Abstract

Wildlife tagging provides critical insights into animal movement ecology, physiology, and behavior amid global ecosystem changes. However, the stress induced by capture, handling, and tagging can impact post-release locomotion and activity and, consequently, the interpretation of study results. Here, we analyze post-tagging effects on 1585 individuals of 42 terrestrial mammal species using collar-collected GPS and accelerometer data. Species-specific displacements and overall dynamic body acceleration, as a proxy for activity, were assessed over 20 days post-release to quantify disturbance intensity, recovery duration, and speed. Differences were evaluated, considering species-specific traits and the human footprint of the study region. Over 70% of the analyzed species exhibited significant behavioral changes following collaring events. Herbivores traveled farther with variable activity reactions, while omnivores and carnivores were initially less active and mobile. Recovery duration proved brief, with alterations diminishing within 4–7 tracking days for most species. Herbivores, particularly males, showed quicker displacement recovery (4 days) but slower activity recovery (7 days). Individuals in high human footprint areas displayed faster recovery, indicating adaptation to human disturbance. Our findings emphasize the necessity of extending tracking periods beyond 1 week and particular caution in remote study areas or herbivore-focused research, specifically in smaller mammals.

Subject terms: Behavioural ecology, Animal behaviour, Conservation biology

In wildlife tagging, stress from capture and handling can alter post- release behavior and potentially study interpretations. This study of 42 mammal species shows that these effects diminish within 4–7 days, and quicker for animals in high human activity areas indicating adaptation to disturbance.

Introduction

Wildlife movement studies are essential for understanding animal behavioral responses to global environmental changes, sustaining ecosystem functioning, and successful nature conservation1. Animal movements are pivotal in shaping biodiversity patterns and connecting habitats2–4. Comprehending the far-reaching anthropogenic influence on movements is therefore paramount to effective land use planning and conservation strategies5. In wildlife research, GPS telemetry is increasingly applied to study animal movement ecology6,7. Current devices track individual movements at unprecedented levels of spatial and temporal precision. Beyond high-resolution motion tracking, modern technology allows for a variety of sensors to be attached to animals, pushing animal tracking into the realm of Big Data7–9 and providing researchers with information not only of animals’ whereabouts but also offering insights into for example their activity patterns, derived from accelerometers10. Such sensors measure static and dynamic acceleration, representing animal movement in three dimensions11 and allowing for the quantification of activity or proxies thereof12–15. One well-established proxy is the overall dynamic body acceleration (ODBA), which estimates activity-related energy expenditure of free-ranging animals16,17.

While tracking devices have enabled researchers to collect invaluable data on animal movements and behavior18 and have yielded considerable scientific and conservation benefits5,19, concerns have been raised about potential adverse effects of these devices on study animals20–23. Deploying telemetry sensors on animals involves capturing, handling, and releasing the focal individual24,25. The effects of physical capture, chemical immobilization, and restraint of animals on possible post-release behavioral modifications are, however, understudied in wildlife species, which may affect the welfare of animals and the interpretation of study results (but see: refs. 26–28). The capture and handling process involves several stress-inducing and physically demanding events that are attributable to human presence and may involve sudden or loud noises, social isolation, limited movement, and impaired vision29–31. The use of neurologically active chemicals can affect animal behavior and movement for several days25,32, ultimately triggering behavioral changes33–35. These behavioral changes can negatively affect home range formation and activity patterns26, body condition32,36,37, and even reproductive success and survival38,39.

In long-term deployments of GPS tracking devices over several months or years, omitting data from the initial days post-capture is common to reduce the chances of biased results driven by capture effects. However, this assumes that animals will have adapted to the attached sensor after this period. Yet, a lack of data exists on the response and recovery of animals to capture and how it varies among species. In contrast, for short-term deployments of several days (e.g., bats or flying foxes), the effects of stress from the collaring process on animal behavior and activity, in addition to the physical impairment effects due to the tag weight40, may result in biased findings with animals having insufficient time to recover. Considerable strides have been made in reducing stress during capture and improving the weight and comfort of devices35. However, effectively evaluating and minimizing adverse collaring impacts remain complex tasks that demand increased research attention41. A few studies have examined the effects of collar deployment procedures and tags on animal behavior (see, e.g., refs. 42,43), but general ethical guidelines for acceptable practices regarding attached devices remain unresolved44. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of protocols for handling data during the initial tracking days due to uncertainty surrounding the duration over which animal-borne tracking devices impair individuals. Compounding this challenge is the difficulty in determining and evaluating ’normal’ behavior22, with only a limited number of case studies attempting this. In captive scimitar-horned oryx Oryx dammah, Stabach et al.43 showed elevated stress hormone levels for up to 5 days and behavioral changes (e.g., increased headshaking) for up to 3 days in collared individuals. Van de Bunte45 found that collared red pandas Ailurus fulgens in captivity reduced daily activity levels and food intake compared to non-collared individuals. In free-ranging red deer Cervus elaphus, Becciolini et al.46 found increased movement rates and avoidance of their center of activity for up to 10 days, likely reflecting recovery from effects of the deployment procedure. In Eurasian beavers Castor fiber, the body mass of dominant individuals decreased considerably with repeated capture events47. American black bears Ursus americanus tended to avoid human presence after capture events48. Similarly, roe deer Capreolus capreolus reduced activity and were displaced towards woodland to avoid human disturbance. These behavioral changes decreased during the first 10 days, with females being less sensitive than males26.

The effects of capture (e.g., helicopter darting or capture, chasing, trapping) on animal behavior can vary widely across species, sex, tag size, and type, deployment duration, the specific deployment procedure, or the environment22,26,44,49. Species differ in stress responses, especially throughout the initial days of tracking, and the time taken to return to their normal behavior31,37. Notably, animals living in anthropogenic landscapes adapt their space use and become more tolerant to human disturbances50,51. As such, the effects of deployment procedures likely differ between individuals who are behaviorally adapted to different levels of human proximity. In a meta-analysis, Samia et al.52 found populations habituated to human stressors to be more tolerant towards human disturbance. Consequently, since movement53 and behavior54,55 change with human proximity, we expect altered responses to capture and immobilization. In this study, we aggregated high-resolution GPS tracking and acceleration (ACC) data from 42 terrestrial mammal species over time from capture to quantify the magnitude and duration of collaring impacts on movement activity. We developed three measures to quantify disturbance effects based on individual movement characteristics and activity (Fig. 1). First, we quantified disturbance intensity to assess changes in daily displacement and activity (measured as ACC/ODBA) by calculating the sum of deviations for each of the initial ten tracking days from the subsequent 10-day average. Second, we calculated recovery speed, reflecting an individual’s adaptability during the first 10 days, using the slope of the disturbance intensity curve on day one. Third, we calculated recovery duration using the time when each individual returned to their long-term average for each behavioral metric. Even though anesthesia dosage is calculated per kilogram, we assume that larger mammals experience a more pronounced disturbance, as they often require longer durations of anesthesia24 and face more substantial physiological challenges during immobilization such as hyperthermia56 compared to smaller mammals. This prolonged exposure can lead to more significant physiological and behavioral disruptions. In contrast, owing to their higher energy requirements relative to their body size, smaller mammals need to be consistently more active.

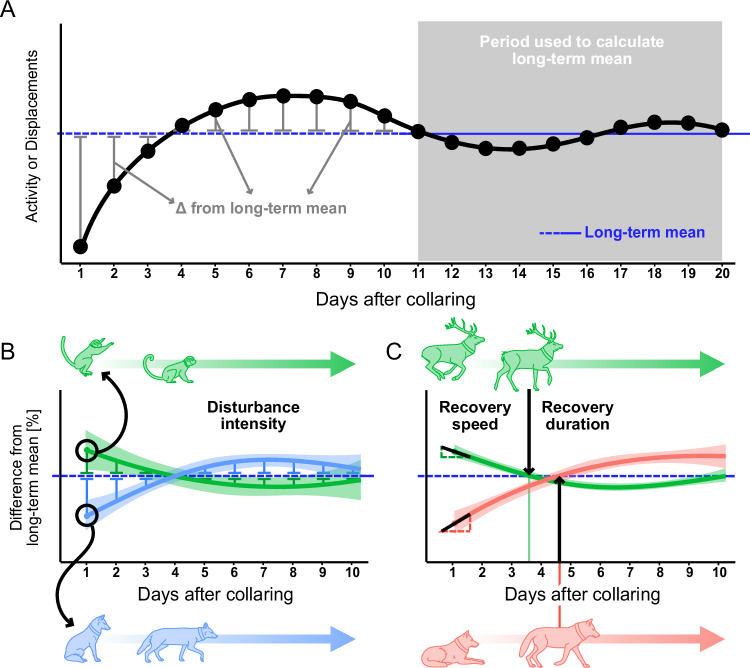

Fig. 1. Methods calculating the disturbance intensity, recovery speed and duration with specific examples.

A Illustrates the difference of daily activity (ODBA) and displacements (days 1–10) from the long-term means (days 11–20). First, we calculated daily (days 1–10) activity (ODBA) and displacements. Subsequently, we related derived values to the long-term mean (days 11–20). The analysis was conducted identically for activity and displacements. B To calculate the disturbance intensity, we related daily averaged values (displacement, activity) to the respective mean during days 11–20. The upper example illustrates the disturbance intensity of Propithecus verreauxi, with increased displacements on the first days, before converging towards the long-term mean; the lower illustrates the disturbance intensity in activity of Canis aureus, with decreased activity during the initial days of tracking. C Recovery speed was calculated as the ∣slope∣ on day one post-release, and recovery duration was determined as the time when animals reverted to their long-term mean for the first time post-release. The upper example illustrates the recovery speed and duration in activity of Cervus elaphus, the lower one of Canis lupus.

Capturing and tagging animals acts as a manipulative experiment, enabling us to investigate how animals respond to such disturbances. Beyond data exclusion considerations, such studies allow for the exploration of various hypotheses related to patterns in the behavioral responses of animals. We hypothesize that responses to capture are not only species-specific but may also encompass broader patterns driven by distinct traits. Due to their reproductive roles, we expect females to exhibit heightened sensitivity and more gradual recovery. We also assumed that dietary requirements are reflected in the responses, as herbivores may be more flexible in finding forage, allowing them to find shelter to recover. In contrast, carnivores need to roam continuously for survival and are evolutionary less adapted to being hunted, potentially making them more susceptible to prolonged impairment. By comprehensively examining this aspect, we expect the diet to influence the duration and intensity of an individual’s impairment. Furthermore, we were particularly interested in whether animals in remote areas with fewer anthropogenic influences recover slower because individuals are less adapted to human disturbances.

In this work, we quantified the overall disturbance impact of capture across terrestrial mammal species, including assessing the time required for recovery and identifying periods most affected, which could bias the interpretation of results if not adequately accounted for. More than 70% of the species analyzed showed behavioral changes following collaring events. Herbivores traveled larger distances, while omnivores and carnivores were less active and mobile during the initial days post-release. Recovery duration proved brief, with alterations diminishing within 4−7 tracking days for most species, with individuals in high human footprint areas displaying faster recovery, indicating adaptation to human disturbance.

Results

Disturbance intensity

Among the 42 terrestrial mammal species analyzed, 30 were sensitive to the collaring procedure and significantly changed their activity or displacement behavior during the first 10 days after release (Fig. 2, Table 1, Figs. S1–S30). In total, we found that 25 of 41 species increased or decreased their activity, and 19 out of 40 species changed their displacements during the first 10 days of tracking (Fig. 2, Table 1). While within-species variability was high ( and ), sex did not significantly influence species-specific reaction behavior ( and ). On the first day of tracking, individuals were, on average, less active compared to their long-term mean (−7.8 ± 19.2%; mean ± SD), whereas daily displacements were higher (6.9 ± 23.8%; mean ± SD), with large SD attributed to strong intra- and interspecific variability. Net deviations, i.e., absolute deviations on the first day, were 14.2 ± 15% for activity and 18.7 ± 16.3% for displacements. The activity level of 25 species differed substantially immediately after release compared to subsequent days, with a gradual stabilization during the initial days (Table 2). This trend was particularly evident in omnivores (R2 = 0.374, Dev. explained = 46.4%). While omnivores and carnivores were less active during the initial days, pooled herbivore data revealed both increased and decreased activity rates. A similar pattern was found for displacements, as most species traveled longer distances after collaring events compared to the long-term mean (days 11–20; R2 = 0.25, Dev. explained = 37.7).

Fig. 2. Disturbance intensity: Impacts of collaring on activity and displacements during the initial 10 days post-release.

Daily differences to the long-term mean of activity (upper) and displacements (lower) split by diet: herbivores (left), omnivores (middle), and carnivores (right) for 42 mammal species, n = 1585. All species with p ≤ 0.05 are shown as solid lines and species with p > 0.05 or n < 5 as dotted lines. Activity: R2 = 0.374, Dev. explained = 46.4%, displacements: R2 = 0.25, Dev. explained = 37.6%. Predictions are derived from two Generalized Additive Mixed Models with Gamma error distributions to assess the effect of disturbance intensity on activity and displacements of the focal species over time. The dotted blue line represents the long-term mean (average for days 11−20). In the legend following each species name, the first number refers to the number of individuals for activity and the second for displacements.

Table 1.

Species model summary: Disturbance intensity in activity and displacements

| Study species | Activity | Displacements | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Common Name | edf | ref.df | Statistic | p-value | edf | ref.df | Statistic | p-value |

| Acinonyx jubatus | Cheetah | 1.160 | 1.294 | 3.799 | 0.058 | ||||

| Alces alces | Moose | 1.993 | 2.000 | 190.955 | <0.001 | 1.994 | 2.000 | 76.011 | <0.001 |

| Antidorcas marsupialis | Springbok | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.333 | 0.248 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.176 | 0.675 |

| Bison bison | American Bison | 1.000 | 1.000 | 11.711 | 0.001 | ||||

| Bison bonasus | European Bison | 1.859 | 1.980 | 6.700 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 6.856 | 0.009 |

| Canis aureus | Golden Jackal | 1.904 | 1.991 | 14.369 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.441 | 0.507 |

| Canis latrans | Coyote | 1.940 | 1.996 | 25.793 | <0.001 | ||||

| Canis lupus | Gray Wolf | 1.894 | 1.989 | 37.056 | <0.001 | 1.684 | 1.900 | 12.894 | <0.001 |

| Capra ibex | Alpine Ibex | 1.936 | 1.996 | 92.773 | <0.001 | 1.664 | 1.887 | 1.924 | 0.098 |

| Capreolus capreolus | Roe Deer | 1.996 | 2.000 | 150.162 | <0.001 | 1.996 | 2.000 | 30.008 | <0.001 |

| Cervus elaphus | Red Deer | 1.942 | 1.997 | 31.220 | <0.001 | 1.961 | 1.999 | 16.210 | <0.001 |

| Chlorocebus pygerythrus | Vervet Monkey | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.302 | 0.583 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.082 | 0.775 |

| Crocuta crocuta | Spotted Hyena | 1.875 | 1.984 | 4.426 | 0.014 | 1.387 | 1.625 | 9.713 | <0.001 |

| Cryptoprocta ferox | Fossa | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.335 | 0.563 | 1.886 | 1.987 | 8.911 | <0.001 |

| Equus hemionus | Mongolian Khulan | 1.000 | 1.000 | 5.465 | 0.019 | 1.925 | 1.994 | 30.232 | <0.001 |

| Erinaceus europaeus | European Hedgehog | 1.891 | 1.988 | 5.816 | 0.004 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.983 |

| Eulemur rufifrons | Red-fronted Lemur | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.061 | 0.805 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.059 | 0.809 |

| Felis chaus | Jungle Cat | 1.812 | 1.965 | 14.060 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 8.527 | 0.004 |

| Felis silvestris | Wildcat | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.337 | 0.248 | 1.754 | 1.939 | 1.323 | 0.262 |

| Gazella subgutturosa | Goitered Gazelle | 1.280 | 1.481 | 9.762 | <0.001 | 1.669 | 1.891 | 1.114 | 0.256 |

| Genetta genetta | Common Genet | 1.809 | 1.964 | 15.326 | <0.001 | 1.448 | 1.695 | 2.954 | 0.130 |

| Ichneumia albicauda | White-tailed Mongoose | 1.919 | 1.993 | 14.329 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.277 | 0.259 |

| Lepus europaeus | European Hare | 1.195 | 1.352 | 18.290 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 6.623 | 0.010 |

| Lynx lynx | Eurasian Lynx | 1.811 | 1.964 | 20.903 | <0.001 | 1.694 | 1.907 | 4.823 | 0.025 |

| Lynx rufus | Bobcat | 1.313 | 1.528 | 7.565 | 0.006 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.439 | 0.508 |

| Madoqua guentheri | Günther’s dik-dik | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.165 | 0.281 | 1.289 | 1.495 | 0.347 | 0.766 |

| Odocoileus virginianus | White-tailed Deer | 1.000 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.993 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 18.475 | <0.001 |

| Ovibos moschatus | Muskox | 1.000 | 1.000 | 4.636 | 0.031 | 1.205 | 1.369 | 1.557 | 0.283 |

| Panthera leo | African Lion | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.889 | 0.169 | 1.010 | 1.020 | 0.028 | 0.886 |

| Panthera pardus | Leopard | 1.758 | 1.941 | 8.783 | 0.001 | 1.685 | 1.901 | 5.692 | 0.013 |

| Papio anubis | Olive Baboon | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.178 | 0.673 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.666 | 0.415 |

| Procyon lotor | Raccoon | 1.266 | 1.461 | 2.380 | 0.168 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.802 | 0.180 |

| Propithecus verreauxi | Verreaux’s Sifaka | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.099 | 0.753 | 1.718 | 1.921 | 4.117 | 0.041 |

| Puma concolor | Cougar | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.971 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.255 | 0.133 |

| Sus scrofa | Wild Boar | 1.867 | 1.982 | 418.661 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 53.265 | <0.001 |

| Tragelaphus oryx | Gemsbok | 1.760 | 1.943 | 1.990 | 0.166 | 1.861 | 1.981 | 7.511 | 0.001 |

| Tragelaphus strepsiceros | Greater Kudu | 1.096 | 1.183 | 0.438 | 0.483 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.373 | 0.541 |

| Ursus americanus | American Black Bear | 1.928 | 1.995 | 76.150 | <0.001 | 1.826 | 1.970 | 13.861 | <0.001 |

| Ursus arctos | Brown Bear | 1.552 | 1.799 | 2.919 | 0.121 | 1.529 | 1.778 | 3.161 | 0.104 |

| Viverra tangalunga | African Civet | 1.563 | 1.809 | 12.381 | <0.001 | 1.369 | 1.602 | 5.142 | 0.026 |

| Vulpes bengalensis | Bengal Fox | 1.811 | 1.964 | 6.690 | 0.004 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.501 | 0.479 |

| Vulpes vulpes | Red Fox | 1.650 | 1.878 | 6.532 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.367 | 0.242 |

| s(ID) | 1248 | 1451 | 6.584 | <0.001 | 1063 | 1261 | 4.589 | <0.001 | |

| s(sex) | 0.140 | 1.000 | 1.159 | 0.312 | 0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.472 | |

| R-sq. (adj) | 0.374 | 0.250 | |||||||

| Deviance explained | 46.4% | 37.7% | |||||||

| n | 1452 | 1262 | |||||||

The presented results include values for estimated degrees of freedom (edf) and reference degrees of freedom (ref.df), where edf represents the effective degrees of freedom resulting from the fitted model, indicating model flexibility, while ref.df serves as a baseline measure for comparison. (see methods, Eq. (1)).

Table 2.

Duration until return to mean long-term behavior (mean values ± standard deviation)

| Dietary type | Mean days (ACC) | Mean days (GPS) |

|---|---|---|

| Herbivore | 6.59 ± 0.86 | 3.60 ± 1.00 |

| Omnivore | 5.50 ± 0.63 | 5.63 ± 0.49 |

| Carnivore | 5.09 ± 0.88 | 5.44 ± 0.50 |

Displacements were calculated based on localizations (GPS) and activity based on accelerometer data (ACC).

On the first day post-release, moose (Alces alces) exhibited the largest increases in displacement distance, moving 63% further compared to the long-term mean, followed by common eland Tragelaphus oryx (52%), and spotted hyena Crocuta crocuta (44%). In contrast, leopards Panthera pardus were found to have the largest reductions in displacement distances, reducing their movement distances by-65%, followed by wolves Canis lupus (−44%), and Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx (−43%). Moose also had the largest increases in activity on day one (44%), followed by red deer Cervus elaphus (26%), and Mongolian khulan Equus hemionus hemionus (9%). Wolves had the largest decreases in activity on day one (−48%), followed by the white-tailed mongoose Ichneumia albicauda (−41%), and leopard Panthera pardus and golden jackal Canis aureus (−41%). In general, carnivores traveled shorter distances post-release, aside from the spotted hyena (Deviance day1GPS = 44%) and fossa Cryptoprocta ferox (Deviance day1GPS = 12%). In this study, we did not investigate mortality rates as only individuals that survived for at least 20 days post-tagging were included in our analysis.

Recovery speed and duration

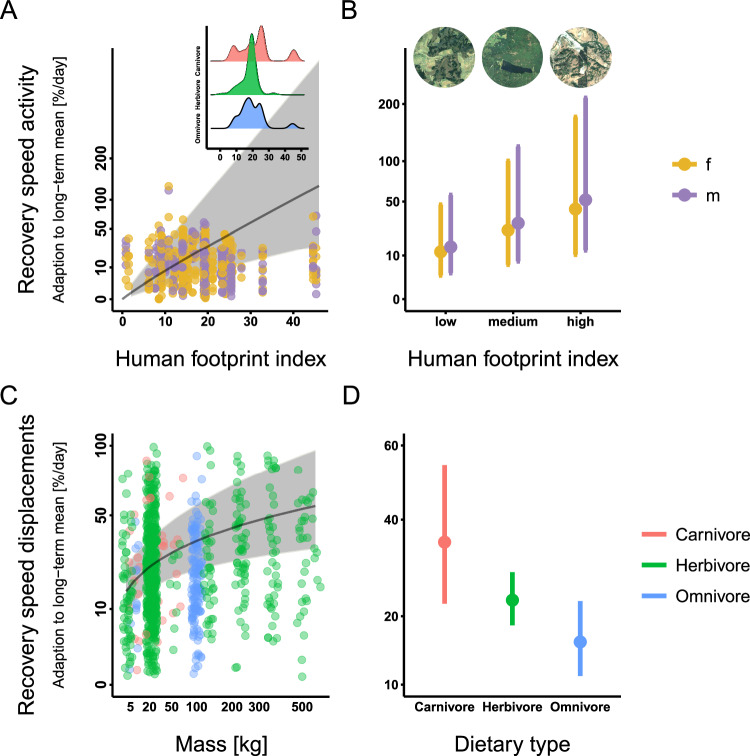

Recovery speed in activity is best explained by a high human footprint index of the respective study site, the individuals’ sex [+male] (Fig. 3AB, Table 3) and a larger body mass (competing model, ΔAIC < 2, Tab. S2). A fast recovery in displacements was best explained by the species-specific diet [+carnivore] and its body mass, with large species recovering considerably faster (Fig. 3CD, Table 4). During the first 10 days of tracking, the difference from the long-term mean of displacements decreased from 33 ± 17% on day 1 to 21 ± 20% on day 10, while activity decreased from 24 ± 14%–12 ± 6%; devianceday1 vs. devianceday10 for all species with p ≤ 0.05, Fig. 3, Table 1. Comparing individual days in days 11–20 to the mean of this period indicated mean routine variations of 14% for activity and 35% for displacements.

Fig. 3. Recovery speed described in relation to dietary type, an individual’s sex, and the human Footprint index of the study area.

A, B Recovery speed (of activity) described in relation to sex and the Human Footprint index (HFi), n = 1241. High recovery speed values indicate a fast recovery. High HFi values indicate a strong anthropogenic influence, and low values indicate a high degree of remoteness. The inset (A) shows the density plots of the sample size distribution for each dietary guild in regard to HFi. B Predictions are presented for values of the lower (12.37), median (18.68), and upper (25) quartiles of HFi. Insets here (B) present exemplary satellite imagery of sites with differing HFi; left to right: an area with little infrastructure and some habitat fragmentation [HFi: 10]; agricultural fields with small forest patches, road infrastructure, and some settlements [HFi: 17]; a more degraded landscape with a quarry and an adjacent solar park [HFi: 25] (ⓒLandsat / Copernicus, GoogleEarth 2020-202388). Landscapes with extreme HFi values (close to zero: representing pristine, undisturbed areas; close to 50: representing dense populated urban areas) were less present in the dataset and, as such, examples are not shown. C, D Recovery speed (of displacements) described in relation to body mass (C) and dietary type (D), n = 1014. Recovery speed describes the speed of change in activity or displacements as a percentage of the respective long-term mean on day one. Dots (A, C) represent calculated values. Dots (B, D) and the solid lines (A, C) represent mean modeled values, and bars (B, D) as well as the gray shaded area (A, C) are 95% confidence intervals. Note that the y-axis is sqrt-transformed.

Table 3.

Recovery speed of activity

| Recovery speed activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | −5.51 | −10.08 – −0.94 | 0.018 |

| mass | 0.31 | −0.13 – 0.75 | 0.172 |

| sex [m] | 0.19 | 0.02 – 0.36 | 0.025 |

| diet [herbivore] | 0.60 | −1.25 – 2.45 | 0.527 |

| diet [omnivore] | −0.34 | −1.96 – 1.29 | 0.685 |

| HFi | 1.83 | 1.40 – 2.25 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | |||

| σ2 | 2.02 | ||

| τ00 study species | 2.53 | ||

| ICC | 0.56 | ||

| N study species | 25 | ||

| Observations | 1241 | ||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.111 / 0.605 | ||

The best-fit model to describe recovery speed in terms of activity spent included the species’ body mass, sex, dietary type, and the study site’s Human Footprint Index (HFi) as independent variables. Study species was implemented as a random effect (see methods, Eq. (2)).

Table 4.

Recovery speed of displacements

| Recovery speed displacements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 0.70 | −0.47 – 1.86 | 0.240 |

| diet [herbivore] | −0.42 | −0.91 – 0.07 | 0.092 |

| diet [omnivore] | −0.78 | −1.35 – −0.23 | 0.006 |

| mass | 0.25 | 0.14 – 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | |||

| σ2 | 1.31 | ||

| τ00 study species | 0.06 | ||

| ICC | 0.05 | ||

| N study species | 17 | ||

| Observations | 1014 | ||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.065 / 0.107 | ||

The best-fit model to describe recovery speed in terms of displacements included dietary type and the species’ body mass as independent variables. Study species was implemented as a random effect (see methods, Eq. (2)).

Recovery duration also differed between dietary types. Omnivores and carnivores returned to their mean long-term behavior in both disturbance intensity measures after 5–6 days (Table 2), with data beyond this period being less influenced by collaring events. In contrast, herbivores were the quickest to return to their mean long-term displacement behavior but were slowest to return to their long-term activity levels: 3.6 ± 1.0 days (displacements), and 6.6 ± 0.9 days (activity), mean ± SD).

Discussion

Our findings revealed widespread evidence of post-collaring behavioral changes in animal activity and displacements. Animals displayed a general trend in their responses, marked by the most pronounced deviations in behavior immediately following successful collar deployment. Subsequently, their behavior stabilized, converging on their long-term mean within four to 7 days (Tab. 2). This recovery duration represents the initial period of more pronounced data bias. Responses found in our dataset are consistent with the findings of case studies from the respective species: In moose A. alces, the observed reaction is in accordance with Neumann et al.57, who identified larger spatial displacements for up to 4.5 days after capture. In wild boars Sus scrofa, similar to our findings, the first post-capture days were characterized by low activity and low mobility levels, which then gradually restored to stable levels at approximately 10 days28. Additionally, we observed increased movement rates for red deer immediately after release, as found by Becciolini et al.46. We can not make any conclusions about the effect of tagging on survival rates, as only data from individuals that survived the study period were considered.

Males recovered on average 1.3 days faster than females from collaring-induced changes in activity, aligning with findings in roe deer26, yet this effect was not detected in displacements. Females may require a longer recovery time due to gestation, birth, and rearing of offspring (as only 5–10% of mammalian species engage in paternal care58). These factors may aggravate negative impacts associated with the attachment of tracking devices, potentially leading to increased stress levels, reduced foraging efficiency, or, as a consequence, compromised reproductive success26–28. We expect this effect to be even more pronounced in pregnant or lactating females. However, due to the heterogeneous nature of the dataset, with various species captured over different times across continents, we did not account for an individual’s physiological or behavioral season.

Omnivores and carnivores were generally less active than herbivores after release. In cases where animals are caught with bait, as is sometimes done for carnivores and omnivores, individuals may not need to carry out foraging movements in the following days as they would under normal circumstances. A more proximate explanation for the reduced movement and activity could also be a reaction to chemical immobilization. In contrast, 65% of the herbivores increased their activity on the first day post-release. Resting to conserve energy does not seem like a legitimate reaction to being chased and immobilized because their natural response to being chased by predators is escaping by moving. The recovery speed of activity and displacements after collaring events was slower in herbivores than omnivores and carnivores. From an evolutionary perspective, this is surprising since predators frequently chase many wild herbivores, and therefore, herbivores may be expected to be better adapted to and recover faster from disturbances. Yet, these responses may be offset by the potent anesthesia used, particularly for large herbivores (e.g., Bison sp., A. alces, Tragelaphus strepsiceros, C. elaphus). For all species, we found strong intraspecific variation in the response behavior, which may be context-specific or linked to animal personalities59, traditionally assessed along a bold-shy continuum60,61.

Stress-related activity of wildlife is often categorized as either fight or flight62. This can also hold true for the post-capture response of wildlife to either the capture event or the collar. Characterization of fight-flight was first identified in human psychology63, but as Bracha et al.64 noted, the addition of “freeze” to the term is needed. In wildlife, this can be extended to include hiding in response to disturbance65. Post-release behavior likely includes a complex blend of all these responses, as well as additional stressors they encounter during that timeframe. To add to this complexity, in places with significant anthropogenic influence, animals frequently display enhanced tolerance and adaptation to human presence50,51. Animals that adapt to human presence may experience reduced competition for resources compared to natural habitats66.

Management practices, such as supplementary feeding, which can cause habituation and changes in space use, mobility, or activity (e.g., ref. 67), may also influence behavior after collaring. Furthermore, some species demonstrate behavioral flexibility and can adjust their activity patterns or habitat preferences68 and their movement behavior69 to avoid direct conflicts with humans. For example, some mammals, such as raccoons Procyon lotor and coyotes Canis latrans, thrive in urban areas by utilizing human-associated food resources and adapting their behavior to coexist with humans50,51, yet, the impact of anthropogenic influence is species-specific70. Previous studies have shown that human interactions can strongly influence animal behavior. For example, the coexistence of humans and wildlife in urban areas often selects individuals with bold personalities71–73. On the other hand, animals inhabiting remote areas have less exposure to human presence and, consequently, encounters. Hence, when such animals encounter humans, they might show an exacerbated response toward the disturbance and remain alert for a prolonged time. While this assertion is speculative, it is supported by our finding here, where individuals in remote areas recovered slower from collaring than those in highly anthropogenically influenced areas. With numerous deployment methods like helicopter darting, chasing, or trapping being applied in the field, analyzing their effect was not feasible within the scope of this study. The effect of the deployment method remains unclear, and the selected method may even change along an HFI gradient. For example, helicopter darting may be the only option in areas with little infrastructure, whereas in more urban areas, alternative options are preferred. Interpreting the effect of the human footprint should take into account that deployment type could be influenced by the respective study area. Therefore, we strongly recommend documenting these methodological decisions for future research.

There exists a fine balance between obtaining valuable data and ensuring the well-being of tracked animals. Researchers must consider these ethical dilemmas carefully and implement tracking methods that minimize harm and maximize animal welfare. Omitting initial data can contribute to reducing biased results, thereby generating more accurate outcomes that could better inform conservation efforts. Yet, it may be difficult to detect the effects of collars during short-term deployments, as the data obtained is highly time-constrained. While our study was confined to assessing behavioral alterations associated with collaring events, it is important to note that even short-term modifications in behavior can incur energetic costs, reduce energy intake, or influence predation risk and, as such, potentially impact animal survival and fitness74–76. As we only considered data from individuals that survived for at least 20 days post-tagging, we could not account for possible mortality rates. The inclusion of such data in future studies could contribute to an even more holistic understanding of the consequences of tagging.

While established animal welfare guidelines and regulatory requirements that allow for such invasive studies exist, many of these rely on findings from isolated case studies. Our study of post-release telemetry data of 42 terrestrial mammalian species reveals potential biases in wildlife GPS and ACC data during the initial days of animal tracking, likely due to invasive immobilization and tagging procedures, which may influence movement ecology findings. These impacts, however, fade within a relatively short time frame of four to 7 days, suggesting that the overall impact of collaring is minimal and short-lived, which is good news for animal tracking science. In studies where longer tracking is not feasible, researchers should be aware of these disturbance biases. Particularly, short-term studies, lasting <7 days, may be significantly compromised. These studies are prevalent in certain research areas, for example, where battery weight strongly limits tracking duration. Based on our findings, we strongly advocate extending animal tracking periods well beyond 7 days whenever possible. Further efforts relating the findings of this study to other important variables such as method of capture, type of tag, drug combinations, and post-release behavior could provide valuable insights into best practices in reducing capture myopathy, stress, and data bias. By understanding and addressing these limitations, researchers can maximize GPS-collaring advantages while limiting adverse effects on study animals. Undoubtedly, animal tracking will continue to contribute to our understanding of the environment, with progress in this field being propelled by ongoing technological developments, improved techniques, and heightened ethical considerations.

Methods

Data collection and preparation

Animal tracking data (GPS and ACC, see Supplementary Note 1 for permits) from multiple data providers were either directly sourced from tables or downloaded from the Movebank data repository77 with the help of the R package Move78. In the first step, we omitted individuals with missing data during the initial 20 days, resulting in 1585 unique individuals. We defined data as missing if any discontinuation resulted in <1 GPS fix per hour and less than one activity measurement per 30 min. The resulting number of individuals per terrestrial mammal species ranged from 4 to 672 (mean nacc = 36.4, mean ngps = 32.6) out of total individuals nacc = 1452 of 41 species across 57 study sites, and total individuals ngps = 1262 of 40 species across 55 study sites.

We classified the data into two periods: the initial 10 days following the individual’s release and days 11–20. We considered the latter timeframe representative of ’long-term’ behavior, expecting that the response to the collaring/handling process had subsided within the initial 10 days, as shown in previous studies (e.g., A. alces ≤ 4.5 days57, C. capreolus ≤ 10 days26, C. elaphus ≤ 10 days46).

We calculated mean daily ODBA values for each individual with the R package moveACC79 as ODBA = ∣Ax∣ + ∣Ay∣ + ∣Az∣ for tri-axial measurements; and as ODBA = ∣Ax∣ + ∣Ay∣ for bi-axial measurements, where Ax, Ay, and Az are the derived dynamic accelerations corresponding to the three perpendicular axes of the sensor13. Downsampling from three to two axes to compare ACC measurements was not necessary, as the raw data were used per individual to calculate the disturbance intensity, which is then expressed in percent. Acceleration records obtained from individuals with only one axis (Acinonyx jubatus) were not considered. The temporal resolution of both GPS and ACC data was adjusted by rounding timestamps to the nearest 5 min interval. Then, displacements were calculated using the R package adehabitatLT80 as each individual’s mean displacement (m) from one GPS fix to the next within each 24 h interval. For each study site, we extracted the Human Footprint index (HFi:81,82) and calculated the mean HFi for a 5 km radius around the center of the study site (mean longitude, mean latitude).

Disturbance intensity

Subsequently, we related daily averaged values (displacement, activity) to the respective mean during days 11–20 to calculate the disturbance intensity (Fig. 1). We applied two Generalized Additive Mixed Models with Gamma error distributions for the disturbance intensity in activity and displacements to estimate the effect on the focal species in combination with time (i.e., days 1–10) on daily differences to the long-term mean using the R package mgcv83. Since we did not expect a linear relationship, we specified the predictor variable time as a smooth term for each species and a first-order auto-regressive correlation structure corAR1 among the residuals of the model associated with each individual. Sex was included as a random smoothing effect, allowing for a smooth relationship between sex and the dependent variable. This allows for individual-specific effects of sex on the response, which can be useful when assuming that the relationship between sex and the response is not strictly linear but varies smoothly across individuals or species. The disturbance intensity model was specified as follows:

| 1 |

Thus, the linear predictor ηid,t includes an autoregressive process of order one (AR[1]). Here, the parameter ρ accounts for the temporal autocorrelation, id represents the animal identifier, and t is the corresponding time point. In addition, u indicates the use of random intercepts. Deviance was calculated and modeled separately for both activity and displacement.

Recovery speed and duration

For all individuals of species with significant disturbance effects (Fig. 2, Table 1), we calculated the ∣slope∣ on day one after the release as a measure of recovery speed, i.e., how fast individuals adapt throughout the first days. The slope was calculated for each individual as the first derivative for x = 1 from the ID-specific fitted curve with y ~ log(x). Recovery speed, expressed in units of percentage per day, quantifies the rate of adaptation of individuals. The steeper the slope (i.e., the higher the values), the faster individuals were at adapting or acclimating. We applied separate linear mixed effect models for activity and displacement to estimate the recovery speed in both activity and displacements, using the R package lme484 using the respective measurements, ∣slope day 1∣ as the dependent variable. We included sex, dietary type (herbivore, omnivore, carnivore), body mass derived from literature values85 (Table S1), and the Human Footprint index of the study area as independent variables and study species as a random effect. Due to incomplete data and many different levels, we did not consider the deployment procedure as an independent variable. The dependent variable, as well as the independent variables, body mass and HFi, were log-transformed. The model was calculated using Gaussian error distribution and a natural logarithm link function. Subsequently, we selected models using the R package MuMIn86. By ranking model combinations via the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), we considered all independent variables in the best-fit models within 2 AIC units in the final model and report the respective summary. Models were calculated using all gap-less data available for the independent and dependent variables, resulting in minor variations in sample size and species analyzed for activity and displacements.

To assess the stabilization period of collaring effects on activity and displacement, we used the fitted disturbance intensity model (Eq. 1) to calculate the period until individuals reverted to their average long-term behavior for both disturbance intensity measures (activity and displacements) for the first time post-release. For this, we included all individuals of species in which significant patterns were identified with the disturbance intensity model above.

The recovery speed model was specified as a linear mixed effect model:

| 2 |

where sex and diet were specified as categorical variables; slopeday1 was calculated and modeled separately for activity and displacement.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful for the support of Karatina University, Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, and Mpala Research Centre; the staff of Polish and Slovak Tatra National Parks for their help in bear trapping; all Carpathian Brown Bear Project members who assisted in the field during captures, handling and data collection; Zbigniew Krasinski from the Białowieza National Park and Tomasz Kaminski from the Mammal Research Institute PAS for help in European bison collaring; the BioMove RTG including associated helpers in the field, the workers at the ZALF research station; the Forest and Wildlife Research Center at Mississippi State University; the members of Euromammals including Eurodeer, Euroboar, and Euroreddeer; Junta de Castilla y Leon, Gobierno Principado Asturias, Ministerio Transicion Ecologica, Tragsatec; the Oyu Tolgoi’s Core Biodiversity Monitoring Program, implemented by the WCS through a cooperative agreement with Sustainability East Asia LLC for their help in Khulan capture, marking and radiotracking; N. Sharma, G. Basson, D. Medeiros, J. McGraw, R. Reed, A. Johnston, H. Maschmeyer, R. King, B. Nichols, J. Suraci, for essential support in animal tracking; D. Simpson, S. Ekwanga, M. Mutinda, G. Omondi, W. Longor, M. Iwata, A. Surmat, M. Snider, W. Fox, and K. VanderWaal for field assistance, M. Crofoot, D. Rubenstein, and L. Frank for sharing their field equipment, and M. Kinnaird and T. Young for logistical support; L. Purchart, M. Kutal, J. Krojerová, and K. Purchartová for scientific background and project coordination and P. Forejtek for veterinarian support; the Danau Girang Field Centre research group in collaboration with the Sabah Wildlife Department, Veterinarian support provided by Drs. M. Gonzalez, S. Guerrero-Sanchez, D. Ramirez, L. Benedict, and P. Nagalingam; field assistants and personnel at Zackenberg Research Station; the Office Français de la Biodiversité, especially Jean-Luc Hamann and Vivien Siat and the Office National des Forets, including the wildlife technicians, the foresters, and the many volunteers for their help in the capture of red and roe deer; field collaborators and veterinarians of the Leibniz-IZW, Berlin, especially Janina Radwainski; the Namibian Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, the Namibian farmers, and the entire team of the Cheetah Research Project of the Leibniz-IZW, Berlin; K. Boyer, S. Peper, C. Wilson, Z. Johnson, H. Greenburg, K. Haydett, D. Warren, D. Payne, J. Hoffman, M. Proctor, J. Gaskamp for assistance with trapping wild pigs and white-tailed deer in Oklahoma; the University of California, Santa Cruz and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife for their partnership in the Santa Cruz Puma project; and all non-mentioned technicians, and workers in the field. This work was supported by the DFG-funded research training group “BioMove" (DFG-GRK 2118/1); by a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology (DBI-1402456) awarded to Adam W. Ferguson and Paul W. Webala; the Polish-Norwegian Research program administered by the National Research Centre for Research and Development in Poland (POL-NOR/198352/85/2013), Tatra National Park own funding; by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research BMBF within the Collaborative Project “Bridging in Biodiversity Science-BIBS" (grant number: 01LC1501); by the Polish Ministry of Sciences and Information Technology (grant no 2P04F 011 26); Frankfurt Zoological Society − Help for Threatened Wildlife and the EU LIFE program (project no LIFE06 NAT/PL/000105); by the DFG: KA 1082/17-1; by the DFG: KA 1082/16-1; by Safari Club International Foundation, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, and the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act under Pittman-Robertson project W-147-R; by grant QK1910462 and CZ021010.00.0160190000803; by Ministerio de la Transicion Ecologica; by the Peninsula Open Space Trust, Land Trust of Santa Cruz County, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Santa Clara Open Space Authority; by the National Geographic Society Committee for Research and Exploration #9385-13; by the Washington University in Saint Louis ICARES grant 2015; by the Dean’s office of the Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno and Training Forest Enterprise Masaryk Forest Kr^tiny; by Houston Zoo; the Sime Darby Foundation; Ocean Park Conservation Foundation Hong Kong (TM01.1718); and Phoenix Zoo; by the ‘Mov-It’ Agence Nationale de la Recherche grant ANR-16-CE02-0010-02 to NM; by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany, FKZ: 01LL1804A; by the Office Français de la Biodiversité (OFB); by the “Stiftung Naturschutz Berlin"; by the Noble Research Institute, LLC; by 15. Juni Fonden and Copenhagen Zoo; by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (PRIN 2010-2011, 20108 TZKHC, 418 J81J12000790001); by the Foreste Casentinesi National Park; by the Regione Autonoma della Sardegna, Provincia di Sassari, and Fondazione Banco di Sardegna; by the National Science Foundation; by the Messerli Foundation Switzerland; CS was supported by the Elsa-Neumann foundation; by the US National Science Foundation (grant nos. BCS 99-03949, BCS 1266389), the Leakey Foundation, and the Committee on Research, University of California, Davis to Lynne A. Isbell, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation (grant no. 8386) to Laura R. Bidner; by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), NAB. PGSD3-404001-2011; by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), WMG. GM83863, and the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Author contributions

Niels Blaum & Jonas Stiegler developed the idea; Marlee Tucker & Francesca Cagnacci facilitated data collection, Robert Hering helped analyze the data; Thomas Müller, Marlee Tucker, Niels Blaum, and Jonas Stiegler conducted initial manuscript structuring, internal revision, and outline; Cara A. Gallagher designed the conceptual figure and strongly contributed to revising the manuscript; Nancy Barker, Anne Berger, Niels Blaum, Francesca Cagnacci, Meaghan N. Evans, Cara A. Gallagher, Morgan Hauptfleisch, Robert Hering, Robert Hering, Marco Heurich, Lynne A. Isbell, Stephanie Kramer-Schadt, Thomas Müller, Krzysztof Schmidt, Nuria Selva, Laurel E.K. Serieys, Agnieszka Sergiel, Marlee Tucker, Bettina Wachter, Stephen Webb, Christopher C. Wilmers, Tomasz Zwijacz-Kozica commented on the manuscript. The main persons responsible for providing the data are Nancy A. Barker (C. crocuta, P. leo), Floris M. van Beest (O. moschatus), Jerrold L. Belant (C. latrans, C. lupus, U. americanus), Anne Berger (C. capreolus, E. europaeus), Stephen Blake (B. bison), Niels Blaum (A. marsupialis, L. europaeus, T. oryx, T. strepsiceros), Francesca Brivio (S. scrofa), Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar (G. subgutturosa), Francesca Cagnacci (C. capreolus, C. elaphus, C. ibex, L. lynx, S. scrofa), Meaghan N. Evans (V. tangalunga), Adam W. Ferguson (G. genetta, I. albicauda), Claudia Fichtel (C. ferox, E. rufifrons, P. verreauxi), Adam T. Ford (M. guentheri), Wayne M. Getz (C. crocuta, P. leo), Stefano Grignolio (C. ibex), Morgan Hauptfleisch (A. marsupialis, T. oryx, T. strepsiceros), Robert Hering (A. marsupialis, T. oryx, T. strepsiceros), Marco Heurich (C. elaphus), Lynne A. Isbell (C. pygerythrus, P. pardus, P.anubis), René Janssen (F. silvestris), Petra Kaczensky (E. hemionus), Sophia Kimmig (V. vulpes), Rafał Kowalczyk (B. bonasus), Stephanie Kramer-Schadt (P. lotor, V. vulpes), Mia-Lana Lührs (C. ferox), Jörg Melzheimer (A. jubatus), Nicolas Morellet (C. capreolus), Manuel Roeleke (P. lotor), Christer M. Rolandsen (A. alces), Sonia Saïd (C. capreolus), Niels M. Schmidt (O. moschatus), Nuria Selva (U. arctos), Laurel E. K. Serieys (L. rufus), Rob Slotow (P. leo), Jonas Stiegler (L. europaeus), Garrett M. Street (O. virginianus, S. scrofa), Wiebke Ullmann (L. europaeus), Abi T. Vanak (C. aureus, F. chaus, V. bengalensis), Bettina Wachter (A. jubatus), Stephen L. Webb (O. virginianus, S. scrofa), Christopher C. Wilmers (P. concolor). All other co-authors contributed to data collection and approved the final manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mark Boyce and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study to create the respective figures have been provided in the Source Data file. The GPS and acceleration datasets used and analyzed in this study are available in the Movebank Data Repository77 at www.movebank.org (Antidorcas marsupialis, ID: 904829042; Chlorocebus pygerythrus, ID: 17629305; Erinaceus europaeus, ID: 354843286; ID: 348067475; ID: 490547558; ID: 1371906275; Felis silvestris, ID: 40386102; Genetta genetta, ID: 19814565; Ichneumia albicauda, ID: 158898881; Lepus europaeus, ID: 918554628; ID: 1138520346; ID: 4048590; ID: 25727477; ID: 43360515; ID: 71038468; ID: 73514179; Lynx rufus, ID: 501787846; ID: 475878514; Panthera pardus, ID: 17629305; Papio anubis, ID: 17629305; Procyon lotor, ID: 4048590; Taurotragus oryx, ID: 904829042; Tragelaphus strepsiceros, ID: 904829042; Viverra tangalunga, ID: 57540673; Vulpes vulpes, ID: 4048590; ID: 326682415; ID: 173932849); data from Euromammals87 can be accessed by logging into their website or via a contact form at https://euromammals.org/ (Capra ibex; Capreolus capreolus; Cervus elaphus; Lynx lynx; Sus scrofa); or can be obtained from data providers upon request through the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-52381-8.

References

- 1.Hebblewhite, M. & Haydon, D. T. Distinguishing technology from biology: a critical review of the use of GPS telemetry data in ecology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.365, 2303–2312 (2010). 10.1098/rstb.2010.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan, R. et al. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA105, 19052–19059 (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0800375105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeltsch, F. et al. Integrating movement ecology with biodiversity research—exploring new avenues to address spatiotemporal biodiversity dynamics. Mov. Ecol.1, 6 (2013). 10.1186/2051-3933-1-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlägel, U. E. et al. Movement-mediated community assembly and coexistence. Biol. Rev.95, 1073–1096 (2020). 10.1111/brv.12600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen, A. M. & Singh, N. J. Linking movement ecology with wildlife management and conservation. Front. Ecol. Evol.3, 155 (2016).

- 6.Handcock, R. et al. Monitoring animal behaviour and environmental interactions using wireless sensor networks, GPS collars and satellite remote sensing. Sensors9, 3586–3603 (2009). 10.3390/s90503586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kays, R., Crofoot, M. C., Jetz, W. & Wikelski, M. Terrestrial animal tracking as an eye on life and planet. Science348, 6340 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Jetz, W., Tertitski, G., Kays, R., Mueller, U. & Wikelski, M. Biological earth observation with animal sensors. Trend. Ecol. Evol.37, 719–724 (2022). 10.1016/j.tree.2022.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nathan, R. et al. Big-data approaches lead to an increased understanding of the ecology of animal movement. Science375, eabg1780 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wilmers, C. C. et al. The golden age of bio-logging: how animal-borne sensors are advancing the frontiers of ecology. Ecology96, 1741–1753 (2015). 10.1890/14-1401.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughey, L. F., Hein, A. M., Strandburg-Peshkin, A. & Jensen, F. H. Challenges and solutions for studying collective animal behaviour in the wild. Philos.Trans. R Soc. B Biol. Sci.373, 20170005 (2018). 10.1098/rstb.2017.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson, R. P. et al. Estimates for energy expenditure in free-living animals using acceleration proxies: a reappraisal. J. Animal Ecol.89, 161–172 (2020). 10.1111/1365-2656.13040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qasem, L. et al. Tri-axial dynamic acceleration as a proxy for animal energy expenditure; should we be summing values or calculating the vector? PLoS ONE7, e31187 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0031187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martín López, L. M., Miller, P. J. O., Aguilar de Soto, N. & Johnson, M. Gait switches in deep-diving beaked whales: biomechanical strategies for long-duration dives. J. Exp. Biol.218, 1325–1338 (2015). 10.1242/jeb.106013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunner, R. M. et al. A new direction for differentiating animal activity based on measuring angular velocity about the yaw axis. Ecol. Evol.10, 7872–7886 (2020). 10.1002/ece3.6515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson, R. P. et al. Moving towards acceleration for estimates of activity-specific metabolic rate in free-living animals: the case of the cormorant. J. Animal Ecol.75, 1081–1090 (2006). 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gleiss, A. C., Wilson, R. P. & Shepard, E. L. C. Making overall dynamic body acceleration work: on the theory of acceleration as a proxy for energy expenditure. Methods Ecol. Evol.2, 23–33 (2011). 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00057.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooke, S. J. et al. Biotelemetry: a mechanistic approach to ecology. Trend Ecol. Evol.19, 334–343 (2004). 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGowan, J. et al. Integrating research using animal-borne telemetry with the needs of conservation management. J. Appl. Ecol.54, 423–429 (2017). 10.1111/1365-2664.12755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godfrey, J. & Bryant, D. Effects of radio transmitters: review of recent radio-tracking studies. In Conservation Applications of Mmeasuring Energy Expenditure of New Zealand Birds: Assessing Habitat Quality and Costs of Carrying Radio Transmitters. (ed. Williams, M.) 83–95 (Department of Conservation, 2003).

- 21.Mech, D. L. & Barber, S. M. A Critique of Wildlife Radio-Tracking and Its Use in National Parks: a Report to the National Park Service, US Geological Survey.https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/93895 (2002).

- 22.Ropert-Coudert, Y. & Wilson, R. Subjectivity in bio-logging science: do logged data mislead? Mem. Nat. Inst. Polar Res.58, 23–33 (2004).

- 23.Healy, M., Chiaradia, A., Kirkwood, R. & Dann, P. Balance: a neglected factor when attaching external devices to penguins. Memoirs Nat. Inst. Polar Res.Special Issue, 179–182 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell, R. A. & Proulx, G. Trapping and marking terrestrial mammals for research: integrating ethics, performance criteria, techniques, and common sense. ILAR J.44, 259–276 (2003). 10.1093/ilar.44.4.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iossa, G., Soulsbury, C. & Harris, S. Mammal trapping: a review of animal welfare standards of killing and restraining traps. Animal Welfare16, 335–352 (2007). 10.1017/S0962728600027159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morellet, N. et al. The effect of capture on ranging behaviour and activity of the European Roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Wildlife Biol.15, 278–287 (2009). 10.2981/08-084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Northrup, J. M., Anderson, C. R. & Wittemyer, G. Effects of helicopter capture and handling on movement behavior of mule deer. J. Wildlife Manag.78, 731–738 (2014). 10.1002/jwmg.705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brogi, R. et al. Capture effects in wild boar: a multifaceted behavioural investigation. Wildlife Biol.2019, 1–10 (2019).

- 29.Theil, P. K., Coutant, A. E. & Olesen, C. R. Seasonal changes and activity-dependent variation in heart rate of Roe deer. J. Mammal.85, 245–253 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grandin, T. & Shivley, C. How farm animals react and perceive stressful situations such as handling, restraint, and transport. Animals5, 1233–1251 (2015). 10.3390/ani5040409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergvall, U. A. et al. Settle down! ranging behaviour responses of Roe deer to different capture and release methods. Animals11, 3299 (2021). 10.3390/ani11113299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cattet, M., Boulanger, J., Stenhouse, G., Powell, R. A. & Reynolds-Hogland, M. J. An evaluation of long-term capture effects in ursids: implications for wildlife welfare and research. J. Mammal.89, 973–990 (2008). 10.1644/08-MAMM-A-095.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alibhai, S. K., Jewell, Z. C. & Towindo, S. S. Effects of immobilization on fertility in female black rhino (Diceros bicornis). J. Zool.253, 333–345 (2001). 10.1017/S0952836901000309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harcourt, R. G., Turner, E., Hall, A., Waas, J. R. & Hindell, M. Effects of capture stress on free-ranging, reproductively active male Weddell seals. J. Comp. Physiol. A196, 147–154 (2010). 10.1007/s00359-009-0501-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salvo, A. D. Chemical and physical restraint of African wild animals. J. Wildlife Dis.58, 951–953 (2022).

- 36.Pelletier, F., Hogg, J. T. & Festa-Bianchet, M. Effect of chemical immobilization on social status of bighorn rams. Animal Behav.67, 1163–1165 (2004). 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brivio, F., Grignolio, S., Sica, N., Cerise, S. & Bassano, B. Assessing the impact of capture on wild animals: the case study of chemical immobilisation on Alpine ibex. PLoS ONE10, e0130957 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0130957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnemo, J. M. et al. Risk of capture-related mortality in large free-ranging mammals: experiences from Scandinavia. Wildlife Biol.12, 109–113 (2006). 10.2981/0909-6396(2006)12[109:ROCMIL]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacques, C. N. et al. Evaluating ungulate mortality associated with helicopter net-gun captures in the Northern great plains. J. Wildlife Manag.73, 1282–1291 (2009). 10.2193/2009-039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson, R. P. et al. Animal lifestyle affects acceptable mass limits for attached tags. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.288, 20212005 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.McIntyre, T. Animal telemetry: tagging effects. Science349, 596–597 (2015). 10.1126/science.349.6248.596-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooks, C., Bonyongo, C. & Harris, S. Effects of global positioning system collar weight on zebra behavior and location error. J. Wildlife Manag.72, 527–534 (2008). 10.2193/2007-061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stabach, J. A. et al. Short-term effects of GPS collars on the activity, behavior, and adrenal response of scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah). PLoS ONE15, e0221843 (2020). 10.1371/journal.pone.0221843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson, R. P. & McMahon, C. R. Measuring devices on wild animals: what constitutes acceptable practice? Front. Ecol. Environ.4, 147–154 (2006). 10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0147:MDOWAW]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van de Bunte, W., Weerman, J. & Hof, A. R. Potential effects of GPS collars on the behaviour of two red pandas (Ailurus fulgens) in Rotterdam Zoo. PLoS ONE16, e0252456 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pone.0252456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becciolini, V., Lanini, F. & Ponzetta, M. P. Impact of capture and chemical immobilization on the spatial behaviour of red deer Cervus elaphus hinds. Wildlife Biol.2019, wlb.00499 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mortensen, R. M. & Rosell, F. Long-term capture and handling effects on body condition, reproduction and survival in a semi-aquatic mammal. Sci. Rep.10, 17886 (2020). 10.1038/s41598-020-74933-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chi, D., Chester, D., Ranger, W. & Gilbert, B. Effects of capture procedures on black bear activity at an Alaskan Salmon stream. Ursus10, 563–569 (1998).

- 49.Hawkins, P. Bio-logging and animal welfare: practical refinements. Mem. Natl Inst. Polar Res. Spec. Issue58, 58–68 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gehrt, S. D., Anchor, C. & White, L. A. Home range and landscape use of coyotes in a metropolitan landscape: conflict or coexistence? J. Mammal.90, 1045–1057 (2009). 10.1644/08-MAMM-A-277.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prange, S., Gehrt, S. D. & Wiggers, E. P. Influences of anthropogenic resources on Raccoon (Procyon lotor) movements and spatial distribution. J. Mammal.85, 483–490 (2004). 10.1644/BOS-121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samia, D. S. M., Nakagawa, S., Nomura, F., Rangel, T. F. & Blumstein, D. T. Increased tolerance to humans among disturbed wildlife. Nat. Commun.6, 8877 (2015). 10.1038/ncomms9877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tucker, M. A. et al. Moving in the anthropocene: global reductions in terrestrial mammalian movements. Science359, 466–469 (2018). 10.1126/science.aam9712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ciuti, S. et al. Effects of humans on behaviour of wildlife exceed those of natural predators in a landscape of fear. PLoS ONE7, e50611 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0050611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaynor, K. M., Hojnowski, C. E., Carter, N. H. & Brashares, J. S. The influence of human disturbance on wildlife nocturnality. Science360, 1232–1235 (2018). 10.1126/science.aar7121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chinnadurai, S. K., Strahl-Heldreth, D., Fiorello, C. V. & Harms, C. A. Best-practice guidelines for field-based surgery and anesthesia of free-ranging wildlife. I. Anesthesia and analgesia. J. Wildlife Dis.52, S14–S27 (2016). 10.7589/52.2S.S14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neumann, W., Ericsson, G., Dettki, H. & Arnemo, J. M. Effect of immobilizations on the activity and space use of female moose (Alces alces). Can. J. Zool.89, 1013–1018 (2011). 10.1139/z11-076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodroffe, R. & Vincent, A. Mother’s little helpers: patterns of male care in mammals. Trend. Ecol. Evol.9, 294–297 (1994). 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90033-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roche, D. G., Careau, V. & Binning, S. A. Demystifying animal ‘personality’ (or not): why individual variation matters to experimental biologists. J. Exp. Biol.219, 3832–3843 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Sloan Wilson, D., Clark, A. B., Coleman, K. & Dearstyne, T. Shyness and boldness in humans and other animals. Trend. Ecol. Evol.9, 442–446 (1994). 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90134-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schirmer, A., Herde, A., Eccard, J. A. & Dammhahn, M. Individuals in space: personality-dependent space use, movement and microhabitat use facilitate individual spatial niche specialization. Oecologia189, 647–660 (2019). 10.1007/s00442-019-04365-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lingle, S. & Pellis, S. Fight or flight? antipredator behavior and the escalation of coyote encounters with deer. Oecologia131, 154–164 (2002). 10.1007/s00442-001-0858-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quick, J. C. & Spielberger, C. D. Walter Bradford Cannon: pioneer of stress research. Int. J. Stress Manag.1, 141–143 (1994). 10.1007/BF01857607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bracha, S. H. Freeze, flight, fight, fright, faint: adaptationist perspectives on the acute stress response spectrum. CNS Spectr.9, 679–685 (2004). 10.1017/S1092852900001954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tablado, Z. & Jenni, L. Determinants of uncertainty in wildlife responses to human disturbance. Biol. Rev.92, 216–233 (2017). 10.1111/brv.12224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Santini, L. et al. One strategy does not fit all: determinants of urban adaptation in mammals. Ecol. Lett.22, 365–376 (2019). 10.1111/ele.13199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Milner, J. M., Van Beest, F. M., Schmidt, K. T., Brook, R. K. & Storaas, T. To feed or not to feed? evidence of the intended and unintended effects of feeding wild ungulates. J. Wildlife Manag.78, 1322–1334 (2014). 10.1002/jwmg.798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alberti, M. et al. Global urban signatures of phenotypic change in animal and plant populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.114, 8951–8956 (2017). 10.1073/pnas.1606034114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tucker, M. A. et al. Behavioral responses of terrestrial mammals to COVID-19 lockdowns. Science380, 1059–1064 (2023). 10.1126/science.abo6499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Erb, P. L., McShea, W. J. & Guralnick, R. P. Anthropogenic influences on macro-level mammal occupancy in the Appalachian trail corridor. PLoS ONE7, e42574 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0042574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tuomainen, U. & Candolin, U. Behavioural responses to human-induced environmental change. Biol. Rev.86, 640–657 (2011). 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gaynor, K. M. et al. An applied ecology of fear framework: linking theory to conservation practice. Animal Conserv.24, 308–321 (2021). 10.1111/acv.12629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martínez-Abraín, A., Quevedo, M. & Serrano, D. Translocation in relict shy-selected animal populations: program success versus prevention of wildlife-human conflict. Biol. Conserv.268, 109519 (2022). 10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gallagher, C. A., Grimm, V., Kyhn, L. A., Kinze, C. C. & Nabe-Nielsen, J. Movement and seasonal energetics mediate vulnerability to disturbance in marine mammal populations. Am. Nat.197, 296–311 (2021). 10.1086/712798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nabe-Nielsen, J. et al. Predicting the impacts of anthropogenic disturbances on marine populations. Conserv. Lett.11, e12563 (2018).

- 76.Pirotta, E. et al. Understanding the population consequences of disturbance. Ecol. Evol.8, 9934–9946 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Wikelski, M., Davidson, S. C. & Kays, R. The Movebank Data Repository.www.movebank.org (2020).

- 78.Kranstauber, B., Smolla, M. & Scharf, A. Move: Visualizing and Analyzing Animal Track Data. https://cran.r-project.org/package=move (2020).

- 79.Scharf, A. moveACC: Visualitation and Analysis of Acceleration Data (Mainly for eObs Tags).https://gitlab.com/anneks/moveACC/ (2018).

- 80.Calenge, C. The package “adehabitat” for the R software: A tool for the analysis of space and habitat use by animals. Ecol. Model.197, 516–519 (2006). 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.03.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McGowan, P. J. K. Mapping the terrestrial human footprint. Nature537, 172–173 (2016). 10.1038/537172a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Venter, O. et al. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat. Commun.7, 12558 (2016). 10.1038/ncomms12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models 2nd edn, Vol. 496 (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2017).

- 84.Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw.67, 1–48 (2015).

- 85.Faurby, S. et al. PHYLACINE 1.2: the phylogenetic Atlas of mammal macroecology. Ecology99, 2626–2626 (2018). 10.1002/ecy.2443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barton, K. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R Package Version 1.15.6.https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MuMIn/MuMIn.pdf (2016).

- 87.Urbano, F. & Cagnacci, F. Data management and sharing for collaborative science: lessons learnt from the euromammals iInitiative. Front. Ecol. Evol.9, 727023 (2021).

- 88.Gorelick, N. et al. Google earth engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27 (2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in this study to create the respective figures have been provided in the Source Data file. The GPS and acceleration datasets used and analyzed in this study are available in the Movebank Data Repository77 at www.movebank.org (Antidorcas marsupialis, ID: 904829042; Chlorocebus pygerythrus, ID: 17629305; Erinaceus europaeus, ID: 354843286; ID: 348067475; ID: 490547558; ID: 1371906275; Felis silvestris, ID: 40386102; Genetta genetta, ID: 19814565; Ichneumia albicauda, ID: 158898881; Lepus europaeus, ID: 918554628; ID: 1138520346; ID: 4048590; ID: 25727477; ID: 43360515; ID: 71038468; ID: 73514179; Lynx rufus, ID: 501787846; ID: 475878514; Panthera pardus, ID: 17629305; Papio anubis, ID: 17629305; Procyon lotor, ID: 4048590; Taurotragus oryx, ID: 904829042; Tragelaphus strepsiceros, ID: 904829042; Viverra tangalunga, ID: 57540673; Vulpes vulpes, ID: 4048590; ID: 326682415; ID: 173932849); data from Euromammals87 can be accessed by logging into their website or via a contact form at https://euromammals.org/ (Capra ibex; Capreolus capreolus; Cervus elaphus; Lynx lynx; Sus scrofa); or can be obtained from data providers upon request through the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.