Abstract

Erythema papulatum centrifugum (EPC), also known as erythema papulosa semicircularis recidivans, is a rare dermatological condition characterized by single or multiple annular or semi-annular centrifugally growing lesions surrounded by tiny erythematous papules typically observed on the trunk. EPC is prevalent, particularly in Japan and China, although only a few cases have been reported outside Asia. Herein, we present the case of a 47-year-old female from Thailand who experienced a pruritic annular erythematous rash on her right arm for two months. The diagnosis of EPC was established based on clinical manifestations and confirmed by histopathological examination. The lesions resolved after one month of treatment with 0.1% betamethasone valerate cream and avoiding warm weather. This case report contributes to the understanding of EPC, which may be underrecognized in clinical practice due to its self-limiting nature and frequent misdiagnosis. Furthermore, this article provides a comprehensive review of 17 previously reported cases of EPC, focusing on their detailed descriptions.

Keywords: annular erythema, annular lesion, eccrine sweat gland, figurate erythema, perieccrine inflammation, sweating

Introduction

Erythema papulatum centrifugum (EPC) is a rare inflammatory skin disorder characterized by the presence of solitary or multiple recurring annular or semi-annular erythematous lesions with central regression surrounded by small red papules.1 The condition is often accompanied by pruritus and can be exacerbated by warm weather or excessive sweating.2 EPC was first reported by Watanabe in 1962, describing a Japanese patient with a skin disorder manifesting eczematous lesions extending centrifugally.3 Subsequently, Watanabe and Nagashima reported the largest EPC case series, including 99 Japanese cases indicating EPC as a unique skin disorder in 1972.4 Later, Song et al documented a similar condition in nine Chinese male patients in 2012 and named it erythema papulosa semicircularis recidivans.5 However, in 2020, Zhang et al suggested that these two terms actually represent the same entity.1 At present, the incidence of EPC has been notably limited, with the majority of reported cases emerging from Japan and China, indicating a potential under-recognition of the condition. EPC is often overlooked due to its limited geographic reports, similarities with other skin conditions, and self-limiting and recurrent nature. In this report, we describe the case of a 49-year-old Thai woman diagnosed with EPC who developed a pruritic, erythematous rash on her right arm that progressively expanded peripherally over time and was successfully treated with topical corticosteroids. Additionally, we provide insights into previously published articles detailing cases of EPC.

Case Presentation

A 47-year-old Thai woman visited the outpatient department with a pruritic erythematous rash on her right arm that featured an annular pattern. The rash persisted for two months and expanded peripherally with central regression. The patient reported that the rash recurred and worsened in response to warm weather or excessive sweating. Prior to seeking medical attention, the patient attempted to alleviate her symptoms with topical calamine lotion, which led to mild improvement. Upon evaluation, her medical history revealed that she had undergone total thyroidectomy 10 years ago due to multiple nodular goiters; however, there were no other notable findings upon systemic examination.

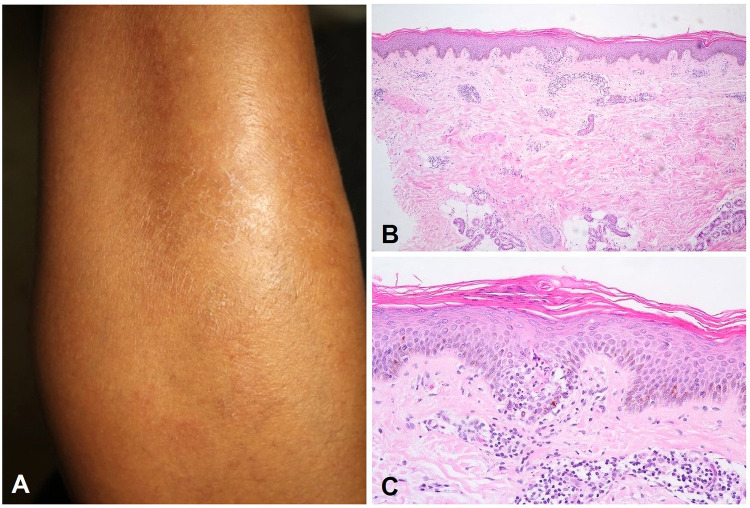

Dermatological examination revealed annular and semi-annular, ill-defined, erythematous patches with multiple tiny peripheral papules on the right arm (Figure 1A). The differential diagnosis encompassed eczema and figurate erythema. Nevertheless, the patient’s presentation did not align with either of these conditions. To gather further information, a skin biopsy was conducted, which revealed superficial and deep perivascular and periductal inflammatory cell infiltrates of lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1B) as well as focal epidermal spongiosis with neutrophils and necrotic cells in the acrosyringium (Figure 1C). Based on the patient’s history, clinical presentation, and histological examination, an EPC diagnosis was definitively established. The patient’s symptoms significantly improved, revealing that the skin lesion had entirely resolved after one month of treatment with 0.1% betamethasone valerate cream applied twice daily and avoiding warm conditions. No recurrence was observed during the three-month follow-up.

Figure 1.

Clinical manifestation: (A) annular and semi-annular, ill-defined, erythematous patches with multiple tiny peripheral papules on the right arm; histopathological findings (hematoxylin-eosin): (B) superficial and deep perivascular and periductal inflammatory cell infiltrates of lymphocytes in the dermis (original magnification x100), (C) focal epidermal spongiosis with neutrophils and necrotic cells in the acrosyringium (original magnification x400).

Discussion

EPC is considered a rare chronic dermatological condition. Its prevalence may be underestimated owing to its benign and self-limiting nature, often resulting in misdiagnosis as eczema or erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC).2 Although EPC is prevalent in the Asian population, it has received minimal attention globally.1,2 To date, only a few cases have been reported outside Asia, including Spain, Turkey, and North America.6–8 Since its initial description, to our knowledge, approximately 160 cases have been reported in the literature, with 17 cases providing detailed information (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previously Reported Cases of Erythema Papulatum Centrifugum with in-Depth Information

| Authors, year | No. | History and clinical presentations | Area of involvement | Aggravating factors/ association | Histology | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ueda et al, 20139 | 1 | 5-year history of recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Back | Sauna bath | Infiltration of lymphocytes around the vessels and ductal segments of the eccrine sweat apparatus in the dermis | Sauna bathing discontinuation | Resolve |

| 2 | 3-month history of pruritic eruptions | Neck, trunk, and extremities | Sweating | Infiltration of lymphocytes around the vessels and ductal segments of the eccrine sweat apparatus in the dermis | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids, topical aluminum chloride | Resolve | |

| Ohmori et al, 20132 | 3 | Multiple, itchy annular lesions | Left forearm, antecubital fossa, and bilateral flanks | NR | NR | Diflucortolone valerate ointment | Resolve with no recurrence |

| 4 | An itchy, annular lesion with red fine papules and papulovesicles in groups on the margin with central clearing | Neck | NR | NR | Diflucortolone valerate ointment | Resolve within 3 weeks | |

| 5 | Multiple annular lesions with groped, red, fine papules margin | Extremities and abdomen | NR | Superficial perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate and mononuclear cell infiltrate around the epidermal and dermal eccrine ducts | Diflorasone acetate ointment | Resolve within 2 weeks | |

| 6 | Expanding itchy eruptions with central healing | Thighs and lower abdomen | NR | NR | Topical potent corticosteroids | Poor response, spontaneous healing | |

| 7 | Itchy eruptions with annular margins composed of fine papules with central healing | Left thigh to lower abdomen | NR | NR | Topical betamethasone dipropionate ointment | Moderate response | |

| Wang et al, 201510 | 8 | Annular, erythematous rash around melanoma, spread centrifugally with multiple interrupted small papules and crusts at the margins | Back | Melanoma | Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and perieccrine inflammation with lym- phocytes, plasma cells and mast cells | Topical corticosteroids | Recalcitrant to topical corticosteroids, lesion disappeared after melanoma excision, no recurrence |

| Zhang et al, 20201 | 9 | 6-year history of recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Abdomen | Autumn season | Focal basal cell oedema with superficial dermal sparse perivascular lymphocytic infiltration | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Resolve with recurrence |

| 10 | Recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Trunk | Autumn and fall season | Superficial perivascular dermatitis without inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Resolve with recurrence | |

| 11 | Recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Trunk | Winter season | Superficial perivascular dermatitis without inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Resolve with recurrence | |

| 12 | Recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Trunk, neck | Spring season | Superficial perivascular dermatitis without inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Resolve with recurrence | |

| 13 | Recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Trunk | Spring season | Superficial perivascular dermatitis without inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Resolve with recurrence | |

| 14 | Recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Trunk | Summer season | Superficial perivascular dermatitis without inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Resolve with recurrence | |

| 15 | Recurrent annular erythematous lesions with itching | Trunk | Summer and winter season | Superficial perivascular dermatitis without inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis | Oral antihistamines, topical corticosteroids | Resolve with recurrence | |

| Oba et al, 20228 | 16 | Semi-annular lesion with peripheral erythema and papules, central hyperpigmentation and expand centrifugally | Trunk | NR | Perivascular lymphocytic infiltration | None | Resolve with recurrence |

| 17 | Erythematous thin plaques with peripheral papules that gradually expanded leaving a lichenified hyperpigmented central region | Trunk, pubic region | NR | Minimal spongiosis and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration in the upper and mid reticular dermis | Topical corticosteroids | No response |

Abbreviation: NR, no report.

EPC is primarily observed in middle-aged males and predominantly affects the trunk.2,9 The clinical characteristics of EPC include pruritic solitary or multiple recurrent expanding annular or semi-annular erythematous lesions with central regression surrounded by tiny erythematous papules. The condition begins with clustered papules or papulovesicles that eventually form a confined erythematous plaque. The lesion then expands centrifugally in an annular pattern with central clearance. If left untreated, it may grow to over 50 cm in diameter. Relapse may occur yearly, and the condition may resolve spontaneously without leaving any trace.1 Histologically, the condition presents with superficial perivascular inflammation with or without mild inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis.11 Minimal epidermal changes such as parakeratosis and spongiosis were also observed. Laboratory findings are typically normal in EPC cases.2,9

The diagnosis of EPC is challenging due to its variable clinical presentation. In 2013, Ueda et al proposed diagnostic criteria for EPC, including (1) the onset of symptoms primarily in older men, (2) increased symptoms during the period from spring to summer, (3) distribution of skin lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities, (4) characteristic clinical appearance of annular erythema and peripheral papules, accompanied by intense itching and outward expansion, (5) exacerbation of symptoms due to external irritation, sweating, warming, and alcohol consumption, and (6) recurrent episodes of symptoms in the same regions.9 In 2019, Zhang et al presented updated EPC criteria, considering the diagnosis of EPC based on a combination of clinical manifestation and histological findings.1 The new criteria include: (1) single or multiple recurrent expanding annular or semi-annular erythema with central regression, surrounded by tiny red papules; (2) lesions relapse yearly and resolve spontaneously without any trace; (3) histopathologic features show superficial perivascular inflammation with or without mild inflammation around sweat glands in the middle dermis; and (4) the absence of other associated cutaneous or internal abnormalities.

The differential diagnosis of EPC includes conditions with annular erythema such as EAC, erythema chronicum migrans (ECM), tinea corporis, and necrolytic migratory erythema (NME). The primary disorder that must be differentiated from EPC is EAC, a disease characterized by an annular erythematous lesion with a fine scale inside the advancing edge known as trailing scales. In contrast, EPC displays an annular erythema composed of grouped tiny papules. Both EPC and EAC are commonly misdiagnosed as eczema,8 emphasizing the importance of considering EPC in the differential diagnosis of annular pruritic lesions, particularly on the trunk of middle-aged male patients. EAC manifests similar histopathological traits but exhibits distinct clinical features from EPC, which presents as grouped papules/vesiculopapules arranged within annular borders, displaying recurrent episodes in comparison to EAC.8–12 Furthermore, inflammation around the intraepidermal and dermal eccrine ducts has been reported only in EPC.2,11 Although EPC has been well documented in the literature as a distinct dermatological disorder, some authors prefer to classify it as a peculiar variant of EAC due to its limited clinicopathological distinction.13 To distinguish from ECM, EPC lacks systemic symptoms and is not associated with a history of tick exposure. Tinea corporis can present with annular erythematous plaques similar to EPC; however, a potassium hydroxide examination can help differentiate it by identifying fungal elements. EPC reveals an absence of the blistering and erosive characteristics of NME and is not linked to glucagonoma syndrome.

The exact etiology of EPC remains unknown; however, it has been hypothesized to be a sweating-related dermatosis owing to its histological features.2 Speculation suggests a potential link between EPC and sweating,2,5,9 with some patients experiencing exacerbation following sweating or spicy food ingestion.5 Topical antiperspirants may offer relief and reduce relapse rates.9,14 While most cases of EPC occur without systemic diseases,1,2 associations with bacterial allergy, primary pancreatic B-cell lymphoma, and melanoma have been reported.10,15–18 Notably, EPC has been considered a warning sign of melanoma, with one reported case in 2015 where EPC developed around a melanoma lesion before disappearing post-malignancy removal with no recurrence.10 Therapeutic options for EPC typically involve oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids, leading to resolution within 1–4 weeks, although recurrence remains a challenge to manage effectively.1 The limitations of this case report included the absence of dermoscopic details and a limited duration of follow-up for the patient.

Conclusion

This case report highlights the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of EPC in a 47-year-old Thai woman. EPC, although relatively uncommon, presents as an annular erythematous rash that is often exacerbated by warm weather or sweating. The diagnosis of EPC is established through the analysis of clinical manifestations, which is then confirmed and validated by histological examination. Our patient’s history and clinical findings align with those of previously reported cases, supporting the diagnosis based on characteristic histological features and response to topical corticosteroids. Despite its benign nature, EPC poses diagnostic challenges due to its resemblance to other dermatological conditions, complicating diagnosis. Awareness of its distinctive features is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management, especially in regions such as Asia, where it is prevalent. Further research is needed to understand the underlying pathogenesis of EPC and to improve its diagnostic criteria and therapeutic strategies. Raising awareness of EPC will lead to better diagnostic accuracy and timely care for affected patients.

Funding Statement

No sources of funding were used to prepare this manuscript.

Abbreviations

EPC, Erythema papulatum centrifugum; EAC, Erythema annulare centrifugum; ECM, Erythema chronicum migrans; NME, Necrolytic migratory erythema; NR, No report.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article was performed in accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval was not required to publish the case details in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images as per our standard institutional rules.

Disclosure

The authors declare that this manuscript was prepared in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zhang LW, Wang WJ, Jiang CH, et al. Erythema papulatum centrifugum and new diagnostic criteria. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(1):e87–e90. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohmori R, Kikuchi K, Yamasaki K, Aiba S. A new type of annular erythema with perieccrine inflammation: erythema papulatum centrifugum. Dermatology. 2013;226(4):298–301. doi: 10.1159/000348708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe Y. The centrifugally-expanding eczematous lesion. Jpn J Dermatol. 1962;72:573. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanabe Y, Nagashima A. Erythema papulatum centrifugum—small erythema papulatum spreading outward. Rinsho Derma (Tokyo). 1972;14:437–443. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Z, Chen W, Zhong H, Ye Q, Hao F. Erythema papulosa semicircularis recidivans: a new reactive dermatitis? Dermatitis. 2012;23(1):44–47. doi: 10.1097/DER.0b013e31823e2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodríguez-Lomba E, Molina-López I, Baniandrés-Rodríguez O. An Atypical Figurate Erythema With Seasonal Recurrences. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1340–1341. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franco A, Sempler J, Moss R, Zussman J. A Pruritic Annular Eruption: answer. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(5):386. doi: 10.1097/dad.0000000000000789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oba MC, Akin T, Yilmaz F. Erythema papulatum centrifugum: a probably underdiagnosed cause of annular erythema. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(12):7212–7214. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueda C, Makino T, Mizawa M, Shimizu T. Erythema papulatum centrifugum: a sweat-related dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(2):e103–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang HH, Chin SY, Shih YH. Erythema papulatum centrifugum developing around melanoma. J Dermatol. 2015;42(4):432–433. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minami K. The histological findings of erythema papulatum centrifugum. Acta Dermatol Kyoto. 1978;73:103–131. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suchonwanit P, Triyangkulsri K, Ploydaeng M, Leerunyakul K. Assessing Biophysical and Physiological Profiles of Scalp Seborrheic Dermatitis in the Thai Population. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5128376. doi: 10.1155/2019/5128376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernia E, Requena C, Llombart B. Erythema Papulosa Semicircularis Recidivans: a New Entity or a Subtype of Erythema Annulare Centrifugum? Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111(9):788–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rattanakaemakorn P, Suchonwanit P. Scalp Pruritus: review of the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1268430. doi: 10.1155/2019/1268430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue A, Sawada Y, Ohmori S, et al. Erythema papulosa semicircularis recidivans associated with primary pancreas B cell lymphoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26(3):306–307. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2016.2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suchonwanit P, Leerunyakul K, Kositkuljorn C. Diagnostic and prognostic values of cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13650. doi: 10.1111/dth.13650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ofuji S, Minami K. Erythema papulatum centrifugum. Rinsho Derma. 1972;14:443–444. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masuzawa M. Erythema papulatum centrifugum. Pract Dermatol. 1999;21:905–908. [Google Scholar]