Abstract

Objectives

Shared Decision Making (SDM) has potential to support Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) decision-making when patients are offered a menu of centre- and home-based options. This study sought to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a three-component PR SDM intervention for individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and PR healthcare professionals.

Methods

Participants were recruited from Dec 2021–Sep 2022. Healthcare professionals attended decision coaching training and used the consultation prompt during consultations. Individuals received the Patient Decision Aid (PtDA) at PR referral. Outcomes included recruitment capability, data completeness, intervention fidelity, and acceptability. Questionnaires assessed patient activation and decisional conflict pre and post-PR. Consultations were assessed using Observer OPTION-5. Optional interviews/focus groups were conducted.

Results

13% of individuals [n = 31, 32% female, mean (SD) age 71.19 (7.50), median (IQR) MRC dyspnoea 3.50 (1.75)] and 100 % of healthcare professionals (n = 9, 78% female) were recruited. 28 (90.32%) of individuals completed all questionnaires. SDM was present in all consultations [standardised scores were mean (SD) = 36.97 (21.40)]. Six healthcare professionals and five individuals were interviewed. All felt consultations using the PtDA minimised healthcare professionals’ bias of centre-based PR, increased individuals’ self-awareness of their health, prompted consideration of how to improve it, and increased involvement in decision-making.

Discussion

Results indicate the study processes and SDM intervention is feasible and acceptable and can be delivered with fidelity when integrated into the PR pathway.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary rehabilitation, shared decision making, patient decision aid, decision coaching

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a chronic multisystem condition characterised by debilitating functional and psychological symptoms. 1 Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) is highly recommended for people living with COPD both with stable symptomology and post exacerbation. 2 The intervention involves personalised and progressive exercise training and education to help people effectively self-manage their COPD. Traditionally, PR has been delivered as a centre-based programme. In recent years, home-based models of PR have been developed, tested and adopted to provide a menu of options to enable people to choose the option which is right for them. These alternative models have gained considerable interest since the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic as they enabled continued access to PR particularly when traditional centre-based models were suspended.

At our PR site, the home-based options include a standardised COPD self-management manual (Self-management Programme of Activity, Coping and Education; ‘SPACE for COPD’). This 4-stage manual has shown to improve individuals’ COPD symptoms and exercise tolerance above usual care. When compared to traditional PR, SPACE for COPD has proved non-inferior for improvements in quality of life.3,4 Another option is a comparable programme delivered online. This programme has shown potential for increasing disease knowledge and PR completion for a subset of digitally literate individuals post hospitalisation. 5 Despite the increased interest in home-based PR models, the national COPD audit continues to report disproportionate attendance to the traditional model compared to home-based options and overall uptake of PR below target 6 attributable to organisational, perceptual, and demographic barriers. 7 Our research investigating the views and experiences of healthcare professionals who refer to PR and people living with COPD found similar barriers to PR, but also identified an interest in Shared Decision Making (SDM) via tools to promote meaningful discussions about PR between people with COPD and PR healthcare professionals [e.g., a Patient Decision Aid (PtDA)]. 8

PtDAs provide evidence-based information about a health condition and the available treatment options. They guide a person through the decision-making process by prompting them to consider what each option would mean for their life, 9 and can be offered before, during or after consultations with health professionals. 10 The consultation offers the opportunity for individuals and healthcare professionals to share their knowledge about the options, help individuals to consider their preferences by reasoning between the options, and discuss ways to implement the personalised choice. 11 The integration of PtDAs into healthcare pathways has resulted in greater adoption of SDM for treatment decisions and consequently in people feeling more knowledgeable about their health condition and the treatment options, and feeling more sure and more prepared about which option is right for them. 10 Furthermore, in a PR setting, the addition of a PtDA to support individuals’ decision-making about PR continuation has shown promise for increasing adherence rates. 12

Prior to this study, there were no interventions to facilitate SDM about the menu of PR options between people with COPD and their PR healthcare professional. 13 From our research,8,13–15 and using a robust and theoretically-driven approach, involving pilot testing with people living with COPD and PR healthcare professionals, we developed a three-component PR SDM intervention comprising of a PtDA, decision coaching training for PR healthcare professionals, and a consultation prompt. This study aimed to explore the feasibility and acceptability of our PR SDM intervention for individuals with COPD and their PR healthcare professional. A preliminary measure of intervention effect was also evaluated. The manuscript was written in accordance with the Standards for UNiversal reporting of patient Decision Aid Evaluation studies 16 and the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ). 17

Methods

Study design

A one-arm study evaluated the feasibility, acceptability and fidelity of the PR SDM intervention.

Setting

This research was conducted within a university teaching hospital in the Midlands, United Kingdom. Ethical approval was granted by South Leicester Research Ethics Committee (21/EM/0084). The study was registered on Clinical Trials.gov (NCT04990180).

Participants

Eligible individuals had a confirmed diagnosis of COPD (GOLD criteria) 1 and had been referred to PR by their General Practitioner, Consultant Physician or other healthcare professional.

Eligible healthcare professionals provided PR at the host site and expressed interest in delivering the intervention.

The PR SDM intervention

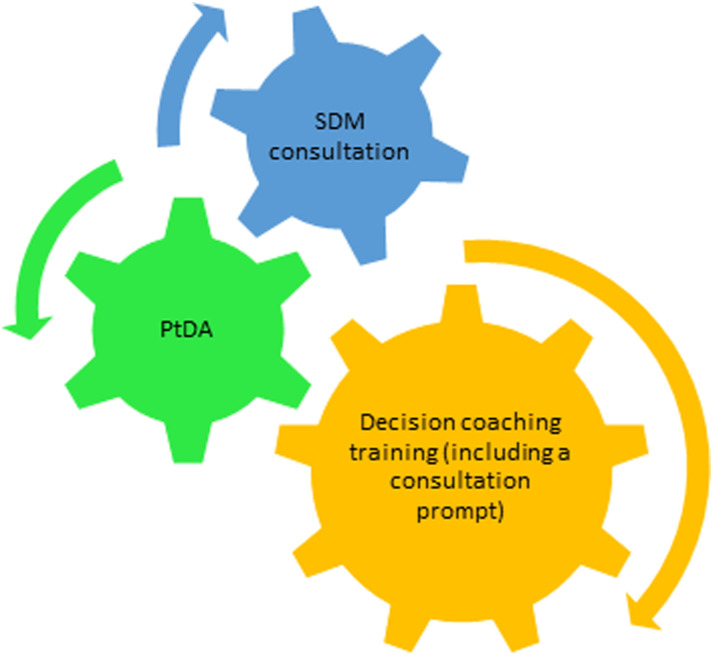

The three-component intervention included (Figure 1): decision coaching training for PR healthcare professionals, a PtDA, and a consultation prompt which was individually developed during the decision coaching training. Theoretical underpinnings, development stages and complete components are detailed elsewhere. 14

Figure 1.

The three components of the pulmonary rehabilitation shared decision making intervention, PtDA: patient decision aid.

The PtDA was provided to individuals living with COPD following their referral to PR to engage with prior to and during their SDM consultation with a PR healthcare professional. It introduced the four options available to individuals referred to the PR service: continuation of routine COPD care without PR, centre-based PR conducted in-person at a dedicated centre, home-PR telephone conducted at the individuals’ home using a manualised programme (i.e. SPACE for COPD manual), or home-PR online conducted at the individuals’ home using an online programme (i.e. online SPACE for COPD; (see Table 1 and supplemental materials).

Table 1.

Components of the options (brief version, full version provided in the supplemental materials).

| Centre PR | Home PR-telephone | Home PR-online | Routine COPD care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is the option? | Information, monitoring, and exercises given by PR professionals face-to-face+routine COPD care. | Information, monitoring, and exercises given by PR professionals over the phone+routine COPD care. | Information, monitoring, and exercises given by PR professionals online and over the phone+routine COPD care. | A yearly check-up and visits to manage COPD symptoms, flare ups, and wellbeing. |

| How long does it last for? | 6 weeks, with 2 × 2-h sessions a week and daily exercise. | 6 weeks, with daily exercise. | 6 weeks, with daily exercise. | 30 min for yearly check-up; usual consultation time per visit. |

| How is it delivered? | In groups of other people with breathing difficulties. | A self-guiding booklet and telephone support from PR professionals. | A self-guiding website and online support from the PR team. | 1-1 consultations. |

The consultation was guided by the consultation prompt. Once a decision had been made, the individual’s choice was implemented.

Objectives and outcomes

The primary objective was to test the feasibility of integrating the PR SDM intervention into practice via the adopted research methods. The secondary objective was to preliminary test the efficacy of the intervention on the quality of the decision-making process, the quality of the decision made and downstream decision outcomes (e.g., PR adherence). An exploratory objective was to measure the acceptability, adoption, and appropriateness of the intervention.

Quantitative outcomes

Primary outcome

• Feasibility of the intervention and study processes which included: feasibility of recruitment of proposed sample to time and target (i.e., 30 individuals with COPD within 9 months), feasibility of data collection, outcome measure data completeness, and intervention fidelity using the Observer OPTION 5 Scale. 18

Secondary outcomes

• Decisional conflict assessed using the 16-item Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS). 19

• Individuals’ activation assessed using the 13-item Patient Activation Measure (PAM). 20 Permission to use this licensed measure was granted prior to use.

• SDM intervention uptake (i.e., receipt of PtDA, SDM intervention consultation).

• PR programme selection (i.e., routine COPD care, centre-based PR, home-PR online, or home-PR telephone).

• Healthcare professional satisfaction with decision coaching training measured using an anonymous study-specific questionnaire developed by the study’s steering group to assess perceived usefulness of the training content, knowledge and confidence, intention to use SDM techniques and the PtDA during consultations, and suggestions for future training.

• PR uptake and adherence compared to national audit and local site data.

Decisional conflict and patient activation were measured at baseline and following completion (or drop out) of PR.

Qualitative outcomes

Secondary outcome

• Individuals’ and PR healthcare professional attitudes and experience of the PR SDM intervention.

Data collection

Individuals living with COPD

Study visits 1–3 were essential data collection points which involved informed consent procedures, baseline data collection, intervention delivery, and post-intervention data collection (see supplemental materials). The first visit was additional to routine care. Visits 2 (the SDM consultation) and visits 3 (the post-intervention data collection) integrated into the PR assessment and discharge visits.

Visit 4 was additional to routine care. It was an optional semi-structured focus group conducted face to face at the hospital and led by co-author GD (a fellow female PhD student) with qualitative research experience. GD had no experience of the decision coaching training or the SDM intervention. ACB took field notes. The focus group was led by an indicative topic guide (see supplemental materials). It was audio recorded, transcribed in full, and anonymised.

Following the first focus group ACB and GD met to discuss the richness and depth of the data collected (i.e. data adequacy). An additional focus group was conducted to capture additional views. The first focus group was held on 14th September 2022 (59 min) and the second was on 12th October 2022 (46 min).

PR healthcare professionals

PR healthcare professional study visits are provided in the supplemental materials. Visit 1 was the decision coaching training. The healthcare professionals were required to audio record the SDM consultations for the intervention fidelity assessment. Visit 2 was an optional, semi-structured one-to-one interview conducted in-person or through teleconferencing facilities by ACB or GD, and led by an indicative topic guide (see supplemental materials). Field notes were taken. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed in full, and anonymised.

Following the first three interviews, ACB and GD met to discuss data adequacy. They agreed data collected was comparable and there was no evidence of bias in methods. Interviews were conducted between August and September 2022 and lasted between 5 and 31 min.

Analysis

Sample size

The proposed sample size was 30 for individuals with COPD. This is considered sufficient for feasibility studies 21 and can estimate the sample size needed for a full scale randomised controlled trial.

A tentative sample size of 15 (10 individuals with COPD and 5 PR healthcare professionals) was proposed for the qualitative analysis. This aligns with expert opinion on a minimum data set for qualitative research 22 and allows for consideration of contextual factors which may impact data adequacy. 23

Data preparation

Quantitative data was inputted into IBM SPSS (V26). Qualitative data was uploaded into QSR International NVivo (V12).

Data analysis

Quantitative outcome analysis

Primary outcome analysis

Recruitment capability (i.e., participation rate) and data collection/outcome measures (i.e., data completeness) is presented as number and proportions (n, %).

Intervention fidelity, assessed via audio recordings of the SDM consultations were coded by ACB and SJS. Descriptive statistics compared the mean scores between items. Correlation analysis explored the relationship between the length of recordings and the overall scores. Interrater reliability, intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated for individual items and overall scores. Mean intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated using a multiple raters, consistency, two-way mixed effects model. Values <0.5 indicated poor reliability, 0.5–0.75 moderate reliability, 0.75–0.9 good reliability, and >0.9 excellent reliability. 24 Values >0.6 indicate acceptable interrater reliability. 18

Secondary outcome analysis

Data from the PR healthcare professionals’ satisfaction questionnaires was analysed descriptively and presented graphically or as written text. Intervention attendance, PR uptake, programme selection, and PR adherence are reported as number and proportions (n, %). Adherence was described as at least 75% of healthcare professional contacts (i.e. 8/12 centre-based sessions for centre-based PR 3/4 telephone appointments for home-based PR, and 3/4 telephone appointments for home-based PR online) and is presented as number and proportions (n, %).

For standardised questionnaires (i.e., the DCS, PAM), standardised scores were calculated pre- and post-intervention delivery. Mean and standard deviation are reported when data is normally distributed; median and interquartile ranges are reported where data is non-normally distributed.

Qualitative outcome analysis

Role of researcher and reflexivity

Qualitative methods were informed by a constructivist epistemological approach meaning interpretation could explore the meaning and meaninglessness of data. 25 An experiential orientation was adopted to focus upon participants’ unique experiences rather than social constructs. 26

Prior to, during, and following the qualitative research, a reflective log was used to capture the researchers’ experiences, opinions, thoughts, and feelings. 27

Secondary outcome analysis

Thematic Analysis, specifically the codebook approach Template analysis 28 was used to analyse the qualitative data. The 6-step process involved data familiarisation, preliminary coding, organisation of codes into initial themes, defining an initial coding template organised by the initial themes, applying and iteratively refining the coding template, and finalising then applying the coding template to the full dataset. Inductive, semantic and latent coding was adopted. The coding template along with selected quotes, were provided to GD for independent coding and support in developing themes. These, and illustrative quotes, were shared with co-authors to discuss and finalise the titles and content of the generated themes.

Results

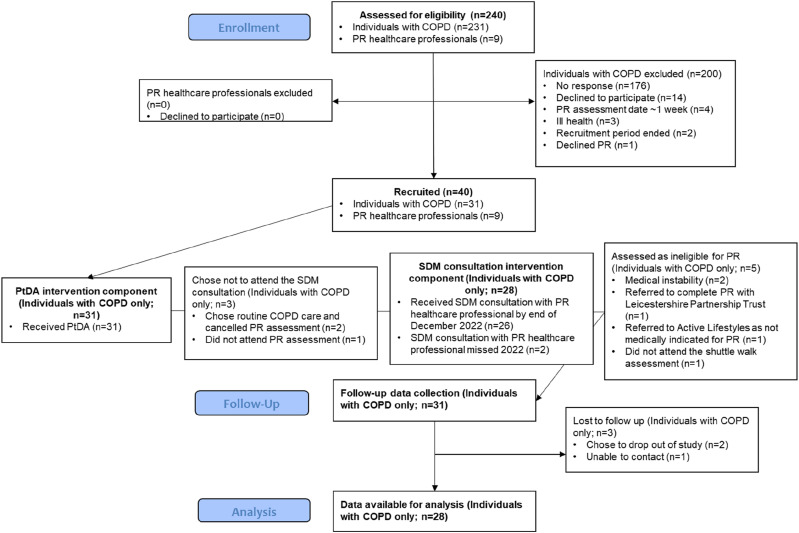

Data were collected between February 2022 and December 2022. Participant flow is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow of study participants.

Demographics

Demographics of individuals with COPD are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant (individuals with COPD) demographics.

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n = 31 | ||||

| Male | 19 (61.29%) | |||

| Female | 12 (38.71%) | |||

| Age (years), n = 31 | 71.19 (7.50) | 53.00–84.00 | ||

| Age when leaving full time education (years), n = 31 | 16.58 (3.23) | 14.00–27.00 | ||

| COPD severity (GOLD stage), n = 10 | ||||

| GOLD stage 1 | 1 (10.00%) | |||

| GOLD stage 2 | 3 (30.00%) | |||

| GOLD stage 3 | 6 (60.00%) | |||

| GOLD stage 4 | 0 (0.00%) | |||

| MRC dyspnoea scale, n = 21 | 3.50 (1.75) | 1.00-5.00 | ||

| Number of comorbidities, n = 31 | 2.32 (2.00) | 0.00-7.00 | ||

| Previously attended PR, n = 31 | ||||

| Attended | 5 (16.13%) | |||

| Referred but did not attend | 7 (22.58%) | |||

| No previous attendance | 19 (61.29%) | |||

FEV1 % predicted: forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration divided by the average FEV1% in the population for any person of similar age, sex, and body composition.

MRC: medical research council.

Nine PR healthcare professionals were trained to deliver the intervention (male, n = 2; female, n = 7). More demographic details were collected from PR healthcare professionals who participated in the semi-structured interviews (see below).

Quantitative results

Primary outcomes results

Feasibility of recruitment (recruitment to time and target)

31 (13.42% of those screened) individuals with COPD, and 9 (100.00% of those screened) PR healthcare professionals were recruited to the study between January 2022 and September 2022 (Figure 2).

Feasibility of data collection/outcome measures (data completeness)

The Decisional Conflict Scale and Patient Activation Measure were completed by 90.32% of individuals with COPD post-intervention (Table 3).

Table 3.

Completeness of primary and secondary outcome measures compared to the intended number of datasets.

| Outcome measure (n = possible number of datasets) | Pre-intervention data completeness N (%) | Post-intervention data completeness N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| Intervention fidelity (n = 31) | N/A | 19 (61.29%) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Healthcare professional satisfaction with training (n = 9) | 8 (88.89%) | N/A |

| Patient activation measure (n = 31) | 30 (96.77%) | 28 (90.32%) |

| Decisional conflict scale (n = 31) | 31 (100.00%) | 28 (90.32%) |

| Intervention uptake (n = 31) | N/A | |

| Received PtDA | 31 (100.00%) | |

| Received SDM consultation with facilitator | 26 (83.87%) | |

| Uptake to PR (n = 31) | N/A | |

| Attended a PR assessment | 28 (90.32%) | |

| Unsuitable for PR following assessment | 3 (9.68%) | |

| Selection (n = 25) | ||

| Routine COPD care | 2 (8.00%) | 2 (8.00%) |

| Centre-based PR | 19 (76.00%) | 18 (72.00%) |

| Home- based PR online (i.e., online SPACE for COPD) | 1 (4.00%) | 1 (4.00%) |

| Home-based PR telephone (i.e., SPACE for COPD) | 3 (12.00%) | 4 (16.00%) |

| Completion of PR (n = 23) | N/A | |

| Completed a PR programme | 15 (65.22%) | |

| • Centre-based PR | 13 (56.52%) | |

| • Home- based PR online (i.e., online SPACE for COPD) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| • Home-based PR telephone (i.e., SPACE for COPD) | 2 (8.70%) | |

| Did not complete a PR programme | 8 (34.78%) | |

Intervention fidelity

Of the 28 individuals who attended their PR assessment, 26 (92.86%) received the SDM consultation. Of these, 19 (73.08%) SDM consultations were audio recorded, the remainder were unintentionally missed. The intraclass correlation coefficient for overall score was 0.89 (95% CI 73.00–95.50) indicating good interrater reliability.18,24 Whilst intraclass correlation coefficients for the individual items ranged from moderate to good, the confidence intervals had wide ranges (see supplemental materials).

Shared Decision Making consultations ranged from 1.00 to 21.00 min [mean (SD) = 5.80 (5.55)]. SDM elements were present in all. The one consultation lasting 1.00 min contained all elements apart from item 2 (i.e., it scored 0 for item 2). This participant chose centre-based PR.

Standardised overall scores ranged from 10.00 (the consultation lasting 1.00 min) to 82.50 (the consultation lasting 21.00 min; [mean (SD) = 36.97 (21.40)]. Standardised scores for items 1, 2, and 5 each had a minimum score of 0, indicating that they were conducted less comprehensively (Table 4). There was a significant large positive correlation between time and standardised overall scores (r = 0.90, p < .05).

Table 4.

Standardised scores for the observer OPTION-5 scale items (n = 19).

| Observer OPTION-5 item | Mean (SD) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1: alternate options | 1.37 (0.70) | 0.00 | 2.50 |

| Item 2: support deliberation | 0.89 (0.98) | 0.00 | 3.50 |

| Item 3: information about options | 1.84 (1.00) | 0.50 | 4.00 |

| Item 4: eliciting preferences | 1.92 (1.00) | 0.50 | 4.00 |

| Item 5: integrating preferences | 1.30 (0.99) | 0.00 | 4.00 |

Scores range from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating more comprehensive adherence to an item.

Secondary outcome results

Decisional conflict

Pre-to post-intervention delivery showed scores decreased from those indicating decision delay or feeling unsure about implementation to feeling sure about decision implementation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Standardised scores for the decisional conflict scale pre and post intervention delivery.

| Outcome | Pre-PR (n = 31) | Post-PR (n = 28) | Mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Decisional conflict scale total score | 50.00 (25.00) | 25.00 (16.80) | −29.41 (−37.31 to −21.51) |

Decision conflict scale scores range from 0 to 100 with 0 indicating no decisional conflict and 100 indicating extremely high decisional conflict. Scores <25 are associated with implementing decisions, scores >37.5 are associated with decision delay or feeling unsure about implementation.

Patient activation

Post-intervention delivery, there were no clear trends for changes in PAM scores (Table 6). The pre- to post-intervention total score did not indicate a clinically significant improvement.

Table 6.

Proportion of individuals allocated to each level of the patient activation measure pre and post intervention delivery.

| Outcome | Pre-PR (n = 30) | Post-PR (n = 28) | Pre-PR (n = 30) | Post-PR (n = 28) | Mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Mean (95%CI) | |

| Patient activation measure | |||||

| Level 1 | 5 (16.67%) | 2 (7.14%) | |||

| Level 2 | 10 (33.33%) | 14 (50.00%) | |||

| Level 3 | 10 (33.3%) | 8 (28.57%) | |||

| Level 4 | 5 (16.67%) | 4 (14.28%) | |||

| Total score | 54.40 (14.50) | 53.20 (7.10) | 0.96 (−5.33 to 7.25) | ||

| Level | 2.50 (1.00) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.04 (−0.31 to 0.38) | ||

Patient activation measure total scores range from 0 to 100. These correlate with one of four levels of activation. Level 1 indicates an individual is disengaged and overwhelmed, level 2 indicates an individual is becoming aware but still struggling, level 3 indicates an individual is taking action and gaining control, and level 4 indicates an individual is maintaining behaviours and pushing further. An improvement of four points in the total score indicates clinically significant difference.

Intervention attendance and attrition

Of the 31 participants recruited, 31 (100.00%) received the PtDA. Of those who attended their PR assessment (n = 28), 26 (92.86%) received the SDM consultation. 2 (7.14%) consultations were not conducted due to PR healthcare professional error.

PR healthcare professionals’ satisfaction with decision coaching training

Satisfaction of the session was high. All PR healthcare professionals reported their understanding of SDM and PtDAs had increased and most reported their understanding and confidence in using SDM skills and the PtDA had also increased with mean (SD) 97.50% reporting intention to use these in the SDM consultations (see supplemental materials).

Qualitative results

Secondary outcome results

Attitudes/experiences of the PR SDM intervention

Demographics

18 individuals with COPD and 9 PR healthcare professional participants were approached. Of those, 5 (27.78%) individuals attended the focus groups, and 6 (66.67%) PR healthcare professionals attended the interviews. Table 7 outlines the participant demographics.

Table 7.

Demographics of participants who attended an interview or focus group.

| PR healthcare professionals n = 6 | Individuals with COPD n = 5 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | ||

| Female | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Male | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Mean age at enrolment (years; SD) | 37.3 (10.7) | 73.6 (7.2) |

| Professions (%) | ||

| Respiratory physiotherapist | 4 (66.7%) | N/A |

| Respiratory nurse | 1 (16.7%) | N/A |

| Respiratory occupational therapist | 1 (16.7%) | N/A |

| Mean age (years; SD) at end of full time education (years) | N/A | 16.4 (2.7) |

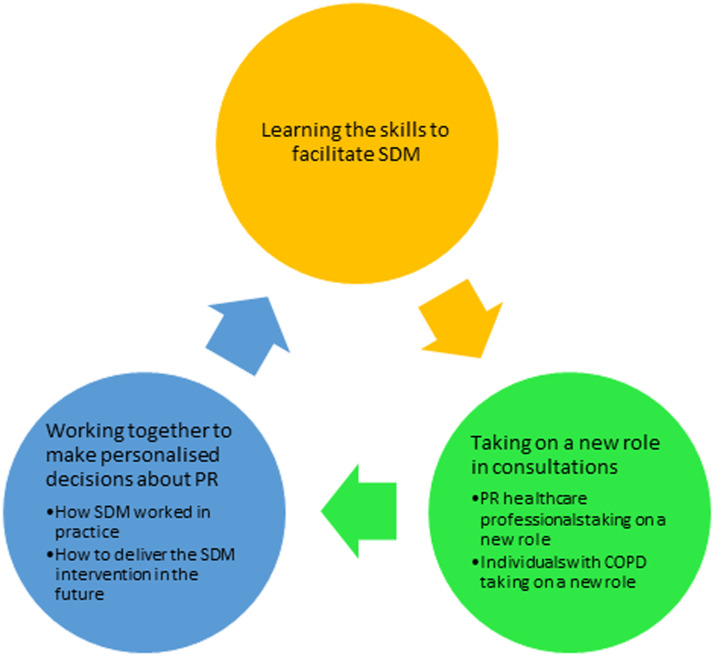

Formation of themes

Three themes were generated; learning the skills to facilitate SDM, taking on a new role in consultations and, working together to make personalised decisions about PR (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Generated themes and sub-themes illustrating the experiences and attitudes of individuals and healthcare professionals who engaged in the SDM intervention.

The themes are presented textually with an illustrative quote. Further quotes are provided in the supplemental materials. The term ‘participants’ is used to collectively describe PR healthcare professionals and individuals with COPD. If an attitude or experience is unique to PR healthcare professionals or individuals with COPD, ‘PRHCP’ or ‘COPD’ was added to the participant ID’s to signify this.

Learning the skills to facilitate SDM

PR healthcare professionals described developing their SDM skills through the decision coaching training’s theoretical and practical teaching methods and their growing confidence through intervention delivery.

P2_01SDMF: “…the decision making tool was maybe take a step back a little bit and think OK, actually the numbers for the other options are still good. You know they are viable... [So] when I was seeing the [study] patients I didn’t forget to say, ‘OK and why have you chosen this one?’ Whereas I know before I wouldn’t have done that… I would have said, ‘Why are you not doing the face to face program?’”

Taking on a new role in consultations

This theme captures the new roles that participants adopted.

PR healthcare professionals taking on a new role

PR healthcare professionals described preparing for SDM consultations by returning to the training materials. During consultations, they described unbiasedly discussing each option and the importance of taking a flexible, patient-centred approach.

P2_05SDMF: “…if they didn’t really engage or didn’t give me much information or respond, then I wouldn’t go into so much detail and just get the main pieces information from them and then see if there was wiggle room to open up the conversation a bit more, but if not I need to kind of not keep going on about it.”

Individuals with COPD taking on a new role

Individuals described preparing for SDM consultations by engagement with the PtDA. They spent time reflecting on their health and what each option would mean to them and their life. Some described their preferences for options changing following further reflection after starting their chosen programme.

P2_18COPD: “…you don’t know how it’s going to pan out until you actually put your toe in the water and test it, so I’ve had a little nibble at the gym in the hospital, which is great, I can’t knock that, the staff are fantastic, but my personal issue, and it might not apply to everybody else, was actually the logistics of getting there… The scientific side of it at the hospital is different to what I’ve set up at home. That’s there for my convenience, so if it snows and all the rest of it, I ain’t got to negotiate that, I can just jump on a treadmill, give it 10 min, use my weights and I’ve got it.”

Working together to make personalised decisions about PR

This theme encompasses how the SDM intervention worked in practice.

How SDM worked in practice

Participants felt the PtDA increased individuals’ health literacy and thereby their capacity to engage in SDM. However, they felt that the PtDA could be updated to better reflect current routine COPD care and individuals’ literacy levels. PR healthcare professionals described the SDM consultation as an easy extension of practice but took a flexible, patient-centred approach to ensure the conversation focussed upon preferences for the options with limited time on the research evidence. Individuals had mixed recollections of their explicit involvement in the decision-making process. Some individuals described their decision as a positive turning point for their COPD management.

P2_03SDMF: “Some of them were up for answering those questions, ‘Have you looked through the options? Have you weighed up what’s important to you? What do you think about the benefits or the drawbacks for each of them?’ A couple of other patients have been. ‘Yeah, I’ve read it. I know what I wanna do. This is what I want to do.’”

P2_19COPD: “…she did ask, can I get there OK and how am I going to do it…it was a good conversation.”

How to deliver the SDM intervention in the future

Participants felt the PtDA could be delivered at PR referral consultations to introduce the menu of options earlier to individuals and referrers. PR healthcare professionals felt the SDM consultation could be broadened to consider individuals overall healthcare goals and could be spread over multiple telephone or face to face visits. Individuals felt local site statistics would be more meaningful in the PtDA than population averages.

P2_14COPD: “…whoever says, well, I think you ought to do pulmonary rehab, it will improve your life, then here’s a booklet explaining it in a lot more detail.”

P2_09SDMF: “I don’t remember there being any goals or anything in the book… But that’s usually how I start, so whether that’s in the book and then you can say, ‘OK, these are the things that you’re saying are the issue,’ then it’s always easier to say ‘these are how we fix your issues’”

Discussion

Our PR SDM intervention was tested in a one arm study to explore its feasibility and acceptability. The results indicate the study processes were flexible enough to fit around usual care, the intervention was feasible to deliver within services, acceptable to individuals with COPD and PR healthcare professionals, and delivered with fidelity. Whilst the proposed recruitment targets proved to be realistic for both individuals with COPD and PR healthcare professionals, the recruitment rate for individuals with COPD was low at 13%. Retention rates were high with 100% of PR healthcare professionals and 90.32% of individuals with COPD contributing to the final dataset. At this research-innovation stage of integration into practice, the SDM consultation lasted an average of 5.80 min longer than standard PR assessment appointments. Findings suggest the PR SDM intervention supported uptake, and completion, of a PR programme, and reduced individuals’ decisional conflict.

The uptake and completion of PR for individuals receiving the SDM intervention was comparable to the 2020 national COPD audit (i.e., 15 out of 23 completed = 65.22%); 6 an increase for the host site’s completion rate (55.0%) during the study period. The most preferred PR option was centre-based PR with 61.29% of individuals opting for it. One (3.23%) opted for online SPACE for COPD and two (6.45%) opted for routine COPD care. During the SDM consultation five (17.86%) individuals were identified as ineligible for PR. Once starting PR, one (3.23%) individual swapped from centre-based PR to home-based PR with telephone support (i.e. SPACE for COPD).

Standardised scores for fidelity showed that all recorded SDM consultations contained aspects of SDM. However, items 1 (i.e. vocalising the presence of multiple options), 2 (i.e. vocalising support in the decision-making process), and 5 (i.e. implementing the individuals’ preference) each had a minimum score of 0, indicating they were conducted less comprehensively. Lower scores could reflect the instrument’s inability to capture implicit and unspoken elements of SDM both inside and outside of the SDM consultation. For example, lower scores on item 2 may be because the offer of support was not explicitly vocalised. However, the fact that PR healthcare professionals spent time going through the differing treatment options, discussing the advantages and disadvantages, and eliciting individuals’ preferences implied they were providing support. Similar observations have been made of the Observer OPTION-5 scale. 29 These authors suggest qualitative research currently provides the best insight into the SDM process as it captures the important contextual factors involved.

The SDM consultation was delivered in mean (SD) = 5.80 (5.55) min which dispelled concerns of the intervention significantly extending an PR assessment appointments. Reassuringly, this time is comparable to previously reported durations of SDM consultations. 30 However, longer recordings were significantly associated with the inclusion of more SDM elements. Despite this, there was no indication that length of consultation was associated with an option choice.

Individuals’ decisional conflict decreased following the intervention which aligns with other PtDA interventions across chronic and acute health conditions.10,31 Using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7), it was possible to calculate a sample size for a full scale randomised controlled trial (SD = 23.58, effect size = 1.24). This equated to 24 individuals (i.e. 12 individuals in the experimental group and 12 individuals in the control group). Considering a dropout rate of 20% and to ensure generalisability of the results, we propose a minimum sample size of 30 in each group.

Measures of patient activation did not change. It is unclear how measures of patient activation with healthcare are associated with SDM interventions, 32 it may be that this sample were already sufficiently engaged in their healthcare as they were content in attending appointments to choose a PR programme.

Qualitative findings highlighted the intervention was acceptable and highly valued by PR healthcare professionals for empowering individuals and instigating meaningful discussions about PR which supported choices aligned to individuals’ core values. PR healthcare professionals voiced an increased awareness of the evidence for the home-based PR options. This is at odds with the notion that healthcare professionals are experts in the medical evidence for all options. 33 PR healthcare professionals were well versed in the evidence for centre-PR but expressed increased awareness of the evidence for the home-based PR options, facilitated by their role in the intervention. This gave them increased confidence in unbiasedly offering the menu of options.

Whilst individuals with COPD were not acutely aware of their role change, they described preparing for and engaging in SDM with their PR healthcare professionals which was prompted by receipt of the PtDA. They expressed that their choice aligned with their values and preferences. The PR healthcare professionals perceived individuals informed reasoning between options was associated with them being more likely to complete their chosen programme. There is some evidence to support this observation as early data suggests SDM may increase in PR adherence. 12

Minor amends were proposed for a future randomised controlled trial and implementation of the SDM intervention into routine care (these are provided in full in the Supplemental material), including updates to the PtDA (e.g. amendments to the description of routine COPD care, reducing the PtDAs reading age to accommodate those with lower literacy and health literacy). Whilst the PtDA had a readability score suitable for Year 7 students (i.e., 11–12-year-olds) some individuals expressed difficulty understanding technical words, differentiating between options, and understanding the references. It would be beneficial to explore the average reading age within the research site’s PR population, instead of the overall COPD population, and amend the PtDA accordingly. It may also help to find a way to capture the literacy and health literacy needs of individuals to help PR healthcare professionals tailor their SDM approach further.

The flexible approach adopted by PR healthcare professionals meant that strict adherence to the three-talk model of SDM 34 was uncommon and spill-over of the SDM consultation outside of the audio recorded sessions may well have occurred. Further flexibility to deliver the intervention at multiple visits across the PR referral and assessment process was advised. This flexibility would support the dovetailing of SDM into all discussions related to the uptake of PR. It could be used in combination with educational resources and or behaviour change techniques such as goal setting and action planning to support decision-making for long-standing behavioural changes.35,36

Strengths and limitations

We have shown that a novel PR SDM intervention can be implemented into the PR pathway with support from a multidisciplinary team of PR healthcare professionals without significant extension to the PR assessment appointment. Additionally, the results suggest an approach to calculating a viable sample size needed for a full-scale randomised controlled trial.

As this was a feasibility study, it was not powered, did not have a control group, and data were collected from one centre. This means the results may not generalise to another service context. The recruitment rate was challenging (13%) and so a more personalised recruitment strategy would be required (e.g., telephone invitation instead of invitation letter). Certainly, effort will be needed as the PR SDM intervention is adapted and integrated to meet the needs of other services.

Conclusions

The SDM intervention was feasible and acceptable to individuals with COPD and PR healthcare professionals. Minor amends to the recruitment process, the PtDA and embedding further flexibility into the delivery and evaluation of the SDM consultation would further support future research and implementation into practice. There is some indication that the intervention reduces individuals’ decisional conflict and uncertainty, and may support uptake and completion of PR aligned to individuals’ preferences. Our next steps are to test this in a fully powered randomised controlled trial. This will inform its efficacy and scalability for all sites who offer a menu of PR options.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for A shared decision-making intervention for individuals living with COPD who are considering the menu of pulmonary rehabilitation treatment options; a feasibility study by AC Barradell, G Doe, HL Bekker, L Houchen-Wolloff, N Robertson and SJ Singh in Journal of Chronic Respiratory Disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants for their valued contribution to this research.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) and the Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) East Midlands. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or ARC East Midlands. Professor Singh is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator.

Study registration: Registered on Clinical Trials.gov (NCT04990180) in August 2021. Protocol version 7.0, 9 November 2021.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

This research was given ethical approval by South Leicester – Research Ethics Committee, reference 21/EM/0084.

ORCID iDs

AC Barradell https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3688-8879

L Houchen-Wolloff https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4940-8835

References

- 1.GOLD . Pocket guide to COPD diagnosis, management and prevention: 2023 report. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/ (2023, Accessed: 6 January 2023).

- 2.Rochester CL, Alison JA, Carlin B, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for adults with chronic respiratory disease: an official american thoracic society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023; 208(4): 1247–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell KE, Johnson-Warrington V, Apps LD, et al. A self-management programme for COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J 2014; 44(6): 1538–1547. DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00047814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton EJ, Mitchell KE, Johnson-Warrington V, et al. Comparison of a structured home-based rehabilitation programme with conventional supervised pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Thorax 2018; 73(1): 29–36. DOI: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houchen-Wolloff L, Orme M, Barradell A, et al. Web-based self-management program (SPACE for COPD) for individuals hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: nonrandomized feasibility trial of acceptability. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021; 9(6): e21728. DOI: 10.2196/21728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NACAP . National asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease audit programme (NACAP). Pulmonary rehabilitation clinical audit 2019. Clinical audit of pulmonary rehabilitation services in England, Scotland and Wales. Patients assessed between 1 march and 31 M. London, UK: NACAP, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houchen-Wolloff L, Spitzer KA, Candy S. Access to pulmonary rehabilitation services around the world. In: Pulmonary rehabilitation. Lausanne, Switzerland: European Respiratory Society, 2021, pp. 258–272. DOI: 10.1183/2312508X.10019020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barradell AC, Bourne C, Alkhathlan B, et al. A qualitative assessment of the pulmonary rehabilitation decision-making needs of patients living with COPD. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2022; 32(1): 23. DOI: 10.1038/s41533-022-00285-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekker HL, Hewison J, Thornton JG. Understanding why decision aids work: linking process with outcome. Patient Educ Couns 2003; 50(3): 323–329. DOI: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Sys Rev 2017; 4(4): CD001431. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breckenridge K, Bekker HL, Gibbons E, et al. How to routinely collect data on patient-reported outcome and experience measures in renal registries in Europe: an expert consensus meeting. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30(10): 1605–1614. DOI: 10.1093/ndt/gfv209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Y, Nuerdawulieti B, Chen Z, et al. Effectiveness of patient decision aid supported shared decision-making intervention in in-person and virtual hybrid pulmonary rehabilitation in older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare 2023; 15: 1357633X2311566. DOI: 10.1177/1357633X231156631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barradell AC, Gerlis C, Houchen-Wolloff L, et al. Systematic review of shared decision-making interventions for people living with chronic respiratory diseases. BMJ Open 2023; 13(5): e069461. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barradell AC, Singh SJ, Houchen-Wolloff L, et al. A pulmonary rehabilitation shared decision-making intervention for patients living with COPD: present: protocol for a feasibility study. ERJ Open Res 2022; 8(2): 00645. DOI: 10.1183/23120541.00645-2021. Erratum in: ERJ Open Res. 2022 Jul 04; 8(3): PMID: 35677396; PMCID: PMC9168082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barradell AC, Robertson N, Houchen-Wolloff L, et al. Exploring the presence of implicit bias amongst healthcare professionals who refer individuals living with COPD to pulmonary rehabilitation with a specific focus upon smoking and exercise. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2023; 18: 1287–1299. DOI: 10.2147/COPD.S389379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sepucha KR, Abhyankar P, Hoffman AS, et al. Standards for universal reporting of patient decision aid evaluation studies: the development of SUNDAE checklist. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27: 380–388. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International J Qual in Health Care 2007; 19(6): 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elwyn G, Tsulukidze M, Edwards A, et al. Using a ‘talk’ model of shared decision making to propose an observation-based measure: observer OPTION 5 item. Patient Educ Couns 2013; 93(2): 265–271. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making 1995; 15(1): 25–30. DOI: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004; 39(4 Pt 1): 1005–1026. DOI: 10.1111/J.1475-6773.2004.00269.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat Med 1995; 14: 1933–1940. DOI: 10.1002/sim.4780141709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006; 18(1): 59–82. DOI: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18(1): 148. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Portney L, Watkins M. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice, https://babymariam.gm/sites/default/files/webform/pdf-foundations-of-clinical-research-applications-to-practice-3rd-e-leslie-g-portney-mary-p-watkins-pdf-download-free-book-d3094a3.pdf (2009, accessed 29 November 2022).

- 25.Burr V. Social constructionism. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Inc, 2015. DOI: 10.4324/9781315715421/SOCIAL-CONSTRUCTIONISM-VIVIEN-BURR. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Teo T. (ed) Encyclopedia of critical psychology. New York, NY: Springer, 2014, pp. 1947–1952. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlay L, Gough B. Reflexivity: a practical guide for researchers in health and social sciences. 1st ed. Cornwall, Great Britain: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003. DOI: 10.1002/9780470776094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, et al. (2015) The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual Res Psychol 12(2): 202–222. DOI: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams D, Edwards A, Wood F, et al. Ability of observer and self-report measures to capture shared decision-making in clinical practice in the UK: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e029485. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Légaré F, Thompson-Leduc P. Twelve myths about shared decision making. Patient Educ Counsel 2014; 96(3): 281–286. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine 2020; 99(32): e21389. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith SG, Pandit A, Rush SR, et al. The role of patient activation in preferences for shared decision making: results from a national survey of U.S. Adults. J Health Commun 2016; 21(1): 67–75. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1033115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spatz ES, Krumholz HM, Moulton BW. Prime time for shared decision making. JAMA 2017; 317(13): 1309–1310. DOI: 10.1001/JAMA.2017.0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ 2017; 359: j4891. DOI: 10.1136/BMJ.J4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gültzow T, Hoving C, Smit ES, et al. Integrating behaviour change interventions and patient decision aids: how to accomplish synergistic effects? Patient Educ Counsel 2021; 104(12): 3104–3108. DOI: 10.1016/J.PEC.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Patients Association . Shared decision making from the perspective of clinicians and healthcare professionals (20 June 2022) - patient engagement - patient Safety Learning - the hub. Harrow, UK: The Patients Association, https://www.pslhub.org/learn/patient-engagement/the-patients-association-shared-decision-making-from-the-perspective-of-clinicians-and-healthcare-professionals-20-june-2022-r7065/ (2022, Accessed: 18 January 2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for A shared decision-making intervention for individuals living with COPD who are considering the menu of pulmonary rehabilitation treatment options; a feasibility study by AC Barradell, G Doe, HL Bekker, L Houchen-Wolloff, N Robertson and SJ Singh in Journal of Chronic Respiratory Disease.