Abstract

The leptomeninges, the cerebrospinal-fluid-filled tissues surrounding the central nervous system, play host to various pathologies including infection, neuroinflammation and malignancy. Spread of systemic cancer into this space, termed leptomeningeal metastasis, occurs in 5–10% of patients with solid tumours and portends a bleak clinical prognosis. Previous, predominantly descriptive, clinical studies have provided few insights. Recent development of preclinical leptomeningeal metastasis models, alongside genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic sequencing efforts, has provided groundwork for mechanistic understanding and identification of long-needed therapeutic targets. Although previously understood as an anatomically isolated compartment, the leptomeninges are increasingly appreciated as a major conduit of communication between the systemic circulation and the central nervous system. Despite the unique nature of the leptomeningeal microenvironment, the general principles of metastasis hold true: cells metastasizing to the leptomeninges must gain access to the new environment, survive within the space and evade the immune system. The study of leptomeningeal metastasis has the potential to uncover novel site-specific metastatic principles and illuminate the physiology of the leptomeningeal space. In this Review, we provide a biology-focused overview of how metastatic cells reach the leptomeninges, thrive in this nutritionally sparse environment and evade the detection of the omnipresent immune system.

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) metastases represent a complication of cancer that generates disproportionate morbidity and mortality. The CNS comprises the brain and the spinal cord and is encased by the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-filled leptomeninges. In the pregenomic era, CNS metastases were diagnosed and managed using local techniques (radiation therapy and surgical resection) with palliative intent. The genomic revolution in cancer biology brought major changes to the management of brain and spinal metastases. Once identified through imaging, resected metastatic tissues can be sequenced and treated with CNS-penetrant therapies. As a result, outcomes for select patients with brain and spine metastases have rapidly improved; in many cases, local therapy and associated morbidities may be avoided entirely. Unfortunately, these advances have not improved outcomes associated with leptomeningeal metastasis.

The leptomeninges comprise a unique cadre of tissues and biological fluids not found elsewhere in the body1 (Fig. 1a and Box 1). They consist of the pia mater and the arachnoid mater and form a CSF-filled interface between the systemic circulation and the central nervous system. Unlike parenchymal brain and spine metastases, which are encased by a capsule, largely isolating them from the remainder of the brain, leptomeningeal metastases exist in two phenotypic states: adherent to the pia mater, and as floating tumour cells circulating within the spinal fluid2. Leptomeningeal metastases therefore inhabit and perturb the entire CNS. In doing so, leptomeningeal metastases result in a wide variety of progressive neurologic disabilities, severely impacting patient quality of life (Box 2). The leptomeninges are encased by the dura mater (also known as the pachymeninges) and the skull. Importantly, because the dura mater resides outside the CNS, dural metastasis does not constitute leptomeningeal metastases.

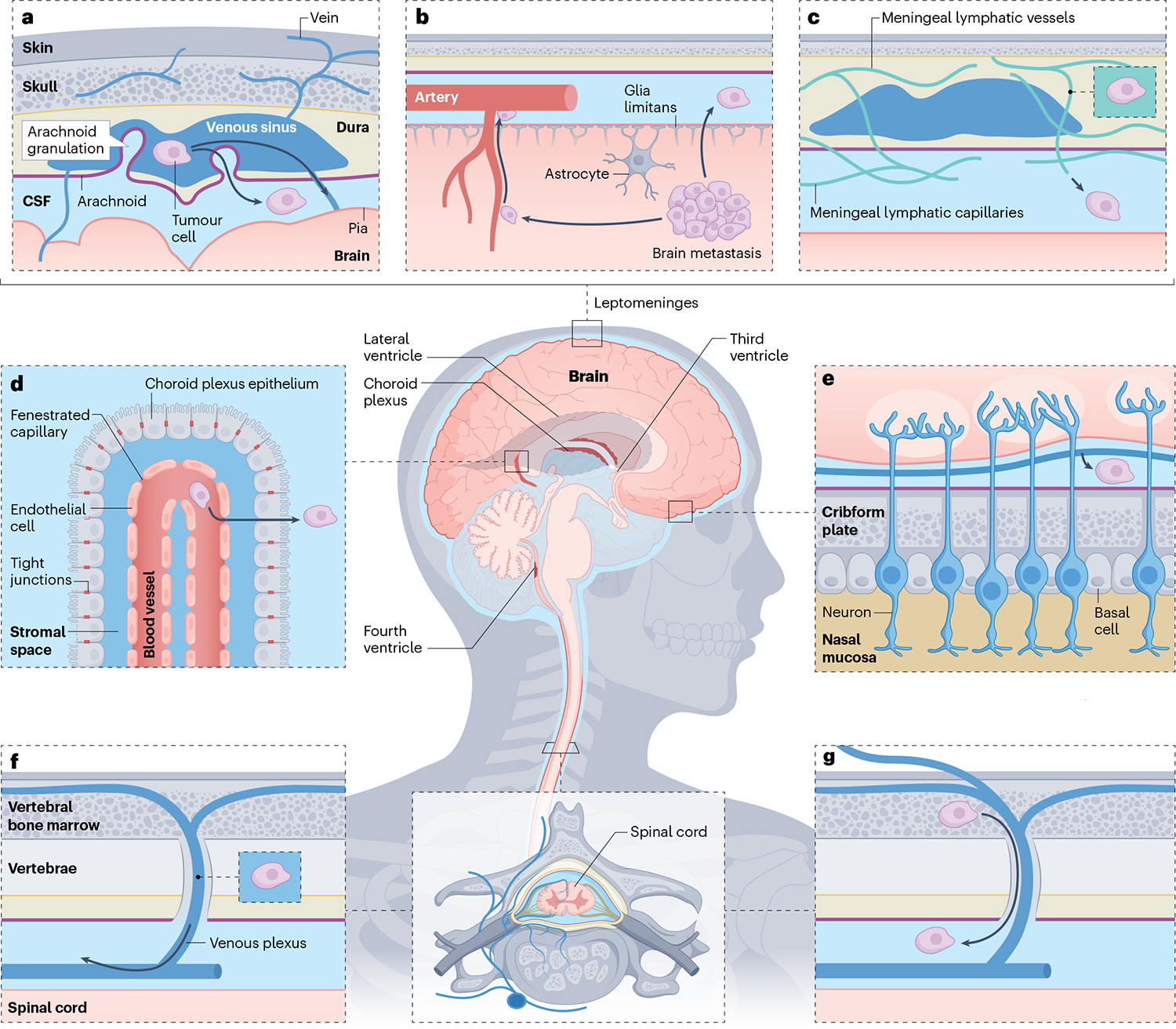

Fig. 1 |. Anatomical routes of cancer cell entry into the leptomeninges.

The leptomeninges consist of the pia and arachnoid membranes, contain the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and encase the entire central nervous system. Cancer cells outside the central nervous system may access the leptomeningeal compartment through various anatomical ports of entry. a, Cancer cells within the venous sinuses may breach the arachnoid granulations. b, Tumours or single cells within the brain parenchyma may invade and breach the glia limitans to reach the CSF-filled perivascular (Virchow-Robin) spaces. c, Cancer cells within the dura may invade the meningeal lymphatic vessels to access the CSF. d, Cancer cells within the arterial circulation slip through fenestrated vessels to arrive in the well-perfused choroid plexi. Crossing the choroid plexus epithelial cell tight junctions provides access to the CSF-filled ventricles. e, Cancer cells may migrate along cranial nerves, making use of pre-existing tissue planes. f, Cancer cells within the low-pressure, valveless, Batson venous plexus of the spinal cord are well positioned to breach the spinal arachnoid to gain entry into the CSF. g, Communicating bridging veins provide leptomeningeal access for cancer cells within the bone marrow.

Box 1 |. Anatomy and physiology of brain barriers.

The central nervous system and the immune systems co-evolved in phylogenetic time generating several barrier mechanisms137. The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is formed by endothelial cells connected by tight junctions and surrounded by pericytes with greatly limited transcytosis and paracellular flux. This barrier serves the parenchyma throughout the central nervous system and delivers oxygen and nutrients to the parenchyma138. The choroid plexus is a highly perfused structure located in the ventricles, the fluid-filled cavities of the brain. Its epithelial cells are knit together with tight junctions and are responsible for the secretion of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and constitute the blood–CSF barrier68. The blood–leptomeningeal barrier is formed by the arachnoid mater, a sheet of connective tissue that covers the brain and spine and contains small vessels. Arachnoid is composed of fibroblastoid cells that can co-express epithelial genes and are connected through tight and adherent junctions139,140. These three barriers constitute the critical interfaces between the periphery and brain that actively restrict the entry of solutes and cells into the brain parenchyma and meninges. Finally, the glia limitans, a dense layer of extracellular matrix between the pia and astrocytes in the parenchyma, governs the flow in the CSF and constitutes part of the glymphatic system59. This perivascular network distributes solutes between the parenchymal interstitial fluid and CSF. The function of these barriers is tightly regulated and vital for homeostasis, ensuring apparent isolation of brain parenchyma from the dangers of the periphery. When needed, these barriers can temporarily break down, allowing for immune-system-mediated elimination of pathogens or cancers. These barriers can also break down permanently, as a consequence of autoimmune processes and neurodegeneration or as a result of exploitation by metastasizing cancer cells.

Box 2 |. Clinical aspects of leptomeningeal metastasis.

Cancer cells that have metastasized to the leptomeninges can freely float in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or grow adherent to the surface of the brain and spinal cord; both metastatic states can trigger a spectrum of clinical symptoms2. These symptoms can vary and change rapidly, evading early clinical diagnosis141. The symptomatology is therefore referred to as ‘protean’ after the Greek mythological god of the rivers and seas; a master of disguise who often changed shape to avoid attention. CSF is produced by the choroid plexus in the cerebral ventricles and circulates through the ventricular system and around the spinal cord until it is reabsorbed into the venous system. Cancer in the leptomeninges obstructs the CSF flow, leading to an increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and in some cases hydrocephalus. Elevated ICP manifests as headaches and nausea and, in more severe cases, also in changes in vision and consciousness, such as confusion. Hydrocephalus is a chronic, severe and potentially fatal elevation in ICP and must be clinically managed by either frequent CSF withdrawals or surgical instalment of a shunt that reroutes CSF to relieve the elevated pressure. Cancer growth around cranial nerves affects vision, hearing and function of muscles in the eyes, face and neck of the patient. Interference with cranial cortex can induce seizures and affect motor, sensory and cognitive functions. Moreover, inflammatory and metabolic changes in the CSF triggered by the presence of metastasis can affect the state of consciousness and functional changes in brain activity eventually leading to neurological death. Although we have very little mechanistic understanding of these processes in leptomeningeal metastasis, this a subject of active investigation in the field of parenchymal cancer neuroscience142. Metastatic involvement of leptomeninges around the spinal cord, spinal nerve roots and cauda equina leads to pain, loss of motor and sensory function in the limbs and bladder and bowel dysfunction. Because we lack curative approaches to combat leptomeningeal metastasis, management of these symptoms is generally palliative, focusing on symptom control to enable a reasonable quality of life. In select, rare cases, such as childhood pilocytic astrocytoma, leptomeningeal dissemination can be successfully managed in a proportion of patients143.

Unlike lung, liver or even brain parenchymal metastases, leptomeningeal metastasis typically manifests years following primary tumour diagnosis3,4. Formally, the explanation for this profound delay is unknown; however, it suggests that this anatomically isolated, inhospitable environment likely requires extensive selection of survival programmes. Leptomeningeal metastasis therefore represents an appealing subject for the study of cancer evolutionary dynamics, including selection, drift and clonal expansion. Indeed, genomic analyses of matched primary breast cancers and their respective leptomeningeal derivatives from humans demonstrate divergence consistent with selection5. The anatomic location of the premetastatic niche (or niches) where such selection might occur remains unclear. Probable anatomic locations for this selection include the calvarial bone marrow, the choroid plexi and/or the cervical lymph nodes, all of which are sites of leukocyte access to and egress from the leptomeninges6–9. Although the leptomeningeal metastasis epigenome has not yet been addressed, transcriptomic analysis of preclinical epithelial leptomeningeal metastasis models demonstrates selection for cancer cells harbouring genes that perturb the local microenvironment to support the metabolic needs of the tumour10. These leptomeningeal metastatic cells upregulate genes encoding secreted products such as complement component 3 (C3) or lipocalin 2 (LCN2)11. Some cancer subtypes, such as epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer, melanoma, lobular breast cancer and triple-negative breast cancer, demonstrate increased incidence of leptomeningeal metastasis12–14, whereas others, such as colorectal or pancreatic cancers, have much lower propensity to generate leptomeningeal metastases. Formal experimental evidence supporting a causal relationship between genomic alterations and site-specific metastasis is lacking, despite several large-scale genomic sequencing efforts15–17.

A unique and provocative aspect of metastasis to leptomeninges is the capacity of this malignancy for both adherent and anchorage-independent growth2. This adherent subpopulation thrives adherent to the pia mater, resulting in radiologically apparent lesions over the brain and spinal cord surface. Interestingly, the leptomeninges in different anatomical locations result from distinct embryonic origins18. Differences in local pial microenvironments may therefore nurture and select for distinct adherent tumour subpopulations, reflecting these developmental differences19. In vitro experimental systems have uncovered that the cancer cells floating within the CSF exist in equilibrium with cells adherent to the pia mater. The phenotype of these ‘floating’ cells may be associated with stemness, allowing cancer cells to adopt a floating state for prolonged periods of time and avoid anoikis20. The direct relationship between these floating and adherent cells in vivo remains unknown; in vitro modelling supports their bidirectional plasticity2.

Clinical approaches for the treatment of leptomeningeal metastasis have historically borrowed from those used for metastases to extracranial sites, as well as those employed against paediatric and liquid tumours21. Because leptomeningeal metastatic cells coexist in two phenotypes, floating and adherent, leptomeningeal metastasis encompasses the entire leptomeningeal compartment. Treatment beyond palliative intent therefore addresses the entire compartment and can include radiation22, systemic therapies23,24 and intrathecally delivered therapies25–27. Despite this array of potential therapeutic modalities, overall survival of patients with leptomeningeal metastasis is generally <1 year. In this Review, we present the current biological understanding of leptomeningeal metastasis, from cancer cell entry into the space, growth within the leptomeninges and immune evasion. Advances in understanding within each of these domains have recently occurred, laying the groundwork for further mechanistic investigations of leptomeningeal metastasis.

Gaining leptomeningeal access

Cancer cells may gain entry to the leptomeningeal space through a number of ways (Fig. 1). Pathological and histological autopsy studies highlight direct hematogenous spread, direct perineural infiltration and indirect secondary metastasis as the major routes of leptomeningeal access28,29. Entry by each of these means poses unique constraints on an entering cell. Formally, any primary tumour may gain access through any route of entry. However, certain primary cancers may be more likely to employ a given route of entry as a result of their cell of origin or anatomic location of the primary tumour. Emerging research suggests that this colonization can occur strikingly early in the evolution of primary tumours30.

Arterial dissemination

The choroid plexuses represent unusually well-perfused structures located within each of the brain’s four ventricles31. They serve as the blood–CSF barrier and produce the vast majority of CSF32. Each choroid plexus is composed of fenestrated arcades of endothelium (meaning they lack tight junctions) surrounded by polarized, secretory epithelium knit together by tight junctions. At rest, the capillaries enable spread of small molecules and cells into the choroid plexus stroma. The choroid plexus epithelial cells then prevent the passage of cells and large molecules from the stroma into the CSF. In the setting of systemic inflammation, this pattern is reversed: the endothelium transitions into a vascular barrier33, and the tight junctions of the choroid plexus epithelium become leaky, enabling passage of trapped stromal contents into the leptomeningeal space11. Exploiting this physiology, it has been hypothesized that once tumour cells are within the choroid plexus stroma, they may incite a local inflammatory response to close the endothelial barrier and loosen the tight junctions of the choroid plexus epithelial cells to enable invasion into the CSF.

However, the mechanisms for how tumour cells might breach the choroid plexus stroma remain unknown. Studies from haematogenously disseminated medulloblastoma cells support a mechanism whereby cancer cell expression of the C-C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) and its ligand C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) enables access to the leptomeninges34, in analogy to mechanisms employed by macrophages to populate leptomeninges through the choroid plexus7. Furthermore, histopathologically apparent deposits of cancer cells have been observed within the choroid plexus stroma in a number of human autopsy studies29,35, suggesting that the choroid plexuses may serve as a premetastatic niche, supporting the selection and adaptation of clones fit to survive within the hostile CSF-filled leptomeninges. Observation of this phenomenon in a xenograft breast cancer mouse model further supports this11. The exact molecular mechanisms governing cancer cell entry to and egress from the choroid plexus stroma remain unknown; therefore, future studies in human tissues and formal lineage tracing in animal models are necessary to confirm and mechanistically address this phenomenon.

Perivascular spread

The major vasculature of the CNS courses through the leptomeningeal space, but does not deliver its cargo until after the branching arterioles plunge into the parenchyma, shedding layers of vascular lamina as they course, until terminating in capillary networks. Along their path, the vessels are encircled by perivascular fibroblasts, surrounded by the perivascular space, and filled with CSF36. These perivascular spaces, also known as Virchow-Robin spaces, extend to the parenchyma37. Deposits and nodules of metastasizing cancer have been observed nearby and within these perivascular spaces29,38; how solid tumours might breach these barriers remains unknown. In the case of lymphoma and leukaemia with leptomeningeal involvement, cancer cell overexpression of classical immune adhesion molecules including integrins α4, α6 and αL contributes to leptomeningeal colonization and chemoresistance39–42. Solid tumour cells within the parenchyma may well employ similar mechanisms to enter the leptomeninges.

Perineural invasion

Extending from the CNS, the peripheral nervous system branches to provide enervation to all tissues. Cancer cells may utilize the nerves and ganglia of the peripheral nervous system to gain access to the leptomeninges. This perineural route of metastatic spread is a common yet understudied route of distant tissue colonization by cancer43. The leptomeninges can be accessed by cancer cells migrating along the perineural space of cranial, spinal and peripheral nerves44. Cancer cells successfully inhabiting the perineural spaces encounter a microenvironment reminiscent of the leptomeninges marked by elevated local concentrations of neuropeptides and neurotransmitters. Signalling from these secreted molecules may promote pro-survival electrical and metabolic signalling in tumour cells, supporting growth and migration centripetally towards the CNS45–48. The perineural route of leptomeningeal access offers many advantages to the invading cancer cell, but is likely most clinically relevant in settings in which the distance a cancer cell must travel to reach the CNS is relatively short, such as head and neck tumours (along the cranial nerves) and spinal tumours (along the spinal nerve roots).

Lymphatic spread

Metastatic spread of cancer to non-CNS sites via the lymphatics demonstrates higher efficiency than haematogenous dissemination, in part due to the protective, buffering capacity of the lymph itself, mitigating oxidative stress and ferroptosis49. Recent discovery of meningeal lymphatics draining CSF in mice suggests that these structures may serve as additional possible points of entry into and egress from the leptomeninges50–52. Cancer cells within these novel routes of possible access into the leptomeninges have not yet been appreciated in autopsy studies. The exact anatomical and physiological implications of this system in human leptomeningeal metastasis are not yet well explored; this hypothesis remains ripe for systematic investigation.

Ternary spread from adjacent metastatic lesions

Cancer cells may also invade leptomeninges secondarily from other metastatic sites, further exploiting a pan-metastatic phenotype. The bone marrow and the brain parenchyma represent the two major metastatic sites that enable access to the leptomeninges. Lessons from haematopoietic tumours suggest that cancer can reach the CSF secondarily from bone marrow through the bridging vessels42. These structures connect the calvarial bone marrow (found in the skull) and vertebral bone marrow (found in the spine) with the subarachnoid space, allowing for a local supply of myeloid immune cells8. Leukaemic cells reaching the CSF from the bone marrow express high levels of integrin α6, mediating interactions with endothelial-expressed laminin in these bridging vessels to enable tumour cell migration. Solid tumours that frequently spread to the bone marrow may also express integrin α6 or other immune-like phenotypes to colonize CSF through vertebral and calvarial bone marrow, as observed in pathological specimens28,53.

In the case of vertebral and paravertebral lesions, secondary leptomeningeal metastasis can be achieved through accessing Batson’s venous plexus. This valveless network of vessels provides venous drainage for the pelvis and spinal cord with bidirectional flow, allowing for retrograde spread of tumour cells throughout this vasculature28,54.

Direct invasion from adjacent brain parenchymal, subdural and epidural lesions has also been observed in autopsy studies29. These observations suggest that cancer from subcortical or subventricular lesions may invade the pia mater or ependyma, respectively, to reach the CSF. Perhaps unsurprisingly, certain surgical interventions to remove primary or metastatic masses from the brain parenchyma, including resection of tumours in the posterior fossa and piecemeal resection (that is, resections breaching the tumour capsule), can occasionally result in seeding of the leptomeninges55–58, further highlighting the protective role of the glia limitans59. As in other routes of cancer cell entry into the leptomeninges, the possibility of direct invasion from brain parenchyma or a possible involvement of haematogenous route for this phenomenon has yet to be confirmed with modern genetic tools in human tissues and/or reliable preclinical systems. Such studies would require direct genetic comparison among the primary tumour, resected brain lesion and newly collected leptomeningeal mass; and, ideally, cellular tracing experiments in preclinical resection models.

Survival within the leptomeninges

Regardless of the anatomical route of entry, cancer cells entering the leptomeninges confront a microenvironment profoundly unlike that of the primary tumour. In the absence of disease, the leptomeningeal compartment is notable for its paucicellularity, scarce growth factors, minimal metabolic intermediates and hypoxia. Although cancer cells must overcome each of these constraints in concert, we address each of these aspects singly.

Inflammatory signalling

The quiescent leptomeninges are notable for a near total lack of immune cells and immune cell signals. However, in the presence of leptomeningeal metastases, the leptomeningeal space plays host to various inflammatory cells and inflammatory signalling molecules10,60,61. Early neuro-oncological reports described leptomeningeal metastasis as ‘carcinomatous meningitis’ owing to gross similarities with infectious meningitis, including an accumulation of ‘sterile pus’ rich in leukocytes over the surface of brain and spine62. These early reports underline the profound degree of inflammatory signalling present in the space in the presence of malignancy.

Recent untargeted proteomic characterization of CSF in the setting of melanoma leptomeningeal metastasis provided one of the first insights into the extracellular microenvironment in leptomeningeal metastasis61. In this case, the dominant pathways uncovered were related to activation of the innate system and included evidence of complement activation, cell adhesion, platelet activation, insulin-like growth factor 1 and Notch signalling. Unsurprisingly, in addition to these pathways, proteins associated with granulocyte activity, including proteases and their inhibitors, were also elevated, as well as evidence suggesting neuronal damage owing to the accumulation of neurofilament light chain. Together, this CSF proteomic analysis paints a picture of robust innate immune activation leading to neuronal damage. This is consistent with elevated levels of soluble extracellular matrix components detected in CNS metastasis more generally63.

An essential component of the innate immune system, the complement cascade, has been mechanistically implicated in metastatic cancer cell growth in the leptomeninges. The complement system represents a phylogenetically ancient cascade of soluble, proteolytically regulated innate immune regulators and effectors. C3 was found to be upregulated by lung and breast cancer cells competent to metastasize to the leptomeninges. By activating the C3a receptor (C3aR) on choroid plexus epithelial cells, C3 triggers the disorganization of epithelial tight junctions and allows for passage of growth factors and likely also low-molecular weight nutrients from the plasma, supporting cancer cell growth within the leptomeninges11. The roles of other complement components enriched in leptomeningeal metastasis (C3b, C5 and C4b) have not yet been addressed; it is likely that these substantially contribute to the immunosuppressive nature of the CSF64. Pharmacological inhibitors of the complement pathway have been the subject of experimental and clinical investigation for a number of pathologies65. In the case of leptomeningeal metastasis, local, intrathecal delivery of C3aR or C3a inhibitors could potentially restore choroid plexus barrier function while sparing these patients from systemic side effects.

Moreover, the array of morphogens and growth factors that can alter barrier function of both choroid plexus epithelial cells and meningeal fibroblasts is likely substantially wider and more complex than currently appreciated. This blood–CSF barrier breakdown probably also contributes to enhanced entry of blood-borne leukocytes and feedforward acceleration of leptomeningeal inflammation. As such, targeting a single pathway may not be sufficient to achieve full therapeutic control of this environment.

Leptomeningeal metastasis represents a unique pathology poised to advance our understanding of leptomeningeal inflammation61,66. In particular, investigation of how individual inflammatory factors and acute phase reactants might contribute to leptomeningeal metastasis growth, microenvironmental remodelling and neural damage will illuminate our understanding of brain–CSF communication and their co-evolved function in homeostasis. To date, such work has remained limited, owing to a lack of suitable tools and techniques, as mechanistic interrogation of this phenomenon requires reliable syngeneic animal models, representative of human leptomeningeal metastasis as well as techniques for the collection and analysis of mouse CSF (Box 3). Many of these obstacles have recently been overcome, and the field is now poised to make substantial progress in this area10,11,66.

Box 3 |. Models that unravel leptomeningeal biology through the lens of metastasis.

The mouse is the most commonly employed organism to model leptomeningeal metastasis and metastasis in general. However, genetically engineered mouse models and cell lines that colonize brain parenchyma from primary tumours are rare144–146. Additionally, systems that spontaneously spread to the surrounding leptomeninges are vanishingly rare. To overcome these obstacles, researchers have adapted various iterative in vivo selection strategies making use of cell line and patient-derived xenografts for mechanistic studies.

Modern models of leptomeningeal metastasis include well-characterized syngeneic and xenograft derivatives of lung, breast carcinoma and melanoma cell lines10,11,103. Xenograft lines allow for the study of human cancer cell-intrinsic aspects of leptomeningeal metastasis and provide some limited insights into microenvironmental phenomena. Although syngeneic lines allow for investigation of the full spectrum of immune cell types in a well-controlled manner, there is a risk of a possible detour into mouse-specific differences147. It is therefore critical to complement the animal model findings with human data. Intriguingly, for decades, researchers have been unable to adapt patient-derived cell lines for in vitro culture2. Recently, autopsy-derived melanoma lines and liquid biopsy-derived organoids were established and successfully propagated in mice, markedly expanding the portfolio of useful leptomeningeal metastasis models for both 2D and 3D in vitro screenings and in vivo studies30,148. Both approaches involved the use of culture media conditioned by meningeal cells, suggesting that secreted meningeal products are critical for survival and maintenance of leptomeningeal metastatic cells outside their native habitat.

The route of cancer cell delivery into the leptomeninges largely varies on the underlying question. Cancer cells as well as other agents can be delivered to leptomeninges via arterial blood, after intracardiac or intracarotid infusion. Direct access can be achieved through the cisterna magna, a subarachnoid cistern between cerebellum and medulla oblongata10,11. More invasive approaches include intracerebroventricular infusions that precisely reach the cerebral ventricles149,150. Arterial dissemination allows for observation and interference with the early steps of metastatic colonization. The inherent limitation of this setup is a priori assumption that leptomeninges are colonized arterially. Another disadvantage is metastases to sites other than the leptomeninges, a phenotype that can be to some extent salvaged by intracarotid route; however, the exact number of cells that will result in successful leptomeningeal metastasis will vary from animal to animal. To examine mechanisms that govern cancer cell growth within the leptomeningeal space, intracisternal delivery allows for a precise dosing of a known cancer cell number, critical for reproducible preclinical research10,66. A limitation of this route of delivery is the possible lack of systemic priming. Notably, in rodents, the CSF is drained through deep cervical lymph nodes, spreading cancer-derived antigens systemically, to prime the extra-leptomeningeal immune system9. To what extent is this system functional in models of animal leptomeningeal metastasis and more importantly humans remains unknown. Long-term experiments may also leverage from pump-based system or murine Ommaya reservoir, a port for feasible and repetitive ventricular access150,151.

Morphogens and cytokines

The development of the choroid plexus and the distinct meningeal layers is dictated by spatially and temporally organized gradients of morphogens and growth factors including WNT and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) family members67–69. Metastatic cells within other anatomic compartments repurpose these developmental signals to support their own growth both directly and indirectly while promoting the cancer stem cell phenotype70,71. It is therefore likely that such pathways re-emerge from the choroid plexus, leptomeningeal fibroblasts and the perivascular niches in the setting of leptomeningeal metastasis, accelerating dissemination and disease progression. Interestingly, genetic interruption of melanoma cell-derived TGFβ2 did not alter colonization and growth in leptomeninges72, suggesting a paracrine microenvironmental source. Because fibroblasts and other cells of mesenchymal origin are sources of TGFβ family ligands in other anatomic contexts, it is likely that leptomeningeal fibroblasts produce TGFβ36,73. The downstream consequences of this signalling for both the cancer cell and the surrounding microenvironment remain unexplored (Box 4).

Box 4 |. Basic and translational science approaches for leptomeningeal metastasis research in the multi-omic era.

The emergence and continued evolution of novel single-cell and spatial tools have revolutionized our capability to understand even minute aspects of biological processes. Well-designed rational combinations of such methods can undoubtedly lead to major breakthroughs in our understanding of leptomeningeal biology. Both experimental systems and ex vivo human samples can be subjected to nearly limitless profiling. Most advanced single-cell RNA-sequencing and analytic strategies already provide options for combined profiling of transcriptome, chromatin accessibility, surface proteome, T cell and B cell receptor sequencing as well as mitochondrial signals for lineage tracing of systems that are not feasibly manipulated with classical ‘bulk’ approaches152,153. Recent developments in single-cell proteomics provide unprecedented insights into the biology of leptomeningeal cancer cells and are of particular relevance in signalling systems with poor correlation between the transcript level and protein, for example, cytokines and their receptors. Analysis of bodily fluids can provide information about bulk proteome, metabolome and circulating DNA and RNA30,61. In tissues, preserving native architecture, combining metabolomics with a well-resolved spatial transcriptomic map of the brain and leptomeninges offers the possibility of capturing bi-directional communication between these seemingly isolated compartments. The analysis and integration of these outputs, however, require robust computational techniques that are in many cases still only being developed. Layering these complementary and orthogonal methods can result in a rich molecular roadmap that can be deconvoluted using traditional reductionist molecular biological approaches.

Metabolic nuances of the leptomeninges

In comparison with plasma and other bodily fluids, the CSF is hypoxic and contains sparse essential nutrients, including lipids, sugars, amino acids, nucleotides and microelements66,74,75. By contrast, CNS-specific small molecules including neurotransmitters and their metabolites accumulate within the fluid. This nutrient scarcity has been hypothesized to serve an antimicrobial role, further protecting the CNS. These low levels of vital nutrients and elevated levels of brain catabolites undoubtedly contribute to the unique microenvironment of the leptomeningeal space and have a major role in the profound microenvironmental selective pressure that these cells undergo within the space. In analogy to the interstitial fluid, the CSF micronutrient composition may also contribute to impaired immune cell function within this space76.

Although untransformed cells encountering nutritional stress must employ a pre-set series of transcriptional programmes in response to nutritional stress, cancer cells enjoy considerable epigenetic freedom and may use a variety of pre-existing programmes in response to metabolic stress77. These adaptations include remodelling the leptomeningeal environment to indirectly improve extracellular nutrients, increased nutrient uptake and scavenging and metabolic re-organization to make use of the unique metabolites present in the space11,74,78,79. In service of these goals, cancer cells repurpose a diverse array of programmes from other tissues and cell types. In turn, this cancer cell metabolic activity can subsequently trigger metabolic changes in other neighbouring cell types, such as meningeal fibroblasts or astrocytes, leading to metabolic reprogramming of the leptomeningeal space.

Standard clinical biochemical analyses together with more recent metabolomic studies provide clues about metabolic changes associated with metastatic infiltration of the leptomeninges. In the absence of disease, CSF glucose levels are maintained at approximately two-thirds to those of plasma glucose80. In the setting of bacterial meningitis, CSF glucose levels precipitously drop owing to impaired glucose transport in the choroid plexus epithelial cells81; this likely also occurs during leptomeningeal metastasis secondary to local inflammation. Decreased levels of glucose in CSF from patients with leptomeningeal metastasis have been observed for decades80,82. In a small study of patients harbouring leptomeningeal metastasis secondary to solid tumours, CSF glucose and lactate levels remained at less than normal levels, despite addition of intravenous glucose83. These glucose variations were accompanied by an increase in CSF lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, further supporting the hypoxic nature of the CSF84. LDH is an intracellular enzyme, released during plasma membrane rupture85. The exact reason for LDH release in leptomeningeal metastasis and its fate within the CSF is not known, but presumably this is a consequence of increased leukocyte death, local inflammation and excitotoxicity. In addition to elevations in CSF lactate, NMR-based metabolomics revealed elevated CSF levels of alanine and citrate and decreased levels of creatine and myo-inositol in the setting of leptomeningeal metastasis86. Metabolic studies examining glucose metabolism in leptomeningeal metastasis have correlated low CSF glucose levels with rising CSF lactate levels82,87. It is unclear whether this elevated CSF lactate is directly owing to cancer cell anaerobic metabolism; however, the plaques of disease on the brain and spine surface appear to rely on glycolysis, whereas the lethal, floating cancer fraction shows notably elevated levels of oxidative phosphorylation pathway components2. Formal establishment of the cell types driving these metabolic changes as well as the mechanism (mechanisms) underlying said changes is a clear area of investigation that has yet to be addressed. Moreover, because many classical chemotherapeutics are anti-metabolites, such work is expected to uncover novel therapeutic strategies, potentially enabling repurposing of currently available compounds88.

Numerous functions of monocytes and macrophages, such as production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and phagocytosis, rely on iron89. These cells employ an array of iron-transport systems with variable affinities to source sufficient amounts of this macroelement even in iron-poor sites, such as the CSF89. Leptomeningeal metastatic cancer cells, whose survival and metabolic activities also rely on iron, mimic this process and upregulate iron transporters downstream of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) promoters66. These cancer cells within the leptomeningeal space specifically express a high-affinity iron capture system, LCN2–SLC22A17, not employed by CSF macrophages, to outcompete these non-transformed cells for iron66. Consequently, macrophages impaired by environmental iron deficiency can no longer generate a respiratory burst, hampering their anticancer activities. Extracellular iron in this context represents a promising therapeutic target for leptomeningeal metastasis by restricting iron bioavailability. This concept is currently in translation in the form of a clinical trial (NCT05184816) that addresses intrathecal iron chelation as a novel therapeutic strategy against leptomeningeal metastasis90.

Evading the immune system

Early transplant experiments gave rise to the misleading dogma that the CNS represents an immune-privileged space91. This led to early, unsuccessful, attempts to treat leptomeningeal metastasis with intrathecal cytokines, even before widespread use of modern checkpoint blockade therapy92. It was later demonstrated that both the brain parenchyma and surrounding meninges are under constant immune surveillance, a feature essential for neurological and psychological function and homeostasis93,94. The CSF, however, is relatively sparsely populated by immune cells, with less than one immune cell per microlitre of CSF in the quiescent state10. Of these leptomeningeal immune cells, the vast majority are T cells10,95,96. This balance markedly changes in the presence of leptomeningeal metastasis, and the CSF becomes overpopulated by immune cells and contains elevated levels of numerous inflammatory mediators10,20,66,95 (Fig. 2). As such inflammation results in the breakdown of blood barriers, and it can also lead to CNS immune exposure to select endogenous and exogenous products in systemic circulation, altering CNS immune homeostasis33,97–99.

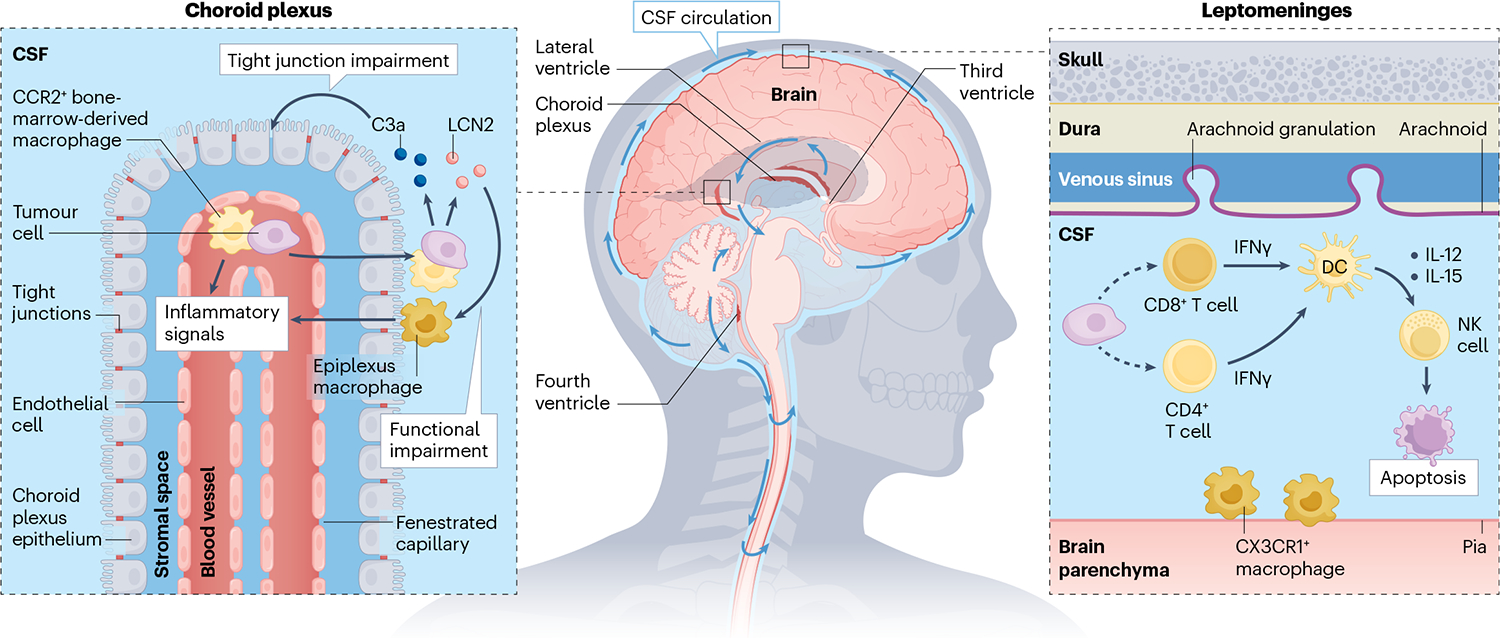

Fig. 2 |. Leptomeningeal immune response to cancer.

In the absence of malignancy, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is nearly acellular with few CD4+ T cells. Invasive cancer cells provoke a wide variety of inflammatory responses. Cancer cells generate the acute-phase reactants complement component 3 (C3) and lipocalin 2 (LCN2). C3 signalling reduces choroid plexus epithelial cell tight junction integrity, whereas LCN2 enables cancer cells to outcompete CSF macrophages for iron. CCR2+ bone-marrow-derived macrophages migrate into the leptomeninges where together with CX3CR1+-resident macrophages, they mediate anticancer activity. Leptomeningeal cancer cells recruit CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells; however, mechanisms for this remain unknown (as indicated by the dashed lines). CD8+ T and CD4+ T cells generate interferon-γ (IFNγ) in response to cancer cells, activating leptomeningeal dendritic cells. Dendritic cells generate IL-12 and IL-15 to prompt natural killer (NK) cells to initiate cancer cell apoptosis.

Metastasis-induced immune remodelling

Despite the abundance of immune cells and robust pro-inflammatory signalling associated with leptomeningeal metastasis, leptomeningeal immune cells are unable to control cancer growth10. The combined signals of nutrient-sparse CSF inflammation leads to functional impairment of, namely, macrophages, resulting in their inability to combat cancer cells and further immunosuppress this space10. The majority of macrophages in the leptomeningeal space in the context of leptomeningeal metastasis are infiltrating bone marrow-derived-CCR2+ macrophages10,100. In patients with melanoma, when compared with the inflammatory responses in the primary tumours or parenchymal brain metastases, the CSF bears cellular hallmarks of this immune suppression, characterized by abundant macrophages and depletion of lymphoid and dendritic cells60. Both the parenchyma and the skin are rendered immunosuppressive in the presence of melanoma; this is at least partially due to bona fide upregulation of immune checkpoints101,102. Initial reports suggest that the immuno-suppression observed in leptomeningeal metastasis is molecularly distinct from that of other sites. In mouse models of breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis, CD8+ T cells generated in the CSF-draining deep cervical lymph nodes displayed a Trp53-dependent senescent phenotype, downregulating the expression of adhesion receptor integrin α4β1 (also known as VLA4), rendering them unable to reach leptomeninges103.

The immunosuppressive nature of the leptomeninges may be representative of an evolutionarily conserved, protective mechanism preventing immune-mediated brain damage during peripheral immune reactions, given the limited regenerative capacity of the brain104,105. When these neuroimmune interactions become dysregulated, neurodegenerative processes can occur106–108. A known clinical phenomenon supports this argument. Infusion of chimeric antigen receptor T cells engineered to kill cells expressing certain antigens can result in neurological cytokine storm and neurotoxic side effects requiring clinical management109–111.

Immunomodulation and immune checkpoint therapy

Immunomodulators provide an attractive therapeutic approach to overcome leptomeningeal effector cell disarmament. IL-2 and interferon-α (IFNα) are two of the very first immunotherapies approved for clinical use. These were also tested quite early in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis92,112. Although both pleiotropic cytokines induced accumulation of immune infiltrate within the leptomeninges, clinical benefit was minimal and associated with profound neurotoxicity. In the case of intrathecal treatment with IFNα, severe permanent neurological and pathological changes were observed113–115. These observations highlight that the protective, immune-attenuating nature of the CSF is essential for the maintenance of neurological homeostasis. This notion sets some ground rules for the future generation of immune modulators. These need to be well tolerated after systemic, intrathecal or intraventricular delivery; they should not act upon non-immune cell types; and their action should be acute and transient rather than permanent. Preclinical approaches with virus-induced leptomeningeal IFNγ overexpression led to extended survival of leptomeningeal metastasis-bearing mice and rewiring of CSF immune spectrum towards beneficial myeloid cells10. These were observed in six different immune competent mouse models of breast, lung and melanoma leptomeningeal metastasis in two genetic backgrounds. Only minute changes in brain parenchyma composition were observed, specifically a subtle drop in IFNγ-sensitive oligodendrocyte numbers, with no notable signs of neurodegeneration116,117.

Immune checkpoint therapy (ICT) has shown promising results for treating parenchymal brain metastasis in patients with melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer metastases101,118. Although the use of ICT for leptomeningeal metastasis initially showed promising results119, formal phase II clinical trials120–122 demonstrated a minimal change in the overall survival for patients with leptomeningeal metastasis compared with historical values14. These mixed results suggest that this treatment approach is not entirely ineffective and that additional mechanistic work is required. The lack of well-defined, immunocompetent mouse models of leptomeningeal metastasis has impaired our ability to improve the utility of ICT for treating leptomeningeal metastasis. Moreover, it remains unclear whether it is possible or feasible to generate a spectrum of models that capture both ICT-sensitive and ICT-resistant phenotypes. Intriguingly, ICT can lead to transient immune system hyperactivation in a small subset of patients that results in sterile, ICT-associated meningitis, even in the absence of leptomeningeal metastasis123.

Transcriptomic and genomic analyses of CSF from patients with leptomeningeal metastasis systemically treated with either pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) alone or with combined ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4)–nivolumab (anti-PD-1) demonstrate increased proliferation of CD8+ T cell populations with effector features in the CSF124–126. This was accompanied by a transient elevation in IFNγ signalling and, consequently, an increase in antigen presentation signatures in multiple cell types. Under the pressure of ICT, tumour cells within the leptomeninges underwent adaptive selection leading to expansion of less-immunogenic clones. In the case of a single patient with leptomeningeal metastasis secondary to melanoma, an exceptional ICT response (survival more than 3 years) was observed after treatment with nivolumab alone, followed by whole brain radiotherapy, and then combinatorial ipilimumab–nivolumab, in the setting of sustained MEK–BRAF inhibition. This individual also showed elevated CSF levels of CD8+ effector memory T cells and dendritic cells60. Perhaps surprisingly, in response to leptomeningeal metastasis-induced INF-γ, leptomeningeal dendritic cells produce natural killer survival signals, such as IL-12 and IL-15, further supporting antitumour immunity10.

Although serial collection and analysis of other, parenchymal CNS malignancies require invasive, surgical approaches, leptomeningeal metastases may be collected serially through collection of CSF by lumbar puncture, an outpatient procedure that is well tolerated127. This straightforward approach allows for systems-level and omics-level analyses at human scale and provides insights into therapy-induced changes in response to therapy and enables biomarker discovery. These observational approaches demand development of immunocompetent mouse models of leptomeningeal metastasis to mechanistically dissect clinical observations.

Perspectives and conclusions

Basic and translational exploration of leptomeningeal metastasis holds the potential of significant clinical impact, as metastases to the leptomeningeal space result in disproportionate morbidity and rapid mortality. Understanding the mechanics of cancer spread to this seemingly isolated compartment paves the way for prophylactic interventions (Box 4). Similarly, identifying cancer cell molecular vulnerabilities and mechanistic dissection of cancer-exposed immune cell function within this compartment will enable discovery of novel clinical targets and CSF-specific immunomodulators. Examination of leptomeningeal metastasis-induced damage to the underlying parenchyma, resulting in cognitive impairment and neurological disability, enables rational interventions to improve quality of life for patients with leptomeningeal metastasis (Fig. 3).

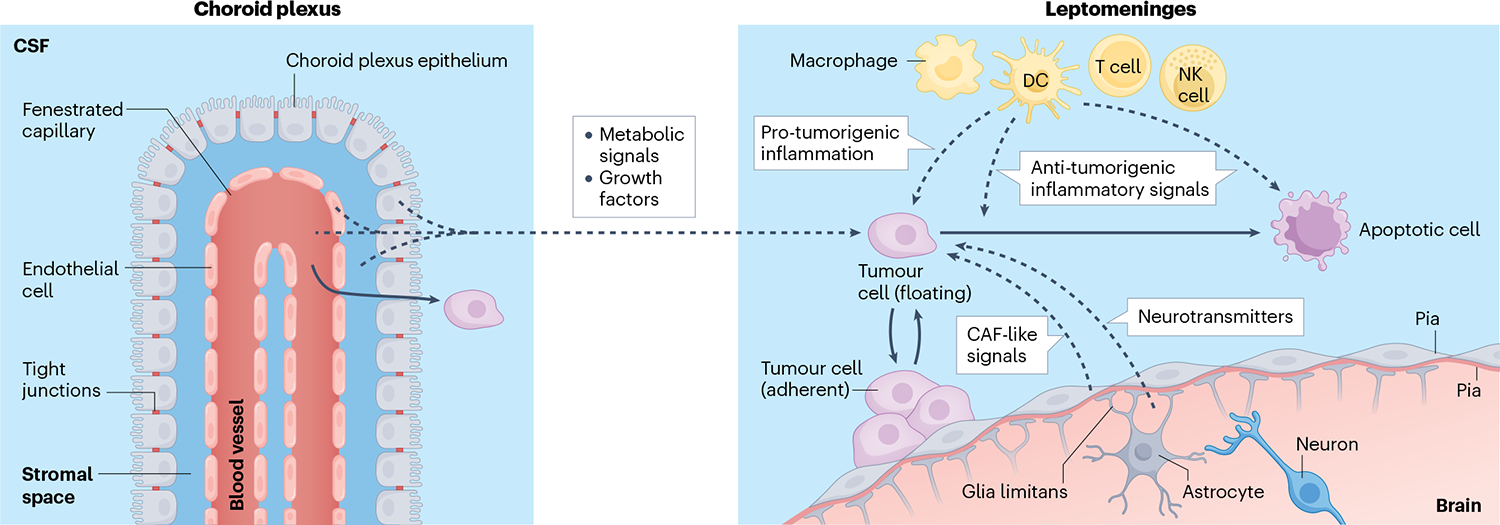

Fig. 3 |. Integration of microenvironmental signals by leptomeningeal immune cells.

Extensive profiling efforts of leptomeningeal metastasis suggest that cancer cells in this compartment receive a wide spectrum of extracellular signals. Although comprehensive work in this area has not yet been completed, several hypotheses can be envisioned such that cancer cell–microenvironmental interactions improve cancer cell growth within the nutrient-poor and inflamed leptomeninges. Signals supported through experimental evidence are indicated with solid arrows, and those hypothesized are indicated with dashed arrows. Cancer cells within the leptomeningeal space exist in an equilibrium between adherent and floating states receiving various local signals. In response to local inflammation, choroid plexus epithelial cells lose barrier function, enabling transport of nutrients and growth factors from the blood, stroma, endothelium and epithelium into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), supporting cancer growth. Infiltrating leukocytes also promote tumour growth through induction of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathways in the cancer cell66. By contrast, these inflammatory signals can also induce cancer cell death. Pial and arachnoid fibroblasts may alter their secretome in response to cancer within the space, potentially taking on a cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-like role. Finally, the homeostasis of the brain parenchyma is likely perturbed by leptomeningeal metastasis promoting the accumulation of neurotransmitters and their metabolites within the local microenvironment. DC, dendritic cell; NK cell, natural killer cell.

Although most metastasis-preventive strategies may appear challenging to implement, there is precedent for such an approach. Treatment of subpopulations of patients with lymphoma at risk for CNS metastasis with prophylactic anti-CD20 therapies and increased CNS surveillance resulted in reduced CNS metastasis and improved survival128. In brief, identification of tumours at high risk for leptomeningeal metastasis is critical; however, methods for this are still lacking. One possibility is a tumour-centric approach; analysis of the transcriptome or methylome of the primary tumour, in tandem with cell-free RNA and DNA profiling of the CSF of the patient, could identify at-risk populations. Alternatively, focusing on the microenvironment, CSF could be profiled by advanced flow cytometry10 to identify subtle changes within the leptomeninges before the onset of overt leptomeningeal metastasis. Both approaches offer the possibility of identifying patients before the onset of neurological signs and symptoms (Box 1). Because neurological symptoms are unlikely to resolve, even after successful treatment, knowledge gained from these approaches holds the promise of substantially improving quality of life of patients. Similarly, elimination of early seeding holds the potential to prevent neurological damage and markedly improve patient outcomes. The pathways essential for leptomeningeal colonization remain unknown, but studies from other organs may serve as an example129–131. It is also possible that the increasing use of systemic immunotherapy for both therapeutic and preventive purposes may also eliminate early, clinically silent leptomeningeal seeds.

Although this Review has focused on the leptomeningeal compartment, it cannot be overlooked that the leptomeninges represent a critical conduit for biochemical communication. Identification of neurotransmitters, catabolites and other metabolites essential to support cancer cell growth within the leptomeninges will also likely identify molecular mediators of cancer cell interactions with the underlying parenchyma, providing insight into neurological dysfunction associated with leptomeningeal metastasis132. The leptomeninges also capture communication between the CNS and the systemic circulation; thus future work should address how the larger organism responds to cancer within the leptomeninges133. Understanding this biochemical communication between the leptomeninges and the systemic circulation has the potential to improve clinical management of various neurological complications of cancer and paraneoplastic syndromes134–136.

Previously deemed a hopelessly chaotic end-stage complication of cancer, leptomeningeal metastasis is increasingly appreciated as a microcosm of cancer biology principles and a ripe area for study. Leptomeningeal metastasis demonstrates the evolutionary dynamics of cancer, the selective pressures generated by scarce nutrients and the essential role of the immune system. Technological advances including the application of multi-omic techniques to the CSF, novel mechanistically tractable mouse models and computational power sufficient to manage the resulting massive data sets have collectively empowered a resurgence of interest in the study of leptomeningeal metastasis. Applying modern molecular systems biology and computational oncology approaches to long-established clinical observations holds the potential to unravel the molecular and neuroanatomic basis for this complex disease process, enabling rational therapeutic targeting and improved clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge their patients who inspire this work, their mentors who have provided the tools to carry out this research and the philanthropic and governmental sources that enable experimental work in their laboratories. This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant NCI P30 CA008748.

Glossary

- Acute phase reactants

A group of proteins that are markedly elevated in the plasma during acute and chronic inflammation

- Arachnoid mater

The upper layer of leptomeninges composed of a fibroblastoid network of cells connected to the pia mater by a series of fibrous strands

- Brain’s four ventricles

A system of interconnected cerebrospinal fluid-filled cavities within the brain

- Bridging vessels

Veins that extend from the brain parenchyma to the subdural space

- Cauda equina

Spinal nerve roots that extend beyond the terminus of the spinal cord, transmitting motor and sensory information to the bowel, bladder and lower limbs

- Cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF). A colourless, paucicellular fluid that surrounds the brain and the spinal cord

- Choroid plexuses

Specialized, cerebrospinal fluid-secreting structures within the ventricular system, composed of a blood vessel network, surrounded by a fibroblast and extracellular matrix-rich stroma and encircled by specialized polarized, secretory epithelial cells

- Ependyma

A layer of polarized, secretory neuroepithelial cells, lining the cerebral ventricles and spinal central canal, capable of cerebrospinal fluid production

- Ferroptosis

A molecularly distinct type of cell death classically resulting from interactions between iron and lipids to generate reactive oxygen species

- Liquid biopsy

Analysis of the tumour-derived material in easily accessed body fluids, including blood, urine or cerebrospinal fluid

- Paraneoplastic syndromes

A rare complication of cancer whereby the immune system attacks normal neural tissues causing neurological symptoms such as seizures, dementia, loss of coordination and sensory disturbances

- Pia mater

A fibroblastoid monolayer of cells that make up the innermost layer of the leptomeninges

- Posterior fossa

The lower portion of the cranial cavity that houses the cerebellum, pons and medulla oblongata

- Subarachnoid space

Cerebrospinal fluid-filled compartment between the arachnoid and pial membranes, surrounding the brain and the spinal cord

Footnotes

Competing interests

J.R. and A.B. are inventors on the provisional US patent applications 63/449,817 and 63/449,823 and international patent application PCT/US24/18343. A.B. holds an unpaid position on the scientific advisory board for Evren Scientific and is an inventor on the US patents 62/258,044, 10/413,522 and 63/052,139.

References

- 1.Vanderah TW & Gould DJ Nolte’s the Human Brain : An Introduction to its Functional Anatomy 8th edn (Elsevier, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remsik J et al. Leptomeningeal metastatic cells adopt two phenotypic states. Cancer Rep. 5, e1236 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subira D et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of flow cytometry immunophenotyping in patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 32, 383–391 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott BJ & Kesari S Leptomeningeal metastases in breast cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res 3, 117–126 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magbanua MJ et al. Molecular profiling of tumor cells in cerebrospinal fluid and matched primary tumors from metastatic breast cancer patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer Res. 73, 7134–7143 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baruch K et al. CNS-specific immunity at the choroid plexus shifts toward destructive Th2 inflammation in brain aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 2264–2269 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shechter R et al. Recruitment of beneficial M2 macrophages to injured spinal cord is orchestrated by remote brain choroid plexus. Immunity 38, 555–569 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cugurra A et al. Skull and vertebral bone marrow are myeloid cell reservoirs for the meninges and CNS parenchyma. Science 373, eabf7844 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louveau A et al. CNS lymphatic drainage and neuroinflammation are regulated by meningeal lymphatic vasculature. Nat. Neurosci 21, 1380–1391 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remsik J et al. Leptomeningeal anti-tumor immunity follows unique signaling principles. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2023.03.17.533041 (2023). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boire A et al. Complement component 3 adapts the cerebrospinal fluid for leptomeningeal metastasis. Cell 168, 1101–1113.e13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article shows that leptomeningeal cancer cells actively remodel the blood–CSF barrier to increase the flux of mitogens and nutrients.

- 12.Li YS et al. Leptomeningeal metastases in patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol 11, 1962–1969 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carausu M et al. Breast cancer patients treated with intrathecal therapy for leptomeningeal metastases in a large real-life database. ESMO Open 6, 100150 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain MC Leptomeningeal metastasis. Semin. Neurol 30, 236–244 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Jimenez F et al. Pan-cancer whole-genome comparison of primary and metastatic solid tumours. Nature 575, 210–216 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priestley P et al. Pan-cancer whole-genome analyses of metastatic solid tumours. Nature 575, 210–216 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen B et al. Genomic characterization of metastatic patterns from prospective clinical sequencing of 25,000 patients. Cell 185, 563–575.e11 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta K & Jeong J Developmental biology of the meninges. Genesis 57, e23288 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YY, Tien RD, Bruner JM, De Pena CA & Van Tassel P Loculated intracranial leptomeningeal metastases: CT and MR characteristics. Am. J. Neuroradiol 10, 1171–1179 (1989). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordone I et al. Overexpression of syndecan-1, MUC-1, and putative stem cell markers in breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis: a cerebrospinal fluid flow cytometry study. Breast Cancer Res. 19, 46 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilcox JA, Li MJ & Boire AA Leptomeningeal metastases: new opportunities in the modern era. Neurotherapeutics 10, 1782–1798 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang JT et al. Randomized phase II trial of proton craniospinal irradiation versus photon involved-field radiotherapy for patients with solid tumor leptomeningeal metastasis. J. Clin. Oncol 40, 3858–3867 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S et al. A phase II, multicenter, two cohort study of 160 mg osimertinib in EGFR T790M-positive non-small-cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases or leptomeningeal disease who progressed on prior EGFR TKI therapy. Ann. Oncol 31, 1397–1404 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tolaney SM et al. A phase II study of abemaciclib in patients with brain metastases secondary to hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 26, 5310–5319 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oberkampf F et al. Phase II study of intrathecal administration of trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer with leptomeningeal metastasis. Neuro Oncol. 25, 365–374 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glitza Oliva IC et al. Concurrent intrathecal and intravenous nivolumab in leptomeningeal disease: phase 1 trial interim results. Nat. Med 29, 898–905 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Rhun E et al. Intrathecal liposomal cytarabine plus systemic therapy versus systemic chemotherapy alone for newly diagnosed leptomeningeal metastasis from breast cancer. Neuro Oncol. 22, 524–538 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kokkoris CP Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. How does cancer reach the pia-arachnoid? Cancer 51, 154–160 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson ME, Chernik NL & Posner JB Infiltration of the leptomeninges by systemic cancer. A clinical and pathologic study. Arch. Neurol 30, 122–137, (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzpatrick A et al. Genomic profiling and pre-clinical modelling of breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis reveals acquisition of a lobular-like phenotype. Nat. Commun 14, 7408 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides evidence for early clonal divergence of leptomeningeal metastatic cells.

- 31.Zhao L, Taso M, Dai W, Press DZ & Alsop DC Non-invasive measurement of choroid plexus apparent blood flow with arterial spin labeling. Fluids Barriers CNS 17, 58 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lun MP, Monuki ES & Lehtinen MK Development and functions of the choroid plexus–cerebrospinal fluid system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 16, 445–457 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carloni S et al. Identification of a choroid plexus vascular barrier closing during intestinal inflammation. Science 374, 439–448 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study investigates the choroid plexus vascular barrier that responds to intestinal inflammation via microbiota-derived stimuli.

- 34.Garzia L et al. A hematogenous route for medulloblastoma leptomeningeal metastases. Cell 172, 1050–1062.e14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows that medulloblastoma, a primary childhood tumour, can colonize leptomeninges via haematogenous dissemination.

- 35.Moberg A & von R Carcinosis meningum. Acta Med. Scand 170, 747–755 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kearns NA et al. Dissecting the human leptomeninges at single-cell resolution. Nat. Commun 14, 7036 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iliff JJ et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci. Transl Med 4, 147ra111 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article describes the function of glymphatics, a system allowing an exchange of CSF and interstitial fluid.

- 38.Dasgupta A, Moraes FY, Rawal S, Diamandis P & Shultz DB Focal leptomeningeal disease with perivascular invasion in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Am. J. Neuroradiol 41, 1430–1433 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jonart LM et al. Disrupting the leukemia niche in the central nervous system attenuates leukemia chemoresistance. Haematologica 105, 2130–2140 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Sevilla LM et al. The choroid plexus stroma constitutes a sanctuary for paediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in the central nervous system. J. Pathol 252, 189–200 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akers SM, Rellick SL, Fortney JE & Gibson LF Cellular elements of the subarachnoid space promote ALL survival during chemotherapy. Leuk. Res 35, 705–711 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao H et al. Leukaemia hijacks a neural mechanism to invade the central nervous system. Nature 560, 55–60 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides a mechanism of leukaemia CNS colonization along the vessels that are passing between vertebral and calvarial bone marrow and the subarachnoid space.

- 43.Amit M, Na’ara S & Gil Z Mechanisms of cancer dissemination along nerves. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 399–408 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez-Vitale JC & Garcia-Bunuel R Meningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer 37, 2906–2911 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng Q et al. Synaptic proximity enables NMDAR signalling to promote brain metastasis. Nature 573, 526–531 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venkataramani V et al. Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature 573, 532–538 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venkatesh HS et al. Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature 573, 539–545 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martirosian V et al. Medulloblastoma uses GABA transaminase to survive in the cerebrospinal fluid microenvironment and promote leptomeningeal dissemination. Cell Rep. 35, 109302 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ubellacker JM et al. Lymph protects metastasizing melanoma cells from ferroptosis. Nature 585, 113–118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Louveau A et al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523, 337–341 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahn JH et al. Meningeal lymphatic vessels at the skull base drain cerebrospinal fluid. Nature 572, 62–66 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aspelund A et al. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J. Exp. Med 212, 991–999 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whiteley A, Price T, Simon B, Xu K & Sipkins D Neuronal mimicry promotes breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis from bone marrow. Cancer Res. 82, 3848 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geldof AA Models for cancer skeletal metastasis: a reappraisal of Batson’s plexus. Anticancer Res. 17, 1535–1539 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahn JH et al. Risk for leptomeningeal seeding after resection for brain metastases: implication of tumor location with mode of resection. J. Neurosurg 116, 984–993 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tewarie IA et al. Leptomeningeal disease in neurosurgical brain metastases patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurooncol. Adv 3, vdab162 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norris LK, Grossman SA & Olivi A Neoplastic meningitis following surgical resection of isolated cerebellar metastasis: a potentially preventable complication. J. Neurooncol 32, 215–223 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Ree TC et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis after surgical resection of brain metastases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 66, 225–227 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horng S et al. Astrocytic tight junctions control inflammatory CNS lesion pathogenesis. J. Clin. Invest 127, 3136–3151 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smalley I et al. Single-cell characterization of the immune microenvironment of melanoma brain and leptomeningeal metastases. Clin. Cancer Res 27, 4109–4125 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article dissects the tumour–immune system interactions in primary melanoma biopsies and melanoma parenchymal and leptomeningeal metastasis.

- 61.Smalley I et al. Proteomic analysis of CSF from patients with leptomeningeal melanoma metastases identifies signatures associated with disease progression and therapeutic resistance. Clin. Cancer Res 26, 2163–2175 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeAngelis LM, Posner JB & Posner JB Neurologic Complications of Cancer 2nd edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spreafico F et al. Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid from children with central nervous system tumors identifies candidate proteins relating to tumor metastatic spread. Oncotarget 8, 46177–46190 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Markiewski MM et al. Modulation of the antitumor immune response by complement. Nat. Immunol 9, 1225–1235 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morgan BP & Harris CL Complement, a target for therapy in inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 14, 857–877 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chi Y et al. Cancer cells deploy lipocalin-2 to collect limiting iron in leptomeningeal metastasis. Science 369, 276–282 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DeSisto J et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses of the developing meninges reveal meningeal fibroblast diversity and function. Dev. Cell 54, 43–59.e4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides a comprehensive atlas of embryonic leptomeningeal fibroblasts, dissected at the molecular level, layer by layer.

- 68.Dani N et al. A cellular and spatial map of the choroid plexus across brain ventricles and ages. Cell 184, 3056–3074.e21 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides a location-based atlas of mouse choroid plexi, from embryogenesis to ageing.

- 69.Snyder J, Remsik J, Prescott N & Boire A Mimicking CAFs, pial cells support leptomeningeal metastasis. Cancer Res. 83, 1190 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ganesh K et al. L1CAM defines the regenerative origin of metastasis-initiating cells in colorectal cancer. Nat. Cancer 1, 28–45 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ye X et al. Distinct EMT programs control normal mammary stem cells and tumour-initiating cells. Nature 525, 256–260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang C, Zhang F, Tsan R & Fidler IJ Transforming growth factor-beta2 is a molecular determinant for site-specific melanoma metastasis in the brain. Cancer Res. 69, 828–835 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson MD, Gold LI & Moses HL Evidence for transforming growth factor-beta expression in human leptomeningeal cells and transforming growth factor-beta-like activity in human cerebrospinal fluid. Lab. Invest 67, 360–368 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferraro GB et al. Fatty acid synthesis is required for breast cancer brain metastasis. Nat. Cancer 2, 414–428 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spector R, Robert Snodgrass S & Johanson CE A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: focus on adult humans. Exp. Neurol 273, 57–68 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khaled M et al. Branched-chain keto acids exert an immune-suppressive and neurodegenerative microenvironment in CNS leptomeningeal lymphoma. Cancer Res. 83, 1192 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moorman AR et al. Progressive plasticity during colorectal cancer metastasis. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2023.08.18.553925 (2023). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bergers G & Fendt SM The metabolism of cancer cells during metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 162–180 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lumaquin-Yin D et al. Lipid droplets are a metabolic vulnerability in melanoma. Nat. Commun 14, 3192 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fishman R Cerebrospinal Fluid in Diseases of the Nervous System 2nd edn (Saunders, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Severien C, Jacobs KH & Schoenemann W Marked pleocytosis and hypoglycorrhachia in coxsackie meningitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J 13, 322–323 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kang SJ et al. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid level of carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatous metastasis. J. Clin. Neurol 6, 33–37 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jann S, Comini A & Pellegrini G Hypoglycorrhachia in leptomeningeal carcinomatosis: a pathophysiological study. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci 9, 83–88 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cacho-Diaz B et al. Lactate dehydrogenase as a prognostic marker in neoplastic meningitis. J. Clin. Neurosci 51, 39–42 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Legrand C et al. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity of the cultured eukaryotic cells as marker of the number of dead cells in the medium [corrected]. J. Biotechnol 25, 231–243 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.An YJ et al. An NMR metabolomics approach for the diagnosis of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in lung adenocarcinoma cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 136, 162–171 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bonig L et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis: the role of cerebrospinal fluid diagnostics. Front. Neurol 10, 839 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schmidt DR et al. Metabolomics in cancer research and emerging applications in clinical oncology. CA Cancer J. Clin 71, 333–358 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Soares MP & Hamza I Macrophages and iron metabolism. Immunity 44, 492–504 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05184816 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Medawar PB Immunity to homologous grafted skin; the suppression of cell division in grafts transplanted to immunized animals. Br. J. Exp. Pathol 27, 9–14 (1946). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Herrlinger U, Weller M & Schabet M New aspects of immunotherapy of leptomeningeal metastasis. J. Neurooncol 38, 233–239 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ziv Y et al. Immune cells contribute to the maintenance of neurogenesis and spatial learning abilities in adulthood. Nat. Neurosci 9, 268–275 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Norris GT & Kipnis J Immune cells and CNS physiology: microglia and beyond. J. Exp. Med 216, 60–70 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Subira D et al. Role of flow cytometry immunophenotyping in the diagnosis of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Neuro Oncol. 14, 43–52 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schafflick D et al. Integrated single cell analysis of blood and cerebrospinal fluid leukocytes in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Commun 11, 247 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morais LH, Schreiber HLT & Mazmanian SK The gut microbiota–brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 19, 241–255 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhu X et al. Dectin-1 signaling on colonic gammadelta T cells promotes psychosocial stress responses. Nat. Immunol 24, 625–636 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dulken BW et al. Single-cell analysis reveals T cell infiltration in old neurogenic niches. Nature 571, 205–210 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haviv D et al. The covariance environment defines cellular niches for spatial inference. Nat. Biotechnol 10.1038/s41587-024-02193-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tawbi HA et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N. Engl. J. Med 379, 722–730 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hamid O et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma who had initial stable disease with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001 and KEYNOTE-006. Eur. J. Cancer 157, 391–402 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li J et al. VLA-4 suppression by senescence signals regulates meningeal immunity and leptomeningeal metastasis. eLife 11, e83272 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eriksson PS et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat. Med 4, 1313–1317 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Benhar I, London A & Schwartz M The privileged immunity of immune privileged organs: the case of the eye. Front. Immunol 3, 296 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bettcher BM, Tansey MG, Dorothee G & Heneka MT Peripheral and central immune system crosstalk in Alzheimer disease — a research prospectus. Nat. Rev. Neurol 17, 689–701 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ellrichmann G, Reick C, Saft C & Linker RA The role of the immune system in Huntington’s disease. Clin. Dev. Immunol 2013, 541259 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]