Abstract

Very little is understood of the structure of mycoplasma promoters, and this limits interpretation of genomic sequence data in these species. In this study the transcriptional start points of 22 genes of Mycoplasma pneumoniae were identified and the regions 5′ to the start point compared. Although a strong consensus –10 region could be seen, there was only a weak consensus in the –35 region. A high proportion of transcripts had heterogeneous 5′-ends and characterisation of the sequence of the 5′-ends of two transcripts established that the heterogeneity was derived from initiation of transcription at reduced levels between 1 and 4 bases 5′ to the major starting point. In addition to this apparently unique feature, a high proportion of transcripts lacked a 5′ untranslated leader region that could contain a ribosomal binding site. Such leaderless transcripts are seen rarely in other bacterial species. Although the promoter regions for a number of members of lipoprotein multigene families were examined, no obvious explanation for regulation of expression was apparent. Using the data from this study an improved matrix for prediction of M.pneumoniae promoters was derived. Application of this matrix to the sequences immediately 3′ and 5′ to each predicted start codon in the genome suggested that most M.pneumoniae transcriptional start points were likely to occur between 5 and 30 bases 5′ to the start codon.

INTRODUCTION

Completion of the genomic sequence of several Mycoplasma species has focussed attention on control of gene expression in these bacteria. The genomic sequences of both Mycoplasma genitalium and Mycoplasma pneumoniae lack several major regulators of gene expression, including two component regulatory systems and multiple σ factors (1–3). In addition, the high A+T content of their genomes has been found to result in adventitious promotion of transcription when fragments of their genomic DNA have been introduced into Escherichia coli (4). Thus it appears that the signals for promotion and regulation of transcription may differ significantly from other bacteria.

Prediction of promoter sequences has been predominantly based on the extensive set of data available for E.coli. These data have been used to derive a matrix for scoring each base of potential promoter sequences, with the cumulative total of the scores for bases used to identify the sequences most likely to contain promoters. One approach that has been suggested for adaptation of these data for use in different bacterial species is to adjust the matrix to account for the G+C content of the chromosome under examination (5). Given the low G+C content of mycoplasma genomes, this may be one approach to improving the identification of promoters in sequence data.

Recognition of mycoplasma promoters in sequence data is severely limited by the dearth of experimentally characterised promoters in this genus. Only 10 transcriptional start points have been identified experimentally in M.pneumoniae, those for the 16S rRNA, the 4.5S RNA, the 10S RNA, the P1 operon, the gene encoding P65, the operon encoding the 116 kDa surface protein and four located within the hmw gene cluster (6–13). In addition, very few promoters have been characterised in other Mycoplasma species. This lack of information severely limits the interpretation of genomic sequence data. Given the lack of suitable systems for genetic analysis of mycoplasma promoters, a clearer picture of their common features is likely to be gained by two complementary experimental approaches. Identification of transcriptional start points for a larger number of genes will allow comparison of the regions immediately 5′ to these regions to identify consensus sequences. Once this information is available, analysis of coordinately regulated genes may enable the identification of features of promoter regions which contribute to control of expression. Thus the aim of the study reported in this paper was to increase the amount of descriptive data on mycoplasma promoters, primarily by locating transcriptional start points, and to examine these for unusual features of mycoplasma promoters, then to apply these data to the development of a refined model for prediction of promoter regions in other sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and growth conditions

Mycoplasma pneumoniae strain M129, at the twenty-third passage in broth culture (2), was used for all studies. The cultures were grown in 175 cm2 tissue culture flasks in modified Hayflick broth medium at 37°C until a colour change was evident in the medium.

RNA purification

Total M.pneumoniae RNA was extracted by the guanidinium isothiocyanate method using the Roti-Quick kit (Roth). RNA larger than 200 bases was extracted using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). With both methods, adherent mycoplasma cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline, 2 ml of the guanidinium isothyocyanate lysis solution added directly to the flasks, and the flask surface then scraped to ensure that cellular material was dissolved in the lysis solution. RNA was then purified from the lysis solutions according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Primer extension

Generally the genes chosen for analysis were either members of lipoprotein multigene families, or were genes found to be transcribed at a range of levels on the basis of whole genome transcriptional analysis (Table 1; H.W.H.Göhlmann and C.-U.Zimmermann, unpublished data). Using macroarray technology short gene-specific PCR products were immobilised on nylon filters and probed with α-32P-labelled cDNA, synthesised from whole cell RNA extracts using gene-specific primers. Transcriptional start points were identified by primer extension. In all cases the transcriptional start points identified were confirmed by a second extension reaction using a different oligonucleotide. The oligonucleotides used are listed in Table 2. Oligonucleotides were labelled by 5′-end phosphorylation using [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer Mannheim) (14). Primer extension was done essentially as described previously (8), with a reaction containing 1 pmol labelled oligonucleotide, 10–90 µg total RNA, 1 mM of each dNTP and 25 U of AMV reverse transcriptase (Boehringer Mannheim) in a 20 µl vol of the buffer supplied by the manufacturer. The oligonucleotide and the RNA were mixed and ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in 10 µl of buffer. This mixture was incubated at 70°C for 5 min and slowly cooled to 42°C. The other components of the reaction were then added, and the reaction incubated at 42°C for 60 min. The reaction was stopped by incubation at 95°C for 5 min, formamide loading buffer added and the reaction products separated in polyacrylamide sequencing gels. The gels were then dried and autoradiographed. Primer extension products were measured by separation next to sequencing reactions generated with the same labelled oligonucleotide using the Thermosequenase kit (Amersham). The templates used for sequencing reactions were cosmid clones of the M.pneumoniae genome containing the sequence of interest.

Table 1. Genes analysed for position of transcriptional start point.

| Genea | Position | Name | Prevalence of transcriptsb | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 003 (MPN152) | 6641–4257 | E07_orf794 | Low | Putative lipoprotein family 2 |

| 058 (MPN097) | 81 440–79 815 | R02_orf541 | Medium | Putative lipoprotein family 2 |

| 071 (MPN084) | 100 872–99 298 | R02_orf524 | High | Putative lipoprotein family 1 |

| 072 (MPN083) | 102 523–100 922 | R02_orf533 | High | Putative lipoprotein family 1 |

| 102 (MPN052) | 141 633–139 660 | D09_orf657 | Low | Putative lipoprotein |

| 250 (MPN592) | 306 862–308 427 | D02_orf521 | Medium | Putative lipoprotein family 1 |

| 251 (MPN591) | 308 950–310 011 | D02_orf353V | Medium | Putative lipoprotein family 1 |

| 268 (MPN574) | 325 182–325 532 | D02_orf116 | High | Heat shock protein GroES (groES) |

| 282 (MPN560) | 341 065–342 381 | H03_orf438 | Low | Arginine deiminase (arcA) |

| 311 (MPN531) | 368 909–371 056 | G12_orf715 | High | ATP-dependent protease binding subunit (clpB) homologue |

| 350 (MPN491) | 424 958–423 534 | P02_orf474 | High | Membrane nuclease |

| 381 (MPN459) | 460 960–462 735 | H08_orf591 | Low | Putative lipoprotein family 4 |

| 396 (MPN444) | 481 119–485 096 | H08_orf1325 | Medium | Putative lipoprotein family 3 |

| 438 (MPN401) | 539 611–540 093 | F11_orf160 | Medium | Transcription elongation factor (greA) |

| 443 (MPN396) | 546 644–549 307 | F11_orf887 | Medium | SecD-like |

| 446 (MPN393) | 551 403–552 479 | F11_orf358a | Medium | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1–α subunit (pdhA) |

| 461 (MPN376) | 569 863–573 285 | A19_orf1140 | High | Unknown function |

| 528 (MPN309) | 658 627–657 410 | F10_orf405 | Low | Protein P65 |

| 533 (MPN304) | 663 675–662 959 | H10_orf238 | High | Arginine deiminase (arcA) truncated |

| 548 (MPN288) | 678 142–675 779 | A65_orf787o | Low | Putative lipoprotein |

| 555 (MPN281) | 691 498–689 789 | A65_orf377 | Medium | Putative lipoprotein family 2 |

| 564 (MPN271) | 701 122–700 367 | A65_orf251a | Low | Putative lipoprotein family 5 |

aThe gene nomenclature and numbering published by Himmelreich et al. (2) has been used, with the new nomenclature (15) shown in brackets.

bRelative abundance of transcripts of this gene in M.pneumoniae cells cultured at 37°C in modified Hayflick broth as determined by hybridisation of radiolabelled cDNA of whole cell RNA to dot blots of PCR products representative of each of the ORFs in the genome (30; H.W.H.Göhlmann and C.-U.Zimmermann, personal communication, preliminary data).

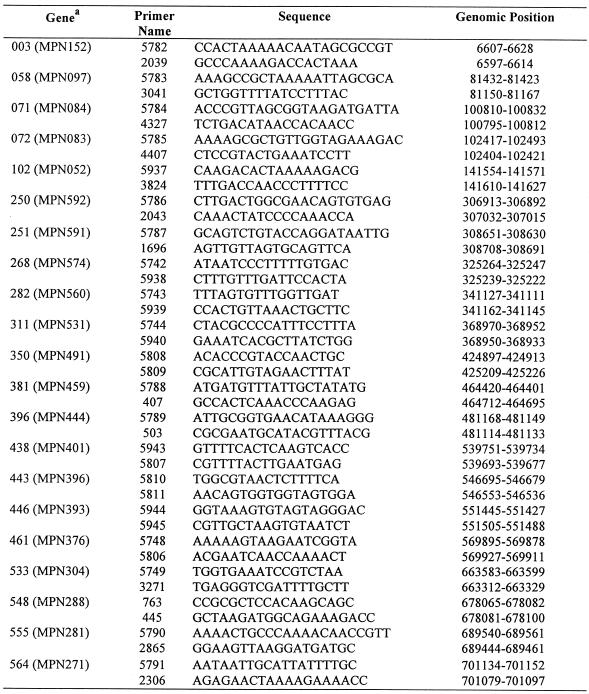

Table 2. Oligonucleotides used for primer extension analyses.

a The gene nomenclature and numbering published by Himmelreich et al. (2) has been used, with the new nomenclature (15) shown in brackets.

Primer extension with specific dNTPs

The identity of the bases occurring at the heterogeneous 5′-ends of transcripts for genes 071 (MPN084) and 072 (MPN083) was determined by extension of oligonucleotides complementary to the 5′-end of the transcript, with the 3′-end of the oligonucleotide complementary to the second base of the most abundant transcript. The primer extension reactions were done essentially as described above, except that 12 reactions were done with each oligonucleotide. These 12 reactions contained either 5 µM of one of the four dNTPs, 5 µM of all possible pairs of the four dNTPs, 5 µM of all four dNTPs or no dNTPs. Reaction products were then separated in a 20% denaturing acrylamide gel and the gel autoradiographed.

Statistical analysis of putative promoter sequences

Putative promoter sequences were predicted by examining the region 5′ to the transcriptional start points identified by primer extension using the matrices of Hertz and Stormo (5), which are based on data from E.coli promoters, adjusted to account for the mean G+C content of those sequences (32.18%). These matrices define three regions in a putative promoter, the start point of transcription (the +1 region), the –10 region, and the –35 region, with each separated by a gap. As the position of the +1 region was known from the experimental data, the matrices were used to define potential –10 and –35 regions. Using the sequences of the regions identified using this matrix, as well as the experimentally defined +1 region, a new matrix was derived. The scores for each base at each position were calculated by determining log10(fo/fe), where fe is the expected and fo the observed nucleotide frequency, with fe based on the G+C content. The scores for the gap between the –10 and –35 regions were determined by calculating the logarithm of the ratio of the observed frequencies of the different gap lengths. The average scores obtained with this revised matrix for all possible transcriptional starts of all 649 open reading frames (ORFs) without known transcription starts commencing from 100 bases 3′ to the start codon and extending to 100 bases 5′ to the start codon were determined to examine the distribution of putative promoter sequences. For each analysis the expected G+C content in the matrices was adjusted to that observed for the sequence being analysed. The gap between the +1 and –10 core regions was allowed to vary from 1 to 7 bases, and the gap between the –10 and the –35 core regions was allowed to vary from 15 to 19 bp.

Determining the ribosomal binding sequences (RBS)

A similar matrix approach was used to search for all sequences complementary to the 3′-end of the 16S rRNA within a set of 677 sequences, consisting of the 50 bp immediately 5′ to each predicted start codon. The matrix was simplified, with a score of 2 for each G/C consensus, 1 for each A/T consensus and 0 for no consensus. The sequence yielding the highest score was determined for each gene, and the resulting sequences were sorted according to their scores. The highest scoring sequences were manually aligned to search for a consensus sequence. In addition, the 50 bases 5′ to each start codon were examined for any frequently occurring hexamer patterns.

Nomenclature

We have used the nomenclature and numbering system for ORFs as published by Himmelreich et al. (2). To avoid confusion with the annotation of GenBank the prefix MP has been omitted. The GenBank MP1–MP677 designations do not always agree with the numbering from the original paper (2). A reannotation of M.pneumoniae has been published this year (15), therefore we have also included the new nomenclature in brackets with the prefix ‘MPN’. For example, 311 (MPN531) has the number 311 in the original nomenclature, MP311 in GenBank, and MPN531 in the new nomenclature.

RESULTS

Consensus features of M.pneumoniae promoters

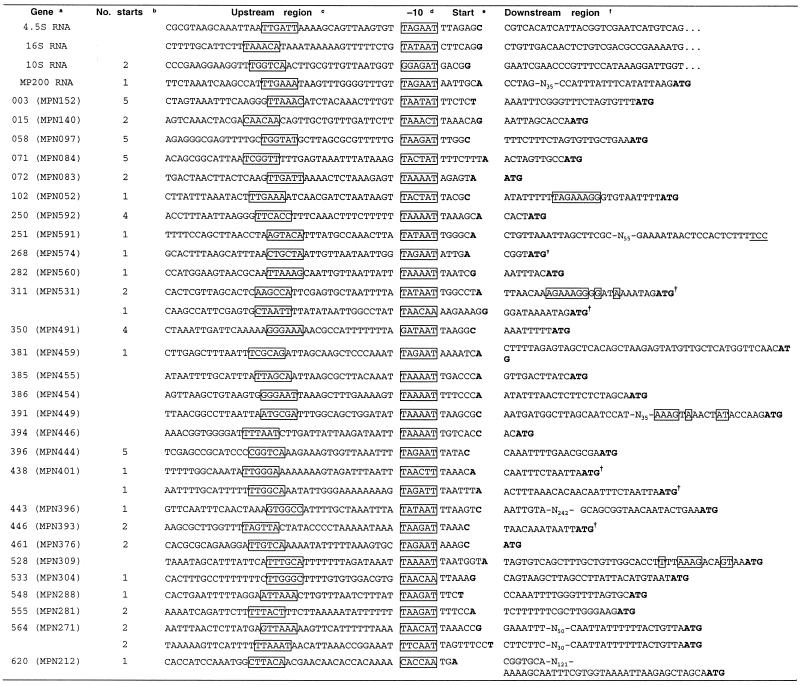

In total the transcriptional start points for 22 genes were identified, representing 3% of those present in the M.pneumoniae genome (Table 3). Alignment of the start points and examination of the regions 50 bases immediately 5′ to them identified several possible –10 region promoter sequences: TA(AGT)AAT, TAA(GT)AT, TACTAT and TATTAA (Table 3). While there was no strong consensus in the –35 region, the sequences which conformed closest to the consensus –35 regions of E.coli, once adjusted for the G+C content of the M.pneumoniae genome, occurred between 15 and 20 bases 5′ to the start of the –10 region and the sequence TTGA was found to be relatively conserved. In most cases the region immediately 5′ to the –10 region was AT rich and contained polyadenosine or polythymidine tracts of between 3 and 6 residues. The majority of transcripts had an adenosine residue as their major initiation base.

Table 3. Promoter regions defined in M.pneumoniae.

aFor genes 311 (MPN531), 438 (MPN401) and 564 (MPN271) two different transcriptional start points were observed.

bNumber of alternative start points of transcription immediately 5′ to the major start point (only for experimental data in this study).

cPutative –35 regions are boxed.

dPutative –10 regions are boxed.

eMajor base for initiation of transcription is shown in bold.

fStart codon for gene is shown in bold and putative RBSs are boxed. For gene 251 (MPN591) the position of the codon homologous to the start codon in other members of the lipoprotein gene family, based on multiple sequence alignments, is underlined, even though it is not a conventional start codon.

†The N-terminal peptide sequences have previously been determined for these genes (15).

Transcriptional start points for genes 015 (MPN140) (P1 operon) (10), 385 (MPN455), 386 (MPN454), 391 (MPN449), 394 (MPN446) (hmw gene cluster) (9), 528 (MPN309) (P65) (11), 620 (MPN212) (operon encoding 116 kDa protein) (8), 4.5S RNA (13), 16S rRNA (6) and MP 200 RNA (12) have been published previously.

The gene nomenclature published by Himmelreich et al. (2) has been used, with the new nomenclature (15) shown in brackets.

Identification of an extended RBS

Although a clear Shine–Dalgarno sequence (that is, a sequence complementary to the 3′-end of the 16S RNA) could be seen only in about 20 M.pneumoniae genes (data not shown), there was an extended sequence weakly conserved in about 60 other genes, including four which were examined experimentally in this work (Table 3). These sequences, when aligned, yielded the consensus sequence AAGAAAGGAGGTATT, complementary to 11 of the 14 bases at the 3′-end of the 16S rRNA (ATCACCTCCTTTCTA).

High frequency of heterogeneous start points

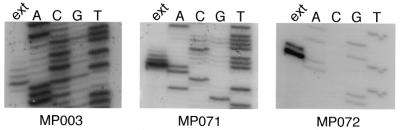

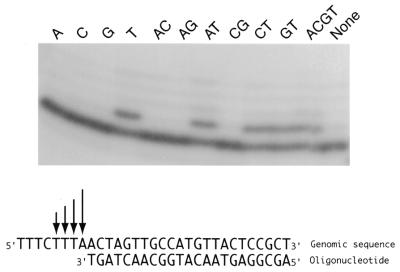

A prominent feature of many of the primer extension reactions was that they had heterogeneous 3′-ends, with the smallest product the most abundant, and then between one and four additional products of decreasing abundance, each 1 base longer than the preceding product (Fig. 1). The genes for which this heterogeneity was observed, and the number of products seen, are shown in Table 3. The abundance of each of the heterogeneous products was found to be ~70% of that of the product 1 base shorter than it (Fig. 1). In each case the same heterogeneity was seen with both oligonucleotides used for primer extension. This ladder of extension products strongly suggested a heterogeneous start point for transcription of these genes. The sequence of the heterogeneous products was characterised for two genes. In gene 071 (MPN084), with a ladder of five products, an oligonucleotide with its 3′-end immediately adjacent to the 5′-end of the major product could be extended in the presence of dTTP, but not when only dATP, dCTP or dGTP were present. However, in most cases the extension was only by a single base. In the presence of all possible pairs of dNTPs, extension to form the longer products only occurred in the presence of both dTTP and dATP (Fig. 2). Similarly, with the transcript for gene 072 (MPN083), which had a ladder of two products, an oligonucleotide with its 3′-end immediately adjacent to the 5′-end of the major product was extended by 1 base only in the presence of dTTP, and by 2 bases when both dTTP and dATP were present. Thus the heterogeneous 5′-ends appear to be derived by initiation over a range of bases on the genomic template.

Figure 1.

Autoradiograph of primer extension products of selected M.pneumoniae transcripts showing the pattern of heterogeneous starts seen with some transcripts [those for 003 (MPN152), 071 (MPN084) and 072 (MPN083)]. The products obtained by primer extension are shown in the lanes labelled ext.

Figure 2.

Primer extension of the transcripts from gene 071 using a primer complementary to the sequence adjacent to the heterogeneous start of the transcripts. The genomic sequence either side of the transcriptional starts is shown at the bottom of the figure, as is the sequence of the complementary oligonucleotide used for primer extension. The four start points are indicated with arrows above the genomic sequence, with the length of the arrows indicating the relative abundance on the different length transcripts (see Fig. 1). In the upper half of the figure is an autoradiograph of the products obtained with the oligonucleotide when extension was performed only in the presence of a single dNTP (A, C, G, T), in the presence of pairs of dNTPs (AC, AG, AT, CG, CT, GT), in the presence of all four dNTPs (ACGT) or in the absence of any dNTPs (None). The oligonucleotide was only extended in the presence of dTTP (T, AT, CT, GT, ACGT). In the presence of dTTP alone, the primer was only extended by 1 base, but in the presence of dATP and dTTP (AT and ACGT) some extension by 2, 3 or 4 bases was also apparent, indicating that the longer transcripts had 5′-ends identical to the genomic sequence. A fifth start point was identified in other primer extensions for this gene (Fig. 1), but the fifth product was not sufficiently abundant to be detected in this experiment.

High frequency of leaderless transcripts

Four of the transcripts identified had initiation sites within 6 bases of the start codon for the gene they encoded. In two cases [genes 072 (MPN083) and 250 (MPN592)] the gene encoded a lipoprotein signal sequence, thus enabling the localisation of the start codon to be identified with some confidence. In four further cases [genes 268 (MPN574), 311 (MPN531), 438 (MPN401) and 446 (MPN393)] the N-terminal peptide sequences have previously been determined (16) and confirmed that translation commenced at the point shown in Table 3. The distance from the major initiation base to first base of the start codon is shown for all genes in Table 3.

Development of a model for prediction of mycoplasma promoter sequences

The aligned sequences of the +1 region, and the –10 and –35 regions predicted by the G+C content adjusted E.coli matrices, were used to derive the matrices shown in Table 4. These matrices show the logarithm of the likelihood of finding a specific base at each position in these three regions. The mean and standard deviation of the best scores obtained with these matrices on 111 base long sequences for each ORF (starting from base –100 to base +10 relative to the start codon and excluding those used to derive the matrix) in the M.pneumoniae genome are shown in Table 5. To provide a control for false positives, these scores were compared to those obtained with 649 randomly chosen 111 base long sequences from within the ORFs in the M.pneumoniae genome. The scores obtained with the sequences 5′ to the start codons were significantly higher than those obtained with ORF sequences. In contrast the scores obtained using the matrices based on E.coli data (5), whether adjusted for the G+C content of the M.pneumoniae genome (40.23%), that of the sequences 5′ to each ORF (36.11%), or that of the ORF sequences (32.18%) did not differ between the two sequence sets.

Table 4. Promoter sequence matrices based on experimentally determined M.pneumoniae promoters.

| A | C | G | T | Consensusa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 region | –0.16879 | 0.230441 | 0.007298 | –0.05101 | C |

| –0.86194 | 0.566914 | 0.325752 | –0.45648 | C | |

| 0.459816 | 0.230441 | –0.12623 | –1.14962 | A | |

| 0.316715 | 0.492806 | –0.68585 | –0.6388 | C | |

| 0.390823 | –0.28038 | –0.68585 | 0.149661 | A | |

| 0.316715 | –2.07214 | 0.007298 | 0.316715 | A/T | |

| –0.30233 | –0.68585 | –0.97353 | 0.796288 | T | |

| 0.149661 | –1.379 | –0.28038 | 0.524354 | T | |

| 0.05435 | –0.97353 | –0.97353 | 0.696204 | T | |

| 0.316715 | –0.12623 | –0.46271 | 0.05435 | A | |

| 0.459816 | –0.68585 | –0.46271 | 0.149661 | A | |

| 0.149661 | 0.007298 | –0.28038 | 0.05435 | A | |

| –10 region | –0.16879 | –0.46271 | 0.125081 | 0.316715 | T |

| 0.149661 | –0.12623 | 0.007298 | –0.05101 | A | |

| –0.16879 | –0.46271 | –1.379 | 0.747498 | T | |

| 0.236672 | –0.97353 | 0.007298 | 0.236672 | A/T | |

| 0.796288 | –0.68585 | –0.68585 | –0.45648 | A | |

| 0.236672 | –0.46271 | –1.379 | 0.524354 | T | |

| 0.236672 | –1.379 | –0.46271 | 0.524354 | T | |

| 0.390823 | –1.379 | –2.07214 | 0.642137 | T | |

| 0.236672 | –6.67731 | 0.230441 | 0.316715 | T | |

| –0.30233 | –1.379 | –0.68585 | 0.842808 | T | |

| –2.24824 | –2.07214 | –1.379 | 1.185753 | T | |

| 1.248273 | –6.67731 | –2.07214 | –2.24824 | A | |

| 0.642137 | –0.68585 | –0.12623 | –0.45648 | A | |

| 0.88726 | –0.68585 | –0.46271 | –1.14962 | A | |

| 1.185753 | –2.07214 | –6.67731 | –1.14962 | A | |

| –1.55509 | –6.67731 | –6.67731 | 1.248273 | T | |

| –0.45648 | –1.379 | –2.07214 | 1.009862 | T | |

| 0.642137 | –6.67731 | –0.12623 | 0.05435 | A | |

| 0.696204 | –0.68585 | –0.46271 | –0.30233 | A | |

| –35 region | 0.05435 | 0.325752 | –2.07214 | 0.316715 | C |

| 0.390823 | –0.12623 | –0.46271 | –0.05101 | A | |

| 0.05435 | –0.46271 | –0.28038 | 0.390823 | T | |

| 0.459816 | –0.68585 | –0.12623 | –0.05101 | A | |

| 0.149661 | 0.007298 | –0.28038 | 0.05435 | A | |

| –0.16879 | 0.007298 | 0.007298 | 0.149661 | T | |

| –0.45648 | 0.125081 | –0.28038 | 0.390823 | T | |

| 0.05435 | –0.68585 | –0.12623 | 0.390823 | T | |

| 0.149661 | 0.125081 | –0.97353 | 0.236672 | T | |

| 0.390823 | –0.68585 | –0.46271 | 0.236672 | A | |

| 0.459816 | –0.97353 | –0.28038 | 0.149661 | A | |

| –0.16879 | 0.125081 | –0.12623 | 0.149661 | T | |

| 0.05435 | –1.379 | –0.12623 | 0.524354 | T | |

| 0.149661 | –0.46271 | –0.12623 | 0.236672 | T | |

| –1.14962 | –0.68585 | –0.68585 | 0.929819 | T | |

| –0.86194 | –2.07214 | 0.007298 | 0.842808 | T | |

| –0.45648 | –1.379 | 0.923589 | –0.30233 | G | |

| 0.696204 | –0.28038 | –0.68585 | –0.45648 | A | |

| 0.459816 | 0.412763 | –0.68585 | –0.86194 | A | |

| 0.796288 | –0.97353 | –1.379 | –0.05101 | A | |

| 0.390823 | –0.46271 | –2.07214 | 0.459816 | T | |

| 0.524354 | –0.97353 | –6.67731 | 0.524354 | A/T | |

| 0.236672 | –0.68585 | –0.28038 | 0.316715 | T | |

| 0.316715 | –0.97353 | –0.46271 | 0.390823 | T | |

| 0.236672 | –1.379 | –0.12623 | 0.390823 | T |

The numbers represent the logarithm of fo/fe, where fo is the observed and fe the expected frequency of a given nucleotide at the given position in the sequence, assuming the G+C content of the sequence to be 40%. An online implementation of the matrix algorithm can be found at http://www.zmbh.uni-heidelberg.de/M_pneumoniae/Matrix/.

aThe consensus base is that which occurs most commonly in that position given its expected frequency of occurrence at that position in a genome with 40% G+C.

Table 5. Comparison of highest mean scores for different matrices on coding and 5′ non-coding sequences of M.pneumoniae.

| Matrix | Sequence | Probabilitye | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codingc | 5′ Non-codingd | ||

| Escherichia colia | 2.86 ± 1.86 | 2.82 ± 1.92 | 0.35 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniaeb | –0.42 ± 3.50 | 1.24 ± 3.42 | 2.05 × 10–17 |

aG+C content adjusted E.coli matrix.

bMycoplasma pneumoniae matrix based on experimentally determined transcriptional start sites.

cMean and standard error of best score for 649 randomly selected 100 base sequences from ORFs of M.pneumoniae.

dMean and standard error of best score for the 100 bases 5′ to the start codons of 649 ORFs of M.pneumoniae. The ORFs used to determine the experimental matrices were excluded due to the potential for introduction of bias.

eProbability as determined by one-tailed t-test assuming equal variances that mean scores for coding and non-coding sequences are not significantly different.

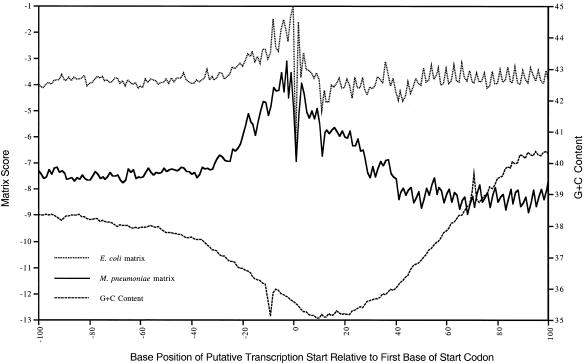

The mean scores yielded by the experimentally determined matrix were compared to those obtained with the G+C content adjusted E.coli matrix for all possible transcriptional start sites on either side of the putative ATG codon of the 649 genes to determine where the highest mean scores were obtained relative to the predicted start codon (Fig. 3). The mean scores obtained with the experimentally determined matrix were highest for putative transcriptional start sites between 5 and 30 bases 5′ to the start codon, and a pronounced increase in scores for putative transcriptional start sites was observed from 10 bases 3′ to 50 bases 5′ to the ATG codon. There was no obvious positional distribution of scores produced using the E.coli based matrices.

Figure 3.

Positional bias of mean scores obtained with the experimentally determined M.pneumoniae matrix and the G+C content adjusted E.coli matrix from 100 bases 3′ to 100 bases 5′ to the start of each ORF (excluding the ORFs used to determine the matrix). The points plotted show the score for the putative transcriptional initiation point relative to the first base of the initiation codon of each ORF, with the best scores obtained with the sequence from 30 bases 5′ to 10 bases 3′ of that point. For each point the M.pneumoniae matrix was adjusted to account for the local GC contents.

Furthermore, application of the M.pneumoniae promoter matrix to sequences 5′ to the start codon of characterised genes in other mycoplasma species established that it was able to correctly identify previously characterised transcriptional start points, including those for the pMGA gene in Mycoplasma gallisepticum and the vlhA gene in Mycoplasma synoviae (17,18).

DISCUSSION

Heterogeneous initiation sites in M.pneumoniae

Several unusual features of transcription in M.pneumoniae have been elucidated in this study. A high proportion of the transcripts examined were found to have heterogeneous start points. Previous studies have also observed heterogeneous start points in some M.pneumoniae transcripts, specifically those for genes 015 (MPN139), 391 (MPN449) and 528 (MPN309) (9–11). Although transcripts with heterogeneous 5′-ends have been identified in other bacteria (19–23), these differ from those reported in this study. The heterogeneous transcripts in other bacteria fall into one of two classes. The first is where there are alternative start points serving as a regulatory mechanism, with one of the two forms of the transcript translationally competent. An example of such a mechanism is seen in the pyrC and pyrD promoters in E.coli and Salmonella typhimurium, with four alternative points for transcript initiation, between 6 and 9 bases from the –10 box of the promoter. Switching between the alternative start sites is regulated by the abundance of intracellular cytosine triphosphate (CTP), with a longer transcript, which starts with a cytosine residue, the predominant product when CTP concentrations are high. The longer product forms a stable hairpin structure at the 5′-end which inhibits translational initiation (19–21). The 2 base shorter transcript which predominates when CTP concentrations are low is unable to form the hairpin and is efficiently translated. The second class described results in a ladder of transcripts, as seen in this study, but the heterogeneity results from transcriptional slippage during initiation at a start site which is part of a polynucleotide tract (22,23). The heterogeneous 5′-ends of these transcripts are not templated, but result from reiterative incorporation of the starting base of the transcript. In contrast the heterogenous M.pneumoniae transcripts examined had 5′-ends which were identical to the genomic sequence, and the initiation codon was not included in a polynucleotide tract. There were no obvious correlations between the sequence of the promoter or initiation regions of the genes and the occurrence of heterogeneous 5′-ends. The unusual features and frequency of the heterogeneous transcripts of M.pneumoniae are suggestive of atypical aspects of transcriptional initiation in mycoplasmas and may be related to the unusually long sequence of the only σ factor identified in the M.pneumoniae genome. Although it is possible that the different initiation sites might be preferentially used under different conditions, the shortest transcript was the most abundant in all genes examined in this study, even though the initiating base differed.

Transcription from multigene families

Ten of the promoter regions identified in this study were from members of multigene families encoding lipoproteins. Genes 071 (MPN084), 072 (MPN083), 250 (MPN592) and 251 (MPN591) are members of the first family, genes 003 (MPN152), 058 (MPN684) and 555 (MPN281) are members of the second family, gene 396 (MPN445) is a member of the third family, gene 381 (MPN459) is a member of the fourth family and gene 564 (MPN271) is a member of the fifth family. None of the members of the sixth lipoprotein gene family, containing genes 195–203, was sufficiently highly expressed to detect transcriptional start points, although this was attempted for all members. In other Mycoplasma species the expression of such families of lipoprotein genes has been shown to be controlled by reversible alterations in the genomic sequence. These have included expansion and contraction of polynucleotide tracts between the –10 and –35 regions (24), expansion and contraction of trinucleotide repeats 5′ to the promoter region (17) and multiple site specific recombination events bringing the promoter and 5′ coding sequence into apposition with different 3′ coding regions (18,25). There was no evidence that any of these mechanisms were likely to play a role in differential regulation of the lipoprotein gene families in M.pneumoniae. Examination of the promoter regions of both the characterised members of these families and the homologous regions of other members of the families failed to identify a difference that might explain their differential expression. However, the occurrence of polynucleotide tracts in the region immediately 5′ to the –10 region, and the variable distance between the best fit to the consensus –35 region and the –10 region, suggests that the potential for expansion and contraction of these tracts should be investigated. Future studies of expression of these gene families will need to examine whether the different family members are indeed regulated at the transcriptional level.

Unleadered transcripts

The high frequency of transcripts which started within 6 bases of the start codon of the gene could be expected in a minimal bacterial genome as it may reduce the genomic space required for initiation of translation. While unleadered transcripts have been observed in a range of unrelated bacterial species (26), they are regarded as exceptional, with only 30 reported in all bacterial species. The unleadered transcript of gene 461 (MPN376), which was confirmed in our study, has been reported previously in M.pneumoniae (4). There were no unique features apparent in the region immediately 3′ to the start codon in the genes transcribed without a leader region. Studies on unleadered transcripts in E.coli have suggested that the most efficient translation occurs when the first base of the transcript is the adenosine residue of the start codon and have also suggested that a cognate AUG codon is required for efficient initiation of translation (26). Recent studies in E.coli have suggested that the start codon of leaderless mRNAs is recognised by a 30S ribosome-formylMet tRNA-initiation factor 2 complex, a structure analogous to that formed during translation initiation in eukaryotes (27). Although it is feasible that this feature and the heterogeneous lengths of the transcripts could facilitate some translational control of expression analogous to that seen in pyrC and pyrD in E.coli and S.typhimurium, no correlation could be found between the presence of heterogeneous 5′-ends and the lack of a leader region.

Definition of mycoplasma promoters

A key aim of this study was a better definition of mycoplasma promoter sequences. With the results of our study and those of previous studies (Table 3), the promoter regions from 32 genes have now been compared and a strong consensus –10 region can be defined. While it remains difficult to describe a consensus –35 box, the derivation of a matrix for this region does enable the definition of a likely region. Previous studies have not been able to detect this conservation in the –35 region (9), probably because there have been insufficient data to identify the weaker level of conservation present. Although definition of promoter regions has also been difficult in Bacillus subtilis it has been attributed to the presence of multiple σ factors (28). In M.pneumoniae, with only a single σ factor, it is surprising to find so much variation in this region. It may be that this reflects a more complex process of transcriptional initiation than might be expected. Transcription from an extended –10 region, which can function independently of a –35 region, has been described in Streptococcus pneumoniae (29) but we have found no evidence of strong conservation of sequences immediately 5′ to the –10 region. The experimental approach to test the importance of the –35 region by mutagenesis and analysis of the resulting promoter activities in vivo is presently not possible for M.pneumoniae, as a plasmid based transformation system does not exist.

The application of the matrix to all M.pneumoniae ORFs demonstrated that the region from 100 to 25 bases 5′ to the translational initiation codon was most likely to contain putative promoters. The demonstration that the matrix produced significantly higher scores with sequences 5′ to ORFs than with sequences drawn at random from the ORFs, even allowing an adjustment for the lower G+C content of the ORF sequences, supports the contention that it was recognising promoter sequences. This was further supported by the failure of the G+C content adjusted E.coli matrix to distinguish between coding and 5′ non-coding sequences.

In addition to facilitating studies of transcription in M.pneumoniae, the promoter matrices we have defined using the experimentally determined M.pneumoniae transcriptional starts have clear utility in other Mycoplasma species as the matrices were able to identify promoter regions in some other species. An implementation of the matrices suitable for searching new sequences, and a complete listing of 677 promoter regions predicted by it in M.pneumoniae, can be found at http://www.zmbh.uni-heidelberg.de/M_pneumoniae/Matrix/.

In conclusion, this study has identified a number of unusual features of transcripts in M.pneumoniae, and has provided much greater definition of the promoter region of this species. Features which appear infrequently in other bacterial species, including heterogeneous start points for transcription and lack of an untranslated leader region containing a ribosomal binding site, appear to be common in M.pneumoniae. These observations, the common occurrence of an extended ribosomal binding region, if such is present at all, and the lack of a strong consensus –35 region in the mycoplasma promoter region suggest that there may be mechanisms involved in initiation of transcription and translation in mycoplasmas that cannot be explained on the basis of our current understanding. Furthermore, the apparent absence of environmentally sensitive regulatory genes in M.pneumoniae is more likely to be a reflection of current knowledge than of an unchanging environment in the respiratory tract, which is the preferred site of colonisation by this bacterium. Novel mechanisms for regulation of gene expression, at both transcriptional and translational levels, are likely to be elucidated by further studies of gene expression in M.pneumoniae.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank H. W. H. Göhlmann and C.-U. Zimmermann for providing data from transcriptome analysis, and Elsbeth Pirkl for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by the Graduiertenkolleg ‘Pathogene Mikroorganismen: Molekulare Mechanismen und Genome’, a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (He 780/10-1) and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. G.F.B. was supported by an Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fraser C.M., Gocayne,J.D., White,O., Adams,M.D., Clayton,R.A., Fleischmann,R.D., Bult,C.J., Kerlavage,A.R., Sutton,G., Kelley,J.M. et al. (1995) Science, 270, 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Himmelreich R., Hilbert,H., Plagens,H., Pirkl,E., Li,B.-C. and Herrmann,R. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 4420–4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himmelreich R., Plagens,H., Hilbert,H., Reiner,B. and Herrmann,R. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 701–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhandayuthapani S., Rasmussen,W.G. and Baseman,J.B. (1998) Gene, 215, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hertz G.Z. and Stormo,G.D. (1996) Methods Enzymol., 273, 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman H.C., Gafny,R., Glaser,G. and Razin,S. (1988) Gene, 73, 175–183.2468577 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proft T., Hilbert,H., Layh-Schmidt,G. and Herrmann,R. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 3370–3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy M.F., Walker,I.D. and Browning,G.F. (1997) Microbiology, 143, 3391–3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldo R.H. III, Popham,P.L., Romero-Arroyo,C.E., Mothershed,E.A., Lee,K.K. and Krause,D.C. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 4978–4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inamine J.M., Loechel,S. and Hu,P.C. (1988) Gene, 73, 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krause D.C., Proft,T., Hedreyda,C.T., Hilbert,H., Plagens,H. and Herrmann,R. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 2668–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Göhlmann H.W., Weiner,J.,III., Schön,A. and Herrmann,R. (2000) J. Bacteriol., 182, 3281–3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoneau P. and Hu,P.C. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 627–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 15.Dandekar T., Huynen,M., Regula,J.T., Ueberle,B., Zimmermann,C.U., Andrade,M.A., Doerks,T., Sanchez-Pulido,L., Snel,B., Suyama,M. et al. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3278–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Proft T. (1995) PhD Thesis, Universität Heidelberg, Germany.

- 17.Glew M.D., Baseggio,N., Markham,P.F., Browning,G.F. and Walker,I.D. (1998) Infect. Immunol., 66, 5833–5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noormohammadi A.H., Markham,P.F., Kanci,A., Whithear,K.G. and Browning,G.F. (2000) Mol. Microbiol., 35, 911–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorensen K.I., Baker,K.E., Kelln,R.A. and Neuhard,J. (1993) J. Bacteriol., 175, 4137–4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson H.R., Chan,P.T. and Turnbough,C.J. (1987) J. Bacteriol., 169, 3051–3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson H.R., Archer,C.D., Liu,J.K. and Turnbough,C.J. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 514–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong X.F. and Reznikoff,W.S. (1993) J. Mol. Biol., 231, 569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner L.A., Weiss,R.B., Driscoll,R., Dunn,D.S. and Gesteland,R.F. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 3529–3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yogev D., Rosengarten,R., Watson-McKown,R. and Wise,K.S. (1991) EMBO J., 10, 4069–4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhugra B., Voelker,L.L., Zou,N., Yu,H. and Dybvig,K. (1995) Mol. Microbiol., 18, 703–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Etten W.J. and Janssen,G.R. (1998) Mol. Microbiol., 27, 987–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grill S., Gualerzi,C.O., Londei,P. and Blasi,U. (2000) EMBO J., 19, 4101–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunst F., Ogasawara,N., Moszer,I., Albertini,A.M., Alloni,G., Azevedo,V., Bertero,M.G., Bessieres,P., Bolotin,A., Borchert,S. et al. (1997) Nature, 390, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabelnikov A.G., Greenberg,B. and Lacks,S.A. (1995) J. Mol. Biol., 250, 144–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Göhlmann H.W.H. (1999) PhD Thesis, Universität Heidelberg, Germany.