Abstract

With expansion of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy and broader utilization of anti-cytokine directed therapeutics for toxicity mitigation, the routine assessment of cytokines may enhance understanding of toxicity profiles, guide therapeutic interventions, and facilitate cross-trial comparisons. As specific cytokine elevations can correlate with and provide insights into CAR T cell toxicity, mitigation strategies, and response, we explored the reporting of cytokine detection methods and assessed for the correlation of cytokines to cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) across clinical trials. In this analysis, we reviewed 21 clinical trials across 60 manuscripts that featured a US Food and Drug Administration-approved CAR T cell construct or one of its predecessors. We highlight substantial variability and limited reporting of cytokine measurement platforms and panels used across CAR T cell clinical trials. Specifically, across 60 publications, 28 (46.7%) did not report any cytokine data, representing 6 of 21 (28.6%) clinical trials. In the 15 trials reporting cytokine data, at least 4 different platforms were used. Furthermore, correlation of cytokines with ICANS, CRS, and CRS severity was limited. Considering the fundamental role of cytokines in CAR T cell toxicity, our manuscript supports the need to establish standardization of cytokine measurements as a key biomarker essential to improving outcomes of CAR T cell therapy.

Keywords: T cells, chimeric antigen, biomarker, immunotherapy, adoptive, CAR T cell, cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, standardization

Graphical abstract

Given the importance of cytokines in informing the safe administration of CAR T cells, Biery and colleagues systematically evaluate the reporting of cytokine profiling and associations with toxicity. They demonstrate that standardization of assessment and utilization of this critical biomarker is lacking, laying a foundation for a need for standardization.

Introduction

While chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy has had astounding success against hematologic malignancies, the concurrent utilization of anti-cytokine directed therapies to overcome cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), and other serious cytokine-mediated toxicities has been essential. Although real-time cytokine monitoring is rarely performed, as we learned from the very first child who received CAR T cells and experienced severe refractory CRS, the detection of elevated interleukin (IL)-6 directly informed the utilization of tocilizumab, which both saved her life and established the integration of tocilizumab for treatment of CRS.1 Similarly, elevations in interferon (IFN)γ and IL-1 have supported using emapalumab2 or anakinra, respectively, in patients experiencing severe toxicities.3 As CAR T cells are used more extensively, predicting response, toxicity onset, severity, and fine-tuning toxicity mitigation strategies with the use of additional anti-cytokine directed therapies has become imperative. Since cytokine profiles can characterize in vivo immunological activation and correlate with CRS and ICANS,4,5,6,7,8 the ability to compare cytokine profiles across clinical trials and different CAR T cell constructs could reveal important toxicity patterns.

While cytokine profiling has generally been an exploratory correlative, which cytokines are assessed, how these are analyzed, and if and when they are reported remain uncertain. Furthermore, several non-interchangeable platforms to analyze cytokines exist and vary in methodology (e.g., antibody-based immunofluorescence, antibody-based chemiluminescence, combined antibody and PCR, etc.), panels used (e.g., single versus multiplex), and lower limit of detection. Given the importance of cytokine profiling as a biomarker of CAR T cell activity, we sought to explore the heterogeneity of cytokine detection methods and the correlation of cytokines to CRS and ICANS across clinical trials. In doing so, we aim to provide insights that support a need to standardize approaches to cytokine profiling and analysis.

Results

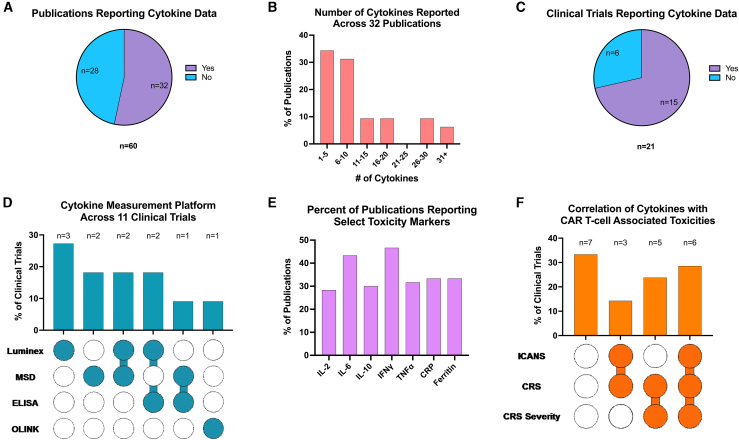

Of the 60 publications analyzed, 28 (46.7%) did not report any cytokine data (Figure 1A). Across the 32 publications that reported cytokine measurements, 21 (65.6%) reported ≤10 cytokines (Figure 1B). Collectively, 15 of 21 (71.4%) clinical trials reported on cytokine data (Figure 1C). Across these 15 trials, 11 (73.3%) documented the cytokine measurement platform utilized, which encompassed a total of 4 unique assays (Table 1). Luminex (fluorescence) was most common, used solely in 3 (27.3%) and in combination with other platforms in 4 (36.4%) clinical trials. Meso Scale Discovery (electrochemiluminescence) was the second most used platform, being the sole platform in 2 (18.2%) and used in combination with other platforms in 3 (27.3%) trials (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Variability in cytokine measurement and reporting across CAR T cell studies

(A) Across all 60 publications assessed, the portion that did or did not report cytokine data. (B) For the 32 publications with cytokine data, the number of cytokines reported in the publication is indicated. (C) When considering the data of each publication from a given clinical trial, the percentage of clinical trials (n = 21) reporting cytokine data. (D) The cytokine measurement platform reported in the clinical trials (n = 11) when available. (E) The percentage of publications (n = 60) evaluating toxicity markers. (F) The percentage of clinical trials (n = 21) correlating cytokine levels to ICANS, CRS, and CRS severity. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; MSD, Meso Scale Discovery; OLINK, Olink immuno-oncology cytokine panel.

Table 1.

Laboratory platforms for cytokine measurements reported

| ELISA | Electrically activated chemiluminescence, bead-based multiplexing | Proximity extension assay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | antibody-based immunofluorescence | Antibody based chemiluminescence | Combined antibody and PCR |

| Sample volume (μL) | ∼50–100 | ∼25 | 1 |

| Proteins measured | 1 at a time | 4, 10, 30, 48 | >3,000 |

| Hands-on time | high | lower | lower |

| Time to data | hours | hours | 1–2 days |

| Dynamic range | 1–2 logs | 3–4 log+ | 5 log+ |

| Output | absolute value | absolute value | relative value |

| Examples | many | MSD, Luminex | Olink |

| Advantages | sensitive, rapid, high throughput | multiplexing, linear range | multiplexing, sensitive and specific, high throughput, low sample volume |

| Limitations | sample preparation, false positives, time intensive | specialized instrumentation | validated with serum and plasma samples |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; MSD: Meso Scale Discovery.

Across cytokines, IL-6 and IFNγ were the most frequently reported on, albeit still in the minority of publications, being reported in just 26 (43.3%) and 28 (46.7%) of the 60 publications, respectively (Figure 1E). In comparison, tumor necrosis factor α and IL-15 were each reported in 19 (31.7%), and IL-2 was reported in 17 (28.3%). The routinely available biomarkers C-reactive protein (CRP) and ferritin were each reported in 20 (33.3%) publications. There was substantial variability in the frequency (e.g., timepoints) at which cytokines were measured. Additionally, information on when cytokines labs were collected was inconsistent and often indeterminable, with some reporting data for as many as 16 time points within the first 31 days post-infusion of CAR T cells and others reporting as few as 1 timepoint—often the peak cytokine value.

Given the importance of cytokines in predicting toxicities such as ICANS, CRS, and CRS severity, we investigated manuscript inclusion of these correlations. Across the 21 trials, 11 (52.4%) did not report these correlations in the primary publication. While reporting increased in follow-up publications, 7 (33.3%) still lacked these data. Collectively, 6 (28.6%) trials reported some correlation of cytokine levels to ICANS, CRS, and CRS severity, 5 (23.8%) trials reported correlations to CRS and CRS severity, and 9 (42.86%) provided correlations of cytokine levels to ICANS (Figure 1F).

Discussion

Simultaneous with the very first approval of CAR T cells in the United States, tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, had its indicated use expanded to include the “treatment of severe or life-threatening CAR T cell induced CRS.”9 Following its initial use in severe CRS, tocilizumab is now first line for CRS, and its use as a prophylactic and/or pre-emptive agent is evolving.10 More recently, efforts targeting the IL-1 pathway with anakinra, an IL-1 receptor antagonist, have shown promise in further optimizing the safety profile.11 Similarly, utilization of IFNγ targeting with emapalumab for refractory CRS12,13 or broader cytokine blockade with ruxolitinib9 is increasing.

Considering the growing list of anti-cytokine targeted therapies being utilized in the treatment of CAR T cell-associated toxicities, the importance of cytokine profiling in informing the safe administration of CAR T cells is indisputable, particularly in those refractory to standard approaches. Despite this, we demonstrate that standardization of assessment and utilization of this critical biomarker is sorely lacking. The lack of a uniform approach to cytokine collection, platforms utilized, reporting, and correlation with clinical outcomes precludes cross-trial/cross-construct comparisons—which, if standardized, could provide important insights into CAR T cell in vivo functionality and differences between constructs. For example, data on baseline cytokine values were limited, prohibiting the analyses of cytokines as a pre-infusion predictor of toxicity or efficacy. Additionally, we found that very few articles correlated cytokines with the presence or severity of CRS, and—even more concerningly—in many cases, cytokine data were not available at all. Considering that cytokine profiling can offer invaluable insights into the in vivo functionality of CAR T cells and provide information regarding optimal management and timing of inflammatory toxicities, there remains an opportunity to unify the field on the approach toward using this indispensable biomarker.

The limitation in real-time results has indeed impaired our ability to optimally use cytokine levels for toxicity management; however, having this information available could be transformative—above and beyond our standard laboratory monitoring, as we increasingly reach for cytokine-targeted therapies. For instance, just as IL-6 levels informed management of the first child who received CAR T cells, real-time data could serve in the optimal selection of second- and third-line agents to personalize toxicity mitigation approaches to improve outcomes.

Indeed, as technical advances in platforms utilized make cytokine profiling more accessible, pushing toward standardization could enable us to further optimize our approach to toxicity management. Moreover, considering the tremendous interplay between various cytokines, the ability to explore a broad panel may be particularly critical to understanding which cytokines specifically are associated with unique toxicities—and facilitate more targeted therapies. For instance, cytokine profiling may provide actionable information about toxicity and response and shed light on the functionality of a new cell therapy. As novel immune-effector cell therapies are advanced and toxicity profiles (and optimal treatment approach) may vary from current approaches, cytokine profiling will become increasingly important.

Importantly, anti-cytokine directed therapies are not without risk, and the additive immunosuppression from using suboptimal agents could be avoided if more precise information about particular cytokine elevations could guide decision-making. Indeed, the indiscriminate use of anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., excessive doses of tocilizumab despite sufficient suppression of IL-6) adds to immunosuppression and can potentially worsen toxicity14 without benefit. Similarly, recent data on prophylactic anakinra, for example, have shown mixed results11,15,16 suggesting that not all patients will benefit from or need IL-1 targeting. If a readily available cytokine panel could inform utilization based on cytokine levels, then it could inform practice and guide intervention only when it was indicated.

In conclusion, given the tremendous potential role of cytokine profiling in CAR T cell therapy, establishing standardization will serve to advance the field and is a necessary next step in the development of these novel therapeutics. Additionally, while specific cytokine elevations have not been directly associated with efficacy, patients with more severe toxicities also have worse short- and long-term efficacy. Potentially, cytokine-informed targeted therapies could improve outcomes by preventing refractory toxicities upfront and limiting potentially deleterious immunosuppression. Accordingly, an international effort to harmonize and prioritize the incorporation of cytokine profiling as a standard component of CAR T cell biomarker testing is underway, with a particular focus on standardizing assessments of cytokines for which therapeutic interventions are available.

Materials and methods

Building upon prior efforts evaluating methodologies for CAR T cell detection,17 we analyzed 60 publications to assess how cytokines were profiled and reported. Analysis was restricted to 21 clinical trials under the purview of the US Food and Drug Administration and the 39 subsequent follow-up publications to these trials, for a total of 60 publications (Table S1). The most recent manuscript included was published on May 17, 2022.

Articles were assessed for the assays used for cytokine detection, timing and frequency of cytokine assessments, analysis and reporting thereof, and the correlation of cytokine levels with CRS and ICANS. Additionally, key clinically available biomarkers, (e.g., CRP and ferritin) and select targetable cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IFNγ) were included in our analysis. Statistical analysis was descriptive only, and data collection was restricted to the main text and supplemental appendix of the publication.

We performed two analyses of these 60 manuscripts. The first examined data within the primary publication (e.g., the first manuscript). The second analysis combined data from all publications pertaining to a given clinical trial (e.g., inclusive of subsequent manuscripts emerging from a clinical trial). Thus, this second analysis considers the cumulative information that was published from a single clinical trial.

Data and code availability

Data can be made available upon request of the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program, Center of Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute and NIH Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health (ZIA BC 011823, N.N.S). Disclaimer: The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States government.

Author contributions

D.N.B., D.P.T., B.A.S., and N.N.S wrote the first version of the manuscript, designed the study, and performed primary data analysis. C.D. contributed to technical assistance, data analysis, and writing select sections. No non-author wrote the first draft or any part of the paper. All authors contributed critically to the manuscript, reviewed the final manuscript, and have agreed to be co-authors.

Declaration of interests

N.N.S. receives research funding from Lentigen, VOR Bio, and CARGO Therapeutics. N.N.S. has attended advisory board meetings for VOR, ImmunoACT, and Sobi (all no honoraria).

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.03.030.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Kochenderfer J.N., Wilson W.H., Janik J.E., Dudley M.E., Stetler-Stevenson M., Feldman S.A., Maric I., Raffeld M., Nathan D.A.N., Lanier B.J., et al. Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood. 2010;116:4099–4102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manni S., Del Bufalo F., Merli P., Silvestris D.A., Guercio M., Caruso S., Reddel S., Iaffaldano L., Pezzella M., Di Cecca S., et al. Neutralizing IFNgamma improves safety without compromising efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy in B-cell malignancies. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:3423. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38723-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strati P., Ahmed S., Kebriaei P., Nastoupil L.J., Claussen C.M., Watson G., Horowitz S.B., Brown A.R.T., Do B., Rodriguez M.A., et al. Clinical efficacy of anakinra to mitigate CAR T-cell therapy-associated toxicity in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4:3123–3127. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris E.C., Neelapu S.S., Giavridis T., Sadelain M. Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022;22:85–96. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santomasso B.D., Park J.H., Salloum D., Riviere I., Flynn J., Mead E., Halton E., Wang X., Senechal B., Purdon T., et al. Clinical and Biological Correlates of Neurotoxicity Associated with CAR T-cell Therapy in Patients with B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:958–971. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-17-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay K.A., Hanafi L.A., Li D., Gust J., Liles W.C., Wurfel M.M., López J.A., Chen J., Chung D., Harju-Baker S., et al. Kinetics and biomarkers of severe cytokine release syndrome after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy. Blood. 2017;130:2295–2306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-793141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teachey D.T., Lacey S.F., Shaw P.A., Melenhorst J.J., Maude S.L., Frey N., Pequignot E., Gonzalez V.E., Chen F., Finklestein J., et al. Identification of Predictive Biomarkers for Cytokine Release Syndrome after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:664–679. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A., Aplenc R., Barrett D.M., Bunin N.J., Chew A., Gonzalez V.E., Zheng Z., Lacey S.F., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le R.Q., Li L., Yuan W., Shord S.S., Nie L., Habtemariam B.A., Przepiorka D., Farrell A.T., Pazdur R. FDA Approval Summary: Tocilizumab for Treatment of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell-Induced Severe or Life-Threatening Cytokine Release Syndrome. Oncologist. 2018;23:943–947. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maus M.V., Alexander S., Bishop M.R., Brudno J.N., Callahan C., Davila M.L., Diamonte C., Dietrich J., Fitzgerald J.C., Frigault M.J., et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immune effector cell-related adverse events. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J.H., Nath K., Devlin S.M., Sauter C.S., Palomba M.L., Shah G., Dahi P., Lin R.J., Scordo M., Perales M.A., et al. CD19 CAR T-cell therapy and prophylactic anakinra in relapsed or refractory lymphoma: phase 2 trial interim results. Nat. Med. 2023;29:1710–1717. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuelke M.R., Bassiri H., Behrens E.M., Canna S., Croy C., DiNofia A., Gollomp K., Grupp S., Lambert M., Lambrix A., et al. Emapalumab for the treatment of refractory cytokine release syndrome in pediatric patients. Blood Adv. 2023;7:5603–5607. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNerney K.O., DiNofia A.M., Teachey D.T., Grupp S.A., Maude S.L. Potential Role of IFNgamma Inhibition in Refractory Cytokine Release Syndrome Associated with CAR T-cell Therapy. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3:90–94. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocco J.M., Inglefield J., Yates B., Lichtenstein D.A., Wang Y., Goffin L., Filipovic D., Schiffrin E.J., Shah N.N. Free interleukin-18 is elevated in CD22 CAR T-cell-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like toxicities. Blood Adv. 2023;7:6134–6139. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gazeau N., Liang E.C., Wu Q.V., Voutsinas J.M., Barba P., Iacoboni G., Kwon M., Ortega J.L.R., López-Corral L., Hernani R., et al. Anakinra for Refractory Cytokine Release Syndrome or Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy. Transpl. Cell. Ther. 2023;29:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wehrli M., Gallagher K., Chen Y.B., Leick M.B., McAfee S.L., El-Jawahri A.R., DeFilipp Z., Horick N., O'Donnell P., Spitzer T., et al. Single-center experience using anakinra for steroid-refractory immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) J. Immunother. Cancer. 2022;10 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turicek D.P., Giordani V.M., Moraly J., Taylor N., Shah N.N. CAR T-cell detection scoping review: an essential biomarker in critical need of standardization. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2023;11 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-006596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request of the corresponding author.