,855 IPF patients. The results showed that the incidence of acute exacerbation within one year was 9%; the incidence of acute exacerbation within 2 years is 13%; the incidence of acute exacerbation within 3 years is 19%; the incidence of acute exacerbation within 4 years is 11%. The decrease of incidence of AE to 11% at 4 years, which seems to be due to a smaller population surviving beyond 4 years. In addition, only one study23 reported an acute exacerbation rate of 1.9% within 30 days. Only one study20 reported a 10-year acute exacerbation rate of 9.8%. Within 30 days, within one year, within two years, etc., these time points refer to the calculation starting from the patient's diagnosis of IPF. Only Mura et al.'s article18 included a retrospective cohort study and a prospective cohort study. Therefore, prospective cohort study did not include meta analysis. This study showed that the incidence of acute exacerbation within three years was 18.6%, which was similar to the results of meta analysis of retrospective cohort study. In summary, the number of studies is relatively small, therefore further exploration is needed. This study may have certain reference value for clinical doctors, patients, and health policy makers in the prevention and treatment of IPF.

Due to the lack of relevant raw data in the included studies, subgroup analysis of gender, age, and other factors is not possible. Based on existing data, only five studies16,18,21–23 have reported the number of male and female patients with IPF, with a total of 377 males and 135 females. Only five studies17,19–22 have reported the number of male and female patients with AE-IPF, with a total of 167 males and 51 females, with a slightly higher number of males than females. Previous studies have shown that IPF is generally more common in males than females30. The incidence of AE-IPF was similar among five studies in Japan20–24, but the study involved fewer regions and could not identify regional differences through subgroup analysis. This may be related to different levels of economic development, population aging, and medical conditions in different regions31.

Identifying the risk factors for AE in IPF patients is crucial for early identification of high-risk patients and helps to reduce the risk of AE. The studies we included showed that forced vital capacity (FVC), diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco) and 6-min walk test (6 MWT) were risk factors for AE in patients with IPF, which was consistent with the results of Okuda R22. Smokers, concomitant emphysema, suppressive agent, cardiovascular diseases, gender age physiology (GAP) stage (≥ II), and eosinophil percentage (≥ 3.21%) are also risk factors, but there is a lack of other relevant research data to prove them. Recently, there have been new research reports on the risk factors of AE‑IPF. In terms of respiratory tract infection, Omote et al.32 showed that an elderly patient with IPF had AE, which was caused by COVID-19 (COVD-19). The patient was sensitive to high-dose steroids, and the condition was controlled after treatment. In terms of vaccination, Bando et al.33 administered severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV-2) to two patients with IPF and one patient with interstitial lung disease related to connective tissue disease. They found that it had some effect on preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, it is not yet clear whether vaccination can cause AE in interstitial lung disease, and further exploration is needed to explore the correlation between vaccination and AE. Ghincea et al.34 administered the COVID-19 vaccine to IPF patients. Although they found a certain association between COVID-19 vaccination and AE, more relevant research data are still needed to prove. Therefore, identifying the risk factors for AE in IPF patients is a prerequisite for reducing the incidence of AE-IPF.

Understanding the various prognostic factors of IPF patients is crucial for clinicians, patients, and health policy makers to prevent and treat IPF, and helps in designing drug intervention studies6. The studies we included showed that older age, low FVC, DLco, steroid with/without, cycloxic agent occurrence of AE, cardiovascular diseases, GAP stage (≥ II), surface protein (SP)-D are factors that affect the prognosis of IPF patients, but only two studies were included with a small sample size, Lack of other relevant research data to prove. A systematic review showed that6, Scott et al.35 found that increased monocyte count is closely related to poor prognosis in IPF. Some studies36,37 suggest that pulmonary hypertension may be a prognostic factor. Other studies have shown that surgery and radiation therapy may also affect the prognosis of PF patients38,39. Although previous studies have described some risk factors, prognostic factors are still unpredictable40, and we know very little about the prognostic factors of IPF patients.

The heterogeneity in the incidence of acute exacerbation within 1, 2, and 3 years in IPF patients in this study may be due to the following reasons. Firstly, there are only 5 studies on the incidence of acute exacerbation in IPF patients within 2 to 3 years. The sample size included in the study is small, and the duration of the study and the duration of the patient's disease are inconsistent. There is limited data available for analysis, which may affect the accuracy of the results. Therefore, to clarify the relationship between the two, we need to expand the sample size and conduct a longer cohort study. Secondly, the diagnostic criteria of AE-IPF are inconsistent. The retrospective cohort study relies on electronic medical records to a large extent for the diagnosis of AE, which may cause bias in the results and is one of the sources of heterogeneity. The use of antifibrotic drugs and the revision of guidelines may have an impact on treatment. The changes in the incidence of acute exacerbation may be related to this, and further research is needed to identify these possibilities.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations: ① Most of the included studies are retrospective cohort study, and the subjects have high selection bias; ② The number of included studies is relatively small, and the sample size is relatively small; ③ The diagnostic criteria are not unified, and there are differences in the definition of AE, which may affect the research results; ④ There is significant heterogeneity in research, and due to the lack of relevant raw data in the included studies, subgroup analysis cannot be conducted on gender, age, etc.; ⑤ The results of the included studies lack universality, and the included studies were conducted in the United States, South Korea, Italy, and Japan, with half of the studies conducted in Japan, resulting in regional bias.

Conclusion

In summary, this study used Stata 16.0 software for meta-analysis and found that the incidence of AE-IPF is relatively high, which can to some extent promote public attention to preventing AE-IPF and managing diseases, and provide reference for developing global management strategies. There is a small number of literature and sample size on the incidence of AE-IPF, and there is still a lack of high-quality clinical research evidence to support it. Therefore, more well-designed and standardized large-scale clinical studies are needed for validation.

Author contributions

YX and SL contributed to design and conception of the article. YX and YW contributed to collection and assembly of materials, and drafted the manuscript. YW, ZJ, and BX contributed to data interpretation and analysis. YX, ZJ, BX and SL revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Key Research and development Program (No.2023YFC3502601), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Youth Fund(No.212300410056), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81830116), Henan Province Scientific Research Project-Double First-Class Traditional Chinese medicine (HSRP-DFCTCM-2023-3-16, DFCTCM-2023-4-05), Special Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine Research of Henan Province (20-21ZY2186), Special Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine Research of Henan Province(2023ZY2055), the Henan Province Medical Science and Technology Program (No. LHGJ20220586) and Henan Province Second Batch of Top-notch Chinese Medicine Talent Projects (2021 No. 15).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Suyun Li, Email: lisuyun2000@126.com.

Yang Xie, Email: xieyanghn@163.com.

References

- 1.Raghu, G. et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.198(5), e44–e68 (2018). 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie, T. et al. Progranulin and Activin A concentrations are elevated in serum from patients with acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung199(5), 467–473 (2021). 10.1007/s00408-021-00470-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nalysnyk, L. et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Review of the literature. Eur. Respir. Rev.21(126), 355–361 (2012). 10.1183/09059180.00002512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch, J. P. et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Epidemiology, clinical features, prognosis, and management. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med.37(3), 331–357 (2016). 10.1055/s-0036-1582011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richeldi, L., Collard, H. R. & Jones, M. G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet389(10082), 1941–1952 (2017). 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamiya, H. & Panlaqui, O. M. Systematic review and meta-analysis is of prognostic factors of acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open10(6), e035420 (2020). 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie, T. et al. Progra nulin and activin a concentrations are elevated in serum from patients with a cute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung199(5), 467–473 (2021). 10.1007/s00408-021-00470-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim, D. S. et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Frequency and clinical features. Eur. Respir. J.27(1), 143–150 (2006). 10.1183/09031936.06.00114004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collard, H. R. et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An International Working Group report. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.194(3), 265–275 (2016). 10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondoh, Y. et al. Acute exacerbation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Analysis of clinical and pathologic findings in three cases. Chest103(6), 1808–1812 (1993). 10.1378/chest.103.6.1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collard, H. R. et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.176(7), 636–643 (2007). 10.1164/rccm.200703-463PP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryerson, C. J. et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Shifting the paradigm. Eur. Respir. J.46(2), 512–520 (2015). 10.1183/13993003.00419-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maher, T. M. et al. Global incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res.22(1), 197 (2021). 10.1186/s12931-021-01791-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ372, n71 (2021). 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol.25(9), 603–605 (2010). 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández Pérez, E. R. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A population-based study. Chest137(1), 129–137 (2010). 10.1378/chest.09-1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song, J. W. et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur. Respir. J.37(2), 356–363 (2011). 10.1183/09031936.00159709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mura, M. et al. Predicting survival in newly diagnosed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A 3-year prospective study. Eur. Respir. J.40(1), 101–109 (2012). 10.1183/09031936.00106011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collard, H. R. et al. Suspected acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis as an outcome measure in clinical trials. Respir. Res.14(1), 73 (2013). 10.1186/1465-9921-14-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kishaba, T. et al. Staging of acute exacerbation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung192(1), 141–149 (2014). 10.1007/s00408-013-9530-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakugawa, T. et al. Risk factors for an acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res.17(1), 79 (2016). 10.1186/s12931-016-0400-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuda, R. et al. Newly defined acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with surgically-proven usual interstitial pneumonia: Risk factors and outcome. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffuse Lung Dis.36(1), 39–46 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishaba, T. et al. Predictors of acute exacerbation in biopsy-proven idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Invest.58(3), 177–184 (2020). 10.1016/j.resinv.2020.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homma, S. et al. Incidence and changes in treatment of acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Japan: A claims-based retrospective study. Respir. Investig.60(6), 798–805 (2022). 10.1016/j.resinv.2022.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161, 646–664 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.ATS/ERS. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165, 277–304 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Raghu, G. et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.183, 788–824 (2011). 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Japanese Respiratory Society. The Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia. Revised 4th Ed. (2022).

- 29.Akira, M. et al. CT findings during phase of accelerated deterioration in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.168, 79–83 (1997). 10.2214/ajr.168.1.8976924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wuyts, W. A. et al. Longitudinal clinical outcomes in a real-world population of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: The PROOF registry. Respir. Res.20(1), 231 (2019). 10.1186/s12931-019-1182-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao, G. et al. Prevalence of lung cancer in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol.12, 947981 (2022). 10.3389/fonc.2022.947981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omote, N. et al. Successful treatment with high-dose steroids for acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis triggered by COVID-19. Intern. Med.61(2), 233–236 (2022). 10.2169/internalmedicine.8163-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bando, T. et al. Acute exacerbation of diopathic pulmonary fibrosis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Eur. Respir. J.59(3), 2102806 (2022). 10.1183/13993003.02806-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghincea, A., Ryu, C. & Herzog, E. L. An acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: A case report. Chest161(2), e71–e73 (2022). 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott, M. K. D. et al. Increased monocyte count as a cellular biomarker for poor outcomes in fibrotic diseases: A retrospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med.7(6), 497–508 (2019). 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30508-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karampitsakos, T. et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with interstitial lung disease. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther.50, 38–46 (2018). 10.1016/j.pupt.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Judge, E. P. et al. Acute exacerbations and pulmonary hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J.40(1), 93–100 (2012). 10.1183/09031936.00115511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karampitsakos, T. et al. Lung cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther.45, 1–10 (2017). 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato, T. et al. Long-Term results and predictors of survival after surgical resection of patients with lung cancer and interstitial lung diseases. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.149, 64–70 (2015). 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.08.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu, M., Chen, Y. & Ye, Q. Risk factors for acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Respir. J.12(3), 1084–1092 (2018). 10.1111/crj.12631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.