Abstract

Molecular imaging holds the potential for noninvasive and accurate grading of liver fibrosis. It is limited by the lack of biomarkers that strongly correlate with liver fibrosis grade. Here, we discover the grading potential of fibroblast activation protein alpha (FAPα) for liver fibrosis through transcriptional analysis and biological assays on clinical liver samples. The protein and mRNA expression of FAPα are linearly correlated with fibrosis grade (R2 = 0.89 and 0.91, respectively). A FAPα-responsive MRI molecular nanoprobe is prepared for quantitatively grading liver fibrosis. The nanoprobe is composed of superparamagnetic amorphous iron nanoparticles (AFeNPs) and paramagnetic gadoteric acid (Gd-DOTA) connected by FAPα-responsive peptide chains (ASGPAGPA). As liver fibrosis worsens, the increased FAPα cut off more ASGPAGPA, restoring a higher T1-MRI signal of Gd-DOTA. Otherwise, the signal remains quenched due to the distance-dependent magnetic resonance tuning (MRET) effect between AFeNPs and Gd-DOTA. The nanoprobe identifies F1, F2, F3, and F4 fibrosis, with area under the curve of 99.8%, 66.7%, 70.4%, and 96.3% in patients’ samples, respectively. This strategy exhibits potential in utilizing molecular imaging for the early detection and grading of liver fibrosis in the clinic.

Subject terms: Biomaterials, Magnetic resonance imaging, Biomaterials

Molecular imaging holds promise for liver fibrosis grading but limited by a lack of effective biomarker. Here, the authors discover the grading potential of fibroblast activation protein alpha and design a responsive MRI nanoprobe that achieves fibrosis grading in mice models and clinical samples.

Introduction

The degree of liver fibrosis strongly influences the progression and malignant transformation of various chronic liver diseases1,2. Clinical studies have demonstrated a threefold increase in all-cause and liver-related mortality in patients with chronic liver diseases3. Puncture biopsy is the gold standard for the clinical diagnosis of liver fibrosis4,5. But it is limited by its severe invasiveness and restricted sampling volume. Currently, commonly used noninvasive liver fibrosis evaluation methods include serology and medical imaging. Multiple serologic markers-based diagnostic models can provide diagnostic reference6,7. However, it is weak for the diagnosis of mild fibrosis as well as non-viral hepatitis background fibrosis8,9. Ultrasound elastography and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) are emerging functional imaging methods that quantify alterations in the mechanical properties (elasticity or stiffness) of the liver due to liver fibrosis10. Nevertheless, numerous pathologic factors (e.g., portal hypertension, acute inflammation, and right heart failure) can also lead to increased liver stiffness, interfering with its diagnostic accuracy11. Molecular imaging offers the unique advantages of noninvasive deep tissue penetration and comprehensive liver coverage12,13, making it ideal for monitoring fibrosis progression and regression14. Unfortunately, there are few biomarkers strongly associated with the grade of liver fibrosis, rendering existing molecular imaging methods inadequate to quantify liver fibrosis15.

Existing diagnostic markers for liver fibrosis (such as α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), hyaluronic acid, and collagen) are not tightly correlated with liver fibrosis grade because of their poor connection with the activation of hepatic stellate cells16–18. Through transcriptome analysis and extensive biological experiments on clinical liver samples, we found that fibroblast activation protein alpha (FAPα), a biomarker originating from hepatic stellate cells, had the optimal correlation with the grade of liver fibrosis. Our results demonstrated a significant linear correlation between the amount of FAPα protein or the relative mRNA expression level of FAPα and the fibrosis grade in clinical liver fibrosis samples (R2 = 0.89 and 0.91, respectively) (See below). This finding demonstrated that FAPα had the potential to grade liver fibrosis. It would be highly valuable to develop an effective molecular imaging probe capable of quantitatively detecting FAPα to achieve the noninvasive grading of liver fibrosis.

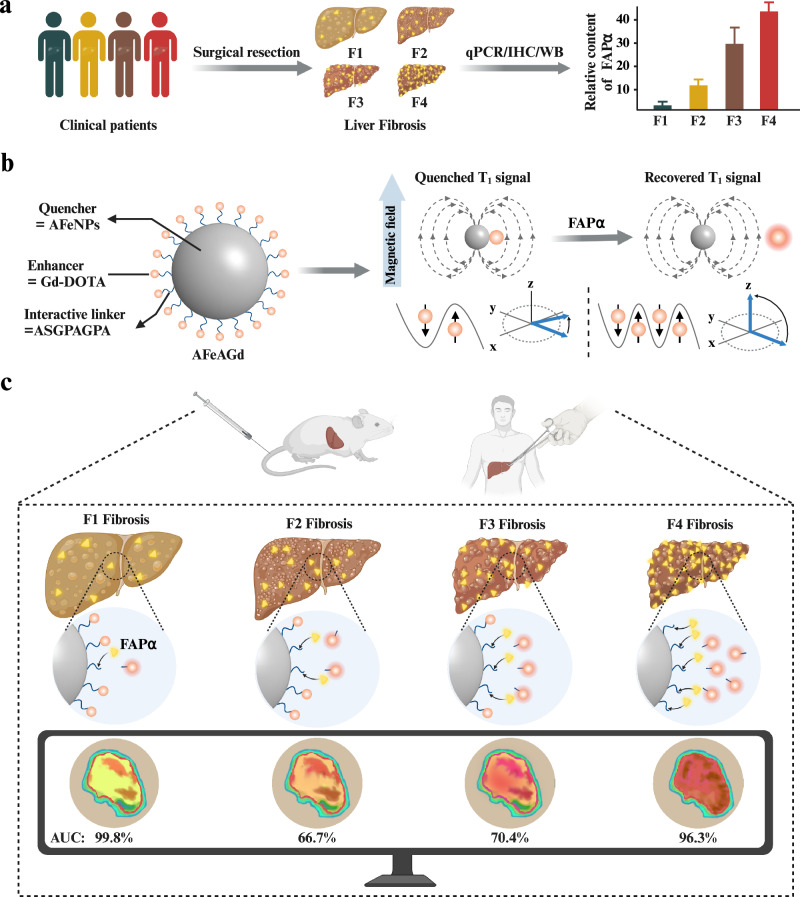

Here, we developed a novel nanoprobe based on the distance-dependent magnetic resonance tuning (MRET) effect19,20 for the sensitive and quantitative MRI detection of FAPα, further facilitating the precise grading of liver fibrosis in the clinic (Fig. 1). Specifically, the nanoprobe (AFeAGd) consisted of amorphous iron nanoparticles (AFeNPs) and the clinical T1-MRI contrast agent gadoteric acid (Gd-DOTA), which were linked via FAPα-responsive peptide chains (ASGPAGPA). Initially, the T1-MRI signals of AFeAGd were turned “off” due to the strong magnetic field of AFe impeding the relaxation of Gd-DOTA. Upon interaction with FAPα, which was progressively upregulated as fibrosis grade increased, the electron spin of Gd gradually recovered, and the T1-MRI signals turned “on”. The varying degrees of T1-MRI signals were based on the increased amount of the peptide chain cut by FAPα21. These distinctive signals from AFeAGd amplified the relaxation differences between various grades of liver fibrosis. Area under the curve (AUC) analysis demonstrated that AFeAGd achieved a satisfactory diagnostic result for F1, F2, F3, and F4 fibrosis, with AUC values of 99.8%, 66.7%, 70.4%, and 96.3% in liver fibrosis patients’ samples. Compared to the MRI scans without the nanoprobe, the diagnostic accuracy for each fibrosis grade was improved by 25.9%, 14.8%, 7.4%, and 23.6%, respectively. This study offers a promising strategy to address the clinical need for noninvasive quantitative diagnosis of liver fibrosis grading.

Fig. 1. A FAPα-activated MRI nanoprobe for precise grading diagnosis of clinical liver fibrosis.

a Screening and identification of FAPα as a pathological biomarker for liver fibrosis grading through abundant biological validation on liver fibrosis samples from clinical patients. b Schematic illustration of the construction of AFeAGd nanoprobe. Superparamagnetic quencher (AFeNPs) was connected to paramagnetic enhancer (Gd-DOTA) via a FAPα-responsive linker (ASGPAGPA). AFeAGd nanoprobe based on the MRET effect exhibited an “off/on” T1 MRI signal. c AFeAGd nanoprobe successfully achieved sensitive diagnosis of different fibrosis grades in mice models and clinical patients’ liver fibrosis samples. The area under the curve for identifying F1, F2, F3, and F4 fibrosis, were 99.8%, 66.7%, 70.4%, and 96.3% in patients’ liver samples, respectively. Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.

Results

Screening and identification of FAPα as a pathological biomarker for liver fibrosis grading

First, we performed differential gene expression analysis between the patients with mild fibrosis (F1-F2, n = 102) and those with severe fibrosis (F3-F4, n = 68) in the GSE-135251 dataset (Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, the major gene heatmap analysis and the Wilcoxon test highlighted a significant difference in FAPα expression between the two groups (Fig. 2a). More importantly, we found significant differences in FAPα expression between each liver fibrosis grade, suggesting that FAPα possesses the potential to be used as a grading biomarker for liver fibrosis (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, we also revealed in two other independent public datasets (including GSE-193066 and GSE-193080) that FAPα expression was significantly higher in patients with severe liver fibrosis than in patients with mild liver fibrosis (Supplementary Fig. 3). We also conducted an RNA-sequencing analysis on our center’s clinical liver samples (n = 6) with different liver fibrosis grades. Through differentially expressed gene analysis, we identified that the genes were highly expressed in the fibrotic liver (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5). Notably, we again found a significant enrichment of FAPα in the fibrotic livers of this cohort (Fig. 2c).

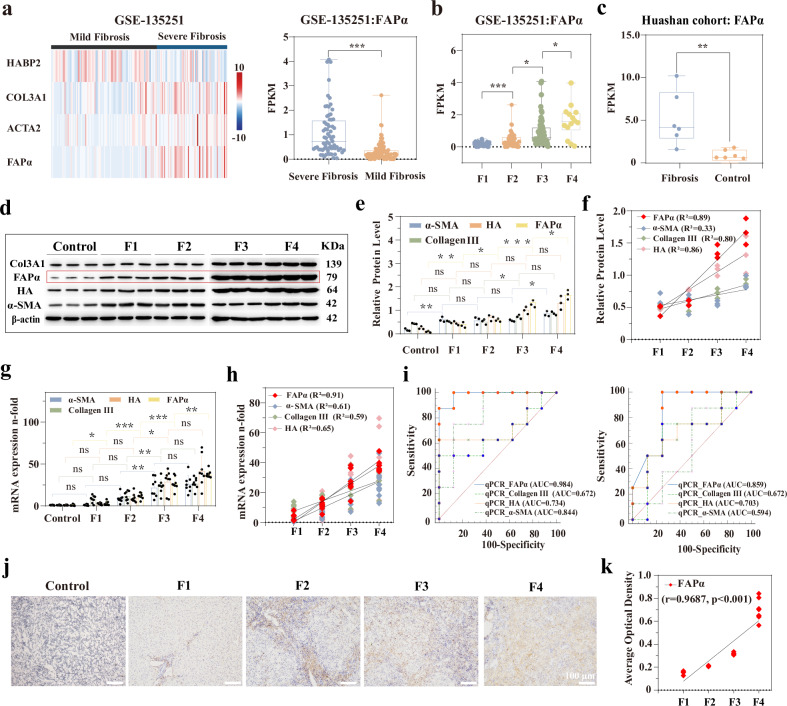

Fig. 2. Screening and identification of FAPα as a pathological marker for the grading diagnosis of liver fibrosis.

a Heat map of the distribution of FAPα and several common fibrosis markers in the mild and severe fibrosis cohorts of GSE-135251 dataset (Left), box plot of FAPα expression in the mild (n = 102) and severe (n = 68) fibrosis cohorts (Right) (Box plots are defined as minima, maxima, centre, bounds of box and 25– 75% percentile, p = 3.90 × 10−6). b Box plot of FAPα expression between each liver fibrosis grade in GSE-135251 dataset (F1: n = 48, F2: n = 54, F3: n = 54, F4: n = 14. Box plots are defined as minima, maxima, centre, bounds of box and 25–75% percentile. p = 2.70 × 10−5, p = 0.0200, p = 0.0213, from left to right, respectively). c Expression of FAPα in the control and fibrosis cohorts of the Huashan Hospital population (n = 6 biological replications. Box plots are defined as minima, maxima, centre, bounds of box and 25–75% percentile, p = 0.0081). d Western blot of several typical pathological markers of liver fibrosis (including α-SMA, collagen III, HA) and FAPα (n = 3 biological replications. The samples derive from the same experiment and that gels/blots were processed in parallel). e Quantitative histograms of WB bands (n = 3 biological replications, data are described as mean+ SD). f Scatter plots for linear correlation analysis between relative protein level and fibrosis grade (n = 3). g, qPCR expression histograms of several pathological markers of liver fibrosis in fibrotic and normal livers (n = 8 biological replications, data are described as mean+ SD, the exact p value in Fig. 2e, g are shown in the Source data file). h Scatter plots of linear correlation analysis between fibrosis grade and qPCR quantification of each biomarker (n = 8). i ROC curves of qPCR quantification of each diagnostic marker in two fibrosis diagnostic scenarios. Left, ROC curves for low-grade fibrotic liver versus high-grade fibrosis (F3, F4). Right, normal liver versus low-grade fibrosis (F1, F2) (n = 8). j Immunohistochemical staining of FAPα in fibrotic and normal liver (n = 8). k Scatter plots for linear correlation analysis between fibrosis grade and IHC quantification of FAPα (n = 8 biological replications, p = 9.02 × 10−4). (Comparisons of continuous variables between two groups were made using student’s t-test. Three and more groups comparisons were made using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s post hoc test. Two-tailed tests are applicable to all statistical analyses. ns for not significant, * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001).

Subsequently, the liver samples from 40 clinical patients were stained by hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome to confirm their pathological grades of liver fibrosis (Supplementary Fig. 6). Western blotting showed a marked difference in FAPα protein expression than in the other markers (including α-SMA, collagen III, and hyaluronic acid (HA)), with an optimal correlation coefficient of 0.89 (Fig. 2d–f). This correlation was further confirmed by the results of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), which displayed a superior quantitative linear correlation between FAPα and liver fibrosis grade (R2 = 0.91) (Fig. 2g, h). More importantly, ROC curves for the transcript level of FAPα demonstrated its superior diagnostic performance, with AUC of 85.9% (normal control versus F1 + F2) and 98.4% (F1 + F2 versus F3 + F4) (Fig. 2i). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis also revealed that FAPα had the optimal correlation with the grade of liver fibrosis (Fig. 2j, k and Supplementary Figs. 7–9). Similarly, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrated that FAPα outperformed other conventional markers in grading liver fibrosis (Supplementary Fig. 10), with AUC of 82.5% (normal control versus F1 + F2) and 87.5% (F1 + F2 versus F3 + F4). In addition, we analyzed the correlation between the patients’ FAPα expression levels (including transcript, protein, and immunohistochemistry level) and the MASSON-stained liver fibrosis positive area to better demonstrate the correlation between FAPα and liver fibrosis grading (Supplementary Fig. 11). The results showed a positive correlation between FAPα expression at different levels and the positive area of liver fibrosis (r > 0.90, p < 0.001). These findings indicated a close relationship between the expression level of FAPα and the grade of liver fibrosis.

In contrast, four liver fibrosis items and two serological fibrosis diagnostic scores (APRI and FIB-4), as control markers, did not adequately reflect the fibrosis grade (Supplementary Figs. 12, 13). This was attributed to the complex therapeutic background of the patients’ liver disease and the instability of their hematological markers. Overall, these results highlighted the potential of FAPα as a biomarker for grading liver fibrosis.

Design and synthesis of the FAPα-responsive molecular MRI nanoprobe

For the noninvasive grading of liver fibrosis, we designed a FAPα-responsive molecular MRI nanoprobe based on the MRET effect22–24. The nanoprobe had two key components (Fig. 3a), a superparamagnetic quencher (Amorphous iron nanoparticles (AFeNPs)) and a paramagnetic enhancer (Gd-DOTA). The two were connected by a FAPα-responsive Ala-Ser-Gly-Pro-Ala-Gly-Pro-Ala polypeptide (ASGPAGPA), which could be specifically recognized by FAPα and triggered a nucleophilic reaction with the carbon atom on the peptide chain to cleave the prolyl peptide bonds through a hydrolysis reaction25,26. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Fig. 3b) showed that AFeNPs had a uniform morphology with an approximate diameter of 12.0 nm, which was consistent with the hydrodynamic diameter in Supplementary Fig. 14. As shown in Fig. 3c, the element arrangement of AFeNPs maintained a random distribution, indicating its amorphous feature. The amorphous feature was further confirmed by the local fast Fourier transform (Fig. 3d, e). The characteristic diffuse halo in the selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern (Supplementary Fig. 15) also verified the amorphous character of AFeNPs. AFeNPs were then coupled with Gd-DOTA through the FAPα-responsive peptide ASGPAGPA, yielding the FAPα-responsive molecular MRI nanoprobe (AFeAGd).

Fig. 3. Synthesis and characterization of the FAPα-responsive molecular MRI nanoprobe.

a The two units of the molecular MRET nanoprobe: an enhancer (Gd-DOTA) and a quencher (12 nm superparamagnetic nanoparticles). b, c TEM and HRTEM images of AFeNPs (each experiment was repeated 3 times independently with similarly results). d, e FFT images of local regions marked in (c). f XRD of AFeNPs and AFeAGd. g Zeta potential of AFeNPs, AFe-ASGPAGPA, and AFeAGd (data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3, independent experiments). h FT-IR of AFeNPs, AFe-ASGPAGPA, and AFeAGd. i TGA curves of AFeNPs, AFe-ASGPAGPA, and AFeAGd. j Relative contents of Fe and Gd in AFeAGd (data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3, independent experiments). k Field-dependent magnetization curves of AFeNPs, AFe-ASGPAGPA and AFeAGd. l COMSOL finite element simulation of the induced magnetic field distribution of AFeNPs and Gd-DOTA at different distances (d = 2, 7, 12 nm).

Compared with iron nanocrystals (FeNCs) (Supplementary Fig. 16), both AFeNPs and AFeAGd exhibited a glassy nature, from their X-ray diffraction peak (Fig. 3f). As shown in Fig. 3g, the changes of Zeta potentials of AFe-ASGPAGPA and AFeAGd indicated the successful synthesis of AFe-ASGPAGPA and AFeAGd. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were tested to study the surface modification of ASGPAGPA and Gd-DOTA on AFeNPs. As shown in Fig. 3h, compared with AFeNPs, AFe-ASGPAGPA and AFeAGd appeared new peaks at 1650 cm−1 and 1723 cm−1, indicating successful synthesis of AFe-ASGPAGPA and AFeAGd. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA)curves also demonstrated the successful synthesis of AFe-ASGPAGPA and AFeAGd (Fig. 3i). The relative contents of Gd and Fe were 79.48% and 20.52% in AFeAGd, respectively (Fig. 3j). In addition, the field-dependent magnetization (M-H) study showed that AFeNPs (49.71 emu/g) possessed higher magnetic moments than AFe-ASGPAGPA (37.74 emu/g) and AFeAGd (11.02 emu/g) (Fig. 3k). The difference not only demonstrated the successful synthesis of AFeAGd but also illustrated the magnetic influence between Gd-DOTA and AFeNPs. Furthermore, a COMSOL finite element simulation was conducted to indicate the distance-dependent magnetic resonance tuning effect. Before AFeAGd responded to FAPα, AFe, and Gd-DOTA were relatively close. The magnetic induction line of Gd-DOTA exhibited an asymmetric distribution (Supplementary Figs. 17, 18). It was primarily due to the strong magnetic field coupling Gd-DOTA, effectively suppressing the spin fluctuation of Gd-DOTA. After cleavage of ASGPAGPA by FAPα, the distance between them gradually increased. Consequently, the magnetic induction line of Gd-DOTA displayed a symmetric distribution. The magnetic coupling of Gd-DOTA progressively weakened, further reinstating the rapid spin fluctuation of Gd-DOTA (Fig. 3l).

In vitro MRI relaxation performance of AFeAGd

Magnetic coupling changed the T1 imaging properties of AFeAGd. When AFe and Gd-DOTA were close, the electron spin fluctuation of Gd-DOTA slowed. As a result, the relaxation of water protons became ineffective, leading to a low T1-MRI signal (“off” state). In contrast, AFe and Gd-DOTA were separated after AFeAGd encountered FAPα, which accelerated the electron spin fluctuation of Gd-DOTA27. This promoted water proton relaxation and restored the T1-MRI signal of Gd-DOTA (“on” state). Therefore, we used the change in the T1-MRI signal to quantitatively assess the amount of FAPα.

We successfully used AFeAGd to detect FAPα with a 3.0 T MRI scanner. In Fig. 4a–c, Gd-DOTA exhibited effective T1-MRI contrast performance (r1 = 6.51 mM−1s−1), while AFeNPs showed limited longitudinal relaxation rate (r1 = 0.49 mM−1s−1). Similarly, the T1 relaxation property of AFeAGd remained limited (r1 = 0.53 mM−1s−1) due to the intense magnetic-field confinement of Gd-DOTA exerted by AFe. When FAPα was presented (1000 ng/mL), the T1-MRI contrast performance of AFeAGd turned out to be 16.01 mM−1s−1. The T1 relaxation time of AFeAGd (0.05 mM) changed from 1814.70 ms to 752.80 ms in response to FAPα. Interestingly, after responding to high-concentration FAPα, AFeAGd exhibited an even higher r1 performance than Gd-DOTA (Fig. 4d). We speculated that the binding of Gd-DOTA to the peptide ASGPAGPA increased the molecular weight of Gd-DOTA, which in turn increased the rotation time (τR). This significantly enhanced the inner spherical water relaxation of Gd-DOTA, according to the Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan (SBM) theory28. We further confirmed this theory by measuring the T1 imaging capability of ASGPAGPA-Gd alone, which had a significantly higher r1 of 17.03 mM−1s−1 than Gd-DOTA (Supplementary Fig. 19). We also prepared a scrambled version of a control nanoprobe. The AFe-AGPGPSAA-Gd was identical to the constructed AFeAGd except for the middle peptide sequence. The results showed that no significant T1-MRI enhancement was demonstrated in the control nanoprobe before or after the co-incubation of FAPα (Supplementary Fig. 20). It indicated the specificity of AFeAGd nanoprobe to FAPα.

Fig. 4. In vitro FAPα-responsive imaging performance of AFeAGd nanoprobes.

a Original T1WI images of Gd-DOTA, AFe, AFeAGd, and AFeAGd mixed with FAPα (0.015–0.05 mM of the above three probes is indicated as the Gd concentration, while the concentration label in AFe represents Fe concentration). b Corresponding pseudocolor map of Gd-DOTA, AFe, AFeAGd, and AFeAGd mixed with FAPα. c r1 from T1WI scans of Gd-DOTA, AFe, AFeAGd, and AFeAGd mixed with FAPα. d Histogram of r1 for AFe, AFeAGd, Gd-DOTA and AFeAGd+FAPα (1000 ng/mL). (n = 3 sample replications for each group, data are expressed as mean+SD. p = 7.25 × 10−7, p = 2.10 × 10−5, from left to right, respectively). e Original T1WI scan of AFeAGd after incubation with different concentrations of FAPα (1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5 ng/mL). f Pseudocolor map of the concentration dependence of FAPα. g r1 for T1WI scans of AFeAGd after incubation with different concentrations of FAPα. h Scatter trends and histograms for r1, varying with FAPα concentration (n = 3 sample replications for each group, data are expressed as mean+SD). i Original T1WI scan of AFeAGd incubated with FAPα (1000 ng/mL) for different times (15, 30, 45, 60, 120 min). j Pseudocolor map of the incubation time dependence of FAPα. k r1 from T1WI scans of AFeAGd after incubation with FAPα for different times. l Scatter trends and histograms for r1, varying with incubation time (n = 3 sample replications for each group, data are expressed as mean+SD). m Original T1WI scan of AFeAGd after incubation with 500 ng/mL FAPα, MMPII, DPPIV, and the mixed enzyme. n Pseudocolor map of the enzyme response specificity of FAPα. o r1 from T1WI scans of AFeAGd after incubation with different enzymes. p Histogram of r1 for the enzyme response specificity of AFeAGd (n = 3 sample replications for each group, data are expressed as mean+SD. p = 2.70 × 10−5, p = 2.70 × 10−5, p = 2.90 × 10−5, from left to right, respectively). (Comparisons of continuous variables between two groups were made using student’s t-test. Three and more groups comparisons were made using ANOVA with a Tukey’s post hoc test. Two-tailed tests are applicable to all statistical analyses. ns for not significant, * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001).

Additionally, the variation in the T1-MRI signal showed a concentration dependence of FAPα. As the concentration of FAPα ranged from 62.5 to 1000 ng/mL, the MR images (T1 mapping grayscale and pseudocolor images) of AFeAGd became gradually brighter (Fig. 4e, f), and the longitudinal relaxivity (r1) of AFeAGd increased from 2.53 mM−1s−1 to 16.01 mM−1s−1 (Fig. 4g). The quantified T1-MRI histogram showed changes consistent with the corresponding MR images (Fig. 4h), further validating the responsiveness of AFeAGd to FAPα. Based on the FAPα -concentration dependent T1 changing of the nanoprobe in the aqueous solution, a standard curve was constructed to quantify FAPα concentration (Supplementary Fig. 21) (n = 3 for each FAP concentration including 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 ng/mL). Time-dependent T1-MR images revealed a gradual increase in brightness over time after incubating AFeAGd (0.0015-0.05 mM) with FAPα (500 ng/mL) (Fig. 4i, j). Concurrently, the relaxation rate gradually intensified over time (Fig. 4k, l). Notably, prolonged coincubation did not affect the relaxation rate, indicating the complete reaction of AFeAGd with FAPα within one hour. When AFeAGd was incubated with other enzymes (including MMP-II and DPP-IV, at 500 ng/mL), the minimal changes in T1-MR images (Fig. 4m, n) and the relaxation rate (Fig. 4o, p) indicated the specificity of AFeAGd to FAPα. Furthermore, AFeAGd maintained its stable and specific responsiveness to FAPα when it was coincubated with a mixture of these enzymes.

Characterization of FAPα in vivo and quantitative liver fibrosis mapping of AFeAGd in an animal model

We further validated the biomarker capacity of FAPα in the mice models of liver fibrosis. IHC demonstrated a more apparent spatial distribution of FAPα than other markers associated with liver fibrosis (Supplementary Fig. 22). The quantitative analysis further demonstrated an optimal linear fit (R2 = 0.85) between FAPα expression and liver fibrosis grade (Supplementary Figs. 23, 24). IHC positivity showed no significant difference between F3 and F4 fibrosis. It may due to the instability of the IHC method used for quantification. We further demonstrated such differential relationship by other means of FAPα quantification both in human samples and animal models. ROC curves also showed the ability of FAPα to differentiate between mild and severe fibrosis, as well as between normal and mild fibrosis (AUC = 97.2% and 88.1%, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 25). qPCR analysis of the mouse fibrosis model reinforced the superior diagnostic value of FAPα in assessing fibrosis grade (Supplementary Figs. 26–28). Immunoblotting revealed differential expression of FAPα between mice with various fibrosis grades, exhibiting a strong linear correlation of 0.97 with fibrosis grade (Supplementary Figs. 29, 30). In the animal model, there was also a positive correlation between the different levels of FAPα expression and the positive area of liver fibrosis (r > 0.90, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 31). These findings aligned with those obtained from the clinical fibrosis samples, further validating FAPα as a diagnostic marker for liver fibrosis grading.

The fibrosis grading performance of AFeAGd was further confirmed utilizing a 3.0 T clinical MRI scanner. The mice were intravenously injected with AFeAGd, followed by T1-MR imaging. The brightness of T1-weighted MRI gradually increased as the fibrosis grade advanced, which was consistent with the pathological changes in the corresponding liver (Fig. 5a). Similar to the results of T1-weighted imaging, the T1 mapping clearly demonstrated the difference in the degree of enhancement between mice with different grades of liver fibrosis (Fig. 5b). As the grade of liver fibrosis increased, the color of the liver gradually changed from orange-green to light blue to dark blue after AFeAGd nanoprobe injection, suggesting that the degree of enhancement varied among different grades of liver fibrosis. The mice’s livers of control group did not show significant enhancement and remained orange-green before and after the nanoprobe injection. It resulted from the FAPα concentration-responsive T1 enhancement of the AFeAGd nanoprobe. Specifically, the gradual increase in the expression of FAPα with increasing liver fibrosis grade resulted in different degrees of T1 recovery of the nanoprobe. It significantly shortened the T1 relaxation time of the liver29,30. Thus, the T1 mapping image of high-grade fibrotic livers changed from orange-red (high T1 value) before to blue-green (low T1 value) after AFeAGd injection. It also matched the liver enhancement effect in T1WI scans. The average ΔT1 values were 128.85 ms, −243.62 ms, −304.87 ms, −309.32 ms, and −390.98 ms, corresponding to normal and increased fibrosis-grade livers. The parameter signal-to-noise ratio (ΔSNR) revealed differences in MRI enhancement between the various groups (Fig. 5c). A significant linear correlation was observed between ΔSNR and FAPα expression in the corresponding samples (R2 = 0.83 and 0.90, respectively) (Fig. 5d). It also sensitively identified the individual fibrosis grades with AUC of 85.2%, 74.1%, 63.0%, and 96.3% for F1, F2, F3, and F4 fibrosis, respectively (Fig. 5e). Importantly, the ΔSNR of AFeAGd molecular imaging showed decent diagnostic efficacy when comparing between F2 to F4 vs. the rest or between F3 to F4 vs. the rest (AUC = 92.6% and 96.3%, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 32a, b). The contrast-to-noise ratio (ΔCNR) showed significant differences between different fibrosis grades (Fig. 5f). Interestingly, there was no significant difference between the F1 versus F2 groups and F3 versus F4 groups for ΔSNR, but a significant difference between all groups for ΔCNR. It may be related to CNR removing the interference of random signal intensity differences in different scanning batches, which may improve the accuracy in minor enhancement differences comparisons. There was a close linear correlation between ΔCNR and FAPα expression in the corresponding samples (R2 = 0.79 and 0.82, corresponding to WB and qPCR, respectively) (Fig. 5g). ΔCNR demonstrated desirable performance at grading specific liver fibrosis grade (Fig. 5h). Besides, ΔCNR also performed good when comparing between F2 to F4 vs. the rest or between F3 to F4 vs. the rest (AUC = 98.1% and 98.1%, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 32c, d). Finally, compared to T1WI scans without AFeAGd, the diagnostic accuracy of each fibrosis grade with the nanoprobe improved by 25.9%, 14.8%, 7.4%, and 23.6%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 33 and Table 1). In addition, we also used the control nanoprobe (AFe-AGPGPSAA-Gd) to image mice with different liver fibrosis grades. The results showed that for any grade of liver fibrosis mice or normal controls, the injection of the control nanoprobes did not cause significant T1-MRI signal changes (Supplementary Fig. 34). This confirms the imaging specificity of our constructed AFeAGd nanoprobes at the in vivo level.

Fig. 5. Quantitative liver fibrosis mapping of AFeAGd in the animal model.

a Representative images of T1WI-MRI acquired at two-time points (before and 1 h after injection) and corresponding H&E staining pictures in mice models (n = 3). b Representative images of T1 mapping and corresponding MASSON staining pictures in mice models (n = 3). c Histograms of ΔSNR in different grades of fibrotic mice (n = 3 biological replications, data are expressed as mean+SD. p = 0.0495, p = 0.5426, p = 0.0481, p = 0.1254, from left to right, respectively). d Linear correlation of ΔSNR with the quantitative WB expression (left) and qPCR quantification (right) of FAPα. e ROC curve for ΔSNR when identifying F1, F2, F3, and F4 liver fibrosis with other grades of fibrosis. f Histograms of ΔCNR in different grades of fibrotic mice (n = 3 biological replications, data are expressed as mean+SD. p = 0.0262, p = 0.0494, p = 0.0496, p = 0.0381, from left to right, respectively). g Linear correlation of ΔCNR with the quantitative WB expression (left) and qPCR quantification (right) of FAPα. h ROC curve for ΔCNR when identifying F1, F2, F3, and F4 liver fibrosis with other grades of fibrosis (n = 3). (Comparisons of continuous variables between two groups were made using student’s t-test. Three and more groups comparisons were made using ANOVA with a Tukey’s post hoc test. Two-tailed tests are applicable to all statistical analyses. ns for not significant, * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001).

Table 1.

AUC (95%CI) for identifying specific fibrosis grade in an animal model of liver fibrosis

| Fibrosis Grade | AUC (95%CI) (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T1WI without AFeAGd | T1WI with AFeAGd | ||

| T1WI | ΔSNR | ΔCNR | |

| F1 | 59.3 (27.0, 91.5) | 85.2 (57.7, 100) | 96.3 (85.7, 100) |

| F2 | 59.3 (9.6, 100) | 74.1 (46.1, 100) | 66.7 (36.6, 96.7) |

| F3 | 55.6 (18.7, 92.4) | 63.0 (31.3, 94.6) | 66.7 (36.6, 96.7) |

| F4 | 66.7 (31.3, 100) | 96.3 (85.7, 100) | 96.3 (85.7, 100) |

As fibrosis is a chronic and reversible disease process, monitoring the effectiveness of fibrosis treatment is crucial31,32. AFeAGd nanoprobes were used to assess the changes in the liver under different antifibrotic treatment (Supplementary Fig. 35). We observed that FAPα-MRI was sensitive to detect the treatment effects of different liver fibrosis treatments before and after therapy, whether using obeticholic acid, silybin, or curcumin as therapeutic drugs. The brightness in T1-MRI and T1 mapping images of the liver parenchyma in mice with F3 fibrosis exhibited significant enhancement upon AFeAGd injection. However, after the treatment, the mice displayed significantly lower T1 enhancement following AFeAGd administration (Supplementary Fig. 35a, b). Correspondingly, H&E slices depicted the pathological changes (Supplementary Fig. 35c). The ΔCNR, ΔSNR and -ΔT1 changed before and after anti-fibrosis treatment (Supplementary Fig. 36). In addition, we also analyzed the T1-MRI signal changes at different time points after AFeAGd injection. The results showed that even in livers with significant liver fibrosis, there was no significant enhancement 24 h after injection (Supplementary Fig. 37). It suggested that AFeAGd has a short re-injection window to monitor liver fibrosis’s evolution or the therapeutic effect.

Quantitative liver fibrosis mapping of AFeAGd in clinical samples

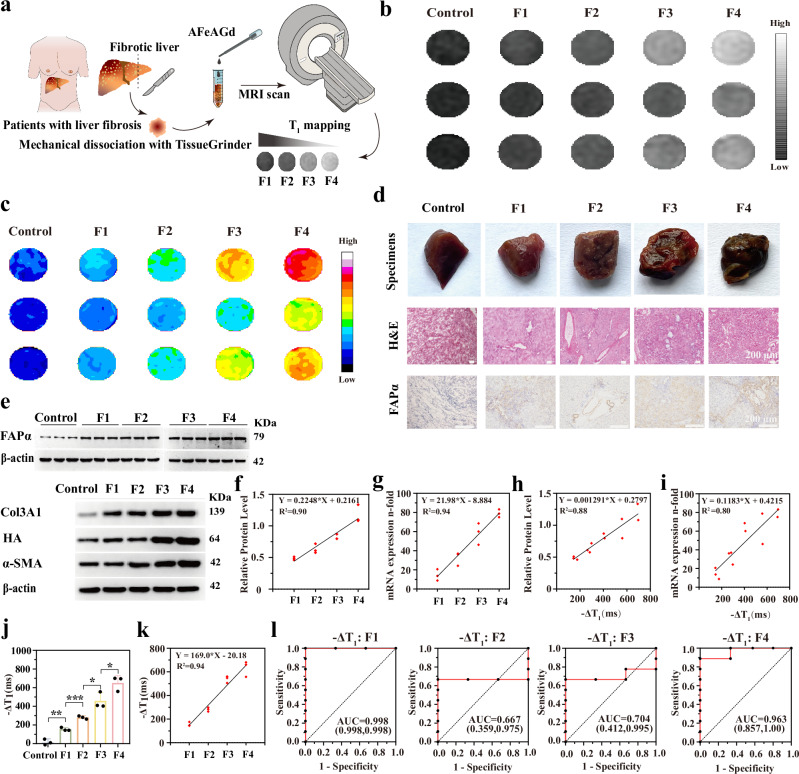

We further utilized AFeAGd nanoprobes to grade clinical liver fibrosis samples. Liver tissue homogenates with different fibrosis grades were incubated with AFeAGd (0.05 mM), followed by T1 mapping scans (Fig. 6a). T1 scan images of the tissues gradually brightened as the fibrosis grade increased (Fig. 6b). Pseudocolor maps provided more visualized significance for the differences (Fig. 6c). The corresponding clinical specimens showed distinctive morphological features, and the degree of IHC positivity for FAPα was also evident with increasing grade of fibrosis (Fig. 6d). The WB and qPCR results verified a more distinct difference in FAPα protein expression than other markers, with diagnostic fit values (R2) of 0.90 and 0.94, respectively (Fig. 6e–g).

Fig. 6. Quantitative liver fibrosis mapping of AFeAGd in the clinical samples.

a Schematic diagram of the quantitative liver fibrosis mapping of AFeAGd in the clinical sample. b Main T1WI MR images for liver fibrosis samples of different grades with added nanoprobes. c Pseudocolor map of clinical liver samples with nanoprobe injection. d Physical liver tissue, pathological staining and IHC expression of FAPα in different fibrosis samples used for the MRI study (each experiment was repeated 3 times independently with similarly results). e WB bands of FAPα and several other fibrosis grading markers (including α-SMA, collagen III, HA) in liver samples (each experiment was repeated 3 times independently with similarly results. The samples derive from the same experiment and that gels/blots were processed in parallel). f Linear correlation scatter plots between different liver fibrosis markers and liver fibrosis grade (for WB experiments) (n = 3). g Linear correlation scatter plots between different liver fibrosis markers and liver fibrosis grade (for qPCR) (n = 3). Scatter plots of the linear correlation between -ΔT1 value and FAPα expression at the protein level (h) and mRNA level (i) in clinical samples. j, k Histogram of -ΔT1 values and scatter plot of linear correlation between -ΔT1 value and fibrosis grades (n = 3 biological replications, data are expressed as mean+SD. p = 0.0054, p = 0.0009, p = 0.0285, p = 0.0497, from left to right, respectively). l ROC curve of -ΔT1 values in clinical samples for distinguishing F1, F2, F3, and F4 liver fibrosis from each other grade of fibrosis. (Comparisons of continuous variables between two groups were made using student’s t-test. Three and more groups comparisons were made using ANOVA with a Tukey’s post hoc test. Two-tailed tests are applicable to all statistical analyses. ns for not significant, * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001).

The linear correlation testing between the -ΔT1 value and FAPα expression (Fig. 6h, i) showed a linear fit (R2 = 0.88 for -ΔT1/FAPα protein levels, R2 = 0.80 for -ΔT1/FAPα mRNA expression). The -ΔT1 values changed from 9.77 ms to 649.30 ms as the fibrosis grade increased (Fig. 6j, Table 2). Based on the standard curves plotted previously, we speculated that the FAPα concentrations in the livers of F1-F4 liver fibrosis patients were about 11.19, 68.09, 217.68, and 328.16 ng/mL, respectively. There was a favorable linear relationship between the -ΔT1 value and the grade of liver fibrosis (R2 = 0.94) (Fig. 6k). The AUC of -ΔT1 when using AFeAGd nanoprobe for the differential diagnosis of F1, F2, F3, and F4 fibrosis were 99.8%, 66.7%, 70.4%, and 96.3%, respectively (Fig. 6l). We noted that the AUROC values for F2 and F3 were relatively low in human liver samples or animal models. It may be related to the computational methods of the AUROC model. The diagnostic values for the F2 and F3 groups were mainly located between the F1 and F4 groups. Therefore, it is difficult to obtain a high AUROC for F2 and F3 groups for a cut-off value that fits the diagnostic boundaries. -ΔT1 of AFeAGd also achieved comparisons between F2 to F4 vs. the rest or between F3 to F4 vs. the rest in clinical fibrosis samples (AUC = 99.8% and 99.8%, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 38). Overall, these findings showed that AFeAGd had the potential to accurately quantify FAPα in clinical samples to achieve fibrosis-grading imaging. Besides, we also validated that AFeAGd had significant biocompatibility in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Figs. 39–45).

Table 2.

−ΔT1 values for different grades of clinical liver fibrosis samples obtained by T1 mapping and the diagnostic efficacy of AFeAGd

| Fibrosis Grade | −ΔT1 ± SD (ms) | AUC (95%CI) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 9.77 ± 42.50 | / |

| F1 | 155.7 ± 17.71 | 99.8 (99.8, 99.8) |

| F2 | 281.5 ± 17.02 | 66.7 (35.9, 97.5) |

| F3 | 457.7 ± 89.38 | 70.4 (41.2, 99.5) |

| F4 | 649.3 ± 79.01 | 96.3 (85.7, 100.0) |

Discussion

In summary, we validated FAPα as a promising target for molecular imaging of the liver for fibrosis grading. The protein and mRNA expression levels of FAPα had a significant linear correlation with the degree of fibrosis (R2 = 0.89 and 0.91, respectively). Subsequently, we developed a responsive molecular MRI nanoprobe (AFeAGd) capable of detecting FAPα for quantitative liver fibrosis grading. AFeAGd showed favorable specificity, stability, and responsiveness to FAPα. In the animal model, AFeAGd achieved impressive AUC of 85.2%, 74.1%, 63.0%, and 96.3% for F1, F2, F3, and F4, respectively. More importantly, successful grading of liver fibrosis was accomplished in clinical liver samples, yielding AUC of 99.8%, 66.7%, 70.4%, and 96.3% for identifying F1, F2, F3, and F4, respectively. Compared to MRI scans without the nanoprobe, the diagnostic accuracy for each fibrosis grade was improved by 25.9%, 14.8%, 7.4%, and 23.6% by utilizing AFeAGd. This study highlights the strong potential for using FAPα in molecular imaging to grade liver fibrosis in the clinic.

Several noninvasive imaging techniques have also been applied to diagnose liver fibrosis grading in clinics. Ultrasound elastography is a commonly used fibrosis diagnostic technique for changes in liver stiffness. However, many pathologic factors also contribute to the increased liver stiffness33. In addition, it is limited by individual operator proficiency and abdominal fat deposits. MRE is not subject to individual physician variability or penetration depth. However, it is still difficult to avoid incorrectly determining the fibrosis grade in the mechanism due to increased liver stiffness caused by other factors34. FAPα-MRI does not rely on indirect physical changes such as stiffness to evaluate the fibrotic process but directly correlates the signal change with fundamental pathological changes in the degree of fibrosis. It may improve the accuracy of fibrosis grading and does not require complex equipment. Indeed, using molecular imaging methods to evaluate liver fibrosis accurately is a constant process35–37. Recent advancements have led to some breakthroughs38–42, but these achievements have been only demonstrated in animal models and the identification accuracy for specific liver fibrosis grades needs to be adequately reported. Back in 2006, superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-enhanced MRI43 was used to distinguish mild/severe fibrosis. It certainly started to evaluate pathological changes in liver fibrosis with molecular imaging tools. Salarian.M17,44 achieved early detection and staging of chronic liver disease using a protein MRI contrast agent targeting collagen, which vividly integrated the altered imaging signals with collagen deposition. A recent study45 broke through the traditional liver fibrosis markers based on extracellular allysine aldehyde (LysAld) pairs to achieve early detection in various fibrosis models and human samples. These studies undoubtedly provide directions for future molecular MRI with the revelation of pathological alterations in liver fibrosis.

On this basis, our study demonstrated the target selection and revealed its relationship with the pathological changes of liver fibrosis in the clinical samples. In addition, the nanoprobe designed to fit the chemical properties of FAPα was used to differentiate specific individual grades in liver fibrosis. It can provide some guidance for developing precision medicine in future liver fibrosis research. A new direction for molecular imaging biomarker detection emerges starting from clinical samples that specifically express a certain marker and then designing the corresponding molecular probes based on the structure-function characteristics of the marker. More valuably, the grading diagnostic efficacy was confirmed in the clinical patient samples with different grades of liver fibrosis. Interestingly, we found that the internal separation of the probe due to FAPα led to a higher T1 relaxation effect than using only Gd-DOTA. This phenomenon may further extend the interaction of MRET effects with conventional SBM theory and facilitate the development of novel responsive MRI probes46,47.

It is noteworthy that radioactive FAP tracers such as Gallium 68-labeled FAP inhibitor PET have become an effective tool for the precision diagnosis of tumor microenvironments48,49. The diagnostic value of FAPi-PET in benign diseases (including Crohn’s disease, atherosclerotic plaques, and fibrosis) is also being further explored50. Our FAPα-responsive MRI nanoprobe has unique advantages for in vivo FAPα detection. Firstly, the standard uptake value of FAPi-PET is affected by the binding affinity and specificity towards FAP. The off-target effects may affect the imaging specificity of FAPi-PET. Further molecular structure studies are needed to optimize the probe structure and FAPα-responsive affinity51,52. On the contrary, the T1 signal intensity of FAPα-MRI is based on the chemical property of FAPα to cut specific peptide chains. The enhancement effect is mainly associated with the FAPα content and not affected by interference factors such as ligand-receptor binding efficiency. Secondly, the unique metabolic characteristics of the nanoprobe enable it to be efficiently enriched by liver and macrophages, which contributes to its application in FAPα quantitative detection of liver fibrosis53,54. In addition, compared with FAPi-PET, FAPα-MRI is free from radiation and has a lower clinical cost, which is significant for the clinical screening of liver fibrosis. The higher spatial resolution of molecular MRI compared with PET also offers ancillary value in diagnosing focal or vascular diseases that may be associated with liver fibrosis. Although the FAPα-MRI probe achieved discrimination of liver fibrosis grades between human tissue and mice models in this study, demonstrating a partial solution to noninvasive grading diagnosis of liver fibrosis. Some limitations remain, such as the lack of external control samples in this single-center study. Moreover, the differences in the in vivo hemodynamic and physiological environments in clinical applications may affect their biodistribution, leading to potential diagnostic discrepancies. Future in vivo kinetic and preclinical studies are necessary to further validate and clarify the translational potential of FAPα-MRI nanoprobes and their instrumental value for noninvasive liver fibrosis grading.

Overall, this approach exhibits the potential to detect various chronic diseases, such as renal fibrosis, diabetes, and coronary heart disease, using molecular MRI55,56. Such advancements could provide valuable insights for future research in the field of molecular imaging.

Methods

All animal experiments followed the guidelines and protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (2023-HSYY-533GZS). The Institutional Review Board of Huashan Hospital approved the use of human samples and research for this study (approval number: 2021-HSYY-029). Written informed consent was obtained by all participants.

Characterization

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) images were captured by JEOL JEM 2100 F microscope and analyzed with Digital Micrograph software. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were measured on the Bruker D8 ADVANCE equipment. A dynamic light scattering analyzer measured the hydrodynamic sizes and Zeta potential of nanoparticles (DLS, Malvern ZS90). The metal ions concentration was measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (iCAP 7400 ICP-OES), the % refers to the percentage of Gd content of the corresponding organ over the Gd content of several major organs measured. This includes heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys to evaluate the distribution of the probe to the major organs after 1 h/8 h injection. Field-dependent magnetization curve was performed on Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (LakeShore7404). The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were obtained with a Bruker EMXplus EPR spectrometer. All MRI scans were obtained from a 3.0 T MRI scanner, GE Discovery 750 (GE Healthcare, America), and post-processed at an AEW4.6 workstation. The grinder was from Seville (KZ-II), fluorescent quantitative PCR was performed using Thermo-ABI QuantStudio 1, and reverse transcription operations were from SCILOGE-SCI1000-G. WB exposures were performed using HB-980 from Protein Simple.

Synthesis of amorphous iron nanoparticles (AFeNPs)

AFeNPs were synthesized by a pyrolysis method. First, in a 100 mL round-bottom flask, 20 mL of 1-otadecylene was mixed with 0.7 mL of oleylamine and heated to 80 °C under magnetic stirring. Subsequently, the Schlenk line system was used to pump out oxygen from the flask for about 0.5 h, followed by filling with Ar. After the mixture was heated to 175 °C at a heating rate of 0.5 °C/min, 0.5 mL of iron pentacarbonyl was rapidly injected into the reaction solution, and the mixed solution was maintained at 175 °C for 40 min. After cooling to room temperature, the solution was collected by centrifugation at 3500 g for 10 min and washed several times with n-hexane and anhydrous ethanol. Finally, the obtained AFeNPs were dispersed in 20 mL of n-hexane for storage.

Preparation of 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (DA)-coated AFeNPs

0.4 g of DA was first dissolved in a mixed solution with 3 mL of toluene and 1 mL of pyridine. The solution was then added dropwise into a toluene solution (20 mL) containing 200 mg of AFeNPs. With the addition of DA solution, DA-coated AFeNPs precipitated immediately. Removing the supernatant, excess ethanol was added and then centrifuged at 3500 g for 5 min. The precipitates were washed 3 times with deionized water and ethanol to remove residual toluene and methanol. Lastly, the resulting DA-coated AFeNPs could be easily dissolved in deionized water or PBS solution by hand shaking.

Synthesis of AFeAGd nanoprobe

A peptide linker with an ASGPAGPA sequence that contains a FAPα specific substrate was incorporated between DA-coated AFeNPs and Gd-DOTA. The FAPα cleavable linker ASGPAGPA (314 mg, 0.5 mmol) was reacted with DA-coated AFeNPs (Fe 10 mg) in the presence of 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-3-Ethylcarbodiimide (233 mg, 1.5 mmol) and N-Hydroxysulfosuccinimide sodium salt (651 mg, 3 mmol) in the MES buffer at room temperature for 2 h. The mixture was centrifuged for 3 times and purified by dialyzing against deionized water. Then, 4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid 3-sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester sodium salt (218 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added and stirred for 30 min, followed by adding Gd-DOTA (1.18 g, 3 mmol). The reaction was carried out at room temperature for 2 h, and the product was purified using a MACS column.

Differential expression gene identification

The GSE-13525157,58 dataset was used to identify the relative expression levels of differential genes in human liver fibrosis patients. Cases containing patients whose fibrosis grade information was included. The limma package was applied to screen for differential expression genes (DEGs) using the criteria of |log2(FC)| > 0.8 and Padj <0.05. GSE-193066 and GSE-19308059 dataset were analyzed as independent external validation datasets in the same method for differential transcript expression of FAPα. All statistical analyses of gene expression were performed using R (version 3.6.1) and GraphPad Prism (Version 8.0.2). Further, RNA sequencing was performed on the clinical liver samples from Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. The same steps described above were performed on that for differential gene identification.

Clinical liver samples

Liver fibrosis samples were obtained from tissue samples of donor and recipient patients undergoing liver transplantation at Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. After collection, all tissue samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use. The clinical indicators of the corresponding patients were obtained from the clinical data management system. The METAVIR scoring system60,61 (Supplementary Table 1) was used for fibrosis grading in the public fibrosis datasets and human fibrosis samples analysis. The sex distribution of the public datasets of patients with different grades of liver fibrosis applied in the study was as follows: GSE-135251 dataset: 1) F1 group (male: 22, female: 26); 2) F2 group (male: 21, female: 33); 3) F3 group (male: 38, female: 16); 4) F4 group (male: 9, female: 5). GSE-193066 dataset: 1) F1-F2 group (male: 44, female: 72); 2) F3-F4 group (male: 18, female: 24). GSE-193080 dataset: 1) F1-F2 group (male: 22, female: 8); 2) F3-F4 group (male: 19, female: 5). The sex distribution of the clinical samples of patients with different grades of liver fibrosis applied in the study was as follows: 1) Control group (male: 4, female: 4); 2) F1 group (male: 5, female: 3); 3) F2 group (male: 2, female: 6); 4) F3 group (male: 6, female: 2); 5) F4 group (male: 6, female: 2). Sex of all the participants was self-reported. The study did not conduct sex-based outcome analysis due to the relatively small sample size.

Pathological sections and biological evaluations of samples

Frozen samples were stained with H&E and MASSON trichrome staining. Specimens should be at least 1 cm long (1.5–2.5 cm). At least six or more confluent areas should be photographed under the microscope to assess the extent of fibrosis in the sample. The mRNA expression of FAPα and other markers in liver tissues was detected by quantitative real-time fluorescence PCR (qPCR). Bioengineering (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. designed and synthesized the primers, and the sequences are seen in Supplementary Table 2. The relative expression of the target gene was calculated for each sample using the 2ˉ△△CT method. Western Blot was performed. The film was scanned using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method for grey-scale analysis using Image J (V1.8.0, National Institutes of Health) software. The uncropped blots were supplied in the Source data file. The source and amount/dilution of all antibodies used were as followings: polyclonal Anti-FAP (abcam; ab207178; 1:200), polyclonal ANTI-HABP2 (abcam; ab181837, 1:200), polyclonal Anti-alpha smooth Actin antibody (abcam; ab7817; 1:200), polyclonal Anti-COLLAGEN III Antibody (abcam; ab184993; 1:200). Validation information for all antibodies used in the study are available on the manufacturers’ website. Each experiment was repeated three times, and the average value was taken. All the pathological sections in the study were evaluated and analyzed by two pathologists with more than ten years of experience in hepatobiliary diagnosis from Huashan Hospital, Fudan University.

In vitro MRI relaxation measurements

In vitro MRI scans were performed by a 3.0 T MRI (Discovery MR 750, General Motors, USA) using a spin-echo pulse sequence to obtain T1WI and T1 mapping. The T1 value was quantified from the obtained T1 mapping using an ADW 4.6 workstation and linearly regressed at 1/T1 against the Gd concentration in the corresponding sample. The slope of the straight line was the longitudinal relaxation rate r1 of the sample to be tested. The MRI scan parameters were as follows: inversion time (TI) (50, 100, 150, 200, 300, 400, 800, 1500, and 2000 ms); repetition time (TR) of 5000 ms; echo chain length (ETL) = 8; echo time (TE) of 7.9 ms.

Gd-DOTA, AFe, and AFeAGd were diluted with PBS buffer into three solutions with different concentrations (0.0500, 0.02500, 0.0125, 0.00625, 0.003125 mM). The r1 and T1 of each group were measured. AFeAGd was diluted into a series of solutions with different Gd concentrations (0.0500, 0.02500, 0.0125, 0.00625, 0.003125 mM) using PBS buffer, respectively. FAPα was added to each group, and the final concentration of FAPα in each group was 1000/500/250/125/62.5 ng/mL. T1 and r1 values were measured according to the above method. For Time-dependent MRI of FAPα, AFeAGd was diluted into a series of solutions with different Gd concentrations (0.0500, 0.02500, 0.0125, 0.00625, 0.003125 mM), respectively. FAPα was added separately to give a final 1000 ng/mL concentration. MRI scans were performed at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 min of incubation. Each group’s T1 and r1 values were determined according to the previous method. AFeAGd was diluted into a series of solutions with different Gd concentrations (0.0500, 0.02500, 0.0125, 0.00625, 0.003125 mM) using PBS buffer. Four groups were set up for enzyme-specificity tests: FAPα, MMP-II, DPP-IV, and Mixed. The final concentration of all three enzymes in each tube was adjusted to 500 ng/mL. Each group’s T1 and r1 values were determined.

For liver samples imaging, 200 μL of nanoprobe (AFeAGd, 0.05 mM Gd) was added to a 1.5 mL EP tube with 800 μL of tissue homogenate from clinical samples with different grades of liver fibrosis. After co-incubation for 1 h, the T1 values of the tissue homogenate and probe mixture were measured as described above.

Animals

Mice with a C57BL/6 (25 g, 6 w, female) genetic background (Shanghai Silaike Laboratory Animal Technology Co) were used. Mice were randomly divided into the control and modeling groups. Mice were raised in the SPF laboratory animal center of Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University. The temperature was maintained at 22 ± 2 °C and the relative humidity was maintained at 50 ± 5%, with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Control mice were fed with standard rodent food (ID: 1010088, from Jiangsu Xietong Pharmaceutical Bio-engineering Co., Ltd, Nanjing, China) and water. To induce the mice models with different grades of liver fibrosis, experimental C57BL/6 mice were fed a NASH diet for 1–3 months, mainly consisting of methionine-choline deficient (MCD) chow (ID: A02082002B, from SHU YI SHU ER inc, Changzhou, China) and other conditions were the same as the control group mice. To develop high-grade fibrosis model, CGI-58 knocked out mice (purchased from the Model Animal Institute of Nanjing University, Nanjing, China) were fed the same NASH diet above62. To evaluate the degree of liver fibrosis, H&E and MASSON slices were obtained and analyzed based on the METAVIR scoring system. All mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide (CO2) asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation to ensure death. The euthanasia process was performed in a dedicated chamber where CO2 was introduced at a displacement rate of 30–70% of the chamber volume per minute. Mice were observed continuously until the cessation of respiratory movements. After two minutes of confirmed apnea, cervical dislocation was performed to ensure death.

In vivo MRI scans of AFeAGd

All mice were imaged on a 3.0 T MRI scanner (Discovery MR 750, General Motors, USA) with an 8-channel mice coil at Huashan Hospital, Shanghai, China. Mice in the experimental and control groups were randomly selected and injected with AFeAGd and PBS solutions. Before and one h after the dosing of AFeAGd, the images were processed by using a T1W-FSE sequence with TR = 400 ms, TE = 12 ms, Flip angle 142, ETL = 5, Matrix = 288 × 288, NEX = 4, layer thickness = 1 mm, Interval = 0.1 mm. The MRI-equipped workstation (ADW4.6 workstation, General Motors, USA) was used for the analysis and pseudo-color image processing.

For the treatment efficacy assessment experiment, C57/BL6 mice were fed with MCD chow for two months to construct the high-grade liver fibrosis models according to the previously described method. After an MRI examination, Obeticholic acid/Silymarin/Curcumin/ was given for different treatment groups. Obeticholic acid (OCA) group: OCA solution was prepared, given at the dose of 15 mg/kg/d. Silymarin group: Silymarin solution was prepared (5 mL CMC-Na dissolved in 100 mg of silymarin powder), given at the dose of 80 mg/kg/d. Curcumin group: Curcumin solution was prepared (10 mL/kg curcumin after mixing with 5 mg/L CMC-Na), given at the dose of 200 mg/kg/d. All the above three groups were administered by gavage for four weeks. After treatment, the model mice received FAPα-enhanced MRI again. Then we compared the differences in MRI enhancement parameters and the obtained pathologic sections before and after the mice treated with different therapies.

The T1-MRI signal intensity of the region of interest was measured by an experienced radiologist unaware of the study. Regions of interest were manually drawn as circles or ellipses to contain as many hyper-enhanced sections as possible (mean number of pixels 3) from three different regions in the liver. For T1 mapping imaging sequences, the T1 value was calculated using the same sampling method. The parameters used in the calculation were the following: CNR = (SIliver-SImuscle)/SDair, ΔCNR = (CNRpost-CNRpre), SNR = SIliver/SDair, ΔSNR = (SNRpost-SNRpre), -ΔT1 = -(T1post-T1pre).

In vivo biosafety experiments

The cytotoxicity of AFeAGd was determined by incubating the JS-1 cells, Raw 264.7 cells and THP-1 cells (all purchased from Rui Bao He Biological Company, Shanghai, China) in their respective specific cell culture medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cell line used in the study were authenticated using STR profiling by the manufacturer. Cell viability was assessed by the CCK8 assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at an absorption wavelength of 450 nm was measured by an enzyme marker (Bio-TekELx800, USA). AFeAGd (0.05 mmol Gd/kg) or PBS was injected intravenously into normal ICR mice (25 g, 6 w, female, Charles River, Beijing, China). After 3 and 30 d of injection, mice were executed. Major organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, were then collected for H&E staining to assess toxicity. Routine blood tests were performed at Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. In addition, the body weight of each animal was recorded for 30 days.

Statistical treatment

The quantitative data were expressed as mean + SD. Differences between the two independent means were assessed by Student’s t-test. Pearson correlation analysis and Spearman correlation analysis were performed for normally distributed and non-normally distributed data, respectively. In addition, linear correlation analysis was also used in the correlation analysis section of the article. ROC curves and AUC were used to evaluate the stratification diagnostic performance. When performing the ROC curve analysis, an AUC value of 1.00 representing a completely correct diagnosis, we took an AUC value of 0.998 as representative due to the relatively small sample size of each group. All p-values were two-sided, and p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad 8.0.2 software (GraphPad Software Inc, USA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (22235004, W.B.), and Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2023ZKZD01, W.B.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071877, J.Z.), The National Science Foundation for the Young Scientists of China (Grant 52102351, X.M.). We acknowledge Dr. Zunguo Du and Dr. Ji Xiong (all from the Department of Pathology, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University) for their valuable support on the pathologic diagnosis and evaluation.

Author contributions

W. B., J. G., Y. W., X. M., and X. W. conceived the project and designed the experiments. Y. W, X. M., and G. L. synthesized materials. J. G. performed in vitro biological experiments. H. X. and F. H. collected and analyzed the data. J. G., S. W., and L. Z. analyzed the results. W. B., J. Z., X. F., X. J., and Z. Y. supervised the entire project. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Naoto Fujiwara, Francesca Garello, Manuel Roehrich, Sudhakar Venkatesh and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The main data supporting the results in this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. All data generated in this study are available from the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper as a Source data file. The reused dataset in the study could be obtained via the following links: GSE-135251 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE135251], GSE-193066 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE193066], and GSE-193080 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE193080]). The RNA-Seq data generated in this study have been stored in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are available by accessing the following link: PRJNA1137073. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1137073.] Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jiahao Gao, Ya Wang, Xianfu Meng, Xiaoshuang Wang.

Contributor Information

Xiangming Fang, Email: xiangming_fang@njmu.edu.cn.

Jiawen Zhang, Email: jiawen_zhang@fudan.edu.cn.

Wenbo Bu, Email: wbbu@fudan.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-52308-3.

References

- 1.Hernandez-Gea, V. & Friedman, S. L. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol.6, 425–456 (2011). 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kisseleva, T. & Brenner, D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.18, 151–166 (2021). 10.1038/s41575-020-00372-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor, R. S. et al. Association Between Fibrosis Stage and Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology158, 1611–1625.e1612 (2020). 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boursier, J. et al. Practical diagnosis of cirrhosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease using currently available non-invasive fibrosis tests. Nat. Commun.14, 5219 (2023). 10.1038/s41467-023-40328-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman, Z. D. Grading and staging systems for inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver diseases. J. Hepatol.47, 598–607 (2007). 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao, G., Yang, J. & Yan, L. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index and fibrosis-4 index for detecting liver fibrosis in adult patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology61, 292–302 (2015). 10.1002/hep.27382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin, Z. H. et al. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology53, 726–736 (2011). 10.1002/hep.24105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel, K. & Sebastiani, G. Limitations of non-invasive tests for assessment of liver fibrosis. JHEP Rep.2, 100067 (2020). 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaheen, A. A. & Myers, R. P. Diagnostic accuracy of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review. Hepatology46, 912–921 (2007). 10.1002/hep.21835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang, J. X. et al. An individual patient data meta-analysis to determine cut-offs for and confounders of NAFLD-fibrosis staging with magnetic resonance elastography. J. Hepatol.79, 592–604 (2023). 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barr, R. G. et al. Elastography Assessment of Liver Fibrosis: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology276, 845–861 (2015). 10.1148/radiol.2015150619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe, S. P. & Pomper, M. G. Molecular imaging in oncology: Current impact and future directions. CA Cancer J. Clin.72, 333–352 (2022). 10.3322/caac.21713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montesi, S. B., Désogère, P., Fuchs, B. C. & Caravan, P. Molecular imaging of fibrosis: recent advances and future directions. J. Clin. Invest.129, 24–33 (2019). 10.1172/JCI122132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng, S. et al. Conventional and artificial intelligence-based computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging quantitative techniques for non-invasive liver fibrosis staging. Eur. J. Radiol.165, 110912 (2023). 10.1016/j.ejrad.2023.110912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman, S. L. & Pinzani, M. Hepatic fibrosis 2022: Unmet needs and a blueprint for the future. Hepatology75, 473–488 (2022). 10.1002/hep.32285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuchs, B. C. et al. Molecular MRI of collagen to diagnose and stage liver fibrosis. J. Hepatol.59, 992–998 (2013). 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salarian, M. et al. Early detection and staging of chronic liver diseases with a protein MRI contrast agent. Nat. Commun.10, 4777 (2019). 10.1038/s41467-019-11984-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, Q. B. et al. MR Imaging of activated hepatic stellate cells in liver injured by CCl4 of rats with integrin-targeted ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide. Eur. Radiol.21, 1016–1025 (2011). 10.1007/s00330-010-1988-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi, J. S. et al. Distance-dependent magnetic resonance tuning as a versatile MRI sensing platform for biological targets. Nat. Mater.16, 537–542 (2017). 10.1038/nmat4846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin, T. H. et al. A magnetic resonance tuning sensor for the MRI detection of biological targets. Nat. Protoc.13, 2664–2684 (2018). 10.1038/s41596-018-0057-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalluri, R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer16, 582–598 (2016). 10.1038/nrc.2016.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, C. et al. An electric-field-responsive paramagnetic contrast agent enhances the visualization of epileptic foci in mouse models of drug-resistant epilepsy. Nat. Biomed. Eng.5, 278–289 (2021). 10.1038/s41551-020-00618-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ning, Y. et al. Dual Hydrazine-Equipped Turn-On Manganese-Based Probes for Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Liver Fibrogenesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 16553–16558 (2022). 10.1021/jacs.2c06231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai, J. et al. A Telomerase-Activated Magnetic Resonance Imaging Probe for Consecutively Monitoring Tumor Growth Kinetics and In Situ Screening Inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 1108–1117 (2023). 10.1021/jacs.2c10749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao, X. X. et al. In|Situ Self-Assembled Nanofibers Precisely Target Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts for Improved Tumor Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.58, 15287–15294 (2019). 10.1002/anie.201908185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji, T. et al. Transformable Peptide Nanocarriers for Expeditious Drug Release and Effective Cancer Therapy via Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.55, 1050–1055 (2016). 10.1002/anie.201506262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, Z. et al. Two-way magnetic resonance tuning and enhanced subtraction imaging for non-invasive and quantitative biological imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol.15, 482–490 (2020). 10.1038/s41565-020-0678-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wahsner, J., Gale, E. M., Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A. & Caravan, P. Chemistry of MRI Contrast Agents: Current Challenges and New Frontiers. Chem. Rev.119, 957–1057 (2019). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puntmann, V. O., Peker, E., Chandrashekhar, Y. & Nagel, E. T1 Mapping in Characterizing Myocardial Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Circ. Res.119, 277–299 (2016). 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor, A. J., Salerno, M., Dharmakumar, R. & Jerosch-Herold, M. T1 Mapping: Basic Techniques and Clinical Applications. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging9, 67–81 (2016). 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao, X., Kwan, J. Y. Y., Yip, K., Liu, P. P. & Liu, F. F. Targeting metabolic dysregulation for fibrosis therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov.19, 57–75 (2020). 10.1038/s41573-019-0040-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wynn, T. A. & Ramalingam, T. R. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat. Med.18, 1028–1040 (2012). 10.1038/nm.2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoodeshenas, S., Yin, M. & Venkatesh, S. K. Magnetic Resonance Elastography of Liver: Current Update. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging27, 319–333 (2018). 10.1097/RMR.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin, M. et al. Hepatic MR Elastography: Clinical Performance in a Series of 1377 Consecutive Examinations. Radiology278, 114–124 (2016). 10.1148/radiol.2015142141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin, H. et al. Advanced near-infrared light approaches for neuroimaging and neuromodulation. BMEMat1, e12023 (2023). 10.1002/bmm2.12023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, P. et al. Peptide-based nanoprobes for molecular imaging and disease diagnostics. Chem. Soc. Rev.47, 3490–3529 (2018). 10.1039/C7CS00793K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andreou, C., Weissleder, R. & Kircher, M. F. Multiplexed imaging in oncology. Nat. Biomed. Eng.6, 527–540 (2022). 10.1038/s41551-022-00891-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, Y. A., Wallace, M. C. & Friedman, S. L. Pathobiology of liver fibrosis: a translational success story. Gut64, 830–841 (2015). 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henderson, N. C., Rieder, F. & Wynn, T. A. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature587, 555–566 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2938-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pirasteh, A. et al. Staging Liver Fibrosis by Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor PET in a Human-Sized Swine Model. J. Nucl. Med.63, 1956–1961 (2022). 10.2967/jnumed.121.263736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petitclerc, L., Sebastiani, G., Gilbert, G., Cloutier, G. & Tang, A. Liver fibrosis: Review of current imaging and MRI quantification techniques. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging45, 1276–1295 (2017). 10.1002/jmri.25550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, C. et al. Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of activated hepatic stellate cells with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide targeting integrin αvβ3 for staging liver fibrosis in rat model. Int. J. Nanomed.11, 1097–1108 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aguirre, D. A., Behling, C. A., Alpert, E., Hassanein, T. I. & Sirlin, C. B. Liver fibrosis: noninvasive diagnosis with double contrast material-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology239, 425–437 (2006). 10.1148/radiol.2392050505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennedy, P. & Taouli, B. Collagen-targeted MRI contrast agent for liver fibrosis detection. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17, 201–202 (2020). 10.1038/s41575-020-0266-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ning, Y. et al. Molecular MRI quantification of extracellular aldehyde pairs for early detection of liver fibrogenesis and response to treatment. Sci. Transl. Med.14, eabq6297 (2022). 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq6297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou, Z., Yang, L., Gao, J. & Chen, X. Structure-Relaxivity Relationships of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Adv. Mater.31, e1804567 (2019). 10.1002/adma.201804567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoo, D., Lee, J. H., Shin, T. H. & Cheon, J. Theranostic magnetic nanoparticles. Acc. Chem. Res.44, 863–874 (2011). 10.1021/ar200085c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chandekar, K. R., Prashanth, A., Vinjamuri, S. & Kumar, R. FAPI PET/CT Imaging-An Updated Review. Diagnostics13, 201–212 (2023). 10.3390/diagnostics13122018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao, L. et al. Fibroblast activation protein-based theranostics in cancer research: A state-of-the-art review. Theranostics12, 1557–1569 (2022). 10.7150/thno.69475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mori, Y. et al. FAPI PET: Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor Use in Oncologic and Nononcologic Disease. Radiology306, e220749 (2023). 10.1148/radiol.220749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang, D. et al. [(68)Ga]Ga-FAPI PET for the evaluation of digestive system tumors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging50, 908–920 (2023). 10.1007/s00259-022-06021-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Langbein, T., Weber, W. A. & Eiber, M. Future of Theranostics: An Outlook on Precision Oncology in Nuclear Medicine. J. Nucl. Med.60, 13s–19s (2019). 10.2967/jnumed.118.220566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Behzadi, S. et al. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: journey inside the cell. Chem. Soc. Rev.46, 4218–4244 (2017). 10.1039/C6CS00636A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, S., Gao, H. & Bao, G. Physical Principles of Nanoparticle Cellular Endocytosis. ACS Nano9, 8655–8671 (2015). 10.1021/acsnano.5b03184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner, R. et al. Metabolic implications of pancreatic fat accumulation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol.18, 43–54 (2022). 10.1038/s41574-021-00573-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beijnink, C. W. H. et al. Cardiac MRI to Visualize Myocardial Damage after ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Review of Its Histologic Validation. Radiology301, 4–18 (2021). 10.1148/radiol.2021204265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pfister, D. et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature592, 450–456 (2021). 10.1038/s41586-021-03362-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Govaere, O. et al. Transcriptomic profiling across the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease spectrum reveals gene signatures for steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Sci. Transl. Med.12, eaba4448 (2020). 10.1126/scitranslmed.aba4448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujiwara, N. et al. Molecular signatures of long-term hepatocellular carcinoma risk in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Transl. Med.14, eabo4474 (2022). 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo4474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chowdhury, A. B. & Mehta, K. J. Liver biopsy for assessment of chronic liver diseases: a synopsis. Clin. Exp. Med.23, 273–285 (2023). 10.1007/s10238-022-00799-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li, C., Li, R. & Zhang, W. Progress in non-invasive detection of liver fibrosis. Cancer Biol. Med.15, 124–136 (2018). 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown, J. M. et al. CGI-58 knockdown in mice causes hepatic steatosis but prevents diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance. J. Lipid Res.51, 3306–3315 (2010). 10.1194/jlr.M010256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The main data supporting the results in this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. All data generated in this study are available from the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper as a Source data file. The reused dataset in the study could be obtained via the following links: GSE-135251 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE135251], GSE-193066 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE193066], and GSE-193080 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE193080]). The RNA-Seq data generated in this study have been stored in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are available by accessing the following link: PRJNA1137073. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1137073.] Source data are provided with this paper.