Abstract

Introduction

Risankizumab has demonstrated a favourable safety profile in patients with psoriatic disease (moderate-to-severe psoriasis [PsO] and psoriatic arthritis [PsA]). We evaluated the long-term safety of risankizumab in psoriatic disease.

Methods

Long-term safety was evaluated by analysing data from 20 (phase 1–4) clinical trials for plaque PsO and four (phase 2–3) trials for PsA. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and AEs in areas of special interest were reported among patients receiving ≥ 1 dose of risankizumab. Exposure-adjusted event rates were presented as events (E) per 100 patient-years (PY).

Results

The long-term safety data analyses included 3658 patients with PsO (13,329.3 PY) and 1542 patients with PsA (3803.0 PY). The median (range) treatment duration for patients with PsO and PsA was 4.1 (0.2–8.8) years and 2.8 (0.2–4.0) years, respectively. In the PsO population, rates of TEAEs, serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation were 145.5 E/100 PY, 7.4 E/100 PY and 1.9 E/100 PY, respectively; in the PsA population, these rates were 142.6 E/100 PY, 8.6 E/100 PY, and 1.8 E/100 PY, respectively. The rates of serious infections (excluding COVID-19-related infections) in the PsO and PsA populations were 1.2 and 1.4 E/100 PY, respectively. The rates of opportunistic infections (excluding tuberculosis and herpes zoster) were low (< 0.1 E/100 PY) in both populations. The rates of both nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and malignant tumours excluding NMSC were 0.6 and 0.5 E/100 PY in PsO and PsA, respectively, which are within the benchmarks of prior epidemiological studies. Adjudicated major cardiovascular event rates were 0.5 E/100 PY in PsO and 0.3 E/100 PY in PsA, which are within the epidemiologic reference benchmarks for both indications. No additional safety concerns were identified with this long-term exposure.

Conclusions

The results support the favourable safety profile of risankizumab for long-term treatment of psoriatic disease with no new safety concerns and similar safety profiles among both PsO and PsA populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-024-01238-5.

Keywords: IL-23, Long-term safety, Psoriasis, Psoriatic arthritis, Risankizumab

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Risankizumab has demonstrated a favourable benefit-risk profile with long-term safety in patients with psoriasis (PsO) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) with no new indication of adverse events |

| The objective of this study was to evaluate the long-term safety of risankizumab in psoriatic disease |

| What does was learned from the study? |

| This comprehensive safety analysis included data from 20 PsO and four PsA trials; 3658 (13,329.3 patient years [PY]) patients with PsO and 1542 (3803.0 PY) patients with PsA were followed up to 8.8 and 4.0 years, respectively |

| Rates of adverse events (AEs) and AEs of special interest (infections, cardiovascular events, hypersensitivity) remained consistent with prior reports or decreased over time |

| The findings are consistent with previously reported safety of risankizumab and support its long-term use among patients with psoriatic disease |

Introduction

Psoriatic disease, which includes both psoriasis (PsO) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory condition associated with high individual and societal burden, leading to cumulative life course impairment for patients that requires long-term continuous treatment to achieve disease control. Achievement of clear or almost clear skin, combined with control of joint symptoms, is associated with improvements in the physical and psychosocial effects of psoriatic disease [1, 2]. Durability of treatment response over years can lead to sustained improvements in health-related quality of life [3, 4]. Biologics are recommended for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriatic disease, but some are associated with adverse events (AEs), such as infections.

Risankizumab is a selective interleukin (IL)-23 inhibitor that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23 and prevents interaction with its receptor [5]. Research has demonstrated that risankizumab offers durable skin clearance, improved musculoskeletal manifestations and improved quality of life, while maintaining a favourable safety profile in patients with psoriatic disease [6, 7]. Additionally, real-world studies and network meta-analyses have shown that risankizumab exhibited a favourable benefit-risk profile compared to other biologic therapies, thus validating its strong tolerability profile [8, 9].

Safety is critical in treating chronic conditions like PsO and PsA, as they require life-long treatment. The long-term safety of therapies provides valuable information on the potential risks associated with prolonged use and rare events requiring robust exposures. Data on the safety of a treatment help physicians to make informed decisions on the benefits and risks of that treatment. Short- and long-term integrated safety results (16 weeks and up to 5.9 years) of risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe PsO have been previously published [10]. The aim of the comprehensive integrated analysis presented here was to report on the extended safety findings of risankizumab across psoriatic diseases, covering a maximum duration of 8.8 years for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque PsO and 4.0 years for those with active PsA.

Methods

Patients and Study Treatment

This integrated risankizumab safety data set included data from 20 phase 1–4 plaque PsO clinical trials and four phase 2–3 PsA trials (data cut-off 25 March 2023; Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Table S1). All patients who received ≥ 1 dose of risankizumab, including all administered doses between 18 to 180 mg, were included in this analysis.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were defined as any event with an onset after the first dose and within 20 weeks after the last risankizumab dose during the analysis period. AEs and AEs in areas of special interest (AESIs) were assessed and recorded through the end of exposure (last dose–first dose + 5 half-lives [20 weeks]).

AESIs included serious infections, opportunistic infections, active tuberculosis, herpes zoster, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC; including basal cell carcinoma [BCC]-to-squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] ratio), malignant tumours excluding NMSC, adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; defined as cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke), suicidal ideation and behaviour (SIB; the enrolment criteria for the risankizumab clinical trials did not exclude patients with a history of SIB), hepatic events, inflammatory bowel disease, serious hypersensitivity reactions (including anaphylactic reactions) and injection site reactions. TEAEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedRA version 25.1. https://admin.meddra.org/sites/default/files/guidance/file/whatsnew_25_1_English.pdf).

The protocols for all the studies included in this analysis were approved by the Institutional Review Board or ethics committee at each participating site. All studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent before undergoing study-related procedures.

Analyses of Safety Outcomes

Exposure-adjusted event rates were reported as events per 100 patient-years (E/100 PY), and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the exact Poisson CI of the rate.

The rate of AEs during the first 6 months and then subsequent 1-year intervals were reported in time interval analysis. Both treatment-emergent and nontreatment-emergent deaths were reported. The standardised mortality ratio (SMR) was calculated as the ratio of observed treatment-emergent deaths to expected deaths using the most recent country-specific mortality data from the World Health Organisation through 2019 and adjusting for country, sex, age and length of exposure [11].

Results

Risankizumab Exposure and Baseline Characteristics

The analyses included 3658 patients (13,329.3 PY of exposure) with PsO and 1542 patients (3803.0 PY of exposure) with PsA who received ≥ 1 dose of risankizumab (at any dose). The median (range) treatment duration was 4.1 (0.2–8.8) years and 2.8 (0.2–4.0) years for the PsO and PsA populations, respectively. Treatment duration intervals are summarised in ESM Table S2.

Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. In the PsO population, most patients were male (68.4%), while an equal representation of both sexes was observed in the PsA population. Prior use of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in the PsO and PsA populations was 24.1% and 15.2%, respectively. The use of methotrexate at baseline was more prevalent among patients with PsA (59.5%) than among those with PsO (< 0.1%).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics

| Characteristics, n (%)a | Psoriasis (N = 3658, 13,329.3 PY) | Psoriatic arthritis (N = 1542, 3803.0 PY) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1156 (31.6) | 777 (50.4) |

| Male | 2502 (68.4) | 765 (49.6) |

| Age, years | ||

| < 65 | 3245 (88.7) | 1295 (84.0) |

| 65–74 | 367 (10.0) | 213 (13.8) |

| ≥ 75 | 46 (1.3) | 34 (2.2) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 22 (0.6) | 2 (0.1) |

| Asian | 572 (15.6) | 60 (3.9) |

| Black or African American | 118 (3.2) | 10 (0.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 14 (0.4) | 4 (0.3) |

| White | 2915 (79.7) | 1443 (93.9) |

| Other | 17 (0.5) | 18 (1.2) |

| Weight, kg | ||

| ≤ 100 | 2669 (73.0) | 1180 (76.5) |

| > 100 | 988 (27.0) | 362 (23.5) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 30.2 (7.03) | 30.6 (6.55) |

| Prior TNFi use | 883 (24.1) | 234 (15.2) |

| Baseline methotrexate use | 2 (< 0.1) | 918 (59.5) |

BMI Body mass index, TNFi tumour necrosis factor inhibitor, PY patient-years

aData are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated

Overview of Long-Term Safety

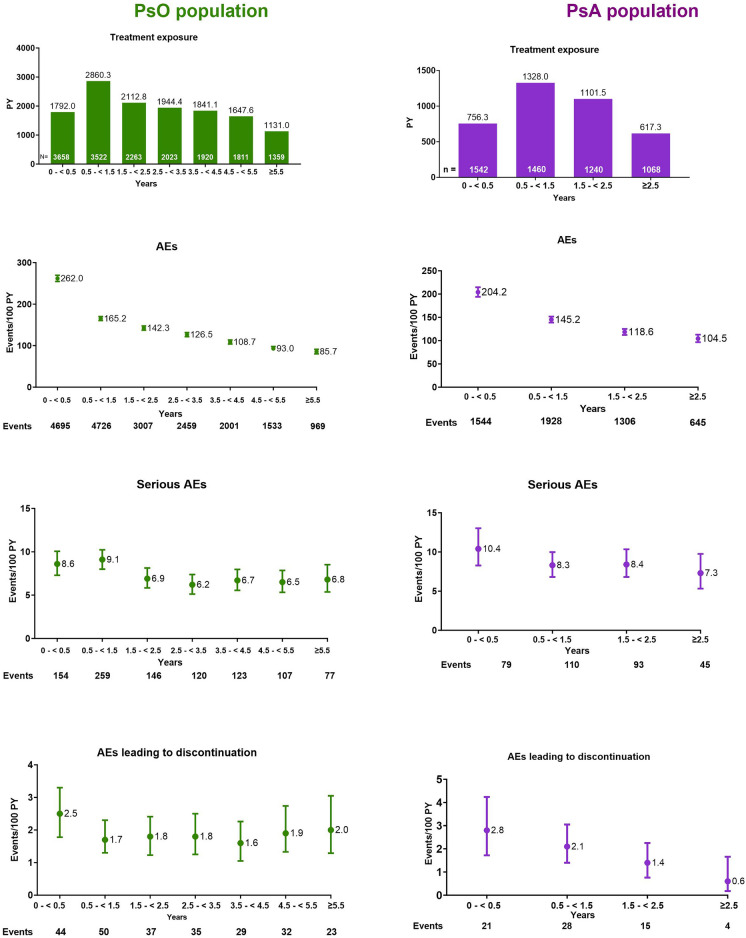

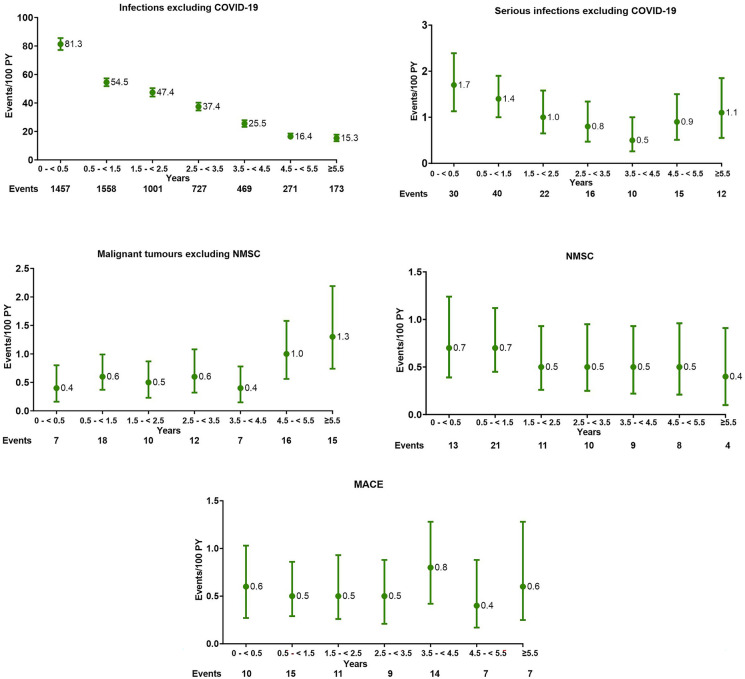

The overall rates of TEAEs, serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation were similar among the PsO and PsA populations and are summarised in Table 2. Among both PsO and PsA populations, the rates of AEs in AESIs either decreased over time or remained consistent with prior safety reports of risankizumab. The exposure-adjusted event rates were within the benchmarks from prior epidemiologic studies (Table 2; Figs. 1, 2).

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events and adverse events of special interest in the psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis populations

| Adverse events | Psoriasis (N = 3658, 13,329.3 PY) E (E/100 PY) [95% CI] |

Psoriatic arthritis (N = 1542, 3803.0 PY) E (E/100 PY) [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| AEs | 19,390 (145.5) [143.4–147.5] | 5423 (142.6) [138.8–146.4] |

| Serious AEs | 986 (7.4) [6.9–7.9] | 327 (8.6) [7.7–9.6] |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 250 (1.9) [1.7–2.1] | 68 (1.8) [1.4–2.3] |

| AEs leading to death | 37 (0.3) [0.2–0.4] | 10 (0.3) [0.1–0.5] |

| Infectionsa | 5654 (42.4) [41.3–43.5] | 1224 (32.2) [30.4–34.0] |

| Most common infections | ||

| - Nasopharyngitis | 1619 (12.1) | 217 (5.7) |

| - Upper respiratory infection | 853 (6.4) | 156 (4.1) |

| - Herpes zoster | 70 (0.5) [0.4–0.7] | 12 (0.3) [0.2–0.6] |

| Serious infectionsa | 145 (1.1) [0.9–1.3] | 55 (1.4) [1.1–1.9] |

| - Sepsis | 15 (0.1) | 3 (< 0.1) |

| - Pneumonia | 13 (< 0.1) | 7 (0.2) |

| - Urosepsis | 1 (< 0.1) | 4 (0.1) |

| - Cellulitis | 11 (< 0.1) | 3 (< 0.1) |

| Opportunistic infectionsb | 11 (< 0.1) [0.0–0.2] | 3 (< 0.1) [0.0–0.2] |

| - Tuberculosis (active) | 1 (< 0.1) [0.0–0.0] | 0 |

| - Candida infectionsc | 69 (0.5) [0.4–0.7] | 17 (0.4) [0.3–0.7] |

| Malignant tumours | 161 (1.2) [1.0–1.4] | 39 (1.0) [0.7–1.4] |

| NMSC | 76 (0.6) [0.5–0.7] | 19 (0.5) [0.3–0.8] |

| - Basal cell carcinoma | 49 (0.4) | 14 (0.4) |

| - Squamous cell carcinoma | 23 (0.2) | 5 (0.1) |

| Malignant tumours excluding NMSC | 85 (0.6) [0.5–0.8] | 20 (0.5) [0.3–0.8] |

| - Breast cancerc | 13 (< 0.1) | 3 (< 0.1) |

| - Prostate cancerc | 12 (< 0.1) | 5 (0.1) |

| - Pancreatic carcinomac | 6 (< 0.1) | 0 |

| - Renal cell carcinomac | 5 (< 0.1) | 0 |

| - Colon cancer | 5 (< 0.1) | 1 (< 0.1) |

| Adjudicated MACE | 73 (0.5) [0.4–0.7] | 13 (0.3) [0.2–0.6] |

| Serious hypersensitivity | 10 (< 0.1) [0.0–0.1] | 3 (< 0.1) [0.0–0.2] |

| Injection site reactions | 373 (2.8) [2.5–3.1] | 35 (0.9) [0.6–1.3] |

| Depression | 82 (0.6) | 27 (0.7) |

| Suicidal ideation and behaviour | 9 (< 0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

| All deathsd | 35 (0.3) [0.2–0.4] | 11 (0.3) [0.1–0.5] |

AE Adverse event, E event, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PY patient-years, TEAEs treatment-emergent adverse events

aExcluding COVID-related infections

bExcluding tuberculosis and herpes zoster

cBy group term

dIncludes non-treatment-emergent deaths

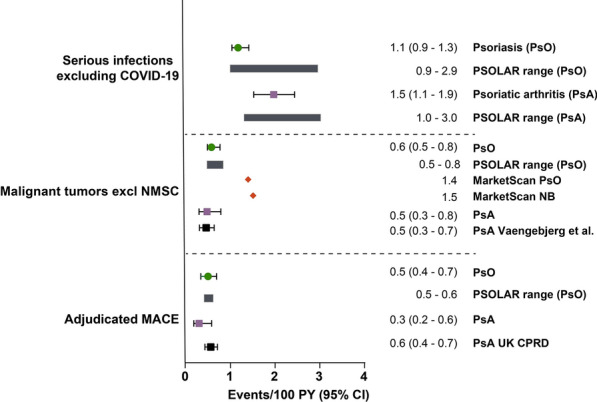

Fig. 1.

Treatment-emergent adverse events of special interest per 100 patient-years in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and reference comparators. E Events, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, NB non-biologics arm, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PsA psoriatic arthritis population, PsO psoriasis population, PSOLAR Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment Registry, PY patient-years, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, UK CPRD United Kingdom Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Reference data from PSOLAR [12–14] (range for ustekinumab, infliximab, other biologics, and non-biologics presented), MarketScan® claims data base cohort study [15], Vaengebjerg et al. [16] and UK CPRD [17]

Fig. 2.

Rate of adverse events over 6-month to 1-year intervals in the psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis populations. AE Adverse event, PsA psoriatic arthritis, PsO psoriasis, PY patient-years. Serious infections include, among others, COVID-19 and its related infections

Infections

Infections were the most reported TEAEs. Similar rates of infections excluding COVID-19 were observed in the PsO and PsA populations (42.4 and 32.2 E/100 PY, respectively; Table 2), with nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection being the most common in both studied populations. Rates of serious infections (excluding COVID-19) were also similar among the PsO (1.1 E/100 PY) and PsA (1.4 E/100 PY) populations. The most observed serious infections in both populations were sepsis, pneumonia and cellulitis, with the addition of urosepsis for PsA (Table 2). Rates of serious infections were within the reference rates for serious infections reported previously for PsO [12] and PsA [13] (Fig. 1). As most of the previous PsA trials were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, higher rates of serious infections related to COVID-19 were observed in this population and were as expected (ESM Table S3).

Opportunistic Infections

Rates of opportunistic infections (excluding tuberculosis and herpes zoster (both < 0.1 E/100 PY)) and herpes zoster (0.5 and 0.3 E/100 PY, respectively) were comparable for both PsO and PsA populations (Table 2). In the PsO population, there were 69 events of Candida infection (0.5 E/100 PY), of which eight events were considered to be possibly due to risankizumab, but none were serious. In the PsA population, there were 17 events (0.4 E/100 PY) of Candida infection, of which six events were considered to be possibly due to risankizumab, but none were serious.

The rate of active tuberculosis was < 0.1 per 100 PY in the PsO population and 0 in the PsA population. Among the PsO population, 441 patients had positive QuantiFERON Gold tests at baseline, among whom 107 were given concurrent prophylactic treatment and risankizumab for a mean duration of 3.4 years with none experiencing reactivation. Additionally, the remaining 334 patients, who did not receive prophylaxis and received risankizumab for a mean duration of 6.0 years, also did not experience reactivation. One patient with PsO was diagnosed with latent tuberculosis during screening, received prophylaxis and developed active tuberculosis 4 years later; risankizumab treatment was discontinued. In the PsA population, 313 patients had a positive test for tuberculosis, among whom 178 patients received prophylactic treatment and risankizumab for a mean duration of 2.7 years without developing reactivation. The remaining 135 patients who had a positive test for tuberculosis (and did not receive prophylaxis) were treated with risankizumab for a mean duration of 2.2 years, but none experienced reactivation.

Discontinuation of Risankizumab

A total of 250 events with PsO (1.9 E/100 PY) and 68 events with PsA (1.8 E/100 PY) were reported that led to the discontinuation of risankizumab (Table 2). The most frequently reported events for discontinuation among patients with PsO were psoriatic arthropathy (n = 15), PsO (n = 12), prostate cancer (n = 7), death (n = 6), breast cancer (n = 5), pancreatic cancer, COVID-19, pneumonia and increased alanine transaminase (ALT; n = 4, each). In the PsA population, the most frequently reported events for discontinuation were psoriatic arthropathy (n = 13), prostate cancer and skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (n = 4, each) and increased gamma-glutamyl transferase, latent tuberculosis, increased hepatic enzymes, and invasive ductal breast carcinoma (n = 2, each).

Summary of AESIs

Malignant Tumours

In the PsO population, the rate of malignant tumours excluding NMSC was 0.6 E/100 PY, and the most common tumours were prostate, pancreatic and breast cancer (Table 2; ESM Table S4). These rates were within the reference range for moderate-to-severe PsO reported in PSOLAR (0.5–0.8 E/100 PY) and the MarketScan® claims data base (overall PsO population, 1.4 E/100 PY; Fig. 1) [14, 15]. In the PsA population, the rate of malignant tumours excluding NMSC was 0.5 E/100 PY, and the most common tumours were prostate cancer and invasive ductal breast carcinoma. The rate was within the reference benchmark (0.5 E/100 PY; Fig. 1) [16]. The rate of NMSC in the PsO population (0.6 E/100 PY) was lower than that reported in the MarketScan® study (overall PsO population, 1.8 E/100 PY). The rate of NMSC in the PsA population (0.5 E/100 PY) was on the lower end of the range previously reported for real-world data from adult patients receiving approved psoriatic arthritis treatments in the MarketScan® database (0.4–6.0 E/100 PY; Fig. 1) [15]. The BCC:SCC ratio was 2.1:1 in the PsO population and 2.8:1 in the PsA population. No unexpected malignancy trend was observed with risankizumab treatment for either study population.

Among 106 patients with PsO with a medical history of any malignant tumour at baseline, 11 developed NMSC and 11 developed malignant tumours excluding NMSC (1 recurrent bladder cancer; 1 recurrent laryngeal cancer; 2 recurrent breast cancer of which 1 had a reasonable possibility of being attributed to the study drug). Among 51 patients with PsA with a history of malignant tumours at baseline, four developed NMSC and one had malignant tumour excluding NMSC.

Major adverse cardiovascular events

In the PsO population, the MACE rate was 0.5 E/100 PY, including 13 treatment-emergent events of adjudicated cardiovascular (CV) deaths (which included death of unknown cause), 34 events of nonfatal myocardial infarction and 26 events of nonfatal stroke. Among patients with PsA, the MACE rate was 0.3 E/100 PY and included six events of nonfatal myocardial infarctions, four nonfatal strokes and three CV deaths (Fig. 1; ESM Table S5). The rates of MACE with risankizumab over the long-term in both populations were consistent with or slightly lower than the reference rates for MACE reported in PSOLAR (0.5–0.6 E/100 PY in patients with PsO) and in the United Kingdom Clinical Practice Research Datalink, a large, longitudinal, UK general population-based electronic medical database (0.6 E/100 PY in patients with PsA receiving disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs/biologics; Fig. 1) [12, 14, 17]. No safety concerns were noted for the other adjudicated cardiovascular events.

Hepatic Events

While drug-induced hepatic disorder is not a safety concern for patients with PsO treated with risankizumab, a higher rate of hepatic events was anticipated in the PsA population due to the higher use of methotrexate (59.5% of patients had received concomitant methotrexate). The rate of hepatic events in the PsA population was 8.1 E/100 PY. Most events constituted laboratory abnormalities, such as increased ALT (2.4 E/100 PY) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST, 1.8 E/100 PY). No grade 3 or 4 ALT elevations were judged based on the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs v.4.03 (https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_4.03.xlsx). All observed events were nonserious, and the majority were of mild to moderate severity. Among patients who had a hepatic event, 61.7% had reported methotrexate use at baseline.

Depression and SIB

The rates of depression and SIB in both studied populations are summarised in Table 2. In the PsO population, 82 events of depression (0.6 E/100 PY) were reported among 72 patients. None of the events led to the discontinuation of risankizumab. There were nine reported events of SIB occurring in eight patients (< 0.1 E/100 PY), of which three patients with psychiatric risk factors attempted suicide (< 0.1 E/100 PY) and one patient completed suicide (< 0.1 E/100 PY); this latter patient was a 55-year-old male with a medical history of smoking and alcohol use (2–4 drinks/day). The cause of death was not considered to have a reasonable possibility of being attributed to risankizumab treatment. Intentional overdose and self-injurious ideation occurred in one patient in each population (< 0.1 E/100 PY). The rate of depression (0.7 E/100 PY) and SIB (< 0.1 E/100 PY) in the PsA population was low and similar to that in the PsO population.

Serious Hypersensitivity

In the PsO population, there were ten events of serious hypersensitivity reactions (< 0.1 E/100 PY; Table 2). These included reports of eczema (n = 2), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (n = 2), urticaria (n = 2), angioedema (n = 1), drug hypersensitivity (n = 1), erythema multiforme (n = 1) and hypersensitivity (n = 1). Each of these events were confounded either by concomitant medications, including antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, lack of temporality or a negative re-challenge. In the PsA population, three patients (< 0.1 E/100 PY) experienced serious hypersensitivity (1 event each of anaphylactic reaction, hypersensitivity and immune thrombocytopenia). The event of anaphylactic reaction was considered to be related to the study drug by the investigator, and risankizumab was discontinued as anaphylaxis is a known risk of risankizumab treatment. The hypersensitivity and immune thrombocytopenia events were unrelated to risankizumab treatment, so the risankizumab dose remained unaltered.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

There was one event (< 0.1 E/100 PY) of inflammatory bowel disease in the PsO population that included worsening of ulcerative colitis in a patient with a history of the disease. In the PsA population, there was one serious AE (< 0.1 E/100 PY) of worsening of Crohn's disease. This event was not considered to be treatment-related, and the risankizumab dose was unchanged.

Injection Site Reactions

Among the PsO population, the rate of injection site reaction was 2.8 E/100 PY (Table 2), among which injection site erythema (1.1 E/100 PY), site pain (0.3 E/100 PY) and site pruritus (0.3 E/100 PY) were the most frequent AEs. Among the PsA population, the rate of injection site reaction was 0.9 E/100 PY, and the most frequent AEs were injection site erythema (0.4 E/100 PY), site pruritus (0.2 E/10 PY) and site reaction (0.1 E/100 PY).

Mortality

Overall, there were 46 deaths in patients with PsO or PsA who received risankizumab. All causes of death for both studied populations are summarised in Table S6. In the PsO population, 35 deaths (0.3/100PY), included 33 treatment-emergent deaths and two nontreatment-emergent deaths occurring ≥ 140 days after the last dose of risankizumab. The most frequent causes of treatment-emergent deaths were cardiovascular (n = 13 [adjudicated]), COVID-related (n = 7) and unknown (n = 5). In the PsA population, 11 deaths (0.3/100 PY, including 10 treatment-emergent deaths) were reported. The most frequent causes of treatment-emergent deaths were cardiovascular (n = 3 [adjudicated]) and COVID-related (n = 2).

Time Interval Analyses

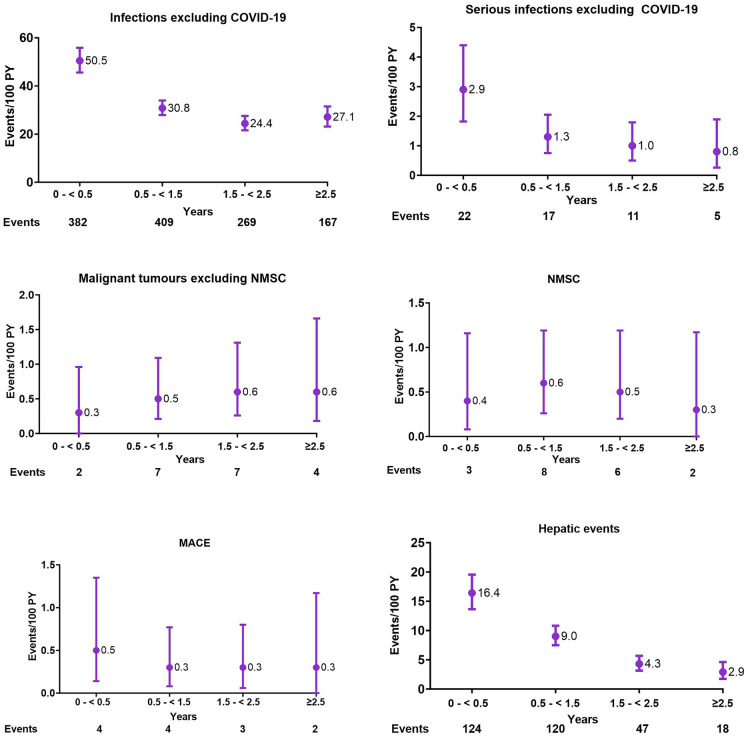

In the PsO population, the total exposure mostly remained consistent, but declined at ≥ 5.5 years, while in the PsA population, the total exposure declined at each time interval. The rate of AEs decreased from the first 6-month interval to the last recorded interval in both the PsO and PsA populations, while the rates of serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation of risankizumab remained stable over time (Fig. 2). In the PsO population, the rate of infections excluding COVID-19 reduced from 81.3 to 15.3/100 PY. The rate of malignant tumours excluding NMSC increased from 0.4 to 1.3/100 PY at the last interval; however, the 95% CIs overlapped throughout the treatment duration. The MACE rates remained stable at 0.6 E/100 PY over time (Fig. 3), which was within the reference range for PsO reported in PSOLAR (0.5–0.6 E/100 PY) and the Market® study (overall PsO population, 1.4 E/100 PY). In the PsA population, infections excluding COVID-19 rates reduced from 50.5 to 27.1/100 PY, and the MACE rates reduced from 0.5 to 0.3/100 PY. Both were within the reference range of the PSOLAR study. The rate of hepatic events reduced from 16.9 to 2.9 E/100 PY (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Rate of adverse events over 6-month to 1-year intervals in the psoriasis population. AE Adverse event, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PY patient-years

Fig. 4.

Rate of adverse events over 6-month intervals in the psoriatic arthritis population. AE Adverse event, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PY patient-years

Discussion

This comprehensive integrated safety analysis is the largest and longest safety report on risankizumab in the PsO (13329.3 PY of exposure) and PsA (3803.0 PY of exposure) population to date. Risankizumab exhibited a favourable long-term safety profile with no new safety concerns. The safety profiles were similar among both the PsO and PsA populations. These findings further support safe long-term use of risankizumab in treating psoriatic disease.

Rates of AEs over 6-month and 1-year intervals decreased or remained stable over time. The rates of serious infections with risankizumab were within the reference rates for serious infections reported for PsO and PsA [12–14]. The rate of COVID-19-related AEs in the PsA population was high, but expected, as the phase 3 PsA trials were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Biologics may affect the risk of latent tuberculosis reactivation differently. Of note, several reports of risankizumab safety in clinical trials and post-marketing studies have found that risankizumab can be used in patients with PsO and latent tuberculosis without the risk of reactivation [18–20]. Similarly, long-term evaluations of patients with PsA treated with risankizumab have not revealed any active cases of tuberculosis [21, 22]. In this integrated analysis, we did not observe an increased risk of tuberculosis reactivation in either PsO or PsA populations.

The rates of NMSC and malignant tumours excluding NMSC in our study were within reference benchmarks, suggesting that risankizumab did not measurably increase cancer risk with long-term use. Regardless, all patients should be evaluated for risk of cancer pre-treatment, during treatment and post-treatment [23, 24]. The BCC-to-SCC ratios for patients were 2.1:1 for PsO and 2.8:1 for the PsA population, indicating a low risk of drug-induced immunosuppression.

The rates of MACE with risankizumab in both PsO and PsA populations were consistent with or slightly lower than those reported in previous studies. An increased risk of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) in patients with inflammatory disorders has been previously reported [25, 26]. Long-term exposure-adjusted CVA rates in risankizumab PsO (0.2/100 PY) and PsA (0.1/100 PY) clinical trials were similar to the reference benchmarks (0.25/100 PY and 0.26/100 PY, respectively) [27]. Given the rarity and latency of CVA, data from prospective long-term multinational observational studies are considered to be a source for signal evaluation [28]. A recent analysis of CVA signals in PsO patients treated with risankizumab was published based on adverse event reports in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) database [29]. However, these findings were based on the disproportionality of drug-event pairs in the FDA adverse event reporting system, which can be misleading due to various biases and confounding factors. The CVA rates in our study were within the reference benchmarks, suggesting that CVA is not a safety concern for patients treated with risankizumab [27].

The prevalence of depressive symptoms is reported to be high among patients with PsO [30]. In this study, with long-term exposure, we observed that the rate of depression remained low (0.6 E/100 PY) among patients with PsO, and none of the depression events led to treatment discontinuation. In placebo-controlled trials, the exposure-adjusted event rates for both depression and SIB were lower in the risankizumab group compared to the placebo group [31, 32]. While event rates are not available in the literature, we can provide insights by examining the published incidence rates (IRs). The IR of depressive symptoms among patients treated with biologic agents in PSOLAR was 3.0 (95% CI 2.7–3.3) [33], and a population-based study using administrative data from two large healthcare organizations in the USA showed that the IR for suicidal ideation was 0.32 per 100 PY for the PsO-only population and 0.47 per 100 PY for the PsA population that may include patients with PsO and PsA [34]. Hence, in this long-term analysis, rates of depression and SIB were observed to be low in both studied populations.

The mortality rate was 0.3 E/100 PY among moderate-to-severe PsO and active PsA populations. The SMR for treatment-emergent deaths was 0.40 and 0.28 in the PsO and PsA populations, respectively, using 2019 data from the World Health Organisation [11]. Hence, the risk of mortality was not increased with risankizumab treatment.

Although this study provides insights into the long-term safety of risankizumab in treating psoriatic disease, a few limitations should be noted. Integrating data from multiple trials may introduce heterogeneity in patient characteristics, treatment protocols and follow-up durations. Additionally, the lack of a control group prevented the direct comparison of the safety profile of risankizumab with alternative treatments. Finally, it should be noted that there may be a tendency for healthier patients to remain in studies for an extended duration, which may introduce potential bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the rates of AEs, serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation remained consistent among both study populations throughout the observed period. AEs of special interest were comparable with reported benchmarks for PsO and PsA. The number of deaths observed was consistent with expected standard mortality rates. Thus, this comprehensive, long-term safety evaluation of risankizumab for patients with psoriatic disease provides further support for the safety profile of risankizumab and its suitability for long-term use in treating the PsO and PsA populations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Abbvie and authors thank all the trial investigators and the patients who participated in these clinical trials. Medical writing support was provided by Dalia Majumdar, PhD, and editorial support by Angela T. Hadsell, BA, both employees of AbbVie.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Ranjeeta Sinvhal, Willem Koetse. Development of methodology: Ranjeeta Sinvhal, Willem Koetse. Acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis), writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: Kenneth B Gordon, Andrew Blauvelt, Hervé Bachelez, Laura C Coates, Filip E Van den Bosch, Blair Kaplan, Willem Koetse, Doug G Ashley, Ralph Lippe, Ranjeeta Sinvhal, Kim A Papp.

Funding

Risankizumab was developed in collaboration between AbbVie and Boehringer Ingelheim. AbbVie provided financial support for the studies and participated in the design, study conduct, analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as in the writing, review and approval of this publication. All authors had access to relevant data and participated in the drafting, review and approval of this manuscript. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. AbbVie funded the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees.

Data Availability

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols, clinical study reports or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the USA and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://vivli.org/ourmember/abbvie/ then select "Home".

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The protocols for all the studies included in this analysis were approved by the Institutional Review Board or ethics committee at each participating site. All studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent before undergoing study-related procedures.

Conflict of Interest

Kenneth B Gordon has received honoraria for serving as a consultant and/or grants as an investigator from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Dermira, GSK, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, Sun and UCB. Andrew Blauvelt has served as a speaker (received honoraria) for Eli Lilly and Company and UCB; has served as a scientific adviser (received honoraria) for AbbVie, Abcentra, Aclaris, Affibody, Aligos, Almirall, Alumis, Amgen, Anaptysbio, Apogee, Arcutis, Arena, Aslan, Athenex, Bluefin Biomedicine, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Celldex, CTI BioPharma, Dermavant, EcoR1, Eli Lilly and Company, Escient, Evelo, Evommune, Forte, Galderma, HighlightII Pharma, Incyte, InnoventBio, Janssen, Landos, Leo, Lipidio, Microbion, Merck, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, Nektar, Novartis, Overtone Therapeutics, Paragon, Pfizer, Q32 Bio, Rani, Rapt, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Spherix Global Insights, Sun Pharma, Takeda, TLL Pharmaceutical, TrialSpark, UCB Pharma, Union, Ventyx, Vibliome and Xencor; has acted as a clinical study investigator (institution has received clinical study funds) for AbbVie, Acelyrin, Allakos, Almirall, Alumis, Amgen, Arcutis, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Concert, Dermavant, DermBiont, Eli Lilly and Company, Evelo, Evommune, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Leo, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, Takeda, UCB Pharma and Ventyx; and owns stock in Lipidio and Oruka. Hervé Bachelez has received honoraria or fees for serving on advisory boards, as a speaker and as a consultant and grants as an investigator from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Bayer, Baxalta, Biocad, BI, Celgene, Dermavant, Janssen, Lilly, Leo, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sandoz, Sun and UCB. Laura C Coates has received grants/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB; has worked as a paid consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, BI, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Moonlake, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB; and has been paid as a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Celgene, Galapagos, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Medac, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. Filip E Van den Bosch received consulting and/or speaker fees from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. Blair Kaplan, Willem Koetse, Doug G Ashley, Ralph Lippe and Ranjeeta Sinvhal are full-time employees of AbbVie and may own stock/stock options. Kim A Papp is a consultant and/or Speaker, and/or Investigator, and/or Scientific Officer, and/or Steering Committee Member and/or Advisory Board Member for AbbVie, Acelyrin, Akros, Amgen, Arcutis, Bausch Health/Valeant, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Can-Fite Biopharma, Celltrion, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Dermavant, Dermira, Dice Pharmaceuticals, Alumis, Eli Lilly, Evelo Biosciences, Forbion, Galderma, Horizon Therapeutics, Incyte, Janssen, Kymab, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Leo Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Pharma, Nimbus, Novartis, Pfizer, Reistone, Sanofi-Aventis/Genzyme, Sandoz, Sun Pharma, Takeda, Tarsus Pharmaceuticals, UCB and Zai Lab Co.

References

- 1.Korman NJ, Malatestinic W, Goldblum OM, et al. Assessment of the benefit of achieving complete versus almost complete skin clearance in psoriasis: a patient’s perspective. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33:733–9. 10.1080/09546634.2020.1772454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb A, Morita A, et al. The contribution of joint and skin improvements to the health-related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: a post hoc analysis of two randomised controlled studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1215. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-215003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gooderham M, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. Long-term, durable, absolute Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and health-related quality of life improvements with risankizumab treatment: a post hoc integrated analysis of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2022;36:855–65. 10.1111/jdv.18010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kristensen LE, Soliman AM, Padilla B, Papp K, Ostor A. POS1524 Durable clinically-meaningful improvements in health-related quality of life, fatigue, pain, and work productivity among patients with active psoriatic arthritis treated with risankizumab at week 100. Science. 2023;2:1123. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Kroe-Barrett RR, Canada KA, et al. Selective targeting of the IL23 pathway: generation and characterization of a novel high-affinity humanized anti-IL23A antibody. MAbs. 2015;7:778–91. 10.1080/19420862.2015.1032491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from the KEEPsAKE 1 study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;62:2113–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/keac607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Östör A, den Bosch FV, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from the KEEPsAKE 2 study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;62:2122–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keac605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong AW, Soliman AM, Betts KA, et al. Long-term benefit-risk profiles of treatments for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a network meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2021;12:167–84. 10.1007/s13555-021-00647-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Megna M, Ruggiero A, Battista T, Marano L, Cacciapuoti S, Potestio L. Long-term efficacy and safety of risankizumab for moderate to severe psoriasis: a 2-year real-life retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3233. 10.3390/jcm12093233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon KB, Lebwohl M, Papp KA, Bachelez H, Wu JJ, Langley RG, et al. Long-term safety of risankizumab from 17 clinical trials in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:466–75. 10.1111/bjd.20818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World population prospects 2019; mortality data. https://population.un.org/wpp2019/Download/Standard/Mortality/

- 12.Papp K, Gottlieb AB, Naldi L, et al. Safety surveillance for ustekinumab and other psoriasis treatments from the psoriasis longitudinal assessment and registry (PSOLAR). J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:706–14. [PubMed]

- 13.Ritchlin CT, Stahle M, Poulin Y, et al. Serious infections in patients with self-reported psoriatic arthritis from the psoriasis longitudinal assessment and registry (PSOLAR) treated with biologics. BMC Rheumatol. 2019;3:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Papp KA, Langholff W. Safety surveillance for ustekinumab and other psoriasis treatments from the psoriasis longitudinal assessment and registry (PSOLAR) errata. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:571–2. [PubMed]

- 15.Kimball AB, Schenfeld J, Accortt NA, Anthony MS, Rothman KJ, Pariser D. Cohort study of malignancies and hospitalized infectious events in treated and untreated patients with psoriasis and a general population in the United States. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1183–90 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Vaengebjerg S, Skov L, Egeberg A, Loft ND. Prevalence, incidence, and risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:421–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Li L, Hagberg KW, Peng M, Shah K, Paris M, Jick S. Rates of cardiovascular disease and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis compared to patients without psoriatic arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015;21:405–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Al-Janabi A, Warren R. Update on risankizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20:1245–51. 10.1080/14712598.2020.1822813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibba L, Gargiulo L, Vignoli CA, et al. Safety of anti-IL-23 drugs in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and previous tuberculosis infection: a monocentric retrospective study. J Dermatol Treat. 2023;34:2241585. 10.1080/09546634.2023.2241585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres T, Chiricozzi A, Puig L, et al. Treatment of psoriasis patients with latent tuberculosis using IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors: a retrospective, multinational, multicentre study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25:333–42. 10.1007/s40257-024-00845-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Östör A, den Bosch FV, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 100-week results from the KEEPsAKE 2 randomized clinical trial. Rheumatol Ther. 2024;2:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 100-week results from the phase 3 KEEPsAKE 1 randomized clinical trial. Rheumatol Ther. 2024;11:617–32. 10.1007/s40744-024-00654-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CH, Anstey AV, Barker JNWN, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for biologic interventions for psoriasis 2009. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:987–1019. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nast A, Gisondi P, Ormerod AD, et al. European S3-Guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris—Update 2015—Short version—EDF in cooperation with EADV and IPC. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2277–94. 10.1111/jdv.13354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yim KM, Armstrong AW. Updates on cardiovascular comorbidities associated with psoriatic diseases: epidemiology and mechanisms. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:326–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Sinvhal R, Krueger WS, Kilpatrick RD, Coppola D. Letter to the editor concerning the article: “Potential cerebrovascular accident signal for risankizumab: a disproportionality analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS).” Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;89:2639–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Increased reporting of cerebrovascular accidents with use of risankizumab observed in the food and drug administration adverse events reporting system (FAERS). Br J Dermatol. 2023;188:793–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Woods RH. Potential cerebrovascular accident signal for risankizumab: a disproportionality analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;89:2386–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lukmanji A, Basmadjian RB, Vallerand IA, Patten SB, Tang KL. Risk of depression in patients with psoriatic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;25:257–70. 10.1177/1203475420977477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augustin M, Lambert J, Zema C, Thompson EHZ, Yang M, Wu EQ, et al. Effect of risankizumab on patient-reported outcomes in moderate to severe psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1344–53. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.European Medicines Agency. Assessment report. Skyrizi. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/skyrizi-h-c-004759-ii-0014-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr 2024

- 33.Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong EMGJ, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in psoriasis longitudinal assessment and registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:70–80. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu JJ, Penfold RB, Primatesta P, et al. The risk of depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(7):1168-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols, clinical study reports or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the USA and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://vivli.org/ourmember/abbvie/ then select "Home".