Abstract

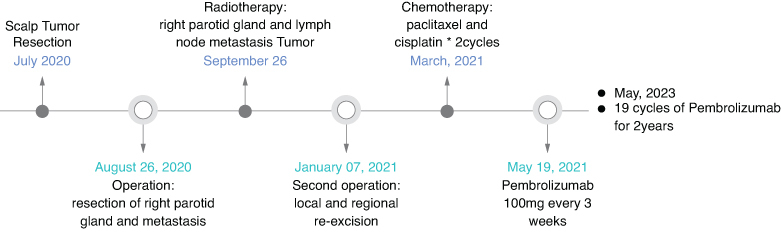

Trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) is a rare, malignant cutaneous adnexal tumor. TC often has nonspecific clinical manifestations and its aggressive nature is frequently overlooked. Metastasis of TC is rarely reported and there is no standard treatment for recurrent or metastatic TC. We report a complicated case of TC arising from the parotid gland with metastasis to cervical lymph nodes. The tumor progressed after multiple surgeries, radiation and chemotherapy. Finally, the patient achieved good response and disease control with pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor targeting programmed cell death protein-1. Currently, the patient has received 19 cycles of pembrolizumab and the disease remains well controlled. This represents the first reported use of immune checkpoint blockade to treat TC.

Keywords: : cutaneous oncology, PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade, pembrolizumab, trichilemmal carcinoma

Plain Language Summary

This paper discusses a rare form of skin cancer called trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) and presents a distant metastasis TC case. The patient was treated with an immunotherapy called pembrolizumab and after 19 courses of treatment, the tumor was significantly reduced and the symptoms were relieved. This case report is the first recorded case study of pembrolizumab for the treatment of TC and provides a new approach to the treatment of challenging malignancies.

Plain language summary

Executive summary.

Trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal carcinoma originating from the outer root sheath of hair follicles, with nonspecific clinical manifestations that can pose challenges in diagnosis and effective treatment.

Metastasis of TC is uncommon, and there is currently no established standard treatment for recurrent or metastatic TC.

Early-stage TC can be managed with surgery, while recurrent or metastatic TC can be managed with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy; however, immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted agents have not yet been reported for TC treatment.

The case study presented in the paper details a complex scenario of TC originating from the scalp and spreading to the parotid gland and cervical lymph nodes.

Despite undergoing multiple conventional treatments, including surgeries, radiation and chemotherapy, the tumor exhibited progression.

Pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, has demonstrated efficacy in treating advanced and metastatic TC, leading to significant tumor reduction and symptom relief after 19 treatment cycles.

This case report signifies the first documented utilization of immune checkpoint blockade therapy, specifically pembrolizumab, in TC treatment. It introduces a novel approach to therapeutic interventions in rare and challenging malignancies.

The successful use of pembrolizumab in this case report highlights the potential of immune checkpoint inhibitors as a valuable treatment option for refractory TC cases, offering hope for future treatment strategies.

1. Background

Trichilemmal carcinomas (TC) is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal carcinoma originating from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle epithelium, only 1% of all adnexal carcinomas [1,2]. It manifests as an ulcerated nodule, papule, asymptomatic exophytic or polypoid mass, usually affecting sun-exposed skin [1–3]. The most involved areas are the forehead, scalp, neck, back of hands and trunk in older adults with an indolent clinical course [4], but can also occur rarely in places such as the eyelid margin [5,6]. They were not described until recently, and such tumors also include trichoblastic carcinomas and malignant pilomatricomas [1,2,7,8]. Reports on TC are limited, mostly are case reports, few with large samples. Per Hamman et al. [9] reported that 103 TC cases, 60% were male, 51% facial, mean age 72.5 years. A 2023 review [10] of 231 TC cases found increasing incidence with aging, susceptible groups were men 60–80 years, women over 80 years, commonly head/neck. TC is an invasive, atypical clear cell neoplasm of adnexal keratinocytes continuous with the epidermis and/or hair follicle, exhibits lobular proliferation centered on pilosebaceous structures, composed of clear cells characterized by clear glycogen-rich cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli and exhibits trichilemmal keratinization with an abrupt or pagetoid interface and dermal invasion [11–13]. TC should be differentiated from other similar skin tumors such as basal cell carcinoma, trichilemmoma, trichoepithelioma, clear cell squamous cell carcinoma, porocarcinoma and hidradenocarcinoma [7,9,10,14]. The TC diagnosis can only be is made after pathological examination [15], therefore, the average time to diagnosis is 18 months (median 9 months) [13].

Early-stage TC can be treated with surgery, with margins of 0.5–3 cm [7] and Mohs micrographic surgery is preferred [16,17]. Recurrent or metastatic TC can be managed with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, though regimens are typically extrapolated from other cutaneous malignancies [3,4,9,18–20]. Immunotherapy may improve outcomes for advanced adnexal tumors [21] and immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown efficacy against various solid tumors. However, immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapy have not yet been reported for TC [22]. Options for unresectable or metastatic TC remain limited and prognosis is poor [9,19,20,22]. In this report, we describe a case of highly aggressive and refractory TC with recurrence and metastasis. The patient underwent multiple surgeries, radiation and chemotherapy without control of tumor progression. Finally, the patient achieved significant reduction in tumor burden and good quality of life with pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor. This represents the first reported use of immune checkpoint blockade to treat TC.

2. Case report

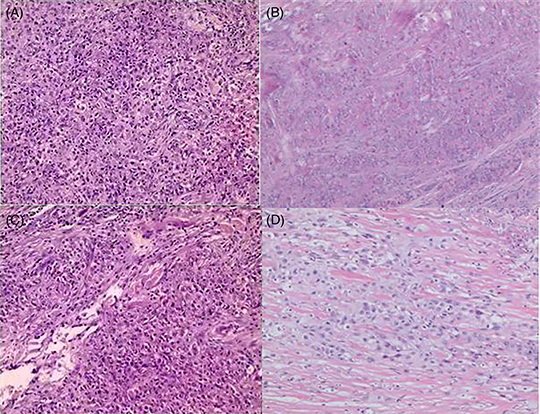

A 40 years old patient presented in July 2020 with a 2-month history of gradually enlarging scalp mass. Excisional biopsy revealed malignant transformation of the outer root sheath, consistent with TC. The tumor measured 3.5 × 3.0 × 2.0 cm. In August 2020, the patient found a new growth under the right ear, and a whole-body 18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG)-positron emission (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a soft tissue mass in the right parotid gland with significantly increased FDG metabolism (Supplementary Material 1). Therefore, the patient underwent resection of right parotid gland and cervical lymph node metastases, which measured 2.0 × 1.8 × 1.2 cm. Pathology indicated nests of atypical cells with keratinization and necrosis. After a detailed analysis of the pathological features, it is suggested that the lesion is identical to the scalp lesion, showing features consistent with TC, indicating metastatic TC originating from the scalp tumor. Immunohistochemistry results were positive for CK5/6/7/8/14/18/19, S100, EMA, p40, p63 and TRIM29, with 50–75% Ki-67 expression and negative for CEA and vimentin (Figure 1A & B).

Figure 1.

Pathology of the trichilemmal carcinoma patient. (A & B) Initial postoperative pathology showed that malignant transformation of outer root sheath tumor and nests of atypical cells with keratinization and necrosis, diagnosed as trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) with parotid gland and lymph node metastasis. (C & D) The pathology of re-excision showed that there were large necrotic foci in the hyperplastic fibrous tissue, small nested atypical cells, a large amount of foam cell infiltration, confirmed metastatic TC with extensive necrosis and perineural invasion. (A & C hematoxylin and eosin ×100, B & D hematoxylin and eosin ×40).

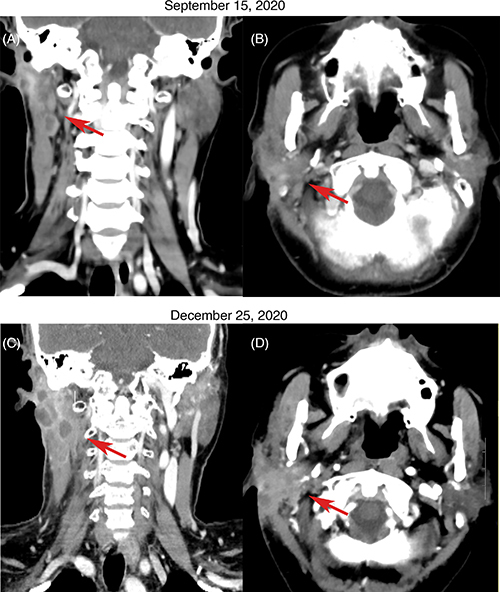

Unfortunately, CT scan 1 month postoperatively in September 2020 showed recurrence in the right parotid gland and cervical lymph nodes (Figure 2A & B). The patient received intensity-modulated radiotherapy (70 Gy parotid/cervical metastases, 60 Gy tumor bed/parotid gland/regional nodes) from September to November 2020. However, follow-up CT scan in December 2020 showed further enlargement of the recurrent parotid and cervical disease (Figure 2C & D). She underwent re-excision in January 2021. Pathology again confirmed metastatic TC with extensive necrosis, perineural invasion and 10% Ki67 expression (Figure 1C & D).

Figure 2.

CT scans showing disease progression in metastatic trichilemmal carcinoma. (A & B) CT scan on 15 September 2020 after initial surgery showed recurrence in the right parotid gland and cervical lymph nodes. (C & D) CT scan on 25 December 2020 after radiotherapy showed enlargement of parotid and cervical lymph node metastases.

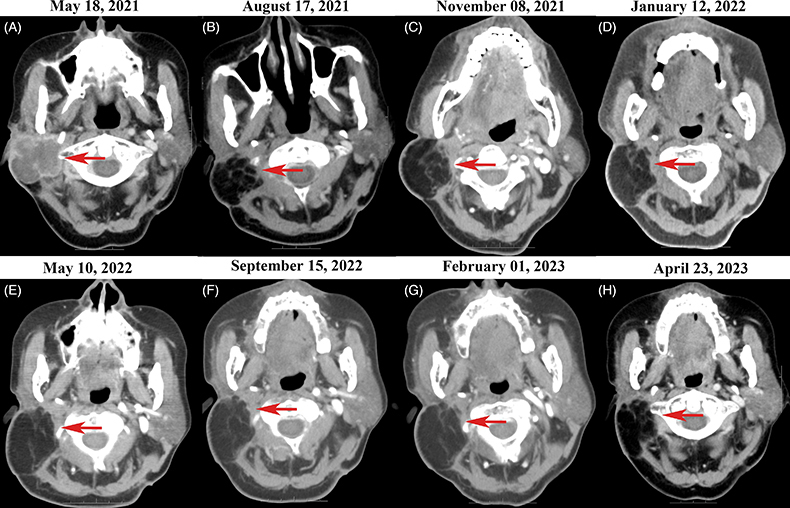

The patient’s condition deteriorated significantly after re-excision. She received two cycles of adjuvant paclitaxel and cisplatin in March and April 2021, but chemotherapy was discontinued due to side effects including pneumonia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. CT scan in May 2021 showed rapid re-growth of parotid and cervical disease (Figure 3A). Programmed death-ligand-1 (PD-L1) testing with 22C3 antibody, which showed that tumor cells expressed tumor proportion score (TPS) 2% + in PD-L1. Given poor tolerance of prior treatments, the patient’s weight 56 Kg and height 155 cm, pembrolizumab 100 mg was initiated in May 2021, once every 3 weeks. After three cycles, CT scan in August 2021 showed significant decrease in tumor size (Figure 3B). However, the patient developed immune-related pneumonia (Figure 4A) with acinetobacter infection after seven cycles, requiring 3-month pause in pembrolizumab. With steroids and antibiotics, pneumonia improved (Figure 4B) and pembrolizumab was resumed. As of May 2023, the patient has received 19 cycles of pembrolizumab over 2 years with stable disease (Figure 5, Supplementary Materials 2 & 3). Pembrolizumab was discontinued after May 2023, and the most recent follow-up in November 2023. Fatigue, hypothyroidism and increased D-dimer were managed. The patient’s condition remains stable without tumor-related symptoms. CT scans show decrease in parotid/cervical tumor size and resolution of pneumonia (Figures 3C–H, 4C).

Figure 3.

CT scans showing response to pembrolizumab in metastatic trichilemmal carcinoma. Red arrows indicate areas of metastatic parotid and cervical lymph node disease. (A) CT scan on 18 May 2021 after second surgery and two cycles of chemotherapy showed further disease progression. (B) Follow-up CT scan on 17 August 2021 after three cycles of pembrolizumab demonstrated significant decrease in size of parotid and cervical metastases. (C–H) Follow-up CT scans on May 2021–April 2023 during treatment with 2 years pembrolizumab showed stable parotid and cervical disease.

Figure 4.

CT scans showing immune-related pneumonia after seven cycles of pembrolizumab, response to treatment and follow-up. (A) Chest CT on 6 December 2021 showed inflammatory changes and partial lung consolidation after seven cycles of pembrolizumab. (B) Follow-up chest CT on 15 March 2022 demonstrated resolution of pulmonary infiltrates after treatment with steroids and antibiotics. (C) Chest CT on 24 April 2023 showed stable disease without specific tumor-related symptoms.

Figure 5.

Clinical timeline of the patient with metastatic trichilemmal carcinoma.

3. Discussion

Clinical characteristics of TC were first described by Headington, and six pathological diagnostic criteria were suggested [11,12]. Typical histopathology of TC shows trichilemmal keratinization and a peripheral palisading pattern indicating the follicular root sheath origin of the tumor [23]. On immunohistochemistry, TC is positive for CK1, 10, 14, 17 and 19, CK17 can also be used as a diagnostic marker for TC [10,24,25]. They are also positive for the Ki-67, p63, p53 and other cytokines (CK7, 8, 15, 16, 18) [10,13,25]. EMA was widely adopted with half positive and half negative and CEA usually negative for the CEA, although late positive results have occasionally been reported [10]. Furthermore, the negativity of S100, HMB45, vimentin and MelanA may be constructive for the diagnosis of TC [10]. TP53 mutations were identified in patients who had an aggressive clinical course, and patients with TP53 mutations had an aggressive clinical course [26]. Another report has indicated that the loss of wild-type p53 heterozygosity is a critical event for the malignant transformation of TC [27]. Furthermore, anecdotal evidence hints at a potential immunosuppressive role of p53 during the malignant transformation of TC [5,9]. Most TC patients had a significant history of lifetime sun exposure or ultraviolet radiation [3,28,29,10], like cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), indicated that genetic changes found in TC resembled those of other skin cancers, suggesting a similar molecular pathogenesis, providing us with a direction for treating TC. In this patient, although with no history of ultraviolet radiation exposure, had the tumor first occur on the scalp, with pathological features consistent with TC. It also conforms to the literature-reported presentation of TC metastasis to the parotid gland [4]. Immunohistochemistry results were positive for CK5/6/7/8/14/18/19, S100, EMA, p40, p63 and TRIM29, with 50–75% Ki-67 expression, and negative for CEA, and vimentin, consistent with the literature reports [10,13,24,25]. As mentioned above, the patient’s TC diagnosis with distant lymph node metastasis is unambiguous.

5- and 10-year survival of TC are 86.1–89.5% and 68.4%, respectively [30,31]. Mean overall survival was 88 months (range 27–128 months) [27]. Given low malignancy, indolence, rare metastasis but tendency to recurrent, wide excision and close follow-up for early recurrence detection are recommended [9,12,32]. A 1 cm margin is considered safe, affordable and effective. However, it is crucial to accurately report and document this margin due to the risk of recurrence [3]. As highlighted by Zhuang et al. [3], inadequate surgical margins of ≤1 cm and node metastasis are associated with a poor prognosis. While local recurrence is frequent, distant metastasis is rare (2–8%) [3]. This underscores the importance of achieving complete excision, clear margins and diligent follow-up, with incomplete excision necessitating re-excision [33,34]. Metastasis is associated with a poor prognosis [35]. Mohs microsurgery, valued for small defects and good cosmesis, has been used for TC, common in face, head and neck with maximizing margin control and cosmetic outcome [16,17]. Although outer root sheath, interlobular tissue, is moderately radiosensitive, radiotherapy has cured TC [36]. For local recurrence and node metastasis, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy may be effective [3,9,18–20]. Imiquimod 5% cream, a topical immune response modifier, may be an option for treatment TC [37]. Multiple recurrences and node metastases even after wide excision have been reported, with nodes indicating poor prognosis [3,18,38,39]. Recurrent/metastatic disease requires aggressive treatment, but optimal treatment and standard chemotherapy are lacking [9,10,40]. The patient with TC has poor responses to surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and there are currently no other effective treatment options, we are considering using immune checkpoint inhibitors for treatment. However, immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted agents have not yet been reported for TC.

Cemiplimab, an antibody that blocks the programmed cell death protein-1, has demonstrated significant antitumor efficacy and improvements in the quality of life for patients with cSCC, and it is the first approved treatment in the USA and EU for patients with locally advanced or metastatic cSCC who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiotherapy [41,42]. However, it has not been introduced in China. In 2017, a study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of pembrolizumab in treating unresectable locally advanced cSCC at a dosage of 2 mg/kg, administered once every 3 weeks. Following four cycles of treatment, nearly complete tumor regression was observed [43]. Additionally, Lavaud J et al. [44] treated four patients with locally or regionally advanced cSCC using pembrolizumab at 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks along with concurrent radiotherapy. The results showed effective disease control with no observed toxicity. A recent Phase II study [45] investigated the effectiveness and safety of pembrolizumab as a first-line therapy for patients with unresectable cSCC. The study reported an objective response rate (ORR) of 41% at week 15, with median progression-free survival of 6.7 months and an overall survival of 25.3 months. It is noteworthy that pembrolizumab related adverse events affected 71% of patients, with 7% classified as grade 3 or higher. The study also found that PD-L1 expression TPS ≥ 1% was associated with better pembrolizumab efficacy [45]. Furthermore, in patients with refractory cSCC, a long-term follow-up confirmed the antitumor activity and safety profile of pembrolizumab [46]. The median duration of response was 27.3 months, with a complete response (CR) rate of 15%, an ORR of 32% and a clinical benefit rate of 37%. Severe treatment related adverse events (grade ≥ 3) occurred in 10% of patients (two out of 20). Notably, PD-L1 expression did not show a correlation with the response to pembrolizumab [46]. Recently, KEYNOTE-629 [47,48], a Phase II pembrolizumab study for advanced/recurrent/metastatic cSCC, included 159 patients. Locally advanced disease ORR was 50.0% (95% CI: 36.1–63.9%), with 16.7% complete response rate (CR) and 33.3% partial response rate (PR). Recurrent/metastatic disease ORR was 35.2% (95% CI: 26.2–45.2%), with 10.5% CR and 24.8% PR, suggesting pembrolizumab promising for cSCC [47,48]. To Merkel cell carcinoma, KEYNOTE-017 study [49,50] showed pembrolizumab approved for advanced/metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, another aggressive cutaneous cancer, with the ORR for first-line therapy was 56% and the CR was 24% for recurrent locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Attributed to the two studies above, pembrolizumab has been indicated in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines as a treatment recommendation.

Given rare TC metastasis/local recurrence, inadequate surgery/radiotherapy/chemotherapy response of this patient, similar pathogenesis and the successful use of pembrolizumab in cSCC, pembrolizumab seems a promise for TC, and we chose pembrolizumab after informed consent. In general, the standard dose of pembrolizumab is 200 mg every 3 weeks or 400 mg every 6 weeks. However, in the case of this patient, who was in poor overall physical condition and weighed only 55 kg, a dose of 100 mg every 3 weeks was attempted, taking into account the patient’s financial constraints and the lack of other suitable treatment options. After three cycles, significant tumor reduction and symptom relief occurred without adverse effects. The patient received 19 cycles over 2 years with no recurrence/metastasis. Maintenance immunotherapy duration is uncertain, guided by other cancers, patient tolerance, and disease control. This seems the first 2-year checkpoint inhibitor maintenance report for TC, showing good tolerance and acceptable toxicity comparing with cSCC.

4. Conclusion

Given the risk of TC recurrence and metastasis, we recommend multidisciplinary cancer committee determination of treatment plans after initial staging with head/neck, chest, abdominal and pelvic CT. Immune checkpoint inhibitors should be considered as optimal treatment for refractory lymph node recurrence or metastasis. Close screening for metastasis and follow-up is also needed to improve prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2208085Y32 to CL Tang), the Anhui Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Project (Grant No. 2022AH020076 to CL Tang), the Chen Xiao-Ping Foundation for the Development of Science and Technology of Hubei Province (Grant No. CXPJJH12000005-07-115 to CL Tang) and supported by Hefei Municipal Natural Science Foundation project (Grant No.202333 to J Gao).

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/1750743X.2024.2353535

Author contributions

L Liu, TF Long, NN Wei and HY Zhang were responsible for collecting literature and writing the manuscript. J Gao and CL Tang contributed to polishing the language and were responsible for the final version of this commentary.

Financial disclosure

This study was supported by grants from the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2208085Y32 to CL Tang), the Anhui Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Project (Grant No. 2022AH020076 to CL Tang), the Chen Xiao-Ping Foundation for the Development of Science and Technology of Hubei Province (Grant No. CXPJJH12000005-07-115 to CL Tang) and supported by Hefei Municipal Natural Science Foundation project (Grant No.202333 to J Gao). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, stock ownership or options and expert testimony.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained verbal and written informed consent from the patient/patients for the inclusion of their medical and treatment history within this case report.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Goto H. Current treatment options for cutaneous adnexal malignancies. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2022;23:736–748. doi: 10.1007/s11864-022-00971-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernárdez C, Requena L. Treatment of malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasms. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109(1):6–23. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhuang SM, Zhang GH, Chen WK, et al. . Survival study and clinicopathological evaluation of trichilemmal carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:499–502. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayakumar P, Kakkar A, Arava S, et al. . Trichilemmal carcinoma metastatic to parotid gland: first report of fine needle aspiration cytology features. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2024;52(5):E100–E104. doi: 10.1002/dc.25279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JH, Shin YW, Oh YH, et al. . Trichilemmal carcinoma of the upper eyelid: a case report. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2009;23(4):301–305. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2009.23.4.301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Lin Z, Wu H, et al. . Corneal perforation caused by eyelid margin trichilemmal carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:896393. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.896393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romeu M, Foletti J M, Chossegros C, et al. . Malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasms of the face and scalp: diagnostic and therapeutic update. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;118(2):95–102. French. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Summarizes rare skin malignancies of the face and scalp, with a focus on hair-differentiated malignant skin tumors, highlights the rarity of these tumors, the lack of consensus on treatment, the importance of histologic examination in diagnosis, the possibility of local or meso-regional invasiveness and the possibility of lymphatic or hematogenous metastases. A multidisciplinary treatment decision with initial imaging staging, surgical resection with safety margins and consideration of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy for metastatic cases is recommended.

- 8.Sia PI, Figueira E, Allende A, et al. . Malignant hair follicle tumors of the periorbital region: a review of literature and suggestion of a management guideline. Orbit. 2016;35(3):144. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2016.1176048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Review article on rare cutaneous adnexal malignancies, particularly orbicular-oculi malignant hair follicle tumors, and provides literature review and management guidelines.

- 9.Hamman MS, Brian Jiang SI. Management of trichilemmal carcinoma: an update and comprehensive review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(7):711–717. doi: 10.1111/dsu.0000000000000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• States that trichilemmal carcinoma (TC) is a rare accessory tumor, and although it is not generally considered an aggressive tumor, there are some cases that exhibit aggressive disease and recurrence. This article summarizes the management and treatment of TC, emphasizing the importance of surgical resection and other treatments, while mentioning the importance of follow-up.

- 10.Sun J, Zhang L, Xiao M, et al. . Systematic analysis and case series of the diagnosis and management of trichilemmal carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2023;12:1078272. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1078272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Summarizes the diagnosis and treatment of three cases in the department and comprehensively analyzes all cases in the literature to comprehensively understand the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of TC.

- 11.Headington JT. Tumors of the hair follicle. A review. Am J Pathol. 1976;85(2):479–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • TC is a cutaneous adnexal tumor originating from the outer root sheath of hair follicle and it was first described by Headington in 1976.

- 12.Headington JT. Tricholemmal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:83–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb01347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett AB, Azmi FH, Ogburia KS. Trichilemmal carcinoma: a rare cutaneous malignancy: a report of two cases. Dermatol. Surg. 2004;30(1):113–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fronek L, Brahs A, Farsi M, et al. . A rare case of trichilemmal carcinoma: histology and management. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(6):25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkie MD, Munir N, Roland NJ, et al. . Trichilemmal carcinoma: an unusual presentation of a rare cutaneous lesion. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012008369. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-008369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. . Mohs micrographic surgery in the treatment of trichilemmal carcinoma: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:195–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Reports that seven patients with early-stage TC achieved maximizing margin control, good control effects and cosmetic outcome through Mohs surgery.

- 17.Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Jimenez YD, Reolid A, et al. . State of the art of Mohs surgery for rare cutaneous tumors in the Spanish registry of Mohs surgery (REGESMOHS). Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:321–325. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lv W, Zheng D, Guan W, et al. . Axillary lymph node dissection combined with radiotherapy for trichilemmal carcinoma with giant lymph node metastasis: a case report. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1019140. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1019140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Iuliis F, Amoroso L, Taglieri L, et al. . Chemotherapy of rare skin adnexal tumors: a review of literature. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(10):5263–5268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chau NG, Wong MP, Rao VK. Chemotherapy for rare skin tumors: adnexal tumors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(1):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wierzbicka M, Kraiński P, Bartochowska A. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of the malignant adnexal neoplasms of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;31(2):134–145. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Bergethon K, et al. . A potential role for targeted therapy in a subset of metastasizing adnexal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(7):974–982. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arslan Z, Bali ZU, Evrenos MK, et al. . Dermoscopic features of trichilemmal carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:321–323. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_468_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allee JE, Cotsarelis G, Solky B, et al. . Multiply recurrent trichilemmal carcinoma with perineural invasion and cytokeratin 17 positivity. Dermatol. Surg. 2003;29:886–889. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29241.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurokawa I, Senba Y, Nishimura K, et al. . Cytokeratin expression in trichilemmal carcinoma suggests differentiation towards follicular infundibulum. In Vivo. 2006;20(5):583–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ha JH, Lee C, Lee KS, et al. . The molecular pathogenesis of trichilemmal carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:516. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07009-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This research article explores the genetic abnormalities and molecular pathogenesis of TC by analyzing genomic DNA from patients diagnosed with TC, identifying key mutations such as TP53 mutations, melanoma-related fusions and other genetic alterations resembling those found in other skin cancers, which may provide insights into potential treatment options for TC.

- 27.Takata M, Rehman I, Rees JL. A trichilemmal carcinoma arising from a proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the loss of the wild-type p53 is a critical event in malignant transformation. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:193–195. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90234-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan K, Lim I, Baladas H, Tan WTL. Multiple tumor presentation of trichilemmal carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;52:665–667. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu DB, Wang T, Liao Z. Surgical treatment of trichilemmal carcinoma. World J Oncol. 2018;9:141–144. doi: 10.14740/wjon1143w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng SR, Huang QD, Fu WD, et al. . Diagnosis and treatment of 23 cases of trichilemmal carcinoma[J]. Chinese J Gen Surg. 2021;36(4):309–310. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn113855-20200525-00421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J, OuYang D. Clinical features and prognosis of trichilemmal carcinoma[J]. Ji Lin Med J. 2014;35(10):2079–2081. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee NR, Oh SJ, Roh MR. Trichilemmal carcinoma in a young adult. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81(5):531–533. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.158644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia QY, Yuan YY, Mao DD, et al. . Trichilemmal carcinoma of the scalp in a young female: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:139–143. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S349797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanitakis J, Euvrard S, Sebbag L, et al. . Trichilemmal carcinoma of the skin mimicking a keloid in a heart transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:649–651. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yi HS, Sym SJ, Park J, et al. . Recurrent and metastatic trichilemmal carcinoma of the skin over the thigh: a case report. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:176–179. doi: 10.4143/crt.2010.42.3.176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan YJ, Mao CZ, Deng DQ, et al. . Clinical and histopathological analysis of 13 cases of trichilemmal carcinoma[J]. Chinese J Dermatol. 2010;43(12):826–828. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jo JH, Ko HC, Jang HS, et al. . Infiltrative trichilemmal carcinoma treated with 5% imiquimod cream. Dermatol. Surg. 2005;31(8 Pt 1):973–976. doi: 10.1097/00042728-200508000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maya-Rico AM, Jaramillo-Pulgarín C, Londoño-García Á, et al. . Locally aggressive trichilemmal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:579–581. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie Y, Wang L, Wang T. Huge trichilemmal carcinoma with metastasis presenting with two distinct histological morphologies: a case report. Front Oncol. 2021;11:681197. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.681197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evrenos MK, Kerem H, Temiz P, et al. . Malignant tumor of outer root sheath epithelium, trichilemmal carcinoma. Clinical presentations, treatments and outcomes. Saudi Med J. 2018;39:213–216. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.2.21085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee A, Duggan S, Deeks ED. Cemiplimab: a review in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2020;80(8):813–819. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01302-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rischin D, Khushalani NI, Schmults CD, et al. . Integrated analysis of a Phase II study of cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of outcomes and quality of life analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(8):e002757. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevenson ML, Wang CQ, Abikhair M, et al. . Expression of programmed cell death ligand in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and treatment of locally advanced disease with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(4):299–303. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavaud J, Blom A, Longvert C, et al. . Pembrolizumab and concurrent hypo-fractionated radiotherapy for advanced non-resectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29(6):636–640. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2019.3671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maubec E, Boubaya M, Petrow P, et al. . Phase II study of pembrolizumab as first-line, single-drug therapy for patients with unresectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(26):3051–3061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrarotto R, Sousa LG, Qing Y, et al. . Pembrolizumab in patients with refractory cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a Phase II trial. Adv Ther. 2021;38(8):4581–4591. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01807-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grob JJ, Gonzalez R, Basset-Seguin N, et al. . Pembrolizumab monotherapy for recurrent or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm Phase II trial (KEYNOTE-629). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2916–2925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes BGM, Munoz-Couselo E, Mortier L, et al. . Pembrolizumab for locally advanced and recurrent/metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-629 study): an open-label, nonrandomized, multicenter, Phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1276–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This article is a multicenter clinical study on the treatment of locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with pembrolizumab, providing a reference for the treatment selection in our article.

- 49.Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. . Durable tumor regression and overall survival in patients with advanced Merkel cell carcinoma receiving pembrolizumab as first-Line therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:693–702. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. . Three-year survival, correlates and salvage therapies in patients receiving first-line pembrolizumab for advanced Merkel cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(4):e002478. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This article showed that 3-year survival, associated factors and salvage therapy for patients receiving first-line pembrolizumab for advanced Merkel cell carcinoma, also providing a reference for the treatment selection in our article.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.