Abstract

Biologics are playing an increasingly important role in health care globally but are placing a substantial burden on payers. The development of biosimilars—drugs that are highly similar to and have no clinically meaningful differences from originator biologics—is critical to improving the affordability and accessibility of these medications. Medicines regulators, however, have had varied success with biosimilars to date. We examined agency guidance documents, peer-reviewed articles, and gray literature related to biosimilars in Australia, Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States to evaluate variations in the approaches to biosimilar approval taken by their respective medicines regulators. We found that the medicines regulators take similar approaches to biosimilar approvals, but that differences in their policies and their jurisdiction’s laws regarding testing requirements, indication extrapolation, exclusivities, and substitution may contribute to the varied successes of biosimilars observed. Policies supportive of product-specific guidance, extrapolation, shorter exclusivity periods, and substitution were correlated with greater success in biosimilar approval and uptake. As medicines regulators work to promote biosimilars, understanding the impact of these laws and policies is crucial. Reforms consistent with these policies can create regulatory environments more supportive of biosimilar approvals, promoting access to affordable biologics for patients globally.

Keywords: biologics, biosimilars, prescription drugs, access to medicines, comparative health policy, FDA regulation

I. INTRODUCTION

Biologic drugs are complex biopharmaceuticals manufactured from living organisms or derived from their cells and tissues.1 They are playing an increasingly important role in medical treatments, revolutionizing care for patients with various cancers, autoimmune conditions, and genetic disorders. At the same time, biologics are taking up a larger share of health care spending.2 Although biologics—such as high-profile blockbuster medications including Humira (adalimumab), Enbrel (etanercept), and Remicade (infliximab)3—comprised only 0.4% of drugs prescribed in the United States (US) in 2018 and only 2% of prescription drug claims in Canada in 2021, they represented 46% of net drug spending and 29% of public drug spending in those countries in those years, respectively.4 Biologics also account for a similarly high percent of prescription drug spending in Australia, the European Union (EU), and the United Kingdom (UK).5 This disproportionate spending is due to the high prices of biologics. For example, the list price for the blockbuster immunotherapy Keytruda (pembrolizumab) in 2021 was ~$175,000 per patient per year in the US.6 By 2022, at least three biologics had US list prices greater than $1 million per patient per year.7

To address the high cost of biologics, governments in several countries have developed specialized pathways for medicines regulators to approve highly similar follow-on biologics that have no clinically meaningful differences from an ‘originator’ (or reference) biologic.8 These ‘biosimilars’ are intended to promote competition, thereby lowering the price of treatment for patients and health systems (Box 1).9

Box 1.

Definitions of Key Terms and Abbreviations

| Key Term or Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Biologic | A drug manufactured from living organisms or derived from its cells or tissues |

| Biosimilar | A product that is highly similar to and has no clinically meaningful differences from an originator biologic |

| Biosimilar Testing Requirements | Non-clinical and clinical studies required by medicines regulators for the approval of a biosimilar product |

| Data Exclusivity | The period where manufacturers hold exclusive rights to the information obtained in developing their biologic |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency, the European Union’s medicines regulator |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration, the United States’ medicines regulator |

| Health Canada | Canada’s medicines regulator |

| Indication extrapolation | Approving a biosimilar for multiple indications of the originator biologic based on the similarity between the biosimilar and the originator biologic without studies of all indications |

| Market Exclusivity | A period which an originator biologic is protected from direct competition, including biosimilar competition |

| MHRA | Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, the United Kingdom’s medicines regulator |

| Substitution | Dispensing a biosimilar in place of the originator biologic |

| TGA | Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australia’s medicines regulator |

To date, the number of biosimilars that have been approved by medicines regulators has varied widely (Table 1). As of May 31, 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved 53 biosimilars,10 the European Medicines Agency (EMA) 101,11 UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) 93,12 Health Canada 58,13 and Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) 55.14 Although EMA has been approving biosimilars longer than the other regulators—since 2006—only in the last 5 years have other regulators had similar approval rates (Table 2).

Table 1.

Medicines Regulators and Biosimilar Markets

| Jurisdiction | Regulator | Number of Approved Biosimilars as of May 31, 2024 | Year First Biosimilar Approved |

Biologic Share of Prescription Drug Market in 2020

(By Sales) |

Biosimilar Share of Biologic Market

(By Volume) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Therapeutic Goods Administration | 55 | 2010 | 33% | 24% (2020) |

| Canada | Health Canada | 58 | 2009 | 34% | 23% (2019) |

| European Union | European Medicines Agency | 101 | 2006 | 32% | 35–38% (2020) |

| United Kingdom* | Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency | 93 | 2006 | 25% | 86–90% (2020) |

| United States** | Food and Drug Administration | 53 | 2015 | 36% | 20% (2020) |

NOTES:

*Prior to Brexit, medicines in the UK were approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Regulation shifted solely to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) as of January 1, 2021. The number of approved biosimilars in the UK includes all biosimilars approved by EMA pre-Brexit (including those ultimately withdrawn) and all biosimilars approved by MHRA post-Brexit.

**Prior to March 23, 2020, insulins could not be approved by FDA under its biosimilar pathway. Because of this, certain insulin products that are approved as biosimilars by other medicines regulators were FDA approved under a different pathway and are not regulated as biosimilars. These products are not included in the number of approved biosimilars in the US.

Table 2.

Biosimilars Approved by Medicines Regulator by Year

| Year | Australia | Canada | European Union | United Kingdom | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2 | ||||

| 2007 | 5 | ||||

| 2008 | 4 (3 unique*) | ||||

| 2009 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 2010 | 2 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 2011 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2013 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ||

| 2014 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 2015 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2016 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |

| 2017 | 3 | 3 | 16 (12 unique) | 5 | |

| 2018 | 6 | 7 | 16 (15 unique) | 7 | |

| 2019 | 8 | 1 | 5 (4 unique) | 10 | |

| 2020 | 6 | 17 | 10 | 3 | |

| 2021 | 6 | 9 | 10 (9 unique) | 6 | 4 |

| 2022 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

| 2023 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| By May 31, 2024 | 5 | 2 | 6 (5 unique) | 3 | 8 |

Notes:

*Non-unique biosimilars refers to when one manufacturer submits multiple applications and receives multiple approvals from European Medicines Agency for the same biosimilar product but under different brand names. Years prior to the first biosimilar approval in a jurisdiction are shaded. Only biosimilars approved by Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency after Brexit are included in the yearly approvals of the UK. The non-unique products are as follows: Ratiopharm GmbH’s two filgrastim biosimilars (2008); Amgen Europe B.V.’s two adalimumab biosimilars (2017); Sandoz GmbH’s two rituximab biosimilars (2017); Celltrion Healthcare Hungary Kft.’s three rituximab biosimilars (2017); Sandoz GmbH’s two adalimumab biosimilars (2018); Fresenius Kabi Deutschland GmbH’s two adalimumab biosimilars (2019); Stada Arzneimittel AG’s two adalimumab biosimilars (2021); and Sandoz GmbH’s two denosumab biosimilars (by May 31, 2024).

Biosimilars have also offered a wide range of savings and experienced highly variable uptake (the biosimilar share of the biologics market for which biosimilars are available). Biosimilar market penetration is highly product-specific, but generally higher in the EU and the UK than in Australia, Canada, and the US.15 In the EU, biosimilar uptake four years after launch was on average 35–38% between 2014 and 2020.16 In 2020, biosimilars saved the EU health care system ~€5.7 billion ($6.4 billion USD) off list prices.17 That same year in the UK, biosimilar uptake was 86–90% and provided ~$800 million USD per year in savings to the National Health Service.18 By contrast, biosimilar uptake was 24% in Australia in 2020 and 23% in Canada in 2019.19 In the US, biosimilar uptake was 20% in 2020 and provided on average 30% in savings relative to the list prices of originator biologics, an estimated $7.9 billion USD.20

Several regional and national factors contribute to these different experiences with biosimilar approvals. Market dynamics and patent exclusivities can encourage or discourage manufacturers from developing biosimilars.21 Reimbursement policies of public and private payers can incentivize or disincentivize prescribing by physicians.22 Rebate policies of pharmacy benefit managers can direct payers and patients towards or away from biosimilars.23 Pharmacy laws related to biosimilar substitution at the point of sale can further promote or prevent patient use of biosimilars.24 Finally, the governing laws and policies of medicines regulators play an important role in biosimilar approval, use, and savings.25 As medicines regulators take steps to harmonize global biosimilars regulations to increase the efficiency of biosimilar approval and promote access to biosimilars,26 it is essential to understand the role of the current regulatory environments in supporting or hampering biosimilar approvals.

We accordingly evaluated the biosimilar policies of EMA, FDA, Health Canada, MHRA, and TGA, both as a matter of governing law and regulatory practice. We reviewed guidance documents published by the medicines regulators and both peer-reviewed and gray literature related to biosimilar approvals in Australia, Canada, the EU, the UK, and the US. Through our review, we identified four aspects of biosimilar regulation and approval common among the regulators that may have contributed to the variations in their experiences with biosimilars: (i) biosimilar testing requirements, (ii) indication extrapolation, (iii) exclusivities, and (iv) biosimilar substitution (Table 3). In this Article, we discuss each aspect in turn, highlighting the differences among the regulators and reviewing how these differences in law and policy may contribute to variations in biosimilar approvals and utilization. In doing so, we identify the laws and policies that are correlated with more success with biosimilars and recommend reforms that would support biosimilar approval and utilization.

Table 3.

Comparing The Biosimilar Approval Policies of Five National Medicines Regulators

| Regulator | Biosimilar Testing Requirements | Indication Extrapolation | Exclusivities | Substitution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Medicines Agency | + Product-Specific Guidance Documents • Animal studies not required in some circumstances • Comparative clinical efficacy trials not required in some circumstances |

• Additional Scientific Justification Required in Application | • Medium Exclusivity Period (8 years data exclusivity; 10 years market exclusivity) | • No Direct Role in Substitution + Issued Guidance Document Supportive of Substitution |

| US Food and Drug Administration | – Primarily General Guidance Documents – Delays in Disseminating Guidance • Animal studies not required in some circumstances • Comparative clinical efficacy trials not required in some circumstances |

• Additional Scientific Justification Required in Application | – Long Exclusivity Period (4 years data exclusivity; 12 years market exclusivity; exclusivity for first interchangeable biosimilar) | • No Direct Role in Substitution – Interchangeability Designation Sets Higher Standard for Approval, Creating a Barrier for Substitution |

| Health Canada | – General Guidance Document • Animal studies not required in some circumstances • Comparative clinical efficacy trials not required in some circumstances |

• Additional Scientific Justification Required in Application - More Conservative in Applying Extrapolation Policy |

• Medium Exclusivity Period (6 years data exclusivity; 8 years market exclusivity) | • No Direct Role in Substitution |

| UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency | + Product-Specific Guidance Documents • Animal studies not required • Comparative clinical efficacy trials not required in some circumstances |

+ No Additional Scientific Justification Required in Application | • Medium Exclusivity Period (8 years data exclusivity; 10 years market exclusivity) | • No Direct Role in Substitution + Issued Guidance Document Supportive of Substitution |

| Therapeutic Goods Administration | + Product-Specific Guidance Documents • Animal studies not required in some circumstances • Comparative clinical efficacy trials not required in some circumstances |

• Additional Scientific Justification Required in Application | + Shortest Exclusivity Period (5 years data exclusivity; no market exclusivity) | • No Direct Role in Substitution |

Key: + Policy supportive of biosimilar approval and/or utilization;

• Policy neutral regarding support of biosimilar approval and/or utilization;

– Policy not supportive of biosimilar approval and/or utilization

II. BIOSIMILAR TESTING REQUIREMENTS

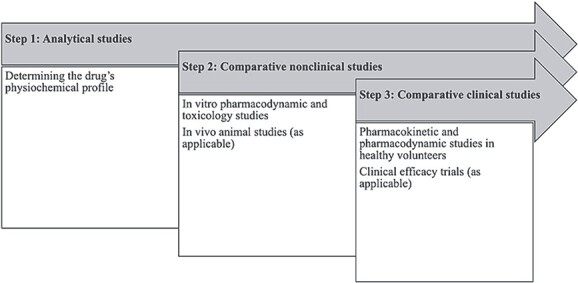

Biosimilar development in all five jurisdictions can be described in a stepwise approach (Fig. 1).27 First, the physicochemical profile of the biosimilar is assessed.28 The biosimilar must have the same amino acid sequence as the originator biologic, and the structure and folding of the biosimilar (the 3D secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of the protein) must be comparable.29 Any variations in these higher-level structures must be evaluated to consider if and how they may impact the biosimilar’s function and stability.30 Depending on the complexity of the biologic molecule, confirming these higher level structures may be more or less difficult. For example, monoclonal antibodies are much larger and more complex compared to an insulin molecule (weighing ~17 times more) and developing their respective biosimilars are in turn more complex.31

Figure 1.

Stepwise Approach to Biosimilar Testing for Regulatory Approval. Source: Authors’ compilation and synthesis of information from journal articles on biosimilar approvals and guidance provided by the EMA, FDA, Health Canada, MHRA, and TGA.

Second, comparative nonclinical studies are conducted, typically in vitro pharmacodynamic and toxicology studies and in some cases in vivo animal studies, to demonstrate the safety of the biosimilar.32 In this step, guidance differs among the regulators as to when animal studies may be needed. EMA guidance, for example, prioritizes in vitro nonclinical assessments compared to in vivo toxicology studies, consistent with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.33 In vivo animal studies are usually not required by EMA, with the regulator asserting in guidance that in vitro assays may be more specific and sensitive in identifying differences between the originator and biosimilar.34 FDA guidance, in turn, sets forth the circumstances when animal toxicity, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic studies are valuable35 and more generally advises sponsors that its review of comparative analytical data informs the extent and scope of animal studies necessary for biosimilar approval.36 Health Canada guidance similarly states that animal studies may not be necessary if ‘the comparative structural, functional and non-clinical in vitro studies are considered satisfactory and no issues are identified that would preclude administration into humans.’37 MHRA guidance goes further, explicitly not requesting in vivo animal studies to support comparability between a biosimilar and a reference product, stating they are not relevant.38

Third, comparative clinical studies are conducted, including pharmacokinetic studies, pharmacodynamic studies, and, if deemed necessary, comparative clinical efficacy trials.39 Common types of studies that may be conducted by biosimilar applicants or required by regulators are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Types of Studies Conducted for Biosimilar Approval

| Key Term or Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Comparative efficacy studies | Clinical studies that compare the efficacy of the originator biologic and biosimilar, typically using randomized controlled trials |

| Comparative immunogenicity testing | Clinical studies that compare the immune response generated to both the biosimilar and the reference product in a sensitive study population |

| In vitro toxicology studies | Studies of potential toxic properties or off-target effects, in cells or tissues in a controlled laboratory setting |

| In vivo toxicology studies | Studies of potential toxic properties or off-target effects, in a relevant animal species |

| Pharmacodynamic clinical studies | Clinical studies determining the effects of a drug on the body |

| Pharmacokinetic clinical studies | Clinical studies determining concentration of a drug in the body |

| Switching studies | Studies where population currently taking originator biologic switches to the biosimilar, to determine pre- and post-safety effects |

The medicines regulators vary on the circumstances and application of when comparative clinical efficacy trials are needed. MHRA advises they may not be necessary if a ‘sound scientific rationale supports this approach,’ though comparative efficacy or safety trials are likely necessary when ‘there is a lack of understanding of the biological functions of the [reference product] related to its clinical effects or where the relevant [critical quality attributes] may not be sufficiently characterised due to analytical limitations.’40 EMA, FDA, Health Canada, and TGA similarly require comparative clinical efficacy trials when there is remaining uncertainty about clinical meaningful differences between the biosimilar and originator products.41

In line with this guidance, some regulators have not required comparative clinical efficacy trials in certain circumstances. Although EMA guidance at first strictly required comparative efficacy trials, EMA now may not require comparative efficacy trials for biosimilars applicants that have demonstrated comparability through comparative pharmacodynamic studies.42 For example, EMA approved the biosimilar osteoporosis treatment Sondelbay (teriparatide), without a dedicated clinical efficacy trial, instead relying on a comparative pharmacokinetic study in healthy patients.43 Health Canada also advises that comparative clinical efficacy trials, although required in most cases, may not be necessary when there is a clinically relevant pharmacodynamic endpoint.44 FDA, similarly, will accept data from pharmacodynamic studies instead of comparative clinical efficacy trials if the data adequately supports similarity.45 For example, FDA has approved some biosimilars without comparative clinical efficacy trials, including some epoetin alfa, filgrastim, and pegfilgrastim biosimilars, due to pharmacodynamic biomarkers existing to support similarity.46

Other more complex biosimilars, by contrast, have been approved with comparative clinical efficacy trials. As one example, FDA approved the application for the Humira biosimilar Cyltezo (adalimumab-adbm) based in part on a 48-week randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study comparing the biosimilar and US-licensed Humira in 645 patients with rheumatoid arthritis.47

Throughout this stepwise biosimilar development process, manufacturers periodically meet with medicines regulators and submit the data collected in these studies.48 Regulators will review all the data as part of the approval decision but may also review submissions in these periodic meetings and discuss sponsors’ study plans. These interactions may influence the types of studies conducted by manufacturers.49

In addition to some variations in their biosimilar testing requirements, medicines regulators take different approaches in providing guidance on their approval processes to prospective biosimilar applicants. Health Canada has published a general guidance document on biosimilar approval advising applicants on data and study requirements.50 FDA similarly provides mostly general guidance documents, except for specialized guidance for biosimilar insulins.51 By contrast, EMA provides both general guidance documents on general scientific and clinical studies supporting biosimilar approvals and product-specific guidance documents, including biosimilars for monoclonal antibodies, recombinant granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, low-molecular-weight heparins, interferon beta, and somatropin.52 MHRA has adopted all and TGA has adopted many of EMA’s product-specific guidance documents.53 This robust guidance provided has fostered an environment supportive of manufacturers seeking biosimilar approval and may account for some of the additional approvals by EMA. Less specific guidance documents may in turn contribute to fewer approvals by FDA and Health Canada.54

III. INDICATION EXTRAPOLATION

Many originator biologic products are approved for multiple indications by the time their exclusivity periods are close to ending and biosimilars are poised to enter the market.55 However, medicines regulators may not require biosimilar applicants to conduct studies for each approved indication. Instead, the biosimilars can be approved for these additional indications based on the similarity of the biosimilar to the originator biologic through a principle called extrapolation.56 Various factors impact whether an extrapolation decision can be made, including similarities in the disease states and pharmacologic properties. In making an indication extrapolation decision, medicines regulators are determining that the data provided by the applicant is sufficient to support that the biosimilar is safe for multiple indications, not just the indications studied.57

EMA, FDA, Health Canada, MHRA, and TGA all provide guidance on the evidence required to support indication extrapolation. MHRA allows a biosimilar to claim all indications of the reference product without further justification, absent intellectual property protections, once the biosimilar is shown to be highly similar to the reference product.58 EMA, FDA, Health Canada, and TGA allow indication extrapolation when there is sufficient scientific justification to support extrapolating the clinical data to support approval of the other indications.59 Relevant scientific justification may include evidence on the biosimilar’s mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity. Applicants do not need to prove biosimilarity again, and generally do not need to complete further studies if there is evidence supporting specific aspects of the other indications.60

Although the standards for indication extrapolation are similar across jurisdictions, medicines regulators have on occasion reached different conclusions on the same medicines. For example, EMA approved two infliximab biosimilars for the full range of indications based on indication extrapolation.61 By contrast, Health Canada did not approve the two biosimilars for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, stating that there were functional differences between the biosimilars and originator biologic related to the mechanism of action.62 The agency later approved the two biosimilars for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis based on ‘newly submitted physicochemical and biological data and… rationales addressing the roles of various potential mechanisms of action and their relationships to clinical outcomes.’63 FDA also approved one of these infliximab biosimilars for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis on the basis of indication extrapolation, but only after requesting additional study data related to these indications.64 These differing decisions reflect both differences in the regulators’ data requirements for biosimilar approval and their approaches to indication extrapolation.

Other differences have been observed in the indications for which biosimilars have been approved, particularly arthritis and cancers, but it is unclear whether this is due to indication extrapolation, intellectual property protections, or manufacturer business decisions to delay or not seek approval for certain indications (for example, due to a small potential market).65 Thus, while variations in indication extrapolation cannot be attributed to differences in the regulatory standards or pathways alone, they demonstrate how the regulators may approach their review of the data, resulting in differing approval decisions.

IV. EXCLUSIVITIES

Pursuant to governing laws, all five medicines regulators provide some regulatory exclusivities (a form of intellectual property protection separate from patents) to originator biologics that prevent the approval and marketing of biosimilars for a set period of time.66 Two types of exclusivities exist: data exclusivities and market exclusivities.67 Data exclusivities provide originator biologic manufacturers a period over which they hold exclusive rights to the information obtained in developing their biologic.68 During data exclusivity periods, biosimilar manufacturers cannot rely on data from the originator biologic or the medicines regulator’s approval of the originator biologic.69 Therefore, biosimilar manufacturers cannot submit applications under the abbreviated approval pathway until data exclusivities have expired.70 Market exclusivities provide originator biologics manufacturers time during which they can market their biologic without biosimilar competition.71 During market exclusivity periods, biosimilar companies are prohibited from launching a biosimilar product, but they are not prohibited from relying on originator product data or submitting applications for biosimilar approval to medicines regulators for review.72 Data and market exclusivity periods generally run concurrently, with market exclusivity periods often extending past data exclusivity.73

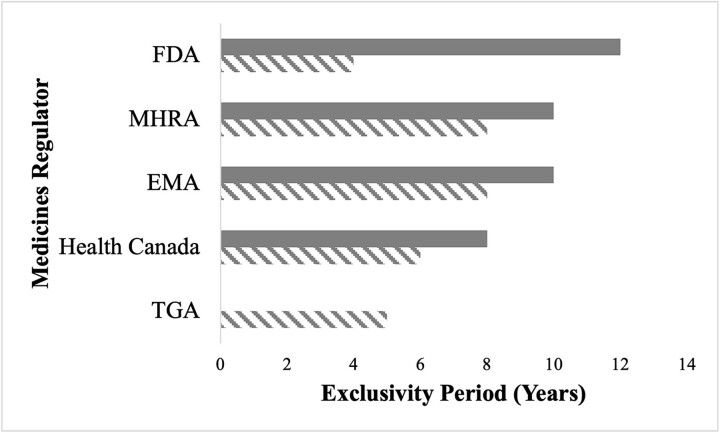

Exclusivity periods granted to originator biologics by medicines regulators at the time of approval vary, resulting in differences when biosimilars may enter each market (Fig. 2).74 In Australia, the originator biologic’s data exclusivity period is 5 years; no market exclusivity period is provided.75 Data exclusivity in Canada is 6 years and market exclusivity is 8 years.76 However, if originator manufacturers conducted pediatric trials in the first 5 years of the market exclusivity, they can receive an additional 6 months of market exclusivity.77 In the EU, biosimilar applications are prohibited by data exclusivity for 8 years, and biosimilar approval is prohibited by market exclusivity for 10 years.78 Originator manufacturers can receive an additional year of market exclusivity for the approval of a new indication with a significant added clinical benefit.79 MHRA similarly provides biologics with 8 years of data exclusivity and 10 years of market exclusivity.80 FDA provides the longest market exclusivity period: 12 years.81 Within that exclusivity period, FDA additionally provides 4 years of data exclusivity during which FDA cannot accept an application for a biosimilar.82 Originator manufacturers may be eligible for an additional 6 months of market exclusivity for conducting pediatric studies.83 However, in many cases in the US, regulatory exclusivities do not exceed patent-protected market exclusivity, limiting the impact of these protections on biosimilar competition.84

Figure 2.

Biologic Data and Market Exclusivity Periods Across Five Jurisdictions, Legend: Solid Gray = Market Exclusivity; Diagonal Gray Lines = Data Exclusivity.

Even so, certain market exclusivities do not limit biosimilar approval altogether but only for specific indications subject to additional protections. In such instances, a biosimilar can be approved with a ‘skinny label’ that omits the protected indications, but only when the originator biologic has additional unprotected indications.85 For example, Inflectra, one of the biosimilars for Remicade, has been approved by FDA for most the originator biologics’ approved indications, but not pediatric ulcerative colitis due to a remaining exclusivity.86 Several Humira biosimilars have been approved for most indications but not hidradenitis suppurativa or uveitis due to existing exclusivities.87 In theory, this may limit access to biosimilars for certain patients; in practice, however, it is unclear whether skinny labels prevent patients from receiving the biosimilar for these carved-out indications.88

Taken as a whole, these varied exclusivities, along with strategies taken by biologics manufacturers to maximize and extend these exclusivities, can also result in varied access to and approval of biosimilars across and within jurisdictions. The Humira biosimilar Amgevita, for instance, was launched in the EU in 2018, Canada in 2021, and the US in 2023.89 This inconsistent availability of biosimilars in part contributes to the differences in biosimilar utilization across jurisdictions.

V. BIOSIMILAR SUBSTITUTION

Whether a patient ultimately receives an originator biologic or a biosimilar may hinge on how the prescription is written. A provider may write the brand name (eg Humira) or the active ingredient (eg adalimumab) when prescribing a drug to a patient. If a provider wants the brand name drug dispensed, they may indicate that directly on the prescription (eg ‘Dispense As Written’ or ‘No Substitution Allowed’). Otherwise, depending on the jurisdictions’ laws, a pharmacist may be permitted to dispense the biosimilar in lieu of the reference product—a practice called pharmacy substitution.90 Substitution laws have been important, particularly in the US, in creating robust generic markets and increasing the utilization of generic drugs,91 and similarly play a significant role in supporting biosimilar utilization.92 The impact may be different in the context of biosimilars, however, as many biosimilars are physician-administered drugs, rendering pharmacy substitution inapplicable.93

Medicines regulators approve biosimilars for sale in national or regional markets based on findings that they are both highly similar to and have no clinically meaningful differences from their corresponding originator biologic.94 Importantly, biosimilars are not approved as identical copies of the originator biologic, as is done with generics for small-molecule brand-name drugs.95 As a result of these differences between generics and biosimilars, medicines regulators play a different role in the ultimate use of biosimilars and their substitution.96

None of the five medicines regulators studied play a direct role in biosimilar substitution, meaning making decisions about when a biosimilar may be dispensed instead of the originator when prescribed. In Australia, decisions regarding substitution are made by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee, an independent body appointed by the government to make decisions regarding medicines reimbursement.97 In Canada, each province makes such determinations, with eleven Canadian provinces and territories having implemented policies mandating switching patients to biosimilars for at least some drugs.98 In the EU, pharmacy-level substitution decisions are left to each member state’s governments.99 Most countries prohibit the automatic substitution of biosimilars by pharmacists, though some countries permit it under specific circumstances, such as for initiator patients, with physician input, or when the biosimilar is produced by the same manufacturer.100 For example, German law permits substitution of biosimilars manufactured by the same manufacturer as the originator biologic.101 French law permits biosimilar substitution for initiator patients.102 The UK (not MHRA), by contrast, passed a law prohibiting automatic biosimilar substitution at the pharmacy level, though the National Health Service encourages physicians to prescribe biosimilars.103 In the US, biosimilar substitution laws are made by each state.104 Most states set additional requirements on biosimilar substitution, including notifying patient and prescriber about the substitution, and maintaining records on dispensing.105

Regulatory approval of the biosimilar product is required in all jurisdictions for substitution to be allowed. However, unlike the other agencies, specific aspects of FDA’s approval decisions directly impact whether biosimilar substitution will be permitted under state law. Under most state laws, in addition to being approved, a biosimilar must have been granted an interchangeability designation by FDA to be automatically substitutable by pharmacists at the point of dispensing.106 Under FDA law, interchangeable means ‘the biological product may be substituted for the reference product without the intervention of the health care provider who prescribed the reference product.’107 To grant the interchangeability designation, FDA must determine that the product is (i) biosimilar to the reference product, (ii) expected to provide the same clinical effect as the reference product in any given patient, and (iii) that ‘the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biological product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product without such alternation or switch.’108 Biosimilar manufacturers must provide evidence demonstrating each of these requirements, which may be beyond the data necessary to show biosimilarity, and can include studies evaluating the effects of switching back and forth between the originator biologic and the biosimilar (‘switching studies’).109 In some cases, FDA required no additional studies were required and granted biosimilars with the interchangeability designation based only on the sponsor’s scientific justifications.110 FDA guidance published in June 2024 allows sponsors to provide an ‘assessment of why the comparative analytical and clinical data’ already provided in the application support a finding of interchangeability.111 Notably, while FDA does not directly make decisions regarding pharmacy substitution, the interchangeability designation gives FDA a greater influence on which biosimilars are ultimately permitted to be substituted.112

Although no other regulators studied have similar influence on substitution decisions, some regulators have made statements reflecting their views switching between reference products and biosimilars. In 2022, EMA and MHRA released separate guidance regarding the ‘interchangeability’ of biosimilars,113 using the term scientifically to refer to whether a biologic and biosimilar can be exchanged with the same expected clinical effect.114 MHRA advised that references biologics and biosimilars, as well as different biosimilars for the same reference product, are considered to be interchangeable.115 While MHRA’s statement does not change the current substitution laws, and reiterated that pharmacy-level substitution is prohibited and that substitution decisions should be made between patient and provider,116 it shows the growing support of regulators regarding the likelihood that biosimilars and originator biologic drugs will achieve the same clinical effect in broad patient populations.

EMA’s statement was even more supportive of interchangeability and the potential for substitution. The agency’s guidance stated that ‘once a biosimilar is approved in the EU it is interchangeable, which means the biosimilar can be used instead of its reference product (or vice versa) or one biosimilar can be replaced with another biosimilar of the same reference product.’117 While EMA noted it does not have authority over switching or substitution decisions,118 its statement also shows a growing confidence in biosimilars and a growing support by regulators of biosimilar substitution.

Substitution has been important for generic drugs gaining significant market shares,119 and FDA’s interchangeability designation has been suggested to be a barrier to greater biosimilar entry and competition.120 Historically, FDA’s interchangeability designation was also considered a contributor to the lag in biosimilar approvals and utilization in the US compared to other countries.121 Furthermore, with few adverse events related to biosimilars (compared to originator biologics) in the US and abroad and little evidence of safety issues from switching, FDA’s interchangeability designation may be unnecessary to protect patients and constitute an inefficient use of FDA resources.122 This is further supported by an FDA systematic review of clinical studies and peer-reviewed literature finding ‘no difference in the safety profiles or immunogenicity rates in patients who were switched and those who remained on a reference biologic or a biosimilar.’123

VI. DISCUSSION: IMPLICATIONS OF VARIATIONS IN BIOSIMILAR APPROVAL PATHWAYS

The four aspects of biosimilar regulation reviewed in this Article—biosimilar testing requirements, indication extrapolation, exclusivities, and biosimilar substitution—all have notable implications for the approval and utilization of biosimilars. Testing requirements set forth what is necessary for a manufacturer to gain approval for a biosimilar product, and differences among jurisdictions in these requirements create differing obligations and barriers for approval.124 Indication extrapolation requirements affect the types and number of studies a biosimilar manufacturer must conduct to receive approval for their product, and variations in these policies can lead to the same biosimilar being approved for different indications in different jurisdictions.125 Exclusivity periods are a core barrier to biosimilar entry, and we have already seen how exclusivities have contributed to differing biosimilar access globally,126 particularly in the case of Humira.127 Substitution laws and policies can impact whether a patient ultimately receives an originator biologic or a biosimilar, influencing the incentives of biosimilar manufacturers and the effect of biosimilars on high drug prices.128 While most medicines regulators do not play a role in substitution policies, some regulators’ decisions may influence the ability of a biosimilar to be dispensed to a patient.129 In sum, these four factors represent key barriers facing biosimilars in the five jurisdictions studied throughout their product lifecycle.

Notable variations exist among the roles of EMA, FDA, Health Canada, MHRA, and TGA in biosimilar approvals that may promote or discourage biosimilar entry and competition. Guidance for biosimilar manufacturers published by EMA (and largely adopted by MHRA and TGA) include both general and product-specific recommendations, potentially clarifying and easing the application process. Testing requirements for biosimilar approval are largely similar among the regulators,130 yet the additional requirements for FDA approval of interchangeability (which may be necessary for gaining a substantial market share) may delay or deter entry.131 Indication extrapolation policies are also similar among regulators,132 though Health Canada in practice is the most conservative and MHRA’s standard is the least burdensome.133 Varied data and market exclusivities provided to originator biologics delay biosimilar entry in all jurisdictions,134 with the FDA providing the longest exclusivity period and an additional exclusivity to the first interchangeable biosimilar.135

Our findings reveal that the regulatory environments in the EU and UK are most conducive to biosimilar approvals. EMA’s product-specific guidance documents provide clarity to applicants on the requirements for the approval of a range of biosimilar products, supporting the development of biosimilars.136 MHRA, newly reviewing biosimilar applications post-Brexit, has similar biosimilar testing requirements to EMA, and its policy not to require additional scientific justification for extrapolation lowers barriers to submission and approval.137

By contrast, the regulatory environment in the US is least conducive to biosimilar approvals and competition. FDA’s guidance documents lack the specificity of EMA guidance and were delayed, particularly with regard to the guidance on interchangeability.138 The interchangeability designation further sets a higher bar for approval, unique among the jurisdictions studied, which may impact the success of the US biosimilar market. The US also has the longest exclusivity periods, which combined with patent exclusivities delay biosimilar competition longer than all other jurisdictions studied.139 All these factors combined place additional challenges for manufacturers to develop, receive approval for, and successfully market a biosimilar compared to those present in other countries.

While the four factors discussed in this Article may contribute to some of the variation in biosimilar approval and utilization observed in these jurisdictions, they do not account for all the differences. Some variation in biosimilar approval and use may be attributed to the different timeline of the agencies’ experience with biosimilars.140 EMA has approved more biosimilars than the other medicines regulators but has also been approving biosimilars for several more than years than the other regulators—almost a decade longer than FDA.141 Much of the recent experience with biosimilar approvals has been in the past 5 years, limiting the data and research available on newer developments in regulator practices. However, the number of approvals by other regulators still have not caught up to the number of EMA approvals,142 though it is unclear the extent to which this is due to lack of submissions for biosimilar approvals or regulators not approving biosimilar applications. Other variation in the number of approvals may be due to differences in the categorization of certain products by and approval procedures of regulators. For example, some products that have been approved as biosimilars by EMA (including certain insulin, teriparatides, and enoxaparin sodium products) have been approved by FDA as drugs (under the New Drug Application, Abbreviated New Drug Application, or 505(b)(2) pathways).143 EMA may also receive multiple applications for one biosimilar product from one manufacturer and grant approvals under different trade names for public health or co-marketing purposes, increasing the number of its approvals.144 Still, even accounting for these differences, other medicines regulators lag behind EMA in biosimilar approvals and have only in recent years begun to approve biosimilars at similar rates.

Generally, we found that more specific guidance documents, more flexible testing requirements, greater use of indication extrapolation, shorter exclusivity periods, and laws in favor of biosimilar substitution were correlated with greater biosimilar approval and utilization. These policies make it easier and faster for biosimilars to be approved and used by patients and contribute to a regulatory environment supportive of biosimilar competition.

However, it is important to note that these were broad trends observed, not firm rules. Jurisdictions lacking some of these policies may still have high rates of biosimilar approval and utilization. The UK, for example, has the highest rate of biosimilar utilization of the jurisdictions studied—approaching 90%—despite national laws prohibiting biosimilar substitution.145 Other laws and policies, including insurance laws and hospital and pharmacy dispensing policies, may separately promote biosimilar use.146

Similarly, jurisdictions with some of these policies may still have lower rates of biosimilar approval and utilization than would be anticipated. For example, Australia has more specific guidance on biosimilar approvals, having adopted many of EMA’s guidance documents, and the shortest exclusivity period of any jurisdiction studied.147 The similarity between Australia’s and EMA’s biosimilar approval policies would suggest Australia would have approved more biosimilars compared to other jurisdictions studied. However, as of May 2024, Australia had only approved 55 biosimilars, compared to the EU’s 101.148 Some of this may be attributed to the EU’s lead time in biosimilar approvals (2006 compared to 2009 in Australia), but that alone does not explain the gap in approvals between the agencies. These cases highlight that while medicines regulations are important to support biosimilar approvals, they are not sufficient, and several other areas of law and policy influence the success of biosimilars in a given jurisdiction. Thus, in crafting reforms, it is important to consider other areas of law in addition to the laws and policies related to medicines regulators discussed in this Article.

Despite these limitations, reforms to medicines regulation and regulatory policy consistent with our findings would help to accelerate biosimilar approvals and uptake. First, the dissemination of more product-specific guidance documents by regulators would support manufacturers in the development of biosimilars. As regulators and manufacturers gain more experience with developing different types of biosimilars, product-specific guidance documents should be issued to help others in developing related biosimilar products. This is particularly important given the varied complexity of different types of biologic products.

Second, regulators should work to continue providing manufacturers with greater flexibilities in biosimilar testing requirements. As more evidence is collected regarding the types of studies necessary to show similarity, as has been seen related to clinical efficacy trials in all jurisdictions and related to interchangeability in the US, regulators should revise the study requirements for demonstrating biosimilarity. This evidence may also support greater use of indication extrapolation and clarify the circumstances where extrapolation is most appropriate.

Third, policies supporting indication extrapolation, such as a default rule approving biosimilars for all originator biologic indications, barring remaining exclusivities, may improve regulators’ review of biosimilar applications and promote access to biosimilars for a greater number of patients.

Fourth, shorter exclusivity periods provided with the approval of reference products would allow biosimilars to come to market faster, saving both patients and health systems money. These changes may be limited by patent exclusivities, and therefore exclusivity reforms should consider the intellectual property environment as a whole to accelerate biosimilar competition and access.

Finally, medicines regulators should continue uphold the clinical equivalence of biosimilars to their reference products, supporting a regulatory environment in favor of biosimilar substitution. The guidance from EMA and MHRA on biosimilar interchangeability is a positive step towards greater biosimilar use, bolstering trust in the clinical equivalence of biosimilars and originator biologics. In addition to guidance, medicines regulators should commit to rigorous post-approval surveillance to reinforce that greater facilitation of biosimilar substitution is safe and appropriate. Additional requirements for substitution, including interchangeability designations, should be reconsidered in light of these studies.149 However, since ultimate decisions regarding substitution are made by other government bodies, reforms at the regulatory level alone would not be enough to address the issue.

Many different regulators and government agencies will need to contribute to the implementation of these reforms. Some of these reforms may be implemented directly by the regulators themselves, such as issuing guidance documents and communicating the data and study requirements for biosimilar approval and indication extrapolation. Some of these reforms would require legislative changes, including changes to data and market exclusivities, FDA’s interchangeability designation, and biosimilar substitution laws. Other regulators would also be affected by these reforms, including government insurers and patent agencies. Medicines regulators should collaborate with these government bodies to advocate for and develop laws and policies supporting the approval and uptake of biosimilars.

VII. CONCLUSION

Variation in medicines regulator approaches for biosimilar approvals, particularly concerning biosimilar testing requirements, indication extrapolation, exclusivities, and substitution, contribute to the varied success of biosimilars across different international markets. Reforms to these policies can create a regulatory environment more supportive of biosimilar approvals, promoting access to more affordable biologics for the benefit of patients globally.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Aaron S. Kesselheim for his comments on an earlier draft and Victor Van de Wiele for his insight on UK and EU regulatory policy. We would also like to thank Alexus Witherell for her excellent research assistance. This work arose from a grant from Arnold Ventures. Knox’s fellowship was funded by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science.

Footnotes

See What Are ‘Biologics’ Questions and Answers, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2018), https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-biologics-evaluation-and-research-cber/what-are-biologics-questions-and-answers; Thomas Morrow & Linda Hull Felcone, Defining the difference: What Makes Biologics Unique, 1(4) Biotechnology Healthcare 24, 24–26, 28–29 (2004).

Mike Z. Zhai, Ameet Sarpatwari, & Aaron S. Kesselheim, Why are biosimilars not living up to their promise in the US?, 21 Am. Med. Ass’n J. Ethics e668, e668 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2019.668.

See Kathlyn Stone, Top 10 Biologic Medications in the United States, Verywell Health (Dec. 27, 2023), https://www.verywellhealth.com/top-biologic-drugs-2663233; Elif Car et al., Biosimilar competition in European markets of TNF-alpha inhibitors: a comparative analysis of pricing, market share and utilization trends, 14 Frontiers in Pharmacology 1,151,764 (2023), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10160635/.

Avik Roy, The growing power of biotech monopolies threaten Affordable Care, Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (Sept. 15, 2020), https://freopp.org/the-growing-power-of-biotech-monopolies-threatens-affordable-care-e75e36fa1529; Trends in public drug program spending in Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information (2022), https://www.cihi.ca/en/trends-in-public-drug-program-spending-in-canada#ref17.

See Yvonne Zhang & Caroline Peterson, Biosimilars in Canada: building momentum in the wake of recent switching policies, Government of Canada (Nov. 2021), https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/pmprb-cepmb/documents/npduis/analytical-studies/slide-presentations/biosimilars-cadth/Biosimilars%20in%20Canada_CADTH%20Nov%202021.pdf; Per Troein, Max Newton, & Kirstie Scott, The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe, IQVIA Institute (Dec. 2020), https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/emea/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-iqvia.pdf.

Bob Herman, The Keytruda boom, Axios (Oct. 29, 2021), https://www.axios.com/2021/10/29/keytruda-sales-merck-drug-prices.

Hannah McQueen, The 10 most expensive drugs in the US, period, GoodRx Health (June 2, 2022), https://www.goodrx.com/healthcare-access/drug-cost-and-savings/most-expensive-drugs-period.

Biosimilar medicines regulation, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Therapeutic Goods Administration (2018), https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/resource/guidance/biosimilar-medicines-regulation [hereinafter ‘Australia Biosimilars I’]; Biosimilar biologic drugs, Government of Canada (2023), https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/biologics-radiopharmaceuticals-genetic-therapies/biosimilar-biologic-drugs.html; Biosimilar medicines: Overview, European Medicines Agency (2023), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview; Guidance on the licensing of biosimilar products, Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (2022), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-on-the-licensing-of-biosimilar-products/guidance-on-the-licensing-of-biosimilar-products [hereinafter ‘MHRA Guidance’]; Biosimilars Review and Approval, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2022), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/review-and-approval.

See Zhai, Sarpatwari, & Kesselheim, supra note 2, at e668-e673.

Biosimilar product information, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2024), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information.

Medicines, European Medicines Agency (2024), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/search_api_aggregation_ema_medicine_types/field_ema_med_biosimilar.

Products, Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (2024), https://products.mhra.gov.uk.

Drug product database online query, Government of Canada (2024), https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/dispatch-repartition#results.

Biosimilar medicines approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Therapeutic Goods Administration (2024), https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-05/biosimilar-medicines-approved-by-the-therapeutic-goods-administration_0.pdf.

See, e.g., Uptake of biosimilars in different countries varies, Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (Nov. 8, 2019), https://gabionline.net/reports/Uptake-of-biosimilars-in-different-countries-varies; Skylar Jeremias, Biosimilar awareness week proves successful for Australia, American Journal of Managed Care The Center for Biosimilars (July 13, 2020), https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/view/biosimilar-awareness-week-proves-successful-for-australia. See also Per Troein et al., The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe, IQVIA Institute (2023), https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2023.pdf (showing variations in biosimilar uptake across countries in Europe).

Anna-Katharina Böhm, Isa Maria Steiner, & Tom Stargardt, Market diffusion of biosimilars in off-patent biologic drug markets across Europe, 132 Health Policy 104,818 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2023.104818.

Per Troein et al., The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe, IQVIA Institute (2021), https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2021.pdf.

Emily May & Karen Taylor, The cost-effectiveness of biosimilars and their future potential for the NHS, Deloitte (May 21, 2021). https://blogs.deloitte.co.uk/health/2021/05/the-cost-effectiveness-of-biosimilars-and-their-future-potential-for-the-nhs.html#:~:text=The%20NHS‘s%20continuing%20encouragement%20of,versions%20of%20top%2Dselling%20biologics.

Jeremias, supra note 15; Prescribed Drug Spending in Canada, 2020: A focus on public drug programs, Canadian Institute for Health Information (2020), https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/prescribed-drug-spending-in-canada-2020-report-en.pdf.

Murray Aitken, Michael Kleinrock, Elyse Muñoz, Biosimilars in the United States, 2020–2024: Competition, savings, and sustainability, IQVIA Institute (2020), https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/iqvia-institute-biosimilars-in-the-united-states.pdf; The U.S. generic and biosimilar medicines savings report, Association for Accessible Medicines (2021), https://accessiblemeds.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/AAM-2021-US-Generic-Biosimilar-Medicines-Savings-Report-web.pdf.

See Zhai, Sarpatwari, & Kesselheim, supra note 2, at e670-e671; Ameet Sarpatwari et al., The US Biosimilar Market: Stunted Growth and Possible Reforms, 105 Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 92, 95–97 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1285; Ryan Knox, Insulin insulated: barriers to competition and affordability in the United States insulin market, 7 Journal of Law and the Biosciences lsaa061 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/jlb/lsaa06, Victor L. Van de Wiele, Aaron S. Kesselheim, & Ameet Sarpatwari, Barriers To US Biosimilar Market Growth: Lessons From Biosimilar Patent Litigation, 40 Health Affairs 1198, 1198–1204 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02484.

See Zhai, Sarpatwari, & Kesselheim, supra note 2, at e671; Sarpatwari et al., supra note 21, at 98; Sabine Vogler et al., Policies to Encourage the Use of Biosimilars in European Countries and Their Potential Impact on Pharmaceutical Expenditure, 12 Frontiers in Pharmacology 625,296, 625,296 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.625296.

See Aaron Hakim & Joseph S. Ross, Obstacles to the Adoption of Biosimilars for Chronic Diseases, 317(21) JAMA 2163, 2163–64 (2017).

See Sarpatwari et al., supra note 21, at 93, 97; Vogler et al., supra note 22, at 625296; Chana A. Sacks et al., Assessment of Variation in State Regulation of Generic Drug and Interchangeable Biologic Substitutions, 181 JAMA Internal Medicine 16, 16–22 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3588.

See Anita Afzali et al., The Automatic Substitution of Biosimilars: Definitions of Interchangeability are not Interchangeable, 38 Advances in therapy 2077, 2077–2088 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01688-9; Christopher J. Webster & Gillian R. Woollett, A ‘Global Reference’ Comparator for Biosimilar Development, 31 BioDrugs: clinical immunotherapeutics, biopharmaceuticals and gene therapy 279, 279–286 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-017-0227-4; Lutz Heinemann et al., An Overview of Current Regulatory Requirements for Approval of Biosimilar Insulins, 17(7) Diabetes technology & therapeutics 510, 510–526 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2014.0362; Mark A. Socinski et al., Clinical considerations for the development of biosimilars in oncology, 7 mAbs 286, 286–293 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2015.1008346. In general, we consider that the number of biosimilars approved and the rate of biosimilar uptake are indicative of how successful the legal and regulatory environment of a jurisdiction are in supporting biosimilar competition and lowering drug prices.

See Sarfaraz K. Niazi, Waleed Mohammed Al-Shaqha, & Zafar Mirza, Proposal of International Council for Harmonization (ICH) Guideline for the Approval of Biosimilars, 11(1) Journal of Market Access & Health Policy 2,147,286, 2,147,286 (2023); IPRP Biosimilars Working Group (BWG) Workshop – Updated, International Pharmaceutical Regulators Programme (Aug. 23, 2023), https://www.iprp.global/news/iprp-biosimilars-working-group-bwg-workshop-updated.

Australia Biosimilars I, supra note 8; MHRA Guidance, supra note 8; Guidance Document: Information and Submission Requirements for Biosimilar Biologic Drugs, Health Canada (2023), https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/drugs-health-products/biologics-radiopharmaceuticals-genetic-therapies/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/information-submission-requirements-biosimilar-biologic-drugs/information-submission-requirements-biosimilar-biologic-drugs.pdf [hereinafter ‘Health Canada Guidance’]; Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product: Guidance for Industry, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2015), https://www.fda.gov/media/82647/download [hereinafter ‘FDA Guidance I’]; Guideline on similar biological medicinal products, European Medicines Agency (2014), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-rev1_en.pdf [hereinafter ‘EMA Guidance I’]; Justin Stebbing et al., Understanding the role of comparative clinical studies in the development of oncology biosimilars, 38 Journal of Clinical Oncology 1070, 1070–80 (2020), doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02953; Richard Markus et al., Developing the Totality of Evidence for Biosimilars: Regulatory Considerations and Building Confidence for the Healthcare Community, 3 BioDrugs 175, 176–83 (2017), doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0218-5.

See Stebbing et al., supra note 27, at 1070–72; Markus et al., supra note 27, at 177–182.

Markus et al., supra note 25, at 177–182; FDA Guidance I, supra note 25, at 9–10.

Markus et al., supra note 25, at 177–180.

See Liang Zhao, Tian-hua Ren, & Diane D. Wang, Clinical pharmacology considerations in biologics development, 33(11) Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 1339, 1339–47 (2012), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4011353/.

See Stebbing et al., supra note 25, at 1070–72.

Edward C. Li et al., Considerations in the early development of biosimilar products, 20 Drug Discovery Today 1, 3 (2015); Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, European Commission (2010), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010:276:0033:0079:en:PDF.

Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues, European Medicines Agency (2014), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-biotechnology-derived-proteins-active_en-2.pdf (hereinafter ‘EMA Guidance II’); see also Chamindika S. Konara et al., The tortoise and the hare: evolving regulatory landscapes for biosimilars, 34 Trends in Biotechnology 70, 77 (2016). Note Australia has adopted most of EMA’s guidance documents related to biosimilars, including Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues.

FDA Guidance I, supra note 25.

Development of Therapeutic Protein Biosimilars: Comparative Analytical Assessment and Other Quality-Related Considerations: Guidance for Industry, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2019), https://www.fda.gov/media/159261/download (‘FDA will best be able to provide meaningful input on the extent and scope of animal and additional clinical studies for a proposed biosimilar development program once the Agency has considered the comparative analytical data.’).

Health Canada Guidance, supra note 25.

MHRA Guidance, supra note 8 (‘No in vivo studies from animals are requested as these are not relevant for showing comparability between a biosimilar candidate and its RP: this includes pharmacodynamic studies, kinetic studies and toxicity studies.’).

See Stebbing et al., supra note 25, at 1070–72.

MHRA Guidance, supra note 8.

See Australia Biosimilars I, supra note 8; EMA Guidance II, supra note 31; FDA Guidance I, supra note 25; Health Canada Guidance, supra note 25. See also Stebbing et al., supra note 25, at 1071–1078. For more on regulatory perspectives of when alternatives to comparative clinical efficacy studies are appropriate in biosimilar development, see, e.g., Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers for Biosimilar Development and Approval, Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy (2021), https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/events/biosimilar (materials and recordings of conference on pharmacodynamic biomarkers for biosimilar development and approval).

See, e.g., EMA Guidance II, supra note 31 (describing when comparative clinical efficacy trials are not required for biotechnology-derived protein biosimilars); Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing monoclonal antibodies – non-clinical and clinical issues, European Medicines Agency (2012), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-monoclonal-antibodies-non-clinical-and-clinical-issues_en.pdf (describing when comparative clinical efficacy trials are not required for monoclonal antibody biosimilars). EMA has also proposed waiving this requirement for certain classes of biosimilars, including oncology treatments containing recombinant granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, in part based on comparative pharmacodynamic studies. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing recombinant granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (rG-CSF), European Medicines Agency (2018), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-recombinant-granulocyte-colony_en.pdf; see also Stebbing et al., supra note 25, at 1077 (“For granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, for example, structure, physicochemical characteristics, and biologic activity can be well characterized, and clinically relevant PD parameters are available. Whereas the original version of the EMA guidance concerning biosimilar granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (published in 2006) includes significant emphasis on comparative clinical efficacy and safety trials, a draft revision to the guideline (released in 2018 for consultation) stated that a dedicated comparative efficacy trial is ‘not considered necessary.’”).

See Assessment Report: Sondelbay, European Medicines Agency (Mar. 30, 2022), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/sondelbay-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf.

See Health Canada Guidance, supra note 25.

See FDA Guidance I, supra note 25.

See id.; Clinical Pharmacology Data To Demonstrate Biosimilarity To A Reference Product, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2016), https://www.fda.gov/media/88622/download; see also Sarfaraz Niazi, Scientific Rationale for Waiving Clinical Efficacy Testing of Biosimilars, 16 Drug design, development and therapy, 2803, 2805, 2810 (2022), https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S378813; Junyi Li et al., Advancing Biosimilar Development Using Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers in Clinical Pharmacology Studies, 107 Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 40, 40–42 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1653.

See Summary Review: Cyltezo, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2017), https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2017/761058Orig1s000SumR.pdf.

See Pre-submission meetings with TGA, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Therapeutic Goods Administration (2020), https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/resource/guidance/pre-submission-meetings-tga (TGA meeting policies and procedures); Scientific advice and protocol assistance, European Medicines Agency (2023), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/research-and-development/scientific-advice-and-protocol-assistance (EMA meeting procedures); Formal Meetings Between the FDA and Sponsors or Applicants of BsUFA Products: Guidance for Industry, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2023), https://www.fda.gov/media/113913/download (FDA meeting guidance); Health Canada Guidance, supra note 25 (Health Canada meeting policies and procedures); Guidance Medicines: get scientific advice from MHRA, Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (2022), https://www.gov.uk/guidance/medicines-get-scientific-advice-from-mhra (MHRA meeting policies and procedures).

See Development of Therapeutic Protein Biosimilars: Comparative Analytical Assessment and Other Quality-Related Considerations: Guidance for Industry, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2019), https://www.fda.gov/media/159261/download.

See generally Health Canada Guidance, supra note 25.

See generally Biosimilars Guidances, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2021), https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/general-biologics-guidances/biosimilars-guidances (collecting FDA guidance documents on biosimilars). But see Clinical immunogenicity considerations for biosimilar and interchangeable insulin products, U.S. Food &Drug Administration (2018), https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-immunogenicity-considerations-biosimilar-and-interchangeable-insulin-products (FDA guidance document specifically for biosimilar insulins).

See Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing monoclonal antibodies – non-clinical and clinical issues, European Medicines Agency (2012), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-monoclonal-antibodies-non-clinical-and-clinical-issues_en.pdf; Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing monoclonal antibodies – non-clinical and clinical issues, European Medicines Agency (2012), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-monoclonal-antibodies-non-clinical-and-clinical-issues_en.pdf; Guideline on non-clinical and clinical development of similar biological medicinal products containing low-molecular-weight-heparins, European Medicines Agency (2016), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-non-clinical-and-clinical-development-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-low-molecular-weight-heparins-revision-1_en.pdf; Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing interferon beta, European Medicines Agency (2013), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-interferon-beta_en.pdf; Annex to Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues; Guideline on similar medicinal products containing somatropin, European Medicines Agency (2018), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/annex-guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-biotechnology-derived-proteins-active-substance-non-clinical-and-clinical-issues-revision-1_en.pdf. See generally Multidisciplinary: biosimilar, European Medicines Agency (2023), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/scientific-guidelines/multidisciplinary/multidisciplinary-biosimilar (collecting EMA’s general and product-specific biosimilar guidance documents).

MHRA Guidance, supra note 8; International scientific guidelines adopted in Australia, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Therapeutic Goods Administration (2023), https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/resource/international-scientific-guidelines.

In addition to the later start to FDA approvals, some scholars have also pointed to the delay in FDA providing guidance on biosimilars, in particular guidance on interchangeability, as a historical contributor to FDA’s lagging behind EMA in FDA approvals. See, e.g., Jing Luo, Aaron S. Kesselheim, & Ameet Sarpatwari, Insulin access and affordability in the USA: anticipating the first interchangeable insulin product, 8 The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology 360, 360–362 (2020) (discussing FDA’s delayed guidance on the approval of interchangeable biosimilars).

See, e.g., Markus Gores & Kirstie Scott, Success Multiplied: Launch Excellence for Multi-Indication Assets: How to capture the full potential of a pipeline in a product, IQVIA Institute (2023), https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/iqvia-launch-excellence-for-multi-indication-assets-02-23-forweb.pdf (describing multi-indication biologic products).

See Daniel Feldman, Jerry Avorn, & Aaron S. Kesselheim, Use of Extrapolation in New Drug Approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration, 5 JAMA Network Open e227958, e227958 (2022), doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7958; Martina Weise et al., Biosimilars: the science of extrapolation, 124 Blood 3191, 3191–3196 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-06-583617.

See Feldman, Avorn, & Kesselheim, supra note 56.

MHRA Guidance, supra note 8.

Australia Biosimilars I, supra note 8; Health Canada Guidance, supra note 25; EMA Guidance I, supra note 25; FDA Guidance I, supra note 25.

John R.P. Tesser, Daniel E. Furst, & Ira Jacobs, Biosimilars and the extrapolation of indications for inflammatory conditions, 11 Biologics 5, 5–11 (2017), https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S124476.

Inflectra (infliximab), European Medicines Agency (2022), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inflectra; Remsima (infliximab), European Medicines Agency (2023), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/remsima; see also Socinski et al., supra note 25, at 290–91 (comparing EMA’s extrapolation of infliximab biosimilars to Health Canada).

Regulatory Decision Summary for INFLECTRA, Government of Canada (2016), https://dhpp.hpfb-dgpsa.ca/review-documents/resource/RDS00124; Regulatory Decision Summary for REMSIMA, Government of Canada (2016), https://dhpp.hpfb-dgpsa.ca/review-documents/resource/RDS00177; see also Socinski et al., supra note 25, at 290–91 (comparing EMA’s extrapolation of infliximab biosimilars to Health Canada).

Regulatory Decision Summary for INFLECTRA, supra note 62; Regulatory Decision Summary for REMSIMA, supra note 62.

See Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Application Number: 125544Orig1s000, Other Review(s): Inflectra, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2016), https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2016/125544Orig1s000OtherR.pdf (noting a complete response letter was set by FDA regarding additional evidence needed for certain Inflectra indications).

See, e.g., Summary Basis of Decision for Brenzys, Government of Canada (2016), https://dhpp.hpfb-dgpsa.ca/review-documents/resource/SBD00333 (noting the applicant did not request approval for all of the originator biologic’s indications); Alexander C. Egilman et al., Frequency of Approval and Marketing of Biosimilars With a Skinny Label and Associated Medicare Savings, 183 Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine 82, 82–84 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.5419 (describing frequency of skinny labelling, when biosimilars are not approved for all indications of the originator biologic); Anna Hung, Quyen Vu, & Lisa Mostovoy, A Systematic Review of U.S. Biosimilar Approvals: What Evidence Does the FDA Require and How Are Manufacturers Responding?, 23(12) Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy 1234, 1239 (2017) (describing instances when biosimilars were not approved for all indications of the originator biologic); Updates on biosimilars: Member State Meeting WHO Access to Medicines and Health Products Division, World Health Organization (2022), https://apps.who.int/gb/MSPI/pdf_files/2022/12/Item1_01-12.pdf (listing barriers to biosimilar competition, including market and trade barriers).

Section 25A(2) Therapeutic Goods Legislation Amendment Act 1998 (Australia exclusivity); Guidance document: data protection under C.08.004.1 of the Food and Drug Regulations, Government of Canada (2021), https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/guidance-document-data-protection-under-08-004-1-food-drug-regulations.html (Canada exclusivity); Directive 2001/83/EC, as amended by Directive 2004/27/EC, Art. 10.1, European Medicines Agency (2004), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/directive-2001/83/ec-european-parliament-council-6-november-2001-community-code-relating-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf (EU exclusivity); Guidance for industry reference product exclusivity for biological products filed under Section 351(a) of the PHS Act US Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2014), https://www.fda.gov/media/89049/download (US exclusivity); MHRA Guidance, supra note 8 (UK exclusivity).

See Bryan Oronsky et al., Patent and Marketing Exclusivities 101 for Drug Developers, 17 Recent patents on biotechnology 257, 261–62 (2023), https://doi.org/10.2174/1872208317666230111105223 (defining data and market exclusivities); Data exclusivity is not the same as market exclusivity, Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (Jan. 26, 2010), https://www.gabionline.net/policies-legislation/Data-exclusivity-is-not-the-same-as-market-exclusivity#:~:text=Simply%20put%2C%20during%20the%20period,to%20enter%20a%20specific%20market (description of data and market exclusivities). In some of the jurisdictions, additional exclusivities may apply if the biologic treats a rare disease, fills an unmet need in medical treatment, or qualifies for another specialty period of protection. See, e.g., Data exclusivity, market protection, orphan and paediatric rewards, European Medicines Agency (2018), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/presentation/presentation-data-exclusivity-market-protection-orphan-and-paediatric-rewards-s-ribeiro_en.pdf (discussion of other EMA exclusivities); Frequently Asked Questions on Patents and Exclusivity, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2020), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/frequently-asked-questions-patents-and-exclusivity (listing other types of FDA exclusivities); Guidance: Orphan Medical Products, Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (2021), https://www.gov.uk/guidance/orphan-medicinal-products-in-great-britain#review-of-market-exclusivity-period (discussing exclusivities for rare diseases).

Oronsky et al., supra note 67, at 261–62.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.