Abstract

People with disabilities often experience worse health outcomes than ordinary people because of multiple barriers to accessing healthcare. These inequalities are particularly exposed during the pandemic, indicating an urgent need to strengthen health systems, so that they are inclusive and responsive to the needs of these people during crises. These people are particularly affected by changes in routine services because of diversion of healthcare staff and facilities to respond to the pandemic, e.g., rehabilitation and medications. The combination of these factors substantially imparts negative impacts on their functioning and well-being. Health services research can help address the challenges of maintaining continuity of care during crises as well as addressing systematic inequalities in the health sector that marginalize people with disabilities even during noncrisis times. Therefore, research is needed to understand the health service design and to identify strategies to maximize active participation from this population.

Keywords: Pandemic, disability, mental health, rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).[1] People with disability refers to the individuals who require assistance or care, e.g., because they have a disability (physical, mental, or psychological) or because of unfamiliar conditions such as because of pregnancy. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) defines disability as an umbrella term for “impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions.”[2] Persons with disabilities (PwDs) include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments, and resultingly, they are unable to effectively participate and interact with the society on equal basis.[3]

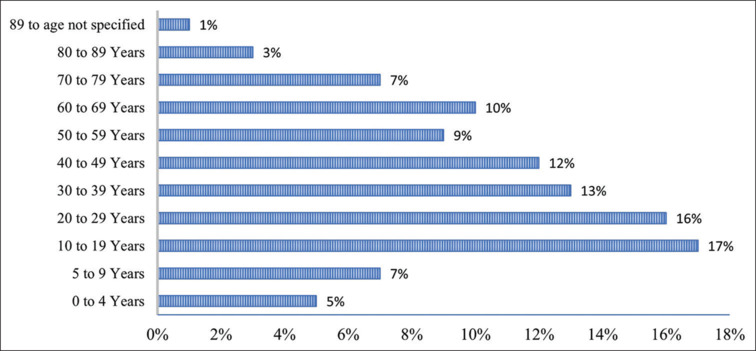

The world report on disability[4] reported that an estimated 1.3 billion people—about 16% of the global population—currently experience significant disability and 15.6% of the global population aged 15 years and older have been living with some form of disability, of whom 2-4% had significant functional impairments and disabilities. In India, about 2.1% of the total population are having some kind of disability[5] as discussed in Table 1. Among the total disabled in the country, 15 million are males, and 12 million are females, as of Aug 2021. The disability in movement at 20.3% emerges as the top category. Others in sequence are in hearing (18.9%) and in seeing (18.8%), whereas younger ones are more prone to disability, as indicated in Figure 1.

Table 1:

Number of disabled population and type of disability in India

| Population | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 1,210,854,977 | 100.0 |

| Total disabled population | 26814994 | 2.21 |

| Type of disability | ||

| (a) In seeing | 5033431 | 0.4 |

| (b) In speech | 1998692 | 0.2 |

| (c) In hearing | 5072914 | 0.4 |

| (d) In movement | 5436826 | 0.4 |

| (e) Mental | 2228844 | 0.2 |

| (f) Any other | 4927589 | 0.4 |

| (g) Multiple disability | 2116698 | 0.2 |

Source: Census of India 2011[6]

Figure 1.

Agewise distribution of PwDs in India[6]

A pandemic is defined as the occurrence of an illness in excess of its normal expectancy across a wide geographical area, crossing international borders.[7] These large-scale outbreaks of infectious diseases subsequently lead to an increase in mortality and morbidity globally and have a significant effect on the economic, social, and political situations in the affected countries. The mortality rates become even disproportionately higher among low- and middle-income countries.[8] Pandemic crisis has overwhelmed health systems across the world in recent years, and it has become an emerging and rapidly budding condition with adverse outcomes of unprecedented magnitude. The dimensions of a pandemic comprise the mechanism and pattern of disease transmission, the severity and magnitude of infection outbreak, and the differentiability of the associated morbidities.[9]

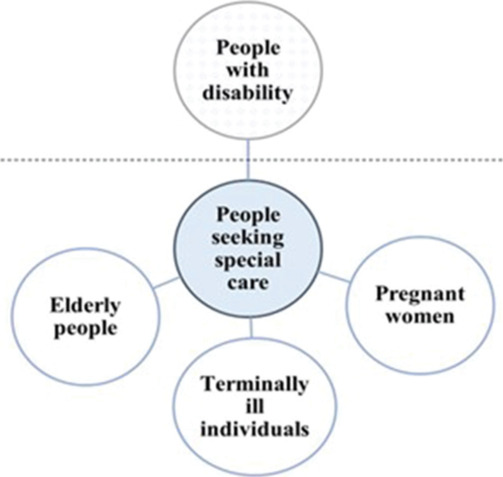

People with disabilities, including persons with functional impairments (PwDs and FI), and geriatric, terminally ill individuals are either socially marginalized or may face unique health challenges and are one of the most vulnerable groups requiring special care during disasters and pandemic-like situations [Figure 2]. Pandemic crisis situations pose difficult challenges for them including psychological, physical (hygiene and transfer of infection), financial, transportation-associated challenges, and those related to the infrastructure.[8] Constrained access to services and facilities is their key obstacle because of their social, economic, physical, sensory, and cognitive limitations, which require utmost care and handholding during the crisis.[10] Thus, there is an urgent requirement to address the unique vulnerabilities of disabled people, their families, and caretakers, which occur during any pandemic-like emergency situation because of their pre-existing disability and associated health issues.

Figure 2.

Individuals falling under the category of people seeking special care (in addition to people with disability)

Therefore, the prime focus of the present article is the identify challenges faced by disabled persons and their reliance on assistive aids, families, doctors, and caregivers during a pandemic scenario. Along with that, certain actions and measures to overcome these barriers at various levels have also been discussed further.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

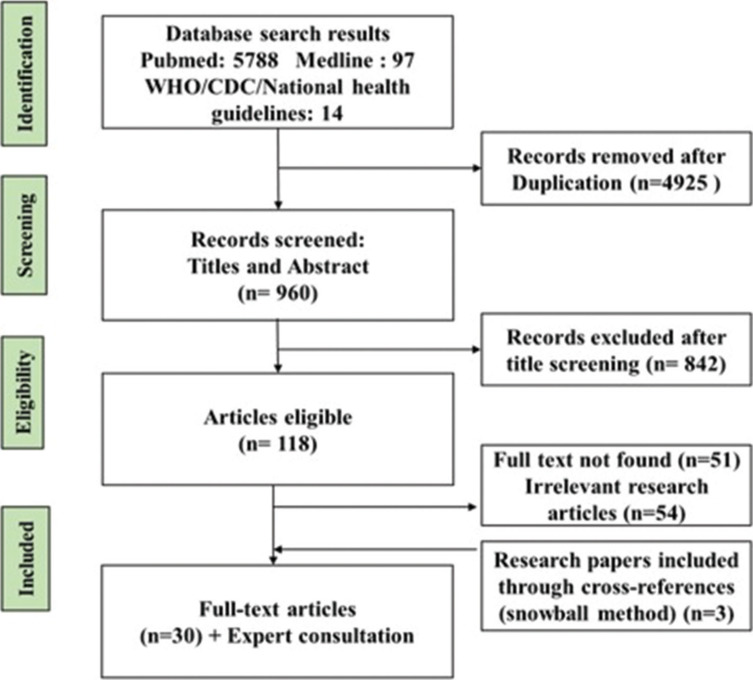

This study was comprehensively conducted to identify the challenges faced by disabled individuals and strategies to identify measures to address the problems arising during any pandemic situation. Hence, a comprehensive literature search was performed using several databases and search engines, such as MedlinePlus (NLM) and PubMed databases [Figure 3]. The search incorporated keywords such as “((disabled) AND (pandemic)),” “(geriatric population) AND (pandemic),” “(terminally ill) AND (pandemic),” and so on. To identify additional relevant articles, backward and forward snowballing method was adopted. The review extensively studied published research articles, book chapters, case reports, policy documents, national health authority guidelines and advisories, and press releases from international health organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which focus on disability and pandemic since 2001 up to March 2023, because presently, there are numerous guidance documents and advisories are available, which have been released by national and international agencies.

Figure 3.

PRISMA search strategy for studies included for review

To identify relevant literature and to ensure a thorough review, various selection criteria were applied to the searched literature. Inclusion criteria were (i) articles describing disability during pandemic, (ii) published gray literature (national health regulatory bodies’ advisories, press releases, and reports from international health organizations), (iii) articles published in English only, and (iv) articles published during 2001-2023. Exclusion criteria were (i) studies providing information that are not of interest, (ii) literature with irrelevant information, (iii) non–peer-reviewed articles, and (iii) articles for which full text is not available.

A multitier screening method was applied, to exclude the articles and documents that were out of context. The remaining articles underwent an in-depth review by three independent investigators specializing in the fields of public health, basic medical science, and biotechnology. The approach provided a rigorous and thorough analysis of the content through an interdisciplinary viewpoint.

This review critically discussed the issues faced by people with disability, geriatric population, and terminally ill individuals and recommendations to increase accessibility of the available resources for these population during a crisis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Literature search

Primarily PubMed and MedlinePlus databases were explored for searching relevant articles with the time filter to extract the literature published after 2001. As a result, a total of 5788 articles were identified through initial searching after removing duplicate articles, 118 articles met the eligibility criteria after title and abstract screening, and finally, 16 articles with 14 guidelines from various health agencies were identified for inclusion in this review. Figure 3 demonstrates the PRISMA search strategy of the shortlisted studies. Furthermore, an expert consultation meeting was conducted including professional dedicated in the field of physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychology, psychiatry, sociobehavioral, and public health, and their experience and suggestions were also recorded.

Barriers to health system response for person with disability

Several pandemics have occurred in India during 2001-2023, e.g., SARS (2002-2004), dengue and chikungunya (2006), swine flu (2014-2015), and coronavirus (2019).[11] Healthcare response and management for disabled persons in a pandemic-like situation has several barriers at different levels starting from self-challenges to issues at hospitals, at home with families, and with their caregivers.

Key challenges of healthcare delivery related to person with disability

Awareness

Availability of caretakers, assistive products

Affordability issues because of raised costs

Accessibility of general services

Acceptability of the changed situation

Self-challenges faced by individuals with disability during pandemics

The issues faced by disabled people during pandemics include lack of awareness, appropriate environment, psychological factors and stigma, inaccessibility and dependency on assistive products in public places and/or at home, along with poor availability and prohibitive costs of customized services and products, and scarcity of trained workforce among service providers, and because of the actions taken to combat a pandemic, such as physical distancing, lockdown, and restriction on movement, the problems are further elevated, and these people become more distant from their communities and support system.[12]

For example, it has been observed during COVID-19 crisis also that the pandemic situation led to increased irritability and temper tantrums among children and adolescents with disabilities (CwDs).[13] For individuals with hearing devices, masks and PPE are barriers to communication because it affects acoustic transmission and reduces sign language and lip reading. Moreover, these persons find complications in surviving under new environments, maintaining physical distancing, and might need greater assistance in their day-to-day life in such situations.

On the other hand, elderly people with disabilities hailing from underprivileged homes generally encounter financial problems and absence of basic facilities such as nutrition, medication, emergency care, and hygiene practices during such crises. There is an increased risk of health problems including loss of range of motion, increased stiffness, after sitting or lying down for long, memory issues, anxiety, disturbed/poor quality sleep, delayed thought processing, and reduced coordination. Aging population also face the additional challenge of lack of technology knowledge to connect with their friends or family members making them more vulnerable for adverse effects. Also, there have been more number of cases of violence, abuse, and neglect against people with disability during social isolation because of disruption in routine, which may lead to loneliness and sense of bereavement among elderly with disability.[14]

Maintaining self-hygiene and assistive care

People with disability often encounter issues in maintaining personal hygiene because of their limited physical accessibility. Along with this, the assistive and adaptive devices are important aids for improving their independence and productivity. These devices working as aids to enable persons with disability in performing specific functions such as mobility, communication, and their routine activities are at higher risk of catching infection as these devices are in contact with the external environment and might be exposed to infectious agents.[15] Devices such as hearing aids, ventilators, and spectacles are in direct contact with the entry points of the body, e.g., eyes, mouth, and nose, putting the users at a higher risk of getting infected compared with others. Also, the larger mobility devices such as wheelchair, walkers, canes, and artificial lower limbs have continuous direct contact with the ground and thus could get exposed to infection more easily.

The elderly people are also more difficult to manage physically by their caregivers, and many additional problems related to urination or defecation increase their requirements. Apart from these issues, irritability or anger, disturbed and less sleep, loss of appetite or food refusal, unwillingness to remain alone even for a short duration, etc., are other common issues with geriatric people and terminally ill people.

Mental health issues

Mental issues during a pandemic situation can be understood as pre-existing issues, as well as those which may have arisen because of the pandemic crisis, such as alarming news bulletins, fear of or actual bereavement, injury to self or family members, life-threatening circumstances, panic, separation from family members, no friends, and lower household income further exacerbate the existing challenges. If the person with mental illness (PwMI) also gets infected, then the stigma and fear increase manifold, which leaves them alone and terrified during such crisis.[16] As a result, a few symptoms of mental stress such as difficulty in comprehending, anxiety, uncertainty, mood swings, grief, mourning over the past, irritability, sleep issues, depression, loneliness, decreased appetite, tension of falling ill, inability to survive (giving up), helplessness to perform routine responsibilities, or daily-life activities are also faced by these people. Since they are socially marginalized and economically dependent, they may have additional thoughts of being a burden, being of no use to anyone, being alone, abandonment, and fear of not being provided with essential care or medical supplies in case of emergency.[17] Those who are working might also have worrisome thoughts about their job security and financial condition, which might also lead to their inclination toward other abuses including tobacco, alcohol, or other hard drugs.

Challenges faced by the families of disabled persons

Disability among individuals leads to added challenges for their families because the magnitude of dependency on others among disabled people is high and depends on the type of disability, age group of the disabled person, and the type of family setup.[18] There is emotional as well as financial burden associated with caring for such people for their families which gets many folds aggravated during pandemics.[19] Despite several provisions to support education, health, and security of a person with disability laid by several welfare organizations and policy-making bodies, gathering the information of these services and programs and the entire procedure to procure such services are another major barriers faced by families. This becomes a tedious task because there are several other responsibilities that need to be worked on by the families in addition to taking care of the disabled person. The pandemic situation causes disruption in routine and also leads to drain of physical and emotional energy of the family members along with the disabled because of which they may easily get involved in conflict, which may result in increased struggle for both, the person with disability and their family.[20]

Living with stigma: A challenge for disabled persons in the community

Persons with disabilities often face labeling, name-calling, stereotyping, and discrimination from the community, and consequently, their families may also suffer from societal stigma.[21] Health inequities arise from unfair conditions faced by persons with disabilities, including stigma, discrimination, poverty, exclusion from education and employment, and barriers faced in the health system itself. The world report of disability[4] highlighted that women with disabilities experienced gender discrimination along with disabling issues that create barrier in education, employment, healthcare facilities, and social participation. For example, in schools, the attitude of other children and school staff affect the inclusion of CwDs in mainstream schools is often indifferent. In the employment sector, there are misconceptions that they may be less productive and inefficient in the work. During the last pandemic situation, when schools were functioning online, CwDs faced issues such as being visually impaired and people with speech and hearing disabilities found it comparatively difficult to understand whether appropriate measures of imparting the lessons were not adopted by the teachers.[22] The negative attitude and stigmatization toward the disabled persons in the community and the pandemic crisis may aggravate the mental health issues along with their pre-existing health conditions.[23]

Barrier of accessing services from caregivers by disabled individuals

In the pandemic situation, maintenance of physical distancing, fear of contracting infection from surfaces in public places, and lockdowns often cause restrain on the mobility of people, and thus, the pre-existing challenges of accessibility among the disabled population increase several folds.[24] It is critical to maintain healthcare services during pandemics. Inaccessibility of infrastructure and lack of trained and equipped staff at hospitals has been a barrier for disabled persons. Caregivers are the real conduit for the person with disability to remain resourceful, self-sustained, and well-connected to the outside world in case of any requirement. Thus, the responsibilities of the caregivers increase manifold during the pandemic crisis, but they also need to take precautions for their own safety and mental health. It becomes mandatory for the caregivers to follow physical distancing norms and other safety measures to keep themselves as well as their patient safe from the contraction of the infection.[25]

Actions and opportunities to provide support to disabled persons

The preparation to handle the situation of pandemic may be based on DEPwD’s Comprehensive Disability Inclusive Guidelines, 2020, and the National Disaster Management Authority, Union Ministry of Home Affairs issued National Disaster Mnagement Guidelines on Disability Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction.[26] In the light of the challenges and barriers experienced by individuals with disability in pandemic situations, appropriate measures that may provide support to them are now being discussed:

Self-measures to be adopted by persons with disability

Amendments to cater to personal hygiene and assistive care

Personal and environmental hygiene are the most vital aspects for containing the spread of infections among people, such as washing hands frequently with soap, using a hand sanitizer with ~ 60-percent alcohol, properly laundered and completely air-dried clothes, disinfection of all the exposed surfaces with 5,000-ppm solution of bleach and water. Disinfectant solution or soft damp cloth may be used to clean the entire surface of the orthotics/splints and prosthetic devices/special seats/standing frames and other devices.[27]

Routine cleaning, sanitizing, and disinfection guidelines must be followed to maintain environmental hygiene. For sanitation and hygiene purposes, at least one set of toilet rooms in the home/institution must be specifically designed for individuals using wheelchair, wheeled walker, cane, or any other mobility device and these places must be easily accessed by people while seated in a wheelchair or using another mobility device and necessarily comply with specifications given in the “Harmonised Guidelines and Space Standards for Barrier-Free Built Environment for Persons with Disability and Elderly Persons” issued by the Ministry of Urban Development, Govt. of India. The safety precautions must be ensured while helping the persons with disability.[28]

Healthy mental well-being for self

During the pandemic situations where disruption of routine and restriction on mobility in public space have been experienced, individuals need to come up with healthy coping strategies through which they can keep themselves occupied. Playing games, using cognitive-analytical abilities, solving puzzles, writing, or learning new skills—cooking, music, and art could be incorporated in their routine. They must ensure that they eat healthy and regular meals, sleep and get up at regular time every day, include simple exercises in their routine, and try yoga and meditation to keep themselves calm and away from negative thoughts. They need to be considerate toward their family and behave politely with them and avoid conflicts and arguments with the family members. They should continue to take their medications and follow the advice of their psychiatrist throughout the lockdown period. In case of emergency, they must contact the nearby doctor or physician.[29]

Contribution of families toward care of disabled persons

Parents of the CwDs can help them in preparing a schedule, mimicking their previous schedule, professional counselors, and as per the needs of their children. They must be encouraged to adopt new skills which will ensure their cognitive development and will also help them in subsiding the boredom.

Actions by the authorities

At the global level, it has been suggested that the concerned authorities are required to safeguard the provision of food, medicine, and other supplies for persons with disabilities during situations of isolation and quarantine. All services related to COVID-19 crisis, including remote/telephone medical advice, quarantine facilities, public information, including accessible information (in the medium of their understanding) on essential supplies, and services, must be accessible for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others and provided on accessible platforms in various alternative formats, modes, and methods of communication.[30]

Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016 clearly mentions in Chapter V, Section 25 that the appropriate Government and the local authorities (1) shall take necessary measures for the persons with disabilities to provide,-(a) free healthcare in the vicinity specially in rural area subject to such family income as may be notified; (b) barrier-free access in all parts of Government and private hospitals and other healthcare institutions and centres; (c) priority in attendance and treatment. and (2) will make schemes or programmes to promote healthcare and prevent the occurrence of disabilities and shall (a) undertake or cause to be undertaken surveys, investigations and research concerning the cause of occurrence of disabilities; (b) promote various methods for preventing disabilities; (i) healthcare during the time of natural disasters and other situations of risk. Designated officials are required to be deputed to ensure above measures.

Medical colleges and super-specialty institutes must be well-equipped to handle any disaster or epidemic situation. Mental health and stigma issues can be managed well using infrastructure and manpower available with them. Accessibility to build environment, information and communications technologies, transportation services, and emergency services have to be part of inclusive care for PwDs as mandated in the RPwD Act, 2016. Section 25 of the Act is specifically devoted to healthcare of PwDs and mandates provision of quality healthcare services on equal basis with others which is in line with the provision in Article 25 of the UNCRPD. It is important to note that all the provisions in Section 25 of the RPwD Act are mandatory and failure to ensure these would invite penal action under the said Act.[31]

There is an urgent requirement to address the vulnerabilities faced by PwDs and their families during the pandemic crisis because of their preexisting disability and associated health issues. As observed earlier, persons with disabilities, elderly populations, and individuals with chronic health conditions are the worst hit by COVID-19.

As per WHO,[32] every member state is bound to provide assistive technologies to the PwDs through appropriate provision mechanisms either free through public health system, social welfare, through insurance, charitable, loan, or out-of-pocket expenditure. Suitable management or healthcare provisions for the PwDs must be incorporated into programs by appropriate adaptations. For example, few existing programs are already providing assistance to the people with disability in India are listed in Table 2. The Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities issued “Comprehensive Disability Inclusive Guidelines for protection and safety of persons with disabilities (Divyangjan) during COVID 19” to all States/UTs including that caregivers of PwDs are required to be allowed to reach the divyangjan by exempting them from restrictions during lockdown. Also, all the States/UTs were requested by the Ministry to ensure barrier-free environment and easy access to persons with benchmark disabilities in the centres for COVID-19 testing and quarantine facilities as well as for treatment at hospitals and health centers.[33] “Unique ID for Persons with Disabilities” project is also being implemented by the ministry with a view of creating a National Database for PwDs and to issue a Unique Disability Identity Card to each person with disabilities. The project will encourage transparency, efficiency, and ease of delivering the government benefits to the person with disabilities ensuring uniformity. The project will also help in streamline the tracking of physical and financial progress of beneficiary at all levels of hierarchy of implementation.[34]

Table 2:

Programs providing assistance to the people with disability in India[35]

| Program name | Type of disability |

|---|---|

| National Program for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCB&VI) | Eye health for all |

| National Program for Prevention and Control of Deafness (NPPCD) | Hearing impairment and deafness |

| Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) | Covers 4 ‘D’s viz. Defects at birth, deficiencies, diseases, and development delays including disability. |

| National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Stroke (NPCDCS) | Caused by stroke |

| National Mental Health Program (NMHP) | Mental disorders |

| The District Mental Health Program (DMHP) | Mental disorders |

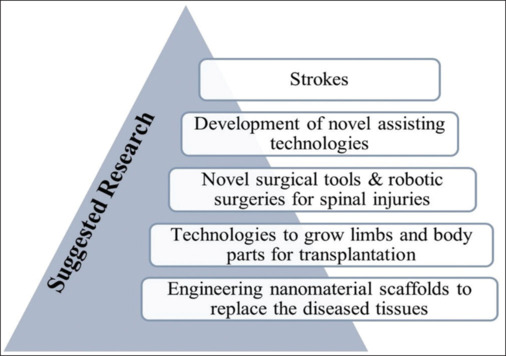

Most of these programs work through state health systems right down to subsidiary health centers or subcenters. Any attempt to provide services to the PwD and FI persons through these national health programs would be accepted and understood by health workers easily. Therefore, it is necessary to develop advisories and guiding documents to update their knowledge and enhance their functioning. Also, research is required into many areas related to people with disability and their healthcare and rehabilitation services [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Suggested research areas to facilitate people with disability

Actions from the community

Employees with severe disabilities in both public and private sector may be given work-related relaxation as per government advisory released time to time. If work from home is not possible, considering a person with a disability is at high risk of getting infection they must be allowed to take leave until the risk is reduced. Checking regularly with a person with a disability provides emotional and practical support, respecting social isolation restrictions that may be in place. During quarantine, essential support services (food, water, and medicine), personal assistance, and physical and communicative accessibility may be ensured for the disabled persons by their families and neighbors. Peer-support networks may be set up to facilitate support during quarantine for disabled persons. Details of pandemic or any situation must be provided to the people with disability in a way they understand and do not misinterpret the information. Psychological and emotional support and access to mental health services may be provided to vulnerable populations with the help of various voluntary or policy-making organizations.[36]

Special attention is required to be paid for the gender-specific needs of the individual with disability concerning the impairment as well as the health concerns.[37] However, offering help such as providing them with telemedicine services ensures that the medium of communication is appropriate and accessible to the person with disability. For example, a voice recording could be sent to a person with visual impairment and a text message to a person with hearing disability. Also, the information must be given in the first language of the disabled individual, if possible. Using person-first language is a great place to start, as it fosters greater understanding, dignity, and respect for everyone, whether they are experiencing mental health challenges or not, without reducing them to a diagnosis or condition.[38] A good example is the use of “person-first language” in the context of mental illness. I am “a person with depression” and not a “depressed person.” The person comes first, and the disorder does not define the person. Most importantly, community members must share positive messages rather than discriminating ones against people with disabilities. Urban as well as rural communities are required to be sensitized and thorough awareness must be created about the general principles of needs of the disabled population during pandemic crisis. Elderly people essentially be provided with practical and emotional support during such crisis through informal networks (families) and health professionals.

Telerehabilitation is a feasible and potentially effective alternative to face-to-face rehabilitation during pandemics. During COVID-19 pandemic also, practitioners rapidly adopted telerehabilitation for people with physical disabilities and movement impairment. However, specific guidance, training, and support for practitioners who undertake remote assessments in people with physical disabilities and movement impairment are limited.[39] The drastic situation provided an opportunity to optimize the technological innovations in health and scale up these innovations to meet the growing burden of disability in LMICs. It is important to educate and upskill the current and future health and social care workforce in remote care.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the WHO document on protecting people with disability during the COVID-19 pandemic,[40] a few actions required at various levels have been listed in Table 3.

Table 3:

List of actions required at various levels

| Actions from PwDs | Actions from caregivers | Actions from policymakers | Actions from healthcare workers | Actions from service providers | Actions from community |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Put a plan in place to ensure continuity of care and support. | Plan ahead to ensure continuity of medical care, medication, other supplies, psychosocial, mental health support, and other requirements such as repairing or replacing assistive products. | Engage people with disability and their representatives in planning the pandemic response. | Deliver information and communicate in diverse formats to suit the different needs of people with different disabilities. | Consider engaging the community and asking for support, particularly people from relevant disciplines (e.g., nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy). | Establish flexible workplace arrangements for people with disability and caregivers |

| Stock enough food, medication and other essential products for at least two weeks. | All assistive products should be regularly cleaned and disinfected. | Ensure all health care facilities are accessible, including testing and isolation services. | Health workers must be aware of the potential impact on the health and living conditions of people with disability. | Continue to provide sufficient support for people with disability with complex needs. | Appropriate action by schools and other educational facilities to ensure continuity of education for students with disability. |

| Regularly clean and disinfect assistive products such as wheelchairs, cane, etc. | Keep a list of public services and community organizations for emergency requirements | Provide hotline in multiple formats (telephone, email, SMS, easy language apps, etc.). | Adopt alternative ways of providing healthcare such as telephone consultation and video conferencing to maintain services | Family, friends, and neighbors are advised to regularly check on people with disability to provide emotional and communication support. | |

| Identify organizations, hotlines, and people in case of emergency | Ensure that financial compensation schemes cover for them, their families, and caregivers comprehensively. |

Limitations of the study

However, this study has used a stepwise approach and the included articles were subjected to an in-depth and comprehensive literature analysis for challenges faced by the people with disability during pandemic situation, the study has its limitations, and its findings should be considered in the light of these only, such as the search was limited to the articles published in English. Although to mitigate this issue, we have uniformly applied our eligibility criteria and used a comprehensive list of keywords and various databases, but it is likely that some relevant studies might have been missed.

CONCLUSION

There is a need to practice various guidelines and expert recommendations for emergency and public health planning with specified steps to include people with disability, particularly at the local level. Even in noncrisis situation, people with disabilities encounter problems including inaccessible services, lack of appropriate transport to and from healthcare facilities, out-of-pocket expenditure, stigma, and discrimination at every point. Thus, research is required to explore the effectiveness of interventions to improve access to healthcare for disabled people. Also, there is a need to decentralize and provide timely, affordable, and consistent access to good quality disability-related services, including rehabilitation, such as through community-based interventions. Evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to address persistent biases in health systems and to ensure all services are inclusive of and responsive to the needs of people with different types of requirements is critical for planning. Furthermore, information systems used to track health and other outcomes during crises are required to include data on individuals with disability to enable real-time disaggregation to understand the impact on this population and monitor whether these people are being adequately reached and included in response activities.

Disclaimer

The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors. Each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work. The views expressed in the journal are personal and do not represent any organization’s views.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: SA, HT, and RS; writing, designing: SA and PA; review and editing: SA, PA, and HT; final review and supervision: AG and RS. All authors have read and agreed to submit this final version of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. Disability and Health Promotion, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html . [Last accessed on 2024 Mar 29] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World health organization; 2001. WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health#:~:text=The%20International%20Classification%20of%20Functioning,a%20list%20of%20environmental%20factors . [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), United Nations Headquarters-New York. 2006 Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities . [Google Scholar]

- 4.World health organization; 2011. WHO World report on disability. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persons with Disabilities (Divyangjan) in India-A Statistical Profile. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) 2021 March; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Census of India, Govt. of India. “Disabled population”. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porta M, editor, editor. 6th. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. A Dictionary of Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhav N, Oppenheim B, Gallivan M, Mulembakani P, Rubin E, Wolfe N. Pandemics: Risks, impacts, and mitigation. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, , et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 3rd. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser C, Riley S, Anderson RM, Ferguson NM. Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. PNAS. 2004;101:6146–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disability and Development Report Published by the United Nations New York, United Nations, New York, United States of America. 2018 Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2019/10/UN-flagship-report-on-disability-and-development.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization; 2024. WHO Epidemic and pandemic-prone diseases. Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/pandemic-epidemic-diseases/outbreaks/index.html . [Last accessed on 2024 Mar 29] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal D, Hunt X, Kuper H, Shakespeare T, Banks LM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with disabilities and implications for health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2023;28:77–9. doi: 10.1177/13558196231160047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann M, McMillan JE, Silver EJ, Stein REK. Children and adolescents with disabilities and exposure to disasters, terrorism, and the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23:80. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerson E, Fortune N, Llewellyn G, Stancliffe R. Loneliness, social support, social isolation and wellbeing among working age adults with and without disability: Cross-sectional study. Disabil Health J. 2021;14:100965. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khasnabis C, Heinicke Motsch K, Achu K, Jubah KA, Brodtkorb S, Chervin P, , et al., editors. Community-Based Rehabilitation: CBR Guidelines. Assistive devices. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2002;1:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1196–252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babik I, Gardner ES. Factors affecting the perception of disability: A developmental perspective. Front Psychol. 2021;12:702166. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.702166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sujan MSH, Tasnim R, Islam MS, Ferdous MZ, Haghighathoseini A, Koly KN, et al. Financial hardship and mental health conditions in people with underlying health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2021;8:e10499. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Luo Y, Zhang R, Zheng X. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on emotional and behavioral problems of children with autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay aged 1-6 years in China. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1134396. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1134396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green L, Kreuter M. 4th. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg S, Deshmukh CP, Singh MM, Borle A, Wilson BS. Challenges of the deaf and hearing impaired in the masked world of COVID-19. Indian J Community Med. 2021;46:11–4. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_581_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rewerska-Juśko M, Rejdak K. Social stigma of patients suffering from COVID-19: Challenges for health care system. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10:292. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10020292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filip R, Gheorghita Puscaselu R, Anchidin-Norocel L, Dimian M, Savage WK. Global challenges to public health care systems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of pandemic measures and problems. J Pers Med. 2022;12:1295. doi: 10.3390/jpm12081295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McBride-Henry K, Nazari Orakani S, Good G, Roguski M, Officer TN. Disabled people’s experiences accessing healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:346. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Disability-inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction: Pathways for Inclusion and Action for Resilience, National Institute of Disaster Management, New Delhi. 2020 Feb; Available from: https://nidm.gov.in/PDF/pubs/05Feb2020DiDRR_Report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 27.CDC Hand Sanitizer Use Out and About, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/hand-sanitizer-use.html . [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC Environmental Cleaning Procedures, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/resource-limited/cleaning-procedures.html . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finlay JM, Kler JS, O’Shea BQ, Eastman MR, Vinson YR, Kobayashi LC. Coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study of older adults across the United States. Front Public Health. 2021;9:643807. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.643807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United nations; 2020. UN Policy brief: A disability-inclusive response to COVID-19. Available from: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Policy-Brief-A-Disability-Inclusive-Response-to-COVID-19.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 31.GOI The rights of persons with disabilities act, Govt. of India, New Delhi 2016. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15939/1/the_rights_of_persons_with_disabilities_act%2C_2016.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization; Mar, 2020. WHO Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Available from: https://www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome?gclid=CjwKCAiApuCrBhAuEiwA8V J6JvioMP0ktdzdshZmddVsROwvBDl_ZVtk25rDsR2I9L6MWsCw8zLbORoCfxsQAvD_BwE . [Google Scholar]

- 33.GOI Safety and Welfare of Divyangjans During Covid-19, Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 34.GOI Unique Disability ID, Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schemes-Programmes. Vikaspedia. 2024 Available from: https://vikaspedia.in/social-welfare/differently-abled-welfare/schemes-programmes . [Last accessed on 2024 Mar 29] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thara R, Patel V. Role of non-governmental organizations in mental health in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S389–95. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Disability, United Nations. 2010 Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/issues/women-and-girls-with-disabilities.html#:~:text=General%20Assembly%20resolution%2063%2F150, freedoms%20(operative%20paragraph%208) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mental Health First Aid, National Council for Mental Wellbeing, USA. 2022 Available from: https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/our-work/mental-health-first-aid/ [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buckingham SA, Anil K, Demain S, Gunn H, Jones RB, Kent B, et al. Telerehabilitation for people with physical disabilities and movement impairment: A survey of United Kingdom Practitioners. JMIRx Med. 2022;3:e30516. doi: 10.2196/30516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization; 2020. WHO document on Protecting people with disability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available from: https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/WHOEMHLP122E-eng.pdf . [Last accessed on 2024 Mar 29] [Google Scholar]