Abstract

We have described a reconstituted avian sarcoma virus (ASV) concerted DNA integration system with specially designed mini-donor DNA containing a supF transcription unit, a supercoiled plasmid acceptor, purified bacterially expressed ASV integrase (IN), and human high-mobility-group protein I(Y). Integration in this system is dependent upon the mini-donor DNA having IN recognition sequences at both ends and upon both ends of the same donor integrating into the acceptor DNA. The integrated DNA product exhibits all of the features associated with integration of viral DNA in vivo (P. Hindmarsh et al., J. Virol., 73:2994–3003, 1999). Individual integrants are isolated from bacteria containing drug-resistant markers with amber mutations. This system was used to evaluate the importance of sequences in the terminal U5 and U3 long terminal repeats at positions 5 and/or 6, adjacent to the conserved CA dinucleotide. Base-pair substitutions introduced at these positions in U5 result in significant reductions in recovered integrants from bacteria, due to increases in one-ended insertion events. Among the recovered integrants from reactions with mutated U5 but not U3 IN recognition sequences were products that contain large deletions in the acceptor DNA. Base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6 in U3 mostly reduce the efficiency of integration of the modified donor. Together, these results indicate that sequences directly 5′ to the conserved CA dinucleotide are very important for the process of concerted DNA integration. Furthermore, IN interacts with U3 and U5 termini differently, and aberrant end-processing events leading to nonconcerted DNA integration are more common in U5 than in U3.

The retrovirus encodes an enzyme, integrase (IN), that is both necessary and sufficient to catalyze the integration of viral DNA into the host chromosome. This enzyme forms a homodimer or a higher-order multimer, which recognizes the terminal sequences in the U3 and U5 long terminal repeats (LTRs). In most retroviruses, these sequences are related to one another in that they are nearly perfect inverted repeats. The minimum number of base pairs required for specific IN recognition varies from virus to virus and is between 10 and 20 (8, 9, 12, 15). Integration occurs as a concerted reaction, which is dependent on bringing both the U3 and U5 LTR ends from a single viral DNA into a complex with IN and acceptor DNA. Concerted DNA integration reactions have been reconstituted from purified components (1, 6, 7, 16). The simplest in vitro system utilizes purified avian sarcoma virus (ASV) IN, a host protein, high-mobility-group protein 1 (HMG-1) or HMG-I(Y), an acceptor DNA, and a small 300-bp donor DNA containing blunt ends with only 15 bp of the ASV U3 and U5 LTR termini (1, 10). A comparable system has been developed for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 IN (10). The products from these reactions exhibit all of the hallmarks of in vivo DNA integration. These include 3′ end processing, joining, and dependency on both LTR termini from a single donor DNA molecule, relative sequence-independent integration into the acceptor DNA, and small base-pair duplications of the acceptor DNA at the site of integration (1, 10). Vora et al. (16) described a separate ASV reconstituted integration system which utilized purified IN, an acceptor DNA, and a 480-bp DNA substrate containing NdeI-modified ends with two-base 5′ overhangs resembling processed U3 and U5 LTR termini. Concerted DNA products with this system arose from integration of two donor DNA molecules into the acceptor (16). In addition, complexes capable of catalyzing concerted DNA integration can be isolated from virus-infected cells. Such complexes, referred to as preintegration complexes, were shown to contain IN and the host protein, HMG-I(Y) (5).

Within the ASV U3 and U5 LTR terminal sequences, as with all retroviruses, there is a highly conserved CA dinucleotide at positions 3 and 4 relative to the 3′ termini. Previous in vivo studies demonstrated that base substitutions (underlined) in viral RNA placed adjacent to and including position 4 in the ASV U5 LTR (CTTCATT to GAAGATT) resulted in a delay in propagation of virus (4) most likely due to defects to initiation of reverse transcription and integration. Surprisingly, a smaller substitution of only two nucleotides at positions 5 and 6 (CTTCATT to CAACATT) caused a more pronounced growth defect than the four-base substitution. Analysis of end processing and joining reactions in vitro using duplex oligodeoxyribonucleotide substrates representing the terminal 15 bp of wild-type and mutated U5 LTRs also suggested that 2-bp substitutions caused a stronger defect in integration reactions than 4-bp substitutions (4, 12). The 4-bp substitution mutant was examined using the concerted DNA integration assay described by Aiyar et al. (1) in reactions stimulated by HMG-1 and was found to cause a small decrease in the efficiency of integration in vitro. More recently, Vora et al. (17) examined the effect of the U5 2-bp substitution using the NdeI-treated donor DNA and found that in contrast to the results in vivo, the 2-bp substitution appeared to increase the efficiency of integration in vitro. However, these and the above in vivo studies (4, 12, 17) provide little information about the effects of these mutations on the mechanism of integration.

We have now examined the effects of U5 base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6 on the process of integration by using the previously described concerted DNA integration assay (1, 10). We found that the 2- but not 4-bp substitutions increased the apparent frequency of integration when products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, thereby confirming the results of Vora et al. (17). However, combining the 2-bp U5 substitution mutation with a donor DNA that lacks the U3 IN recognition sequence resulted in an apparent efficiency of integration at least comparable to that of a wild-type donor substrate. Since a donor lacking the U3 IN recognition sequence is a poor substrate for two-ended concerted DNA integration (1), the above finding indicates that the U5 2-bp substitution promoted a significant increase in one-ended nonconcerted insertion events, which resulted from disrupting the normal integration complex. Similar but even more severe defects were obtained with a 1-bp substitution at U5 position 5 or 6. When comparable U3 2- and 4-bp substitutions at positions 5 and 6 and 4 to 7, respectively, were introduced into the U3 LTR, significant decreases in the efficiency of integration were detected and very few integrants were recovered after biological selection. This indicates that comparable mutations in U3 and U5 behave differently.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Bethesda, Md.) and MC1061/P3 (Invitrogen) were used for these studies. MC1061/P3 is a derivative of MC1061 containing the male episome, P3, which can be selected for the presence of an encoded kanamycin resistance gene. In addition, P3 possesses amp(Am) and tet(Am) genes, the expression of which can be rescued by the supF amber suppressor tRNA. Under these conditions, MC1061/P3 can be selected for ampicillin, tetracycline, and kanamycin resistance.

Reagents.

ASV IN was prepared by G. Merkel (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pa.) as described by Jones et al. (11). HMG-I(Y) was purified as described by Nissen et al. (14). HMG-1 was purified as described by Chow et al. (3). Proteinase K (30 U/mg) and glycogen were from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemical. Vent DNA polymerase (2 U/μl) was from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). Oligodeoxyribonucleotides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems synthesizer (purchased from Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, Tex, or Genosys Biotechnologies Inc., The Woodlands, Tex.). Oligodeoxyribonucleotides were purified by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by reverse-phase chromatography as previously described (1).

The oligodeoxyribonucleotides used in this study were U5(WT) (5′ AATGAAGCCTTCTGCTGGGCGGAGCCTATG 3′), U5(CTTC→CAAC) (5′ AATGTTGCCTTCTGCTGGGCGGAGCCTATG 3′), U5(CTTC→CTAC) (5′ AATGTAGCCTTCTGCTGGGCGGAGCCTATG 3′), U5(CTTC→CATC) (5′ AATGATGCCTTCTGCTGGGCGGAGCCTATG 3′), U5(CTTC→GAAG) (5′ AATCTTCCCTTCTGCTGGGCGGAGCCTATG 3′), U3(WT) (5′ AATGTAGTCTTATGCGTTGCCCGGATCCGG 3′), U3(CTAC→GATG) (5′ AATCATCTCTTATGCGTTGCCCGGATCCGG 3′), U3(CTAC→CATC) (5′ AATGATGTCTTATGCGTTGCCCGGATCCGG 3′), U3(CTAC→CAAC) (5′AATGTTGTCTTATGCGTTGCCCGGATCCGG 3′), U3(CTAC→CTTC) (5′AATGAAGTCTTATGCGTTGCCCGGATCCGG 3′), ΔU3 (5′AGCAATGGCAACAACGTTGCCCGGATCCGG 3′), U5seq (5′ TTCAAAAGTCCGAAA 3′), and U3seq (5′ AGAATTCGGCGTTGC 3′). U5(WT) and U3(WT) were used to prepare the wild-type donor DNA substrate; U5(CTTC→GAAG), U5(CTTC→CAAC), U5(CTTC→CTAC), U5(CTTC→CATC), U3(CTAC→GATG) U3(CTAC→CATC), U3(CTAC→CATC), and U3(CTAC→CATC) were used to prepare donor substrates with mutations in the U5 or U3 terminus, as indicated. In each case, the sequence refers to the 3′ cleaved strand of the U3 or the U5 LTR IN recognition sequence. Sequences at the U3 terminus in the ΔU3 construct differ substantially from wild type. U5seq (complementary to plasmid πvx nucleotides 116 to 130) and U3seq (complementary to plasmid πvx nucleotides 326 to 312) were used as sequencing primers. Donor DNAs lacking the U3 IN recognition sequence was prepared as previously described (1).

Plasmid constructions and preparations.

Plasmid Sp2, used as a template to amplify donor DNA, is a variation of pBCSK+ in which a wild-type ASV donor DNA PCR product was inserted into pBCSK+. This plasmid was propagated in E. coli MC1061/P3 under the conditions described above. The integration acceptor was plasmid pBCSK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), which was propagated in E. coli DH5α. Plasmids were purified with Qiaprep columns (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) according to manufacturer's instructions. The growth of E. coli DH5α containing pBCSK+ was selected for by addition of chloramphenicol (35 μg/ml).

Preparation of donor DNAs.

Integration donors were amplified by using thermostable Vent DNA polymerase and the primers listed above. For each PCR, 25 pmol of each primer and 50 ng of Sp2 DNA as the template were used. Vent DNA polymerase was used according to manufacturer's instructions. A total of 20 rounds of amplification were performed in each reaction: 3 rounds at 94°C for 2 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 17 rounds at 94°C for 2 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 45 s. The resultant product donor DNA was isolated after electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels run in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (10). The purified DNA (600 ng) was recovered using Qiaex-II resin (Qiagen) and then precipitated with ethanol. The recovered DNA was suspended in either TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) or deionized distilled water. The integration donors, which were approximately 300 bp in length, were internally labeled during the PCR by the inclusion of [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/ mmol, 10 mCi/ml; New England Nuclear, Boston, Mass.). The final concentrations of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates during amplification reactions were 0.25 mM each unlabeled dATP, dGTP, and dTTP. The final dCTP concentration was 0.0502 mM (12 Ci/mmol, 0.6 mCi/ml).

Standard integration reaction conditions.

The integration reaction conditions were similar to those described by Aiyar et al. (1). Briefly, 15 ng (0.15 pmol of ends) of donor was mixed with 50 ng of acceptor (0.02 pmol) and 180 ng of ASV IN (6 pmol) in a 26-μl preincubation reaction mixture containing, at final concentrations, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 166 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.05% Nonidet P -40, 1% glycerol, 1.6 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), and 3.3 mM EDTA. The IN was diluted in a buffer containing 30% glycerol, 0.5 M NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mM EDTA. Where specified, either HMG-1 or HMG-I(Y) was added to the reaction mixtures in the concentrations indicated. The preincubation reaction mixtures were placed on ice overnight. The volume of each preincubation mixture was then increased to 30 μl with the addition of MgCl2 to a final concentration of 6.7 mM, and the integration assay mixture was incubated at 37°C for 90 min. The reactions were stopped by increasing the volume to 150 μl by the addition of EDTA (final concentration of 4.25 mM), sodium dodecyl sulfate (final concentration of 0.44%), and proteinase K (final concentration of 0.06 mg/ml). After digestion for 60 min at 37°C, the reaction mixtures were extracted with phenol followed by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 mixture); 17 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) was added along with 1 μl of glycogen (10-mg/ml stock solution). The reaction products were precipitated by the addition of 400 μl of 100% ethanol and washed twice with 70% ethanol prior to electrophoresis and autoradiography. The reaction products were separated on a 1% agarose gel run in 0.5× Tris-borate, EDTA, and ethidium bromide at 10 V/cm for 2 h. Following electrophoresis, gels were submerged in 5% trichloroacetic acid for 20 min or until the bromophenol blue dye turned bright yellow. After being washed with water, the gels were dried on DE-81 paper (Whatman) in a Bio-Rad slab gel dryer at 80°C for approximately 2 h under vacuum. The dried gels were exposed to autoradiographic film overnight at −80°C in a film cassette with GAFMED TA-3 or Kodak midspeed screens.

Preincubation of IN with donor DNA.

In general, conditions for preincubation of IN with donor DNA were identical to those of our standard ASV integration reactions outlined above except that the acceptor DNA was omitted from the incubation on ice and the incubation volume was 25 μl. The reaction volumes were increased to 30 μl with the addition of 50 ng of acceptor (0.02 pmol) and MgCl2 as above, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 120 min.

Cloning and sequencing of integrants.

In all experiments, the integration products were used directly for transformation of bacteria after pooling several separate integration reactions. Integration products were introduced into E. coli MCI061/P3 by electroporation in a Bio-Rad electroporator with 0.1-cm electroporation cuvettes, 1.8-kV voltage, 25-mF capacitance, and 200-ohm resistance. The P3 episome is maintained at a low copy number. Therefore, only 40 μg of ampicillin, 15 μg of kanamycin, and 10 μg of tetracycline per ml were required for selection. Under these conditions, we detected no colonies after supF selection when the donor, acceptor, or donor and acceptor were electroporated into cells in the absence of IN. Plasmid DNAs were recovered from individual clones, and integration junctions were sequenced by using primers U3seq (for sequencing the U3 junction) and U5seq (for sequencing the U5 junction). Sequencing was performed using a Sequenase or Thermo-Sequenase kit as instructed by the manufacturer (U.S. Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio).

RESULTS

Reconstitution of ASV IN-dependent integration in vitro.

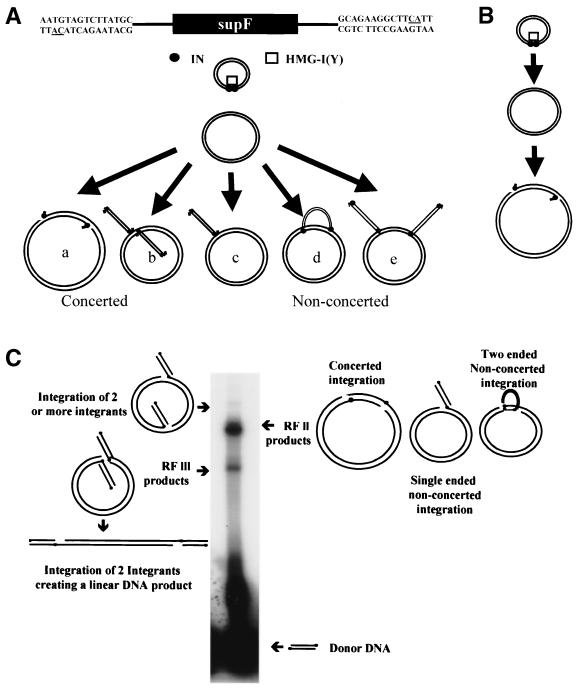

The ASV reconstituted concerted DNA integration system used in this study (Fig. 1A and B) utilizes a mini-donor DNA containing a supF transcription unit, a supercoiled plasmid acceptor replicative form I (RF I), purified E. coli-expressed ASV IN, and human HMG-I(Y) (1, 10). Products from these reconstituted reactions and their relative positions of migration as analyzed by gel electrophoresis are shown in Fig. 1C. The wild-type donor integrates into the acceptor DNA (Fig. 1C, RF II product) via a concerted mechanism using mostly a single donor DNA as depicted diagrammatically in Fig. 1A (product a). Less than 10% of the integrants found in the RF II products were previously shown to arise by a nonconcerted mechanism through either single or multiple donor one-ended insertion events (Fig. 1A, products c and e) (1, 10). Products c and d would migrate at the same position as product a, because a single donor has been inserted; product e would migrate more slowly since two donors are inserted into the target. Product d is a hypothetical intermediate in which a single donor integrates into a target, but with the ends of the donor being inserted at distant sites. The RF III product (1) (Fig. 1C) probably arises by concerted DNA integration of two donor DNAs integrating at the same site in the acceptor DNA as depicted in Fig. 1A (product b). When the products from a standard integration reaction are introduced into bacteria containing a P3 plasmid containing drug resistance markers with amber mutations, which can be suppressed in the presence of the supF tRNA transcription unit derived from the donor, individual integrants can be isolated and sequenced.

FIG. 1.

Reconstitution of ASV IN-dependent DNA integration with wild-type donor DNA. (A) A diagram of donor DNA showing the U3 (left) and (U5) LTR sequences is shown at the top. The highly conserved CA dinucleotide is underlined; the closed rectangle represents a supF tRNA transcription unit. The donor and acceptor DNAs were incubated on ice with IN and HMG proteins as described in Materials and Methods, and the integration reaction was initiated at 37°C with the addition of MgCl2. Below are diagrammatic representations of concerted DNA integration products resulting from use of both LTR termini from a single donor (product a) and from use of different LTR termini from two donors (product b) and of nonconcerted integration products resulting from one-ended integration from a single donor (product c), using both ends from a single donor with insertion at different sites on the acceptor DNA (product d), and using one-ended integration from two donors at different sites on the acceptor DNA (product e). (B) Modified integration reaction conditions where the acceptor DNA is introduced into the assay after preincubation overnight at 4°C. (C) Gel electrophoresis analysis of integration products formed with a wild-type donor DNA. Positions of RF II and RF III forms of the acceptor DNA, the RF II and RF III products from integration of the wild-type donor into the acceptor DNA, and possible intermediates as shown in panel A are indicated. The radiolabel is in the donor DNA whose migration position is at the bottom of the gel.

Analysis of U5 base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6.

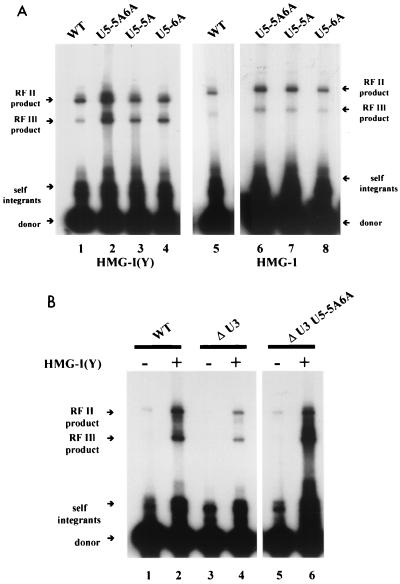

Using this in vitro system, we analyzed the effects of introducing base-pair substitutions into the donor at U5 positions 5 and 6 (CTTCATT→CAACATT) near the conserved CA dinucleotide. The ability of the modified donor to undergo integration in vitro, stimulated by HMG-I(Y), was 1.5- to 2-fold greater (Fig. 2A, lane 2) than observed with the wild type (Fig. 2A lane 1). This is similar to the results obtained by Vora et al. (17). However, if the U5 position 5 and 6 base-pair substitution mutation was combined with a donor DNA lacking the U3 IN recognition sequence, there was little or no decrease in the amount of integration product compared to a donor with a U5-5A6A and a wild-type U3 (Fig. 2B, lane 6). A donor DNA which contains only the wild-type U5 IN recognition sequence is considerably less efficient in supporting integration (Fig. 2B, lane 4) than a donor with both IN recognition sequences (Fig. 2B, lane 2) (1). A donor with a U5-5A6A, in the absence of the wild-type U3 termini, integrates at a greater efficiency than a donor with only a wild-type U5 terminius. Taken together, these results indicate that the base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6 alter concerted DNA integration, resulting in an increase in single or multiple U5-mediated one-ended donor insertion events. Note also that in each case the presence of the HMG-I(Y) protein stimulated integration of donors containing only the one LTR IN recognition sequence (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 to 6).

FIG. 2.

Gel electrophoresis analysis of integration products formed with wild-type and U5-substituted donor DNA. (A) Integration reactions under the standard conditions as described in the legend to Fig. 1A were carried out with 6 pmol of IN and 4 pmol of HMG-I(Y) with wild-type (WT) donor DNA (lane 1) or donor DNAs containing U5-5A6A (lane 2), U5-5A (lane 3), or U5-6A (lane 4) base-pair substitutions. Integration reactions were also carried out with 6 pmol of IN and 4 of pmol HMG-1 with wild-type donor DNA (lane 5) or donor DNAs containing U5-5AS6A (lane 6), U5-5A (lane 7), or U5-6A (lane 8) base-pair substitutions. (B) Integration reactions with (lanes 2, 4, and 6) or without (lanes 1, 3, and 5) HMG-I(Y) using a wild-type (WT) donor (lanes 1 and 2) or a donor DNA lacking the U3 IN recognition sequence but maintaining a wild-type U5 (lanes 3 and 4) or U5-5A6A (lanes 5 and 6) IN recognition sequence.

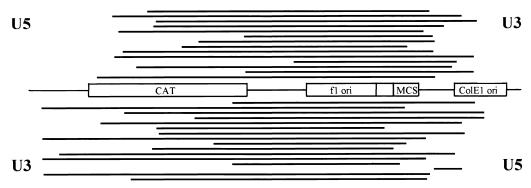

One-ended or multiple one-ended donor insertion products would be lost when introduced into bacteria. When integrants having the 5A6A substitution were electroporated into bacteria, the number of colonies recovered after supF selection was reduced to 25% relative to the wild-type donor (Table 1, standard reaction conditions with the acceptor DNA present during the preincubation). In addition, when DNA recovered from individual clones derived from HMG-I(Y)-stimulated reactions was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, about 20% of the RF I DNA migrated faster than an acceptor DNA containing a donor inserted by a concerted mechanism (data not shown). This suggested that deletions had been introduced into these acceptors, which was confirmed by direct nucleotide sequencing as summarized in Table 2. Sizes of the deletions ranged from 196 to 2,736 bp (Fig. 3). The deletion products lacked base-pair duplications at the sites of donor DNA insertion but contained characteristic 2-bp deletion from the ends of the LTRs. When wild-type donors were used, no such acceptor DNA deletions were detected (10).

TABLE 1.

Effects of mutations on recovery of integrants after biological selectiona

| HMG protein | Mutation in donor DNA | Recovered colonies (% of wild type)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | ||

| HMG-I(Y) | None | 100b | 100c |

| U5-5A6A | 25 | 65 | |

| U5-5A | 15 | 40 | |

| U5-6A | 15 | 20 | |

| U3-5T6A | 11 | NDd | |

| U3-4G5T6A7G | 0 | ND | |

| U3-6A | 35 | ND | |

| U3-5T | 0 | ND | |

| HMG-1 | None | 100b | 100e |

| U5-5A6A | 4 | 23 | |

| U5-5A | ND | 12 | |

| U5-6A | ND | 17 | |

| U3-5T6A | 11 | ND | |

| U3-4G5T6A7G | 0 | ND | |

Integration reactions with wild-type and mutant donor DNAs were introduced into bacteria in the presence (+) or absence (−) of acceptor DNA in preincubation, and individual integrants were isolated as described in Materials and Methods. The sequences of individual integrants are presented in Tables 2 to 5.

Wild-type data from reference 10; 100% defined as 75 colonies/plate derived from reaction products as described in Materials and Methods.

Wild-type data from reference 1; 100% defined as 25 colonies/plate derived from modified reaction conditions as described in Materials and Methods.

ND, not determined.

Wild-type data from incubation conditions that included the acceptor DNA during the preincubation.

TABLE 2.

Sites of integration, in the presence of HMG-I(Y), with donor DNA containing U5-5A6A substitutions

| HMG protein | Sequence of donor-acceptor junctionsa

|

Base-pair duplications in acceptor DNA | Plasmid position of integration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U5 | U3 | |||

| HMG-1(Y) | tcccgACAAC | CTACAagggc | 5 | 2900–2904 |

| cgtatACAAC | CTACAgcata | 5 | 877–881 | |

| agtatgACAAC | CTACAtcatac | 6 | 3268–3273 | |

| ccttccACAAC | CTACAggaagg | 6 | 490–495 | |

| gaccccACAAC | CTACActgggg | 6 | 893–898 | |

| atttagACAAC | CTACAtaaatc | 6 | 50–55 | |

| ccttccACAAC | CATAAGAggaagg | 6 | 490–495c | |

| ccgctaACAAC | CATAAGAggcgat | 6 | 2685–90c | |

| gacgcgACAAC | CTACAccctgc | 0b | U3-2908, U5-1501d | |

| accacaACAAC | CTACAgtgagc | 0 | U3-909, U5-1970 | |

| cgcgcgACAAC | CTACAcatacg | 0 | U3-2349, U5-619 | |

| HMG-1 | gactccACAAC | CTACAaaaggc | 0 | U3-1175, U5-2998 |

| tcgaccACAAC | CTACAgggcgc | 0 | U3-1026, U5-2242 | |

| cgcctaACAAC | CTACActgcgc | 0 | U3-1059, U5-3331 | |

Deoxynucleotide sequence of the junction of the donor integration into the acceptor DNA. Sequences for only the 3′ cleaved strands of the duplex for U5 and U3 are shown; therefore, the complementary strands of the duplex are presented. Lowercase letters denote duplication of the cell DNA; uppercase letters indicate the processed viral DNA sequences, which have lost 2 bp from each end unless otherwise indicated; boldface letters indicate that IN utilizes an internal GA dinucleotide for integration. The recovery of integrants after biological selection was 25 or <5% of the wild-type level in the presence of HMG-I(Y) or HMG-1, respectively.

Zero denotes no base-pair duplication indicative of a nonconcerted DNA integration mechanism.

Denotes 7-bp deletion in donor DNA in the U3 LTR that uses the first internal CA dinucleotide.

Denotes deletion introduced into the acceptor DNA.

FIG. 3.

Deletions introduced into the acceptor DNA by nonconcerted DNA integration of mutated donors. The solid horizontal lines represent deletions from individual integrants as depicted above or below the plasmid map. The plasmid acceptor DNA is as described in the legend to Fig. 4.

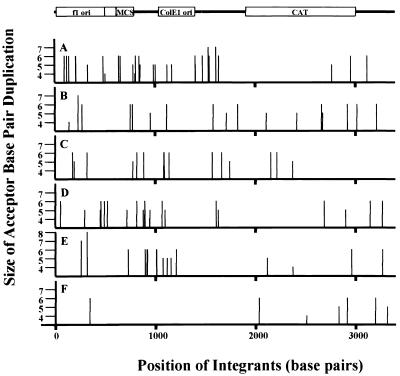

Of the concerted DNA integration products recovered and sequenced, the mutations were still present, and as with the wild type, there were duplications introduced into the acceptor at the site of donor insertion and 2 bp removed from the ends of the LTRs (Table 2A). Sizes of the base-pair duplications in the acceptor and the distribution of the sites of insertion of the U5-5A6A donors were similar to those for the wild type (Fig. 4). When the same U5-5A6A mutated donor DNA was analyzed in reactions stimulated by HMG-1, an increase in total integration products was also noted (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 5 and 6). However, after biological selection, the number of recovered integrants was reduced to 4% of the wild-type value (Table 1, standard conditions), and those few integrants recovered arose by a nonconcerted DNA integration mechanism introducing deletions into the acceptor DNA (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

Sites of concerted integration of wild-type and mutant donor ASV DNA. The locations and lengths of flanking duplications of plasmid DNA for integrants using wild-type (A) and mutant ASV donor DNAs with base pair substitutions U5-5A6A (B), U5-5A (C), U5-6A (D), U3-5T6A (E), and U3-6A (F) as described in Tables 2 to 5 are presented. Data for wild-type ASV are from Aiyar et al. (1) and Hindmarsh et al. (10). The plasmid acceptor data are drawn in a linear representation to scale. The genes of the plasmid and origin of replication (ori) are indicated by open boxes. MCS, multiple cloning site. The thick vertical lines represent numbers of nucleotides in the plasmid DNA. Each thin vertical line represents a separate sequenced integration event. Lengths of the thin vertical lines represent 4-, 5-, 6-, or 7-bp duplications of the acceptor DNA as indicated.

Analysis of U5 base-pair substitutions at position 5 or 6.

A similar in vitro analysis was performed with donor DNAs that contained single-base-pair substitutions at position 5 or 6. In contrast to the results described above, there was no difference in the total integration products compared to wild type in HMG-I(Y)-stimulated reactions analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Nevertheless, when introduced into bacteria, the number of recovered colonies compared to wild type was reduced to 15% (Table 1, standard conditions) for both mutant donors, and the majority of those integrants recovered from bacteria and sequenced contained deletions in the acceptor DNA (Table 3). We detected only one concerted DNA integration product with a donor DNA containing a base-pair substitution at position 5 and one with a base-pair substitution at position 6, though in the latter instance there was a concomitant 5-bp deletion in the U5 IN recognition sequence.

TABLE 3.

Sites of integration, in the presence of HMG-I(Y), with donor DNA containing U5-5A substitutiona

| Substitution | Sequence of donor-acceptor junctions

|

Base-pair duplications in acceptor DNA | Plasmid position of integration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U5 | U3 | |||

| U5-5A | tggtagtACATC | CTACAaccatca | 7 | 232–238 |

| aactcaACATC | CTACAggccag | 0 | U3-1178, U5-2092 | |

| tcgctcACATC | CTACAtggccag | 0 | U3-1707, U5-1043 | |

| ccaaggACATC | CTACAcctgcc | 0 | U3-2907, U5-1183 | |

| ctatatACATC | CTACAgggtgc | 0 | U3-896, U5-2149 | |

| tctgccACATC | CTACAcgtgcc | 0 | U3-970 U5-2363 | |

| gctataACATC | CTACAgctaat | 0 | U3-1586, U5-696 | |

| atacccACATC | CTACAcgttgc | 0 | U3-1201, U5-2380 | |

| tcgcctACATC | CTACAgctctg | 0 | U3-1591, U5-842 | |

| ccccccACATC | CTACAccctga | 0 | U3-2903, U5-622 | |

| U5-6A | tgccccACGGA | CTACAacgggg | 6 | 319–324b |

| aaaaacACTAC | CTACAgatata | 0 | U3-2158, U5-1247 | |

| tcgactACTAC | CTACAccaggc | 0 | U3-8961, U5-1092 | |

| aaaaacACTAC | CTACAcatggt | 0 | U3-2643, U5-1247 | |

| tcgactACTAC | CTACAccaggg | 0 | U3-1995, U5-1092 | |

| aggcgaACTAC | CTACAatacct | 0 | U3-1598, U5-869 | |

| tggcccACTAC | CTACAagctca | 0 | U3-1094, U5-2078 | |

| aagcagACTAC | CTACAggggat | 0 | U3-717, U5-2559 | |

| tccacgACTAC | CTACAtgagtg | 0 | U3-906, U5-2674 | |

| ttagcgACTAC | CTACAcccata | 0 | U3-2380, U5-556 | |

Boldface indicates that IN utilizes an internal CA dinucleotide for integration. All other notations are as for Table 2.

Denotes 5-bp deletion in donor DNA in the U5 LTR.

Preintegration incubation of IN with donor DNA.

We considered the possibility that formation of one-ended or other nonconcerted DNA integration products with U5-modified donor DNA (Fig. 2B) may be caused by a failure of IN to form multimeric complexes that bring the two LTR termini together. Since IN is a strong nonspecific DNA binding protein, we tried to correct the defect by increasing the relative specific activity of IN to the donor DNA ends by omitting the acceptor DNA from the preincubation on ice (Fig. 1B). It was added instead after the preincubation period along with MgCl2 to start the reaction at 37°C as described in Materials and Methods. Under these modified conditions using a wild-type donor, the total number of colonies recovered from bacteria was reduced to about one-third of the number found under standard conditions, which included the acceptor DNA in the first preincubation on ice. All of the recovered integrants sequenced were formed by a concerted integration reaction (Table 1). When integrants were derived from reactions with donors containing base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6 or at either position 5 or 6 of the U5 IN recognition sequence, under the modified preincubation conditions, the recovery of colonies approached wild-type levels. Also, most sequenced integrants arose by a concerted mechanism; this was particularly noticeable in reactions with U5-5A6A-substituted donor and HMG-1, U5-5A-substituted donor and HMG-I(Y), and U5-6A-substituted donor and HMG-I(Y) (Table 4). The sites of insertion in the acceptor DNA were again widely distributed (Fig. 4), and the sizes of the base-pair duplications were similar to those obtained with a wild-type donor DNA.

TABLE 4.

Sites of integration, in the presence of HMG-I(Y) or HMG-1, with donor DNA containing U5-5A6A, U5-5A, or U5-6A substitutions preincubated without acceptor DNAa

| HMG protein | Substitution | Sequence of donor-acceptor junctions

|

Base-pair duplications in acceptor DNA | Plasmid position of integration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U5 | U3 | ||||

| HMG-I(Y) | U5-5A6 | ccctgACAAC | CTACAgggac | 5 | 449–453 |

| actcgACAAC | CTACAtgagc | 5 | 1095–1099 | ||

| cgatgtACAAC | CTACAgctaca | 6 | 1608–1613 | ||

| cgtggACAAC | CTACAgcacc | 5 | 897–901 | ||

| accccACAAC | CTACAtgggg | 5 | 894–898 | ||

| aggggggACAAC | CTACAtcccccc | 7 | 663–669 | ||

| ccgcacACAAC | CTACAggcgtg | 6 | 2323–2328 | ||

| acggACAAC | CTACAtgcc | 4 | 3019–3022 | ||

| atttagACAAC | CTACAtaaatc | 6 | 50–55 | ||

| cgctaACAAC | CTACAggcgat | 6 | 435–440 | ||

| atcgccACAAC | CATAAGAatcgcc | 6 | 440–445b | ||

| ccttcccACAAC | CATAAGAggaaggg | 7 | 490–496b | ||

| accggACAAC | CATAAGAtggcc | 5 | 1629–1633b | ||

| HMG-1 | U5-5A6A | ataatgACAAC | CTACAcaaggg | 0 | U3-2396, U5-1110 |

| taatgcACAAC | CTACAattacg | 6 | 519–524 | ||

| gggtgaACAAC | CTACAcccact | 6 | 3144–3149 | ||

| ggcccACAAC | CTACAccggg | 5 | 714–718 | ||

| ttgctgACAAC | CTACAaacgac | 6 | 1068–1073 | ||

| gcagggACAAC | CTACAcgtccc | 6 | 456–461 | ||

| tgacACAAC | CTACAactg | 4 | 941–944 | ||

| ccctgcACAAC | CTACAgggacg | 6 | 456–461 | ||

| cgcccACAAC | CTACAgcggg | 5 | 945–949 | ||

| tttccACAAC | CTACAaaagg | 5 | 293–297 | ||

| agtatcACAAC | CTACAtcatag | 6 | 813–818 | ||

| cttaacACAAC | CTACAgaaatg | 0 | U3-2200, U5-850 | ||

| gggcggACAAC | CTACAccggaa | 0 | U3-871, U5-2320 | ||

| ctaagACAAC | CTACActccct | 0 | U3-774, U5-1328 | ||

| tccctcACAAC | CTACAtgatcg | 0 | U3-3139, U5-382 | ||

| HMG-I(Y) | U5-5A | cgactACATC | CTACAgctga | 5 | 2673–2677 |

| ggggcaACATC | CTACAccccgt | 6 | 3017–3022 | ||

| gaatcACATC | CTACActtag | 5 | 2111–2115 | ||

| gattcACATC | CTACActaaag | 6 | 774–779 | ||

| gaggtgACATC | CTACActccac | 6 | 752–757 | ||

| tggcatACATC | CTACAaccgta | 6 | 1114–1119 | ||

| ccccagACATC | CTACAggggtc | 6 | 1826–1831 | ||

| ccttccACATC | CTACAggaagg | 6 | 3213–3218 | ||

| attcgcACATC | CTACAtaagcg | 6 | 2921–2926 | ||

| tgacACATC | CTACAactg | 4 | 141–144 | ||

| gtcaaACATC | CTACAcagtt | 5 | 2418–2422 | ||

| tgaccACATC | CTACAactgg | 5 | 953–957 | ||

| aaatgcACATC | CATAAGAaaatgc | 6 | 269–274b | ||

| cagcgACATC | CATAAGAgtcgc | 6 | 2663–2667b | ||

| tcgcctACTAC | CTACAgctctg | 0 | U3-1591, U5-842 | ||

| U5-6A | caactaACTAC | CTACAgttgat | 6 | 2155–2160 | |

| tatacACTAC | CTACAatatg | 5 | 2374–2378 | ||

| gtcgatACTAC | CTACAcagcta | 6 | 816–821 | ||

| atggcgACTAC | CTACAtaccgc | 6 | 1086–1091 | ||

| atccatACTAC | CTACAtaggta | 6 | 2217–2222 | ||

| cccgcACTAC | CTACAgggcg | 5 | 191–195 | ||

| ggtcacACTAC | CTACAccagtg | 6 | 1568–1573 | ||

| cctgagACTAC | CTACAggactc | 6 | 175–180 | ||

| HMG-1 | U5-5A | tcgatACATC | CTACAagcta | 5 | 1712–1716 |

| cgattaACATC | CTACAgctaat | 6 | 1581–1586 | ||

| atgccACATC | CTACAtacgg | 5 | 1109–1113 | ||

| gagttACATC | CTACActgggg | 0 | U3-893, U5-2989 | ||

| ccttcgACATC | CTACAgtgaaa | 0 | U3-830, U5-2120 | ||

| U5-6A | catcgACTAC | CTACAgtagc | 5 | 1744–1748 | |

| gcgtccACTAC | CTACAcgcagg | 6 | 1142–1147 | ||

| ccatagACTAC | CTACAggtatc | 6 | 1665–1670 | ||

| aatcaACTAC | CTACAttagt | 5 | 776–780 | ||

| cacattACTAC | CTACAgtgtaa | 6 | 884–889 | ||

| tagtcgACTAC | CTACAatcagc | 6 | 1091–1096 | ||

| gacgtcACTAC | CTACAcctgcc | 0 | U3-2773, U5-707 | ||

IN was preincubated with donor as described in Materials and Methods. All notations are as for Table 2.

Denotes 7-bp deletion in donor DNA in the U3 LTR.

Analysis of U3 base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6 and at positions 4 to 7.

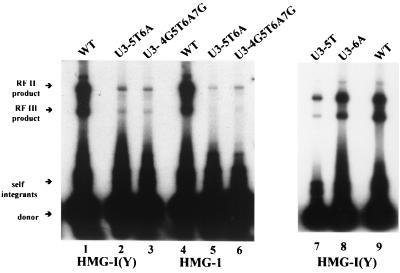

The U3 and U5 LTR termini are related to one another by being nearly perfect inverted repeats, and position 5 is one of three mismatched base pairs. We therefore prepared a series of U3-modified LTR substrates, which inverted the base pairs at position 5 and/or position 6, to determine whether this caused a similar defect observed with comparable substitutions introduced into U5. As seen after agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 5), for reactions with HMG-I(Y) using the standard assay conditions that included the acceptor in the preincubation, there is a substantial decrease in integration compared with wild type to less than 20% with the 2-bp substitutions (U3-5T6A) (compare lanes 1 and 2). Base-pair substitutions of positions 4 to 7 also caused a significant decrease in the efficiency of integration in vitro (compare lanes 1 and 3). In contrast, a single-base-pair substitution at position 5 in U3 caused about a 50% reduction in integration (lane 7) relative to use of a wild-type donor (lane 9). A single-base-pair substitution at position 6 had little detectable effect on the efficiency of integration (lane 8). Similar results were obtained when HMG-1 was used instead of HMG-I(Y) (lanes 4 to 6).

FIG. 5.

Effects of U3 LTR base-pair substitutions on integration into acceptor DNAs. Integration reactions as described in the legend to Fig. 2 were stimulated by HMG-I(Y) (lanes 1 to 3 and 7 to 9) or HMG-1 (lanes 4 to 6). Lanes 1, 4, and 7, wild-type (WT) donor DNA. Donor DNAs contained U3-5T6A (lanes 2 and 5), U3-4G5T6A7G (lanes 3 and 6), U3-5T (lane 7), or U3-6A (lane 8) base pair substitutions.

When integration products from HMG-I(Y)-stimulated reactions with mutant U3 donors were separately introduced into bacteria, individual integrants were recovered only for the 2-bp substitutions at positions 5 and 6 (U3-5T6A) and the 1-bp substitution at position 6 (U3-6A). The numbers of colonies recovered were reduced to approximately 11 and 35% relative to wild type (Table 1) for the U3-5T6A and U3-6A donors, respectively. No integrants were recovered for the single-base-pair substitution at position 5 (U3-5T donor). Because of the very low efficiency in collection of colonies, IN reactions were scaled up fourfold to obtain the clones whose sequences are shown in Table 5. Of the recovered integrants that were sequenced, all integrated by a concerted mechanism (Table 5). This was evidenced by the characteristic duplication of the acceptor DNA at the site of donor insertion. The distribution of integration sites in the acceptor and the sizes of the base-pair duplications at the sites of insertion for the U3-5T6A mutant were similar to wild-type results (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained with HMG-1-stimulated reactions except that fewer colonies were recovered (Tables 1 and 5).

TABLE 5.

Sites of integration, in the presence of HMG-I(Y) or HMG-1, with donor DNA containing U3-5T6A or U3-6A substitutionsa

| HMG protein | Substitution | Sequence of donor-acceptor junctions

|

Base-pair duplications in acceptor DNA | Plasmid position of integration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U5 | U3 | ||||

| HMG-I(Y) | U3-5T6A | gaaggcACTTC | CATCActtccg | 6 | 2962–2967 |

| cttcgACTTC | CATCAgaagc | 5 | 2116–2120 | ||

| atactcACTTC | CATCAtatgag | 6 | 3267–3272 | ||

| ggacttACTTC | CATCAcctgaa | 6 | 2516–2521 | ||

| ccagctcACTTC | CATCAggtcgag | 7 | 258–264 | ||

| caatcgACTTC | CATCAgttagc | 6 | 913–918 | ||

| aggggcagACTTC | CATCAtccccgtc | 8 | 318–325 | ||

| tataACTTC | CATCAatat | 4 | 2374–2377 | ||

| caatcgACTTC | ACGCAgttagc | 6 | 913–918b | ||

| HMG-1 | U3-5T6A | tccgccACTTC | CATCAaggcgg | 6 | 1010–1015 |

| ccacggACTTC | CATCAggtgcc | 6 | 897–902 | ||

| ccaaacACTTC | CATCAggtttg | 6 | 1014–1019 | ||

| cggtcgACTTC | CATCAgccagc | 6 | 1205–1210 | ||

| gagtgtACTTC | CATCAatcaca | 6 | 918–923 | ||

| tgtacACTTC | CATCAacatg | 5 | 1154–1158 | ||

| cgtcgACTTC | CATCAgcagc | 5 | 1076–1080 | ||

| atgccACTTC | CATCAtacgg | 5 | 1109–1113 | ||

| tcaagaACTTC | CATAAGAagttct | 6 | 731–736c | ||

| HMG-I(Y) | U3-6A | gggtctACTTC | CAACAcccaga | 6 | 3195–3200 |

| cggacACTTC | CAACAgcctg | 5 | 2830–2834 | ||

| taaattACTTC | CAACAatttaa | 6 | 2912–2917 | ||

| ctgttACTTC | CAACAgacaa | 5 | 3315–3319 | ||

| attctcACTTC | CAACGtaagag | 6 | 2033–2038d | ||

| aagagcACTTC | CAACGttctcg | 6 | 342–347d | ||

| ccacACTTC | CAACGggtg | 4 | 2506–2509d | ||

All notations are as for Table 2.

Denotes 12-bp deletion in donor DNA in the U3 LTR.

Denotes 7-bp deletion in donor DNA in the U3 LTR.

Denotes 16-bp deletion in donor DNA in the U3 LTR.

Base-pair deletions introduced into the donor DNA.

We had previously reported that when a 4-bp substitution was introduced into U5, a small number of concerted DNA integrants sequenced contained deletions in the donor DNA that were not observed with a wild-type substrate (1, 10). Such integrants all arose by a concerted DNA integration mechanism since they had the characteristic base-pair duplication in the acceptor DNA. In this study, of the 97 concerted DNA integrants that were sequenced, 14% contained deletions in the donor DNA (Tables 2 to 5). When base-pair substitutions were placed in position 5 or 6 or at positions 5 and 6 in U5, 6 of 67 concerted integrants contained the same 7-bp deletion in U3, to use the first internal GA dinucleotide for integration. One integrant contained a U5 deletion of 5-bp and used the first internal CA dinucleotide that was introduced by the base-pair substitution at position 6. Of the 25 integrants sequenced with U3 base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6 or position 6 alone, 5 contained base-pair deletions in the U3 region of the donor. One had the same 7-bp deletion as seen with U5 mutations using the GA dinucleotide, another had a 12-bp deletion to utilize an internal CA dinucleotide, and three had a 16-bp deletion using a CG dinucleotide for integration (Table 5). Thus, even though the CA dinucleotide is a highly conserved feature of an IN recognition sequence, it is not absolutely required for integration in this reconstituted system. For all but one LTR deletion integrant described above, the deletions appeared in the U3 IN recognition sequence regardless of whether the original site of mutation was in U3 or in U5. The reason for this asymmetry is not known. These LTR deletions were not observed in experiments using a wild-type donor.

DISCUSSION

IN, in the form of a dimer or larger multimer, forms a complex with the host cell acceptor DNA and the viral donor DNA. The positioning of IN on the acceptor allows for staggered breaks to be introduced, which determines the length of the base-pair duplications at the sites of integration. By juxtaposing both ends of the donor DNA together into the complex, the processing of the ends is closely linked (13) and the mechanism of integration is concerted. Introduction into either LTR terminus of mutations that alter the interaction with IN and that disturb the formation of multimer complexes that bring the two LTR ends together might affect the coordination of end processing and result in a significant increase in one-ended and other nonconcerted DNA integration events. Base-pair substitutions introduced at positions 5 and/or 6 in the U5 LTR termini have this phenotype. Integration in vitro with these modified U5 donors is largely independent of a second LTR terminus on the same donor, consistent with a disruption of the normal integration complex resulting in a preference for one-ended insertion events. This explains the increase in total RF II integrated products detected by gel electrophoresis analysis concomitant with a significant reduction in recovered integrants when introduced into bacteria. The gel analysis does not discriminate between one- or two-ended insertion events (see Fig. 1C), while only the latter would be recovered from bacteria. Thus, the 2-bp positions in the U5 IN recognition sequence adjacent to the conserved CA are very important for the mechanism of concerted DNA integration.

The concerted integration phenotype in vitro can be rescued by increasing the molar ratio of IN to donor DNA ends in the preincubation on ice. While we can drive the formation of the presumed multimeric complex of IN and donor DNA, it is at a cost of sharply reducing the efficiency of the in vitro integration reaction to a third of the wild-type level. Nevertheless, under these conditions almost all of the integrants recovered arose by a concerted mechanism.

Another consequence of introducing substitutions at positions 5 and/or 6 in the U5 IN recognition sequence can be seen among the integrants recovered from the standand reaction conditions. Approximately 20% of the sequenced integrants contained deletions in the acceptor. These events were not observed with a wild-type donor. The deletions observed were sizable, occasionally excising the majority of the acceptor plasmid, maintaining only segments of the ColE1 origin of replication (Fig. 3). This is explained by the fact that deletions introduced into the origin of replication would result in the loss of plasmid in the bacteria and hence loss of integrants. This is consistent with the finding that we also do not detect donor insertions into this region (Fig. 4). Deletions in the acceptor DNA could arise by several mechanisms. For example, both ends from a single donor DNA could integrate into the same acceptor DNA but at distal sites (Fig. 1A, hypothetical product d). Alternatively, two different donors could integrate into the same acceptor also at distal sites (product e). How the deletions are physically introduced is not known, but the relative positioning of the divergent insertion sites probably defines the size of the deletion.

In this study, we have found that single-base-pair substitutions at U5 position 5 or 6 caused more of an integration defect in vitro than the combination of the 2-bp substitutions in the same donor. This is evidenced by the percent decrease in recovery of colonies after the biological selection for each mutant donor reaction under the standard reaction conditions and by the sequences of recovered integrants. Among those sequenced, we found only nonconcerted DNA products with large acceptor deletions from reactions with the U5 donor base-pair substitutions at position 5 or 6. In contrast, we found both nonconcerted, with large acceptor deletions, and concerted DNA integration products from reactions with the U5 donor base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6. For U5 donor base-pair substitutions at positions 4 to 7, we previously reported that we detect only concerted DNA integration products (1). Thus, the four-base U5 substitution leaves the mechanism of integration mostly intact, while the overlapping two-base substitution at positions 5 and 6 causes a significant change in integration mechanism. These results are consistent with in vivo analysis of the comparable mutations introduced into the ASV genome, where the substitutions at positions 5 and 6 caused a greater delay of virus growth than the substitutions at positions 4 to 7 (4).

Similar substitutions at positions 5 and/or 6 in the U3 IN recognition sequence under the standard assay conditions caused reductions both in total integration products observed on the gels and in recovered integrants from the bacteria. In fact, the reductions caused by the U3 mutations were greater than found for comparable substitutions placed in the U5 IN recognition sequence. Since it is known that the wild-type U3 IN recognition sequence is processed by ASV IN more efficiently than the U5 IN recognition sequence, this result is not surprising. This finding does highlight the difference in recognition of the terminal U3 and U5 sequences by IN, but an explanation for these differences awaits structural information of IN with a bound substrate.

The in vitro reconstituted system used in this study employs HMG proteins as cofactors. Several HMG proteins, including HMG-1, -2, and -I(Y), stimulate integration in vitro (1, 10). In this study, we have found that there is a quantitative difference among the different HMG proteins in response to the base-pair substitutions at positions 5 and 6 in U5. If there is a tendency of an in vitro integration system to favor nonconcerted integration in the presence of HMG-1 or HMG-2, this tendency can be partly reversed by the presence of HMG-I(Y) (reference 10 and this study). Coupled with the finding of HMG-I(Y) in preintegration complexes (5), these results are consistent with HMG-I(Y) rather than HMG-1 serving as a cofactor for integration in vivo. The DNA binding domains of the HMG-1 and HMG-I(Y) proteins have markedly different three-dimensional structures and somewhat different DNA binding properties (2). HMG-1 proteins interact in a sequence-independent manner with the minor groove of DNA, whereas HMG-I(Y) proteins bind preferentially to the minor groove of AT-rich regions of B-form DNA. Therefore, one possible explanation for the above differences could be that HMG-I(Y) but not HMG-1 can recognize and preferentially bind AT-rich stretches, which are abundant in the donor termini (2). We have previously shown that HMG-I(Y) and IN do not interact directly in a ternary complex in which each is bound to the DNA (10). We suspect that HMG proteins function in vivo and in vitro as either DNA bending proteins, aiding in bringing the two ends of the donor together, or alternatively by melting the ends of the LTR termini and facilitating the end-processing step of integration. The finding that HMG-I(Y) proteins stimulate integration of donor DNAs lacking one of the two LTR IN recognition sequences suggests that the mechanism by which HMG proteins act is more through facilitating end processing and joining than by bending DNA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health research grants CA-38046 (J.L.) and GM46352 (R.R.).

We thank Anna Marie Skalka and George Merkel for the generous gift of ASV integrase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiyar A, Hindmarsh P, Skalka A M, Leis J. Concerted integration of linear retroviral DNA by the avian sarcoma virus integrase in vitro: dependence on both long terminal repeat termini. J Virol. 1996;70:3571–3580. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3571-3580.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bustin M, Reeves R. High-mobility-group chromosomal proteins: architectural components that facilitate chromatin function. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1996;54:35–100. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow C S, Barnes C M, Lippard S J. A single HMG domain in high-mobility group 1 protein binds to DNAs as small as 20 base pairs containing the major cisplatin adduct. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2956–2964. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobrinik D, Aiyar A, Ge Z, Katzman M, Huang H, Leis J. Overlapping retrovirus U5 sequence elements are required for efficient integration and initiation of reverse transcription. J Virol. 1991;65:3864–3872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3864-3872.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farnet C M, Bushman F D. HIV-1 cDNA integration: requirement of HMG I(Y) protein for function of preintegration complexes in vitro. Cell. 1997;88:483–492. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81888-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald M L, Vora A C, Zeh W G, Grandgenett D P. Concerted integration of viral DNA termini by purified avian myeloblastosis virus integrase. J Virol. 1992;66:6257–6263. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6257-6263.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodarzi G, Im G J, Brackmann K, Grandgenett D. Concerted integration of retrovirus-like DNA by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol. 1995;69:6090–6097. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6090-6097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heuer T S, Brown P O. Mapping features of HIV-1 integrase near selected sites on viral and target DNA molecules in an active enzyme-DNA complex by photo-cross-linking. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10655–10665. doi: 10.1021/bi970782h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heuer T S, Brown P O. Photo-cross-linking studies suggest a model for the architecture of an active human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase-DNA complex. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6667–6678. doi: 10.1021/bi972949c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hindmarsh P, Ridky T, Reeves R, Andrake M, Skalka A M, Leis J. HMG protein family members stimulate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and avian sarcoma virus concerted DNA integration in vitro. J Virol. 1999;73:2994–3003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2994-3003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones K S, Coleman J, Merkel G W, Laue T M, Skalka A M. Retroviral integrase functions as a multimer and can turn over catalytically. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16037–16040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzman M, Katz R A, Skalka A M, Leis J. The avian retroviral integration protein cleaves the terminal sequences of linear viral DNA at the in vivo sites of integration. J Virol. 1989;63:5319–5327. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5319-5327.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kukolj G, Skalka A M. Enhanced and coordinated processing of synapsed viral DNA ends by retroviral integrases in vitro. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2556–2567. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.20.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nissen M S, Langan T A, Reeves R. Phosphorylation by cdc2 kinase modulates DNA binding activity of high mobility group I nonhistone chromatin protein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19945–19952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman P A, Fyfe J A. Human immunodeficiency virus integration protein expressed in Escherichia coli possesses selective DNA cleaving activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5119–5123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vora A C, McCord M, Fitzgerald M L, Inman R B, Grandgenett D P. Efficient concerted integration of retrovirus-like DNA in vitro by avian myeloblastosis virus integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4454–4461. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.21.4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vora A C, Chiu R, McCord M, Goodarzi G, Stahl S J, Mueser T C, Hyde C C, Grandgenett D P. Avian retrovirus U3 and U5 DNA inverted repeats. Role of non-symmetrical nucleotides in promoting full-site integration by purified virion and bacterial recombinant integrases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23938–23945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]