Abstract

Background and Objectives

Gastric tube feeding and postpyloric tube feeding are two common forms of enteral nutrition in critically ill patients. This study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of gastric tube feeding with that of postpyloric tube feeding in critically ill patients.

Methods and Study Design

PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library were systematically searched for eligible trials from their inception until March 2023. Relative risks (RRs) or weighted mean differences (WMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to estimate categorical and continuous outcomes using the random-effects model.

Results

Sixteen trials involving 1,329 critically ill patients were selected for the final meta-analysis. Overall, we noted that gastric tube feeding showed no significant difference from post-pyloric tube feeding in mortality (p = 0.891), whereas the risk of pneumonia was significantly increased in patients who received gastric tube feeding (RR: 1.45; p = 0.021). Furthermore, we noted that gastric tube feeding was associated with a shorter time required to start feeding (WMD: −11.05; p = 0.007).

Conclusions

This research revealed that initiating feeding through the gastric tube required less time compared to postpyloric tube feeding. However, it was also associated with a heightened risk of pneumonia among critically ill patients.

Key Words: enteral nutrition, nutritional support, pneumonia, critical illness, systematic review

Introduction

Patients with critical illnesses, including severe acute illnesses such as sepsis, severe trauma, or major surgery, are admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). The characteristics of critical illnesses result in malnutrition and are complicated by other diseases or dysfunctions. Moreover, the generalized inflammatory response could caused by this situation owing to the release of endogenous stress hormones and cytokines.1 Unmet nutritional needs are significantly associated with energy-protein malnutrition and the breakdown of muscle mass.1, 2 Although clinical practice guidelines have addressed the importance of nutritional support for critically ill patients, only 40–60% of patients meet the recommended nutritional goals.3, 4 Studies have already found that malnutrition is associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infection and mortality in critically ill patients and that patients should receive enteral feeding as long as gastrointestinal function permits.5, 6, 7

Enteral nutrition (EN) is considered the preferred means of nutritional support owing to its enhancement of gut immune function, lower cost, and lower risk of septic complications.8, 9 The EN could be provided via various methods, and the two common forms are gastric tube feeding and small intestinal feeding.10, 11 The use of gastric tube feeding showed that slow gastric emptying could increase the residual gastric volume; in addition, the risk of bacterial colonization and aspiration pneumonia increased in critically ill patients. One study found that the use of a postpyloric tube could overcome the shortcomings of gastric tube feeding and was associated with high absorptive capacity.12 The nutritional status of ICU patients is significantly associated with the clinical prognosis. However, whether the use of postpyloric tube feeding was associated with better prognosis for critically illness than gastric tube feeding postpyloric tube feeding remained unclear.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have compared the efficacy and safety of gastric tubes with those of postpyloric tube feeding in critically ill patients.13, 14, 15 Zhang et al.13 identified 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and found that postpyloric tube feeding was associated with higher proportions of estimated energy requirements and reduced residual gastric volume, whereas no significant differences were found between groups for the risk of mortality, new-onset pneumonia, and aspiration. Based on a Cochrane review,14 RCTs were identified. The review indicated that postpyloric tube feeding was linked to a reduced risk of pneumonia and an enhanced delivery of nutrition.14 In another study by Liu et al.,15 involving 41 investigations, post-pyloric tube feeding demonstrated an association with diminished risks of pulmonary aspiration, gastric reflux, pneumonia, or gastrointestinal complications, along with more optimal gastrointestinal nutrition. Nevertheless, it's important to highlight several limitations in prior research, including errors in study inclusion, data extraction, failure to include the latest relevant studies meeting the inclusion criteria, and lack of exploratory analysis results. Therefore, the current study was performed to update the efficacy and safety of gastric tube versus post-pyloric tube feeding in critically ill patients.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were used to guide the study and report this systematic review and meta-analysis.16 Our study was retrospective registered in INPLASY platform and the registered number was INPLASY202380104. This meta-analysis included RCTs designed to compare the effectiveness and safety of gastric tube feeding with postpyloric tube feeding in critically ill patients. The publication language was restricted to English, while the publication status was not restricted. We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases to identify eligible RCTs from their inception until March 2023 using the core search terms, “enteral nutrition” and “critically ill”. Details of the search strategy in each database are provided in the Supplementary Table 1. The websites of ClinicalTrials.gov (US NIH) were searched to identify unpublished trials that had already been completed but had not yet been published. We also manually searched the reference lists of relevant reviews and original articles to identify new eligible trials.

Two reviewers independently performed the literature search and study selection, and inconsistent results were resolved by mutual discussion until a consensus was reached. Studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included: (1) Patients: all patients with critical illness and admitted to the ICU; (2) Intervention and control: gastric tube feeding and postpyloric tube feeding; (3) Outcomes: the primary endpoints were mortality and pneumonia, while the secondary endpoints included abdominal distension, diarrhea, vomiting, bacteremia, constipation, gastrointestinal bleeding, high gastric residual volume, pulmonary aspiration, percentage of total nutrition delivered to the participant, time required to achieve the full nutritional target, time required to start feeding, length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay, and length of mechanical ventilation; and (4) Study design: the study had to have RCT design.

Data collection and quality assessment

The abstracted data were independently analyzed by two reviewers, and the collected information included the first author's name, publication year, country, sample size, mean age, proportion of male participants, disease status, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, intervention, control, enteral feeding protocol, and investigated outcomes. The two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included trials using the risk of bias described by the Cochrane Collaboration, which was based on random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias.17 Any disagreement between the reviewers regarding data collection and quality assessment was resolved by referring to the full text of the article.

Statistical analysis

The investigated outcomes were divided into categorical and continuous outcomes. The categorical outcomes were assessed using events/sample size per group, while the mean, standard deviation, and sample size per group were applied to assess continuous outcomes. The pooled relative risk (RR) or weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated using a random-effects model, which considered the underlying variations across the included trials.18, 19 Heterogeneity among the included trials was assessed using I2 and Q statistics, and significant heterogeneity was defined as I2 ≥ 50.0% or p < 0.10.20, 21 The robustness of the pooled conclusions for mortality and pneumonia was assessed using sensitivity analysis through the sequential removal of a single trial.22 Subgroup analyses for mortality and pneumonia were performed according to country, age, the proportion of male participants, and postpyloric tube, and differences between subgroups were assessed using the interaction t-test.23 Publication bias for mortality and pneumonia was assessed using funnel plots and Egger and Begg tests.24, 25 The reported p value for the pooled effect estimates was two-sided, and the inspection level was 0.05. The analyses in this study were performed using STATA software (version 14.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Literature search and study selection

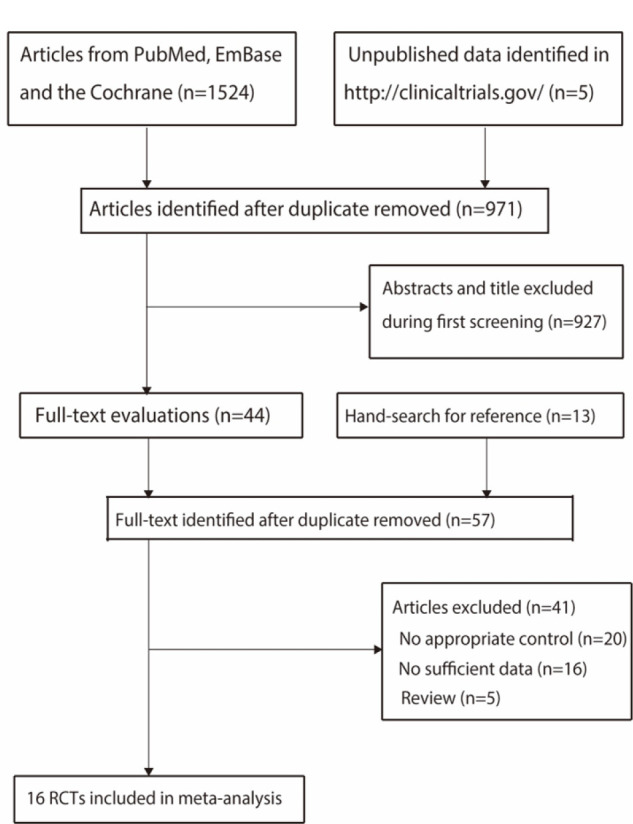

The initial electronic search yielded 1,524 studies, of which 553 articles were removed because of duplicate titles. A total of 927 studies were removed because they reported irrelevant articles, and the remaining 44 studies were retrieved for full-text evaluation. Reviewing the reference lists of relevant studies yielded 13 studies, and detailed evaluations were performed for 57 studies; of these, 38 studies were removed owing to a lack of appropriate controls (n = 17), insufficient data (n = 16), and reviews (n = 5) (Supplementary Table 2). The remaining 16 RCTs were selected for meta-analysis,26-41 and the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Details of the literature search and trial selection processes.

Study characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the identified trials and the patients involved are summarized in Table 1. A total of 1,329 critically ill patients from 16 RCTs were identified, and the sample sizes ranged from 25 to 180. The mean age of the included patients ranged from 34.2 to 82.0 years, and the proportion of male participants ranged from 48.7% to 77.5%. Among the trials included, three employed a duodenal tube, eight utilized a jejunal tube, and the remaining five opted for a smaller intestinal tube for postpyloric tube feeding. The methodological quality of the included trials is presented in the Supplementary Table 3. Overall, the included trials reported a low risk of bias for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases, whereas there was a high risk of bias for the blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment.

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics of included studies and involved patients

| Study | Country | Sample size | Age (years) | Male (%) | Disease status | APACHE | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montecalvo 199226 | USA | 38 (19/19) | 47.7 (44.8/50.5) | 60.5 | Critical patients | II: 16.9 | Gastric | Jejunal |

| Kortbeek 199927 | Canada | 80 (43/37) | 34.2 (34.7/33.6) | 77.5 | Ventilated blunt trauma | II: 18.0 | Gastric | Duodenal |

| Kearns 200028 | USA | 44 (23/21) | 54.4 (49.0/54.0) | 68.2 | Critical patients | II: 21.0 | Gastric | Small intestinal |

| Day 200129 | USA | 25 (11/14) | 56.7 (60.6/53.6) | 56.0 | Neurological disease | III: 47.7 | Gastric | Duodenal |

| Montejo 200230 | Spain | 101 (51/50) | 58.0 (59.0/57.0) | 70.3 | Critical patients | II: 18.0 | Gastric | Jejunal |

| Davies 200231 | Australia | 73 (39/34) | 54.5 (53.5/55.7) | 68.5 | Critical patients | II: 18.2 | Gastric | Jejunal |

| Neumann 200232 | USA | 60 (30/30) | 58.9 (58.1/59.6) | 50.0 | Critical patients | NA | Gastric | Small intestinal |

| Eatock 200533 | Scotland | 49 (27/22) | 60.8 (64.0/58.0) | 53.1 | Severe acute pancreatitis | NA | Gastric | Jejunal |

| White 200934 | Australia | 104 (54/50) | 52.1 (54.0/50.0) | 50.0 | Critical patients | II: 27.1 | Gastric | Small intestinal |

| Hsu 200935 | China | 121 (62/59) | 68.9 (62/59) | 70.2 | Critical patients | II: 20.4 | Gastric | Duodenal |

| Davies 201236 | Australia | 180 (89/91) | 52.5 (54.0/51.0) | 73.9 | Critical patients | II: 20.0 | Gastric | Jejunal |

| Singh 201237 | India | 78 (39/39) | 39.4 (39.1/39.7) | 67.9 | Severe acute pancreatitis | II: 8.3 | Gastric | Jejunal |

| Friedman 201538 | Brazil | 115 (61/54) | 61.4 (60.0/63.0) | 48.7 | Critical patients | II: 22.0 | Gastric | Jejunal |

| Wan 201539 | China | 70 (35/35) | 52.4 (52.0/52.7) | 68.6 | Critical patients | NA | Gastric | Jejunal |

| Taylor 201640 | UK | 50 (25/25) | 52.0 (51.0/53.0) | 76.0 | Critical patients | II: 19.0 | Gastric | Small intestinal |

| Zhu 201841 | China | 141 (71/70) | 82.0 (82.0/82.0) | 62.4 | Critical patients | II: 27.9 | Gastric | Small intestinal |

| Study | Enteral feeding protocol | Follow-up duration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montecalvo 199226 | Began at 25 mL/h/d for the first 24 h and then were increased by 24 mL/h/d until the protein/caloric intake goals were reached | 42.0 days | ||||||

| Kortbeek 199927 | Starting at 25 mL/h and increasing the rate by 25 mL/h every 4 h until the volume required to meet caloric support was achieved | 28.0 days | ||||||

| Kearns 200028 | Infusion was stopped for residuals >150 mL, and once the residual was < 150 mL, feeding resumed | 42.0 days | ||||||

| Day 200129 | The Harris Benedict equation with activity and stress factors were used to calculate the total energy and protein requirement | 10.0 days | ||||||

| Montejo 200230 | Feedings were started in the first 36 h after admission and delivered continuously to achieve half of the estimated caloric needs in 24 h | 16.0 days | ||||||

| Davies 200231 | At a rate of 20 mL/hr and increased by 20 mL/h every 4 hrs until the target nutrition rate was reached | 12.0 days | ||||||

| Neumann 200232 | Starting at 30 mL/h, then advanced to a patient-specific goal rate by 10 mL/h every 6 h | 14.0 days | ||||||

| Eatock 200533 | Rate of 30 mL/h increasing to 100 mL/h over 24-48 h. The caloric target was 2,000 kcal per day | 16.0 days | ||||||

| White 200934 | Enteral feeds were commenced at 40 mL/h. The nasogastric tube was aspirated every 4 h. If the gastric residual was less than 200 mL after 4 h, the rate was increased to the recommended target rate | 5.0 days | ||||||

| Hsu 200935 | starting at 20 mL/h. The rate was increased by 20 mL/h every 4 h until the patient's goal rate was achieved | 34.0 days | ||||||

| Davies 201236 | The initial commencement rate and advancement rate toward the hourly target were determined by each hospital's standard practice, but the aim was to meet estimated energy requirements as soon as possible by following a locally developed evidence-based algorithm | 22.0 days | ||||||

| Singh 201237 | Nutrient goal (25 kcal/kg per day) in 3 to 4 days | 18.0 days | ||||||

| Friedman 201538 | The individual energy needs and the formulation of enteral nutrition were determined by clinical staff (doctors and nutritionists) | 28.0 days | ||||||

| Wan 201539 | Rate of 30 mL/h increasing to 100 mL/h over 24-72 h, the caloric target was set at 25 kcal/kg of ideal bodyweight/day for women and 30 kcal/kg of ideal bodyweight/day for men | 14.0 days | ||||||

| Taylor 201640 | Increased from 40 mL feed/h or current rate to full rate whenever tolerated | 5.0 days | ||||||

| Zhu 201841 | Energy goals were set at 25 kcal per kg of ideal body weight per day, and the protein target was 1.2-2.0 g per kg of ideal body weight per day | 7.0 days | ||||||

APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; NA: not available

Primary endpoints

Thirteen trials reported the effects of gastric tube versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of mortality. There was no significant difference between gastric tube and postpyloric tube feeding for the risk of mortality (RR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.83–1.17; p = 0.891; Figure 2), and no evidence of heterogeneity across included trials was observed (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.872). Sensitivity analysis indicated that the pooled conclusion was stable after the sequential removal of individual trials (Supplementary Figure 1). The results of subgroup analyses were consistent with those of the overall analysis of all subsets (Table 2). No evidence of publication bias for mortality was observed (p value for Egger: 0.087; p value for Begg: 1.000; Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gastric tube feeding versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of mortality.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses for mortality and pneumonia

| Outcomes, factors and subgroup | No of trials | RR and 95%CI | p value | I2 (%) | Q statistic | p value between subgroups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | ||||||

| Country | 0.608 | |||||

| Eastern | 3 | 1.02 (0.79-1.31) | 0.903 | 7.8 | 0.338 | |

| Western | 10 | 0.95 (0.74-1.21) | 0.668 | 0.0 | 0.887 | |

| Age (years) | 0.320 | |||||

| ≥ 55.0 | 5 | 1.03 (0.85-1.25) | 0.761 | 0.0 | 0.633 | |

| < 55.0 | 8 | 0.85 (0.58-1.23) | 0.376 | 0.0 | 0.864 | |

| Male (%) | 1.000 | |||||

| ≥ 70.0 | 5 | 0.99 (0.75-1.30) | 0.916 | 0.0 | 0.954 | |

| < 70.0 | 8 | 0.99 (0.80-1.23) | 0.928 | 0.0 | 0.511 | |

| Postpyloric tube | 0.809 | |||||

| Duodenal | 2 | 0.90 (0.60-1.35) | 0.604 | 0.0 | 0.723 | |

| Jejunal | 7 | 0.96 (0.73-1.25) | 0.765 | 0.0 | 0.890 | |

| Small intestinal | 4 | 0.97 (0.64-1.47) | 0.875 | 23.6 | 0.270 | |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Country | 0.391 | |||||

| Eastern | 4 | 2.07 (0.84-5.06) | 0.113 | 68.8 | 0.022 | |

| Western | 8 | 1.28 (0.94-1.75) | 0.113 | 0.0 | 0.800 | |

| Age (years) | 0.195 | |||||

| ≥ 55.0 | 4 | 1.83 (1.11-3.02) | 0.017 | 25.1 | 0.261 | |

| < 55.0 | 8 | 1.23 (0.82-1.85) | 0.311 | 17.6 | 0.291 | |

| Male (%) | 1.000 | |||||

| ≥ 70.0 | 5 | 1.39 (1.02-1.89) | 0.036 | 0.0 | 0.474 | |

| < 70.0 | 7 | 1.70 (0.79-3.64) | 0.173 | 45.3 | 0.089 | |

| Postpyloric tube | 0.190 | |||||

| Duodenal | 3 | 1.94 (1.16-3.27) | 0.012 | 0.0 | 0.407 | |

| Jejunal | 6 | 1.19 (0.76-1.86) | 0.450 | 27.3 | 0.230 | |

| Small intestinal | 3 | 1.69 (0.87-3.28) | 0.125 | 8.4 | 0.336 |

Twelve trials reported the effect of gastric tube feeding versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of pneumonia. The summary of the results indicated that gastric tube feeding was associated with an increased risk of pneumonia as compared with postpyloric tube feeding (RR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.06–1.99; p = 0.021; Figure 3), and unimportant heterogeneity was observed among included trials (I2 = 22.5%; p = 0.223). Considering the lower limit of 95%CI was approximately 1.00, the pooled conclusion was not stable after the sequential removal of a single trial (Supplementary Figure 3). Subgroup analyses found that gastric tube versus postpyloric tube feeding showed an elevated risk of pneumonia if patients' age was ≥ 55.0 years, the proportion of male participants was ≥ 70.0%, and used duodenal tube feeding as the control group. No other significant difference was observed between gastric tube versus postpyloric tube feeding for the risk of pneumonia in subgroup analyses (Table 2). There was no significant publication bias for pneumonia (p value for Egger: 0.059; p value for Begg: 0.150; Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Gastric tube feeding versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of pneumonia.

Secondary endpoints

The breakdown of the number of trials reporting the effects of gastric tube versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of abdominal distension, diarrhea, and vomiting was 5, 11, and 7 trials, respectively (Figure 4). Overall, gastric tube feeding has no significant effects on the risk of abdominal distension (RR: 1.36; 95% CI: 0.99–1.88; p = 0.061), diarrhea (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.74–1.18; p = 0.571), and vomiting (RR: 1.34; 95% CI: 0.85–2.12; p = 0.210). There was no evidence of heterogeneity for abdominal distension (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.478) or diarrhea (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.912), whereas significant heterogeneity was observed for vomiting (I2 = 47.3%; p = 0.077).

Figure 4.

Gastric tube feeding versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of abdominal distension, diarrhea, and vomiting.

The breakdown of the number of trials reporting the effects of gastric tube versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of bacteremia, constipation, gastrointestinal bleeding, high gastric residual volume, and pulmonary aspiration was three, two, four, two, and four trials, respectively (Figure 5). There were no significant differences between gastric tube and postpyloric tube feeding for the risk of bacteremia (RR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.45–1.97; p = 0.871), constipation (RR: 1.39; 95% CI: 0.70–2.78; p = 0.349), gastrointestinal bleeding (RR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.33–1.36; p = 0.269), high gastric residual volume (RR: 3.77; 95% CI: 0.07–215.21; p = 0.520), and pulmonary aspiration (RR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.44–1.88; p = 0.792). No significant heterogeneity was observed for bacteremia (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.636), constipation (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.946), gastrointestinal bleeding (I2 = 36.9%; p = 0.190), and pulmonary aspiration (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.498), while substantial heterogeneity was observed for high gastric residual volume (I2 = 92.1%; p <0.001).

Figure 5.

Gastric tube feeding versus postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of bacteremia, constipation, gastrointestinal bleeding, high gastric residual volume, and pulmonary aspiration.

The breakdown of the number of trials reporting the effects of gastric tube versus postpyloric tube feeding on the percentage of total nutrition delivered to the participant, time required to achieve the full nutritional target, and time required to start feeding was six, four, and five trials, respectively (Figure 6). There were no significant differences between gastric tube and postpyloric tube feeding for a percentage of total nutrition delivered to the participant (WMD: −7.62; 95% CI: −15.49–0.26; p = 0.058), and time required to achieve the full nutritional target (WMD: −1.28; 95% CI: −6.51–3.95; p = 0.631), while gastric tube feeding was associated with shorter time required to start feeding as compared with postpyloric tube feeding (WMD: −11.05; 95% CI: −19.05 to −3.05; p = 0.007). We noted substantial heterogeneity across the included trials in the percentage of total nutrition delivered to the participants (I2 = 91.5%; p <0.001), the time required to achieve the full nutritional target (I2 = 85.1%; p <0.001), and the time required to start feeding (I2 = 90.0%; p <0.001).

Figure 6.

Gastric tube feeding versus postpyloric tube feeding on percentage of total nutrition delivered to the participant, time required to achieve the full nutritional target, and time required to start feeding.

The breakdown of the number of trials reporting the effects of gastric tube versus postpyloric tube feeding on the length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay, and length of mechanical ventilation was 10, 7, and 8 trials, respectively (Figure 7). No significant differences between gastric tube and postpyloric tube feeding for length of ICU stay (WMD: 0.66; 95% CI: −0.96–2.28; p = 0.423), length of hospital stay (WMD: 1.63; 95% CI: −0.65–3.91; p = 0.162), and length of mechanical ventilation (WMD: 1.01; 95% CI: −0.89–2.91; p = 0.296) were observed.

Figure 7.

Gastric tube feeding versus postpyloric tube feeding on length of ICU stay, length of hospital stays, and length of mechanical ventilation. ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

The use of an enteral route for EN can reduce gastric motility, which is responsible for limited caloric intake and is associated with an increased risk of aspiration pneumonia. Postpyloric tube feeding, which delivers feed to the duodenum or jejunum, could overcome these shortcomings. This comprehensive, quantitative study was performed to compare the efficacy and safety of gastric tubes with postpyloric tube feeding for critically ill patients, and a total of 1,329 critically ill patients across a broad range of patients' characteristics, especially disease status, from 16 RCTs were included. This study found that gastric tube feeding although, allowing for an earlier start time for feeding, significantly increased the risk of pneumonia compared with post-pyloric tube feeding, whereas there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of mortality, abdominal distension, diarrhea, vomiting, bacteremia, constipation, gastrointestinal bleeding, high gastric residual volume, pulmonary aspiration, percentage of total nutrition delivered to the participant, time required to achieve the full nutritional target, length of ICU stay, length of hospital stay, and length of mechanical ventilation.

Our study reported similar effects of gastric tube and postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of mortality, which is consistent with prior meta-analyses.13, 14, 15 Moreover, the results of the sensitivity and subgroup analyses indicated no significant difference between gastric and postpyloric tube feeding on the risk of mortality, and all included trials reported similar conclusions. The potential reason for this could be that these trials were designed with nutritional and safety outcomes as the primary outcomes, and the sample size was not sufficient to detect potential differences in the risk of mortality between groups.

Our study found that gastric tube feeding was associated with an increased risk of pneumonia compared to postpyloric tube feeding, which was consistent with previous meta-analyses.14, 15 Studies have illustrated that inhibited gastrointestinal motility, reduced gastric emptying, a pressure drop at the gastroesophageal junction, and abnormal esophageal motility are significantly associated with the progression of pneumonia.42, 43 The end of the tube in postpyloric tube feeding was placed post-pylorus, which was associated with reduced gastric residual volume and inhibition of gastrointestinal peristalsis. Moreover, postpyloric tube feeding can prevent nutrients from flowing back into the stomach, thereby reducing the risk of aspiration. Furthermore, subgroup analyses found an increased risk of pneumonia in patients receiving gastric tube feeding, when patients' age was ≥ 55.0 years, the proportion of male participants was ≥ 70.0%, and used duodenal tube feeding as control. These results suggest that differences are mainly observed in patients at high risk for pneumonia.

Our study did not find significant differences between gastric tube and postpyloric tube feeding for the risk of gastrointestinal complications, which is inconsistent with a previous study.15 The potential reasons for these differences could be explained by the following: (1) the incidence of gastrointestinal complications could be affected by the dosage, type, and dropping rate of the nutrient solution; (2) the disease status varied between gastric tube and postpyloric tube feeding and could be affected by the progression of gastrointestinal complications; and (3) the incidence of most specific gastrointestinal complications was lower, and a smaller number of trials reported these outcomes; thus, the power was not sufficient to detect potential differences between the groups. In addition, although the use of postpyloric tube feeding could provide more nutrition and reduce the risk of complications, there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of the lengths of ICU stay, hospital stay, and mechanical ventilation.

This study has several limitations. First, most of the included trials reported a high risk of bias for blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment. Second, substantial heterogeneity was observed for several outcomes, particularly the continuous outcomes. Third, the severity of critically illness and disease status differed across the included trials, which could have affected the prognosis of critically ill patients. Fourth, meta-analyses based on published articles have inherent limitations, including inevitable publication bias and restricted detailed analyses.

In conclusions, our study found that gastric tube feeding required a shorter time to start feeding than postpyloric tube feeding but related to a significantly increased risk of pneumonia in critically ill patients. Therefore, post-pyloric tube feeding should be applied for critically ill patients to prevent the risk of pneumonia in clinical practice.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

This study was supported by Fengxian District Science and Technology Commission Social Science and Technology Development Fund Project (Project Number: Fengke 20201303).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Fengxian District Science and Technology Commission Social Science and Technology Development Fund Project (Project Number: Fengke 20201303).

References

- 1.Quirk J. Malnutrition in critically ill patients in intensive care units. Br J Nurs. 2000;9:537–541. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2000.9.9.6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cederholm T, Bosaeus I, Barazzoni R, Bauer J, Gossum A Van, et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition - An ESPEN Consensus Statement. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wischmeyer PE. Overcoming challenges to enteral nutrition delivery in critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021;27:169–176. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heyland DK, Schroter-Noppe D, Drover JW, Jain M, Keefe L, Dhaliwal R, Day A. Nutrition support in the critical care setting: current practice in canadian ICUs-opportunities for improvement? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27:74–83. doi: 10.1177/014860710302700174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Cahill N, Wang M, Day A, Duggan CP, Heyland DK. Nutritional practices and their relationship to clinical outcomes in critically ill children–an international multicenter cohort study*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2204–2211. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e18a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dvir D, Cohen J, Singer P. Computerized energy balance and complications in critically ill patients: an observational study. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heyland DK, Stephens KE, Day AG, McClave SA. The success of enteral nutrition and ICU-acquired infections: a multicenter observational study. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40:159–211. doi: 10.1177/0148607115621863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elke G, van Zanten AR, Lemieux M, McCall M, Jeejeebhoy KN, Kott M, Jiang X, Day AG, Heyland DK. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2016;20:117–117. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1298-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland DK, Drover JW, Dhaliwal R, Greenwood J. Optimizing the benefits and minimizing the risks of enteral nutrition in the critically ill: role of small bowel feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:S51–S55. doi: 10.1177/014860710202600608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiyong J, Tiancha H, Huiqin W, Jingfen J. Effect of gastric versus post-pyloric feeding on the incidence of pneumonia in critically ill patients: observations from traditional and Bayesian random-effects meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heyland DK, Drover JW, MacDonald S, Novak F, Lam M. Effect of postpyloric feeding on gastroesophageal regurgitation and pulmonary microaspiration: results of a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1495–1501. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Xu X, Ding J, Ni H. Comparison of postpyloric tube feeding and gastric tube feeding in intensive care unit patients: a meta-analysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28:371–380. doi: 10.1177/0884533613485987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alkhawaja S, Martin C, Butler RJ, Gwadry-Sridhar F. Post-pyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008875.pub2. Cd008875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang B, Wang J, Sun L, Xiao Q. Gastric-tube versus post-pyloric feeding in critical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of pulmonary aspiration- and nutrition-related outcomes. Eur J. Clin Nutr. 2021;75:1337–1348. doi: 10.1038/s41430-021-00860-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panic N, Leoncini E, de Belvis G, Ricciardi W, Boccia S. Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83138–e83138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) Cochrane Collaboration. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ades AE, Lu G, Higgins JP. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:646–654. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. 1st edn. 2008. Analyzing data and undertaking meta-analyses. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobias A. Assessing the influence of a single study in meta-analysis. Stata Tech Bull. 1999;47:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. Bmj. 2003;326:219–219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montecalvo MA, Steger KA, Farber HW, Smith BF, Dennis RC, Fitzpatrick GF, Pollack SD, Korsberg TZ, Birkett DH, Hirsch EF. Nutritional outcome and pneumonia in critical care patients randomized to gastric versus jejunal tube feedings. The Critical Care Research Team. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:1377–1387. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kortbeek JB, Haigh PI, Doig C. Duodenal versus gastric feeding in ventilated blunt trauma patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma. 1999;46:992–996. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199906000-00002. discussion 996-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kearns PJ, Chin D, Mueller L, Wallace K, Jensen WA, Kirsch CM. The incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia and success in nutrient delivery with gastric versus small intestinal feeding: a randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1742–1746. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day L, Stotts NA, Frankfurt A, Stralovich-Romani A, Volz M, Muwaswes M, Fukuoka Y, O'Leary-Kelley C. Gastric versus duodenal feeding in patients with neurological disease: a pilot study. J Neurosci Nurs. 2001;33:148–149. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montejo JC, Grau T, Acosta J, Ruiz-Santana S, Planas M, García-De-Lorenzo A, et al. Multicenter, prospective, randomized, single-blind study comparing the efficacy and gastrointestinal complications of early jejunal feeding with early gastric feeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:796–800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies AR, Froomes PR, French CJ, Bellomo R, Gutteridge GA, Nyulasi I, Walker R, Sewell RB. Randomized comparison of nasojejunal and nasogastric feeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:586–590. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann DA, DeLegge MH. Gastric versus small-bowel tube feeding in the intensive care unit: a prospective comparison of efficacy. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1436–1438. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eatock FC, Chong P, Menezes N, Murray L, McKay CJ, Carter CR, Imrie CW. A randomized study of early nasogastric versus nasojejunal feeding in severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:432–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White H, Sosnowski K, Tran K, Reeves A, Jones M. A randomised controlled comparison of early post-pyloric versus early gastric feeding to meet nutritional targets in ventilated intensive care patients. Crit Care. 2009;13:R187–R187. doi: 10.1186/cc8181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu CW, Sun SF, Lin SL, Kang SP, Chu KA, Lin CH, Huang HH. Duodenal versus gastric feeding in medical intensive care unit patients: a prospective, randomized, clinical study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1866–1872. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819ffcda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies AR, Morrison SS, Bailey MJ, Bellomo R, Cooper DJ, Doig GS, Finfer SR, Heyland DK. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial comparing early nasojejunal with nasogastric nutrition in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2342–2348. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318255d87e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh N, Sharma B, Sharma M, Sachdev V, Bhardwaj P, Mani K, Joshi YK, Saraya A. Evaluation of early enteral feeding through nasogastric and nasojejunal tube in severe acute pancreatitis: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Pancreas. 2012;41:153–159. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318221c4a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman G, Flávia Couto CL, Becker M. Randomized study to compare nasojejunal with nasogastric nutrition in critically ill patients without prior evidence of altered gastric emptying. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015;19:71–75. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.151013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wan B, Fu H, Yin J. Early jejunal feeding by bedside placement of a nasointestinal tube significantly improves nutritional status and reduces complications in critically ill patients versus enteral nutrition by a nasogastric tube. Asia Pac J. Clin Nutr. 2015;24:51–57. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.1.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor SJ, Allan K, McWilliam H, Manara A, Brown J, Greenwood R, Toher D. A randomised controlled feasibility and proof-of-concept trial in delayed gastric emptying when metoclopramide fails: We should revisit nasointestinal feeding versus dual prokinetic treatment: Achieving goal nutrition in critical illness and delayed gastric emptying: Trial of nasointestinal feeding versus nasogastric feeding plus prokinetics. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2016;14:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu Y, Yin H, Zhang R, Ye X, Wei J. Gastric versus postpyloric enteral nutrition in elderly patients (age ≥ 75 years) on mechanical ventilation: a single-center randomized trial. Crit Care. 2018;22:170–170. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2092-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kharrazian D. Traumatic Brain Injury and the Effect on the Brain-Gut Axis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2015;21:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Houghton LA, Lee AS, Badri H, DeVault KR, Smith JA. Respiratory disease and the oesophagus: reflux, reflexes and microaspiration. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:445–460. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data