Abstract

Background:

Canine and human osteosarcoma are similar in clinical presentation and tumor genomics. Giant breed dogs experience elevated osteosarcoma incidence, and taller stature remains a consistent risk factor for human osteosarcoma. Whether evolutionarily conserved genes contribute to both human and canine osteosarcoma predisposition merits evaluation.

Methods:

A multi-center sample of childhood osteosarcoma patients and controls underwent genome-wide genotyping and imputation. Ancestry-adjusted SNP associations were calculated within each dataset using logistic regression, then meta-analyzed across the three datasets, totaling 1091 patients and 3026 controls. Ten regions previously associated with canine osteosarcoma risk were mapped to the human genome, spanning ~6Mb. We prioritized association testing of 5,985 human SNPs mapping to candidate osteosarcoma risk regions detected in Irish wolfhounds, the largest dog breed studied. Secondary analyses explored 6,289 additional human SNPs mapping to candidate osteosarcoma risk regions identified in Rottweilers and greyhounds.

Results:

Fourteen SNPs were associated with human osteosarcoma risk after adjustment for multiple comparisons, all within a 42kb region of human Chromosome 7p12.1. The lead variant was rs17454681 (OR=1.25, 95%CI: 1.12–1.39; P=4.1×10−5), and independent risk variants were not observed in conditional analyses. While the associated region spanned 2.1Mb and contained eight genes in Irish wolfhounds, associations were localized to a 50-fold smaller region of the human genome and strongly implicate GRB10 (growth factor receptor-bound protein 10) in canine and human osteosarcoma predisposition. PheWAS analysis in UK Biobank data identified noteworthy associations of the rs17454681 risk allele with varied measures of height and pubertal timing.

Conclusions:

Our comparative oncology analysis identified a novel human osteosarcoma risk allele near GRB10, a growth inhibitor that suppresses activated receptor tyrosine kinases including IGF1R, PDGFRB, and EGFR. Epidemiologists may benefit from leveraging cross-species comparisons to identify haplotypes in highly susceptible but genetically homogenous populations of domesticated animals, then fine-mapping these associations in diverse human populations.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma, Genome-Wide Association Study, comparative oncology, Insulin-Like Growth Factor Receptor, Growth Factor Receptor Bound Protein 10

1. INTRODUCTION

Osteosarcoma (OS) is a malignant bone tumor, most commonly diagnosed in children and young adults.(1) The disease arises from mesenchymal-derived cells, most likely osteoblasts, and typically develops at the metaphysis of long bones.(2) The development of osteosarcoma coincides with periods of rapid bone growth.(3) Females are diagnosed at significantly younger ages than males, and this is believed to correspond to their earlier pubertal onset.(4) While the majority of OS appears to be sporadic, as many as 25% of cases may be attributable to rare variants in genes associated with cancer predisposition syndromes (e.g., TP53, CDKN2A, MEN1, VHL, POT1, APC, MSH2, ATRX).(5)

The etiology of OS among individuals who are not affected by an underlying cancer predisposition syndrome remains poorly understood. A single genome-wide association study (GWAS) of OS identified two putative risk alleles in subjects of European ancestry,(6) but a subsequent study was unable to replicate those findings.(7) Common germline variants involved in DNA repair,(8) growth factor receptor pathways,(9, 10) antigen processing and presentation,(11) and telomere maintenance(12, 13) have also been evaluated using candidate-gene approaches. More recently, polygenic risk score approaches have demonstrated that genetic predisposition to longer telomere length and to taller stature are associated with increased OS risk,(12, 14) with the former being replicated in an independent multiethnic sample (7) and the latter being partially replicated among OS patients known to harbor a pathogenic cancer susceptibility gene variant.(15) However, emerging evidence also suggests significant heterogeneity in effects across racial and ethnic groups.(7, 16)

Obtaining biospecimens for OS genetic research that are comparable in number to studies of more common pediatric malignancies remains infeasible due to the lower incidence of OS. Given limited successes to date identifying robust associations between common genetic variation and OS risk, novel methods appear warranted. One opportunity may be to leverage comparative oncology approaches,(17) as canine osteosarcoma exhibits remarkable resemblance to its human counterpart in terms of both clinical presentation and underlying tumor genetic profiles. OS is most common in large and giant breed dogs, and shares common site predilection affecting long bones in the limbs.(18) Genomic studies have unveiled shared genetic alterations across species, including somatic alterations in TP53, PTEN, and ATRX.(19, 20) By leveraging these parallels, comparative oncology offers a natural model to investigate potential shared genetic architecture underlying OS predisposition in both canines and humans.(21)

A previous GWAS in Irish wolfhounds, greyhounds, and Rottweilers implicated a number of regions in conferring canine OS risk, but demonstrated little overlap across breeds.(22) Given that growth rates and height attainment remain the most strongly validated risk factors for human OS risk, the current study prioritized the subset of associated regions from Irish wolfhounds, the only giant-breed canine included in that GWAS. We then examined OS associations at orthologous human loci in a multi-ethnic sample of 1,091 pediatric OS cases and 3,026 controls. Additional exploratory analysis of signals from greyhounds and Rottweilers were conducted, and in silico analyses of lead variants were performed. We aimed to refine broad association signals detected in purebred dog genomes by fine-mapping syntenic loci in diverse human populations, thereby leveraging comparative oncology for OS risk allele detection.

2. METHODS

2.1. Defining regions from canine OS studies:

Karlsson, et al. performed a prior GWAS of canine OS in a sample of 267 greyhounds [153 cases (58% male), 114 controls (57% male)], 135 Rottweilers [80 cases (48% male), 55 controls (49% male)], and 141 Irish wolfhounds [76 cases (38% male), 65 controls (42% male)], genotyped at 169,000 SNPs using the Illumina canine HD array.(22) For sample pairs with identity-by-descent estimates >0.25, one member of the pair was excluded. Given their observation of substantial genetic heterogeneity across breeds and our a priori hypothesis that OS associations in giant-breed dogs will have greatest translational relevance to the pediatric disease, our primary analysis focused on regions reaching a P-value <1.0×10−4 in Irish wolfhounds (N=2 regions, spanning 3Mb of the orthologous human genome). We also explored regions reaching a P-value <1.0×10−4 in greyhounds (2 regions, spanning 52kb of the orthologous human genome) and in Rottweilers (6 regions, spanning 3.02Mb of the orthologous human genome). Karlsson, et al. defined associated regions in canines based on a single peak of SNPs in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2 >0.8) and located within 1Mb of the sentinel variant. The average length of the associated regions, in base-pairs, was largest in Irish wolfhounds, followed by Rottweilers, and then greyhounds, in line with estimated inbreeding coefficients for each breed.(22) In line with suggested “best practices” from the Integrated Canine Data Commons,(23) we converted these canFam2 regions to the canFam6 build, then mapped to orthologous regions of the human genome (GRCh37/hg19) using the ‘liftover’ tool in the UCSC browser.(24)

2.2. California Osteosarcoma Case-Control Study:

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of California at Berkeley and the California Department of Public Health. The California Department of Public Health Genetic Diseases Screening Program obtains newborn blood samples from all neonates born within the state for the purpose of disease screening. Remaining bloodspots have been archived at −20°C since 1982 and are available for approved research. We linked statewide birth records (1982–2009) with cancer diagnosis data from the California Cancer Registry (CCR) (1988–2011). Cases were diagnosed with osteosarcoma before age 20 years, as per CCR record. Controls were matched based on birth year, sex, and maternal self-reported race/ethnicity. Detailed characteristics of these subjects and the data linkage have been reported previously.(7)

Dried bloodspot DNA samples were assigned to genotyping plates using blocked randomization according to case-control status, reported race/ethnicity, and sex. DNA was genotyped on the Affymetrix Axiom Latino Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) using an Affymetrix TITAN system, and raw image files were processed with Affymetrix Genetools, as previously described.(7) Additional controls were included from the Genetic Epidemiology Research on Aging (GERA) study (dbGaP study accession: phs000788.v1.p2), genotyped using the same array, and integrated as previously described.(7)

Call rate filtering for SNPs and samples was performed iteratively as follows: SNPs with call rates <92% were removed, followed by samples with call rates <95%, SNPs with call rates <97%, and samples with call rates <97%. Any SNP displaying a significant departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P<1.0×10−5 among controls of European ancestry was excluded. Samples with mismatched reported versus genotyped sex were excluded. All quality-control was performed using the PLINK open-source software.(25) Ancestry-informative principal components were calculated separately for individuals of each self-identified racial/ethnic group (i.e., Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic white) along with HapMap reference samples (ASW, CEU, CHB, CHD, GIH, JPT, LWK, MEX, MKK, and YRI). Using genome-wide SNP data from these HapMap Phase 3 samples, individuals showing evidence of mismatched ancestry (>3 SDs from mean MXL or CEU values on the first three principal components) were excluded, as previously described.(7) Haplotype phasing and imputation was performed with SHAPEIT v2.79028 and Minimac3 software, using phased genotype data from the 2016 release of the Haplotype Reference Consortium.(26) Poorly-imputed SNPs with imputation quality (info) scores less than 0.60 or posterior probabilities less than 0.90 were excluded.

2.3. National Cancer Institute/Geisinger Osteosarcoma Data Set:

A second OS case-control data set was constructed from dbGaP study accession phs000734.v1.p1 (A Genome-Wide Association Study [GWAS] of Risk for Osteosarcoma) and phs000381.v1.p1 (eMERGE Geisinger eGenomic Medicine MyCode Project Controls), as previously described.(14) OS cases were predominantly children and adolescents (aged <21 years),(6) although individual-level age data were unavailable. Specimens were genotyped on the Illumina OmniExpress array (Illumina Inc, San Diego, California). SNPs with call rates <0.98 were removed from analyses. After the removal of poorly performing SNPs, subjects with genotyping call rates <0.97 were removed. Ancestry-informative PCs were calculated with PLINK, including HapMap Phase 3 reference samples. Subjects who fell more than 3 SDs from the mean CEU values on PCs 1–3 were excluded from further analyses. After removal of subjects with non-European ancestry, SNPs with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P<1.0×10−5 among controls were removed, as were subjects with discordant genotyped versus reported sex.

OS cases and controls from the California/GERA and NCI/Geisinger datasets were compared using identity-by-descent (IBD) measures calculated with PLINK (IBD >0.18), and one member of any duplicated or cryptically-related sample pair was excluded. A total of 657 non-overlapping cases of European ancestry and 1183 controls were included in the final NCI/Geisinger data set. Haplotype phasing and imputation were performed using identical methods as those used for the California sample (i.e., SHAPEIT, Minimac3, 2016 Haplotype Reference Consortium reference panel) and were filtered based on imputation quality (info) scores <0.60 or posterior probabilities <0.90.

2.4. Statistical analyses:

Single-SNP association statistics for imputed and directly genotyped SNPs were calculated using logistic regression in the SNPTESTv2 program, using an allelic additive model and probabilistic genotype dosages. The effect of individual SNPs on osteosarcoma risk was calculated with adjustment for the first 5 ancestry-informative PCs. Analyses were stratified by ethnicity and study site (non-Hispanic white California case-control sample, non-Hispanic white NCI/Geisinger case-control sample, Hispanic California case-control sample). Fixed-effects meta-analysis was performed using the META program and variants displaying high inter-dataset heterogeneity (I2 >75%) were flagged.(27) Lead variants were identified by p-values and logistic regression analyses were repeated, conditioning on the lead variant (additive model), to identify potential independent signals in associated regions. Sex-stratified analyses were conducted using mixed effects meta-analysis, examining association signals separately in males and females using a random-effects model and then combining across sexes. Heterogeneity of effect across biological sex was assessed using Cochran Q test.

To address the high level of linkage between variants in the fine-mapped regions, we used subject-level data and the “Genetic type 1 error calculator” package to determine the effective number of independent tests performed.(28) We then applied a Bonferroni correction to assess the statistical significance of associations in single-SNP analyses, resulting in a significance threshold of 8.8×10−5 (0.05/566 effective tests in primary analysis of regions identified in Irish wolfhounds). While we controlled for the family-wise error rate by Bonferroni correction in analysis of regions first identified in Irish wolfhounds, we used a less conservative FDR adjustment in exploratory analyses of regions identified in greyhounds and Rottweilers.

2.5. Osteosarcoma trio data:

A total of 92 OS family trios were genotyped on the Illumina HumanOmniExpress-12v1-A chip and imputed toHaplotype Reference Consortium/HRC, as previously described.(29) The lead SNP from fine-mapping and additional SNPs located ± 20kb were assessed for association in PLINK v1.9 using the transmission disequilibrium test (--tdt) and maternal parent-of-origin effect (--tdt poo). The family-wise error rate was controlled by Bonferroni correction. Separately, the lead SNP was assessed with a parent-of-origin model in EMIM (Estimation of Maternal, Imprinting and interaction effects using Multinomial modeling),(30) using data from the 92 trios plus an additional 73 case-mother duos and 33 case-father duos.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Osteosarcoma case-control genotyping dataset:

After quality-control and removal of overlapping samples across datasets, a total of 1091 cases and 3026 controls remained for genomic analysis. This included 657 non-Hispanic white cases and 1183 non-Hispanic white controls from NCI/Geisinger, 207 non-Hispanic white cases and 696 non-Hispanic white controls from California/GERA, and 227 Hispanic cases and 1147 Hispanic controls from California/GERA. As previously reported in studies using these data, genome-wide inflation of test statistics was low (λ=1.03) and indicated adequate control of population stratification in the PC-adjusted regression models.(6, 7, 14)

3.2. Primary analysis of regions associated in Irish wolfhounds:

Two regions were identified by Karlsson, et al. as associated with OS risk among Irish wolfhounds at a P-value <1.0×10−4, spanning 2.33Mb of the canine genome.(22) These were successfully mapped to two orthologous regions of the human genome at Chr7p12.1 and Chr11q24.1, spanning 3.0Mb. A total of 5985 SNPs with MAF>0.05 were successfully genotyped or imputed across all three datasets, representing 566 “effective tests” after adjusting for SNP linkage.(28)

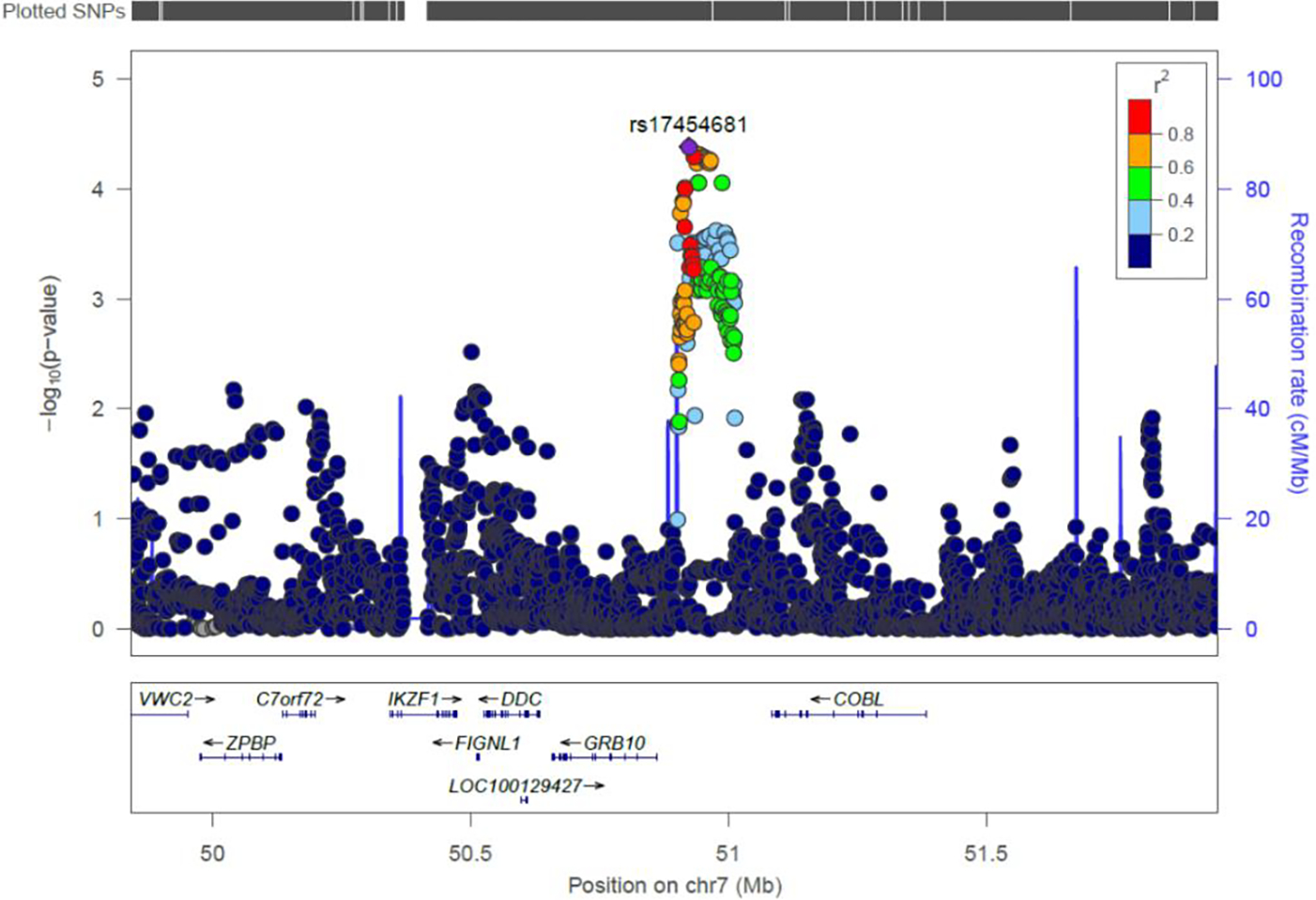

A total of 14 SNPs spanning an approximately 42kb region of Chr7p12.1 were associated with OS risk at a Bonferroni-corrected level of statistical significance (P<8.8×10−5) (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1). The lead variant was rs17454681 (P=4.1×10−5), a noncoding C/T polymorphism located 63kb upstream from GRB10 (growth factor receptor-bound protein 10). The minor (T) allele was associated with increased risk of OS (OR=1.25, 95%CI: 1.12–1.39). The risk allele frequency was 42% in the full case-control dataset, 48% in non-Hispanic whites, and 29% in Hispanics, aligning with data from 1000 Genomes control samples (46% European, 38% Native American, 28% African). The 13 other significantly associated variants in the region were all in high LD with lead variant rs17454681 (R2: 0.59–0.96), and conditional analyses adjusting for rs17454681 did not reveal residual association at other SNPs on 7p12.1 (P>0.01).

FIGURE 1.

Association of SNPs with childhood osteosarcoma risk in a region of chromosome 7p12.1 (1091 cases, 3026 controls), orthologous to a region previously associated with OS risk in Irish wolfhounds. The lead variant, rs17454681 (purple diamond), is ~63kb upstream of GRB10 (growth factor receptor-bound protein 10). Other SNPs are displayed by color, showing their extent of genetic linkage with rs17454681. Recombination rate, genetic position (37/hg19), and the locations of nearby genes are indicated.

3.3. In-silico functional analysis and PheWAS of rs17454681:

In silico analyses revealed that rs17454681 maps to an H3K4me3 promoter histone mark in three tissues (H1-derived mesenchymal stem cells, lung, and spleen) and to an H3K4me1 enhancer histone mark in seven tissues, including human osteoblasts.(31) These data suggest a potential role for rs17454681 in regulating gene transcription, but it was not identified as a significant eQTL in any gene expression datasets in GTeX.(32) However, we were unable to identify eQTL mapping data for the cell types most relevant to OS development, including mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts. Another complicating factor is that the 7p12.1 region containing GRB10 is heavily imprinted, with the paternal allele expressed in the brain from fetal life until adulthood and the maternal allele expressed elsewhere.(33, 34) Standard eQTL mapping is performed using an allelic additive model that does not account for imprinting effects and is therefore poorly suited for detecting transcriptional regulation of GRB10 by cis-acting alleles.

To assess potential pleiotropic effects of rs17454681, we used UK Biobank data to perform a Phenome-Wide Association Study (PheWAS) analysis examining whether the SNP was associated with any of 2418 other phenotypic traits.(35) The only trait that achieved genome-wide statistical significance was “relative age at first facial hair” (P=1.1×10−9; N=151,113 male subjects), where the OS risk allele was associated with a younger age at first development of facial hair. Given the strong epidemiologic connection between pubertal timing and OS development, we also investigated whether rs17454681 was associated with differences in age at menarche, but found no evidence that it influenced this trait (P=0.92; N=176,008 female subjects). The OS risk allele at rs17454681 was also nominally associated with other relevant traits, including taller standing height (P=3.8×10−5; N=336,474), sitting height (P=6.7×10−4; N=336,172), and comparative height at age ten (P=7.7×10−3; N=332,021). Given the discordant associations between rs17454681 and sex-specific measures of pubertal timing, we investigated potential differences in the risk of OS conferred by this variant among males versus females in sex-stratified analyses. As seen in Figure 2, rs17454681 was significantly associated with OS risk among both females (OR=1.33; 95%CI: 1.11–1.55) and males (OR=1.18; 95%CI: 1.01–1.35), but this difference in magnitude of effect was not significantly different across strata of sex (P=0.29).

FIGURE 2.

Mixed-effects meta-analysis of the association between rs17454681 and osteosarcoma risk in three datasets, stratified by biological sex. The T allele is associated with OS risk among females (OR=1.33; 95%CI: 1.11–1.55) and among males (OR=1.18; 95%CI: 1.01–1.35), with differences in the magnitude of effect across strata of sex not reaching statistical significance (P=0.29).

3.4. Family-based analysis of rs17454681:

Due to genomic imprinting in the 7p12.1 locus where rs17454681 and GRB10 reside, it may be that only the maternal allele is relevant to bone-related traits such as OS risk. While individuals homozygous for the risk allele will have both a paternally-derived and a maternally-derived risk allele, resolving which parent transmitted the rs17454681-T allele among heterozygous individuals requires genotyping OS patients and their parents. We examined the association of rs17454681 with OS risk in a sample of 92 parent-case trios, but were unable to detect significant association using either a transmission disequilibrium test (OR=1.03; 95%CI: 0.68–1.55) or a maternal parent-of-origin effect (P=0.64). The SNPs located within a 20kb window of rs17454681 and with transmitted and untransmitted allele counts >5 also did not show statistical significance in either test after multiple testing correction. We expanded the analysis to include the 92 trios, plus an additional 73 case-mother duos and 33 case-father duos, and evaluated associations using EMIM.(30) Neither the maternal effect (controlling for child effect) nor the child effect (controlling for maternal effect) provided evidence of a parent-of-origin effect in these OS patients, although the sample size was modest.

3.5. Secondary analysis of regions associated in greyhounds and Rottweilers:

Two regions were identified by Karlsson, et al. as associated with OS risk among greyhounds at a P-value <1.0×10−4, spanning 44kb of the canine genome, and an additional six regions in Rottweilers, spanning 2.1Mb of the canine genome.(22) These were successfully mapped to orthologous regions of the human genome, spanning 52kb and 3.0Mb, respectively. A total of 6289 SNPs with MAF>0.05 were successfully genotyped or imputed in these regions across the three human OS datasets and evaluated for their association with OS risk. No SNPs were associated with OS risk after FDR-based adjustment for multiple comparisons. The lead SNP was rs2995271 (OR=0.81; Punadjusted=4.5×10−4, PFDR=0.44). It is in an intergenic region of human Chromosome 10, orthologous to a region of canine Chromosome 2 that was associated with OS risk in Rottweilers. A region of CDKN2B that has been associated with multiple human cancers in adults and children,(36, 37) and with OS risk in greyhounds,(22) also did not show evidence of association in our childhood OS dataset (Supplemental Table 1).

4. DISCUSSION

We employ a comparative oncology approach to investigate the role of putative OS risk loci originally identified in giant breed canines (Irish wolfhounds) and evaluate whether the orthologous human regions harbor childhood OS risk variants in a large, multi-ethnic case-control sample. A 42kb region of human Chromosome 7 was found to contain 14 linked SNPs associated with OS risk at a Bonferroni-corrected level of statistical significance. The lead SNP, rs17454681, is located in a putative H3K4me3 promoter mark in mesenchymal stem cells and an H3K4me1 enhancer mark in osteoblasts, upstream of GRB10. The GRB10 gene encodes Growth Factor Receptor-Bound Protein 10, also known as Insulin Receptor-Binding Protein Grb-IR, a biologically plausible candidate for influencing both normal and malignant bone growth. Variants in IGF1 and IGF1R are among the strongest genetic signals in GWAS of canine stature, highlighting a central role for members of the insulin-like growth factor pathway in controlling body size.(38, 39) Further, our PheWAS analyses identified a potential role for the lead GRB10 variant in influencing various measures of adult and childhood height attainment, as well as a measure of male pubertal timing.

Comparative oncology presents an attractive approach to improve risk allele discovery but is limited by the degree of molecular and epidemiologic similarity between a given cancer type across two or more species. Canine OS has many similarities to the human disease, including somatic mutations, site predilection, and incidence rates that increase with height.(18–20) By focusing on OS in children and adolescents and comparing to OS in giant breed canines, we further increased this similarity and optimized our analyses for the discovery of biological pathways affecting both normal and malignant bone growth. Although the prior GWAS of OS risk in Irish wolfhounds identified an associated region of canine Chromosome 18, the extended haplotype structure of purebred dogs limited resolution to a 2.1Mb region containing eight genes. In human data, association was localized to an approximately 50-fold smaller region and strongly implicated GRB10.

eQTL data did not suggest that rs17454681 influences expression of GRB10 or other genes in the region, but this must be viewed in context. Expression data from the most OS-relevant tissues (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells, osteoblasts) were not available for query. Furthermore, the region is extensively imprinted and standard eQTL modeling approaches do not incorporate parent-of-origin effects. Thus, the downstream gene target through which alleles in the region may confer OS risk remains difficult to assign. However, GRB10 is a leading contender based on both its proximity and on extensive experimental work identifying it as a potent growth inhibitor.(40, 41)

Mice engineered to be deficient for the maternal GRB10 allele display both fetal and placental overgrowth, with mutant pups 30% larger than wild-type.(42) Conversely, mice with maternal duplication of GRB10 exhibit significant prenatal and postnatal growth delay.(40, 41) The expression of GRB10 is observed to decline with age in metaphyseal bone, while increasing with age in the growth plate.(43) This suggests that GRB10 helps to regulate the decline in longitudinal bone growth that occurs with age.(43) Maternal uniparental disomy for GRB10 is also a candidate cause of Silver-Russell syndrome-2 (SRS2; OMIM: 618905), a disorder characterized by persistent growth delay.(44) Interestingly, cranial growth is relatively unaffected in subjects with SRS2, which may be due to paternal-specific expression of GRB10 in the human brain.

Phosphoproteomic profiling has shown that the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex-1 (mTORC1) stabilizes GRB10 through phosphorylation, leading to downstream inhibition of the oncogenic PI3K and MAPK/ERK signaling cascades.(45) GRB10 directly binds and suppresses a range of activated receptor tyrosine kinases that are known to help drive osteosarcoma growth,(46) including insulin-growth factor type 1 receptor (IGF-1R), PDGFRB, and EGFR.(47, 48) A Phase II trial of 45 pediatric and young adult patients with recurrent or refractory sarcoma (NCT01614795), including 11 with OS, evaluated clinical activity of the anti-IGF-1R antibody cixutumumab combined with mTOR inhibition (temsirolimus), but treatment did not result in objective responses.(49) Because GRB10 functions as an endogenous inhibitor of IGF-1R, our data may help shed light on these negative trial results. While cixutumumab therapy can reduce IGF-1R signaling, its combination with an mTOR inhibitor may simultaneously destabilize GRB10 and lead to upregulation of the PI3K and/or MAPK/ERK pathways. This may also help explain why a different Phase II trial of cixutumumab and temsirolimus found that sarcoma-intrinsic IGF-1R expression did not predict response to therapy (NCT01016015).(50)

Our data suggest that GRB10, and potentially its downstream targets like IGF-1R, are involved in OS tumor initiation and may therefore be suboptimal therapeutic targets for patients with established tumors. Future work leveraging spontaneous syngeneic models of OS development could help to reveal whether targeting GRB10 or the IGF-1R signaling axis can facilitate OS chemoprevention. Such approaches may have potential applications in high-risk individuals during critical windows of development, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome patients approaching puberty.

This study has several important limitations that merit discussion. Up to 25% of OS diagnoses may be attributable to cancer predisposition syndromes,(5) but we were unable to assess private or rare variants in our case-control and trio subjects due to use of an array-based genotyping platform. While GWAS approaches have successfully identified common polymorphisms contributing to a diverse array of childhood cancers,(37, 51–54) the polygenicity of OS appears comparatively low.(6, 7) Traditional GWAS approaches employ an “allelic additive” model, which presupposes that two copies of a risk allele – one from each parent – will be of equal importance and confer twice the risk of a single copy. Our analysis of the imprinted 7p12.1 region was unable to resolve whether the rs17454681-T risk allele was maternally or paternally derived in heterozygous individuals, and also treated T/T homozygotes as possessing two copies of the risk allele, despite only one of these alleles expected to be active. The likely effect of this is an overall reduction in statistical power and reduced precision in estimating odds ratios. While we did attempt to address this issue by modeling parent-of-origin effects in a set of complete and partial parent-child OS trios, the total sample size was modest and significant associations were not observed. Collection of trios is logistically challenging, particularly in studies of childhood cancer that often leverage archival biospecimens. An alternative approach to resolving the parental origin of alleles integrates genealogic reconstruction with long-range phasing, but requires population-scale genotyping data that has only been conducted in Iceland to date.(55)

We have assembled GWAS data from a multi-ethnic cohort of OS patients that exceeds the sample size of any prior GWAS of OS risk, augmenting our analytic approach through integration with a prior study of OS in canines. We identify a new potential OS risk allele in an imprinted region of Chromosome 7 that implicates GRB10 in influencing both healthy and malignant bone growth in both dogs and humans. These results suggest that cancer epidemiologists may benefit from leveraging cross-species comparisons that seek to identify risk loci in genetically homogeneous but highly susceptible purebred canines, and to subsequently fine-map these associations in diverse human populations. Future research is needed to validate our findings and to explore whether GRB10 and its downstream binding partners may serve as tractable targets for OS chemoprevention.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Characteristics of osteosarcoma patients and control subjects included in case-control genotyping analyses.

| Mean (SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Sample Provenance | Race/Ethnicity | Age at Dx | Percent male | Genotyping Array | ||

|

| |||||||

| Cohort 1 | Cases | 207 | CA Dept of Public Health CDPH + GERA (phs000788.v1.p2) |

non-Hispanic White | 12.4 yrs (3.4) |

55.1 | Affymetrix Axiom |

| Controls | 696 | NA | 56.3 | ||||

| Cohort 2 | Cases | 227 | CA Dept of Public Health CDPH + GERA (phs000788.v1.p2) |

Hispanic/Latino | 12.2 yrs (3.6) |

53.7 | Affymetrix Axiom |

| Controls | 1147 | NA | 55.6 | ||||

| Cohort 3 | Cases | 657 | NCI (phs000734.v1.p1) Geisinger (phs000381.v1.p1) |

non-Hispanic White | –a | 58.8 | Illumina OmniExpress |

| Controls | 1183 | NA | 60.7 | ||||

Patients are predominantly children and adolescents (age <21), but individual-level age data are not provided in dbGaP.

HIGHLIGHTS:

Genes involved in osteosarcoma (OS) predisposition may be conserved across species.

An OS risk locus in Irish wolfhounds conferred childhood OS risk in a large sample.

Cross-species mapping implicated GRB10, a key regulator of IGF-1R signaling.

Risk haplotypes from domesticated animals can be fine-mapped in human populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Datasets used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from dbGaP study accession phs000734.v1.p1 [A Genome-wide Association Study (GWAS) of Risk for Osteosarcoma] and phs000381.v1.p1 [eMERGE Geisinger eGenomic Medicine (GeM) - MyCode Project Controls]. Samples and data in this study were provided by the Geisinger MyCode® Project. Funding for the MyCode® Project was provided by a grant from Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the Clinic Research Fund of Geisinger Clinic. Funding support for the genotyping of the MyCode® cohort was provided by a Geisinger Clinic operating funds and an award from the Clinic Research Fund. Data from the Kaiser Resource for Genetic Epidemiology Research on Aging (GERA) Cohort were downloaded from dbGaP (Study Accession: phs000788.v1.p2).The RPGEH was supported by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Wayne and Gladys Valley Foundation, the Ellison Medical Foundation, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and the Kaiser Permanente National and Northern California Community Benefit Programs.

Biospecimens and/or data used in this study were obtained from the California Biobank Program (SIS request number 550). The California Department of Public Health is not responsible for the results or conclusions drawn by the authors of this publication. Any uploading of genomic data and/or sharing of these biospecimens or individual data derived from these biospecimens has been determined to violate the statutory scheme of the California Health and Safety Code Sections 124980(j), 124991(b), (g), (h), and 103850 (a) and (d), which protect the confidential nature of biospecimens and individual data derived from biospecimens. Certain aggregate results may be available from the authors by request.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the Comparative Oncology Group at the Duke Cancer Institute (P30CA014236). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. KMW and AJdS were supported by ‘A’ Awards from The Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation. LAG was supported by a Young Investigator Award from Hyundai Hope on Wheels and a seed grant from the Triangle Center for Evolutionary Medicine. TY was supported by a St. Baldrick’s Career Award. SEL was supported by the Donna Wick CAPE Undergraduate Research Award.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or personal interests to report or disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Savage SA, Mirabello L. Using epidemiology and genomics to understand osteosarcoma etiology. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:548151. Epub 2011/03/26. doi: 10.1155/2011/548151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mutsaers AJ, Walkley CR. Cells of origin in osteosarcoma: mesenchymal stem cells or osteoblast committed cells? Bone. 2014;62:56–63. Epub 2014/02/18. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirabello L, Pfeiffer R, Murphy G, Daw NC, Patino-Garcia A, Troisi RJ, Hoover RN, Douglass C, Schuz J, Craft AW, Savage SA. Height at diagnosis and birth-weight as risk factors for osteosarcoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(6):899–908. Epub 2011/04/06. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9763-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotterill SJ, Wright CM, Pearce MS, Craft AW, Group UMBTW. Stature of young people with malignant bone tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42(1):59–63. Epub 2004/01/31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.10437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirabello L, Zhu B, Koster R, Karlins E, Dean M, Yeager M, Gianferante M, Spector LG, Morton LM, Karyadi D, Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Bhatia S, Song L, Pankratz N, Pinheiro M, Gastier-Foster JM, Gorlick R, de Toledo SRC, Petrilli AS, Patino-Garcia A, Lecanda F, Gutierrez-Jimeno M, Serra M, Hattinger C, Picci P, Scotlandi K, Flanagan AM, Tirabosco R, Amary MF, Kurucu N, Ilhan IE, Ballinger ML, Thomas DM, Barkauskas DA, Mejia-Baltodano G, Valverde P, Hicks BD, Zhu B, Wang M, Hutchinson AA, Tucker M, Sampson J, Landi MT, Freedman ND, Gapstur S, Carter B, Hoover RN, Chanock SJ, Savage SA. Frequency of Pathogenic Germline Variants in Cancer-Susceptibility Genes in Patients With Osteosarcoma. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(5):724–34. Epub 2020/03/20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0197. National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Dr Pankratz reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savage SA, Mirabello L, Wang Z, Gastier-Foster JM, Gorlick R, Khanna C, Flanagan AM, Tirabosco R, Andrulis IL, Wunder JS, Gokgoz N, Patino-Garcia A, Sierrasesumaga L, Lecanda F, Kurucu N, Ilhan IE, Sari N, Serra M, Hattinger C, Picci P, Spector LG, Barkauskas DA, Marina N, de Toledo SR, Petrilli AS, Amary MF, Halai D, Thomas DM, Douglass C, Meltzer PS, Jacobs K, Chung CC, Berndt SI, Purdue MP, Caporaso NE, Tucker M, Rothman N, Landi MT, Silverman DT, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, Malats N, Kogevinas M, Wacholder S, Troisi R, Helman L, Fraumeni JF Jr., Yeager M, Hoover RN, Chanock SJ. Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for osteosarcoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45(7):799–803. Epub 2013/06/04. doi: 10.1038/ng.2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang C, Hansen HM, Semmes EC, Gonzalez-Maya J, Morimoto L, Wei Q, Eward WC, DeWitt SB, Hurst JH, Metayer C, de Smith AJ, Wiemels JL, Walsh KM. Common genetic variation and risk of osteosarcoma in a multi-ethnic pediatric and adolescent population. Bone. 2020;130:115070. Epub 2019/09/17. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.115070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirabello L, Yu K, Berndt SI, Burdett L, Wang Z, Chowdhury S, Teshome K, Uzoka A, Hutchinson A, Grotmol T, Douglass C, Hayes RB, Hoover RN, Savage SA, National Osteosarcoma Etiology Study G. A comprehensive candidate gene approach identifies genetic variation associated with osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:209. Epub 2011/05/31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musselman JR, Bergemann TL, Ross JA, Sklar C, Silverstein KA, Langer EK, Savage SA, Nagarajan R, Krailo M, Malkin D, Spector LG. Case-parent analysis of variation in pubertal hormone genes and pediatric osteosarcoma: a Children's Oncology Group (COG) study. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2012;3(4):286–93. Epub 2012/12/04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savage SA, Woodson K, Walk E, Modi W, Liao J, Douglass C, Hoover RN, Chanock SJ, National Osteosarcoma Etiology Study G. Analysis of genes critical for growth regulation identifies Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 Receptor variations with possible functional significance as risk factors for osteosarcoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(8):1667–74. Epub 2007/08/09. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Wiemels JL, Hansen HM, Gonzalez-Maya J, Endicott AA, de Smith AJ, Smirnov IV, Witte JS, Morimoto LM, Metayer C, Walsh KM. Two HLA Class II Gene Variants Are Independently Associated with Pediatric Osteosarcoma Risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(10):1151–8. Epub 2018/07/25. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh KM, Whitehead TP, de Smith AJ, Smirnov IV, Park M, Endicott AA, Francis SS, Codd V, Group ECT, Samani NJ, Metayer C, Wiemels JL. Common genetic variants associated with telomere length confer risk for neuroblastoma and other childhood cancers. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37(6):576–82. Epub 2016/05/22. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirabello L, Richards EG, Duong LM, Yu K, Wang Z, Cawthon R, Berndt SI, Burdett L, Chowdhury S, Teshome K, Douglass C, Savage SA, National Osteosarcoma Etiology Study G. Telomere length and variation in telomere biology genes in individuals with osteosarcoma. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2011;2(1):19–29. Epub 2011/05/04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Morimoto LM, de Smith AJ, Hansen HM, Gonzalez-Maya J, Endicott AA, Smirnov IV, Metayer C, Wei Q, Eward WC, Wiemels JL, Walsh KM. Genetic determinants of childhood and adult height associated with osteosarcoma risk. Cancer. 2018;124(18):3742–52. Epub 2018/10/13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gianferante DM, Moore A, Spector LG, Wheeler W, Yang T, Hubbard A, Gorlick R, Patino-Garcia A, Lecanda F, Flanagan AM, Amary F, Andrulis IL, Wunder JS, Thomas DM, Ballinger ML, Serra M, Hattinger C, Demerath E, Johnson W, Birmann BM, De Vivo I, Giles G, Teras LR, Arslan A, Vermeulen R, Sample J, Freedman ND, Huang WY, Chanock SJ, Savage SA, Berndt SI, Mirabello L. Genetically inferred birthweight, height, and puberty timing and risk of osteosarcoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2023:102432. Epub 2023/08/19. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2023.102432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassanain O, Alaa M, Khalifa MK, Kamal N, Albagoury A, El Ghoneimy AM. Genetic variants associated with osteosarcoma risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):3828. Epub 2024/02/16. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-53802-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills LJ, Scott MC, Shah P, Cunanan AR, Deshpande A, Auch B, Curtin B, Beckman KB, Spector LG, Sarver AL, Subramanian S, Richmond TA, Modiano JF. Comparative analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation identifies patterns that associate with conserved transcriptional programs in osteosarcoma. Bone. 2022;158:115716. Epub 2020/11/01. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makielski KM, Mills LJ, Sarver AL, Henson MS, Spector LG, Naik S, Modiano JF. Risk Factors for Development of Canine and Human Osteosarcoma: A Comparative Review. Vet Sci. 2019;6(2). Epub 2019/05/28. doi: 10.3390/vetsci6020048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarver AL, Mills LJ, Makielski KM, Temiz NA, Wang J, Spector LG, Subramanian S, Modiano JF. Distinct mechanisms of PTEN inactivation in dogs and humans highlight convergent molecular events that drive cell division in the pathogenesis of osteosarcoma. Cancer Genet. 2023;276–277:1–11. Epub 2023/06/03. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2023.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartholf DeWitt S, Hoskinson Plumlee S, Brighton HE, Sivaraj D, Martz EJ, Zand M, Kumar V, Sheth MU, Floyd W, Spruance JV, Hawkey N, Varghese S, Ruan J, Kirsch DG, Somarelli JA, Alman B, Eward WC. Loss of ATRX promotes aggressive features of osteosarcoma with increased NF-kappaB signaling and integrin binding. JCI Insight. 2022;7(17). Epub 2022/09/09. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.151583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeBlanc AK, Breen M, Choyke P, Dewhirst M, Fan TM, Gustafson DL, Helman LJ, Kastan MB, Knapp DW, Levin WJ, London C, Mason N, Mazcko C, Olson PN, Page R, Teicher BA, Thamm DH, Trent JM, Vail DM, Khanna C. Perspectives from man's best friend: National Academy of Medicine's Workshop on Comparative Oncology. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(324):324ps5. Epub 2016/02/05. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson EK, Sigurdsson S, Ivansson E, Thomas R, Elvers I, Wright J, Howald C, Tonomura N, Perloski M, Swofford R, Biagi T, Fryc S, Anderson N, Courtay-Cahen C, Youell L, Ricketts SL, Mandlebaum S, Rivera P, von Euler H, Kisseberth WC, London CA, Lander ES, Couto G, Comstock K, Starkey MP, Modiano JF, Breen M, Lindblad-Toh K. Genome-wide analyses implicate 33 loci in heritable dog osteosarcoma, including regulatory variants near CDKN2A/B. Genome Biol. 2013;14(12):R132. Epub 2013/12/18. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-12-r132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.London CA, Gardner H, Zhao S, Knapp DW, Utturkar SM, Duval DL, Chambers MR, Ostrander E, Trent JM, Kuffel G. Leading the pack: Best practices in comparative canine cancer genomics to inform human oncology. Vet Comp Oncol. 2023;21(4):565–77. Epub 2023/10/02. doi: 10.1111/vco.12935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996–1006. Epub 2002/06/05. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. Epub 2015/02/28. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, Delaneau O, Wood AR, Teumer A, Kang HM, Fuchsberger C, Danecek P, Sharp K, Luo Y, Sidore C, Kwong A, Timpson N, Koskinen S, Vrieze S, Scott LJ, Zhang H, Mahajan A, Veldink J, Peters U, Pato C, van Duijn CM, Gillies CE, Gandin I, Mezzavilla M, Gilly A, Cocca M, Traglia M, Angius A, Barrett JC, Boomsma D, Branham K, Breen G, Brummett CM, Busonero F, Campbell H, Chan A, Chen S, Chew E, Collins FS, Corbin LJ, Smith GD, Dedoussis G, Dorr M, Farmaki AE, Ferrucci L, Forer L, Fraser RM, Gabriel S, Levy S, Groop L, Harrison T, Hattersley A, Holmen OL, Hveem K, Kretzler M, Lee JC, McGue M, Meitinger T, Melzer D, Min JL, Mohlke KL, Vincent JB, Nauck M, Nickerson D, Palotie A, Pato M, Pirastu N, McInnis M, Richards JB, Sala C, Salomaa V, Schlessinger D, Schoenherr S, Slagboom PE, Small K, Spector T, Stambolian D, Tuke M, Tuomilehto J, Van den Berg LH, Van Rheenen W, Volker U, Wijmenga C, Toniolo D, Zeggini E, Gasparini P, Sampson MG, Wilson JF, Frayling T, de Bakker PI, Swertz MA, McCarroll S, Kooperberg C, Dekker A, Altshuler D, Willer C, Iacono W, Ripatti S, Soranzo N, Walter K, Swaroop A, Cucca F, Anderson CA, Myers RM, Boehnke M, McCarthy MI, Durbin R, Haplotype Reference C. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1279–83. Epub 2016/08/23. doi: 10.1038/ng.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu JZ, Tozzi F, Waterworth DM, Pillai SG, Muglia P, Middleton L, Berrettini W, Knouff CW, Yuan X, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Preisig M, Wareham NJ, Zhao JH, Loos RJ, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Grundy S, Barter P, Mahley R, Kesaniemi A, McPherson R, Vincent JB, Strauss J, Kennedy JL, Farmer A, McGuffin P, Day R, Matthews K, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lucae S, Ising M, Brueckl T, Horstmann S, Wichmann HE, Rawal R, Dahmen N, Lamina C, Polasek O, Zgaga L, Huffman J, Campbell S, Kooner J, Chambers JC, Burnett MS, Devaney JM, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler L, Lindsay JM, Waksman R, Epstein S, Wilson JF, Wild SH, Campbell H, Vitart V, Reilly MP, Li M, Qu L, Wilensky R, Matthai W, Hakonarson HH, Rader DJ, Franke A, Wittig M, Schafer A, Uda M, Terracciano A, Xiao X, Busonero F, Scheet P, Schlessinger D, St Clair D, Rujescu D, Abecasis GR, Grabe HJ, Teumer A, Volzke H, Petersmann A, John U, Rudan I, Hayward C, Wright AF, Kolcic I, Wright BJ, Thompson JR, Balmforth AJ, Hall AS, Samani NJ, Anderson CA, Ahmad T, Mathew CG, Parkes M, Satsangi J, Caulfield M, Munroe PB, Farrall M, Dominiczak A, Worthington J, Thomson W, Eyre S, Barton A, Wellcome Trust Case Control C, Mooser V, Francks C, Marchini J. Meta-analysis and imputation refines the association of 15q25 with smoking quantity. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):436–40. Epub 2010/04/27. doi: 10.1038/ng.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li MX, Yeung JM, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Evaluating the effective numbers of independent tests and significant p-value thresholds in commercial genotyping arrays and public imputation reference datasets. Hum Genet. 2012;131(5):747–56. Epub 2011/12/07. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, Basu S, Mirabello L, Spector L, Zhang L. A Bayesian Gene-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Analysis of Osteosarcoma Trio Data Using a Hierarchically Structured Prior. Cancer Inform. 2018;17:1176935118775103. Epub 2018/05/31. doi: 10.1177/1176935118775103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howey R, Cordell HJ. PREMIM and EMIM: tools for estimation of maternal, imprinting and interaction effects using multinomial modelling. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:149. Epub 2012/06/29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D930–4. Epub 2011/11/09. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Consortium GT, Laboratory DA, Coordinating Center -Analysis Working G, Statistical Methods groups-Analysis Working G, Enhancing Gg, Fund NIHC, Nih/Nci, Nih/Nhgri, Nih/Nimh, Nih/Nida, Biospecimen Collection Source Site N, Biospecimen Collection Source Site R, Biospecimen Core Resource V, Brain Bank Repository-University of Miami Brain Endowment B, Leidos Biomedical-Project M, Study, Genome Browser Data I, Visualization EBI, Genome Browser Data I, Visualization-Ucsc Genomics Institute UoCSC, Lead a, Laboratory DA, Coordinating C, management NIHp, Biospecimen c, Pathology, e QTLmwg, Battle A, Brown CD, Engelhardt BE, Montgomery SB. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550(7675):204–13. Epub 2017/10/13. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garfield AS, Cowley M, Smith FM, Moorwood K, Stewart-Cox JE, Gilroy K, Baker S, Xia J, Dalley JW, Hurst LD, Wilkinson LS, Isles AR, Ward A. Distinct physiological and behavioural functions for parental alleles of imprinted Grb10. Nature. 2011;469(7331):534–8. Epub 2011/01/29. doi: 10.1038/nature09651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blagitko N, Mergenthaler S, Schulz U, Wollmann HA, Craigen W, Eggermann T, Ropers HH, Kalscheuer VM. Human GRB10 is imprinted and expressed from the paternal and maternal allele in a highly tissue- and isoform-specific fashion. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(11):1587–95. Epub 2000/06/22. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.11.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gagliano Taliun SA, VandeHaar P, Boughton AP, Welch RP, Taliun D, Schmidt EM, Zhou W, Nielsen JB, Willer CJ, Lee S, Fritsche LG, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR. Exploring and visualizing large-scale genetic associations by using PheWeb. Nat Genet. 2020;52(6):550–2. Epub 2020/06/07. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0622-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh KM, de Smith AJ, Hansen HM, Smirnov IV, Gonseth S, Endicott AA, Xiao J, Rice T, Fu CH, McCoy LS, Lachance DH, Eckel-Passow JE, Wiencke JK, Jenkins RB, Wrensch MR, Ma X, Metayer C, Wiemels JL. A Heritable Missense Polymorphism in CDKN2A Confers Strong Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Is Preferentially Selected during Clonal Evolution. Cancer Res. 2015;75(22):4884–94. Epub 2015/11/04. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foss-Skiftesvik J, Li S, Rosenbaum A, Hagen CM, Stoltze UK, Ljungqvist S, Hjalmars U, Schmiegelow K, Morimoto L, de Smith AJ, Mathiasen R, Metayer C, Hougaard D, Melin B, Walsh KM, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Dahlin AM, Wiemels JL. Multi-ancestry genome-wide association study of 4069 children with glioma identifies 9p21.3 risk locus. Neuro Oncol. 2023;25(9):1709–20. Epub 2023/02/23. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noad042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutter NB, Bustamante CD, Chase K, Gray MM, Zhao K, Zhu L, Padhukasahasram B, Karlins E, Davis S, Jones PG, Quignon P, Johnson GS, Parker HG, Fretwell N, Mosher DS, Lawler DF, Satyaraj E, Nordborg M, Lark KG, Wayne RK, Ostrander EA. A single IGF1 allele is a major determinant of small size in dogs. Science. 2007;316(5821):112–5. Epub 2007/04/07. doi: 10.1126/science.1137045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoopes BC, Rimbault M, Liebers D, Ostrander EA, Sutter NB. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) contributes to reduced size in dogs. Mamm Genome. 2012;23(11–12):780–90. Epub 2012/08/21. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9417-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyoshi N, Kuroiwa Y, Kohda T, Shitara H, Yonekawa H, Kawabe T, Hasegawa H, Barton SC, Surani MA, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F. Identification of the Meg1/Grb10 imprinted gene on mouse proximal chromosome 11, a candidate for the Silver-Russell syndrome gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(3):1102–7. Epub 1998/03/14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiura H, Nakamura K, Hikichi T, Hino T, Oda K, Suzuki-Migishima R, Kohda T, Kaneko-ishino T, Ishino F. Paternal deletion of Meg1/Grb10 DMR causes maternalization of the Meg1/Grb10 cluster in mouse proximal Chromosome 11 leading to severe pre- and postnatal growth retardation. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(8):1424–38. Epub 2009/01/29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charalambous M, Smith FM, Bennett WR, Crew TE, Mackenzie F, Ward A. Disruption of the imprinted Grb10 gene leads to disproportionate overgrowth by an Igf2-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8292–7. Epub 2003/06/28. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1532175100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrade AC, Lui JC, Nilsson O. Temporal and spatial expression of a growth-regulated network of imprinted genes in growth plate. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(4):617–23. Epub 2009/11/11. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1339-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monk D, Wakeling EL, Proud V, Hitchins M, Abu-Amero SN, Stanier P, Preece MA, Moore GE. Duplication of 7p11.2-p13, including GRB10, in Silver-Russell syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66(1):36–46. Epub 2000/01/13. doi: 10.1086/302717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Y, Yoon SO, Poulogiannis G, Yang Q, Ma XM, Villen J, Kubica N, Hoffman GR, Cantley LC, Gygi SP, Blenis J. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science. 2011;332(6035):1322–6. Epub 2011/06/11. doi: 10.1126/science.1199484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenfield EM, Collier CD, Getty PJ. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases in Osteosarcoma: 2019 Update. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1258:141–55. Epub 2020/08/09. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-43085-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giovannone B, Lee E, Laviola L, Giorgino F, Cleveland KA, Smith RJ. Two novel proteins that are linked to insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) receptors by the Grb10 adapter and modulate IGF-I signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(34):31564–73. Epub 2003/05/29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frantz JD, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Ottinger EA, Shoelson SE. Human GRB-IRbeta/GRB10. Splice variants of an insulin and growth factor receptor-binding protein with PH and SH2 domains. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(5):2659–67. Epub 1997/01/31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner LM, Fouladi M, Ahmed A, Krailo MD, Weigel B, DuBois SG, Doyle LA, Chen H, Blaney SM. Phase II study of cixutumumab in combination with temsirolimus in pediatric patients and young adults with recurrent or refractory sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(3):440–4. Epub 2014/12/03. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz GK, Tap WD, Qin LX, Livingston MB, Undevia SD, Chmielowski B, Agulnik M, Schuetze SM, Reed DR, Okuno SH, Ludwig JA, Keedy V, Rietschel P, Kraft AS, Adkins D, Van Tine BA, Brockstein B, Yim V, Bitas C, Abdullah A, Antonescu CR, Condy M, Dickson MA, Vasudeva SD, Ho AL, Doyle LA, Chen HX, Maki RG. Cixutumumab and temsirolimus for patients with bone and soft-tissue sarcoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):371–82. Epub 2013/03/13. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiemels JL, Walsh KM, de Smith AJ, Metayer C, Gonseth S, Hansen HM, Francis SS, Ojha J, Smirnov I, Barcellos L, Xiao X, Morimoto L, McKean-Cowdin R, Wang R, Yu H, Hoh J, DeWan AT, Ma X. GWAS in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals novel genetic associations at chromosomes 17q12 and 8q24.21. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):286. Epub 2018/01/20. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang C, Ostrom QT, Hansen HM, Gonzalez-Maya J, Hu D, Ziv E, Morimoto L, de Smith AJ, Muskens IS, Kline CN, Vaksman Z, Hakonarson H, Diskin SJ, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Ramaswamy V, Ali-Osman F, Bondy ML, Taylor MD, Metayer C, Wiemels JL, Walsh KM. European genetic ancestry associated with risk of childhood ependymoma. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(11):1637–46. Epub 2020/07/02. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McDaniel LD, Conkrite KL, Chang X, Capasso M, Vaksman Z, Oldridge DA, Zachariou A, Horn M, Diamond M, Hou C, Iolascon A, Hakonarson H, Rahman N, Devoto M, Diskin SJ. Common variants upstream of MLF1 at 3q25 and within CPZ at 4p16 associated with neuroblastoma. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(5):e1006787. Epub 2017/05/26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Machiela MJ, Grunewald TGP, Surdez D, Reynaud S, Mirabeau O, Karlins E, Rubio RA, Zaidi S, Grossetete-Lalami S, Ballet S, Lapouble E, Laurence V, Michon J, Pierron G, Kovar H, Gaspar N, Kontny U, Gonzalez-Neira A, Picci P, Alonso J, Patino-Garcia A, Corradini N, Berard PM, Freedman ND, Rothman N, Dagnall CL, Burdett L, Jones K, Manning M, Wyatt K, Zhou W, Yeager M, Cox DG, Hoover RN, Khan J, Armstrong GT, Leisenring WM, Bhatia S, Robison LL, Kulozik AE, Kriebel J, Meitinger T, Metzler M, Hartmann W, Strauch K, Kirchner T, Dirksen U, Morton LM, Mirabello L, Tucker MA, Tirode F, Chanock SJ, Delattre O. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple new loci associated with Ewing sarcoma susceptibility. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3184. Epub 2018/08/11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05537-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kong A, Steinthorsdottir V, Masson G, Thorleifsson G, Sulem P, Besenbacher S, Jonasdottir A, Sigurdsson A, Kristinsson KT, Jonasdottir A, Frigge ML, Gylfason A, Olason PI, Gudjonsson SA, Sverrisson S, Stacey SN, Sigurgeirsson B, Benediktsdottir KR, Sigurdsson H, Jonsson T, Benediktsson R, Olafsson JH, Johannsson OT, Hreidarsson AB, Sigurdsson G, Consortium D, Ferguson-Smith AC, Gudbjartsson DF, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Parental origin of sequence variants associated with complex diseases. Nature. 2009;462(7275):868–74. Epub 2009/12/18. doi: 10.1038/nature08625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.