Abstract

Molecular features of the proteinase K-resistant prion protein (PrP res) may discriminate among prion strains, and a specific signature could be found during infection by the infectious agent causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). To investigate the molecular basis of BSE adaptation and selection, we established a model of coinfection of mice by both BSE and a sheep scrapie strain (C506M3). We now show that the PrP res features in these mice, characterized by glycoform ratios and electrophoretic mobilities, may be undistinguishable from those found in mice infected with scrapie only, including when mice were inoculated by both strains at the same time and by the same intracerebral inoculation route. Western blot analysis using different antibodies against sequences near the putative N-terminal end of PrP res also demonstrated differences in the main proteinase K cleavage sites between mice showing either the BSE or scrapie PrP res profile. These results, which may be linked to higher levels of PrP res associated with infection by scrapie, were similar following a challenge by a higher dose of the BSE agent during coinfection by both strains intracerebrally. Whereas PrP res extraction methods used allowed us to distinguish type 1 and type 2 PrP res, differing, like BSE and scrapie, by their electrophoretic mobilities, in the same brain region of some patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, analysis of in vitro mixtures of BSE and scrapie brain homogenates did not allow us to distinguish BSE and scrapie PrP res. These results suggest that the BSE agent, the origin of which remains unknown so far but which may have arisen from a sheep scrapie agent, may be hidden by a scrapie strain during attempts to identify it by molecular studies and following transmission of the disease in mice.

The bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) agent may have originated from a scrapie agent infecting small ruminants, which would have been recycled through cattle and disseminated through the use of contaminated meat and bonemeal. It is assumed to have caused prion diseases not only in cattle but also in a variety of other species, such as domestic cats and some exotic felines and ruminants (7). Strong evidence indicates that the recently described variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) is due to the same agent as well (7), which could also have infected other species in field conditions, such as sheep or goats (8).

The ultimate evidence that infectious agents from different isolates are identical eventually requires transmission of the disease in mice and characterization of the lesion profiles in the brain. Such experiments reveal the existence of a number of different “strains” in natural scrapie from sheep and goats, but it is unknown to what extent these mouse-adapted scrapie strains, with different behavior in mice, are representative of field scrapie strains (6). During the isolation of strains by transmission in mice from a particular isolate, even when the disease features have stabilized in the new host, a mixture of minor strains and a major strain can also be stably passaged, and some changes may then occur following cloning of the major strain by limiting dilution (6). In cattle, a single strain or a limited number of strains with a very stable and uniform behavior in mice have been recognized so far in each case analyzed at different times during the epidemic and from widely separated locations (6, 15).

It has also been found that qualitative and quantitative analysis of the different glycoforms of the proteinase K-resistant prion protein (PrP res), detected by Western blotting, showed a consistent and unique pattern in BSE-linked diseases, as in experimentally infected macaques or mice and in naturally infected domestic cats, as well as in humans developing vCJD (9, 16). Such features also allowed different mouse-adapted scrapie strains to be distinguished (20, 25, 33). These findings, which may result from strain-specific differences in PrP res conformation, argue for a link between the molecular features of the protease-resistant prion protein and strain variation (32, 36).

Regarding the molecular features of PrP res in sheep, a species from which the BSE strain may have emerged, very uniform features have been described in some studies between different isolates from various geographical locations (3, 35). In contrast, a variety of PrP res patterns have also been reported in a few natural and experimental scrapie cases, which was believed to reflect a high diversity of field sheep scrapie strains (17, 19). In a particular experimental sheep scrapie strain (CH 1641), close similarities with the PrP res pattern of BSE in sheep was found (2, 19).

We now report that following infection of mice by both scrapie and BSE strains, the molecular features of PrP res may be indistinguishable from those found in mice infected by scrapie alone, whereas the analysis of in vitro mixtures of scrapie and BSE brain homogenates also suggest that a scrapie PrP res pattern can be found despite the presence of PrP res associated with the BSE agent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and agent strains.

The murine scrapie strains used in this study were C506M3 (kindly provided by D. Dormont, Commissariat à L'Energie Atomique, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France) and Chandler and 79A (kindly provided by M. Bruce, Institute of Animal Health, Edinburgh, United Kingdom). The BSE strain was isolated from a French cattle BSE case. These strains were routinely maintained by serial passage into C57BL/6 mice (IFFA Credo) by intracerebral inoculation of 1% (wt/vol) brain homogenate in 5% glucose in distilled water (20 μl per animal) from brains sampled at the terminal stage of the disease.

For coinfection of mice by both BSE and scrapie, the C506M3 scrapie strain was chosen. Coinfections were performed by intracerebral (20 μl of brain homogenate per animal) or intraperitoneal (100 μl of brain homogenate per animal) inoculation of both scrapie and BSE strains in the same animals, as described in Table 1. For molecular studies of coinfected animals, Western blot analysis was performed on samples from three different animals per experimental group from brains sampled at the terminal stage of the disease.

TABLE 1.

Inocula and inoculation routes used in the different experimental groups of mice

| Group | BSE

|

Scrapie strain C506M3

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain homogenate concn (%, wt/vol) | Amt (μl) | Routea | Brain homogenate concn (%, wt/vol) | Amt (μl) | Route | |

| 1 | 1 | 20 | IC | — | — | — |

| 2 | 1 | 10 | IC | 1 | 10 | IC |

| 3 | 20 | 10 | IC | 1 | 10 | IC |

| 4 | 1 | 20 | IC | 0.2 | 100 | IP |

| 5 | 0.2 | 100 | IP | 1 | 20 | IC |

| 6 | — | — | — | 1 | 20 | IC |

IC, intracerebral; IP, intraperitoneal.

Cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Thirty-two patients with clinical Creutzfeld-Jakob disease were characterized by Western blot analysis of brain tissue. The frontal cortex, striatum, and cerebellum were studied from each patient when available as frozen tissues.

Extraction of PrP res.

PrP res was obtained by two different methods. The first method, previously described for sheep PrP res typing (3), involved PrP res concentration by ultracentrifugation. Dissociation of half of the whole brain of mice or equivalent quantities of brain material from humans was performed in 1 ml of 5% glucose in distilled water, using disposable blenders, and complete homogenization was obtained by forcing the brain suspension through a 0.4-mm-diameter needle. A 330-μl volume was brought up to 1.2 ml in 5% glucose before incubation with proteinase K (20 to 25 μg/100 mg of brain tissue) (Roche) for 1 h at 37°C. N-Lauroyl sarcosyl (30%; 600 μl) (Sigma) was added. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, samples were centrifuged at 465,000 × g for 2 h on a 10% sucrose cushion in a Beckman TL100 ultracentrifuge. Pellets were resuspended and heated for 5 min at 100°C in 50 μl of denaturing buffer (4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 192 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris, 5% sucrose).

A second method involved direct search for PrP res in brain homogenates without any ultracentrifugation step, as previously described for PrP res typing in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (9). After homogenization in 5% glucose and proteinase K digestion as previously described, the digestion was stopped by the addition of Pefabloc (Roche) to a 1 mM final concentration. Then, the sample was mixed with the same volume of denaturing buffer, heated for 5 min at 100°C, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants were then collected for further studies by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

For analysis of in vitro mixtures of BSE and scrapie, brain homogenates of each strain were mixed in different proportions before treatment by proteinase K and ultracentrifugation. Samples corresponding to different ratios of BSE and scrapie PrP res were then analyzed and compared to BSE or scrapie alone by Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis.

Samples were run in SDS–15% PAGE and electroblotted to nitrocellulose membranes in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 10% isopropanol) at a constant 400 mA for 1 h. The membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dried milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–0.1% Tween 20 (PBST). After two washes in PBST, for mouse PrP res studies, membranes were incubated (1 h at room temperature) with RB1 rabbit antiserum (1:2,500 in PBST) raised against synthetic bovine (THGQWNKPSKPKTNMK) PrP peptide (28) or SAF15 monoclonal antibody (kindly provided by J. Grassi, SPI/CEA, Saclay, France). SAF15 was prepared against formic acid-treated hamster SAFs and shown to recognize the 79-92 human PrP sequence. For human PrP res studies, 3F4 monoclonal antibody (Senetek) (1:5,000 in PBST) was used (21). After three washes in PBST, the membranes were incubated (30 min at room temperature) with peroxidase-labeled conjugates against rabbit or mouse immunoglobulins (1:2,500 in PBST) (Clinisciences). After three washes in PBST, bound antibodies were then detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) or Supersignal (Pierce) chemiluminescent substrates. For quantitative studies of the glycoform ratios, chemiluminescent signals corresponding to the three glycoforms of the protein were quantified using a Fluor S-Multimager (Bio-Rad) analysis system. Glycoform ratios were expressed as mean percentages ± standard errors of the total signal for the high (H), low (L), and unglycosylated (U) glycoforms obtained from three mice per experimental group and at least five separate gel runs per sample. Migrations of the unglycosylated PrP res were compared on films after exposure of the membranes on Biomax MR Kodak films (Sigma) from repeated runs of the samples. After preliminary experiments, loads of samples per lane were adjusted for comparison between the different animal groups, to provide the best comparison of electrophoretic mobilities, but in experiments that were specifically designed to compare the levels of PrP res accumulation in brain.

Deglycosylation of PrP res.

For deglycosylation of PrP res, pellets obtained following proteinase K treatment and ultracentrifugation from brain homogenates were denatured by heat treatment at 100°C for 10 min in 50 μl of 0.5% SDS in distilled water. After addition of 200 μl of 0.5% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, the samples were treated by PNGase F (Roche) (1 U/sample) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Proteins were then precipitated in ethanol and finally resuspended in 50 μl of denaturing buffer before analysis by SDS-PAGE as previously described.

RESULTS

Glycoform profiles of PrP res in BSE and scrapie strains.

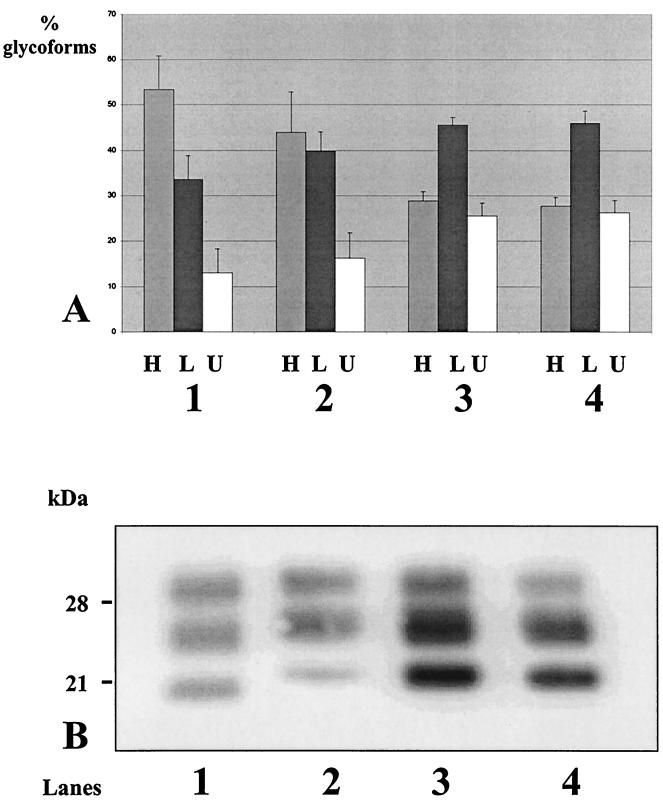

The glycoform ratios in BSE and the three scrapie strains C506M3, Chandler, and 79A could be distinguished, as shown in Fig. 1A, especially showing high levels of diglycosylated protein and low levels of unglycosylated protein in BSE. In both 79A and Chandler strains, the monoglycosylated PrP res was the most abundant species, whereas the C506M3 strain had intermediate features compared to BSE and to these last scrapie strains and showed comparable levels of di- and monoglycosylated protein.

FIG. 1.

Proportions of PrP res glycoforms (A) and comparison of electrophoretic mobilities (B) in BSE- and scrapie-infected mice after Western blot analysis using RB1 antiserum. Proportions of glycoforms are expressed as arithmetical means ± standard error of high-glycosylation (H), low-glycosylation (L), and unglycosylated (U) PrP res. Animal groups: 1, BSE; 2, C506M3 scrapie strain; 3, Chandler scrapie strain; 4, 79A scrapie strain.

Regarding the apparent molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrP res, among these four strains, that from BSE also had a specifically lower molecular mass than that from the three different scrapie strains (Fig. 1B).

Glycoform profiles following coinfection of mice by BSE and scrapie.

For studies of the PrP res patterns of animals coinfected by BSE and scrapie, we inoculated mice with a mixture of brain homogenates from C506M3 and from BSE-infected terminally ill mice. We studied PrP res at the terminal stage of the disease in three mice per experimental group of BSE- and scrapie-coinfected mice (176 to 212 days postinoculation).

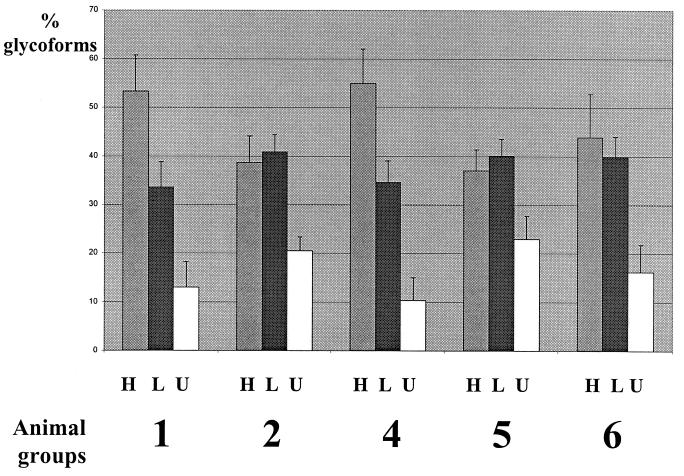

The results of the glycoform analysis in mice infected with both strains showed that only mice inoculated with BSE by the intracerebral route and intraperitoneally with scrapie (group 4) had a profile similar to that found in mice infected with BSE only (group 1) (Fig. 2), with no statistically significant differences in the glycoform ratios at the 5% level. On the other hand, mice inoculated by both BSE and scrapie by the same intracerebral route (group 2), as well as mice inoculated intracerebrally by scrapie and intraperitoneally by BSE (group 5), did not show statistically significant differences in the glycoform ratios (at the 5% level) from mice inoculated with scrapie only (group 6). In contrast, experimental groups 1 and 4 (BSE profile) were highly significantly different from groups 2, 5, and 6 (scrapie profile) (P = 0.005 and 0.004 for the diglycosylated and monoglycosylated forms, respectively). These differences between groups with a BSE profile (1 and 4) and those with a scrapie profile (2, 5, and 6) were assessed not only by studies of the glycoform ratios (Fig. 2) but also by analysis of the electrophoretic mobilities of the unglycosylated PrP res (Fig. 3). They were also confirmed by comparison of the molecular masses of PrP res after deglycosylation by PNGase (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Proportions of mouse PrP res glycoforms after Western blot analysis using RB1 antiserum. Proportions of glycoforms are expressed as arithmetical means ± standard error of high-glycosylation (H), low-glycosylation (L), and unglycosylated (U) PrP res. Groups were inoculated as described in Table 1.

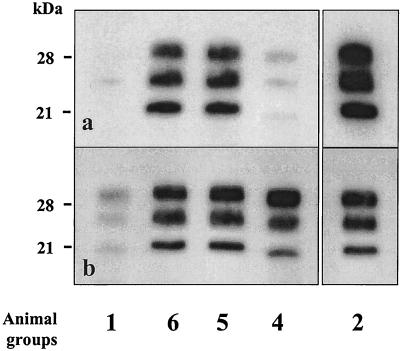

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of mouse PrP res detected using RB1 antiserum. Animal groups were inoculated as described in Table 1.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of mouse PrP res detected using RB1 antiserum following deglycosylation by PNGase F. Groups were inoculated as described in Table 1.

In order to evaluate the possible influence of PrP res extraction methods, we analyzed PrP res directly detected from brain homogenates, as previously described for PrP res typing in human Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (9), rather than SAF preparation by ultracentrifugation. Similar results were obtained with this method (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, these experiments allowed a direct comparison of PrP res detection following loading of similar quantities of brain material per lane in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5a, with 0.5 mg of brain equivalent per lane). Mice inoculated with BSE only intracerebrally (group 1) or with BSE intracerebrally and scrapie intraperitoneally (group 4) had the lowest levels of PrP res; other groups of mice (groups 2, 5, and 6), which otherwise had a scrapie PrP res pattern, had higher levels of PrP res.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of mouse PrP res directly detected from brain homogenates using RB1 antiserum. Animal groups are defined in Table 1. Brain equivalents loaded per lane: (a) 0.5 mg; (b) from left to right, 0.6, 0.25, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.2 mg.

In a separate experiment, we challenged mice by both strains intracerebrally (group 3) but with a higher (20×) dose of the BSE strain in the inoculum (20% BSE-infected brain homogenate) mixed with the scrapie strain (1% scrapie-infected brain homogenate). In this case again, we could not detect any difference in the electrophoretic mobility of the unglycosylated protein when we compared these mice to animals infected with scrapie only (group 6); the apparent molecular mass also appeared to be clearly distinguishable from and higher than that in mice infected with BSE only (group 1) (Fig. 3, lane 3).

Molecular analysis of in vitro mixtures of BSE and scrapie.

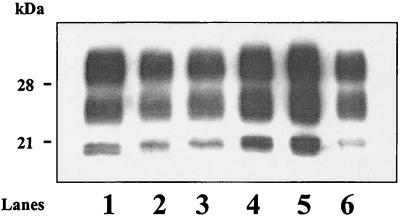

We then analyzed PrP res extracted from in vitro mixtures of C506M3 and BSE brain homogenates in different proportions. As shown in Fig. 6, these studies revealed that the unglycosylated protein always appeared as a single band, as previously found in BSE- and scrapie-coinfected mice. The electrophoretic mobility depended upon the proportions of scrapie and BSE; nevertheless, it decreased rapidly close to that found in scrapie as soon as the quantity of scrapie brain material increased. Similar results, showing a single band for unglycosylated PrP res, were also obtained following Western blotting of BSE and scrapie PrP res mixed after separate extractions of the two strains and mixtures of the proteins after their denaturation (data not shown). In a 20:1 BSE-C506 mixture, a single band with a size intermediate between those observed in BSE and scrapie was detected (Fig. 6, lane 2).

FIG. 6.

Western blot analysis of in vitro mixtures of mouse PrP res from scrapie and BSE strains using RB1 antiserum. Lane 1, BSE alone. Lanes 2 to 6, BSE-scrapie ratios of 20:1, 10:1, 5:1, 2:1, and 1:1, respectively.

Analysis of PrP res proteinase K cleavage sites by antigenic mapping.

Since different fragment sizes of PrP res were observed for scrapie and BSE, we further compared mice infected with BSE or strain C506M3 only or with both strains, using antibodies acting near the expected proteinase K cleavage site (10, 18). We used RB1 antiserum and SAF15 monoclonal antibody directed against sequences corresponding to residues 94 to 109 and 78 to 91 of the murine PrP, respectively.

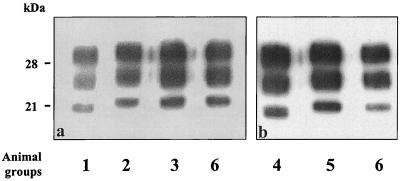

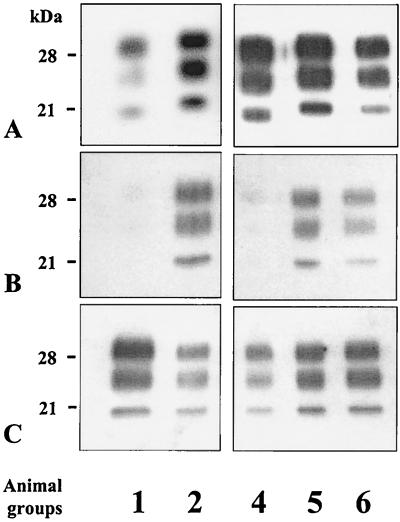

We first loaded comparable quantities of PrP res per lane, as recognized by RB1 antiserum after quantification of the samples with the Fluor-S MultiImager (Fig. 7A). Using SAF15 monoclonal antibody to detect PrP res from samples run in duplicate gels, we then found quite a lower reactivity in mice infected with BSE only (group 1) (Fig. 7B, lane 1) or following coinfection by BSE intracerebrally and by scrapie intraperitoneally (group 4) (Fig. 7B, lane 3). The results thus showed a clear relationship between intensity of labeling by SAF15 antibody and electrophoretic mobilities; samples with a higher apparent molecular mass, corresponding to a scrapie PrP res profile (groups 2, 5, and 6), are better recognized by SAF15 antibody than those showing a BSE PrP res profile.

FIG. 7.

Western blot analysis of mouse PrP res using RB1 antiserum (A) or SAF15 monoclonal antibody (B and C). Animal groups are defined in Table 1. (B) Lanes were loaded with comparable levels of PrP res, as determined by using RB1 antibody. (C) The first and third lanes were overloaded.

Overloading (5- to 10-fold) of samples with the lower molecular mass (samples with BSE PrP res profiles), however, showed labeling of all samples by SAF15 antibody, but no differences could then be detected in the PrP res fragment sizes between the different samples (Fig. 7C) compared to those previously observed using RB1 antibody (Fig. 7A).

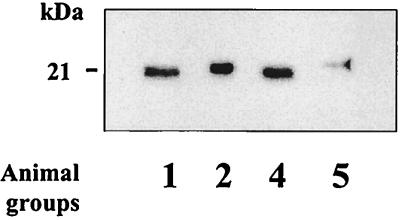

Studies of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with type 1 and type 2 PrP res.

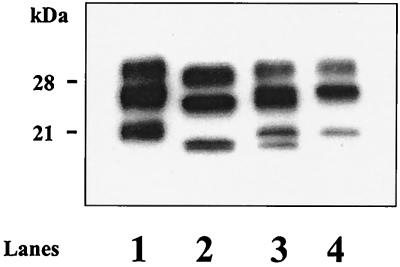

As a control for the ability of the methods used in this study to discriminate PrP res differing in electrophoretic mobility from the same tissue, we chose to seek Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with occurrence of both type 1 and type 2 PrP res in the same brain (31). Among a series of 32 Creutzfeld-Jakob disease cases which were studied by Western blotting, we found 2 in which both type 1 and type 2 PrP res could clearly be distinguished in cortical regions of the brain (Fig. 8, lane 3).

FIG. 8.

Western blot analysis of PrP res in humans with Creutzfeld-Jakob disease using 3F4 monoclonal antibody. Lane 1, type 1 PrP res; lane 2, type 2 PrP res; lane 3, co-occurrence of type 1 and type 2 PrP res in the cortex of the same patient; lane 4, brain region of the same patient showing only type 1 PrP res.

DISCUSSION

We report that following inoculation of mice by both scrapie and BSE strains previously adapted by serial transmission to mice, the PrP res glycoprofiles may appear to be undistinguishable from those found in mice infected with scrapie only (group 6), including mice infected by BSE and scrapie at the same time and by the same inoculation route (groups 2 and 3). These results were obtained using the C506M3 strain, which appeared, as previously described for other murine scrapie strains (25, 33; this study), to be easily distinguishable from BSE in mice. Characterization of the scrapie strains in this study fit with data previously described, generally reporting a specifically lower molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrP res following infection by the BSE agent (9, 10, 16, 17, 24). The glycoform ratios and the electrophoretic mobilities of unglycosylated PrP res following inoculation of both strains were similar to those found in scrapie-inoculated mice (group 6) when both BSE and scrapie were inoculated into the brain (groups 2 and 3) or when scrapie was inoculated intracerebrally and BSE intraperitoneally (group 5). The BSE profile was only observed when BSE alone was inoculated into the brain (groups 1 and 4), including mice inoculated by scrapie intraperitoneally at the same time (group 4).

These features were further characterized by evidence of differential reactivity of a monoclonal antibody (SAF15) that recognizes residues 78 to 91 of murine PrP compared to antiserum RB1, directed against residues 94 to 109. The epitope recognized by SAF15 antibody appeared to be digested by proteinase K in a larger proportion of PrP res molecules specifically in mice showing a BSE PrP res profile (groups 1 and 4). Distinct proteinase K cleavage sites between different strains have already been demonstrated in some experimental models, such as transmissible mink encephalopathy transmitted to hamster (30), and in some natural diseases, such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (1), by antigenic mapping (5) or by amino-terminal sequencing (1, 30). A subset of PrP res molecules is, however, recognized by SAF15 antibody in mice with the BSE PrP res profile (groups 1 and 4), in line with previous data showing ragged amino-terminal cleavage by proteinase K (18, 34).

It is also noteworthy that, in our studies, during the analysis of in vitro mixtures of brain homogenates from mice infected with BSE and C506M3, necessarily containing BSE infectivity at this stage, the BSE profile could be easily hidden by the addition of brain homogenate from scrapie-infected mice. Whatever the proportions of BSE and scrapie were in the mixtures, we could not separately identify scrapie and BSE PrP res, as in mice infected with both strains, but in some cases we observed an intermediate banding pattern (BSE-scrapie ratio, 20:1). In this respect, these results are in line with those described during coinfection by DY and HY hamster strains from transmissible mink encephalopathy, showing some cases with an intermediate banding pattern between the 19- and 21-kDa PrP res patterns specific for the two strains (4). However, in vivo, we did not find such an intermediate banding pattern, including after inoculation of a high load of BSE (ratio, 20:1), but a scrapie PrP res profile was then observed, consistent with a specific increase in scrapie-associated PrP res during in vivo replication. In contrast, we confirmed in two cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease that type 1 and type 2 PrP res with distinct fragment sizes could be detected separately in some brain regions of the same patients (13, 31). This result has been obtained both following direct detection of PrP res from brain homogenates (9) and in SAF preparations (3), whereas these two methods failed to distinguish scrapie and BSE PrP res in mice coinfected with both strains. However, with respect to such cases of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, the occurrence of both types of PrP res has been shown to be associated with different histopathological features (diffuse deposits or plaques) that may modify the accessibility of the amino-terminal end of PrP res (10, 31). The specific features of these two different abnormal PrPs which are accumulating in the brain of some patients at separate locations and with distinct morphological features could also be associated with their propensity to migrate separately, without mixing together, during SDS-PAGE. Whether these behaviors are associated with PrP alone or some other unidentified associated factors present in the brain is presently unknown.

It was previously shown that PrP res was more abundant in the brain of C506M3-inoculated C57BL/6 mice than in BSE-infected mice but that both strains, which otherwise had comparable incubation periods in C57BL/6 mice (about 180 days after intracerebral inoculation), were characterized by similar infectious titers at the terminal stage of the disease (26). More generally, the PrP res levels produced by a given strain appeared as a specific feature that could differentiate strains, without any apparent relationship with the duration of the incubation period (32). The PrP res levels detected in mice in our study indeed were higher in mice with a scrapie PrP res profile, as assessed in experiments in which equal quantities of brain material were compared between mice belonging to different experimental groups. The results of PrP res characterization are thus consistent with a pattern essentially determined by the more abundant PrP res species accumulating in the brain at the time of death of the animal. Following intraperitoneal inoculation of one of the strains, the level of PrP res produced by this particular strain in the brain is expected to be low at the time that mice die if they were inoculated at the same time with the other strain by the intracerebral route (26), leading to a PrP res pattern essentially determined by this intracerebrally inoculated strain. Following intracerebral inoculation of both strains, the proportion of BSE-associated PrP res may be too low to be detected. However, some molecular changes of this abnormal PrP itself during its accumulation together with scrapie-associated PrP res cannot be excluded.

These results were obtained following inoculation of mouse-adapted strains. The behavior of a mixture of scrapie and BSE from ruminant isolates during a primary passage in the mouse is unknown. With respect to PrP res accumulation in brain, some experiments have reported undetectable levels of PrP res in mice infected with BSE from cattle, at least in a mouse line (C57BL/6) (27). On the other hand, it was reported that the success rate of transmission of natural scrapie isolates in mice varied enormously (6).

Further experiments by transmission into mice and characterization of the distribution of brain lesions are required to characterize the infectious agent detected in the brain of mice infected with both scrapie and BSE strains. It cannot be excluded that during coinfection, the replication of the BSE agent had been hampered by that of scrapie. Competition between two strains has already been described, one inoculated “slow” strain being able to prevent infection by another more rapid strain that was inoculated later in the same animal, but competition only occurred when the two strains were inoculated at sufficient time intervals (11, 12, 22). However, in our experiments, the two strains were characterized by similar incubation periods and had been inoculated simultaneously. Furthermore, in some of our experiments, a higher load of BSE brain homogenate in the inoculum compared to scrapie has been used to challenge mice with both strains by the intracerebral route (group 3) in order to evaluate the possibility of competition between strains at the very early phase of infection. The PrP res profiles at the terminal stage of the disease were again similar to those found in mice infected with scrapie only (group 6). Such competition could also occur when both strains are inoculated, each of them by different routes (intracerebral or intraperitoneal), the intraperitoneal inoculation route being associated with a longer incubation period and a delayed accumulation of PrP res in brain. However, the profile of brain PrP res following intracerebral inoculation of one strain was not significantly modified following simultaneous inoculation of the other strain intraperitoneally.

Separation from a mixture of agent strains through serial passage in hamster that led to strains with distinct transmissibility to mice has been described, the dose of each strain being likely able to influence the outcome of transmission (23). In a study of transmissible mink encephalopathy transmitted to a hamster, it has also been shown that two different PrP res, 19 and 21 kDa, corresponding to two different strains (DY and HY, respectively), could be selected from a mixture through serial passage in hamsters according to the brain dilution inoculum used (4). Adaptation and selection of the strain with the shortest incubation period (HY) could occur after serial intraspecies passage, even though it was initially present at lower doses. Following coinfection by both HY and DY strains, a reversion from the DY to the HY strain phenotype could be observed when hamsters were coinfected with brain dilutions of 10−7 and 10−2, respectively. The PrP res strain-specific patterns preceded the stabilization of strain phenotypes, whose emergence could be predicted.

Regarding the molecular features of PrP res in natural scrapie, conflicting results have been reported (3, 17, 19, 29, 35). It was recently reported that a single experimental scrapie strain, CH1641, isolated from a natural scrapie case in 1971 in the United Kingdom (14), had similar molecular features to those found in experimentally BSE-infected sheep, particularly with respect to the identical fragment sizes of the unglycosylated PrP res (19). No other natural scrapie case has ever displayed features identical to those found in experimentally BSE-infected sheep (2, 17, 19). The propensity to accumulate PrP res in brain in sheep infected with BSE, compared to scrapie, is unknown, but in some cases Western blot analysis failed to detect PrP res in experimentally BSE-infected sheep (17). Whereas our experiments involved mice infected with a mouse-adapted strain, the outcome of infection in sheep infected by both BSE and scrapie strains may also be different. However, it was reported that different scrapie strains could be isolated from a single natural scrapie case by transmission in mice (6). Mixtures of PrP res bearing distinct molecular and pathogenic properties could be present in individual sheep as well, which could explain at least partly the homogeneous PrP res profiles found in a number of scrapie cases (3, 35). Some mouse-adapted strains with different electrophoretic profiles, such as ME7 and 22A, indeed originated from the same original source of natural scrapie (33). From such mixtures, a particular strain with distinct molecular and pathogenic features, and especially transmissibility, could emerge after some selection during their transmission, as this possibly happened during recycling of the BSE agent in contaminated protein supplements from ruminants.

Our results demonstrate that identification of a strain by molecular analysis and mouse transmission studies may in some respects be misleading, since, if a mixture of several strains is present, the strains associated with higher levels of PrP res may hide other strains present at lower levels.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully thank A. Kato and D. Canal for their excellent technical help and S. Philippe for statistical analysis of the data.

This work was partly funded by grants from the European Commission (proposal PL 97 3305) and the Programme National de Recherches sur les ESST et les Prions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aucouturier P, Kascsak R J, Frangione B, Wisniewski T. Biochemical and conformational variability of human prion strains in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob. Neurosci Lett. 1999;274:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00659-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron T G M, Madec J-Y, Calavas D, Richard Y, Barillet F. Comparison of French natural scrapie isolates with bovine spongiform encephalopathy and experimental scrapie infected sheep. Neurosci Lett. 2000;284:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron T G M, Madec J-Y, Calavas D. Similar signature of the prion protein in natural sheep scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy-linked diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3701–3704. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3701-3704.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartz J C, Bessen R A, McKenzie D, Marsh R F, Aiken J M. Adaptation and selection of prion protein strain conformations following interspecies transmission of transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Virol. 2000;74:5542–5547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5542-5547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bessen R A, Marsh R F. Biochemical and physical properties of the prion protein from two strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. J Virol. 1992;66:2096–2101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2096-2101.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce M. Strain typing studies of scrapie and BSE. In: Baker H, Ridley R M, Totowa N J, editors. Prion diseases. Clifton, N.J: Humana Press; 1996. pp. 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce M E, Will R G, Ironside J W, McConnell I, Drummond D, Suttle A, McCardle L, Chree A, Hope J, Birkett C, Cousens S, Fraser H, Bostock C J. Transmission to mice indicate that “new variant” CJD is caused by the BSE agent. Nature. 1997;389:498–501. doi: 10.1038/39057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler D. Doubts over ability to monitor risks of BSE spread to sheep. Nature. 1998;395:6–7. doi: 10.1038/25573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collinge J, Sidle K C L, Meads J, Ironside J, Hill A F. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ‘new variant’ CJD. Nature. 1996;383:685–690. doi: 10.1038/383685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demart S, Fournier J G, Creminon C, Frobert Y, Lamoury F, Marce D, Lasmezas C, Dormont D, Grassi J, Deslys J P. New insight into abnormal prion protein using monoclonal antibodies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:652–657. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson A G, Fraser H, McConnell I, Outram G W, Sales D I, Taylor D M. Extraneural competition between different scrapie agents leading to loss of infectivity. Nature. 1975;253:556. doi: 10.1038/253556a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson A G, Fraser H, Meikle V M H, Outram G W. Competition between different scrapie agents in mice. Nat New Biol. 1972;237:244–245. doi: 10.1038/newbio237244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickinson D W, Brown P. Multiple prion types in the same brain. Is a molecular diagnosis of CJD possible? Neurology. 1999;53:1903–1904. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster J D, Dickinson A G. The unusual properties of CH1641, a sheep-passaged isolate of scrapie. Vet Rec. 1988;123:5–8. doi: 10.1136/vr.123.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser H, Mc Connell I, Wells G A H, Dawson M. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy to mice. Vet Rec. 1988;123:472–472. doi: 10.1136/vr.123.18.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill A, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Sidle K C L, Gowland I, Collinge J. The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature. 1997;389:448–450. doi: 10.1038/38925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill A F, Sidle K C L, Joiner S, Keyes P, Martin T C, Dawson M, Collinge J. Molecular screening of sheep for bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Neurosci Lett. 1998;255:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hope J, Multhaup G, Reekie L J D, Kimberlin R H, Beyreuther K. Molecular pathology of scrapie-associated fibril protein (PrP) in mouse brain affected by the ME7 strain of scrapie. Eur J Biochem. 1988;172:271–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hope J, Wood S C E R, Birkett C R, Chong A, Bruce M E, Cairns D, Goldmann W, Hunter N, Bostock C J. Molecular analysis of ovine prion protein identifies similarities between BSE and an experimental isolate of natural scrapie, CH1641. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1–4. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kascsak R, Rubenstein R, Merz P A, Carp R, Robakis N K, Wisniewski H M, Diringer H. Immunological comparison of scrapie-associated fibrils isolated from animals infected with four different scrapie strains. J Virol. 1986;59:676–683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.3.676-683.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kascsak R J, Rubenstein R, Merz P A, Tonna Demasi M, Fersko R, Carp R I, Wisniewski H M, Diringer H. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J Virol. 1987;61:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3688-3693.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimberlin R H, Walker C A. Competition between strains of scrapie depends on the blocking agent being infectious. Intervirology. 1985;23:74–81. doi: 10.1159/000149588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimberlin R H, Walker C A. Evidence that the transmission of one source of scrapie agent to hamsters involves separation of agent strains from a mixture. J Gen Virol. 1978;39:487–496. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-39-3-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuczius T, Groschup M H. Differences in proteinase K resistance and neuronal deposition of abnormal prion proteins characterize bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and scrapie strains. Mol Med. 1999;5:406–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuczius T, Haist I, Groschup M H. Molecular analysis of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie strain variation. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:693–699. doi: 10.1086/515337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasmézas C I, Deslys J P, Demaimay R, Adjou K T, Hauw J J, Dormont D. Strain specific and common pathogenic events in murine models of scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1601–1609. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasmézas C I, Deslys J-P, Robain O, Jaegly A, Beringue V, Peyrin J-M, Fournier J-G, Hauw J-J, Rossier J, Dormont D. Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science. 1996;275:402–405. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madec J-Y, Belli P, Calavas D, Baron T. Efficiency of Western blotting for the specific immunodetection of proteinase K-resistant prion protein in BSE diagnosis in France. Vet Rec. 2000;146:74–76. doi: 10.1136/vr.146.3.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madec J-Y, Groschup M H, Calavas D, Junghans F, Baron T. Protease-resistant prion protein in brain and lymphoid organs of sheep within a naturally scrapie-infected flock. Microb Pathog. 2000;28:353–362. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh R F, Bessen R A. Physicochemical and biological characterizations of distinct strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1994;343:413–414. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puoti G, Giaccone G, Rossi G, Canciani B, Bugiani O, Tagliavini F. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: co-occurrence of different types of PrP Sc in the same brain. Neurology. 1999;53:2173–2176. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safar J, Wille H, Itrri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, Cohen F E, Prusiner S B. Eight prion strains have PrPSc molecules with different conformations. Nat Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somerville R A, Chong A, Mulqueen O U, Birkett C R, Wood S C E R, Hope J. Biochemical typing of scrapie strains (with response from J. Collinge et al.) Nature. 1997;386:564. doi: 10.1038/386564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stahl N, Baldwin M A, Teplow D B, Hood L, Gibson B W, Burlingame A L, Prusiner S B. Structural studies of the scrapie prion protein using mass spectrometry and amino acid sequencing. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1991–2002. doi: 10.1021/bi00059a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweeney T, Kuczius T, McElroy M, Gomerez Parada M, Groschup M. Molecular analysis of Irish sheep scrapie cases. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1621–1627. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-6-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Telling C G, Parchi P, De Armond S J, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Gabizon R, Mastrianni J, Lugaresi E, Gambetti P, Prusiner S B. Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science. 1996;274:2079–2082. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]