Key Points

Question

What components are essential to include in a patient-centered definition of an atopic dermatitis flare?

Findings

In this consensus survey study of 657 US adults with atopic dermatitis (26 completing focus groups and 631 survey participants), 12 statements were agreed on for inclusion in a patient-centered definition of flare. More than half of participants aligned with their health care practitioner on what a flare is, and most reported that a patient-centered definition would be useful when communicating with their health care practitioner.

Meaning

These findings suggest that while various definitions of atopic dermatitis flare exist, a patient-centered definition may be useful for clinical practice and research.

This consensus survey study uses a modified eDelphi approach to identify a patient-centered, consensus-based working definition of atopic dermatitis.

Abstract

Importance

Flare is a term commonly used in atopic dermatitis (AD) care settings and clinical research, but little consensus exists on what it means. Meanwhile, flare management is an important unmet research and treatment need. Understanding how various therapies might comparatively improve AD flares as a measure of treatment effectiveness may facilitate shared decision-making and enable assessment of effectiveness within and outside clinical settings.

Objective

To identify patient-reported attributes associated with an AD flare to develop a patient-centered, consensus-based working definition.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This consensus survey study used a modified eDelphi method involving consensus-building focus groups and a survey conducted from January 10 through October 24, 2023. Focus groups were conducted virtually, and the online survey was advertised to National Eczema Association members. US adults aged 18 years or older with AD were recruited via convenience sampling.

Exposure

Lived experience of AD.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was consensus on which attributes of AD to include in a patient-centric definition of flare. Using a rating scale (range, 1-9), consensus for the modified eDelphi statement rating was defined as at least 70% of participants rating a statement as 7 to 9 (critical to a flare definition) and less than 15% rating it as 1 to 3 (not important).

Results

Twenty-six participants with AD who completed focus group activities (24 aged 18-44 years [92.3%] and 2 aged 45-64 years [7.7%]; 18 women [69.2%]) and 631 participants with AD (mean [SD] age, 45.5 [18.1] years; 533 women [84.5%]) who completed the survey were included in the analysis. Fifteen statements reached consensus from the focus groups, and of those, 12 reached consensus from survey participants. More than half (334 of 631 [52.9%]) of survey participants reported alignment with their health care practitioner on what a flare is, and most (478 of 616 [77.6%]) reported that a patient-centered definition would be useful when communicating with their health care practitioner about their condition.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, participants with AD reached consensus on what an AD flare means from the patient perspective. This understanding may improve research and care by addressing this key patient-centered aspect of evaluating treatment effectiveness.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory conditions, affecting over 31 million US adults and children with more than 55% experiencing inadequately controlled symptoms.1,2,3,4,5,6 Until recently, there have been limited effective and long-term therapeutic options, leaving many patients with the ongoing lived experience of periodically worsening disease and poor alleviation of burdensome symptoms.7

Flare is a term commonly used by health care practitioners (HCPs), researchers, and patients to refer to an AD disease exacerbation, although there is little consensus on the meaning of this term when it is used in clinical trials or in care settings.8,9,10 Atopic dermatitis flares may occur because of exposure to a wide variety of external triggers that are often patient specific11,12 and as a result of ongoing immune dysregulation.13 Patients with moderate to severe AD experience an average of 9 flare episodes a year, with flare intensity and duration (days to weeks) typically increasing with underlying AD severity.14 Despite the lack of a clear definition for AD flares, patients may harbor an adverse emotional burden associated with the term.15 The potential for future flares and the reoccurrence of flares contribute to considerable patient anxiety6,16 and unfavorable emotional sentiment,14 making reductions in flare frequency the second most important treatment outcome for patients with AD.7 Atopic dermatitis flares and their management are important unmet research and treatment needs.7,8,9,17

A 2014 systematic review highlighted substantial heterogeneity in how flares are defined in AD research. Among 26 studies including AD flares as outcome measures, 22 relied on arbitrary cutoffs of an existing severity scale, composite investigator-rated definitions, or behavior change (need to change therapy), with only 4 studies incorporating a patient-reported outcome.9 Efforts to standardize outcome measures for clinical trials and clinical practice, such as the Harmonizing Outcomes Measures for Eczema initiative, have pivoted to the concept of control, wherein disease activity (ie, flare-related increases in itching) is considered as one component of a multifaceted assessment for short- and long-term treatment effectiveness.18 While measures of AD control have been validated19,20 and are helpful patient-reported outcome measures for clinical trials and, potentially, care settings, patients may be interested in flare management as a component of patient-centered care. An understanding of how various therapies might comparatively prevent AD flares or reduce their intensity, number, frequency, and duration as a measure of treatment effectiveness could facilitate shared decision-making and serve as a foundation to document clinical effectiveness.7,21

Focus groups run by the National Eczema Association (NEA), a US-based patient advocacy group, identified 6 key concepts for a patient-centered definition of flare, including changes from the patient’s baseline or normal experience; mental, emotional, and social consequences; physical changes in skin; attention needed or all-consuming focus; itch-scratch-burn cycle; and control or loss of control and quality of life.22 Despite the importance of flares to patients and work to date in understanding what flares mean to people living with AD, there remains no standardized definition of AD flare from the patient perspective. The objective of this study was to identify patient-reported attributes associated with the term flare and to achieve consensus on what features are critical to defining AD flares from the patient perspective.

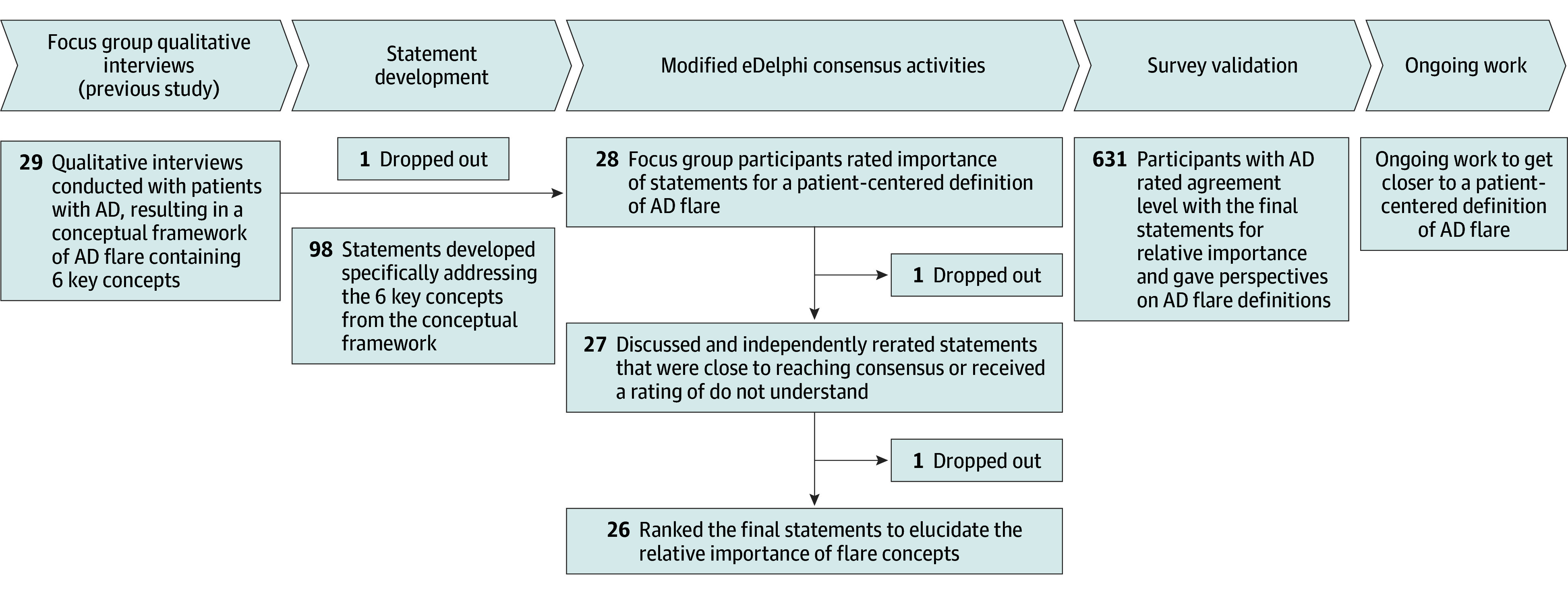

Methods

In this consensus survey study, we used a modified eDelphi process to achieve consensus among adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with AD and diverse lived experiences and demographics. The process was supplemented with a preliminary evaluation of the validity of the newly identified definition of flare based on a survey among a large, heterogeneous population of people with AD. A patient with AD who was not a participant in the study was recruited from the NEA membership to contribute the patient perspective as coauthor of this article (M.W.). Figure 1 depicts how this study fits within NEA’s overall research plan to develop a patient-centered definition of flare.

Figure 1. Diagram of the Modified eDelphi Process Within the Context of the Larger Study.

AD indicates atopic dermatitis.

The focus groups and survey were considered exempt research by the Western Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board per the Common Rule. Prior to participating in the focus group and eDelphi process consensus activities or the survey, participants provided electronic informed consent. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Statement Development

We used themes identified in our group’s previous qualitative study and the resulting conceptual framework to support focus group ratings of concepts important to AD flares.22 A list of 98 statements (eTable 1 in Supplement 1) was developed, with each statement structured as “An atopic dermatitis flare is…,” that specifically addressed each of the 6 key concepts from the conceptual framework.

Modified eDelphi Exercise

Participants and Recruitment

The same focus group from the previous qualitative study conducted from May 17 to June 3, 2022,22 participated in the modified eDelphi process consensus activities from January 10 to June 6, 2023, to determine the most and least important aspects of an AD flare. Participants were eligible for the focus group if they were aged 18 years or older and a US resident diagnosed with AD with a self-reported AD flare in the past 12 months. Participants were recruited from the NEA Ambassadors program, a volunteer program that engages patients in eczema advocacy, research, and community activities, and from the NEA’s scholarship recipient list to select patients with high engagement in and demonstrated contribution to projects.

Recruitment involved an online screening questionnaire, which collected basic demographics and AD history to allow for selection of a broad representation of the AD lived experience (eg, personal demographics and disease history). We recruited 29 participants in total, a number based on our past research experience at reaching discussion saturation. Some potential participants were excluded once proportional saturation was met for certain characteristics, such as race and ethnicity and gender. Partial completion of focus group and eDelphi process consensus activities was compensated $100 for each activity, with participants completing all 4 activities being compensated $750.

Consensus Activity 1

Consensus activity 1 was an online independent rating activity conducted using SurveyMonkey software (SurveyMonkey Inc). Participants rated the 98 statements on a scale from 1 to 9, with scores of 1 to 3 considered not important, 4 to 6 considered important but not critical, and 7 to 9 considered critically important to a definition of AD flare. A do not understand answer option was also available. The survey also asked several other questions about flaring. Consensus for a statement was defined a priori as a 70% or higher rating of 7 to 9 and less than a 15% rating of 1 to 3.

Consensus Activity 2

We regrouped online with the focus group via Zoom meeting software, version 5.10.7 (Zoom Video Communications, Inc) to discuss statements that did not reach, but were close to reaching, consensus (15 statements with a 60%-70% rating of 7-9). Following the meeting, all participants independently rerated those statements through the online survey.

Consensus Activity 3

The final consensus activity was an online exercise to rank unique pairs of the statements that reached consensus against each other to create a final ranked order of statements important to include in a definition of flare from the patient perspective. Ranking was used in a final consensus activity to elucidate the relative importance of concepts patients felt were important to include in a definition.

Survey

We created an online survey administered via Qualtrics, version 09.2023 software (Qualtrics) between September 7 and October 24, 2023. The survey assessed agreement of the broader community of patients with AD with the working concepts essential to a definition identified in the modified eDelphi exercise.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants in the survey included adults aged 18 years or older who were US residents diagnosed with AD and could speak, read, and comprehend English. The survey was disseminated via posting to the NEA website (home page, research page, and banner), email to the general NEA and Ambassador program membership, social media, the NEA print magazine, and the NEA EczemaWise smartphone and web application. Respondents who fully completed the 52- to 56-question survey (eMethods in Supplement 1) were eligible for 1 of 20 $25 online shopping gift cards. Survey responses were not linked in any way to the gift cards. All data were anonymized for analysis and treated confidentially.

We used Qualtrics’ cookies and bot detection services, such as honeypot questions and reCAPTCHA (Google LLC), to prevent duplicate entries and disingenuous responses. We further excluded respondents if they met subjective bot detection criteria during data cleaning, such as if write-in responses were off topic or phrases were repeated verbatim in another respondent write-in, if time to complete was too fast, or multiple similar submissions happened close together on days where the survey was not promoted through recruitment channels. The survey had dynamic questions based on how respondents answered.

Statement Agreement and Ranking

Survey respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement for whether the statements that reached consensus from the focus groups were critically important to include in a definition of AD (strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, or strongly agree). Consensus for a statement was defined a priori as 70% or higher indicating agree or strongly agree and less than 15% indicating disagree or strongly disagree. Statements rated as agree or strongly agree were displayed in a follow-up question where participants ranked the statements in order of importance (1 being the most important) compared with one another.

Patient Perspective of AD Flare Definition

Several survey questions were included to further understand the patient perspective of flare. We asked respondents about whether 3 existing definitions of flare resonated with them (yes or no) (previous definitions listed in the eMethods in Supplement 1), whether they and their HCP agreed on what an AD flare is (HCP alignment [yes, no, or unsure]), whether their definition of a flare changed over time (flare definition changed [yes or no]), and how they wanted or expected to use a patient-centered definition of flare (select all that apply grouped by “don’t know/unsure,” “for myself to self-manage,” “to explain my condition to family/friends,” “with a doctor to communicate about my care,” “a definition wouldn’t be useful for me,” and “other”).

Statistical Analysis

We stratified agreement rating scores of the final consensus statements shown to survey participants by patient characteristics and perspectives to visually identify within each strata for which groups the statement did not reach the agreement consensus criteria (eFigures 1-15 in Supplement 1). These variables included gender (man, woman, nonbinary, other [presented without further definition], and preferred not to say), patient age, self-selected race (Asian or Asian American, Black or African American, Native American or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, multiracial, other [presented without further definition], and did not know or preferred not to say) and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, past month AD severity, typical disease severity, worst disease severity, currently flaring, time since last flare, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, HCP alignment, flare definition changed, general knowledge of AD, urbanicity as determined by Rural-Urban Commuting Area Code23 from zip code, and education level.

For general knowledge of AD, respondents could select excellent, good, average, poor, or terrible; their responses were converted to a binary variable of average or above vs below average for analysis. Respondents who indicated being unsure of when they were diagnosed with AD (sometime in childhood, sometime in adulthood) were assigned a value of 6 (childhood) and 18 (adulthood). Respondent disease and sociodemographic variables, rating score, and ranking position score were described using means and SDs for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. The data were analyzed using R, version 4.3.2 software (R Core Team).

Results

Modified eDelphi Exercise

Of the 29 originally recruited participants,22 1 dropped out before consensus activity 1 (statement rating), a second dropped out before consensus activity 2 (discussion and rerating of the statement list), and a third dropped out before consensus activity 3 (ranking statements), yielding 26 participants (aged 18-24 years, 8 [30.8%]; aged 25-34 years, 9 [34.6%]; aged 35-44 years, 7 [26.9%]; aged 45-54 years, and 1 [3.8%]; aged 55-64 years, 1 [3.8%]) who completed the entire eDelphi process (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Of these participants, 8 (30.8%) identified as men and 18 (69.2%) as women; 10 (38.5%) as Asian or Asian American; 5 (19.2%) as Black or African American; 4 (15.4%) as Hispanic or Latino; 1 (3.8%) each as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Native American or Alaska Native; 7 (26.9%) as White; and 3 (11.5%) multiracial, other, and do not know or prefer not to say.

Activity 1 yielded 14 of the 98 statements as reaching initial consensus. After activity 2, 1 additional statement from the subgroup of 15 statements at 60% to 70% rated 7 to 9 reached consensus for a final consensus of 15 statements. Activity 3 yielded a final ranked order of those 15 statements (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Survey

Over 2 months, there were 4149 respondents to the survey. Bot detection identified 2970 entries for exclusion, leaving 1179 respondents who were eligible and consented to participate. The survey completion rate was 51.0% (601 of 1179 participants). We excluded 548 respondents who did not respond to the outcome question on statement ranking, leaving a total of 631 respondents (mean [SD] age, 45.5 [18.1] years) included for analysis. Most respondents identified as women (533 [84.5%]; 86 identified as men [13.6%] and 12 identified as nonbinary, other, or prefer not to say [1.9%]). A total of 62 (9.8%) respondents identified as Asian or Asian American, 53 (8.4%) as Black or African American, 62 (9.8%) as Hispanic or Latino, 8 (1.3%) as Native American or Alaska Native, 569 (90.2%) as non-Hispanic or Latino, 444 (70.4%) as White, 64 (10.1%) identified as multiracial, other, and not knowing or preferring not to say. The mean (SD) time since diagnosis was 24.7 (18.5) years (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Survey Study Participants .

| Characteristic | No. of participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Mean participant age, y (SD) (n = 631) | 45.5 (18.1) |

| Age category, y | |

| 18-24 | 79 (12.5) |

| 25-34 | 156 (24.7) |

| 35-44 | 94 (14.9) |

| 45-54 | 77 (12.2) |

| 55-64 | 103 (16.3) |

| ≥65 | 122 (19.3) |

| Mean age at diagnosis, mean, y (SD) | 20.7 (21.5) |

| Age at diagnosis category, y | |

| ≤17 | 355 (56.3) |

| 18-24 | 74 (11.7) |

| 25-34 | 50 (7.9) |

| 35-44 | 36 (5.7) |

| 45-54 | 42 (6.7) |

| 55-64 | 36 (5.7) |

| ≥65 | 38 (6.0) |

| Time since diagnosis, y | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.7 (18.5) |

| Category | |

| 0-5 | 111 (17.6) |

| 6-20 | 183 (29.0) |

| 21-30 | 127 (20.13) |

| ≥31 | 210 (33.28) |

| Gender (n = 631) | |

| Men | 86 (13.6) |

| Women | 533 (84.5) |

| Nonbinary, other, or preferred not to saya | 12 (1.9) |

| Race | |

| Asian or Asian American | 62 (9.8) |

| Black or African American | 53 (8.4) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 8 (1.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) |

| White | 444 (70.4) |

| Multiracial | 39 (6.2) |

| Otherb | 16 (2.5) |

| Did not know or preferred not to say | 9 (1.4) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 62 (9.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 569 (90.2) |

| Urbanicity (n = 589) | |

| Metropolitan | 564 (95.8) |

| Rural | 25 (4.2) |

| Currently experiencing an AD flare (n = 630) | |

| Yes | 345 (54.8) |

| No | 285 (45.2) |

| RECAP score (n = 612), mean (SD)c | 12.8 (7.3) |

| Past month severity of AD (n = 610) | |

| Clear | 40 (6.6) |

| Mild | 207 (33.9) |

| Moderate | 242 (39.7) |

| Severe | 121 (19.8) |

| Typical severity (n = 610) | |

| Clear | 40 (6.6) |

| Mild | 197 (32.3) |

| Moderate | 268 (43.9) |

| Severe | 105 (17.2) |

| Worst severity (n = 610) | |

| Clear | 5 (0.8) |

| Mild | 20 (3.3) |

| Moderate | 99 (16.2) |

| Severe | 486 (79.7) |

| Self-rated general knowledge of AD (n = 610) | |

| Average or above | 583 (95.6) |

| Below average | 27 (4.4) |

| Education (n = 601) | |

| <High school | 1 (0.2) |

| Completed some high school | 6 (1.0) |

| High school graduate | 43 (7.2) |

| Technical postsecondary | 42 (7.0) |

| Completed some college | 115 (19.1) |

| 4-y College degree | 210 (34.9) |

| Master’s or doctoral degree | 184 (30.6) |

Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; RECAP, Recap of Atopic Eczema.

No further information was asked.

Participants were asked to specify with write-in responses.

RECAP scores range from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating decreased AD control.

More than 40% of participants (268 of 610 participants [43.9%]) reported having moderately severe AD vs 197 reporting mild AD (32.3%) and 105 reporting severe AD (17.2%). A total of 345 of 630 participants (54.8%) reported that their AD was currently flaring (Table 1). The majority of participants (583 of 610 [95.6%]) described their general knowledge of AD as average or above average.

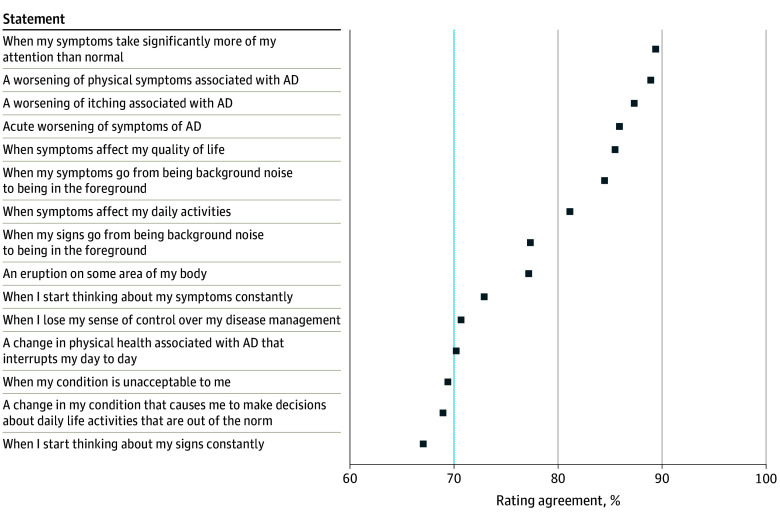

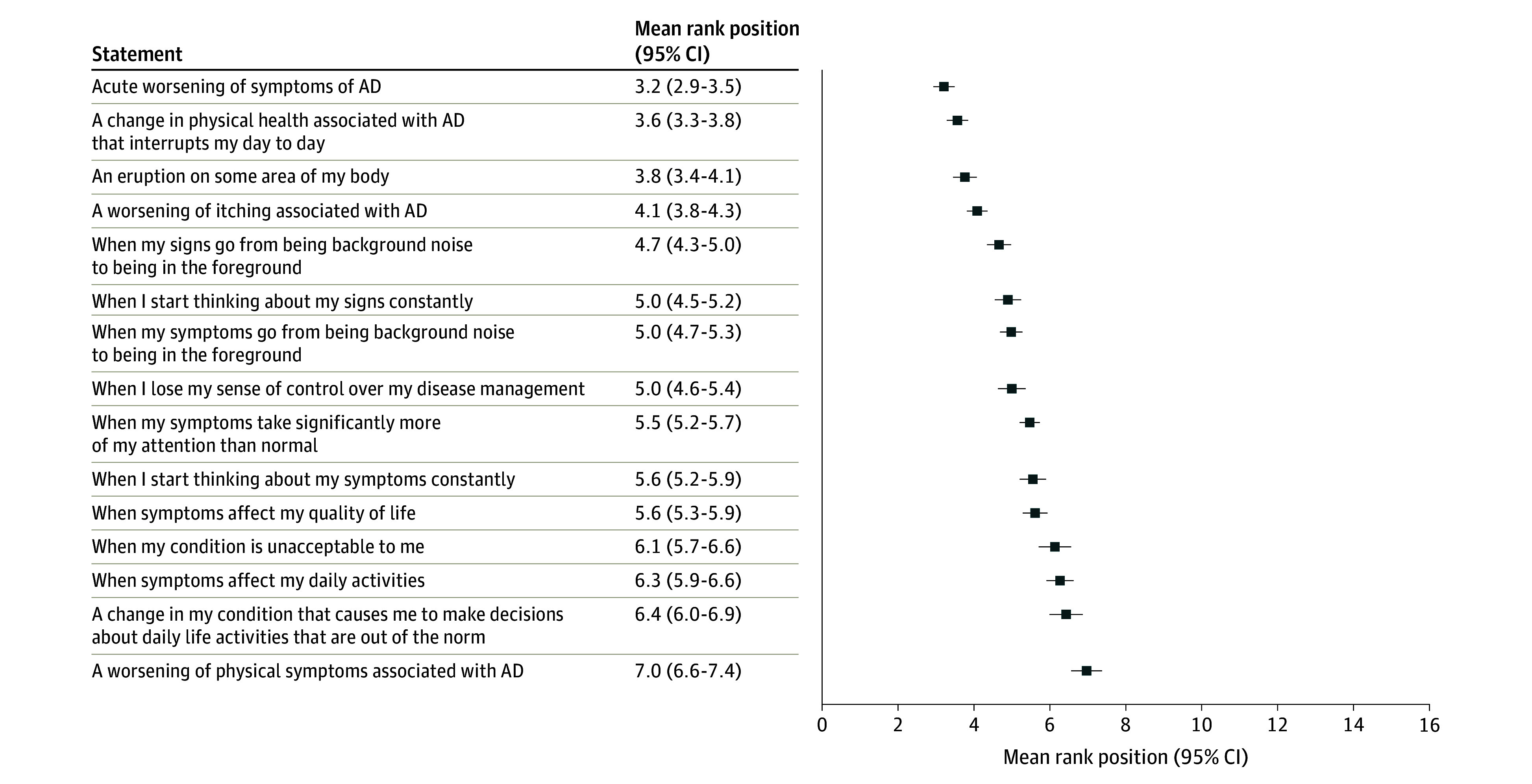

Survey Statement Agreement and Ranking

Consensus was reached for 12 of the 15 statements (Figure 2). The 3 statements that did not reach consensus were “when I start thinking about my signs constantly,” “when my condition is unacceptable to me,” and “a change in my condition that causes me to make decisions about daily life activities that are out of the norm.” The 3 statements with the highest agreement were “when my symptoms take significantly more of my attention than normal,” “a worsening of physical symptoms associated with AD,” and “a worsening of itching associated with AD.” Ranking scores (that determine ranking order) are shown in Figure 3. The statement “acute worsening of symptoms of AD” was ranked most important compared with the others (mean rank position, 3.2; 95% CI, 2.9-3.5), and “a worsening of physical symptoms associated with AD” was ranked the least important (mean rank position, 7.0; 95% CI, 6.6-7.4).

Figure 2. Survey Participant Agreement Rating for Each Proposed Statement on What Is Important to the Definition of an Atopic Dermatitis (AD) Flare.

Consensus was set at 70% or more of participants agreeing (dotted line).

Figure 3. Survey Participant Ranking of 15 Statements Compared With One Another.

Lower score indicates higher (more important) ranked position. AD indicates atopic dermatitis.

Stratified Analyses

Consensus results were similar across most subgroups of interest. Subgroups that consistently did not reach consensus on statements agreed upon in the larger group were those whose AD was mild (clear at its worst severity), who completed some high school (compared with graduated high school or completed some postsecondary education), and who identified as Native American or Alaska Native. These subgroups had low numbers of respondents (Table 1). The statement “when I lose my sense of control over my disease management” (eFigure 10 in Supplement 1) was close to the consensus cutoff in the overall survey population, but many subgroups did not reach consensus that it should be included.

Patient Perspective of AD Flare Definition

Most participants (503 of 631 [79.7%]) reported that at least 1 previously published definition of AD flares did not resonate with them. More than half (334 of 631 [52.9%]) agreed with their HCP on what an AD flare is, and 334 of 631 (52.9%) reported that their definition of flare did not change over time. Few participants (30 of 616 [4.9%]) did not think a patient-centered definition would be useful for them; most reported that they would use the definition to communicate with an HCP (478 of 616 [77.6%]) and/or for themselves (416 of 616 [67.5%]) to self-manage their symptoms. Nearly half (303 of 616 [49.2%]) also indicated that they would want or expect to use a patient-centered definition to explain their condition to family and friends (Table 2).

Table 2. Survey Study Distribution of Participant Perspectives of Flare.

| Perspective | No. of participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Do current flare definitions resonate? (n = 631) | |

| ≥1 Statements do not resonate | 503 (79.7) |

| All 3 statements resonate | 128 (20.3) |

| Do you and your primary eczema health care practitioner agree on what an atopic dermatitis flare is? (n = 631) | |

| Yes | 334 (52.9) |

| No | 34 (5.4) |

| Unsure | 263 (41.7) |

| Has your definition of an atopic dermatitis flare changed over time? (n = 631) | |

| Yes | 297 (47.1) |

| No | 334 (52.9) |

| How would you want to or expect to use a patient-centered definition of flare? Select all that apply. (n = 616) | |

| Don’t know or unsure (mutually exclusive answer) | 38 (6.2) |

| I don’t think a definition would be useful for me (mutually exclusive answer) | 30 (4.9) |

| For myself | 416 (67.5) |

| With a health care practitioner | 478 (77.6) |

| To explain my condition to family and friends | 303 (49.2) |

| Other, please specifya | 32 (5.2) |

Common responses included (1) better self-management and trigger identification; (2) improve understanding of differing flares; (3) inform research and learn how others describe flare; and (4) have condition better understood by public, health care practitioner, workplace, and insurers.

Discussion

The modified eDelphi process and subsequent consensus survey of US adults living with AD used in this consensus survey study resulted in 12 statements that participants agreed are critical to a conceptualization of AD flare. Statements with the most agreement were symptoms taking more attention than normal, a worsening of physical symptoms, and a worsening of itching. Statements ranked as the most important to a definition were acute worsening of AD symptoms, a change in physical health that interrupts daily living, and an eruption on the body. In contrast to previously published definitions of flare that focused solely on increased intensity of signs and symptoms of AD,14,17,24,25 participants in this study with lived experience with AD highlighted the importance of downstream consequences, including the increased attention required to manage the condition and interruption of daily activities. To improve communication and shared decision-making, clinicians should be aware of these discrepancies and elicit individual patients’ understanding of flare.

A term such as flare may seem like an intuitive concept for patients and HCPs to discuss when assessing and managing AD. The heterogeneous concepts that our study identified as critical to the definition of flare from the patient perspective indicate that flare as a single word may not convey a patient’s experience when communicating their disease state and treatment response with their HCP. Participants in our study emphasized detriments to quality of life, changes in lifestyle, and a sense of losing control over their disease as important to their conception of flare in addition to worsening of signs and symptoms. Clinician awareness of these concepts may increase empathy and understanding of the patient’s condition, build a foundation of trust, and motivate a shared management goal to regain lost control.

While we achieved consensus on 12 statements using rigorous consensus cutoffs defined a priori, even statements with the highest agreement were not deemed as critical by every participant, and some statements that did not meet the consensus threshold were believed to be critical for some participants. As such, HCPs should be aware that flare may not have the same meaning for each individual patient. Thus, during patient-HCP consultation, individualized discussion of a patient’s nuanced perspective on their flares may be necessary. The threshold for the patient’s labeling of flare may also be subject to change over time due to their ongoing disease process and lived experience.

These findings also have implications for clinical trials and clinical effectiveness research. The influential and holistic aspects of living with a chronic condition identified by patients should be taken into consideration, as care often extends beyond physical well-being into social and psychological domains and can further a shift in evidence-based medicine toward a more patient-centered approach. As we look to enhance our understanding of short- and long-term AD treatment benefits, additional efforts are needed to best characterize therapeutic effects on AD flares from the patient perspective.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study were its staged approach and use of granular focus groups among a small group of patients with AD, followed by a consensus exercise among a larger, diverse population. However, some limitations exist. Our findings may not be generalizable to all people with AD. eDelphi participants were members of NEA’s Ambassador program and, therefore, may have higher-than-average knowledge about AD and engagement with their disease. While the survey included a much larger pool of participants, the sample had a high proportion of people identifying as White and women and reporting high levels of education and average or above-average knowledge of AD. While one-third of survey participants reported having mild AD, there was a higher proportion of moderate to severe disease than in the general population, and responder bias may have yielded a population more engaged with their AD. Furthermore, our findings may not be generalizable to children or caregivers or to other countries.

Conclusions

In this consensus survey study, we identified statements that are critical to the definition of an AD flare from the patient perspective. Our findings may be useful in clinical practice to improve communication between patients and HCPs who may be using the term flare without a mutual understanding of its meaning. The findings may also be applied to the development of outcome measures focused on AD flares, which is an important treatment outcome for people with AD.

eMethods. AD Flare Definition Survey

eTable 1. List of 98 Statements, Where All Statements Begin With “An Atopic Dermatitis Flare Is…”

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Modified eDelphi Exercise

eTable 3. Fifteen Statements Identified by the Modified eDelphi Consensus Activities as Critically Important to Include in a Definition of Flare: Mean Rating and Ranking From the Focus Group

eFigure 1. Acute Worsening of Symptoms of AD

eFigure 2. An Eruption of Some Area of My Body

eFigure 3. A Change in Physical Health Associated With AD That Interrupts My Day to Day

eFigure 4. A Worsening of Itching Associated With AD

eFigure 5. When My Signs Go From Being Background Noise to Being in the Foreground

eFigure 6. When My Symptoms Go From Being Background Noise to Being in the Foreground

eFigure 7. When My Symptoms Take Significantly More of My Attention Than Normal

eFigure 8. (Did Not Meet Consensus) When I Start Thinking About My Signs Constantly

eFigure 9. When I Start Thinking About My Symptoms Constantly

eFigure 10. When I Lose My Sense of Control Over My Disease Management

eFigure 11. When Symptoms Affect My Quality of Life

eFigure 12. When Symptoms Affect My Daily Activities

eFigure 13. (Did Not Meet Consensus) When My Condition Is Unacceptable to Me

eFigure 14. (Did Not Meet Consensus) a Change in My Condition That Causes Me to Make Decisions About Daily Life Activities That Are Out of the Norm

eFigure 15. A Worsening of Physical Symptoms Associated With AD

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Hanifin JM, Reed ML; Eczema Prevalence and Impact Working Group . A population-based survey of eczema prevalence in the United States. Dermatitis. 2007;18(2):82-91. doi: 10.2310/6620.2007.06034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(1):67-73. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Naqeeb J, Danner S, Fagnan LJ, et al. The burden of childhood atopic dermatitis in the primary care setting: a report from the Meta-LARC Consortium. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(2):191-200. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.02.180225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(3):583-590. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Margolis DJ, et al. Association of inadequately controlled disease and disease severity with patient-reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(8):903-912. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei W, Anderson P, Gadkari A, et al. Extent and consequences of inadequate disease control among adults with a history of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2018;45(2):150-157. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCleary KK; Kith Collective. More than skin deep: understanding the lived experience of eczema. National Eczema Society. Accessed February 19, 2024. http://www.morethanskindeep-eczema.org/uploads/1/2/5/3/125377765/mtsd_report_-_digital_file.pdf

- 8.Langan SM, Thomas KS, Williams HC. What is meant by a “flare” in atopic dermatitis? a systematic review and proposal. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(9):1190-1196. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.9.1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langan SM, Schmitt J, Williams HC, Smith S, Thomas KS. How are eczema ‘flares’ defined? a systematic review and recommendation for future studies. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(3):548-556. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abuabara K, Margolis DJ, Langan SM. The long-term course of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):291-297. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverberg JI, Lei D, Yousaf M, et al. Association of itch triggers with atopic dermatitis severity and course in adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(5):552-559.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantor R, Silverberg JI. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(1):15-26. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1212660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuberbier T, Orlow SJ, Paller AS, et al. Patient perspectives on the management of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(1):226-232. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverberg JI, Feldman SR, Smith Begolka W, et al. Patient perspectives of atopic dermatitis: comparative analysis of terminology in social media and scientific literature, identified by a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(11):1980-1990. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340-347. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacci E, Rentz A, Correll J, et al. Patient-reported disease burden and unmet therapeutic needs in atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20(11):1222-1230. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas KS, Apfelbacher CA, Chalmers JR, et al. Recommended core outcome instruments for health-related quality of life, long-term control and itch intensity in atopic eczema trials: results of the HOME VII consensus meeting. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185(1):139-146. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson E, Eckert L, Gadkari A, et al. Validation of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT) using a longitudinal survey of biologic-treated patients with atopic dermatitis. BMC Dermatol. 2019;19(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12895-019-0095-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howells LM, Chalmers JR, Gran S, et al. Development and initial testing of a new instrument to measure the experience of eczema control in adults and children: recap of atopic eczema (RECAP). Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(3):524-536. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanamaker JR. It’s all a guessing game: part 2. National Eczema Association. Accessed December 3, 2023. https://nationaleczema.org/blog/its-all-a-guessing-game-part-2/

- 22.Dainty KN, Thibau IJC, Amog K, Drucker AM, Wyke M, Begolka WS. Towards a patient-centred definition for atopic dermatitis flare: a qualitative study of adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191(1):82-91. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljae037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. Economic Research Service; US Department of Agriculture; 2023. Accessed November 29, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/

- 24.Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ; European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis/EADV Eczema Task Force . ETFAD/EADV Eczema Task Force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2717-2744. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2151-2168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. AD Flare Definition Survey

eTable 1. List of 98 Statements, Where All Statements Begin With “An Atopic Dermatitis Flare Is…”

eTable 2. Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Modified eDelphi Exercise

eTable 3. Fifteen Statements Identified by the Modified eDelphi Consensus Activities as Critically Important to Include in a Definition of Flare: Mean Rating and Ranking From the Focus Group

eFigure 1. Acute Worsening of Symptoms of AD

eFigure 2. An Eruption of Some Area of My Body

eFigure 3. A Change in Physical Health Associated With AD That Interrupts My Day to Day

eFigure 4. A Worsening of Itching Associated With AD

eFigure 5. When My Signs Go From Being Background Noise to Being in the Foreground

eFigure 6. When My Symptoms Go From Being Background Noise to Being in the Foreground

eFigure 7. When My Symptoms Take Significantly More of My Attention Than Normal

eFigure 8. (Did Not Meet Consensus) When I Start Thinking About My Signs Constantly

eFigure 9. When I Start Thinking About My Symptoms Constantly

eFigure 10. When I Lose My Sense of Control Over My Disease Management

eFigure 11. When Symptoms Affect My Quality of Life

eFigure 12. When Symptoms Affect My Daily Activities

eFigure 13. (Did Not Meet Consensus) When My Condition Is Unacceptable to Me

eFigure 14. (Did Not Meet Consensus) a Change in My Condition That Causes Me to Make Decisions About Daily Life Activities That Are Out of the Norm

eFigure 15. A Worsening of Physical Symptoms Associated With AD

Data Sharing Statement