Abstract

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) differs from other members of the family Picornaviridae in that the cleavage of the polyprotein at the 2A/2B junction, commonly considered to be the primary polyprotein cleavage by analogy with other picornaviruses, is mediated by 3Cpro, the only proteinase encoded by the virus. However, it has never been formally demonstrated that the 2A/2B junction is the site of primary cleavage, and the actual function of the 2A sequence, which lacks homology with sequence of other picornaviruses, remains unknown. To determine whether 2A functions in cis as a precursor with the nonstructural proteins, we constructed dicistronic HAV genomes in which a heterologous picornaviral internal ribosome entry site was inserted at the 2A/2B junction. Transfection of permissive FRhK-4 cells with these dicistronic RNAs failed to result in the rescue of infectious virus, indicating a possible cis replication function spanning the 2A/2B junction. However, infectious virus was recovered from recombinant HAV genomes containing exogenous protein-coding sequences inserted in-frame at the 2A/2B junction and flanked by consensus 3Cpro cleavage sites. The replication of these recombinants was less efficient than that of the parent virus but was variable and not dependent upon the length of the inserted sequence. An HAV recombinant containing a 420-nt insertion encoding the bleomycin resistance protein Zeo was stable for up to five passages in cell culture. Inserted sequences were deleted from replicating viruses, but this did not result from homologous recombination at the flanking 3Cpro cleavage sites, since the 5′ and 3′ segments of the inserted sequence were retained in the deletion mutants. These results indicate that the HAV polyprotein can tolerate an insertion at the 2A/2B junction and that the 2A polypeptide does not function in cis as a 2AB precursor. Recombinant HAV genomes containing foreign protein-coding sequences inserted at the 2A/2B junction are novel and potentially useful protein expression vectors.

The family Picornaviridae is comprised of a large number of single-stranded RNA viruses that are currently classified into five major genera of human and veterinary pathogens and several lesser genera (38). These include the genera Enterovirus (of which poliovirus is a member and the prototype picornavirus), Rhinovirus, Cardiovirus (including encephalomyocarditis virus [EMCV]), Aphthovirus (foot-and-mouth disease virus), and Hepatovirus. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is the only virus species within the genus Hepatovirus. A human virus that is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, HAV is responsible for approximately 50% of all cases of acute viral hepatitis within the United States (23). The genomic RNA of HAV shares a general molecular organization and replication strategy with that of other picornaviruses. The positive-strand RNA genome is approximately 7.5 kb in length (12, 26, 34). It is linked covalently to a small polypeptide (VPg) at its 5′ terminus (46), contains a 3′ polyadenylated tail, and is capable of functioning directly as mRNA when introduced into the cytoplasm of host cells (13). A lengthy 5′ terminal nontranslated RNA segment contains numerous highly ordered RNA structures and a functional internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (10). As with the IRES elements of other picornaviruses, the HAV IRES directs the cap-independent translation of a polyprotein encoded within a single large open reading frame (10, 47). Picornaviral IRES elements have been classified as either type 1 (the enteroviruses and rhinoviruses) or type 2 (cardioviruses, aphthoviruses, and hepatoviruses) on the basis of substantial differences in their higher ordered RNA structure, yet they all function to facilitate internal ribosome entry (25, 48).

Despite these similarities to other picornaviruses, the polyprotein of HAV presents some striking and unique features. In enteroviral and rhinoviral replication, the primary polyprotein cleavage takes place at the P1/P2 junction (VP1/2A) and is mediated by a cis-acting viral proteinase activity associated with 2A (2Apro). In the case of the cardioviruses and aphthoviruses, the primary scission is also dependent upon 2A but occurs by a unique autocatalytic mechanism at the 2A/2B junction (36, 40). Although the first model proposed for the polyprotein processing of HAV resembled the enterovirus cleavage cascade (12), subsequent studies demonstrated that the only virally encoded proteinase, 3Cpro, was able to cleave in the middle of what was originally considered to be the HAV 2A coding region (19, 41). It was later demonstrated that the 2B nonstructural protein is considerably larger than that predicted by the original processing model, extending into the upstream sequences of the polyprotein. These studies demonstrated that the 2A polypeptide is smaller than originally predicted and that 3Cpro is responsible for the cleavage at the newly identified 2A/2B junction (17, 30). Although this cleavage results in an amino-terminal P1-2A segment that includes the three major capsid proteins, as well as a VP1-2A precursor that has been identified in capsid morphogenesis intermediates (9), it is not known whether this is the primary cleavage within the polyprotein or whether it follows other cleavages further downstream in the polyprotein. Consistent with this unique feature of HAV polyprotein processing, the HAV 2A polypeptide shares no amino acid sequence homology with any other picornaviral 2A protein. Furthermore, the function of the 2A protein of HAV remains unknown.

In addition to directing the primary cleavage of the polyprotein, the 2A protein of poliovirus is responsible for host protein synthesis shutoff, has a transactivating effect on the initiation of the translation of uncapped viral RNAs, and may also play a role in viral RNA replication (39). Although neither the enteroviral and rhinoviral nor the cardioviral and aphthoviral 2A proteins share any cis-active replication functions with other downstream segments of the polyprotein, this is not known to be the case for the HAV 2A protein. It is not known whether the integrity of the HAV polyprotein-coding sequence can be disrupted at this point without a significant loss of viral replication function. To investigate this possibility, we constructed a series of recombinant HAV genomes in which the polyprotein was functionally disrupted at the 2A/2B junction by the insertion of heterologous sequences. Unlike poliovirus, we found that HAV is unable to tolerate the insertion of a heterologous picornaviral IRES element at the site of the putative primary polyprotein cleavage. However, the in-frame insertion of protein-coding sequence at the 2A/2B junction resulted in replication-competent viruses. These results demonstrate that the P1-2A segment of the HAV polyprotein can be functionally dissociated from the remainder of the polyprotein, providing strong evidence that the 2A polypeptide does not function as a 2AB precursor protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Fetal rhesus kidney (FRhK-4) cells were used for rescue of infectious HAV following transfection with synthetic, genome-length RNA. The FRhK-4 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and a mixture of nonessential amino acids (Gibco BRL). African green monkey kidney cells (BS-C-1) were used for quantal radioimmunofocus assays (RIFA) to characterize the replication phenotype of recombinant HAVs and to determine the titer of virus stocks. These cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

Construction of dicistronic HAV plasmids.

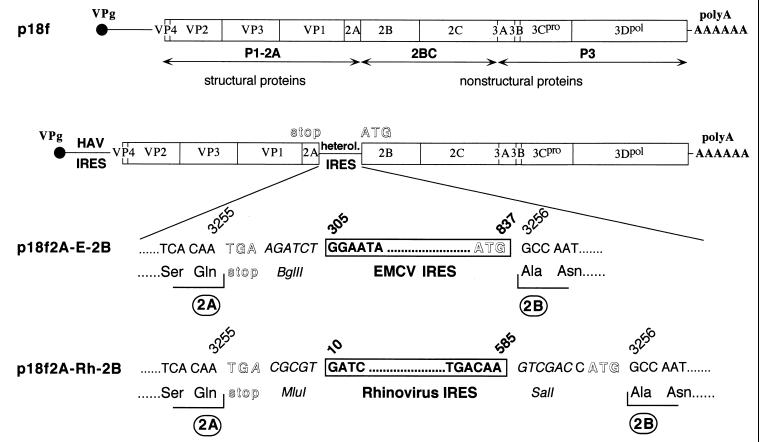

The parent recombinant HAV clone was a chimeric cDNA, p5′P2P3-18f (49) (hereafter referred to as p18f), containing the P1 segment of a relatively low-passage, cell culture-adapted variant of the HM175 strain of HAV, HAV/7 (12, 13), in the background of a rapidly replicating, cytopathic HM175 variant, v18f, inserted downstream of the SP6 RNA polymerase promoter (26). Recombinant cDNA clones representing dicistronic versions of this virus were constructed by an enzymatic inverse-PCR procedure adapted from the method described by Stemmer and Morris (44). Plasmid p18f2A-E-2B contains the EMCV IRES at the HAV 2A/2B junction, and p18f2A-Rh-2B contains the human rhinovirus (HRV) type 2 IRES. To construct p18f2A-E-2B, a DNA fragment corresponding to the EMCV IRES sequence, including the ATG initiating codon and corresponding to nucleotides (nt) 305 to 837 of the EMCV sequence, was amplified from pCITE (37) by PCR using the proofreading Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Boehringer) and primers designed to introduce BglII and BsaI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fragment, respectively. Upstream HAV sequence spanning nt 3000 to 3255 was amplified from p18f with a 5′ primer spanning the unique SacI restriction site at nt 3002 and a 3′ primer which introduced a stop codon immediately downstream of the sequence encoding 2A followed by a BglII restriction site. The downstream HAV sequence representing nt 3256 to 4998 was amplified with a 5′ primer introducing a BsaI restriction site preceding the 2B-encoding sequence and a 3′ primer spanning the EcoRI unique restriction site (at nt 4990). A similar strategy was used to introduce the rhinovirus 2 IRES (nt 10 to 585), amplified from plasmid pXLJ-HRV2 (5) at the HAV 2A/2B junction, except that BsaI restriction sites were introduced at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the IRES, respectively, and a BsaI site was added to the 3′ terminus of the upstream HAV sequence. In both cases, the 3 DNA fragments were ligated in vitro. The resulting HAV SacI-EcoRI fragment containing the IRES insertion was reintroduced into the backbone of p18f after DNA sequencing to exclude spurious mutations, giving rise to the full-length HAV cDNA containing plasmids p18f2A-E-2B (EMCV IRES) and p18f2A-Rh-2B (HRV IRES) (see Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the genetic organization of HAV dicistronic genomes. Inserted foreign nucleotide sequences from either EMCV (p18f2A-E-2B) or Rhinovirus (p18f2A-Rh-2B) IRESs are shown below the scheme of dicistronic HAV genomes interrupted at the 2A/2B junction. Positions of HAV and EMCV or rhinovirus nucleotides within respective genomes are indicated above the sequences, and encoded amino acids, when appropriate, are shown below the nucleotide sequences. Stop and initiation codons are indicated in an open font.

Construction of recombinant HAV plasmids with heterologous protein-coding sequences at the 2A/2B junction.

Recombinant viral genomes were created within the background of the plasmid pT7-18f, which was constructed by placing the genome-length HAV cDNA sequence of p18f downstream of a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The plasmid p18f2A-Zeo-2B contains the sequence encoding the bleomycin resistance protein (Zeo) (Invitrogen) inserted at the 2A/2B junction of pT7-18f, flanked on each side by consensus 3Cpro cleavage sites, and a Gly-Gly-Gly linker in an effort to increase polypeptide chain flexibility and enhance 3Cpro cleavage (4) (see Fig. 3). To construct this plasmid, a fragment representing the HAV sequence from the SacI site at nt 3002 to the 2A/2B junction at nt 3237, with an XbaI site introduced immediately downstream of the 3Cpro cleavage site, was amplified by PCR using Klen Taq DNA polymerase (Clontech). A second fragment representing the Zeo sequence was amplified from the plasmid pSVZeo (Invitrogen), with XbaI and BamHI sites introduced at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, and additional nucleotides encoding the three glycine residues introduced between the XbaI site and the Zeo sequence. These PCR products were ligated into pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene) to produce pSKHAV-Zeo. HAV sequence spanning the 2A/2B junction from nt 3244 to the unique PflMI site at nt 4238 was amplified using HAV-specific primers designed to introduce BamHI and EcoRI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the fragment, respectively, with a Gly-Gly-Gly linker introduced between the BamHI site and the 3Cpro cleavage site. This PCR fragment was ligated into pSKHAV-Zeo to generate pSK2A-Zeo-2B, which contains HAV cDNA sequence spanning nt 3002 to 4238 with the Zeo gene inserted at the 2A/2B junction and flanked by homologous 3Cpro cleavage sites. The SacI-PflMI fragment from pSK2A-Zeo-2B was subsequently ligated into the related sites of pT7-18f to produce the full-length recombinant HAV plasmid p18f2A-Zeo-2B. All PCR-amplified fragments were sequenced to exclude spurious mutations prior to their reintroduction into the background of pT7-18f.

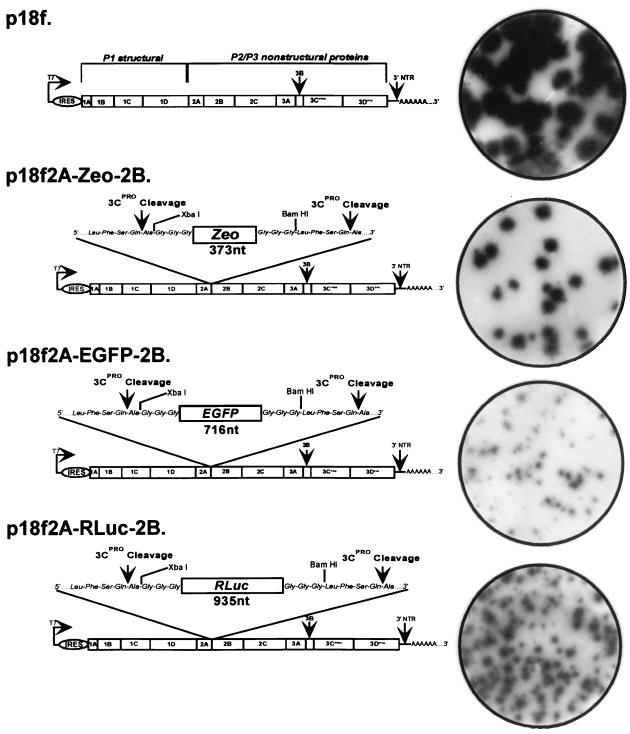

FIG. 3.

Genetic organization and RIFA of HAV recombinants containing insertions at the 2A/2B junction. The genetic organization of the genome of parental p18f and of HAV recombinants bearing insertions at the 2A/2B junction of foreign sequences coding for either the Zeo sequence (p18f2A-Zeo-2B), EGFP (p18f2A-EGFP-2B), or Rluc (p18f2A-Rluc-2B) is schematically shown. The 3Cpro cleavage sites and Gly-Gly-Gly hinges, as well as the position of unique restriction sites XbaI and BamHI, are indicated. Petri dish cultures of BS-C-1 cells were infected with 2-week-old lysates of FRhK-4 cells transfected with either parental or recombinant synthetic genome-length RNA and maintained for 1 week at 37°C before being processed for detection of HAV radioimmunofoci as described in Materials and Methods.

Recombinant HAV plasmids containing heterologous sequences representing the sequence spanning the E1 and E2 envelope protein junction and the E2 hypervariable region of hepatitis C virus (HCV) (genotype 1b; nt 1409 to 1652), green fluorescent protein (EGFP) of Aequorea victoria (Clontech), and the Renilla luciferase sequence (Rluc) (Promega) inserted at the 2A/2B junction were similarly constructed, following amplification of these sequences by PCR with primers that introduced XbaI and BamHI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The primers also encoded three glycine residues at each end of the heterologous sequence, as described above. The Zeo sequence was removed from pSK2A-Zeo-2B by XbaI and BamHI digestion and replaced with these PCR-amplified sequences to produce pSKHCV, pSKEGFP, and pSKRluc. cDNA fragments containing the inserted sequence were reintroduced into pT7-18f as described above, generating p18f2A-HCV-2B, p18f2A-EGFP-2B, and p18f2A-Rluc-2B.

In vitro translation reactions.

In vitro RNA transcription and translation reactions were carried out as described previously (14). Purified plasmid DNAs were digested with HaeII (50 μg/ml) and transcribed in vitro using SP6 RNA polymerase (Promega) in the presence of 40 μCi of [α-32P]UTP/ml (>400 Ci/mmol) (Amersham). The yield of RNA was deduced from the percentage of radioactivity incorporated, and the quality of the RNA was evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA transcripts (10 μg/ml) were translated in vitro for 3 h at 30°C in 85% Flexi rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) containing 0.6 mCi of [35S]methionine/ml, 65 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM MgCl2. The translation reactions were terminated by 15 min of incubation with 10 μg of pancreatic RNase/ml, followed by 10-fold dilution in Laemmli sample buffer. Alternatively, 20 μg of plasmid DNAs/ml was transcribed and translated in the TNT-coupled SP6 transcription-translation reactions (Promega) in the presence of 1.2 mCi of [35S]methionine/ml, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reaction products were immunoprecipitated with specific anti-HAV antibodies and Sepharose-protein A, as previously described (30).

Rescue of infectious virus from synthetic RNAs.

Full-length HAV RNA was transcribed from p18f with SP6 RNA polymerase and transfected into FRhK-4 cells by a liposome-mediated method as described previously (29). Full-length HAV RNA was transcribed from pT7-18f with T7 RNA polymerase (T7 Megascript kit; Ambion) in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μl of HAV cDNA digested with SmaI. RNA yields were monitored in 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS)–agarose gels. For transfections, equal quantities of RNA were added to 30 μl of lipofectin (Gibco BRL) in a total volume of 100 μl adjusted with Optimem (Gibco BRL) and added dropwise to nearly confluent monolayers of FRhK-4 cells in 60-mm-diameter dishes. Twelve to 14 days following transfection, cells were mechanically scraped into 3 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles, and extracted with an equal volume of chloroform. Harvested virus was stored at −70°C and assayed by RIFA.

RIFA for HAV.

Lysates of transfected or infected cells were assayed for infectious HAV by RIFA in BS-C-1 cells as described previously (24). Infected cells were maintained at 37°C for 6 to 7 days before processing.

RT-PCR of viral RNA.

Viral RNA was isolated from virus by phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitated with ethanol. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was carried out using the Titan One Tube RT-PCR kit (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer's suggested procedure. The positions of the primers for these reactions were as follows: for primer 1 (Zeo specific), nt 95 to 115; for primer 2 (HAV specific), nt 3001 to 3026; and for primer 3, nt 3537 to 3577.

RNA hybridization.

RNA isolated from v18f and recombinant v18f2A-Zeo-2B was subjected to dot blot hybridization analysis. Following the removal of residual DNA by digestion with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega), the viral RNA was applied to nitrocellulose using a vacuum-assisted manifold (Bio-Rad) and hybridized under standard conditions to 32P-labeled probes representing either the Zeo sequence or the 2A/2B region of HAV.

Immunoblot detection of HAV proteins.

Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared at 72 h postinfection (p.i.) from HAV-infected cells by lysis in 200 μl of a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 25 μg of aprotinin per ml. A 10- to 20-μl aliquot was subjected to SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), followed by transfer onto Hybond-N membranes (Amersham). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-VP1 or anti-VP2 guinea pig antibodies diluted 1:4,000 and 1:16,000, respectively, or anti-2B rabbit antibody diluted 1:50,000, in PBS-T containing 1% bovine serum albumin. Following four washes in PBS-T, the membrane was incubated with secondary anti-guinea pig or anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) diluted in PBS-T containing 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. Following four additional washes with PBS-T, the HAV polypeptides were visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL Plus; Amersham).

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy.

FRhK-4 cells grown in Permanox chamber slides (Nunc) were infected with virus and incubated for 3 to 4 days at 37°C, followed by fixation with cold acetone for 30 min. Cells were air dried and rehydrated in PBS before staining with either a neutralizing monoclonal anti-HAV antibody, K3.2F2 (28), diluted 1:400, or rabbit antibody to the bleomycin resistance protein (Zeo), diluted 1:250 (Cayla, Toulouse, France). Specific antibody binding was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse (Sigma) or goat anti-rabbit (Sigma) secondary antibodies at dilutions of 1:64 and 1:164, respectively. Fluorescence was observed with a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope.

RESULTS

Construction and in vitro characterization of dicistronic HAV genomes containing a heterologous IRES sequence inserted at the 2A/2B junction.

As a first step in determining whether the HAV 2A polypeptide plays a functional role in the viral life cycle that is independent of the downstream, 2BC-P3 nonstructural polypeptide precursor, we constructed a dicistronic HAV genome designed to uncouple the synthesis of the P1-2A and 2BC-P3 segments of the polyprotein. P18f2A-E-2B contains nt 305 to 837 of the 5′ noncoding region of the EMCV genome, inserted between the 2A and 2B polypeptide sequences of HAV, preceded by a stop codon (Fig. 1). This EMCV sequence contains a functional IRES (15), as well as the AUG initiation codon of the EMCV polyprotein, which was placed in frame with the HAV sequence immediately upstream of the first codon of 2B. The EMCV IRES was chosen for its high efficiency in directing the internal initiation of translation of downstream protein-coding sequences, both in vitro (6) and in vivo (8, 47). The dicistronic genome was constructed by enzymatic inverse PCR mutagenesis of an infectious molecular clone of a rapidly replicating, cell culture-adapted HAV variant, p18 (49), as described in Materials and Methods. p18f contains a hybrid, genome-length cDNA in which the 5′ terminal nontranslated RNA, P2, and P3 segments are derived from the rapidly replicating HM175/18f virus (26) and the P1 and 3′ noncoding segments are derived from the cell culture-adapted HM175/p35 virus (12), under control of the SP6 RNA polymerase promoter. The SacI-EcoRI HAV restriction fragment (nt 3002 to 4995) bearing the PCR-amplified EMCV insertion was sequenced in order to exclude spurious mutations prior to its reintroduction into the background of this infectious molecular clone.

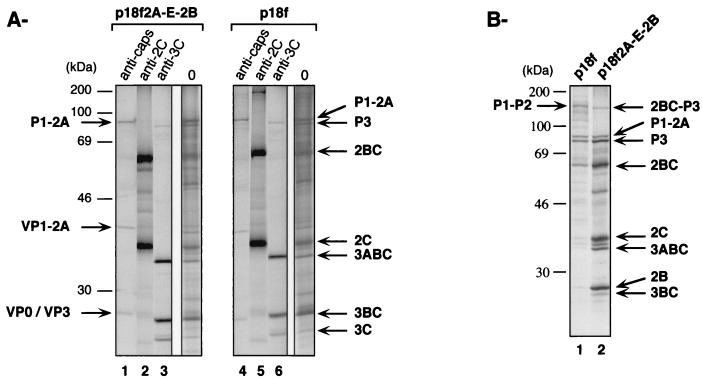

The ability of dicistronic viral RNA derived from p18f2A-E-2B to direct the synthesis of two polyproteins under the separate control of the HAV and EMCV IRES elements, respectively, was assessed in vitro in comparison with the translation of RNA transcripts derived from the parental p18f plasmid. The products of coupled transcription-translation reactions carried out in rabbit reticulocyte lysates programmed with these dicistronic and monocistronic plasmids were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for various HAV proteins. These results indicated that both cistrons were translationally active in the dicistronic construct (Fig. 2). The precursor polypeptide P1-2A, derived from the first cistron in which translation was driven by the HAV IRES, as well as its 3Cpro-derived products, VP1-2A, VP0, and VP3, were present following immunoprecipitation with anticapsid antibodies (Fig. 2A, lane 1). Translation of the second cistron of the dicistronic transcript, under the control of the EMCV IRES, resulted in the production of the precursor polypeptides P3 and 2BC, as well as mature, 3Cpro-derived proteins, including 2C and 3C, as shown by immunoprecipitation with anti-2C or anti-3C antibodies (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). Importantly, proteins produced from the dicistronic cDNA were qualitatively similar to those produced from the monocistronic, parental construct (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 1 to 3 with lanes 4 to 6). Thus, the same precursors and cleavage products were observed from mono- or dicistronic templates.

FIG. 2.

In vitro translation and processing of polyproteins synthesized from dicistronic transcript p18f2A-E-2B. (A). Coupled TNT transcription-translation reactions (Promega) were programmed with 1 μg of HaeII-linearized plasmids containing either full-length parental HAV cDNA (p 18f) or full-length HAV dicistronic cDNA (p18f2A-E-2B). [35S]methionine-labeled HAV proteins were separated by SDS–10% PAGE either directly (lanes 0) or following immunoprecipitation with anti-HAV capsid (anti-caps), anti-HAV 2C (anti-2C), or anti-HAV 3C (anti-3C) antibodies. Positions of molecular mass standards and of precursors and mature HAV polypeptides are indicated. (B) Rabbit reticulocyte lysate reactions were programmed with 100 ng of either full-length parental HAV transcript (p18f) or full-length HAV dicistronic transcript (p18f2A-E-2B). [35S]methionine-labeled HAV proteins were separated by SDS–10% PAGE. Positions of molecular mass standards are indicated on the left of the panel, and positions of precursors and mature HAV polypeptides, as determined after immunoprecipitation with appropriate antibodies (not shown), are indicated on each side of the panel.

In coupled transcription-translation reactions, no difference could be noted in the quantities of nonstructural polypeptides produced under control of the HAV or the EMCV IRES (Fig. 2A). However, when rabbit reticulocyte lysates were programmed with known amounts of the mono- and dicistronic RNA transcripts, significantly more 2BC and P3-related polypeptides were synthesized from the dicistronic RNA transcript than from the monocistronic transcript (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 1 and 2). This is in agreement with the fact that the EMCV IRES is substantially more efficient than the HAV IRES (6, 47). In addition to the precursor P1-2A, a P1-P2 precursor was also present in the in vitro translation products from 18f transcripts (Fig. 2B, lane 1). This was immunoprecipitated with either anticapsid, anti-2A, or anti-2C antibodies (data not shown). This precursor is derived from 3Cpro cleavage at the 2C/3A junction. No other precursor spanning the 2A/2B junction (such as 2AB or P2) was ever observed. Although the presence of the P1-P2 precursor has been documented only in in vitro studies, the presence of HAV proteins is difficult to demonstrate in infected cells, and it is unclear whether it plays a role in the HAV life cycle. This P1-P2 precursor is disrupted by the introduction of the EMCV IRES at the 2A/2B junction (Fig. 2B, lane 2). However, as mentioned above, further cleavage of the precursors gave rise to qualitatively similar products in both mono- and dicistronic constructs (Fig. 2).

Altogether, the in vitro analyses demonstrated that both the HAV and EMCV IRES elements were functional in the dicistronic construct and that the insertion of the exogenous sequence and subsequent functional disruption of the polyprotein did not appear to alter its subsequent proteolytic processing, at least in vitro.

Dicistronic HAV genomes are not infectious in FRhK-4 cells.

Despite the translational activity of the dicistronic RNA transcripts that is demonstrated in Fig. 2, infectious virus could not be rescued following transfection of permissive FRhK-4 cells with transcripts derived from p18f2A-E-2B. Fresh cells inoculated with lysates of transfected cells did not develop viral replication foci identifiable by RIFA. In contrast, transfection of dicistronic poliovirus RNA transcripts containing an identical EMCV IRES insertion, at either the 1D/2A or the 2A/2B junction, gave rise to viable polioviruses (data not shown). The latter result indicates that the EMCV IRES is functional in FRhK-4 cells, similar to previous demonstrations of its activity in HeLa cells transfected with dicistronic poliovirus RNA (7, 32, 33). Thus, the failure to recover infectious HAV from the dicistronic p18f2A-E-2B RNA cannot be attributed to a lack of activity of the EMCV IRES in these cells.

An alternative explanation for the lack of infectivity of the dicistronic transcript could be a deleterious imbalance in the strengths of the different IRES elements that direct translation of proteins from the two cistrons. Indeed, the HAV IRES has been shown to be manyfold less efficient than the EMCV IRES in driving translation of a reporter gene in transfected cells (8, 47). Unfortunately, only a low level of HAV translation is obtained in cell cultures transfected with genome-length RNAs, preventing accurate quantitation of viral protein expression. We therefore constructed a second dicistronic HAV genome in which the HRV type 2 (nt 10 to 585) IRES was inserted at the 2A/2B junction (see Materials and Methods). Among different picornaviral IRES elements, the HRV IRES has been shown to be closest to the HAV IRES in terms of its translation efficiency in various cell lines, including FRhK-4 cells (8). Although in vitro translation assays demonstrated the activity of both the HAV and HRV IRES elements in this dicistronic construct (data not shown), transfection of FRhK-4 cells with this second genome-length dicistronic RNA also failed to give rise to viable HAV. This result suggests that the lack of infectivity of the dicistronic p18f2A-E-2B genome is not due to a quantitative imbalance in the abundance of proteins synthesized from the two cistrons.

The low abundance of newly synthesized negative- or positive-strand viral RNA compared with the high background of transfected positive-strand RNA renders it impossible to detect new viral RNA synthesis within a single growth cycle following transfection of cells with the parental p18f RNA transcript. We were unable to detect positive-strand RNA when this was monitored by hybridization with a 32P-labeled riboprobe (data not shown). Unfortunately, even rTth-based RT-PCR assays lack strand specificity sufficient for reliable detection of negative-strand RNA in cells transfected with large amounts of positive-sense RNA (22). Therefore, we were not able to determine whether the insertion of the foreign IRES element impaired replication of the dicistronic viral RNA or the lack of infectivity was due to interference of later stages in the virus life cycle.

Monocistronic HAV recombinants containing protein-coding sequence inserted at the 2A/2B junction.

Among other possibilities, the failure to rescue infectious HAV from these dicistronic RNA transcripts could be due to an essential 2A function occurring in cis with the downstream nonstructural proteins. To assess this possibility, we constructed a genome-length cDNA in which the integrity of the polyprotein was disrupted by the in-frame insertion of an exogenous protein coding sequence at the 2A/2B junction. Sequence encoding the bleomycin resistance protein (Zeo) was chosen because of its relatively small size (373 nt) and because the expression of this protein would potentially allow for positive selection of recombinant RNAs undergoing replication in transfected cell cultures. The Zeo sequence was inserted into the genome-length HAV cDNA using PCR mutagenesis, as described in Materials and Methods, to generate the plasmid p18f2A-Zeo-2B (Fig. 3). p18f2A-Zeo-2B contains the Zeo sequence inserted in-frame between the HAV 2A and 2B sequences, flanked by homologous Leu-Phe-Ser-Gln∗Ala 3Cpro cleavage sites (30) and Gly-Gly-Gly spacers in an effort to enhance polypeptide chain flexibility and 3Cpro-mediated cleavage of Zeo from the polyprotein (4).

In contrast to the failure of dicistronic HAV RNA to give rise to infectious virus following transfection of FRhK-4 cells, transfection with RNA synthesized in vitro from p18f2A-Zeo-2B resulted in viable virus as determined by subsequent RIFA of cell lysates in permissive BS-C-1 cells. However, in comparison to the parental virus, replication of v18f2A-Zeo-2B was moderately impaired, as evidenced by the fact that replication foci were ∼30 to 40% smaller in diameter than those of the parental virus in RIFA (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the yield of virus rescued following transfection of FRhK-4 cells was approximately 100-fold to 1,000-fold less than that recovered following transfection with the parental RNA.

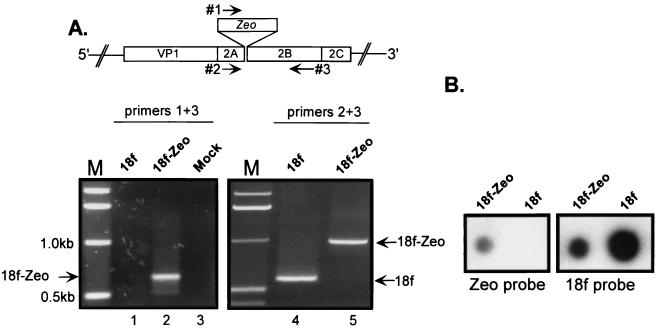

We confirmed the presence of the Zeo sequence in the virus rescued from cells transfected with RNA derived from p18f2A-Zeo-2B by RT-PCR of RNA extracted from virus recovered after the first passage in cell culture. Using HAV-specific primers that spanned the inserted Zeo sequence, a 980-bp product was obtained from RNA extracted from v18f2A-Zeo-2B, in contrast to the expected 577-bp product obtained from the parent virus (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 5 and 4). In addition, a specific PCR product was obtained only from RNA extracted from v18f2A-Zeo-2B, and not the parental virus, when one primer was derived from the Zeo sequence and the other was complementary to HAV (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1 and 2). To eliminate the possibility that these specific RT-PCR signals could reflect transfected RNA, we extracted RNA from v18f2A-Zeo-2B particles that had been passaged twice in cell culture. RNA was bound to a nitrocellulose membrane and hybridized with a Zeo-specific probe. This resulted in a specific signal only with RNA extracted from the v18f2A-Zeo-2B recombinant HAV and not with that from the v18f parental virus (Fig. 4B). Thus, in contrast to the lack of infectivity of recombinant genomes in which a heterologous picomaviral IRES was inserted at the 2A/2B junction, the in-frame insertion of a foreign coding sequence at the 2A/2B junction is tolerated by the HAV genome. However, the smaller size of the v18f2A-Zeo-2B replication foci in RIFA and lesser yield of virus following transfection of p18f2A-Zeo-2B-derived RNA suggest that v18f2A-Zeo-2B has a reduced replication capacity.

FIG. 4.

Retention of the Zeo gene in v18f2A-Zeo-2B after two passages in BS-C-1 cells. (A) The genome of either the parent (v18f) or v18f-Zeo-2B (18f-Zeo) recombinant virus, after two successive passages in BS-C-1 cells, was analyzed by RT-PCR using two different pairs of primers as schematically depicted. The left panel represents RT-PCR products obtained using oligonucleotide 1, which is derived from the Zeo sequence, and HAV-specific oligonucleotide 3. The right panel shows RT-PCR products obtained using two HAV-specific oligonucleotides, 2 and 3, spanning the Zeo insertion. Fragments corresponding to v18f and 18f-Zeo sequences are indicated by an arrowhead. (B) Viral RNA isolated after two passages from BS-C-1 cells infected with either v18f or v18f2A-Zeo-2B (18f-Zeo) was bound to nitrocellulose and probed with a 32P-labeled probe specific either for the Zeo sequence or for HAV RNA.

Both the length and the type of the heterologous sequence inserted at the P1/P2 junction of the poliovirus genome may play an important role in determining the replication phenotype of recombinant polioviruses that are rescued from such RNAs (45). To determine whether this is also the case for HAV, we inserted several different protein-coding sequences at the 2A/2B junction of p18f2A-Zeo-2B in lieu of the Zeo sequence (Table 1). These included sequence encoding the E1/E2 junction and a segment of the HCV envelope proteins (291 nt), EGFP (765 nt), or Renilla luciferase (Rluc) (984 nt). Each was inserted at the 2A/2B junction with flanking Gly-Gly-Gly spacers and 3Cpro cleavage sites as with p18f2A-Zeo-2B (Fig. 3). RNA transcripts derived from p18f2A-EGFP-2B and p18f2A-Rluc-2B gave rise to replication-competent viruses following transfection into FRhK-4 cells, as shown by subsequent RIFA of FRhK-4 cell lysates in BS-C-1 cells (Fig. 3). However, infectious virus was not recovered following transfection with RNA derived from v18f2A-HCV-2B. Both of the viable HAV recombinants generated replication foci that were significantly smaller than those of either the parent v18f virus or the Zeo recombinant, v18f2A-Zeo-2B (Fig. 3), indicating that the insertion of these exogenous sequences had a significant negative effect on HAV replication. Since the HCV recombinant, p18f2A-HCV-2B, contained the shortest length of inserted heterologous sequences, these results suggest that the nature of the inserted sequence may be more important than its length in determining the infectivity of such recombinant genomes. Interestingly, the 291-nt insertion in this construct encodes the carboxy-terminal signal sequence of the HCV E1 protein. It is possible that this may have been responsible for the defective nature of the recombinant RNA (see Discussion).

TABLE 1.

HAV 2A/2B sequence insertions

| Construct | Insertion | Sizea

|

Infectivity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nt | AA | |||

| p18f2A-E-2B | EMCV IRES | 543 | NA | − |

| p18f2A-Rh-2B | Rhinovirus type 2 IRES | 594 | NA | − |

| p18f2A-HCV-2B | HCV E2 HVR | 291 | 97 | − |

| p18f2A-Zeo-2B | Bleomycin | 420 | 140 | + |

| p18f2A-EGFP-2B | EGFP | 765 | 255 | + |

| p18f2A-RLuc-2B | Rluc | 984 | 328 | + |

Includes additional sequence required for 3CPRO cleavage and cloning. AA, amino acids.

The insertion of heterologous protein-coding sequence at the 2A/2B junction does not affect polyprotein processing.

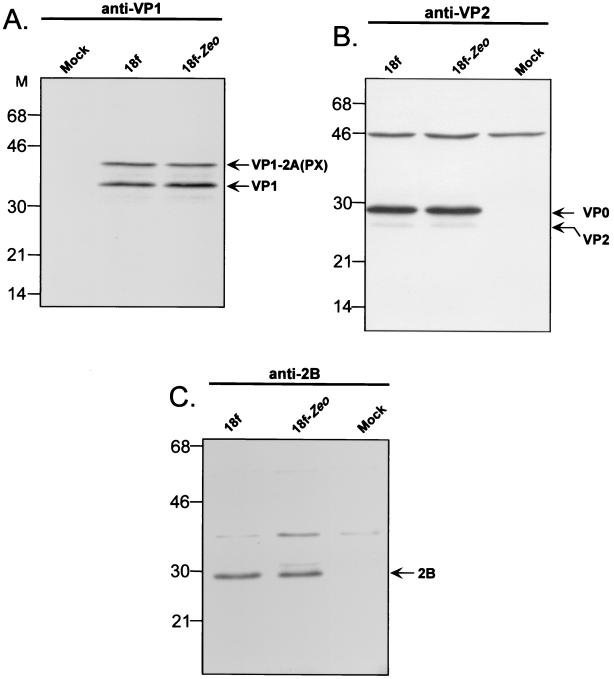

The experiment shown in Fig. 2A suggests that the processing of the HAV polyprotein was not altered by the introduction of an IRES element at the 2A/2B junction. However, the reduction we observed in the replication capacities of recombinant HAV genomes containing inserted protein-coding sequences at this site could reflect altered efficiency of the polyprotein processing as a result of the foreign insertion. To investigate this possibility, cytoplasmic extracts obtained 72 h following the infection of FRhK-4 cells with the parent virus, v18f, or the Zeo recombinant, v18f2A-Zeo-2B, were subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies directed against VP1, VP2, or 2B (Fig. 5). The 2A polypeptide was first released in the form of a VP1-2A precursor (PX protein) that undergoes subsequent cleavage, most likely by a cellular proteinase, to produce the mature VP1 protein (18, 29). At 72 h p.i., polypeptides VP1-2A (Fig. 5A) and 2B (Fig. 5C) were present in lysates of cells infected with v18f2A-Zeo-2B and had electrophoretic mobilities similar to those of the equivalent polypeptides in v18f-infected cells. This shows that both 3Cpro cleavage sites encompassing the Zeo inserted sequence are recognized and processed by HAV 3Cpro. In addition, the abundances of the VP1-2A precursor and the mature VP1 protein (Fig. 5A), the VP0 capsid precursor protein and the mature VP2 protein (Fig. 5B), and the mature 2B protein (Fig. 5C) were similar in cells infected with either virus. Thus, the modestly reduced replication capacity of v18f2A-Zeo-2B cannot be attributed to qualitative changing of the processing of the viral polyprotein due to insertion of a foreign sequence at the 2A/2B junction.

FIG. 5.

The recombinant HAV v18f2A-Zeo-2B shows no defect in HAV polyprotein processing. Cytoplasmic extracts at 72 h p.i. from uninfected, v18f-infected, or v18f2A-Zeo-2B (18f-Zeo)-infected FRhK-4 cells were prepared and were separated by SDS–12% PAGE. HAV polypeptides were identified by immunoblotting using anti-VP1 (A), anti-VP2 (B), or anti-2B (C) antibodies. Positions of molecular weight markers (M) and relative positions of HAV polypeptides are shown on the left and the right of each panel, respectively.

Expression of foreign proteins from recombinant HAV.

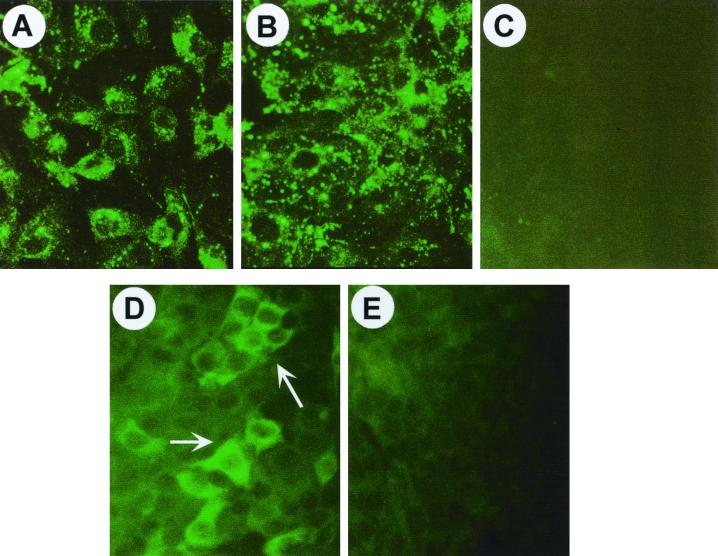

To determine whether the foreign RNA sequences included in the viable monocistronic recombinant viruses were expressed as proteins in infected cells, infected FRhK-4 cells were examined using indirect immunofluorescence for expression of Zeo, direct immunofluorescence for expression of EGFP, or enzymatic assay for detection of Rluc. In addition, the expression of HAV polypeptides in these cells was monitored by indirect immunofluorescence using a monoclonal anticapsid antibody. As expected, HAV antigen was present, as evidenced by characteristic cytoplasmic fluorescence 4 days after infection with either the parent virus, v18f, or the recombinant, v18f2A-Zeo-2B (Fig. 6A and B). No HAV antigen was present in mock-infected cells (Fig. 6C). When cells were stained with a polyclonal antibody raised against the Zeo protein, specific cytoplasmic fluorescence was also detected in FRhK-4 cells infected with v18f2A-Zeo-2B (Fig. 6D) but not in v18f-infected cells (results not shown) or mock-infected cells (Fig. 6E). Unlike the punctate nature of the HAV-specific fluorescence, staining for Zeo was diffuse throughout the cytoplasm (compare Fig. 6B and D). These data confirm that recombinant HAV can mediate the expression of foreign polypeptides inserted at the 2A/2B junction.

FIG. 6.

Immunofluorescence analysis of v18f- and v18f2A-Zeo-2B-infected FRh-K4 cells. Monolayers of FRhK-4 cells grown in four well chamber-slides were either infected with v18f (A) or v18f2A-Zeo-2B (B and D) or mock infected (C and E), fixed in acetone at 4 days p.i., and incubated with the anti-HAV monoclonal antibody K3.2F2 (A, B, and C) or a rabbit polyclonal anti-Zeo antibody (D and E). Specific antigens were visualized using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit antisera.

We next investigated the expression of EGFP and Rluc from the corresponding recombinant HAV variants. Consistent with the reduced replication capacity of these viruses that is evident in Fig. 3, only weak HAV-specific fluorescence was observed in cells 4 days after infection with these recombinant viruses (results not shown). However, we were unable to detect either specific fluorescence for EGFP or significant Rluc activity in FRhK-4 cells at any time following infection with v18f2A-EGFP-2B or v18f2A-Rluc-2B. Furthermore, no EGFP or Rluc expression was detected in FRhK-4 cells 14 days following transfection with RNA transcribed from p18f2A-EGFP-2B or p18f2A-Rluc-2B. This suggests that these foreign sequence insertions are very unstable and may be lost from the viral genome very quickly after the initiation of HAV replication.

Stability of heterologous protein-coding sequence insertions at the 2A/2B junction.

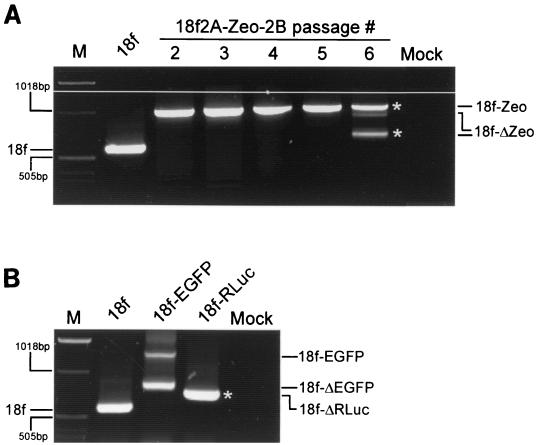

To further examine the genetic stability of the foreign protein-coding sequences inserted at the 2A/2B junction, we monitored the presence of the inserted sequences during serial passage of the rescued recombinant viruses. Viruses were rescued from RNA in FRhK-4 cells and then passaged up to six times in BS-C-1 cells. Each passage was initiated by inoculation of fresh BS-C-1 cells with cell-associated virus derived from the preceding passage, followed by 5 to 7 days of incubation. Viral RNA was isolated at each passage level, and RT-PCR was carried out using primers that flank the insertion site. These results indicated that the Zeo insertion was stably maintained in v18f2A-Zeo-2B for approximately five passages (in the absence of any antibiotic selection), since only a single, distinct RT-PCR product was obtained, with a size consistent with retention of the complete Zeo sequence (Fig. 7A). However, following the fifth passage, a second RT-PCR product was generated from viral harvests that was significantly smaller than that produced from the first-passage v18f2A-Zeo-2B yet still larger than that generated from the parent, v18f. This suggests that recombination events had occurred by the sixth passage, leading to the selection of virus from which the introduced sequence had been partially deleted.

FIG. 7.

Analysis of the stability of recombinant HAV genomes. BS-C-1 cells were mock infected or infected with either HAV parent v18f or v18f2A-Zeo-2B (18f-Zeo) (A) or v18f2A-EGFP-2B (18f-EGFP) or v18f2A-Rluc-2B (18f-Rluc) (B). The presence of foreign sequence insertions in the genomes of recombinant viruses obtained after six passages (A) or only one passage (B) in BS-C-1 cells was determined by RT-PCR using primers 2 and 3, as depicted in Fig. 4A. Molecular size markers (M) indicate relative mobilities. Fragments corresponding to the parent genome (v18f) are shown on the left, and fragments representing complete and partially deleted recombinant genomes are indicated on the right of each panel. Fragments noted with an asterisk were purified for sequence analysis (see Fig. 8).

In contrast, the EGFP and Rluc insertions were far less stable, with RT-PCR products that were substantially smaller than those expected from virus that had undergone only a single passage in BS-C-1 cells (Fig. 7B). A second, relatively minor RT-PCR product consistent with retention of the complete insertion was produced from lysates of cells infected with v18f2A-EGFP-2B. However, this was not the case with cells infected with v18f2A-Rluc-2B, in which only a single RT-PCR product was observed. In both cases, however, the dominant RT-PCR products were larger than that produced from v18f, indicating the retention of at least part of the insertion. These results are consistent with the protein expression data described above and suggest that the insertion of foreign sequences exceeding 700 nt (approximately 9% of the length of the HAV genome) results in genomic instability and rapid loss of the inserted sequence.

Recombinant poliovirus genomes containing repeat sequences flanking foreign gene insertions at the 1D/2A junction have also been shown to be unstable, undergoing relatively rapid deletion of the inserted sequences (45). The introduction of silent mutations within the repeat sequences resulted in significantly increased genetic stability, suggesting that homologous recombination plays an important role in the instability of recombinant poliovirus genomes. However, in the case of insertions in the HAV genome, the fact that the major RT-PCR products from each of the recombinant viruses that had undergone deletion were larger than that produced from v18f (Fig. 7A and B) argued against the deletion being caused by homologous recombination at the flanking 3Cpro cleavage sites. If the deletion were caused by homologous recombination, these RT-PCR products should have been equivalent in size to those produced from v18f. Consistent with this interpretation, altering the nucleotide sequence of the 3Cpro cleavage site immediately upstream of the inserted sequence in p18f2A-Zeo-2B, without changing the encoded amino acid sequence, did not increase the stability of the inserted sequence. Indeed, despite a 33% difference in the sequences of the 3Cpro cleavage sites that flank the insertion, virus rescued from FRhK-4 cells transfected with the corresponding RNA transcripts also lost the Zeo sequence after approximately the fifth virus passage in BS-C-1 cells (results not shown).

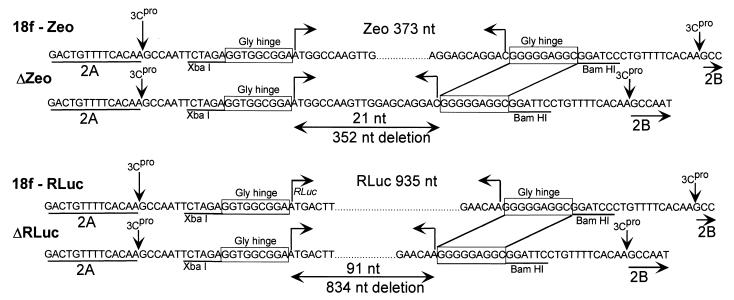

To further investigate deletion events at the nucleotide level, the smaller-than-expected RT-PCR products generated from sixth-passage v18f2A-Zeo-2B (Fig. 7A) and first passage v18f2A-Rluc-2B (Fig. 7B) were purified and subjected to nucleotide sequence analysis. The results revealed that the majority of the inserted sequence had been removed from v18f2A-Zeo-2B, leaving a residual 21-nt sequence derived from the Zeo sequence (Fig. 8A). The sequences flanking the insertion at either end of the Zeo sequence, including the homologous 3Cpro cleavage sites and the Gly-Gly-Gly hinge, were completely preserved. A similar deletion was present in the v18f2A-Rluc-2B genome, in which all but 93 nt of the 970 nt of the RLuc sequence had been deleted, leaving the flanking regions intact, after one passage of the virus in BS-C-1 cells following its rescue from RNA in FRhK-4 cells. These results confirm that unlike the case with poliovirus, homologous recombination does not play a role in the deletion of exogenous sequence inserted within the HAV genome.

FIG. 8.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of revertant HAV recombinant genomes. RT-PCR products representing deletion events in the genomes of v18f2A-Zeo-2B (A) and v18f2A-Rluc-2B (B) (noted by an asterisk in Fig. 7) were gel purified and subjected directly to automated sequencing. The resulting sequences are shown in comparison to the input recombinant sequences. Sizes of the respective foreign sequences, as well as the size of the resulting deletion, are indicated.

DISCUSSION

The small, 8.3-kDa 2A polypeptide (71 amino acids) of hepatoviruses is completely distinct from other picornaviral 2A proteins, having neither any relatedness in its amino acid sequence nor any apparent associated proteinase activity (39). Neither we nor others have ever observed a mature form of 2A in HAV-infected cells, even when VP1 is present and fully processed. This is likely because the 2A sequence is not cleaved from VP1-2A as an intact entity, since anti-VP1-reactive proteins with electrophoretic mobilities intermediate between those of VP1-2A and VP1 are frequently detected in HAV-infected cells (2, 19, 29). The complete 2A sequence, and even the amino-terminal segment of 2A, thus appear to exist only as carboxy-terminal extensions of the VP1 capsid protein in some viral morphogenesis intermediates (2, 9; A. Martin, unpublished results). Consistent with a possible role for 2A in viral morphogenesis, recent results from our laboratory show that HAV mutants with deletions in the 2A sequence are defective in capsid protein assembly (L. Cohen, D. Benichou, and A. Martin, unpublished data).

To determine whether the 2A polypeptide also plays a role in the virus life cycle as part of a polyprotein precursor involving some or all of the downstream nonstructural proteins, we constructed a dicistronic HAV genome. This was designed to uncouple translation of the structural proteins (P1-2A segment) from that of the nonstructural proteins (2BC-P3) by inserting a heterologous IRES at the 2A/2B junction. We reasoned that a viable dicistronic HAV variant in which the polyprotein was functionally disrupted at the 2A/2B junction would be useful for studying the effect of deletions in the 2A sequence, since there would be no possibility that such deletions would alter the processing of the downstream nonstructural proteins. In addition, since translation has been suggested to be rate limiting for HAV replication (16, 43), we considered it possible that enhancing the translation of the nonstructural proteins by placing them under the control of a more efficient IRES might have a positive effect on HAV replication. However, such dicistronic HAV genomes, containing either the very efficient type 2 EMCV IRES or the much weaker rhinoviral type 1 IRES, were not infectious. The latter result suggests that the lack of infectivity was not due to an imbalance in the efficiency of internal initiation of translation of the two viral cistrons.

In contrast, although these results suggest the existence of an essential cis-active replication function spanning the 2A/2B junction, we found several recombinant HAV genomes containing in-frame insertions of foreign protein-coding sequences at this site to be replication competent (Fig. 3; Table 1). This suggests strongly that the failure of the dicistronic RNAs to undergo replication was not due either to the disruption of a cryptic cis-active function of 2A as an uncleaved precursor with the nonstructural proteins in virus replication or to disruption of an essential cis-active RNA element spanning the 2A/2B junction. Although it has never been formally demonstrated that the 2A/2B cleavage is the primary cleavage event, these results are consistent with that hypothesis (17, 19, 30, 42).

The lack of infectivity of dicistronic HAV genomes interrupted at the 2A/2B cleavage site contrasts with previous successful efforts to obtain both poliovirus (7, 32, 33) and rhinovirus dicistronic genomes (31) interrupted at the P1/P2 primary cleavage site. However, interestingly, attempts to construct viable cardioviruses with dicistronic genomes containing a second type 2 IRES insertion at the primary 2A/2B cleavage site have also failed. In this case, the lack of infectivity of the dicistronic genomes is believed to be the result of a cis competition between the two IRESs in directing translation (A. Palmenberg and M. Wu, personal communication). The lack of infectivity of dicistronic HAV genomes is probably not due to the sequestration of essential translation factors from the HAV IRES by the more powerful EMCV IRES, since dicistronic RNAs containing the much weaker HRV-2 IRES also were not viable. No defect in polyprotein processing was evident in translation studies carried out in vitro with these dicistronic RNAs (Fig. 2), but it is possible that the proteolytic cleavage cascade is functionally impaired in cells by artificially splitting the P1-2A and 2BC-P3 precursors. The cleavage of the 2A/2B junction by 3Cpro is unique to HAV among the picornaviruses. It is not known whether this occurs naturally within a P1-P2-P3, P1-P2–3ABC, or P1-P2 precursor. Although the dicistronic configuration of the RNA (Fig. 1) would result in the faithful expression of P1-2A, the folding of this precursor protein or that of the downstream 2BC-P3 segments might be altered by the fact that they are not translated as a continuous polypeptide chain. Alternatively, the lack of infectivity of the dicistronic HAV genomes may be due to the highly ordered secondary structure of the inserted IRES. This could result in the misfolding of RNA structures within the genome that are essential for replication or possibly impede the processivity of the viral replicase complex. Finally, we cannot completely exclude the unlikely possibility that the 2A protein functions in cis with one or more of the downstream nonstructural polypeptides, albeit in a manner that tolerates the insertion of foreign protein sequence at the 2A/2B junction.

v18f2A-Zeo-2B, which expresses the bleomycin resistance protein, Zeo, from heterologous sequence inserted at the 2A/2B junction, demonstrated a relatively robust replication phenotype based on the size of replication foci in RIFA (Fig. 3). The replication capacity of v18f2A-Zeo-2B was only modestly reduced compared with that of the parent, v18f, while other viable recombinant viruses containing the EGFP and Rluc sequence insertions were severely handicapped in replication, as suggested by the very small size of their replication foci in RIFA. Immunoblot analysis suggested that there was no impairment in the processing of the capsid proteins from the polyprotein, or in the processing of 2B from the downstream nonstructural region, in v18f2A-Zeo-2B (Fig. 5). These data indicate that the 3Cpro cleavage sites on either side of the insertion were recognized efficiently by the HAV proteinase, but we cannot exclude an effect of the inserted sequence on processing of the downstream nonstructural proteins in infected cells.

Apart from experiments demonstrating the viability of recombinant HAV variants possessing an in-frame insertion of short heterologous polypeptide sequences at the extreme 5′ end of the HAV open reading frame (50), there have been no other attempts to express foreign proteins from replicating HAV-based vectors. We have not determined the maximal length of the sequence insertion that can be tolerated by HAV at the 2A/2B junction, but our results suggest that it is somewhere between the 420-nt insertion in p18f2A-Zeo-2B and the 765-nt insertion in p18f2A-EGFP-2B. However, it is doubtful that the length of the insertion is the most important variable in determining the replication phenotype of variants with sequence inserted at the 2A/2B junction. Indeed, p18f2A-HCV-2B had the smallest insertion of any of the mutants we constructed but could not be rescued as virus following transfection into FRhK-4 cells. This was most likely due to the presence of the HCV E1 signal sequence at the N terminus of the inserted E2 hypervariable sequence. Signal sequence inserted as a part of foreign insertions in dicistronic poliovirus vectors were also found to abrogate replication. The signal sequence may anchor the polysome to the rough endoplasmic reticulum, preventing the viral RNA from assembling into membrane associated replication complexes (27). However, in monocistronic poliovirus (3, 45) and rhinovirus (G. Dollamier, N. Sharma, K. McKnight, and S. M. Lemon, unpublished data) expression vectors, insertion of foreign amino acid signal sequences has resulted in viable virus. Hence, many factors, such as the type of coding sequence or the strength of the signal sequence, may contribute to the fitness of picornavirus genomes expressing foreign genes. The v18f2A-EGFP-2B and v18f2A-Rluc-2B variants shown in Fig. 3 generated very small replication foci (indicating a severely handicapped replication phenotype) but retained residual sequence insertions much smaller than that present in v18f2A-Zeo-2B. Thus, it is apparent that the nature of the inserted sequence is much more important than its length in determining the replication capacity of these mutants.

Many positive-strand RNA viruses have a propensity to undergo genetic recombination (20, 21, 48), and it has been suggested that as many as 10 to 20% of progeny poliovirus RNA molecules may arise from homologous recombination events (20). This high rate of recombination during poliovirus replication frequently results in the removal of foreign sequences that have been inserted in the genome, since these sequences do not contribute positively to the fitness of the virus (1, 11, 27). Recombinant polioviruses containing homologous 3Cpro proteinase cleavage sites flanking such insertions are particularly prone to deletion of the inserted sequence by homologous recombination at these sites (45). Homologous recombination also occurs during the replication of HAV (26), but there are no data concerning the frequency of these events.

We found that the heterologous EGFP and Rluc sequences inserted in the recombinant v18f2A-EGFP-2B and v18f2A-Rluc-2B genomes were highly unstable. These sequences were deleted soon after rescue of the virus from RNA, as evidenced both by the absence of detectable expression of the foreign protein and by RT-PCR amplification of the viral RNA following rescue of the virus in FRhK-4 cells (Fig. 6). Surprisingly, however, these deletions did not arise by homologous recombination, as might be expected given the homologous flanking 3Cpro cleavage sites in these viral genomes (Fig. 3) and previous experience with poliovirus recombinants (45). Rather, the nucleotide sequences of these viral RNAs indicated that the insertions were only partially deleted (Fig. 7) and that the deletions were thus generated by a nonhomologous recombination mechanism. It is interesting that putative HAV defective interfering particles have been described that contain deletions predominantly in regions of the genome encoding the structural proteins (35). Presumably, such variants also result from nonhomologous recombination.

The potential utility of recombinant HAVs expressing heterologous proteins, either at the amino terminus of the polyprotein (50) or as an insertion at the 2A/2B junction as described here, remains to be defined. However, the cellular tropism of HAV makes possible the liver-specific expression of such proteins, from either attenuated or potentially wild-type viruses, and the availability of such viruses may ultimately prove useful for studying the pathobiology of hepatitis A. v18f2A-Zeo-2B is of particular interest, since the inserted sequence is relatively stable (Fig. 5), has only a modest impact on replication of the virus (Fig. 3), and encodes a positive, selectable antibiotic resistance marker. Under selective pressure of the antibiotic, bleomycin, the expression of this selectable marker should promote further adaptation of the virus to growth in cell culture. Should this approach be successful, it has the potential to generate new HAV variants with an enhanced capacity for replication in cultured cells that would be extremely useful for HAV vaccine production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Czeslaw Wychowski and Nicolas Escriou for helpful discussions and to Stephen Feinstone, Ellie Ehrenfeld, and Manfred Weitz for their generous gifts of anticapsid and anti-3C, anti-2C, and anti-2B antibodies, respectively. We also thank Andrew M. Borman for the plasmid pXLJ-HRV2, Shih-Fong Chao for pT7-18f, and Maria Chapa for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (RO1 AI32599 to S.M.L.), the Institut Pasteur, and the French CNRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander L, Lu H H, Wimmer E. Polioviruses containing picornavirus type 1 and/or type 2 internal ribosomal entry site elements: genetic hybrids and the expression of a foreign gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1406–1410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D A, Ross B C. Morphogenesis of hepatitis A virus: isolation and characterization of subviral particles. J Virol. 1990;64:5284–5289. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5284-5289.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson M J, Porter D C, Fultz P N, Morrow C D. Poliovirus replicons that express the gag or the envelope surface protein of simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(smm) PBj14. Virology. 1996;219:140–149. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andino R, Silvera D, Suggett S D, Achacoso P L, Miller C J, Baltimore D, Feinberg M B. Engineering poliovirus as a vaccine vector for the expression of diverse antigens. Science. 1994;265:1448–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.8073288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borman A, Jackson R J. Initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA: mapping the internal ribosome entry site. Virology. 1992;188:685–696. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90523-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borman A M, Bailly J L, Girard M, Kean K M. Picornavirus internal ribosome entry segments: comparison of translation efficiency and the requirements for optimal internal initiation of translation in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3656–3663. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borman A M, Deliat F G, Kean K M. Sequences within the poliovirus internal ribosome entry segment control viral RNA synthesis. EMBO J. 1994;13:3149–3157. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borman A M, Le Mercier P, Girard M, Kean K M. Comparison of picornaviral IRES-driven internal initiation of translation in cultured cells of different origins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:925–932. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borovec S V, Anderson D A. Synthesis and assembly of hepatitis A virus specific proteins in BS-C-1 cells. J Virol. 1993;67:3095–3102. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3095-3102.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown E A, Zajac A J, Lemon S M. In vitro characterization of an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) present within the 5′ nontranslated region of hepatitis A virus RNA: comparison with the IRES of encephalomyocarditis virus. J Virol. 1994;68:1066–1074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1066-1074.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao X, Wimmer E. Intragenomic complementation of a 3AB mutant in dicistronic polioviruses. Virology. 1995;209:315–326. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J I, Rosenblum B, Ticehurst J R, Daemer R J, Feinstone S M, Purcell R H. Complete nucleotide sequence of an attenuated hepatitis A virus: comparison with wild-type virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2497–2501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J I, Ticehurst J R, Feinstone S M, Rosenblum B, Purcell R H. Hepatitis A virus cDNA and its RNA transcripts are infectious in cell culture. J Virol. 1987;61:3035–3039. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3035-3039.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen L, Kean K M, Girard M, Van der Werf S. Effects of P2 cleavage site mutations on poliovirus polyprotein processing. Virology. 1996;224:34–42. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duke G M, Hoffman M A, Palmenberg A C. Sequence and structural elements that contribute to efficient encephalomyocarditis virus RNA translation. J Virol. 1992;66:1602–1609. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1602-1609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funkhouser A W, Schultz D E, Lemon S M, Purcell R H, Emerson S U. Hepatitis A virus translation is rate-limiting for virus replication in MRC-5 cells. Virology. 1999;254:268–278. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gosert R, Cassinotti P, Siegl G, Weitz M. Identification of hepatitis A virus non-structural protein 2B and its release by the major virus protease 3C. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:247–255. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-2-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graff J, Richards O C, Swiderek K M, Davis M T, Rusnak F, Harmon S A, Jia X Y, Summers D F, Ehrenfeld E. Hepatitis A virus capsid protein VP1 has a heterogeneous C terminus. J Virol. 1999;73:6015–6023. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6015-6023.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia X Y, Summers D F, Ehrenfeld E. Primary cleavage of the HAV capsid protein precursor in the middle of the proposed 2A coding region. Virology. 1993;193:515–519. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King A M. Preferred sites of recombination in poliovirus RNA: an analysis of 40 intertypic cross-over sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:11705–11723. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.24.11705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai M M C. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;56:61–79. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.61-79.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanford R E, Chavez D, Chisari F V, Sureau C. Lack of detection of negative-strand hepatitis C virus RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and other extrahepatic tissues by the highly strand-specific rTth reverse transcriptase PCR. J Virol. 1995;69:8079–8083. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8079-8083.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemon S M. Type A viral hepatitis. New developments in an old disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1059–1067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510243131706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemon S M, Binn L N, Marchwicki R H. Radioimmunofocus assay for quantitation of hepatitis A virus in cell cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:834–839. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.5.834-839.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemon S M, Honda M. Internal ribosome entry sites within the RNA genomes of hepatitis C virus and other flaviviruses. Semin Virol. 1997;8:274–288. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemon S M, Murphy P C, Shields P A, Ping L H, Feinstone S M, Cromeans T, Jansen R W. Antigenic and genetic variation in cytopathic hepatitis A virus variants arising during persistent infection: evidence for genetic recombination. J Virol. 1991;65:2056–2065. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.2056-2065.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu H H, Alexander L, Wimmer E. Construction and genetic analysis of dicistronic polioviruses containing open reading frames for epitopes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp 120. J Virol. 1995;69:4797–4806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4797-4806.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacGregor A, Kornitschuk M, Hurrell J G, Lehmann N I, Coulepis A G, Locarnini S A, Gust I D. Monoclonal antibodies against hepatitis A virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:1237–1243. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.5.1237-1243.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin A, Bénichou D, Chao S-F, Cohen L M, Lemon S M. Maturation of the hepatitis A virus capsid protein VP1 is not dependent on processing by the 3Cpro proteinase. J Virol. 1999;73:6220–6227. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6220-6227.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin A, Escriou N, Chao S F, Girard M, Lemon S M, Wychowski C. Identification and site-directed mutagenesis of the primary (2A/2B) cleavage site of the hepatitis A virus polyprotein: functional impact on the infectivity of HAV RNA transcripts. Virology. 1995;213:213–222. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKnight K L, Lemon S M. The rhinovirus type 14 genome contains an internally located RNA structure that is required for viral replication. RNA. 1998;4:1569–1584. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298981006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molla A, Jang S K, Paul A V, Reuer Q, Wimmer E. Cardioviral internal ribosomal entry site is functional in a genetically engineered dicistronic poliovirus. Nature. 1992;356:255–257. doi: 10.1038/356255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molla A, Paul A V, Schmid M, Jang S K, Wimmer E. Studies on dicistronic polioviruses implicate viral proteinase 2Apro in RNA replication. Virology. 1993;196:739–747. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Najarian R, Caput D, Gee W, Potter S J, Renard A, Merryweather J, Van Nest G, Dina D. Primary structure and gene organization of human hepatitis A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2627–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuesch J, Krech S, Siegl G. Detection and characterization of subgenomic RNAs in hepatitis A virus particles. Virology. 1988;165:419–427. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmenberg A C, Parks G D, Hall D J, Ingraham R H, Seng T W, Pallai P V. Proteolytic processing of the cardioviral P2 region: primary 2A/2B cleavage in clone-derived precursors. Virology. 1992;190:754–762. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90913-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parks G D, Duke G M, Palmenberg A C. Encephalomyocarditis virus 3C protease: efficient cell-free expression from clones which link viral 5′ noncoding sequences to the P3 region. J Virol. 1986;60:376–384. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.376-384.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pringle C R. Virus taxonomy at the XIth International Congress of Virology, Sydney, Australia, 1999. Arch Virol. 1999;144:2065–2070. doi: 10.1007/s007050050728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan M D, Flint M. Virus-encoded proteinases of the picornavirus super group. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:699–723. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-4-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan M D, King A M, Thomas G P. Cleavage of foot-and-mouth disease virus polyprotein is mediated by residues located within a 19 amino acid sequence. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2727–2732. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-11-2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schultheiss T, Kusov Y Y, Gauss-Müller V. Proteinase 3C of hepatitis A virus (HAV) cleaves the HAV polyprotein P2–P3 at all sites including VP1/2A and 2A/2B. Virology. 1994;198:275–281. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultheiss T, Sommergruber W, Kusov Y, Gauss-Muller V. Cleavage specificity of purified recombinant hepatitis A virus 3C proteinase on natural substrates. J Virol. 1995;69:1727–1733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1727-1733.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schultz D E, Honda M, Whetter L E, McKnight K L, Lemon S M. Mutations within the 5′ nontranslated RNA of cell culture-adapted hepatitis A virus which enhance cap-independent translation in cultured African green monkey kidney cells. J Virol. 1996;70:1041–1049. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1041-1049.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stemmer W P, Morris S K. Enzymatic inverse PCR: a restriction site independent, single-fragment method for high-efficiency, site-directed mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1992;13:214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang S, van Rij R, Silvera D, Andino R. Toward a poliovirus-based simian immunodeficiency virus vaccine: correlation between genetic stability and immunogenicity. J Virol. 1997;71:7841–7850. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7841-7850.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weitz M, Baroudy B M, Maloy W L, Ticehurst J R, Purcell R H. Detection of a genome-linked protein (VPg) of hepatitis A virus and its comparison with other picornaviral VPgs. J Virol. 1986;60:124–130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.124-130.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whetter L E, Day S P, Elroy-Stein O, Brown E A, Lemon S M. Low efficiency of the 5′ nontranslated region of hepatitis A virus RNA in directing cap-independent translation in permissive monkey kidney cells. J Virol. 1994;68:5253–5263. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5253-5263.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wimmer E, Hellen C U, Cao X. Genetics of poliovirus. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:353–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Chao S-F, Ping L-M, Grace K, Clarke B, Lemon S M. An infectious cDNA clone of a cytopathic hepatitis A virus: genomic regions associated with rapid replication and cytopathic effect. Virology. 1995;212:686–697. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Kaplan G G. Characterization of replication-competent hepatitis A virus constructs containing insertions at the N terminus of the polyprotein. J Virol. 1998;72:349–357. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.349-357.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]