Abstract

Objective:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected the whole world and caused the death of more than 6 million people. The disease has been observed to have a more severe course in patients with chronic lung diseases. There are limited data regarding COVID-19 in patients with bronchiectasis. The aim of this article is to investigate the course of COVID-19 and factors affecting the clinical outcome in patients with bronchiectasis.

Material and Methods:

This study was conducted using the Turkish Adult Bronchiectasis Database (TEBVEB) to which 25 centers in Türkiye contributed between March 2019 and January 2022. The database consisted of 1035 patients, and COVID-19-related data were recorded for 606 patients.

Results:

One hundred nineteen (19.6%) of the bronchiectasis patients (64 female, mean age 57.3 ± 13.9) had COVID-19. Patients with bronchiectasis who developed COVID-19 more frequently had other comorbidities (P = .034). They also more frequently had cystic bronchiectasis (P = .009) and their Bronchiectasis Severity Index was significantly higher (P = .019). Eighty-two (68.9%) of the patients who had COVID-19 were followed up in the outpatient clinic, 27 (22.7%) in the inpatient ward and 10 (8.4%) patients in the intensive care unit. There tended to be a higher percentage of males among patients admitted to the hospital (P = .073); similarly, the mean age of the patients admitted to the hospital was also higher (60.8 vs 55.8 years for the outpatients), but these differences did not reach statistical significance (P = .071).

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study showed that severe bronchiectasis, presence of cystic bronchiectasis and worse Bronchiectasis Severity Index are associated with the development of COVID-19, but not with the severity of infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, bronchiectasis, disease severity

Main Points

Comorbidities were more common among bronchiectasis patients who contracted coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Severe bronchiectasis was more common in patients with COVID-19 than in patients without COVID-19.

The presence of bronchiectasis is not a sign of severe COVID-19 infection.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the most important pandemic of the century, affecting the whole world and causing the death of more than 6 million people.1 COVID-19 may be more lethal in patients with comorbidities.2 The disease has also been observed to have a more severe course in patients with chronic lung diseases such as COPD.3-5 There are very limited data on the course and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with bronchiectasis.6,7 In the literature, bronchiectatic changes, which have been observed mostly during the COVID-19 pandemic, have been described. Publications related to the patient population known to have bronchiectasis before the pandemic focus on the effect of the pandemic on bronchiectasis exacerbation or anxiety in patients with bronchiectasis.6,8

The aim of this study is to investigate the course of COVID-19 and the effects of demographic characteristics and disease severity in patients with bronchiectasis.

Material and Methods

Turkish Adult Bronchiectasis Database (TEBVEB) is an internet-based database where the demographic data of patients, the etiology of bronchiectasis, accompanying comorbidities, pulmonary function tests, microbiological and radiological data, and treatment are recorded. This study was conducted using the TEBVEB, to which 25 centers in Türkiye contributed between March 2019 and January 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic occurred during the time period when the study was conducted. The COVID-19-related data of our patients were recorded, and this study was completed in line with these data. All patients over 18 years of age, with symptoms such as cough, sputum production, and shortness of breath, in whom bronchiectasis was diagnosed with high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), and who consented to participate in the study were enrolled in the database. Patients with cystic fibrosis were excluded from the study. Ethics committee approval was obtained from the Trakya University Medicine Faculty Scientific Research Ethics Committee (approval number: TUTF-BAEK-2018/77, date: February 19, 2018).

This was an internet-based database, to which each participating center could register the patients’ data. The quality of the data was regularly checked by one of the investigators, and corrections and/or additional data were requested when needed and/or when available. The database included parameters related to history, demographics, clinical, radiological (chest radiogram and HRCT), and laboratory findings, bronchiectasis severity index (BSI)9 treatment and clinical outcomes.

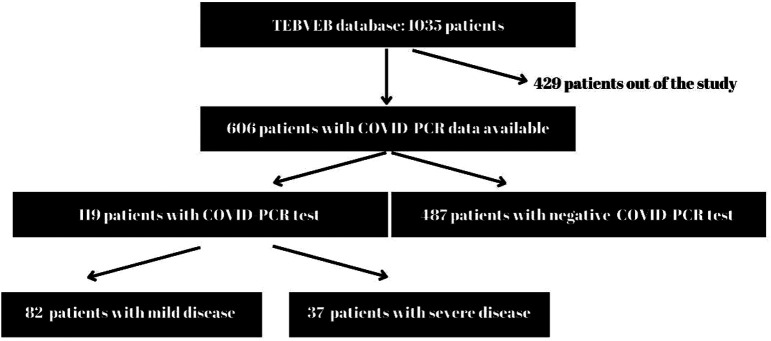

Of the 1035 patients recorded in the database, 606 patients whose COVID-PCR data were available were included in the study. Patients who were found to be COVID-PCR positive were considered to have had the disease. Patients who required hospitalization were considered to have a serious disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

Statistical Analysis

Regarding statistical analysis, the conformity of the data to the normal distribution was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the non-normally distributed variables in two groups. Relationships between categorical variables were evaluated with the chi-square comparison test. Logistic regression test was applied for risk factors that may affect the severity of COVID-19. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 24.0 program (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used in the analysis and a P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 1035 patients were registered to the bronchiectasis database. COVID-19-related data were recorded for 606 patients. Of these patients, 119 (19.6%) [64 female, mean age 57.3 ± 13.98 (23-83)] had COVID-19 disease. Patients with bronchiectasis who developed COVID-19 more frequently had other comorbidities (cardiovascular diseases, obstructive lung diseases, etc.) (P = .026). They also more frequently had cystic bronchiectasis and their Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI) was significantly higher (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Data of Bronchiectasis Patients with COVID-19

| Clinical data | Patients with COVID-19 (n = 119) | Patients Without COVID-19 (n = 487) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± S.D.) | 57.3 ± 13.9 | 55.32 ± 15.8 | .198 |

| Gender (Female) | 64 (53.8%) | 253 (52%) | .759 |

| Presence of comorbidity | 93 (78.2%) | 329 (67.6%) | .026 |

| Presence of cystic bronchiectasis | 83 (69.7%) | 276 (56.7%) | .009 |

| BSI | 7.15 ± 4.7 | 5.99 ± 4.4 | .019 |

| Presence COVID-19 vaccine | 99 (83.2%) | 366 (75.2%) | .070 |

| Mortality | 13 (11%) | 48 (9.86%) | .605 |

There was no significant difference between patients who had and those who did not have COVID-19 in terms of age, gender, smoking status, presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization, steroid use, history of frequent exacerbations, and presence of eosinophilia.

Eighty-two (68.9%) of the patients who had COVID-19 were followed up in the outpatient clinic, 27 (22.7%) in the inpatient ward, and 10 (8.4%) patients in the intensive care unit. Patients who were admitted to the ward or to the intensive care unit were considered to have severe disease. When patients with severe and mild COVID-19 were compared, no significant difference was found in terms of comorbidity, smoking status, modified medical research council (mMRC) dyspnea score, body mass index (BMI), BSI, history of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization, and presence of cystic bronchiectasis. There was a higher percentage of males (60% vs 40%) among patients admitted to the hospital, and their mean age tended to be higher (60.8 ± 11.3 vs 55.81 ± 14.82 years for the outpatients), but these differences did not reach statistical significance (P = .073 and .057 respectively) (Table 2). Parameters that may be associated with severe COVID-19 (age, gender, vaccination status, presence of comorbidities, BMI, BSI) were also evaluated with logistic regression analysis. No significant risk factor was identified.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients with Mild and Severe COVID-19

| Patients with Mild COVID-19 (n = 82) | Patients with Severe COVID-19 (n = 37) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 55.8 ± 14.82 | 60.81 ± 11.34 | .057 |

| Gender (Female) | 49 (59.8%) | 15 (40.5%) | .073 |

| Vaccinated for COVID-19 | 69 (84.1%) | 30 (81.1%) | .792 |

| Vaccinated with Biontech | 44 (53.7%) | 14 (37.8%) | .126 |

| Smoking status | 56 (69.1%) | 19 (51.4%) | .091 |

| Comorbidities | 65 (79.3%) | 28 (75.7%) | .0641 |

| Cystic bronchiectasis | 58 (70.7%) | 25 (67.6%) | .830 |

| BMI | 26.05 ± 5.88 | 26.44 ± 5.99 | .951 |

| BSI | 7.15 ± 5.07 | 7.16 ± 4.02 | .065 |

| Mortality | 5 (6.8%) | 8 (24.2%) | .022 |

BMI, body mass index.

Out of the 606 patients, 465 (76.7%) had received the COVID-19 vaccine. Of the 119 patients who developed COVID-19, 99 (84%) had been vaccinated. Similarly, 30 out of the 37 hospitalized patients (81%) had been vaccinated. Vaccination status was not found to be associated with the severity of COVID-19 (P = .73). None of the patients admitted to the intensive care unit had received the mRNA vaccine, 5 had received the inactivated vaccine, and 5 had not been vaccinated.

During the follow-up, 61 out of 606 patients (10%) died. Of the 119 patients who had COVID-19, 13 (11%) died; 2 of these (1.7%) were found to be attributable to COVID-19 infection. One of these 2 patients was not vaccinated, and the other was vaccinated with the inactivated vaccine. The causes of death in the remaining 11 patients were determined as respiratory failure due to bronchiectasis and associated COPD (n = 9) and congestive heart failure (n = 2).

Discussion

There is limited information about COVID-19 in patients with bronchiectasis. This study showed that patients with more severe bronchiectasis, as assessed by the presence of cystic bronchiectasis and by the Bronchiectasis Severity Index, more frequently developed COVID-19. Besides, male gender and older age appeared to be associated with more severe disease, as has already been shown in other studies,10 but no other variable, including the presence of other comorbidities or vaccination status, was found to be related to the severity of COVID-19.

In bronchiectasis, dilatation of the airways, dysregulated immune response, and damaged mucociliary clearance lead to an increase in the risk of infection.11 Viral infections may play a role in exacerbations of bronchiectasis.12 In a study involving 119 patients in China, viruses were detected more frequently by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) during the exacerbation period than in the stable condition.13 The most common viral agents were identified as coronaviruses, rhinovirus, and influenza. According to the report published by the European Multicenter Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC), exacerbations in patients with bronchiectasis decreased during the pandemic period. This was explained by social distance compliance and preventive measures during the pandemic.14 In another multicenter study evaluating exacerbations in patients with bronchiectasis, decreases in exacerbation rates were also found during the pandemic.6

In a cohort study investigating the frequency and course of bronchiectasis in patients with COVID-19 in Korea, bronchiectasis was found in 1.6% of the patients, and it was reported to be 1.22 times more common when compared with the general cohort.7 Bronchiectasis was present in 12 (0.8%) patients in a multicenter study involving 1500 patients with COVID-19 conducted by the Turkish Thoracic Society. It was reported that 1 of these 12 patients died (8.3%), in comparison to 66 (4.4%) of the patients without bronchiectasis. While mortality rates due to COVID-19 were found to be increased in patients with COPD and interstitial lung disease, the mortality rate in patients with bronchiectasis has not been found to be statistically different than the general population.15 The lack of a significant difference may be related to the lower numbers of patients with bronchiectasis compared with the more prevalent comorbidities.

While 69% of our bronchiectasis patients with COVID-19 had mild disease, 8% were followed up in the intensive care unit. The patients followed in the intensive care unit were either unvaccinated or vaccinated with an inactivated vaccine, as observed in another study.16 Although the majority of patients with severe COVID-19 had comorbidities, there was no significant difference in frequency compared to patients with mild disease. In a study conducted in Korea, bronchiectasis patients who had COVID-19 more frequently had comorbidities.7

This study has several limitations. First, the data on the history of COVID-19 were only available for 606 of the 1035 bronchiectasis patients recorded in the database. Second, the database included a limited number of parameters, and a more thorough analysis of all potential risk factors for severe COVID-19 could not be made. Third, as the database did not include any COVID-19 patients without bronchiectasis, we were unable to compare the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 between bronchiectasis patients and the general population. The strengths of the study are that it was conducted in a multi-center manner, COVID-19 diagnoses were microbiologically confirmed, and bronchiectasis severity was evaluated with objective parameters.

While severe bronchiectasis, the presence of cystic bronchiectasis, and a worse BSI could be identified as risk factors in the development of COVID-19, a definite finding about the clinical course of COVID-19 in this patient group has not been found. Prospective, comparative studies are needed to determine whether COVID-19 manifests more severely in patients with bronchiectasis.

Data Availability Statement

All materials described in the articlemanuscript, including all relevant raw data, will be freely available to any researcher wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes, without breaching participantparticipants’ confidentiality.

Funding Statement

Financial support was received from the Turkish Thoracic Society during the database and publication stages of the study.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Approval was obtained from Trakya University Medicine Faculty, Scientific Research Ethics Committee (approval number: TUTF-BAEK-2018/77; date: February 19, 2018).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients who agreed to take part in the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – E.Ç.E., A.Ç., A.Ş.C., A.S.; Design – E.Ç.E., A.Ş.C., D.K., E.S.U.; Supervision – A.S., E.S.U., N.K.; Resources – E.Ç.E., B.O., E.S.U.; Materials – A.Ş.C., N.K., İ.G. B.Ç.; Data Collection and/or Processing – E.Ç.E., A.Ç., D.K., A.Ş.C., S.Ç., İ.G., M.Ç.A., B.Ç., N.Ö., B.O.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – E.Ç.E., A.Ç., D.K., N.Ö., B.O.; Literature Search – E.Ç.E., A.Ç., A.Ş.C., N.Ö.; Writing – E.Ç.E., D.K., A.Ç.; Critical Review – A.S., S.Ç., B.Ç., E.S.U.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Seval Kul and Necdet Süt for their assistance in statistical evaluations.

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: TEBVEB researchers, Gülşah Günlüoğlu, Yelda Niksarlıoğlu, Adil Zamani, Serdar Berk, Serap Argun Barış, İlknur Başyiğit, Pınar Yıldız Gülhan, Mehmet Kabak, Mustafa Çolak, Oya Baydar Toprak, Huriye Berk, Kıvılcım Oğuzülgen, Ezgi Demirdöğen, Füsun Öner Eyüboğlu, Yavuz Havlucu, and Cenk Babayiğit

References

- 1.Available at: www.covid19.who.int. Date of Access: 18.9.2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ejaz H, Alsrhani A, Zafar A, et al. COVID-19 and comorbidities: deleterious impact on infected patients. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(12):1833 1839. ( 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Çakır Edis E. Chronic pulmonary diseases and COVID-19. Turk Thorac J. 2020;21(5):345 349. ( 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2020.20091) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leung JM, Niikura M, Yang CWT, Sin DD. COVID-19 and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2002108. ( 10.1183/13993003.02108-2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sheikh D, Tripathi N, Chandler TR, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with COPD hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 versus non-SARS-CoV-2 community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Med. 2022;191:106714. ( 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106714) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martínez-Vergara A, Girón Moreno RM, Olveira C, et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus Pandemic on patients with Bronchiectasis: a multicenter Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(8):1096. ( 10.3390/antibiotics11081096) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choi H, Lee H, Lee SK, et al. Impact of bronchiectasis on susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19: a nationwide cohort study. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2021;15:1753466621995043. ( 10.1177/1753466621995043) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borekci S, Vardaloglu I, Gungordu N, et al. Treatment adherence and anxiety levels of bronchiectasis patients in the COVID-19 pandemic. Med (Baltim). 2023;102(19):e33716. ( 10.1097/MD.0000000000033716) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Aliberti S, et al. The bronchiectasis severity index. An international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(5):576 585. ( 10.1164/rccm.201309-1575OC) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fang X, Li S, Yu H, et al. Epidemiological, comorbidity factors with severity and prognosis of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging. 2020;12(13):12493 12503. ( 10.18632/aging.103579) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chalmers JD, Chang AB, Chotirmall SH, Dhar R, McShane PJ. Bronchiectasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):45. ( 10.1038/s41572-018-0042-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Donnell AE. Bronchiectasis- A clinical review. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(6):533 545. ( 10.1056/NEJMra2202819) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gao Y-H, Guan W-J, Xu G, et al. The role of viral infection in pulmonary exacerbations of bronchiectasis in adults: a prospective study. Chest. 2015;147(6):1635 1643. ( 10.1378/chest.14-1961) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crichton ML, Shoemark A, Chalmers JD. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on exacerbations and symptoms in bronchiectasis: a prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(7):857 859. ( 10.1164/rccm.202105-1137LE) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kokturk N, Babayigit C, Kul S, et al. The predictors of COVID-19 mortality in a nationwide cohort of Turkish patients. Respir Med. 2021;183:106433. ( 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106433) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uzun O, Akpolat T, Varol A, et al. COVID19: vaccination vs. hospitalization. Infection. 2022;50(3):747 752. ( 10.1007/s15010-021-01751-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All materials described in the articlemanuscript, including all relevant raw data, will be freely available to any researcher wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes, without breaching participantparticipants’ confidentiality.

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a