Abstract

Cytoplasmic vector systems are generally used for expression of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) proteins. However, we achieved high levels of cell surface glycoproteins using a standard nuclear expression plasmid. Expression was independent of other LCMV proteins but was blocked by a missense mutation within the original LCMV(WE) glycoprotein cDNA.

The lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is the prototype arenavirus and a widely used experimental model for the study of viral persistence and pathogenesis. The envelope glycoproteins of LCMV (LCMV GP) are initially expressed as a precursor polypeptide, GP-C, which is posttranslationally processed by a cellular protease into GP-1 and GP-2. GP-1 interacts with the cellular receptor for LCMV, which has been identified as alpha-dystroglycan. GP-2 contains the fusion peptide and the transmembrane domain (2–5).

It was previously shown that retroviral vectors can be pseudotyped with LCMV glycoproteins (11). These pseudotypes, like pseudotypes with the G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus, are stable during ultracentrifugation, but unlike the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein, the LCMV glycoproteins are not cytotoxic. A prerequisite for the generation of safe, helper-free vector particles for this novel pseudotype is the efficient expression of recombinant LCMV GP on the surface of retroviral packaging cells. LCMV has a cytoplasmic life cycle. Therefore, vaccinia virus has been used frequently to express LCMV GP in order to prevent aberrant splicing of GP transcripts in the nucleus. In addition, the originally cloned glycoprotein cDNA of LCMV strain WE [LCMV(WE)] has been expressed by baculovirus and retroviral expression systems as well as in transgenic mice (7, 9, 10, 14). These systems were widely used to study the immune response in mice (6, 8, 12, 13). However, efficient cell surface expression of recombinant LCMV GP was never shown. The aim of this study was to express LCMV(WE) glycoproteins on the cell surface by a nuclear expression system that could be used for the generation of helper virus-free retroviral pseudotypes.

(This article is based on a doctoral study by W.B. in the Faculty of Biology, University of Hamburg.)

Recombinant LCMV(WE) glycoproteins are not transported to the cell surface.

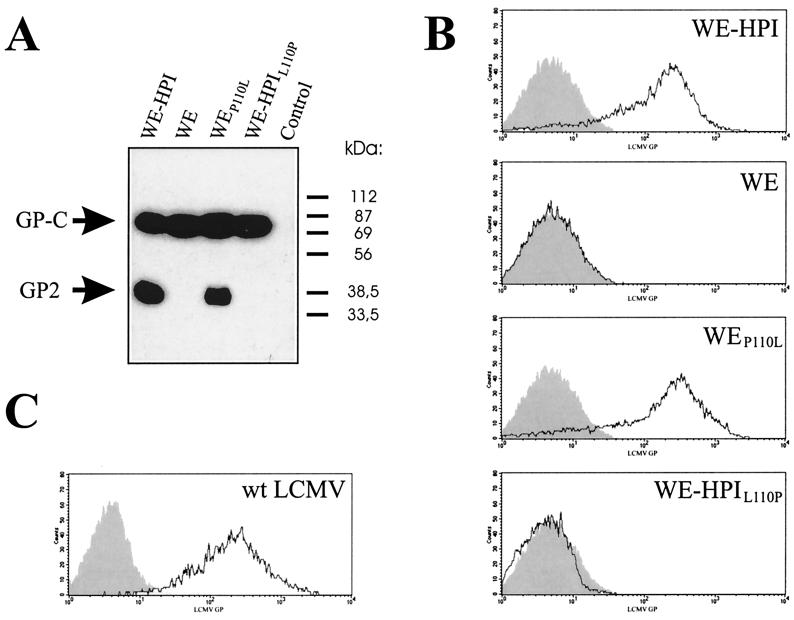

The expression plasmid pHCMV-GP(WE) was derived from the widely used original cDNA of LCMV(WE) S RNA and the pHCMV expression vector (15, 19). pHCMV contains the human cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter, the rabbit beta-globin intron B, and the rabbit beta-globin polyadenylation sequences. The GP cDNA was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pY-1-A and inserted between the BamHI sites of pHCMV by using the restriction sites introduced by PCR primers (5′ CTGGATCCGC CATGGGTCAG ATTGTGACAA TG 3′ and 5′ CGGGATCCTT ATCAGCGTCT TTTCCAGATA G 3′) (10). Sequence analysis showed that the pY-1-A clone and the cDNA in the newly generated pHCMV-GP(WE) encoded L455 and K457, as also found in other LCMV GP sequences, and not F455 and R457 as found in the original publications (15–18). After calcium phosphate transfection of pHCMV-GP(WE) into 293T cells, no cell surface expression of recombinant LCMV GP was detectable by flow cytometry with the monoclonal antibody KL25 (Fig. 1B, WE) or other monoclonal GP-1-specific and polyclonal anti-LCMV antibodies (1; data not shown). In contrast, 3 days after infection with LCMV(WE) viral glycoproteins were expressed on the cell surface as shown by flow cytometry with the KL25 antibody (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

The proline-to-leucine mutation at amino acid 110 leads to processing and cell surface expression of LCMV GP. (A) Western blot analysis of recombinant LCMV GP. 293T cells were transfected with pHCMV expression plasmids encoding C-terminally HA-tagged LCMV GP variants or untagged LCMV GP (control). Forty-eight hours after transfection proteins were extracted, and samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and analyzed by immunostaining with the anti-HA tag-specific antibody 3F10. (B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of recombinant LCMV GP. 293T cells were mock treated (shaded lines) or transfected with pHCMV expression plasmids for LCMV GP variants (open lines). Forty-eight hours after transfection, LCMV GP was detected by flow cytometry with the monoclonal antibody KL25. (C) LCMV GP expression after infection of 293T cells with LCMV. Three days after infection with a multiplicity of infection of 0.01, LCMV GP was detected by flow cytometry with monoclonal antibody KL25. WE-HPI, pHCMV-GP(WE-HPI); WE, pHCMV-GP(WE); WEP110L, pHCMV-GP(WEP110L), which encodes a proline-to-leucine mutation at amino acid 110; WE-HPIL110P, pHCMV-GP(WE-HPIL110P), which encodes a leucine-to-proline mutation at amino acid 110; GP-C, precursor glycoprotein; GP-2, C-terminal cleavage product of GP-C containing the HA tag. wt, wild type.

Recombinant LCMV(WE) GP-C is expressed but not correctly processed.

To test whether inefficient protein expression was caused by a lack of transcription or aberrant splicing of the LCMV GP message expressed in the nucleus, total RNA was extracted from pHCMV-GP(WE)-transfected 293T cells. In Northern blot analysis, an LCMV GP mRNA of correct length was detected. No aberrant splicing of this transcript was found by reverse transcription-PCR and sequence analysis of cloned PCR products (seven cDNA clones from three independent PCRs). Furthermore, the level of the GP mRNA in transfected cells was higher than the level found in LCMV-infected cells (data not shown).

To analyze translation and processing of LCMV glycoproteins, an expression vector encoding C-terminally hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged LCMV GP was constructed as described above using the PCR primers 5′ CTGGATCCGC CAT GGGTCAG ATTGTGACAA TG 3′ and 5′ CGGGATC CTT ATCAAGCGTA ATCTGGAACA TCGTATGGGT AGCGTCTTTT CCAGATAGT 3′. Two days after transfection of this construct into 293T cells, protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-HA tag-specific antibody (3F10; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The precursor glycoprotein GP-C was efficiently expressed but not processed into mature GP-1 and GP-2 (Fig. 1A, WE).

LCMV GP cDNA recloned from virus-infected cells encodes a glycoprotein that is efficiently processed and transported.

The reason for an inefficient processing of recombinant LCMV GP-C compared to virus-expressed GP-C could be that the sequences of the recombinant and the wild-type GP differ. Therefore, the GP cDNA was recloned by reverse transcription-PCR of total RNA extracted 2 days after infection of 293T cells with a multiplicity of infection of LCMV(WE) of 0.01. The PCR product was sequenced directly or after blunt-end ligation into the EcoRV site of pBluescript. Within the open reading frame, the sequence of the recloned GP cDNA differed by 28 nucleotides (1.9%) from the published LCMV(WE) GP sequence, by 218 nucleotides (14.6%) from the LCMV(Arm53b) GP sequence, and by 213 nucleotides (14.3%) from the LCMV(CHV2) GP sequence (15, 16, 18). The encoded amino acids had 12 differences (2.4%) with LCMV(WE) GP, 23 differences (4.6%) with LCMV(Arm53b) GP, and 28 differences (5.6%) with LCMV(CHV2) GP. This indicates that the recloned LCMV GP was indeed a WE serotype, and it was therefore named LCMV GP(WE-HPI).

The new GP(WE-HPI) sequence was inserted as described above into pHCMV. Two days after transfection of 293T cells, protein was extracted and analyzed by Western blotting. In contrast to the GP(WE) sequence, the GP(WE-HPI) sequence encoded an LCMV glycoprotein, which was processed as shown by the detection of GP-2, the C-terminal cleavage product containing the HA tag (Fig. 1A, WE-HPI). Cell surface expression was analyzed again 2 days after transfection by flow cytometry with the monoclonal antibody KL25. In contrast to the GP(WE) construct, the pHCMV-GP(WE-HPI) plasmid directed efficient cell surface expression of LCMV GP (Fig. 1B, WE-HPI). This shows that processing and cell surface expression of recombinant LCMV GP are independent of other LCMV proteins.

A single mutation is responsible for the block in LCMV glycoprotein processing and transport.

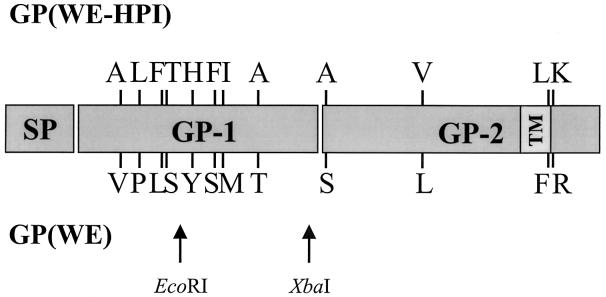

To analyze which amino acids in the original GP(WE) sequence impeded processing and cell surface expression of LCMV GP, chimeric glycoprotein expression constructs were generated using the XbaI and EcoRI sites in GP (Fig. 2). For both restriction sites, the expression plasmids encoding LCMV GP with the N-terminal portion of the GP(WE-HPI) sequence and the C-terminal part of the original GP(WE) sequence led to cell surface expression, whereas the inverse constructs did not. Therefore, the essential difference is upstream of the EcoRI site, where four missense mutations are located (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Twelve different amino acids are encoded by the recloned LCMV GP(WE-HPI) cDNA and the originally published LCMV GP(WE) sequence (15).

The leucine-to-proline mutation at amino acid 110 is the most striking one and was therefore analyzed. The GP(WEP110L) mutant was generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the GP(WE) sequence, substituting the encoded proline for leucine at position 110. The GP(WE-HPIL110P) sequence was derived from the GP(WE-HPI) sequence by introducing a leucine110-to-proline110 missense mutation. The correct sequences of the expression plasmids were checked by DNA sequencing of the complete LCMV GP open reading frame. Western blot analysis of protein extracts from transfected 293T cells showed that LCMV GP encoded by pHCMV-GP(WEP110L) and pHCMV-GP(WE-HPI) were processed correctly, whereas the pHCMV-GP(WE-HPIL110P) and the original GP(WE) sequence encoded an unprocessed LCMV GP-C protein (Fig. 1A). Cell surface expression of recombinant LCMV GP was analyzed again by flow cytometry with the monoclonal antibody KL25. pHCMV-GP(WEP110L) and pHCMV-GP(WE-HPI) directed high levels of cell surface GP expression, whereas pHCMV-GP(WE-HPIL110P) and pHCMV-GP(WE) did not (Fig. 1B). This shows that proline at position 110 impedes, while a leucine allows, processing and efficient cell surface expression of recombinant LCMV GP.

Here, a high level of cell surface expression of recombinant LCMV(WE) glycoproteins was achieved for the first time. Expression was directed from the nucleus and no aberrant splicing was detected. The expression, processing, and transport of the LCMV glycoproteins were independent of other LCMV proteins but were blocked by a leucine-to-proline mutation at amino acid 110, encoded in the original glycoprotein cDNA of LCMV(WE). Furthermore, correct expression was found to be necessary for glycoprotein function, as shown by the infectivity of generated retrovirus vector particles pseudotyped with LCMV GP(WE-HPI) (11; W. R. Beyer et al., unpublished data).

In previous studies, expression of recombinant LCMV GP(WE) was generally detected by cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses (7, 8, 12, 13). This method, however, is extremely sensitive, and correct processing and surface expression of the glycoproteins are not required. Whether the efficiency of LCMV GP processing and transport can affect CTL recognition remains unclear and requires further studies. In addition, it is of interest whether other natural mutations in LCMV GP, such as CTL and antibody escape mutations, can influence processing and transport of LCMV glycoproteins.

Efficient expression of recombinant LCMV glycoproteins is one prerequisite for the generation of infectious LCMV from cDNAs. Furthermore, it is essential for the generation of helper-free packaging cells, which produce retroviral vectors pseudotyped with LCMV GP. These pseudotypes are an attractive alternative to conventional retroviral vectors for gene therapy (11). In addition, they allow the functional characterization of LCMV glycoprotein variants without the need to establish reverse genetics for LCMV.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The cDNA sequence of the recloned LCMV GP(WE-HPI) has been submitted to the EMBL database under the accession no. AJ297484.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Abel for excellent technical assistance and M. Bruns for providing monoclonal antibodies, virus, and plasmids.

The work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant LA 1135/3-1) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung and CellTec Biotechnologie GmbH (grant 00312173).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruns M, Cihak J, Müller G, Lehmann-Grube F. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. VI. Isolation of a glycoprotein mediating neutralization. Virology. 1983;130:247–251. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruns M, Lehmann-Grube F. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. V. Proposed structural arrangement of proteins in the virion. J Gen Virol. 1983;64:2157–2167. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-10-2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchmeier M J, Oldstone M B. Protein structure of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: evidence for a cell-associated precursor of the virion glycopeptides. Virology. 1979;99:111–120. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns J W, Buchmeier M J. Protein-protein interactions in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology. 1991;183:620–629. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90991-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao W, Henry M D, Borrow P, Yamada H, Elder J H, Ravkov E V, Nichol S T, Compans R W, Campbel K P, Oldstone M B. Identification of alpha-dystroglycan as a receptor for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and Lassa fever virus. Science. 1998;282:2079–2081. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garza K M, Chan S M, Suri R, Nguyen L T, Odermatt B, Schoenberger S P, Ohashi P S. Role of antigen-presenting cells in mediating tolerance and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2021–2028. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hany M, Oehen S, Schulz M, Hengartner H, Mackett M, Bishop D H, Overton H, Zinkernagel R M. Anti-viral protection and prevention of lymphocytic choriomeningitis or of the local footpad swelling reaction in mice by immunization with vaccinia-recombinant virus expressing LCMV-WE nucleoprotein or glycoprotein. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:417–424. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harlan D M, Hengartner H, Huang M L, Kang Y, Abe R, Moreadith R W, Pircher H, Gary G S, Ohashi P S, Freeman G J, Nadler L M, June C H, Aichele P. Mice expressing both B7–1 and viral glycoprotein on pancreatic beta cells along with glycoprotein-specific transgenic T cells develop diabetes due to a breakdown of T-lymphocyte unresponsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3137–3141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kundig T M, Bachmann M F, DiPaolo C, Simard J J, Battegay M, Lother H, Gessner A, Kuhlcke K, Ohashi P S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R. Fibroblasts as efficient antigen-presenting cells in lymphoid organs. Science. 1995;268:1343–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.7761853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuura Y, Possee R D, Bishop D H. Expression of the S-coded genes of lymphocytic choriomeningitis arenavirus using a baculovirus vector. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:1515–1529. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-8-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miletic H, Bruns M, Tsiakas K, Vogt B, Rezai R, Baum C, Kuhlke K, Cosset F L, Ostertag W, Lother H, von Laer D. Retroviral vectors pseudotyped with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol. 1999;73:6114–6116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6114-6116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oehen S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Vaccination for disease. Science. 1991;251:195–198. doi: 10.1126/science.1824801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohashi P S, Oehen S, Aichele P, Pircher H, Odermatt B, Herrera P, Higuchi Y, Buerki K, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Induction of diabetes is influenced by the infectious virus and local expression of MHC class I and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Immunol. 1993;150:5185–5194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohashi P S, Oehen S, Buerki K, Pircher H, Ohashi C T, Odermatt B, Malissen B, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. Ablation of “tolerance” and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;65:305–317. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90164-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romanowski V, Matsuura Y, Bishop D H. Complete sequence of the S RNA of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (WE strain) compared to that of Pichinde arenavirus. Virus Res. 1985;3:101–114. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(85)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salvato M, Shimomaye E, Southern P, Oldstone M B. Virus-lymphocyte interactions. IV. Molecular characterization of LCMV Armstrong (CTL+) small genomic segment and that of its variant, Clone 13 (CTL−) Virology. 1988;164:517–522. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Southern P J, Singh M K, Riviere Y, Jacoby D R, Buchmeier M J, Oldstone M B. Molecular characterization of the genomic S RNA segment from lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology. 1987;157:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephensen C B, Park J Y, Blount S R. cDNA sequence analysis confirms that the etiologic agent of callitrichid hepatitis is lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol. 1995;69:1349–1352. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1349-1352.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yee J-K, Friedmann T, Burns J C. Generation of high-titer pseudotyped retroviral vectors with very broad host range. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;43:99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]