Abstract

Background

All patients starting dialysis should be informed of kidney transplant as a renal replacement therapy option. Prior research has shown disparities in provision of this information. In this study, we aimed to identify patient sociodemographic and dialysis facility characteristics associated with not receiving transplant information at the time of dialysis initiation. We additionally sought to determine the association of receiving transplant information with waitlist and transplant outcomes.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed CMS-2728 forms filed from 2007 to 2019. The primary outcome was report of provision of information about transplant on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Form CMS-2728. For patients not informed at the time of dialysis, we collected the reported reason for not being informed (medically unfit, declined information, unsuitable due to age, psychologically unfit, not assessed, or other). Cox proportional-hazards model estimates were used to study determinants of addition to the waitlist and transplant (secondary outcomes).

Results

Fifteen percent of patients did not receive information about transplant (N = 133,414). Non-informed patients were more likely to be older, female, white, and on Medicare. Patients informed about transplant had a shorter time between end-stage renal disease onset and addition to the waitlist; they also spent a shorter time on the waitlist before receiving a transplant. Patients at chain dialysis facilities were more likely to receive information, but this did not translate into higher waitlist or transplant rates. Patients at independent facilities acquired by chains were more likely to be informed but less likely to be added to the waitlist post acquisition.

Conclusions

Disparities continue to persist in providing information about transplant at initiation of dialysis. Patients who are not informed have reduced access to the transplant waitlist and transplant. Maximizing the number of patients informed could increase the number of patients referred to transplant centers, and ultimately transplanted. However, policy actions should account for differences in protocols stemming from facility ownership.

Keywords: CMS-2728, Renal transplant, Patient education

1. Background

For the nearly one million patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States, kidney transplant has several advantages over dialysis, including longer patient survival and improved quality of life [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. Patient education is an important component of making informed decisions about ESRD treatment options, as early access to nephrology care has been shown to result in improved patient satisfaction with ESRD treatment and higher rates of kidney transplant [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. Despite these benefits, a substantial number of patients with ESRD report limited discussions with their doctors about ESRD treatment options and a lack of knowledge about kidney transplant [[9], [10], [11]].

For patients who lack early access to nephrology care, education about ESRD treatment options should occur at initiation of dialysis [12]. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires the submission of a Medical Evidence Form (CMS-2728) for all patients with ESRD within 45 days of initiating

dialysis. In 2005, the form was amended to include a question about the provision of kidney transplant information; if information is not provided, the reason for not providing it must be specified. Prior research has found disparities in receipt of information about kidney transplant based on social determinants of health that include race, gender, and insurance status [[13], [14], [15]]. Since then, several important policy changes have occurred to improve patient education of chronic kidney disease (CKD), ESRD, and transplant, including the 2019 Advancing American Kidney Health Initiative.

We hypothesized that despite 15 years since the modifications to Form 2728, persistent disparities remain in which patients are provided information about transplant at initiation of dialysis. We also hypothesized that a lack of early information about transplant contributes to disparities in kidney transplantation. The purpose of this study was to (1) quantify the reported provision of transplant information as indicated on the Medical Evidence Form, (2) identify sociodemographic risk factors for not receiving transplant information at the time of dialysis initiation, (3) determine the association of dialysis facility characteristics with reported provision of transplant information, and (4) determine the association of reported transplant information with waitlist and transplant outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and data source

This was a retrospective analysis of patients aged 18 to 75 with a newly filed Medical Evidence Form during the study period between January 1, 2008 to January 1, 2019 using data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). USRDS includes all patients in the United States who develop ESRD and require renal replacement therapy via either dialysis or a kidney transplant. This research was approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board under protocol 2017-0556.

2.2. Outcomes, exposures, and covariates

The primary outcome was reported provision of transplant information, as indicated on Medical Evidence Form 2728. For patients not informed at the time of dialysis, we collected the reason for not being informed (medically unfit, declined information, unsuitable due to age, psychologically unfit, not assessed, or other). Secondary outcomes were addition to the transplant waitlist and transplant rate.

Characteristics thought to be associated with the likelihood of receiving transplant education included the following: receiving nephrology care pre-ESRD, dialysis facility ownership, initial dialysis access, alcohol dependence, drug dependence, inability to ambulate, inability to transfer, and needing assistance with activities of daily living. The following dialysis facility characteristics were also considered: number of patients per registered nurse, number of patients per technician, and number of patients per social worker.

A complete list of characteristics can be found in Table 1. The models described below are estimated by controlling for all of these characteristics, while only major results and coefficients are reported in the Tables.

Table 1.

Variables analyzed in the patient population.

| Variables | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Gender | M |

| F | |

| BMI | >40 |

| ≤40 | |

| Race/ethnicity | Black |

| White | |

| Asian | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | |

| Pacific Islander | |

| Hispanic | |

| Insurance (at the time of diagnosis) | Private |

| Medicaid | |

| Medicare | |

| Medicare&Medicaid | |

| Medicare&Other | |

| Other | |

| Applying for Medicare | Yes |

| No | |

| Employment status | Employed full-time |

| Emp part-time | |

| Homemaker or Unemployed | |

| Medical Leave of absence (LOA) | |

| Other | |

| Retired | |

| ESRD case | Cystic Kidney |

| Diabetes | |

| Glomerulonephritis | |

| Hypertension | |

| Other urologic | |

| Other cause | |

| Nephrology care pre ESRD | Yes |

| No | |

| Facility ownership | Chain |

| Independent | |

| First access | Arteriovenous Fistula |

| Indwelling catheter | |

| Arteriovenous Graft | |

| Other | |

| Region | NE |

| MW | |

| S | |

| W | |

| Alcohol dependence | Yes |

| No | |

| Drug dependence | No |

| Yes | |

| Inability to ambulate | No |

| Yes | |

| Inability to transfer | No |

| Yes | |

| Needing assistance in ADLs | No |

| Yes | |

| Patients per registered nurse | |

| Patients per technician | |

| Patients per social worker |

2.3. Informed about transplant

Logistic regression models were constructed in which the dependent variable is whether the patient has not been informed of transplant options and each reason for which the patient has not been informed.1 The models for each reason were run on the subset of patients who have not been informed of transplant options. The reference variables to calculate the odds ratio were the following for their respective categories: polycystic kidney for the variable “disease,” arteriovenous fistula for the variable “vascular access,” group (private) for the variable “insurance status (at the time of diagnosis),” white for the variable “race,” employed full time for the variable “employment”, and Midwest for the variable “region”.

2.4. Time to waitlist

We calculated Cox proportional-hazards model estimates for the time to waitlist after a patient's signature of the Medical Evidence Form. We consider as study end date the latest addition date observed in the whole dataset (October 08, 2018). For patients who do not reach the event of interest during the study observation period, we record when the patient was censored due to study end date or due to the

Occurrence of an event that prevents further follow-up of the patient (e.g., death) [16]. We also restrict the dataset to patients whose Medical Evidence Form was submitted by 12/31/2015 to account for the fact that those patients who started dialysis towards the end of the study period were not given an adequate opportunity to be waitlisted. A hazard ratio above one indicates a covariate that is positively associated with the event probability (i.e., being added to the waitlist), and thus negatively associated with the time to waitlisting.

2.5. Time to transplant

We calculated Cox proportional-hazards model estimates for time to transplant after being added to the waitlist, which was conditional on being added to the waitlist. We consider as study end date the last time a transplant is observed in the dataset (October 08, 2018). For patients who do not reach the event of interest during the study observation period, we record when the patient was censored due to study end date or due to the occurrence of an event that prevents further follow-up of the patient (e.g., death). We further restrict the dataset to patients whose Medical Evidence Form was submitted by 12/31/2015 to account for the fact that those patients who started dialysis towards the end of the study period were not given an adequate opportunity to be transplanted. Pre-emptive transplant recipients were excluded from the analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of non-informed patients

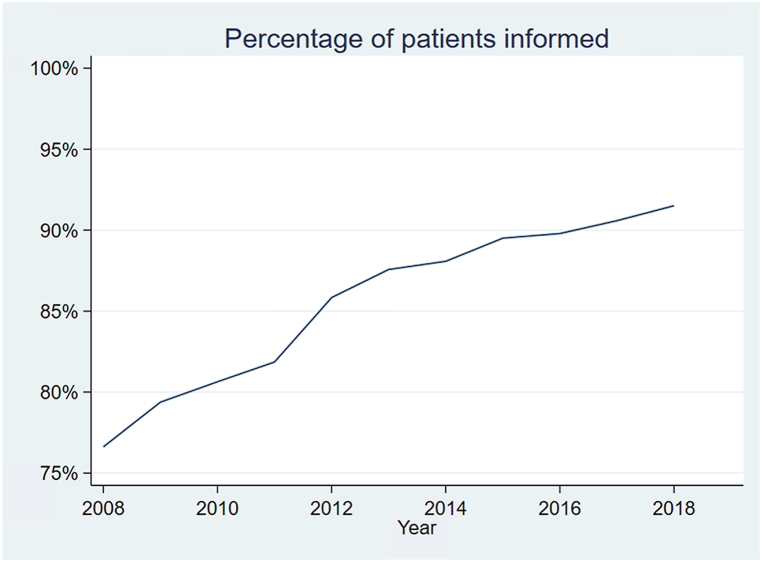

Between 2008 and 2019, 944,015 patients initiated renal replacement therapy. Reported provision of transplant information has increased over study time (Fig. 1). Of all patients included, 133,414 (14.52 %) did not receive information about kidney transplant (Table 2). Non-informed patients were more likely to be female (43 vs 42 %, CIs [42.55; 43.09] and [41.77; 41.99]), white (52 vs 47 %, CIs [51.96; 52.49] and [46.89; 47.11]), and obese (13 vs 12 %, CIs [12.81; 13.18] and [11.92; 12.07]). Non-informed patients were about 3 years older than informed patients, on average. Socioeconomic characteristics were also associated with the reported provision of information: patients receiving information were more likely to be on private insurance at the time of diagnosis (18 vs 10 %, CIs [18.00; 18.17] and [9.97; 10.30]), and being employed full time (12 vs 5 %, CIs [11.99; 12.14] and [5.29; 5.54]).

Fig. 1.

Trends in the proportion of patients being informed.

Percentage of patients receiving information about transplant options during the study period (2008–2018).

Table 2.

Medical and sociodemographic characteristics by kidney transplant education.

| Patient characteristics n (%) [95 % CI] | Informed | Not informed | CIs (95 %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 785,382 (85.48 %) [85.41; 85.55] | 133,414 (14.52 %) [14.45; 14.59] | ||

| Gender | F | 328,884 (41.88 %) [41.77; 41.99] | 57,122 (42.82 %) [42.55; 43.09] | |

| M | 410,285 (58.12 %) [58.01; 58.23] | 93,467 (57.18 %) [56.91; 57.45] | ||

| BMI | ≤40 | 686,098 (88.01 %) [87.93; 88.08] | 114,935 (87.01 %) [86.82; 87.19] | |

| >40 | 93,495 (11.99 %) [11.92; 12.07] | 191,191 (12.99 %) [12.81; 13.18] | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Asian | 29,726 (3.78 %) [3.74; 3.83] | 4148 (3.11 %) [3.02; 3.20] | |

| Black | 237,382 (30.23 %) [30.12; 30.33] | 37,585 (28.17 %) [27.93; 28.42] | ||

| Hispanic | 130,634 (16.63 %) [16.55; 16.72] | 18,636 (13.97 %) [13.78; 14.16] | ||

| Other | 18,533 (2.36 %) [2.33; 2.39] | 3367 (2.52 %) [2.44; 2.61] | ||

| White | 369,093 (47.00 %) [46.89; 47.11] | 69,672 (52.22 %) [51.96; 52.49] | ||

| Insurance (at the time of diagnosis) | Private | 141,114 (18.09 %) [18.00; 18.17] | 13,453 (10.13 %) [9.97; 10.30] | |

| Medicare | 129,922 (16.65 %) [16.57; 16.73] | 24,052 (18.12 %) [17.91; 18.32] | ||

| Other | 509,235 (65.26 %) [65.16; 65.37] | 95,254 (71.75 %) [71.51; 71.99] | ||

| Employment status | Employed full-time | 94,750 (12.06 %) [11.99; 12.14] | 7225 (5.42 %) [5.29; 5.54] | |

| Homemaker or Unemployed | 233,369 (29.71 %) [29.61; 29.82] | 38,527 (28.88 %) [28.63; 29.12] | ||

| Other | 457,263 (58.22 %) [58.11; 58.33] | 87,662 (65.71 %) [65.45; 65.96] | ||

| Region | Midwest | 154,641 (20.03 %) [19.94; 20.11] | 27,671 (21.02 %) [20.80; 21.24] | |

| Northeast | 121,539 (15.74 %) [15.66; 15.82] | 21,698 (16.48 %) [16.28; 16.68] | ||

| South | 340,563 (44.10 %) [43.99; 44.21] | 53,167 (40.38 %) [40.12; 40.65] | ||

| West | 155,485 (20.13 %) [20.05; 20.22] | 29,123 (22.12 %) [21.90; 22.35] | ||

| ESRD case | Diabetes | 394,704 (51.25 %) [51.13; 51.36] | 65,199 (50.54 %) [50.27; 50.82] | |

| Hypertension | 206,324 (26.79 %) [26.69; 26.89] | 32,440 (25.15 %) [24.91; 25.39] | ||

| Other | 169,179 (21.97 %) [21.87; 22.06] | 31,355 (24.31 %) [24.07; 24.54] | ||

| Nephrology care pre ESRD | No | 199,619 (29.12 %) [29.02; 29.23] | 44,414 (39.48 %) [39.19; 39.76] | |

| Yes | 485,790 (70.88 %) [70.77; 70.98] | 68,090 (60.52 %) [60.24; 60.81] | ||

| Facility ownership | Chain | 586,132 (82.75 %) [82.67; 82.84] | 93,514 (78.36 %) [78.13; 78.60] | |

| Independent | 122,144 (17.25 %) [17.16; 17.33] | 25,820 (21.64 %) [21.40; 21.87] | ||

| Alcohol dependence | No | 766,783 (98.18 %) [98.15; 98.20] | 128,821 (97.20 %) [97.11; 97.29] | |

| Yes | 14,251 (1.82 %) [1.80; 1.85] | 3713 (2.80 %) [2.71; 2.89] | ||

| Drug dependence | No | 769,087 (98.47 %) [98.44; 98.50] | 129,560 (97.76 %) [97.67; 97.84] | |

| Yes | 11,947 (1.53 %) [1.50; 1.56] | 2974 (2.24 %) [2.16; 2.33] | ||

| Inability to ambulate | No | 740,830 (94.85 %) [94.80; 94.90] | 116,829 (88.15 %) [87.98; 88.32] | |

| Yes | 40,204 (5.15 %) [5.10; 5.20] | 15,705 (11.85 %) [11.68; 12.03] | ||

| Inability to transfer | No | 761,401 (97.49 %) [97.45; 97.52] | 123,211 (92.97 %) [92.83; 93.10] | |

| Yes | 19,633 (2.51 %) [2.48; 2.55] | 9323 (7.03 %) [6.90; 7.17] | ||

| Needing assistance in ADLs | No | 703,595 (90.09 %) [90.02; 90.15] | 108,278 (81.70 %) [81.49; 81.91] | |

| Yes | 77,439 (9.91 %) [9.85; 9.98] | 24,256 (18.30 %) [18.09; 18.51] | ||

| Patients per registered nurse | 17.05 [17.03; 17.07] | 16.36 [16.31; 16.40] | ||

| Patients per technician | 12.68 [12.65; 12.70] | 12.26 [12.22; 12.31] | ||

| Patients per social worker | 76.74 [76.66; 76.82] | 73.44 [73.25; 73.63] | ||

| Age | 57.46 [57.43; 57.48] | 60.86 [60.80; 60.92] |

Workers are part time or full time, at the facility level.

Abbreviations: ADLs: activity of daily living; ESRD: end-stage renal disease; CI: confidence interval.

Etiology and medical management of ESRD were also associated with whether patients would be reported to receive information: informed patients were more likely to have hypertensive nephropathy as the cause of ESRD, more likely to have pre-dialysis access to nephrology care, and more likely to receive dialysis at chain-owned centers. Finally, patients who were reported to be informed were less likely to live in the West, to have alcohol dependence, substance dependence, and limited functional status (West region 20 vs 22 %, CIs [20.05; 20.22] and [21.90; 22.35]; inability to ambulate 5 vs 12 %, CIs [5.10; 5.20] and [11.68; 12.03]; inability to transfer 3 vs 7 %, CIs [2.48; 2.55] and [6.90; 7.17]; needing assistance 10 vs 18 %, CIs and [9.85; 9.98] and [18.09; 18.51]).

3.2. Predictors of not being informed about transplant

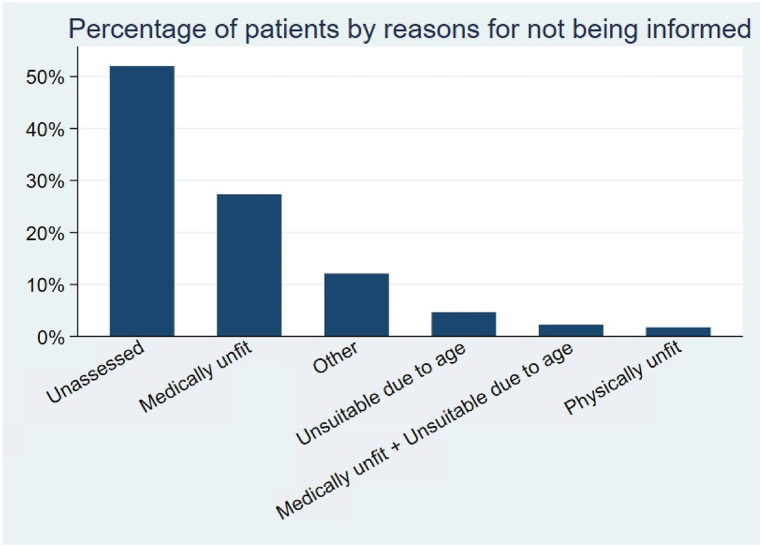

Overall, the most common reasons for not providing information about transplant were “not assessed” (52 %), followed by “medically unfit” (27 %) (Fig. 2). Table 3 provides estimates of logistic regressions in which we control for several patient characteristics (a complete list can be found in Table 1). Characteristics that were strongly associated with being unassessed were race, ethnicity, and dialysis center ownership: American Indian, Black, and Hispanic patients (ORs 1.60 [1.02; 1.32], 1.18 [1.14; 1.22], 1.30 [1.24; 1.37], respectively) and those undergoing dialysis at a chain facility (OR 1.45 [1.40; 1.50]) were more likely to be uninformed for an unspecified reason (i.e., “not assessed”). Differences also appeared across geographic locations, as patients in the South and West are more likely to be unassessed. Not receiving information about transplant for being medically unfit was associated with BMI >40, having Medicare as insurance, alcohol dependence, inability to ambulate, inability to transfer, needing assistance in activities of daily living, and being located in the Northeast (ORs 1.31[1.25; 1.36], 1.16 [1.08; 1.24], 1.48 [1.35; 1.62], 1.91 [1.79; 2.03], 1.55 [1.43; 1.67], 1.74 [1.67; 1.82] and 1.31 [1.25; 1.37], respectively). Being considered psychologically unfit was associated with Black race, being unemployed, drug dependence, needing assistance, and being unable to transfer (ORs 1.11 [1.02; 1.21], 2.54 [1.81; 3.57], 2.29 [1.94; 2.71], 2.90 [2.65; 3.18], and 1.18 [1.01; 1.38]). Being excluded from information due to advanced age was associated with being older, having Medicare, and being retired (ORs 1.31 [1.30; 1.32], 1.40 [1.13; 1.75] and 1.52 [1.16; 1.99]), as expected, but also with Asian race and Hispanic ethnicity (ORs 1.38 [1.19; 1.60] and 1.60 [1.47; 1.75]). Patients who declined to receive information were more likely to be white or American Indian, older than 70, retired, and to need assistance with activities of daily living.

Fig. 2.

Combinations of frequency of reasons for not being informed.

Common reasons for not receiving information about transplantation are reported above. As CMS 2728 form allows more than one option to be selected, the total does not equal 100 %. Less common reasons for not being informed (such as “patient refused” and different combinations of the options above) are not included in this graph.

Table 3.

Predictors of reasons for patients not being informed about kidney transplantation.

| Characteristics | Not informed | Medically unfit | Declined | Unsuitable due to age | Unassessed | Physically unfit | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol dependence | |||||||

| OR | 1.121 | 1.478 | 1.269 | 0.938 | 0.785 | 1.694 | 0.721 |

| 95 % CI | [1.069,1.176] | [1.348,1.620] | [0.907,1.775] | [0.716,1.227] | [0.718,0.859] | [1.428,2.011] | [0.611,0.851] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.164) | (0.639) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| Drug dependence | |||||||

| OR | 1.313 | 1.222 | 1.157 | 0.853 | 0.693 | 2.288 | 1.235 |

| 95 % CI | [1.245,1.385] | [1.096,1.363] | [0.749,1.787] | [0.503,1.447] | [0.626,0.766] | [1.935,2.706] | [1.059,1.439] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.512) | (0.556) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.007) |

| Inability to ambulate | |||||||

| OR | 1.341 | 1.906 | 1.147 | 0.960 | 0.632 | 0.857 | 0.862 |

| 95 % CI | [1.296,1.387] | [1.794,2.026] | [0.933,1.410] | [0.858,1.075] | [0.594,0.672] | [0.747,0.984] | [0.760,0.976] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.194) | (0.480) | (0.000) | (0.029) | (0.019) |

| Inability to transfer | |||||||

| OR | 1.348 | 1.546 | 0.728 | 1.005 | 0.673 | 1.182 | 0.890 |

| 95 % CI | [1.292,1.406] | [1.432,1.669] | [0.560,0.946] | [0.878,1.152] | [0.621,0.729] | [1.013,1.378] | [0.758,1.045] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.018) | (0.938) | (0.000) | (0.034) | (0.156) |

| Needs assistance | |||||||

| OR | 1.282 | 1.740 | 1.446 | 1.023 | 0.615 | 2.904 | 0.806 |

| 95 % CI | [1.252,1.313] | [1.666,1.818] | [1.247,1.677] | [0.946,1.106] | [0.589,0.642] | [2.648,3.184] | [0.739,0.878] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.569) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| Age at incidence | |||||||

| OR | 1.019 | 1.025 | 1.028 | 1.305 | 0.967 | 0.989 | 0.987 |

| 95 % CI | [1.019,1.020] | [1.023,1.027] | [1.021,1.036] | [1.295,1.315] | [0.966,0.969] | [0.985,0.993] | [0.984,0.989] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| Male | |||||||

| OR | 0.972 | 1.005 | 0.862 | 0.842 | 1.028 | 1.045 | 1.091 |

| 95 % CI | [0.958,0.987] | [0.975,1.037] | [0.772,0.962] | [0.797,0.889] | [0.999,1.057] | [0.968,1.129] | [1.036,1.149] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.740) | (0.008) | (0.000) | (0.062) | (0.259) | (0.001) |

| BMI over 40 | |||||||

| OR | 1.101 | 1.305 | 0.840 | 0.767 | 0.922 | 0.502 | 0.987 |

| 95 % CI | [1.077,1.125] | [1.249,1.364] | [0.709,0.995] | [0.697,0.846] | [0.885,0.961] | [0.438,0.577] | [0.915,1.064] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.044) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.735) |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| OR | 1.511 | 1.672 | 1.051 | 1.026 | 0.707 | 0.655 | 1.204 |

| 95 % CI | [1.412,1.616] | [1.397,2.001] | [0.603,1.831] | [0.755,1.393] | [0.611,0.819] | [0.465,0.923] | [0.933,1.554] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.861) | (0.870) | (0.000) | (0.016) | (0.154) |

| Glomerulonephritis | |||||||

| OR | 1.528 | 1.854 | 0.720 | 0.942 | 0.595 | 0.629 | 1.339 |

| 95 % CI | [1.423,1.642] | [1.536,2.237] | [0.393,1.318] | [0.679,1.306] | [0.509,0.694] | [0.434,0.912] | [1.025,1.749] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.287) | (0.719) | (0.000) | (0.014) | (0.032) |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| OR | 1.466 | 1.443 | 0.974 | 1.030 | 0.736 | 0.825 | 1.228 |

| 95 % CI | [1.369,1.569] | [1.203,1.730] | [0.556,1.706] | [0.757,1.401] | [0.635,0.854] | [0.584,1.165] | [0.949,1.589] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.925) | (0.851) | (0.000) | (0.274) | (0.118) |

| Other cause | |||||||

| OR | 2.294 | 3.574 | 0.815 | 0.681 | 0.349 | 0.548 | 1.468 |

| 95 % CI | [2.140,2.458] | [2.979,4.289] | [0.461,1.441] | [0.498,0.933] | [0.300,0.405] | [0.385,0.780] | [1.132,1.903] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.482) | (0.017) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.004) |

| Other urologic | |||||||

| OR | 1.814 | 2.614 | 0.811 | 0.984 | 0.464 | 1.139 | 1.325 |

| 95 % CI | [1.660,1.982] | [2.117,3.227] | [0.398,1.655] | [0.679,1.425] | [0.387,0.557] | [0.753,1.721] | [0.962,1.825] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.565) | (0.932) | (0.000) | (0.538) | (0.085) |

| Indwelling catheter | |||||||

| OR | 1.347 | 1.297 | 0.943 | 0.894 | 0.890 | 0.828 | 1.020 |

| 95 % CI | [1.317,1.377] | [1.235,1.363] | [0.799,1.113] | [0.828,0.965] | [0.852,0.929] | [0.732,0.936] | [0.940,1.107] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.488) | (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.635) |

| Graft | |||||||

| OR | 1.208 | 1.336 | 0.679 | 0.945 | 0.809 | 1.154 | 1.011 |

| 95 % CI | [1.153,1.266] | [1.210,1.475] | [0.454,1.015] | [0.807,1.107] | [0.738,0.885] | [0.923,1.442] | [0.849,1.204] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.059) | (0.486) | (0.000) | (0.208) | (0.898) |

| Other | |||||||

| OR | 1.452 | 1.041 | 0.963 | 0.622 | 0.929 | 0.404 | 1.453 |

| 95 % CI | [1.243,1.696] | [0.744,1.457] | [0.304,3.047] | [0.337,1.147] | [0.689,1.254] | [0.127,1.286] | [0.915,2.308] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.815) | (0.949) | (0.128) | (0.632) | (0.125) | (0.113) |

| Nephrologist care | |||||||

| OR | 0.752 | 0.989 | 0.878 | 1.085 | 1.035 | 0.759 | 0.869 |

| 95 % CI | [0.741,0.764] | [0.957,1.022] | [0.782,0.987] | [1.022,1.152] | [1.004,1.067] | [0.700,0.823] | [0.823,0.917] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.503) | (0.029) | (0.008) | (0.028) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| American Indian/Alaskan | |||||||

| OR | 0.923 | 0.829 | 1.428 | 0.999 | 1.159 | 0.753 | 1.053 |

| 95 % CI | [0.864,0.986] | [0.721,0.953] | [0.933,2.185] | [0.737,1.352] | [1.019,1.317] | [0.508,1.116] | [0.848,1.308] |

| p-value | (0.018) | (0.008) | (0.101) | (0.993) | (0.024) | (0.158) | (0.641) |

| Asian | |||||||

| OR | 0.830 | 0.718 | 0.865 | 1.380 | 1.060 | 0.974 | 1.354 |

| 95 % CI | [0.796,0.866] | [0.653,0.789] | [0.618,1.212] | [1.191,1.600] | [0.976,1.152] | [0.778,1.221] | [1.189,1.541] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.400) | (0.000) | (0.164) | (0.821) | (0.000) |

| Black | |||||||

| OR | 0.895 | 0.794 | 0.845 | 1.179 | 1.182 | 1.110 | 0.915 |

| 95 % CI | [0.880,0.911] | [0.765,0.824] | [0.736,0.970] | [1.101,1.261] | [1.142,1.224] | [1.017,1.213] | [0.858,0.976] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.017) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.020) | (0.007) |

| Hispanic | |||||||

| OR | 0.772 | 0.558 | 0.981 | 1.601 | 1.303 | 0.708 | 1.270 |

| 95 % CI | [0.754,0.790] | [0.529,0.589] | [0.821,1.173] | [1.466,1.747] | [1.244,1.365] | [0.619,0.809] | [1.178,1.370] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.834) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| Other | |||||||

| OR | 1.181 | 1.029 | 1.000 | 1.310 | 1.401 | 0.685 | 0.402 |

| 95 % CI | [0.965,1.444] | [0.680,1.557] | [1.000,1.000] | [0.621,2.765] | [0.942,2.085] | [0.212,2.220] | [0.148,1.094] |

| p-value | (0.106) | (0.893) | (.) | (0.478) | (0.096) | (0.529) | (0.075) |

| Pacific Islander | |||||||

| OR | 1.014 | 1.117 | 0.457 | 1.222 | 0.794 | 1.541 | 1.138 |

| 95 % CI | [0.943,1.090] | [0.961,1.299] | [0.203,1.030] | [0.880,1.699] | [0.691,0.911] | [1.104,2.150] | [0.911,1.422] |

| p-value | (0.706) | (0.150) | (0.059) | (0.231) | (0.001) | (0.011) | (0.256) |

| Medicaid | |||||||

| OR | 1.226 | 1.154 | 1.056 | 1.335 | 0.777 | 2.723 | 1.028 |

| 95 % CI | [1.187,1.266] | [1.073,1.242] | [0.808,1.381] | [1.024,1.741] | [0.728,0.829] | [2.176,3.407] | [0.923,1.144] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.688) | (0.033) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.614) |

| Medicare | |||||||

| OR | 1.135 | 1.156 | 0.895 | 1.404 | 0.764 | 1.812 | 1.007 |

| 95 % CI | [1.100,1.170] | [1.080,1.238] | [0.697,1.148] | [1.126,1.751] | [0.718,0.813] | [1.442,2.278] | [0.903,1.121] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.383) | (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.906) |

| Medicare&Medicaid | |||||||

| OR | 1.396 | 1.267 | 0.769 | 1.437 | 0.702 | 3.766 | 0.903 |

| 95 % CI | [1.352,1.442] | [1.182,1.359] | [0.593,0.996] | [1.149,1.796] | [0.659,0.748] | [3.023,4.690] | [0.807,1.010] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.047) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.074) |

| Medicare&Other | |||||||

| OR | 1.280 | 1.194 | 0.900 | 1.345 | 0.767 | 1.040 | 0.954 |

| 95 % CI | [1.236,1.325] | [1.110,1.286] | [0.691,1.173] | [1.076,1.681] | [0.716,0.821] | [0.801,1.351] | [0.843,1.080] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.437) | (0.009) | (0.000) | (0.769) | (0.458) |

| Other | |||||||

| OR | 1.189 | 1.036 | 1.018 | 1.564 | 0.853 | 1.339 | 1.108 |

| 95 % CI | [1.156,1.222] | [0.973,1.104] | [0.809,1.281] | [1.258,1.945] | [0.806,0.903] | [1.074,1.670] | [1.009,1.216] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.273) | (0.880) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.010) | (0.032) |

| Applying for Medicare | |||||||

| OR | 0.963 | 1.052 | 0.887 | 0.932 | 1.062 | 0.902 | 0.852 |

| 95 % CI | [0.947,0.979] | [1.017,1.088] | [0.789,0.997] | [0.882,0.985] | [1.029,1.096] | [0.829,0.982] | [0.805,0.901] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.044) | (0.013) | (0.000) | (0.018) | (0.000) |

| Employed part-time | |||||||

| OR | 1.031 | 1.241 | 1.222 | 1.384 | 0.779 | 1.017 | 1.258 |

| 95 % CI | [0.968,1.098] | [1.061,1.451] | [0.710,2.105] | [0.946,2.024] | [0.682,0.889] | [0.555,1.866] | [1.040,1.522] |

| p-value | (0.340) | (0.007) | (0.469) | (0.094) | (0.000) | (0.955) | (0.018) |

| Medical leave of absence | |||||||

| OR | 1.218 | 1.716 | 1.260 | 1.092 | 0.686 | 0.844 | 1.003 |

| 95 % CI | [1.157,1.283] | [1.517,1.941] | [0.797,1.990] | [0.682,1.750] | [0.615,0.764] | [0.486,1.467] | [0.851,1.182] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.323) | (0.713) | (0.000) | (0.548) | (0.975) |

| Other | |||||||

| OR | 1.079 | 1.355 | 1.388 | 2.125 | 0.802 | 0.511 | 0.593 |

| 95 % CI | [0.900,1.293] | [0.814,2.254] | [0.188,10.246] | [0.351,12.861] | [0.518,1.242] | [0.069,3.784] | [0.316,1.116] |

| p-value | (0.413) | (0.243) | (0.748) | (0.412) | (0.323) | (0.511) | (0.105) |

| Homemaker or Unemployed | |||||||

| OR | 1.396 | 1.505 | 1.057 | 1.124 | 0.706 | 2.542 | 1.113 |

| 95 % CI | [1.347,1.447] | [1.373,1.651] | [0.756,1.478] | [0.849,1.489] | [0.654,0.763] | [1.809,3.571] | [0.991,1.249] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.746) | (0.414) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.070) |

| Retired | |||||||

| OR | 1.429 | 2.008 | 1.280 | 1.515 | 0.614 | 2.361 | 0.780 |

| 95 % CI | [1.380,1.480] | [1.836,2.197] | [0.925,1.770] | [1.155,1.986] | [0.569,0.662] | [1.681,3.315] | [0.695,0.877] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.137) | (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| Chain dialysis facility | |||||||

| OR | 0.778 | 0.643 | 1.065 | 0.897 | 1.446 | 0.821 | 1.041 |

| 95 % CI | [0.764,0.792] | [0.621,0.667] | [0.931,1.217] | [0.840,0.958] | [1.396,1.496] | [0.752,0.896] | [0.978,1.109] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.358) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.206) |

| Northeast | |||||||

| OR | 0.951 | 1.306 | 0.837 | 0.485 | 0.877 | 1.357 | 0.886 |

| 95 % CI | [0.928,0.974] | [1.246,1.369] | [0.709,0.987] | [0.443,0.531] | [0.838,0.918] | [1.214,1.517] | [0.812,0.967] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.035) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.007) |

| South | |||||||

| OR | 0.954 | 0.797 | 0.746 | 0.901 | 1.249 | 0.818 | 1.001 |

| 95 % CI | [0.935,0.973] | [0.766,0.830] | [0.649,0.858] | [0.842,0.966] | [1.203,1.298] | [0.738,0.907] | [0.933,1.073] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.980) |

| West | |||||||

| OR | 1.168 | 0.801 | 0.758 | 0.669 | 1.306 | 0.822 | 1.129 |

| 95 % CI | [1.141,1.196] | [0.764,0.841] | [0.641,0.897] | [0.614,0.728] | [1.249,1.366] | [0.725,0.931] | [1.043,1.221] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.003) |

| Constant | |||||||

| OR | 0.026 | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 19.463 | 0.029 | 0.174 |

| 95 % CI | [0.024,0.028] | [0.023,0.037] | [0.002,0.008] | [0.000,0.000] | [16.069,23.574] | [0.017,0.049] | [0.127,0.239] |

| p-value | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

| Observations | 611211 | 91193 | 91074 | 91193 | 91193 | 91193 | 91193 |

| chi2 | 19851.5 | 13171.2 | 271.2 | 13634.0 | 11296.2 | 2415.9 | 1076.7 |

| chi2type | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR |

Abbreviation: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

3.3. Association between receiving information about transplant and time to waitlist and kidney transplant

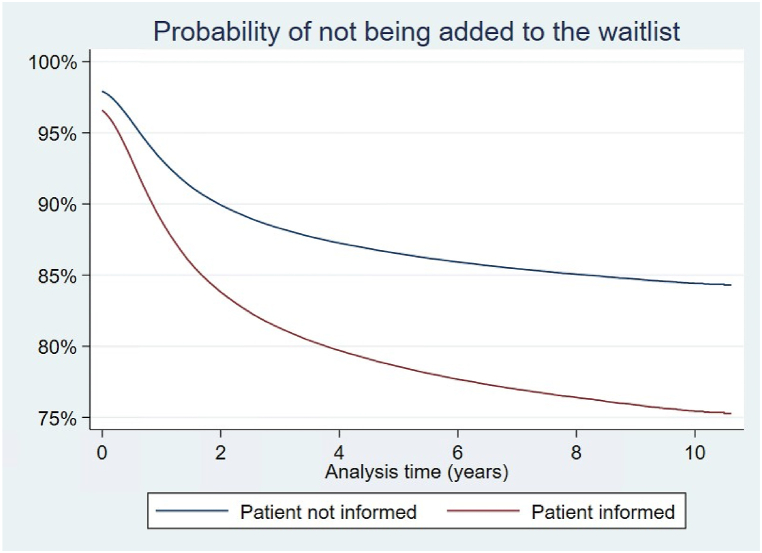

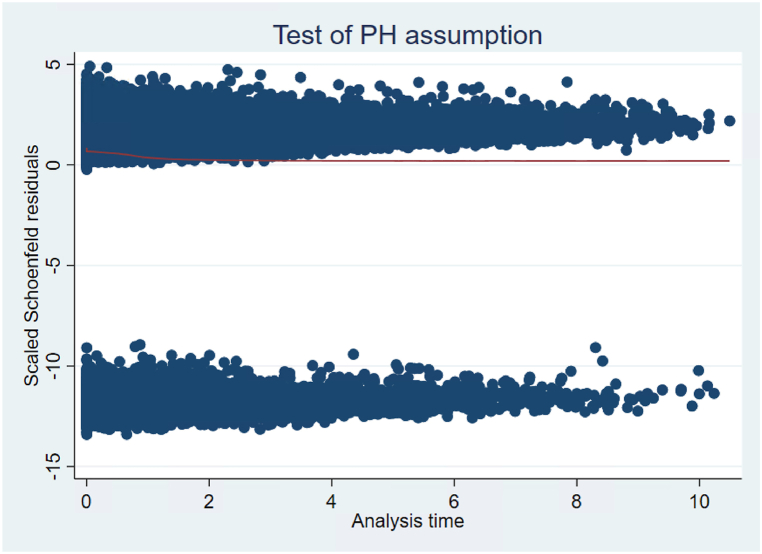

The goal of estimating Cox proportional-hazards models is to evaluate whether patients who are reported to receive transplant information get added to the waitlist or transplanted at a faster rate than non-informed patients while controlling for other relevant characteristics. Patients who were reported to be informed about transplant had a shorter time between ESRD onset and addition to the kidney transplant waitlist (hazard ratio 1.62 [1.58; 1.65], Table 4). This can be seen graphically in Fig. 3, which depicts adjusted survival curves based on regression estimates and the average covariate values in the study group. For example, the probability of not being added to the waitlist from the time the medical form is signed to year 2 is 84 % for someone who is informed and 90 % for someone who is not informed, holding other characteristics at their mean values. To verify the proportional hazard assumption, we ran a statistical test on scaled Schoenfeld residuals [17]; the test suggests that we should reject the assumption of proportionality. A visual investigation of the Schoenfeld residuals shows that the “cloud” of residuals is negatively sloped at early time points (Fig. 4), or that the model underpredicts the marginal effect of transplant information at early time points. This implies that transplant information is especially important soon after it is received. Male, white, Hispanic, and Asian patients waited shorter times to be added to the waitlist relative to Black patients. Unemployed, retired, and homemakers waited longer to be added to the waitlist.

Table 4.

Cox proportional-hazards model estimate of time to waitlist and time to transplant.

| Characteristics | Time to waitlist | Time to transplant |

|---|---|---|

| Patient informed | 1.617 | 1.032 |

| [1.582,1.652] | [0.999,1.067] | |

| (0.000) | (0.057) | |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.719 | 1.131 |

| [0.678,0.763] | [1.034,1.238] | |

| (0.000) | (0.007) | |

| Drug dependence | 0.361 | 0.892 |

| [0.335,0.389] | [0.795,1.002] | |

| (0.000) | (0.055) | |

| Inability to ambulate | 0.447 | 0.811 |

| [0.416,0.479] | [0.715,0.919] | |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Inability to transfer | 0.678 | 1.170 |

| [0.603,0.763] | [0.958,1.429] | |

| (0.000) | (0.123) | |

| Needs assistance | 0.603 | 0.894 |

| [0.582,0.625] | [0.842,0.949] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Age at incidence | 0.965 | 0.984 |

| [0.965,0.966] | [0.983,0.985] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Male | 1.138 | 1.024 |

| [1.124,1.152] | [1.005,1.043] | |

| (0.000) | (0.013) | |

| BMI over 40 | 0.428 | 0.782 |

| [0.418,0.438] | [0.754,0.811] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Diabetes | 0.455 | 0.787 |

| [0.443,0.468] | [0.759,0.816] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 0.664 | 1.050 |

| [0.644,0.684] | [1.011,1.091] | |

| (0.000) | (0.011) | |

| Hypertension | 0.495 | 0.891 |

| [0.481,0.509] | [0.858,0.925] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other cause | 0.415 | 1.070 |

| [0.401,0.430] | [1.024,1.118] | |

| (0.000) | (0.003) | |

| Other urologic | 0.454 | 0.888 |

| [0.427,0.483] | [0.819,0.963] | |

| (0.000) | (0.004) | |

| Indwelling catheter | 0.652 | 1.118 |

| [0.642,0.661] | [1.094,1.142] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Graft | 0.805 | 1.038 |

| [0.776,0.835] | [0.983,1.095] | |

| (0.000) | (0.179) | |

| Other | 0.750 | 1.241 |

| [0.667,0.842] | [1.062,1.451] | |

| (0.000) | (0.007) | |

| Nephrologist care | 1.499 | 1.041 |

| [1.477,1.521] | [1.019,1.064] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 0.794 | 0.659 |

| [0.748,0.842] | [0.600,0.724] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Asian | 1.476 | 0.672 |

| [1.436,1.517] | [0.645,0.700] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Black | 0.943 | 0.616 |

| [0.929,0.957] | [0.603,0.630] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Hispanic | 1.207 | 0.662 |

| [1.186,1.229] | [0.644,0.680] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other | 1.033 | 0.616 |

| [0.897,1.189] | [0.501,0.758] | |

| (0.652) | (0.000) | |

| Pacific Islander | 0.943 | 0.639 |

| [0.888,1.002] | [0.580,0.704] | |

| (0.057) | (0.000) | |

| Medicaid | 0.519 | 0.746 |

| [0.508,0.531] | [0.722,0.771] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Medicare | 0.534 | 0.806 |

| [0.521,0.548] | [0.775,0.838] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Medicare&Medicaid | 0.467 | 0.722 |

| [0.454,0.480] | [0.691,0.754] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Medicare&Other | 0.727 | 0.915 |

| [0.706,0.749] | [0.875,0.956] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other | 0.700 | 0.868 |

| [0.688,0.713] | [0.847,0.888] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Applying for Medicare | 1.032 | 1.038 |

| [1.017,1.047] | [1.016,1.061] | |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| Emp full-time | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| [1.000,1.000] | [1.000,1.000] | |

| (.) | (.) | |

| Emp partt-time | 0.961 | 0.993 |

| [0.932,0.992] | [0.952,1.036] | |

| (0.013) | (0.750) | |

| Medical leave of absence | 0.838 | 0.888 |

| [0.816,0.859] | [0.857,0.920] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other | 0.743 | 1.040 |

| [0.695,0.794] | [0.959,1.128] | |

| (0.000) | (0.345) | |

| Homemaker or Unemployed | 0.639 | 0.851 |

| [0.626,0.652] | [0.828,0.875] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Retired | 0.636 | 0.877 |

| [0.623,0.649] | [0.853,0.902] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Chain dialysis facility | 0.973 | 0.948 |

| [0.959,0.988] | [0.928,0.969] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Northeast | 1.340 | 0.794 |

| [1.315,1.366] | [0.773,0.816] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| South | 0.866 | 0.886 |

| [0.851,0.881] | [0.865,0.908] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| West | 1.007 | 0.753 |

| [0.987,1.027] | [0.732,0.775] | |

| (0.512) | (0.000) | |

| Observations | 478746 | 109048 |

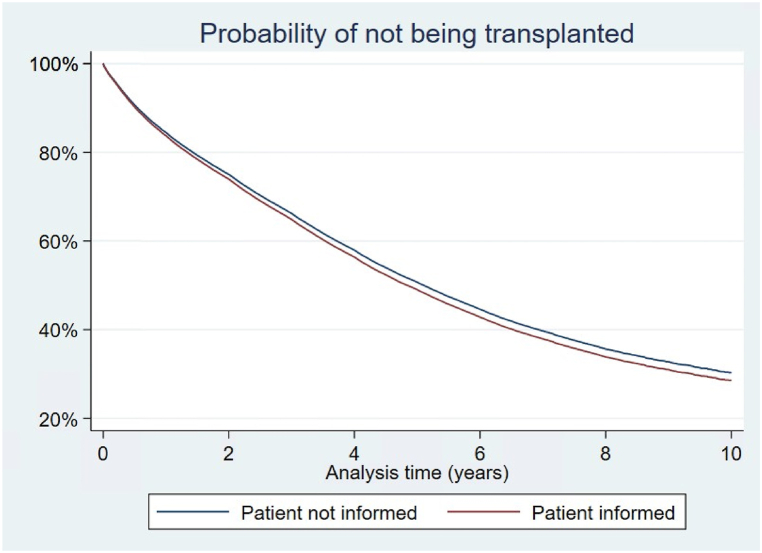

Fig. 3.

Probability of not being added to the waitlist by transplant information.

Cox proportional hazard regression demonstrated that patients who received transplant information were added to the waitlist at a faster rate than non informed patients. This is shown here as a survival curve, where the event was addition to the waitlist. The red line depicts the survival curve for informed patients, the blue line the survival curve for non informed patients.

Fig. 4.

Testing proportional hazards (PH) assumption for the variable “Patient Informed”.

The figure above shows a plot of scaled Schoenfeld residuals against time for the covariate “Patient informed”. Schoenfeld residuals can be thought of as the observed minus the expected values of the covariates at each failure time. As a rule of thumb, a non-zero slope is an indication of a violation of the proportional hazard assumption.

The time from addition to the waitlist to transplant was shorter for patients who received transplant information (see Fig. 5), male patients, patients with alcohol dependence, and patients with glomerulonephritis. Again, the proportionality assumption is rejected for the variable "Patient Informed" after conducting a test on Schoenfeld residuals, implying that the relative importance of the variable changes over time. Minority patients had significantly longer times on the waitlist prior to transplant (Black 38 %, Asian 33 %, Hispanic 34 %, Pacific Islanders 36 % reductions in the hazard of receiving a transplant relative to white). Homemakers, unemployed, and retired patients had longer times from listing to transplant. Similarly, patients on Medicare and/or Medicaid had longer times on the waitlist.

Fig. 5.

Probability of not being transplanted.

Cox proportional hazard regression demonstrated that patients who received transplant information were transplanted at a faster rate than non informed patients. This is shown here as a survival curve, where the event was receiving a kidney transplant. The red line depicts the survival curve for informed patients, the blue line the survival curve for non informed patients.

3.4. Dialysis center characteristics and access to information, waitlist, and transplant

Dialysis center ownership was a significant contributor to delivery of information to patients. A dialysis center is defined as chain dialysis center if it is owned by one of the two largest for-profit dialysis chains, DaVita and Fresenius, or by smaller chains; centers not affiliated to a chain were defined as “independent”. Patients who were reported to be informed about transplant were more likely to receive ESRD care at a chain dialysis center than non-informed patients (Table 2) (83 % vs 78 % CIs [82.67; 82.84] vs [78.13; 78.60]). Characteristics of the center itself were not associated significantly with whether patients would be informed, as a higher per-patient ratio of nurses, technicians, and social workers did not correspond to a higher reported number of patients informed (Table 2). The effect of chain ownership also translated into a lower number of patients waitlisted and transplanted in patients undergoing dialysis at a private facility (patients at a chain center were 3 % less likely to get listed (Table 4) and 5 % less likely to get transplanted (Table 4). These results are further corroborated by logit models estimated on the subset of independent facilities (Table 5). In these models, the dummy variable “Acquired” takes value 1 after an independent facility is acquired by a chain. The odds ratios associated with this variable suggest that the average incident patient is more likely to be informed after acquisition, but also less likely to be added to the waitlist. The coefficients do not change substantially after adding facility and/or time fixed effects to the models, suggesting robustness of these results across different specifications.

Table 5.

Logit model estimate of transplant information and addition to the waitlist (conditional on independent facilities).

| Characteristics | Not informed | Added to waitlist |

|---|---|---|

| Acquired | 0.322 | 0.711 |

| [0.257,0.404] | [0.588,0.861] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.020 | 0.756 |

| [0.929,1.120] | [0.673,0.851] | |

| (0.678) | (0.000) | |

| Drug dependence | 1.645 | 0.270 |

| [1.492,1.814] | [0.232,0.314] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Inability to ambulate | 1.481 | 0.409 |

| [1.386,1.583] | [0.357,0.468] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Inability to transfer | 1.339 | 0.508 |

| [1.235,1.452] | [0.409,0.632] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Needs assistance | 1.263 | 0.543 |

| [1.206,1.323] | [0.507,0.582] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Age at incidence | 1.018 | 0.948 |

| [1.017,1.020] | [0.946,0.949] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Male | 0.980 | 1.177 |

| [0.950,1.010] | [1.141,1.215] | |

| (0.185) | (0.000) | |

| BMI over 40 | 1.085 | 0.372 |

| [1.037,1.134] | [0.352,0.393] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Diabetes | 1.655 | 0.292 |

| [1.435,1.907] | [0.268,0.318] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 1.774 | 0.555 |

| [1.528,2.061] | [0.505,0.610] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Hypertension | 1.564 | 0.346 |

| [1.354,1.807] | [0.317,0.378] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other cause | 2.845 | 0.248 |

| [2.460,3.289] | [0.225,0.273] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other urologic | 2.117 | 0.274 |

| [1.769,2.534] | [0.235,0.319] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Indwelling catheter | 1.381 | 0.523 |

| [1.317,1.447] | [0.503,0.543] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Graft | 1.206 | 0.742 |

| [1.087,1.339] | [0.675,0.815] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other | 1.358 | 0.588 |

| [0.976,1.890] | [0.427,0.809] | |

| (0.069) | (0.001) | |

| Nephrologist care | 0.752 | 1.627 |

| [0.727,0.776] | [1.570,1.687] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 0.964 | 0.736 |

| [0.859,1.081] | [0.646,0.838] | |

| (0.528) | (0.000) | |

| Asian | 0.686 | 2.110 |

| [0.631,0.746] | [1.967,2.263] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Black | 0.853 | 1.048 |

| [0.822,0.885] | [1.009,1.088] | |

| (0.000) | (0.014) | |

| Hispanic | 0.681 | 1.495 |

| [0.649,0.716] | [1.428,1.564] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other | 0.841 | 1.531 |

| [0.555,1.274] | [1.056,2.219] | |

| (0.414) | (0.025) | |

| Pacific Islander | 0.956 | 1.107 |

| [0.817,1.119] | [0.947,1.294] | |

| (0.574) | (0.202) | |

| Medicaid | 1.202 | 0.427 |

| [1.122,1.287] | [0.404,0.452] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Medicare | 1.238 | 0.455 |

| [1.158,1.324] | [0.427,0.484] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Medicare&Medicaid | 1.423 | 0.380 |

| [1.331,1.523] | [0.356,0.406] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Medicare&Other | 1.240 | 0.664 |

| [1.155,1.330] | [0.622,0.710] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other | 1.337 | 0.651 |

| [1.261,1.418] | [0.622,0.681] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Applying for Medicare | 0.927 | 1.050 |

| [0.894,0.960] | [1.011,1.091] | |

| (0.000) | (0.011) | |

| Emp pt-time | 1.114 | 0.876 |

| [0.984,1.262] | [0.804,0.955] | |

| (0.089) | (0.003) | |

| Medical leave of absence | 1.376 | 0.761 |

| [1.238,1.529] | [0.706,0.819] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Other | 1.073 | 0.863 |

| [0.745,1.545] | [0.677,1.100] | |

| (0.705) | (0.234) | |

| Homemaker or Unemployed | 1.496 | 0.512 |

| [1.388,1.613] | [0.485,0.540] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Retired | 1.554 | 0.500 |

| [1.444,1.672] | [0.474,0.527] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Chain dialysis facility | 1.771 | 1.031 |

| [1.407,2.230] | [0.850,1.251] | |

| (0.000) | (0.757) | |

| Northeast | 0.962 | 1.364 |

| [0.922,1.004] | [1.307,1.422] | |

| (0.074) | (0.000) | |

| South | 0.797 | 0.783 |

| [0.765,0.831] | [0.750,0.816] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| West | 1.379 | 0.924 |

| [1.317,1.444] | [0.880,0.970] | |

| (0.000) | (0.002) | |

| Constant | 0.023 | 59.517 |

| [0.019,0.028] | [51.989,68.135] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Observations | 133888 | 133891 |

| chi2 | 7202.1 | 28885.0 |

| chi2type | LR | LR |

4. Discussion

In our retrospective analysis of 944,015 patients who initiated dialysis between 2008 and 2019, we found that 14.52 % did not receive information about kidney transplant at the time of dialysis initiation. Of these, 52 % were not assessed for an unknown reason, and 27 % were deemed medically unfit by the nephrologist managing dialysis. Irrespective of receiving information about transplant options, racial and ethnic minorities, unemployed, and publicly insured patients had longer wait times to transplant. Patients who were reported to be informed about kidney transplant were more likely to be added to the transplant waitlist (HR 1.62). Our findings demonstrate an improvement in the reported provision of transplant education since the work by Kucirka, who reported 69.9 % patients were informed between 2005 and 2007 [18]. Our results parallel the findings of Ku and colleagues, who recently reported that among ESRD patients, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients had fewer medical contraindications to transplant but were relatively less likely to receive a kidney transplant than non-Hispanic White patients [19].

Policy initiatives implemented during the study period may account for the improvement in access to information about kidney transplant at dialysis initiation. The Kidney Allocation System (KAS) was implemented in December 2014 with the goal of increasing graft survival by matching recipients with low expected post-transplant survival (EPTS) with kidneys with lower donor profile index (KDPI). KAS also changed the initiation of waitlist time to the start date of dialysis (compared to the date of waitlisting before KAS); this may account for differences in information provided, as after KAS implementation there is less urgency to refer a viable candidate to a transplant center as soon as possible. Additionally, it is possible that increased insurance coverage following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 may have decreased barriers related to insurance status, as suggested by studies that correlated ACA implementation and pre-emptive kidney transplant listing [20,21]. Multiple initiatives have been implemented over the last two decades to improve access, quality, and equity in kidney transplantation (KAS, ACA, Kidney Care Quality Alliance, among others) and the overall trend of improved information observed by us, is possibly a byproduct of these initiatives. Despite this, we found that patients with Medicare and/or Medicaid were less likely to be informed about transplant, and patients with private insurance were more likely to be reported to receive information about kidney transplant and access to the waitlist and transplant (while controlling for several socioeconomic characteristics) [[22], [23], [24]]. Older and female patients as well as racial and ethnic minorities spent a longer time on the waitlist, demonstrating that for some minorities the barriers to transplant are complex and not entirely overcome by gaining access to the waitlist [25].

The focus of our study was to investigate provision of information about kidney transplant as reported to CMS. In our opinion, all patients with ESRD should receive this information, in accordance with CMS policy. Whether all patients should be referred to a transplant center is a subject of intense debate. Although not all ESRD patients are transplant candidates, the wide variation in eligibility criteria among US centers suggests that subjective assessments may be contributing to the disparity. Some authors have proposed an “opt-out” model as a way to reduce disparities in access to transplant [26]. Others have argued against default referrals, noting that these would increase cost and inefficiencies for transplant centers [27]. Reconciling these opposite arguments would be important to optimize referral of viable candidates while reducing disparities in access to transplant.

It is important to note how the persistent disparities in access to information mostly result from providers' choices, as only a small percentage of patients (less than 2 % in all groups) declined information about kidney transplant. Although some groups were more likely to decline information (female, white, retired), their overall percentage remained small, indicating that not receiving information about transplant does not reflect an intentional decision by patients, but more commonly stems from providers’ assessments of perceived barriers to transplant. Still, gender, age, employment status, type of insurance, type of dialysis center, and pre-dialysis nephrology care were all associated with the reported receipt of information about kidney transplant, as indicated on the CMS-2728 form. The fact that most patients were excluded from receiving information for a “not assessed” reason suggests that the decision not to inform patients may have been taken after a less comprehensive evaluation. Even when a reason for exclusion was specified, it did not necessarily stem from an accurate evaluation of the patient. For example, of patients who were unable to ambulate, only 30.1 % were not informed because they were deemed medically unfit. Future modifications to the CMS 2728 form may be helpful to capture specific clinical contraindications to the provision of transplant information, and minimize the number of patients who were “not assessed”. Another explanation for the high rate of non-assessment is lack of time, and prior studies have found that nephrologists treating predominantly Black, elderly, and Medicaid-insured patients report insufficient time as the primary barrier to transplant education [28]. To ensure fairness in the referral process and to decrease provider bias, some authors have proposed an opt-out referral model as a solution, although this is a subject of debate [26]. Finally, it is impossible to evaluate from our data the influence that specific transplant centers may have on provision of transplant information. Different transplant centers have heterogeneous standards on what patients should be referred for evaluation. The relationship between transplant centers and dialysis facilities is a complex one, but it is conceivable that transplant center policies may influence reported provision of transplant education at the dialysis center level. Appropriate referral of patients for transplant may be aided by more transparent disclosure of transplant center candidacy criteria.

We also found that dialysis center ownership was associated with reported provision of information about transplant to ESRD patients. Patients undergoing dialysis at chain facilities were more likely to be reported to have received information compared to patients treated at independent facilities, but this did not lead to higher rates of waitlisting and transplant. Moreover, independent facilities acquired by chain facilities change their practices considerably, as patients become more likely to be informed but less likely to be added to the waitlist after acquisition. Our finding suggests that, rather than differences in patient populations, chain units provide a lower quality of transplant education, as our analysis controls for several medical and socioeconomic patient characteristics. That chains are more likely to inform patients of transplant options but less likely to place patients on the waitlist is consistent with prior work that found chain ownership comes with firm-wide standards (e.g., operation manuals that dictate treatment protocols) but also causes waitlist and transplant rates to fall; chains’ explicit mandate to maximize profits may lead them to sacrifice patient outcomes in favor of higher reimbursements [29]. Of note, patients who were reported to have received information about transplant were treated in facilities with a slightly lower number of nurses and social workers when compared to patients who did not receive information, as well as higher patient-to-nurse and patient-to-technician ratios. These results are in contrast to a recent publication indicating that a lower patient-to-staff ratio is more likely to be associated with transplant education [30].

Our study has several additional policy implications. With very limited exceptions, all patients with ESRD should receive access to information about kidney transplant. Ideally, this would occur well before initiation of dialysis, as pre-emptive transplant is the most-preferred renal replacement therapy and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) recommends referral to a transplant center when GFR approaches 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.[31] The purpose of the expanded reimbursement for transplant education and the accompanying change to the CMS-2728 form was to ensure patients are educated about their options for managing ESRD. These options include transplantation, and provision of education about transplant as an option does not require—and we argue should not include—an assessment of whether the patient is a suitable candidate for transplant, as initiation of renal replacement therapy is not the appropriate setting for a specialized screening. This is especially important considering a recent study showing that dialysis providers themselves had limited knowledge of barriers to transplant [32].

It is likely that the CMS-2728 form falls short of its intended purpose—to ensure timely receipt of information about transplant for patients. One key component of the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) Initiative is the performance payment adjustment, a positive or negative payment adjustment based on home dialysis rate and transplant rate [33]. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation additionally will expand the use of the kidney disease education benefit to CKD stage 5. These initiatives lend credence to the previously established idea that progression of kidney disease occurs over time and that education about options for renal replacement therapy, including transplant, should happen at an earlier stage in the disease process. While our study does not include data collected after implementation of the AAKH, it is possible that trends observed reflect an anticipatory effect of the larger public sentiment related to advancing equity in access to transplant. Although our research focused on Form 2728 as a way to quantify delivery of information about transplant and the disparities associated with it, the associated time point of 45 days after initiation of dialysis is probably not the most appropriate. Information about transplant should ideally be completed earlier, although this would require a shift from the current policy system, where Form 2728 is the latest checkpoint at which all patients should be informed about transplant. Moreover, our analysis sheds light on differences in attitudes towards transplant information between chain and independent facilities. In fact, policy actions should account for facility ownership differences and ensure that chain protocols do not impede higher information rates to translate into higher waitlist and transplant rates.

Some limitations apply to our study. This was an observational analysis based on the CMS-2728 Form as part of the USRDS and is therefore subject to the limitations of large registry data reporting. Moreover, there may be inaccuracies in the way in which certain variables on the CMS-2728 Form are coded [34]. CMS-2728 forms are often filled by ancillary staff and this may limit the accuracy of the data reported. We limited our focus to documenting which patients were reported to receive information about kidney transplant—and did not study directly which patients received access to kidney transplant—based on the assumption that every patient with ESRD should be informed and that the evaluation and candidacy determination should be managed by transplant centers. In addition, the concept of receiving education about kidney transplant is vague, and there may be differences in what information is provided to patients as well as what information is actually retained by them [30]; a recent study found that a significant proportion of patients informed about kidney transplant by their physicians did not recall receiving the information [35]. Moreover, we did not assess disparities in pre-emptive listing, and it is also likely that patients may receive information about transplant from sources other than the provider responsible for form CMS-2728 submission. Finally, our data did not exclude patients with a prior kidney transplant. Although these represent a small subset of the database analyzed, it is possible that their information practices may differ from first-time dialysis patients.

The decision not to inform a patient about kidney transplant is an important one, as it is associated with decreased rates of access to the waitlist and transplant. It should not be taken lightly. Transplant centers should be entrusted with screening and evaluating patients for transplant. More patient referrals to transplant centers could motivate patients with modifiable barriers to transplant to overcome them and increase the number of patients listed and ultimately transplanted.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

The data used in the study are confidential data from the USRDS, which can be requested through a Data Use Agreement at usrds.org.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Vincenzo Villani: Conceptualization. Luca Bertuzzi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Gabriel Butler: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Paul Eliason: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. James W. Roberts: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Nicole DePasquale: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Christine Park: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Lisa M. McElroy: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Ryan C. McDevitt: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

“All results are robust to estimating a multinomial logit specification.”

References

- 1.Abecassis M., Bartlett S.T., Collins A.J., et al. Kidney transplantation as primary therapy for end-stage renal disease: a national kidney foundation/kidney disease outcomes quality initiative (NKF/KDOQITM) conference. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Mar 2008;3(2):471–480. doi: 10.2215/cjn.05021107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier-Kriesche H.U., Kaplan B. Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: a paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation. Nov 27 2002;74(10):1377–1381. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe R.A., Ashby V.B., Milford E.L., et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N. Engl. J. Med. Dec 2 1999;341(23):1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/nejm199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCullough K.P., Morgenstern H., Saran R., Herman W.H., Robinson B.M. Projecting ESRD incidence and prevalence in the United States through 2030. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Jan 2019;30(1):127–135. doi: 10.1681/asn.2018050531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Combes G., Sein K., Allen K. How does pre-dialysis education need to change? Findings from a qualitative study with staff and patients. BMC Nephrol. Nov 23 2017;18(1):334. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0751-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devins G.M., Mendelssohn D.C., Barré P.E., Binik Y.M. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention and coping styles influence time to dialysis in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Oct 2003;42(4):693–703. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devins G.M., Mendelssohn D.C., Barré P.E., Taub K., Binik Y.M. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention extends survival in CKD: a 20-year follow-up. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Dec 2005;46(6):1088–1098. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golper T.A. Predialysis nephrology care improves dialysis outcomes: now what? Or chapter two. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;2(1):143. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03711106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkelstein F.O., Story K., Firanek C., et al. Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int. 2008;74(9):1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPherson L.J., Hamoda R.E., Patzer R.E. Measuring patient knowledge of kidney transplantation: an initial step to close the knowledge gap. Transplantation. Mar 2019;103(3):459–460. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skelton S.L., Waterman A.D., Davis L.A., Peipert J.D., Fish A.F. Applying best practices to designing patient education for patients with end-stage renal disease pursuing kidney transplant. Prog. Transplant. Mar 2015;25(1):77–84. doi: 10.7182/pit2015415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waterman A.D., Morgievich M., Cohen D.J., et al. Living donor kidney transplantation: improving education outside of transplant centers about live donor transplantation--recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Sep 4 2015;10(9):1659–1669. doi: 10.2215/cjn.00950115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gander J.C., Zhang X., Plantinga L., et al. Racial disparities in preemptive referral for kidney transplantation in Georgia. Clin. Transplant. Sep 2018;32(9) doi: 10.1111/ctr.13380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myaskovsky L., Almario Doebler D., Posluszny D.M., et al. Perceived discrimination predicts longer time to be accepted for kidney transplant. Transplantation. Feb 27 2012;93(4):423–429. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318241d0cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng F.L., Joffe M.M., Feldman H.I., Mange K.C. Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Oct 2005;46(4):734–745. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schold J.D., Mohan S., Huml A., et al. Failure to advance access to kidney transplantation over two decades in the United States. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Feb 11 2021;32(4):913–926. doi: 10.1681/asn.2020060888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grambsch P.M., Therneau T.M. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515–526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kucirka L.M., Grams M.E., Balhara K.S., Jaar B.G., Segev D.L. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. Feb 2012;12(2):351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ku E., Lee B.K., McCulloch C.E., et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in kidney transplant access within a theoretical context of medical eligibility. Transplantation. Jul 2020;104(7):1437–1444. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harhay M.N., McKenna R.M., Boyle S.M., et al. Association between Medicaid expansion under the affordable care Act and preemptive listings for kidney transplantation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Jul 6 2018;13(7):1069–1078. doi: 10.2215/cjn.00100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harhay M.N., McKenna R.M., Harhay M.O. Association between Medicaid expansion under the affordable care Act and medicaid-covered pre-emptive kidney transplantation. J. Gen. Intern. Med. Nov 2019;34(11):2322–2325. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05279-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansen K.L., Zhang R., Huang Y., Patzer R.E., Kutner N.G. Association of race and insurance type with delayed assessment for kidney transplantation among patients initiating dialysis in the United States. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Sep 2012;7(9):1490–1497. doi: 10.2215/cjn.13151211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keith D., Ashby V.B., Port F.K., Leichtman A.B. Insurance type and minority status associated with large disparities in prelisting dialysis among candidates for kidney transplantation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Mar 2008;3(2):463–470. doi: 10.2215/cjn.02220507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patzer R.E., Perryman J.P., Pastan S., et al. Impact of a patient education program on disparities in kidney transplant evaluation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Apr 2012;7(4):648–655. doi: 10.2215/cjn.10071011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vranic G.M., Ma J.Z., Keith D.S. The role of minority geographic distribution in waiting time for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. Nov 2014;14(11):2526–2534. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huml A.M., Sedor J.R., Poggio E., Patzer R.E., Schold J.D. An opt-out model for kidney transplant referral: the time has come. Am. J. Transplant. Jan 2021;21(1):32–36. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng X.S., Han J., Braggs-Gresham J.L., et al. Trends in cost attributable to kidney transplantation evaluation and waiting list management in the United States, 2012-2017. JAMA Netw. Open. Mar 1 2022;5(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balhara K.S., Kucirka L.M., Jaar B.G., Segev D.L. Disparities in provision of transplant education by profit status of the dialysis center. Am. J. Transplant. Nov 2012;12(11):3104–3110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eliason P.J., Heebsh B., McDevitt R.C., Roberts J.W. How acquisitions affect firm behavior and performance: evidence from the dialysis industry. Q. J. Econ. 2019;135(1):221–267. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjz034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch-Weser S., Porteny T., Rifkin D.E., et al. Patient education for kidney failure treatment: a mixed-methods study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Nov 2021;78(5):690–699. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.02.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network. Educational Guidance on Patient Referral to Kidney Transplantation. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/professionals/by-topic/guidance/educational-guidance-on-patient-referral-to-kidney-transplantation/.

- 32.Waterman A.D., Peipert J.D., Goalby C.J., Dinkel K.M., Xiao H., Lentine K.L. Assessing transplant education practices in dialysis centers: comparing educator reported and Medicare data. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Sep 4 2015;10(9):1617–1625. doi: 10.2215/cjn.09851014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kidney Care Choices Model. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/kidney-care-choices-kcc-model.

- 34.Bowling C.B., Zhang R., Franch H., et al. Underreporting of nursing home utilization on the CMS-2728 in older incident dialysis patients and implications for assessing mortality risk. BMC Nephrol. Mar 21 2015;16:32. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0021-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salter M.L., Orandi B., McAdams-DeMarco M.A., et al. Patient- and provider-reported information about transplantation and subsequent waitlisting. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Dec 2014;25(12):2871–2877. doi: 10.1681/asn.2013121298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study are confidential data from the USRDS, which can be requested through a Data Use Agreement at usrds.org.