Abstract

Erythromycin and tetracycline resistance was analyzed in 37 Clostridium difficile clinical isolates. Strains of different clonal origins showed different erythromycin and tetracycline resistance determinants and different genetic arrangements of the elements. In strains of recent isolation, the presence of Tn916-like elements, never found before in C. difficile clinical isolates, has been demonstrated.

In Clostridium difficile, macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance is usually due to an erm(B) gene carried by the Tn5398, a mobile element that shows heterogeneous genetic organization (8, 21). C. difficile strains can be grouped in different phenotypic classes on the basis of erythromycin and clindamycin resistance patterns, and these classes seem to be related to the presence of different alleles of the erm(B) gene (21, 22). Tetracycline resistance is predominantly due to a tet(M) gene carried by the conjugative transposon Tn5397 (13). This element differs from Tn916 since it contains a group II intron and has different integration/excision modules (16, 17, 24). The Tn916 conjugative transposon has never been found in C. difficile, except in one environmental isolate (25).

The purpose of this study was to characterize the erythromycin and tetracycline resistance elements harbored by 37 selected clinical isolates of C. difficile, resistant to erythromycin and/or tetracycline and erm(B) and/or tet(M) positive.

The MICs were determined by E-test (AB Biodisk), and the breakpoints were ≥4 mg/liter for erythromycin and clindamycin and ≥8 mg/liter for tetracycline (14). tet(M) and erm(B) genes were detected by PCR, by using primers TETMd-TETMr to amplify 1.0 kb of tet(M) and primers E5-E6 to amplify 0.6 kb of erm(B) (22). The isolates belonged to four PCR ribotypes identified in our country. Two of them, PCR ribotypes A and D, grouped strains mainly isolated before 1990, whereas PCR ribotypes L and R grouped strains mainly isolated in the years 2000 and 2001 (22). As shown in Table 1, all PCR ribotype A strains harbored both erm(B) and tet(M), whereas the copresence of both genes was observed only in two strains belonging to PCR ribotype R and one to PCR ribotype D. Five strains, one PCR ribotype D and four PCR ribotype R, were resistant to erythromycin and resistant or inducibly resistant to clindamycin but erm(B) negative. By using the primers reported in Marilyn C. Roberts' website, http://faculty.washington.edu/marilynr/, these strains were also examined by PCR for erm(A), erm(C), erm(F), erm(Q), and mef(A) genes and resulted negative (data not shown). These results were confirmed by hybridization assays using a DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) and, as probes, the amplified gene fragments from the following control strains and plasmids: Staphylococcus aureus RN4658 for erm(A), C. difficile 630 for erm(B), S. aureus RN2442 for erm(C), Streptococcus pneumoniae PN137 for mef(A), R751Ω 4 for erm(F), and JIR2879 for erm(Q). The results suggest that erythromycin resistance in these isolates could be due to an erm or mef class different from those examined or to a different MLSB resistance mechanism and indicate the need to monitor the circulation of resistant strains, particularly in hospital environments.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the 37 C. difficile isolates examined in the study

| PCR ribotype | MICs/MIC range (mg/liter)a

|

Detection of:

|

erm(B)-negative strains resistant to erythromycin | Detection of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERY | CLI | TET | erm(B) | tet(M) | erm(B)/tet(M) | tndX | int | ||

| A (21)b | 256 (4)/12-48 (17) | 256 (21) | 256 (2)/12-64 (19) | − | − | + (21) | + (21) | − | |

| D (4) | 256 (4) | 256 (3)/3 (1)c | 32 (1)/0.016-0.064 (3) | + (3) | − | + (1) | 1 | + (1) | − |

| L (1) | 1.0 (1) | 4 (1) | 1.0 (1) | − | + (1) | − | − | + (1) | |

| R (11) | 256 (8)/0.032-1.0 (3) | 256 (4)/4-12 (3)/0.5-1.5 (4)c | 12-16 (6)/0.023-4 (5) | + (2) | + (7) | + (2) | 4 | − | + (9) |

ERY, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin; TET, tetracycline.

The number of strains is shown in parentheses throughout.

One strain of PCR ribotype D and one of PCR ribotype R were inducibly resistant to clindamycin. Resistance to clindamycin was induced by a pregrowth on blood agar plates containing 0.05 mg/liter of erythromycin.

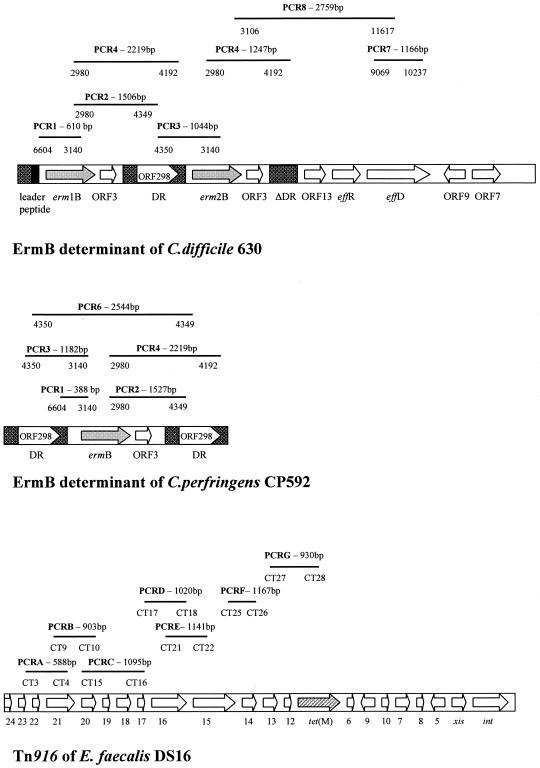

Erythromycin resistance determinants were characterized using seven of the eight amplifications described by Farrow et al. (8). The amplified regions in C. difficile 630 (7) and Clostridium perfringens CP592 (2) ErmB elements and the expected size of PCR fragments are shown in Fig. 1. C. difficile 630, F17, and C191 (21) were used as control strains. Seven different arrangements of the ErmB determinant were identified and named, for convenience, types E1 to E7 (Table 2). All strains were highly resistant to erythromycin and clindamycin (MIC ≥ 256 mg/liter), except isolates with a genetic arrangement E2, which showed lower resistance levels to erythromycin (MICs of 12 to 48 mg/liter) (data not shown). Genetic arrangements E1, E2, E3, E4, and E6 were similar to those already identified (7, 8, 21), whereas two arrangements, E5 and E7, found in PCR ribotype R strains, were new. Type E5, with a product of about 1,247 bp by PCR 4, probably had an incomplete direct repeat sequence located downstream of the erm(B) gene, whereas type E7 showed only the erm(B) gene, with a PCR 1 product of about 2 kb. The number of erm(B) genes and their sequence were detected by hybridization assay, by using the erm(B) PCR product as probe and by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism, respectively (21, 22). Types E1 and E2 had an erm(B) similar to that of C. difficile 630, whereas types E3 to E7 had an erm(B) similar to that of C. perfringens CP592 (2, 22). As already reported (8, 21), all E1 strains had two erm(B) copies with two hybridizing bands at 2.0 and 2.3 kb, whereas the other strains had one erm(B) copy with a band at 3.0 or 2.3 kb, when probed with the erm(B) gene (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

PCR analysis of the genetic organization of the ErmB determinants and the Tn916-like elements. The primers used to analyze the ErmB determinants and the Tn916-like elements were described by Farrow et al. (8) and Wang et al. (25), respectively. The expected amplified fragments are shown as bars in relation to the arrangements of the elements from C. difficile 630 (GenBank accession no. AF109075), C. perfringens CP592 (GenBank accession no. U18931), and E. faecalis DS16 (GenBank accession no. U09422). The length of the fragments are reported in bp, and the primers used for each amplification are indicated below the bars.

TABLE 2.

Results of the molecular analysis of the ErmB determinants detected in the C. difficile clinical isolates examined in this study

| PCR ribotype | ErmB determinant arrangements (no. of strains) | Results of PCR assays (length in bp)a

|

C. difficile strains with a similar element (reference) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| A | E1 (4) | + (610) | + (1,506) | + (1,044) | + (2,219/1,247) | − | + (1,166) | + (2,759) | 630 (8) | |

| E2 (17) | + (610) | − | − | + (1,247) | − | − | − | C191 (21) | ||

| D | E3 (1) | + (388) | + (1,527) | − | + (2,219) | − | − | − | F17 (21) | |

| E4 (2) | + (388) | + (1,527) | − | − | − | − | − | 662 (8) | ||

| R | E4 (1) | + (388) | + (1,527) | − | − | − | − | − | 662 (8) | |

| E5 (1) | − | − | − | + (1,247) | − | − | − | This study | ||

| E6 (1) | + (388) | − | − | − | − | − | − | L289 (8) | ||

| E7 (1) | + (2,000) | − | − | − | − | − | − | This study | ||

Results of PCR assays for amplification of Erm determinant regions and approximate length of fragments in bp.

The int gene, a marker for the Tn916-like elements, was detected using the primer couple INTf-INTr (11), whereas the tndX gene, characterizing the Tn5397-like elements, was detected using primers tndx1, 5′ TACATTGTTAAAACAGCAAGC 3′, and tndx3, 5′ TATCAATGAGACACTGCTA 3′. S. pneumoniae PN20 (11) and C. difficile 630 (26) were used as controls for the int and tndX genes, respectively. All PCR ribotype A and D strains, showing a tet(M) gene, were positive for tndX, whereas all PCR ribotype L and R strains carrying a tet(M) gene were int positive (Table 1). No strain had both the tndX and int genes, confirming previous results obtained in vitro by Wang et al. (24). All C. difficile strains with a Tn5397-like element were resistant to tetracycline, with MICs between 12 and 256 mg/liter, whereas C. difficile strains with a Tn916-like element could be resistant, inducibly resistant, or susceptible to tetracycline, with MICs between 0.023 and 16 mg/liter.

Tn916-like elements were characterized using seven of the primer couples reported by Wang et al. (25). The primers were designed on the Tn916 element of Enterococcus faecalis DS16 (10). The amplified regions and the expected sizes of PCR fragments are shown in Fig. 1. PCR analysis of the Tn916-like elements showed four different genetic organizations that, for convenience, we named Ta to Td (Table 3). C. difficile isolates with MICs from 8 to 16 mg/liter, resistant or inducibly resistant to tetracycline, showed elements very similar to those found in E. faecalis and this arrangement, named Ta, was the prevalent. Type Tb was identified in one inducibly resistant strain showing the amplified fragments by PCR C (orf 20-19-18-17) and G [orf 13-12-tet(M) partial] of about 4 kb and 870 bp, respectively. The same size variation in the PCR G product was observed in one resistant strain (type Tc), whereas one tetracycline-susceptible isolate was characterized as type Td for the absence of amplification of the region containing orf 16-15 (PCR E).

TABLE 3.

Results of the molecular analysis of the Tn916-like elements detected in the C. difficile clinical isolates examined in this study

| Tn916-like element arrangement (no. of strains) | Results of PCR assays (length in bp)a

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

| Tb (1) | + (588) | + (903) | + (4,000) | + (1,020) | + (1,141) | + (1,167) | + (870) |

| Ta (7) | + (588) | + (903) | + (1,095) | + (1,020) | + (1,141) | + (1,167) | + (930) |

| Tc (1) | + (588) | + (903) | + (1,095) | + (1,020) | + (1,141) | + (1,167) | + (870) |

| Td (1) | + (588) | + (903) | + (1,095) | + (1,020) | − | + (1,167) | + (930) |

Results of PCR assays for amplification of Tn916 regions and approximate length of fragments in bp.

The Tn5397-like elements were always found in C. difficile strains harboring an ErmB determinant, whereas Tn916-like elements were found either in erm(B)-positive strains or in 80% of C. difficile isolates resistant to erythromycin but erm(B) negative (Table 1). Further studies will be necessary to verify whether erm(B) and tet(M) are linked on the same element, as observed in other microorganisms (3, 5, 6, 15).

The Tn916 transposon and related elements are widespread in many clinically relevant gram-positive bacteria (5, 15, 18, 19). Their ability to mobilize plasmids or other conjugative transposons could be relevant for acquisition of multiple antibiotic resistance and other virulence characteristics by C. difficile (1, 4, 9, 12, 20, 23). Further investigations will be carried out to better characterize the erythromycin and tetracycline resistance determinants detected in this study and their relevance in C. difficile epidemiology.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the European Community's Fifth Framework Programme “Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources.” Contract no. QLK2-CT-2002-00843-ARTRADI.

We thank R. Novick, L. E. Comstock, J. Rood, and A. Pantosti for supplying the control strains or plasmids for erm(A), erm(C), erm(F), erm(Q), and mef(A) genes.

We are grateful to Tonino Sofia for editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayoubi, P., A. O. Kilic, and M. N. Vijayakumar. 1991. Tn5253, the pneumococcal Ω(cat tet) BM6001 element, is a composite structure of two conjugative transposons, Tn5251 and Tn5252. J. Bacteriol. 173:1617-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berryman, D. I., and J. I. Rood. 1995. The closely related ermB-ermAM genes from Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus faecalis (pAMb1), and Streptococcus agalactiae (pIP501) are flanked by variants of a directly repeated sequence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1830-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caillaud F., C. Carlier, and P. Courvalin. 1987. Physical analysis of the conjugative shuttle transposon Tn1545. Plasmid 17:58-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clermont, D., and T. Horaud. 1994. Genetic and molecular studies of a composite chromosomal element (Tn3705) containing a Tn916-modified structure (Tn3704) in Streptococcus anginosus F22. Plasmid 31:40-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clewell, D. B., S. E. Flannagan, and D. D. Jaworski. 1995. Unconstrained bacterial promiscuity: the Tn916-Tn1545 family of conjugative transposons. Trends Microbiol. 3:229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courvalin, P., and C. Carlier. 1987. Tn1545: a conjugative shuttle transposon. Mol. Gen. Genet. 206:259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrow, K. A., D. Lyras, and J. I. Rood. 2000. The macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinant from Clostridium difficile 630 contains two erm(B) genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:411-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrow, K. A., D. Lyras, and J. I. Rood. 2001. Genomic analysis of the erythromycin resistance element Tn5398 from Clostridium difficile. Microbiology 147:2717-2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flannagan, S. E., and D. B. Clewell. 1991. Conjugative transfer of Tn916 in Enterococcus faecalis: transactivation of homologous transposons. J. Bacteriol. 173:7136-7141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flannagan, S. E., L. A. Zitzow, Y. A. Su, and D. B. Clewell. 1994. Nucleotide sequence of the 18-kb conjugative transposon Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 32:350-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gherardi, G., M. Del Grosso, A. Scotto D'Abusco, F. D'Ambrosio, G. Dicuonzo, and A. Pantosti. 2003. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of two penicillin-susceptible serotype 6B Streptococcus pneumoniae clones circulating in Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2855-2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Bouguenec, C., G. de Cespedes, and T. Horaud. 1990. Presence of chromosomal elements resembling the composite structure Tn3701 in streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 172:727-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullany, P., M. Wilks, I. Lamb, C. Clayton, B. Wren, and S. Tabaqchali. 1990. Genetic analysis of a tetracycline resistance element from Clostridium difficile and its conjugal transfer to and from Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1343-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1993. Methods for antimicrobial testing of anaerobic bacteria, 2nd ed. Approved standard M11-A3. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 15.Rice, L. B. 1998. Tn916 family conjugative transposons and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1871-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts, A. P., V. Braun, C. von Eichel-Streiber, and P. Mullany. 2001. Demonstration that the group II intron from the clostridial conjugative transposon Tn5397 undergoes splicing in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 183:1296-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts, A. P., P. A. Johanesen, D. Lyras, P. Mullany, and J. I. Rood. 2001. Comparison of Tn5397 from Clostridium difficile, Tn916 from Enterococcus faecalis and the CW459 tet(M) element from Clostridium perfringens shows that they have similar conjugation regions but different insertion and excision modules. Microbiology 147:1243-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts, M. C. 1994. Epidemiology of tetracycline-resistance determinants. Trends Microbiol. 2:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salyers, A. A., and C. F. Amabile-Cuevas. 1997. Why are antibiotic resistance genes so resistant to elimination? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2321-2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salyers, A. A., and N. B. Shoemaker. 1996. Resistance gene transfer in anaerobes: new insights, new problems. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23(Suppl. 1):S36-S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spigaglia, P., and P. Mastrantonio. 2003. Analysis of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance determinant in strains of Clostridium difficile. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spigaglia, P., and P. Mastrantonio. 2004. Comparative analysis of Clostridium difficile clinical isolates belonging to different genetic lineages and time periods. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torres, O. R., R. Z. Korman, S. A. Zahler, and G. M. Dunny. 1991. The conjugative transposon Tn925: enhancement of conjugal transfer by tetracycline in Enterococcus faecalis and mobilization of chromosomal genes in Bacillus subtilis and E. faecalis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 225:395-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, H., A. P. Roberts, D. Lyras, J. I. Rood, M. Wilks, and P. Mullany. 2000. Characterization of the ends and target sites of the novel conjugative transposon Tn5397 from Clostridium difficile: excision and circularization is mediated by the large resolvase, TndX. J. Bacteriol. 182:3775-3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, H., A. P. Roberts, and P. Mullany. 2000. DNA sequence of the insertional hot spot of Tn916 in the Clostridium difficile genome and discovery of a Tn916-like element in an environmental isolate integrated in the same hot spot. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 192:15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wüst, J., and U. Hardegger. 1983. Transferable resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 23:784-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]