Abstract

A Fe2+-EGTA(ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid)-H2O2 system emits photons, and quenching this chemiluminescence can be used for determination of anti-hydroxyl radical (•OH) activity of various compounds. The generation of •OH and light emission due to oxidative damage to EGTA may depend on the buffer and pH of the reaction milieu. In this study, we evaluated the effect of pH from 6.0 to 7.4 (that may occur in human cells) stabilized with 10 mM phosphate buffer (main intracellular buffer) on a chemiluminescence signal and the ratio of this signal to noise (light emission from medium alone). The highest signal (4698 ± 583 RLU) and signal-to-noise ratio (9.7 ± 1.5) were noted for pH 6.6. Lower and higher pH caused suppression of these variables to 2696 ± 292 RLU, 4.0 ± 0.8 at pH 6.2 and to 3946 ± 558 RLU, 5.0 ± 1.5 at pH 7.4, respectively. The following processes may explain these observations: enhancement and inhibition of •OH production in lower and higher pH; formation of insoluble Fe(OH)3 at neutral and alkaline environments; augmentation of •OH production by phosphates at weakly acidic and neutral environments; and decreased regeneration of Fe2+-EGTA in an acidic environment. Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system in 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.6 seems optimal for the determination of anti-•OH activity.

Keywords: chemiluminescence, Fenton system, hydroxyl radicals, pH of reaction milieu, singlet oxygen

1. Introduction

1.1. Fenton Systems as a Tool for Determination of Anti-(•OH) Activity and Limiting Buffers Interactions

Hydroxyl radicals (•OH) are very reactive and their excessive formation in the human body is involved in numerous pathological processes [1] including rheumatoid arthritis [2], neurodegenerative disorders [3], cancer [4], and atherosclerosis [4,5]. Fenton and Fenton-like reactions are the most important sources of •OH in the human body [4]; however, other processes such as the enhanced formation of peroxynitrite with its subsequent decomposition can contribute to tissue •OH overload [6]. Apart from breaking chemical reactions between H2O2 and transition metal ions (mainly Fe2+, Fe3+ Cu2+, Cu+) with the specific metal chelators, application of drugs or dietary supplements that can directly react with •OH (•OH scavengers) before their oxidative attack on cellular biomolecules seems to be a possible preventive or therapeutic approach [7]. Compounds being possible candidates for such treatment should be tested in detail in vitro before experiments on laboratory animals and clinical trials. Aqueous systems based on Fenton or Fenton-like reactions are frequently used for in vitro evaluation of the antioxidant activity. Because •OH generation can be significantly influenced by the pH of the reaction milieu [8,9], it is necessary to keep stable hydronium ions (H3O+) activity during the experiment. Changes of pH related, for instance, to the addition of a tested compound may inhibit or enhance •OH generation and lead to false results. Unfortunately, the vast majority of buffering compounds can react with •OH and, in consequence, decrease the signal-to-noise ratio and repeatability of results. For instance, organic buffers such as Tris, Tricine, and Hepes were reported to effectively scavenge •OH radicals [10]. Even bicarbonate and phosphate buffers can react with •OH radicals [11,12,13] and may inhibit •OH reactions with an appropriate probe. It should be pointed out that Fenton’s systems dedicated to the evaluation of anti-•OH activity must resemble in vivo conditions and be relatively simple to facilitate the interpretation of obtained results. Bicarbonate and phosphate buffers are the main buffers in extracellular (e.g., blood) and intracellular fluid [14], respectively. There are also other intracellular buffers such as amino-acids, proteins, and organic acids (mainly carboxylic acids) (e.g., acetic acid, lactic acid, citric acid, succinic acid) that, with their dissociated form, can stabilize pH inside the cell [14]. On the other hand, •OH radicals can effectively oxidize the aforementioned intracellular buffers [15,16]. Moreover, oxidation of some proteins and tryptophane can lead to the formation of excited carbonyl groups with a subsequent photon emission [17,18,19], making results obtained with the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system almost impossible to interpret. Therefore, phosphate buffer composed of dibasic sodium phosphate and monobasic sodium phosphate seems to be the optimal intracellular buffer that can be used for investigation of the effect of pH changes on UPE of Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

1.2. Properties of Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System Generating Ultra-Weak Chemiluminescence

We developed a system composed of Fe2+, EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid), and H2O2, which generates •OH radicals (Fenton reaction) [20]. •OH radicals can attack and cleave the ether bond in an EGTA backbone structure, leading to the formation of products containing triplet excited carbonyl groups and subsequent ultra-weak photon emissions (UPE) [20]. Measurement of photon emanation (UPE within a defined time) with a sensitive luminometer could be a measure of •OH radicals production [20]. By using this system, we were able to determine pro-oxidant (enhancing •OH production) or anti-oxidant (inhibiting •OH activity) properties of various plant polyphenols at concentrations within the range 5 µmol/L to 50 µmol/L [21] and ascorbic acid [22]. These experiments were performed in phosphate-buffered saline pH = 7.4 [20,21,22] containing 137 mmol/L NaCl, 2.7 mmol/L KCl, and 10 mmol/L phosphate. This relatively high concentration of Cl- can suppress •OH radicals’ activity before their reaction with EGTA, leading to a decrease in photon emanations and low chemiluminescence signal. Apart from the triplet excited carbonyl groups, the decay of singled oxygen (O2 (1Δg)) that is formed by a Fenton reagent (Fe2+, H2O2) could be a source of emitted photons from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system [14,23]. These photons have three characteristic bands of emission at 1270 nm, 703 nm, and 634 nm [20]. The spectral range of the luminometer used in our experiments was from 380 nm to 630 nm. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that wavelength photons of 634 nm may contribute to some extent to UPE of Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Although we excluded indirectly the significant contribution of these photons to UPE of Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system with the use of sodium azide an O2 (1Δg) scavenger [20], it would be better to complete these experiments and analyze a UPE signal from a system that specifically generated O2 (1Δg). If the luminometer is sensitive to 634 nm photons, it will lead to over- or underestimation of •OH scavenging activity of the tested compound, depending on the simultaneous reactivity with O2 (1Δg).

1.3. Aims of the Study

To better characterize the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system as a tool for measurement of anti-•OH activity, we therefore evaluated the effect of a medium composed of 10 mmol/L phosphate buffer of pH ranging from 6.0 to 7.4 on UPE, ΔUPE (increment in UPE calculated as the difference between UPE and noise), and the UPE signal-to-noise ratio (light emission from medium alone). Moreover, we analyzed the effect of the system generating O2 (1Δg) composed of H2O2 and sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) on a UPE signal as well as O2 (1Δg) decay-dependent photon emission from Fe2+-H2O2 recorded by a luminometer with a photomultiplier spectrum from 380 nm to 630 nm.

We found that the decay of O2 (1Δg) did not significantly affect the UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system and that pH = 6.6 of reaction milieu results in maximal signal-to-noise ratio being optimal for in vitro determination of anti-•OH activities of various compounds.

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Singlet Oxygen (O2 (1Δg)) Generating System (H2O2-NaOCl) on the Luminescence Signal Recorded by Luminometer with Photomultiplier Spectrum from 380 nm to 630 nm

The baseline signal (UPE of medium alone-PB pH = 6.8 with injected NaCl) was 609 ± 60 (630; 107) RLU. The addition of H2O2 or NaOCl alone did not change UPE 628 ± 74 (651; 120) RLU and 651 ± 80 (695; 133) RLU, respectively. Light emission from the O2 (1Δg) generating system (H2O2-NaOCl) reached 926 ± 245 (878; 218) RLU and the median value was 1.37-times higher than that of the baseline (Table 1). NaN3 did not suppress UPE of H2O2–NaOCl (1073 ± 105 (1102; 96) RLU). Similar results were obtained for the second series of experiments with PB pH = 6.6. H2O2–NaOCl increased median RLU 1.28 times (Table 1). However, surprisingly, light emission from H2O2-NaOCl-NaN3 was higher (p < 0.05) than that of H2O2-NaOCl.

Table 1.

Singlet oxygen (O2 (1Δg))-dependent chemiluminescence signal [RLU] recorded by a luminometer with a photomultiplier spectrum from 380 nm to 630 nm.

| No. | Sample | pH of Reaction Milieu (10 mmol/L PB) pH = 6.8 | pH of Reaction Milieu (10 mmol/L PB) pH = 6.6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Complete system H2O2-NaOCl | 926 ± 245 (878; 218) * | 809 ± 124 (827; 105) *,† |

| 2. | Complete system with O2 (1Δg) scavenger-H2O2-NaN3-NaOCl | 1073 ± 105 (1102; 96) | 930 ± 93 (974; 161) |

| 3. | Incomplete system I H2O2-NaCl | 628 ± 74 (651; 120) | 641 ± 78 (653; 129) |

| 4. | Incomplete system II H2O-NaOCl | 651 ± 80 (695; 133) | 654 ± 85 (669; 131) |

| 5. | H2O-NaN3-NaCl | 640 ± 46 (648; 50) | 636 ± 54 (643; 84) |

| 6. | H2O-NaCl | 609 ± 60 (630; 107) | 661 ± 104 (659; 101) |

| 7. | NaCl | 640 ± 47 (649; 65) | 635 ± 56 (653; 121) |

Total light emission was measured for 2 min just after the automatic injection of 100 μL of NaOCl or NaCl solution. Final sample volume 1080 μL. Results are expressed as mean and standard deviation and (median; interquartile range) of RLU. The final concentrations of H2O2, NaOCl, NaCL, and NaN3 were 2.6 mmol/L, 2.6 mmol/L, 2.6 mmol/L, and 18.5 mmol/L. *—vs. corresponding values obtained for samples No 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7—p < 0.05. †—vs. corresponding value for sample No 2—p < 0.05.

2.2. Effect of pH of Reaction Milieu on Light Emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

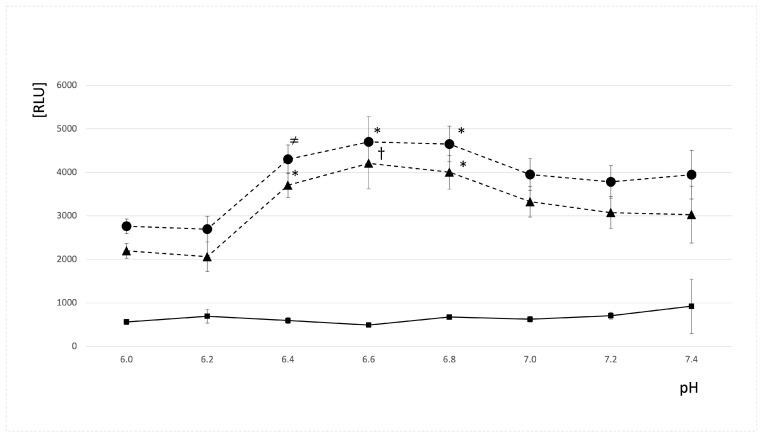

Figure 1 shows the effect of pH of reaction milieu (changes from 6.0 to 7.4) on the ratios of UPE and ΔUPE to noise. They were highest (p < 0.05) at pH 6.6 and were 9.7 ± 1.5 (9.3; 2.3) and 8.7 ± 1.5 (8.3; 2.3) (Figure 1). The UPE of the Fe2+-H2O2 system was small and ranged between 620 ± 70 RLU (at pH 6.6) and 826 ± 76 RLU (at pH 7.2) as well as the ratios of UPE of the Fe2+-H2O2 system to baseline were low at the whole studied pH range and did not exceed 1.3 (Figure 1). Similarly, UPE and ΔUPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system revealed maximal values for pH 6.6 and 6.8 (p < 0.05) 4698 ± 583 RLU (4557; 1062), 4207 ± 586 RLU (4006; 1069) and 4651 ± 410 RLU (4756; 651), 4004 ± 387 RLU (4144; 605), respectively. For higher pH, they gradually decreased (p < 0.05) and reached 3946 ± 558 RLU (3745; 465) and 3023 ± 658 RLU (2983; 544) at pH = 7.4. Lowering pH (more acidic environment) resulted in suppression of UPE and ΔUPE to values of 2696 ± 292 RLU (2674; 345) and 2001 ± 340 (1991; 198) RLU at pH 6.2 (p < 0.05) (Figure S1). More details on UPE and ratios of UPE to noise of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system and controls are shown in Tables S1 and S2 and Figure S1.

Figure 1.

Effect of pH of reaction milieu on ratios of the UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system to noise (-●-), ΔUPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system to noise (-▲-), and the UPE of the Fe2+-H2O2 system to noise (-■-). Each point represents the mean ± SD of nine series of separate experiments. *—significantly different from all corresponding values—p < 0.05. †—significantly different from corresponding values noted for pH = 6.0, 6.2, 6.6, 7.0, 7.2, and 7.4—p < 0.05. ≠—significantly different from corresponding values noted for pH = 6.0, 6.2, 6.6, 7.2, and 7.4—p < 0.05. Each point represents the mean ± SD of nine series of separate experiments.

3. Discussion

3.1. Contribution of 634 nm Photons Derived from Singlet Oxygen Decay to Maximal Signal Generated by the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

Light emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 was tested in PB with pH from 6.0 to 7.4. The maximal signal and optimal signal-to-noise ratio were observed at pH 6.6 and 6.8. In the majority of cells, the intracellular pH is within the range of 6.7 to 7.2 or even lower in some cellular organelles such as lysosomes where it reached 4.5–5.0 [24]. Therefore, our findings are relevant to conditions inside the cells where H2O2 can leak from mitochondria and is involved in intracellular signaling [25] and also reacts with iron to form •OH radicals [26]. The lowest UPE-to-noise ratio was 4.0 ± 0.8 at pH 6.2. In the case of the system generating O2 (1Δg) the UPE increased only by 1.3- and 1.4 times at pH 6.6 and 6.8 in comparison to noise (PB with the addition of NaCl). Moreover, the ratio of UPE of Fe2+-H2O2 system to noise (which depends on the formation of O2 (1Δg) did not exceed 1.3 within the pH range from 6.0 to 7.4. Therefore, the contribution of 634 nm photons from decay of O2 (1Δg) to maximal UPE is low and could not be responsible for bias during estimation of anti-•OH activity of tested compounds using the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system and light measurement with luminometer AutoLumat Plus LB 953. NaN3 is a frequently used scavenger of O2 (1Δg) especially generated by H2O2-NaClO system because it does not react with H2O2 and NaOCl [27]. NaN3 also quenched O2 (1Δg) dependent light emission from acetonitrile- H2O2 in alkaline environment [28]. We used a concentration of NaN3 comparable to that applied in the afore-mentioned experiments and therefore it is difficult to explain no inhibitory effect of this compound on the chemiluminescence of H2O2-NaOCl system. Thermal decomposition of NaN3 is accompanied by photon emanation [29] and may contribute to increased light emission from H2O2-NaN3-NaOCl samples. On the other hand, UPE of H2O-NaN3-NaCl did not differ from that of H2O-NaCl or NaCl alone making this explanation unlikely.

3.2. Effect of pH of Phosphate Buffer on Light Emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

There are two reactions responsible for the generation of •OH radicals in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

| Fe2+-EGTA + H2O2 → Fe3+-EGTA + OH− + •OH | (1) |

| Fe3+-EGTA + O2•- → Fe2+-EGTA + O2 | (2) |

Chemical reaction (2) leads to regeneration of Fe2+-EGTA complex that can enter reaction (1) to increase •OH generation, oxidative damage to EGTA and formation of excited carbonyl groups with subsequent photon emission [20].

Two other reactions can be also involved in Fe2+ regeneration [30].

| H2O2 + Fe3+-EGTA → HO2• + H+ + Fe2+-EGTA |

| HO2• + Fe3+-EGTA → O2 + H+ + Fe2+-EGTA |

The ratio of H2O2 to Fe2+ in our Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system was around 28. Thus, the availability of Fe2+ is the limiting factor for •OH formation. Therefore, the reduction of Fe3+-EGTA to Fe2+-EGTA described by reaction (2) has an important contribution to total •OH radicals generation and light emission. An increase in pH above 6.8 was accompanied by a lower UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Such conditions facilitate the formation of insoluble Fe(OH)3. Although the concentration of EGTA was 2-fold higher than that of iron ions, Fe3+ could be grabbed from the complex with EGTA and precipitated as Fe(OH)3, thus limiting Fe2+ regeneration. Five ferric hydrolysis products (Fe3+, FeOH2+, FeO2−, FeO2H and FeO+) can contribute to the total content of Fe3+ in aqueous solution shoving the complexity of chemical reactions involving Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions. The aqueous solubility of these products decreases across the pH range from 5.0 to 8.0 [31,32]. Especially Fe3+ solubility decreases from 10−8 mol/L, 7 × 10−9 mol/L to about 5 × 10−9 mol/L at pH 6.0, 6.8 and 7.0, respectively [31]. In our Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system, the concentration of Fe2+ ions was 92.6 μmol/L (mostly chelated with EGTA) and the concentration of H2O2 was 28- times higher than that of Fe2+. Assuming carefully that after injection of H2O2 to Fe2+-EGTA, only 10% of Fe2+ ions would be oxidized to Fe3+ over 2 min observation, the concentration of Fe3+ (9.26 × 10−6 mol/L) can be substantially higher than its solubility at pH 6.8 and 7.0 and result in Fe3+ precipitation and decrease in UPE of Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2.

Moreover, the reaction rate (1) depends on pH with maximal intensity at pH around 3 [33]. This may additionally elucidate the suppression of UPE when pH increased from 7.0 to 7.4. On the other hand, mean signal suppression in neutral (decrease by 1.19 times at pH 7.0) and alkaline environments (decrease by 1.24 times at pH 7.2) was not so great, taking into consideration the observation that, under these conditions, high-valent oxoiron [13,34] species are the main product of Fenton reaction. This is probably due to the presence of phosphate buffer (phosphates), which can augment •OH radicals formation even in moderate alkaline solutions [13].

Surprisingly, lowering the pH of the reaction milieu from 6.6 to 6.0 did not increase the UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Quite the contrary, light emission decreased and reached the lowest values at pH 6.2. It should be pointed out that three radicals •OH, O2-, and O2 (1Δg) are produced in Fenton’s system [33]. The reactions leading to the production of these radicals can compete with each other and increased generation of one radical may affect the intensity of the remaining two reactions [33]. Thus increased generation of •OH radicals in a more acidic environment (reaction 1) may suppress the production of O2-radicals involved in the regeneration of Fe2+ ions and finally suppress the total yield of •OH radicals. It should be pointed out that •OH radicals can react with phosphate [13] which is a potential limitation in the use of phosphate buffer to stabilize the pH of the Fenton system reaction milieu. On the other hand, the kinetics of phosphate reactions with •OH radicals is significantly lower than that of the vast majority of organic compounds [13] including other buffers such as Tris and Hepes. Moreover, phosphate buffer plays a major role in maintaining the acid-base balance inside cells [35]. The intracellular concentration of free phosphates (H2PO4− and HPO4−) is within the range of 0.5 mmol/L to 5 mmol/L [27]. In addition, concentration of labile organophosphates (e.g., phosphocreatine) is up to 20 times higher [36]. What is more, high UPE-to-noise (mean 9.7) and ΔUPE-to noise (mean 8.7) ratios at pH 6.6 suggest that scavenging of •OH radicals by phosphates did not substantially suppress light emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system which could be used for evaluation of anti-•OH radicals activity of various organic compound. Previously we tested four increasing concentrations of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system as an emitter of light under a stable ratio of Fe2+ to EGTA to H2O2 molar concentrations [20]. The optimal UPE was found for 92.6 µmol/L Fe2+-185.2 µmol/L EGTA-2.6 mmol/L H2O2 system [20]. Moreover, concentrations of 92.6 µmol/L Fe2+ and 2.6 mmol/L H2O2 correspond to some extent to the values that occur in vivo. The plasma levels of H2O2 and Fe complexed with low molecular weight compounds, can reach 50 µmol/L and 10 µmol/L in certain diseases [37,38]. It is believed that H2O2 concentrations can be even higher in a close neighborhood of activated inflammatory cells such as polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages [39]. Additionally, the subcellular iron concentration calculated per average neuron of a brain can reach around 0.6 mM/L [40].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Solutions

All chemicals were of analytical grade. Sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate (NaH2PO4·H2O), sodium phosphate dibasic heptahydrate (Na2HPO4·7H2O), iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium azide (NaN3), sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), and ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). H2O2 30% solution (w/w) was from Chempur (Piekary Slaskie, Poland). Sterile deionized pyrogen-free water (freshly prepared, resistance > 18 MW/cm, HPLC H2O Purification System, USF Elga, Buckinghamshire, UK) was used throughout the study. Working aqueous solutions of 5 mmol/L FeSO4, 20 mmol/L NaN3 and 28 mmol/L NaCl were prepared before the assay. Thirty-percent solution of H2O2 was diluted with water to a final concentration of 28 mmol/L (working H2O2 solution) and the concentration was confirmed by the measurement of the absorbance at 240 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 43.6/mol cm [41]. The stock solution of EGTA (100 mmol/L) was prepared in 10 mmol/L phosphate buffer pH = 8.0 and stored at room temperature in the dark for no longer than 3 months. A working solution of 10 mmol/L EGTA was obtained by the dilution of EGTA stock solution with water.

4.2. Effect of pH of Reaction Milieu on the Light Emission by Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

Chemical reactions of 92.6 μmol/L Fe2+-185.2 μmol/L EGTA-2.6 mmol/L H2O2 system leading to UPE were carried out in 10 mmol/L phosphate buffers with pH ranging from 6.0 to 7.4 (pH = 6.0, 6.2, 6.4, 6.6, 6.8, 7.0, 7.2, and 7.4). UPE was measured with a multitube luminometer (AutoLumat Plus LB 953, Berthold, Germany) equipped with a Peltier-cooled photon counter (spectral range from 380 to 630 nm) to ensure high sensitivity and low and stable background noise signal. An amount of 10 mmol/L phosphate buffers with aforementioned pH were prepared following the prescription of AAT Bioquest (https://www.aatbio.com/resources/buffer-preparations-and-recipes/phosphate-buffer-ph-5-8-to-7-4, accessed on 19 August 2024). For instance, 10 mmol/L phosphate buffer (PB) pH = 6.0 was prepared by addition of 36.704 mg of Na2HPO4·7H2O and 0.119 mg of NaH2PO4·H2O to 80 mL of water, pH was adjusted to 6.0 with HCl and then distilled water was added to the final volume of 100 mL. Other buffers were done in the same way and amounts of Na2HPO4·7H2O and NaH2PO4·H2O were taken from AAT Bioquest page and pH was adjusted to the desired value with HCl or NaOH solutions. Briefly, 20 μL of 10 mmol/L EGTA solution was added to the tube (Lumi Vial Tube, 5 mL, 12 × 75 mm, Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) containing 940 μL of PB (pH = 6.0). Then, 20 μL of 5 mmol/L solution of FeSO4 was added, and after gentle mixing, the tube was placed in the luminometer chain and incubated for 10 min in the dark at 37 °C. Then, 100 μL of 28 mmol/L H2O2 solution was added by an automatic dispenser and the total light emission (expressed in RLU) was measured for 120 s. The final concentrations of FeSO4, EGTA, and H2O2 in the reaction mixture were 92.6 µmol/L, 185.2 µmol/L, and 2.6 mmol/L, respectively. For experiments with other buffers (pH = 6.2, 6.4, 6.6, 6.8, 7.0, 7.2, and 7.4), the procedure was the same. Controls included: incomplete system I (Fe2+-H2O2 in PB); incomplete system II (EGTA-H2O2 in PB); H2O2 alone in PB; Fe2+ and EGTA in PB without H2O2; and medium alone (Table 2).

Table 2.

Design of experiments on the effect of pH of reaction milieu on light emissions by the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

| No. | Sample | Working Solutions Added to Luminometer Tube (µL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-PB | B-EGTA | C-FeSO4 | D-H2O | E-H2O | ||

| 1. | Complete system | 940 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 0 |

| 2. | Incomplete system I | 960 | 0 | 20 | 100 | 0 |

| 3. | Incomplete system II | 960 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 4. | H2O2 alone | 980 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 5. | Fe2+ + EGTA without H2O2 | 940 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 100 |

| 6. | Medium alone | 980 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

Working solutions were mixed in alphabetical order. (A)—10 mM phosphate buffer (PB) with increasing pH from 6.0 to 7.4 (pH = 6.0, 6.2, 6.4, 6.6, 6.8, 7.0, 7.2, and 7.4); (B)—10 mmol/L aqueous solution of ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), and (C)—5 mmol/L solution of FeSO4. Then, after gentle mixing the tube was placed into a luminometer chain, incubated for 10 min at 37 °C and then (D)—28 mmol/L aqueous solution of H2O2 or (E)—H2O was automatically injected with dispenser and total light emission was measured for 2 min.

4.3. Effect of H2O2–NaOCl System on the Luminescence Signal Recorded by Luminometer with Photomultiplier Spectrum from 380 nm to 630 nm

During chemical reactions, three radicals are generated in the Fenton system [33]. One of them is O2 (1Δg) that after decay may emit photons with three bands (634 nm, 703 nm, and 1270 nm). The band of 634 nm is close to the upper border of the luminometer spectrum and may affect •OH—dependent UPE signal giving false positive results in our experiments. However, production of O2 (1Δg), in Fenton systems is much less intensive than generation of •OH radicals [42,43,44]. Therefore, to study the effect of O2 (1Δg) on the chemiluminescence signal we choose H2O2-NaOCl system a very effective generator of O2 (1Δg) [45]. The pH of chemical reaction environments 6.6 and 6.8 was chosen based on the results of experiments on effect of pH of reaction milieu on the light emission by Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. UPE and ΔUPE (UPE minus baseline) reached the highest values at pH 6.6 and 6.8. To estimate this plausible effect, 100 µL of 28 mmol/L H2O2 solution was added to the tube containing 880 μL of 10 mmol/L PB pH = 6.8 and after gentle mixing the tube was placed in the luminometer chain and incubated for 10 min in the dark at 37 °C. Then, 100 μL of aqueous solution of 28 mmol/L NaOCl was added using an automatic dispenser and the total light emission (expressed in RLU) was measured for 120 s. It should be pointed out that NaOCl solution was prepared in ice-cold water and kept in an ice bath throughout the whole experiment. The final concentrations of H2O2 and NaOCL were 2.6 mmol/L. The design of these experiments and control systems are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Design of experiments on the effect of singlet oxygen (O2 (1Δg)) generating system (H2O2-NaOCl) on the luminescence signal recorded by luminometer with photomultiplier spectrum from 380 nm to 630 nm.

| No. | Sample | Volumes of Working Solutions Added to Luminometer Tube (μL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-PB | B-H2O2 | C-H2O | D-NaN3 | E-NaOCl | F-NaCl | ||

| 1. | Complete system | 880 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 2. | Incomplete system I | 880 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 3. | Complete system + NaN3 | 780 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| Additional control | |||||||

| 4. | Incomplete system II | 880 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 5. | Medium alone | 880 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 6. | Medium + NaN3 | 780 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| 7. | PB alone | 980 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

Working solutions were mixed in alphabetical order. (A)—10 mM phosphate buffer (PB) (pH = 6.8); (B)—28 mmol/L solution of H2O2, (C)—distilled water, (D)—20 mmol/L NaN3—an O2 (1Δg) scavenger, then after gentle mixing, the tube was placed into a luminometer chain, incubated for 10 min at 37 °C, and then (E)—28 mmol/L aqueous solution of NaOCl or (F)—28 mmol/L NaCl (additional controls) was automatically injected with dispenser and total light emission was measured for 2 min.

4.4. Statistical Analyses

Results obtained from 9 series of separate experiments are expressed as means (standard deviations) and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) of relative light units (RLU). The following parameters were recorded and calculated: UPE (ultra-weak photons emission)—total light emission within the first two minutes after the addition of H2O2 or H2O and NaOCl or NaCl, increment in UPE (ΔUPE = UPE of a given system—UPE of buffer alone (noise), and the ratio of UPE (or ΔUPE) of a given system to noise when pH of reaction milieu increased from 6.0 to 7.4. The comparisons between the UPE and ΔUPE and their ratios to noise observed in different pH of reaction milieu were analyzed with the independent-samples (unpaired) t-test or Mann–Whitney U test depending on the data distribution, which was tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov–Liliefors test. The Brown–Forsythe test for analysis of the equality of the group variances was used prior to the application of the unpaired t-test and if variances were unequal, the Welch’s t-test was used instead of the standard t-test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

5. Conclusions

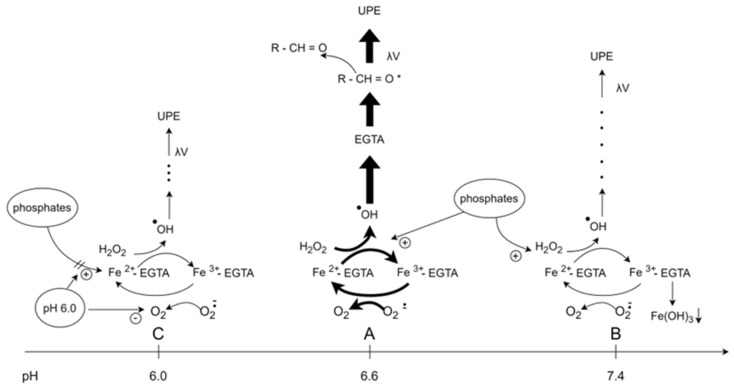

We found that •OH radicals-induced light emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system is highest at pH 6.6 stabilized with 10 mmol/L phosphate buffer. Both increase in pH within the range of 6.8 to 7.4 and decrease from 6.4 to 6.0, resulting in suppression of UPE and a decrease in the UPE-to-noise ratio. The following processes summarized in Figure 2 may be responsible for this phenomenon;

Figure 2.

The proposed mechanisms for the effect of pH changes from 6.0 to 7.4 of reaction milieu on UPE of 92.6 μmol/L Fe2+-185.2 μmol/L EGTA-2.6 mmol/L H2O2 system. The pH range from 6.0 to 7.4 was studied. (A)—Under conditions of pH = 6.6 the UPE (ultra weak photon emission) was maximal. Hydroxyl radicals (•OH) generated in the reaction of Fe2+-EGTA with H2O2 (Fenton reaction) attack one of the ether bonds in the backbone structure of EGTA resulting in the formation of product with triplet excited carbonyl group (R-CH = O*). Electronic transitions from the triplet excited state to the ground state is accompanied by the photon emission (λν). Superoxide radicals (O2.−) produced simultaneously in the Fenton system reduce Fe3+-EGTA to Fe2+-EGTA that again enters the Fenton reaction increasing a number of emitted photons. Additionally, phosphate anions (H2PO4−/HPO42−) augment the intensity of the Fenton reaction. (B)—When pH increased from 6.6 to 7.4, the rate of the Fenton reaction decreased and part of Fe3+ formed insoluble Fe(OH)3 and less Fe2+-; EGTA is available for reaction with H2O2. Although the rate of Fenton reaction is still stimulated by H2PO4−/HPO42−, the net formation of •OH is decreased and UPE lowered. (C)—A decrease in pH from 6.6 to 6.0 resulted in a moderate increase in the rate of the Fenton reaction, while the stimulatory effect of H2PO4−/HPO42− phosphate anions was abolished. Parallel production of O2- is decreased and in consequence, regeneration of Fe2+-EGTA diminished. The net yield of •OH production is decreased and less R-CH = O* is formed with subsequent emission of photons. Thus, the UPE is lower than that observed under the condition of pH = 6.6.

Enhancement and inhibition of •OH production in lower and higher pH, respectively.

Formation of insoluble and non-reactive Fe(OH)3 at neutral and alkaline environment.

Enhancement of •OH production by phosphates at weakly acidic and neutral environments.

Suppression of O2•-production in acidic environment with decreased intensity of Fe2+-EGTA complex regeneration.

Phosphates are the main intracellular buffer and the pH range investigated in our study occurs in human body cells. Therefore, the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system with pH 6.6 stabilized with PB resembles intracellular conditions and seems optimal for the determination of anti-•OH activity of the variety of water-soluble organic compounds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules29174014/s1. Table S1. Ultra weak photon emission (UPE) from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system and appropriate controls depending on the pH of reaction milieu. Table S2. Effect of pH of reaction milieu on ratios of UPE of Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 to noise, increment in UPE of Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 (ΔUPE) to noise and UPE of Fe2+-H2O2 to noise. Figure S1. Effect of pH of reaction milieu on UPE (ultra weak photon emission) (-●-) and ΔUPE (UPE minus baseline) (-▲-) of Fe2+-EGTA- H2O2 system, Fe2+-H2O2 (-■-). *—significantly different from corresponding values noted for pH = 6.0, 6.2, 7.0, 7.2 and 7.4—p <0.05. †—significantly different from corresponding values noted for pH = 6.0, 6.2, 6.4, 7.0, 7.2 and 7.4—p < 0.05. ≠—significantly different from corresponding values noted for pH = 6.0, 6.2 and 7.2—p < 0.05. Each point represents the mean ± SD of nine series of separate experiments.

Author Contributions

K.S., W.T. and D.N. conceived and designed the experiments. K.S., A.S. and A.W. performed the experiments. K.S. and M.N. analyzed the data. K.S., M.N., A.S., A.W. and D.N. contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. K.S., W.T. and D.N. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, the decision to publish the results or the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by 503/1-079-01/503-11-001 Medical University Lodz.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Bergendi L., Benes L., Duracková Z., Ferencik M. Chemistry, physiology and pathology of free radicals. Life Sci. 1999;65:1865–1874. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Islam S., Mir A.R., Arfat M.Y., Khan F., Zaman M., Ali A., Moinuddin F. Structural andimmunological characterisation of hydroxyl radical modified human IgG: Clinicalcorrelation in rheumatoid arthritis. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. BiomolSpectrosc. 2018;194:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jomova K., Vondrakova D., Lawson M., Valko M. Metals, oxidative stress andneurodegenerative disorders. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2010;345:91–104. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jomova K., Valko M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology. 2011;283:65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng F.C., Jen J.F., Tsai T.H. Hydroxyl radical in living systems and its separation methods. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2002;781:481–496. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckman J.S., Beckman T.W., Chen J., Marshall P.A., Freeman B.A. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: Implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipinski B. Hydroxyl radical and its scavengers in health and disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2011;2011:809696. doi: 10.1155/2011/809696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung Y.S., Lim W.T., Park J.Y., Kim Y.H. Effect of pH on Fenton and Fenton-like oxidation. Environ. Technol. 2009;30:183–190. doi: 10.1080/09593330802468848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y., Miller C.J., Waite T.D. pH dependence of hydroxyl radical, ferryl, and/or ferric peroxo species generation in the heterogeneous Fenton process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:1278–1288. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c05722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hicks M., Gebicki J.M. Rate constants for reaction of hydroxyl radicals with Tris, Tricine and Hepes buffers. FEBS Lett. 1986;199:92–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81230-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao C., Kang S.F., Wu F.A. Hydroxyl radical scavenging role of chloride and bicarbonate ions in the H2O2/UV process. Chemosphere. 2001;44:1193–1200. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Illés E., Patra S.G., Marks V., Mizrahi A., Meyerstein D. The FeII(citrate) Fenton reaction under physiological conditions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020;206:111018. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2020.111018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H.Y. Why the reactive oxygen species of the Fenton reaction switches from oxoiron(IV) species to hydroxyl radical in phosphate buffer solutions? A computationalrationale. ACS Omega. 2019;4:14105–14113. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b02023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall J.E., Guyton A.C. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 11th ed. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2006. pp. 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gligorovski S., Strekowski R., Barbati S., Vione D. Environmental implications of hydroxyl radicals ((•)OH) Chem. Rev. 2015;115:13051–13092. doi: 10.1021/cr500310b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hullar T., Anastasio C. Yields of hydrogen peroxide from the reaction of hydroxyl radical with organic compounds in solution and ice. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:7209–7222. doi: 10.5194/acp-11-7209-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pospíšil P., Prasad A., Rác M. Mechanism of the formation of electronically excited species by oxidative metabolic processes: Role of reactive oxygen species. Biomolecules. 2019;9:258. doi: 10.3390/biom9070258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi M., Kikuchi D., Okamura H. Imaging of ultraweak spontaneous photon emission from human body displaying diurnal rhythm. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrônio M.S., Ximenes V.F. Light emission from tryptophan oxidation by hypobromous acid. Luminescence. 2013;28:853–859. doi: 10.1002/bio.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowak M., Tryniszewski W., Sarniak A., Wlodarczyk A., Nowak P.J., Nowak D. Light emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system: Possible application for the determination of antioxidant activity of plant phenolics. Molecules. 2018;23:866. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowak M., Tryniszewski W., Sarniak A., Wlodarczyk A., Nowak P.J., Nowak D. Concentration dependence of anti- and pro-oxidant activity of polyphenols as evaluated with a light-emitting Fe2+ -EGTA-H2O2 system. Molecules. 2022;27:3453. doi: 10.3390/molecules27113453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowak M., Tryniszewski W., Sarniak A., Wlodarczyk A., Nowak P.J., Nowak D. Effect of physiological concentrations of vitamin C on the inhibitation of hydroxyl radical induced light emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 and Fe3+-EGTA-H2O2 systems In vitro. Molecules. 2021;26:1993. doi: 10.3390/molecules26071993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyamoto S., Martinez G.R., Medeiros M.H., Di Mascio P. Singlet molecular oxygen generated by biological hydroperoxides. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2014;139:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salgado P., Melin V., Contreras D., Moreno Y., Mansilla H.D.J. Fenton reaction driven by iron ligands. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2013;58:2096–2101. doi: 10.4067/S0717-97072013000400043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu S., Guo R., Gao Y., Chen F. Oxoiron(IV)-dominated heterogeneous Fenton-like mechanism of Fe-Doped-MoS2. Chem. Asian J. 2023;18:e202201134. doi: 10.1002/asia.202201134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh A., Kukreti R., Saso L., Kukreti S. Oxidative stress: A key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules. 2019;24:1583. doi: 10.3390/molecules24081583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergwitz C., Jüppner H. Phosphate sensing. Adv. Chronic. Kidney Dis. 2011;18:132–144. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almeida E.A., Miyamoto S., Martinez G.R., Medeiros M.H.G., Di Mascio P. Direct evidence of singlet molecular oxygen [O2(1Δg)] production in the reaction of acetonitrile with hydrogen peroxide in alkaline solutions. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2002;482:99–104. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(03)00170-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piper L.G., Krech R.H., Taylor R.L. Generation of N3 in the thermal decomposition of NaN3. J. Chem. Phys. 1979;71:2099–2104. doi: 10.1063/1.438581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan S., Cao B., Yuan D., Jiao T., Zhang Q., Tang S. Complexes of cupric ion and tartaric acid enhanced calcium peroxide Fenton-like reaction for metronidazole degradation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024;35:109185. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furcas F., Lothenbach B., Isgor O., Mundra S., Zhang Z., Angst U. Solubility and speciation of iron in cementitious systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021;151:106620. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stefánsson A. Iron(iii) hydrolysis and solubility at 25 °C. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:6117–6123. doi: 10.1021/es070174h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Putnam R.W. Intracellular pH regulation. In: Sperelakis N., editor. Cell Physiology Sourcebook, 3rd. Volume 12. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 2001. pp. 357–372. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ježek P. Pitfalls of mitochondrial redox signaling research. Antioxidants. 2023;12:1696. doi: 10.3390/antiox12091696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cadenas E., Davies K.J. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;29:222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harada Y., Suzuki K., Hashimoto M., Tsukagoshi K., Kimoto H. Chemiluminescence from singlet oxygen that was detected at two wavelengths and effects of biomolecules on it. Talanta. 2009;77:1223–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forman H.J., Bernardo A., Davies K.J. What is the concentration of hydrogen peroxide in blood and plasma? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016;603:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dziuba N., Hardy J., Lindahl P.A. Low-molecular-mass iron complexes in blood plasma of iron-deficient pigs do not originate directly from nutrient iron. Metallomics. 2019;11:1900–1911. doi: 10.1039/C9MT00152B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang B.K., Sikes H.D. Quantifying intracellular hydrogen peroxide perturbations in terms of concentration. Redox Biol. 2014;2:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinert A., Morawski M., Seeger J., Arendt T., Reinert T. Iron concentrations in neurons and glial cells with estimates on ferritin concentrations. BMC Neurosci. 2019;20:25. doi: 10.1186/s12868-019-0507-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noble R.W., Gibson Q.H. The reaction of ferrous horseradish peroxidase with hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:2409–2413. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Z., Chen H., Zhou Y., Ogawa N., Lin J.M. Self-catalytic degradation of ortho-chlorophenol with Fenton’s reagent studied by chemiluminescence. J. Environ. Sci. 2012;24:550–557. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivanova I.P., Trofimova S.V., Piskarev I.M., Aristova N.A., Burhina O.E., Soshnikova O.O. Mechanism of chemiluminescence in Fenton reaction. J. Biophys. Chem. 2012;3:88–100. doi: 10.4236/jbpc.2012.31011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutteridge J.M., Maidt L., Poyer L. Superoxide dismutase and Fenton chemistry. Reaction of ferric-EDTA complex and ferric-bipyridyl complex with hydrogen peroxide without the apparent formation of iron(II) Biochem. J. 1990;269:169–174. doi: 10.1042/bj2690169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirk T.K., Nakatsubo F., Reid I.D. Further study discounts role for singlet oxygen in fungal degradation of lignin model compounds. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983;111:200–204. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(83)80136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.