ABSTRACT

Young adults increasingly rely on precarious and costly rental housing, particularly in major cities and liberalized housing markets. Amsterdam has a more regulated housing system, but increasing market-liberal logic in policy-making has led to considerable loosening of rent regulations in the last decade. One outcome has been the significant growth, and transformation, of liberalized rental housing. Drawing on city of Amsterdam survey data from 2005 to 2019, our analysis considers how recent policy and housing market shifts have generated and shaped housing inequalities for young adults. Where private rental growth was stimulated to fill the middle segment, our findings reveal that it has largely catered to affluent young adults. Households with less resources struggle to gain access, and pay more when they do. Our findings demonstrate that this variation of ‘generation rent” is not simply an outcome of market-liberal agendas, but is also shaped on a city-scale, partly through rental market restructuring.

KEYWORDS: Housing, young adults, inequality

Introduction

Over the last two decades, shifting economic and housing market conditions have resulted in greater shares of young adults dependent on precarious and costly rental housing arrangements, especially in major cities (Lennartz et al., 2016; McKee, 2012; Hoolachan et al., 2017). This development has been most conspicuous across economically liberal and Anglophone countries like Australia, the UK, Ireland and the US, where intergenerational and socio-economic divides in housing conditions and wealth accumulation practices have deepened (Byrne, 2020). Debates around contemporary restructuring in housing market opportunities have been dominated by these contexts. These debates have centered on diminishing homeownership rates among post-1980 birth cohorts, and the subsequent growth of private rental housing, reflecting a renter-owner binary.

Concerns around ‘generation rent’, however, do not only revolve around a shift from owner occupancy to renting, but also involve divergent outcomes and experiences amongst renters. Particularly, the restructuring of rental housing tenures and the fading of regulated rental alternatives play a central, though underacknowledged, role in shaping these experiences. We contend that examining market-liberal restructuring beyond liberal housing regimes brings this argument into sharper focus. Intergenerational divisions have become more pronounced, homeownership access restricted and rental experiences more precarious in a greater diversity of housing and welfare contexts, ranging from familial housing systems (e.g. Fuster et al., 2019) to more corporatist and social-democratic ones (Hochstenbach & Arundel, 2021; Grander, 2021; Christophers & O’Sullivan, 2019). In particular, larger cities like Amsterdam have not only seen sharp house price increases crowding out prospective first-time buyers, but also a declining availability of regulated rental alternatives. These trends are not only the result of high levels of demand and speculative investment, but also a political agenda focused on market-liberal housing reforms. This has led to the rapid expansion of the rent-liberalized housing sector in the city (Hochstenbach & Ronald, 2020), fundamentally recasting housing outcomes and experiences – especially for young adults. Amsterdam therefore represents a provocative case for studying the impact of housing transformations on young adults: it is historically a social rental city that has seen, or even promoted, a particular manifestation of ‘generation rent’.

This paper advances debates around housing transformations and young adults’ housing opportunities in three main ways. First, moving beyond a simple generational lens, this study unravels more precisely which populations are becoming more dependent on the growing rent-liberalized housing sector, highlighting disparities both between and within generations. In demonstrating the divergent experiences of young renters, which vary in character and intensity and come with different implications, it contributes to a growing body of scholarship which emphasizes the classed nature of housing inequalities amongst young people (e.g. McKee, 2012; Coulter et al., 2020; Christophers, 2019; Grander, 2021; Dewilde & Flynn, 2021).

Second, this paper brings together literature on intergenerational housing inequalities and the political economy of rental housing. More specifically, it highlights the subtle, yet important, distinction between a general decline in young-adult homeownership and an emergence of ‘generation rent’. We emphasize that the degree and type of regulation of rental housing, rather than the share of young adults who reside in the tenure, is a key driver of housing inequalities. The Amsterdam case shows that rental reforms are a major cause of young adults’ increasing dependency on expensive and insecure rental housing, exacerbating social divides not only between homeowners and renters, but also between types of renters.

Third, while most studies address housing market shifts at the national level (see Kadi & Lilius, 2022), this study highlights the salience of city-based analyses. Major cities are typically where competition for housing is strongest, demand is highest, and tenure restructuring most pronounced. Undertaking this analysis on the city scale shows how the rental sector has been reconfigured through national and local policies in both the long and the short term, and highlights the differentiated impacts of this reconfiguration across socio-economic groups (e.g. Watt, 2020; Grander, 2021).

This paper proceeds by examining the dynamics of post-war tenure transitions, the changing alignment of housing within wider economic and political processes, and how this has restructured housing opportunities over time. Transformations and emerging patterns in housing systems are considered across high-income economies, with reflection on how the Netherlands has lined up with international trends. Attention then moves to our empirical case, Amsterdam, and the major shifts in housing policies and tenure structure that have culminated in both the revival and transformation of the private rental sector and, in particular, the growth in the rent-liberalized segment. We draw on a large-scale survey undertaken biannually by the Amsterdam municipality for the 2005–2019 period.

Private rental regrowth

Despite previous, longstanding declines, private rental sectors have seen a remarkable resurgence in recent decades across countries. This shift has been spurred by declining access to social and regulated rental housing, the diminishing affordability of owner-occupation, regulatory shifts encouraging market-based housing provision, and socio-economic changes across labor markets and life courses (see e.g. Kemp, 2015; Hulse et al., 2012). It has been further argued that tenure realignments reflect a deeper repositioning of housing in the economy.

These transformations are part of a historical process wherein political hegemony and wealth accumulation processes in the late twentieth century became increasingly positioned around the financialization of mortgage debt, and the expansion of family-owned residential property (see Adkins et al., 2020; Forrest & Hirayama, 2015). This process provided the groundwork for a new wealth accumulation model in which housing asset ownership became more concentrated and rentierism, featuring various kinds of landlords, proliferated in the twenty-first century (see, Fields, 2018; Ronald & Kadi, 2018; Waldron, 2018; Wainwright, 2023; Hochstenbach & Aalbers, 2023). While a considerable housing financialization literature has emerged, our analysis focuses upon variegation in housing system restructuring – and private rental sector restructuring more specifically – and the implications for generational inequalities in housing markets and related urban outcomes. In this section we address historic relations between housing and the economy, the recent resurgence in private renting and its impact on young urban adults, and the salience of the Dutch case in these discussions.

Housing system restructuring

Private rental sectors declined in size across high income economies throughout the twentieth century, following the rise of post-war social housing programs and, later, the widespread growth of homeownership (Crook & Kemp, 2014). In this period, housing played a growing role in economic liberalization through the expansion of property ownership. Mass homeownership was assumed to economically integrate households, sustain social stability, encourage political conservatism and stimulate greater consumption (Forrest & Hirayama, 2015; Ronald, 2008). For Crouch (2009), state promotion of property ownership later began to rework the Keynesian post-war model by sustaining government efforts to shift economic responsibility from the state to the individual. With the dynamics of economic growth increasingly driven by the expansion of bank lending for home buying, demand for housing (and thus prices) grew even further. This generated greater household equity and even more demand. Increases in individual housing equity ostensibly made households more economically self-reliant and, Crouch argues, allowed for welfare state retrenchment and writing down public debt. Private renting thus became an anachronism and gave way to waves of younger buyers, expected to accumulate wealth through housing market moves.

In the early-2000s, however, the decline of private renting began to reverse across many societies. State subsidies, loose mortgage credit, low interest rates and increasing speculative investment saw flows of capital into an inelastic housing stock intensify. This drove up prices, and rendered homeownership inaccessible for many (Arundel & Ronald, 2021; Ryan-Collins et al., 2017; Aalbers et al., 2021). The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) initially undermined house prices, although potential buyers, especially younger ones, were unable to capitalize on the moment due to increasingly stringent access to credit. Economic and labor market destabilization also exacerbated conditions for first-time buyers, with younger households across high income economies increasingly relying on the private rental sector (Lennartz et al., 2016).

Rental housing as an investment asset

For Forrest and Hirayama (2015), this era represents a transition to a more “neoliberal project” in housing market restructuring. Rather than simply encouraging homeownership, regulatory corrections became largely concerned with the capacity of the housing sector to indiscriminately generate profits and stimulate growth. Capital became increasingly aligned around global real estate, with growing supplies of post-GFC distressed assets and foreclosed homes attracting different kinds of investors (Beswick et al., 2016; Fields, 2018). Prices not only recovered but boomed after 2014 in most contexts, dampening homeownership possibilities further and increasing pressure on renting and rents (and thereby generating greater profits). This saw growing flows of capital into private rental housing from large and small scale investor landlords (Ronald & Kadi, 2018; Wijburg et al., 2018), who capitalized on both buy-to-let (Paccoud, 2017; Hochstenbach, 2022) and build-to-rent (Nethercote, 2020; Brill & Durrant, 2021; Goulding et al., 2023) opportunities. Thus, while the pre-crisis period was marked by a profound commodification of owner-occupied housing and a “debt-driven model of financialization”, the post-crisis period is marked by a sharp increase in demand for private rental investment opportunities and a “wealth-driven model of financialization”. This targets private rental housing subsectors – characteristically occupied by younger adults excluded from both social housing and owner-occupation – as new asset classes (Aalbers et al., 2021).

There is considerable diversity among contemporary investor landlords at both global and local scales, with some pursuing aggressive short-term strategies by buying up existing stock and others focusing on stable medium to long term revenues and investment in new build-to-rent supply (see August, 2020; Brill et al., 2022; Christophers, 2022; Fernandez et al., 2022; Nethercote, 2020). Housing transformations in the Netherlands in many ways comply with global shifts in the political economy of housing financialization, although exact details and timing vary considerably. In many countries, private rental growth has been spurred by direct policies but also indirectly, through diminishing the rights of tenants. Also in the Netherlands, a country with traditionally strong tenant protection, policy reforms have strengthened landlord power through reducing rent controls and diminishing security of tenure, especially since 2016 (see Huisman & Mulder, 2022). Policy revisions have been legitimized by narratives suggesting reforms will improve housing opportunities for those unable to buy privately, or rent in the social sector.

Socioeconomic changes and ‘generation rent’

In context of these dramatic shifts in global housing conditions, new landscapes of intergenerational inequality have emerged, especially in urban contexts. Stagnating wages, increased labor mobility, and precarious, part time or temporary work contracts have posed an increasing barrier to homeownership, particularly for young and less affluent households (see Hoolachan et al., 2017; Coulter et al., 2020; Arundel & Lennartz, 2020). Furthermore, young adults with fewer assets at their disposal and more limited access to mortgage credit than their predecessors, and have found themselves increasingly outbid by existing owners, investors and buy-to-let landlords (Forrest & Hirayama, 2015).

Whilst economic exclusion is a critical factor, shifting life-course trends are also linked to the growth in private renting amongst younger groups. The transitional phase preceding normative markers of “adulthood” has extended for many, as young people stay in education longer, couple, marry and have children later, work and travel more, and stay in insecure or temporary employment for extended periods (e.g. Flynn, 2017). While the desire for flexibility may increase preferences for private rental housing amongst some young adults, for many the decision to rent is more contingent on extended periods of instability and incapability of meeting mortgage requirements. This extended transitory life period also has spatial dimensions, often playing out in major urban centers and university cities (Buzar et al., 2005), generating extra demand for urban living, but specifically for urban private rental housing. This has also boosted the commodification and commercialization of shared and serviced forms of housing for typically highly educated and mobile young adults, further enabling rent extraction (Maalsen, 2020; Uyttebrouck et al., 2020; Ronald et al., 2023; White, 2023).

There are thus important links between emerging housing market trends, urban conditions, and the shifting political economy of housing, especially for younger cohorts. Indeed, transformations from debt-driven to wealth-driven forms of financialization as set out by Aalbers and colleagues (2021), and the increasing concentrations of housing property associated with “late-” or “post-homeownership” conditions (Forrest & Hirayama, 2015; Ronald, 2008), have driven a clear shift to private renting that is disproportionately impacting younger adults, especially in cities. The promotion of private renting has opened various, specific avenues to incorporate private rental housing into profit-making, or accumulation trajectories, ranging from tenurial conversions within the existing stock, new constructions and the commodification of other forms of living.

While focus on these inequalities has prompted a proliferation of international research, scholars have argued that this body of work has tended to treat ‘generation rent’ as “an undifferentiated mass” (McKee et al., 2020, p. 1469). Indeed, there are various gaps and poorly made differentiations that reflect the emergent nature of this literature. First has been a tendency to either not differentiate by income, or to focus only on the poorest and most precarious of young people due to the most obvious effects on shifting housing conditions on this group. There has thus been limited reflection on the diversity of outcomes by income groups, household types, genders, and ethnicities (Watt, 2020). Secondly, there has been an implicit “renting or owning” binary (McKee et al., 2017), resulting in a neglect of diversity within and across these tenures, both nationally and internationally. Certainly, the literature is orientated, with some exceptions (e.g. Christophers, 2019; Grander, 2021; Fuster et al., 2019), toward empirical cases drawn from Anglophone contexts and more economically liberal, dualist housing systems featuring common and relatively comparable tenure rights and structures. Thirdly, and critically, there has been little recognition of geography and variegation in analyses of generation rent. This applies not only to differences between countries and regions (however see Coulter, 2017; Hochstenbach & Arundel, 2021), but also differences in spatial configurations, urban issues, local governance and political alliances. Furthermore, while the dispersal of generation rent is wide, concentrations are potentially more intense and outcomes more extreme in larger cities, especially ones closely tied to global financial networks. These three shortcomings are variously addressed in our empirical analysis of Amsterdam, as follows.

The case: Amsterdam’s housing market

Scholarly debates about intergenerational inequalities in the housing market center around diminished access to homeownership, and how this has created a generation reliant on, and largely exploited by, the private rental sector. Whilst these are undoubtedly related, we argue that decreased access to owner occupancy does not implicitly result in more expensive and insecure private rental housing. Mediating this relationship is a third important factor: the structure of the rental system. Rental markets have been actively transformed by market-liberal agendas, urban politics and the restructuring of global capital around rental real estate, especially in the years since the GFC. We thus turn our focus now to rental housing restructuring in Amsterdam.

Rental housing in Amsterdam, as in the Netherlands overall, is bifurcated into a regulated and liberalized sector (Table 1). In the former, rents are calculated based on a universal point system. Maximum rent has traditionally been calculated on square meterage and standard of amenities, irrespective of whether a property was rented by a not-for-profit housing association or private landlord. Cost was dependent on market property value or location, with rent increases, allocation procedures and contract conditions determined by state guidelines. In the mid-nineties, around 85% of Amsterdam’s rental housing was still rent regulated, with not-for-profit housing associations owning almost 60% of the total stock (Boterman & Van Gent, 2014).

Table 1.

Summary of rental housing in Amsterdam, 2019.

| Ownership | Costs | Allocation | Duration of contract | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rent regulated | Not-for-profit housing associations (38%) and private landlords (13%) | Upper threshold €720 in 2019, subject to annual change | Landlord but within state requirements | Permanent (exceptions e.g. youth contract) |

| Rent liberalized | Not-for-profit housing associations (3%) and private landlords (15%) | Determined by landlord | Determined by landlord | Permanent and temporary (permitted since 2016) |

Note: Figures are based on WiA data, and refer to share of total stock.

During the late 1990s and 2000s, these shares started to decrease due to tenure conversions from regulated rent into owner occupancy. During the 2010s, changes to the rent system made it easier for landlords to shift units from the regulated to the liberalized sector. Particularly important was the 2015 decision to include assessed real-estate values in the point system. Prior to these policy shifts, “converting” property from the regulated rental to the liberalized rental sector typically required expansions or improvements. Since this policy change, however, the vast majority of properties in high price locations (including large parts of Amsterdam) score enough points to be liberalized when the sitting tenant moves out. In 2003, only around 1% of housing-association units and 18% of private rental units in Amsterdam were liberalized. In 2019, this had increased to 8% and 54%, respectively (Hochstenbach & Ronald, 2020).

This change formed part of a broader ambition by local and national governments to reduce the share of social housing. From the mid-1990s, the national government discontinued direct support for housing associations, encouraging them to operate more like market players (Van Kempen & Priemus, 2002). Changes since this point, such as the annual “landlord levy” (verhuurderheffing) introduced in 2013 only to be paid over social rental units, has further curtailed housing associations’ investment capacity. Decreases in social housing supply were paired with regulatory shifts which sought to further limit demand. In 2011, a gross household annual income threshold was introduced for the large majority of social housing stock, which in 2019 stood at 38,035 euros for 80% of social stock. This measure has driven social rental residualization (Van Gent & Hochstenbach, 2020; Van Duijne & Ronald, 2018). While these income limits restrict access, increasingly scarce supply drives waiting lists: in 2007, average social rental waiting times in Amsterdam stood at six years for starter households and fourteen years for tenants moving within the system. These have since increased to ten and eighteen years respectively (AFWC, 2022). This makes the tenure essentially unfeasible for young households and newcomers without priority access.

The tightening of mortgage lending criteria and rising house prices are particularly intense in Amsterdam, with inflation-corrected sales prices increasing from an average of 170,000 euros in 1996 to over 510,000 euros by 2020 (calculations based on CBS, 2023). While beyond the empirical scope of this paper, house prices continued to increase up until 2022 before dipping again following economic downturn, increasing interest rates and geopolitical turmoil. Policymakers and politicians, initially at the local level and later nationally as well, became concerned about population groups falling between owner occupancy and regulated rental housing (Hochstenbach & Ronald, 2020). These included middle income households earning either too little to access regulated rent and too much to buy, young adults, and flexible populations such as temporary (knowledge) workers and newcomers to the city looking for easily accessible housing. Like elsewhere, Dutch policy shifted focus onto expanding the rent-liberalized sector to fill this gap.

The growth of the rent-liberalized sector

As regulation has been liberalized, Amsterdam’s rental market has become increasingly profitable and, like more liberalized contexts, has attracted investment from affluent individuals, institutions, and firms. Most notably, this follows changes to the points system, discussed above, and the introduction of temporary contracts. Where permanent contracts used to be the norm, since the 2016 housing act the national government has permitted one or two-year contracts in the rent-liberalized sector, increasing investment appeal in rental housing (Huisman & Mulder, 2022). With increased profitability and capacity for tenant turnover, buy-to-let purchases have rapidly increased from 16% of all home purchases in 2009, to 28% in 2019. This is significantly higher than the national levels, which increased from 10% to 15% over the same period (Hochstenbach & Aalbers, 2023). Large institutional investors have similarly found their way to Amsterdam, with major foreign players like Blackstone buying up portfolios of existing housing in the city – a trend actively encouraged by national government (Fernandez et al., 2022; Taşan-Kok et al., 2021).

Amsterdam city government has also sought to increase the share of rent-liberalized housing in new developments. While national government largely determines regulations around existing housing (e.g. regarding maximum rents, income requirements and mortgage regulations), local states can exert a strong influence on new developments. The municipality of Amsterdam, furthermore, owns the majority of city land, meaning it has considerable control over what housing gets built. Before the GFC, standard policy for larger projects was to include 70% owner occupation and 30% social rent, with liberalized rental housing seldom considered. Yet, coming out of the GFC and following a slump in housing production, the city government increased the share of rent-liberalized units in new production. By 2019, around half of all new-built dwellings were liberalized rental units. Since 2017, formal policy ambitions are that 40% of all new constructions should be affordable, 40% middle-segment and 20% expensive. In practice, the first category consists of social rental housing while the latter two consist of both rent-liberalized and owner-occupied units. In other contexts, private rental growth has mostly come at the expense of owner-occupation. In Amsterdam, however, this is less evident as the volume of owner-occupied units has substantially grown over the last two decades, and only recently stagnated.

The shift towards private and liberalized rental housing can thus be considered a state-led restructuring accommodated by local and national policy. It set in motion a notable growth of these rental tenures with the aim to house specific populations excluded from the other dominant tenures such as young adults, flexible newcomers, and middle-income households. The key question, then, is which populations the rapidly growing rent-liberalized sector actually caters to. Is it to the young middle-income earners squeezed out of other tenures, or other groups?

Data and variables

Data

In our analysis, we draw on “Living in Amsterdam” (Wonen in Amsterdam, or WiA) survey data, a biannual household survey carried out by the housing department and statistics department of the Amsterdam municipality. Our geographic focus is the municipal area of the city Amsterdam (863,000 residents in 2019), whose administrative boundaries have remained stable over the study period 2005–2019. Each survey wave has around 18,000 respondents and is supplemented by additional housing and population register data. The survey provides additional weights to correct for over and underrepresentation, and make the sample representative for the Amsterdam household population (see supplementary material 1). The survey is cross-sectional in design, meaning it is not possible to follow respondents over time. A crucial advantage of these survey data sets over full-population register data is that they contain detailed information on rent levels and rental contract type. We report 95% confidence intervals in supplementary material 3 and 4, and use data from the 2005–2019 survey waves, as older waves are not as directly comparable. More substantively, it was only after 2005 that the revival and liberalization of private renting set in motion. At the time of conducting the research, 2019 is the most recent wave.

Variables

We are primarily interested in the (changing) distribution of households across housing tenures. As explained above, the Dutch housing stock can be divided into ownership categories: owner occupied; housing association; and private landlord. Rental units can further be classified as rent-regulated or rent-liberalized (Table 1), with monthly rents respectively below or above the 720 euro mark in 2019. There are then five main tenures: (1) owner occupied; (2) regulated housing-association rent; (3) regulated private rent; (4) liberalized housing-association rent; and (5) liberalized private rent. For the sake of simplicity, in this paper we follow a threefold categorization of owner occupation, regulated rent and liberalized rent. Another substantive argument is that the liberalized segment serves the same purpose, regardless of ownership. A more practical argument is that the liberalized stock in housing association ownership went from virtually non-existent to rather small, making reliable analyses with survey data difficult. Households with missing tenure information (2.1% in 2019) are excluded from all analyses.

We also consider housing contract type. Although most tenants have a permanent rental contract, we can also distinguish several types of temporary contracts: (1) campus contracts for students which expire six months after deregistering from university; (2) five-year youth contracts where the tenant has to be 18–27 upon signing the contract; and (3) one- or two-year rental contracts introduced in 2016. In our data, these are all similarly categorized as a form of temporary contract.

We define four age categories (based on household respondents): 25–34, 35–44; 45–64 and 65–74. Adults aged 18–24 or 75 + are not analyzed as a separate category but included in totals. Our focus is on the 25–34 year old cohort, which can broadly be described as young adults typically not dependent on student housing (as is the case among 18–24 year olds). Cole et al. (2016, p. 1) describe 25–34-year-olds as “a critical cohort in terms of new household formation and tenure change” whilst also pointing out that “this is where some of the recent structural changes […] are most evident”.

We define three income groups: low, middle and high. We use gross household income as this determines eligibility for social rent and, by implication, liberalized rent. Low-income households earn a gross household income below the social rental threshold of 38,035 euros in 2019. Households earning more are, notwithstanding exceptions, ineligible for social rent. High-income households have a gross annual income of at least 76,070 euros – double the social rental threshold and roughly corresponding to twice the “modal” Dutch income. For all years, we correct incomes to 2019 levels to enable comparison. We use stable categories rather than percentiles to acknowledge that the income distribution of households has become higher, enabling us to capture whether Amsterdam has become less accessible for low-income residents overall. Using stable categories also means we measure the income of younger and older cohorts against the same measure as opposed to in relation to their respective age group. This makes the affluence of high-income young adults particularly notable. Non-response for income is higher than other variables (28% in 2019), for which the provided weights correct.

We further distinguish newcomers as those who have moved within the last 2.5 years, a benchmark selected due to availability of data. We also consider variables such as respondents’ sex, household composition, education level and migration background. We follow the official Dutch classification where a person is considered to have a migration background when they themselves (first-generation) or one of their parents (second-generation) were born abroad. We further distinguish between Western and non-Western backgrounds, which rather than denoting geographical location refers to the socio-economic status of the origin country. Although this categorization has rightly been criticized, it enables us to capture whether migrants from richer countries have been overrepresented in rent liberalized housing.

Following our demand-side empirical approach and our data structure, our analyses are household rather than housing based. To give an example, we chart the share of high-income households living in the rent-liberalized sector rather than the share of rent-liberalized tenants having a high income. We subsequently chart changing distributions across tenures over time.

Analysis and findings

Changing class composition

Over the period studied, Amsterdam’s population went through notable changes. The number of households increased by 20% between 2007 and 2019 (Table 2), although this growth was highly uneven. The city became less accessible to both low and middle-income households, whose overall shares decreased by 8 and 2 percentage points respectively. The share of high-income households increased from 17% to 28%, paired with an associated suburbanization of lower income groups (Hochstenbach & Musterd, 2018). This trend was even more pronounced among young adults. In 2007, low-income households still formed a majority among young adults in the city (53%), but by 2019 high-income households were the largest group (40%). The 19 percentage point decrease in the share of low-income young adults in Amsterdam between 2007 and 2019 (compared to the 21 percentage point increase in high-income ones over the same timeframe) indicates that the exclusion of low-income persons in the younger age cohort in Amsterdam has not only been far more prolific than in other age cohorts, but also has far exceeded national averages where this classed dimension is much less apparent (see supplementary material 2). These overall shifts frame our subsequent analyses, where we unravel tenure distributions across socio-economic and demographic groups.

Table 2.

Amsterdam household composition by tenure. age. income. education and composition in 2007, 2013 and 2019, %. 95% confidence intervals reported in supplementary material 3.

| Year | % Point Change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2013 | 2019 | 2007–19 | |

| Regulated rent | 69.2 | 58.3 | 51.1 | −18.2 |

| Liberalized rent | 5.2 | 8.7 | 16.6 | 11.4 |

| Owner occupied | 25.6 | 33.0 | 32.4 | 6.8 |

| 18–24 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 0.7 |

| 25–34 | 19.2 | 20.1 | 21.9 | 2.7 |

| 35–44 | 22.6 | 19.4 | 17.9 | −4.7 |

| 45–54 | 19.7 | 19.9 | 16.7 | −3.0 |

| 55–64 | 15.3 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 3.2 |

| 65–74 | 9.5 | 11.6 | 13.1 | 3.6 |

| 75+ | 9.4 | 7.0 | 6.8 | −2.6 |

| Low income | 55.9 | 55.6 | 47.5 | −8.4 |

| Middle income | 26.7 | 25.2 | 24.4 | −2.2 |

| High income | 17.5 | 19.2 | 28.1 | 10.6 |

| Low education | 36.5 | 30.0 | 22.6 | −13.9 |

| Mid education | 31.3 | 34.0 | 32.9 | 1.6 |

| High education | 32.2 | 36.0 | 44.5 | 12.3 |

| Single person | 47.6 | 46.3 | 49.1 | 1.5 |

| Couple no children | 23.5 | 22.3 | 22.7 | −0.9 |

| Single parent | 9.3 | 9.0 | 7.2 | −2.1 |

| Couple with children | 18.3 | 19.6 | 19.2 | 0.8 |

| Other | 1.3 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| Low income (25-34 y/o) | 53.3 | 45.0 | 34.3 | −19.0 |

| Middle income (25-34 y/o) | 28.3 | 29.6 | 25.9 | −2.4 |

| High income (25-34 y/o) | 18.4 | 25.3 | 39.8 | 21.4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.0 |

| N households (*1000) | 367 | 391 | 441 | 75 |

| N 25–34 y/o (*1000) | 70 | 78 | 97 | 26 |

Note: percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. Weighted and unweighted sample size reported in supplementary material 1.

Age and tenure dynamics

Considering tenure distribution (Figure 1), regulated rental housing still represents the majority tenure in Amsterdam in the overall population, housing 51% of households in 2019, although it has seen a substantial decline since 2005 when it accounted for 72% of households. Owner occupancy accounted for 31% households in 2019, up 10 percentage points from 2005, although growth was concentrated leading up to 2013 and has stagnated since. Liberalized rental housing accounted for a mere 4% of households in 2005, but increased to 16% in 2019, with the rate of growth increasing over time.

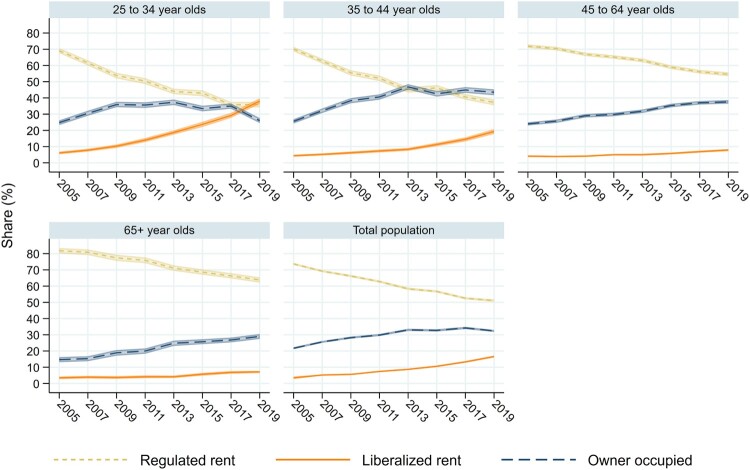

Figure 1.

Tenure distribution by age groups 2005–2019 (with 95% confidence intervals).

Tenure trends differ substantially across age groups (Figure 1). The share of households aged 45–64 and 65–74 in homeownership has gradually increased over time, whilst the share in rent-regulated housing has declined. For these groups, liberalized rental growth has seen a very marginal increase, but at around 8% has remained stable and low. Among 35–44 year olds, homeownership has been the dominant tenure since 2017, mostly due to a steep drop in regulated rental tenancies. However, while homeownership growth has also broadly stagnated among this age group, the share renting in the liberalized sector has rapidly increased, from 8% in 2013 to 19% in 2019.

Shifts are most pronounced amongst young adults (25–34), for whom rent-liberalized housing went from a small minority tenure, housing 5% of young adults in 2005 and 19% in 2013, to the largest tenure in 2019, housing 38%. Conversely, regulated rent has been in structural and steep decline among young adults over the study period, falling from 60% in 2007 to 30% in 2019. Importantly, this decline is substantially more than the decline of 25–34 year olds in homeownership, which reduced from 30% in 2007 to 25% in 2019. The main takeaway is that broad housing reforms have made younger adults in particular more dependent on expensive rental housing. While this also comes at the expense of young adults able to buy their home – as the literature on ‘generation rent’ emphasizes – it has particularly replaced young adults renting in the regulated segment.

We can further stratify our analyses by looking at households by income group (Figure 2). While Amsterdam has become less accessible for low-income households overall, 79% of those that do reside in the city live in regulated rental housing, down from 89% in 2005. Around 7% of low-income households live in liberalized rental housing despite the high rents, up from 2% in 2005. One in three high-income households now live in the rent-liberalized segment, as do one-in-four middle-income households. In 2005 this stood at 14% and 9%, respectively.

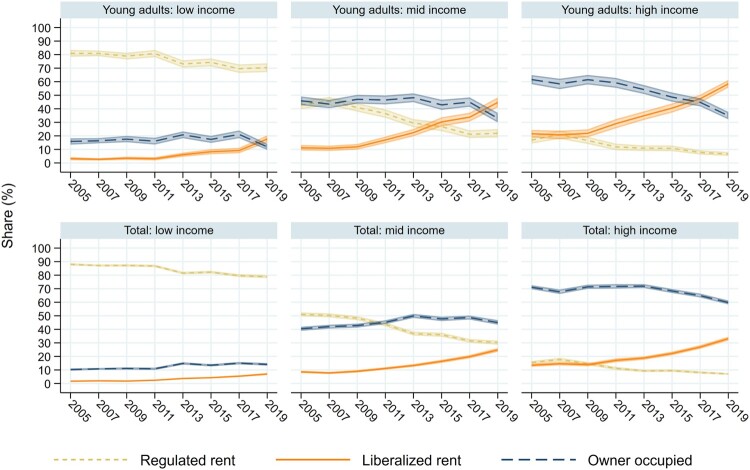

Figure 2.

Tenure distribution by income groups 2005–2019 among young adults (with 95% confidence intervals) compared to tenure distribution by income groups 2005–2019 among the overall study population.

Looking at 25–34 year olds specifically (Figure 2), almost 60% of young adults with a high income in 2019 rented in the liberalized segment, while this stood at around 20% up until the GFC. Conversely, the owner-occupancy rate dropped from over 60% to around 35%, suggesting a clear trade off. Middle-income young adults witnessed a similar though less pronounced shift, with 40% renting in the liberalized sector in 2019 compared to 14% pre-GFC. This went mostly at the expense of regulated renting (from 43% in 2005 to 22% in 2019) and more recently also owner occupancy (from 45 in 2005 to 33% in 2019). Among low-income households, an increase toward liberalized renting can also be identified, though it remains a relatively small tenure, housing around 18% in 2019. Overall, the growth of the liberalized rental sector has particularly catered to higher-income young adults at the expense of homeownership, while doing less to accommodate low and even middle-income groups.

What do these data tell us? Housing reforms – nationally and locally – have rendered middle-income and high-income young adults increasingly dependent on the liberalized rental segment. The institutional push to create a substantial rent-liberalized segment has thus particularly catered to more affluent households. Both middle- and high-income groups are increasingly failing to enter owner occupancy, with stricter mortgage lending criteria particularly excluding middle-income young adults. This group have also been barred from entering social rental housing through extended waiting lists and national level policies introducing strict maximum income criteria.

The majority of low-income young adults continue to live in regulated rental housing, though certainly less than before. This does not mean they are left untouched by the political promotion of liberalized rental housing. Instead, as Table 2 shows, low-income young adults are increasingly excluded from Amsterdam. These figures suggest young adults are excluded from moving to Amsterdam in the first place, while those having grown up in the city are increasingly unable to leave the parental home, representing another form of exclusion.

Where scholarship has pointed towards “youthification”, described by Moos (2016, p. 2904) as “young people across the income spectrum are found in urban spaces- some are gentrifiers, some are renters with more modest means”, our findings have highlighted an important class dimension to the overall increase in young urban dwellers. This is the differentiated effect of recent national and urban housing politics in the Netherlands: while more affluent young adults resort to more expensive private rental housing, their low-income peers are shut out.

Changing conditions of the rent liberalized sector

Young adults are not only increasingly faced with high rents in the liberalized segment, but also confronted with housing precarity – a novelty in the Dutch context where tenant protection has previously been strong. Since temporary contracts are a relatively new phenomenon in the Netherlands, suitable quantitative data are scarce (however, see Huisman & Mulder, 2022). Our survey data suggest that in 2013 around 3–4% of the total Amsterdam population rented on a temporary basis (previous waves of the Living in Amsterdam survey didn’t register temporary tenancies), which, by 2019, had increased to around 7%. This suggests a doubling in scale. Among young adults, this share increased from 6–7% in 2013 to 16–18% in 2019. This increase was particularly notable post-2017, after the large-scale introduction of temporary tenancies. Around one in six young adults living in Amsterdam in 2019 were thus dependent on precarious rental contracts, a substantial change in an urban and national context previously known for its strong tenant protection. Investigative journalism has suggested that by 2020 temporary contracts were the dominant contract form among private landlords for new lettings across the Netherlands (Salomons & Voogt, 2020).

Rent-liberalized housing across demographic groups

The increase in rent-liberalized housing in Amsterdam has particularly catered to higher-income households and young adults, as shown. It remains an open question, however, to what extent the tenure caters to specific groups, or whether it has increased across the board. We now turn to how other household characteristics are represented in the liberalized section, looking at all households as well as young adults specifically.

Figure 3 reveals unevenness in the profiles of households residing in the liberalized rental tenure between 2007 and 2019. Apart from particularly steep increases among the affluent and the young (Figures 1 and 2), strong increases can be found among highly educated residents, and those with a Western migration background. These are likely temporary knowledge workers seeking flexible accommodation, and outsiders who lack the networks to access regulated housing. Interestingly, while the liberalized sector is often presented as a housing solution for (young) single-person households, our data shows that couples without children are overrepresented in the tenure (30% in 2019), and even families with children reside in the tenure more often than singles. An explanation is that high rents are particularly insurmountable for those on a single income. As expected, recent movers are also overrepresented in the liberalized sector, with one in three recent movers (i.e. those that moved the past 2.5 years to, or within, Amsterdam) living in the tenure in 2019. This is a necessary consequence of recent growth, further reinforced by the advance of temporary contracts, displacing tenants and enforcing churn.

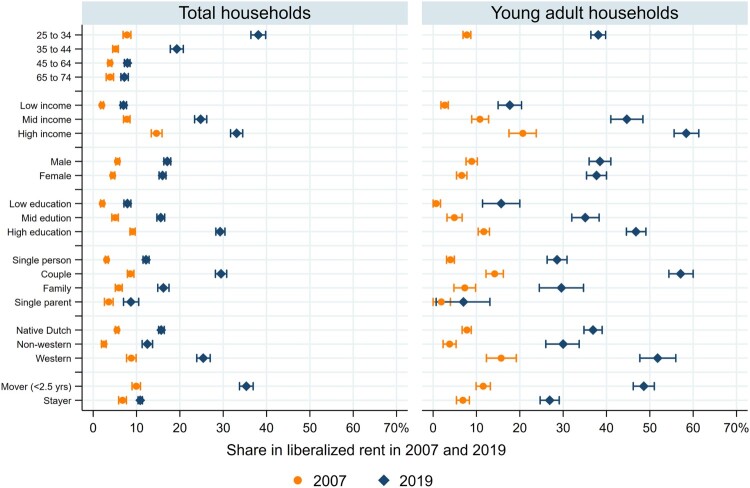

Figure 3.

Share of total households and young adult households living in liberalized rental housing by different characteristics in 2007 and 2019 (with 95% confidence intervals).

In sum, more than half of all young couples, high-income households, and those with a western migration background were living in rent-liberalized housing in 2019. Interestingly, while roughly half of all recently moved young adults live in liberalized housing, almost 30% of young adults that haven’t moved in the past 2.5 years live in liberalized housing. These patterns suggest that the tenure has become more than a transitory tenure for many young adults, but for some a longer-term place of residence.

Housing affordability stress and changes to size and costs of housing

So far, our analyses have shown that tenure restructuring has broadly increased dependency on liberalized rental housing, accommodating higher income groups while excluding lower income populations. Now we turn to affordability implications for those living in the tenure (Table 3).

Table 3.

Housing affordability indicators 2007–2019 among renters in the liberalized sector. 95% confidence intervals reported in supplementary material 4.

| Year | Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2019 | % | % Point | ||

| Total | Size (m²) | 76.5 | 65.7 | −14 | |

| Rent (€) | 988 | 1204 | 22 | ||

| Rent per m² (€) | 14.1 | 20.2 | 43 | ||

| Rent quote (%) | 29.3 | 33.2 | 4 | ||

| Affordability stress (%) | 18.6 | 23.2 | 5 | ||

| Young adults | Size (m²) | 66.3 | 58.8 | −11 | |

| Rent (€) | 1012 | 1235 | 22 | ||

| Rent per m² (€) | 16.7 | 22.9 | 37 | ||

| Rent quote (%) | 29.3 | 32.4 | 3 | ||

| Affordability stress (%) | 19.3 | 20.0 | 1 | ||

| Recent movers | Size (m²) | 72.3 | 60.8 | −16 | |

| Rent (€) | 1051 | 1337 | 27 | ||

| Rent per m² (€) | 16.2 | 24.0 | 48 | ||

| Rent quote (%) | 31.1 | 34.3 | 3 | ||

| Affordability stress (%) | 23.7 | 24.6 | 1 | ||

Notes: basic rents (without utilities) reported; rent quotes are basic rents as a percentage of net household income; affordability stress refers to households spending 40% or more of their income on basic rent.

Between 2007 and 2019 average inflation-corrected rents in the private rental tenure rose by 22%, from €988 to €1204 per month. At the same time, apartments in the tenure have become smaller, decreasing by an average of 14% over the period studied, from 77 to 66 m². This is largely explained by buy-to-let purchases concentrating in the smaller housing segment, and new constructions typically being relatively small (Aalbers et al., 2021). Consequently, mean rents per square meter increased by 43% between 2007 and 2009, from around €14 to €20. Renters spend an increasing share of their income on rent, from 29% of net household incomes in 2007, to 33% in 2019. Very similar trends apply when zooming in on young adults and recent movers. While it is possible, even likely, that the quality of accommodation has increased with the increasingly professional landlord class, renters in the tenure are spending more of their income on rent while getting less in return – at least in terms of size.

While rent costs and rent quotes (as a share of household income) have clearly increased (Table 3), the share of households experiencing housing affordability stress have not significantly gone up. In 2019, around 23% of households in the rent-liberalized sector spent more than 40% of their income on rent (noting that this definition, as referred to in Table 3 as “affordability stress’, is generous compared to a common threshold of 30%). This stood at 19% in 2007. Some exceptions exist, with clear and significant increases in housing affordability stress among middle-income households (from 11% to 18%), single-person households (from 30% to 40%) and families with children (from 5% to 15%) over this time period. Overall and for most subpopulations, though, rates of housing affordability stress, have not significantly trended upwards despite increasing costs. A tentative explanation is that the tenure is increasingly geared towards higher earning and dual earner households (still) able to afford the higher rents.

In short, rent quotes and associated housing affordability stress have increased across the tenure, albeit unevenly. While the rent-liberalized tenure largely excludes lower-income populations, it requires increasingly stark trade-offs from those that do manage to access the tenure.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper set out to extend understanding of transformations in housing tenure structures and emerging patterns of housing inequality evident across high income economies in recent decades. It specifically considered how the realignment of housing in the economy, in an even more financialized post-crisis era, has shaped intergeneration inequalities in urban housing conditions. The focus on the Netherlands, and Amsterdam in particular, sought not only to extend the empirical range of research, but also draw attention to diversification in regulatory practices and rental housing tenures. Indeed, while the dynamics of ‘generation rent’ are clearly at work in Amsterdam, the ways in which the urban housing system is being liberalized are playing a critical role in shaping outcomes. In analyzing the changing profiles of rental households in Amsterdam from 2005 to 2019, this study has considered the combined results of tenure restructuring, population trends, and increasing rental market pressures. Our analysis focused on outcomes for different cohorts, centering on young adults and looking at a range of socio-economic and demographic characteristics. In doing so, we sought to link institutional changes and housing reforms with their residential outcomes. From these findings we can draw three main conclusions.

First, all household types have become more dependent on liberalized rental housing, as a growing number of people have fallen between the gap of regulated rental housing and homeownership. However, high-income households have driven the most growth, and now represent the largest group in this sector. With high demand from affluent groups and rapidly increasing rents, many low- and middle-income households, particularly those on a single income, are unable to access the rapidly growing rent liberalized sector. While policy ambitions formally set out to expand the liberalized rental sector to house middle-income groups squeezed from other tenures, our results demonstrate the tenure has primarily accommodated affluent households. This demonstrates the divergent experiences of young renters, which, as other scholars have emphasized (e.g. McKee, 2012; Coulter et al., 2020; Christophers, 2019; Grander, 2021), vary in character and intensity, and have different implications across socio-economic groups.

To this end, we argue that the growth of the rent liberalized sector has been an important driver of urban population restructuring, accelerating the share of affluent households in the city at the expense of middle- and lower-income households. Although some low- and middle-income households can still access regulated housing, more are being excluded from the city or, if staying in Amsterdam, likely restricted to co-residence in the parental home. We therefore argue that the shift towards rent-liberalized housing is not only a response to households falling between other tenures, but also represents a refocusing of Amsterdam municipalities’ middle-class agenda. Attracting more affluent households and accommodating greater urban growth was previously stimulated through homeownership in Amsterdam (Van Gent, 2013). However, particularly since the GFC, urban growth driven by expanding homeownership has run out of steam as the tenure is now beyond the reach of most young adults, even the high-income or upwardly mobile amongst them. It has therefore been supplemented by expansion of the high-price rental sector.

The shift from owner-occupation to private rent – both at the individual level and in housing provision more broadly – represents a continuation of housing-based accumulation. At the local level, this process is captured by the geographically contingent concept of the value gap, close kin to the rent gap central to gentrification theory. While initially formulated to explain landlord disinvestments and conversions from private rent into owner-occupancy (Hamnett & Randolph, 1984), the concept also describes private rental arrangements generating greater accumulation prospects than owner-occupancy, triggering tenurial conversions from the latter to the former, i.e., buy-to-let (Paccoud, 2017). The shifting housing landscape, marked by politics promoting private rental growth and liberalization, at the micro-level takes shape in the form of value gaps which private investors can capitalize on through buy-to-let strategies. While rent and value gap concepts are rooted in supply-side analyses of urban transformations, our findings underscore how they crucially depend on residential demand from populations, specifically young adults that would previously have followed residential trajectories into owner-occupancy or stable social rental housing. Housing politics have not only boosted private rental growth and liberalization directly, but also indirectly, by closing off these other trajectories, namely restricting homeownership access and dismantling social rental alternatives.

Second, our case clearly demonstrates the state orchestrated growth of the private rental sector in a country which has historically retained a large degree of control over the market. We show how both national and local government have played an active role in expanding and shaping liberalized rental housing in Amsterdam to accommodate (or at least lay claim to accommodate) households falling between regulated rental housing and homeownership. National policies have restricted regulated rental access to the poorest households, while pro-homeownership policies have fueled price increases (along with the cross-national trend of increasingly low interest rates). While more right-wing national governments have pushed large scale rent liberalization, more left-wing Amsterdam governments have developed policies to steer liberalization, for example through attempting to keep rent levels in check (Hochstenbach & Ronald, 2020). The result is a combination of policy agendas on both state levels that have resulted in the hollowing out of rent regulations and facilitation of temporary contracts. These ultimately leave younger groups at a disadvantage compared to older cohorts, who continue to benefit from layers of tenant protection and rent controls from earlier decades. The Dutch case therefore highlights the active role of states in driving and mediating liberalized rental growth. It demonstrates the drivers of housing inequalities through the case of a more social democratic, welfare rich and highly regulated housing context. This contrasts countries such as the UK where the role of the state in this transformation has been largely in the guise of the market.

Third, we show that young adults’ increasing dependence on private rental housing in Amsterdam is not only driven by decreasing access to homeownership but, even more so, by decreasing access to regulated rental housing. The post-GFC restructuring of rental markets has been more salient in explaining the increase in young households relying on a more costly and precarious rental sector, than declining rates of homeownership amongst this cohort. The focus on the latter in ‘generation rent’ discourses perhaps implies an exaggerated focus on “the plight” of middle-class groups, as well as a persistent ideology of homeownership, at least in policy-making and public debate. Making this distinction is crucial as (largely right-wing) political parties advocate for increasing homeownership rates as an attempt to solve young adults’ housing crisis. This approach does little for low- and even middle-income young adults, with potentially adverse effects for these groups (Hilber, 2015; Carozzi et al., 2020).

Beyond these key conclusions, our analysis brings a number of other, more universal issues to the fore. Recent transformations in Amsterdam illustrate the various ways financialization has intensified since 2010 and, arguably, become more ubiquitous. In the Netherlands, the failures of the housing system during the GFC justified the adaptation of a new liberalization agenda, with housing reforms supporting the return of rentierism. While housing remains deeply regulated, the city of Amsterdam has been relatively active in turning rental housing into an asset class and attracting capital investment (Aalbers et al., 2021; Hochstenbach & Ronald, 2020). State policies and urban growth strategies have been fundamental to restructuring the sector and repurposing the rental housing market, transforming it to a place of both investment and middle-class residence.

The case of Amsterdam illustrates that while structures and strategies of capital accumulation have changed with regards to housing as a site of wealth accumulation, the state, politics, and housing system pathways continue to play critical roles. There are also consequences for how ‘generation rent’ is formed and the housing outcomes for different groups of younger people. This observation suggests that more attention be directed towards the ways in which rental sectors are liberalized, how national and city level governments interact, and the diverse consequences for young adults from different socio-economic backgrounds. While our analysis identified that recent policy changes have stimulated divisions between existing residents and (younger) newcomers trying to make their way in an increasingly market-driven rental system, we build on this observation by echoing the caution of other studies. That is, to narrowly focus on generational divides while ignoring key dimensions such as class and household type is too simplistic (Hochstenbach & Arundel, 2021; Christophers, 2019; Watt, 2020; Coulter et al., 2020).

Further points for future study have arisen. Whilst we situate the findings of this paper in the context of policy and housing market shifts, further studies which empirically disentangle what has driven the identified changes is an important area for further research. Temporary and informal housing sectors also seem to be gaining traction and more knowledge about these tenures and the profiles of their occupants is required, alongside greater understanding of young adults co-residing in the parental home. Additionally, young adults’ prolonged reliance on often expensive and temporary rental housing may have profound impacts on their mental health and well-being, and research into these outcomes is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their informative and helpful feedback. Thanks also to the municipality of Amsterdam and Kees Dignum for providing access to the original data, and to Rebecca Bentley and Emma Baker for feedback on previous versions of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council, under grant number DP190101188. This grant was awarded to the project “Closing the housing gap: A spotlight on intergenerational inequalities”. It was also supported by the VENI grant from NWO, the Dutch Research Council, under grant number VI. Veni.191S.014. This grant was awarded to Cody Hochstenbach for his project “Investing in inequality: how the increase in private housing investors shapes social divides”.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This paper draws on author calculations of non-public micro-data from the Living in Amsterdam survey (WiA) from the Amsterdam municipality. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors on request.

References

- Aalbers, Manuel B., Hochstenbach, Cody, Bosma, Jelke, & Fernandez, Rodrigo. (2021). The death and life of private landlordism: How financialized homeownership gave birth to the buy-to-let market. Housing, Theory and Society, 38(5), 541–563. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins, Lisa, Cooper, Melinda, & Konings, Martijn. (2020). The asset economy: Property ownership and the new logic of inequality. Polity. [Google Scholar]

- AFWC . (2022). Jaarbericht 2021, Tabellen. Amsterdamse Federatie van Woningcorporaties. [Google Scholar]

- Arundel, Rowan, & Lennartz, Christian. (2020). Housing market dualization: Linking insider–outsider divides in employment and housing outcomes. Housing Studies, 35(8), 1390–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Arundel, Rowan, & Ronald, Richard. (2021). The false promise of homeownership: Homeowner societies in an era of declining access and rising inequality. Urban Studies, 58(6), 1120–1140. [Google Scholar]

- August, Martine. (2020). The financialization of Canadian multi-family rental housing: From trailer to tower. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Beswick, Joe, Alexandri, Georgia, Byrne, Michael, Vives-Miró, Sònia, Fields, Desiree, Hodkinson, Stuart, & Janoschka, Michael. (2016). Speculating on London's housing future. City, 20(2), 321–341. [Google Scholar]

- Boterman, Willem, & Van Gent, Wouter. (2014). Housing liberalisation and gentrification: The social effects of tenure conversion in Amsterdam. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 105(2), 140–160. [Google Scholar]

- Brill, Frances, & Durrant, Daniel. (2021). The emergence of a build to rent model: The role of narratives and discourses. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(5), 1140–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Brill, Frances, Raco, Mike, & Ward, Callum. (2022). Anticipating demand shocks: Patient capital and the supply of housing. European Urban and Regional Studies, 0(0), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Buzar, Stefan, Ogden, Philip E, & Hall, Ray. (2005). Households matter: The quiet demography of urban transformation. Progress in Human Geography, 29(4), 413–436. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Michael. (2020). Generation rent and the financialization of housing: A comparative exploration of the growth of the private rental sector in Ireland, the UK and Spain. Housing Studies, 35(4), 743–765. [Google Scholar]

- Carozzi, Felipe, Hilber, Christian A. L., & Yu, Xiaolun. (2020). On the Economic Impacts of Mortgage Credit Expansion Policies: Evidence from Help to Buy, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14620.

- CBS . (2023). Bestaande koopwoningen; verkoopprijzen prijsindex 2015 = 100, regio. Statistics Netherlands, Statline open data. [Google Scholar]

- Christophers, Brett. (2019). A tale of two inequalities: Housing-wealth inequality and tenure inequality. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(3), 573–594. [Google Scholar]

- Christophers, Brett. (2022). Mind the rent gap: Blackstone, housing investment and the reordering of urban rent surfaces. Urban Studies, 59(4), 698–716. [Google Scholar]

- Christophers, Brett, & O’Sullivan, David. (2019). Intersections of inequality in homeownership in Sweden. Housing Studies, 34(6), 897–924. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Ian, Powell, Ryan, & Sanderson, Elizabeth. (2016). Putting the squeeze on “Generation Rent”: Housing benefit claimants in the private rented sector-transitions, marginality and stigmatisation. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, Rory. (2017). Local house prices, parental background and young adults’ homeownership in England and Wales. Urban Studies, 54(14), 3360–3379. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, Rory, Bayrakdar, Sait, & Berrington, Ann. (2020). Longitudinal life course perspectives on housing inequality in young adulthood. Geography Compass, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Crook, Tony, & Kemp, Peter. (2014). Private rental housing: Comparative perspectives. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, Colin. (2009). Privatised keynesianism: An unacknowledged policy regime. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 11, 382–399. [Google Scholar]

- Dewilde, Caroline, & Flynn, Lindsay B. (2021). Post-crisis developments in young adults’ housing wealth. Journal of European Social Policy, 31(5), 580–596. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Rodrigo, Hartlief, Ilona, & Hudig, Kees. (2022). Blackstone als nieuwe huisbaas (Blackstone as new landlord). SOMO. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, Desiree. (2018). Constructing a new asset class: Property-led financial accumulation after the crisis. Economic Geography, 94(2), 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, Lindsay. (2017). Delayed and depressed: From expensive housing to smaller families. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(3), 374–395. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, Ray, & Hirayama, Yosuke. (2015). The financialization of the social project: Embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and homeownership. Urban Studies, 52(2), 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Fuster, Nayla, Arundel, Rowan, & Susino, Juaqin. (2019). From a culture of homeownership to generation rent: Housing discourses of young adults in Spain. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(5), 585–603. [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, Richard, Leaver, Adam, & Silver, Jonathan. (2023). From homes to assets: Transcalar territorial networks and the financialization of build to rent in Greater Manchester. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. Online First [Google Scholar]

- Grander, Martin. (2021). The inbetweeners of the housing markets – young adults facing housing inequality in Malmö, Sweden. Housing Studies, 38(3), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hamnett, Chris, & Randolph, Bill. (1984). The role of landlord disinvestment in housing market transformation: an analysis of the flat break-up market in central London. Transactions of the institute of British geographers, 259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Hilber, Christian. (2015). UK housing and planning policies: The evidence from economic research, CEP election analysis papers 033, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

- Hochstenbach, Cody. (2022). Landlord elites on the Dutch housing market: Private landlordism, class, and social inequality. Economic Geography, 98(4), 327–354. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstenbach, Cody, & Aalbers, Manuel B. (2023). The uncoupling of house prices and mortgage debt: Towards wealth-driven housing market dynamics. International Journal of Housing Policy, Online First, DOI: 10.1080/19491247.2023.2170542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstenbach, Cody, & Arundel, Rowan. (2021). The unequal geography of declining young adult homeownership: Divides across age, class, and space. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 46(4), 973–994. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstenbach, Cody, & Musterd, Sako. (2018). Gentrification and the suburbanization of poverty: Changing urban geographies through boom and bust periods. Urban Geography, 39(1), 26–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstenbach, Cody, & Ronald, Richard. (2020). The unlikely revival of private renting in Amsterdam: Re-regulating a regulated housing market. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(8), 1622–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Hoolachan, Jenny, McKee, Kim, Moore, Tom, & Soaita, Adriana M. (2017). Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: Economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman, Carla, & Mulder, Clara. (2022). Insecure tenure in Amsterdam: Who rents with a temporary lease, and why? A baseline from 2015. Housing Studies, 37(8), 1422–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Hulse, Kath, Burke, Terry, Ralston, Liss, & Stone, Wendy. (2012). The Australian private rental sector: Changes and challenges, Ahuri positioning paper No.149. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Kadi, Justin, & Lilius, Johanna. (2022). The remarkable stability of social housing in Vienna and Helsinki: a multi-dimensional analysis. Housing Studies, Online First, DOI: 10.1080/02673037.2022.2135170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Peter. (2015). Private renting after the global financial crisis. Housing Studies, 30(4), 601–620. [Google Scholar]

- Lennartz, Christian, Arundel, Rowan, & Ronald, Richard. (2016). Younger adults and homeownership in Europe through the global financial crisis. Population, Space and Place, 22, 823–835. [Google Scholar]

- Maalsen, Sophia. (2020). ‘Generation share’: Digitalized geographies of shared housing. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(1), 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, Kim. (2012). Young people, homeownership and future welfare. Housing Studies, 27(6), 853–862. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, Kim, Moore, Tom, Soaita, Adriana, & Crawford, Joe. (2017). ‘Generation rent’ and the fallacy of choice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 318–333. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, Kim, Soaita, Adriana, & Hoolachan, Jennifer. (2020). ‘Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: Self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters. Housing Studies, 35(8), 1468–1487. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, M. (2016). From gentrification to youthification? The increasing importance of young age in delineating high-density living. Urban Studies, 53(14), 2903–2920. [Google Scholar]

- Nethercote, Megan. (2020). Build-to-rent and the financialization of rental housing: Future research directions. Housing Studies, 35(5), 839–874. [Google Scholar]

- Paccoud, Antoine. (2017). Buy-to-let gentrification: Extending social change through tenure shifts. Environment and Planning A, 49(4), 839–856. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, R. (2008). The ideology of home ownership: Homeowner societies and the role of housing. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, Richard, & Kadi, Justin. (2018). The revival of private landlords in Britain’s post-homeownership society. New Political Economy, 23(6), 786–803. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, Richard, Schijf, Pauline, & Donovan, Kelly. (2023). The institutionalization of shared rental housing and commercial co-living. Housing Studies, Online First, DOI: 10.1080/02673037.2023.2176830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Collins, Josh, Macfarlane, Laurie, & Lloyd, Toby. (2017). Rethinking the economics of land and housing. Zed Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Salomons, Michelle, & Voogt, Felix. (2020). Tijdelijke contracten zijn er voor de huisjesmelkers. De Groene Amsterdammer. 7 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taşan-Kok, Tuna, Özogul, Sara, & Legarza, Andre. (2021). After the crisis is before the crisis: Reading property market shifts through Amsterdam’s changing landscape of property investors. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(4), 375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Uyttebrouck, Constance, Van Bueren, Ellen, & Teller, Jacques. (2020). Shared housing for students and young professionals: Evolution of a market in need of regulation. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Van Duijne, Robbin Jan, & Ronald, Richard. (2018). The unraveling of Amsterdam’s unitary rental system. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 33(4), 633–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gent, Wouter. (2013). Neoliberalization, housing institutions and variegated gentrification: How the ‘third wave’ broke in Amsterdam. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2), 503–522. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gent, Wouter, & Hochstenbach, Cody. (2020). The neo-liberal politics and socio-spatial implications of Dutch post-crisis social housing policies. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(1), 156–172. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kempen, Ronald, & Priemus, Hugo. (2002). Revolution in social housing in the Netherlands possible effects of new housing policies. Urban Studies, 39(2), 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, Thomas. (2023). Rental proptech platforms: Changing landlord and tenant power relations in the UK private rental sector? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 55(2), 339–358. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, Richard. (2018). Capitalizing on the state: The political economy of real estate investment trusts and the ‘resolution’ of the crisis. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 90, 206–218. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, Paul. (2020). Press-ganged’ generation rent: Youth homelessness, precarity and poverty in East London. People, Place and Policy, 14(2), 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- White, Tim. (2023). Beds for rent. Economy and Society, Online First, DOI: 10.1080/03085147.2023.2245633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wijburg, Gertjan, Aalbers, Manuel B, & Heeg, Susanne. (2018). The financialisation of rental housing 2.0: Releasing housing into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation. Antipode, 50(4), 1098–1119. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This paper draws on author calculations of non-public micro-data from the Living in Amsterdam survey (WiA) from the Amsterdam municipality. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors on request.