Abstract

Background:

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) such as preeclampsia and gestational hypertension are major contributors to maternal and child morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have reported associations with selected metals and vitamins but are limited in sample size and non-prospective study designs. We evaluated prospective associations of metal mixtures with HDP and tested interactions by vitamins.

Study Design:

We measured first trimester (median = 10.1 weeks) concentrations of essential (copper, magnesium, manganese, selenium, zinc) and nonessential (arsenic, barium, cadmium, cesium, mercury, lead) metals in red blood cells (n = 1,386) and vitamins (B12 and folate) in plasma (n = 924) in Project Viva, a pre-birth US cohort. We collected diagnosis of HDP by reviewing medical records. We used multinomial logistic regression and Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression to estimate individual and joint associations of metals with HDP and interactions by vitamins, after adjusting for key covariates.

Results:

The majority of participants were non-Hispanic white (72.5 %), never smokers (68.5 %) with a mean (SD) age of 32.3 (4.6) years. Fifty-two (3.8 %) developed preeclampsia and 94 (6.8 %) gestational hypertension. A doubling in first trimester erythrocyte copper was associated with 78 % lower odds of preeclampsia (OR=0.22, 95 % confidence interval: 0.08, 0.60). We also observed significant associations between higher erythrocyte total arsenic and lower odds of preeclampsia (OR=0.80, 95 % CI: 0.66, 0.97) and higher vitamin B12 and increased odds of gestational hypertension (OR=1.79, 95 % CI: 1.09, 2.96), but associations were attenuated after adjustment for dietary factors. Lower levels of the overall metal mixture and essential metal mixture were associated with higher odds of preeclampsia. We found no evidence of interactions by prenatal vitamins or between metals.

Conclusion:

Lower levels of a first-trimester essential metal mixture were associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia, primarily driven by copper. No associations were observed between other metals and HDP after adjustment for confounders and diet.

Keywords: Metals, Prenatal environmental exposures, Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, Preeclampsia, Gestational hypertension

1. Introduction

Preeclampsia and gestational hypertension are common hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) and leading causes of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality (Lo et al., 2013; Backes et al., 2011; Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia, 2020). In the United States, these conditions affect approximately 13 % of pregnancies, and their incidence has been on the rise in recent decades (Ford, et al., 2022; Bello et al., 2021). Despite well-documented risk factors, including primiparity, maternal age, and race/ethnicity, the precise pathophysiological mechanisms of HDP remain unknown, hindering the development of effective prevention strategies (Chappell et al., 2021). However, numerous etiological theories have been proposed (Luo et al., 2007; Lain and Roberts, 2002; Jung et al., 2022). One of the most prominent theories links preeclampsia development to uteroplacental ischemia and poor placentation, originating from the ineffective establishment of maternal circulation during early placental development (Raijmakers et al., 2004; Pijnenborg et al., 1991; Parker and Werler, 2014; Granger et al., 2001). There is a growing interest in understanding whether modifiable exposure to environmental factors, such as nonessential and essential metal exposures, can impact healthy placentation and play a role in the development of HDP (Borghese et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2023).

Exposure to nonessential, heavy metals is ubiquitous and primarily originates from anthropogenic sources, while essential metals are commonly obtained through diet, water, and supplementation (Tchounwou et al., 2012; Council, 1989). Some nonessential metals, such as cadmium, can accumulate in the placenta and alter biological functioning (Barr et al., 2007), while others may generate reactive oxygen species which induce lipid peroxidation, protein modification, and DNA damage (Wu et al., 2016). In contrast, essential metals or elements may act as antioxidants and play a vital role in biochemical and physiological processes, including placental development (Negi et al., 2012). Recent evidence suggests higher exposure to various non-essential metals during pregnancy, including lead, cadmium, arsenic, and methylmercury, may be associated with higher risk of developing HDP (Borghese et al., 2023; Kahn and Trasande, 2018; Poropat et al., 2018), whereas essential metals, such as manganese and zinc, have been associated with lower risk (Liu et al., 2020; Negi et al., 2012; Rumiris et al., 2006).

Lower concentrations of prenatal vitamins (B12 and folate) in blood have generally been associated with increased risk of HDP (Mardali et al., 2021; Furness et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2021). Vitamin B12 and folate are methyl donors which play a critical role in a variety of biochemical reactions with amino acids, homocysteine, cysteine, and methionine (O’Leary and Vitamin, 2010; Menezo et al., 2022; Majumdar et al., 2012). Insufficient levels of vitamin B12 and folate can disrupt homocysteine conversion, resulting in elevated homocysteine concentrations which have been linked to oxidative stress, endothelial damage, and preeclampsia (Mardali et al., 2021; Cotter et al., 2003). Higher exposure to nonessential metals can also increase homocysteine levels via disruption of essential enzymes in the metabolism of homocysteine (Ledda et al., 2019). Given their shared homocysteine pathways, vitamins can potentially counteract or mitigate the adverse effects of metals on health outcomes (Lee et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2019). Previous studies have found evidence of effect modification between metals and folate on childhood obesity and increased arsenic execretion from folic acid supplementation (Wang et al., 2019; Bozack et al., 2019; Abuawad et al., 2023), but no existing studies have explored vitamin B12 and folate as potential effect modifiers of prenatal metal exposures with HDP. Additionally, associations of metals with HDP have been inconsistent across previous studies, limited in sample size, and of non-prospective designs. Furthermore, of the limited prospective studies available, only a few have investigated the joint impacts of essential and nonessential metals on HDP (Borghese et al., 2023; Bommarito et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020), which is more reflective of real-world exposures and therefore important to characterize in association to HDP.

In this study, we evaluated prospective associations of early pregnancy essential and nonessential metals, individually and jointly, with odds of HDP. As a secondary aim, we tested interactions by prenatal vitamins (B12 and folate), given previous evidence of their protective effects against nonessential metals. Based on previous literature (Borghese et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020), we hypothesized that essential metals would be associated with decreased odds of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, while nonessential metals would be associated with increased odds.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

We analyzed a subset of pregnant persons participating in Project Viva, a prospective pregnancy cohort study. A detailed description of the Project Viva study population and protocol have been previously described (Oken et al., 2015; Rifas-Shiman et al., 2023). In brief, participants were initially recruited from 1999 to 2002 during their first prenatal visit at a multispecialty practice located in eastern Massachusetts. Eligible participants at the time of recruitment were: 1) able to participate in English, 2) < 22 weeks’ gestation, 3) had a singleton pregnancy, and 4) planned to remain in the study area throughout pregnancy.

Of the 2,128 eligible live births in Project Viva (Figure S1), we included in the current analysis the 1,386 participants with available first trimester metal concentrations and HDP status. We only included participants first Project Viva pregnancy (n = 28 births excluded) and excluded participants without available first trimester metal concentrations (n = 693) and HDP status (n = 21). In subsequent analyses evaluating joint exposures of metals, we excluded participants missing mercury concentrations (n = 17) from our analysis due to insufficient biospecimens available for mercury analysis. For our secondary aim evaluating interaction by vitamins, we analyzed only participants with available information on prenatal vitamins, metals, and HDP status (n = 924). Relative to participants excluded from the analytical sample (Table S1), participants included in the analytical sample were older, more likely to be non-Hispanic White, and had a higher education and income level.

Written informed consent was provided by participants at study entry and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute.

2.2. Maternal first-trimester metal concentrations

Blood samples were collected at study enrollment (mean = 10.1 weeks gestation) from all participants, centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to separate erythrocytes from plasma, and stored at −70 °C.

A detailed description of the laboratory methods used for the analysis of all metals has been previously described elsewhere (Smith et al., 2021; P-iD et al., 2021). Briefly, all metal concentrations, except mercury, were measured using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; Agilent 8800 ICP-QQQ). Samples of stored packed erythrocytes (0.5 mL) were weighed and digested for 48 h in 2 mL of ultra-pure concentrated HNO3 acid, diluted in 10 mL of deionized water, and further digested with 1 ml of 30 % ultra-pure HNO3. Elements were analyzed in a single run using triple quadruple Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (Agilent 8800 ICP-QQQ) in MS/MS mode with appropriate cell gasses and internal standards. Mercury was quantified separately using the Direct Mercury Analyzer 80 (Milestone, Inc.). Validity of concentration estimates was assessed using three quality control methods, including procedural blanks, initial and continuous calibration verification, and blinded technical replicates in 2 % (n = 52) of samples. Intra-day coefficients of variation (CVs) were < 5 % for all analytes, apart from selenium (<10 %), and were assessed using in-house quality control pools at three distinct concentrations, tested before and after every tenth sample (N=7). Inter-day CVs were < 15 % for all metals, except for values near the limit of detection (LOD).

Consistent with previous studies (P-iD et al., 2021; Thilakaratne et al., 2023), we selected metals for analyses in this study if they had: 1) a detection frequency ≥ 90 % across samples, and 2) an interclass correlation ≥ 0.5 among duplicates. Of the 20 metals originally quantified, this criterion was met among 5 essential metals (copper (Cu), magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn), selenium (Se), zinc (Zn)), 5 nonessential metals (barium (Ba), cadmium (Cd), cesium (Cs), mercury (Hg), and lead (Pb)), and 1 nonessential metalloid (arsenic (As)), hereby referred to as a metal. We excluded 6 metals (aluminum, cobalt, molybdenum, antimony, tin, and thallium) with a detection frequency < 90 % and 3 metals (chromium, nickel, and vanadium) with interclass correlations < 0.5 from our analyses. The LOD for selected metals ranged from 0.06 to 8.74 ng/g. Samples with metal concentrations below the LOD were imputed using the LOD √2.

2.3. Maternal first trimester vitamin concentrations

Concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate were measured in the plasma of the same first-trimester blood samples used to measure metals. As previously described (Thilakaratne et al., 2023), we measured vitamin B12 using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Elecsys Vitamin B12 II; Roche Diagnostic) and folate using electrochemiluminescence binding assay (Elecsys Folate III; Roche Diagnostic) and both assays were conducted on the Roche Cobas 6000 system (Roche Diagnostics). Day-to-day imprecision values for the Vitamin B12 assay were 7.6 %, 4.4 %, and 3.2 % for concentrations of 203 pg/mL, 481 pg/mL, and 1499 pg/mL, respectively. For the folate assay, day-to-day imprecision values were 3.9 %, 3.1 %, and 2.0 % for concentrations of 7.6 ng/mL, 14.3 ng/mL, and 19.2 ng/mL, respectively. Vitamin concentrations below the LOD were imputed by the LOD/√2. Plasma samples with vitamin B12 concentrations above the upper limit of the assay (4,000 pg/mL) were imputed to 4,000 pg/mL. Some plasma samples were affected by hemolysis (erythrocyte destruction) and/or lipemia (accumulation of lipoproteins that causes turbidity) which may affect measurements of vitamin B12 and folate concentrations. As a result, subsequent sensitivity analyses were performed additionally adjusting for presence of hemolysis and/or lipemia in samples to evaluate the robustness of our results.

2.4. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

We used abstracted clinical data on blood pressure, urine protein, and diagnostic and discharge codes related to gestational hypertension or preeclampsia to ascertain HDP, as previously described (Oken et al., 2007). We classified participants as having chronic hypertension if they reported a diagnosis prior to pregnancy or were taking antihypertensive medication or if they had two or more elevated blood pressure measures (≥140 mmHg SBP or ≥ 90 mmHg DBP) prior to 20 weeks of gestation. We defined gestational hypertension and preeclampsia according to the National High Blood Pressure Education Program’s recommendations during the study’s recruitment period (2000) (Oken et al., 2007). Specifically, we classified participants with two or more elevated blood pressure measures (≥140 mmHg SBP or ≥ 90 mmHg DBP) after 20 weeks’ gestation as having gestational hypertension and those who also had proteinuria (urine dipstick values of 1 + on two or more occasions > 4 h but < 7 days apart; or urine dipstick values of ≥ 2 + on one or more occasions) or had chronic hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks’ gestation as having preeclampsia.

2.5. Covariates

We identified study covariates a priori based on subject matter knowledge, previous literature on metals and HDP, and visualized using directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) created on DAGitty (Figure S2) (Textor et al., 2016). We evaluated race and ethnicity as a potential covariate since it may be a proxy for unmeasured variables stemming from structural racism, such social marginalization and discrimination (Kaplan and Bennett, 2003). All models were adjusted for selected covariates, including participant age at enrollment (continuous), pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2, continuous), self-reported race and ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Hispanic, more than one race or ethnicity), education (less than college graduate, college graduate), household annual income (≤USD$70,000, > USD$70,000), smoking status (never, former, during pregnancy), and parity (nulliparous, greater than one). Participant sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics were collected via in-person interviews and questionnaires administered during study visits and from medical records. Pre-pregnancy BMI was calculated using self-reported weight and height. Among participants with available exposure and outcome information in primary analysis, there was no missing covariate information.

2.6. Statistical analysis

We examined descriptive statistics for participant demographic characteristics, metal concentrations, and outcome measures. We also examined associations between metal concentrations and vitamins prior to log2-transforming concentrations using Spearman correlation coefficients. Since metal concentrations were right-skewed, we log2-transformed both metals and vitamins for statistical modeling. We used multivariable multinomial logistic regression models to evaluate independent associations of prenatal metals and vitamins with a four level HDP variable (normotensive, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia), adjusting for the previously mentioned covariates. Statistical interactions between each metal and vitamin were evaluated within independent models using a multiplicative term and identified using likelihood ratio tests, with an α < 0.05 defined as a statistically significant interaction.

We used the probit extension of Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression (BKMR) to evaluate joint associations of prenatal metals and vitamins with probability of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension. BKMR is a flexible and semi-parametric method which uses a Gaussian kernel function to flexibly estimate the effects of an exposure mixture on a health outcome of interest (Bobb et al., 2015; Bobb et al., 2018). BKMR is additionally unique in its ability to evaluate potential synergistic and antagonistic relationships between exposures (Bobb et al., 2015). For BKMR, we modeled the joint effects of all metals on dichotomous outcomes of HDP (preeclampsia vs no HDP; gestational hypertension vs no HDP), evaluating only hypertensive disorders with onset in pregnancy (gestational hypertension and preeclampsia) and placing all other participants into the non-HDP group, including participants with chronic hypertension who did not develop preeclampsia. We used hierarchical variable selection to group metals by essential vs nonessential status and Gaussian predictive process set at 100 knots. We then evaluated: 1) the overall effect of concurrently increasing percentiles of all metals in the mixture on odds of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, relative to fixing all metals at their median, and 2) the univariate associations between each metal and odds of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, while holding all other metals at their median. We also modeled essential (copper, magnesium, manganese, selenium, zinc) and non-essential (arsenic, barium, cadmium, cesium, mercury, lead) metals independently in BKMR models, while adjusting for the other metals, using component-wise variable selection to estimate their independent effects on BKMR results.

To evaluate possible interactions between metals and vitamins (B12 and folate), we additionally ran regression models including the two vitamins in the exposure mixture and used hierarchical variable selection to define separate groups (essential/nonessential metals, and vitamins). We then visually inspected possible pairwise interactions between prenatal metals and vitamins when varying a second metal/vitamin to its 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile, relative to holding other metals/vitamins to their median. Interactive effects were further assessed by evaluating the single-exposure health effect associated with a change in metals/vitamins from their 25th to 75th percentile, when holding other exposures at their 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile, and we calculated the difference in effect when all remaining exposures were fixed at their 25th percentile versus 75th percentile. We again estimated the associations modeling the essential and non-essential metals independently in BKMR models using component-wise variable selection, with vitamins included in the exposure mixture of each independent model.

All metals and vitamins were log2-transformed, mean-centered, and standard deviation scaled prior to BKMR modeling, while all continuous covariates were mean centered and scaled to one standard deviation. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampler was used to obtain 50,000 posterior samples of model parameters, with the first half of iterations used as burn-in and chains thinned to every 10th iteration. We visually assessed and confirmed model convergence using trace plots.

All statistical analysis were performed on R (R v.4.3) and the “bkmr” package was used for all BKMR analysis.

2.7. Sensitivity analysis

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our results. All primary models were refit additionally adjusting for factors which may impact erythrocyte metal or vitamin concentrations, including hematocrit and hemolysis and/or lipemia. Additionally, we ran sensitivity analyses further adjusting for dietary variables which were identified as potential confounders and may also be important sources of exposure, including daily fish intake and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern measured using the first trimester semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). We also performed sensitivity analyses evaluating independent associations between metals and HDP among never smokers only, given previous evidence of smoking status as a potential effect modifier between metals and blood pressure (Zhang et al., 2021). Since race and ethnicity is a social construct (Mersha and Beck, 2020), we also refit all primary models excluding covariate adjustment for self-reported race and ethnicity. In order to further complement our findings and to evaluate potential non-linear associations, we also used generalized additive models (GAMs) with a smoothing term to evaluate associations between log2-transformed copper and odds of preeclampsia, using the “mgcv” package.

As an alternative assessment of our outcome, we also performed sensitivity analyses using continuous trimester specific mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values calculated using all available medically abstracted second and third trimester blood pressure values. As previously mentioned, we also performed additional models excluding participants with chronic hypertension who did not develop preeclampsia from the reference group (n = 22) and sensitivity analysis evaluating the joint associations of prenatal metals and vitamins with probability of chronic hypertension. Since BKMR is sensitive to extreme values, we also performed sensitivity analyses excluding participants who had any values > 3 times the IQR of log2-transformed metals (n = 19), as defined by Tukey’s fences for outlier definition.

We further assessed the robustness of our BKMR results using multinomial quantile g-computation models (Keil et al., 2020). Quantile g-computation is a parametric and generalized linear model based approach of g-computation which is used to estimate the overall effect of an exposure mixture on an outcome of interest and provides estimates of individual weights that represent their contributions to the overall mixture. Log2-transformed metal exposures were categorized into quartiles during model implementation and the “qgcomp” package was used for all quantile g-computation models. In our analyses, models represent the odds of HDP for a one quartile increase in the metal mixture, conditional on key covariates. Similar to our approach in the BKMR analysis, we also performed additional models with only essential or nonessential metals included in the metal mixture.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

Table 1 presents participant’s characteristics at study entry in the full analytical sample and by HDP status. Overall, participants were a mean (SD) age of 32.3 (SD: 4.63) and primarily non-Hispanic White (72.5 %), college graduates (69.3 %), with an annual household income greater than $70,000 USD (60.3 %). Based on study criteria, 94 (6.8 %) participants were categorized as having gestational hypertension and 52 (3.8 %) developed preeclampsia. When compared to normotensive participants, participants with preeclampsia were more likely to be nulliparous (75.0 % vs. 46.1 %), non-Hispanic Black (32.7 % vs. 12.2 %), and smokers during pregnancy (19.2 % vs. 11.9 %). Participants with preeclampsia were also more likely to report lower average first trimester fish consumption (1.43 vs. 1.65 servings/week) and lower intake of DASH diet items (22.9 vs 24.2), relative to the full analytical sample (Table S2).

Table 1.

Overall study characteristics for 1,386 Project Viva participants included in the study and by hypertensive disorders of pregnancy status.

| Overall (N=1386) Mean ± SD/N(%) | Normotensive (N=1218) Mean ± SD/N(%) | Chronic Hypertension (N=22) Mean ± SD/N(%) | Gestational Hypertension (N=94) Mean ± SD/N(%) | Pre-Eclampsia (N=52) Mean ± SD/N(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age at enrollment (years) | 32.3 ± 4.63 | 32.3 ± 4.60 | 34.0 ± 4.46 | 32.0 ± 4.35 | 31.4 ± 5.62 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 25.0 ± 5.52 | 24.7 ± 5.35 | 28.9 ± 7.23 | 25.8 ± 5.17 | 29.0 ± 6.98 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| NH White | 1005 (72.5) | 885 (72.7) | 13 (59.1) | 78 (83.0) | 29 (55.8) |

| NH Asian | 64 (4.6) | 59 (4.8) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.9) |

| NH Black | 178 (12.8) | 148 (12.2) | 4 (18.2) | 9 (9.6) | 17 (32.7) |

| Hispanic | 94 (6.8) | 84 (6.9) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (5.3) | 4 (7.7) |

| More than one race or ethnicity | 45 (3.2) | 42 (3.4) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.9) |

| Education | |||||

| <College graduate | 426 (30.7) | 382 (31.4) | 4 (18.2) | 17 (18.1) | 23 (44.2) |

| College graduate | 960 (69.3) | 836 (68.6) | 18 (81.8) | 77 (81.9) | 29 (55.8) |

| Annual household income | |||||

| ≤USD $70,000 | 550 (39.7) | 493 (40.5) | 4 (18.2) | 30 (31.9) | 23 (44.2) |

| >USD $70,000 | 836 (60.3) | 725 (59.5) | 18 (81.8) | 64 (68.1) | 29 (55.8) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never smoked | 949 (68.5) | 839 (68.9) | 16 (72.7) | 59 (62.8) | 35 (67.3) |

| Former smoker | 265 (19.1) | 234 (19.2) | 4 (18.2) | 20 (21.3) | 7 (13.5) |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 172 (12.4) | 145 (11.9) | 2 (9.1) | 15 (16.0) | 10 (19.2) |

| Nulliparous | 673 (48.6) | 561 (46.1) | 12 (54.5) | 61 (64.9) | 39 (75.0) |

Note: BMI, Body mass index; NH, Non-Hispanic; SD, Standard deviation.

3.2. Exposure and outcome distributions

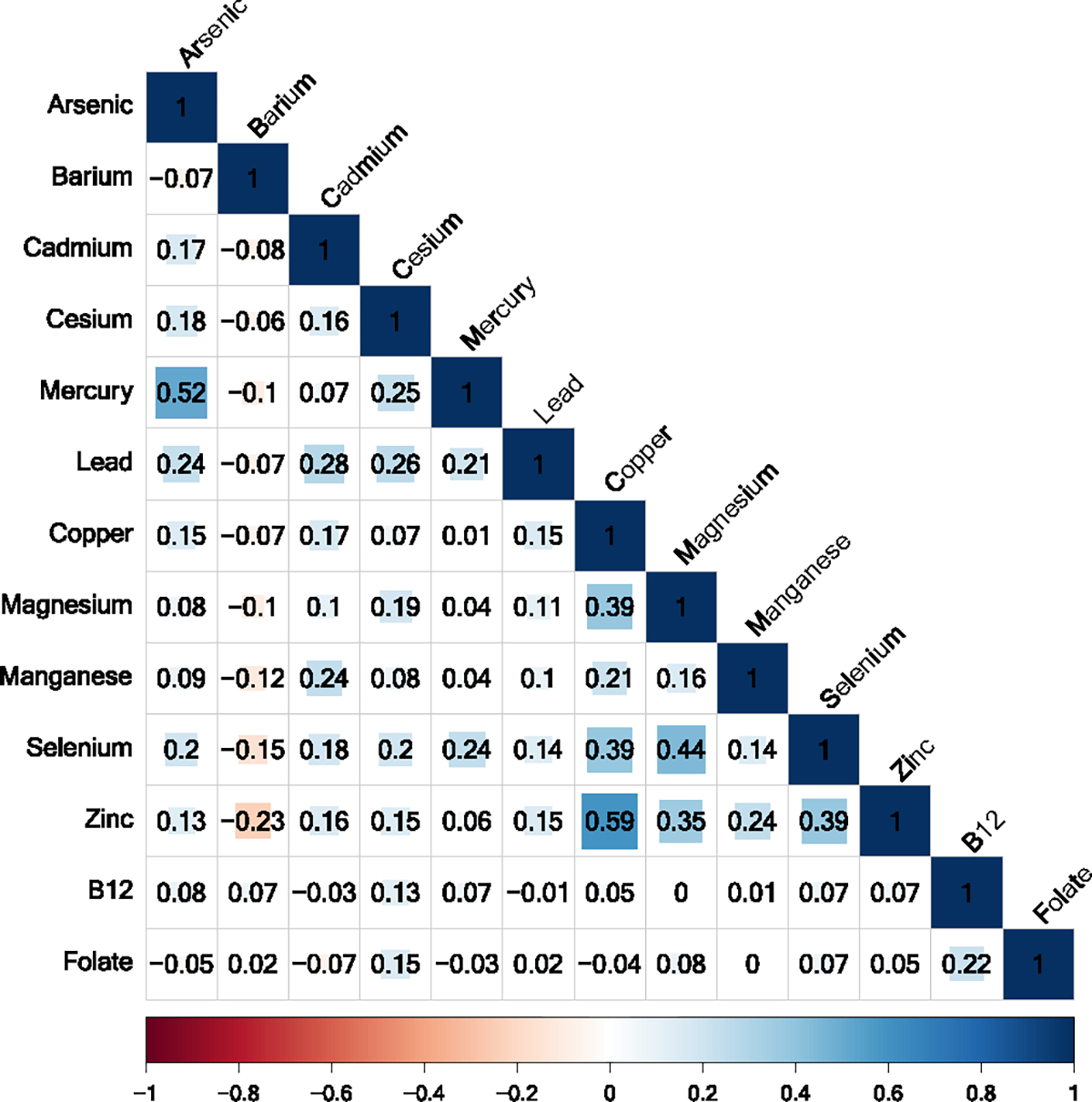

Distributions of first trimester metal concentrations and vitamins are shown in Table 2. Median concentrations of first trimester essential metals were generally within clinical laboratory reference ranges (Red Blood Cell), while median concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate were generally on the higher end of reference ranges recommended for pregnant women (Abbassi-Ghanavati et al., 2009). Similarly, median concentrations of cadmium, lead, and mercury were consistent with concentrations observed in whole blood among female participants in the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (Smith et al., 2021; National Health and Examination, 2020). Participants in this sample did not have folate concentrations below the clinical deficiency threshold (3 ng/mL), and only 8 participants (0.8 %) had vitamin B12 concentrations below the clinical deficiency threshold (200 pg/mL) (Institute of Medicine, 1998). Hemolysis occurred in 13.1 % of blood samples used to measure vitamin B12 and folate, while lipemia or hemolysis occurred in 4.1 % of blood samples (Table S2). Metals were generally weakly to moderately correlated, with the strongest correlations observed between copper and zinc (ρ = 0.59), while metals and vitamins were weakly correlated (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Distributions of first-trimester maternal erythrocyte concentrations of metals (ng/g) and plasma concentrations of vitamin B12 (pg/mL) and folate (ng/mL) among Project Viva participants (n = 1386).

| Exposure | GM ± GSD | Min | 25th percentile | Median | 75th percentile | Max | Limit of detection | % detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Arsenic | 0.77 ± 2.81 | 0.10 | 0.41 | 0.83 | 1.55 | 34.1 | 0.15 | 90 |

| Barium | 3.59 ± 2.23 | 0.29 | 2.00 | 3.17 | 5.91 | 59.2 | 0.41 | 99 |

| Cadmium | 0.38 ± 2.13 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.57 | 6.94 | 0.06 | 96 |

| Cesium | 2.51 ± 1.43 | 0.46 | 2.01 | 2.53 | 3.18 | 10.0 | 0.06 | 100 |

| Copper | 565 ± 1.19 | 86.3 | 516 | 564 | 618 | 3970 | 1.85 | 100 |

| Mercurya | 3.06 ± 2.90 | 0.21 | 1.62 | 3.26 | 6.49 | 132 | 0.30 | 96 |

| Magnesium | 41,100 ± 1.21 | 7070 | 37,000 | 41,100 | 46,000 | 77,500 | 4.15 | 100 |

| Manganese | 16.1 ± 1.55 | 0.30 | 13.1 | 16.2 | 20.3 | 44.3 | 0.42 | 100 |

| Lead | 18.0 ± 1.53 | 4.11 | 13.5 | 17.7 | 23.7 | 90.8 | 0.07 | 100 |

| Selenium | 250 ± 1.23 | 39.0 | 219 | 248 | 282 | 1090 | 1.73 | 100 |

| Zinc | 10,300 ± 1.20 | 2310 | 9260 | 10,400 | 11,600 | 26,000 | 8.74 | 100 |

| Vitamin B12b | 482 ± 1.46 | 106 | 381 | 484 | 597 | 4000 | 30 | 100 |

| Folateb | 20.80 ± 1.79 | 7.08 | 13.8 | 18.6 | 27.0 | 360 | 2.0 | 100 |

Metal concentrations below the limit of detection were assigned to the LOD/√2.

Note: GM, geometric mean; GSD, geometric standard deviation; min, minimum; max, maximum.

n = 1369.

n = 924.

Fig. 1.

Spearman correlation coefficients between first trimester maternal metal concentrations in red blood cells (ng/g), vitamin B12 (pg/mL), and folate (ng/mL) in plasma (n = 924). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Individual associations between prenatal metals and HDP

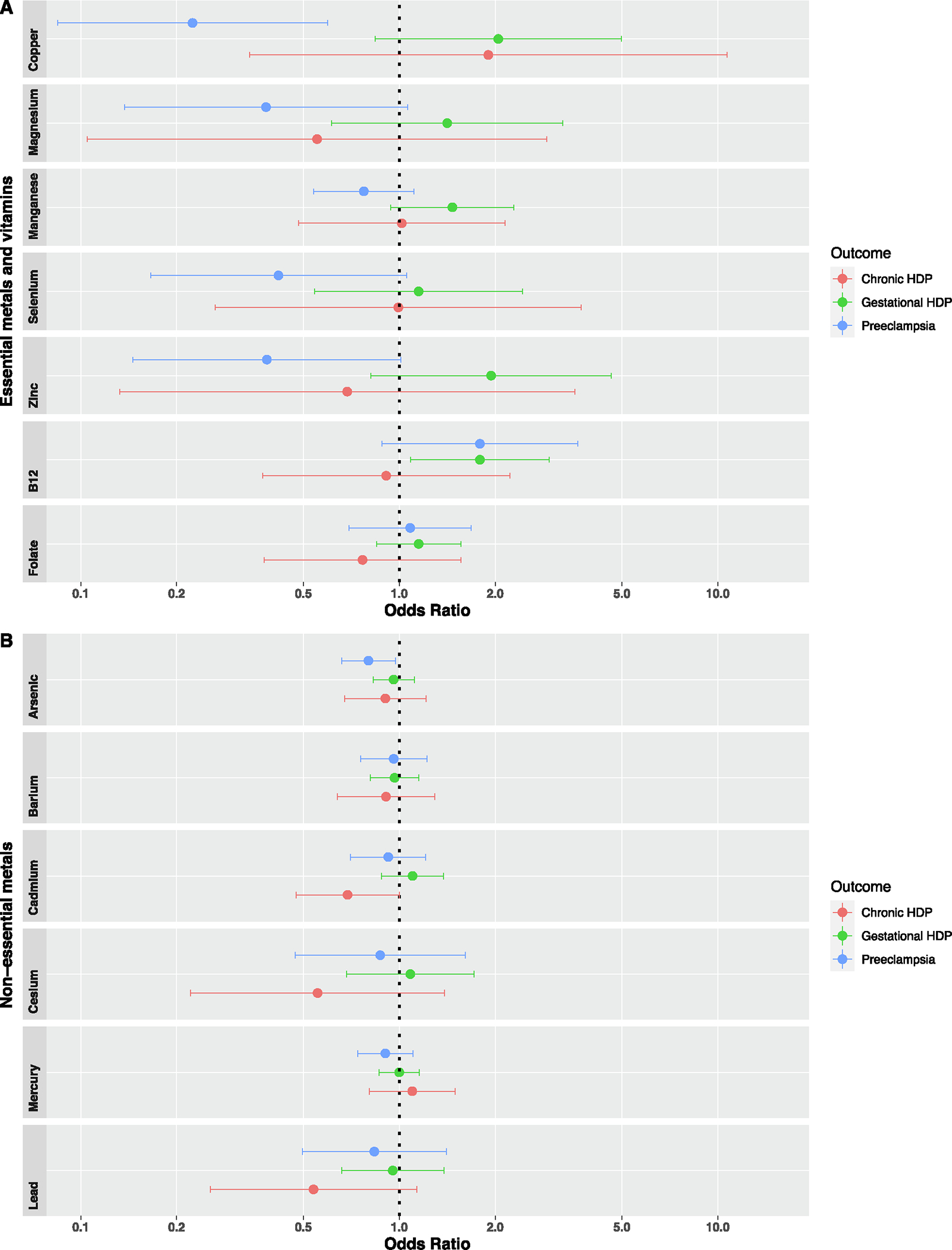

Forest plots illustrating the individual odds ratios and 95 % CIs for associations of metals and vitamins with HDP are shown in Fig. 2 and effect estimates provided in Table S3. We found lower odds of pre-eclampsia with each doubling in first trimester erythrocyte copper (OR=0.22, 95 % CI: 0.08, 0.60) and arsenic (OR=0.80, 95 % CI: 0.66, 0.97). We also observed higher odds of gestational hypertension with a doubling in vitamin B12 (OR=1.79, 95 % CI: 1.09, 2.96). Although we did not find significant associations of any of the other individual metals and vitamins with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, there were some marginal associations worth noting. For example, a doubling in zinc (OR=0.38, 95 % CI: 0.15, 1.01), selenium (OR=0.42, 95 % CI: 0.17, 1.05), and magnesium (OR=0.38, 95 % CI: 0.14, 1.06) were all associated with lower odds of preeclampsia with moderate effect sizes, but 95 % CIs included the null. For non-essential metals, we observed a marginal protective association between cadmium and odds of chronic hypertension during pregnancy (OR=0.69, 95 % CI: 0.47, 1.00).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted associations of first trimester metals and vitamins with odds of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, using multinomial logistic regression with normotensive status as the reference. Models adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, pre-pregnancy BMI, race and ethnicity, education, household income, smoking status, and parity. Note: HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. n = 924 for vitamin B12 and folate.

In subsequent sensitivity analyses evaluating individual associations after additionally adjusting for first trimester fish consumption (Table S4) and DASH diet scores (Table S5), effect estimates were consistent to primary results; however, associations between arsenic and odds of preeclampsia and prenatal vitamin B12 and odds of gestational hypertension were no longer significant after both adjustments. In order to further investigate potential confounding by maternal fish consumption among metals highly associated with dietary fish (arsenic and mercury), we conducted an additional sensitivity analyses stratifying maternal participants above vs. below the median maternal fish consumption level (median = 1.47 servings/week). Protective associations between arsenic and odds of preeclampsia were attenuated among maternal participants with less than 1.47 servings/week (OR=0.97, 95 % CI: 0.71, 1.32), when compared to participants with ≥ 1.47 servings/week (OR=0.73, 95 % CI: 0.51, 1.03). A similar pattern in attenuatation was observed between mercury and odds of preeclampsia among participants with less than 1.47 servings/week (OR=1.05, 95 % CI: 0.78, 1.42), relative to participants with ≥ 1.47 servings/week (OR=0.84, 95 % CI: 0.58, 1.21), suggesting confounding by fish intake. Additionally, in sensitivity analyses excluding current and former smokers (Table S6), associations between arsenic and odds of preeclampsia and prenatal vitamin B12 and odds of gestational hypertension were attentuated. In sensitivity analyses excluding covariate adjustment of race and ethnicity, effect estimates were consistent to the primary results (Table S7).

In sensitivity analysis additionally adjusting models for factors which may impact metal or vitamin concentrations, such as hematocrit and abnormal plasma samples with hemolysis/lipemia, effect estimates were similar to primary results (Table S8 and S9). Secondary analyses evaluating associations between prenatal metals and continuous systolic and diastolic blood pressure measures during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy also had consistent patterns to the main analysis effect estimates (Table S10), but there were significant associations only between arsenic and systolic blood pressure in the second (β = −0.29, 95 % CI: −0.55, −0.03) and third trimesters (β = −0.37, 95 % CI: −0.64, −0.10), even after additionally adjusting for dietary variables (Table S11 and Table S12).

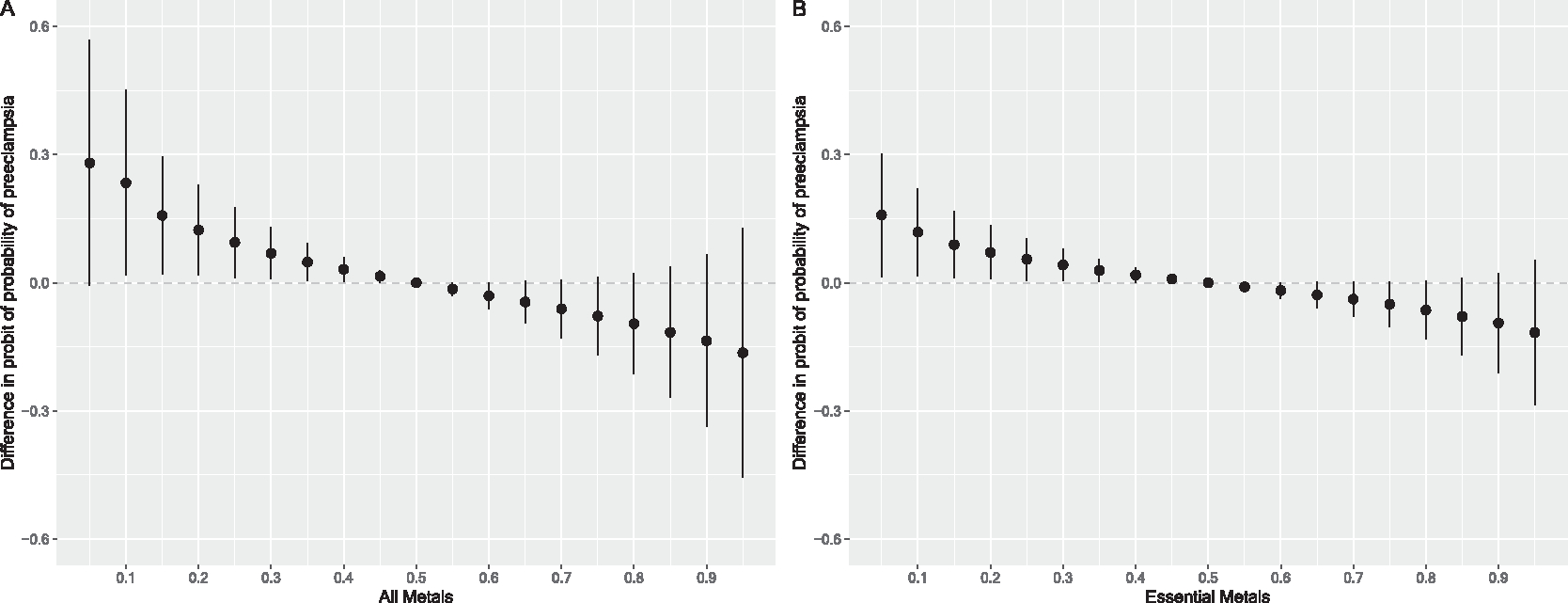

3.4. Associations between metal mixtures and HDP

Associations between the first trimester erythrocyte metal mixture and preeclampsia from BKMR analysis are shown in Fig. 3. When holding all metals at the 10th percentile relative to their 50th percentile, we found 1.45 (95 % credible interval (CrI): 1.03, 2.06) higher odds of preeclampsia, when compared to participants with no HDP (Fig. 3A). Essential metals and non-essential metals had relatively similar posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) (essential vs nonessential PIP=0.43 vs. 0.40). However, in mixture models including only essential metals and controlling for non-essential metals (Fig. 3B), lower levels of the essential metal mixture were associated with higher odds of preeclampsia, relative to the participants with no HDP (10th vs 50th percentile OR=1.21, 95 % CrI: 1.03, 1.42). In this essential metal mixture, copper had the the highest PIP (PIP=0.19) followed by magnesium (PIP=0.12) (Table S13). When examining univariate exposure–response for preeclampsia, while setting all other metals to their median (Figure S3), associations for copper were slightly u-shaped, with higher probability of preeclampsia at both higher and lower concentrations of copper. Associations between the nonessential metal mixture and preeclampsia were relatively null (Figure S4). We did not find associations between any metal mixtures and gestational hypertension (Figure S5 and Figure S6). Additionally, we did not find evidence of pairwise interactions between metals and vitamins or interactive effects by prenatal metals and vitamins (Figure S7 and S8) across mixtures models with all metals and gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

Fig. 3.

Overall association of the prenatal metal mixture on the probability of pre-eclampsia (n = 50), for A) all metals (arsenic, barium, cadmium, cesium, mercury, lead, copper, magnesium, manganese, selenium, zinc) and B) only essential metals (copper, magnesium, manganese, selenium, zinc) at different percentiles relative to the median mixture level compared to participants with no hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (n = 1226a). Figures illustrate the probit model estimates and 95 % credible intervals for preeclampsia vs. no hypertensive disorders of pregnancy metals concentrations held at the percentile specified on the x-axis when compared with setting metals to their median values. Models were adjusted for maternal age at enrollment, pre-pregnancy BMI, race and ethnicity, education, household income, smoking status, and parity. Panel B was additionally adjusted for non-essential metals. aIncludes 1204 normotensive and 22 chronic hypertensive participants.

3.5. Sensitivity analyses

When using GAMs to further evaluate potential non-linear relationships between 1st trimester erythrocyte copper and odds of pre-eclampsia (Figure S9), we found significant associations between higher copper concentrations and lower odds of preeclampsia (p = 0.01) and evidence of significant nonlinearity (Effective Degrees of Freedom = 1.26, p < 0.01). However, associations appeared relatively linear, with nonlinear associations driven by sparse outliers.

Overall associations between the full and essential metal mixture in sensitivity analyses additionally adjusting for fish consumption (Figure S10), dietary DASH scores (Figure S11), and hematocrit (Figure S12), were consistent with the overall mixtures association in the primary analysis. In sensitivity analysis refitting models without adjustment for self-reported race and ethnicity, overall associations were also consistent with the primary analysis (Figure S13). Similarly, in overall associations excluding participants with chronic hypertension who did not develop preeclampsia (Figure S14) and excluding extreme outliers (Figure S15), results were consistent with the primary analysis. We did not find associations between any metal mixtures and chronic hypertension (Figure S16). In sensitivity models of the interactive effect plots additionally adjusted for abnormal plasma samples with hemolysis/lipemia (Figure S17 and S18), we did not observe substantial changes when compared to the primary interactive plots.

In secondary analysis evaluating the overall association of metals with second and third trimester systolic (Figure S19) and diastolic (Figure S20) blood pressure measures, all credible intervals crossed the null. Patterns of associations for the full metal mixture with continuous systolic and diastolic measures in the second and third trimester were similar to those observed for the full metal mixture and probability of preeclampsia; however, results were not driven by the essential metal mixture (second trimester essential vs nonessential SBP/DBP PIP=0.21 vs 0.43/0.19 vs 0.28; third trimester essential vs nonessential SBP/DBP PIP=0.26 vs 0.52/0.25 vs 0.25). They appeared to more closely approximate patterns observed between the nonessential metal mixture and continuous blood pressure measures in both trimesters, consistent with the independent associations observed between arsenic and continuous blood pressure measures in the linear regression models.

Results from secondary analysis using quantile g-computation models (Table S14) were similar to our BKMR results. Lower odds of preeclampsia was associated with a one quartile increase in the overall metal mixture (OR=0.46, 95 % CI: 0.23, 0.95) and essential metal mixture (OR=0.62, 95 % CI: 0.39, 0.98). Consistent with our BKMR results, weights for the overall metal mixture suggested protective contributions from arsenic and copper (Figure S21). Quantile g-computation results were consistent in directions even after adjustment for dietary factors, but effect estimates were attuenated and 95 % CIs included the null (Table S15).

4. Discussion

In this prospective study examining independent and joint associations between prenatal metals, vitamins, and odds of HDP, we found that higher first trimester erythrocyte copper was associated with lower odds of preeclampsia. Results from our mixture analyses supported these findings, with significant associations between lower levels of the essential metal mixture (copper, magnesium, manganese, selenium, zinc) and higher odds of preeclampsia, primarily driven by copper. We also found associations between arsenic and lower odds of preeclampsia and positive associations between vitamin B12 and odds of gestational hypertension; however, associations were attuentuated after additionally adjusting for dietary factors. We did not find evidence of interactions by metals and vitamin B12 or folate in both individual metal and mixtures models. Similarly, we did not find evidence of overall associations between the metal mixture and gestational hypertension. Altogether, our results suggest that higher concentrations of essential metals, particularly copper, during early pregnancy may lower the risk of developing preeclampsia.

Copper functions as a cofactor for multiple cuproenzymes and plays an indispensable role in a variety of biochemical reactions and proteins, such as copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (Cu/Zn SOD) (Uauy et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2020). As an antioxidant, copper protects against free-radical damage, reducing oxidative stress levels which are hypothesized to contribute to the placental abnormalities and vascular endothelial damage observed in women with preeclampsia (Chen et al., 2020). However, excessive levels of copper can also result in potential toxicity and increased oxidative stress, due to transitions between copper’s Cu(I) and Cu(II) states which generate reactive oxygen species (De Freitas et al., 2003). Although previous epidemiological research has found protective associations between concentrations of copper and pre-eclampsia, results have been inconsistent (Rumiris et al., 2006; Lewandowska et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2016; Sak et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2022; Mistry et al., 2015; Atamer et al., 2005; Wibowo et al., 2012). For instance, in a nested case-control study conducted in Poland, participants in the lowest quartile of serum copper concentrations (≤1540.6 μg/L) at 10–14 weeks gestation were at increased odds of pregnancy-induced hypertension, when compared to participants in the highest quartile of copper concentrations (>1937.5 μg/L) (Lewandowska et al., 2019). In another randomized control trial on 110 pregnant women with low antioxidant status, antioxidant supplementation treatment from 8–12 weeks of gestation until 2 weeks’ postpartum (including copper, zinc, manganese, iron, carotene, vitamin B6, B12, C, E, selenium, and calcium) was associated with lower preeclampsia risk (Wibowo et al., 2012). However, multiple case-control and cross-sectional studies have found higher copper concentrations in women with preeclampsia (Fan et al., 2016; Sak et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2022). For example, a previous meta-analysis on 12 studies including 463 healthy pregnancy controls and 442 cases with pre-eeclampsia (samples collected after the 20th week of pregnancy) found significantly higher plasma or serum copper in individuals with pre-eclampsia (27–3366 μg/L) relative to healthy pregnancy controls (21–2810 μg/L) (Fan et al., 2016). Some studies have additionally specifically implicated Cu(II) as a possible contributor to HDP, highlighting a potential need for further examination of copper types (Stokowa-Sołtys et al., 2022). Inconsistencies between studies may be due to differences in sample collection (matrix and timing) and exposure concentrations, variability in classification of HDP, and differing study designs. It is further important to highlight that research on early pregnancy concentrations of copper and subsequent risk of preeclampsia is incredibly sparse.

Other essential metals, including magnesium, manganese, selenium, and zinc, are hypothesized to decrease risk of preeclampsia by similarly increasing antioxidant levels to buffer reactive oxygen species (Rumiris et al., 2006; Wibowo et al., 2012), which is consistent with findings in previous epidemiological studies that have observed independent associations between these essential metals and risk of preeclampsia (Liu et al., 2020; Negi et al., 2012; Bommarito et al., 2019; Wibowo et al., 2012; Mistry and Williams, 2011). Although we observed similar protective patterns between magnesium, manganese, selenium, and zinc with odds of preeclampsia in our study, these did not reach statistical significance. However, we may have been underpowered to detect these associations, given our wide confidence intervals and the small number of participants who developed preeclampsia in our sample.

Similarly, recent evidence suggests that lower concentrations of vitamins, including vitamin B12 and folic acid, may be associated with higher oxidative stress and increased risk of HDP (Liu et al., 2018; Mardali et al., 2021), but other evidence suggests the contrary (Wen et al., 2018). For instance, a multicenter randomized control trial on 2464 pregnant women with a high risk factor for pre-eclampsia found no association between folic acid supplementation (4.0 mg/day) during the first trimester of pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia (Wen et al., 2018). Another case-control study found elevated vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine in the maternal and cord blood of women with preeclampsia relative to women who did not develop preeclampsia (Pisal et al., 2019). Contrary to our expectations, we found associations between higher concentrations of vitamin B12 and increased risk of gestational hypertension, with similar non-significant patterns among women with preeclampsia. However, results were attenuated and no longer significant after adjusting for dietary variables that are a major source of metal and vitamin intake and independently associated with preeclampsia, such as overall diet quality (reflected by DASH scores) and fish consumption (NIH, 2023). This suggests that dietary variables may in part explain the overall associations observed between vitamin B12 and gestational hypertension. Additionally, we did not find evidence of interactions by folate or vitamin B12, but we may have been underpowered to detect these interactions given our well-supplemented population. High prenatal supplementation among Project Viva participants may contribute to the high levels of vitamin B12 and folate observed (Trivedi et al., 2018).

Exposure to lead is an established risk factor of preeclampsia, while other non-essential metals, such as arsenic, are risk factors of hypertension in nonpregnant populations, and suspected risk factors for HDP (Poropat et al., 2018; Balarastaghi et al., 2023; Franceschini et al., 2017). Recent epidemiological literature has found increased risk of preeclampsia with prenatal exposures to lead, cadmium, arsenic, and mercury, but some findings have been mixed (Borghese et al., 2023; Bommarito et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2019; Maduray et al., 2017). For instance, a recent study conducted among 1,560 participants in the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) study, a Canadian prospective pregnancy cohort, found that a doubling in third trimester lead (0.58 μg/dL) and first trimester arsenic (0.90 μg/dL) in blood was associated with higher risk of developing preeclampsia. This study also found positive associations between first trimester blood arsenic and gestational hypertension, with evidence of effect modification by manganese, and inverse associations between first trimester manganese (8.24 μg/dL) and gestational hypertension (Borghese et al., 2023). Similarly, a cross-sectional study by Wang et al. found positive associations between a metal mixture and preeclampsia, with associations driven by chromium, mercury, lead, and arsenic (Wang et al., 2020). In contrast to these studies, a study by Liu et al. among the Boston Birth Cohort found a positive association between cadmium and risk of preeclampsia, but null associations for lead, selenium, and mercury with preeclampsia (Liu et al., 2019). In our study, we found associations between arsenic and lower odds of preeclampsia, which were attenuated and no longer significant after adjustment for dietary sources (DASH and fish consumption). Fish consumption is a common source of arsenic and mercury, but is also a primary source of omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, and proteins essential for maternal and fetal health (Stratakis et al., 2020). We also found a marginally protective association between cadmium and chronic hypertension which was consistent in magnitude after excluding former and current smokers. However, this association could have potentially resulted from reverse causation, since participants could have modified their behavior after diagnosis of hypertension, such as by avoiding foods commonly contamined with cadmium (i.e., cereal grains and sweetmeats), possibly lowering their cadmium levels (Kim et al., 2018). We did not find similar associations between any other non-essential metals and preeclampsia, potentially due to differences across the biological matrix used by each study to measure metals (urinary versus blood measures), timing of measures, and exposure distributions. Few epidemiological studies have examined associations between barium and cesium with HDP and have generally found null results (Liu et al., 2021).

The present study had some limitations. Although we had a large analytic sample size, we may have had limited power to detect associations between a multitude of metals and vitamins and the small number of participants who developed gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Additionally, erythrocyte biomarkers are not ideal measures for all metals (NRC, 1999; Berglund et al., 2005). For example, urinary measures of arsenic can distinguish between the more toxic form of inorganic arsenic versus the less toxic form of organic arsenic found in fish (NRC, 1999). However, measures of metal concentrations in red blood cells are reliable and better suited measures for some of the other metals examined, including cadmium, lead, magnesium, and manganese (P-iD et al., 2021; Järup and Åkesson, 2009; Workinger et al., 2018; Andrade et al., 2015). For instance, concentrations of copper and cadmium in red blood cells are considered more reflective of long-term exposures, but less representative of acute exposure status (P-iD et al., 2021; Veldscholte et al., 2024). Furthermore, although we carefully selected a comprehensive set of confounders in our analyses, residual or unmeasured confounding is possible since this was an observational study. Another limitation of our study includes our limited generalizability to other pregnant persons in the US, since most participants were recruited from the greater Boston, Massachusetts area, were predominately white, and had a relatively high education and income.

Our study also has several important strengths. First, this study was conducted among a prospective pregnancy cohort, with exposure measures collected prior to our outcome of interest, allowing us to ascertain temporality of the associations. Second, we used red blood cells to measure metal concentrations, which, as previously mentioned, is considered a relatively precise and reliable measure of metal exposure for cadmium, lead, magnesium, and manganese (P-iD et al., 2021; Järup and Åkesson, 2009; Workinger et al., 2018; Andrade et al., 2015). Finally, we used robust statistical mixtures approaches, such as BKMR and quantile g-computation, to examine joint associations between essential and non-essential metals on odds of preeclampsia, along with possible interactions by vitamins.

5. Conclusion

Among a U.S. based prospective pregnancy cohort, we found that lower levels of an essential metal mixture (copper, magnesium, manganese, selenium, zinc) during the first trimester of pregnancy were associated with higher odds of preeclampsia, primarily driven by copper. Altogether, these findings contribute to a growing body of evidence suggesting prospective associations between metal concentrations and development of HDP which could help inform future research and policies. Future research should further investigate different windows of exposure susceptibility and clarify inconsistent findings in the literature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and participants of Project Viva.

Funding

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health grants R01ES031259, UG3 OD023286, P30-ES000002. Project Viva is supported by NIH grants R01HD034568 and R24ES030894. Additional financial support for training was provided by the Stanford Propel fellowship.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108909.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ixel Hernandez-Castro: Software, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Sheryl L. Rifas-Shiman: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Pi-I D. Lin: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Jorge E. Chavarro: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Diane R. Gold: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Mingyu Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Noel T. Mueller: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Tamarra James-Todd: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Brent Coull: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Marie-France Hivert: Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Emily Oken: Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. AndresCardenas: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abbassi-Ghanavati M, Greer LG, Cunningham FG, 2009. Pregnancy and laboratory studies: a reference table for clinicians. Obstet. Gynecol. 114, 1326–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuawad AK, Bozack AK, Navas-Acien A, et al. , 2023. The folic acid and creatine trial: treatment effects of supplementation on arsenic methylation indices and metabolite concentrations in blood in a bangladeshi population. Environ. Health Perspect 131, 37015. 10.1289/ehp11270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade V, Mateus M, Batoreu M, et al. , 2015. Lead, arsenic, and manganese metal mixture exposures: focus on biomarkers of effect. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 166, 13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atamer Y, Koçyigit Y, Yokus B, et al. , 2005. Lipid peroxidation, antioxidant defense, status of trace metals and leptin levels in preeclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 119 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backes CH, Markham K, Moorehead P, et al. , 2011. Maternal preeclampsia and neonatal outcomes. J. Pregnancy 2011, 214365. 10.1155/2011/214365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balarastaghi S, Rezaee R, Hayes AW, et al. , 2023. Mechanisms of arsenic exposure-induced hypertension and atherosclerosis: an updated overview. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 201, 98–113. 10.1007/s12011-022-03153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Bishop A, Needham LL, 2007. Concentrations of xenobiotic chemicals in the maternal-fetal unit. Reprod. Toxicol. 23, 260–266. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello NA, Zhou H, Cheetham TC, et al. , 2021. Prevalence of Hypertension among pregnant women when using the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association blood pressure guidelines and association with maternal and fetal outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e213808–e. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund M, Lind B, Björnberg KA, et al. , 2005. Inter-individual variations of human mercury exposure biomarkers: a cross-sectional assessment. Environ. Health 4, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb JF, Valeri L, Claus Henn B, et al. , 2015. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics 16, 493–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb JF, Claus Henn B, Valeri L, et al. , 2018. Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via Bayesian kernel machine regression. Environ. Health 17, 67. 10.1186/s12940-018-0413-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommarito PA, Kim SS, Meeker JD, et al. , 2019. Urinary trace metals, maternal circulating angiogenic biomarkers, and preeclampsia: a single-contaminant and mixture-based approach. Environ. Health 18, 63. 10.1186/s12940-019-0503-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghese MM, Fisher M, Ashley-Martin J, et al. , 2023. Individual, independent, and joint associations of toxic metals and manganese on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: results from the MIREC Canadian pregnancy cohort. Environ. Health Perspect 131. 10.1289/ehp10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozack AK, Hall MN, Liu X, et al. , 2019. Folic acid supplementation enhances arsenic methylation: results from a folic acid and creatine supplementation randomized controlled trial in Bangladesh. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 380–391. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell LC, Cluver CA, Kingdom J, et al. , 2021. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 398, 341–354. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jiang Y, Shi H, et al. , 2020. The molecular mechanisms of copper metabolism and its roles in human diseases. Pflugers Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 472, 1415–1429. 10.1007/s00424-020-02412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ou QX, Chen Y, et al. , 2022. Association between trace elements and preeclampsia: A retrospective cohort study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 72, 126971 10.1016/j.jtemb.2022.126971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter AM, Molloy AM, Scott JM, et al. , 2003. Elevated plasma homocysteine in early pregnancy: a risk factor for the development of nonsevere preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 189, 391–394. 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00669-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council NR, 1989. Diet and health: implications for reducing chronic disease risk. [PubMed]

- De Freitas J, Wintz H, Hyoun Kim J, et al. , 2003. Yeast, a model organism for iron and copper metabolism studies. Biometals 16, 185–197. 10.1023/A:1020771000746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Kang Y, Zhang M, 2016. A meta-analysis of copper level and risk of preeclampsia: evidence from 12 publications. Biosci. Rep. 36 10.1042/bsr20160197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ND, Cox S, Ko JY, et al. , 2022. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and mortality at delivery hospitalization - United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 71, 585–591. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7117a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini N, Fry RC, Balakrishnan P, et al. , 2017. Cadmium body burden and increased blood pressure in middle-aged American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. J Hum Hypertens 31, 225–230. 10.1038/jhh.2016.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness DL, Yasin N, Dekker GA, et al. , 2012. Maternal red blood cell folate concentration at 10–12 weeks gestation and pregnancy outcome. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 25, 1423. 10.3109/14767058.2011.636463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia, 2020. ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet. Gynecol. 135, e237–e260. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger JP, Alexander BT, Llinas MT, et al. , 2001. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension 38, 718–722. 10.1161/01.HYP.38.3.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate OBV, and Choline. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline., http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114310/ (1998). [PubMed]

- Järup L, Åkesson A, 2009. Current status of cadmium as an environmental health problem. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 238, 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung E, Romero R, Yeo L, et al. , 2022. The etiology of preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, S844–s866. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn LG, Trasande L, 2018. Environmental toxicant exposure and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: recent findings. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 20, 87. 10.1007/s11906-018-0888-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JB, Bennett T, 2003. Use of race and ethnicity in biomedical publication. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 289, 2709–2716. 10.1001/jama.289.20.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil AP, Buckley JP, O’Brien KM, et al. , 2020. A quantile-based g-computation approach to addressing the effects of exposure mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect. 128, 047004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Melough MM, Vance TM, et al. , 2018. Dietary cadmium intake and sources in the US. Nutrients 11. 10.3390/nu11010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lain KY, Roberts JM, 2002. Contemporary concepts of the pathogenesis and management of preeclampsia. Jama 287, 3183–3186. 10.1001/jama.287.24.3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledda C, Cannizzaro E, Lovreglio P, et al. , 2019. Exposure to toxic heavy metals can influence homocysteine metabolism? Antioxidants (Basel) 9. 10.3390/antiox9010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YM, Lee MK, Bae SG, et al. , 2012. Association of homocysteine levels with blood lead levels and micronutrients in the US general population. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 45, 387–393. 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.6.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska M, Sajdak S, Marciniak W, et al. , 2019. First trimester serum copper or zinc levels, and risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Nutrients 11, 2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Zhang M, Guallar E, et al. , 2019. Trace minerals, heavy metals, and preeclampsia: findings from the boston birth cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012436. 10.1161/JAHA.119.012436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Hivert MF, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. , 2020. Prospective association between manganese in early pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia. Epidemiology 31, 677–680. 10.1097/ede.0000000000001227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Liu C, Wang Q, et al. , 2018. Supplementation of folic acid in pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension: a meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 298, 697–704. 10.1007/s00404-018-4823-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Zhang M, Rahman ML, et al. , 2021. Exposure to heavy metals and trace minerals in first trimester and maternal blood pressure change over gestation. Environ. Int. 153, 106508 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo JO, Mission JF, Caughey AB, 2013. Hypertensive disease of pregnancy and maternal mortality. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 25, 124–132. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835e0ef5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZC, An N, Xu HR, et al. , 2007. The effects and mechanisms of primiparity on the risk of pre-eclampsia: a systematic review. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 21 (Suppl 1), 36–45. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduray K, Moodley J, Soobramoney C, et al. , 2017. Elemental analysis of serum and hair from pre-eclamptic South African women. J. Trace Elem. Med Biol. 43, 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S, Maiti A, Karmakar S, et al. , 2012. Antiapoptotic efficacy of folic acid and vitamin B12 against arsenic-induced toxicity. Environ. Toxicol. 27, 351–363. 10.1002/tox.20648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardali F, Fatahi S, Alinaghizadeh M, et al. , 2021. Association between abnormal maternal serum levels of vitamin B12 and preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 79, 518–528. 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezo Y, Elder K, Clement A, et al. , 2022. Folic Acid, folinic acid, 5 methyl tetrahydrofolate supplementation for mutations that affect epigenesis through the folate and one-carbon cycles. Biomolecules 12. 10.3390/biom12020197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersha TB, Beck AF, 2020. The social, economic, political, and genetic value of race and ethnicity in 2020. Hum. Genomics 14, 37. 10.1186/s40246-020-00284-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry HD, Gill CA, Kurlak LO, et al. , 2015. Association between maternal micronutrient status, oxidative stress, and common genetic variants in antioxidant enzymes at 15 weeks ׳gestation in nulliparous women who subsequently develop preeclampsia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 78, 147–155. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry HD, Williams PJ, 2011. The importance of antioxidant micronutrients in pregnancy. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2011 10.1155/2011/841749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 2017–2018 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies, Lead, Cadmium, Total Mercury, Selenium, & Manganese—Blood (PBCD_J), https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/PBCD_J.htm (2020).

- Negi R, Pande D, Karki K, et al. , 2012. Trace elements and antioxidant enzymes associated with oxidative stress in the pre-eclamptic/eclamptic mothers during fetal circulation. Clin. Nutr. 31, 946–950. 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH: National Heart L, and Blood Institute Description of the DASH eating plan, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/education/dash-eating-plan (2023).

- NRC. Chapter 6: Biomarkers of Arsenic Exposure. National Academies Press; Washington, DC, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Ning Y, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. , 2007. Diet during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension. Ann. Epidemiol. 17, 663–668. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Baccarelli AA, Gold DR, et al. , 2015. Cohort profile: project viva. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary F, Samman S, 2010. Vitamin B12 in health and disease. Nutrients 2, 299–316. 10.3390/nu2030299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Werler MM, 2014. Epidemiology of ischemic placental disease: a focus on preterm gestations. Semin Perinatol. 38, 133–138. 10.1053/j.semperi.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- P-iD L, Cardenas A, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. , 2021. Diet and erythrocyte metal concentrations in early pregnancy—cross-sectional analysis in Project Viva. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 114, 540–549. 10.1093/ajcn/nqab088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg R, Anthony J, Davey da,, et al. , 1991. Placental bed spiral arteries in the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 98, 648–655. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb13450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisal H, Dangat K, Randhir K, et al. , 2019. Higher maternal plasma folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels in women with preeclampsia. J. Hum. Hypertens. 33, 393–399. 10.1038/s41371-019-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poropat AE, Laidlaw MAS, Lanphear B, et al. , 2018. Blood lead and preeclampsia: a meta-analysis and review of implications. Environ. Res. 160, 12–19. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raijmakers MTM, Dechend R, Poston L, 2004. Oxidative stress and preeclampsia. Hypertension 44, 374–380. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000141085.98320.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inc. DsD. Red Blood Cell (RBC) Elements, https://newsite.doctorsdata.com/Red-Blood-Cell-Elements.

- Rifas-Shiman SL, Aris IM, Switkowski KM, et al. , 2023. Cohort profile update: project viva mothers. Int. J. Epidemiol. 52, e332–e339. 10.1093/ije/dyad137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumiris D, Purwosunu Y, Wibowo N, et al. , 2006. Lower rate of preeclampsia after antioxidant supplementation in pregnant women with low antioxidant status. Hypertens. Pregnancy 25, 241–253. 10.1080/10641950600913016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sak S, Barut M, Çelik H, et al. , 2020. Copper and ceruloplasmin levels are closely related to the severity of preeclampsia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 33, 96–102. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1487934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva I, Bracchi I, Keating E, 2023. The association between selenium levels and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review of the literature. Br. J. Nutr. 130, 651–665. 10.1017/s0007114522003671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Lin P-I-D, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. , 2021. Prospective associations of early pregnancy metal mixtures with mitochondria DNA copy number and telomere length in maternal and cord blood. Environ. Health Perspect. 129, 117007 10.1289/EHP9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokowa-Sołtys K, Szczerba K, Pacewicz M, et al. , 2022. Interactions of neurokinin B with copper(II) ions and their potential biological consequences. Dalton Trans. 51, 14267–14276. 10.1039/d2dt02033e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis N, Conti DV, Borras E, et al. , 2020. Association of fish consumption and mercury exposure during pregnancy with metabolic health and inflammatory biomarkers in children. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e201007–e. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou PB, Yedjou CG, Patlolla AK, et al. , 2012. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Exp. Suppl. 101, 133–164. 10.1007/978-3-7643-8340-4_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor J, Van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, et al. , 2016. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty’. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 1887–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilakaratne R, Lin P-I-D, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. , 2023. Mixtures of metals and micronutrients in early pregnancy and cognition in early and mid-childhood: findings from the project viva cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 131, 087008 10.1289/EHP12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MK, Sharma S, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. , 2018. Folic acid in pregnancy and childhood asthma: a US cohort. Clin. Pediatr. 57, 421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uauy R, Olivares M, Gonzalez M, 1998. Essentiality of copper in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 67, 952s–959s. 10.1093/ajcn/67.5.952S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldscholte K, Al Fify M, Catchpole A, et al. , 2024. Plasma and red blood cell concentrations of zinc, copper, selenium and magnesium in the first week of paediatric critical illness. Clin. Nutr. 43, 543–551. 10.1016/j.clnu.2024.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, DiBari J, Bind E, et al. , 2019. Association between maternal exposure to lead, maternal folate status, and intergenerational risk of childhood overweight and obesity. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1912343. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang K, Han T, et al. , 2020. Exposure to multiple metals and prevalence for preeclampsia in Taiyuan China. Environ Int 145. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen SW, White RR, Rybak N, et al. , 2018. Effect of high dose folic acid supplementation in pregnancy on pre-eclampsia (FACT): double blind, phase III, randomised controlled, international, multicentre trial. Bmj 362. 10.1136/bmj.k3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo N, Purwosunu Y, Sekizawa A, et al. , 2012. Antioxidant supplementation in pregnant women with low antioxidant status. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 38, 1152–1161. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workinger JL, Doyle RP, Bortz J, 2018. Challenges in the diagnosis of magnesium status. Nutrients 10, 1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Cobbina SJ, Mao G, et al. , 2016. A review of toxicity and mechanisms of individual and mixtures of heavy metals in the environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 8244–8259. 10.1007/s11356-016-6333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Sun X, Wang X, et al. , 2021. The association between the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and folic acid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 24, 174–190. 10.18433/jpps31500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Liu T, Wang G, et al. , 2021. In utero exposure to heavy metals and trace elements and childhood blood pressure in a U.S. urban, low-income, minority birth cohort. Environ. Health Perspect 129, 67005. 10.1289/ehp8325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z, Yang Q, Sun T, et al. , 2022. A global perspective of correlation between maternal copper levels and preeclampsia in the 21st century: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health 10. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.