Abstract

Cell-cycle checkpoints induced by DNA damage or replication play critical roles in the maintenance of genomic integrity during cell proliferation. Biochemical analysis of checkpoint pathways has been greatly facilitated by the use of cell-free systems made from Xenopus eggs. In the present study, we describe a human cell-free system that reproduces a DNA-dependent checkpoint pathway acting on the Chk1 protein kinase. In this system, double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides induce the phosphorylation of Chk1 at activating sites targeted by ATR [ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated)- and Rad3-related] and ATM kinases. Phosphorylation of Chk1 is dependent on the interaction of Claspin, a protein first identified in Xenopus as a Chk1-binding protein. We show that the DNA-dependent binding of Chk1 to Claspin requires two phosphorylation sites, Thr916 and Ser945, which lie within the Chk1-binding domain of Claspin. Using a phosphopeptide derived from the consensus motif of these sites, we show that the interaction of Claspin with Chk1 is required for the ATR/ATM-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1. Using a panel of protein kinase inhibitors, we provide evidence that Chk1 is phosphorylated at an additional site in response to activation of the checkpoint response, probably by autophosphorylation. Claspin is phosphorylated in the Chk1-binding domain in an ATR/ATM-dependent manner and is also targeted by additional kinases in response to double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides. This cell-free system will facilitate further biochemical analysis of the Chk1 pathway in humans.

Keywords: cell cycle, checkpoint, Chk1, Claspin, DNA damage, protein kinase

Abbreviations: ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated; ATR, ATM- and Rad3-related; CKBD, Chk1-binding domain; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; DTT, dithiothreitol; GST, glutathione S-transferase; OA, okadaic acid; Xatr, Xenopus laevis homologue of ATR; Xchk1, X. laevis homologue of Chk1

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic cells maintain genomic integrity by monitoring DNA for damage or incomplete replication. In the event of aberrant structures being detected, checkpoint mechanisms are activated that delay cell-cycle progression and allow the damage to be repaired or replication to be completed. Genetic analysis in yeasts has identified a number of components of the checkpoint mechanisms that are conserved in other eukaryotes, including vertebrates [1,2]. A central component of one such pathway is the Chk1 protein kinase [3]. In response to DNA damage or replication arrest, Chk1 inhibits the Cdc25 phosphatase [4–10] and activates the Wee1 kinase [11,12], which together control inhibitory phosphorylation sites on the Cdc2/cyclin B protein kinase, a critical regulator of the G2/M phase transition [13]. In mammalian cells, in addition to its role in controlling entry into mitosis, Chk1 controls progression through S-phase, partly by phosphorylating Cdc25A and initiating its degradation [6,14,15].

Activation of Chk1 requires members of a family of large PIK (phosphatidylinositol kinase)-related enzymes [1,2]. In vertebrates, activation of Chk1 in response to DNA damage or replication arrest induced by UV or hydroxyurea involves ATR (ATM- and Rad3-related) kinase. ATR phosphorylates Chk1 at Ser317 and Ser345 in vitro, and phosphorylation of these sites in human cells in response to UV and hydroxyurea is ATR-dependent [16–19]. Chk1 may also be phosphorylated by the related kinase ATM at Ser317 in response to ionizing radiation [20] and undergoes autophosphorylation associated with its full activation [21]. Defects in the Chk1 pathway have been implicated in the loss of genomic stability and in development of cancer [16,22–24]. Conversely, the component kinases have been proposed as potential anticancer drug targets [25]. To understand the role of these pathways in cell-cycle control and their potential as drug targets, the molecular interactions between components and their regulation by phosphorylation need to be characterized.

Checkpoint responses to damaged or incompletely replicated DNA can be studied under near-physiological conditions in cell-free extracts prepared from Xenopus laevis eggs [26]. In this system, inhibition of DNA replication in nuclei formed in the extracts causes the activation of Xchk1 (X. laevis homologue of Chk1). Activation of Xchk1 can also be induced in the absence of nuclei by DNA templates, which appear to mimic incompletely replicated DNA or aberrant structures that activate the checkpoint [27,28], and depends on Xatr (X. laevis homologue of vertebrate ATR), which phosphorylates conserved SQ/TQ (Ser-Gln/Thr-Gln) sites in Xchk1 [29,30]. Phosphorylation and activation of Xchk1 requires Claspin, a protein that co-purifies with Xchk1, suggesting that Claspin may act as a scaffolding protein that brings together Xatr and Xchk1 [28,31]. Claspin interacts with chromatin during the S-phase, indicating that it may also act as a sensor of DNA replication [32]. The interaction of Claspin with Chk1 requires two phosphorylation sites in a tandem motif that lies within the CKBD (Chk1-binding domain) [33], which interacts with the kinase domain of Chk1 [34]. Phosphorylation of these two sites appears to be Xatr-dependent, but may not be directly catalysed by Xatr [33]. In cultured human cells, depletion of the homologue of Claspin by a small interfering RNA indicates that Claspin is also required for Chk1 phosphorylation in response to genotoxic stress in mammals [35,36]. Human Claspin is phosphorylated in an ATR-dependent manner and co-precipitates with Chk1 [35,36]. However, it has been unclear which kinases phosphorylate human Claspin and whether the phosphorylated motifs in Xenopus Claspin are functionally conserved in the human homologue.

In the present study, we report the development of a human cell-free system in which a checkpoint pathway targeting Chk1 can be analysed biochemically. Using this system, we show that double-stranded oligonucleotides trigger both the phosphorylation of Chk1 at sites targeted by ATR/ATM and the phosphorylation of Claspin. Claspin interacts with Chk1, and this binding requires two phosphorylation sites in the Chk1-binding domain of Claspin that correspond to those in the Xenopus homologue. Using a phosphopeptide located on the interaction motif, we demonstrate that the interaction of Claspin with Chk1 is required for the phosphorylation of Chk1 and partially for the phosphorylation of Claspin. We also show that both Chk1 and Claspin are phosphorylated by DNA-activated kinases that are probably distinct from ATR/ATM.

EXPERIMENTAL

Molecular cloning and mutation of Claspin

Human Claspin (EMBL accession number AF297866) was obtained by reverse transcriptase–PCR from polyadenylated RNA isolated from HeLa cells and cloned into a Gateway entry vector (pENTR3C; Invitrogen). A CKBD (amino acids 908–953) was generated by PCR to include a 5′-CACC sequence that can be used by a viral topoisomerase I enzyme to insert the fragment into the TOPO-D entry vector (site-directed mutagenesis was later used to create a stop codon at the end of the CKBD) and used to transform TOP10 Escherichia coli. A recombination reaction was performed to transfer the inserts from these entry vectors into destination vectors to generate pcDNA(3.2)DEST-Claspin and pDEST-15-CKBD, which were used to transform E. coli DH5α cells. Site-directed mutagenesis of pcDNA(3.2)DEST-Claspin was used to create a stop codon so that the truncated sequence would be expressed as an N-terminal fragment, Claspin1–678. To generate a C-terminal fragment, Claspin679–1332, a convenient internal EcoRI site was used to subclone into a pET vector (Novagen, Madison, WI, U.S.A.). Claspin mutants T916A (Thr916→Ala) S945A and S982A were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. His6-tagged 35S-labelled Claspin proteins were expressed in reticulocyte lysate using the TnT Quick-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega, Chilworth, Southampton, U.K.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antibodies

Antibodies against human Chk1 used for immunoprecipitation were raised in sheep inoculated with GST (glutathione S-transferase)–Chk1 [37] and purified against the protein coupled with Reactigel beads (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hemel Hempstead, Herts., U.K.). Commercial antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-Claspin (Ab73; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, U.S.A.); goat anti-ATR [FRP1 (FRAP-related protein1); N-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Autogen Bioclear, calne, Wiltshire, U.K.]; mouse monoclonal anti-Chk1 (G4; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for Western blotting; rabbit anti-Chk1 phosphorylated Ser345, Ser317 and Ser296 sites (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, U.S.A.); and mouse monoclonal anti-tetra-His (Qiagen, Crawley, West Sussex, U.K.). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were anti-mouse Ig (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Bucks., U.K.), anti-rabbit Ig (Bio-Rad Laboratories) or anti-goat Ig (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Human cell extracts

Nuclear and cytoplasmic S100 extracts, prepared from exponentially growing HeLa cells by the method of Dignam et al. [38], were purchased from Cilbiotech (Mons, Belgium). S100 extracts were supplied in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM DTT (dithiothreitol). Nuclear extracts were supplied in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 M KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF and 0.5 mM DTT. Extracts, which were supplied frozen, were thawed on ice, aliquoted, then snap-frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. Protein concentrations were approx. 10 mg/ml for S100 and 20 mg/ml for nuclear extract, as determined by DC protein concentration assay (Bio-Rad Laborotaries).

Phosphorylation of Chk1 and Claspin in cell extracts

Routinely, a 1:1 mixture of nuclear extract and S100 was incubated for 30 min at 30 °C in the presence of 50 ng/μl poly(dA/dT)70 (synthesized by MWG-Biotech, Milton Keynes, U.K. and annealed as described previously [39]), 10 μM okadaic acid (BioMol, Plymouth Meeting, PA, U.S.A.), 1 mM ATP, 10 ng/μl creatine kinase, 5 mM phosphocreatine (Sigma) and 0.02 μl of in vitro translation product/μl of extract. For each sample, 75 μg of protein was run on a 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel and analysed by Western blotting or autoradiography. For inhibition of kinases, inhibitors were added to the extract at the following concentrations: 5 μM staurosporine, 5 μM roscovitine, 50 μM SB203580, 50 μM PD98059, 10 μM rapamycin, 10 μM H89, 20 μM Bim1, 20 μM Ro318220, 20 μM Gö6976 (all from Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), 5 mM caffeine (Sigma) and 1 μM UCN01 (a gift from Dr R. J. Schultz, Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MA, U.S.A.). Peptides synthesized by the Protein and Peptide Chemistry Facility (London Research Institute, Cancer Research U.K.) were MDELLDLCS(p)GKFTSQ (PS), where S(p) indicates phosphoserine, MDELLDLCAGKFTSQ (AS), MDELLDLCSGKFTSQ (SS) and ATPFQEGLRTFDQLD as an unrelated control peptide derived from human caspase 9. For peptide inhibition, peptides were diluted in water and added at 1 μg/μl or at the indicated concentrations.

Dephosphorylation of Claspin

Claspin and Claspin679–1332, His6-tagged at the C- and N-terminal, respectively, were expressed as 35S-labelled proteins in reticulocyte lysate and phosphorylated by incubation in 30 μl of extract. Claspin proteins were precipitated by incubation for 1 h at 4 °C with nickel–agarose beads (Qiagen), which were recovered by centrifugation, washed four times with 1 ml of HBS (Hepes-buffered saline; 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl) and resuspended in 200 μl of phosphatase reaction buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, 2 mM MnCl2, 5 mM DTT and 0.01%, v/v, Brij-35) containing 400 units of λ protein phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, Herts., U.K.). After incubation for 1 h at 30 °C, samples were analysed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography.

Immunoprecipitation of Chk1

Chk1 was phosphorylated in 600 μg of extract in the presence of 2 μl of in vitro translated Claspin, then immunoprecipitated for 1 h at 4 °C using sheep anti-Chk1 or control sheep anti-XMOG1 antibodies, prebound (in the presence of 2%, w/v, BSA) to Protein G Dynabeads (Dynal, Bromborough, Wirral, Cheshire, U.K.). Beads were isolated using a Dynal magnetic particle concentrator and washed once with HeLa nuclear extract buffer, twice with wash buffer A [10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1%,(w/v) Chaps, 2.5 mM EGTA and 20 mM β-glycerol phosphate] and once with HBS. Proteins were boiled off the beads into SDS loading buffer and analysed by Western blotting with a mouse monoclonal antibody against Chk1 or autoradiography.

RESULTS

Chk1 is phosphorylated in a human cell-free system in response to oligonucleotides

Previous studies using Xenopus egg extracts have demonstrated that a DNA structure checkpoint response can be induced by the addition of oligonucleotides that mimic unreplicated DNA or aberrant DNA structures [27,39]. In that system, Chk1 is phosphorylated and activated in response to dsDNA (double-stranded DNA), but not single-stranded DNA of length 70 nt. The response is enhanced by addition of protein-serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors [28].

To develop a human cell-free system in which activation of the Chk1 pathway might be studied, we used nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts prepared from exponentially growing HeLa cells and added an ATP regenerating system to sustain kinase activity. We tested the response of each extract alone or mixed together, with the addition of annealed oligomers of poly(dA)70 and poly(dT)70 [hereafter referred to as poly(dA/dT)70], with or without simultaneous addition of the phosphatase inhibitor OA (okadaic acid). Endogenous Chk1 was detected by Western blotting and its phosphorylation was assessed by mobility shift on SDS/PAGE and by Western blotting using antibodies raised against specific phosphorylation sites (Figure 1A). No response to OA or poly(dA/dT)70 was observed in the cytosolic S100 extracts, but, in the nuclear extract, OA alone caused a slight decrease in mobility of Chk1 on SDS/PAGE. This upshift correlated with weak phosphorylation at Ser345, a site phosphorylated by ATR in cells in response to checkpoint stimuli [16–19]. Phosphorylation at Ser345 and the upshift were greatly enhanced by the simultaneous addition of poly(dA/dT)70 with OA, whereas poly(dA/dT)70 alone produced only a very weak response. A mixture of equal volumes of nuclear and cytosolic extracts was found to respond to OA+poly(dA/dT)70 more strongly and consistently than the nuclear extract alone. The upshift in Chk1 and phosphorylation of Ser345 were completely prevented if the ATP-regenerating system was omitted or EDTA (which chelates Mg2+ required for kinase activity) was added (Figure 1A). Examining the time course of the response, we found that the phosphorylation of Chk1 was appreciable after 20 min incubation with poly(dA/dT)70 and OA, reaching a maximum after approx. 30 min, and was thereafter maintained for at least 120 min (Figure 1B). Therefore a mixture of nuclear and cytosolic extracts incubated for 30 min at 30 °C was used for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1. Chk1 is phosphorylated at activating sites in a human cell-free system in response to double-stranded oligonucleotides.

(A) Phosphorylation of Chk1 in HeLa cell extracts. HeLa cytoplasmic extract (S100), nuclear extract (HNE) and a mixture of equal volumes of the two (HNE/S100) were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min with or without an ATP-regenerating system, 10 μM OA and 50 ng/μl poly(dA/dT)70, as indicated. One sample contained 10 mM EDTA to block kinase activity. Western blots of protein separated by gel electrophoresis were probed with antibodies to Chk1 (anti-Chk1) or the phosphorylated Ser345 site in Chk1 (α-p345). (B) Time course of Chk1 phosphorylation. The extract was incubated with OA and poly(dA/dT)70 for the times shown and blotted with antibodies to Chk1 (anti-Chk1). (C) Chk1 is phosphorylated on Ser345 in response to dsDNA, not single-stranded DNA. The extract was incubated with OA and poly(dA/dT)70, poly(dA)70, poly(dT)70 or poly(dA/dT)40 as indicated, then Western blotted with either anti-Chk1 or α-p345. (D) Phosphorylation of Chk1 on Ser296 and Ser317 in response to oligonucleotides. The extract was incubated with OA and poly(dA/dT)70 as indicated and Western blotted with antibodies to Chk1 (anti-Chk1) and the phosphorylated Ser296 (α-p296) and Ser317 (α-p317) sites in Chk1.

To determine the specificity of the response to DNA, the combined extract was then tested with other oligonucleotides together with OA (Figure 1C). In contrast with the effect seen for double-stranded poly(dA/dT)70, no oligonucleotide-dependent phosphorylation was seen when single-stranded oligonucleotides, poly(dA)70 or poly(dT)70, were added. A shorter double-stranded molecule of 40 paired nucleotides, poly(dA/dT)40, induced weaker phosphorylation than poly(dA/dT)70 of Chk1 at an ATR-targeted site, Ser345. We also examined the phosphorylation of Chk1 at two other sites: Ser317, which is modified in cells by ATR in response to UV and hydroxyurea [18,19] and by ATM in response to ionizing radiation [20], and Ser296, which is phosphorylated in a variety of cell lines treated with UV or hydroxyurea [40]. Phosphorylation of both sites was induced by OA and poly(dA/dT)70, although poly(dA/dT)70 did not stimulate the phosphorylation of Ser296 significantly when compared with OA alone (Figure 1D).

Phosphorylation of human Claspin

In Xenopus egg extract, Chk1 phosphorylation is dependent on the phosphorylation of its binding partner, Claspin [28]. In that system, Claspin is phosphorylated towards the C-terminus in an Xatr-dependent manner that allows it to bind to Xchk1 [33]. In human cell extract, endogenous Claspin also appeared to be phosphorylated in the presence of OA and poly(dA/dT)70, as determined by its retardation on an SDS/polyacrylamide gel, detected on a Western blot with an anti-Claspin antibody (Figure 2A). No upshift of Claspin was observed in the absence of the ATP-regenerating system or in the presence of EDTA (results not shown), consistent with a requirement for protein kinase activity. Claspin was phosphorylated weakly in the presence of OA alone, but underwent further phosphorylation in the presence of poly(dA/dT)70. The phosphorylation of Claspin correlated with the phosphorylation of Chk1 at Ser345 (Figure 2A). In vitro translated 35S-labelled full-length Claspin incubated in human cell extract also underwent a clear upshift in the presence of OA and poly(dA/dT)70, with the appearance of numerous upshifted forms that suggested multiple phosphorylation sites. A truncated form consisting of the C-terminal half of the protein (residues 679–1332; Claspin679–1332) was also upshifted, whereas a truncation containing the N-terminal half of the protein (residues 1–678; Claspin1–678) did not undergo a substantial shift (Figure 2B). These results indicated that human Claspin was phosphorylated at several sites in the C-terminal portion of the protein in a poly(dA/dT)70- and OA-dependent manner. When we precipitated full-length Claspin or Claspin679–1332 from extracts after incubation with poly(dA/dT)70 and OA, subsequent treatment with λ-protein phosphatase completely reversed the upshift, confirming that it was due to phosphorylation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Human Claspin is phosphorylated within its C-terminal half in response to double-stranded oligonucleotides.

(A) Phosphorylation of endogenous Claspin. The extract was incubated with OA and poly(dA/dT)70 as indicated and blotted with antibodies to Chk1 (anti-Chk1), the phosphorylated Ser345 site in Chk1 (α-p345) and Claspin (anti-Claspin). (B) Phosphorylation of recombinant Claspin within residues 679–1332. The extract was incubated with radiolabelled fulllength Claspin, Claspin1–678 or Claspin679–1332, with or without OA and poly(dA/dT)70 as indicated. Proteins were detected by autoradiography. (C) Dephosphorylation of recombinant Claspin. The extract was incubated with radiolabelled His6-tagged full-length Claspin or Claspin679–1332, with or without OA+poly(dA/dT)70, as indicated. Proteins were precipitated, incubated further with or without protein phosphatase (λ-PPase), separated by SDS/PAGE and detected by autoradiography.

Association of phosphorylated Claspin with Chk1

To test for interaction with Chk1, radiolabelled full-length Claspin, Claspin1–678 or Claspin679–1332 was incubated in the extract, and endogenous Chk1 was retrieved by immunoprecipitation. As observed previously for Xenopus Claspin [33], there was significant non-specific binding of unphosphorylated full-length Claspin or Claspin679–1332 to beads. However, when phosphorylation was induced by OA and poly(dA/dT)70, Claspin precipitated specifically with Chk1 and not with control precipitations. Both phosphorylated full-length Claspin and Claspin679–1332 precipitated specifically with Chk1, whereas Claspin1–678 failed to interact (Figure 3). Therefore human Claspin, similar to its Xenopus homologue, interacts specifically with Chk1 when it is phosphorylated in its C-terminal region.

Figure 3. Phosphorylated Claspin co-precipitates with Chk1.

The extract was incubated with radiolabelled full-length Claspin (1–1332), Claspin679–1332 or Claspin1–678, with or without OA and poly(dA/dT)70 as indicated, then precipitated (IP) with Protein G Dynal beads bound to either anti-Chk1 or control antibodies (both sheep). Beads were washed and proteins were boiled off the beads and analysed by autoradiography or blotting for Chk1 using a mouse monoclonal antibody. Extracts before precipitation were also analysed.

Thr916 and Ser945 in Claspin are required for binding to Chk1

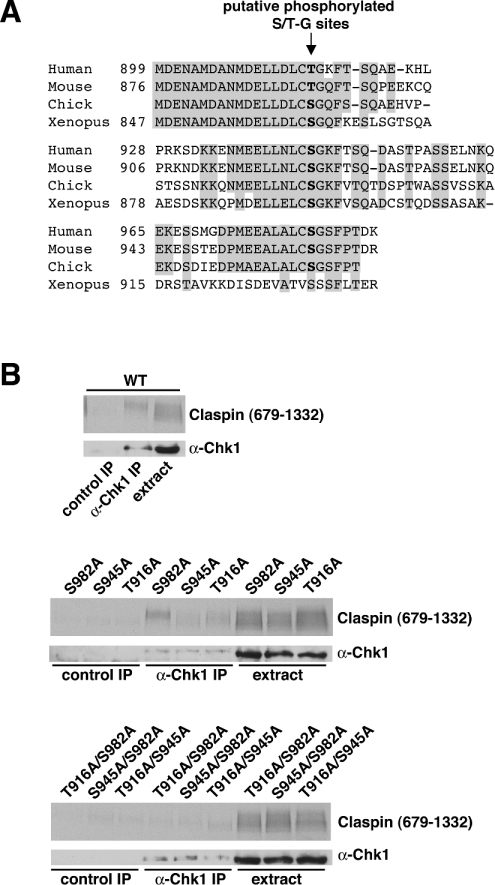

In Xenopus, the binding interaction between Claspin and Chk1 requires a region of approx. 57 amino acids within the C-terminal portion of Claspin that contains two phosphorylation sites, Ser864 and Ser895, each of which is followed by a glycine residue. Phosphorylation of these SG (Ser-Gly) sites creates two recognition motifs for binding to Chk1 [33], which interacts through its N-terminal kinase domain [34]. The SG motif appears to be repeated a third time in Claspin homologues from human, mouse and chick, but not Xenopus [33] (Figure 4A). In Xenopus Claspin, the phosphorylated residues involved in the interaction are both serine residues, whereas, in the first repeat in the human and mouse sequences, the equivalent residue is a threonine. To determine which, if any, of the three putative phosphorylation sites in human Claspin is required for the interaction with Chk1, Claspin697–1332 proteins with point mutations at each site were generated and tested for their ability to bind Chk1 in the human cell-free system in the presence of OA and poly(dA/dT)70 (Figure 4B). Mutation of either Thr916 or Ser945 in Claspin679–1332 to a non-phosphorylatable alanine residue impaired co-precipitation with Chk1, indicating that loss of phosphorylation at either site alone significantly decreases affinity for Chk1. However, when Ser982 was mutated to an alanine residue, the mutant bound to Chk1 to a similar extent as wild-type Claspin679–1332, indicating that phosphorylation of the third repeat sequence is less important for the interaction between proteins. Nevertheless, mutants with two putative phosphorylation sites changed to alanine simultaneously, abolished binding in all cases, suggesting that Ser982 may play a role in the interaction with Chk1 in the absence of either Thr916 or Ser945.

Figure 4. Thr916 and Ser945 in Claspin are essential for the binding interaction with Chk1.

(A) Alignment of putative Chk1-binding domains in Claspin homologues from different vertebrates. Regions where the sequence is conserved between three species (including either serine or threonine residues) are shaded. The position of aligned putative Ser-Gly or Thr-Gly phosphorylation sites is indicated. (B) Mutational analysis of the putative Chk1-binding domain in human Claspin. Claspin679–1332 (WT, upper panel) and mutants in which each of the three putative phosphorylation sites, Thr916, Ser946 and Ser982, were changed to alanine (T916A, S945A and S982A) as single (middle panel) or double (lower panel) mutants were incubated with extract, OA and poly(dA/dT)70. Immunoprecipitations with anti-Chk1 or control sheep antibodies were performed and bound proteins were analysed by blotting for Chk1 with a mouse monoclonal antibody (anti-Chk1) or by autoradiography for Claspin679–1332.

Disruption of the interaction between Claspin and Chk1 by a phosphopeptide

These results, together with prior work in Xenopus [33], indicate that Chk1 recognizes a short, repeated, phosphorylated motif in the CKBD of Claspin. Even though other regions of Claspin and Chk1 may also be involved in their interaction [34], the binding of Claspin to Chk1 might be disrupted by specifically blocking interaction with this domain. By comparison of the human and Xenopus repeat sequences (Figure 5A), we designed a peptide containing phosphoserine to mimic this recognition motif. For comparison, we also synthesized peptides with serine or alanine residues at the site of phosphorylation. To test the effects on the interaction between Claspin and Chk1, the extract was incubated in the presence of radiolabelled Claspin679–1332, OA, poly(dA/dT)70 and 1 μg/μl peptide, and then endogenous Chk1 was immunoprecipitated and the amount of Claspin that co-precipitated was assessed (Figure 5B). When the phosphopeptide was added, there was a marked decrease in the amount of Claspin bound to Chk1. In contrast, Claspin bound to Chk1 to the same extent when the alanine-containing peptide was added as it did in the presence of buffer or an unrelated control peptide. A small decrease in the binding of Claspin to Chk1 was observed when the serine peptide was added, probably because this peptide becomes partially phosphorylated in the extract. These results show that the peptide specifically interferes with the binding of Claspin to Chk1 when phosphorylated and is consistent with the specific binding of this phosphorylated motif in Claspin to Chk1.

Figure 5. A phosphopeptide derived from the Chk1-binding motif of Claspin disrupts binding and inhibits phosphorylation of Chk1.

(A) Chk1-binding motif consensus peptide. Human (residues 908–923 and 937–952) and Xenopus (residues 856–871 and 887–102) repeat Chk1-binding motifs are aligned with a synthetic peptide consensus sequence. The serine residue replaced by an alanine or phosphorylated is indicated by an asterisk. (B) Disruption of the interaction between Claspin and Chk1. The extract was incubated with [35S]Claspin679–1332, OA and poly(dA/dT)70, with further additions of buffer or 1 μg/μl phosphoserine peptide (PS), alanine peptide (AS), serine peptide (SS) or an unrelated control peptide. Proteins precipitating with sheep anti-Chk1 or control antibodies were analysed by immunoblotting with mouse anti-Chk1 or autoradiography. (C) Inhibition of Chk1 phosphorylation. The extract was incubated with OA, poly(dA/dT)70 and different concentrations of PS (top panels), AS (middle panels) or SS (bottom panels). Samples were analysed by Western blotting with anti-Chk1 and α-p345 antibodies.

In addition to its effect on the interaction between Claspin and Chk1, the phosphopeptide inhibited the phosphorylation of Chk1, as judged by an increase in its mobility on SDS/PAGE (Figure 5B), consistent with an essential requirement for the interaction of Claspin with Chk1 for the phosphorylation and activation of Chk1 [35]. Furthermore, the phosphopeptide affected the phosphorylation of Claspin, since a distinct, high-mobility form appeared, indicating that the interaction between Chk1 and Claspin is required in part for the phosphorylation of Claspin.

To characterize the effects of disrupting the interaction between Claspin and Chk1 in more detail, we added increasing amounts of peptides to the extract along with OA and poly(dA/dT)70, and the effects on site-specific phosphorylation of Chk1 were assessed by immunoblotting (Figure 5C). Addition of the phosphoserine peptide significantly decreased the mobility shift in Chk1 and inhibited phosphorylation at Ser345. Inhibition was weak at 10 ng/μl and strong at 100 ng/μl and higher concentrations. In contrast, the non-phosphorylated alanine peptide had no effect on Chk1 phosphorylation even at 2000 ng/μl. Very weak inhibition using the serine-containing peptde (SS) was seen at 1000–2000 ng/μl. Similar results were also obtained on analysing the phosphorylation of Ser317 and Ser296 in Chk1 (results not shown), indicating that phosphorylation of all three sites on Chk1 is dependent on the interaction with Claspin.

The effect of kinase inhibitors on phosphorylation of Claspin and Chk1 indicates distinct Claspin kinases

The human cell-free system is readily amenable to analysis of protein kinase activity by the addition of inhibitors with selectivity for certain kinases. We compared the inhibitor sensitivity of the oligonucleotide-induced phosphorylation of Claspin in human extract with the site-specific phosphorylation of Chk1 (Figure 6). As expected, addition of caffeine, which inhibits ATR and ATM, completely prevented the mobility shift of Chk1 and the phosphorylation of Chk1 at Ser345 and Ser317, sites that are targeted directly by these kinases. In addition, phosphorylation of Ser296 in Chk1 was completely blocked by caffeine. Caffeine also decreased the phosphorylation of Claspin so that the highest upshifted band of the 679–1332 fragment was decreased while a partially upshifted band was maintained. However, oligonucleotide-dependent phosphorylation of the CKBD [expressed as a fusion protein with GST (glutathione S-transferease)], observed as an upshifted doublet on SDS/PAGE, was blocked by caffeine. Taken together, these results show that Claspin is phosphorylated both by a caffeine-inhibited kinase (probably ATR) pathway that targets the CKBD and by a caffeine-insensitive kinase that phosphorylates Claspin elsewhere in the C-terminal half of the protein (residues 679–1332). This caffeine-insensitive kinase is also apparently activated by OA+poly(dA/dT)70.

Figure 6. Effects of kinase inhibitors on Claspin and Chk1 phosphorylation.

The extract was incubated with radiolabelled Claspin679–1332, radiolabelled GST-CKBD, OA+poly(dA/dT)70 and the following additions: staurosporine (staur), UCN01, roscovitine (rosco) and caffeine (upper panels); Gö6976, Ro318220, Bim1, SB203580, rapamycin (Rapa), PD98059 and H89 (lower panels). Proteins were detected by immunoblotting with antibodies raised against Chk1 (anti-Chk1) or specific phosphorylation sites on Chk1 (α-p345, α-p317 and α-p296). Claspin679–1332 and GST–CKBD proteins were detected by autoradiography.

Phosphorylation of Claspin679–1332, but not the CKBD, was partially inhibited by staurosporine and UCN-01 (7-hydroxystaurosporine), both of which also strongly inhibited phosphorylation of Chk1 at Ser296, and the bands detected by antibodies to phospho-Ser345, phospho-Ser317 and total Chk1 were downshifted compared with control. There was some decrease in phosphorylation at Ser345, although there was no apparent decrease in phosphorylation at Ser317. In contrast, the CDK inhibitor roscovitine had no effect on Chk1 or Claspin phosphorylation. These results suggest that staurosporine and UCN01 do not block ATR, but rather inhibit another kinase(s) involved in Claspin and Chk1 phosphorylation that is also stimulated by OA+poly(dA/dT)70.

We also tested a number of other kinase inhibitors for effects on the phosphorylation of Chk1 and Claspin in this system (Figure 6B). H89, rapamycin, PD98059 and SB203580 had no apparent effect on the phosphorylation of either protein. In contrast, Ro318220 and, to a different extent, Bim1 inhibited the phosphorylation of the Chk1 determined by its upshift and by recognition of both phospho-Ser345 and phospho-Ser296, although phosphorylation of Ser317 was not greatly affected. In addition, phosphorylation of Claspin679–1332 was substantially inhibited by Ro318220 and Bim1, even though phosphorylation of CKBD was unaffected. Treatment with Gö6976 resulted in a partial inhibition of the upshift of Chk1 and inhibited the phosphorylation of Ser296, but did not inhibit the phosphorylation of Ser345 and Ser317. Gö6976 also did not affect phosphorylation of the CKBD and did not block phosphorylation of Claspin679–1332, although it did appear to have some effect on the migration of this fragment such that the distinct upper migrating band disappeared. Gö6976 may therefore only partially inhibit the same kinase as Ro318220 and Bim1 or inhibit another kinase that is also not ATR.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we describe a novel human cell-free system for the biochemical dissection of a cell-cycle checkpoint pathway that operates through the Chk1 protein kinase. In this system, we show that site-specific phosphorylation of Chk1 associated with its activation is induced by double-stranded oligonucleotides. We have studied the role of Claspin, a binding partner of Chk1 first identified in Xenopus [28], and its phosphorylation in the regulation of Chk1 phosphorylation. We have shown that the interaction between human Claspin and Chk1 induced by double-stranded oligonucleotides is dependent on a repeated phosphopeptide motif in the CKBD of Claspin. Two phosphorylation sites in the CKBD (Thr916 and Ser945) are required for the interaction of Claspin with Chk1; these residues correspond to the sites phosphorylated in Xenopus Claspin (Ser864 and Ser895) that create motifs for XChk1 binding [33]. In addition, a third repeat sequence containing a potential phosphorylation site (Ser982) in human Claspin may also play a role in the binding of Chk1, although it is clearly less significant.

We have used the consensus Chk1-binding motif to design a phosphopeptide (‘Clasptide’) that acts as a competitor of Chk1 binding to Claspin, thereby showing that site-specific DNA-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 in the human cell-free system requires the interaction of Claspin. This phosphopeptide may be a highly specific inhibitor of Chk1 phosphorylation and activation, since database searches indicate that the motif is not present in any other human protein. Previous work by Dunphy and co-workers has shown that the phosphorylated motif in Xenopus Claspin binds to the kinase domain of Xchk1 and may play a role in the activation of the kinase or act simply as a docking site [34]. Our work suggests that the latter possibility is more likely, since the isolated phosphopeptide is insufficient to activate Chk1, as judged by its autophosphorylation. It remains possible, however, that the duplicated repeated motif structure that is conserved in Claspin molecules has a different effect from a single isolated motif, perhaps by bringing two Chk1 molecules into close proximity and facilitating intermolecular autophosphorylation [34].

In the human cell-free system, dsDNA molecules induce Claspin-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 at three sites detected by specific antibodies in a caffeine-sensitive manner, indicating dependence on ATR/ATM activity. Phosphorylation of Chk1 at Ser345 and Ser317 is probably catalysed directly by ATR [18], although Ser317 may also be phosphorylated by ATM [20]. Phosphorylation of Chk1 at Ser296 is inhibited by staurosporine, UCN01, Gö6976 and Ro318220, whereas phosphorylation at Ser345 and Ser317 is relatively unaffected (with the exception of partial inhibition of Ser345 phosphorylation by staurosporine and Ro318220). UCN01 is a potent Chk1 inhibitor, as is staurosporine, although they also inhibit a number of other protein kinases [41–43]; similarly, BIM1, Ro318220 and Gö6976 can also inhibit Chk1 at the concentrations used, as well as other kinases [43]. This suggests that Ser296 is probably one of the sites autophosphorylated when Chk1 is fully activated [21], despite the sequence surrounding Ser296 (FSKHIQS296NL) being only weakly related to the optimal Chk1-recognition motif (M/I/L/V)-X-(R/K)-X-X-(S/T), where (S/T) is the phosphorylated residue [37].

Although the SG sites in the CKBD of Claspin are phosphorylated in a DNA-dependent manner that is blocked by caffeine, it is not yet clear whether these sites are directly phosphorylated by ATR/ATM or whether an intermediate kinase is involved [33]. ATR/ATM may directly phosphorylate additional sites with SQ motifs within the CKBD, but it is not known what effect, if any, this would have on Chk1 binding. We have provided evidence that Claspin is phosphorylated by other kinases that are probably activated downstream of ATR/ATM, since their action is reversed by caffeine. Phosphorylation of Claspin and Chk1 is not affected by the relatively specific inhibitors SB203580, PD98059 and rapamycin, which inhibit p38, MEK1 and mTOR respectively [43], thereby ruling out a role for these kinases. Phosphorylation of Claspin is, however, sensitive to staurosporine, UCN01, Ro318220 and Bim1. One possibility is that Chk1 itself phosphorylates Claspin in a DNA- and ATR/ATM-dependent manner. Such a mechanism would be consistent with the effect on Claspin phosphorylation of disrupting the interaction between Claspin and Chk1 with the phosphopeptide. Phosphorylation of Claspin by Chk1 could play a role in feedback regulation of Chk1 activity or control of the function of Claspin in DNA replication.

We have also found, however, that phosphorylation of Claspin679–1332 was only partially blocked by caffeine, whereas ATR/ATM-dependent phosphorylation of CKBD and Chk1 was abolished. This suggests that Claspin may be phosphorylated in a DNA-dependent manner by a kinase that is distinct from ATR/ATM or Chk1. More work will be required to determine the kinase(s) responsible, the sites phosphorylated and their effect on Claspin function. Regarding this, Dunphy and co-workers have demonstrated recently that Xenopus Claspin is phosphorylated at two additional sites in the CKBD in response to activation of a DNA replication checkpoint in egg extracts: Thr906, which creates a docking site for Plx1, and the Xenopus Polo-like kinase, which then phosphorylates nearby Ser934. Mutation of either site prevents adaptation to the checkpoint, indicating that this feedback mechanism inactivates Claspin [44]. Phosphorylation of Claspin by multiple kinases at either activating or inhibitory sites could allow different inputs into the temporal and spatial regulation of the Chk1 pathway. The human cell-free system described here offers a potentially valuable model to dissect this pathway, identify the signalling complexes that are involved and determine their regulation by phosphorylation at specific sites.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr J. Hutchins for preparation of GST–Chk1 and antibodies against Chk1, and members of the Clarke group for discussion. This work was supported by a Cancer Research U.K. studentship to C.A.L.C. and a Cancer Research U.K. Senior Research Fellowship to P.R.C. Also, P.R.C. is a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Awardee.

References

- 1.O'Connell M. J., Walworth N. C., Carr A. M. The G2-phase DNA-damage checkpoint. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:296–303. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melo J., Toczyski D. A unified view of the DNA-damage checkpoint. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:237–245. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walworth N., Davey S., Beach D. Fission yeast chk1 protein kinase links the rad checkpoint pathway to cdc2. Nature (London) 1993;363:368–371. doi: 10.1038/363368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furnari B., Rhind N., Russell P. Cdc25 mitotic inducer targeted by chk1 DNA damage checkpoint kinase. Science. 1997;277:1495–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng C. Y., Graves P. R., Thoma R. S., Wu Z., Shaw A. S., Piwnica-Worms H. Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science. 1997;277:1501–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez Y., Wong C., Thoma R. S., Richman R., Wu Z., Piwnica-Worms H., Elledge S. J. Conservation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: linkage of DNA damage to Cdk regulation through Cdc25. Science. 1997;277:1497–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng Y., Forbes K. C., Wu Z., Moreno S., Piwnica-Worms H., Enoch T. Replication checkpoint requires phosphorylation of the phosphatase Cdc25 by Cds1 or Chk1. Nature (London) 1998;395:507–510. doi: 10.1038/26766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumagai A., Guo Z., Emami K. H., Wang S. X., Dunphy W. G. The Xenopus Chk1 protein kinase mediates a caffeine-sensitive pathway of checkpoint control in cell-free extracts. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:1559–1569. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blasina A., de Weyer I. V., Laus M. C., Luyten W. H., Parker A. E., McGowan C. H. A human homologue of the checkpoint kinase Cds1 directly inhibits Cdc25 phosphatase. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furnari B., Blasina A., Boddy M. N., McGowan C. H., Russell P. Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:833–845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Connell M. J., Raleigh J. M., Verkade H. M., Nurse P. Chk1 is a wee1 kinase in the G2 DNA damage checkpoint inhibiting cdc2 by Y15 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1997;16:545–554. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J., Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. Positive regulation of Wee1 by Chk1 and 14-3-3 proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:551–563. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell P. Checkpoints on the road to mitosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:399–402. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mailand N., Falck J., Lukas C., Syljuasen R. G., Welcker M., Bartek J., Lukas J. Rapid destruction of human Cdc25A in response to DNA damage. Science. 2000;288:1425–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorensen C. S., Syljuasen R. G., Falck J., Schroeder T., Ronnstrand L., Khanna K. K., Zhou B. B., Bartek J., Lukas J. Chk1 regulates the S phase checkpoint by coupling the physiological turnover and ionizing radiation-induced accelerated proteolysis of Cdc25A. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:247–258. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Q., Guntuku S., Cui X. S., Matsuoka S., Cortez D., Tamai K., Luo G., Carattini-Rivera S., DeMayo F., Bradley A., et al. Chk1 is an essential kinase that is regulated by ATR and required for the G(2)/M DNA damage checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1448–1459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Girona A., Tanaka K., Chen X. B., Baber B. A., McGowan C. H., Russell P. Serine-345 is required for Rad3-dependent phosphorylation and function of checkpoint kinase Chk1 in fission yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:11289–11294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191557598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao H., Piwnica-Worms H. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:4129–4139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4129-4139.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang K., Pereira E., Maxfield M., Russell B., Goudelock D. M., Sanchez Y. Regulation of Chk1 includes chromatin association and 14-3-3 binding following phosphorylation on Ser-345. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25207–25217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatei M., Sloper K., Sorensen C., Syljuasen R., Falck J., Hobson K., Savage K., Lukas J., Zhou B. B., Bartek J., et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) and NBS1-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 on Ser-317 in response to ionizing radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14806–14811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walworth N. C., Bernards R. rad-dependent response of the chk1-encoded protein kinase at the DNA damage checkpoint. Science. 1996;271:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takai H., Tominaga K., Motoyama N., Minamishima Y. A., Nagahama H., Tsukiyama T., Ikeda K., Nakayama K., Nakanishi M., Nakayama K. I. Aberrant cell cycle checkpoint function and early embryonic death in Chk1(–/–) mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1439–1447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zachos G., Rainey M. D., Gillespie D. A. Chk1-deficient tumour cells are viable but exhibit multiple checkpoint and survival defects. EMBO J. 2003;22:713–723. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam M. H., Liu Q., Elledge S. J., Rosen J. M. Chk1 is haploinsufficient for multiple functions critical to tumor suppression. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou B. B., Anderson H. J., Roberge M. Targeting DNA checkpoint kinases in cancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2003;2:S16–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dasso M., Newport J. W. Completion of DNA replication is monitored by a feedback system that controls the initiation of mitosis in vitro: studies in Xenopus. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1990;61:811–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90191-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kornbluth S., Smythe C., Newport J. W. In vitro cell cycle arrest induced by using artificial DNA templates. Mol. Cell Biol. 1992;12:3216–3223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. Claspin, a novel protein required for the activation of Chk1 during a DNA replication checkpoint response in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:839–849. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Z., Kumagai A., Wang S. X., Dunphy W. G. Requirement for ATR in phosphorylation of Chk1 and cell cycle regulation in response to DNA replication blocks and UV-damaged DNA in Xenopus egg extracts. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2745–2756. doi: 10.1101/gad.842500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hekmat-Nejad M., You Z., Yee M. C., Newport J. W., Cimprich K. A. Xenopus ATR is a replication-dependent chromatin-binding protein required for the DNA replication checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1565–1573. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00855-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumagai A., Kim S. M., Dunphy W. G. Claspin and the activated form of ATR-ATRIP collaborate in the activation of Chk1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49599–49608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J., Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. Claspin, a Chk1-regulatory protein, monitors DNA replication on chromatin independently of RPA, ATR, and Rad17. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:329–340. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. Repeated phosphopeptide motifs in Claspin mediate the regulated binding of Chk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:161–165. doi: 10.1038/ncb921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong S. Y., Kumagai A., Lee J., Dunphy W. G. Phosphorylated Claspin interacts with a phosphate-binding site in the kinase domain of Chk1 during ATR-mediated activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46782–46788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chini C. C., Chen J. Human Claspin is required for replication checkpoint control. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30057–30062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin S. Y., Li K., Stewart G. S., Elledge S. J. Human Claspin works with BRCA1 to both positively and negatively regulate cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:6484–6489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401847101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutchins J. R. A., Hughes M., Clarke P. R. Substrate specificity determinants of the checkpoint protein kinase Chk1. FEBS Lett. 2000;466:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01763-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA ploymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo Z., Dunphy W. G. Response of Xenopus Cds1 in cell-free extracts to DNA templates with double-stranded ends. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:1535–1546. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palermo C., Walworth N. C. Assaying cell cycle checkpoints: activity of the protein kinase Chk1. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005;296:345–354. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-857-9:345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graves P. R., Yu L., Schwarz J. K., Gales J., Sausville E. A., O'Connor P. M., Piwnica-Worms H. The Chk1 protein kinase and the Cdc25C regulatory pathways are targets of the anticancer agent UCN-01. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5600–5605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busby E. C., Leistritz D. F., Abraham R. T., Karnitz L. M., Sarkaria J. N. The radiosensitizing agent 7-hydroxystaurosporine (UCN-01) inhibits the DNA damage checkpoint kinase hChk1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2108–2112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davies S. P., Reddy H., Caivano M., Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem. J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoo H. Y., Kumagai A., Shevchenko A., Dunphy W. G. Adaptation of a DNA replication checkpoint response depends upon inactivation of Claspin by the Polo-like kinase. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2004;117:575–588. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]