Abstract

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is a major global health concern due to its high mortality and disability rates. Hemorrhagic transformation, a common complication of AIS, leads to poor prognosis yet lacks effective treatments. Preclinical studies indicate that hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) treatment within 12 h of AIS onset alleviates ischemia/reperfusion injuries, including hemorrhagic transformation. However, clinical trials have yielded conflicting results, suggesting some underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, we confirmed that HBO treatments beginning within 1 h post reperfusion significantly alleviated the haemorrhage and neurological deficits in hyperglycemic transient middle cerebral arterial occlusion (tMCAO) mice, partly due to the inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pro-inflammatory response in microglia. Notably, reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediate the anti-inflammatory and protective effect of early HBO treatment, as edaravone and N-Acetyl-l-Cysteine (NAC), two commonly used antioxidants, reversed the suppressive effect of HBO treatment on NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation in microglia. Furthermore, NAC countered the protective effect of early HBO treatment in tMCAO mice with hyperglycemia. These findings support that early HBO treatment is a promising intervention for AIS, however, caution is warranted when combining antioxidants with HBO treatment. Further assessments are needed to clarify the role of antioxidants in HBO therapy for AIS.

Keywords: Hyperbaric oxygen, Ischemic stroke, Hemorrhagic transformation, Microglia, NLRP3 inflammasome, ROS

Subject terms: Neurological disorders, Stroke

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is a significant global health concern, due to its high rates of mortality and disability. It is typically classified into ischemic stroke, caused by the occlusion of cerebral blood flow, or hemorrhagic stroke, attributed to the rupture of cerebral blood vessels1. Hemorrhagic transformation (HT) is a common complication in patients with AIS2. Recanalization therapies like intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) administration seem to increase the likelihood of HT3. Additionally, hyperglycemia is recognized as a risk factor for HT post ischemic stroke4,5. HT is closely associated with worse outcomes6,7, and current interventions remain limited. Therefore, there is an urgent need for effective management strategies.

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy–– the therapeutic use of pure oxygen under more than one atmosphere pressure (generally in the range of 1–3 ATA) –– has been successfully applied in a bunch of conditions, especially those with hypoxia as a pathological feature8,9. HBO has natural advantages in treating central neuronal system diseases as it can freely penetrate the brain-blood barrier (BBB). The beneficial effects of HBO treatment are consistent when administered before the onset of ischemia (preconditioning) or during the recovery phase from neurological damage in the chronic stage10,11. However, controversy exists in its application in the acute phase12. Preclinical studies show HBO treatment initiated within a short time window (12 h) from the onset of AIS protects the brain against ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injuries12,13, and mitigates HT in transient middle cerebral arterial occlusion (tMCAO) rat model with hyperglycemia14,15. Despite promising preclinical outcomes, clinical trials investigating early HBO use in AIS have yielded mixed results12, highlighting the necessity for further exploration of its underlying mechanisms. In clinical practice, HBO is often employed adjunctively with other therapies, which complicates the assessment of its efficacy. In contrast, controlled animal studies offer insights into HBO’s mechanisms without the interference of concurrent treatments, presenting a valuable opportunity to elucidate these mechanisms and advance its clinical utility.

HT is caused by the destruction of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), a continuous layer of endothelial cells connected by tight junctions. Inflammation plays a pivotal role in BBB dysfunction, with microglia, the resident macrophages in the brain responsible for maintaining homeostasis in the central nervous system, being a primary source of inflammation. During the early stage of cerebral ischemic/reperfusion, activated microglia release pro-inflammatory factors like interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), which further boosts the pro-inflammatory response by recruiting other immune cells such as neutrophils, ultimately leading to secondary injury post-ischemic stroke16–18. Among the inflammatory pathways activated post-ischemic stroke, the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome pathway is particularly significant19,20. It is present in multiple cell types, including microglia, endothelial cells, and neurons21,22. Suppression of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway has been shown to reduce infarction and BBB damage after ischemic stroke23–27.

Previous studies have documented that HBO treatment can suppress microglial activation and mitigate neuroinflammation in multiple conditions, such as traumatic brain injuries28–30, Alzheimer’s disease31, permanent focal cerebral ischemia32 and spinal cord injury33. Additionally, HBO treatment has been shown to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome signaling in traumatic brain injuries34 and carbon monoxide poisoning35. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate whether HBO treatment administered during the superacute phase (within 1 h after reperfusion) could attenuate the pro-inflammatory response of microglia, thereby leading to its protective role against HT. The study also sought to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

Results

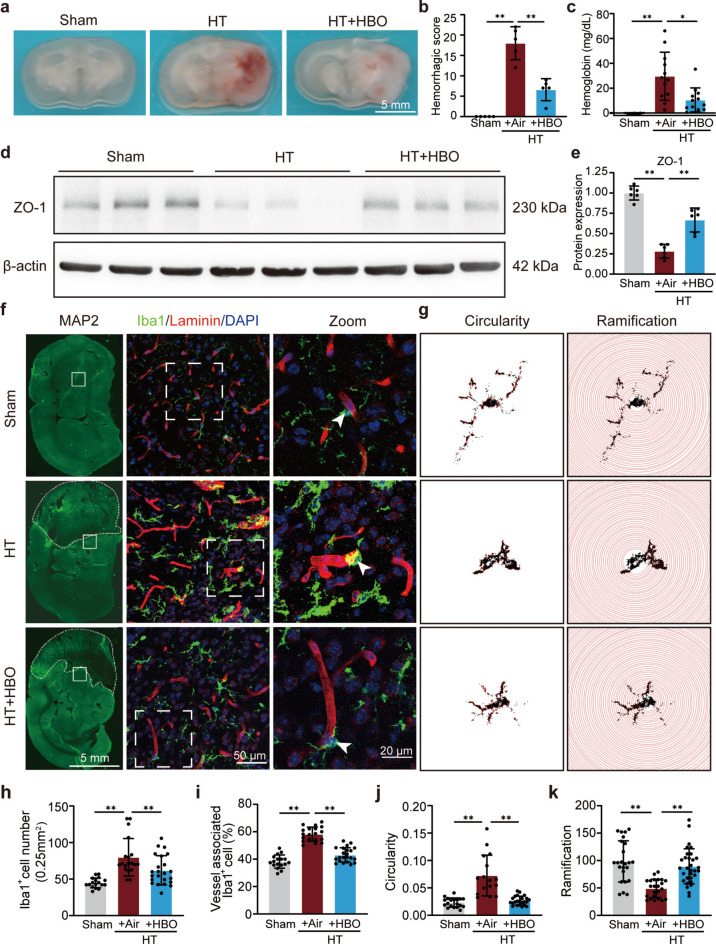

Early HBO treatment alleviated HT and perivascular microglia/macrophage activation post I/R in hyperglycemic mice

To assess the efficacy of early HBO treatment (administrated within 1 h post reperfusion) on HT, a hyperglycemia-induced HT murine model was adopted. Twenty-four hours post-reperfusion, compared to the sham group, the HT group exhibited a significant increase in hemorrhagic score, which was suppressed in the HBO treatment group (Fig. 1a,b). Consistent results were observed in the hemoglobin content analysis (Fig. 1c). Since ZO-1, also known as Zonula Occludens-1, is a tight junction protein critical for maintaining the integrity and functionality of the blood–brain barrier, we detected its protein level in the ipsilateral brain tissue. Our results showed a decrease in ZO-1 protein levels in the HT group compared to sham, which was effectively reversed by HBO treatment (Fig. 1d,e). Furthermore, HBO treatment reduced the infarction area and improved neurological behavior (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results confirm the protective effect of early HBO treatment in the HT mouse model.

Fig. 1.

Early HBO treatment alleviated HT and perivascular microglia/macrophage activation post I/R injury in hyperglycemic mice. (a) Representative images of coronal brain sections to show the hemorrhagic level. (b) Hemorrhagic score in each group as indicated (n = 5). (c) Measurements of hemoglobin level in each group as indicated (n = 3–12). (d) Protein levels of ZO-1 in the ipsilateral striatum 24 h post-reperfusion with indicated treatments detected by western blot. β-actin was used as the endogenous control. The cropped blot images are shown, and the raw blot images can be found in the supplementary information. (e) Quantification of ZO-1 WB results (n = 6). (f) Representative images of coronal brain sections at 24 h post-reperfusion. Left panels: MAP2 (green, neuron marker to show the infarct area demarcated with white dashed lines). Middle panels: Iba1 (microglia/macrophage marker, green), laminin (blood vessel marker, red) and DAPI (nuclear, blue) staining of the region in the ipsilateral striatum marked by white boxes in the corresponding top panel. Right panels: the zoom-in picture of the white box-marked region in the corresponding middle panel. (g) Illustration of cell ramification and circularity analyses of representative microglia/macrophage of each group. (h and i) Quantification of the number of Iba1 positive cells (h) and blood vessel-associated Iba1 positive cells (i) in each view field. Seventeen to twenty-three view fields from three mice in each group were analyzed. (j and k) Quantitative analysis of circularity (j) and ramification (k). Nineteen to twenty-five intact cells from three mice in each group were analyzed. The results are represented as mean ± s.d., *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Statistical analyses except for (i, j, and k) were conducted by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For (i, j, and k), the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was adopted.

Considering the crucial role of microglia activation in neuroinflammation and BBB damage16, and the strong correlation between microglia morphology and activation status, perivascular microglia/macrophage in the penumbra were examined through immunostaining of Iba1 (a marker of microglia/macrophage), and laminin (a blood vessels marker). The results showed that Iba1 protein levels, Iba1+ cell number, and the ratio of Iba1+ cells surrounding blood vessels in the penumbra region were increased in the HT group compared to the sham group, HBO treatment not only suppressed the increase of Iba1+ cell number but also prevented the redistribution of Iba1+ cells to blood vessels (Fig. 1f,h,i). Additionally, the Iba1+ cells in the HBO treatment group exhibited more ramified morphology and had longer processes compared to those in the HT group, closer to the morphology observed in the sham group (Fig. 1g,j,k). These results indicate that HBO treatment alleviated perivascular microglia/macrophage activation in the ischemic penumbra.

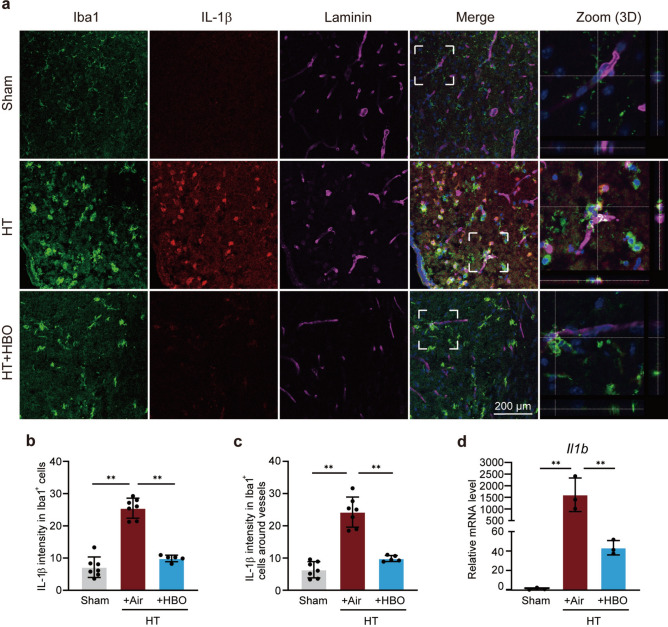

Early HBO treatment inhibited IL-1β elevation in microglia/macrophage post I/R in hyperglycemic mice

IL-1β is a primary pro-inflammatory factor that drives the inflammatory response of microglia/macrophages. Immunostaining results showed that HBO treatment dramatically reduced the IL-1β level in all microglia/macrophage (Iba1+ cells, Fig. 2a,b) as well as in perivascular microglia/macrophage in the penumbra (Fig. 2a,c). Moreover, early HBO treatment nearly completely blocked the elevation of Il1b (encoding IL-1β) mRNA in the ipsilateral brain tissues, as demonstrated by the reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis (Fig. 2d). These findings provide further evidence that HBO treatment suppresses the pro-inflammatory response of microglia.

Fig. 2.

Early HBO treatment inhibited IL-1β elevation in microglia/macrophage post I/R injury in hyperglycemic mice. (a) Representative images of coronal brain sections at 24 h post-reperfusion. Staining of Iba1 (microglia/macrophage marker; green), IL-1β (red), Laminin (blood vessel marker; violet), and DAPI (blue) were shown as indicated. Zoom in of the white dash boxes marked region were shown in the rightmost panels to show the colocalization of Iba1+ cells and Laminin+ blood vessels. (b and c) Average IL-1β intensity in Iba1+ cells (b) and perivascular Iba1+ cells (c) in each group as indicated. Five to seven view fields from 3 mice in each group were analyzed. (d) Relative mRNA levels of Il1b in the ipsilateral striatum 24 h post-reperfusion (n = 3). The results are represented as mean ± s.d., *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Statistical analyses were conducted by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

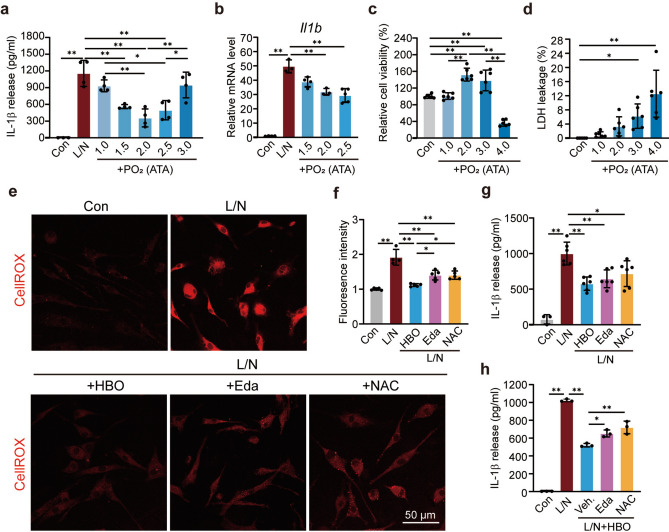

Early HBO treatment directly suppressed the activation of the NF-κB/NLRP3/IL-1β signaling pathway in microglia through reactive oxygen species (ROS)

To confirm the direct inhibition of IL-1β elevation in microglia by HBO treatment, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and nigericin (L/N) stimulated primary microglia cell model was used, mimicking the NLRP3 inflammasome mediated inflammation36, a primary source of IL-1β post-ischemic stroke19,20. The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway not only produces IL-1β but also promotes its release through the pores formed by the N terminal of Gasdermin D on the cytoplasmic membrane21. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results showed that L/N induced a high release of IL-1β from microglia, while oxygen treatment under different pressures at the beginning of LPS stimulation inhibited IL-1β release to different degrees. Among all the tested conditions, 2.0 and 2.5 ATA showed the most significant effects, and HBO showed a superior effect compared to pure oxygen treatment under normal pressure (Fig. 3a). Similar results were observed in the mRNA level of Il1b, as demonstrated by RT-qPCR (Fig. 3b). Besides, HBO treatment also suppressed the elevation of other pro-inflammatory genes, including Tnfa (encoding TNFα), Il6 (encoding IL6) and Nos2 (encoding inducible nitric oxide synthase 2) (Supplementary Fig. S2), confirming the direct inhibition of the inflammatory response in microglia by early HBO treatment.

Fig. 3.

Early HBO treatment directly suppressed the activation of the NF-κB/NLRP3/IL-1β signaling pathway in microglia via reactive oxygen species (ROS). (a) The released IL-1β level in cell culture media detected by ELISA in lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and nigericin (L/N) stimulated primary microglia (n = 3–4). The oxygen treatments were applied under indicated pressures. (b) Relative mRNA levels of Il1b in the L/N stimulated primary microglia (n = 4). The oxygen treatments were applied under indicated pressures. (c) Relative cell viability of primary microglia cells exposed to oxygen under indicated pressures (n = 6). The cell viability of the control group was set as 100%. (d) LDH leakage of primary microglia cells exposed to oxygen under indicated pressures (n = 6). (e) The representative ROS imaging labeled by the ROS probe CellROX in the primary microglia cells. (f) The statistic of the fluorescent intensity of CellROX in primary microglia (n = 4–5). (g and h) The released IL-1β level in cell culture media was detected by ELISA in the primary microglia cells with indicated treatment (n = 3–6). The results are represented as mean ± s.d., *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Statistical analyses were conducted by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

To determine the appropriate condition for in vitro studies, the cell status was evaluated under different oxygen treatment conditions. Oxygen treatment under 2.0 ATA almost had no harmful impact on cell status reflected by the evaluation of cell viability and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage (a marker of cell damage), 3.0 ATA began to show mild toxicity as the LDH leakage increased (Fig. 3c,d). Considering the anti-inflammation effect, we chose 2.5 ATA in the subsequent cell research, to maintain consistency with the animal studies.

The mechanism of how HBO inhibits the inflammatory activation of microglia was then investigated. ROS are known triggers and boosters of microglia proinflammatory response and NLRP3 inflammasome activation37. Reperfusion causes a harmful high level of ROS production, which contributes to most of the I/R injuries in patients with AIS38. Therefore, ROS levels in primary microglia were detected using the ROS probe CellROX. L/N stimulation dramatically increased cellular ROS levels, and HBO treatment inhibited ROS elevation to a great extent (Fig. 3e,f). To compare the effect on ROS inhibition, edaravone, an antioxidant used for the treatment of patients with AIS in the clinic, and N-Acetyl-l-Cysteine (NAC), another commonly used antioxidant were administrated paralleled, and found that HBO treatment inhibits ROS elevation even better than the two antioxidants (Fig. 3e,f). Moreover, HBO treatment reduced IL-1β release as efficiently as edaravone and NAC (Fig. 3g), suggesting HBO attenuates microglia activation by reducing cellular ROS levels.

Since neither HBO nor the two antioxidants reversed the ROS elevation to baseline, the possibility of a synergistic effect between HBO treatment and antioxidants was considered. Surprisingly, when edaravone or NAC was administrated simultaneously with HBO, the suppressing effect of either HBO or the antioxidants on IL-1β release was reversed (Fig. 3h), suggesting that the effect of HBO depends on ROS. Indeed, HBO treatment increased the cellular ROS level in microglia (Supplementary Fig. S3), supporting this speculation.

Early HBO treatment blocked the activation of the NF-κB/NLRP3/IL-1β signaling pathway from the priming stage

Given that the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway involves two key stages, priming and activation21, we wondered which stage was affected by HBO treatment. NF-κB (p65) translocation from the cytoplasm into the nuclear and promoting transcription of target genes are major events of the priming stage. HBO treatment was observed to block the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, as demonstrated by fluorescent immunostaining, and hindered the elevation of Il1b (one of the target genes of NF-κB) mRNA, as detected by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4a–c). Additionally, HBO treatment disrupted the assembly of NLRP3-ASC inflammasome, a critical event during the activation stage, as evidenced by the reduction in ASC speck (the assembled NLRP3-ASC inflammasome) in HBO-treated microglia through ASC antibody immunostaining (Fig. 4d,e). These results indicate that HBO impedes IL-1β release from the first step of NLRP3 inflammasome signaling activation.

Fig. 4.

Early HBO treatment blocked the activation of the NF-κB/NLRP3/IL-1β signaling pathway from the priming stage. (a) Representative images of NF-κB (green) and DAPI (blue) staining in primary microglia cells. (b) The statistic of the nuclear NF-κB signal intensity in each group. Eight to ten fields of view from four cover slides per group were analyzed, and each dot in the figure represents the average signal intensity for each field of view. (c) Relative mRNA levels of Il1b in the primary microglia cells with indicated treatment (n = 3). (d) Representative images of ASC (green) and DAPI (blue) staining in primary microglia. The ASC specks were pointed with arrowheads. (e) The statistic of ASC speck positive cell ratios in the indicated groups. Nine to fourteen view fields from four cover slides in each group were analyzed, and each dot in the figure represents the average ratio for each field of view. The results are represented as mean ± s.d., *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Statistical analyses were conducted by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Consistent with the previous results, the administration of edaravone or NAC reversed the effect of HBO treatment on NF-κB translocation, Il1b mRNA elevation and ASC speck formation (Fig. 4), indicating that the HBO interrupts NLRP3 inflammasome signaling activation and IL-1β release through ROS.

Early HBO treatment attenuated HT post I/R in hyperglycemic mice through ROS

To verify the role of ROS generated by HBO treatment in vivo, the protein levels of primary components of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, including NLRP3, ASC and cleaved IL-1β, were compared through Western blotting (WB) in the hyperglycemia-enhanced HT mouse model. Consistent with the in vitro study results, NAC reversed the suppression of the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway proteins by early HBO treatment (Fig. 5a–d), except for ASC, which showed a trend although not reached statistical significance (P = 0.08), supporting that the anti-inflammatory function of early HBO treatment depends on ROS. Furthermore, NAC administration counteracted the beneficial impact of early HBO treatment in lowering the hemorrhagic score and neurological deficits scores (Fig. 5e–h), indicating that early HBO treatment attenuated HT through ROS.

Fig. 5.

Early HBO treatment attenuated HT post I/R in hyperglycemic mice through ROS. (a) Protein levels of NLRP3, ASC and cl-IL-1β in the ipsilateral striatum 24 h post-reperfusion with indicated treatments detected by western blot. β-actin was used as the endogenous control. The cropped blot images are shown, and the raw blot images can be found in the supplementary information. (b–d) Quantification of NLRP3 (b), ASC (c), and cl-IL-1β (d) protein levels detected by western blot (n = 5). (d) Representative cerebral sections to show hemorrhagic severity in mice with indicated treatments. (e) Statistical analysis of hemorrhagic scores (n = 5–10). (f and g) Statistic analysis of General (f) and Focal (g) scores (n = 6–15). The results are represented as mean ± s.d., *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Statistical analyses were conducted by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed the protective efficacy of early HBO treatment in the hyperglycemia-induced HT mouse model. HBO mitigated HT injuries partly by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pro-inflammatory response in microglia. Notably, ROS mediated the anti-inflammatory and protective role of early HBO treatment, which may provide an investigative direction for the discrepancy between preclinical and clinical studies.

Antioxidants reversed the anti-inflammation and protective role of early HBO treatment in vitro and in vivo in our study, emphasizing the importance of ROS in HBO treatment. HBO exposure induces ROS production39–42. Unlike the initial perspective that ROS are unpleasant byproducts, they have been proposed to be fundamental to HBO therapy in wound healing and mitigating post-ischemic and inflammatory injuries43. Studies have also reported that ROS mediates the beneficial role of delayed HBO therapy in promoting neurogenesis in MCAO rats44, HBO preconditioning in attenuating HT in focal cerebral ischemia rat model45, and HBO exposure in treating brain injury induced by heatstroke in rats46. All of these reports favor our conclusion that ROS mediates the protective role of early HBO administration in the HT mouse model.

The mechanism underlying the ROS function varies on the context and still requires full understanding. Activating the cellular antioxidative system to prepare the subjects for subsequent stress challenges is part of the protective efficacy of HBO preconditioning47. Indeed, HBO treatment reduced cellular ROS levels in L/N stimulated microglia in our study. However, unlike the preconditioning treatments, which are usually applied 1 day or even earlier before inducing the conditions and may be applied more than once, in our cell studies, we collected and detected primary microglia only 3 h after completing the one-time HBO treatment. The antioxidative system may not be fully activated during this period, suggesting that some other instantly responsive mechanisms may exist. In recent decades, scientists have realized that, like Ca2+, different levels of ROS play different roles. Physiological levels of ROS are essential signals that regulate the structure and activities of specific proteins through various redox modifications. ROS only cause detrimental outcomes when they exceed a threshold, usually occurring in pathological conditions48. In our study, we found that 2.5 ATA HBO treatment induced less cellular ROS than 2 μM H2O2 incubation, which is within the range of physiological fluctuation48, indicating that 2.5 ATA HBO treatment only produced a mild increase in ROS, which is likely to regulate protein functions through redox modification. The specific molecular mechanism is unclear and needs further research. Considering that the pressures of HBO treatments used in clinics are usually no more than 2.5 ATA, and micro-HBO (i.e. HBO under lower pressures like 1.3–1.5 ATA) is becoming a trend in treating some diseases nowadays, we believe that ROS is likely an essential factor mediating the beneficial effect of HBO treatment. Therefore, the use of antioxidants should be cautious during HBO therapy.

The timing to apply HBO for ischemic stroke treatment is critical, and early HBO intervention may provide better therapeutic efficacy. Although clinical trials testing early HBO treatment for patients with AIS have shown controversial results12,49, our data and other preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that HBO treatment within 12 h from the onset of ischemia significantly suppressed brain infarction, BBB damage, and improved neurological functions12–15,50. Given that the overproduction of ROS is a leading cause of pathophysiological events of I/R injuries and BBB dysfunction51, edaravone, a first-in-class medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is used to treat patients with stroke. Based on our study, using antioxidants counteracts the beneficial effect of HBO on cerebral I/R injuries, which may explain the contradiction between animal studies and clinical trials. Future studies with an inquiry into the use history of antioxidants and stratified analysis may help to conclude the effect of early HBO intervention in patients with AIS.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the specific mechanism by which HBO blocks the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway through ROS remains unclear. Secondly, we only assessed the effects of early HBO treatment at 24 h post reperfusion; the long-term effects need to be evaluated. Thirdly, we only used two antioxidants, edaravone and NAC, to investigate the role of ROS in vitro, and only NAC was tested in vivo. Whether this phenomenon is specific to these antioxidants or a universal phenomenon of all kinds of antioxidants requires further investigation. Fourthly, the specific cell type affected by HBO treatment needs clarification. We used Iba1 as a marker which cannot discriminate between microglia and macrophages, and different cell types may contribute differently to BBB damage. Additionally, a subpopulation of microglia called “vessel-associated microglia” has been proposed recently, which initially maintains BBB integrity during sustained inflammation52. Dissecting the specific cell type affected by HBO treatment will help clarify the underlying mechanisms. All of these questions require further and deeper investigation in the future and are part of our research plan.

In conclusion, our study supports the therapeutic effect of early HBO treatment for I/R injuries, provides a mechanism associated with anti-inflammation, and raises the possibility that simultaneous administration of antioxidants and HBO in patients with AIS may counteract both of their effects, which warrants attention. Considering that HBO treatment can supply oxygen with high efficiency to salvage hypoxic cells and alleviate brain damage through anti-inflammation, it kills two birds with one stone, we believe that HBO treatment as early as possible after recanalization is a promising intervention for patients with AIS.

Methods

Animals

Male ICR mice weighing 25–30 g were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Nantong University (Institutional License: SYXK(SU)-2012-0030). Mice were maintained in individually ventilated cages (IVC) with a 12-h light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water. Animal experiments in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nantong University (approval number: S20190920-303). All operations follow the institutional and/or national guidelines for the care and use of animals. The study was carried out in compliance with ARRIVE guidelines.

HT model construction

HT model was established by combining the tMCAO model with hyperglycemia. Briefly, the mice in the HT group and HT + HBO group have an injection of 50% glucose (0.12 mL/10 g body weight) via intraperitoneal 15 min before artery occlusion to induce acute hyperglycemia. The mice with a blood sugar concentration over 20 mM were included in the surgery. The murine tMCAO model was constructed as described previously53. After being anesthetized with isoflurane, the right common carotid artery, external carotid artery, and internal carotid artery of mice were exposed by incision. Following ligation at the proximal end of the common carotid artery, a 6–0 monofilament with a silicon-coated tip (Doccol) was inserted and positioned at the beginning of the middle cerebral artery to occlude it. The same surgical procedure was performed in sham group animals, except for artery occlusion. Three hours post artery occlusion, the mice were anesthetized by isoflurane again, the neck wound was reopened, and the suture was removed to restore blood flow. Body temperature was maintained between 36.5 and 37.5 °C during the procedure. We implemented the Bederson score as an inclusion criterion, only mice scoring between 2 and 3 at the initiation of reperfusion were considered successfully constructed and included in subsequent studies. Twenty-four hours post-reperfusion, after neurological behaviour tests, the mice were sacrificed and brain tissue was collected for detection.

Primary microglia culture and cell stimulation

Primary microglial cells were prepared as previously described36. The cortical hemispheres from postnatal Day 0–2 mouse pups’ brains were used, the tissues were cut into small pieces and dissociated with 0.25% trypsin. Being collected by centrifugation, cells were suspended with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin–streptomycin and 1% glutamx, then seeded onto T75 flasks and cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 7 days to allow for maturation. Subsequently, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (5 ng/mL) was added into the medium and culture for an additional 7 days. Microglia were then harvested by gently vortexing the flask for 30 min at 180 rpm in an incubated shaker (MaxQTM 4000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The detached microglial cells in the supernatant were collected by centrifugation at 1000 g for 10 min at room temperature. All culture media and reagents were purchased from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

To specifically activate the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory response in the primary cultured microglia, cells were seeded in culture media without GM-CSF to allow for resting for 24 h. Then lipopolysaccharide (Invitrogen, 100 ng/mL) was added for 3 h, followed by stimulation with nigericin (AbMole, 10 μM) for an additional 1 h.

Oxygen treatment of mice and cells

A hyperbaric chamber designed for small animal research was used for HBO treatment on mice. HBO exposure was applied as described previously54. The HT and tMCAO model mice were randomized into the control or HBO-treated group. HBO exposure (2.5 ATA, 1 h) was applied once within 1 h after reperfusion in the HBO-treated group, while mice in the control group were maintained in normal air condition.

To treat cells with oxygen under different pressures, a hyperbaric chamber designed for cell culture was used, and the treatment was applied as previously reported55. The chamber was embedded with a circulating water device to keep the environmental temperature at 37 °C. Oxygen exposure was applied under different pressures for 60 min, immediately after LPS stimulation. To maintain the pH of the cell culture medium, a proportion of carbon dioxide was added into oxygen to maintain the partial pressure of carbon dioxide at 5 kPa under corresponding pressures, and the percentage of carbon dioxide was calculated with the equation: CO2% = 5 kPa/exposed pressure (kPa)*100%.

The schematic illustrations of the treatment on animals and cells can be found in Supplementary Fig. S4.

HT and cerebral infarct area evaluation

Twenty-four hours after reperfusion, mice were deeply anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of a compound anesthetic (0.15 mL/10 g body weight, composed of 2.5% Avertin, 2,2,2-tribromoethanol, and 2-methyl-2-butanol), and perfused transcardially with heparinized saline, to clear the blood in blood vessels, then the brains were collected immediately, and the severity of HT was quantified by hemorrhage score and brain hemoglobin content. The details are as follows:

Hemorrhage score evaluation: The fresh brain was cut into 2-mm thick coronal sections on ice. Hemorrhage score ranged from 0 to 5 where 0 represents no hemorrhage while 5 represents large hematomas56 was given to each brain section. The sum of the hemorrhage scores of all the sections of the same brain was used as the hemorrhage score of the mouse.

Brain hemoglobin content measurement: The brain was dissected into the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere on ice. Each hemisphere of the brain was homogenized separately in 0.1 M PBS, followed by 30 min centrifugation (13 000 g, 4 °C). After that, 50 μL supernatant was used to measure hemoglobin content using the Hemoglobin Assay Kit (BioAssay Systems) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. To offset the individual variation derived from perfusion difference, the hemoglobin content of each mouse was calculated as hemoglobin content of the ipsilateral hemisphere minus that of the contralateral hemisphere.

Cerebral infarct area measurement: The cerebral infarct area was measured as previously described36. Briefly, the fresh brain was collected quickly, frozen at − 20 °C for 10 min, and cut into 2-mm thick coronal sections. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), all the sections were immersed in 2% 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution prepared in PBS at 307 °C for 10 min, then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight. Pictures were taken for all the sections, and the cerebral infarct area was analyzed with Fiji ImageJ software (Version 2.14.0/1.54f., NIH). The area of the contralateral hemisphere was used as a reference to correct for brain swelling, and the infarct area was calculated by subtracting the stained area in the ipsilateral hemisphere from that of the contralateral hemisphere, then the infarct area ratio was calculated, and the infarct area ratio of all the five sections was summed up to get the infarct area ratio of one mouse.

Neurological deficits evaluation

The neurological assessment was conducted double-blinded at 24 h post-reperfusion according to Clark’s scoring system57 using the general neurological scale (0–28), focal neurological scale (0–28) and Bederson neurological scale (0–3). Six and seven areas were assessed for the general scoring system and focal scoring system, respectively. Ultimately, the scores received from each area were summed to generate a total score.

Immunofluorescence staining of brain sections and image analysis

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on the 25-μm-thick frozen brain sections. The primary antibodies used are as following: anti-Iba1 (1:500, Abcam), anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2, 1:800, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-IL-1β (1:500, Santa Cruz), Laminin (1:1000, Abcam). Images were acquired by Leica TSC SP8 confocal microscope.

To quantify the activation of perivascular microglia/macrophage, circularity and ramification analysis were carried out in Iba1 positive cells using Fiji ImageJ software (Version 2.14.0/1.54f., NIH). To avoid bias, the analysis was conducted in a double-blind way. The Iba1-positive cells with any part colocalized with the blood vessel (marked by Laminin) were considered as perivascular microglia/macrophage. The intact perivascular microglia/ macrophages with no overlapping with adjacent cells in the imaging field were selected for further analysis. Ramification analysis is performed with concentric circles beginning at the edge of the soma and ending at the most extended process with a step of five pixels, and run sholl analysis in Fiji to calculate the number of intersections between cell branches and concentric circles. The total number of intersections is recorded as Ramifications. The higher the degree of activation, the less of the ramification number. Cell circularity ranging from 0 to 1, represents the cell shape with the function of 4πAcell/Pcell2 (A: cell area, P: cell perimeter), with 0 representing an imperfect shape (ramified) while 1 representing a perfect circle (amoeboid)58.

Cell immunofluorescence staining and analysis

Cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and blocked in 10% bovine serum albumin for 1 h before being labeled with p65 (NF-κB) antibody (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology) or ASC (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies. Then, cells were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescent dyes for 2 h at room temperature and protected from light. Images were captured by Leica TSC SP8 confocal microscope. FIJI ImageJ software (Version 2.14.0/1.54f., NIH) was used for image analysis. For p65 nuclear translocation analysis, the nuclei areas were framed by the software, then the p65 fluorescence signal intensity in nuclei was calculated. For ASC speck (the assembled inflammasome) analysis, the total cell number and the ASC speck-positive cells were labeled and counted, then the percentages of ASC speck-positive cells were calculated.

Cell viability and LDH leakage assay

The cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo) and the cytotoxicity was measured using the LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Beyotime) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance value (OD) of the samples was read using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek). The OD of each experimental group was compared with that of the control group to calculate the relative cell viability. The LDH leakage was calculated with the equation: LDH leakage% = (ODexperimental−ODblank)/(ODcontrol−ODblank)*100%.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The cell culture media were collected to measure the released IL-1β. The IL-1β concentrations were measured using the Mouse IL-1β ELISA kit (Multisciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance value of the samples was read using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek). The concentrations were calculated from the calibrated standard curve.

Real-time qPCR analysis

Total RNAs were isolated from cell or tissue samples with TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA (1 µg) was converted to cDNA with HiScript II RT SuperMix (+ gDNA wiper) (Cat#R323-01, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd). qPCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd) with a StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The housekeeping gene Actb was used as an endogenous control to normalize the gene expression level. The primer sequences are as follows: Mouse Il1b Forward: 5′-TCCAGGATGAGGACATGAGCAC-3′; Mouse Il1b Reverse: 5′-GAACGTCACACACCAGCAGGTTA-3′; Mouse Tnfa-Forward: 5′-GTTCTATGGCCCAGACCCTCAC-3′; Mouse Tnfa-Reverse: 5′-GGCACCACTAGTTGGT TGTCTTTG-3′; Mouse Il6-Forward: 5′-CACGGCCTTCCCTACTTCAC-3′; Mouse Il6-Reverse: 5′-TGCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGT-3′; Mouse Nos2-Forward: 5′-CCCTTCCGAA GTTTCTGGCAGCAGC-3′; Mouse Nos2-Reverse: 5′-CCAAAGCCACGAGGCTCTGACA GCC-3′; Mouse Actb Forward: 5′- ACACCCGCCACCAGTTC-3′; Mouse Actb Reverse: TACAGCCCGGGGAGCAT.

Western blot analysis

Protein samples were obtained from mice brain tissues lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. Primary antibodies targeting ZO-1 (1:1000, Proteintech), NLRP3 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), ASC (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), IL-1β (1:500, Affinity Biosciences), and β-actin (1:10000, Cell Signaling Technology) were used. Signals were detected using an ECL detection system with Tanon 5200 Multi imaging system. The bands were quantified by densitometry analysis using the Fiji ImageJ software (Version 2.14.0/1.54f., NIH).

Antioxidant administration in animals and cells

For animal, N-Acetyl-l-Cysteine (NAC) (Hangzhou Minsheng Pharmaceutical, 400 mg/kg) were injected via intraperitoneal 30 min before monofilament removal and reperfusion. For cells, edaravone (100 μM) and NAC (1 mM) were added to the cell medium right before HBO treatment.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± s.d.). Statistical analyses were performed by the Prism software (version 9, Graphpad). The normal distribution of the data was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed data, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used. For data that didn’t fit normal distribution, the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was adopted to compare multiple groups. The mean value or rank of each group was compared with the mean value or rank of every other group. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the China Scholarship Council, and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Nantong Municipality (MS22022058, JCZ21107).

Author contributions

Y.Y. and X.L. designed the study, supervised the work, interpreted the data, wrote the manuscript, revised it, and finally approved it. Y.G., J.L., X.D., M.Q., T.S., K.X. and X.W. were involved in the experimental conception, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data. Y.G., J.L. and X.D. also prepared the draft. Z.J., Y.L. and Y.Z. helped with the interpretation of data and the design of the study. L.X. and B.P. helped with in vivo and in vitro model build-up. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yanan Guo and Jiayi Liu.

Contributor Information

Xia Li, Email: lixia7979@ntu.edu.cn.

Yuan Yuan, Email: yuanyuan2017@ntu.edu.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-72454-4.

References

- 1.Lindsay, M. P. et al. World stroke organization (WSO): Global stroke fact sheet 2019. Int. J. Stroke14, 806–817. 10.1177/1747493019881353 (2019). 10.1177/1747493019881353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jickling, G. C. et al. Hemorrhagic transformation after ischemic stroke in animals and humans. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.34, 185–199. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.203 (2014). 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, X. et al. Mechanisms of hemorrhagic transformation after tissue plasminogen activator reperfusion therapy for ischemic stroke. Stroke35, 2726–2730. 10.1161/01.STR.0000143219.16695.af (2004). 10.1161/01.STR.0000143219.16695.af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari, F., Moretti, A. & Villa, R. F. Hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: Physiopathological and therapeutic complexity. Neural Regen. Res.17, 292–299. 10.4103/1673-5374.317959 (2022). 10.4103/1673-5374.317959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desilles, J. P. et al. Exacerbation of thromboinflammation by hyperglycemia precipitates cerebral infarct growth and hemorrhagic transformation. Stroke48, 1932–1940. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017080 (2017). 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong, J. M., Kim, D. S. & Kim, M. Hemorrhagic transformation after ischemic stroke: Mechanisms and management. Front. Neurol.12, 703258. 10.3389/fneur.2021.703258 (2021). 10.3389/fneur.2021.703258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Kranendonk, K. R. et al. Hemorrhagic transformation is associated with poor functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to a large vessel occlusion. J. Neurointerv. Surg.11, 464–468. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014141 (2019). 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choudhury, R. Hypoxia and hyperbaric oxygen therapy: A review. Int. J. Gen. Med.11, 431–442. 10.2147/IJGM.S172460 (2018). 10.2147/IJGM.S172460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen, S. & Sen, S. Therapeutic effects of hyperbaric oxygen: Integrated review. Med. Gas Res.11, 30–33. 10.4103/2045-9912.310057 (2021). 10.4103/2045-9912.310057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cozene, B. et al. An extra breath of fresh air: Hyperbaric oxygenation as a stroke therapeutic. Biomolecules10, 1279. 10.3390/biom10091279 (2020). 10.3390/biom10091279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottfried, I., Schottlender, N. & Ashery, U. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment-from mechanisms to cognitive improvement. Biomolecules11, 1520. 10.3390/biom11101520 (2021). 10.3390/biom11101520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan, Y. et al. The application and perspective of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in acute ischemic stroke: From the bench to a starter?. Front. Neurol.13, 928802. 10.3389/fneur.2022.928802 (2022). 10.3389/fneur.2022.928802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiankhaw, K., Chattipakorn, N. & Chattipakorn, S. C. The effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on the brain with middle cerebral artery occlusion. J. Cell Physiol.236, 1677–1694. 10.1002/jcp.29955 (2021). 10.1002/jcp.29955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, Q. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen reduces infarction volume and hemorrhagic transformation through ATP/NAD(+)/Sirt1 pathway in hyperglycemic middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Stroke48, 1655–1664. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015753 (2017). 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin, Z. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen-induced attenuation of hemorrhagic transformation after experimental focal transient cerebral ischemia. Stroke38, 1362–1367. 10.1161/01.STR.0000259660.62865.eb (2007). 10.1161/01.STR.0000259660.62865.eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang, R. et al. The dual role of microglia in blood-brain barrier dysfunction after stroke. Curr. Neuropharmacol.18, 1237–1249. 10.2174/1570159X18666200529150907 (2020). 10.2174/1570159X18666200529150907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu, Y. M. et al. Immune cells in the BBB disruption after acute ischemic stroke: Targets for immune therapy?. Front. Immunol.12, 678744. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.678744 (2021). 10.3389/fimmu.2021.678744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronaldson, P. T. & Davis, T. P. Regulation of blood-brain barrier integrity by microglia in health and disease: A therapeutic opportunity. J Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.40, S6–S24. 10.1177/0271678X20951995 (2020). 10.1177/0271678X20951995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alishahi, M. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome in ischemic stroke: As possible therapeutic target. Int. J. Stroke14, 574–591. 10.1177/1747493019841242 (2019). 10.1177/1747493019841242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng, Y. S. et al. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome: A prospective target for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Front. Cell Neurosci.14, 155. 10.3389/fncel.2020.00155 (2020). 10.3389/fncel.2020.00155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanson, K. V., Deng, M. & Ting, J. P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol.19, 477–489. 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0 (2019). 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, L. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: A therapeutic target for cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front. Mol. Neurosci.15, 847440. 10.3389/fnmol.2022.847440 (2022). 10.3389/fnmol.2022.847440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang, F. et al. NLRP3 deficiency ameliorates neurovascular damage in experimental ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.34, 660–667. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.242 (2014). 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo, Z. et al. Suppression of NLRP3 attenuates hemorrhagic transformation after delayed rtPA treatment in thromboembolic stroke rats: Involvement of neutrophil recruitment. Brain Res. Bull.137, 229–240. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.12.009 (2018). 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward, R. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition with MCC950 improves diabetes-mediated cognitive impairment and vasoneuronal remodeling after ischemia. Pharmacol. Res.142, 237–250. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.01.035 (2019). 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellut, M. et al. NLPR3 inflammasome inhibition alleviates hypoxic endothelial cell death in vitro and protects blood-brain barrier integrity in murine stroke. Cell Death Dis.13, 20. 10.1038/s41419-021-04379-z (2021). 10.1038/s41419-021-04379-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palomino-Antolin, A. et al. Time-dependent dual effect of NLRP3 inflammasome in brain ischaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol.179, 1395–1410. 10.1111/bph.15732 (2022). 10.1111/bph.15732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim, S. W. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen effects on depression-like behavior and neuroinflammation in traumatic brain injury rats. World Neurosurg.100, 128–137. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.12.118 (2017). 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.12.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim, S. W. et al. Microglial activation induced by traumatic brain injury is suppressed by postinjury treatment with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J. Surg. Res.184, 1076–1084. 10.1016/j.jss.2013.04.070 (2013). 10.1016/j.jss.2013.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang, F. et al. Effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on polarization phenotype of rat microglia after traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol.12, 640816. 10.3389/fneur.2021.640816 (2021). 10.3389/fneur.2021.640816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapira, R., Solomon, B., Efrati, S., Frenkel, D. & Ashery, U. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy ameliorates pathophysiology of 3xTg-AD mouse model by attenuating neuroinflammation. Neurobiol. Aging62, 105–119. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.10.007 (2018). 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunther, A. et al. Reduced infarct volume and differential effects on glial cell activation after hyperbaric oxygen treatment in rat permanent focal cerebral ischaemia. Eur. J. Neurosci.21, 3189–3194. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04151.x (2005). 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04151.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunshine, M. D. et al. Oxygen therapy attenuates neuroinflammation after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflam.20, 303. 10.1186/s12974-023-02985-6 (2023). 10.1186/s12974-023-02985-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian, H., Li, Q. & Shi, W. Hyperbaric oxygen alleviates the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in traumatic brain injury. Mol. Med. Rep.16, 3922–3928. 10.3892/mmr.2017.7079 (2017). 10.3892/mmr.2017.7079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi, Y. et al. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the brain after carbon monoxide poisoning. Undersea Hyperb. Med.47, 607–619. 10.22462/10.12.2020.10 (2020). 10.22462/10.12.2020.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue, K. et al. Argon mitigates post-stroke neuroinflammation by regulating M1/M2 polarization and inhibiting NF-kappaB/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. J. Mol. Cell Biol.14, mjac077. 10.1093/jmcb/mjac077 (2023). 10.1093/jmcb/mjac077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson, D. S. A. & Oliver, P. L. ROS generation in Microglia: Understanding oxidative stress and inflammation in neurodegenerative disease. Antioxidants (Basel)9, 743. 10.3390/antiox9080743 (2020). 10.3390/antiox9080743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orellana-Urzua, S., Rojas, I., Libano, L. & Rodrigo, R. Pathophysiology of ischemic stroke: Role of oxidative stress. Curr. Pharm. Des.26, 4246–4260. 10.2174/1381612826666200708133912 (2020). 10.2174/1381612826666200708133912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pesce, J. T. et al. Arginase-1–expressing macrophages suppress Th2 cytokine-driven inflammation and fibrosis. PLOS Pathogens5, e1000371. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000371 (2009). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camporesi, E. M. & Bosco, G. Mechanisms of action of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Undersea Hyperb. Med.41, 247–252 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou, Q., Huang, G., Yu, X. & Xu, W. A novel approach to estimate ROS origination by hyperbaric oxygen exposure, targeted probes and specific inhibitors. Cell Physiol. Biochem.47, 1800–1808. 10.1159/000491061 (2018). 10.1159/000491061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Wolde, S. D., Hulskes, R. H., Weenink, R. P., Hollmann, M. W. & Van Hulst, R. A. The effects of hyperbaric oxygenation on oxidative stress, inflammation and angiogenesis. Biomolecules11(8), 1210. 10.3390/biom11081210 (2021). 10.3390/biom11081210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thom, S. R. Oxidative stress is fundamental to hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J. Appl. Physiol.1985(106), 988–995. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91004.2008 (2009). 10.1152/japplphysiol.91004.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu, Q. et al. Delayed hyperbaric oxygen therapy promotes neurogenesis through reactive oxygen species/hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha/beta-catenin pathway in middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Stroke45, 1807–1814. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005116 (2014). 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soejima, Y. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning attenuates hyperglycemia-enhanced hemorrhagic transformation by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases in focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Exp. Neurol.247, 737–743. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.03.019 (2013). 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni, X. X. et al. Protective effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on brain injury by regulating the phosphorylation of Drp1 through ROS/PKC pathway in heatstroke rats. Cell Mol. Neurobiol.40, 1253–1269. 10.1007/s10571-020-00811-8 (2020). 10.1007/s10571-020-00811-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, X. et al. An overview of hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning against ischemic stroke. Metab. Brain Dis.38, 855–872. 10.1007/s11011-023-01165-y (2023). 10.1007/s11011-023-01165-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sies, H. & Jones, D. P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.21, 363–383. 10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3 (2020). 10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bennett, M. H. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.10.1002/14651858.CD004954.pub3 (2014). 10.1002/14651858.CD004954.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veltkamp, R. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen reduces blood-brain barrier damage and edema after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke36, 1679–1683. 10.1161/01.STR.0000173408.94728.79 (2005). 10.1161/01.STR.0000173408.94728.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng, D. et al. ROS-triggered endothelial cell death mechanisms: Focus on pyroptosis, parthanatos, and ferroptosis. Front. Immunol.13, 1039241. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1039241 (2022). 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1039241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haruwaka, K. et al. Dual microglia effects on blood brain barrier permeability induced by systemic inflammation. Nat. Commun.10, 5816. 10.1038/s41467-019-13812-z (2019). 10.1038/s41467-019-13812-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu, X. et al. Ultrastructural studies of the neurovascular unit reveal enhanced endothelial transcytosis in hyperglycemia-enhanced hemorrhagic transformation after stroke. CNS Neurosci. Therapeut.27, 123–133. 10.1111/cns.13571 (2021). 10.1111/cns.13571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan, Y. et al. Deconvolution of RNA-seq analysis of hyperbaric oxygen-treated mice lungs reveals mesenchymal cell subtype changes. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 1371. 10.3390/ijms21041371 (2020). 10.3390/ijms21041371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan, Y. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Front. Mol. Biosci.8, 675437. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.675437 (2021). 10.3389/fmolb.2021.675437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salas-Perdomo, A. et al. T cells prevent hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke by P-selectin binding. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.38, 1761–1771. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311284 (2018). 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark, W. M., Lessov, N. S., Dixon, M. P. & Eckenstein, F. Monofilament intraluminal middle cerebral artery occlusion in the mouse. Neurol. Res.19, 641–648. 10.1080/01616412.1997.11740874 (1997). 10.1080/01616412.1997.11740874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leyh, J. et al. Classification of microglial morphological phenotypes using machine learning. Front. Cell Neurosci.15, 701673. 10.3389/fncel.2021.701673 (2021). 10.3389/fncel.2021.701673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.