Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to develop and validate a nomogram for assessing the risk of nosocomial infections among obstetric inpatients, providing a valuable reference for predicting and mitigating the risk of postpartum infections.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was performed on a cohort of 28,608 obstetric patients admitted for childbirth between 2017 and 2022. Data from the year 2022, comprising 4,153 inpatients, were utilized for model validation. Univariable and multivariable stepwise logistic regression analyses were employed to identify the factors influencing nosocomial infections among obstetric inpatients. A nomogram was subsequently developed based on the final predictive model. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was utilized to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the nomogram in both the training and validation datasets.

Results

The gestational weeks > = 37, prenatal anemia, prenatal hypoproteinemia, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), cesarean sction, operative delivery, adverse birth outcomes, length of hospitalization (days) > 5, CVC use and catheterization of ureter were included in the ultimate prediction model. The AUC of the nomogram was 0.828 (0.823, 0.833) in the training dataset and 0.855 (0.844, 0.865) in the validation dataset.

Conclusion

Through a large-scale retrospective study conducted in China, we developed and independently validated a nomogram to enable personalized postpartum infections risk estimates for obstetric inpatients. Its clinical application can facilitate early identification of high-risk groups, enabling timely infection prevention and control measures.

Keywords: Large-scale retrospective study, Obstetric inpatients, Postpartum infections, Risk prediction model, Nomogram

Introduction

During pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, significant changes occur in the anatomical, physiological, and endocrine systems of pregnant women. Particularly during childbirth, the immune function of the body is greatly weakened, making postnatal mothers highly susceptible to infections by bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens [1–3]. The occurrence of nosocomial infections not only affects the recovery of postnatal mothers but also poses a threat to the health of newborns, and in severe cases, can even lead to the death of both the mother and the newborn [4, 5]. Currently, the incidence rate of nosocomial infections in obstetrics departments at medical institutions in other countries ranges from 1.0 to 14.4% [2, 6], whereas in China, it varies from 0.1 to 4.46% [7, 8], influenced by specific hospital characteristics. affected by hospital characteristics. Therefore, preventing nosocomial infections in obstetrics is particularly important.

Prior investigations have elucidated several factors independently linked with nosocomial infections in in obstetrics inpatients. These include maternal age, pre-existing medical conditions (such as diabetes, hypertension, anemia), type of delivery, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), preterm birth, type of surgical incision, prophylactic antibiotics, length of hospitalization [9–14]. Despite extensive research efforts, the identification of risk factors for nosocomial infections in obstetric patients has predominantly relied on studies with relatively small sample sizes, and there remains a notable absence of validation processes for these findings.The need for a reliable and user-friendly tool that can inform clinical decision-making is evident.

Nomograms are graphical models that offer individualized risk estimation, making them valuable tools in the medical decision-making process [15, 16]. Given the limitations of existing research and the necessity of developing more practical prediction tools, this study seeks to develop and validate a nomogram for assessing the risk of nosocomial infections among obstetric inpatients. Through a large-scale retrospective study conducted in China, this research aims to offer a valuable reference for predicting and mitigating the risk of postpartum infections.

Methods

Study design and participants

A retrospective observation study was conducted involving obstetric patients admissions for childbirth. The recruitment spanned from January 2017 to December 2022, with obstetric inpatients enrolled at a Grade A tertiary general hospital in Xiamen, China. We used 24455 patients’ records from January 2017 to December 2021 as the training dataset and 4153 records from January 2022 to December 2022 as the testing dataset to develop training datasets and validation datasets, respectively. Inclusion criteria included: (1) pregnant women hospitalized for childbirth during the specified period; (2) childbirth completed during the hospital stay; (3) complete clinical data. Exclusion criteria included: (1) incomplete clinical data; (2) hospital stay duration less than 24 h; (3) patients with infection before admission.

Clinical information Collection

The primary outcome was in-hospital postpartum infection. The diagnosis of postpartum infections were based on the “Standard for healthcare associated infection surveillance WS/T 312—2023” issued by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China in 2023 [17]. Patients were divided into infection and non-infection groups based on whether or not infection occurred after childbirth completed.

The incidence rate of nosocomial infection indicated the proportion of newly diagnosed nosocomial infections patients among hospitalized patients within a specified time period. The rate of nosocomial infection incidence cases indicated the proportion of newly diagnosed nosocomial infections cases among hospitalized patients within a specified time period.

Based on relevant literature and expert opinions, the following patients’ clinical data before infections were retrospectively collected from the electronic medical record system as observation indicators: (1) prenatal characteristics: age (years), gestational weeks, prenatal anemia, pregnancy with hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, prenatal hypoproteinemia, oligohydramnios; (2) labour characteristics: premature rupture of membranes (PROM), delivery mode, operative delivery, adverse birth outcomes; (3) postnatal characteristics: length of hospitalization (days), ventilator use, central venous catheter (CVC) use, catheterization of ureter.

Sample size consideration

Regarding the sample size, the number of variables was selected in accordance with the rule of having at least 10 events per variable [18]. In the current study, the training dataset included 273 cases of nosocomial infection, and only 10 independent variables were incorporated into the final prediction model. Consequently, our sample size was deemed sufficient for exploring the risk factors and developing the prediction model.

Statistical analysis

R software version 4.4.1 was used for data organization and statistical analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (length of hospitalization was expressed as median and interquartile range owing to its skewed distribution), and categorical variables were expressed as frequency (%). First, descriptive statistics were used to assess any difference in clinical characteristics of obstetric inpatients between training datasets and validation datasets using Chi-square tests. Second, univariable and multivariable stepwise logistic regression analyses were used to detect the influence factors of nosocomial infection in obstetric inpatients, Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated accordingly. Multivariable regression analysis was performed by using the method of “backward” stepwise search mode. The stepAIC algorithm was applied for model optimization. The variables that remained in the stepwise model were included in the final predictive model. Third, a nomogram was developed using the final prediction model. And receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was utilized to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) to assess the predictive accuracy of the nomogram in both the training and validation datasets. All P values were two-tailed. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of obstetric inpatients

Table 1 shows the chinical characteristics of obstetric inpatients for the training dataset and the validation dataset. Overall, the incidence rate of postpartum infection was 1.03% (296 out of 28608), with an average age of 31.12 ± 4.65 years, an average gestational age of 35.77 ± 6.62 weeks, and an average hospital stay of 3 (2, 4) days. Significant differences were observed between the training and validation datasets in terms of postpartum infection and various prenatal, labour, and postnatal characteristics, with the exceptions of age, ventilator use, and central venous catheter (CVC) use.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of obstetric inpatients

| Characteristics | Overall (N = 28608)1 |

Training dataset (N = 24455)1 |

Validation dataset (N = 4153)1 |

P 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum infection | 296 (1.03%) | 273 (1.12%) | 23 (0.55%) | < 0.001 |

| Prenatal characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) > = 35 | 6620 (23.14%) | 5629 (23.02%) | 991 (23.86%) | 0.233 |

| Gestational weeks < 37 | 2889 (10.10%) | 2627 (10.74%) | 262 (6.31%) | < 0.001 |

| Prenatal anemia | 2498 (8.73%) | 2015 (8.24%) | 483 (11.63%) | < 0.001 |

| Pregnancy with hypertension | 1334 (4.66%) | 1029 (4.21%) | 305 (7.34%) | < 0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 3870 (13.53%) | 3014 (12.32%) | 856 (20.61%) | < 0.001 |

| Prenatal hypoproteinemia | 131 (0.46%) | 99 (0.40%) | 32 (0.77%) | 0.001 |

| Oligohydramnios | 902 (3.15%) | 684 (2.80%) | 218 (5.25%) | < 0.001 |

| Labour characteristics | ||||

| PROM | 3402 (11.89%) | 2765 (11.31%) | 637 (15.34%) | < 0.001 |

| Cesarean Sction | 9225 (32.25%) | 7973 (32.60%) | 1252 (30.15%) | 0.002 |

| Operative delivery | 19,657 (68.71%) | 16,063 (65.68%) | 3594 (86.54%) | < 0.001 |

| Adverse birth outcomes | 1979 (6.92%) | 1461 (5.97%) | 518 (12.47%) | < 0.001 |

| Postnatal characteristics | 0.002 | |||

| Length of hospitalization (days) > 5 | 2954 (10.33%) | 2464 (10.08%) | 490 (11.80%) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator use | 39 (0.14%) | 35 (0.14%) | 4 (0.10%) | 0.450 |

| CVC use | 72 (0.25%) | 61 (0.25%) | 11 (0.26%) | 0.854 |

| Catheterization of ureter | 8721 (30.48%) | 7852 (32.11%) | 869 (20.92%) | < 0.001 |

1 n (%); 2 Pearson’s Chi-squared test; PROM: Premature rupture of membranes; CVC: Central venous catheter

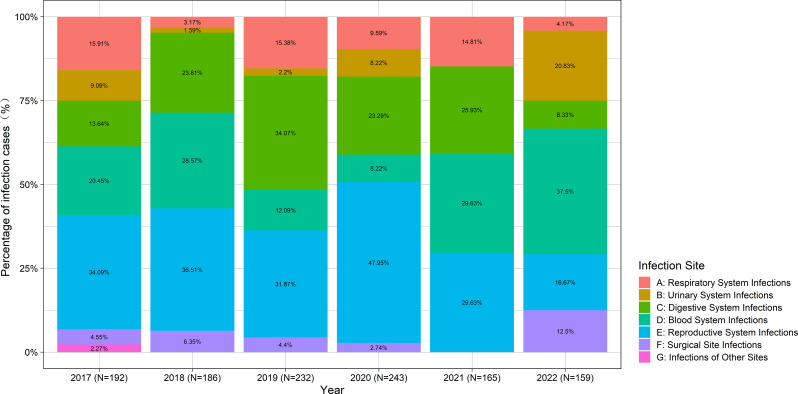

Figure 1 depicted the distribution of nosocomial infection sites in obstetric inpatients over the past years. Overall, the rate of postpartum infection cases was 1.60% (457 out of 28608), with reproductive system infections being the most common.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of nosocomial infection sites in obstetric inpatients over the past years

Factors affecting postpartum infections

Based on training dataset, the results of the univariate and multivariable logistic stepwise regression analyses of factors affecting postpartum infections are listed in Table 2. The univariate analysis showed that there were statistically significant differences between the infection group and the non-infection group regarding the gestational weeks, prenatal anemia, pregnancy with hypertension, prenatal hypoproteinemia, oligohydramnios, delivery mode, operative delivery, adverse birth outcomes, length of hospitalization (days), ventilator use, central venous catheter (CVC) use, and catheterization of ureter (P < 0.05). The findings from the multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis revealed that gestational weeks > = 37, prenatal anemia, prenatal hypoproteinemia, PROM, cesarean sction, operative delivery, adverse birth outcomes, length of hospitalization (days) > 5, CVC use and catheterization of ureter were retained in the final model and may serve as predictive factors for postpartum infections.

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable stepwise logistic regression analyses for postpartum infection

| Characteristic | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR1 | 95% CI1 | P | OR1 | 95% CI1 | P | |

| Age (years) > = 35 | 1.178 | 0.892, 1.538 | 0.238 | |||

| Gestational weeks < 37 | 1.927 | 1.403, 2.596 | < 0.001 | 1.499 | 1.076, 2.050 | 0.014 |

| Prenatal anemia | 3.064 | 2.265, 4.079 | < 0.001 | 1.686 | 1.217, 2.298 | 0.001 |

| Pregnancy with hypertension | 1.816 | 1.111, 2.799 | 0.011 | |||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 1.261 | 0.890, 1.740 | 0.174 | |||

| Prenatal hypoproteinemia | 16.679 | 9.149, 28.431 | < 0.001 | 4.042 | 2.052, 7.477 | < 0.001 |

| Oligohydramnios | 2.043 | 1.156, 3.337 | 0.008 | |||

| PROM | 1.080 | 0.735, 1.533 | 0.682 | 1.372 | 0.923, 1.978 | 0.103 |

| Cesarean Sction | 5.369 | 4.139, 7.037 | < 0.001 | 2.116 | 1.418, 3.200 | < 0.001 |

| Operative delivery | 5.490 | 3.689, 8.574 | < 0.001 | 1.789 | 1.110, 2.973 | 0.020 |

| Adverse birth outcomes | 2.347 | 1.613, 3.312 | < 0.001 | 3.123 | 2.054, 4.641 | < 0.001 |

| Length of hospitalization (days) > 5 | 5.782 | 4.503, 7.391 | < 0.001 | 3.297 | 2.534, 4.269 | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator use | 18.716 | 6.968, 42.440 | < 0.001 | |||

| CVC use | 17.991 | 8.528, 34.311 | < 0.001 | 3.725 | 1.586, 8.004 | 0.001 |

| Catheterization of ureter | 6.649 | 5.071, 8.832 | < 0.001 | 2.625 | 1.769, 3.937 | < 0.001 |

1 OR = odd ratio; CI = confidence interval; 2 Multivariable regression analysis was performed by using the method of “backward” stepwise search mode.; PROM: Premature rupture of membranes; CVC: Central venous catheter

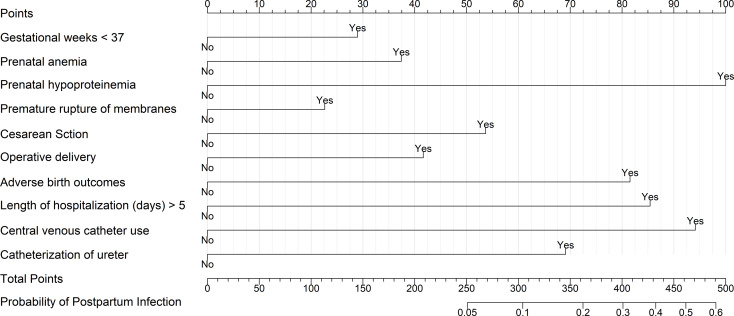

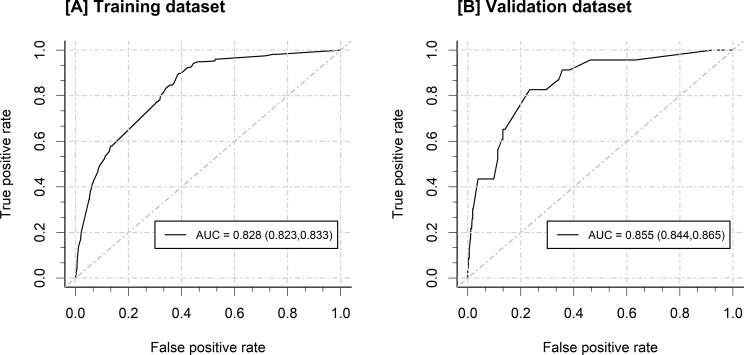

Nomogram and independent validation

Based on the results of the multivariable logistic stepwise regression analysis, a nomogram was constructed for a graphical representation of the predictive model. See Fig. 2 for details. The nomogram to estimate risk probabilities of nosocomial infections among obstetric inpatients was built using the training dataset (24455 inpatients) and validated on the independent validation dataset (4153 inpatients). The AUC of the nomogram in the training dataset was 0.828 (0.823, 0.833), and in the validation dataset, it was 0.855 (0.844, 0.865). See Fig. 3 for details, indicating that the nomogram has a good predictive capability.

Fig. 2.

Nomogram for postpartum infections Risk. Nomogram depicting the estimation of postpartum infections risk in obstetric inpatients. Based on the 10 variables in the nomogram, the individual clinical characteristics of the obstetric inpatient are inputted and the total score of the patient is calculated. Each total score corresponds to a probability of postpartum infections risk

Fig. 3.

The ROC curve of the nomogram. A, in the training dataset; B, in the validation dataset

Discussion

The goal of this study was to develop and validate an individual postpartum infections risk nomogram for obstetric inpatients. The gestational weeks > = 37, prenatal anemia, prenatal hypoproteinemia, PROM, cesarean sction, operative delivery, adverse birth outcomes, length of hospitalization (days) > 5, CVC use and catheterization of ureter were included in the prediction model. The multivariable logistic regression model had the best fit on the training dataset (24455 inpatients) and the validation dataset (4153 inpatients).

We observed substantial variations in nosocomial infection rates and clinical characteristics among obstetric inpatients across different years. These discrepancies may be attributable to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of associated prevention and control measures [19, 20]. Obstetric inpatients are at an increased risk of adverse birth outcomes during the COVID-19 outbreak [21]. Nevertheless, this imbalance would indeed enhance the model’s extrapolative efficacy, thereby rendering it a more robust tool for evaluation.

The incidence of nosocomial infections in obstetrics departments in China ranges between 0.1% and 4.46% [7, 8]. Based on large sample data from China, current research further confirms that the hospital infection rate among obstetric inpatients is at a relatively high level. Specifically, the incidence rate of postpartum infections was found to be 1.03%, while the prevalence of cases of postpartum infection was recorded at 1.60%. Such infections can pose a serious threat to the life safety of pregnant women and adversely affect the health level of newborns [22]. The infections primarily occurred in the reproductive tract, which is related to the changes in the reproductive system of pregnant women during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period [23]. Invasive procedures during childbirth, such as vaginal examination, artificial rupture of membranes, manual placental removal, episiotomy, and cesarean section, directly affect the female reproductive system, thus increasing the risk of infection. Additionally, childbirth consumes a large amount of physical energy, which lowers the body’s resistance and creates optimal conditions for infections of the reproductive system [24]. Reducing the rate of nosocomial infections in obstetrics is an important issue we currently face.

Former studies have reported on the risk factors for hospital infections among obstetric patients [9–14]. The logistic analysis of this study indicates that: (1) Invasive operations, such as cesarean section, CVC use and catheterization of ureter, significantly increase the risk of postpartum infections. Postpartum maternal infection is most frequently caused by cesarean delivery [25]. This could be due in part to the reduction in immune function following a period of fasting after cesarean delivery; additionally, the trauma from cesarean section is greater, and the associated postoperative pain may lead to reduced or no movement in pregnant women, making it difficult for lochia to be expelled and thus increasing the chance of reproductive system infections [26]. Therefore, medical staff should strictly adhere to the indications for cesarean section, provide proper prenatal healthcare education, encourage natural childbirth, and reduce the rate of emergency cesarean sections. In cases where cesarean section is necessary, it should be performed according to sterile surgical techniques to minimize hospital infections. Postoperative cesarean patients often require urinary catheters, and these invasive procedures can easily damage the urethral mucosa. It is estimated that over 60% of urinary tract infections are due to improper catheter use, and the longer the catheter is left in place, the higher the risk of infection [27, 28]. (2) The presence of underlying diseases before childbirth, such as prenatal anemia and hypoalbuminemia, can lead to a decrease in the immune and resistance capacities of pregnant women, making them more susceptible to hospital infections. This study found that prenatal anemia increased the risk of infection by 1.686 times (95% CI: 1.217–2.298) compared to non-anemic women. This may be related to the fact that postpartum bleeding exacerbates anemia and reduces resistance in mothers. On the other hand, following postpartum hemorrhage, bacteria can enter the body through the bloodstream, leading to severe complications such as uterine infection or sepsis [29]. The occurrence of prenatal hypoalbuminemia is 4.042 times more likely than those without hypoalbuminemia (95% CI: 2.052–7.477), suggesting that low serum albumin during pregnancy, due to inadequate protein intake or poor absorption, can lead to decreased immunity. Therefore, during prenatal examinations, medical personnel should assist pregnant women in actively improving their nutritional status during pregnancy to enhance their immunity. (3) The conditions of delivery influence the occurrence of hospital infections. This study found that gestational age < 37 weeks, hospital stay > 5 days, and adverse birth outcomes increase the chance of hospital infections (OR > 1, P < 0.05). Other studies have similarly indicated that the probability of intrauterine infection and neonatal death increased with the increase of less than 37 weeks of pregnancy, that is, premature delivery; furthermore, the risk of cross-infection increases with the length of hospital stay [30–32].

There are notable disparities in the incidence of nosocomial infections among obstetric inpatients across various hospitals, which may be closely associated with the quality of medical care and the availability of medical resources. Consequently, the nomogram developed in our study serves as a valuable tool for obstetricians to early identify high-risk obstetric inpatients susceptible to postpartum infections, thereby enhancing clinical decision-making and alleviating the burden of disease. Based on the nomogram prediction of postpartum infection risk, clinicians can more effectively elucidate the underlying factors and potential outcomes associated with a high risk of infection to patients. Furthermore, individualized postoperative preventive strategies can be formulated, including the enhanced administration of antibiotics, meticulous postoperative care, and intensify postoperative monitoring to ensure the timely detection and management of infections.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to provide a nomogram to enable personalized postpartum infections risk estimates for obstetric inpatients based on a large-scale retrospective study conducted in China. Nevertheless, some limitations in the current study should be acknowledged. Firstly, the subjects included in this study were all sourced from a single hospital, thereby constraining the generalizability of the research findings. Future studies should incorporate data from multiple external hospitals to enhance the validity of the results presented in this column chart. Secondly, this study aims to investigate the factors associated with postpartum infection across the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum phases. Future research should consider focusing exclusively on preoperative indicators to predict the likelihood of postpartum infection, with the objective of developing earlier preventive measures.

Conclusions

Through a large-scale retrospective study conducted in China, we developed and independently validated a nomogram to enable personalized postpartum infections risk estimates for obstetric inpatients. This tool provides an individualized estimate of postpartum infections risk, rather than a group estimate based on specific patient-level characteristics, and should be useful to obstetricians for predicting postpartum infection risk of obstetric inpatients in real time, and help to develop individualized postoperative preventive strategies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

- PROM

Premature rupture of membranes

- CVC

Central venous catheter

- ORs

Odds ratios

- CIs

Confidence intervals

Author contributions

L.H., H.C., and Z.R. contributed to the conception and design of the study. L.H. and J.W. were responsible for data collection and management. J.W. conducted the data analysis and statistical modeling. H.H. and J.R. provided critical revisions and guidance on the methodology. L.H. and H.C. drafted the initial manuscript. J.W. was responsible for the comprehensive revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Foundation of Xiamen Medical Healthcare Guidance Program (grant number: 3502Z20224ZD1010) to Huiping Huang.

Data availability

The data supporting the study results may be accessed via the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors state that the study has passed the ethical review of IRB, the First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University. Study participants were informed of the purpose and procedures of the study and their informed consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lei Huang, Jielong Wu and Houzhi Chen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Chan MY, Smith MA. 5.16 - Infections in Pregnancy☆. In: Comprehensive Toxicology (Third Edition). edn. Edited by McQueen CA. Oxford: Elsevier; 2018: 232–249.

- 2.Goff SL, Pekow PS, Avrunin J, Lagu T, Markenson G, Lindenauer PK. Patterns of obstetric infection rates in a large sample of US hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013, 208(6):456 e451-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Group WHOGMSSR. Frequency and management of maternal infection in health facilities in 52 countries (GLOSS): a 1-week inception cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(5):e661–71. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30109-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrzan-Detkos M, Walczak-Kozlowska T, Lipowska M. The need for additional mental health support for women in the postpartum period in the times of epidemic crisis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):114. 10.1186/s12884-021-03544-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kollef MH, Torres A, Shorr AF, Martin-Loeches I, Micek ST. Nosocomial infection. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(2):169–87. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodd SL, Montoya A, Barreix M, Pi L, Calvert C, Rehman AM, Chou D, Campbell OMR. Incidence of maternal peripartum infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(12):e1002984. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan H, Zhang C, Maung ENT, Fan S, Shi Z, Liao F, Wang S, Jin Y, Chen L, Wang L. Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors of obstetric infection after the Universal two-child policy in North China: a 5-year retrospective study based on 268,311 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):878. 10.1186/s12879-022-07714-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu CZ, Cai B, Chen CL, Liu S. Analysis on the current situation of nosocomial infection and its influencing factors of hospitalized parturient in obstetrics department of class general hospitals. Intern Med. 2022;17(02):210–2. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelrahman MA, Zaki A, Salem SAM, Salem HF, Ibrahim ARN, Hassan A, Elgendy MO. The impact of Cefepime and Ampicillin/Sulbactam on preventing Post-cesarean Surgical Site infections, Randomized Controlled Trail. Antibiot (Basel) 2023, 12(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Boggess KA, Tita A, Jauk V, Saade G, Longo S, Clark EAS, Esplin S, Cleary K, Wapner R, Letson K, et al. Risk factors for Postcesarean Maternal Infection in a trial of extended-Spectrum Antibiotic Prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):481–5. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Classen DC, Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Horn SD, Menlove RL, Burke JP. The timing of prophylactic administration of antibiotics and the risk of surgical-wound infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(5):281–6. 10.1056/NEJM199201303260501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leth RA, Moller JK, Thomsen RW, Uldbjerg N, Norgaard M. Risk of selected postpartum infections after cesarean section compared with vaginal birth: a five-year cohort study of 32,468 women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(9):976–83. 10.1080/00016340903147405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pathak A, Mahadik K, Swami MB, Roy PK, Sharma M, Mahadik VK, Lundborg CS. Incidence and risk factors for surgical site infections in obstetric and gynecological surgeries from a teaching hospital in rural India. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:66. 10.1186/s13756-017-0223-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song H, Hu K, Du X, Zhang J, Zhao S. Risk factors, changes in serum inflammatory factors, and clinical prevention and control measures for puerperal infection. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(3):e23047. 10.1002/jcla.23047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kattan MW. Nomograms. Introduction. Semin Urol Oncol. 2002;20(2):79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang J, Wu J, Hong G, Zheng L, Yu L, Liu X, Lin P, Yu Z, Chen D, Lin Q, et al. Cancer screening in hospitalized ischemic stroke patients: a multicenter study focused on multiparametric analysis to improve management of occult cancers. EPMA J. 2024;15(1):53–66. 10.1007/s13167-024-00354-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.China NHCotPsRo. Standard for healthcare associated infection surveillance WS/T 312–2023. Electron J Emerg Infect. 2024;9(02):84–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pate A, Riley RD, Collins GS, van Smeden M, Van Calster B, Ensor J, Martin GP. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model using multinomial logistic regression. Stat Methods Med Res. 2023;32(3):555–71. 10.1177/09622802231151220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Toro F, Gjoka M, Di Lorenzo G, De Santo D, De Seta F, Maso G, Risso FM, Romano F, Wiesenfeld U, Levi-D’Ancona R, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(1):36–46. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamieson DJ, Rasmussen SA. An update on COVID-19 and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2):177–86. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei SQ, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Liu S, Auger N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2021;193(16):E540–8. 10.1503/cmaj.202604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahnfeldt-Mollerup P, Petersen LK, Kragstrup J, Christensen RD, Sorensen B. Postpartum infections: occurrence, healthcare contacts and association with breastfeeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(12):1440–4. 10.1111/aogs.12008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark AR, Kruger JA. Mathematical modeling of the female reproductive system: from oocyte to delivery. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 2017, 9(1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sebeta A, Girma A, Kidane R, Tekalign E, Tamiru D. Nutritional status of Postpartum Mothers and Associated Risk factors in Shey-Bench District, Bench-Sheko Zone, Southwest Ethiopia: A Community based cross-sectional study. Nutr Metab Insights. 2022;15:11786388221088243. 10.1177/11786388221088243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbs RS. Clinical risk factors for puerperal infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55(5 Suppl):S178–84. 10.1097/00006250-198003001-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giouleka S, Tsakiridis I, Kostakis N, Boureka E, Mamopoulos A, Kalogiannidis I, Athanasiadis A, Dagklis T. Postnatal care: a comparative review of guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2024;79(2):105–21. 10.1097/OGX.0000000000001224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shuman EK, Chenoweth CE. Urinary catheter-Associated infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32(4):885–97. 10.1016/j.idc.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakawuki AW, Nekaka R, Ssenyonga LVN, Masifa G, Nuwasiima D, Nteziyaremye J, Iramiot JS. Bacterial colonization, species diversity and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of indwelling urinary catheters from postpartum mothers attending a Tertiary Hospital in Eastern Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0262414. 10.1371/journal.pone.0262414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo YN, Ma J, Wang XJ, Wang BS. Does uterine gauze packing increase the risk of puerperal morbidity in the management of postpartum hemorrhage during caesarean section: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(8):13740–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humberg A, Fortmann I, Siller B, Kopp MV, Herting E, Gopel W, Hartel C. German neonatal network GCfLR, priming immunity at the beginning of life C: Preterm birth and sustained inflammation: consequences for the neonate. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(4):451–68. 10.1007/s00281-020-00803-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner L, Diesner SC, Voitl P. Risk of infection in the first year of life in preterm children: an Austrian observational study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0224766. 10.1371/journal.pone.0224766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz D, Bateman BT, Kjaer K, Turner DP, Spence NZ, Habib AS, George RB, Toledano RD, Grant G, Madden HE, et al. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Coronavirus Disease 2019 Registry: an analysis of outcomes among pregnant women delivering during the initial severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 outbreak in the United States. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(2):462–73. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the study results may be accessed via the corresponding author upon reasonable request.