Abstract

Energy-intensive technologies and high-precision research require energy-efficient techniques and materials. Lens-based optical microscopy technology is useful for low-energy applications in the life sciences and other fields of technology, but standard techniques cannot achieve applications at the nanoscale because of light diffraction. Far-field super-resolution techniques have broken beyond the light diffraction limit, enabling 3D applications down to the molecular scale and striving to reduce energy use. Typically targeted super-resolution techniques have achieved high resolution, but the high light intensity needed to outperform competing optical transitions in nanomaterials may result in photo-damage and high energy consumption. Great efforts have been made in the development of nanomaterials to improve the resolution and efficiency of these techniques toward low-energy super-resolution applications. Lanthanide ion-doped upconversion nanoparticles that exhibit multiple long-lived excited energy states and emit upconversion luminescence have enabled the development of targeted super-resolution techniques that need low-intensity light. The use of lanthanide ion-doped upconversion nanoparticles in these techniques for emerging low-energy super-resolution applications will have a significant impact on life sciences and other areas of technology. In this review, we describe the dynamics of lanthanide ion-doped upconversion nanoparticles for super-resolution under low-intensity light and their use in targeted super-resolution techniques. We highlight low-energy super-resolution applications of lanthanide ion-doped upconversion nanoparticles, as well as the related research directions and challenges. Our aim is to analyze targeted super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped upconversion nanoparticles, emphasizing fundamental mechanisms governing transitions in lanthanide ions to surpass the diffraction limit with low-intensity light, and exploring their implications for low-energy nanoscale applications.

Subject terms: Super-resolution microscopy, Nanoparticles

Introduction

Energy-intensive technologies such as data centers, illumination, transportation, and manufacturing require the development of sustainable processes enabled by energy-efficient techniques and materials1–5. Lower energy use in biology research and practices prevents damage to the samples and organisms being investigated while ensuring high precision and reliability, particularly for nanometer-scale studies6–8. Optical technology has been a driving force behind various developments that improve resolution and throughput while reducing energy consumption9–11. Among these, lens-based optical microscopy technology (Box 1) has shown to be useful for low-energy applications in the life sciences and other fields of technology such as light-enabled printing12–14, materials processing15,16, data storage17–19, and sensing20 among others. However, standard techniques cannot achieve applications at the nanoscale because of light diffraction21. Far-field super-resolution techniques22,23, including ‘stochastic’ and ‘deterministic’ (also known as ‘targeted’) techniques, have broken beyond the light diffraction limit, enabling 3D applications down to the molecular scale and striving to reduce energy use24–29.

Typically targeted super-resolution techniques use a focal excitation light intensity pattern featuring a strong spatial gradient to saturate optical transitions of nanomaterials to bright (‘activated’ or ‘ON’) and dark (‘inhibited’ or ‘OFF’) states30. These techniques have achieved high resolution, throughput, specificity, and selectivity, but the high light intensity needed to outperform competing optical transitions in nanomaterials may result in photo-damage and high energy consumption. Great efforts have been made in the development of nanomaterials with unique optical properties in order to improve the resolution and efficiency of targeted super-resolution techniques toward low-energy super-resolution applications31–35. The use of nanomaterials with excited energy states with long luminescence lifetimes can reduce the inhibition light intensity because the light intensity for saturation of inhibition is inversely proportional to the luminescence lifetime of the considered optical transitions36,37. Furthermore, the inhibition light intensity can be lowered using nanomaterials with a low light intensity threshold for saturation of inhibition38,39. A fundamentally different super-resolution approach is based on the use of nanomaterials that exhibit luminescence emission having a high order of non-linearity40,41. Such nanomaterials generate significant luminescence emission only at the spatial gradient maximum, that is from a region smaller than the size of the focal excitation light intensity pattern itself, resulting in enhanced resolution. This approach works without the need of inhibition light and shows promise for super-resolution applications using low-intensity light and simplified optical systems.

Among nanomaterials for targeted super-resolution techniques, lanthanide ion-doped upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) have shown unique physical, chemical, and optical properties42–44. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs are typically made of a host matrix, such as a rare earth oxide or fluoride, doped with trivalent lanthanide ions such as Yb3+, Er3+, and Tm3+45,46. These nanoparticles have distinctive electronic structures that feature a ladder-like arrangement of multiple excited energy states with long luminescence lifetimes ranging from microseconds to milliseconds or even longer. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs may convert photons with low photon energy like near-infrared (NIR) light into photons with higher photon energy like visible or ultraviolet (UV) light, producing upconversion luminescence (UCL) emission47–51. This process of photon upconversion of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs necessitates excitation with low-intensity light and low laser energy density, commonly referred to as fluence. Furthermore, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have high brightness and photostability, and low toxicity52–55. These features make lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs attractive for use in many low-energy applications in the life sciences as well as other fields of technology because they use low-photon energy NIR excitation to produce higher-photon energy visible and UV UCL emission, enabling deep light penetration while necessitating low laser energy density to minimize both photo-damage and energy consumption56–62. Various reviews have explored the fundamental principles of generating, tuning, and enhancing UCL emission, and the synthesis and functionalization methodologies of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs63–67. These studies also reported on the uses of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs and UCNP-based nanomaterials in fields such as bioimaging, theranostics, photonics, and sensing68–71. However, the existing literature lacks an analysis of super-resolution techniques involving lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, especially from a fundamental perspective. The discussion on the mechanisms governing transitions in lanthanide ions within UCNPs, allowing the surpassing of the fundamental diffraction limit with low-intensity light, is infrequent. Also, there is an absence of exploration into the potential implications of these mechanisms for low-energy applications at the nanometer scale.

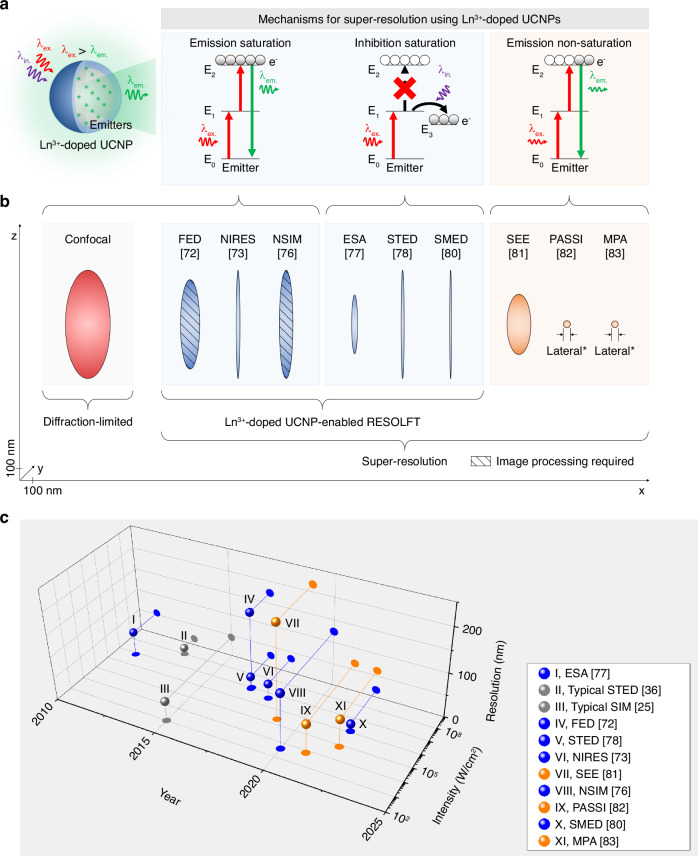

Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs allowed for the development of targeted super-resolution techniques that control optical transitions of lanthanide ions of UCNPs using excitation and inhibition light to achieve UCL emission saturation72–76, upconversion inhibition saturation77–80, and UCL emission non-saturation81–83 (Fig. 1a). UCL emission saturation occurs through upconversion from the ground energy state to an emitting excited energy state for excitation light intensity to saturate upconversion. Upconversion inhibition saturation occurs through the depletion of an intermediate excited energy state to a non-emitting energy state for inhibition of light intensity to saturate depletion. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNP-enabled targeted super-resolution techniques based on these two working principles are inspired by typical ‘reversible saturable optical (fluorescence) transition (RESOLFT)’ techniques22. UCL emission non-saturation occurs for excitation light intensity lower than that to saturate upconversion. Targeted super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have allowed for super-resolution in both the lateral (x,y) and axial (z) directions, with a minimum lateral resolution of below 20 nm80 (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Overview of the working principles and features of targeted super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs.

a Schematic of the use of excitation and inhibition light to control optical transitions of lanthanide ion emitters of UCNPs for targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission saturation, upconversion inhibition saturation, and UCL emission non-saturation. b Comparison of the 3D resolution achieved using different techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. The ellipsoids represent the lateral (x,y) and axial (z) resolution of the stated techniques. Diffraction-limited confocal microscopy is shown in red, assuming the case of typical Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs that show UCL emission at 450 nm excited at 980 nm. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNP-enabled targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission saturation, such as super-resolution FED microscopy72, NIRES nanoscopy73, and super-resolution NSIM76, or upconversion inhibition saturation, such as super-resolution ESA microscopy77, super-resolution STED microscopy78, and super-resolution SMED microscopy80, are shown in blue. Techniques based on UCL emission non-saturation, such as super-resolution SEE microscopy81, PASSI nanoscopy82, and MPA nanoscopy83, are shown in orange. c Timeline showing a comparison of the resolution and light intensity needed by different targeted super-resolution techniques including super-resolution STED microscopy36 and super-resolution SIM25 using typical fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials, and techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs72,73,76–78,80–83. *For PASSI nanoscopy and MPA nanoscopy, only the value of the achieved lateral resolution is reported82[,83. λex. excitation wavelength, λem. emission wavelength, λin. inhibition wavelength, FED fluorescence emission difference, NIRES near-infrared emission saturation, NSIM nonlinear structured illumination microscopy, ESA excited-state absorption, STED stimulated emission depletion, SMED surface-migration emission depletion, SEE super-linear excitation-emission, PASSI photon-avalanche single-beam super-resolution imaging, MPA migrating photon avalanche

Targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission non-saturation achieve super-resolution with a low light intensity of a few to tens of kW cm−2 and low energy density of ⁓10−8 J cm−2 to ⁓10−10 J cm−281–83 (Fig. 1c). In comparison, targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission saturation and upconversion inhibition saturation achieve super-resolution with a light intensity of up to ⁓10 MW cm−2 and an energy density of up to ⁓10−5 J cm−272–80. Targeted super-resolution techniques based on typical fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials achieve super-resolution with a light intensity of up to ⁓1–10 GW cm−236 and an energy density of ⁓10-4 J cm−284 to ⁓10−2 J cm−285. Furthermore, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs allow for achieving super-resolution using excitation and inhibition light from cheap and compact continuous-wave (CW) lasers, which is less damaging and reduces energy consumption, cost, and complexity of optical systems when compared to using light from expensive and bulky high-intensity pulsed lasers. The use of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs in targeted super-resolution techniques for low-energy super-resolution applications will have a significant impact on life sciences and other areas of technology. However, there are still some challenges that need to be addressed before lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs can be widely employed, such as improving their spatial resolution, optimizing their optical properties, and further reducing light intensity.

In this review, we describe the dynamics of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs for super-resolution under low-intensity light and their use in targeted super-resolution techniques. We highlight low-energy super-resolution applications of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, as well as the related research directions and challenges. Our goal is to offer the reader an analysis of super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, focusing on the fundamental aspects, including the mechanisms governing transitions in lanthanide ions within UCNPs to surpass the fundamental diffraction limit with low-intensity light. Also, we explore the potential implications of these mechanisms for low-energy applications at the nanometer scale.

Dynamics for super-resolution using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs

Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs exhibit complex physical and chemical dynamics under light irradiation, including interactions between lanthanide ion dopants and the host matrix, energy transfer between different lanthanide ions, upconversion, and additional processes such as multi-phonon relaxations, cross-relaxation (CR) between excited energy states, and energy transfers to impurities and quenchers. The discussed phenomena and underlying mechanisms of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs were previously examined, encompassing a review of both general and emerging strategies to exploit these phenomena and mitigate the related adverse effects86. Understanding and harnessing these dynamics of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs is crucial to achieve super-resolution under low-intensity light for low-energy super-resolution applications. Because of their linear absorption, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have a larger NIR absorption cross-section than that of typical multi-photon fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials87,88. The process of upconversion of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs involves the sequential absorption of multiple photons, which is mediated by multiple long-lived intermediate excited energy states of lanthanide ions and allows for the use of excitation and inhibition light from low-intensity CW lasers. As a result, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs avoid the critical need for simultaneous absorption of more than two photons from high-intensity pulsed lasers, resulting in several orders of magnitude lower light intensity threshold than that of typical multi-photon fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials89.

Targeted super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs are based on UCL emission through different mechanisms such as excited-state absorption (ESA), energy-transfer upconversion (ETU), and photon-avalanche (PA)42,90,91 (Fig. 2a). ESA involves excitation of a lanthanide ion through absorption in an already excited energy state. ETU involves energy transfer from one excited lanthanide ion called ‘sensitizer’, such as Yb3+ and Nd3+ ions, to a second neighboring lanthanide ion called ‘emitter’, such as Er3+ and Tm3+ ions, that results in excitation of the emitter to an excited state with higher energy and relaxation of the sensitizer to its ground energy state or excited state with lower energy. PA involves the excitation of a lanthanide ion through non-resonant ground-state absorption (GSA) and subsequent resonant ESA to an excited state with higher energy. CR between the excited lanthanide ion and a second neighboring lanthanide ion in its ground energy state results in both lanthanide ions occupying an excited energy state. The two lanthanide ions populate the excited state with higher energy in the first lanthanide ion to further initiate CR. This process exponentially increases the electronic population of the excited state with higher energy in the first lanthanide ion through ESA, resulting in high-intensity UCL emission.

Fig. 2. Analysis of the dynamics of optical transitions for super-resolution using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs.

a Schematic of the upconversion processes of ESA, ETU, and PA of targeted super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. b Summary of optical transitions of lanthanide ions of UCNPs, λex. (colored in red), λin. (colored in purple), and λem. (colored in green) of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs used in the demonstrations of targeted super-resolution techniques72–83. c Schematic of a simplified four-state system used to describe the dynamics of optical transitions for super-resolution using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs under excitation and inhibition light. d Schematic of the intensity saturation curve of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs that shows the relationship between IUCL and P under non-saturating and saturating light excitation. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with highly super-linear81 and PA82,83 UCL emission show n»1 under non-saturating light excitation

Targeted super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have overcome the light diffraction limit in 3D using different excitation and inhibition light wavelengths to control optical transitions of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs that show upconversion emission and inhibition from a wide range of lanthanide ions (Fig. 2b). A simplified model describing the dynamics of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs for super-resolution under low-intensity light is reported on the basis of a four-state system with a ground energy state E0 and three excited energy states Ei with i = 1–3 (Fig. 2c). It is assumed that the population density in the ground energy state N0 is constant, the system is pumped under CW light excitation through GSA, upconversion is achieved through ETU with parameters Wi for Ei, Ei has luminescence lifetime τi and decays with rate constant Ai = τi−1 either to the next lower excited energy state or to the ground energy state, and STED is considered as the mechanism for upconversion inhibition. The rate equations that describe upconversion excitation and inhibition in this system are:

Where Ni is the population density in Ei satisfying N0 + N1 + N2 + N3 = 1, ρp is the pump constant, σp is the absorption cross section from E0 at the pump wavelength, ρSTED is the STED constant, σSTED is the STED cross-section from E2 at the STED wavelength. ρp = (λp/hcπw2p)Ppump, where λp is the pump wavelength, h is Planck’s constant, c is the light speed, and wp is the pump beam radius. ρSTED = (λSTED/hcπw2STED)PSTED, where λSTED is the STED wavelength, and wSTED is the STED beam radius.

For upconversion excitation, the numerical solution of these rate equations gives that the IUCL that is excited by n photons that are absorbed sequentially depends on the pump light power P that is absorbed as IUCL ∝ Pi92. i ranges from i = n > 1 for infinitely small upconversion rates, that is the intermediate excited energy states depletion proceeds preferentially via luminescence emission rather than upconversion, to i ≤ 1 for infinitely large upconversion rates, that is the depletion of intermediate excited energy states proceeds preferentially via upconversion rather than luminescence emission. This dependency suggests that the optical transitions of lanthanide ions of UCNPs are saturated as the excitation light intensity increases. Upconversion saturation typically occurs under low-intensity light excitation in the range from tens to hundreds of kW cm−2. For upconversion excitation and inhibition, the electronic population in E2 is depleted to E0 through STED. The intensity ratio of UCL emission for the STED light beam switched ON and OFF, that is called ‘depletion ratio’, increases by rising the STED light beam intensity to saturate the depletion of E2 to E0 through stimulated emission. In principle, longer luminescence lifetimes enable to reduce the intensity of the STED light beam. Because the 4f-4f transitions of lanthanide ions of UCNPs are forbidden, they have long luminescence lifetimes ranging from tens of microseconds to milliseconds or longer. As a result, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs allow for mitigating the square root law which underpins resolution scaling in RESOLFT techniques.

The intensity saturation curve of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs shows the relationship between IUCL and P (Fig. 2d). In a log-log plot, the slope of such a curve at a certain P corresponds to the value of n, which typically indicates the order of non-linearity of upconversion. For low P, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs show weak IUCL. An increase of P under non-saturating light excitation results in an increase of IUCL with a super-linear regime. For lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs that show highly super-linear81 and PA82,83 UCL emissions, the slope is of n >> 1. When the excitation light beam intensity is within the highly super-linear range of the intensity saturation curve of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, only the central and most intense section of the excitation light beam produces a strong UCL emission. As a result, the UCL emission profile of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs is narrower and steeper than the excitation light beam profile, facilitating super-resolution under low-intensity light excitation. PA UCNPs show a clear excitation-power threshold Pth. above which a large non-linear increase in the excited-state population and UCL emission is observed with a steep slope of their intensity saturation curve. Further increase of P under saturating light excitation results in a linear regime with a slope of n = 1 for P = Ps, a sub-linear regime with a slope of n < 1 for P > Ps, and then over-saturation regime.

Targeted super-resolution techniques using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs

Targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission saturation

Super-resolution FED microscopy

Super-resolution FED microscopy relies on the intensity difference between two images called ‘solid’ and ‘donut’ images that are acquired by scanning the sample with solid and donut excitation light patterns, respectively93. Applying fluorescence saturation enhances the resolution capability of super-resolution FED microscopy94. This technique provides a straightforward pathway to super-resolution imaging without the need for high-depleting laser intensities. Additionally, it is independent to the species of agents, underscoring its versatility and promising potential. However, conventional fluorescent dyes used in super-resolution FED microscopy are prone to photobleaching, limiting their suitability for extended imaging, while high illumination intensities exacerbate this issue and pose risks of sample damage. Leveraging lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs shows great promise for super-resolution FED microscopy due to their outstanding photostability and efficiency of UCL emission when excited by NIR CW lasers.

Super-resolution FED microscopy was achieved based on UCL emission saturation using core-shell Nd3+/Yb3+/Er3+-doped UCNPs72. The Nd3+ ions in the shell absorbed energy from 808-nm excitation photons, which were then transferred to the Yb3+ ions in the core. From there, the energy was further transmitted from Yb3+ to Er3+ ions, enabling the UCL emission of green and red light. Solid, donut, and super-resolution FED point spread functions (PSFs) were simulated for saturated UCL emission of these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs under 808-nm laser excitation at an intensity of 10 MW cm−2 (Fig. 3a). The corresponding super-resolution FED PSF was obtained with a subtraction factor set to 0.83. Subsequently, a single lanthanide ion-doped UCNP was imaged using a solid light pattern at 10 MW cm−2 and a donut light pattern at the same intensity, and detecting UCL emission at 655 nm (Fig. 3b). The lateral resolution was 172 nm for saturated UCL emission under sequential solid and donut light pattern excitation with a light intensity of 10 MW cm−2 and with a subtraction factor of 0.83. The photostability of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs for super-resolution FED microscopy was examined under prolonged laser exposure lasting tens of minutes, with a laser beam intensity of 10 MW cm−2. The stability of UCL emission revealed no photobleaching or photoblinking behavior.

Fig. 3. Summary of targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission saturation of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs.

a Simulated solid, donut, and super-resolution FED PSFs, and corresponding intensity profiles of saturated UCL emission of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Adapted with permission from ref. 72 Copyright 2017 Optical Society of America72. b Solid, donut, and super-resolution FED microscopy imaging, and corresponding intensity profiles of saturated UCL emission of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Image size: 1.56 μm. Adapted with permission from ref. 72 Copyright 2017 Optical Society of America72. c Simulated ‘negative’ contrast images of cross-section profiles of the saturated UCL emission of a lanthanide ion-doped UCNP used in NIRES nanoscopy at different excitation intensity. Scale bar: 500 nm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 73, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature Limited73. d NIRES nanoscopy imaging and corresponding intensity profiles of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with different doping. Scale bar: 500 nm. Adapted with permission from ref. 73, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature Limited73. e Schematic of the super-resolution NSIM setup using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 76. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society76. f UCL emission imaging of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with 80 μm thick brain tissues under sinusoidal structured excitation and line profile of Fourier spectrum on a logarithmic scale of the diagonal cross-section profiles. Adapted with permission from ref. 76. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society76. g Wide-field and super-resolution NSIM imaging of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Scale bar: 2 μm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 76. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society76. h Comparison imaging results of the green framed area in (g), and corresponding intensity profiles of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Scale bar: 1 μm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 76. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society76

Sequential image acquisition is time consuming and may result in sample drift with image mismatch. One-scan super-resolution FED microscopy achieved super-resolution images simultaneously scanning core-shell Yb3+/Tm3+,Er3+-doped UCNPs with solid and donut excitation light patterns of two light wavelengths, and processing the two-color UCL emission solid and donut images95. The Er3+-doped NaYF4 core produced green UCL emission under excitation with an 808-nm laser beam, while the Yb3+/Tm3+-doped NaYF4 shell emitted blue UCL emission under 940-nm laser beam excitation. To prevent energy transfer between the Yb3+/Tm3+-doped shell and the Er3+-doped core, an inert NaYF4 isolation shell was implemented. The lateral resolution was of 54 nm for saturated UCL emission under the solid and donut light pattern excitation with a light intensity of 0.86 MW cm−2 and 1.78 MW cm−2, respectively. The corresponding super-resolution FED PSF was obtained with a subtraction factor set to 0.95. This approach proves advantageous for prolonged monitoring of live cells because of its drift-free and swift scanning capabilities, the non-bleaching properties exhibited by lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, and the use of low-intensity NIR CW excitation lasers. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with orthogonal UCL emission spectra under low-intensity light excitation show promise for high-throughput, parallel, multi-channel, low-energy super-resolution applications. This approach can readily integrate with current laser scanning microscopy systems, offering the potential to achieve real-time, low-power super-resolution microscopy through the implementation of instant subtraction in hardware or software.

NIRES nanoscopy, NIRB nanoscopy, and the fusion technique

Employing low-photon energy NIR excitation light enhances tissue penetration, reducing autofluorescence and minimizing phototoxicity for live-cell imaging. These principles are applied in fluorescence microscopy using multi-photon excitation (MPE) fluorescence emission, though the longer wavelength compromises resolution96,97. While MPE fluorescence microscopy can surpass diffraction limits when combined with techniques like super-resolution STED microscopy, it demands precise alignment and synchronization of high-intensity pulsed lasers, constrained by probe inefficiency. Unlike probes utilized in fluorescence microscopy employing MPE fluorescence emission, which produce fluorescence via simultaneous absorption under high-intensity pulsed laser irradiation, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs generate UCL emission through a sequential absorption process under low-intensity CW laser irradiation. Consequently, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs circumvent this limitation, offering significantly lower excitation thresholds compared to the most efficient multiphoton fluorescent probes. Moreover, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have the capability to produce UCL emission featuring narrow bandwidth and selectable spectral lines, even within the NIR range.

Taking advantage of these features of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, NIRES nanoscopy achieved super-resolution images with negative contrast scanning core Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs with a donut excitation light beam at 980 nm and detecting UCL emission at 800 nm73. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs converted 980-nm excitation photons absorbed by Yb3+ ions into 800-nm UCL emission photons originating from the two-photon state 3H4 of Tm3+ ions through an ETU process. In super-resolution imaging of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, NIRES nanoscopy used a tightly focused, donut-shaped excitation beam to scan lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs samples, producing negative contrast only when a single lanthanide ion-doped UCNP was precisely centered. Initially limited by diffraction at low excitation laser beam power, NIRES’ optical resolution can surpass this constraint with higher laser beam power through nonlinear excitation (Fig. 3c). The resolution of NIRES nanoscopy for a given excitation light intensity is defined by the intensity saturation curve of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Higher resolution is achieved with a smaller dark center of the donut emission light pattern decreasing the light power value to reach the half value of the maximum IUCL, and the maximum IUCL for a given light power value at half maximum. Furthermore, higher resolution is achieved with a lower depth of the donut emission light pattern increasing the onset of the curve, that is the value of light power to reach e−2 of the maximum IUCL. The lateral resolution was 34 nm for saturated UCL emission under the donut light beam excitation with a light intensity of 4 MW cm−2 (Fig. 3d). Moreover, enhancing the resolution is feasible through the optimization of lanthanide ion dopant concentration or by designing a tailored core-shell structure of the lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. This implies a vast potential for the materials science community to refine the resolution of NIRES nanoscopy.

NIRES-inspired NIRB nanoscopy achieved super-resolution images with negative contrast scanning core Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs with a Bessel donut excitation light beam at 980 nm and detecting UCL emission at 800 nm74. The use of such a ‘non-diffractive’ light beam and both excitation and emission at the NIR enable high penetration depth with minimal scattering and absorption. The lateral resolution was of 37 nm for saturated UCL emission under the Bessel donut light beam excitation with a light intensity of 10.88 MW cm−2. Moreover, NIRES-inspired nanoscopy achieved super-resolution images scanning core Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs and using the Fourier domain heterochromatic fusion technique75. When excited with a donut light beam at 980 nm with high light intensity, these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs exhibited UCL emission at 740 nm with a donut light pattern and at 800 nm with a Gaussian-like light pattern because the dark center of the donut was over-saturated. The fusion technique produced super-resolution UCL emission patterns by combining the higher- and low-frequency information from the donut and Gaussian-like UCL emission patterns in the Fourier domain, respectively. The lateral resolution was of 40 nm for saturated UCL emission at 800 nm under the donut light beam excitation with a light intensity of 2.75 MW cm−2. Moreover, by harnessing the substantial nonlinear response observed in lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, as evidenced by recent studies on PA effects82,83, the heterochromatic function strategy may significantly enhance imaging resolution.

Super-resolution NSIM

SIM uses periodic patterns to down-modulate high spatial frequency information in samples, aiding in the reconstruction of high-frequency details from multiple images acquired with patterned illuminations at varied angles, assisted by optical transfer functions. Recent advancements in denoising methods and modified excitation conditions have led to the development of new variants like NSIM25,98, Hessian-SIM99, grazing incidence SIM100, and multifocal light patterns101, known for their enhanced imaging speeds. Super-resolution NSIM achieves a resolution of around 50 nm by utilizing high excitation power to exploit nonlinear saturated photoresponse25. However, despite these advancements, deep-penetrating applications face challenges due to sample extinction, resulting in distorted illumination patterns, unwanted out-of-focus light, and reduced emission intensity, compromising both resolution and speed. NIR light MPE techniques, combined with spot scanning, address these challenges but at the expense of slower speed101. Organic fluorescent dyes and proteins, commonly used in SIM, require tightly focused, high-power pulsed lasers for MPE due to their small absorption cross-section. However, the high excitation power, particularly in NSIM, constrains the prolonged visualization of subcellular structures in living cells.

The utilization of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs has facilitated the development of a strategy for super-resolution NSIM, enabling fast super-resolution imaging with deep penetration. Super-resolution NSIM achieved super-resolution images with core Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs excited with a sinusoidal light pattern at 976 nm generated by a digital mirror device and detecting UCL emission by a camera76 (Fig. 3e). These lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs emitted UCL at 800 nm with high-frequency harmonic peaks in the Fourier transform. When an 80 μm tissue slice was laid atop a layer of lanthanide-ion doped UCNPs, the 800 nm emission pattern effectively reduced scattering while maintaining its pattern, showcasing superior penetration capabilities compared to typical visible UCL emission (Fig. 3f). The latter often suffers from significant distortion and nearly loses structural information. Fourier domain image analysis was used to quantify the information retained in emission patterns using super-resolution NSIM. The use of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with both 976-nm excitation and 800-nm UCL emission bands in the NIR range for super-resolution NSIM highlights their superiority over visible emissions, enabling the transmission and detection of structured excitation and emission patterns through thick tissue.

In comparison to the diffraction-limited wide-field imaging case achieved under uniform illumination (H = 0) and linear SIM (H = 1), the inclusion of additional harmonics H in upconversion NSIM (H ≥ 2) enhances the lateral resolution to approximately λ/[2NA(H + 1)], where NA is the numerical aperture. Adjusting the doping concentrations in lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs allowed for fine-tuning the nonlinearity of the photon response and UCL emission intensity. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with higher Tm3+ concentration exhibit stronger harmonic peaks owing to increased nonlinearity derived from enhanced energy transfer from Yb3+ to Tm3+ and improved CR between Tm3+ ions. However, higher doping concentrations often lead to lower emission intensity when using mild excitation power. To achieve an optimized balance between nonlinearity and brightness for imaging quality, a midlevel doping concentration of 4% was selected. Further enhancement in UCL emission intensity was achieved by adjusting the doping concentration of Yb3+ ions to 40%, as the optimized Yb3+ concentration increased the energy transfer rate from Yb3+ to Tm3+ ions. Wide-field and super-resolution imaging of the 4% Tm-doped UCNPs was conducted (Fig. 3g). The lateral resolution was 124 nm for saturated UCL emission under the sinusoidal light pattern excitation with a light intensity of 4 kW cm−2 (Fig. 3h). In comparison to studies focused on single-point scanning nanoscopy utilizing NIR excitation and NIR UCL emission73–75, super-resolution NSIM works without the need for light beam control and achieves higher rates. Furthermore, it uses low excitation light intensity to keep increase of tissue temperature below 3 °C, safe for long-term tracking in living cells102,103. Increasing imaging speed with higher excitation power may result in strong photothermal effects. Enhancing the brightness of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs under low power and applying denoising algorithms like Hessian deconvolution and multifocal patterns104 can improve speed and resolution. This method can also enhance imaging depth in various techniques like light sheet-based SIM105 and adaptive optics106,107.

Targeted super-resolution techniques based on upconversion inhibition saturation

Super-resolution ESA microscopy

Super-resolution ESA microscopy shares similarities with super-resolution STED microscopy in its approach to achieving super-resolution. Both techniques employ a dual-beam setup, with a Gaussian laser beam for excitation and a donut laser beam for inhibition, to selectively activate and deactivate luminescence emission. However, super-resolution ESA microscopy diverges significantly from super-resolution STED microscopy by relying on the principle of stimulated absorption rather than the principle of stimulated emission. Super-resolution ESA microscopy achieved super-resolution images scanning Pr3+-doped UCNPs with a time-gated 609-nm Gaussian excitation laser beam, a 532-nm donut inhibition laser beam, and a 532-nm Gaussian excitation laser beam, and detecting UV UCL emission77. The UCL emission mechanism involved two sequential excitation steps of Pr3+ ions (Fig. 4a)108. Firstly, a laser beam at 609 nm triggered the transition of Pr3+ ions to their 1D2 state, characterized by a long lifetime of approximately 150–200 μs. Subsequently, another laser beam at 532 nm facilitated the transition to the emitting 4f5d(1) level, possessing a short lifetime of approximately 18 ns and near-unity UCL emission quantum efficiency. For super-resolution imaging of Pr:YAG nanoparticles, a pulsed 609-nm Gaussian excitation laser beam was used to populate the intermediate excited energy state of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, while a CW 532-nm donut inhibition laser beam was used to deplete such a state through ESA except for lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs at the center of the donut. Another pulsed 532-nm Gaussian excitation laser beam excited lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with a remaining electronic population in the intermediate excited energy state into the emitting excited energy state for UCL emission. Concurrently, photon counts at a photo-detector were selectively gated to include only those photons arriving within a few tens of nanoseconds after the readout pulse, thereby contributing to the readout signal (Fig. 4b). The lateral resolution was 54 nm for saturated upconversion inhibition through ESA to the emitting excited energy state (Fig. 4c). After hours of continuous illumination, there was no change in the UCL emission intensity observed, demonstrating the photostability of Pr:YAG nanoparticles for super-resolution ESA microscopy. Nonetheless, the use of high-photon energy UV UCL emission and a complex excitation scheme, which has limited applicability in biomedical and photonics fields, may prompt the exploration of alternative lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs and illumination conditions for broader applications of this technique. For instance, saturated upconversion inhibition with a depletion ratio of ⁓30% was achieved with Yb3+/Er3+-doped UCNPs excited at 795 nm and inhibited at 1140 nm with a light intensity at ∼100 kW cm−2 through ESA and interionic energy transfer, and detecting green UCL emission109. In contrast to the typical super-resolution STED laser beam intensity range of 1–100 MW cm−2, this laser beam intensity was up to three orders of magnitude smaller, making it more biologically tissue-friendly.

Fig. 4. Summary of targeted super-resolution techniques based on upconversion inhibition saturation of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs.

a Schematic of the energy level diagram of Pr3+-doped UCNPs for super-resolution ESA microscopy. Reproduced with permission from ref. 77. Copyright 2011 American Physical Society77. b Schematic of the sequence of laser pulses for super-resolution ESA microscopy imaging of Pr3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 77. Copyright 2011 American Physical Society77. c Confocal and super-resolution ESA microscopy imaging of Pr3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 77. Copyright 2011 American Physical Society77. d Schematic of the energy level diagram of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high Tm3+ doping for UCL emission excitation and inhibition through STED. Reproduced with permission from ref. 78 Copyright 2017 Springer Nature Limited78. e Schematic of the super-resolution STED microscopy imaging system based on spatially overlapped Gaussian-shaped excitation and donut-shaped depletion laser beams and lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high Tm3+ doping. Reproduced with permission from ref. 78. Copyright 2017 Springer Nature Limited78. f Confocal and super-resolution STED microscopy imaging, and corresponding intensity profiles of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high Tm3+ doping. Scale bars: 500 nm (main images) and 200 nm (insets). Reproduced with permission from ref. 78. Copyright 2017 Springer Nature Limited78. g Dual-color confocal and super-resolution STED microscopy imaging, and corresponding intensity profiles of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high Tm3+ doping. Scale bar: 1 μm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 79, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2017 Springer Nature Limited79. h Schematic of the SMED mechanism for UCL emission depletion through surface migration. Reproduced with permission from ref. 80, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature Limited80. i Schematic of the energy level diagram of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with surface quenchers for super-resolution SMED microscopy. Reproduced with permission from ref. 80, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature Limited80. j Confocal and super-resolution SMED microscopy imaging, and corresponding intensity profiles of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with surface quenchers. Reproduced with permission from ref. 80, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature Limited80

Super-resolution STED microscopy

Super-resolution STED microscopy achieved super-resolution images scanning core Yb3+/Tm3+ UCNPs with a Gaussian excitation laser beam at 980 nm and a donut depletion laser beam at 808 nm, and detecting UCL emission at 455 nm78. The process of photon upconversion was initiated with the absorption of 980 nm excitation by the Yb3+ sensitizers, followed by the transfer of this energy onto the scaffold energy levels of the Tm3+ emitters (Fig. 4d). Subsequently, UCL emission was generated from the two-photon 3H4, three-photon 1G4, or four-photon 1D2 levels of Tm3+. The high doping of 8% of Tm3+ ions in these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs allowed for reduced inter-emitter distance. CR between Tm3+ ions excited at 980 nm enabled those higher excited energy states to transfer energy to surrounding Tm3+ ions in the ground or lower excited energy states with a PA-like mechanism. This process accelerated the buildup of Tm3+ ions in an intermediate excited energy state to establish a population inversion. In the presence of population inversion between the intermediate level 3H4 and the ground level 3H6, a laser beam operating at 808 nm, corresponding to the energy gap of the electronic transition from 3H4 to 3H6, initiated STED to deplete the 3H4 level. This process subsequently suppressed UCL emission from higher excited levels. UCL emission at 455 nm from 1D2 was depleted at 808 nm through STED of the intermediate excited energy state.

A value of light intensity for saturation of inhibition of 0.19 MW cm−2 was achieved, which corresponds to about three orders of magnitude reduced light intensity compared with that of typical fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials such as nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond and fluorescent quantum dots for super-resolution STED microscopy with a value of light intensity for saturation of inhibition of 1–240 MW cm−2110–112. For super-resolution STED microscopy imaging of these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, the 808 nm laser beam was spatially modulated to generate a donut-shaped PSF that was spatially overlapped with the Gaussian-shaped PSF of the 980 nm excitation laser beam at the focal plane (Fig. 4e). The lateral resolution was of 28 nm for saturated upconversion inhibition of the intermediate excited energy state to the ground energy state through STED under the 980-nm Gaussian excitation and 808-nm donut depletion light beams with a light intensity of 0.66 MW cm−2 and 9.75 MW cm−2, respectively (Fig. 4f). Super-resolution STED microscopy images were obtained from the same sample area through continuous laser excitation and scanning, revealing remarkable photostability that persisted for several hours. Super-resolution STED microscopy can be used in different lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs for multicolor super-resolution imaging with the same laser beams. For instance, by adding Tb3+ and Eu3+ ions to the Yb3+-Tm3+ system, luminescent nanoprobes with UCL emission in complementary spectral channels can be generated, utilizing energy migration-mediated upconversion beyond the 1D2 state113. Super-resolution STED microscopy achieved two-color super-resolution images scanning core-shell Yb3+/Tm3+,Tb3+ UCNPs with a Gaussian excitation light beam at 975 nm and a donut depletion light beam at 810 nm79 (Fig. 4g). UCL emission with two wavelengths was excited at 975 nm and depleted at 810 nm through STED assisted by interionic CR. This demonstration shows promise for multi-color super-resolution STED microscopy, using multiple lanthanide ion emitters, and avoiding coordination of several light beams for excitation and depletion of specific color channels.

Compared to typical super-resolution STED microscopy that allows for real-time investigations at the nanometer scale114,115, the limited UCL emission intensity and long UCL emission lifetime of lanthanide ions of UCNPs restricted the scanning speed for super-resolution optical imaging to pixel dwell times of several milliseconds. Fast super-resolution STED microscopy achieved super-resolution images scanning core Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs with a Gaussian excitation light beam at 975 nm and a donut depletion light beam at 810 nm, and detecting UCL emission at 455 nm116. The high doping of Yb3+ ions allowed for enhanced UCL emission through clustering effect117, and accelerated kinetics of UCL emission approaching the intrinsic luminescence lifetime of the emitting excited energy states of Tm3+ ions. The lateral resolution was of 72 nm. The exposure time was decreased to 10 µs pixel−1, which corresponds to about two orders of magnitude reduced exposure time compared to that of previously demonstrated super-resolution STED microscopy using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high Tm3+ doping78,79. This demonstration shows promise for lanthanide ion-doped UCNP-enabled fast and emission streaking-free super-resolution STED microscopy with an exposure time comparable with that for super-resolution imaging using typical fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials.

The optimal excitation power for high-efficiency depletion in low-intensity super-resolution STED microscopy using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs was investigated through rate equation modeling118. This method relied on non-saturated excitation based on the dynamic CR energy transfer of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. The lateral resolution was 33 nm under a 980-nm Gaussian excitation light beam with a light power of 1 mW and a 808-nm donut depletion light beam with a light intensity of 3.4 MW cm−2. Optimizing super-resolution STED microscopy with lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs entails balancing UCL emission, depletion efficiency, and imaging quality, typically through empirical trial and error due to unknown mechanisms. These recent insights into power-dependent nonlinear responses have refined UCL excitation and depletion, enhancing efficiency, and understanding the intricate energy-transfer processes within lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs toward reducing laser beam intensity.

Super-resolution SMED microscopy

Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, with their long emission lifetimes, have facilitated super-resolution while reducing inhibition laser beam intensity compared to the use of typical counterparts78,79. Yet, improving inhibition performance necessitates nanoprobes with larger cross-sections and longer lifetimes, presenting a developmental hurdle. Moreover, prolonged UCL emission lifetimes may lead to slower imaging speeds and weaker UCL emission signals. Therefore, exploring new photophysical mechanisms to enhance UCL emission inhibition while reducing saturation intensity represents a promising avenue. Surface energy quenchers or states frequently impact the UCL emission process in lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, leading to extensive efforts to alleviate these side effects and enhance UCL emission performance86. Conversely, these surface phenomena can stimulate the exploration of innovative mechanisms for optically controlled energy dissipation. Nonetheless, actively controlling surface quenching to deactivate fluorescence has been a considerable challenge. Recently, surface migration was exploited to achieve high-efficiency UCL emission depletion of core gadolinium-doped UCNPs80 (Fig. 4h). The gadolinium sublattice established a robust energy migration network, channeling energy from luminescent centers to surface quenchers113. This enables the depletion of luminescent center energy via nonradiative dissipation at nanoparticle surfaces, facilitating low depletion saturation intensity. This process initiated with ESA to the 1G4 state of Tm3+, followed by energy pumping to the higher 1I6 state. Efficient energy transfer then occurred due to the overlap of energy levels between the 1I6 state of Tm3+ ions and the 6P7/2 state of Gd3+ ions, with energy migrating from Tm3+ ions to surrounding surface defects or quenchers adjacent to the Gd3+ ions (Fig. 4i). Super-resolution SMED microscopy achieved super-resolution images scanning Yb3+/Tm3+/Gd3+-doped UCNPs with a Gaussian excitation light beam at 975 nm and a donut inhibition light beam at 730 nm, and detecting UCL emission at 475 nm (Fig. 4j). UCL emission was depleted with efficiency over 95% and a value of light intensity for saturation of inhibition of 18.3 kW cm−2 by surface migration through Gd3+ sub-lattices. The lateral resolution was 16.8 nm for saturated upconversion inhibition under the Gaussian excitation and donut inhibition light beams with a light intensity of 98 kW cm−2 and 1.09 MW cm−2, respectively. The development of this strategy opens up avenues for a more thorough understanding and precise control over nanoparticle surface states, potentially facilitating the further advancement of high-performance luminescent probes for a wide range of low-power, diffraction-unlimited super-resolution imaging techniques and super-resolution photo-activation in applications in biology and photonics, including photo-activation and lithography.

Targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission non-saturation

Super-resolution SEE microscopy

Using luminescent nanomaterials with super-linear emission upon laser illumination enables the confinement of luminescence emission to a smaller region than the laser beam’s width, enhancing imaging resolution. This principle forms the basis for achieving 3D super-resolution on a standard confocal microscope without setup adjustments or complex image processing. However, practical realization was hindered by the lack of availability of suitable nanomaterials with high super-linear properties. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs can spontaneously enter a highly super-linear regime, eliminating the need for complex procedures or higher excitation powers. Therefore, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have been suggested as a means to demonstrate super-resolution imaging on a confocal microscope119–122, but their application was mostly limited to experimentally showcasing lateral resolution enhancement within a proof-of-principle framework.

Super-resolution SEE microscopy achieved 3D super-resolution images scanning core Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs with a Gaussian excitation light beam at 976 nm and detecting UCL emission at 455 nm on a standard confocal optical microscopy system81 (Fig. 5a). Such an emission resulted from the 1D2 → 3F4 transition of Tm3+ ions which involves up to six photons123. Typical fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials require complex conditions and high excitation light intensity to reach a high order of non-linearity124,125. On the other hand, the high doping of Tm3+ ions of UCNPs allowed for reaching highly super-linear UCL emission spontaneously and with low excitation light intensity. The intensity saturation curve for UCL emission at 455 nm of these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs showed n = 4.1 under non-saturating light excitation at 976 nm (Fig. 5b). A theoretical and computational framework was established to determine the enhancement of optical resolution in both lateral and axial directions when imaging various super-linear fluorophores under diverse excitation beams. Conventional confocal microscopy was utilized when the excitation laser beam intensity fell within the saturation region of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs’ intensity saturation curve. However, reducing the laser beam intensity to the non-saturation region revealed a highly super-linear dependence of UCL emission, enabling super-resolution microscopy with a confocal microscope in spontaneous super-resolution SEE microscopy mode. The lateral and axial resolutions were 216 nm and 542 nm, respectively, for non-saturated UCL emission under the Gaussian light beam excitation at a light intensity of 2.3 mW μm−2 (Fig. 5c). Under super-resolution SEE microscopy imaging conditions, the nanoparticles exhibited high photostability, allowing for hours of imaging without significant deterioration in UCL emission intensity or changes in super-resolution SEE microscopy resolution. Under prolonged high-power illumination, UCL emission from the nanoparticles deteriorated, prompting a change in the intensity saturation curve. To counteract this, a pre-illumination procedure was applied to the nanoparticles, leading to reduced yet stable UCL emission.

Fig. 5. Summary of targeted super-resolution techniques based on UCL emission non-saturation of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs.

a Schematic of the experimental setup based on a standard confocal optical microscopy system for super-resolution SEE microscopy using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 81, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2019 Springer Nature Limited81. b Intensity saturation curve of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high Tm3+ doping. Reproduced with permission from ref. 81, CC BY 4.0 Copyright 2019 Springer Nature Limited81. c 3D confocal and super-resolution SEE microscopy imaging, and corresponding intensity profiles of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high Tm3+ doping. Reproduced with permission from ref. 81, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2019 Springer Nature Limited81. d Schematic of the PA effect in Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 82, 2021. Springer Nature Limited82. e Model plot of the intensity saturation curve of Tm3+-doped UCNPs with PA UCL emission with a non-linearity of more than 15. Reproduced with permission from ref. 82. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature Limited82. f Confocal and PASSI nanoscopy imaging, and corresponding intensity profile of Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 82 Copyright 2021 Springer Nature Limited82. g Schematic of the PA mechanism in Yb3+/Pr3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 83. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature Limited83. h Confocal and MPA nanoscopy imaging, and corresponding intensity profiles of Yb3+/Pr3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 83. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature Limited83

In contrast to all previously reported demonstrated super-resolution techniques, super-resolution SEE microscopy using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs revealed resolution enhancement in the sub-diffraction regime by minimizing the photon budget. This unexpected trend creates opportunities for low-energy super-resolution applications. Although the resolution of super-resolution SEE microscopy using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs under NIR excitation light is equivalent to that of diffraction-limited techniques using visible excitation light, this technique has advantages such as lower scattering and absorption, photo-damage, and autofluorescence background. Super-resolution SEE microscopy using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs operates at two to three orders of magnitude lower excitation light intensity compared to that of lanthanide ion-doped UCNP-enabled super-resolution STED microscopy78,79. The achievable resolution of super-resolution SEE microscopy may be improved further using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with higher order of non-linearity and shorter excitation light wavelength. Also, lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with shorter luminescence lifetimes and higher brightness, combined with multi-focal approaches, may enable faster imaging.

PASSI nanoscopy and MPA nanoscopy

PA is a positive feedback system that leads to an extremely high order of non-linearity and efficiency42. Luminescent nanomaterials demonstrating PA behavior with highly nonlinear responses find a compelling application in single-particle super-resolution imaging. This is because the size of the imaging PSF in scanning confocal microscopy decreases inversely with the square root of the degree of nonlinearity. PA-induced non-linearity was first observed in Pr3+-doped bulk crystals, which showed a significant rise in UCL emission excited beyond a critical pump light intensity threshold90. PA-like behavior was seen in experimental designs using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs due to aggregation91 or pre-avalanche energy looping42,78,79 with a high order of non-linearity of up to 6.2 in 8% Tm3+-doped UCNPs excited at 976 nm81 and up to 3.2 in 1.5% Tm3+-doped UCNPs excited at 1064 nm for ESA instead of GSA transitions126,127. The concept of using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with PA behavior was proposed for super-resolution imaging without photobleaching of fluorophores and simplified optical systems128. Theoretical simulations were performed to model PA UCL emission of Nd3+-doped UCNPs excited at 1064 nm.

Exploiting the PA behavior of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, PASSI nanoscopy achieved super-resolution images scanning core-shell Tm3+-doped UCNPs with a Gaussian excitation light beam at 1,064 nm and detecting UCL emission at 800 nm on a standard confocal microscopy system82. In these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, a single GSA event initiated a chain reaction of ESA and CR events between lanthanide ions, resulting in the UCL emission of many upconverted photons (Fig. 5d). These lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs exhibited the defining features of PA, that are (i) a distinct excitation light intensity threshold at which a significant non-linear rise in population in the excited energy state and UCL emission were detected, (ii) an unusually long rise time, that is the time required to achieve 95% of the asymptotic value, near the PA excitation light intensity threshold, with values reaching a maximum of 608 ms, approximately 400 times the luminescence lifetime of the intermediate excited energy states, iii) ESA that was more than 10,000 times larger than GSA. Importantly, all three PA criteria were satisfied at room temperature for these Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Tm3+ ions in these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs absorbed excitation photons at 1,064 nm by non-resonant GSA and resonant ESA, followed by CR and PA UCL emission at 800 nm with an order of non-linearity of more than 15 (Fig. 5e). The resolution in PASSI nanoscopy for a given excitation light intensity was determined by the slope of the intensity saturation curve of these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. The lateral resolution was of less than 70 nm for non-saturated UCL emission under the Gaussian light beam excitation at a light intensity of 7 kW cm−2 (Fig. 5f). The intrinsic long rise times of more than half a second required to build up the PA effect with these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs restricted scanning rates. As a result, pixel dwell times of tens to hundreds of milliseconds were required. This limitation may be overcome using multi-point excitation with the potential for scan rates of ⁓4 s or less per frame. These nanoparticles exhibited no measurable photobleaching or hysteresis, indicating an absence of detectable contributions from excitation-induced thermal avalanching129.

Recently, a strategy was proposed for propagating the PA effect across different lanthanide ions and core-shell nanostructures of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. This approach allowed for realizing high optical nonlinearities from various lanthanide emitters. The key was doping two types of lanthanide ions: PA ions and reservoir ions. PA ions initiated the PA effect, supported by reservoir ions130. Yb3+ ions were chosen as reservoir ions for their versatility as sensitizers, characterized by a large absorption cross-section and a simple energy-level structure131. This selection helped avoid detrimental CR processes while enabling constructive interaction with PA ions. Additionally, the sublattice of Yb3+ ions contributed to forming a migration network for energy propagation132, activating energy loops that also contributed to the PA effect. Pr3+ ions were selected to trigger the PA effect in Yb3+ reservoir ions due to their demonstrated PA capability in bulk materials90,133–136 and fast UCL emission rate, along with large absorption and UCL emission cross-sections42. These Yb3+/Pr3+-doped UCNPs were excited at 852 nm, and UCL emission generated through the PA effect was detected from Pr3+ ions83 (Fig. 5g). A CW laser beam at 852 nm, with photon energy matching the ESA in Pr3+ ions via the transition 1G4 → 3P1, was used for excitation of Yb3+/Pr3+-doped UCNPs. This wavelength choice resulted in weak non-resonant GSA in both Yb3+ and Pr3+ ions. Through an efficient energy transfer process, Pr3+ ions returned to the 1G4 state while simultaneously promoting Yb3+ ions from the ground state to the excited state. Via an additional energy transfer mechanism, additional Pr3+ ions were populated to the 1G4 state, effectively doubling the population of 1G4. Subsequently, the strong resonant ESA pumped the Pr3+ ions from the 1G4 to the 3P1 state, initiating the next looping cycle. This ESA-driven energy transfer formed a positive feedback loop, continuously repeated to facilitate the PA effect. Consequently, it amplified the population of emitting levels, such as the 3P1 and 3P0 states, generating UCL emission. For instance, 484-nm UCL emission originated from the transition 3P0 → 3H4 and the slope of the intensity saturation curve was up to 26 with a low threshold of about 60 kW cm−2.

Super-resolution MPA nanoscopy imaging of Yb3+/Pr3+-doped UCNPs was performed on a standard confocal microscopy system under excitation from an 852 nm CW laser beam, and detecting 484 nm UCL emission (Fig. 5h). The lateral resolution was of 62 nm for non-saturated UCL emission under the Gaussian light beam excitation at a light intensity of 76 kW cm−2, in comparison to a lateral resolution of 289 nm for saturated UCL emission, with the lateral resolution enhanced by approximately fivefold. This demonstration provides a facile route to achieve UCL emissions with an extremely high order of non-linearity and using different lanthanide ion emitters for low-energy super-resolution applications. In contrast to other targeted super-resolution techniques, such as those utilizing lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs through the ESA mechanism with three pulsed or CW laser beams77,109, as well as through the STED mechanism with two CW laser beams78,79, this technique relied solely on a single NIR CW excitation beam of reduced intensity, eliminating the need for intricate data reconstruction. Also, these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs demonstrated no photobleaching during hour-long laser scanning imaging, underscoring their remarkable emission efficiency and photostability (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the working principles and benchmark parameters of typical targeted super-resolution techniques (colored in gray), lanthanide ion-doped UCNP-enabled targeted super-resolution techniques based on upconversion emission saturation and upconversion inhibition saturation (colored in blue), and upconversion emission non-saturation (colored in orange)

Low-energy super-resolution applications using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs

Super-resolution bio-imaging and tracking

Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have proven useful in targeted super-resolution techniques for bio-imaging and tracking applications with low energy use137–139. This advantage stems from the photon upconversion process of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, which requires excitation with low-intensity light and low laser energy density for super-resolution. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs were used as luminescent probes to study the morphology and physiology of biological samples, such as subcellular structures and dynamics140–143. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs outperform typical fluorophores and luminescent nanomaterials used as luminescent probes in various ways. They have a longer luminescence lifetime, higher photostability, and a narrow emission spectrum, which minimizes background noise and increases signal-to-noise ratio. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs allow for surface functionalization for improved stability, biocompatibility, and targeting abilities in bio-imaging and tracking applications144–146. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs can be excited by low-photon energy NIR light, which can penetrate deeper into biological tissues than visible or UV light, making them excellent for in vivo imaging147. Single-photon excitation (SPE) techniques require high light power in the visible region to produce high resolution since the tissue attenuates more power for shorter light wavelengths. MPE techniques in the NIR range are frequently used, but the extremely small absorption cross-sections of multi-photon probes compel higher light power. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs require minimal light power into the deep tissue, use low-photon energy NIR excitation light wavelength, and have high absorption cross-section. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs have enabled to drastically reduce the light intensity needed for saturation of inhibition in targeted super-resolution techniques. Furthermore, when lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs serve as UCL emission imaging probes, they exhibit no background autofluorescence. This is because NIR light does not activate endogenous or exogenous fluorophores in organisms, resulting in a high signal-to-noise ratio. The high photo-stability of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs allows for their use in both in vitro and in vivo imaging. Their composition of non-toxic elements holds promise for biomedical applications. Moreover, their large, adaptable surface enables straightforward modification for conjugation with hydrophilic ligands, biomolecules, and therapeutic agents, making them well-suited for biological applications.

Super-resolution STED microscopy imaging of the cytoskeleton of HeLa cancer cells was performed with a lateral resolution of 82 nm using Yb3+/Tm3+ UCNPs79 (Fig. 6a). Deep-tissue NIRES nanoscopy imaging was performed with a lateral resolution of 38 nm using Yb3+/Tm3+ UCNPs73 (Fig. 6b). These lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs were placed behind mouse liver tissue with a thickness of 93 μm and diffused throughout the tissue at various depths. NIRES nanoscopy using NIR light for both excitation and emission enables higher penetration depth, and lower autofluorescence background and phototoxicity in biological samples compared to techniques using visible light. While only 11.3% of UCL emission at 455 nm from these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs was left in confocal microscopy imaging, 38.7% of UCL emission at 800 nm was detectable in both confocal and NIRES nanoscopy imaging. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs were resolved from clusters in deep tissue with a spacing of 72 nm using the NIR-in and NIR-out design. 3D NIRB nanoscopy mapping of a cancer spheroid made of human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells was performed with Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs74 (Fig. 6c). These lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs were incubated with the cancer spheroid to enable penetration. The lateral resolution was of 98 nm with a penetration depth of 56 µm. This technique shows promise for studying physiological responses and drug delivery processes by tracking cell uptake and transport of nanoscale cargo in cancer spheroids. Super-resolution SMED microscopy imaging of the cytoskeleton actin filaments of HeLa cancer cells was performed with a lateral resolution of 108 nm using Yb3+/Tm3+ UCNPs80 (Fig. 6d). Deep-tissue LSIM and NSIM imaging was performed with Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs76 (Fig. 6e). These lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs were placed in nanochannel structures and coated with mouse liver tissue with a thickness of 52 μm. When compared to diffraction-limited wide-field microscopy imaging, super-resolution LSIM and NSIM imaging allowed for improved resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, and an imaging rate of 1 Hz was obtained.

Fig. 6. Summary of low-energy super-resolution bio-imaging and tracking applications using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs.

a Confocal and super-resolution STED microscopy imaging of the cytoskeleton of HeLa cancer cells using Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Scale bar: 2 μm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 79, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2017 Springer Nature Limited79. b Schematic of a mouse liver tissue slice and deep-tissue confocal and NIRES nanoscopy imaging using Yb3+/Tm3+ UCNPs. Scale bar: 500 nm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 73, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature Limited73. c 3D NIRB nanoscopy imaging of deep cancer spheroid using Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 74. Copyright 2020 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.74. d Confocal and super-resolution SMED microscopy imaging of the cytoskeleton actin filaments of HeLa cancer cells using Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Scale bar: 800 nm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 80, CC BY 4.0. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature Limited80. e Wide-field and super-resolution LSIM imaging of deep mouse liver tissue using Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Scale bar: 1 μm. Reproduced with permission from ref. 76. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society76. f 3D confocal and super-resolution SEE microscopy imaging of neuronal cells using Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 81, CC BY 4.0, Copyright 2019 Springer Nature Limited81. g Confocal and MPA nanoscopy imaging of actin protein filaments of HeLa cancer cells using Yb3+/Pr3+-doped UCNPs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 83. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature Limited83

Performing super-resolution bio-imaging and tracking in 3D is desirable, but instrument complexity and large photon budgets limited such an implementation. Only a few targeted super-resolution techniques offered 3D isotropic resolution of less than 30 nm148–152. 3D super-resolution SEE microscopy imaging of neuronal cells was performed with a lateral and axial resolutions of 210 nm and 450 nm, respectively, using Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs on a standard confocal microscopy system81 (Fig. 6f). Continuous super-resolution imaging was performed for over 5 hours with a decrease of UCL emission intensity of less than 1% per hour with potential for super-resolution long-term observations and dynamics studies of biological samples. MPA nanoscopy imaging of sub-cellular actin protein filaments of HeLa cancer cells was performed with a lateral resolution of 62 nm using Yb3+/Pr3+-doped UCNPs on a standard confocal microscopy system83 (Fig. 6g). These lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs enabled imaging speed with an exposure time of 100 μs pixel−1, that is approximately 500 times higher than that of the parallel work82. Long-term imaging revealed no photobleaching, indicating high UCL emission efficiency and photostability.

Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs hold potential for super-resolution biophotonics due to their superior photostability and precise detection capabilities153. However, concerns about their toxicity arise from their small size, facilitating deep tissue penetration and accumulation in organs, alongside elevated surface reactivity impacting biocompatibility154–157. Despite widespread use in biomedicine and generally low toxicity observed, understanding the health impact of engineered nanomaterials is still incomplete, requiring updated regulations158. The complexity of nanoparticles complicates toxicity prediction, requiring consideration of various factors like chemical composition, surface properties, and environmental conditions159–162. Comprehensive studies on nanoparticle-cell interactions are crucial for accurate toxicity assessment, with further research needed to understand long-term effects and clearance mechanisms for lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs163.

Super-resolution encoding

Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with tunable compositions and structures can be used to encode multiple physical dimensions at the single-nanoparticle level, which can provide low-energy, high-capacity, and high-throughput technologies164–166. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs are beneficial for use in security and anti-counterfeiting applications because the unique spectral signature of each nanoparticle can be used to encode and detect encrypted information. Luminescence lifetime encoding was achieved using Yb3+/Tm3+-doped UCNPs by tuning Tm3+ ion doping to modulate interionic energy transfer rates and UCL emission lifetimes167. UCL emission and luminescence lifetime encoding were achieved using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs by incorporating energy distributors168. Binary temporal upconversion coding was achieved by doping lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with transition metal Mn2+ ions with a long luminescence lifetime of 39 ms and lanthanide ions with a relatively short luminescence lifetime, such as Tm3+ ions with a luminescence lifetime of 0.5 ms169,170. UCL emission and luminescence lifetime of Mn2+ ions in Mn2+-doped UCNPs were tuned through crystal-site engineering by alkaline-earth metals doping171. Luminescence lifetime and UCL emission wavelength encoding were achieved using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs by designing multi-shell structures combined with the energy relay technique172. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs exhibited power-independent orthogonal UCL emission due to the effect of an absorption filtration shell173. Lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs exhibited intrinsic time-dependent tunability of the UCL emission wavelength depending on the decay time of the lanthanide ion emitters, using fixed doping and excitation174. Luminescence lifetime and UCL emission intensity encoding was achieved using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs by modulating the sensitizer gradient doping structure175. Frequency encoding was achieved using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs by modulating the phase angle of UCL emission under harmonic-wave excitation176.

High spatial-temporal resolution optical multiplexing was used to achieve super-resolution encoding in lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. Excitation wavelength, emission wavelength, and luminescence lifetime profile encoding were achieved using Tm3+-doped and Er3+-doped UCNPs177. Time-domain optical fingerprints were generated by controlling the populations of the excited energy states in Tm3+ and Er3+ ions excited at 976 nm or 808 nm. Time-domain confocal microscopy, wide-field microscopy, and super-resolution SIM images were acquired to determine the luminescence lifetime profile of these lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs. The lateral resolution was 184.8 nm under 808-nm pulsed CW light excitation at a light intensity of 5.46 kW cm−2. These lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with high-dimensional optical fingerprints show promise for low-energy super-resolution applications as individually preselectable nanotags. The machine learning (ML) algorithm known as ‘deep learning’ is a helpful tool for rapidly and precisely decoding nanoscale objects178,179. Deep learning was used to improve the imaging resolution of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with multimodal UCL emissions180, decode visible information181, and classify the high-dimensional optical fingerprints of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs based on their luminescence lifetime profiles182.

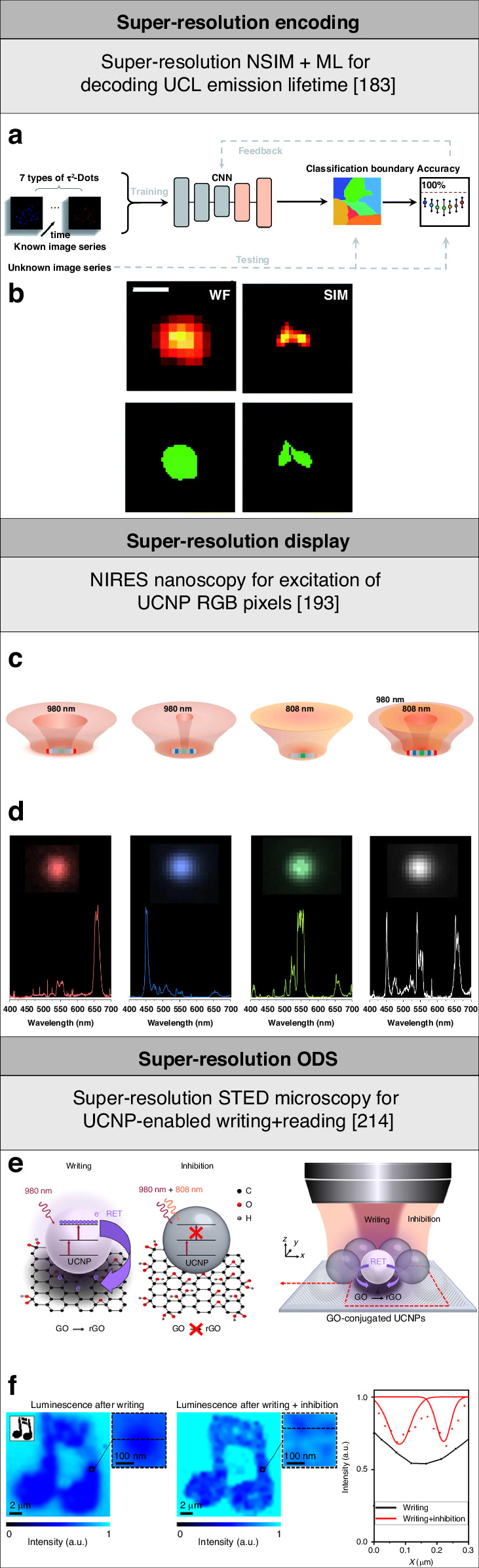

Super-resolution decoding of Nd3+, Yb3+, and Er3+-doped UCNPs with high-dimensional optical fingerprints was achieved using deep learning and time-domain super-resolution LSIM imaging183 (Fig. 7a). A deep learning algorithm based on a convolutional neural network architecture used UCL emission lifetime curves of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs for training to extract distinctive features. After optimization, different types of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs were randomly selected for testing classification accuracy. The mean classification accuracy for the UCL emission lifetime profiles of these nanoparticles surpassed 90%. Following this, super-resolved decoding was achieved through time-resolved super-resolution LSIM microscopy with deep learning (Fig. 7b). The lateral resolution was 185 nm under 808-nm sinusoidal light pattern excitation with a light intensity of 3.23 kW cm−2. The use of super-resolution NSIM76 offers the potential for improving decoding resolution compared to the use of super-resolution LSIM. Also, enhancing lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs with shorter lifetimes and brighter emissions could expedite imaging. Further performance enhancements could be achieved by integrating additional features of lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs, such as UCL emission intensity, spectrum, or excitation laser wavelength, into the decoding algorithm.

Fig. 7. Summary of low-energy super-resolution encoding, display and data storage applications using lanthanide ion-doped UCNPs.