Abstract

Pulmonary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas (HGNECs) have poor prognoses and require multimodal treatment, and interstitial lung disease (ILD) restricts sufficient treatment of patients with lung cancer. We aimed to clarify ILD’s prognostic impact on pulmonary HGNEC, which has previously gone unreported. We retrospectively analyzed 53 patients with HGNEC who underwent resections at our department between 2006 and 2021 and evaluated the clinicopathological prognostic features, including ILD. The patients’ mean age was 70 years; 46 (87%) were male, and all were smokers. Large-cell neuroendocrine and small-cell lung carcinomas were diagnosed in 36 (68%) and 17 (32%) patients, respectively. The pathological stages were stage I, II, and III in 31 (58%), 11 (21%), and 11 (21%) patients, respectively. Nine patients (17%) had ILD, which was a significant overall survival prognostic factor in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (p = 0.048), along with lymph node metastasis (p = 0.004) and non-administration of platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy (p = 0.003). The 5 year survival rate of the ILD patients was 0%, significantly worse than that of patients without ILD (58.7%; p = 0.003). Patients with HGNEC and ILD had a poor prognosis owing to adjuvant therapy’s limited availability for recurrence and the development of acute exacerbations associated with ILD.

Subject terms: Lung cancer, Respiratory tract diseases

Introduction

Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC), and carcinoids are all classified as neuroendocrine tumors of the lung in the 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors1. Among them, SCLC and LCNEC are categorized as high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (HGNEC) as these tumors exhibit malignant behavior, and their prognosis is worse than that of carcinoids1,2. HGNEC has a worse prognosis than other histopathological types, such as adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, even in the early stages1,3. Furthermore, the recurrence rate after complete resection is high, and most cases are distant metastatic recurrences4,5. Thus, HGNEC requires multimodal treatment with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, even in early-stage patients6,7. Adjuvant chemotherapy improves the prognosis of SCLC, and some prospective studies have concluded that treatment with cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy can achieve better outcomes7,8. The effectiveness of platinum-based adjuvant therapy is similar for both SCLC and LCNEC9,10. A recent randomized study of irinotecan plus cisplatin and etoposide plus cisplatin therapy for patients with HGNEC revealed the non-superiority of irinotecan plus cisplatin11. Based on this evidence, adjuvant therapy using etoposide and cisplatin is considered the standard therapy for completely resected HGNEC.

Patients with HGNEC often have comorbidities, and this condition is common in heavy smokers1,12. Smoking is linked to various organ disorders, including cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, lung diseases, and other cancers, and the development of these disorders prevents the use of adjuvant therapy. For example, cisplatin cannot be used owing to the risk of heart failure, and the full dose of anti-cancer agents often cannot be applied owing to the risk of kidney dysfunction. In addition, interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a relatively rare pulmonary disease closely related to smoking that is a significant prognostic factor for lung cancer13. Many anti-cancer agents must be avoided in ILD patients owing to the increased incidence of acute exacerbation (AE)14,15. The prognosis of HGNEC may be influenced by such comorbidities owing to the lack of adequate multidisciplinary treatment. Therefore, the prognosis of HGNEC may be influenced by malignancy and progression, as well as by the presence of comorbidities.

Currently, there are no reports on the impact of comorbidities such as ILD on HGNEC. Detailed analysis of prognostic factors other than cancer-related factors and identification of populations with poor prognoses in HGNEC may help to determine improved treatment strategies.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics and histopathological variables are shown in Table 1. Fifty-three patients underwent complete resections for HGNEC of the lung at our hospital between January 2006 and March 2021. The average age was 70 years (range: 51–88 years), and 46 patients (87%) were male. All patients had a smoking history, 9 (17%) were diagnosed with ILD, 8 were diagnosed with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and one was diagnosed with collagen vascular disease interstitial pneumonia. LCNEC and SCLC were diagnosed in 36 (68%) and 17 (32%) patients, respectively. The mean tumor size was 3.2 cm (range: 0.5–12.0 cm), and lymph node metastasis was histopathologically identified in 16 patients (10 [29%] N1 and 6 [11%] N2). According to the TNM classification 8th edition, the number of stage IA, IB, IIB, IIIA, and IIIB classifications was 17 (32%), 14 (26%), 11 (21%), 10 (19%), and 1 (2%), respectively.

Table 1.

Patients’ clinicopathological characteristics (n = 53).

| N or mean | % or range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 70 | 51–88 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 46 | 87 |

| Female | 7 | 13 |

| Smoking history | ||

| Smoker | 53 | 100 |

| Pack-year | 55 | 10–150 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 32 | 60 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 9 | 17 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 13 | 25 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 | 6 |

| Histopathology | ||

| Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 36 | 68 |

| Combined large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 12 | 23 |

| Small cell lung carcinoma | 17 | 32 |

| Combined small cell lung carcinoma | 6 | 11 |

| Tumor size, centimeter | 3.2 | 0.5–12.0 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||

| N0 | 37 | 70 |

| N1 | 10 | 19 |

| N2 | 6 | 11 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 51 | 96 |

| Pathological stage (TNM classification 8th edition) | ||

| IA | 17 | 32 |

| IB | 14 | 26 |

| IIB | 11 | 21 |

| IIIA | 10 | 19 |

| IIIB | 1 | 2 |

Management of HGNEC

Table 2 shows a breakdown of the surgical procedures, adjuvant therapies, and management of recurrence. Lobectomy or bi-lobectomy, pneumonectomy, and limited resection were performed in 39 (74%), 6 (11%), and 8 (15%) patients, respectively. Adjuvant therapy using platinum agents and etoposide was administered to 22 (42%) patients. The 31 (58%) patients who did not receive the platinum-based adjuvant therapy were due to advanced age (eight patients), poor general condition (eight patients), patient preference (eight patients), ILD (six patients), and treatment for other advanced cancers (one patient). Recurrence occurred in 26 (49%) patients during the observational period. Carboplatin and etoposide were administered in 10 (38%) patients to treat recurrence. Palliative care was offered to 11 (42%) patients owing to their general condition or comorbidities.

Table 2.

Surgical procedure and treatment in patients with high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma.

| N or mean | % or range | |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical procedure (n = 53) | ||

| Lobectomy and bi-lobectomy | 39 | 74 |

| Pneumonectomy | 6 | 11 |

| Segmentectomy | 1 | 2 |

| Wedge resection | 7 | 13 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| Platinum + etoposide | 22 | 42 |

| Carboplatin + etoposide | 20 | 38 |

| Cisplatin + etoposide | 2 | 4 |

| Oral agent (UFT or TS-1) | 4 | 7 |

| None | 27 | 51 |

| Treatment for recurrence (n = 26) | ||

| Initial chemotherapy for recurrence | ||

| Carboplatin + etoposide | 10 | 38 |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel (+atezolizumab/bevacizumab) | 3 | 12 |

| Cisplatin + irinotecan | 1 | 4 |

| Docetaxel | 1 | 4 |

| Palliative therapy or best supportive care | 11 | 42 |

Analyses of prognostic factors in HGNEC

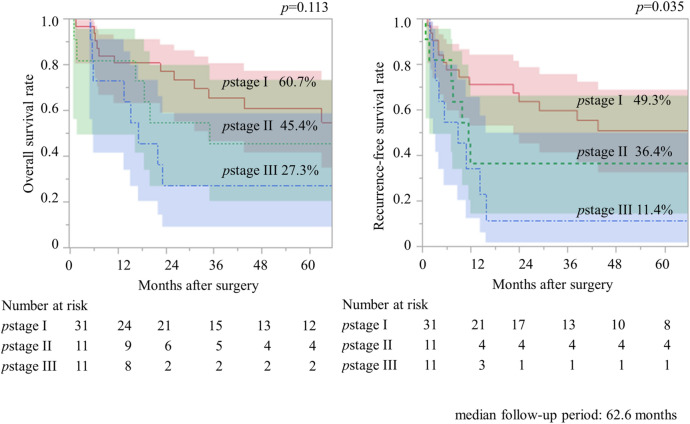

Figure 1 shows the association between pathological stage, OS, and RFS in patients with HGNEC. The median follow-up time was 62.6 months, and the 5 year OS rates of the patients with pathological stages I, II, and III were 60.7%, 45.4%, and 27.3%, respectively (p = 0.113). The 5-year RFS rates of patients with pathological stages I, II, and III were 49.3%, 36.4%, and 11.4%, respectively (p = 0.035).

Fig. 1.

Association between pathological stage, overall survival, and recurrence-free survival in patients with pulmonary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas (n = 53).

Table 3 shows the clinicopathological factors of the prognosticators of OS. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis identified the presence of ILD (p = 0.005), tumor size (p = 0.020), lymph node metastases (p = 0.019), and non-administration of adjuvant chemotherapy using a platinum-based agent (p = 0.008) as significant prognostic factors. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis using the significantly different variables detected by univariate analysis showed that the presence of ILD (p = 0.048), lymph node metastasis (p = 0.004), and non-administration of adjuvant chemotherapy using a platinum-based agent (p = 0.003) were significant prognostic factors.

Table 3.

Predictors of overall survival in patients with high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Reference | HR | 95%CI | p value | HR | 95%CI | p value |

| Age > 75 years | ≤ 75 years | 1.46 | 0.67–3.17 | 0.342 | |||

| Male | Female | 3.17 | 0.74–13.60 | 0.120 | |||

| PYS > 30 | ≤ 30 | 1.10 | 0.52–2.32 | 0.809 | |||

| Interstitial lung disease | None | 3.51 | 1.47–8.41 | 0.005* | 2.48 | 1.01–6.10 | 0.048* |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | None | 0.66 | 0.32–1.38 | 0.276 | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | None | 0.95 | 0.40–2.24 | 0.911 | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | None | 0.66 | 0.09–4.94 | 0.692 | |||

| SCLC | LCNEC | 0.90 | 0.40–2.05 | 0.804 | |||

| Combined | Pure | 1.36 | 0.65–2.87 | 0.408 | |||

| Tumor size | 1 cm up | 1.19 | 1.01–1.36 | 0.020* | 1.12 | 0.90–1.34 | 0.243 |

| Lymph node metastasis | None | 2.43 | 1.16–5.09 | 0.019* | 3.24 | 1.45–7.25 | 0.004* |

| Surgical procedure | 0.152 | ||||||

| Pneumonectomy | Sublobar | 1.45 | 0.39–5.30 | 0.579 | |||

| Lobectomy and bi-lobectomy | Sublobar | 0.57 | 0.21–1.54 | 0.268 | |||

| Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy | Others | 0.29 | 0.11–0.72 | 0.008* | 0.23 | 0.09–0.60 | 0.003* |

Sublobar limited resection including segmentectomy and wedge resection.

SCLC small cell lung carcinoma, LCNEC large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

*Statistical significant factor (p < 0.05).

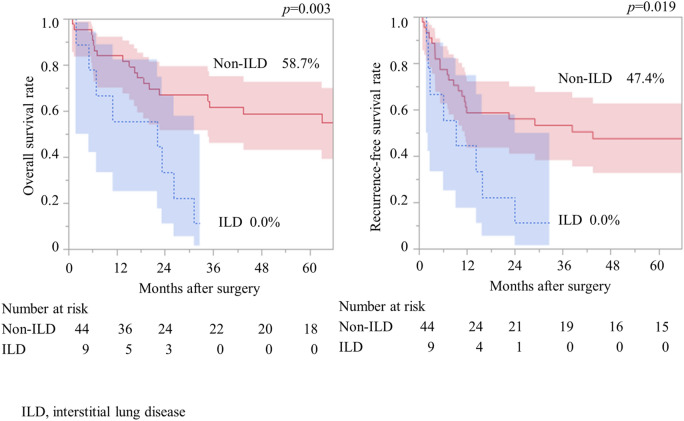

Analyses of the correlation between ILD and HGNEC

Clinical and pathological factors did not differ significantly between patients with and without ILD, except for pack-year smoking (Table 4). Although there was no significant difference, pneumonectomy was not performed in patients with ILD. The 5 year OS rate in patients with ILD was significantly worse than that in patients without ILD (0% vs. 58.7%, p = 0.003) (Fig. 2). The 5 year RFS rate was significantly worse than that in patients without ILD (0% vs. 47.4%, p = 0.019).

Table 4.

Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics and treatment between patients with and without interstitial lung disease.

| Variables | ILD (n = 9) | Non-ILD (n = 44) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or average | % or range | N or average | % or range | ||

| Age > 75 years | 3 | 33 | 14 | 32 | 0.930 |

| Male | 9 | 100 | 37 | 84 | 0.093 |

| PYS > 30 | 1 | 11 | 24 | 55 | 0.017* |

| Small cell lung carcinoma | 4 | 44 | 13 | 30 | 0.393 |

| Combined | 5 | 56 | 13 | 30 | 0.143 |

| Tumor size | 3.4 | 1.3–5.5 | 3.2 | 0.5–12.0 | 0.796 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 4 | 44 | 12 | 27 | 0.307 |

| Pathological stage | |||||

| I | 5 | 56 | 26 | 59 | 0.515 |

| II | 1 | 11 | 10 | 23 | |

| III | 3 | 33 | 8 | 18 | |

| Surgical procedure | |||||

| Pneumonectomy | 0 | 0 | 6 | 14 | 0.261 |

| Lobectomy and bi-lobectomy | 8 | 89 | 31 | 70 | |

| Segmentectomy and wedge resection | 1 | 11 | 7 | 16 | |

| Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy | 2 | 22 | 18 | 41 | 0.277 |

ILD interstitial lung disease.

*Statistically significant factor (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Association between idiopathic lung disease, overall survival, and recurrence-free survival in patients with pulmonary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas.

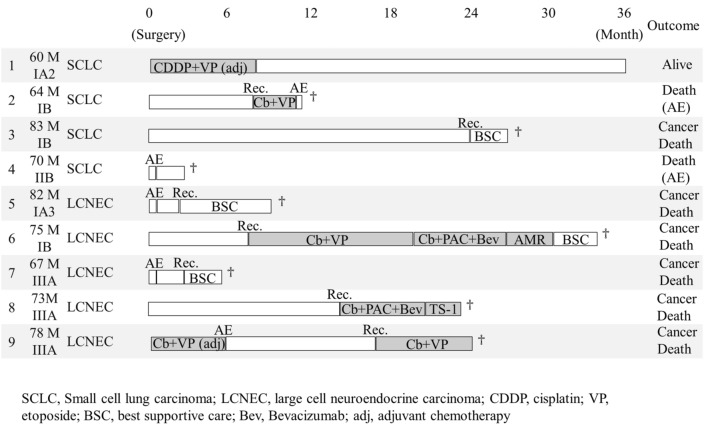

The data of outcomes comparing patients with and without ILD are shown in Table 5. The detailed progress and courses in nine patients with ILD showed that AEs occurred in five patients after surgery or during chemotherapy, and two patients died owing to AEs (Fig. 3). Recurrence was observed in seven patients, and six patients died of lung cancer. Three patients could not receive chemotherapy owing to their general condition such as postoperative AE.

Table 5.

Comparison of outcomes between patients with and without interstitial lung disease.

| Variables | ILD (n = 9) | Non-ILD (n = 44) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or average | % or range | N or average | % or range | |

| Postoperative complications (CTCAE grade ≥ 3) | 3 | 33 | 4 | 9 |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Acute exacerbation of ILD | 3 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 30-day mortality | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Recurrence | 7 | 78 | 19 | 43 |

| Death | 8 | 89 | 22 | 50 |

| Cancer death | 6 | 67 | 11 | 25 |

| Pneumonia/Respiratory failure | 0 | 0 | 5 | 11 |

| Acute exacerbation of ILD | 2 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Other cancer | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 |

ILD interstitial lung disease, CTCAE the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

Fig. 3.

Detailed courses of patients with pulmonary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas and idiopathic lung disease (n = 9).

Discussion

In our study, HGNEC with ILD was associated with a high rate of cancer death, and patients could not undergo adequate chemotherapy, including adjuvant therapy and treatment for their recurrence, owing to the risk of AE of ILD. In addition, AE development was common, which obviously affected their prognosis. The presence of comorbidities such as ILD that make multidisciplinary treatment difficult may have a significant impact on the prognosis of HGNEC.

Although classified as HGNECs, SCLC and LCNEC have different treatment strategies. For SCLC, the surgical indication is restricted to limited-disease-SCLC cases, and adjuvant chemotherapy using platinum-based medicine is effective at improving prognosis7,8. Chemoradiation therapy is the mainstay of treatment for SCLC with lymph node metastasis and extensive SCLC. Meanwhile, surgery is the mainstay of treatment for LCNEC, even in the advanced stages, and subsequent adjuvant therapy is desirable10,16,17. Therefore, multidisciplinary treatment, including chemotherapy, is indispensable for HGNEC treatment, and the prognosis for patients who do not or cannot receive chemotherapy is poor6.

Concomitant ILD is a significant limiting factor for chemotherapy; however, the safety and efficacy of chemotherapy for patients with lung cancer patients and ILD remain unclarified. Many anti-cancer drugs increase the risk of drug-induced cytotoxic lung disease, and chemotherapy carries the risk of AEs for patients with ILD18. For instance, some of the main anti-cancer agents for HGNEC reportedly induce cytotoxic ILD or are linked to the exacerbation of existing ILDs at a high rate; thus, patients with ILD could not be treated with these agents. Other anti-cancer agents may cause drug-induced ILD; thus, many clinical trials of chemotherapy for lung cancer excluded patients with ILD, meaning that the prognostic effect of chemotherapy for patients with ILD remains unclear. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors have greatly improved the prognosis of lung cancer in recent years. However, these treatments are also associated with drug-induced cytotoxic lung disease and pneumonitis, which raises concerns regarding their usage. The benefit of chemotherapy in SCLC patients with ILD is considerably high compared with NSCLC, even when the risk of AE is taken into account, as SCLC has a poor prognosis and a high response rate to anti-cancer agents19. In a previous study, Minegishi et al.20 prospectively analyzed the safety and efficacy of chemotherapy for patients with SCLC and ILD, whereas studies of chemotherapy for patients with lung cancer and ILD are limited to retrospective analyses of a small number of cases. These studies revealed that chemotherapy using a platinum agent and etoposide might help to improve prognosis, although the incidence of AE is approximately 2–16%, and the prognosis is relatively poor compared to that in cases without ILD20–22. Meanwhile, there have been no reports on the safety of chemotherapy for LCNEC with ILD, even though the prognosis is as poor as that for SCLC. Moreover, adjuvant therapy is not usually administered for lung cancer patients with ILD, even for HGNEC, when balancing the risk of developing an AE and the effect of preventing recurrence.

Conversely, patients with ILD comprise a diverse population in terms of classification and severity. The rate of cytotoxic ILD depends on the severity of respiration function and the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern on the CT scan. Among the classifications of ILD, idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) are important risk factors for cytotoxic lung disease and the occurrence of AE18,23,24. Furthermore, the occurrence of AE depends on the UIP pattern and preoperative respiration function in surgical treatment25,26. Recently, our institution reported that an accurate diagnosis of IIPs according to CT findings and histological patterns is important to ensure appropriate treatment is administered to patients with lung cancer who present with clinical ILD27. The accurate diagnosis of ILD (including histopathological examination) will enable multidisciplinary treatment and may contribute to improving the prognosis of HGNEC. Furthermore, attention to and appropriate treatment of the AE of ILD in the perioperative period is necessary to improve prognosis28. Postoperative AE occurs in 9.3% of patients and has a mortality rate of 43.9%29. Even if the patient can be saved, persistent respiratory impairment and general deterioration make administering chemotherapy difficult. In a previous study, we proposed a diagnosis and treatment strategy for postoperative AE and reported the importance of rapid and accurate diagnosis and treatment of AE30. We believe that adequate and rapid treatment for AE is also necessary to improve the prognosis of patients with HGNEC and ILD. Therefore, multidisciplinary treatment, including surgery and chemotherapy, should be performed for patients with HGNEC with no comorbidities that would interfere with chemotherapy. Meanwhile, other treatment options should be investigated for patients who cannot receive the standard treatment owing to their general condition or comorbidities, such as those with ILD, which we identified as a prognostic factor in this study, and research to increase treatment options should be promoted.

Limitations

The present study was a retrospective and single-center analysis, and both ILD and HGNEC are relatively rare; as such, the number of patients was small, and there were biases related to treatment. Moreover, this study spanned a long period during which changes in practices and thresholds to refer patients to surgery may have evolved. Therefore, multicenter studies with large sample sizes are required to construct a more definitive strategy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with HGNEC and ILD who underwent surgery had a poorer prognosis than those without ILD. This poor prognosis was linked to the development of AEs, which limited multimodal treatment, including adjuvant therapy and chemotherapy, for recurrence. Prognosis may be improved by proper diagnosis and management of ILD, as well as the development of therapy for patients with HGNEC who cannot receive the standard multidisciplinary treatment.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the database and clinical records of patients who underwent surgery at the Division of Chest Surgery, Department of Surgery, Toho University Omori Medical Center, Tokyo, Japan, between January 2006 and March 2021. We selected patients who underwent complete resections for HGNEC of the lung. Patients with incomplete resection, as well as those with insufficient clinicopathological data, were excluded. All included patients provided informed consent for data analyses through an opt-out feature on the university website. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Toho University (Approval number: A21093_A21039_A19039_27128_25095_25047). Study performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Treatment strategy and patient follow-up

Almost all patients underwent lobectomy and lymph node dissection; however, some underwent further limited surgeries, including wedge resection or segmentectomy, owing to bilateral lesions, impaired general conditions, and comorbidities such as chronic renal and heart failure. In SCLC, clinically limited-disease cases are included, for instance, stage I to III LCNEC patients were performed surgery. Preoperative chemotherapy was not performed in the study participants. After surgery, four courses of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy were provided every 3 weeks within 1–2 months. Cisplatin and etoposide were generally selected as adjuvant therapy; however, other agents, such as carboplatin, were selected instead in some patients aged over 75 years or those with comorbidities. Some patients chose oral agents, and some were unable to undergo additional chemotherapy owing to their general conditions and comorbidities. The dose of platinum agents was reduced by 80% or discontinued if the side effects were severe. After surgery and adjuvant therapy, the patients were followed up with chest radiography and blood tests (including tumor markers) every 3 months. Chest computed tomography and contrast-enhanced head magnetic resonance imaging were performed yearly for at least 5 years. Treatment for recurrence was administered if it was identified at follow-up or by the appearance of symptoms. Palliative therapy was administered if the patient could not tolerate chemotherapy. ILD was diagnosed preoperatively through a comprehensive evaluation of patient data, including physical examination, blood tests, walk tests, and CT scans and multidisciplinary discussions among respiratory physicians and thoracic surgeons specializing in this disease. To further validate these findings, all surgical specimens underwent pathological review. The cancer treatment of patients with ILD was also selected by the conference of multiple surgeons and pulmonologists. We perform limited resection for patients with ILD with comorbidities, poor performance status, and low pulmonary function as mentioned above, however, this strategy is the same as for patients without ILD.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of overall and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the chi-squared (χ2) or Fisher’s exact tests. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. JMP® version 15.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was applied for all statistical analyses.

Author contributions

T.S., Y.A., M.K., Sh.K., Sa.K., and A.I. have been involved in the conception and design of the study. T.S. wrote the manuscript. T.S., Y.A., M.K., Sa.K., and A.I collected data. T.S. performed statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding 23K15568 from The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI, and 22-15 from Toho University School of Medicine Project Research Grant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Toho University (approval number: A21093_A21039_A19039_27128_25095_25047).

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Travis, W. D. et al. The 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors: Impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J. Thorac. Oncol.10, 1243–1260 (2015). 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asamura, H. et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the lung: A prognostic spectrum. J. Clin. Oncol.24, 70–76 (2006). 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iyoda, A. et al. Prognostic impact of large cell neuroendocrine histology in patients with pathologic stage Ia pulmonary non-small cell carcinoma. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.132, 312–315 (2006). 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rea, F. et al. Long term results of surgery and chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac Surg.14, 398–402 (1998). 10.1016/S1010-7940(98)00203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyoda, A. et al. Clinicopathological features and the impact of the new TNM classification of malignant tumors in patients with pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol.1, 437–443 (2013). 10.3892/mco.2013.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iyoda, A. et al. Postoperative recurrence and the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with pulmonary large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.138, 446–453 (2009). 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang, C. F. et al. Role of adjuvant therapy in a population-based cohort of patients with early-stage small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.34, 1057–1064 (2016). 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.8171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuchiya, R. et al. Phase II trial of postoperative adjuvant cisplatin and etoposide in patients with completely resected stage I–IIIa small cell lung cancer: The Japan clinical oncology lung cancer study group trial (JCOG9101). J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.129, 977–983 (2005). 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyoda, A. et al. Prospective study of adjuvant chemotherapy for pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Ann. Thorac. Surg.82, 1802–1807 (2006). 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyoda, A., Azuma, Y. & Sano, A. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: Clinicopathological and molecular features. Surg. Today50, 1578–1584 (2020). 10.1007/s00595-020-01988-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenmotsu, H. et al. Randomized phase III study of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus etoposide plus cisplatin for completely resected high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung: JCOG1205/1206. J. Clin. Oncol.38, 4292–4301 (2020). 10.1200/JCO.20.01806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyoda, A. et al. Clinical characterization of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and large cell carcinoma with neuroendocrine morphology. Cancer91, 1992–2000 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito, Y. et al. Survival after surgery for pathologic stage IA non-small cell lung cancer associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann. Thorac. Surg.92, 1812–1817 (2011). 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukuya, T. et al. Carboplatin plus weekly paclitaxel treatment in non-small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. Anticancer Res.30, 4357–4361 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenmotsu, H. et al. Effect of platinum-based chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol.75, 521–526 (2015). 10.1007/s00280-014-2670-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fournel, L. et al. Surgical management of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas: A 10 year experience. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg.43, 111–114 (2013). 10.1093/ejcts/ezs174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarkaria, I. S. et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in resected pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas: A single institution experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg.92, 1180–1187 (2011). 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenmotsu, H. et al. The risk of cytotoxic chemotherapy-related exacerbation of interstitial lung disease with lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol.6, 1242–1246 (2011). 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318216ee6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashiwabara, K., Semba, H., Fujii, S., Tsumura, S. & Aoki, R. Difference in benefit of chemotherapy between small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial pneumonia and patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res.35, 1065–1071 (2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minegishi, Y. et al. The feasibility study of carboplatin plus etoposide for advanced small cell lung cancer with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. J. Thorac. Oncol.6, 801–807 (2011). 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182103d3c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida, T. et al. Safety and efficacy of platinum agents plus etoposide for patients with small cell lung cancer with interstitial lung disease. Anticancer Res.33, 1175–1179 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Togashi, Y. et al. Prognostic significance of preexisting interstitial lung disease in Japanese patients with small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer13, 304–311 (2012). 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isobe, K. et al. Clinical characteristics of acute respiratory deterioration in pulmonary fibrosis associated with lung cancer following anti-cancer therapy. Respirology15, 88–92 (2010). 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01666.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isobe, K. et al. New risk scoring system for predicting acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia after chemotherapy for lung cancer associated with interstitial pneumonia. Lung Cancer125, 253–257 (2018). 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato, T. et al. A simple risk scoring system for predicting acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia after pulmonary resection in lung cancer patients. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.63, 164–172 (2015). 10.1007/s11748-014-0487-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omori, T. et al. Pulmonary resection for lung cancer in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Ann. Thorac. Surg.100, 954–960 (2015). 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azuma, Y. et al. Impact of accurate diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases on postoperative outcomes in lung cancer. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.71, 129–137 (2023). 10.1007/s11748-022-01868-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyoda, A., Azuma, Y., Sakamoto, S., Homma, S. & Sano, A. Surgical treatment for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer: Postoperative acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and outcomes. Surg. Today52, 736–744 (2022). 10.1007/s00595-021-02343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato, T. et al. Impact and predictors of acute exacerbation of interstitial lung diseases after pulmonary resection for lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.147, 1604-1611.e3 (2014). 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azuma, Y. et al. Impact of partial pressure of arterial oxygen and radiologic findings on postoperative acute exacerbation of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia in patients with lung cancer. Surg. Today54, 122–129 (2024). 10.1007/s00595-023-02711-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.