Abstract

Background:

The theory of executive attention (Fuster, 2015) suggests considerable plasticity regarding when specific neurocognitive operations are recruited to bring executive tasks to fruition.

Objective:

We tested the hypothesis that differing neurocognitive operations are recruited upon the initiation of a response, but that other distinct neurocognitive operations are recruited towards the middle or end of a response.

Methods:

The Backward Digit Span Test (BDST) was administered to 58 memory clinic patients (MCI, n = 22; no-MCI, n = 36). Latency to generate all correct 5-span responses was obtained. Statistical analyses found that optimal group classification was achieved using the first and third digit backward. First and third response latencies were analyzed in relation to verbal working memory (WM), visual WM, processing speed, visuospatial operations, naming/lexical access, and verbal episodic memory tests.

Results:

For the first response, slower latencies were associated with better performance in relation to verbal WM and visuospatial test performance. For the third response, faster latencies were associated with better processing speed and visuospatial test performance.

Conclusion:

Consistent with the theory of executive attention, these data show that the neurocognitive operations underlying successful executive test performance are not monolithic but can be quite nuanced with differing neurocognitive operations associated with specific time epochs. Results support the efficacy of obtaining time-based latency parameters to help disambiguate successful executive neurocognitive operations in memory clinic patients.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Boston Process Approach, digit span, executive control, intra-component latency, mild cognitive impairment, temporal organization

INTRODUCTION

Models exploring the nature of executive control often revolve around specific top-down and bottom-up constructs. Multiple theories have been developed to delineate the necessary processes for accurate and efficient completion of executive control systems. These theories often include larger systems responsible for organizing and executing responses in their correct serial order; and a sub-ordinate, inhibitory system that minimizes errors. For example, Diamond [1] hypothesized the existence of three cognitive constructs that make up an executive control system. Working memory holds pertinent information in mind, i.e., information that may not be present, to perform a requested or necessary mental manipulation; inhibitory control guards against emergence of errors and the capacity not to be derailed from the task at hand; and cognitive flexibility alters a pre-determined or already established mental set for a desire response. Miyake and colleagues [2], using statistical modeling techniques, also support the existence of a core group of executive constructs including information updating and monitoring thought to be related to the ability to monitor incoming information for task relevance and revise as may be required; mental set shifting related to the ability to shift back and forth between tasks or mental sets; and inhibition of prepotent responses that acts to inhibit behavior that might derail test performance.

Other theories of executive abilities are devoid of distinct mechanisms [3, 4]. For example, embedded-component models of executive abilities [3, 4] suggest dynamic interrelationships between short-term memory (STM); a capacity limited construct where information that needs to be retained or mentally manipulated is maintained, and long-term memory (LTM), a mechanism believed to reside outside of STM where the attributes of what is to be retained resides.

An influential model of working memory was suggested by Baddeley and Hitch [5]. This model was developed, in part, to address the notion that existing models of short-term memory did not necessarily account for the fact that mental operations could be successfully completed independent of the influence of LTM; and that performance on dual-task paradigms were often equal to performance on single task paradigms when the tasks under consideration involved different domains of information, i.e., verbal and visuospatial content. Hence the creation of the two buffer mechanisms labeled the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad that were under the control of a superordinate central executive. The multicomponent model of Baddeley and Hitch [5] elegantly proposed mechanisms that could account for the buffering and coordinating operations needed to bring to fruition complex tasks [6].

Another important model of executive control is the theory of executive attention suggested by Fuster [7, 8]. In seminal research, Fuster and Alexander [9] observed persistent neural activity during delayed response tasks where monkeys were required to maintain necessary information that was no longer present but was required for successful task performance. As a result, these researchers hypothesized the presence of a temporal gradient, or time necessary to recruit the requisite neurocognitive resources for successful task completion. Subordinate to the construct of the temporal gradient is the existence of three separate, but highly integrated and overlapping cognitive constructs – working memory, preparatory set, and inhibitory control [7, 8]. Working memory operates to establish an initial mental set, directing attention toward the attributes and representation of the task at hand. Specifically, working memory [10, 11] temporally and retrospectively reclaims content from recent and past experiences activating pre-existing networks of long-term, task-related memoranda. Preparatory set sustains an initially established mental set. Thus, preparatory set operates to prepare neural resources for expected actions and outcomes contingent on previous events and information from working memory [7, 8, 11]. In this context working memory is attention directed to past experience (e.g., “what was I asked to do”), while preparatory set is attention directed to an intended future outcome (e.g., “how do I do it”). Therefore, the constructs of working memory and preparatory set can be viewed as a continuum that first recruit then deploy necessary neurocognitive resources to bring tasks to completion. Finally, inhibitory control refers to the ability to prevent and/ or suppress irrelevant internal and external inputs that can derail or interfere with task-relevant behaviors to produce a goal-directed response [7, 8, 10]. Inhibitory control is, therefore, an exclusionary mechanism that prevents the emergence of errors such as perseveration.

Support for the existence of these constructs was initially obtained in research with primates where delay responding research strategies were used. In this research, different but overlapping neurocognitive operations associated with specific groups of neurons were shown to be recruited at different epochs, or periods of time. For example, Quintana and Fuster [12] found that so-called ‘memory unit’ cells were active early in the test trial and may be associated with the construct of working memory or test contingencies involved in establishing mental set, whereas so-called ‘set cells’ where active later in the test trial and were thought to be related to preparatory set or the ability to sustain mental set to bring the task to fruition.

Similar results were reported by Wang and colleagues [13]. In this research neuronal activity recorded from frontal regions during the initial delay period was associated with the initial encoding of task-related information whereas late-delay activity appeared to be related to modality-independent activity or the anticipation of a behavioral outcome. The dissociation between early versus delay neuronal activity suggests that different neurocognitive operations were recruited within different time epochs in the context of correct responding.

Functional imaging paradigms have also demonstrated support for Fuster’s model of executive attention [8, pp 297–300; 14, 15]. Using either visual, spatial, or auditory stimuli, posterior cortical regions and the lateral prefrontal area and adjacent regions were activated early in the test trial. During the mid-delay epoch, there was persistent prefrontal activity along with activity in tertiary parietal or temporal brain regions depending on the type of stimuli displayed. During the late-delay period, the location of activity changed to premotor and adjacent brain regions. Finally, when a response was near or had begun, pre-motor, motor and other cortical regions were activated. This activity suggests that ‘working memory’ is particularly active during early and mid-delay test epochs, where resources needed to respond as directed are marshaled, whereas ‘preparatory set’ is active during latter test epochs after the necessary resources have been recruited and just before an actual response is made. There are many advantages to using Fuster’s model, including the extensive research that has validated its utility in understanding executive control.

With advances in computing technology, traditional paper and pencil neuropsychological tests have been engineered into a platform that can reliably capture a variety of time-based parameters beyond total time to completion, including a wide number of intra-component latencies, or the time necessary to initiate and complete subcomponents of the task at hand [16, 17]. As a function of these newer digital technologies, there is an opportunity to understand the executive control constructs discussed above in older adults, especially in the context of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias, where the networks that underlie executive abilities become disrupted due to AD and other neuropathology [18].

A recent example of this type of research has been provided by Emrani and colleagues [19]. In this research, memory clinic patients with and without MCI were assessed with a digitally administered pointing span test, where patients were asked to reorder numbers from lowest to highest [20]. Using only correct test trials, groups were dissociated based on the latencies to generate selected individual correct responses. Moreover, Emrani and colleagues [19] found that the latency to generate the first response was associated with tests assessing verbal episodic memory and naming/lexical access, suggesting that newly requested tasks rely upon previously acquired lexical and memory-based information. By contrast, the latency to generate the last response was associated with verbal working memory performance, suggesting the recruitment of cognitive domains that allow for mental manipulation information as requested. Together, results suggest that different neurocognitive constructs are associated with different epochs in the context of correct test performance.

Another neuropsychological test that was recently digitized was the Backward Digit Span test (BDST), originally described by Lamar and colleagues [21, 22]. On this test patients are asked to repeat numbers backwards (3, 4, and 5-span trials) for a total of 21 trials. In this version of the digit span backwards test, there is no discontinuation, i.e., all patients were administered all 21 test trials. Using this digitized version to examine differences between memory clinic patients with and without MCI, Emrani and colleagues [23] found different patterns of latency performance for correct 5-span test trials. Specifically, patients who were non-MCI exhibited slower latencies both in the beginning and towards the end of the test trial, whereas patients with MCI exhibited slower latencies in the middle of the test trial.

In the context of Fuster’s theory of executive attention, these authors suggest that slower latencies early in the test trial allows for more efficient working memory ability such that these patients may have been better able to recruit the necessary cognitive resources to produce a correct response. By contrast, the slower latency generated during the middle of the test trial produced by the MCI group could suggest less efficient working memory put forth early in the test trial which then requires a regrouping midway through the test demands. Finally, the slower latency toward the end of the test trial produced by the non-MCI group could suggest more efficient preparatory set or a better capacity to maintain the necessary mental set for a correct response. These results may also mirror the temporal gradient needed for successful completion of a task.

Although Emrani and colleagues [23] where able to document between-group differences in response latencies, analyses examining how backward digit span response latencies may be related to underlying neurocognitive abilities were not conducted. Thus, using the same memory clinic patients described by Emrani and colleagues [23], we sought to build upon the prior research using Fuster’s model to test the hypothesis that, consistent with the prior pointing span research described by Emrani and colleagues [19], specific latencies (i.e., specific time epochs to generate a correct response) will be associated with different underlying neurocognitive abilities.

METHODS

Participants

Patients (n = 58) were recruited from the New Jersey Institute for Successful Aging Memory Assessment Program (MAP). All patients came to the MAP program because of a subjective complaint of cognitive decline. All data reported below were gathered during a single test session and all patients underwent a neuropsychological evaluation, were examined by a social worker, a board-certified geriatric psychiatrist, and were studied with brain MRI scans and blood serum tests. Patients diagnosed with MCI presented with evidence of cognitive impairment relative to age and education, preservation of general functional abilities, and the absence of dementia. Exclusion criteria included a history of head injury, substance abuse, and major psychiatric disorders including major depression, epilepsy, B12, folate, or thyroid deficiency. This study was approved by the Rowan University institutional review board with consent obtained consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Neuropsychological protocol

Tests used for group classification.

The neuropsychological protocol used to characterize MCI subtypes assessed three domains of cognition: executive control, naming/ lexical access, and verbal episodic memory (Table 1). From this protocol, nine scores, three from each neurocognitive domain, were used to classify MCI subtypes as described below. All test scores were expressed as z-scores derived from previously published normative data. The rationale for using the protocol described below was based on prior research showing that these tests are able to operationally define key neurocognitive constructs that differentiate between MCI subtypes [24–28].

Table 1.

Neuropsychological Parameters Used for Diagnosis and Classification

| Executive Function | Language/Lexical Access | Episodic Memory |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Domain | Domain |

| WMS – Mental Control | 60-item Boston Naming | CVLT (short form) – |

| Subtest (Boston revision) | Test | Immediate Free Recall |

| Letter Fluency (‘FAS’) | ‘animal’ Fluency | CVLT (short form) |

| Delayed Free Recall | ||

| Trail Making Test Part B | WAIS-III Similarities | CVLT (short form) – |

| Subtest | Delayed Recognition |

CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-3rd edition

Additional neuropsychological tests.

Separate from the neuropsychological tests administered for patient classification, all patients were administered additional neuropsychological tests as described below. Visual working memory abilities were assessed using the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS)-Symbol Span Test [29] and the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML) Symbolic Working Memory Test [20]. Processing speed was assessed with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III Digit Symbol Test [30]. Visuospatial/visuoconstructional operations were assessed with the Judgment of Line Orientation Test [31, 32] and the Bender Gestalt-II Figure Copy Test [33]. Supplementary Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for all tests used in the current research.

Neuropsychological index scores.

Listed below are six neuropsychological index scores calculated by averaging the z-scores for each test. The composition of some of the index scores listed below is supported by previous research using cluster analysis and latent class analysis [24, 27, 34, 35].

Verbal Working Memory. Boston Revision of the Wechsler Memory Scale Mental Control subtest [36]; letter fluency test (letters ‘FAS’; [37, 38]).

Visual Working Memory. Wechsler Memory Scale-Symbol Span subtest [29]; the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning Symbolic Working Memory Test [20].

Processing Speed. Trail Making Test-Part B [37, 39]; the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Digit Symbol subtest [30].

Naming/Lexical Access. The Boston Naming Test [37, 40]; the ‘animal’ fluency test [37]; WAIS-III Similarities subtest [30].

Visuospatial Operations. The Judgment of Line Orientation Test [31–33].

Verbal Episodic Memory. California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT)- short form delayed free recall; delayed recognition discriminability index [41].

Patient groups

Mild cognitive impairment.

Jak/Bondi criteria [42–46] was used to classify patients into MCI subtypes. Single domain MCI was diagnosed when participants scored > 1.0 standard deviation (sd) below normative expectations on two or more of three measures within any single cognitive domain. Mixed MCI was diagnosed when participants scored > 1.0 sd below normative expectations on two of three measures within two or more cognitive domains. Eight patients were classified with amnestic MCI and 14 patients were classified with a combined mixed/dysexecutive MCI syndrome. In the current research, all MCI patients were aggregated into a single MCI group.

Memory clinic/No-MCI patients.

Some memory clinic patients did not meet Jak/Bondi criteria [42, 46] for MCI. Although all memory clinic patients presented with subjective concerns regarding declining cognitive abilities, all of these patients scored above 1 sd above all nine neuropsychological parameters or scored 1sd below the mean on no more than one neuropsychological parameter from each of the three domains that were assessed. These memory clinic patients were labeled as memory clinic/no-MCI.

The Backwards Digit Span Test

Construction of the Backward Digit Span Test.

The BDST is comprised of seven trials of 3-, 4-, and 5-digit span lengths for a total of 21 trials [21, 22]. The 4- and 5-span trials were constructed so that contiguous numbers were placed in strategic positions. For example, in 4-span trials contiguous numbers were placed in either the first- and third-positions or second- and fourth-digit positions (e.g., 5269 or 1493). For 5-span trials, contiguous numbers were placed in the middle three-digit positions (e.g., 16579). This procedure cannot be used for 3-span test trials because of primacy and recency effects. The BDST was administered using Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale administration procedures except that all 21 test trials were administered regardless of errors that were made. Only the seven 5-span trials were used in the current research.

Percent of BDST correct ANY-order.

This score reflected the sum total of every digit correctly recalled regardless of serial position divided by the total possible correct multiplied by 100, [(total # correct digits ANYORDER)/ (total possible correct)]×100. By eliminating the importance of serial position during digit recall despite instruction, this variable is believed to reflect less complex aspects of working memory characterized mainly by short-term or immediate storage and rehearsal mechanisms.

Percent of BDST correct serial order.

This score reflects the total number of digits correctly recalled in accurate serial position divided by the total possible correct multiplied by 100, [(total # correct digits SERIALORDER)/ (total possible correct)]×100. This variable is believed to measure the more executively demanding aspects of working memory associated with mental manipulation such as disengagement and temporal re-ordering. Supplementary Table 2 lists descriptive data on this test.

iPad administration of the Backward Digit Span Test.

In the present study, data were collected in real-time via an iPad-administration of the BDST with voice recognition. In the current research the iPad verbally speaks numbers and records the patient’s spoken response, i.e., repeating numbers backwards. The utility of recording responses on the iPad includes the ability to measure total time to completion for all trials, as well as the time to generate intra-component latencies or the time needed to produce each individual response (i.e., time zero to first response, time from the end of the first response to the beginning of the second response etc.), across each serial order position for each span. Average total time was calculated by dividing time to completion for all correct trials divided by the number of correct trials. Time latencies were computed using speech recognition software. The patient’s response was recorded using the iPad speech recording capability and the recorded response was uploaded to a robust third-party speech recognition service. In addition to recognizing the components within the patient’s response, namely, the digits uttered, this service also provided intra-digit latencies.

Outcome variables and statistical analyses

Using the same set of data, and consistent with Emrani and colleagues [19], only correct trials were analyzed, i.e., both groups scored 100% correct for repeating digits backwards. Incorrect trials were not analyzed in this research. The current research sought to differentiate between groups based solely on response latency. Variables were screened for outliers and for departures from normality through examination of skewness and kurtosis and visual inspection of frequency distributions. The data obtained on all neuropsychological tests were normality distributed and no outliers were obtained. On the BDST positions 1 and 2 each had two responses that were considered to be outliers (scores differed from the next score by a z-score of more than 3.2sd). For these responses we assigned the next closest value. To address non-normality issues, where indicated, we assigned outliers a lower weight, i.e., the data point was modified to the next closest value in the set (see Dixon [47]).

Backward Digit Span Test-latency outcome variables.

Backward Digit Span Test time-based variables of interest included the latency to generate the first digit backward. Prior research [19, 23] found that in all patient groups, this latency was, by far the slowest, suggesting that initial responding could be associated with considerable underlying neurocognitive activity. Because of our modest sample size, and to guard against statistical errors with the number of individual latencies available for analysis (i.e., 5 latency measures for each trial), a preliminary stepwise logistic nominal regression analysis was conducted for latencies 2–5 to assess the capacity of each latency to classify patients into their respective groups.

Statistical analyses.

Pearson Product-Moment Correlations were obtained using the entire sample between selected latencies and the neuropsychological index scores described above.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Demographic and clinical information can be found in Table 2. Prior analyses [19] revealed no between-group differences for age, education, the Geriatric Depression Scale [48], the Wide Range Achievement Test Reading-IV subtest [49] or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [50]. The MCI group obtained a lower score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (t [56] = 2.18, p < 0.035; MMSE [51]).

Table 2.

Memory Clinic Sample: Demographic and Clinical Information

| Memory Clinic | Memory Clinic MCI | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No MCI (n = 38) | (n = 20) | ||

| Age | 73.19 (7.15) | 72.45 (5.62) | ns |

| Education | 15.81 (2.45) | 15.23 (2.60) | ns |

| MMSE | 28.61 (1.48) | 27.68 (1.73) | MCI<no-MCI; p < 0.035 |

| WRAT-IV Reading subtest | 115.61 (14.71) | 109.50 (17.06) | ns |

| IADL abilities | 15.83 (2.09) | 14.86 (2.61) | ns |

| GDS | 2.78 (2.72) | 2.64 (2.17) | ns |

| Gender | 24 female; 14 males | 15 females; 5 males | ns |

MCI, mild cognitive impairment; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; WRAT-IV, Wide Range Achievement Test-IV; ns, not significant.

Latency and neuropsychological test performance

Stepwise regression analysis. In this analysis, latency for the third digit backward entered the model first (χ2 = 69.15, df = 1, p < 0.011); followed by the fourth digit backward (χ2 = 61.03, df = 1, p < 0.004); then the second digit backward (χ2 = 56.45, df = 1, p < 0.032). Latency for the fifth and last response was not significant. The Wald statistic found that latency for the third digit backward was able to predict group membership (Wald = 7.61, df = 1, p < 0.006). Only borderline or marginal significance was obtained for latency for the second digit backward (Wald = 3.23, df = 1, p < 0.072) and the fourth digit backward (Wald = 3.98, df = 1, p < 0.046). Based on these analyses and to minimize the number of statistical tests that were conducted, only latencies to generate the first and third digits backward were analyzed.

ROC analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were conducted and were consistent with the logistic regression analyses reported above. For the memory clinic/no-MCI group, area under the curve was: 2nd digit backward = 0.723, 3rd digit backward = 0.256, 4th digit backward = 0.658. For the memory clinic/MCI group area under the curve was: 2nd digit backward = 0.278, 3rd digit backward = 0.744, 4th digit backward = 0.343 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve

| Memory Clinic-No MCI Group | Area under the curve | 95% confidence interval | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-span position 2 | 0.723 | 0.574 – 0.871 | 0.867 | 0.450 |

| 5-span position 3 | 0.256 | 0.113 – 0.399 | 0.200 | 0.650 |

| 5-span position 4 | 0.658 | 0.502 – 0.813 | 0.767 | 0.400 |

| Memory | ||||

| Clinic-MCI Group | ||||

| 5-span position 2 | 0.278 | 0.129 – 0.426 | 0.400 | 0.500 |

| 5-span position 3 | 0.744 | 0.601 – 0.887 | 0.800 | 0.333 |

| 5-span position 4 | 0.343 | 0.187 – 0.498 | 0.550 | 0.733 |

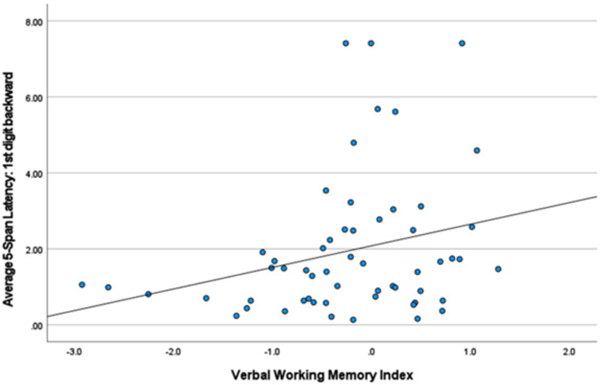

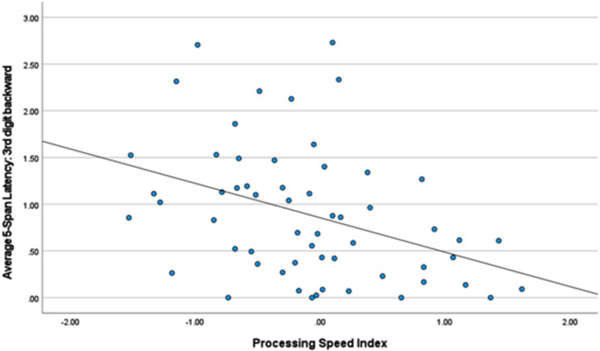

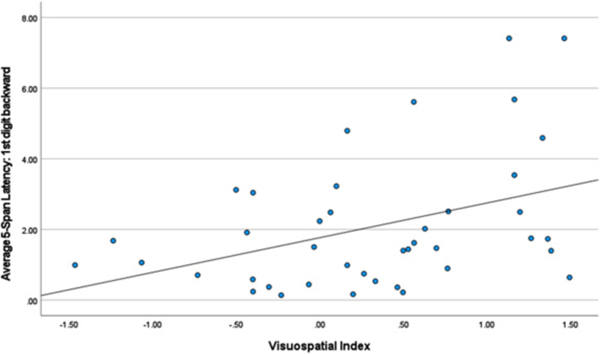

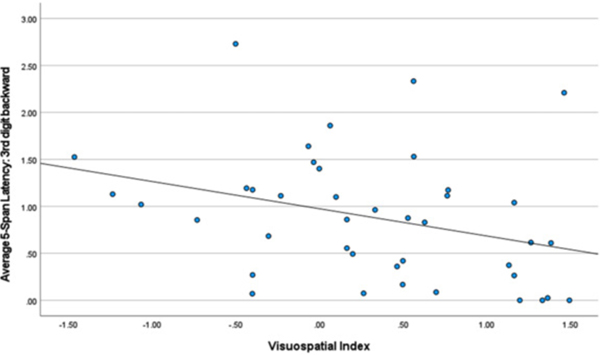

Backward Digit Span – first and third latencies. Table 4 lists correlations between the first and third latencies and neuropsychological index scores. Slower latency to generate the first response was related to better visuospatial (r = 0.397, p < 0.010) and verbal working memory test performance (r = 0.272, p < 0.041). By contrast, faster latency to generate the third response was related to better scores measuring information processing speed (r = −0.384, p < 0.003) and visuospatial (r = −0.327, p < 0.037) test performance (see Figs. 1–3).

Table 4.

Correlations: Backward Digit Span Latency and Neuropsychological Test Performance

| First Digit Backward Latency | Third Digit Backward Latency | |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal Working Memory | r = 0.272, p < 0.041 | ns |

| Visual Working Memory | ns | ns |

| Information Processing | ns | r = −0.384, p < 0.003 |

| Speed | ||

| Naming/Lexical Access | ns | ns |

| Visuospatial Operations | r = 0.397, p < 0.010 | r = −0.327, p < 0.037 |

| Verbal Episodic Memory | ns | Ns |

BDST, Backward Digit Span Test; ns, not significant.

Fig. 1.

Verbal Working Memory and 1st Digit Backward.

Fig. 3.

Processing Speed Index and 3rd Digit Backward.

DISCUSSION

The current research sought to test the hypothesis that the cognitive abilities that underlie successful performance on a backward digit span test change as a function of time epoch, a construct derived from the theory of executive attention [8]. The results of the current research, where patients were asked to repeat digits backward, found that different neuropsychological operations were, indeed, associated with different epochs to generate a correct response. For example, a slower latency to generate the first response was associated with better performance on visuospatial and verbal WM tests. However, by the middle of the test trial, the relationship between latency and neuropsychological test performance changed such that a faster latency was associated with better information processing speed and visuospatial skills.

These BDST results are comparable to findings obtained using a pointing span test as described by Emrani and colleagues [19], where patients were shown a response key and asked to re-order stimuli by pointing to numbers from lowest to highest. First, in both experiments, average time to completion did not differ between groups. Second, between-group differences were observed on selected intra-component latencies. Third, selected intra-component latencies were associated with specific cognitive abilities. Thus, on the pointing span test [19], initial correct responding was associated with better performance on tests assessing verbal working memory and naming/lexical access while latter correct responding was associated with better performance on verbal working memory abilities. These data suggest that initial correct responding called upon previously acquired lexical and memory-based information whereas the latency to generate the last response was associated with cognitive abilities associated with mental manipulation.

In the context of Fuster’s theory of executive attention [8], working memory recruits the necessary neurocognitive operations to establish mental set. In establishing the necessary mental set to repeat five digits backward, a significant amount of time (i.e., a slower initial latency) appears to be necessary to recruit a combination of underlying neurocognitive operations (visuospatial & executive operations). However, by the middle of the test trial, i.e., by the time the third response is generated, the relationship between latency and neuropsychological test performance changes. Having recruited the necessary neurocognitive resources for initial re-ordering, the mechanisms underlying preparatory set or the ability to sustain mental set are now recruited. The neurocognitive operations associated with the latency to generate the third response appear to be associated with a combination of visuospatial and information processing speed operations. It is possible that the faster latency observed in conjunction with these neurocognitive operations suggests that having devoted a considerable amount of time at the beginning of the test trial to establish a mode of responding, less time is now needed to sustain a correct response.

The results from prior research [19] and the current research suggest that successful mental manipulation, per se, is not monolithic, but highly contextualized. Thus, depending on the task at hand (e.g., backward digits versus digit/letter re-ordering), different underlying constituent neuropsychological operations are recruited at key time intervals to complete a task successfully. Implicitly, the results from both experiments suggest that successful responding recruits complementary, but different underlying brain regions. Data from both experiments comports with prior working memory research suggesting that the attributes of information to be manipulated reside in posterior cortical regions, while the role of frontal cortical regions is to provide guidance regarding how best to bring tasks to fruition (see D’Esposito & Postle [6] for a review). We acknowledge that all these suppositions are preliminary and require additional research.

As described above there are many similarities between Fuster’s theory of executive attention [8] and models of executive control suggested by other researchers. However, there are some differences. For example, the work done by Miyake and colleagues [2] is based on sophisticated statistical analyses of correct and incorrect responding using a protocol of clinical and experimental tasks to extract a variety of latent variables related to executive control. By contrast, the theory of executive attention [8] emphasizes the importance of a single neurocognitive construct – the temporal gradient – from which the constructs of working memory, preparatory set, and inhibitory control are derived. Given the temporal gradient (i.e., time- and sequentially-dependent ordering of tasks), our strategy in the current research was to assess how these time-based responses can be defined via an analysis of correct test trials, and how epochs for each individual response relate to other cognitive abilities.

Results from research using a variety of electrophysiological techniques find some support for the constructs that comprise Fuster’s theory of executive attention [8] research. For example, neural oscillations at different frequencies have been shown to be related to differing underlying cognitive operations [52]. Gamma-band oscillations appear to be associated with establishing the necessary mental set on working memory tests [53] while theta-band activity may be associated with the organization of sequentially ordered responses from working memory tests [54] and related to Fuster’s theory to executive attention [8] constructs of working memory and preparatory set, respectively. Additional research has found that alpha-band activity appears to be associated with the inhibition of task-irrelevant information [55], similar to Fuster’s theory of executive attention’s construct of inhibitory control [8].

Prior research using backward digit span tests has also found a robust relationship between backward digit span performance and greater prefrontal volume and prefrontal cortical thickness [56] as well as other brain regions [57]. The association between successful backward digit span performance, selected latencies, and neurocognitive operations comport with prior clinical research linking problems in repeating digits backward with visuospatial operations [58–60] to suggest initial and sustained activation of posterior cortical regions. Further, Lamar and colleagues [22] found reduced BSDT performance to be associated with greater left-sided frontal and posterior white matter alterations in patients with dementia, suggesting that successful BDST performance may be mediated by a rich frontal-parietal neurocognitive network. Bezdicek and colleagues [61] studied a large cohort of non-demented idiopathic Parkinson’s disease patients with the BDST. They found significant mental manipulation deficits among Parkinson’s disease patients diagnosed with MCI. In addition, functional imaging technology found significant correlations between BDST performance and dorsolateral prefrontal regions.

Risberg and Ingvar [62] noted that repeating digits backwards resulted in increased blood flow to prefrontal and temporal cortical regions. Richardson and colleagues [63] also found an association between backward digit span performance and posterior temporal brain regions. All of this research is consistent with the assertion that what is commonly understood as executive tasks do not necessarily live in frontal regions but are mediated by frontal lobe activity [8, p. 335]. That is to say, test paradigms commonly understood as executive tasks appear to require the ability to place the sensory attributes of the test situation, likely governed, in part, by posterior cortical regions, into context with the necessary superordinate operations that are regulated by frontal brain regions.

Accurately diagnosing MCI subtypes has many beneficial clinical implications, including a better understanding of functional impairments and enabling early interventions with targeted treatment. Overall, conversion rates from MCI to AD range anywhere between 14–87%, depending on the sample and diagnostic criteria [64]. Clinical subtypes of MCI are often separated into subtypes; amnestic, dysexecutive, anomic and a mixed phenotype [42]. Moreover, MCI subtypes can be associated with specific dementia subtypes. For example, those diagnosed with an amnestic MCI are likely to covert to AD, should they progress to dementia [65–67]. Non-amnestic single or mixed subtypes can progress to vascular dementia [66, 68]. However, recent studies have also demonstrated that non-amnestic cognitive deficits can be early signs of AD as well [69]. Biomarker results related to differentiating MCI subtypes are promising, although more work is needed to validate findings. For example, previous research investigated cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β42 and total tau, phosphorylated tau, fluorodeoxyglucose, positron-emission tomography, and MRI neuroimaging measures in people with subjective cognitive decline, amnestic MCI and non-amnestic MCI [70]. Elevated t-tau, lower cortical glucose metabolism, and thinner entorhinal cortices was able to differentiate amnestic MCI from the non-amnestic group. Other studies have found AD-related biomarkers (tau and amyloid-β42) to correlate with amnestic MCI [67], while AD- and non-AD-related biomarkers have also been associated with other types of dementias, like vascular dementia [71]. Additional work is needed to assess how the latency and time-based parameter used in the current research might also dissociate between MCI subtypes.

Elements involving cross-modal neurocognitive operations [72, 73] might also help explain why different neuropsychological operations appear to be present as a function of time. Geschwind [74] assigned great importance to the capacity of the posterior parietal and inferior temporal regions for processing cross-modal sensory information, i.e., processing visually presented information such as letters or graphomotor information that facilitate the ability to read and write. The act of initially “hearing” a string of digits followed by higher-order mechanisms by which numbers are visually and mentally rotated before and during the actual generation of a response is compatible with this model.

The current research is not without limitations. First, methods used with primates to investigate the differential operations of time epochs related to underlying neurocognitive operations is very different than the methods used in the current research. Additional research, perhaps using functional imaging technology such as near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) [75] could be useful. Second, the mechanism of inhibitory control was not addressed in the current research. By definition, this mechanism is related to errors. In the current research, only correct test trials were examined. A task for future research is to compare latencies for correct versus incorrect responding. Third, our sample is modest and lacks racial and ethnic diversity. Our modest sample size may also be responsible for the modest ROC results seen in Table 4. Fourth, although there was no statistical difference between our groups regarding general intellectual abilities as assessed with the WRAT-IV reading subtest, the memory clinic/no-MCI group tended to score better on this test. Such behavior may have influenced our outcome measures. Fifth, the current research lacked fluid biomarker and imaging data that might have allowed for a more specific characterization of our memory clinic sample. Finally, a task for the future is to obtain the latency, the time-based parameters used in the current research along with functional imaging data or a related neurophysiological technique to further explore how time-based parameters might be distributed across various brain regions. This type of data might provide additional support that the time-based data obtained in the current research can be interpreted in the context of the theory of executive attention [8].

However, the current research has several strengths including using validated actuarial criteria to classify patients with MCI and no-MCI, and the use of digital technology that is reliable, inexpensive, and available to assess cognitive abilities. Also, the data reported above has potentially important clinical applications. For example, despite correct responding, an atypical profile with respect to latency could signal the presence of an emergent problem. Further research is necessary to make this determination. In sum, the current research supports the notion that neurocognitive operations commonly acknowledged as assessing executive control can be understood relative to how different neurocognitive operations are recruited as a function of time epochs.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 2.

Visuospatial Index and 1st Digit Backward.

Fig. 4.

Visuospatial Index and 3rd Digit Backward.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors grateful the patients and their families who took park in this research.

FUNDING

Funding for this research was obtained from the Osteopathic Heritage Foundation and the New Jersey Health Foundation (ISFP 23–19).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Libon is an Editorial Board Member of this journal but was not involved in the peer-review process nor had access to any information regarding its peer-review. Dr. Libon receives royalties from Linus Health. Drs. Libon and Swenson receive royalties from Oxford University Press.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-230288.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data is not available at the current time.

REFERENCES

- [1].Diamond A (2013) Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 64, 135–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD (2000) The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol 41, 49–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lewis-Peacock JA, Postle BR (2012) Decoding the internal focus of attention. Neuropsychologia 50, 470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oberauer K (2002) Access to information in working memory: Exploring the focus of attention. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 28, 411–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Baddeley AD, Hitch GJ (1974) Working memory. In The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, Vol. 8, Bower GH, ed. Academic Press, New York, pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- [6].D’Esposito M, Postle BR (2015) The cognitive neuroscience of working memory. Annu Rev Psychol 66, 115–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fuster JM (2009) Cortex and memory: Emergence of a new paradigm. J Cogn Neurosci 21, 2047–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fuster JM (2015) The Prefrontal Cortex, 5th edition, Academic Press. Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fuster JM, Alexander GE (1971) Neuron activity related to short-term memory. Science 173, 652–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fuster JM (2002) Frontal lobe and cognitive development. J Neurocytol 31, 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fuster JM (2003) Cortex and mind: Unifying cognition. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Quintana J, Fuster JM (1999) From perception to action: Temporal integrative functions of prefrontal and parietal neurons. Cereb Cortex 9, 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang L, Li X, Hsiao SS, Lenz FA, Bodner M, Zhou YD, Fuster JM (2015) Differential roles of delay-period neural activity in the monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in visual-haptic crossmodal working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, E214–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Courtney SM, Ungerleider LG, Keil K, Haxby JV (1997) Transient and sustained activity in a distributed neural system for human working memory Nature 386, 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].D’Esposito M, Postle BR, Rypma B (2000) Prefrontal cortical contributions to working memory: Evidence from event-related fMRI studies. Exp Brain Res 133, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Libon DJ, Drabick DA, Giovannetti T, Price CC, Bondi MW, Eppig J, Devlin K, Nieves C, Lamar M, Delano-Wood L, Nation DA, Brennan L, Au R, Swenson R (2014) Neuropsychological syndromes associated with Alzheimer’s/vascular dementia: A latent class analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 42, 999–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Piers RJ, Devlin KN, Ning B, Liu Y, Wasserman B, Massaro JM, Lamar M, Price CC, Swenson R, Davis R, Penney DL, Au R, Libon DJ (2017) Age and graphomotor decision making assessed with the Digital Clock Drawing Test: The Framingham Heart Study. J Alzheimers Dis 60, 1611–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Brown CA (2017) The default mode network and executive function: influence of age, white matter connectivity, and Alzheimer’s pathology. University of Kentucky. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Emrani S, Lamar M, Price CC, Baliga S, Wasserman V, Matusz E, Swenson R, Baliga G, Libon DJ (2021) Assessing the capacity for mental manipulation in patients with statistically determined mild cognitive impairment using digital technology. Explor Med 2, 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sheslow D, Adams W (2003) Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning Second Edition administration and technical manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz, FL. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lamar M, Price CC, Libon DJ, Penney DL, Kaplan E, Grossman M, Heilman KM (2007) Alterations in working memory as a function of leukoaraiosis in dementia. Neuropsychologia 45, 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lamar M, Catani M, Price CC, Heilman KM, Libon DJ (2008) The impact of region-specific leukoaraiosis on working memory deficits in dementia. Neuropsychologia 46, 2597–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Emrani S, Lamar M, Price C, Baliga S, Wasserman V, Matusz EF, Saunders J, Gietka V, Strate J, Swenson R, Baliga G, Libon DJ (2021) Neurocognitive constructs underlying executive control in statistically-determined mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 82, 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Eppig J, Wambach D, Nieves C, Price CC, Lamar M, Delano-Wood L, Giovannetti T, Bettcher BM, Penney DL, Swenson R, Lippa C, Kabasakalian A, Bondi MW, Libon DJ (2012) Dysexecutive functioning in mild cognitive impairment: Derailment in temporal gradients. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 18, 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Emrani S, Libon DJ, Lamar M, Price CC, Jefferson AL, Gifford KA, Hohman TJ, Nation DA, Delano-Wood L, Jak A, Bangen KJ, Bondi MW, Brickman AM, Manly J, Swenson R, Au R (2018) Consortium for Clinical and Epidemiological Neuropsychological Data Analysis (CENDA). Assessing working memory in Mild Cognitive Impairment with serial order recall. J Alzheimers Dis 61, 917–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Emrani S, Lamar M, Price C, Baliga S, Wasserman V, Matusz EF, Saunders J, Gietka V, Strate J, Swenson R, Baliga G, Libon DJ (2021) Neurocognitive constructs underlying executive control in statistically-determined mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 82, 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Libon DJ, Bondi MW, Price CC, Lamar M, Eppig J, Wambach DM, Nieves C, Delano-Wood L, Giovannetti T, Lippa C, Kabasakalian A, Cosentino S, Swenson R, Penney DL (2011) Verbal serial list learning in mild cognitive impairment: A profile analysis of interference, forgetting, and errors. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 17, 905–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wasserman V, Emrani S, Matusz EF, Miller D, Garrett KD, Gifford KA, Hohman TJ, Jefferson AL, Au R, Swenson R, Libon DJ (2019) Consortium for Clinical and Epidemiological Neuropsychological Data Analysis (CENDA). Visual and verbal serial list learning in patients with statistically-determined mild cognitive impairment. Innov Aging 3, igz009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wechsler D (2009) Wechsler Memory Scale IV (WMS-IV). Psychological Corporation, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wechsler D (1997) WAIS-III administration and scoring manual. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Benton AL, Varney NR, Hamsher KD (1978) Visuospatial judgment. A clinical test. Arch Neurol 35, 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Benton AL, Sivan AB, Hamsher KD, Varney NR, Spreen O (1994) Contributions to neuropsychological assessment (2nd ed). Psychological Assessment Resources, Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Brannigan GG, Decker SL (2006) The Bender-Gestalt II. Am J Orthopsychiatry 76, 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Libon DJ, McMillan C, Gunawardena D, Powers C, Massimo L, Khan A, Morgan B, Farag C, Richmond L, Weinstein J, Moore P, Coslett HB, Chatterjee A, Aguirre G, Grossman M (2009) Neurocognitive contributions to verbal fluency deficits in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 73, 535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Libon DJ, Xie SX, Eppig J, Wicas G, Lamar M, Lippa C, Bettcher BM, Price CC, Giovannetti T, Swenson R, Wambach DM (2010) The heterogeneity of mild cognitive impairment: A neuropsychological analysis J Int Neuropsychol Soc 16, 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lamar M, Price CC, Davis KL, Kaplan E, Libon DJ (2002) Capacity to maintain mental set in dementia. Neuropsychologia 40, 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Heaton RK, Miller S, Taylor M, Grant I (2004) Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults scoring programs. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Spreen O, Strauss E (1990) Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests. Oxford University Press; New York. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Reitan RM, Wolfson D (1985) The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. Neuropsychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S (1983) The Boston Naming Test. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA (2000) The California Verbal Learning Test-II. Psychology Corporation, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Jak AJ, Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, McDonald CR, Nation DA, Libon DJ, Au R, Galasko D, Salmon DP (2014) Neuropsychological criteria for mild cognitive impairment improves diagnostic precision, biomarker associations, and progression rates. J Alzheimers Dis 42, 275–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Clark LR, Jak AJ, Nation DA, McDonald CR, Libon DJ, Au R, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Bondi MW, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2015) Susceptibility of the conventional criteria for mild cognitive impairment to false-positive diagnostic errors. Alzheimers Dement 11, 415–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Edmonds EC, Ard MC, Edland SD, Galasko DR, Salmon DP, Bondi MW (2017) Unmasking the benefits of donepezil via psychometrically precise identification of mild cognitive impairment: A secondary analysis of the ADCS vitamin E and donepezil in MCI study. Alzheimers Dement 4, 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Jak AJ, Bondi MW, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga C, Corey-Bloom J, Salmon DP, Delis DC (2009) Quantification of five neuropsychological approaches to defining mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 17, 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dixon WJ (1960) Simplified estimation from censored normal samples. Ann Math Stat 31, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO (1982) Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 17, 37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wilkinson GS, Robertson G (2006) Psychological Assessment Resources I. WRAT 4: Wide Range Achievement Test. Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9, 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Roux F, Uhlhaas PJ (2014) Working memory and neural oscillations: α-γ versus θ-γ codes for distinct WM information? Trends Cogn Sci 18, 16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Haegens S, Osipova D, Oostenveld R, Jensen O (2010) Somatosensory working memory performance in humans depends on both engagement and disengagement of regions in a distributed network. Hum Brain Mapp 31, 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sauseng P, Klimesch W, Heise KF, Gruber WR, Holz E, Karim AA, Glennon M, Gerloff C, Birbaumer N, Hummel FC (2009) Brain oscillatory substrates of visual short-term memory capacity. Curr Biol 19, 1846–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Moran RJ, Campo P, Maestu F, Reilly RB, Dolan RJ, Strange BA (2010) Peak frequency in the theta and alpha bands correlates with human working memory capacity. Front Hum Neurosci 4, 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yuan P, Raz N (2014) Prefrontal cortex and executive functions in healthy adults: A meta-analysis of structural neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 42, 180–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sun X, Zhang X, Chen X, Zhang P, Bao M, Zhang D, Chen J, He S, Hu X (2005) Age-dependent brain activation during forward and backward digit recall revealed by fMRI. Neuroimage 26, 36–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Robertson IH (1990) Digit span and visual neglect: A puzzling relationship. Neuropsychologia 28, 217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Rudel RG, Denckla MB (1974) Relation of forward and backward digit repetition to neurological impairment in children with learning disabilities. Neuropsychologia 12, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Weinberg J, Diller L, Gerstman L, Schulman P (1972) Digit span in right and left hemiplegics. J Clin Psychol 28, 361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bezdicek O, Ballarini T, Albrecht F, Libon DJ, Lamar M, Růžička F, Roth J, Hurlstone MJ, Mueller K, Schroeter ML, Jech R (2021) SERIAL-ORDER recall in working memory across the cognitive spectrum of Parkinson’s disease and neuroimaging correlates. J Neuropsychol 15, 88–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Risberg J, Ingvar DH (1973) Patterns of activation in the grey matter of the dominant hemisphere during memorizing and reasoning. A study of regional cerebral blood flow changes during psychological testing in a group of neurologically normal patients. Brain 96, 737–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Richardson FM, Ramsden S, Ellis C, Burnett S, Megnin O, Catmur C, Schofield TM, Leff AP, Price CJ (2011) Auditory short-term memory capacity correlates with gray matter density in the left posterior STS in cognitively normal and dyslexic adults. J Cogn Neurosci 12, 3746–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Chen Y, Qian X, Zhang Y, Su W, Huang Y, Wang X, Chen X, Zhao E, Han L, Ma Y (2022) Prediction models for conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 14, 840386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ (2004) Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer’s disease. J Intern Med 256, 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Busse A, Hensel A, Gühne U, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG (2006) Mild cognitive impairment: Long-term course of four clinical subtypes. Neurology 67, 2176–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Giau VV, Bagyinszky E, An SSA (2019) Potential fluid biomarkers for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. Int J Mol Sci 20, 4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tabert MH, Manly JJ, Liu X, Pelton GH, Rosenblum S, Jacobs M, Zamora D, Goodkind M, Bell K, Stern Y, Devanand DP (2006) Neuropsychological prediction of conversion to Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63, 916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Emrani S, Lamar M, Price CC, Wasserman V, Matusz E, Au R, Swenson R, Nagele R, Heilman KM, Libon DJ (2020) Alzheimer’s/vascular spectrum dementia: Classification in addition to diagnosis. J Alzheimers Dis 73, 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Eliassen CF, Reinvang I, Selnes P, Grambaite R, Fladby T, Hessen E (2017) Biomarkers in subtypes of mild cognitive impairment and subjective cognitive decline. Brain Behav 7, e00776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Gorelick PB (2003) Blood and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: A brief review. Clin Geriatr Med 39, 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Butters N, Barton M, Brody BA (1970) Role of the right parietal lobe in the mediation of cross-modal associations and reversible operations in space. Cortex 6, 174–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hötting K, Friedrich CK, Röder B (2009) Neural correlates of cross-modally induced changes in tactile awareness. J Cogn Neurosci 21, 2445–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Geschwind N (1965) Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. I. Brain 88, 237–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Fuster J, Guiou M, Ardestani A, Cannestra A, Sheth S, Zhou YD, Toga A, Bodner M (2005) Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in cognitive neuroscience of the primate brain. Neuroimage 26, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available at the current time.