Abstract

Porcine xenografts may offer a solution to the shortage of human donor allografts. However, all pigs contain the porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV), raising concerns regarding the transmission of PERV and the possible development of disease in xenotransplant recipients. We evaluated 11 antiretroviral drugs licensed for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) therapy for their activities against PERV to assess their potential for clinical use. Fifty and 90% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s and IC90s, respectively) of five nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTIs) were determined enzymatically for PERV and for wild-type (WT) and RTI-resistant HIV-1 reference isolates. In a comparison of IC50s, the susceptibilities of PERV RT to lamivudine, stavudine, didanosine, zalcitabine, and zidovudine were reduced >20-fold, 26-fold, 6-fold, 4-fold, and 3-fold, respectively, compared to those of WT HIV-1. PERV was also resistant to nevirapine. Tissue culture-based, single-round infection assays using replication-competent virus confirmed the relative sensitivity of PERV to zidovudine and its resistance to all other RTIs. A Gag polyprotein-processing inhibition assay was developed and used to assess the activities of protease inhibitors against PERV. No inhibition of PERV protease was seen with saquinavir, ritonavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, or amprenavir at concentrations >200-fold the IC50s for WT HIV-1. Thus, following screening of many antiretroviral agents, our findings support only the potential clinical use of zidovudine.

The use of transplants from animal origin offers a potential solution to the limited supply of human organs and tissues. Pigs are presently the preferred source for xenotransplantation for a variety of practical and safety reasons, including availability, comparable organ size, and possibility of genetic manipulation to overcome rejection by the recipient's immune system. Clinical trials involving pig xenografts have included (i) perfusion with pig livers or porcine hepatocytes as a bridging strategy for hepatic failure, (ii) the use of pancreatic islet cells as a treatment for chronic diabetes, and (iii) the implantation of fetal neuronal tissue as a therapy for Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases (5, 10, 11, 17, 47, 39). Proposed future therapies include the use of solid organs from pigs.

A major concern surrounding porcine xenotransplantation is the exposure of xenograft recipients to the porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV). PERV is a C-type retrovirus that is permanently integrated, in multiple copies, in the pig genome (23, 33). Infectious PERV particles are released from a variety of porcine cells, including peripheral blood mononuclear cells, endothelial cells, pancreatic islets, and some kidney cell lines (22, 26, 33, 50). PERV has three envelope classes (PERV-A, -B, and -C) that have been shown to have distinct receptor specificity and in vitro tropism (43, 51). However, their protease and reverse transcriptase (RT) sequences are indistinguishable (1).

Concerns regarding transmission of PERV to humans were heightened when PERV derived from either porcine cell lines or primary cells was shown to infect some human cells (26, 33, 50). In a severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model, Laan et al. demonstrated recently the ability of porcine pancreatic islet cells to transmit PERV infection, providing the first evidence for a xenogenic PERV infection (22). However, evidence of PERV infection has not been seen thus far in retrospective studies of patients who had received either extracorporeal porcine splenic, liver, or kidney perfusion; porcine skin grafts; or porcine pancreatic islet cell transplants (19, 24, 31, 32, 39). While reassuring, these data do not fully define risks of PERV transmission to exposed humans because of our limited ability to extrapolate these findings to other types of xenotransplants, particularly those involving whole organs. The risk that any xenograft recipients may become infected with PERV is likely to be a function of several factors associated with the xenograft (e.g., cellular or solid organs, transgenic or nontransgenic animal, duration of the xenograft, etc.), the xenotransplantation technique, and the recipient's characteristics (e.g., immunosuppression, levels of xenoantibody, etc.).

Infections with C-type retroviruses have been associated with different outcomes, ranging from benign to neoplastic and neurologic diseases (8). While the risk that PERV-infected persons will develop disease and will require antiretroviral therapy is still unknown, it is prudent to identify drugs that are active against PERV. Such drugs will be available should a need to treat PERV-infected persons arises.

In this study, we have evaluated the susceptibility of PERV to 11 inhibitors licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). These inhibitors included six RT inhibitors (RTIs) and five protease inhibitors (PIs). We provide evidence of sensitivity of PERV to zidovudine and poor or no susceptibility to all other drugs.

RT susceptibility analysis by an enzymatic assay.

The susceptibility of PERV RT to the RTIs was evaluated enzymatically in the Amp-RT assay to determine the 50 and 90% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s and IC90s, respectively) (20, 52). Results obtained in triplicate were compared with those determined from reference wild-type (WT) and drug-resistant HIV-1 isolates using methodologies previously described (15, 49). The RTIs tested were nevirapine; the triphosphorylated nucleoside analogs of zidovudine (AZT-TP), lamivudine (2′,3′-deoxy-3′-thiacytidine; 3TC-TP), zalcitabine (dideoxycytosine [ddC]-TP), stavudine (2′,3′-didehydro-3′-deoxythymidine; d4T-TP), and the active form of didanosine (dideoxyadenine [ddA]-TP). The ratios of nucleoside analogs to their corresponding deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) in the RT reaction of the Amp-RT assay varied, with 15 μM dTTP being used for reaction mixtures containing AZT-TP or d4T-TP, 5 μM dCTP being used for mixtures containing 3TC-TP or ddC-TP, and 5 μM dATP being used for mixtures containing dd-ATP along with 20 μM concentrations of each of the other three dNTPs. For nevirapine reactions, a 20 μM dNTP mixture was used. AZT-TP was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals, Inc. (Brea, Calif.), ddC-TP and ddA-TP were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.), d4T-TP was kindly provided by Anne-Mieke Vandamme (Rega Institute for Medical Research and University Hospitals, Leuven, Belgium), and 3TC-TP and nevirapine were provided by R. F. Schinazi (Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Emory University, Atlanta, Ga.).

Two sources of PERV were used, the first from culture supernatant of a porcine embryonic kidney cell line (PK15) and the second from PERV-infected human embryonic kidney cell line 293 (PERV-293) (33). PK15 and PERV-293 cells, which release both PERV-A and -B (23), were maintained in minimal essential medium by using standard tissue culture techniques. Three HIV-1 isolates derived from molecular infectious clones containing WT RT, HIV-1SUM9 (40), and xxHIV-1LAI (30) or HIV-1xxBRUpitt (37) were used as reference WT HIV-1 isolates. HIV-1 isolates derived from three molecular infectious clones containing one to five multidideoxynucleoside-resistant (MDR) mutations were used as reference viruses that have different levels of resistance: HIV-1SUM8 (Q151M) has low-level resistance, and HIV-1SUM12 (F77L, F116V, Q151M) and HIV-1SUM13 (A62V, V75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M) have higher levels of resistance (40, 48).

The IC50s and IC90s of RTIs for PERV, WT HIV-1, and drug-resistant HIV-1 are shown in Table 1. As expected, all the MDR HIV-1 isolates had reduced susceptibility to all the nucleoside analogs. The level of resistance was lower with HIV-1SUM8 containing Q151M than with HIV-1SUM12 and HIV-1SUM13, which contained additional MDR mutations. These data are consistent with previous findings on these viruses (40, 48). Table 1 also shows that, in comparison to WT HIV-1, both PERV isolates had reduced susceptibilities to all five nucleoside RTIs. However, the level of resistance varied among the drugs. No activity was seen with lamivudine, while high-level resistance was observed with stavudine. The susceptibility of PERV to both zalcitabine and didanosine was also reduced compared to that of WT HIV-1. The highest activity against PERV RT was observed with zidovudine, with which there was only a threefold difference in IC50 from that for WT HIV-1. This level of resistance was lower than that of HIV-1SUM8 (Q151M).

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of the enzymatic activity of PERV RT to various RTIs and comparison with WT and drug-resistant HIV-1a

| Virus (mutation[s]) | AZT-TP

|

ddC-TP

|

3TC-TP

|

ddA-TP

|

d4T-TP

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | IC90 | IC50 | IC90 | IC50 | IC90 | IC50 | IC90 | IC50 | IC90 | |

| WT HIV-1 | ||||||||||

| HIV-1SUM9 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.055 | 0.1 |

| HIV-1LAI | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.015 | 0.05 |

| HIV-1xxBRUpitt | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | ND | ND |

| MDR HIV-1 | ||||||||||

| HIV-1SUM8 (Q151M) | 2.5 (5) | 4.5 (4.7) | 1.8 (3.6) | 4.3 (4.8) | 0.9 (1.8) | 2.8 (2.5) | 1.2 (6.5) | 3.8 (6.8) | 0.32 (9.1) | 0.85 (11.3) |

| HIV-1SUM12 (F77L, F116Y, Q151M) | 11 (22) | 18 (19) | 6 (12) | 15 (16.7) | 2.7 (5.4) | 6.8 (6.2) | 1.1 (5.9) | 4 (7.1) | 0.37 (10.6) | 1.3 (17.3) |

| HIV-1SUM13 (A62V, V75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M) | 18 (36) | 45 (47.4) | 7.5 (15) | 15 (16.7) | 3.3 (6.6) | 8.2 (7.5) | 6 (32.4) | 11 (19.6) | 0.37 (10.6) | 1.25 (16.7) |

| PERV | ||||||||||

| PERV-PK15 | 1.5 (3) | 3.5 (3.7) | 2 (4) | 4.3 (4.8) | >10 (>20) | >10 (>9.1) | 1 (5.4) | 4.5 (8) | 0.9 (25.7) | >2 (>26.7) |

| PERV-293 | 1.5 (3) | 3.8 (4) | 2.3 (4.6) | 4.3 (4.8) | >10 (>20) | >10 (>9.1) | 1.2 (6.5) | 4 (7.1) | 0.45 (12.86) | 1.6 (21.3) |

IC50s and IC90s were determined by using the Amp-RT assay. Numbers in parentheses indicate fold resistance compared to the mean ICs for WT HIV-1. IC50s and IC90s (in micromolar units) were calculated from triplicate results. ND, not determined.

No significant differences were found in the drug susceptibilities of PERV-PK15 and PERV-293, except to d4T-TP, with which a twofold difference in IC50s was observed. This likely reflected assay variability rather than inherent phenotypic changes between the two viral preparations. Similarly, changes were also seen for the WT HIV-1 isolates, with IC50s for 3TC-TP and ddA-TP differing by 1.5-fold and 2.7-fold, respectively.

We also tested PERV RT for susceptibility to nevirapine, a nonnucleoside inhibitor of HIV-1 RT. One Amp-RT assay with 50 μM nevirapine was used in this screening. This concentration of nevirapine completely inhibits WT HIV-1 RT activity (IC50, 4 μM) (49). In contrast to what was observed with WT HIV-1, no inhibition of PERV RT was observed in this test, indicating lack of activity of nevirapine on PERV RT (data not shown).

RT susceptibility analysis by cell culture-based infectivity assays.

Susceptibility of PERV and HIV-1 to RTIs was evaluated on the CD4-expressing human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (RD-CD4) (7). This cell line is able to support the infection and replication of both PERV and HIV-1. In situ focus-forming assays were carried out using PERV-B lacZ pseudotype (see below) and the HIV-1LAI isolate. For IC50 and IC90 determinations for WT HIV-1, reduction in the number of foci producing p24 was quantitated (41), while for PERV a lacZ pseudotype was generated and reduction in the number of foci producing β-galactosidase was quantitated (44).

To generate PERV-B lacZ pseudotypes, the human embryonic kidney cell line 293/PERV-B, persistently infected with PERV-B (43), was transduced with the MFGnlslacZ vector using a helper-free vector bearing gibbon ape leukemia virus envelopes (35). MFGnlslacZ is a murine leukemia virus (MuLV)-based vector containing functional long terminal repeats and a Ψ packaging signal sequence, as well as a lacZ marker gene. It encodes β-galactosidase and no MuLV gag, pol, or env gene products (13). A cell population of which the majority of cells (>95%) contain MFGnlslacZ was established and named 293/PERV-B/lacZ. These cells produce a mixture of replication-competent PERV-B and PERV pseudotypes which contain the MFGnlslacZ genome (45). This viral mixture is referred to as PERV-lacZ pseudotypes. After overnight incubation of these cells, the supernatant containing PERV-lacZ was filtered (filter pore size, 0.45 μm) and used for drug susceptibility testing.

RD-CD4 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 8 × 104 cells/well in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal calf serum and incubated overnight. The culture medium was replaced with 450 μl of HIV-1 or PERV-lacZ pseudotype supernatants which had been diluted in Opti-MEM (Gibco-BRL) to have approximately 150 and 60 focus-forming units of virus per well, respectively. After incubation for 1 h, virus inocula were removed and 1 ml of medium containing RTIs was added. Three days later, cells were fixed and stained for expression of β-galactosidase (44) or HIV-1 p24 (HIV-1LAI) (41).

The data from the culture-based assays are shown in Table 2 and are in agreement with the data from the enzymatic assays. This testing also demonstrated that, with the exception of zidovudine, which had an IC50 close to that for WT HIV-1, all other drugs had little or no activity against PERV. The level of resistance of PERV to zalcitabine and didanosine was higher in these assays than in the enzymatic assays.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility of PERV to different RTIs and comparison with that of WT HIV-1

| Virus | IC50 ofa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zidovudine | Zalcitabine | Lamivudine | Didanosine | Stavudine | Nevirapine | |

| HIV-ILAI | 0.015 | 1.3 | 0.12 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 0.03 |

| PERV-B | 0.061 (4.1) | 28 (21.5) | >50 (>417) | >50 (>23) | 30 (20) | >50 (>1,667) |

IC50s were determined by culture-based infectivity assays. Numbers in parentheses indicate fold resistance compared to the IC50 for WT HIV-1. IC50s (in micromolar units) were calculated from duplicate results.

Protease susceptibility analysis.

Susceptibility of PERV to PIs was assessed in a Gag polyprotein-processing inhibition assay, as previously described for MuLV (2), in which the presence of cleaved PERV Gag proteins in PERV-293 cells was determined by Western blot analysis following PI treatment. PIs tested included indinavir, nelfinavir, saquinavir, ritonavir, and amprenavir. For WT HIV-1 PI tests, OM-10.1 cells were used. These cells contain a single integrated WT HIV-1 provirus which is induced after treatment with 20 U of tumor necrosis factor alpha per ml (4). HIV-1 production in 3 × 106 OM-10.1 cells was induced at the time of addition of PIs (0.001 to 10 μg/ml). Cells were incubated for 24 h and harvested. One to 25 μg of each PI per ml was added to 3 × 106 PERV-293 cells in 10 ml of growth medium. After incubation for 3 days, PERV-293 cells were harvested by trypsinization. Aliquots of harvested OM-10.1 and PERV-293 cells were checked for viability by trypan blue exclusion. Protein concentration of homogenized lysates was determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.).

Ten micrograms of OM-10.1 and 15 μg of PERV-293 whole-cell lysate proteins were electrophoresed and electroblotted (27). HIV-1 p24 monoclonal antibody (16), which reacts with p24, p55, and several intermediates, was used (1:600 dilution) to react with the OM-10.1 blots. Anti-simian sarcoma-associated virus p29 polyclonal serum (Quality Biotech, Camden, N.J.), which cross-reacts with the processed PERV Gag p30 and its precursor p55, was used (1:200 dilution) to react with PERV-293 blots (27). Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using an ECL Western blot detection reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.).

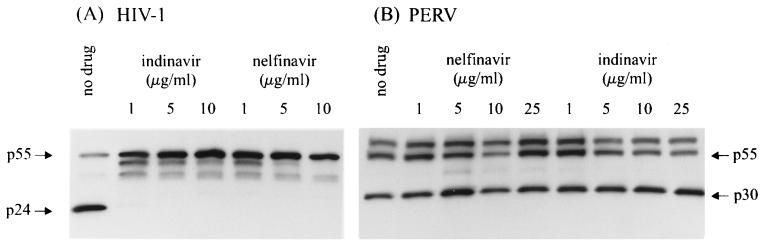

As expected, WT HIV-1 was found to be sensitive to all five PIs tested. No p24 Gag protein was detected in OM-10.1 cell cultures treated with 1 μg of PIs per ml, while untreated cells had a detectable p24 band (Fig. 1). In addition, accumulation of the unprocessed p55 and other intermediates (p48 and p42) was also observed in these lysates (Fig. 1). No p24 or its precursors (p55, p48, and p42) were detected in the cells which were not stimulated with tumor necrosis factor alpha (data not shown). In contrast, no difference in p30 reactivity was seen among PERV-293 cells that were treated with a concentration up to 25 μg/ml (the highest concentration tested) of indinavir, nelfinavir, saquinavir, ritonavir, or amprenavir, which represented a 233- to 6,520-fold increase in the IC50s reported for WT HIV-1 (3, 9). Representative results are shown for nelfinavir and indinavir in Fig. 1. Thus, our results indicate that PERV is resistant to all five PIs.

FIG. 1.

Susceptibility of HIV-1 and PERV to PIs by a Gag protein-processing inhibition assay. (A) Immunoblot of HIV-1-infected OM-10.1 cells treated with different concentrations of indinavir and nelfinavir (first lane, no treatment). Positions of Gag proteins are indicated. (B) Immunoblot of PERV-293 cells untreated (first lane) and treated with different concentrations of nelfinavir and indinavir.

Sequence comparison.

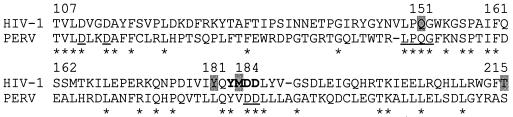

To better understand the basis of the susceptibility of PERV to the antiretrovirals tested in this study, we compared the amino acid sequences of the pol regions of PERV derived from PK15 cells (GenBank accession numbers U77599 and AF038601) and HIV-1 (subtype B) (accession number M38432). Alignment was performed with the multiple alignment construction and analysis workbench program (38), with introduction of minimal gaps to facilitate optimal alignment. The PERV sequence analyzed corresponded to the HIV-1 protease codons 29 to 99 and RT codons 1 to 291. A portion of the alignment of HIV-1 RT, which harbors codons associated with drug resistance, with PERV RT is shown in Fig. 2. HIV-1 and PERV were found to share only about 22.5% amino acid residues in protease or RT, indicating that these proteins are structurally diverse. The high level of divergence between both sequences restricts the comparison between RTI resistance-related mutations of HIV-1 and PERV to only those which are conserved among all retroviruses. Mutations at two such codons, Q151M (in the conserved LPQG motif), and M184V (in the polymerase active-site YMDD motif) are associated with resistance to multiple nucleoside analogs and to lamivudine, respectively, in HIV-1 and other lentiviruses. PERV RT, as in WT HIV-1, has a Q at the codon corresponding to 151, which does not support a role of this residue in the observed resistance of PERV to several nucleoside analogs. However, PERV has a V instead of an M at the codon corresponding to 184, which may likely explain the observed resistance to lamivudine. Verifying the possible role of this residue in PERV's resistance to lamivudine will require drug susceptibility analysis of site-specific mutants containing either an M or a V residue at this site.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of portions of HIV-1 and PERV RT amino acid sequences. Identical residues are indicated with an asterisk. Four D residues (codons 110, 113, 185, and 186) and the LPQG motif (codons 149 to 152) conserved among the retroviruses are underlined (34a). The HIV-1 polymerase active-site YMDD (codons 183 to 186) is in bold. Codons associated with resistance of HIV-1 to multinucleoside analogs (Q151M), nevirapine (Y181C), lamivudine (M184V), and zidovudine (T215Y/F) are shaded.

The observed susceptibility of PERV to zidovudine may not be surprising since this nucleoside analog has been shown to have a broad range of activity against several retroviruses (25, 28), including MuLV and feline leukemia virus, two C-type iruses which are closely related to PERV (36, 46). Our sequence analysis indicated that both MuLV (accession number U13766) and feline leukemia virus (accession number AF052723) share significant homology (79 and 70% amino acid residues, respectively) with PERV RT. Accordingly, isolates with lacZ pseudotypes containing Moloney MuLV Gag-Pol were tested by our culture-based infectivity assay and showed a pattern of drug sensitivity similar to that of PERV (data not shown).

As expected, PERV showed no susceptibility to HIV-1-specific PIs, despite the structural diversity of these compounds and the use of concentrations that were several hundredfold higher than those for WT HIV-1 (6, 12, 29). The lack of susceptibility may be explained by the structural differences between PERV and HIV-1 protease, which were found to share only ∼22% of their amino acid residues.

Structure-dependent binding may also explain the resistance of PERV to nevirapine, which binds specifically to a hydrophobic cavity adjacent to the polymerase active site in HIV-1 RT and requires close contact with a tyrosine residue at codon 181 (21, 42). The observed resistance of PERV RT to nevirapine was, therefore, expected and may very likely be due to the absence of this pocket, resulting from significant structural differences.

Our data do, however, demonstrate that some nucleoside RTIs were active against PERV RT. Zidovudine had the highest level of activity against PERV, with IC50s only ∼3-fold those for WT HIV-1 but well within the achievable concentration of zidovudine in vivo, which has a maximum concentration of drug in serum of 3.4 μM (14). These in vitro data are promising and support the clinical use of zidovudine in PERV-infected persons. Prophylactic use of zidovudine has also been successful in reducing transmission of HIV-1 in infants born to HIV-1-infected mothers as well as in recipients of needle-stick injuries from HIV-1-infected source patients (reviewed in references 18 and 53). Therefore, our data on zidovudine may also support evaluating the use of this drug as a prophylactic in persons who will be transiently exposed to pig tissues, such as in extracorporeal perfusions with pig livers or hepatocytes. The need for such a prophylactic will, however, depend on the risks of PERV transmission from these procedures. The assays developed and used in this study also provide tools for identifying novel PIs or RTIs that are active against PERV.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Sal Butera (CDC, Atlanta, Ga.) for providing OM-10.1 cells and Hiroaki Mitsuya (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.) for HIV-1 clones (HIV-1SUM9, HIV-1SUM8, HIV-1SUM12, and HIV-1SUM13). HIV-1 p24 monoclonal antibody, some RTIs, and PIs were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH (Rockville, Md.).

The research at the Wohl Virion Centre was supported by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyoshi D E, Denaro M, Zhu H, Greenstein J L, Banerjee P, Fishman J A. Identification of a full-length cDNA for an endogenous retrovirus of miniature swine. J Virol. 1998;72:4503–4507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4503-4507.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black P L, Downs M B, Lewis M G, Ussery M A, Dreyer G B, Petteway S R, Lambert D M. Antiretroviral activities of protease inhibitors against murine leukemia virus and simian immunodeficiency virus in tissue culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:71–77. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boden D, Markowitz M. Resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2775–2783. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butera S T, Roberts B D, Lam L, Hodge T, Folks T M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA expression by four chronically infected cell lines indicates multiple mechanisms of latency. J Virol. 1994;68:2726–2730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2726-2730.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chari R S, Collins B, Magee J, DiMaio J, Kirk A, Harland R, McCann R, Platt J, Meyers W. Treatment of hepatic failure with ex vivo pig-liver perfusion followed by liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:234–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407283310404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Li Y, Schock H, Hall D, Chen E, Kuo L. Three-dimensional structure of a mutant HIV-1 protease displaying cross-resistance to all protease inhibitors in clinical trials. J Biol Chem. 1995;15:21433–21436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clapham P R, Blanc D, Weiss R. Specific cell surface requirements for the infection of CD4-positive cells by human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 and by simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1991;181:2703–2715. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90904-P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffin J M. Retroviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1767–1830. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig J C, Duncan I B, Hockley D, Grief C, Roberts N, Mills J S. Antiviral properties of Ro 31-8959, an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) proteinase. Antivir Res. 1991;16:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90045-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cramer D V. The use of xenografts for acute hepatic failure. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deacon T, Schumacher J, Dinsmore J, Thomas C, Palmer P, Kott S, Edge A, Penny D, Kassissieh S, Dempsey P, Isacson O. Histological evidence of fetal pig neural cell survival after transplantation into a patient with Parkinson's disease. Nat Med. 1997;3:350–353. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erickson J W, Eissenstat M A. HIV protease as a target for the design of antiviral agents for AIDS. In: Dunn B M, editor. Proteases of infectious agents. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferry N, Duplessis O, Houssin D, Danos O, Heard J M. Retroviral-mediated gene transfer into hepatocytes in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8377–8381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flexner C, Hendrix C. Pharmacology of antiretroviral agents. In: DeVito V T Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg S A, editors. AIDS: biology, diagnosis, and prevention. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 479–493. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Lerma J, Schinazi R F, Juodawlkis A, Soriano V, Lin Y, Tatti K, Rimland D, Folks T M, Heneine W. A rapid non-culture-based assay for clinical monitoring of phenotypic resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to lamivudine (3TC) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:264–270. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorny M K, Gianakakos V, Sharpe S, Zolla-Pazner S. Generation of human monoclonal antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1624–1628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groth C G, Korsgren O, Tibell A, Tollemar J, Moller E, Bolinder J, Ostman J, Reinholt F P, Hellerstrom C, Andersson A. Transplantation of porcine fetal pancreas to diabetic patients. Lancet. 1994;344:1402–1404. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson D K. Postexposure chemoprophylaxis for occupational exposures to the human immunodeficiency virus. JAMA. 1999;281:931–936. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.10.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heneine W, Tibell A, Switzer W M, Sandstrom P, Rosales G V, Mathews A, Korsgren O, Chapman L E, Folks T M, Groth C G. No evidence of infection with porcine endogenous retrovirus in recipients of porcine islet-cell xenografts. Lancet. 1998;352:695–699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heneine W, Yamamoto S, Switzer W M, Spira T J, Folks T M. Detection of reverse transcriptase by a highly sensitive assay in sera from persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1210–1216. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohlstaedt L A, Wang J, Friedman J M, Rice P A, Steitz T A. Crystal structure at 3.5 Å resolution of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complexed with an inhibitor. Science. 1992;256:1783–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laan L J W, Lockey C, Griffeth B C, Frasier F S, Wilson C A, Onions D E, Hering B J, Long Z, Otto E, Torbett B E, Salomon D R. Infection by porcine endogenous retrovirus after islet xenotransplantation in SCID mice. Nature. 2000;407:501–504. doi: 10.1038/35024089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Tissier P, Stoye J P, Takeuchi Y, Patience C, Weiss R A. Two sets of human-tropic pig retroviruses. Nature. 1997;389:681–682. doi: 10.1038/39489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy M F, Crippin J, Sutton S, Netto G, McCormack J, Curiel T, Goldstein R M, Newman J, Gonwa T, Banchereau J, Diamond L, Byrne G, Logan J, Klintmalm G B. Liver allotransplantation after extracorporeal hepatic support with transgenic (hCD55/hCD59) porcine livers: clinical results and lack of pig-to-human transmission of the porcine endogenous retrovirus. Transplantation. 2000;69:272–280. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200001270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macchi B, Faraoni I, Zhang J, Grelli S, Favalli C, Mastino A, Bonmassar E. AZT inhibits the transmission of human T cell leukaemia/lymphoma virus type I to adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1007–1016. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-5-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin U, Kiessig V, Blusch J, Haverich A, von der Helm K, Herden T, Steinhoff G. Expression of pig endogenous retrovirus by primary porcine endothelial cells and infection of human cells. Lancet. 1998;352:692–694. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07144-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews A L, Brown J, Switzer W, Folks T M, Heneine W, Sandstrom P A. Development and validation of a Western immunoblot assay for detection of antibodies to porcine endogenous retrovirus. Transplantation. 1999;67:939–943. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199904150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitsuya H, Broder S. Inhibition of infectivity and replication of HIV-2 and SIV in helper T-cells by 2′,3′-dideoxynucleosides in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;4:107–113. doi: 10.1089/aid.1988.4.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nascimbeni M, Lamotte C, Peytavin G, Farinotti R, Clavel F. Kinetics of antiviral activity and intracellular pharmacokinetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors in tissue culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2629–2634. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen M H, Schinazi R F, Shi C, Goudgaon N M, McKenna P M, Mellors J W. Resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to acyclic 6-phenylselenenyl- and 6-phenylthiopyrimidines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2409–2414. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paradis K, Langford G, Long Z, Heneine W, Sandstrom P, Switzer W M, Chapman L E, Lockey C, Onions D, Otto E. Search for cross-species transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus in patients treated with living pig tissue. Science. 1999;285:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patience C, Patton G S, Takeuchi Y, Weiss R A, McClure M O, Rydberg L, Breimer M E. No evidence of pig DNA or retroviral infection in patients with short-term extracorporeal connection to pig kidneys. Lancet. 1998;352:699–701. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patience C, Takeuchi Y, Weiss R A. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nat Med. 1997;3:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettit S C, Sanchez R, Smith T, Wehbie R, Derse D, Swanstrom R. HIV type 1 protease inhibitors fail to inhibit HTLV-I Gag processing in infected cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:1007–1014. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Poch O, Sauvaget I, Delarue M, Tordo N. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA-dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J. 1989;8:3867–3874. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter C D, Collins M K, Tailor C S, Parkar M H, Cosset F L, Weiss R A, Takeuchi Y. Comparison of efficiency of infection of gene therapy target cells via four different retroviral receptors. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:913–919. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.8-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powell S K, Artlip M, Kaloss M, Brazinski S, Lyons R, McGarrity G J, Otto E. Efficacy of antiretroviral agents against murine replication-competent retrovirus infection in human cells. J Virol. 1999;73:8813–8816. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8813-8816.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schinazi R F, McMillan A, Cannon D, Mathis R, Lloyd R M, Peck A, Sommadossi J P, St. Clair M, Wilson J, Furman P, Painter G, Choi W, Liotta D C. Selective inhibition of human immunodeficiency viruses by racemates and enantiomeres of cis-5-fluoro-1-[2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-oxathiolan-5-yl]cytosine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2423–2431. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.11.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuler G D, Altschul S F, Lipman D J. A workbench for multiple alignment construction and analysis. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;9:180–190. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schumacher J M, Ellias S A, Palmer E P, Kott H S, Dinsmore J, Dempsey P K, Fischman A J, Thomas C, Feldman R G, Kassissieh S, Raineri R, Manhart C, Penney D, Fink J S, Isacson O. Transplantation of embryonic porcine mesencephalic tissue in patients with PD. Neurology. 2000;54:1042–1050. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shirasaka T, Kavlick M F, Ueno T, Gao W Y, Kojima E, Alcaide M L, Chokekijchai S, Roy B M, Arnold E, Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H. Emergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with resistance to multiple dideoxynucleosides in patients receiving therapy with dideoxynucleosides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2398–2402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simmons G, McKnight A, Takeuchi Y, Hoshino H, Clapham P R. Cell to cell fusion, but not virus entry in macrophages by T-cell tropic HIV-1 strains: a V3 loop determined restriction. Virology. 1995;209:696–700. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smerdon S J, Jager J, Wang J, Kohlstaedt L A, Chirino A J, Friedman J M, Rice P A, Steitz T A. Structure of the binding site for nonnucleoside inhibitors of the reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3911–3915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takeuchi Y, Patience C, Magre S, Weiss R A, Banerjee P T, LeTissier P, Stoye J P. Host-range and interference studies on three classes of pig endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:9986–9991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9986-9991.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeuchi Y, Cosset F L, Lachmann P J, Okada H, Weiss R A, Collins M K L. Type C retroviral inactivation by human complement is determined by both the viral genome and the producer cell. J Virol. 1994;68:8001–8007. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8001-8007.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeuchi Y, Simpson G, Vile R G, Weiss R A, Collins M K L. Retroviral pseudotypes produced by rescue of a Moloney murine leukemia virus vector by C-type, but not D-type, retroviruses. Virology. 1992;186:792–794. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90049-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tavares L, Roneker C, Johnston K, Lehrman S N, de Noronha F. 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine in feline leukemia virus-infected cats: a model for therapy and prophylaxis of AIDS. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3190–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tibell A, Groth C G, Moller E, Korsgren O, Andersson A, Hellerstrom C. Pig-to-human islet transplantation in eight patients. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:762–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ueno T, Shirasaka T, Mitsuya H. Enzymatic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 reverse transcriptase resistant to multiple 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphates. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23605–23611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vazquez-Rosales G, Garcia Lerma J G, Yamamoto S, Switzer W M, Havlir D, Folks T M, Richman D D, Heneine W. Rapid screening of phenotypic resistance to nevirapine by direct analysis of HIV type 1 reverse transcriptase activity in plasma. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:1191–1200. doi: 10.1089/088922299310287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson C A, Wong S, Muller J, Davidson C E, Rose T M, Burd P. Type C retrovirus released from porcine primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells infects human cells. J Virol. 1998;72:3082–3087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3082-3087.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson C A, Wong S, VanBrocklin M, Federspiel M J. Extended analysis of the in vitro tropism of porcine endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 2000;74:49–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.49-56.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamamoto S, Folks T M, Heneine W. Highly sensitive qualitative and quantitative detection of reverse transcriptase activity: optimization, validation, and comparative analysis with other detection systems. J Virol Methods. 1996;61:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(96)02078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zorrilla C D. Mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission: state of the art and implications for public policy. P R Health Sci J. 2000;19:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]