Abstract

Introduction

The KEYNOTE-522 (KN-522) trial showed that the addition of pembrolizumab to standard chemotherapy improved pathological complete response (pCR) and event-free survival (EFS) for patients with early triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). We analyzed results of a real-world cohort of patients treated in a certified Breast Unit, before the introduction of pembrolizumab, to see if high quality care can match outcomes brought by the addition of an innovative anticancer therapy.

Methods

Observational, retrospective, single-center cohort study, with real-world data from an ongoing institutional database with prespecified variables. Inclusion criteria matched the ones from KN-522: previously untreated stage II or III TNBC, diagnosed between 2012 and 2022, who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The primary endpoints were pCR at the time of definitive surgery and EFS; overall survival (OS) was a secondary endpoint.

Results

Total of 168 patients were included, median age 55 years, 55 % received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with dose dense anthracyclines and taxanes and 25 % carboplatin + paclitaxel, sequenced with dose dense anthracyclines. Most had Stage II disease (82.7 %), 47 % node + disease. pCR was achieved in 52.7 % cases. At 36 months, EFS was 83.3 % (95 % CI 75.1–89.0) and OS 89 % (95 % CI, 81.6 to 93.5).

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the study limitations, outcomes of patients treated with chemotherapy without immunotherapy were numerically similar to the experimental arm of KN-522 trial. These data highlight that providing care by a specialized multidisciplinary team in a certified unit might be just as impactful as the incorporation of new technologies.

Highlights

-

•

A real-world ETNBC'cohort treated in a specialized unit, pre-pembrolizumab, ashowed survivalsimilar to KEYNOTE-522 trial.

-

•

Analyzing real-world data may provide new insights on the impact of these added regimens into routine clinical practice.

-

•

Care provided by a multidisciplinary team in a certified unit might be as impactful as incorporation of new technologies.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed human malignancy worldwide and one of the leading causes of cancer death in women. In 2020, an estimated 2.3 million new cases of female breast cancers were diagnosed and 684.996 women died due to this disease [1]. With the improvement of early diagnosis and therapeutic advances, BC is most often diagnosed at an early stage and treated with curative intent [2]. Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for 10–15 % of diagnosis and represents the subtype with worst prognosis [3]. In the treatment of early TNBC, chemotherapy is considered the standard of care, typically using anthracycline and taxane-based regimens, with the addition of carboplatin for high-risk disease [4]. Recently, the addition of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (in particular, pembrolizumab) to a backbone of chemotherapy showed clinical and statistically significant improvements in pathological complete response (pCR) rates, translating in an improvement in event-free survival (EFS), in the landmark KEYNOTE-522 trial (KN-522) [5]. The results of KN-522 led to the approval of pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy, continued as adjuvant therapy, in high-risk cases of TNBC, in 2021 by the United States Food and Administration (FDA) and 2022 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The chemotherapy backbone to which pembrolizumab was combined with was weekly paclitaxel plus carboplatin for 12 weeks followed by with doxorubicin/epirubicin with cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks for four cycles. Patients received adjuvant pembrolizumab, accounting for one year of immunotherapy, regardless of the residual disease status in the surgical specimen.

Real-world data is essential to evaluate whether results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) translate into real benefits when applied into routine clinical practice. Although RCTs often entail too stringent inclusion criteria, which limits interpretation of results for the general population, the enrollment of several sites helps to generate larger sample sizes, with greater power to test hypothesis and more generalizable findings. The KEYNOTE-522 trial included 1174 patients from 181 sites in 21 countries, including Europe, North and South America, Australia and Asia. While the high number sites and countries allows for higher inclusivity that better portray populations traditionally underrepresented in biomedical research, it also means that more heterogeneous breast cancer clinical practices were included.

Since the beginning of 2000s, several initiatives have been undertaken in order to ensure that all patients with breast cancer are treated by a dedicated multidisciplinary team [6,7]. Numerous studies have evidenced the survival benefits of treating BC patients in dedicated centers [[8], [9], [10]]. In 2020, the European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA) and the European Cancer Organisation (E.C.O.) jointly published the requirements that should be met in order to provide optimized care for BC patients, outlining a quality framework that all health systems should strive for [11]. However, there is still nowadays a wide variation of breast cancer care among and within countries, many centers still do not meet the required standards and uncountable patients are not given the opportunity to be treated in a specialized and certified center [12].

Since provision of treatment and care in dedicated centers for breast cancer may impact prognosis, it is important to describe outcomes of patients in a specialized Breast Unit. The current analysis aims to describe the outcomes of a cohort of stage II and III TNBC patients treated in an EUSOMA certified Breast Unit.

2. Materials and methods

We have conducted an observational, retrospective, single-institution cohort-study, evaluating real-world data on a patient-level basis, from Breast Care, an institutional structured database with ongoing collection of prespecified data from the medical records of patients treated at the Breast Unit of the Champalimaud Clinical Center. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice Guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Data were collected using electronic data capture and electronic health record data extraction, including disease-specific medical history, treatment response and survival. Safety data were not collected.

To ensure a comparable follow-up time with the KN-522 trial (median follow-up of 39.1 months at the fourth planned interim analysis), an analysis window from index date (start of neoadjuvant chemotherapy) to 39.1 months was applied to the EFS evaluation.

Eligibility criteria were aligned with the KEYNOTE-522 study. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or more, and had confirmed newly diagnosis of TNBC, previously untreated, nonmetastatic disease (tumor stage T1c, nodal stage N1-N2, or tumor stage T2-T4, nodal stage N0-N2), according to the primary tumor-regional lymph node staging criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition. No limitation in Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score was defined in order to rightly represent the real-world population. Likewise, no limitation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens was made, and these were classified as: ddEC, dose dense epirrubicin 100 mg/m2 and cyclofosohamide 600 mg/m2 q2w; ddPaclitaxel, dose dense Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 q2w; weekly (w) paclitaxel 80 mg/m2; wCarboplatin AUC 2; Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 with Cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 q3w; Docetaxel 100 mg/m2 q3w. Patients were excluded if enrolled in a clinical trial or used pembrolizumab as treatment for early TNBC.

The co-primary outcomes of this analysis were EFS and pCR rate. Outcome definition was considered as per the KEYNOTE-522 study protocol. Since the analysis arises from a real-world cohort, the endpoint was defined as real-world EFS (RW-EFS) and defined as time from start of neoadjuvant systemic therapy (for the real-world data set) to the date of disease progression that precluded definitive surgery, local or distant recurrence, occurrence of a second primary cancer, death from any cause or censored if alive and with no relapse at follow-up date. Diagnosis of disease recurrence was based on objective radiologic evidence, with histological confirmation obtained whenever possible. PCR rate was defined as the proportion of subjects without residual invasive cancer on hematoxylin and eosin evaluation (ypT0/Tis ypN0) assessed by the local pathologist at the time of definitive surgery following completion of neoadjuvant systemic therapy as per the AJCC staging criteria (7th edition). RW-Overall survival (OS) was a secondary outcome, defined as the number of months until death or censoring, if alive in the last follow-up available.

A descriptive analysis of the collected data was carried out. Discrete variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies, and continuous variables using trend and dispersion measures, namely median and interquartile range. Missing data were not considered in the calculation of percentages. EFS and OS plots were built using Kaplan–Meier methods. Kaplan-Meier estimates and the corresponding 95 % CIs at 18 months and three-year were provided for EFS and OS. All analysis were performed using R software version 3.5.2., R-studio version 1.1.456 and Stata 15.1 software (StataCorp LLC).

3. Results

From December 2012 until December 2022, a total of 287 patients were diagnosed with early TNBC, for which the most frequent systemic treatment used was neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n = 211, 73.5 %). For this analysis, and according to the inclusion criteria of KN-522, a total of 168 eligible patients were identified (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study enrollment.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Among the study population, the median age was 55 years (range, 25 to 82); 81.5 % of the patients were under 65 years of age.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at baseline. dd, dose dense; w, weekly; EC, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide.

| Variable | Overall Population (n = 168) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (range) - years | 50 (25–82) |

| <65 yr – no. (%) | 137 (81.5) |

| Menopausal status – no. (%) | |

| Premenopausal | 85 (50.6) |

| Postmenopausal | 83 (49.4) |

| ECOG performance status score – no. (%) | |

| 0 | 132 (79) |

| 1 | 36 [13] |

| Chemotherapy regimens | |

| Sequential ddEC, ddPaclitaxel | 84 (50) |

| wCarboplatin with wPaclitaxel sequential ddEC | 43 (25.6) |

| Administration of Carboplatin, weekly, no (%) | 43 (25.6) |

| Administration of Anthracyclines, no (%) | |

| Every 3 week | 18 (10.7) |

| Dose dense | 141 (83.9) |

| Administration of Taxanes, no (%) | |

| Weekly Paclitaxel | 68 (40.5) |

| Dose dense Paclitaxel | 85 (50.6) |

| Docetaxel | 8 (8.9) |

| Docetaxel + Cyclophosphamide | 7 (4.2) |

| T1 to T2 | 143 (85.6) |

| T3 to T4 | 24 (14.4) |

| Nodal involvement – no. (%) | |

| Positive | 79 (47.0) |

| Negative | 89 (53.0) |

| Overall disease stage – no. (%) | |

| Stage II | 139 (82.7) |

| Stage III | 29 (17.3) |

| Type of surgical procedure | |

| Mastectomy | 33 (19.7) |

| Breast Conserving Surgery | 134 (80.2) |

| HER2 status score – no. (%) | |

| 0 | 120 (71.4) |

| 1–2+ | 48 (28.6) |

| Germline BRCA – no. (%)a | |

| BRCA1+ | 5 (2.9) |

| BRCA2+ | 4 (2.4) |

Data on germline testing only available for 64 patients (38 % of the total study population).

Of the 168 patients included, most received neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on dose-dense regimens of anthracyclines and taxanes (84, 50 %) followed by 25 % (n = 43) who received an anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen with the addition of carboplatin to the paclitaxel regimen. Treatment protocols also included triple anti-emetic regimen with netupitant plus palonosetron (NEPA) and corticosteroids that were given to all patients (n=168). Most patients had Stage II disease (139; 82.7 %), with 79 (47 %) presenting with node-positive disease at diagnosis (Table 1). Disease staging was performed with positron emission tomography scan (PET-CT) for the majority of patients (64 %, n = 107).

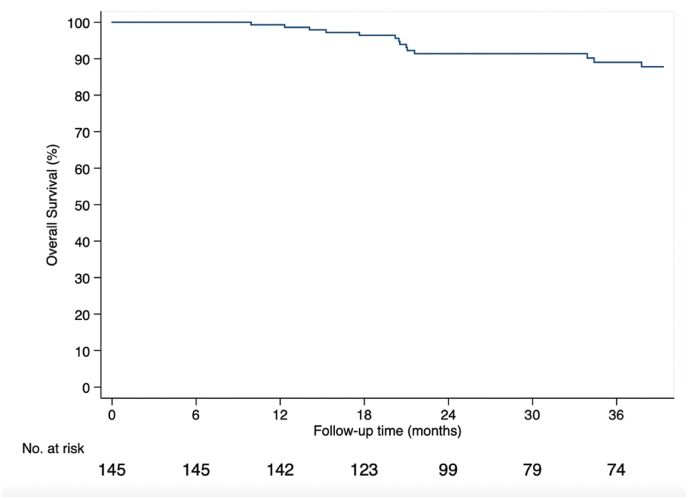

Pathological complete response (Table 2) was achieved in 52.7 % of cases (87 of 168 patients). The 18-month RW-EFS estimation was 94.3 % (95 % CI, 88.9–97.1 %) (Fig. 2). At 36 months, the estimated RW-EFS was 83.3 % (95 % CI, 75.1–89.0 %) (Fig. 2) and RW-OS was 89 % (95 % CI, 81.6–93.5 %) in the study population (Fig. 3). Table 3 shows the KN-522 main results compared to our cohort.

Table 2.

Pathological complete response, according to pathological stage.

| Variable | Overall Population (n = 168) |

|---|---|

| Pathological stage ypT0/Tis ypN0 | |

| No. of patients | 87 |

| Percentage of patients with response (95 % CI) | 52.7 |

| Pathological stage ypT0 ypN0 | |

| No. of patients | 78 |

| Percentage of patients with response (95 % CI) | 47.3 |

| Pathological stage ypT0/Tis | |

| No. of patients | 90 |

| Percentage of patients with response (95 % CI) | 54.4 |

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–meier estimates of event-free survival.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–meier estimates of overall survival.

Table 3.

Breast Unit of the Champalimaud Clinical Center (BU - CCC) cohort and KeyNOTE-522 main results.

| Variable | BU-CCC (n = 168) | KN-522 Pembrolizumab Chemotherapy (n = 784) |

KN-522 Control arm (n = 390) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Median (range) - years | 50 (25–82) | 49 (22–80) | 48 (24–79) |

| <65 yr – no. (%) | 137 (81.55) | 701 (89.4) | 342 (87.7) |

| Menopausal status – no. (%) | |||

| Premenopausal | 85 (50.59) | 438 (55.9) | 221 (56.7) |

| Postmenopausal | 83 (49.41) | 345 (44.0) | 169 (43.3) |

| ECOG performance status score – no. (%) | |||

| 0 | 132 (79) | 678 (86.5) | 341 (87–4) |

| 1 | 36 (21) | 127 (16.2) | 49 (12.6) |

| Use of carboplatin – no. (%) | 43 (25.6 %) | 100 % as per protocol | 100 % as per protocol |

| Primary tumor classification – no. (%) | |||

| T1 to T2 | 143 (85.6) | 580 (74.0) | 290 (74.4) |

| T3 to T4 | 24 (14.4) | 204 (26.0) | 100 (25.6) |

| Nodal involvement – no. (%) | |||

| Positive | 79 (47) | 405 (51.7) | 200 (51.3 %) |

| Negative | 89 (53.0) | 379 (48.3) | 190 (48.7) |

| Overall disease stage – no. (%) | |||

| Stage II | 139 (82.7) | 590 (75.3) | 291 (74.6) |

| Stage III | 29 (17.3) | 194 (24.7) | 98 (25.1) |

| HER2 status score – no. (%) | |||

| 0-1 | 148 (88.1) | 595 (75.9) | 286 (73.3) |

| 2+ | 20 (11.9) | 188 (24.0) | 104 (26.7) |

| Adjuvant use of Capecitabine - n (%) | 73 (43.3) | Not allowed as per protocol | Not allowed as per protocol |

| pCR (n; %) | 87 (52.7 %) | 260 (64.8 %) | 103 (51.2 %) |

| EFS (36-months) | 83.3 % (95 % CI, 75.1–89.0 %) | 84.5 % (95 % CI 81.7–86.9 %) | 76.8 % (95 % CI, 72.2–80.7 %) |

| OS (36 months) | 89.0 % (95 % CI, 81.6–93.5 %) | 89.7 % (95 % CI, 87.3–91.7 %) | 86.9 % (95 % CI, 83.0–89.9 %) |

4. Discussion

Our retrospective study aimed to describe the outcomes observed in a cohort of high-risk TNBC patients similar to the one included in the KN-522 study, treated by a multidisciplinary specialized team in a certified Breast Unit. At 36-month median follow-up, in our population, the EFS was 83.3 %, remarkably similar to the results of the experimental arm of the KN-522 trial (pCR of 64.8 % and EFS of 84.5 %), while the pCR rate was 52.7 %, in line with the pCR of the control arm for the same trial (51.2 % control arm of the KN-522 study).

While the achieved results in pCR in our cohort are in line with previous published studies reporting the effect of dose dense regimens and platins in such an outcome [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]], the same patient cohort, exclusively treated with chemotherapy, achieved numerically similar 3-year EFS results when compared with the experimental arm of KN-522 study, where pembrolizumab was added to the same standard chemotherapy regimen. This survival results thus emphasize key features of a dedicated and certified Breast Cancer Unit that may have a significant impact on clinical outcomes [20].

Unfortunately, individual patient data from KN-522 are not publicly available, and thus these data could not be matched according to propensity scores. Few real-world studies have been published reporting real-world outcomes of patients with early TNBC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and report overall worst EFS, although use of dose dense regimens is not present in the majority of the studies [[13], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]].

While efforts regarding breast cancer early diagnosis and adequate treatment underwent remarkable advances in the last decades, impacting not only survival but also quality of life, as the disease is diagnosed earlier and more judicious treatment decisions are made, there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure that outcomes are optimized for all patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Having access to breast cancer treatment in a specialized breast unit is a key step to achieve this goal. Yet, there is still a wide variation of breast cancer care even within developed countries, which means that many patients are still not being treated according to the best recommended practices.

It is important to note that some clear differences must be pointed out while interpreting these positive findings as our cohort was composed by lower-risk tumors, with 82.7 % of stage II disease versus approximately 75 % in the KN-522 population. Additionally, the use of adjuvant capecitabine became standard of care and was incorporated in our clinical practice, while it was not allowed in the KN-522 trial, which might have favorably influenced RW-EFS and RW-OS in our cohort and provide the strongest explanation for these positive results. On the other hand, all patients in the above referred trial used carboplatin as part of the chemotherapy backbone, while only 25.6 % used it in our cohort, which means that, despite of the use of a less intense chemotherapy regimen, we still achieved 52.7 % of pCR in our cohort.

One of the possible explanations for these very similar EFS results between our cohort and the pembrolizumab-chemotherapy arm of the KN-522 may be the use of dose dense regimens (4 cycles of epirubicin 100 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 every q2w followed by 4 cycles of paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 q2w) in most of our patients. The 2019 Lancet meta-analysis [18] showed an absolute reduction of about 3.7 % in recurrence, with the use of dose dense regimens for estrogen receptor-negative BC when compared to standard-schedule chemotherapy. Similar results were presented in the phase 3 GIM 2 trial, with improved disease-free survival and OS with the use of the same dose dense regimens [28]. Though recommended by guidelines, the implementation of dose dense regimens in clinical practice may be challenging as it requires primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating growth factors (G-CSF). G-CSF are not always a readily accessible option in some centers and require more than one administration when pegfilgastrim is not available, which may sometimes reduce patient compliance. Inadequate medullary support leads to higher rates of hematological toxicities in the form of neutropenia with subsequent chemotherapy administration delays and dose reductions, hampering the delivery of appropriate chemo-density.

The role of the addition of carboplatin to the standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens, was evaluated in 1 phase III and 2 phase II and trials [[14], [15], [16], [17]], demonstrating an increase in pCR of about 20 %, with an increment of EFS, as showed in the updated analysis of the Gepar-Sixto and BrighTNess trials. The 3-year disease free survival (DFS) analysis of the Gepar-Sixto revealed a 10 % higher DFS in TNBC patients receiving additional carboplatin when comparing with anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy alone. Likewise, in the BrighTNess study, EFS rates at 4 years were 79 % (95 % CI 72.9–86.2) with carboplatin plus paclitaxel and 69 % (95 % CI 61.3–76.6) with paclitaxel alone [14,16,29]. In our study, only 25 % patients received carboplatin, since this treatment was only incorporated in the standard treatment option after the publishing of these trials in 2018.

Another important aspect to be considered is that local practices vary among centers recruiting patients into clinical trials, which may impact in suboptimal management of toxicities and, consequently, drug delivery. These differences include but are not limited to protocols for prevention of drug-induced adverse events, such as the given example of G-CSF, or of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), as well as prompt access to medical management even for low-grade toxicities, which may still impact on quality of life. In highly-emetogenic protocols such as the ones used to treat TNBC, the sum of these small differences may have a clinically meaningful impact, with drug delays and treatment discontinuations, which highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary team effort in treating these patients. For instance, in our institution, we use NEPA, a fixed combination of the neurokinin-11 receptor antagonist netupitant with the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor antagonist palonosetron and corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone, as standard of practice. All patients included in this study indeed received this supportive therapy regimen. We are, however, fully aware that NEPA is not available in several centers, despite of its proven superiority in the prevention of the nausea and vomiting associated with anthracyclines/cyclophosphamide based chemotherapy [30,31].

Additionally, better patient selection may also play a role in this picture, as we have access to PET-CT to virtually all high-risk TNBC. Indeed, this might further explain that, despite pCR rates in our study cohort were in line with the control arm of the KN-522 study, EFS and OS matched the results seen with the addition of pembrolizumab in the experimental arm of the same trial. The easy access to PET-CT as a diagnostic method allows for a more precise detection of distant metastasis, compared with conventional imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) and bone scan, due to its higher sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy [32]. Since PET-CT is the preferred method of staging for distant disease in TNBC, especially stages II and III, distant metastasis will be detectable at a higher rate in a center such as ours, leading to better patient selection. In our study cohort, most patients were staged with PET-CT.

It is important to highlight the relevant limitations of these data such as its retrospective nature, the fact of being a single-center experience, its small sample size and the lack of safety data. Additionally, the analysis of real-world data may bring important confounding factors that need to be accounted for, as the variability of patient characteristics, selection bias as well as data quality and completeness, which are amenable to impact validity. Nevertheless, this study brings to light the excellent results that can be achieved with high quality clinical management. As our experience with the clinical use of pembrolizumab in the neoadjuvant setting grows in our institution, an updated analysis including patients who received immunotherapy is already planned when enough mature data is available.

5. Conclusions

The authors have no doubt about the added benefit of pembrolizumab to chemotherapy for the neoadjuvant treatment of patients with early TNBC. Phase III trials are the gold-standard to prove the superiority of one treatment strategy over another. Our intention with this research is to foster the discussion on the relevance of the optimal clinical management of these high-risk patients who demand intensive and complex-to-manage systemic treatment protocols. Based on the remarkable results of the KN-522 trial and the results of our observational study, one can conjecture how much improvement can arise from offering this treatment regimen within the scope of multidisciplinary teams. National cancer plans and networking of cancer units is pivotal and a priority to ensure that all individuals receive treatment and care according to the best available evidence and expertise. Our data highlight that clinical care is probably equally impactful to the incorporation of new drugs, so investments should prioritize the ethics of care just as much as the incorporation of new technologies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Leonor Vasconcelos de Matos: Writing – review & editing. Marcio Debiasi: Writing – review & editing. Teresa Gantes Padrão: Writing – review & editing. Berta Sousa: Writing – review & editing. Fatima Cardoso: Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

None.

Contributor Information

Leonor Vasconcelos de Matos, Email: leonor.matos@fundacaochampalimaud.pt.

Fatima Cardoso, Email: fatimacardoso@fundacaochampalimaud.pt.

References

- 1.Merino M.J. Gattuso's differential diagnosis in surgical pathology [internet] Elsevier; 2022. Breast; pp. 721–762.https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780323661652000132 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbeck N., Penault-Llorca F., Cortes J., Gnant M., Houssami N., Poortmans P., et al. Breast cancer. Vol. 5. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2019 Sep 23;5(1):66. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dafni U., Tsourti Z., Alatsathianos I. vol. 14. Breast care; Basel, Switzerland: 2019. pp. 344–353. (Breast cancer statistics in the European union: incidence and survival across European countries). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardoso F., Kyriakides S., Ohno S., Penault-Llorca F., Poortmans P., Rubio I.T., et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up† Ann Oncol [Internet] 2019 Aug 1;30(8) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz173. 1194–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid P., Cortes J., Pusztai L., McArthur H., Kümmel S., Bergh J., et al. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):810–821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Parliament resolution on breast cancer in the European Union [Internet]. Available from: http://bit.ly/1QEU860.

- 7.Bultz B.D., Speca M. Comment on:The EUSOMA Position Paper on the requirements of a specialist breast unit Eur. J Cancer. 2000;36:2288–2293. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00133-2. Eur J Cancer [Internet]. 2001 Aug 1;37(12):1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skinner K.A., Helsper J.T., Deapen D., Ye W., Sposto R. Breast cancer: do specialists make a difference? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003 Jul;10(6):606–615. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillis C.R., Hole D.J. Survival outcome of care by specialist surgeons in breast cancer: a study of 3786 patients in the west of Scotland. BMJ. 1996 Jan;312(7024):145–148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7024.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesson E.M., Allardice G.M., George W.D., Burns H.J.G., Morrison D.S. Effects of multidisciplinary team working on breast cancer survival: retrospective, comparative, interventional cohort study of 13 722 women. BMJ. 2012 Apr;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biganzoli L., Cardoso F., Beishon M., Cameron D., Cataliotti L., Coles C.E., et al. The requirements of a specialist breast centre. Breast. 2020;51:65–84. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2020.02.003. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960977620300606 [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardoso F., Cataliotti L., Costa A., Knox S., Marotti L., Rutgers E., et al. European Breast Cancer Conference manifesto on breast centres/units. Eur J Cancer [Internet] 2017;72:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paluch-Shimon S., Friedman E., Berger R., Papa M., Dadiani M., Friedman N., et al. Neo-adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel in triple-negative breast cancer among BRCA1 mutation carriers and non-carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016 May;157(1):157–165. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3800-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loibl S., Weber K.E., Timms K.M., Elkin E.P., Hahnen E., Fasching P.A., et al. Survival analysis of carboplatin added to an anthracycline/taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy and HRD score as predictor of response-final results from GeparSixto. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2018 Dec;29(12):2341–2347. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shepherd J.H., Ballman K., Polley M.-Y.C., Campbell J.D., Fan C., Selitsky S., et al. CALGB 40603 (alliance): long-term outcomes and genomic correlates of response and survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without carboplatin and bevacizumab in triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2022 Apr;40(12):1323–1334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geyer C.E., Sikov W.M., Huober J., Rugo H.S., Wolmark N., O'Shaughnessy J., et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of addition of carboplatin with or without veliparib to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: 4-year follow-up data from BrighTNess, a randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2022 Apr;33(4):384–394. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loibl S., O'Shaughnessy J., Untch M., Sikov W.M., Rugo H.S., McKee M.D., et al. Addition of the PARP inhibitor veliparib plus carboplatin or carboplatin alone to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer (BrighTNess): a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 1;19(4):497–509. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30111-6. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Increasing the dose intensity of chemotherapy by more frequent administration or sequential scheduling: a patient-level meta-analysis of 37 298 women with early breast cancer in 26 randomised trials. Lancet (London, England) 2019 Apr;393:1440–1452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33137-4. 10179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Möbus V., Lück H.-J., Ladda E., Klare P., Schmidt M., Schneeweiss A., et al. Phase III randomised trial comparing intense dose-dense chemotherapy to tailored dose-dense chemotherapy in high-risk early breast cancer (GAIN-2) Eur J Cancer. 2021 Oct;156:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmid P., Cortes J., Dent R., Pusztai L., McArthur H., Kümmel S., et al. Event-free survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):556–567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biswas T., Efird J.T., Prasad S., Jindal C., Walker P.R. The survival benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and pCR among patients with advanced stage triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017 Dec;8(68):112712–112719. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurley J., Reis I.M., Rodgers S.E., Gomez-Fernandez C., Wright J., Leone J.P., et al. The use of neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer that is triple negative: retrospective analysis of 144 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013 Apr;138(3):783–794. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2497-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villarreal-Garza C., Bargallo-Rocha J.E., Soto-Perez-de-Celis E., Lasa-Gonsebatt F., Arce-Salinas C., Lara-Medina F., et al. Real-world outcomes in young women with breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016 Jun;157(2):385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma P., López-Tarruella S., García-Saenz J.A., Khan Q.J., Gómez H.L., Prat A., et al. Pathological response and survival in triple-negative breast cancer following neoadjuvant carboplatin plus Docetaxel. Clin cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2018 Dec;24(23):5820–5829. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao Z., Chaudhri S., Guo M., Zhang L., Rea D. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer: an observational study. Oncol Res. 2016;23(6):291–302. doi: 10.3727/096504016X14562725373879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang M., O'Shaughnessy J., Zhao J., Haiderali A., Cortes J., Ramsey S.D., et al. Association of pathologic complete response with long-term survival outcomes in triple-negative breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Res. 2020;80(24):5427–5434. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haiderali A., Rhodes W.C., Gautam S., Huang M., Sieluk J., Skinner K.E., et al. Real-world treatment patterns and effectiveness outcomes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Future Oncol. 2021;17(29):3819–3831. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Mastro L., Poggio F., Blondeaux E., de Placido S., Giuliano M., De Laurentiis M., et al. 134O Dose-dense adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage breast cancer patients: end-of-study results from a randomised, phase III trial of the Gruppo Italiano Mammella (GIM) Ann Oncol. 2022 Sep 1;33:S599–S600. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.169. [Internet] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason S.R.E., Willson M.L., Egger S.J., Beith J., Dear R.F., Goodwin A. Platinum‐based chemotherapy for early triple‐negative breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet] 2023;(9) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014805.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelek L., Navari R., Aapro M., Scotté F. Single-dose NEPA versus an aprepitant regimen for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Cancer Med. 2023 Aug;Epub 2023 Aug 3. PMID;12(15):15769–15776. doi: 10.1002/cam4.6121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aapro M., Rugo H., Rossi G., Rizzi G., Borroni M.E., Bondarenko I., et al. A randomized phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of NEPA, a fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2014 Jul;25(7):1328–1333. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koolen B.B., Vrancken Peeters M.-J.T.F.D., Aukema T.S., Vogel W.V., Oldenburg H.S.A., van der Hage J.A., et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT as a staging procedure in primary stage II and III breast cancer: comparison with conventional imaging techniques. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012 Jan;131(1):117–126. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1767-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]