Abstract

Highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza (HPAI H5N1) viruses occasionally infect, but typically do not transmit, in mammals. In the spring of 2024, an unprecedented outbreak of HPAI H5N1 in bovine herds occurred in the USA, with virus spread within and between herds, infections in poultry and cats, and spillover into humans, collectively indicating an increased public health risk1–4. Here we characterize an HPAI H5N1 virus isolated from infected cow milk in mice and ferrets. Like other HPAI H5N1 viruses, the bovine H5N1 virus spread systemically, including to the mammary glands of both species, however, this tropism was also observed for an older HPAI H5N1 virus isolate. Bovine HPAI H5N1 virus bound to sialic acids expressed in human upper airways and inefficiently transmitted to exposed ferrets (one of four exposed ferrets seroconverted without virus detection). Bovine HPAI H5N1 virus thus possesses features that may facilitate infection and transmission in mammals.

Subject terms: Influenza virus, Viral pathogenesis, Viral transmission

HPAI H5N1 virus isolated from infected cow milk is characterized in mice and ferrets, was inefficiently transmitted in ferrets, and bound to sialic acids expressed in human upper airways, showing features that may facilitate infection in mammals.

Main

After reports of unexplained symptoms including reduced milk production in lactating dairy cattle in Texas, USA, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus of the H5N1 subtype was reported in milk and nasal wash samples of an infected cow on 25 March 2024, marking the first documented outbreak of HPAI H5N1 viruses in cattle. By 30 May 2024, the United States Department of Agriculture had confirmed 69 infected bovine herds in nine states1, with spread being attributed to cattle movement between states. Virus transmission among lactating dairy cattle may occur through contaminated milking equipment with virus infection through the udder, but this has not been confirmed. HPAI H5N1 viruses rarely infect mammals and typically do not transmit among them. The bovine H5N1 virus outbreak, along with reports of three HPAI H5N1 virus-infected dairy farm workers (presenting with conjunctivitis4 or respiratory symptoms3), fatal HPAI H5N1 virus infections of cats on affected farms and spillover to poultry highlight the public health risk of the current HPAI H5N1 virus outbreak in cattle.

The bovine H5N1 viruses isolated from cattle are closely related to HPAI H5N1 viruses circulating in North American wild birds5–8. These viruses belong to HA clade 2.3.4.4b and were introduced into North America in late 2021 through the Transatlantic flyway from Europe. Frequent reassortment with North American low pathogenic avian influenza viruses has resulted in many genotypes that have spread throughout the American continent, causing sizeable outbreaks in wild birds and sea mammals, some with high mortality rates and suspected virus transmission among sea mammals9,10.

The basic characteristics of the bovine H5N1 viruses are unknown. Accordingly, here we tested a bovine H5N1 virus isolated from the milk of an infected dairy cow in New Mexico, USA, for replication and pathogenicity in mice and ferrets, two mammalian animal models routinely used for influenza A virus studies and for respiratory droplet transmission in ferrets. We also tested the vertical transmission of bovine HPAI H5N1 virus from lactating mice to their pups. Finally, we compared receptor specificity, an important factor for host range restriction, of bovine and avian H5N1 viruses and a seasonal human H1N1 influenza virus.

Pathogenicity after oral ingestion

To evaluate the public health risk of H5N1 virus-containing milk, we previously demonstrated that oral consumption of milk from an HPAI H5N1-infected cow led to rapid induction of disease symptoms (by day 1 postinfection) and virus dissemination to respiratory and non-respiratory organs (by day 4 postinfection) in BALB/cJ mice5. To assess disease caused by oral inoculation in more detail, we repeated this experiment with smaller inoculation volumes of milk from infected cattle (25, 10, 5 and 1 μl per mouse; corresponding dosages 3.25 × 103 plaque-forming units (PFU) per 25 μl; 1.3 × 103 PFU per 10 μl; 6.5 × 102 PFU per 5 μl and 1.3 × 102 PFU per 1 μl; ten mice per inoculation group). For five mice, we monitored body weight loss and survival daily over 14 days, and in the other five, we determined virus titres in the lung, nasal turbinate and brain (the last served as a proxy for virus dissemination to non-respiratory sites) on day 6 postinfection. Some mice inoculated with 25 or 10 μl of milk showed substantial weight loss (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1) and a subset succumbed to the infection (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, in mice euthanized on day 6 postinfection, high virus titres were observed in nasal turbinate, lung and brain tissues (Fig. 1c; no statistically significant differences in nasal turbinate, brain or lung titres were observed between the 25 and 10 μl inoculation groups). By contrast, mice inoculated with 25 μl of milk from a healthy cow (mock) showed no symptoms of disease (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 1). In mice inoculated with 5 μl of milk, disease was less apparent and virus replication in respiratory tissues and brain was sporadic. No disease or virus replication was observed in animals inoculated with 1 μl of milk. A haemagglutination inhibition assay of serum collected from all mice that survived inoculation with any volume of infected cow’s milk revealed no seroconversion in any of the animals.

Fig. 1. Pathogenicity in mice orally inoculated with milk from an HPAI H5N1 virus-infected cow.

Female BALB/cJ mice (8 weeks old) were lightly anaesthetized and orally inoculated with 25 μl of milk from a healthy cow (‘mock’; n = 5 biologically independent animals per inoculation volume) or different volumes (25, 10, 5 or 1 μl containing 3.25 × 103 PFU per 25 μl, 1.3 × 103 PFU per 10 μl, 6.5 × 102 PFU per 5 μl and 1.3 × 102 PFU per 1 μl; n = 10 biologically independent animals per inoculation volume) of milk from a dairy cow infected with HPAI H5N1 virus. a,b, For five mice per inoculation volume, body weights (a) and survival (b) were monitored daily for 14 days. In a, datapoints represent mean values for each inoculation volume at each timepoint and error is represented by standard deviation. c, The other five mice in each inoculation group were euthanized at 6 days postinfection and nasal turbinate (NT), lung or brain tissues were collected for virus titration in MDCK cells. In c, the floating bars show the median titre for each tissue of each inoculation group and variability is represented by the range. When virus was not detected in a tissue, an arbitrary value below the limit of detection was assigned to enable visualization of the datapoint on the graph. Non-parametric, two-tailed Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare titres of the 25 and 10 μl inoculation groups and no significant differences were found (NT, P = 0.4603; lung, P = 0.5397; brain, P = 0.3016). PFU g−1, PFU per gram of tissue.

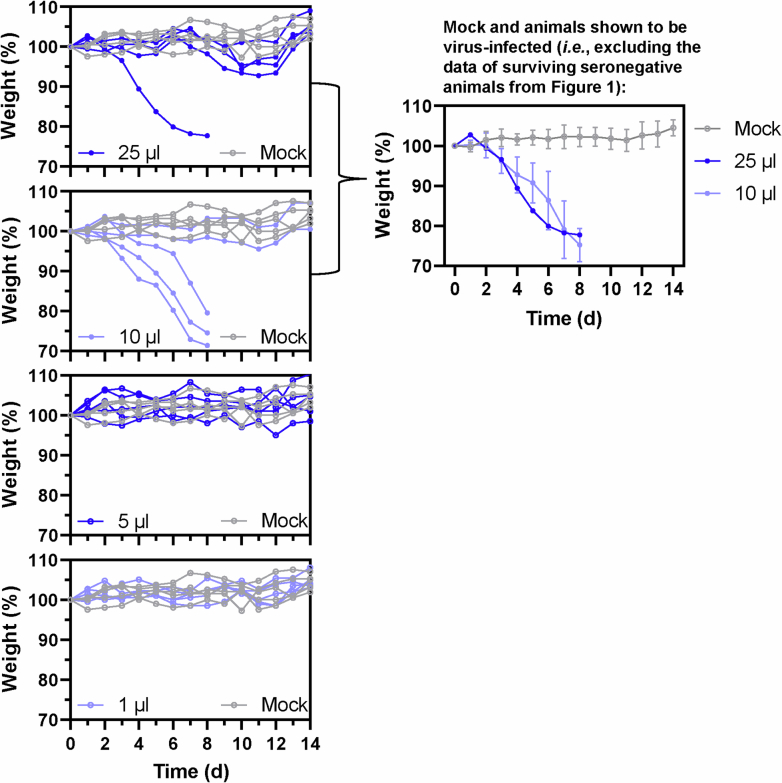

Extended Data Fig. 1. Individual body weight profiles of mice orally inoculated with milk from an infected dairy cow.

Individual body weight profiles for the mice shown in Fig. 1a are shown in the four panels at the left (n = 5 biologically independent animals per inoculation volume). Mock-infected body weights, shown in all four panels, are derived from the same mice. In the panel at the right, body weights are shown for mock-infected mice, and for mice that exhibited > 10% body weight loss after inoculation with milk from an infected dairy cow. For the mock-infected mice and mice inoculated with 10 μl of infected milk, the values are the means of 5 or 3 mice, respectively, while a single mouse body weight profile is shown for the 25 μl-infected milk inoculation group. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

Pathogenicity after intranasal infection

Influenza A viruses typically infect humans by the respiratory route. To assess pathogenicity in mice after intranasal (that is, respiratory) exposure, we determined the mouse lethal dose 50 (MLD50) and tissue tropism of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (‘Cow-H5N1’). Female BALB/cJ mice were inoculated with tenfold serial dilutions (100 to 106 PFU, five animals per dose) of Cow-H5N1, and body weight (Fig. 2a) and survival (Fig. 2b) were monitored daily for 15 days. All mice infected with greater than or equal to 103 PFU of virus succumbed to the infection, whereas some mice infected with 102 or 101 PFU survived (Fig. 2b). No body weight loss or death was observed among mice infected with 100 PFU of virus (Fig. 2a). The resulting MLD50 of 31.6 PFU is comparable to that of two different clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI H5N1 mink viruses isolated during an outbreak in Spain in 2022 (A/mink/Spain/22VIR12774-13_3869-2/2022, MLD50 of 48.1 PFU; A/mink/Spain/22VIR12774-14_3869-3/2022, MLD50 30 PFU), but slightly higher than that of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (‘VN1203-H5N1’, MLD50 2.2 PFU)11, that is, a typical avian H5N1 virus isolated from a human.

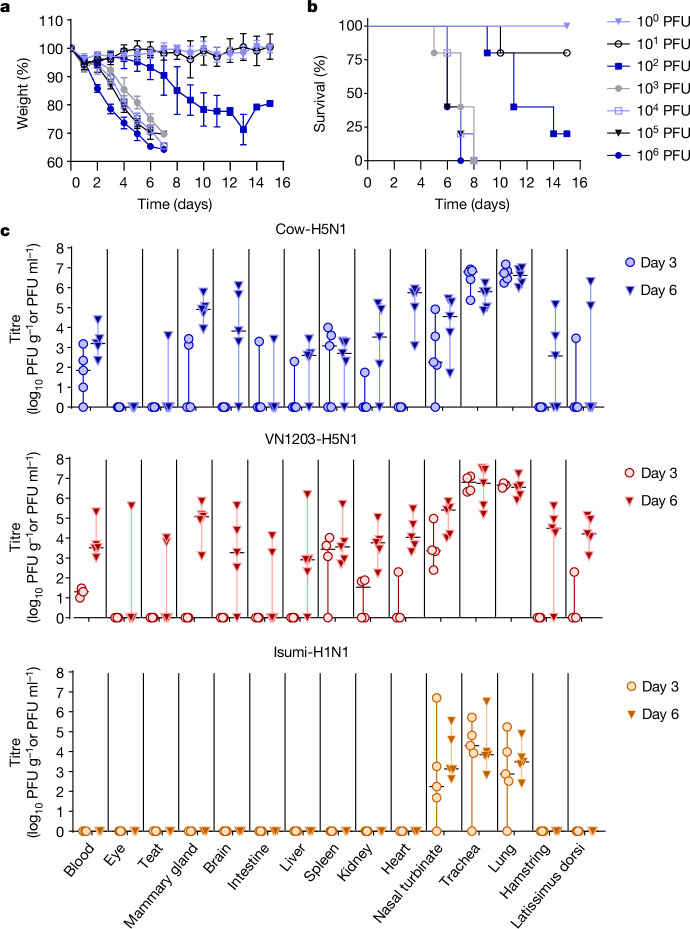

Fig. 2. Pathogenicity and tissue tropism in mice intranasally inoculated with bovine H5N1 virus.

a,b, BALB/cJ mice (7 weeks old, n = 5 biologically independent animals per dosage) were deeply anaesthetized and intranasally inoculated with tenfold serial dilutions of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1) in 50 μl of PBS. Body weight (a) and survival (b) were monitored daily for 15 days. In a, the error bars represent the standard deviation. c, BALB/cJ mice (10 weeks old, n = 10 biologically independent animals per virus) were deeply anaesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 103 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; ‘Cow-H5N1’), A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1; ‘VN1203-H5N1’) or A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018 (H1N1; ‘Isumi-H1N1’) in 50 μl of PBS. At 3 and 6 days postinfection, five mice infected with Cow-H5N1 or Isumi-H1N1 were euthanized and tissues were collected for plaque assays in MDCK cells. For VN1203-H5N1 infections, four mice were euthanized at the day 3 timepoint as one mouse succumbed at day 1 postinfection, and five mice were euthanized at the day 6 timepoint. In c, the floating bars show the median titre for each tissue of each inoculation group and variability is represented by the range. When virus was not detected in a tissue, an arbitrary value below the limit of detection was assigned to enable visualization of the datapoint on the graph. PFU ml−1, PFU per millilitre.

To examine tissue tropism after intranasal infection, we inoculated female BALB/cJ mice with 103 PFU of Cow-H5N1, VN1203-H5N1 or a pandemic H1N1 influenza virus (A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018, ‘Isumi-H1N1’)12 for comparison (ten mice per group). Three and 6 days later, five mice in each group were euthanized, tissues (blood, eye, teat, mammary gland, brain, intestine, liver, spleen, kidney, heart, nasal turbinate, trachea, lung, hamstring and latissimus dorsi) were collected and virus titres were determined by performing plaque assays in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (Fig. 2c). For Cow-H5N1 and VN1203-H5N1, virus titres on day 6 were generally higher than those on day 3. Both viruses caused systemic infections with high titres in respiratory and non-respiratory organs, including the mammary glands, teats and muscle tissues of the leg (hamstring) and back (latissimus dorsi). Virus was also found in the eye of a single mouse infected with VN1203-H5N1 (Fig. 2c), and in a similar experiment (performed under the same conditions, but without Isumi-H1N1 infections or collection of blood or muscle tissue), we found both Cow-H5N1 and VN1203-H5N1 in eyes (Extended Data Fig. 2). The consistent detection of HPAI H5N1 virus in the mammary glands and muscle tissues, and its sporadic detection in the eyes of mice is consistent with reports of HPAI H5N1 virus in the mammary glands2,13 and muscle tissues of cows14 and with reports of conjunctivitis and respiratory symptoms in humans infected with an HPAI H5N1 virus related to the outbreak in cattle3,4. In contrast to Cow-H5N1 and VN1203-H5N1, the Isumi-H1N1 virus was detected only in the respiratory tissues of mice (Fig. 2c). As Cow-H5N1 and VN1203-H5N1 (but not Isumi-H1N1) were also found in the blood, it is possible that viral spread to non-respiratory tissues occurred through viremia.

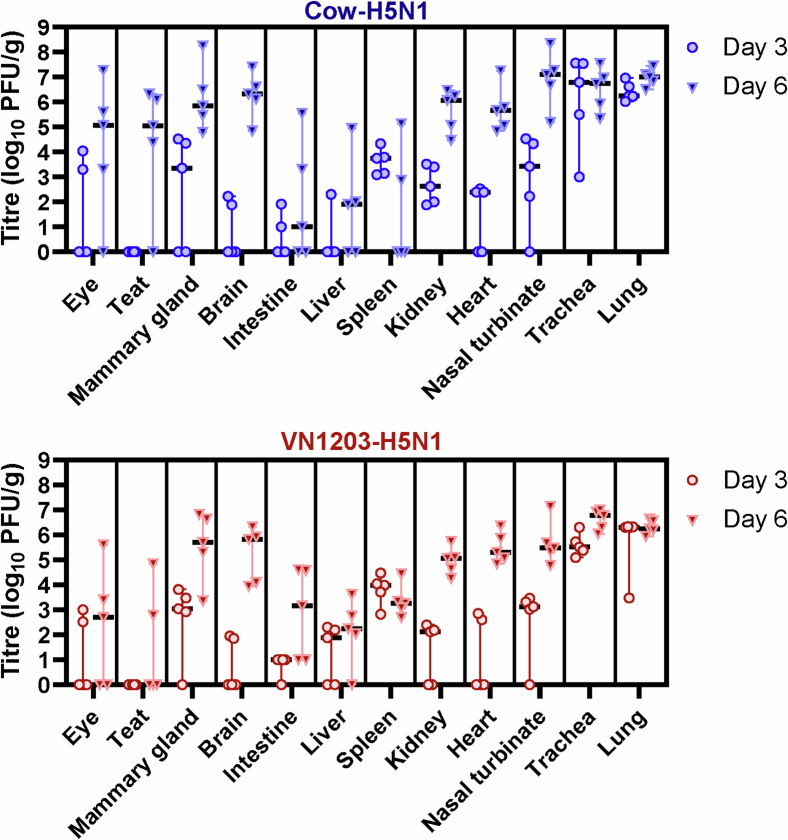

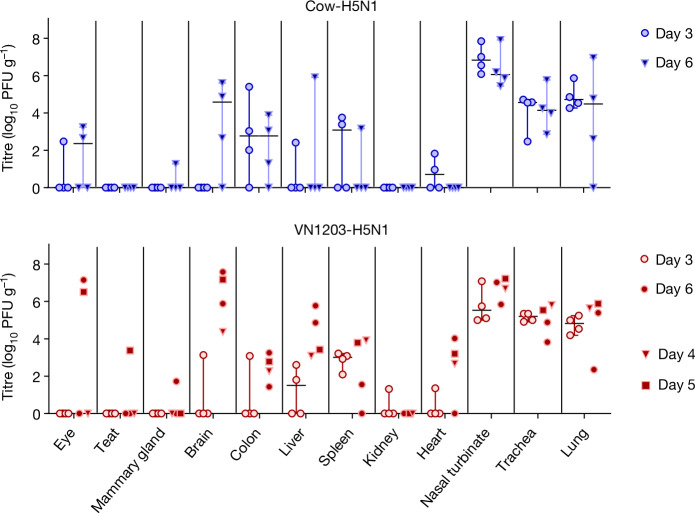

Extended Data Fig. 2. Tissue tropism in mice intranasally inoculated with bovine H5N1 virus, a replicate experiment.

BALB/cJ mice (7 weeks old, n = 10 biologically independent animals per virus) were deeply anaesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 103 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; ‘Cow-H5N1’) or A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1; ‘VN1203-H5N1’) in 50 μl of PBS. At 3 and 6 days post-infection, five mice in each group were euthanised and tissues were collected for plaque assays in MDCK cells. In the figure panels, the floating bars show the median titre for each tissue of each inoculation group and variability is represented by the range. When virus was not detected in a tissue, an arbitrary value below the limit of detection was assigned to enable visualization of the datapoint on the graph. PFU/g, plaque-forming units per gram of tissue.

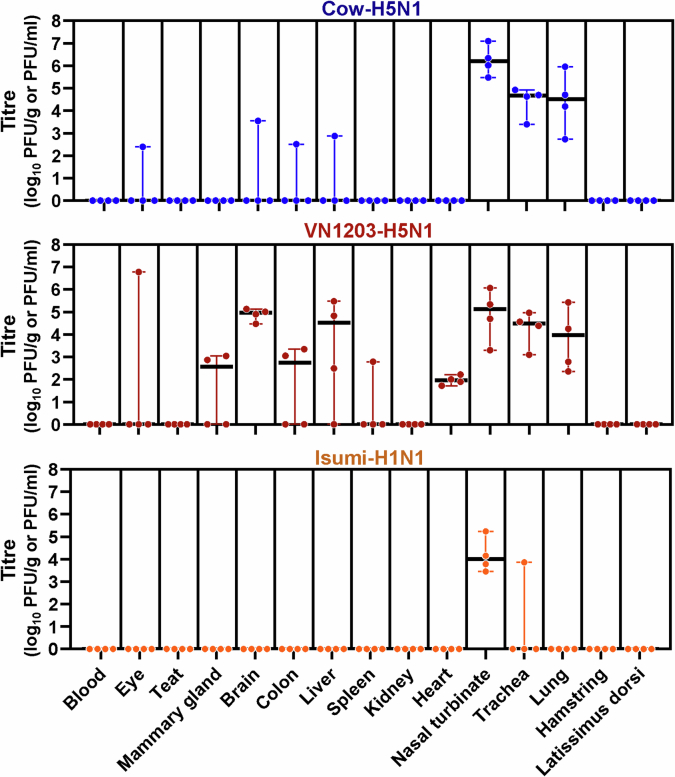

We next intranasally infected female ferrets with 106 PFU of Cow-H5N1 or VN1203-H5N1 (four animals per virus) and examined tissue tropism at days 3 and 6 postinfection. Ferrets infected with either virus showed elevated body temperatures and body weight loss after infection (Extended Data Fig. 3), consistent with clinical disease. As in mice, both viruses replicated to high titres in the upper and lower respiratory tracts, and spread to non-respiratory organs (including eyes, brain, colon, liver, spleen, kidney and/or heart) in some of the infected ferrets (Fig. 3). Virus was also detected in the mammary glands and teats but only in a few animals in each group. No virus was detected in the blood or muscle tissues of ferrets infected with Cow-H5N1, VN1203-H5N1 or Isumi-H1N1 in a separate experiment (Extended Data Fig. 4). At present, it is unclear whether the lack of virus in the blood and muscle tissues of ferrets is due to differences in the animals or due to the inability of HPAI H5N1 viruses to spread to blood and/or muscle tissues in the ferret model. Nonetheless, these findings are consistent with other reports of the systemic spread of related HPAI H5N1 viruses in ferrets, including limited spread to the ocular tissues15,16; and further support the possibility that mammary gland and/or teat tropism are features of mammalian infection with HPAI H5N1 viruses, and not a specific characteristic of HPAI H5N1 isolated from lactating dairy cattle.

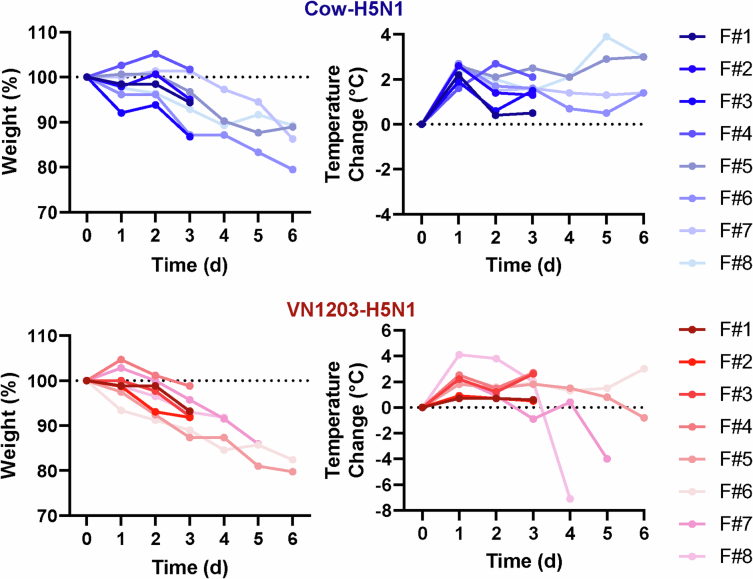

Extended Data Fig. 3. Clinical data associated with ferrets used to assess tissue tropism.

For the same ferrets shown in Fig. 3 (n = 8 biologically independent animals per virus), daily body weights and body temperatures are given. For the VN1203-H5N1-infected group day 6 timepoint, two animals succumbed to their infections prior to the planned euthanasia date (ferret 7 at day 5 and ferret 8 at day 4 post-infection). The dotted lines indicate starting weights or body temperatures. F, ferret.

Fig. 3. Tissue tropism in ferrets intranasally inoculated with bovine H5N1 virus.

Ferrets (4–6 months old, n = 8 biologically independent animals per virus) were deeply anaesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 106 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; ‘Cow-H5N1’) or A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1; ‘VN1203-H5N1’) in 500 μl of PBS. At 3 and 6 days postinfection, four ferrets infected with Cow-H5N1 were euthanized and tissues were collected for plaque assays in MDCK cells. For VN1203-H5N1 infections, four ferrets were euthanized at the day 3 timepoint, one ferret succumbed to its infection on day 4, one succumbed on day 5 and two others were euthanized at the day 6 timepoint. Tissues from animals that succumbed on day 4 or day 5 postinfection are represented by triangles and squares, respectively. In the figure panels, the floating bars show the median titre for each tissue of each inoculation group and variability is represented by the range. For VN1203-H5N1-infected animals, medians and ranges are shown only for the day 3 timepoint because some animals in the day 6 timepoint group succumbed earlier. When virus was not detected in a tissue, an arbitrary value below the limit of detection was assigned to enable visualization of the datapoint on the graph.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Tissue tropism in ferrets intranasally inoculated with bovine H5N1, a replicate experiment.

Ferrets (4—6 months old, n = 4 biologically independent animals per virus) were deeply anaesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 106 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; ‘Cow-H5N1’), A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1; ‘VN1203-H5N1’), or A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018 (H1N1; ‘Isumi-H1N1’) in 500 μl of PBS. At 6 days post-infection, ferrets were euthanised and tissues were collected for plaque assays in MDCK cells. In the figure panels, the floating bars show the median titre for each tissue of each inoculation group and variability is represented by the range. When virus was not detected in a tissue, an arbitrary value below the limit of detection was assigned to enable visualization of the datapoint on the graph. PFU/g, plaque-forming units per gram of tissue; PFU/ml, plaque forming units per millilitre.

Together, our pathogenicity studies in mice and ferrets revealed that (1) HPAI H5N1 derived from lactating dairy cattle may induce severe disease after oral ingestion or respiratory infection; and (2) infection by either the oral or respiratory route can lead to systemic spread of virus to non-respiratory tissues including the eye, mammary gland, teat and/or muscle.

Transmission from lactating mice to pups

HPAI H5N1 viruses have been detected in the milk of lactating dairy cattle and oral ingestion of milk can lead to severe disease in the mouse model (ref. 5 and Fig. 1). In our next set of experiments, we tested whether bovine H5N1 virus could be transferred from infected, lactating mice to uninfected, suckling offspring (that is, pups) or adult contact animals. Five to 7 days after giving birth, lactating females were intranasally inoculated with 100 PFU of Cow-H5N1, and then either reunited with their pups or placed into cages with non-lactating female adults. At days 4, 7 and 9 postinfection, mice were euthanized and organs were collected for virus titration.

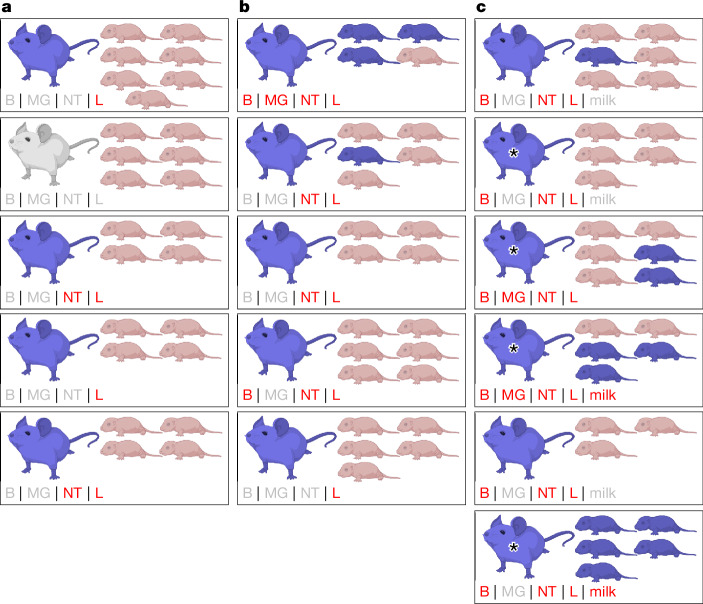

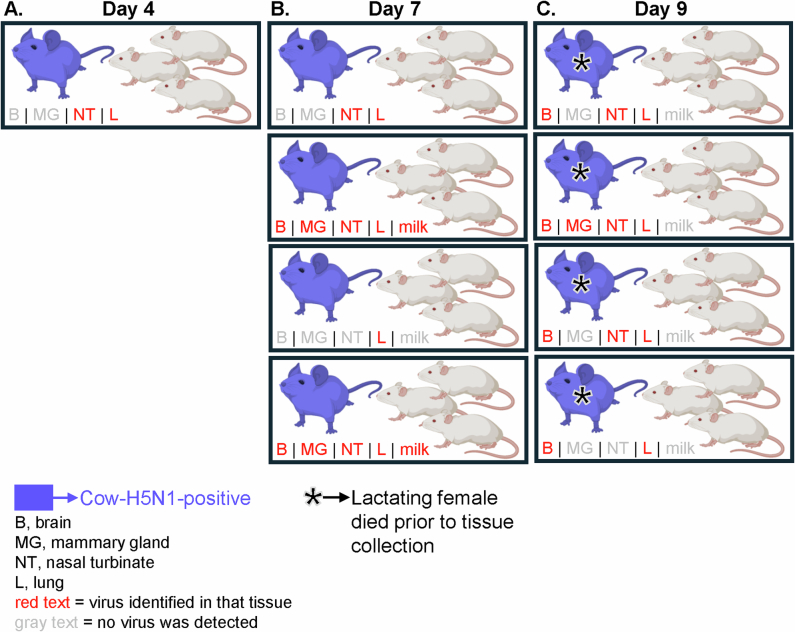

At day 4 postinfection, five of six lactating females showed virus replication in respiratory tissues, but no virus was detected in the brain or mammary glands (Fig. 4a). None of the 25 pups (distributed across five litters) showed any detectable virus in the brain, lung or intestines; and none of the three adult contacts (cohoused with a single lactating female) showed any detectable virus in nasal turbinate, lung or brain (Extended Data Fig. 5). At day 7 postinfection, lactating females (nine in total) showed higher virus loads in lung and nasal turbinate, and three lactating females (one cohoused with pups and two with adult contacts) also had virus in the brain and mammary gland (Fig. 4b; note, two lactating females cohoused with adult contacts also had virus in their milk). Of the 24 pups (distributed across five litters), four pups from two litters became infected (three of the four infected pups were from a litter of a lactating female that had virus spread to the brain and mammary gland), but again, no virus was detected in any of the adult contact animals (Extended Data Fig. 5). At day 9 postinfection, virus was detected in the respiratory tissues and brain of all lactating females, as well as in the mammary glands or milk of three of the six lactating females (Fig. 4c). At this timepoint, 11 pups (of 30 pups distributed across six litters) became infected (four of six litters had at least one infected pup); and in three of the litters with infected pups, we also detected virus in the mammary gland and/or milk of their lactating mothers. As observed on day 4 and day 7, none of the adult contact animals on day 9 had detectable virus in the examined tissues (Extended Data Fig. 5). Therefore, Cow-H5N1 can be transmitted from lactating females to their pups, but not to adult animals with which they have direct contact. Because virus was detected in the mammary glands and milk of most of the lactating mice and the pups had direct exposure to the infected milk, it is conceivable that mother-to-pup vertical transmission occurred through the milk. Of note, vertical transmission was observed in the absence of virus detection in the mammary glands or milk of the lactating mother in two instances (one animal each at day 7 and day 9 postinfection, Fig. 4b,c). We propose that this may be due to non-uniform dissemination of Cow-H5N1 to the mammary glands.

Fig. 4. Transmission of bovine H5N1 virus from lactating female mice to offspring.

Lactating female BALB/c mice (10–12 weeks old) were deeply anaesthetized, intranasally inoculated with 102 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; ‘Cow-H5N1’) and then reunited with their suckling offspring (‘pups’). a–c, At day 4 (n = 5 biologically independent animals) (a), day 7 (n = 5 biologically independent animals) (b) or day 9 (n = 6 biologically independent animals) (c) postinfection, lactating females and their pups were euthanized and tissues were collected for plaque assays in MDCK cells. Milk was collected from five of six lactating females on day 9 postinfection only, as indicated, and tested by plaque assays in MDCK cells. In the figure, each box represents one cage with a lactating female and her pups. Animals for which Cow-H5N1 virus was detected in at least one tissue are coloured blue. At the lower left corner of each box, the status of each tissue or milk sample collected from the lactating females is indicated. Grey text indicates that no virus was detected, and red text indicates that virus was detected. Tissue abbreviations are: B, brain; MG, mammary gland; NT, nasal turbinate and L, lung. For the day 9 timepoint group, some of the lactating females succumbed to their infections before the designated endpoints, but within 12 h of tissue collection (indicated by asterisks). Tissues were collected from these mice and analysed along with the others. Created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Transmission of bovine H5N1 virus from lactating female mice to adult contacts.

Lactating female BALB/cJ mice (10—12 weeks old) were deeply anaesthetized, intranasally inoculated with 102 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; ‘Cow-H5N1’), and then cohoused with adult female BALB/cJ mice (n = 3 biologically independent animals per lactating female). At day 4 (n = 1 biologically independent lactating female) (A), day 7 (n = 4 biologically independent lactating females) (B), or day 9 (n = 4 biologically independent lactating females) (C) post-infection, lactating females and adult contacts were euthanised and tissues were collected for plaque assays in MDCK cells. Milk was collected from 3 of 4 lactating females on day 7 post-infection and all four lactating females on day 9 post-infection and tested by plaque assays in MDCK cells. In the figure, each box represents one cage with a lactating female and the associated adult contact animals. Animals for which Cow-H5N1 was detected in at least one tissue are coloured blue. At the lower left corner of each box, the status of each tissue or milk sample collected from the lactating females is indicated. Gray text indicates that no virus was detected, whereas red text indicates that virus was detected. Tissue abbreviations are given at the lower left of the figure. Created with BioRender.com.

Inefficient transmission in ferrets

At present, it is unknown whether bovine H5N1 viruses transmit among mammals through respiratory droplets. To test this possibility, we carried out a respiratory droplet transmission experiment in ferrets as described previously17. Groups of ferrets were infected with 106 PFU of either Cow-H5N1 or Isumi-H1N1 (four ferrets per virus), which is known to transmit efficiently by means of respiratory droplets11. One day later, naive animals were housed in cages next to the infected animals (one contact ferret per infected donor), separated by about 5 cm to prevent transmission by direct contact. Nasal swab samples were collected from infected and exposed animals every other day starting on day 1 postinfection or postexposure, respectively, and virus titres were assessed. Ferrets infected with either Cow-H5N1 or Isumi-H1N1 showed clinical signs of disease (Extended Data Fig. 6) and high virus titres in nasal swabs collected over several days, with a delay in the peak virus titre of animals infected with Cow-H5N1 (Fig. 5a). By contrast, only the exposed animals in the Isumi-H1N1 group showed signs of clinical disease (Extended Data Fig. 6) and virus in the nasal swabs (Fig. 5b). These data indicate that the Isumi-H1N1 virus, but not the Cow-H5N1 virus, transmits efficiently through respiratory droplets in ferrets. A haemagglutination inhibition assay carried out with serum collected from all ferrets that survived until day 21 postinfection or postexposure revealed high neutralization titres for all infected and exposed animals in the Isumi-H1N1 group (Fig. 5c), consistent with their demonstrated infection. In addition, although no virus was detected in any of the animals exposed to the Cow-H5N1-infected ferrets (Fig. 5a), one of four exposed animals had a positive, albeit low, haemagglutination inhibition titre (Fig. 5c). No viral genomic sequences were detected in, and no virus was amplified from, any of the nasal swabs of the seroconverted ferret. Therefore, bovine H5N1 virus may transmit inefficiently by the respiratory droplet route in ferrets.

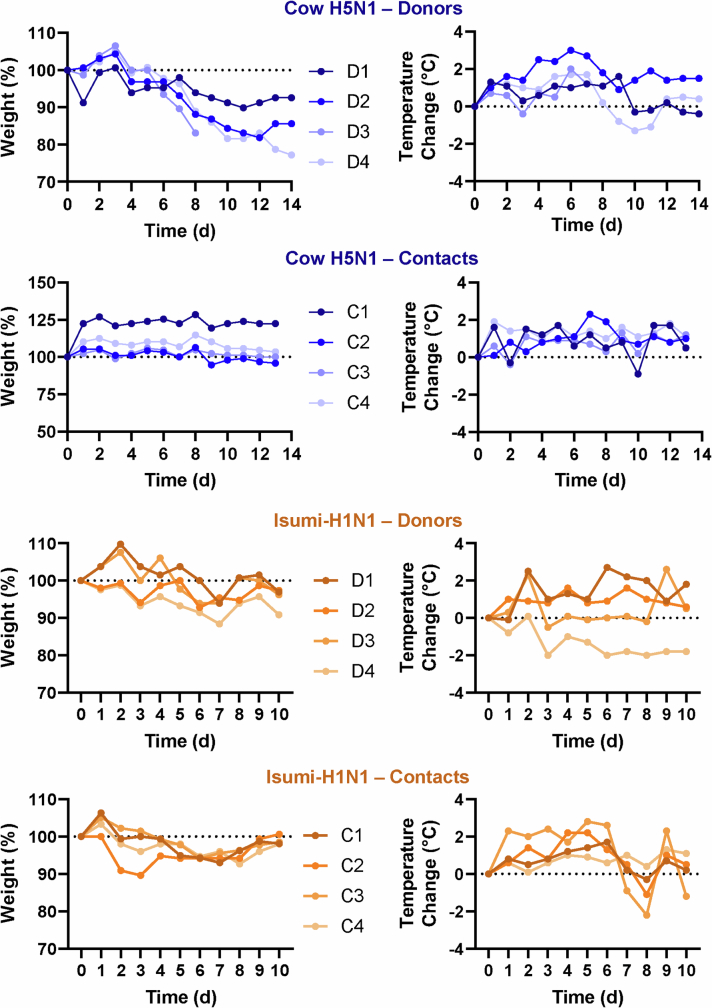

Extended Data Fig. 6. Clinical data associated with ferrets used to assess respiratory droplet transmission.

For the same ferrets shown in Fig. 5 (n = 4 biologically independent infected donor animals and n = 4 biologically independent aerosol contact animals), daily body weights and body temperatures are shown. The dotted lines indicate starting weights or body temperatures. D, donor (infected) ferret; C, contact ferret.

Fig. 5. Bovine H5N1 virus transmits inefficiently by respiratory droplets in ferrets.

a,b, Ferrets (4–6 months old, n = 4 biologically independent animals per virus) were deeply anaesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 106 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1; ‘Cow-H5N1’) (a) or A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018 (H1N1; ‘Isumi-H1N1’) (b) in 500 μl of PBS. One day later, naive ferrets (n = 1 biologically independent animal per infected animal) were placed in adjacent cages allowing for air flow but no direct contact with the infected animals. Nasal swab samples were collected at the indicated timepoints and tested by plaque assays in MDCK cells. In a and b, the dotted lines represent the limit of detection. c, Sera collected from recovered ferrets were subjected to haemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays with Cow-H5N1 or Isumi-H1N1, and HI titres are shown. The floating bars represent the mean HI titre for each group and error bars represent standard deviation. Ferrets showing no seroconversion were assigned arbitrary values below the limit of detection so they could be represented on the graph.

Receptor-binding preference

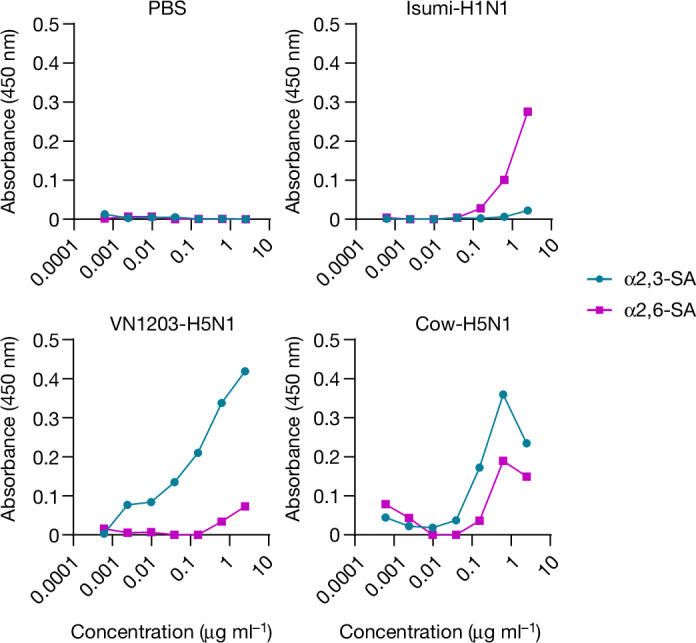

Influenza A virus binds to sialic acid receptors on the surface of susceptible cells to initiate infection. Human influenza A viruses preferentially bind to sialic acids linked to galactose by an α2,6-linkage, whereas avian influenza A viruses preferentially bind to α2,3-linked sialic acid. Because α2,6-linked sialic acids are abundantly distributed in the upper respiratory tract of humans, influenza A viruses that can bind to α2,6-linked sialic acids may have a greater capacity to transmit among humans. To test the receptor specificity of Cow-H5N1, we used an established assay using α2,3- or α2,6-linked sialylglycopolymers to measure virion binding to α2,3- or α2,6-linked sialic acid17,18. As expected, the human Isumi-H1N1 virus showed a clear preference for α2,6-linked sialic acids, whereas the avian VN1203-H5N1 virus showed a clear preference for α2,3-linked sialic acids (Fig. 6). By contrast, the Cow-H5N1 virus bound to both α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acids, indicating that the Cow-H5N1 virus may have the ability to bind to cells in the upper respiratory tract of humans. The dual receptor-binding specificity of Cow-H5N1 was confirmed by two independent replicate experiments (Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8). As dual receptor-binding specificity was not observed for the older, distantly related VN1203-H5N1 isolate (Fig. 6 and Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8), it may be a feature unique to the HPAI H5N1 virus that recently emerged in dairy cattle.

Fig. 6. Bovine H5N1 virus binds to both α2,3 and α2,6 sialic acid residues.

Fourfold serial dilutions of α2,3 and α2,6 sialylglycopolymers adhered to microtitre plates were incubated with 32 haemagglutination (HA) units of the indicated viruses or PBS (negative control). After washing, virus binding was detected by an anti-HA human monoclonal antibody (CR9114) and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The absorbance values for each condition with each virus or PBS are shown. Each dot represents a single biologically independent replicate value.

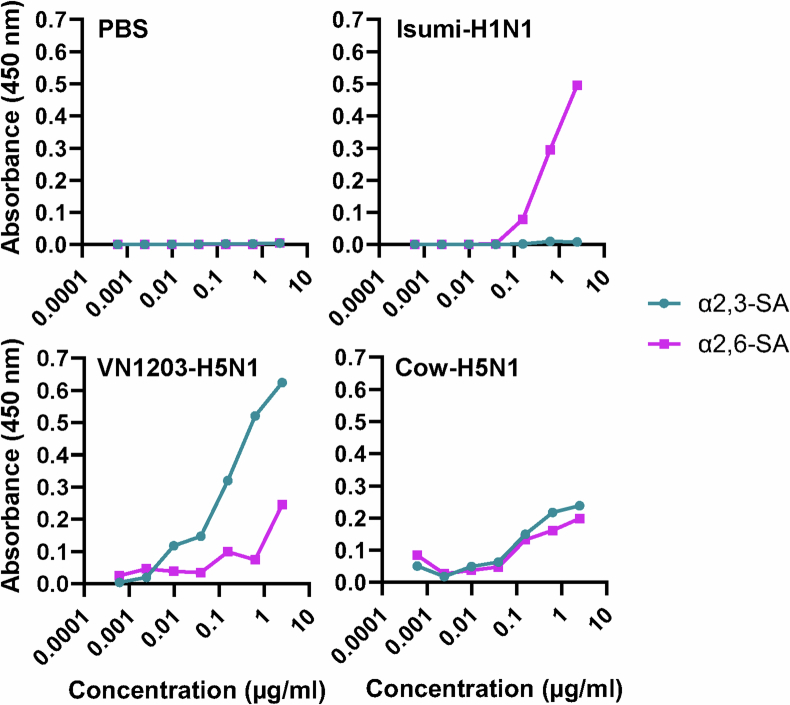

Extended Data Fig. 7. Bovine H5N1 virus binds to both α2,3 and α2,6 sialic acid residues, replicate experiment 2.

Four-fold serial dilutions of α2,3 and α2,6 sialylglycopolymers adhered to microtitre plates were incubated with 32 hemagglutination (HA) units of the indicated viruses or PBS (negative control). After washing, virus binding was detected by an anti-HA human monoclonal antibody (CR9114) and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The absorbance values for each condition with each virus or PBS are shown. Each dot represents the mean of two biologically independent replicate values.

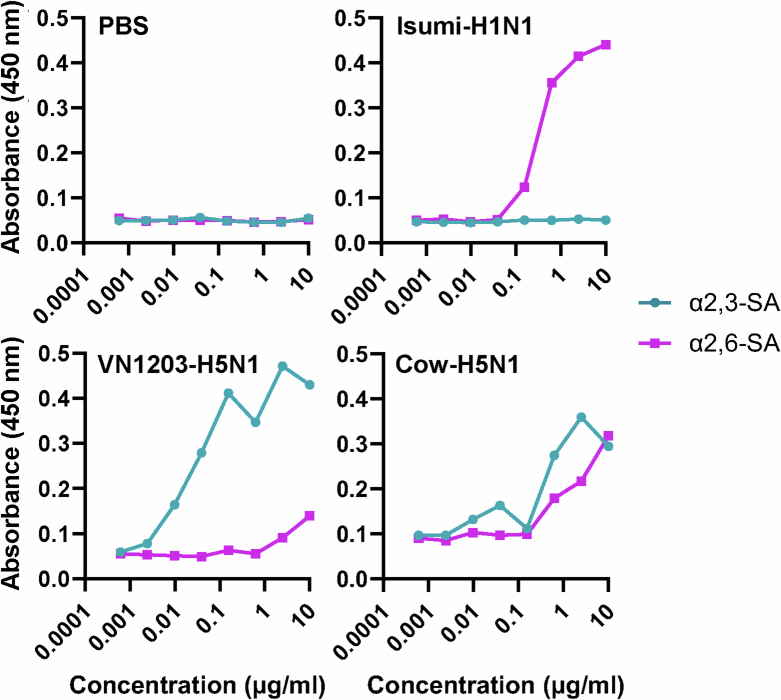

Extended Data Fig. 8. Bovine H5N1 virus binds to both α2,3 and α2,6 sialic acid residues, replicate experiment 3.

Four-fold serial dilutions of α2,3 and α2,6 sialylglycopolymers adhered to microtitre plates were incubated with 16 hemagglutination (HA) units of the indicated viruses or PBS (negative control). After washing, virus binding was detected by an anti-HA human monoclonal antibody (CR9114) and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The absorbance values for each condition with each virus or PBS are shown. Each dot represents a single biologically independent replicate value.

Discussion

HPAI H5N1 influenza viruses do not transmit efficiently among mammals. Moreover, influenza A viruses have rarely been detected in cattle. Thus, the current outbreak of HPAI H5N1 influenza viruses in dairy cows and the spillover into other mammalian species may have profound consequences for public health and the dairy industry.

Although more than 850 people and increasing numbers of mammals have been infected with HPAI H5N1 viruses, sustained transmission among mammals has not been reported, although we12 and others19,20 have suggested that it may be possible. Recently, mammal-to-mammal transmission may have occurred during outbreaks of HPAI H5N1 viruses in mink in Spain21 and sea mammals in South America10. Sutton and colleagues22 reported respiratory droplet transmission of mink HPAI H5N1 virus from experimentally infected to exposed ferrets, but we did not detect respiratory droplet transmission of mink HPAI H5N1 viruses in ferrets11; these differences may result from the different virus isolates used and/or differences in experimental settings. Here we found that a bovine HPAI H5N1 virus may have transmitted to exposed ferrets at low efficiency, resulting in seroconversion in the absence of detectable virus in nasal swabs. While this work was under review, the US CDC reported limited (33%) respiratory droplet transmission in ferrets of an HPAI H5N1 virus isolated from an infected farm worker in Texas (A/Texas/37/2024) during the current outbreak in dairy cattle23, which supports our findings. The discovery that HPAI H5N1 viruses may acquire the ability to transmit among mammals is a paradigm shift and increases the pandemic potential of these viruses. The isolate we tested does not encode PB2-E627K, an amino acid substitution that facilitates the efficient replication of avian influenza viruses in mammals24,25. However, this substitution was detected in the HPAI H5N1 virus isolated from the infected farm worker in Texas. Further studies with human HPAI H5N1 isolates are urgently needed to fully assess the risks they pose to the greater human population.

The host range of influenza viruses is determined, in part, by their receptor-binding specificity because avian influenza viruses prefer α2,3-linked sialic acids (expressed in the gastrointestinal tract of avian species), whereas human influenza viruses prefer α2,6-linked sialic acids (the predominant sialic acid species in the upper respiratory tract of humans). The 1957 and 1968 pandemic influenza viruses possess human-type receptor-binding specificity, even though their HAs originated from avian influenza viruses. The HPAI H5N1 viruses tested so far showed avian-type receptor-binding specificity (for example, refs. 26–29); however, here we detected human- and avian-type receptor-binding specific for a bovine HPAI H5N1 virus, consistent with the finding of both sialic acid species in udders of cattle30. At present, we do not know whether this dual receptor-binding specificity reflects adaptive changes in cattle or is also a trait of other North American HPAI H5N1 viruses. Collectively, our study demonstrates that bovine H5N1 viruses may differ from previously circulating HPAI H5N1 viruses by possessing dual human/avian-type receptor-binding specificity with limited respiratory droplet transmission in ferrets.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments and procedures were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committees of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine (protocol no. V006426-A04). The ambient conditions of the animal facilities were 25–28 °C and 35–45% humidity. Animals were acclimated to the facilities before the start of the experiments, maintained on a 12 h on and off light cycle, given access to food and water ad libitum, and provided with enrichment. Humane endpoint criteria for both ferrets and mice after infection comprised the following: greater than or equal to 35% body weight loss or inability to remain upright.

Biosafety

In the USA, HPAI viruses are ‘Select Agents’ as described in title 9, Code of Federal Regulations Parts 121 and 122. After the identification of HPAI H5 viruses, they were reported immediately to the Federal Select Agent Program. All experiments were carried out in Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) containment laboratories (ferret experiments were performed under BSL-3-Ag containment) at the Influenza Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which is approved by the Federal Select Agent Program for studies with these viruses. Funding for this study came in part from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Response (contract number 75N93021C00014). All experiments were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Biosafety Committee and all animal experiments were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Animal Care and Use Committee. The NIAID grant for the studies conducted was reviewed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Dual Use Research of Concern (DURC) Subcommittee in accordance with the US Government September 2014 DURC Policy and determined to not meet the criteria of DURC. The University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Contact for Dual Use Research reviewed this paper and confirmed that the studies described herein do not meet the criteria of DURC.

Cells and viruses

MDCK cells (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection; no authentication was performed) were grown in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 5% newborn calf serum and were routinely monitored for mycoplasma contamination. A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1) was isolated in MDCK cells from a milk sample provided by the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory5. The isolated virus was fully sequenced (GenBank accessions: PQ067970, PQ068570, PQ068393, PQ068523, PQ068538, PQ068546, PQ068554 and PQ068562), amplified in MDCK cells and sequenced again. No mutations emerged during passage in MDCK cells. This virus isolate does not encode the mammalian-adapting mutations PB2-E627K (refs. 24,31) or PB2-D701N (refs. 32,33), but possesses the PB2-M631L substitution, the effect of which is like that of the PB2-E627K substitution34,35. In addition, in our previous publication5, we showed that this virus isolate is part of the same clade as other publicly available cow-H5N1 virus sequences. The amplified virus stock was used for all studies described, except when otherwise stated. As indicated, control viruses included a HPAI H5N1 virus (A/Vietnam/1203/2004)25, which was originally isolated from a human; and a human H1N1 influenza virus (A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018)11. Oral inoculation of mice was conducted with milk from an HPAI H5N1 virus-infected cow. An HPAI H5N1 virus was isolated from this milk sample, which was designated A/dairy cattle/Kansas/SM-3/2024 (GenBank accessions: PQ075947, PQ075948, PQ075926, PQ075934, PQ075935, PQ075946, PQ075949 and PQ075950). The consensus sequences of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1) and A/dairy cattle/Kansas/SM-3/2024 differ by nine amino acids: PB2-E249G, PB1-P384S, PA-K497R, PA-K613E, HA-N319S, NA-N71S, NS1-R21Q, NS1-R77L and NS1-K229E.

Oral inoculation of mice

Eight-week-old female BALB/cJ mice (Jackson Laboratories) were lightly anaesthetized with isoflurane and inoculated with the milk sample containing A/dairy cattle/Kansas/SM-3/2024 (25, 10, 5 or 1 μl; 10 mice per inoculation volume) by applying the virus to the back of the throat with a micropipette. All mice swallowed the inoculum. Following inoculation, five animals per inoculation volume were monitored daily for signs of illness for 14 days; and the other five animals per inoculation volume were euthanized on day 6 postinoculation, at which time organs (nasal turbinate, lung and brain) were collected for virus titration. For all animals that survived beyond 14 days postinoculation, blood was collected as follows: mice were deeply anaesthetized with isoflurane, cardiac puncture was performed to collect blood, and then the mice were euthanized. Blood was immediately transferred to serum separator tubes, centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 min and the resultant serum was frozen at −80 °C.

MLD50 determination

To determine the MLD50, 7 week-old female BALB/cJ mice were anaesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine and dexmedetomidine (45–75 mg kg−1 ketamine + 0.25–1 mg kg−1 dexmedetomidine) and intranasally inoculated with 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105 or 106 PFU in 50 µl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1) (five mice per dosage). To reverse the effects of dexmedetomidine, mice were injected i.p. with atipamezole (0.1–1 mg kg−1). Body weight changes and survival were monitored daily for 15 days. Infected mice were euthanized if they lost more than 35% of their initial body weight. Lethal dose 50 values were calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench36.

Tissue tropism in mice

Seven- to ten-week-old female BALB/cJ mice were anaesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine and dexmedetomidine (45–75 mg kg−1 ketamine + 0.25–1 mg kg−1 dexmedetomidine) and intranasally inoculated with 103 PFU (in 50 μl of PBS) of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1), A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) or A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018 (H1N1). At days 3 and 6 postinfection, groups of five mice were euthanized and the following tissues were collected in the order listed and frozen at −80 °C: whole blood, eye, teat, mammary gland, brain, colon, liver, spleen, kidney, heart, nasal turbinate, trachea, lung, hamstring and latissimus dorsi. Instruments used for tissue dissection were disinfected after each tissue was collected to prevent cross-contamination of virus between organs. Whole blood was snap-frozen on dry ice immediately after collection in the absence of anticoagulant. Later, frozen tissue samples were thawed, mixed with 1 ml of MEM medium containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and homogenized by using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen) at 30 Hz oscillation frequency for 3 min. Homogenates were clarified by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 10 min) and used for plaque assays in MDCK cells. Whole blood was thawed and used directly for plaque assays.

Tissue tropism in ferrets

Four- to six-month-old female ferrets (Triple F Farms) (confirmed to be serologically negative to the following influenza viruses, A/Hong Kong/4/2022 (H3N2), A/Wisconsin/588/2019 (H1N1), B/Washington/02/2019 and A/Astrakhan/3212/2020 (H5N8)) were anaesthetized intramuscularly with ketamine and dexmedetomidine (4–5 mg kg−1 and 10–40 µg kg−1 of body weight, respectively) and infected intranasally with 106 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1), A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1), or A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018 (H1N1) in 500 µl of PBS as indicated in the text and figure legends. Body weights and body temperatures were monitored daily. At day 3 or 6 postinfection, groups of four ferrets were euthanized and the following tissues were collected and frozen at −80 °C: eye, teat, mammary gland, hamstring, latissimus dorsi, brain, whole blood (collected from the jugular vein), colon, liver, spleen, kidney, heart, nasal turbinate, trachea and lung. Tissues were collected in the order listed to prevent cross-contamination of virus from respiratory organs. As done for mice, whole blood was immediately snap-frozen on dry ice and stored without anticoagulant. Ferret tissues were prepared for plaque assays in MDCK cells as follows: organs were mixed with 1 ml of MEM medium containing 0.3% BSA, homogenized at 1,850 rpm for six cycles (ON: 6 s; OFF: 4 s) in a multi-bead homogenizer (Yasui Kikai Corporation), centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min and then used for plaque assays in MDCK cells.

Transmission in mice

Ten- to 12 week-old lactating female BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories or Taconic Biosciences) at 5–7 days postdelivery were intranasally inoculated with 100 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1) in 50 μl of PBS under isoflurane anaesthesia. Two hours after inoculation, the mice were returned to cages with their litters or cohoused with three adult BALB/cJ mice (8–12 weeks old). Cohoused adults were added to cages with infected, lactating females either 2 h (day 7 timepoint, lactating females no. 1–6) or 24 h (day 4, all lactating females; day 7, lactating females no. 7–9 and day 9, all lactating females) after infection. At days 4, 7 or 9 postinfection, lactating females, pups and contacts were euthanized and tissues were collected and frozen at −80 °C. From lactating females, mammary gland, brain, nasal turbinate and lung tissues were collected. From pups of lactating females, brain, lung and intestine tissues were collected. From adult contacts cohoused with lactating females, brain, nasal turbinate and lung tissues were collected. Tissues were prepared for plaque assays in MDCK cells as described for other mouse tissues above. At the day 9 timepoint, milk was collected from infected lactating females under isoflurane anaesthesia by squeezing the mammary gland after i.p. oxytocin injection (2 IU per mouse; Bimeda). For lactating females that succumbed before euthanasia, no oxytocin was given. A micropipette was used to collect the milk (up to 5 μl) directly from the teat, and milk was mixed with 100 μl of PBS before virus titration by plaque assay in MDCK cells.

Respiratory droplet transmissibility

Female ferrets were infected intranasally with 106 PFU of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1) or A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018 (H1N1) in 500 µl of PBS (four ferrets per virus). One day later, naive ferrets (aerosol contacts; one contact per infected animal) were placed in cages adjacent to infected ferrets in an isolator rack. The cages housing the infected or exposed ferrets were separated by about 5 cm. The transmission study was carried out under controlled conditions of 20–25 °C and relative humidity of 38.4 ± 8.8%. The air flow was from the front to the back of the isolator rack; thus, the air flow direction was perpendicular to the direction of virus transmission between the ferrets. Nasal swab samples were collected on day 1 after infection or exposure, respectively, and then every other day. The swabs were presoaked in PBS, inserted into the ferret’s nasal cavity and then placed in a tube containing 1.0 ml of MEM with 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 µg ml−1 streptomycin and vortexed for 1 min. The virus titre was determined by plaque assay in MDCK cells. At 21 days postinfection, blood was collected from the infected and contact ferrets in both groups, transferred to serum separator tubes, centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 min and the resultant serum was frozen at −80 °C.

Plaque assays

Plaque assays were performed by using standard methods. Briefly, confluent MDCK cells were washed with 1× MEM containing 0.3% BSA (MEM/BSA), followed by infection with serial dilutions of virus. Infected cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, washed with 1× PBS and then covered with 1× MEM/BSA plus 1% low melting point agarose in the presence of 0.6 µg ml−1 TPCK-treated trypsin. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2–3 days, and the monolayers were then fixed with 10% formalin. After removal of the agar overlay and air-drying, the virus plaques were counted under fluorescent light.

Haemagglutination inhibition assay

Ferret or mouse sera were treated with receptor destroying enzyme (Denka Seiken Co., Ltd) at 37 °C for 18–20 h, followed by heat inactivation at 56 °C for 50 min and then adsorbed with turkey red blood cells for 1 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. Then, twofold serial dilutions of treated sera were prepared in 96-well V-bottom plates and mixed with four haemagglutination units of A/dairy cattle/New Mexico/A240920343-93/2024 (H5N1) or A/Isumi/UT-KK001-01/2018 (H1N1). After 30 min at room temperature, 0.5% turkey red blood cells were added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The haemagglutination inhibition titre was read as the reciprocal of the last dilution of serum that completely prevented haemagglutination.

Virus growth in embryonated chicken eggs

Ten-day-old embryonated chicken eggs were inoculated with nasal swab samples as described37. Two days later, eggs were killed by incubation at 4 °C overnight. The next morning, allantoic fluids were collected and a small aliquot was assessed by use of the haemagglutination assay according to standard methods.

qPCR

RNA was extracted from ferret nasal swab samples or egg allantoic fluids by using the MagMAX-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) reactions were carried out with the TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix for qPCR (Applied Biosystems) and the following primers: H5-forward, 5′-TACCAGATACTGTCAATTTATTCAAC-3′; H5-reverse, 5′-GTAACGACCCATTGGAGCACATCC-3′; H5 FAM probe, 5′-56-FAM/CTGGCAATCATGATGGCTGGTCT/3BHQ_1-3′; M-forward, 5′-CTTCTAACCGAGGTCGAAACGTA-3′; M-reverse, 5′-GGTGACAGGATTGGTCTTGTCTTTA-3′ and M VIC probe, 5′-5HEX/TCGGGCCCCCTCAAAGCCGAG/3BHQ_1-3′. qPCR reactions were performed with the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) as follows: (1) 50 °C for 20 min, (2) 95 °C for 5 min and (3) 40 cycles of 95° for 15 s and 60 °C for 45 s; and then cycle threshold values were determined.

Solid-phase binding assay

Microtitre plates (Nunc) were incubated with fourfold serial dilutions (2.5, 0.625, 0.156, 0.039, 0.01, 0.002 and 0.001 μg ml−1) of the sodium salts of sialylglycopolymers (Yamasa Corporation Co. Ltd)—Neu5Acα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1-poly-Glu (α2,3SA) and Neu5Acα2,6Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1-poly-Glu (α2,6SA)—in PBS at 4 °C overnight. The next day, glycopolymer solutions were removed and non-specific binding was blocked by the addition of PBS containing 4% BSA at room temperature for 1 h. Plates were washed with cold PBS, and then solutions containing influenza viruses (16 haemagglutination units in PBS for the data shown in Extended Data Fig. 8 and 32 haemagglutination units in PBS for the data shown in Fig. 6 and Extended Data Fig. 7) were added and plates were incubated at 4 °C overnight. Plates were washed with cold PBS and then incubated with broadly reactive human monoclonal CR9114 antibody (HumImmu; 1:1,000 dilution, catalogue no. A90001) for 1 h at room temperature (for the data shown in Extended Data Fig. 8) or 1 h at 4 °C (for the data shown in Fig. 6 and Extended Data Fig. 7). The plates are washed again as before and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-human IgG (Abcam, catalogue no. ab6858) for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed, the plates were incubated with o-phenylenediamine (Sigma) in PBS containing 0.03% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an optical plate reader (BioTek). The data shown in Fig. 6 and Extended Data Fig. 8 represent a single technical replicate per condition, whereas the data shown in Extended Data Fig. 7 represent two technical replicates per condition.

Statistics and reproducibility

All animals were randomly allocated to experimental groups. No blinding was performed in any experiment. Sample sizes were based on our previous work. All graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism software, v.9.5.1. Basic summary statistics (that is, calculations of means, standard deviations, medians and data ranges) were calculated and plotted by using GraphPad Prism. Virus titres of nasal turbinate, lung and brain tissues from orally inoculated mice (25 and 10 μl groups) were log10-transformed and compared by using non-parametric, two-tailed Mann–Whitney tests in GraphPad Prism software and P values are reported in the Fig. 1c legend. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed. Except for experiments with lactating mice (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 5), all other figures represent data derived from a single experiment. Mouse experiments shown in Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2 are similar, except that the experiment shown in Fig. 2c included mice infected with Isumi-H1N1 and collection of muscle tissues and blood. Ferret experiments shown in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 4 are similar, except that the experiment shown in Extended Data Fig. 4 included ferrets infected with Isumi-H1N1, a single timepoint for tissue collection (day 6) and collection of muscle tissues and blood. For the data shown in Fig. 4, lactating females at each timepoint were infected on the same days (that is, day 4 animals were infected on the same day, day 7 animals were infected on the same day and day 9 animals were infected on the same day). For the data shown in Extended Data Fig. 5: the single lactating female on day 4 (Extended Data Fig. 5a) was infected on the same day as those from the same timepoint in Fig. 4a, one lactating female on day 7 (Extended Data Fig. 5b, top panel) was infected on the same day as those from the same timepoint in Fig. 4b and the other three were infected in another experiment and all four lactating females on day 9 (Extended Data Fig. 5c) were infected on the same day as those from the same timepoint in Fig. 4c). Three independent receptor-binding experiments were performed, and the data from all three are shown separately (Fig. 6 and Extended Data Figs. 7 and 8).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIAID Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Response (contract no. 75N93021C00014), non-sponsored discretionary funding and by grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant nos. JP24wm0125002, JP243fa627001 and JP24fk0108626 to Y.K.), the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) (grant no. 2023-37624-40714 to K.P.), Colorado State University (USDA NIFA: grant no. AP23VSD&B000C020 to K.P.), the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) (grant no. AP22VSSP0000C024 to K.P.), the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (grant no. WIAE 2307 to K.P.) and the APHIS National Animal Health Laboratory Network Enhancement Project (grant no. AP21VSD&B000C005 to K.M.D.). We extend our gratitude to J. A. Lucey (University of Wisconsin-Madison) for providing whole, unpasteurized milk from a healthy cow, which was used in the mouse oral inoculation experiment. We also thank H. D. Nguyen, R. Presler Jr., P. Jester and K. Loyva for technical assistance, and S. Watson for editing the paper. Mouse illustrations used in Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 5 were created with Biorender (https://BioRender.com).

Extended data figures and tables

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.J.E., P.J.H., G.N. and Y.K. Data curation: A.J.E., A.B., L.G., C.G., T.M., S.T., L.B., R.D. and G.N. Formal analysis: A.J.E., S.T. and L.B. Funding acquisition: Y.K. and K.P. Investigation: A.J.E., A.B., L.G., C.G., T.M., T.W., L.B., R.D. and G.N. Methodology: A.J.E., A.B., L.G., C.G., T.M., L.B., R.D., P.J.H., G.N. and Y.K. Project administration: A.J.E., P.J.H., S.T. and G.N. Resources: A.T., A.K.S., K.M.D., K.P., Y.S. and Y.K. Software: L.B. Supervision: Y.K. Validation: A.J.E., A.B., L.G., C.G., T.M., T.W., L.B. and R.D. Visualization: A.J.E. and S.T. Writing—original draft: A.J.E., G.N. and Y.K. Writing—review and editing: A.J.E., A.B., L.G., C.G., T.M., S.T., T.W., L.B., R.D., P.J.H., T.B., G.N., Y.S., A.T., A.K.S., K.M.D., K.P. and Y.K. Author contributions to specific experiments: the mouse oral inoculation experiment was performed by A.B., A.J.E., L.G. and C.G. Mouse intranasal inoculation experiments were performed by A.B., A.J.E., L.G., C.G. and T.M. Ferret experiments were performed by A.B., L.G., C.G., T.M. and T.W. Receptor-binding experiments were performed by T.M. Sequence analysis was performed by L.B., R.D. and G.N.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Massimo Palmarini and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Amie J. Eisfeld, Asim Biswas, Lizheng Guan, Chunyang Gu, Tadashi Maemura

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6.

References

- 1.USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Detections in Livestock. USDAwww.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/livestock (2024).

- 2.Caserta, L. C. et al. Spillover of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus to dairy cattle. Nature10.1038/s41586-024-07849-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.CDC Confirms Second Human H5 Bird Flu Case in Michigan; Third Case Tied to Dairy Outbreak. CDCwww.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p0530-h5-human-case-michigan.html (2024).

- 4.Uyeki, T. M. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in a dairy farm worker. N. Engl. J. Med.10.1056/NEJMc2405371 (2024). 10.1056/NEJMc2405371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan, L. et al. Cow’s milk containing avian influenza A(H5N1) Virus - heat inactivation and infectivity in mice. N. Engl. J. Med.10.1056/NEJMc2405495 (2024). 10.1056/NEJMc2405495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worobey, M. et al. Preliminary report on genomic epidemiology of the 2024 H5N1 influenza A virus outbreak in U.S. cattle (Part 1 of 2) (virological.org, 2024); https://virological.org/t/preliminary-report-on-genomic-epidemiology-of-the-2024-h5n1-influenza-a-virus-outbreak-in-u-s-cattle-part-1-of-2/970.

- 7.Worobey, M. et al. Preliminary report on genomic epidemiology of the 2024 H5N1 influenza A virus outbreak in U.S. cattle (Part 2 of 2) (virological.org, 2024); https://virological.org/t/preliminary-report-on-genomic-epidemiology-of-the-2024-h5n1-influenza-a-virus-outbreak-in-u-s-cattle-part-2-of-2/971.

- 8.Meade, P. S. et al. Detection of clade 2.3.4.4b highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus in New York City. J. Virol.10.1128/jvi.00626-24 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Puryear, W. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus outbreak in New England Seals, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis.29, 786–791 (2023). 10.3201/eid2904.221538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomas, G. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infections in pinnipeds and seabirds in Uruguay: Implications for bird-mammal transmission in South America. Virus Evol.10, veae031 (2024). 10.1093/ve/veae031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maemura, T. et al. Characterization of highly pathogenic clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 mink influenza viruses. eBioMedicine97, 104827 (2023). 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai, M. et al. Influenza A variants with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir isolated from Japanese patients are fit and transmit through respiratory droplets. Nat. Microbiol.5, 27–33 (2020). 10.1038/s41564-019-0609-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burrough, E. R. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b virus infection in domestic dairy cattle and cats, United States, 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis.30, 1335–1343 (2024). 10.3201/eid3007.240508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Updates on H5N1 Beef Safety Studies. USDAwww.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/livestock/h5n1-beef-safety-studies (2024).

- 15.Belser, J. A., Sun, X., Pulit-Penaloza, J. A. & Maines, T. R. Fatal infection in ferrets after ocular inoculation with highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis.30, 1484–1487 (2024). 10.3201/eid3007.240520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pulit-Penaloza, J. A. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus of clade 2.3.4.4b isolated from a human case in Chile causes fatal disease and transmits between co-housed ferrets. Emerg. Microbes Infect.13, 2332667 (2024). 10.1080/22221751.2024.2332667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imai, M. et al. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature486, 420–428 (2012). 10.1038/nature10831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambaryan, A. S. & Matrosovich, M. N. A solid-phase enzyme-linked assay for influenza virus receptor-binding activity. J. Virol. Methods39, 111–123 (1992). 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90130-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herfst, S. et al. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science336, 1534–1541 (2012). 10.1126/science.1213362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, L. M. et al. In vitro evolution of H5N1 avian influenza virus toward human-type receptor specificity. Virology422, 105–113 (2012). 10.1016/j.virol.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguero, M. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in farmed minks, Spain, October 2022. Euro. Surveill.28, 2300001 (2023). 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.3.2300001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Restori, K. H. et al. Risk assessment of a highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus from mink. Nat. Commun.15, 4112 (2024). 10.1038/s41467-024-48475-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CDC Avian Influenza (Bird Flu). CDC Reports A(H5N1) Ferret Study Results (CDC, 2024); www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/ferret-study-results.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/spotlights/2023-2024/ferret-study-results.htm.

- 24.Hatta, M., Gao, P., Halfmann, P. & Kawaoka, Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science293, 1840–1842 (2001). 10.1126/science.1062882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatta, M. et al. Growth of H5N1 influenza A viruses in the upper respiratory tracts of mice. PLoS Pathog.3, 1374–1379 (2007). 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang, P. et al. Characterization of the haemagglutinin properties of the H5N1 avian influenza virus that caused human infections in Cambodia. Emerg. Microbes Infect.12, 2244091 (2023). 10.1080/22221751.2023.2244091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xing, X. et al. Evolution and biological characterization of H5N1 influenza viruses bearing the clade 2.3.2.1 hemagglutinin gene. Emerg. Microbes Infect.13, 2284294 (2024). 10.1080/22221751.2023.2284294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bi, Y. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus struck migratory birds in China in 2015. Sci. Rep.5, 12986 (2015). 10.1038/srep12986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui, K. P. et al. Tropism and innate host responses of influenza A/H5N6 virus: an analysis of ex vivo and in vitro cultures of the human respiratory tract. Eur. Respir. J.49, 1601710 (2017). 10.1183/13993003.01710-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kristensen, C., Jensen, H. E., Trebbien, R., Webby, R. J. & Larsen, L. E. The avian and human influenza A virus receptors sialic acid (SA)-α2,3 and SA-α2,6 are widely expressed in the bovine mammary gland. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/2024.05.03.592326v1 (2024).

- 31.Subbarao, E. K., London, W. & Murphy, B. R. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol.67, 1761–1764 (1993). 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1761-1764.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabriel, G. et al. The viral polymerase mediates adaptation of an avian influenza virus to a mammalian host. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA102, 18590–18595 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0507415102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan, S. et al. Novel residues in avian influenza virus PB2 protein affect virulence in mammalian hosts. Nat. Commun.5, 5021 (2014). 10.1038/ncomms6021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Idoko-Akoh, A. et al. Creating resistance to avian influenza infection through genome editing of the ANP32 gene family. Nat. Commun.14, 6136 (2023). 10.1038/s41467-023-41476-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staller, E. et al. Structures of H5N1 influenza polymerase with ANP32B reveal mechanisms of genome replication and host adaptation. Nat. Commun.15, 4123 (2024). 10.1038/s41467-024-48470-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reed, L. J. & Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hygiene27, 493–497 (1938). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisfeld, A. J., Neumann, G. & Kawaoka, Y. Influenza A virus isolation, culture and identification. Nat. Protoc.9, 2663–2681 (2014). 10.1038/nprot.2014.180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data are provided with this paper.