Abstract

A total of 103 (0.7%) of 14,236 Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected in four Spanish hospitals from 1989 to 2003 were resistant to rifampin (MICs, 4 to 512 μg/ml). Only sixty-one (59.2%) of these isolates were available for molecular characterization. Resistance was mostly related to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in adult patients and to conjunctivitis in children. Thirty-six different pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns were identified among resistant isolates, five of which were related to international clones (Spain23F-1, Spain6B-2, Spain9V-3, Spain14-5, and clone C of serotype 19F), and accounted for 49.2% of resistant isolates. Single sense mutations at cluster N or I of the rpoB gene were found in 39 isolates, while double mutations, either at cluster I, at clusters I and II, or at clusters N and III, were found in 14 isolates. The involvement of the mutations in rifampin resistance was confirmed by genetic transformation. Single mutations at clusters N and I conferred MICs of 2 μg/ml and 4 to 32 μg/ml, respectively. Eight isolates showed high degrees of nucleotide sequence variations (2.3 to 10.8%) in rpoB, suggesting a recombinational origin for these isolates, for which viridans group streptococci are their potential gene donors. Although the majority of rifampin-resistant isolates were isolated from individual patients without temporal or geographical relationships, the clonal dissemination of rifampin-resistant isolates was observed among 12 HIV-infected patients in the two hospitals with higher rates of resistance.

A global increase in the rates of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to penicillin and multiple antibacterial agents emerged worldwide in the 1980s and 1990s, severely complicating the treatment of pneumococcal infections (12, 17, 20, 23, 24, 25). The use of rifampin (RIF) combined with either β-lactams or vancomycin is recommended for the treatment of meningitis caused by multiresistant pneumococcal isolates (5, 26, 33). The rates of RIF resistance among pneumococci are low and range from 0.1% in the United States (12) to 0.4% in Spain (23) and to 1.4% in Italy (25). RIF resistance is usually preceded by RIF therapy, either for tuberculosis (18) or for prophylaxis or treatment for multidrug-resistant pneumococcal infections (36, 38). RIF is also used in combined therapy to treat staphylococcal infections, and it is extensively used in the prophylaxis of Neisseria meningitidis exposure.

The bactericidal properties of RIF are due to its high affinity of binding to the bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase and inhibit its function (6), which is essential for bacterial growth (21). Structural and biochemical studies of the essential catalytic core of the RNA polymerase (subunit composition, α2ββ′ω) of Thermus aquaticus have revealed that RIF interacts with a pocket of the RNA polymerase β subunit within the DNA-RNA channel and blocks the path of the elongating RNA when the transcript becomes 2 or 3 nucleotides long (6, 40). RIF resistance has been described in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The mutations responsible for this phenotype are localized in highly conserved regions, termed clusters N, I, II, and III, of the rpoB gene, which encodes the β subunit (6) (Fig. 1). The residues involved in RIF resistance in several bacteria (2, 3, 9, 19, 31) form part of the RIF-binding pocket, and 12 of these residues interact directly with the RIF molecule (6). Few studies describing RIF-resistant pneumococcal clinical isolates have been reported (7, 15, 29, 32, 38), and all the mutations identified were localized in clusters N, I, and II. In this study we report on the epidemiological and molecular characteristics of 61 RIF-resistant S. pneumoniae clinical isolates collected during a 15-year period (1989 to 2003) in four Spanish hospitals.

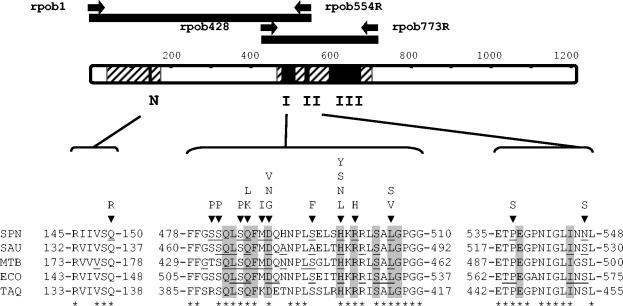

FIG. 1.

Regions of S. pneumoniae RpoB and mutations conferring RIF resistance. RpoB is represented as a bar showing clusters N, I, II, and III (black boxes) and sequenced regions (striped area). The PCR fragments used for transformation (black bars) and primers (black arrows) are indicated above. Amino acids that constitute clusters N, I, and II of S. pneumoniae (SPN), S. aureus (SAU), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), E. coli (ECO), and T. aquaticus (TAQ) are indicated. Amino acid changes found in resistant isolates are shown above the S. pneumoniae sequence, identical residues are indicated with an asterisk below the T. aquaticus sequence, residues that changed in RIF-resistant isolates are underlined, and the 12 residues involved in RIF binding are shaded.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and susceptibility tests.

The bacteria were identified by the standard methodology, and the serotypes were determined by the Quellung reaction. The MICs of penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, and RIF were determined by the microdilution method (Sensititre commercial plates), according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards methods (30). The rifampin MICs of the transformants were determined by microdilution (30) and by a macrodilution method (1) with a casein hydrolysate-based medium with 0.2% sucrose (AGCH) (22). S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 and S. pneumoniae R6 were used for quality control.

Genetic transformation.

S. pneumoniae strain R6 was grown in AGCH and was used as the recipient in transformation experiments, performed as described previously (27). Two DNA fragments were used as donors: a 1,662-bp fragment (RpoB residues M1 to L554, in which the first residue of RpoB is taken as residue 1) and a 1,038-bp fragment (RpoB residues A428 to M773). These fragments were obtained by PCR amplification from the RIF-resistant isolates and from R6, which was used as a control. Colonies were counted after 24 h growth at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in AGCH with 1% agar containing 1 μg/ml of RIF.

PFGE and MLST.

Genomic DNA embedded in agarose plugs was digested with SmaI, and the fragments were separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (28). The PFGE patterns were compared to those of 26 representative international clones from the Pneumococcal Molecular Epidemiology Network (28). Isolates with patterns that varied by three or fewer bands were considered to represent the same PFGE type (37). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was carried out as described previously (14) with one representative RIF-resistant isolate of each dominant PFGE pattern.

PCR amplification and DNA sequence determination.

The RpoB L1 to M773 region was amplified with oligonucleotides rpob1 (5′-TTGACAAGGCTTGGAACTTAT-3′) and rpob773R (5′-GTCATGTAGGCAACGAATTGGG-3′). To amplify the 1,662-bp and the 1,038-bp fragments used in the transformation experiments, oligonucleotides rpob1 and rpob554R (5′-CAAGTGTCCGTAAGATGACAAG-3′) and oligonucleotides rpob428 (5′-CGGTTGGTGAATTGCTTGCCAACCA-3′) and rpob773R, respectively, were used. Amplifications were performed with 0.5 U of Thermus thermophilus thermostable DNA polymerase (Biotools, Madrid, Spain), 0.1 μg of chromosomal DNA, 1 μM (each) of the synthetic oligonucleotide primers, and 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate in the buffer recommended by the manufacturers. Amplification was achieved with an initial cycle of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C; 25 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 55°C, and a 90-s or 180-s polymerase extension step at 72°C; and a final 3-min extension step at 72°C. PCR fragments were purified with MicroSpin S400 HR columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Pistcatway, NJ) and sequenced by using the oligonucleotides used in the PCR experiments and the internal primers with an Applied Biosystems Prism 377 DNA sequencer by the protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences submitted to GenBank were assigned the following accession numbers: AY695455 to AY695495, AY695497 to AY695516, and AY785246 (for the RIF-resistant isolates); AY695496 (for Streptococcus oralis ATCC 10557); and AY785247 (for S. oralis NCTC 11427).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Epidemiological characterization of S. pneumoniae isolates.

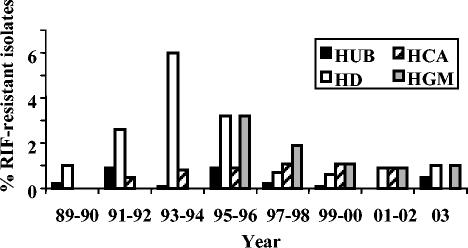

The overall prevalence of RIF resistance among 14,236 pneumococci isolated from clinical specimens in four Spanish hospitals from 1989 to 2003 was 0.7% (103 isolates with MICs ≥4 μg/ml). However, geographical variations in resistance rates were found: 0.3% in Hospital Central de Asturias (HCA) in the northwest of Spain, 0.4% in Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge (HUB) in the northeast of Spain (Barcelona), 1.1% in Hospital Gregorio Marañón (HGM) in the central part of Spain (Madrid), and 1.1% in Hospital de Donostia (HD) in the north of Spain (Guipuzcoa). The frequency of RIF-resistant isolates in each hospital from 1989 to 2003 is shown in Fig. 2. Two hospitals, HCA and HUB, presented low rates during the study period (0 to 1.1%), whereas HD and HGM had higher rates, 6% in the 1993-1994 period and 3.2% in the 1995-1996 period, respectively. These increases in the rates of resistance were associated with the dissemination of four RIF-resistant clones among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients in HD and HGM. From 1999 to 2003 the rates of RIF resistance were lower than 1.1% in the four hospitals (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Frequencies of RIF-resistant isolates in four hospitals during the period from 1989 to 2003. HD, n = 4,211 isolates; HUB, n = 5,381 isolates; HCA, n = 1,056; HGM, n = 3,588.

Only 61 (59.2%) of 103 RIF-resistant isolates (1 per patient) were recovered for further studies from the stock cultures, accounting for more than 50% of RIF-resistant isolates collected annually in each hospital. Among the 61 RIF-resistant isolates studied, 47 were isolated from adults (age, 21 to 76 years) and 14 were isolated from children (<15 years). The sources of the isolates from adults were sputum (n = 28), a conjunctival swab (n = 1), blood (n = 11), pleural fluid (n = 2), bronchoalveolar fluid (n = 2), a protected catheter brush specimen (n = 1), pus (n = 1), and ascitic fluid (n = 1). The majority of pediatric isolates (12 of 14) were from children who had conjunctivitis and who were younger than 1 year of age, and the remaining 2 isolates were from the blood of an 8-year-old HIV-infected girl and from a 14-year-old child with conjunctivitis, respectively. More than half (32 of 61; 52.4%) of the RIF-resistant isolates were from HIV-infected adult patients. Moreover, the majority of invasive isolates (15 of 19; 79.0%) and isolates from sputum (18 of 28; 64.3%) were also from HIV-infected patients.

The in vitro activities of seven antimicrobial agents against the 61 RIF-resistant isolates was determined, and the results are summarized in Table 1. Forty-seven (77.1%) isolates were resistant to penicillin (29 intermediate resistant and 18 resistant), and 30 (49.2%) were erythromycin resistant. Multidrug resistance (defined as resistance to three or more chemically unrelated drugs) was detected in 41 isolates (67.2%), and 14 of them were resistant to six drugs (penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and co-trimoxazole). Eight of the RIF-resistant isolates (13.1%) were susceptible to the other six antibiotics studied.

TABLE 1.

In vitro activities of seven antimicrobial drugs against 61 RIF-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Susceptiblity breakpoint (μg/ml) | Percenta

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 90% | Range | S | I | R | I + R | ||

| Penicillin | 0.5 | 2 | 0.03-8 | ≤0.06 | 22.9 | 47.5 | 29.5 | 77.1 |

| Erythromycin | 0.06 | ≥256 | 0.06-≥256 | ≤0.25 | 50.8 | 0 | 49.2 | 49.2 |

| Clindamycin | 0.06 | ≥256 | 0.06-≥256 | ≤0.25 | 52.5 | 0 | 47.5 | 47.5 |

| Tetracycline | 16 | 64 | 0.12-64 | ≤2 | 34.4 | 0 | 65.6 | 65.6 |

| Chloramphenicol | 4 | 16 | 2-32 | ≤4 | 56.4 | 0 | 43.6 | 43.6 |

| Co-trimoxazole | ≥4/76 | ≥4/76 | 0.5/9.5-≥4/76 | ≤0.5/9.5 | 32.2 | 1.6 | 66.1 | 67.7 |

| Rifampin | 32 | 512 | 4-512 | ≤1 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; and R, resistant (according to NCCLS 2004 interpretive criteria).

Next, the serotypes of the 61 RIF-resistant isolates was determined. Eighteen different serotypes were identified, with the following distribution: 6B (12 isolates), 23F (11 isolates), 14 (8 isolates), 19F (6 isolates), 11 (4 isolates), 6A (3 isolates), 4 (2 isolates), 9N (2 isolates), 9V (2 isolates), and 1 isolate of each of the remaining serotypes (3, 7F, 15F, 18C, 20, 21, 23A, 31, and 34). Two isolates were nontypeable.

The 61 RIF-resistant isolates were also characterized by their PFGE patterns. A total of 36 different PFGE patterns were identified; 5 PFGE patterns accounted for 30 (49.2%) isolates: Spain23F-1 (11 isolates), Spain6B-2 (9 isolates), Spain9V-3 (2 isolates), Spain14-5 (2 isolates), and clone C of serotype 19F (6 isolates). These four international multiresistant epidemic clones have been common in Spain since the 1980s (8, 16, 24, 34). The association between PFGE patterns and global international clones (28) was confirmed by MLST of one representative isolate of each PFGE type listed in Table 2: Rif-36 (Spain23F-1) had sequence type 81 (ST81); Rif-19 (Spain6B-2) had ST90; Rif-55 (Spain9V-3) had ST156; Rif-15 (Spain14-5) had ST17, which is a single-locus variant of the reference strain with ST18; and Rif-3 (clone C of serotype 19F) had ST89. Clone C of serotype 19F (ST89) has been identified in Spain among isolates from patients with meningitis (16) and among ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates (10), and it has also been found sporadically in Italy (11) and Denmark (http://www.mlst.net).

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic characteristics and changes in RpoB among the most prevalent RIF-resistant pneumococcal clones

| PFGEa | Isolate | Serotype | Site | Yr | Originb | Resistance patternc | Nucleotide polymorphisms at rpoBd | Amino acid changes at RpoBe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain23F-1 | Rif-7 | 23F | HD | 1991 | Sputum | PTCSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | D489N, R501H |

| Rif-14 | 23F | HD | 1993 | Sputum | PTCSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | H499N | |

| Rif-22 | 23F | HD | 1994 | Blood | PTCSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | H499N | |

| Rif-34 | 23F | HGM | 1996 | Blood | PTCEClSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | M488I, H499Y | |

| Rif-35 | 23F | HGM | 1996 | Blood | PTCEClSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | M488I, H499Y | |

| Rif-36 | 23F | HGM | 1996 | Blood | PTCEClSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | M488I, H499Y | |

| Rif-38 | 23F | HGM | 1996 | Blood | PTCEClSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | M488I, H499Y | |

| Rif-39 | 23F | HGM | 1996 | Pus | PTCEClSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | M488I, H499Y | |

| Rif-63 | 23F | HD | 2001 | Eye | PTCEClSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | L506S | |

| Rif-75 | 23F | HUB | 1995 | Sputum | PTEClSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551, S498 | H499N | |

| Rif-76 | 23F | HUB | 1997 | Sputum | PTCSxTR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | H499Y | |

| Spain6B-2 | Rif-40 | 6B | HD | 1996 | Sputum | PTCR | A516, V520, Q535, G551 | H499Y |

| Rif-42 | 6B | HGM | 1997 | BAL | PTEClSxTR | I468, Q535 | Q150R | |

| Rif-18 | 6B | HD | 1994 | Sputum | PTEClR | I468, Q535 | D489G, L506V | |

| Rif-19 | 6B | HD | 1994 | Blood | PTEClR | I468, Q535 | D489G, L506V | |

| Rif-30 | 6B | HD | 1995 | Blood | PTEClR | I468, Q535 | D489G, L506V | |

| Rif-17 | 6B | HUB | 1994 | Sputum | PTCEClSxTR | I468, Q535 | D489N, P537S | |

| Rif-23 | 6B | HUB | 1995 | Sputum | PTCEClSxTR | I468, Q535 | H499Y | |

| Rif-53 | 6B | HD | 1999 | Sputum | PTCEClSxTR | I468, Q535 | H499Y | |

| Rif-13 | 6B | HCA | 1993 | BPS | PTCSxTR | Y589F, I608V, I624V, N669D, Q671K, H499N | ||

| Spain9V-3 | Rif-55 | 14f | HCA | 2000 | Pleural | PSxTR | I468, Q535 | D489V |

| Rif-1 | 9V | HD | 1990 | Sputum | PSxTR | I468, Q535 | H499Y | |

| Spain14-5 | Rif-15 | 14 | HD | 1993 | Sputum | PTCEClSxTR | Y589F, H499N | |

| Rif-16 | 14 | HD | 1993 | Sputum | PTCEClSxTR | Y589F, H499N | ||

| Clone Cg | Rif-2 | 19F | HUB | 1991 | Sputum | PTSxTR | A474, V520, Q535 | S481P, H499Y |

| Rif-3 | 19F | HUB | 1991 | Sputum | PTSxTR | A474, V520, Q535 | D489V | |

| Rif-12 | 19F | HD | 1999 | Eye | PTCEClSxTR | A474, V520, Q535 | H499Y | |

| Rif-28 | 19F | HUB | 1995 | Sputum | PCSxTR | A474, V520, Q535 | H499N | |

| Rif-37 | 19F | HGM | 1996 | Sputum | PTEClSxTR | A474, V520, Q535 | H499N | |

| Rif-31 | 19F | HD | 1995 | Blood | PTCSxTR | Y589F, D489V |

PFGE SmaI patterns.

BAL, bronchoalveolar wash specimen; BPS, bronchial protected catheter brush specimen.

P, resistant to penicillin (MIC, 0.12 to 4 μg/ml); T, resistant to tetracycline (MIC, ≥4 μg/ml); C, resistant to chloramphenicol (MIC, ≥8 μg/ml); E, resistant to erythromycin (MIC, ≥0.5 μg/ml); Cl, resistant to clindamycin (MIC, ≥0.5 μg/ml); SxT, resistant to trimethropin-sulfamethoxazole (MICs, ≥4/76 μg/ml); R, resistant to RIF (MIC, ≥4 μg/ml).

The RpoB regions sequenced were L42 to V175 and Q464 to T700. Nucleotide polymorphisms are indicated by the residue number; the changes observed were I468 (ATT instead ATC), A474 (GCG instead GCA), A516 (GCT instead GCC), V520 (GTA instead GTG), Q535 (GAG instead GAA), G551 (GGT instead GGA), and S498 (TCA instead TCT).

Residue changes involved in RIF resistance are showed in boldface, and double underlining indicates that the residue is located in a gene with a mosaic structure.

Capsular switching.

C, PFGE type related to serotype 19F with MLST type 89.

In general, those isolates that shared the same PFGE pattern had the same rpoB polymorphisms with respect to the sequence of strain R6 (Table 2). However, there were four exceptions: two isolates with rpoB mosaic genes (Rif-13 of the Spain6B-2 clone and Rif-31 of clone C of serotype 19F), one isolate (Rif-40 of Spain6B-2 clone) which had those polymorphisms corresponding to the Spain23F-1 clone, and one isolate (Rif-75 of the Spain23F-1 clone) with an additional polymorphism at codon S498.

Twelve RIF-resistant isolates were isolated from 12 HIV-infected patients and grouped in four clusters (Table 2). One cluster included five isolates of the Spain23F-1 clone (Rif-34, -35, -36, -38, and-39) isolated from invasive samples in HGM (Madrid) in 1996. The characteristics of these isolates and the presence of 2 amino acid changes in RpoB (M488I and H499Y) suggest the cross-transmission of RIF-resistant pneumococci among HIV-infected patients. The remaining three clusters were identified at HD (Guipuzcoa) from 1993 to 1995 and included two isolates of the Spain23F-1 clone (Rif-14 and -22), three isolates of the Spain6B-2 clone (Rif-18, -19, and -30), and two isolates of the Spain14-5 clone (Rif-15 and -16). A temporal or geographical relationship could not be found among the remaining isolates, suggesting that RIF resistance among pneumococci is mainly a sporadic event that occurs in individual patients.

Mapping of mutations involved in RIF resistance.

Two RpoB regions, L42 to V175 (including cluster N) and Q464 to T700 (including clusters I, II, and III), were sequenced (Fig. 1). Nucleotide sequence comparisons of the Q464 to T700 region among RIF-resistant isolates and strain R6 revealed 53 isolates with low nucleotide sequence variations (≤0.7%) and 8 isolates with high nucleotide sequence variations (2.0 to 10.9%). Among the 53 isolates with low variations, 39 had single sense mutations and 14 double sense mutations (Table 3). Single mutations would produce amino acid changes at cluster N (Q150) or cluster I (S481, S482, Q486, D489, S495, H499, or L506) (Fig. 1). The only amino acid change found at cluster N was Q150R, which is involved in low-level resistance, as reported before (29). Twelve residues of clusters I and II (shadowed in Fig. 1) that are conserved in pneumococci and in other bacteria are directly involved in the interaction with RIF in the T. aquaticus enzyme (6). Most RIF-resistant isolates had changes at five of these residues (Q486, D489, H499, R501, and L506; Table 3). Position H499 was the most frequently affected (26 of 39 single mutants), as previously found in pneumococci, either clinical isolates (15, 32) or laboratory mutants (27), as well as in other bacteria (2, 3, 9, 19, 31). The prevalence of substitutions at H499 could be due to the low biological cost imposed by the presence of changes at this residue, as has been reported for the H499N change in Staphylococcus aureus (39) and for the H499Y change in S. aureus (39) and Escherichia coli (35). Isolates with the highest MICs (128 μg/ml) carried the Q486L, D489V, or H499Y change (Table 3). Two of the single changes, L506S and H499S, have not been reported before. Double mutations would produce changes at one residue of cluster N and one residue of cluster III (isolate Rif-52; see below), two residues of cluster I, or one residue of cluster I plus a residue of cluster II (Table 3). Although S481, S482, S485, M488, S495, and P537 may not be in direct contact with the RIF molecule (Fig. 1), these residues are located in the vicinity of the RIF-binding pocket. Alteration of these residues may modify the conformation of the pocket and, consequently, the binding of the antibiotic.

TABLE 3.

Relationship between RIF MICs and amino acid changes in RpoB in 53 nonrecombinant RIF-resistant isolates

| RpoB change at cluster:

|

No. of isolates | Isolate or transformant straina | RIF MIC (μg/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | I | II | III | |||

| Q150R | 3 | Rif-42, -61, -67 | 4-8 | |||

| TQ150R/Rif-42 | 2 | |||||

| S481P | 1 | Rif-26 | 8 | |||

| TS481P/Rif-59 | 4 | |||||

| S482P | 1 | Rif-10 | 32 | |||

| TS482P/Rif-10 | 16 | |||||

| Q486K | 1 | Rif-33 | 64 | |||

| TQ486K/Rif-33 | 32 | |||||

| Q486L | 1 | Rif-8 | 128 | |||

| TQ486L/Rif-8 | 32 | |||||

| D489V | 2 | Rif-3, -55 | 128 | |||

| TD489V/Rif-31 | 32 | |||||

| S495F | 2 | Rif-51, -68 | 16-32 | |||

| TS495F/Rif-51 | 32 | |||||

| H499L | 1 | Rif-29 | 64 | |||

| TH499L/Rif-29 | 16 | |||||

| H499N | 11 | Rif-9, -14, -22, -28, -32, -37, -45, -49, -58, -60, -75 | 8-16 | |||

| TH499N/Rif-9 | 8 | |||||

| H499S | 2 | Rif-69, -71 | 64 | |||

| TH499S/Rif-69 | 16 | |||||

| H499Y | 12 | Rif-1, -12, -23, -40, -50, -53, -62, -64, -66, -70, -74, -76 | 128 | |||

| TH499Y/Rif12 | 32 | |||||

| L506S | 2 | Rif-57, -63 | 8-16 | |||

| TL506S/Rif-57 | 8 | |||||

| Q150R | V638G | 1 | Rif-52 | 4 | ||

| S481P, S485P | 1 | Rif-59 | 128 | |||

| TS481P, S485P/Rif-59 | 32 | |||||

| S481P, H499Y | 1 | Rif-2 | 512 | |||

| TS481P, H499Y/Rif-2 | 128 | |||||

| M488I, H499Y | 5 | Rif-34, -35, -36, -38, -39 | 512 | |||

| TM488I, H499Y/Rif-34 | 256 | |||||

| D489G, L506V | 3 | Rif-18, -19, -30 | 16-32 | |||

| TL506V/Rif-18 | 16 | |||||

| TD489G, L506V/Rif-18 | 16 | |||||

| D489N,R501H | 1 | Rif-7 | 32 | |||

| TD489N, R501H/Rif-7 | 16 | |||||

| D489N | P537S | 1 | Rif-17 | 16 | ||

| TD489N, P537S/Rif-17 | 16 | |||||

| H499Y | N547S | 1 | Rif-11 | 256 | ||

| TH499Y, N547S/Rif-11 | 64 | |||||

Transformant strains (T) are derivatives of strain R6 that carry the indicated mutations from the indicated donor isolates. For instance, TQ150R/Rif-42 carries the Q150R change of isolate Rif-42.

To establish the contribution of the mutations identified above to RIF resistance, genetic transformation experiments were performed. PCR products from the RIF-resistant isolates were able to transform the susceptible R6 strain (MIC, 0.015 μg/ml) to resistance at a high frequency (about 1 × 10−2), whereas PCR products from R6 transformed at frequencies 103-fold lower (about 2 × 10−5). Transformants containing single mutations had MICs equivalent to that of the corresponding isolate, with a one- or twofold dilution margin (Table 3). The Q150R change at cluster N conferred a MIC of 2 μg/ml (TQ150R/Rif-42), equivalent to the MIC of 4 to 8 μg/ml for the clinical isolates carrying the same mutation (Rif-42, -52, -61, and -67). Although Rif-52 carried the Q150R change plus the V638G change at cluster III, no RIF-resistant transformants with PCR products carrying V638G were obtained. Moreover, since the MIC of TQ150R/Rif-42 is equivalent to that of Rif-52, it could be assumed that V638G is not involved in RIF resistance. On the other hand, single mutations at cluster I conferred MICs of 4 to 32 μg/ml (Table 3). To determine the contribution of the double mutations to resistance, the MICs for transformants containing one or two mutations were compared (Table 3). These comparisons confirmed the contributions of S485P, M488I, and L506V to resistance: the MIC of TS481P, S485P/Rif-59 was eightfold higher than that of TS481P/Rif-59, and the MIC of TM488I, H499Y/Rif-34 was eight-fold higher than that of TH499Y/Rif-12. However, the N547S and D489G changes would not be involved in resistance, given that the MIC for TH499Y, N547S/Rif-11 was twofold higher than that for TH499Y/Rif-12 and the MIC for TD489G, L506V/Rif-18 was equal to that for TL506V/Rif-18. On the other hand, the contributions of D489N, R501H, and P537S to RIF resistance could not be discerned, since no transformants with those single changes were obtained (Table 3).

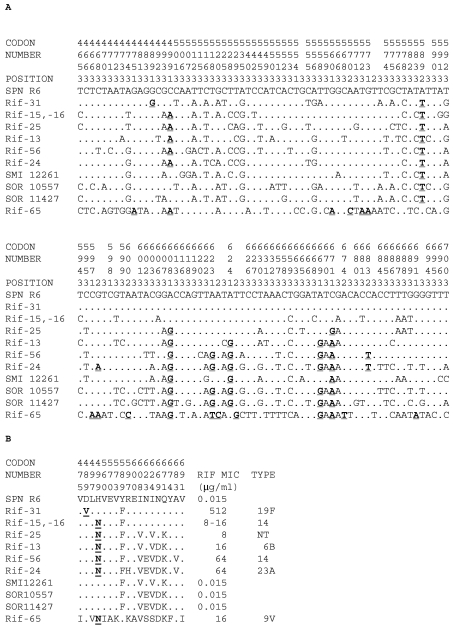

Furthermore, the deduced amino acid sequences of the eight RIF-resistant recombinant isolates contained several additional changes, besides the H499N and D489V changes involved in resistance (Fig. 3B). All recombinant isolates except Rif-65 shared the Y589F change present in Streptococcus mitis NCTC 12261, S. oralis NCTC 11427, and S. oralis ATCC 10557 RIF-susceptible isolates (Fig. 3B), indicating that this residue is not involved in resistance. Likewise, the I624V, Q671K, N623E, and N669D changes would not be implicated in resistance since they are also present in RIF-susceptible S. mitis and/or S. oralis strains. However, although it is not possible to assign the contribution of each residue to resistance, the comparison of the RIF MICs conferred by the D489V and H499N changes to the nonrecombinant pneumococcal isolates (Table 3) suggests that these mutations are indeed responsible for the RIF resistance phenotypes of the recombinant isolates.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide (A) and amino acid (B) sequence variations at the RpoB T464 to T700 region of RIF-resistant recombinant isolates. The nucleotides and amino acids present at each polymorphic site are shown in full for the R6 strain, but for the other isolates, only sites that differ from those of R6 are shown. Codon numbers are indicated vertically above the sequences. Positions 1, 2, and 3 refer to the first, second, and third nucleotides in the codon, respectively. Sense mutations and amino acid changes involved in RIF resistance are shown in boldface and underlined. SPN R6, S. pneumoniae R6; SMI 12261, S. mitis NCTC 12261; SOR 10557, S. oralis ATCC 10557; SOR 11427, S. oralis NCTC 11427.

Phylogeny of isolates with high levels of nucleotide sequence variations.

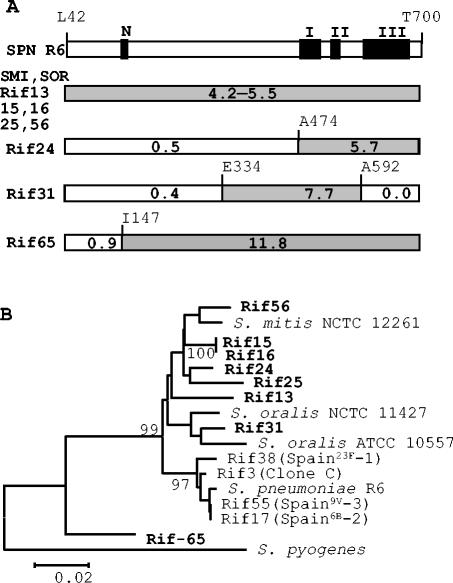

As pointed out above, a majority (86.9%) of the RIF-resistant isolates showed low-level nucleotide sequence variation (≤0.7%) at their Q464 to T700 rpoB sequences with respect to the sequence of strain R6. Similar intraspecific variations have been determined for atpC-atpA (<0.7%) and for the quinolone resistance-determining regions of parC, parE, gyrA, and gyrB (≤1%) (4). However, eight RIF-resistant isolates showed high levels of nucleotide sequence variation (2.0 to 10.9% in the Q464 to T700 fragment and 2.3 to 10.8 in the L42 to T700 fragment). The existence of S. pneumoniae RIF-resistant isolates with high levels of nucleotide sequence variations have been described previously (7, 15, 32). This variation was in accordance with the divergence found between S. pneumoniae and S. oralis for the amylomaltase gene (4 to 6%) (13) and between S. pneumoniae and viridans group streptococci for the parE gene (≥8.5%) (4). High levels of nucleotide sequence variations (Fig. 3) suggested that these isolates would have a mosaic structure in rpoB as a consequence of recombination with viridans group streptococci. To establish the mosaic structure, a 1,977-bp region (residues L42 to T700) was sequenced and compared with the sequence of R6. Five isolates (Rif-13, -15, -16, -25, and -56) showed a continuous block of divergence, suggesting that the recombination points are located outside the region analyzed (Fig. 4). Isolates Rif-24 and Rif-65 showed two blocks, whereas isolate Rif-31 showed three blocks. The blocks with divergence lower than 1% could represent the recombination sites.

FIG. 4.

The pneumococcal recombinant isolates interchanged parts of their rpoB genes with viridans group streptococci. (A) Mosaic structure of a 1,977-bp region (L42 to T700) of rpoB. The divergence of each block with respect to the strain R6 sequence is indicated. (B) Phylogenetic tree of a 357-bp region that includes RpoB residues A474 to A592 in which all isolates showed nucleotide sequence variations in the 4% to 9% range. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted with the MEGA program (version 2.1) by the neighbor-joining method. Only bootstrap confidence intervals exceeding 90% are shown.

To establish the origin of the gene donor to the Rif-65 isolate (the isolate showing the highest divergence with respect to the sequence of R6 strain, 10.8%), several WU-Blast2 analyses of the EMBL database were performed. The sequences more similar to the rpoB sequence of Rif-65 were chosen to perform a phylogenetic analysis. Since the block structure of the rpoB genes revealed a common variable region of 357 bp (A474 to A592) for the eight recombinant isolates (Fig. 4A), this fragment was used for the detection of different clusters within the isolates. All recombinant isolates except Rif-65 formed a monophyletic group that included S. pneumoniae strains and viridans group streptococcal strains (S. oralis and S. mitis) (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the donors in the horizontal transfer of rpoB genes to S. pneumoniae are the viridans group streptococci belonging to S. mitis or S. oralis species, as described for the penicillin- and fluoroquinolone-resistance determinants (10, 13). Three of these recombinant isolates belonged to the Spain14-5 and Spain6B-2 clones (Table 2), suggesting a possible dissemination of RIF resistance through these clones.

In conclusion, the incidence of RIF resistance among S. pneumoniae isolates is rare in Spain and was mainly related to HIV-infected patients and children with conjunctivitis, suggesting prior treatment with this drug. Although cross-transmission of RIF-resistant isolates was demonstrated among HIV-infected patients, the majority of RIF-resistant isolates were isolated from individual patients without temporal or geographical relationships. This resistance was acquired either by point mutations in the rpoB gene or by recombination with viridans group streptococci. Continuous surveillance of resistance to rifampin among invasive pneumococci is important, because in serious pneumococcal infections, a combination of rifampin and broad-spectrum cephalosporins or vancomycin is recommended.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa G03/103 from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria and by grant BIO2002-01398 from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología. We acknowledge the use of the pneumococcal MLST database, which is located at Imperial College London and which is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amsterdam, D. 1986. Susceptibility testing of antimicrobials in liquid media. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 2.Aubry-Damon, H., M. Galimand, G. Gerbaud, and P. Courvalin. 2002. rpoB mutation conferring rifampin resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1571-1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aubry-Damon, H., C. J. Soussy, and P. Courvalin. 1998. Characterization of mutations in the rpoB gene that confer rifampin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2590-2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsalobre, L., M. J. Ferrándiz, J. Liñares, F. Tubau, and A. G. de la Campa. 2003. Viridans group streptococci are donors in horizontal transfer of topoisomerase IV genes to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2072-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley, J. S., and W. M. Scheld. 1997. The challenge of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis: current antibiotic therapy in the 1990s. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, E. A., N. Korzheva, A. Mustaev, K. Murakami, S. Nair, A. Goldfarb, and S. A. Darst. 2001. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell 104:901-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, J. Y., C. P. Fung, F. Y. Chang, L. Y. Huang, J. C. Chang, and L. K. Siu. 2004. Mutations of rpoB gene in rifampicin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Taiwan. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:375-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffey, T., S. Berron, M. Daniels, M. García-Leoni, E. Cercenado, E. Bouza, A. Fenoll, and B. G. Spratt. 1996. Multiply antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from Spain hospitals (1988-1994): novel major clones of serotypes 14, 19F, and 15F. Microbiology 142:2747-2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruchaga, S., M. Pérez-Vázquez, F. Román, and J. Campos. 2003. Molecular basis of rifampicin resistance in Haemophilus influenzae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:1011-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Campa, A. G., L. Balsalobre, C. Ardanuy, A. Fenoll, E. Pérez-Trallero, J. Liñares, and the Spanish Pneumococcal Infection Study Network G03/103. 2004. Fluoroquinolone resistance in penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae clones, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1751-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dicuonzo, G., G. Gerardi, R. E. Gertz, F. D'Ambrosio, A. Goglio, G. Lorino, S. Recchia, A. Pantosti, and B. Beall. 2002. Genotypes of invasive pneumococcal isolates recently recovered from Italian patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3660-3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doern, G. V., K. P. Heilmann, H. K. Huynh, P. R. Rhomberg, S. L. Coffman, and A. B. Brueggemann. 2001. Antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States during 1999-2000, including a comparison of resistance rates since 1994-1995. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1721-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowson, C. G., A. Hutchinson, N. Woodford, A. P. Johnson, R. C. George, and B. G. Spratt. 1990. Penicillin-resistant viridans streptococci have obtained altered penicillin-binding protein genes from penicillin-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:5858-5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enright, M., and B. G. Spratt. 1998. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144:3049-3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enright, M., P. Zawadski, P. Pickerill, and C. G. Dowson. 1998. Molecular evolution of rifampicin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 4:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enright, M. C., A. Fenoll, D. Griffiths, and B. G. Spratt. 1999. The three major Spanish clones of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae are the most common clones recovered in recent cases of meningitis in Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3210-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenoll, A., I. Jado, D. Vicioso, A. Pérez, and J. Casal. 1998. Evolution of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes and antibiotic resistance in Spain: update (1990-1996). J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3447-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Arenzana, J. M., M. Montes, and E. Pérez-Trallero. 1994. Are rifampin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains a consequence of the increase in cases of tuberculosis? Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:360-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrera, L., S. Jiménez, A. Valverde, M. A. García-Aranda, and J. A. Sáez-Nieto. 2003. Molecular analysis of rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated in Spain (1996-2001). Description of new mutations in the rpoB gene and review of the literature. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 21:403-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs, M. R., D. Felmingham, P. C. Applelbaum, R. N. Grüneberg, and The Alexander Project Group. 2003. The Alexander Project 1998-2000: susceptibility of pathogens isolated from community-acquired respiratory tract infection to commonly used antimicrobial agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:229-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin, D. J., and Y. N. Zhou. 1996. Mutational analysis of structure-function relationship of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 273:300-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacks, S. A. 1966. Integration efficiency and genetic recombination in pneumococcal transformation. Genetics 53:207-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liñares, J., R. Pallarés, T. Alonso, J. L. Pérez, J. Ayats, F. Gudiol, P. F. Viladrich, and R. Martín,. 1992. Trends in antimicrobial resistance of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Bellvitge Hospital, Barcelona, Spain (1979-1990). Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liñares, J., F. Tubau, and M. A. Dominguez. 1999. Antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae in Spain: an overview in the 1990s. In A. Tomasz (ed.), Streptococcus pneumoniae. Molecular biology and mechanisms of disease-update for the 1990s. Mary Ann Liebert Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 25.Marchese, A., S. Mannelli, E. Tonoli, F. Gorlero, M. Toni, and G. C. Schito. 2001. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae circulating in Italy: results of the Italian Epidemiological Observatory Survey. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martínez-Lacasa, J., C. Cabellos, A. Martos, A. Fernández, F. Tubau, P. F. Viladrich, J. Liñares, and F. Gudiol. 2002. Experimental study of the efficacy of vancomycine, rifampicin and dexamethasone in the therapy of pneumococcal meningitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martín-Galiano, A. J., and A. G. de la Campa. 2003. High-efficiency generation of antibiotic-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae by PCR and transformation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1257-1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGee, L., L. McDougal, J. Zhou, B. G. Spratt, F. C. Tenover, R. George, R. Hakenbeck, W. Hryniewicz, J. C. Lefevre, A. Tomasz, and K. P. Klugman. 2001. Nomenclature of major antimicrobial-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae defined by the pneumococcal molecular epidemiology network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2565-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier, P. S., S. Utz, S. Aebi, and K. Mühlemann. 2003. Low-level resistance to rifampin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:863-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2004. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Fourteenth informational supplement. NCCLS document M100-S14. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 31.Nielsen, K., P. Hindersson, N. Hoiby, and J. M. Bangsborg. 2000. Sequencing of the rpoB gene in Legionella pneumophila and characterization of mutations associated with rifampin resistance in the legionellaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2679-2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padayachee, T., and K. P. Klugman. 1999. Molecular basis of rifampin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2361-2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paris, M. M., S. M. Hickey, M. I. Uscher, S. Shelton, K. D. Olsen, and G. H. McCracken,. 1994. Effect of dexamethasone on therapy of experimental penicillin- and cephalosporin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1320-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pérez-Trallero, E., J. M. Marimón, A. González, and L. Iglesias. 2003. Spain14-5 international multiresistant clone resistant to fluoroquinolones and other families of antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:715-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds, M. G. 2000. Compensatory evolution in rifampin-resistant Escherichia coli. Genetics 156:1471-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subramanian, D., J. A. T. Sandoe, V. Keer, and M. H. Wilcox. 2003. Rapid spread of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae among high-risk hospital inpatients and the role of molecular typing in outbreak confirmation. J. Hosp. Infect. 54:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tenover, F. C., R. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Tilburg, P. M. B., D. Bogaert, M. Sluijter, A. R. Jansz, R. de Groot, and P. W. M. Hermans. 2001. Emergence of rifampin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae as a result of antimicrobial therapy for penicillin-resistant strains. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:e93-e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wichelhaus, T. A., B. Böddinghaus, S. Besier, V. Schäfer, V. Brade, and A. Ludwig. 2002. Biological cost of rifampin from the perspective of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3381-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, G., E. A. Campbell, L. Minakhin, C. Ritcher, K. Severinov, and S. A. Darst. 1999. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase at 3.3 Å resolution. Cell 98:811-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]