Abstract

Background

In recent years, the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of digital health services for people with musculoskeletal conditions have increasingly been studied and show potential. Despite the potential of digital health services, their use in primary care is lagging. A thorough implementation is needed, including the development of implementation strategies that potentially improve the use of digital health services in primary care. The first step in designing implementation strategies that fit the local context is to gain insight into determinants that influence implementation for patients and health care professionals. Until now, no systematic overview has existed of barriers and facilitators influencing the implementation of digital health services for people with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting.

Objective

This systematic literature review aims to identify barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital health services for people with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL were searched for eligible qualitative and mixed methods studies up to March 2024. Methodological quality of the qualitative component of the included studies was assessed with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. A framework synthesis of barriers and facilitators to implementation was conducted using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). All identified CFIR constructs were given a reliability rating (high, medium, or low) to assess the consistency of reporting across each construct.

Results

Overall, 35 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis. Methodological quality was high in 34 studies and medium in 1 study. Barriers (–) of and facilitators (+) to implementation were identified in all 5 CFIR domains: “digital health characteristics” (ie, commercial neutral [+], privacy and safety [–], specificity [+], and good usability [+]), “outer setting” (ie, acceptance by stakeholders [+], lack of health care guidelines [–], and external financial incentives [–]), “inner setting” (ie, change of treatment routines [+ and –], information incongruence (–), and support from colleagues [+]), “characteristics of the healthcare professionals” (ie, health care professionals’ acceptance [+ and –] and job satisfaction [+ and –]), and the “implementation process” (involvement [+] and justification and delegation [–]). All identified constructs and subconstructs of the CFIR had a high reliability rating. Some identified determinants that influence implementation may be facilitators in certain cases, whereas in others, they may be barriers.

Conclusions

Barriers and facilitators were identified across all 5 CFIR domains, suggesting that the implementation process can be complex and requires implementation strategies across all CFIR domains. Stakeholders, including digital health intervention developers, health care professionals, health care organizations, health policy makers, health care funders, and researchers, can consider the identified barriers and facilitators to design tailored implementation strategies after prioritization has been carried out in their local context.

Keywords: eHealth, primary health care, musculoskeletal problems, implementation science, systematic review, mobile phone

Introduction

Background

Approximately 1.71 billion people experience musculoskeletal conditions, which are a major contributor to health care problems worldwide [1]. Worldwide population growth and aging will increase the burden of musculoskeletal conditions on health care in the upcoming decades [2,3]. Therefore, prevention, early detection, and optimal treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, which comprise one of the largest patient groups in primary care, become increasingly important [4-6]. However, patients experience barriers that decrease access to primary care services, such as geographic and transport-related barriers, lack of health insurance, no after-hours access, and a shortage of primary health care professionals [7,8]. A potential solution to optimize prevention and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, reduce the burden of musculoskeletal conditions on health care, and improve accessibility in primary care is the use of digital health services.

Digital health is an umbrella term encompassing eHealth and mobile health, which are defined as the use of information and communications technology in support of health and health-related fields and the use of mobile wireless technologies for health [9]. Examples are video consultations between a health care professional and patient and the integration of apps within primary care treatment. There are several potential benefits to digital health services, such as improved cost-effectiveness, more information about the health status of the patient, better communication between patients and health care professionals, and more accessibility for patients [10,11]. Previous research supports the effectiveness of digital health services in reducing pain and improving functional disability, catastrophizing, coping ability, and self-efficacy [12,13].

Despite the benefits of digital health services, their use for musculoskeletal conditions in primary care is lagging. Therefore, a thorough implementation is needed, including the development of implementation strategies that potentially improve the use of digital health services for patients with musculoskeletal conditions in primary care. Important stakeholders for designing these implementation strategies are eHealth developers, health care professionals, health care organizations, health policy makers, health care funders, and researchers. The first step to design implementation strategies for local contexts is to perform a determinant analysis in a more specific context to gain insight into determinants that influence implementation from the perspective of patients and health care professionals. Several studies have identified barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital health services in other settings and populations [14-17]. Some of these barriers for patients or health care professionals in these settings are workflow, resistance to change, costs, reimbursement, intervention design, and digital literacy. However, it remains unclear which barriers and facilitators are applicable for patients with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting and what the overarching narrative is for this patient population and setting. A generic overview of barriers and facilitators within this more specific context, which is the aim of this systematic review, is useful as a first step for a thorough implementation. A prioritization of these barriers and facilitators for various local contexts, that is, a specific primary care physiotherapy practice, would be the next step to design fitting implementation strategies for the local context [18].

A practical theory-based framework to guide for systematical assessment of barriers and facilitators that influence implementation is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [18]. The CFIR consolidates implementation determinants from a broad array of implementation theories and is composed of 5 domains (intervention [digital health service] characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals [health care professionals], and the implementation process), and it provides a systematic way of identifying constructs that have been associated with effective implementation. The use of a framework such as CFIR to structure the overview of barriers and facilitators allows stakeholders undertaking implementation activities to focus on barriers and facilitators that are of most interest to them more easily and design implementation strategies that are specific to their local context [19].

Objectives

No systematic overview of barriers and facilitators influencing the implementation of digital health services for people with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting exists to support these stakeholders in designing fitting implementation strategies. Therefore, the aim of this systematic literature review was to identify barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital health for people with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting.

Methods

This systematic literature review of qualitative data from qualitative and mixed methods articles is reported following the enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research statement [20]. Exclusively incorporating qualitative evidence in this systematic review enables a nuanced exploration of the multifaceted factors influencing implementation, providing diverse perspectives and in-depth insights from both patients and health care providers.

Search Strategy

The electronic databases PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL were searched to seek all available studies up to March 2024. The complete search strategy can be found in Multimedia Appendix 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Textbox 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Domain: adults (aged ≥18 years); musculoskeletal conditions (eg, low back pain, osteoarthritis, and total knee replacement); primary health care setting (eg, general practice and physiotherapy practice)

Determinant: the health care professional (eg, general practitioners, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists) has provided digital health (eg, synchronous patient-therapist interactions through telephone or video consultations and asynchronous physical exercise training, coaching, and monitoring using web applications, wearables, and platforms) more than once during an intervention

Outcome: data on barriers or facilitators to the implementation of digital health services that fit into one of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research domains; data of patients or health care professionals

Article type: qualitative and mixed methods designs; full text in English is available

Exclusion criteria

Determinant: web-based training programs for health care professionals

Article type: articles with no qualitative component, such as a quantitative survey only

Selection of Studies

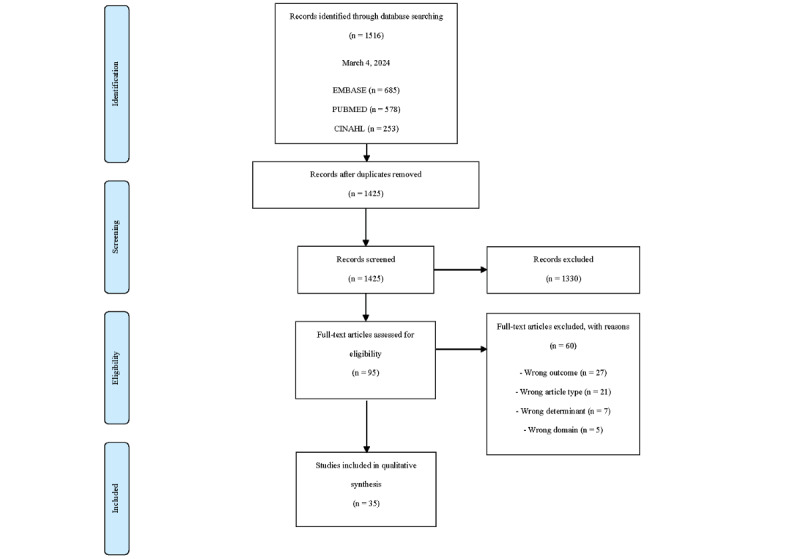

The web-based screening tool Rayyan was used for the selection of studies [21]. A total of 3 reviewers (MLvT, IS, and MvdV) conducted the inclusion of eligible articles. Articles were screened independently by 2 reviewers for eligibility based on title and abstract. When an article was potentially eligible for inclusion, a full paper copy of the report was obtained and screened independently by 2 reviewers. Disagreements between the reviewers regarding an article’s eligibility were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. In case of disagreement, a fourth reviewer (CJJK) was consulted. In addition, reference tracking was performed in all included articles. The reasons for exclusion were recorded (Figure 1) [22].

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram.

Data Extraction and Management

The reviewers extracted the following data using a standardized extraction form: first author, country, year of publication, aim, design and method of data collection and methods of analysis, sample, description of digital health service, and data on barriers or facilitators to the implementation of digital health services reported in the Results section.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

In total, 3 reviewers (MLvT, IS, and MvdV) independently assessed the methodological quality of the qualitative component of the included articles. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to appraise studies for this review [23]. It is a 5-item tool designed to appraise the methodological quality of 5 categories of studies, including qualitative and mixed methods studies. The MMAT has established content validity and has been piloted across the mentioned methodologies [24]. The MMAT encompasses 2 initial screening questions: “Are there clear research questions?” and “Do the collected data allow to address the research questions?” Methodological quality assessment was only performed if “yes” could be answered for both screening questions. A detailed presentation of the individual ratings of each MMAT criterion was provided to inform the quality of the included studies. Overall sum scores were calculated based on the quality of the qualitative component only and presented as number of stars (*), with 0 and 1 star indicating low quality, 2 and 3 stars indicating medium quality, and 4 and 5 stars indicating high quality [25]. These cutoff values were determined by 2 reviewers (MLvT and IS), as the MMAT subscribes, and are arbitrary but useful for transparent data syntheses. Disagreements were resolved in a consensus meeting between the raters. When there was any disagreement, a fourth reviewer (CJJK) could be consulted but was not necessary. As the aim was to describe and synthesize a body of qualitative literature and not determine an effect size, the quality assessment was only included to inform the overall quality of the included articles and to determine the reliability rating.

Data Synthesis

A framework synthesis was performed, with secondary thematic analysis of the results section of the included articles. To synthesize the findings, the CFIR was used, using the 2009 version because the analysis began before the 2022 update [18]. Initially, MLvT and IS used an open coding process to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation and allocated them to the most fitting CFIR construct or subconstruct using a coding manual from the CFIR [26]. During the axial coding process, these open codes were organized into thematic categories representing barriers and facilitators to implementation. MLvT conducted the axial coding, which was reviewed by IS and CJJK on an iterative basis. As the thematic analysis progressed, recurring themes identified across the included studies informed the development of a comprehensive narrative for the generic overview of barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Next, all identified CFIR constructs or subconstructs were given (MLvT, IS, and MvdV) a reliability rating to review the consistency of reporting across each construct and the quality of the studies that identified them, which was also reported in another systematic review on barriers and facilitators in another context and aims to indicate confidence in the findings [27]. All disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Three levels of reliability were distinguished: (1) high reliability (the construct is consistently supported by >1 study of medium quality and 1 study of high quality or the construct is supported by at least 2 studies of high quality based on the MMAT); (2) medium reliability (the construct is supported by >1 study of medium quality or the construct is identified on the basis of at least 1 high-quality study based on the MMAT); and (3) low reliability (the construct is supported only by studies of low quality or single studies of medium quality based on the MMAT).

Results

Study Selection

The literature search resulted in a total of 1516 articles found in the Embase, PubMed, and CINAHL databases. After removing duplicates, 1425 articles were screened based on title and abstract. This resulted in 95 studies that were screened full text, after which studies were excluded on outcome (n=27, 28%), article type (n=21, 22%), determinant (n=7, 7%), and domain (n=5, 5%). In 2 cases of initial disagreement between reviewers, a fourth reviewer (CJJK) was consulted. Finally, 35 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis [28-62]. No additional studies were found through reference checking. The study selection procedure is presented in Figure 1.

Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Individual articles are ordered alphabetically within all presented tables. All included articles were published between 2011 and 2024. A total of 10 articles originated from Australia [31,38,40,44,47,48,52,54,57,60]; 9 articles originated from the Netherlands [28-30,35,39,43,45,46,62]; 4 articles originated from Canada [34,37,41,50]; 3 articles originated from the United Kingdom [51,53,59]; 2 articles originated from Brazil [36,58], Sweden [32,55], and France [42,61]; and 1 article originated from Denmark [56]. The digital health services mentioned in the included articles aimed to facilitate synchronous patient-therapist interactions through telephone or video consultations and to support asynchronous physical exercise training, coaching, and monitoring using web applications and platforms. The participants in the included articles primarily consisted of patients, physiotherapists, and general practitioners but also encompassed occupational therapists, dietitians, psychologists, and a pharmacist. Patients presented with a variety of musculoskeletal conditions, including knee and hip osteoarthritis, knee conditions, chronic nonspecific low back pain, Achilles tendinopathy, traumatic hand injury, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, shoulder joint replacement, and total knee replacement.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year, country | Aims of the study | Methodsa | Participantsa | Digital health service |

| Aily et al [58], 2020; Brazil |

|

|

|

In-person exercise therapy instructions along with a booklet and DVD to take home. Participants also received 6 motivational phone calls throughout the 12-week treatment |

| Arensman et al [43], 2022; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

The Physitrack app that allows physiotherapists to create and share personalized exercise programs with patients. The app allows patients to set reminders to perform their exercises, track their adherence, rate pain scores during the exercises, and send direct messages to their physiotherapists |

| Barton et al [40], 2022; Australia |

|

|

|

Telehealth care from physiotherapists throughout Australia |

| Bossen et al [62], 2016; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

E-Exercise is a 12-week intervention, which combines visits with a physiotherapist and a web-based physical activity intervention. Patients receive 4 face-to-face sessions and are supposed to complete 12 web-based assignments. The website has a portal for both patients and physiotherapists and contains text- and video-based information |

| Button et al [51], 2018; the United Kingdom |

|

|

|

TRAK is a web-based intervention for supporting rehabilitation of knee conditions, with a potential to enhance the quality of treatment components, such as health information provision, rehabilitation monitoring, remote support, and personalized exercise progression |

| Martínez de la Cal et al [49], 2021; Spain |

|

|

|

McKenzie Exercise Therapy and electroanalgesia based on telerehabilitation with the help of 10.1 “Quad Core” tablets |

| Cottrell et al [52], 2017; Australia |

|

|

|

Telerehabilitation: delivery of rehabilitation service at a distance using telecommunications technology |

| Dehainault et al [42], 2024; France |

|

|

|

Participants were presented with screenshots from the “Mon Coach Dos” and “Activ’Dos” mobile apps, with a standardized explanatory presentation framework. An information sheet about the apps was integrated into the slideshow presenting their description, creator, funding, and data use |

| Dunphy et al [53], 2017; the United Kingdom |

|

|

|

TRAK is a digital intervention developed to support self-management of knee conditions. TRAK provides a platform for individually tailored exercise programs with videos, detailed instructions and progress logs for individual exercises, a health information section, and a contact option that allows a patient to email a physiotherapist for additional support |

| Egerton et al [54], 2017; Australia |

|

|

|

The new model for primary care management of knee osteoarthritis includes a multidisciplinary team of health professionals using remote delivery options (primarily telephone) to provide ongoing “care support.” The GP refers the patient to the “care support team” following a brief initial consultation. The “care support team” staff will have skills in health behavior change plus expertise in current best practice for knee osteoarthritis management |

| Eriksson et al [55], 2011; Sweden |

|

|

|

A 2-month home-based video physiotherapy program, supervised by an experienced physiotherapist specializing in shoulder problems. |

| Ezzat et al [38], 2022; Australia |

|

|

|

GLA:Dh is a physiotherapist-led 8-week program, which includes 2 group education sessions, followed by 12 supervised, neuromuscular exercise therapy sessions. The program is delivered via telehealth or in person |

| Ezzat et al [44], 2023; Australia |

|

|

|

GLA:D is a physiotherapist-led 6- to 8-week program, which includes 2 to 3 group education sessions, followed by 12 supervised, neuromuscular exercise therapy sessions. The program is delivered via telehealth or in person |

| Farzad et al [41], 2023; Canada |

|

|

|

Web-based hand therapy interventions |

| Geraghty et al [59], 2020; the United Kingdom |

|

|

|

SupportBack is a web-based platform to support patients through a self-tailored, 6-week self-management program. Contents include exercises or a walking program with weekly goals, feedback, and advice. Patients also received 3 telephone calls from an musculoskeletal physiotherapist to provide reassurance, address concerns, problem-solve, and encourage continued engagement with the intervention and physical activity goals |

| Hasani et al [60], 2021; Australia |

|

|

|

Gym-based exercise program where the participants performed 4 sets of unilateral isotonic standing and seated calf raise exercises in a Smith machine (both sides, one leg at a time) 3 times per week, over 12 weeks Physiotherapists supervised 1 session per week via videoconference software (Zoom) that was downloaded to the participants’ smartphone |

| Hinman et al [48], 2017; Australia |

|

|

|

Participants were provided 7 internet-based Skype-delivered physical therapy sessions for 3 months, with the main purpose being to prescribe an individualized home-based strengthening program to be undertaken 3 times per week |

| Hjelmager et al [56], 2019; Denmark |

|

|

|

Distribution of health-related information via the internet |

| Kairy et al [50], 2013; Canada |

|

|

|

An in-home telerehabilitation program consisting of twice-a-week physiotherapy sessions for 8 weeks (total 16 sessions) by a videoconferencing system located in the participant’s home |

| Kelly et al [33], 2022; Ireland |

|

|

|

The use of technological platforms (eg, mobile, computer and tablet) in physiotherapy |

| Kingston et al [57], 2015; Australia |

|

|

|

The use of technology, namely, telehealth and the use of the internet |

| Kloek et al [46], 2020; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

The intervention consists of about 5 physiotherapy sessions in combination with a web-based application (E-Exercise). The web-based application contains a tailored 12-week behavioral graded activity program, videos with strength and mobility exercises, and videos and texts with information about osteoarthritis-related topics. |

| Lamper et al [39], 2021; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

The eCoach Pain is an electronic coach to facilitate pain rehabilitation. It supports the provision of integrated rehabilitation care with a shared biopsychosocial vision on health. Both patients and primary health care professionals use the eCoach Pain. It comprises a measurement tool for assessing complexity of the pain problem, diaries, pain education sessions, monitoring options, and a chat function |

| Lawford et al [47], 2019; Australia |

|

|

|

The patients received 5 to 10 telephone consultations over a 6-month period. Physiotherapists devised goals and an action plan for each patient that involved both a structured home exercise program and a physical activity plan. Patients also had access to a study website containing video demonstrations of each exercise |

| Van der Meer et al [29], 2022; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

eHealth included in the health care process of people with TMD |

| Östlind et al [32], 2022; Sweden |

|

|

|

A wearable activity tracker (Fitbit Flex 2) in combination with the Fitbit app for 12 weeks. The participants were asked to monitor their activity daily, and they received automatic feedback from the app |

| Palazzo et al [61], 2016; France |

|

|

|

The use of new technologies to decrease the burden of home-based exercise programs in chronic LBP |

| Passalent et al [37], 2022; Canada |

|

|

|

Technology for encouraging physical activity |

| Pereira et al [36], 2023; Brazil |

|

|

|

Physical therapy by telerehabilitation |

| Petrozzi et al [31], 2021; Australia |

|

|

|

Physical treatments combined with an internet-delivered psychosocial program called MoodGYM |

| Poolman et al [35], 2024; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

Back2Action is a newly developed biopsychosocial-blended intervention consisting of in-person physiotherapy sessions blended with psychologically informed digital health. The digital part of the intervention incorporates pain education and behavioral activation |

| Renard et al [34], 2022; Canada |

|

|

|

Teleconsultation follow‐ups |

| Van Tilburg et al [45], 2022; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

The patients received a stratified blended intervention, whereby a prognostic stratification tool, a web-based application (e-Exercise), and face-to-face physiotherapy sessions are integrated within physiotherapy treatment to create an optimal combination |

| Van Tilburg et al [30], 2023; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

A blended physiotherapy treatment (e-Exercise) for people with neck and shoulder conditions in which a smartphone app with personalized information, exercises, and physical activity modules was an integral part of physiotherapy treatment |

| De Vries et al [28], 2017; the Netherlands |

|

|

|

The web-based component of e-Exercise consists of a 12-week incremental physical activity program based on graded activity, strength and stability exercises, and information on osteoarthritis-related themes. The offline component consists of up to 5 face-to-face physiotherapy sessions |

aFor mixed methods designs, only the data collection, data analysis, and participants from the qualitative component are described.

bLBP: low back pain.

cTRAK: Taxonomy for the Rehabilitation of Knee Conditions.

dN/OPSC: Neurosurgical and Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Screening Clinic.

eMDS: multidisciplinary service.

fACL: anterior cruciate ligament.

gGP: general practitioner.

hGLA:D: Good Life with Osteoarthritis in Denmark.

iRE-AIM QuEST: Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance Qualitative Evaluation for Systematic Translation.

jTMD: temporomandibular disorder.

Information about methodological quality of the studies is presented in Table 2. Almost all qualitative components of the included studies, assessed with the MMAT, were of high methodological quality. In total, 31 articles scored 5 stars, and 3 articles scored 4 stars. Qualitative component of 1 article was of medium methodological quality and scored 3 stars.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of the included studies.

| Study | Criteria from the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool: qualitative studies | Total number of stars (based on the qualitative component) | |||||

|

|

1.1a | 1.2b | 1.3c | 1.4d | 1.5e |

|

|

| Aily et al [58], 2020 | 0f | 1g | 1 | 1 | 1 | *** | |

| Arensman et al [43], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Barton et al [40], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Bossen et al [62], 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | **** | |

| Button et al [51], 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Martínez de la Cal et al [49], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Cottrell et al [52], 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Dehainault et al [42], 2024 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Dunphy et al [53], 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Egerton et al [54] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Eriksson et al [55], 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | **** | |

| Ezzat et al [38], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Ezzat et al [44], 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Farzad et al [41], 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Geraghty et al [59], 2020 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Hasani et al [60], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Hinman et al [48], 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Hjelmager et al [56], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Kairy et al [50], 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Kelly et al [33], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Kingston et al [57], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Kloek et al [46], 2020 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Lamper et al [39], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Lawford et al [47], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| van der Meer et al [29], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Östlind et al [32], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Palazzo et al [61], 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Passalent et al [37], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Pereira et al [36], 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Petrozzi et al [31], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Poolman et al [35], 2024 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| Renard et al [34], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| van Tilburg et al [45], 2022 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| van Tilburg et al [30], 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ***** | |

| De Vries et al [28], 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | **** | |

a1.1=Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question?

b1.2=Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question?

c1.3=Are the findings adequately derived from the data?

d1.4=Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data?

e1.5=Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation?

f0=no.

g1=yes.

Barriers and Facilitators by CFIR

Overview

An overview of CFIR constructs or subconstructs influencing implementation of digital health services for patients with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting, with the sources and reliability rating, is presented in Table 3. An overview of the data synthesis supported by illustrative quotes, is presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Constructs that influence implementation of digital health.

| CFIRa domain, construct, and subconstruct | Studies | Reliability | ||||

| Innovation characteristics | ||||||

|

|

Innovation source | [42,53,56] | High | |||

|

|

Relative advantage | [28-45,47-50,52-57,59-62] | High | |||

|

|

Adaptability | [28-34,39,41-46,48,50,52-54,56,57,59,61,62] | High | |||

|

|

Complexity | [28-30,37,40,43-45,48,50,51,53,55,56,59,60] | High | |||

|

|

Design quality and packaging | [29,33,34,40,45,48,50,53,55,56,59,61,62] | High | |||

|

|

Cost | [29,34,40,41,46,47,52,54,55,62] | High | |||

| Outer setting | ||||||

|

|

Patient needs and resources | [28,31,33-36,38,41,42,44-48,50-53,55,57-62] | High | |||

|

|

External policy and incentives | [29,31,32,41,44,46,62] | High | |||

| Inner setting | ||||||

|

|

Networks and communications | [39,52,54] | High | |||

|

|

Implementation climate | |||||

|

|

|

Tension for change | [29,44,49,52,54,56,57] | High | ||

|

|

|

Compatibility | [29,30,39,44,46-48,51,52,54] | High | ||

|

|

|

Learning climate | [45,46] | High | ||

|

|

Readiness for implementation | |||||

|

|

|

Available resources | [28,30,32,33,36,38,40,41,43-45,48,49,51-53,56,60,61] | High | ||

|

|

|

Access to knowledge and information | [45-47,51,52,60] | High | ||

| Characteristics of individuals | ||||||

|

|

Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention | [29,33,42,44-49,51-54,56,60,62] | High | |||

| Process | ||||||

|

|

Engaging | |||||

|

|

|

Opinion leaders | [56] | Medium | ||

|

|

|

Key stakeholders (health care professional) | [50,52,54,60] | High | ||

|

|

Executing | [60] | Medium | |||

aCFIR: Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Table 4.

Overview of the data synthesis supported by illustrative quotes.

| CFIRa domain, construct, and subconstruct | Barriers (–) and facilitators (+) with illustrative quotes | ||||

| Digital health service characteristics | |||||

|

|

Innovation source |

|

|||

|

|

Relative advantage |

|

|||

|

|

Adaptability |

|

|||

|

|

Complexity |

|

|||

|

|

Design quality and packaging |

|

|||

|

|

Cost |

|

|||

| Outer setting | |||||

|

|

Patient needs and resources | ||||

|

|

External policy and incentives |

|

|||

| Inner setting | |||||

|

|

Networks and communications |

|

|||

|

|

Implementation climate | ||||

|

|

|

Tension for change |

|

||

|

|

Readiness for implementation | ||||

|

|

|

Compatibility |

|

||

|

|

|

Learning climate | |||

|

|

Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention | ||||

|

|

|

Available resources |

|

||

|

|

|

Access to knowledge and information |

|

||

| Characteristics of individuals | |||||

|

|

Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention |

|

|||

| Process | |||||

|

|

Engaging | ||||

|

|

|

Opinion leaders |

|

||

|

|

Executing | ||||

|

|

|

Key stakeholders (health care professional) |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

aCFIR: Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Domain 1: Digital Health Service Characteristics

Innovation Source (High Reliability)

Commercially neutral digital health services may facilitate implementation according to health care professionals because logos of, for example, pharmaceutical companies could indicate economic instead of public health interests [42,56]. A link with an institution with a good image, such as a specialized hospital, may also be a facilitator to implementation, according to health care professionals, because it promotes trust [53].

Relative Advantage (High Reliability)

When patients or health care professionals experience a relative advantage of digital health services over usual care, this may facilitate implementation. Mentioned relative advantages were promoting adherence [28-30,33,43,49,53,61,62], self-management [29-31,33,34,36,40,42-44,47,48,53,59], empowerment [34,42,44,48,53,55], motivation through support [28,31-33,37,38,43,53,59-61], access to health care [29,34,36,38,40,41,44,45,47-50,52-54,56,60,62], creating societal awareness [56] for specific health problems, and a continuous care chain [33,36,39,42,44,55,61]. The integration of digital health and therapy sessions (blended care) is described by patients and health care professionals as a facilitator because the digital health service can then be tailored to patient’s needs, complementary therapy can be offered, and self-efficacy can be enhanced [28-30,32,35,39-44,48,52,53,56,62]. However, there were also some concerns among health care professionals that quality of care may be reduced because, for example, physical examination may not be as thorough compared to usual face-to-face care [30,32-34,36,38-44,52,54,57]. On the contrary, some health care professionals believed that extra time and encouragement for the patient through a digital health service may result in better treatment outcomes. Advantages and disadvantages related to the patient–health care professional relationship were also experienced as both barriers and facilitators to implementation by patients and health care professionals [29-31,33,34,40,41,44,47,50,52,53,55]. Patients reported, for example, that when having health concerns, they prefer face-to-face reassurance over reassurance through a digital health service. Physiotherapists also had some concerns about creating a professional relationship if there are none or less face-to-face sessions. In contrast, they experienced that consulting via telephone forced them to focus on effective conversations, which allowed them to talk at a more personal level with patients. In addition, privacy and safety concerns may be barriers to implementation [36,40,42-44,52]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, safely providing health care from home was reported as a facilitator for implementation.

Adaptability (High Reliability)

Both health care professionals and patients agreed that adaptability of digital health services to fit the local context may be an important facilitator to implementation. Digital health services that are flexible to tailor to specific patient needs and suitable for various groups or subgroups of patients facilitate implementation [28-34, 39, 41, 42, 44-46, 48, 50, 52-54, 56, 57, 59, 61, 62]. Another facilitating determinant was an evolving intervention [43,56,61]. Use of a digital health service may increase if its content changes and information and features are continuously updated.

Complexity (High Reliability)

Complexity of digital health services that affect implementation is mostly linked to usability. Facilitating determinants concerning usability may be easy installation; easy to use; simple design and interface; simple navigation; visual support of text; and a not too wordy, manageable content [28-30,37,40,43-45,48,50,51,53,56,59,60]. Barriers concerning usability may be functional limitations of digital health services used in health care compared to those available on the commercial market. Another facilitating determinant to implementation was sufficient health care professional management for patients, such as updating relevant links and personal plans or the provision of technical aid by health care professionals to reduce complexity [28,53,55].

Design Quality and Packaging (High Reliability)

Experienced excellence in design quality and packaging of digital health services, such as variety and range of content and functionalities [29,30,32,35,37,45,53,59,61,62], persuasive design [45,53,56], and modality [33,34,40,45,53,61], may facilitate implementation according to both patients and health care professionals. Some mentioned functionalities are personal plans, exercise logs with speech notes as an alternative to text input, information modules with educational videos alongside written information, a progress dashboard with milestones, email or chat support, reminder tools, and feedback functions. An app was preferred over a website as modality, in particular, because of offline functionalities of an app.

Cost (High Reliability)

Costs associated with digital health services may be a barrier to implementation. Next to direct costs, a potential reduced number of treatment sessions [29,46,52,55,62] may both be a barrier and facilitator to implementation. Potential loss of income because of substitution of treatment sessions was experienced as a barrier by health care professionals. However, reducing treatment sessions may be a facilitator to some health care professionals because of efficiency, and offering innovative interventions attracts new patients, which is a financial incentive. Some health care professionals mentioned that patient expenses for digital health services may be a barrier to implementation [29,34,40,41,47,54]. In addition, digital health services may improve access to care for patients living in remote areas and may save them travel expenses, which was experienced as a facilitator to implementation.

Domain 2: Outer Setting

Patient Needs and Resources (High Reliability)

Needs of patients may influence the participation in digital health. Personal traits of patients, such as poor digital literacy [28,33,42,45,46,49,51,52], poor communication skills [34,41,47], higher age [36,41,42,44,45,56], lack of motivation [28,31,35,38,42,44,45,51,53,58,61], maladaptive illness perceptions [36,61], and feeling depressed [61], may be barriers to adherence or participation and therefore to implementation of digital health in primary care. Moreover, entertaining strategies for performing exercises, such as exercises in a video game, might improve engagement according to patients, which facilitates implementation [61].

External Policy and Incentives (High Reliability)

Broad acceptance of digital health by patients, health care professionals, and health service funders creates trust for health care professionals that implementation is worthwhile. Therefore, acceptance by these stakeholders, or even the demand by stakeholders such as patients, may be an important facilitator to implementation [29,31,32,44,54]. The absence of health care guidelines [44,46], standards, or protocols in using digital health and strict privacy regulations [41] may be barriers to implementation. Another barrier to health care professionals may be a lack of external financial incentive if the digital health intervention aims to substitute treatment sessions [62].

Domain 3: Inner Setting

Networks and Communications (High Reliability)

Effective, useful, and timely channels of communication between health care professionals involved in the use of a digital health intervention may be facilitators to implementation [39,52,54]. An example is the quality and quantity of communication between a general practitioner and a care support team that provided remotely delivered interventions in a multidisciplinary intervention. Another facilitator is some sort of personal relationship between health care professionals that are involved in using a digital health service [54].

Implementation Climate—Tension for Change (High Reliability)

Health care professionals and patients agreed that there is a need for change, which was a facilitator to implementation of digital health. Problems that create a tension for change are poor accessibility to health care [49,52,57] because of for example medical comorbidities, poor health literacy or inconvenient appointment times, large distance to health care service, high burden of health care on health care professionals, no availability of a (specialized) health care professional, and the need for trustworthy information [56].

Implementation Climate—Compatibility (High Reliability)

Integrating digital health services into usual care requires change of treatment routines, which may be a barrier to implementation, specifically because of lack of knowledge and practice to adapt routines, lack of confidence, and resistance to change of health care professionals [29,30,39,44,46-48,51,52,54]. Positive experiences with integrating digital health services into usual care may lead to more acceptability and may overcome this barrier. Moreover, incompatibility with other initiatives and guidelines may be barriers to implementation [54]. There are many initiatives and guidelines for management of musculoskeletal conditions, and whenever these are incompatible with a digital health service, treatment routines may become complicated and confusing. In addition, incompatibility with existing payment structures may lead to inequity of care and was a barrier to implementation according to health care professionals [54]. Health care professionals mentioned that information incongruence could be another barrier to implementation [54]. Safety may be affected when patient advice and information, provided by health care professionals and via digital health services, are incongruent and as a consequence cause the health care professional to spend extra time and effort to deal with conflicting messages.

Implementation Climate—Learning Climate (High Reliability)

The extent to which health care professionals feel as essential, valued, and knowledgeable partners in the implementation process creates a better climate for implementation. Facilitators to implementation of digital health services may be support from colleagues and that the professional autonomy of health care professionals was maintained [45,46].

Readiness for Implementation—Available Resources (High Reliability)

Available resources, including the availability of suitable infrastructure, may facilitate the implementation of digital health. Technology-related issues may be a barrier to implementation [32,33,36,38,40,43,48-51,53,55,60]. Both patients and health care professionals mentioned several technology-related issues, including troubles with initially setting up or operating the technology, insufficient battery life, poor or no internet connection, poor video quality, and audio problems. Moreover, time may both be a barrier as well as a facilitator to implementation [28,30,33,41,45,46,51,52,56]. Some health care professionals perceived digital health services as time saving, whereas others perceived it as an additional burden. This issue involves the lack of time to familiarize with, set up, personalize, and use the technology as well as the time investment required from health care professionals to assist patients. In addition, the lack of a quiet physical space for health care professionals as well as patients specifically for telerehabilitation may be a barrier to implementation [33,44,52,61]. Moreover, the lack of electronic health records may be a barrier to implementation [33].

Readiness for Implementation—Access to Knowledge and Information (High Reliability)

Access of health care professionals and patients to knowledge and information about the use of digital health services may be an important determinant that influences implementation. A health care professionals’ training before using the digital health intervention may be a facilitator to implementation [41,44-47,52,60]. Access for patients to explore the digital health intervention before a consultation and clear instructions in the form of a manual, webinar, videos, or face-to-face support were facilitators to implementation [30,32,40,43,44,46,51].

Domain 4: Characteristics of Health Care Professionals (Knowledge and Beliefs About the Intervention: High Reliability)

Health care professionals’ acceptance of a digital health intervention may both be a facilitator and barrier [29,33,42,44-47,52,54,60,62]. Resistance to change of health care professionals may be a barrier to implementation, but if health care professionals trust that their efforts to embrace change will be worthwhile, this may facilitate implementation. Most health care professionals are open to digital health services, as long as they have appropriate training and time to familiarize with the intervention and its content. If experiences with a digital health intervention exceeds health care professionals’ expectations, this results in intrinsic motivation for the digital health intervention, which promotes implementation. The feeling of maintaining professional autonomy and confidence of health care professionals in being able to deliver the digital health intervention may also facilitate implementation. Concerns about patient information confidentiality, the belief that a digital health intervention will not be as good as face-to-face care, and providing digital health for conditions perceived as low priority may be barriers to implementation related to health care professional acceptance. Moreover, concerns that health care professionals’ job satisfaction may diminish may be a barrier to implementation [48,54,60]. However, if digital health services enable more contact with patients, this is experienced as a promotion of health care professionals’ satisfaction. Another contribution to satisfaction was that digital health services may lead to less physically demanding care compared to usual care, which all may facilitate implementation.

Domain 5: Process

Engaging—Opinion Leaders (Medium Reliability)

Peer opinion leaders exert influence through their representativeness and credibility. When new digital health services are presented to a health care professional by a coworker who vouches for it (peer opinion leader), this may facilitate implementation [56].

Engaging—Key Stakeholders (Health Care Professional; High Reliability)

Involvement of health care professionals in the implementation of digital health services is a facilitating determinant to implementation that promotes confidence in digital health services [60]. Furthermore, the willingness of health care professionals to try digital health services may facilitate implementation [52]. Organizational uncertainties among key stakeholders, such as questions like “Who does it?” and “Who pays for it?” may be barriers to implementation [54]. In addition, setting up a technical support team may lead to feelings of support by the health care professional, which may facilitate implementation [50].

Executing (Medium Reliability)

Executing the implementation of digital health services might require some justification and delegation to key involved stakeholders, such as gym staff [60]. This may be a barrier to implementation as, for example, content of the digital health intervention (eg, specific gym exercises) may not always be conventional.

Discussion

Principal Findings

In this systematic review, barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital health services for people with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting were identified and synthesized according to the CFIR. Barriers and facilitators were identified within all 5 CFIR domains, and almost all constructs or subconstructs of the CFIR with synthesized barriers or facilitators had high reliability. Various stakeholders are involved in the implementation of digital health services for patients with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary care setting. The current determinant analysis provides a generic overview of barriers and facilitators that may be considered by stakeholders, such as digital health intervention developers, health care professionals, health care organizations, health policy makers, health care funders, and researchers, to design fitting implementation strategies [63]. As stakeholders mainly have influence on barriers and facilitators in specific CFIR domains, main results for stakeholders will be presented and discussed accordingly.

Identified barriers and facilitators that may especially be important for developers are from the domain “digital health service characteristics.” Facilitators within this domain include the flexibility of digital health services to tailor to specific patient needs, suitability for various subgroups, and high usability. Digital health service developers can consider these facilitators when developing and evaluating their product by using, for example, an eHealth framework, such as the Center for eHealth Research Roadmap [64]. An example of an existing digital health service that uses some of these facilitators is eHealth platform Physitrack, which was experienced by physiotherapists as user friendly, accessible, and helpful in providing personalized care [65,66]. Intervention design with nonoptimal usability was also identified as a barrier to implementation in other contexts, just as costs [14-17]. In this study, financial aspects, such as loss of income for health care providers because of potential substitution or patient expenses, were also shown to be important barriers to implementation for this specific context. Financial strategies to overcome these barriers when implementing digital health services for the context of patients with chronic illnesses living at home, such as changing the (patient) billing systems and fee structures, were suggested in previous research and may be relevant for developers to consider [67].

Identified barriers and facilitators that are especially important to health care professionals are from the domain “digital health service characteristics” and “outer setting.” A facilitator within the domain “digital health service characteristics” is the relative advantage of digital health over usual care, such as promoting adherence, self-management, empowerment, and access to health care. Important barriers are the concern that digital health services might negatively affect patient–health care professional relationship and quality of care, experienced additional burden of digital health services, and change of treatment routines. Existing workflow was also shown to be an important barrier in other contexts [16]. To use these facilitators and overcome these barriers, health care professionals might consider using previously developed implementation strategies used in another context, such as conducting educational meetings to train and educate colleague health professionals or conducting cyclical small tests of change [68]. Personal traits of patients, such as digital literacy, maladaptive illness perceptions, poor communication skills, and lack of confidence in the patient’s own physical ability, are barriers from the “outer setting.” An example of a previously developed tool for physiotherapists is the use of the Checklist Blended Physiotherapy [69]. This clinical decision aid to support the physiotherapist in the decision of whether a digital health service should be an integral part of physiotherapy treatment for an individual patient might be a strategy, which has yet to be evaluated.

Identified barriers and facilitators that are especially important to health policy makers are mostly from the domain “outer setting.” The lack of health care guidelines and lack of an external financial incentive were identified as barriers. The World Health Organization developed guideline recommendations on digital health services that can be used to develop guidelines for local contexts [9]. Changing reimbursement policies and clinician incentives are financial strategies that may are recommended to health policy makers [67]. Moreover, broad acceptance of digital health services by patients, health care professionals, and health service funders creates trust for health care professionals that implementation is worthwhile, which may facilitate implementation.

Identified barriers and facilitators that are especially relevant to health care organizations are mostly from the domain “inner setting.” Providing access to knowledge and information about the digital health intervention was found to be an important facilitator. In addition, an opinion leader and involvement of health care professionals facilitates implementation. Therefore, it is suggested that health care organizations consider implementation strategies, such as developing and distributing educational material as well as identifying and preparing champions, and inform local opinion leaders to develop stakeholder interrelationships [68]. Important barriers to overcome are technology-related issues and incompatibility with other initiatives, guidelines, and existing payment structures. Organizational uncertainties, such as questions like “Who does it?” and “Who pays for it?” are barriers to implementation that health care organizations must mainly overcome. To overcome these barriers, health care organizations are suggested to consider new sources of funding, involve executive boards, and try to form or join an innovation network [68].

Researchers can use the generic overview of barriers and facilitators of all domains to prioritize them for a local context, develop implementation strategies, test them, and systematically evaluate implementation outcomes. This is important because determinants are specific to the local context, and local contexts are ever changing [19].

Although several studies have identified barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital health services in other settings than primary care or complex interventions in the primary care setting, this is the first systematic review of studies identifying and analyzing the facilitators and barriers of digital health services for people with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting. The results of this study are consistent with findings in other settings or the general health care setting [70]. Although the findings on the level of CFIR domains or subdomains are comparable to other contexts, the nuance in the description of the identified barriers and facilitators are mostly specific to primary care for patients with musculoskeletal conditions.

A strength of this systematic review is that all included articles had a mixed methods or qualitative design, and end-user perspectives of both patients and health care professionals were included, which led to a rich description of barriers and facilitators. However, it is important to note that many of the included studies did not follow a structured implementation process, and it was not possible to discuss whether implementation duration influenced the participants’ perspectives. Another strength is the use of the CFIR. Synthesizing according to the CFIR makes our findings easier comparable to other implementation studies and supports the use of common terminology in this field. Despite the careful execution of this study, there are some methodological considerations. The quality of the qualitative component was assessed by presenting stars. Cutoff values were determined by the authors; however, these cutoff values are arbitrary, which may have influenced the interpretation of the quality of included articles. In addition, a reliability rating was used to indicate confidence in the findings. While this approach took consistency and quality of the studies into account, we acknowledge that tools such as GRADE-CERQual were not used, which assesses confidence in findings from a more comprehensive perspective, considering factors such as coherence and adequacy. Incorporating GRADE-CERQual or similar methods in future research could enhance confidence in findings of a qualitative data synthesis [71]. The context of this review was digital health services, the primary care setting, and musculoskeletal conditions. People with musculoskeletal conditions are one of the largest patient groups in the primary health care setting. Although this patient group is very heterogenous, there are some transcendent key recommendations for patients with musculoskeletal conditions in primary health care, which makes the context sufficiently specific to inform relevant stakeholders [72]. Specific types of digital health services researched in the included articles were also very heterogenous. Therefore, it was not possible to specify barriers and facilitators to implementation for different types of digital health services. This should be considered when developing implementation strategies for specific digital health services. This systematic review provides a generic overview, and reliability was presented on the level of subconstructs and not on the level of individual determinants. Therefore, a prioritization of determinants should be carried out for the local context, as a first step in designing implementation strategies [19].

Conclusions

This systematic review provides an extensive description of the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital health services for people with musculoskeletal conditions in the primary health care setting. The findings are based on the synthesis of 35 qualitative and mixed methods articles through the CFIR. Barriers and facilitators were identified across all 5 CFIR domains, and nearly all constructs or subconstructs of the CFIR with synthesized barriers or facilitators had high reliability. This suggests that the implementation process can be complex and requires implementation strategies across all CFIR domains. Stakeholders, such as digital health intervention developers, health care professionals, health care organizations, health policy makers, health care funders, and researchers, can consider the identified barriers and facilitators to design tailored implementation strategies after a prioritization has been carried out in their local context.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the authors of all data used in the review.

Abbreviations

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- MMAT

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

Search strategy.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist.

Data Availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021 Dec 19;396(10267):2006–2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32340-0. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(20)32340-0 .S0140-6736(20)32340-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization. 2015. [2024-04-29]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042#:~:text=The%20World%20report%20on%20ageing,new%20concept%20of%20functional%20ability .

- 3.GBD 2019 DiseasesInjuries Collaborators Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020 Oct 17;396(10258):1204–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 .S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 May;29(5):766–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025.29/5/766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005 Oct 03;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16202000 .MILQ409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012:432892. doi: 10.6064/2012/432892. doi: 10.6064/2012/432892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015 Jun;129(6):611–20. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001.S0033-3506(15)00158-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 May;29(5):799–805. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0026.29/5/799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO guideline recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. World Health Organization. [2024-04-29]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541902/ [PubMed]

- 10.Catwell L, Sheikh A. Evaluating eHealth interventions: the need for continuous systemic evaluation. PLoS Med. 2009 Aug 18;6(8):e1000126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000126. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000126 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elbert NJ, van Os-Medendorp H, van Renselaar W, Ekeland AG, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Raat H, Nijsten TE, Pasmans SG. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ehealth interventions in somatic diseases: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res. 2014 Apr 16;16(4):e110. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2790. https://www.jmir.org/2014/4/e110/ v16i4e110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt S, Sephton R, Yeowell G. The effectiveness of digital health interventions in the management of musculoskeletal conditions: systematic literature review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jun 05;22(6):e15617. doi: 10.2196/15617. https://www.jmir.org/2020/6/e15617/ v22i6e15617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kloek CJ, Bossen D, Spreeuwenberg PM, Dekker J, de Bakker DH, Veenhof C. Effectiveness of a blended physical therapist intervention in people with hip osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis, or both: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2018 Jul 01;98(7):560–70. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzy045. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29788253 .4998860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishuris RG, Stewart M, Fix GM, Marcello T, McInnes DK, Hogan TP, Boardman JB, Simon SR. Barriers to patient portal access among veterans receiving home-based primary care: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015 Dec 12;18(6):2296–305. doi: 10.1111/hex.12199. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24816246 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruse CS, Atkins JM, Baker TD, Gonzales EN, Paul JL, Brooks M. Factors influencing the adoption of telemedicine for treatment of military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Med. 2018 May 08;50(5):385–92. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2302. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadjistavropoulos HD, Nugent MM, Dirkse D, Pugh N. Implementation of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy within community mental health clinics: a process evaluation using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Psychiatry. 2017 Sep 12;17(1):331. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1496-7. https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-017-1496-7 .10.1186/s12888-017-1496-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batterham PJ, Sunderland M, Calear AL, Davey CG, Christensen H, Teesson M, Kay-Lambkin F, Andrews G, Mitchell PB, Herrman H, Butow PN, Krouskos D. Developing a roadmap for the translation of e-mental health services for depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015 Sep 23;49(9):776–84. doi: 10.1177/0004867415582054.0004867415582054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009 Aug 07;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 .1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Mar 25;19(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3 .10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012 Nov 27;12(1):181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 .1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016 Dec 05;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009 Jul 21;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19622552 .bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pluye P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 Apr;46(4):529–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009.S0020-7489(09)00014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Souto RQ, Khanassov V, Hong QN, Bush PL, Vedel I, Pluye P. Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015 Jan;52(1):500–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.010.S0020-7489(14)00232-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong QN. Reporting the results of the MMAT. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. [2024-04-29]. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/

- 26.CFIR codebook. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. 2014. [2024-04-29]. https://cfirguide.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/cfircodebooktemplate10-27-2014.docx .

- 27.Bach-Mortensen AM, Lange BC, Montgomery P. Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based interventions among third sector organisations: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018 Jul 30;13(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0789-7. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-018-0789-7 .10.1186/s13012-018-0789-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Vries HJ, Kloek CJ, de Bakker DH, Dekker J, Bossen D, Veenhof C. Determinants of adherence to the online component of a blended intervention for patients with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis: a mixed methods study embedded in the e-Exercise trial. Telemed J E Health. 2017 Dec;23(12):1002–10. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Meer HA, de Pijper L, van Bruxvoort T, Visscher CM, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Engelbert RH, Speksnijder CM. Using e-Health in the physical therapeutic care process for patients with temporomandibular disorders: a qualitative study on the perspective of physical therapists and patients. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 Feb 16;44(4):617–24. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1775900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Tilburg ML, Kloek CJ, Foster NE, Ostelo RW, Veenhof C, Staal JB, Pisters MF. Development and feasibility of stratified primary care physiotherapy integrated with eHealth in patients with neck and/or shoulder complaints: results of a mixed methods study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023 Mar 09;24(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06272-6. https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-023-06272-6 .10.1186/s12891-023-06272-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrozzi MJ, Spencer G, Mackey MG. A process evaluation of the Mind Your Back trial examining psychologically informed physical treatments for chronic low back pain. Chiropr Man Therap. 2021 Aug 17;29(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12998-021-00389-y. https://chiromt.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12998-021-00389-y .10.1186/s12998-021-00389-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Östlind E, Ekvall Hansson E, Eek F, Stigmar K. Experiences of activity monitoring and perceptions of digital support among working individuals with hip and knee osteoarthritis - a focus group study. BMC Public Health. 2022 Aug 30;22(1):1641. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14065-0. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-14065-0 .10.1186/s12889-022-14065-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly M, Fullen BM, Martin D, Bradley C, McVeigh JG. eHealth interventions to support self-management: perceptions and experiences of people with musculoskeletal disorders and physiotherapists - 'eHealth: It's TIME': a qualitative study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2024 May 25;40(5):1011–21. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2022.2151334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renard M, Gaboury I, Michaud F, Tousignant M. The acceptability of two remote monitoring modalities for patients waiting for services in a physiotherapy outpatient clinic. Musculoskeletal Care. 2022 Sep 10;20(3):616–24. doi: 10.1002/msc.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poolman EY, Vorstermans L, Donker MH, Bijker L, Coppieters MW, Cuijpers P, Scholten-Peeters G, de Wit L. How people with persistent pain experience in-person physiotherapy blended with biopsychosocial digital health - a qualitative study on participants' experiences with Back2Action. Internet Interv. 2024 Jun;36:100731. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2024.100731. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214-7829(24)00024-1 .S2214-7829(24)00024-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pereira TA, Santos IB, Mota RF, Fukusawa L, Azevedo-Santos IF, DeSantana JM. Beliefs and expectations of patients with fibromyalgia about telerehabilitation during COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2023 Oct;67:102852. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2023.102852.S2468-7812(23)00137-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Passalent L, Cyr A, Jurisica I, Mathur S, Inman RD, Haroon N. Motivators, barriers, and opportunity for e-Health to encourage physical activity in axial Spondyloarthritis: a qualitative descriptive study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2022 Jan 20;74(1):50–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.24788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ezzat AM, Bell E, Kemp J, O'Halloran P, Russell T, Wallis J, Barton C. "Much better than I thought it was going to be": telehealth delivered group-based education and exercise was perceived as acceptable among people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2022 Sep;4(3):100271. doi: 10.1016/j.ocarto.2022.100271. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2665-9131(22)00039-5 .S2665-9131(22)00039-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamper C, Huijnen I, de Mooij M, Köke A, Verbunt J, Kroese M. An eCoach-pain for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain in interdisciplinary primary care: a feasibility study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Nov 06;18(21):11661. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111661. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph182111661 .ijerph182111661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barton CJ, Ezzat AM, Merolli M, Williams CM, Haines T, Mehta N, Malliaras P. "It's second best": a mixed-methods evaluation of the experiences and attitudes of people with musculoskeletal pain towards physiotherapist delivered telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2022 Apr;58:102500. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102500. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/35074694 .S2468-7812(21)00184-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farzad M, MacDermid J, Ferreira L, Szekeres M, Cuypers S, Shafiee E. A description of the barriers, facilitators, and experiences of hand therapists in providing remote (tele) rehabilitation: an interpretive description approach. J Hand Ther. 2023 Oct;36(4):805–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2023.06.004.S0894-1130(23)00083-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dehainault M, Gaillard O, Ouattara B, Peurois M, Begue C. Physical activity advice given by French general practitioners for low back pain and the role of digital e-health applications: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care. 2024 Jan 29;25(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s12875-024-02284-w. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/38287271 .10.1186/s12875-024-02284-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arensman R, Kloek C, Pisters M, Koppenaal T, Ostelo R, Veenhof C. Patient perspectives on using a smartphone app to support home-based exercise during physical therapy treatment: qualitative study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022 Sep 13;9(3):e35316. doi: 10.2196/35316. https://humanfactors.jmir.org/2022/3/e35316/ v9i3e35316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.M Ezzat A, Kemp JL, J Heerey J, F Pazzinatto M, De Oliveira Silva D, Dundules K, Francis M, J Barton C. Implementation of the good life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D) program via telehealth in Australia: a mixed-methods program evaluation. J Telemed Telecare. 2023 Apr 20;:1357633X231167620. doi: 10.1177/1357633X231167620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Tilburg ML, Kloek CJ, Staal JB, Bossen D, Veenhof C. Feasibility of a stratified blended physiotherapy intervention for patients with non-specific low back pain: a mixed methods study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022 Feb 20;38(2):286–98. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2020.1756015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kloek CJ, Bossen D, de Vries HJ, de Bakker DH, Veenhof C, Dekker J. Physiotherapists' experiences with a blended osteoarthritis intervention: a mixed methods study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020 May 28;36(5):572–9. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1489926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]