Abstract

Fusarium oxysporum is a cross-kingdom pathogen that infects humans, animals, and plants. The primary concern regarding this genus revolves around its resistance profile to multiple classes of antifungals, particularly azoles. However, the resistance mechanism employed by Fusarium spp. is not fully understood, thus necessitating further studies to enhance our understanding and to guide future research towards identifying new drug targets. Here, we employed an untargeted proteomic approach to assess the differentially expressed proteins in a soil isolate of Fusarium oxysporum URM7401 cultivated in the presence of amphotericin B and fluconazole. In response to antifungals, URM7401 activated diverse interconnected pathways, such as proteins involved in oxidative stress response, proteolysis, and lipid metabolism. Efflux proteins, antioxidative enzymes and M35 metallopeptidase were highly expressed under amphotericin B exposure. Antioxidant proteins acting on toxic lipids, along with proteins involved in lipid metabolism, were expressed during fluconazole exposure. In summary, this work describes the protein profile of a resistant Fusarium oxysporum soil isolate exposed to medical antifungals, paving the way for further targeted research and discovering new drug targets.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-024-01417-8.

Keywords: Drug resistance, Antifungal, Stress response, Proteome, Efflux pumps

Introduction

The One Health concept has gained attention since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, primarily due to the excessive use of antibiotics during the pandemic, which has raised substantial concerns within the medical and scientific communities regarding the emergence of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms [1]. The Fusarium oxysporum species complex exemplifies the One Health concept because it acts as a cross-kingdom pathogen capable of infecting plants, animals, and humans [2]. In humans, Fusarium can cause non-lethal superficial mycoses and disseminated diseases, which are more common in patients with hematological disorders or a compromised immune system [3]. As a plant pathogen, F. oxysporum can infect a wide range of plant species [4]. Beyond its economic impact due to crop damage [5], Fusarium poses a health risk to humans through food contamination with mycotoxins [6].

Fusarium spp. are also resistant to antifungal agents. This genus exhibits intrinsic resistance to azoles, a class of antifungals that target lanosterol 14α-demethylase, a critical enzyme in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway [7]. Lanosterol 14α-demethylase removes the 14α-methyl group from lanosterol via oxidation. Polyenes, such as amphotericin B, target ergosterol, either by inducing pore formation in the fungal membrane, resulting in ion leakage and eventual cell death [8], or functioning as sponges sequestering ergosterol from the plasma membrane [9]. Although the precise mechanisms underlying the resistance of Fusarium spp. to azoles are not fully understood, they are likely associated with the CYP51 gene, which encodes the lanosterol 14α-demethylase enzyme with isoforms A, B, and C [10]. Resistance to azoles can result from CYP51 overexpression or amino acid alterations, leading to changes in drug targeting. Overexpression of efflux pumps, such as those in the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily and major facilitator superfamily (MFS), is another common mechanism of resistance to azoles [11].

Concern over antifungal resistance extends to the agricultural sector, as the use of azoles as fungicides in the field can lead to cross-resistance to clinical azoles [12]. This emphasizes the importance of studying the Fusarium genus and its resistance mechanisms to discover new drug targets [2, 3], highlighting the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches for studying fungal diseases, considering the interconnection of environment, plants, animals, and humans [2]. Although many advances in medicine, such as organ transplantation and chemotherapy, have contributed to an increase in human life expectancy, these medical interventions have led to the suppression of the immune system and increased susceptibility to opportunistic fungal infections. Rhodes et al. revealed that a drug-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strain causing human infection was acquired from the environment [13]. In 2022, the World Health Organization released a list of priority fungal pathogens, with 19 species of concern for human health. Among the listed fungi, Fusarium spp. are classified in the high-priority group due to their extreme antifungal resistance profile [14, 15]. This list underscores the need to recognize the threat posed by antifungal resistance to human health, and encourage global efforts to prevent antifungal resistance, enhance surveillance, and invest in mycological research and drug development [15].

Given the risks posed by Fusarium spp. resistance to both human and plant health, our study aimed to evaluate the resistance profile of a soil isolate of F. oxysporum and assess its proteomic response to antifungals commonly employed in human therapy, by identifying the differentially expressed proteins involved in antifungal resistance.

Materials and methods

Isolate

The F. oxysporum employed in this study is a soil isolate from Miguelópolis (São Paulo, Brazil) identified at Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, by the research group of Profª. Drª. Cristina Maria de Souza Motta and deposited in the fungal collection of the University of Recife Mycology (URM) under accession number URM7401.

Antifungal susceptibility testing

To assess the antifungal susceptibility of URM7401, we determined its minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) following the guidelines outlined in CLSI M38-A2 (2008). The antifungals utilized for testing included amphotericin B (range 0.031–16 µg/mL), itraconazole (range 0.031–16 µg/mL), and fluconazole (range 0.125–64 µg/mL). All antifungals were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The protocol was performed in 96-well microplates using the RPMI 1640 medium. The MIC represents the lowest concentration of antifungal agent capable of completely inhibiting visible fungal growth following 48 h of incubation at 30 °C. The result was evaluated by visual observation of fungal growth in the plate wells. The test was conducted in triplicate. MIC values ≥ 4 µg/mL were classified as a resistance profile for all three drugs tested [16].

Exposure of Fusarium oxysporum URM7401 to amphotericin B and fluconazole

Preculturing was conducted to obtain sufficient biomass for protein extraction. We used a chemically defined RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) buffered with 50 mM HEPES at pH 7.0. A conidial suspension of 5 × 105 CFU/mL was added to 50 mL medium. The flasks were incubated at 30 °C with agitation at 120 rpm for 72 h. After preculture, the mycelia were separated from the media by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 4 °C, 15 min). The supernatant was discarded, and the mycelia were transferred to flasks containing fresh medium supplemented with antifungal (2 µg/mL amphotericin B or 64 µg/mL fluconazole). In control cultures, mycelia were transferred to a new medium with DMSO. The flasks were incubated (30 °C, 120 rpm, 3 and 48 h) and mycelia were separated from the media by filtration and stored at -80 °C.

Cultivations were performed in triplicate. The samples were designated based on the type of cultivation (C- Control, A- amphotericin B, and F- fluconazole), duration of exposure (3 and 48 h), and corresponding replicates (1, 2, or 3). For example, C3R2 corresponds to replicate 2 of the control cultivation for 3 h.

Extraction and quantification of intracellular proteins and sample preparation

The mycelia were individually frozen in liquid nitrogen and pulverized using a mortar and pestle. Subsequently, 15 mL of lysis buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 4% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.1 M dithiothreitol (DTT) was added, and the samples were subjected to sonication (five cycles of 2 min on and 30 s off; power 90) using an ultrasonic cell disruptor (Unique DES500). The samples were centrifuged at 8000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 min, and the resulting supernatant was collected and stored at -80 °C.Intracellular proteins were quantified using the RC DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad®) following the manufacturer’s instructions. BSA was used as the standard for the analytical curve, with the BSA concentration ranging from 0 to 1.5 µg/µL and R2 = 0.98.

Approximately 20 µg of protein from each sample was loaded onto an SDS‒PAGE gel 12% and electrophoresed until the proteins migrated out of the stacking gel. The gels were stained with 0.1% Coomassie blue (R-250), and sections adjacent to the protein bands were excised.

Untargeted proteomics

The following procedures were conducted at the RPT02H/Carlos Chagas Institute Mass Spectrometry Facility, Fiocruz Paraná.

Destaining, reduction, alkylation, and enzymatic digestion of proteins

In-gel protein digestion was performed as described by Shevchenko et al. (2006). Coomassie-stained gels were destained with 25 mmol L-1 ammonium bicarbonate solution in 50% ethanol, dehydrated with absolute ethanol, and dried. Reduction was achieved with 10 mmol L-1 DTT in 50 mmol/L ABC at 56 °C. Alkylation utilized 55 mmol L-1 iodoacetamide in 50 mmol L-1 ABC. Gel slices were then immersed in 50 mmol L-1 ABC digestion buffer, dehydrated, and re-immersed twice until they became whitish and hardened. The samples were dried using a Speed Vac for 10 min. Trypsin digestion involved covering dried samples with 12.5 ng µL-1 trypsin in 50 mmol L-1 ABC, incubating at 4 °C for 20 min, removing excess trypsin, and incubated at 37 °C for 16–18 h [17].

Peptide extraction and purification

All the liquid was collected in clean tubes, and up to 400 µL of extraction solution (water, 3% TFA, 30% acetonitrile) was added (the tubes were agitated for 10 min at 25 °C and 800 rpm). The supernatant was collected and this step was repeated. The gel slices were covered with acetonitrile and agitated for 10 min at 25 °C (800 rpm). The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and this step was repeated. The supernatant was then dried in a speed vac to remove acetonitrile (up to 10–20% of its volume).

The peptides were purified using StageTips-C18 and subsequently diluted in an AD solution (0.1% formic acid, 5% DMSO, and 5% ACN) for LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC‒MS/MS

Analyses were performed using a Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 RSLC system coupled with an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer. The gradient consisted of phases A (0.1% formic acid) and B (0.1% formic acid in 95% acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 250 nL/min. It followed a linear gradient from 5 to 40% B over 120-min duration. The analytical column used was a 15-cm packed emitter with a 75-µm internal diameter containing C18 particles 3 μm in diameter. The ion source was configured with a voltage of 2300 V, and the ion transfer tube temperature was set to 175 °C. Mass spectrometry was conducted in positive mode, employing a master scan (MS1) with an Orbitrap detector, offering a resolution of 120,000 and 300–1500 m/z scanning range. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set to standard, and internal calibration was performed using EASY-IC™. The intensity threshold for MS2 was set at 2 × 104 and the dynamic exclusion duration was 60 s. In the data-dependent mode, there was a 2-s interval between the master scans. For MS2, the settings were as follows: activation type, higher-energy collision dissociation, detector type, Orbitrap, mass resolution of, 15,000; and AGC target set as the standard.

Mass spectrometry data analysis

The MS data were analyzed using MaxQuant software (version 2.0.3.0), following the methodology described by Cox et al. in 2014 [18]. Raw files were searched against the Fusarium oxysporum NRRL 32,931 proteome downloaded from UniProt (comprising 20,767 entries, version from November 2022) and a list of potential contaminants. The parameters included the use of trypsin for protein digestion, variable modifications, including oxidation (M) and acetylation (protein N-terminal), and a fixed modification of carbamidomethyl (C). Up to two missed cleavages were permitted. The peptides selected for quantification were defined as ‘razor’. Both the peptide mass tolerance and fragment mass tolerance were set to 20 ppm. The mass values were treated as monoisotopic and the significance threshold was set at 0.01.

Statistical and data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with p-values adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Proteins exhibiting a corrected p < 0.01 were considered significant, and therefore deemed to be differentially expressed. Data analysis and generation of proteomics-related graphs were performed using Python (3.11.3). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the scikit-learn 1.3.1 library [19]. Intersection analysis was conducted using the UpSetPlot (0.9.0) library [20]. Cluster analysis was conducted using the cluster map function of the seaborn (0.13.1) library [21].

For the Gene Ontology (GO) abundance analysis of the differentially expressed proteins, the log2fc (log2 fold change) for each treatment was calculated in relation to the controls. A cutoff of 1.5 was established to select upregulated (cutoff > 1.5) or downregulated (cutoff < -1.5) proteins. The GO terms related to the differentially expressed proteins were obtained from Fusarium oxysporum NRRL 32,931 proteome downloaded from UniProt (comprising 20,767 entries, version from November 2022). GO terms related to the selected proteins were counted for each treatment. The top 5 most abundant GO terms related to the cellular component, biological process, and molecular function were selected for graphical visualization. The bar graphs were produced using matplotlib (3.8.2) [22].

Results

Evaluation of URM7401 susceptibility to antifungals

In Fig. 1, we observe the result of the antifungal susceptibility testing. The URM7401 could grow in all concentrations of fluconazole and itraconazole tested. Only amphotericin B effectively inhibited the growth of URM7401 in concentrations ≥ 4 µg/mL. In this sense, the MIC for amphotericin B was 4 µg/mL. Conversely, both fluconazole and itraconazole exhibited MIC values exceeding 64 and 16 µg/mL, respectively. From this initial test we selected amphotericin B and fluconazole at concentrations of 2 and 64 µg/mL, respectively for fungal cultivation, as these represented the highest antifungal concentrations at which fungal growth was observed.

Fig. 1.

Susceptibility analysis of URM7401 to different concentrations of the antifungals amphotericin B, itraconazole and fluconazole. Concentrations tested: 0.031–16 µg/mL to amphotericin B and fluconazole and 0.125–64 µg/mL to fluconazole

Untargeted proteomics

Data visualization

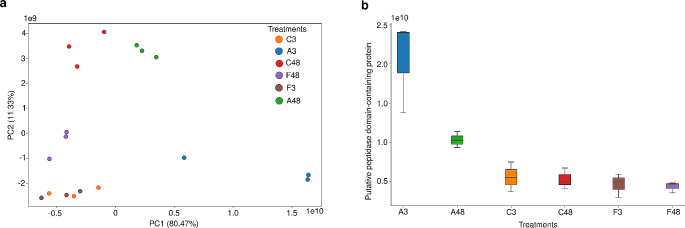

A PCA was performed to determine whether the growth conditions were suitable for generating distinct protein profiles in URM7401 and explore the data patterns. Figure 2a shows the PCA, which revealed that component 1 (PC1) accounted for 80,47% of the variance among the treatments (fungal growth conditions), whereas PC2 accounted for 11,33%. The PC1 explained the separation between 3 groups, A3, A48, and the other treatments. On the other hand, the PC2 explained the separation between other 3 groups, (A48, C48), F48 and (C3, F3, A3). Furthermore, about the 48-hour treatments (C48, A48, and F48), the F48 exhibited a higher difference from C48 and A48. Regarding the 3-hour treatments (C3, A3, and F3), the A3 presented a higher difference between C3 and F3. The sample replicates clustered together, indicating consistency in proteomic readings. Notably, for A3 treatment, in addition to being less similar to other treatments, one data point deviated from the cluster within the same group. This variability among the A3 replicates was also reflected in Pearson’s correlation values presented in Fig. S1 (Online Resource 1), in which treatment A3 exhibited a moderate correlation (0.5 to 0.69). In contrast, the other groups presented a strong (0.7 to 0.89) or very strong (0.9 to 1) correlation.

Fig. 2.

PCA and the corresponding component loadings. (a) PCA of URM7401 treatments A3, A48, C3, C48, F3 and F48. (b) PC1 loading: Putative peptidase domain-containing protein

From a biological perspective, the PCA results can be interpreted by examining the highest loading (Fig. 2b), which represents the contribution of each original variable to the PCA components (PC1 and PC2). Figure 2b illustrates PC1 loading, representing a putative peptidase from the M35 family with metallopeptidase activity. This peptidase exhibited high expression in the A3 treatment, moderate expression in the A48 treatment, and low expression in the other treatments.

GO functional analysis

We identified a total of 4308 proteins in the proteomic analysis. After the statistical analysis, we selected 1443 as differentially expressed (p-value < 0.01) by URM7401 in our culture conditions (we provided all proteins identified in the Online Resource 2). Of the 1443 differentially expressed proteins, 89 were upregulated in treatment A3, 103 were in A48, 66 were in F3, and 209 were in F48. Furthermore, 263 proteins were downregulated in treatment A3, 89 in A48, 76 in F3, and 73 in F48. In this sense, more proteins were downregulated for the 3-hour groups (A3 and F3). The opposite was observed for the 48-hour treatments (A48 and F48), with more upregulated proteins by URM 7401. Figures 3 and 4 show the abundance analysis determining the function of the upregulated and downregulated proteins, respectively, by URM7401 after different treatments, based on GO terms. The treatments were compared with controls. It is noticeable that many terms were repeated across various treatments and appeared both up- and downregulated. Proteins related to the cytoplasm, membrane, ATP binding, oxidoreductase activity and proteolysis were both upregulated and downregulated by URM7401. Some terms stood out because they appeared unique to each treatment. After A3 treatment, URM7401 overexpressed proteins related to cell surface (Fig. 3a). Conversely, after A48 treatment, the fungus overexpressed proteins related to ribose phosphate diphosphokinase complex and protoporphyrinogen IX biosynthetic process (Fig. 3b) and underexpressed proteins related to the nuclear pore (Fig. 4b). Following treatment with F3, URM7401 upregulated proteins related to pyridoxal phosphate binding (Fig. 3c) and downregulated the proteins related to phosphatidylinositol phosphate (Fig. 4c). Finally, after F48 treatment, the fungus overexpressed proteins related to the sterol biosynthetic process (Fig. 3d), and downregulated proteins related to nascent polypeptide associated complex and cellular anatomical entity (Fig. 4d). We also observed how antifungal exposure time modulated the expression of proteins induced by URM7401. Proteins related to the glutathione metabolic process and to transmembrane transporter activity were upregulated in the 3-hour groups, A3 (Fig. 3a) and F3 (Fig. 3c). Conversely, proteins related to ATP binding and RNA binding were upregulated only in the 48-hour groups, A48 (Fig. 3b) and F48 (Fig. 3d). Proteins related to cellular response to oxidative stress were upregulated in F48 (Fig. 3d) and downregulated in A3 (Fig. 4a). Proteins related to the chitin catabolic process were downregulated by URM7401 in exposure to fluconazole (Fig. 4c and d) and those related to chitinase activity were downregulated in F3 (Fig. 4c). We also observed that proteins related to protein transport were upregulated in F48 (Fig. 3d) and downregulated in exposure to amphotericin B (Fig. 4a and b). Conversely, proteins related to transmembrane transporter activity were downregulated only in F48 (Fig. 4d). Regarding quantity, Figs. 3 and 4 depicted that most proteins up or downregulated in all groups were related to the membrane.

Fig. 3.

GO abundance analysis of URM7401 up regulated proteins. (a) count of upregulated GO terms after A3 treatment; (b) count of upregulated GO terms after A48 treatment; (c) count of upregulated GO terms after F3 treatment; (d) count of upregulated GO terms after F48 treatment. Differentially expressed proteins were determined by ANOVA, with p value < 0.01; up regulated proteins were determined in comparison with the controls, C3 for treatments A3 and F3, and C48 for A48 and F48; log2fc cutoff: + 1.5

Fig. 4.

GO abundance analysis of URM7401 down regulated proteins. (a) count of down regulated GO terms after A3 treatment; (b) count of down regulated GO terms after A48 treatment; (c) count of down regulated GO terms after F3 treatment; (d) count of down regulated GO terms after A3 treatment. Differentially expressed proteins were determined by ANOVA, with p value < 0.01; down regulated proteins were determined in comparison with the controls (C3 for treatments A3 and F3, and C48 for A48 and F48); log2fc cutoff: − 1.5

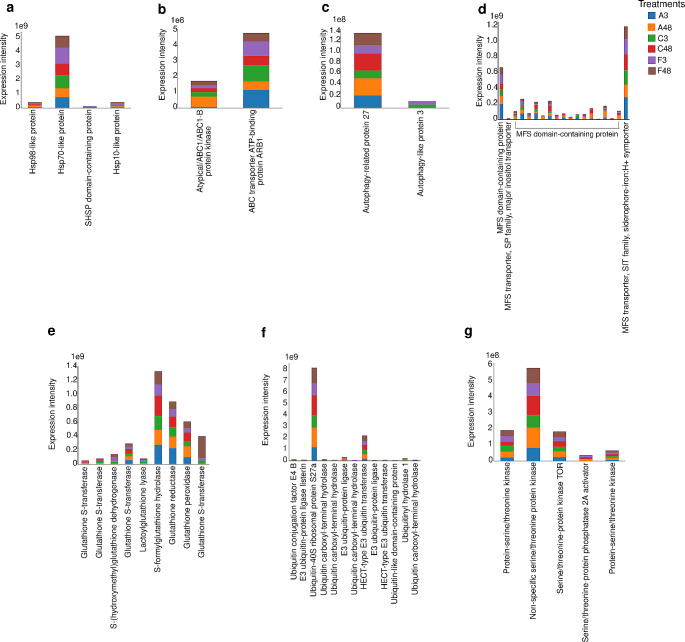

Differentially expressed proteins

Among the 1443 differentially expressed proteins, we searched for those previously described in the literature as being associated with fungal stress responses, such as efflux pumps and proteins related to oxidative stress responses [23, 24]. Among the proteins with transporter activity, 19 belonged to the MFS (Fig. 5d), whereas two were classified within the ABC transporter family (Fig. 5b). There were nine proteins associated with the glutathione system (Fig. 5e). Four heat shock proteins (Hsps) were expressed by URM7401 (Fig. 5a). We also found that two autophagy-related proteins were expressed by URM7401 (Fig. 5c). Additionally, we detected 13 ubiquitin-related proteins, including five ubiquitin ligases (E3s) and five deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, five serine/threonine proteins were expressed by URM7401 after culture (Fig. 5g).

Fig. 5.

Counts of selected stress-related proteins that exhibited differential expression (p value < 0.01) in URM7401 after treatment with amphotericin B, fluconazole and controls. (a) Heat shock proteins; (b) ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters; (c) Autophagy; (d) Major facilitator superfamily (MSF) transporters; (e) Glutathione; (f) Ubiquitin and (g) Serine-threonine

Following our initial examination of differentially expressed proteins related to stress responses in URM7401 cells, we focused on the top 56 differentially expressed proteins (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Top 56 differentially expressed proteins by URM7401 exposed to amphotericin B and fluconazole. (a) Heatmap of cluster analysis depicting the expression patterns of differentially expressed proteins. The heatmap represents the 56 proteins with the lowest p values from the ANOVA (p values < 0.01). (b) Intersection analysis of the treatments A3, A48, F3, F48 and the controls (C3 and C48)

Figure 6a shows the separation of protein profiles among the treatments based mainly on the incubation time (3–48 h), as indicated by cluster analysis. However, at each time point, clear differences were observed between the treatment and control groups. The proteins expressed in at least one of the 3-h incubation treatments were distinct from those in the 48-h incubation treatments. Some proteins were repeated, indicating the presence of isoforms.

As shown in Fig. 6a, some proteins with RNA-binding functions, such as elongation factor 3, nucleolin, and RRM domain-containing proteins, were mostly expressed after 3 h of treatment (A3 and F3) and in the control (C3). Autophagy-like protein 3 was highly expressed in F3 and C3. Proteins with transporter activity were also observed. In the A3 treatment, the only efflux protein that was highly expressed was MFS. In contrast, after A48 treatment, URM7401 exhibited significant upregulation of two ABC transporters and two MFS. After fluconazole treatment (F3 and F48), only one ABC and one MFS transporter were expressed at lower levels. The heat shock protein SSB1 (Hsp70) exhibited high expression in F3 and C3, moderate expression in A3, and low expression in F48 and C48.

The expression of oxidoreductase and catalase was high after A48 and C48 and moderate after A3. Moreover, eight proteins with oxidoreductase activity were identified. The NmrA domain-containing protein and iron transport multicopper oxidase FET3 were highly expressed after 3 h of treatment. In contrast, the Rieske domain-containing protein was only expressed after C48, whereas the FAD-binding PCMH-type domain-containing protein was highly expressed after 48 h of treatment. NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase was highly expressed after F48 treatment, along with eburicol 14-alpha-demethylase and C-22 sterol desaturase. Other proteins with antioxidant function are glutathione S-transferase and terpene cyclase/mutase family, both highly expressed after F48 treatment. Furthermore, we observed two proteins exclusively expressed in exposure to antifungals in 48-hour treatments (A48 and F48), the cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase and Zn(2)C6 fungal-type domain containing protein.

Figure 6b illustrates the relationships between the treatments with respect to protein expression (Fig. 6a). Each treatment is represented in a column and each intersection is depicted in a row. Of the 56 proteins analyzed, three were exclusively expressed after treatment with A3, two after C48, one after F48, two after F3, and four after C3. Notably, no proteins were exclusively expressed in URM7401 cells after treatment with A48. The largest intersection comprised 41% of the proteins expressed by URM7401 across all the treatments. The remaining intersections contained 1–3 proteins.

Discussion

Our goal in evaluating the antifungal susceptibility of the isolate URM7401 was to determine the antifungals and the corresponding concentrations we would select for fungal growth in liquid media. In this sense, we selected fluconazole and amphotericin B, one representative from azoles and one from polyenes. We did not select itraconazole due to poor solubility in DMSO. Regarding amphotericin B and fluconazole concentrations, we selected the highest concentrations that allowed fungal growth with the intention of observing the maximum response possible to the antifungals. Since concentrations ≥ 4 µg/mL of amphotericin B inhibited fungal growth, the sub-inhibitory concentration of 2 µg/mL was selected. Furthermore, URM7401 has grown in all concentrations of fluconazole tested, and because of that, we were able to select 64 µg/mL.

The ability of fungi to thrive in extreme environments such as glaciers and salterns is attributed to their stress response mechanisms [25]. Depending on the circumstances, fungi modulate their metabolism to adapt and survive through numerous signaling pathways [25, 26]. A beta-lactamase was highly expressed after A48, with lower expression after fluconazole exposure. Although this enzyme is responsible for degrading beta-lactam antibiotics in bacteria, in fungi it serves as a defense mechanism against xenobiotic compounds, which underscores the adaptability of fungi to survive in competitive environments such as soil [27]. Exposure to amphotericin B induced URM7401 to express a higher level of M35 metallopeptidase. In phytopathogenic fungi, the expression of M35 (deuterolisyn) and M36 (fungalysin) metallopeptidases is associated with virulence, because these enzymes protect fungi from the hydrolytic action of plant chitinases, facilitating plant infection [28, 29].

Proteolysis is important for cell cycle and homeostasis via protein digestion. This digestion can be either autophagic (by lysosomes) or ubiquitin-mediated via the ubiquitin‒proteasome system (UPS) [30, 31]. In fungi, ubiquitins are involved in diverse mechanisms, including stress response, virulence, and host adaptation [32]. Another important finding was that proteins related to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane were upregulated after fluconazole treatment. The endoplasmic reticulum is essential for proper protein folding and assembly, calcium homeostasis, lipid biosynthesis, and posttranslational modifications [33], and responds to stress stimuli, particularly misfolded protein accumulation, by activating the unfolded protein response (UPR) and altering lipid composition [34]. Evidence of UPR activation in the URM7401 culture was the expression of five serine-threonine protein kinases, as autophosphorylation of this protein and endoribonuclease leads to UPR activation [34]. Additionally, serine/threonine protein kinases contribute to the regulation of autophagy [35], which plays a substantial role in the cellular responses to ER and oxidative stress. In the entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana, autophagy is involved in the fungal infection cycle, stress response, development, and virulence [36].

Fungi employs various mechanisms to combat oxidative stress, including catalases, oxidoreductases, and the glutathione system. The high expression of catalase by URM7401 after A48 treatment may be attributed to the induction of oxidative stress by amphotericin B, which in turn triggers the production of catalase to reduce the ROS generated by amphotericin B action and auto oxidation [9]. Jukic et al. observed the increased expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase in amphotericin B-resistant Aspergillus terreus following treatment with amphotericin B [37]. Conversely, exposure to fluconazole for 48 h induced the expression of other antioxidant proteins, including terpene cyclase/mutase, which is involved in steroid biosynthesis and synthetized in lipid droplets, lipid storage organelles originating from the ER. These lipid droplets play a pivotal role in alleviating ER stress by reducing toxic lipids [34, 38], being essential for cellular stress responses, since their synthesis is triggered by energy and redox imbalances [39].

Moreover, the presence of hydrogen peroxide, induces the expression of certain efflux pumps, including ABC transporters and other multidrug resistance (MDR) efflux pumps [40]. Our results highlighted the significant role of MFS in the response of URM7401 to the tested antifungal agents. Additionally, the MFS plays a crucial role in the defense of Fusarium graminearum against the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON) [41]. This is inconsistent with Carolus et al. and suggests a possible correlation between amphotericin B tolerance and the expression of plasma membrane efflux pumps [9]. Despite the common role of efflux pumps in azole resistance mechanism [42], we did not observe high expression of these proteins upon URM7401 treatment with fluconazole. Another well-described stress response mechanism involves the expression of heat shock proteins [43]. Hsp70 plays a crucial role in the ER by supporting proper protein folding [44], and it was described to be related to amphotericin B resistance in A. terreus [45]. Furthermore, the Hsp90, which has been widely described as a resistance mechanism against azoles [42], was not identified in URM7401 proteome under our culture conditions.

We could hypothesize about URM7401 response and adaptation in exposure to amphotericin B and fluconazole from our results. The presence of amphotericin B and fluconazole caused oxidative stress on URM7401 cells, which leads to the increasing expression of Hsps, efflux pumps (like MFS and ABC), and proteins of the glutathione system to reduce the damage caused by antifungals induced oxidative stress on fungal cell. However, these proteins’ expression was insufficient to prevent damage to some proteins, leading to misfolding, which increased the expression of proteins related to autophagy, serine/threonine protein kinases, and ubiquitins. These act on misfolded protein signaling and degradation to alleviate ER stress [33].

In the present study, we evaluated the response of an environmental Fusarium isolate to antifungal agents for clinical use and observed a high level of resistance even without previous exposure. Considering the One Health concept and the rapidly emerging resistance of phytopathogens, it is clear that agriculture and medicine must use different antifungal classes [46]. This also raises questions about the effect of monocultures on depleting soil nutrients and reducing microbial diversity, which are important for controlling phytopathogen populations [47]. Novel targets for the development of antifungal drugs were proposed, such as peptidases, which are involved in the response of URM7401 to antifungal exposure and contribute to azole resistance and fungal virulence, suggesting that protease inhibitors could be promising alternatives [48].

This study represents the first description of the resistance profile of strain URM7401 and the second proteomic study of this isolate. Despite the significance of such an exploratory analysis in characterizing a strain’s profile, future research is needed to address certain limitations of the methodology in order to optimize the sample size. Additionally, other approaches may be employed to elucidate specific proteins’ pathways discussed herein and complement the obtained results.

Conclusion

URM7401 uses an elaborate arsenal to cope with antifungal exposure and modulates its response depending on the class of antifungal agents. Efflux proteins and M35 metallopeptidase played a substantial role in URM7401 tolerance to amphotericin B. Under fluconazole exposure many proteins involved in lipid biosynthesis and removal of toxic lipids were expressed. Additionally, antioxidant proteins and enzymes related to the ER were expressed under both fluconazole and amphotericin B exposure. Our study provides an initial description of the proteins and potential mechanisms involved in the antifungal resistance of URM7401, guiding further research to achieve a better understanding of these stress response mechanisms and new drug targets.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank FIOCRUZ for using its technological platform network. We also extend our gratitude to the FAPESP Finance Code number 2020/14426-3 and CAPES for their financial support.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization: [Isabela Victorino da Silva Amatto, Hamilton Cabral]; Methodology: [Isabela Victorino da Silva Amatto, Flávio Antônio de Oliveira Simões, Nathália Gonsales da Rosa Garzon, Hamilton Cabral]; Data Analysis: [Isabela Victorino da Silva Amatto, Ricardo Roberto da Silva]; Writing - original draft preparation: [Isabela Victorino da Silva Amatto]; Writing - review and editing: [Isabela Victorino da Silva Amatto, Camila Langer Marciano, Ricardo Roberto da Silva, Hamilton Cabral]; Supervision: [Hamilton Cabral]. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (CAPES; Finance Code 001).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Picot S, Beugnet F, Leboucher G, Bienvenu A-L (2022) Drug resistant parasites and fungi from a one-health perspective: a global concern that needs transdisciplinary stewardship programs. One Health 14:100368. 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100368 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sáenz V, Alvarez-Moreno C, Pape PL, Restrepo S, Guarro J, Ramírez AMC (2020) A one health perspective to recognize Fusarium as important in clinical practice. J Fungi 6:235. 10.3390/jof6040235 10.3390/jof6040235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Hatmi AMS, Meis JF, de Hoog GS (2016) Fusarium: Molecular Diversity and Intrinsic Drug Resistance. PLOS Pathog 12:e1005464. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005464 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Gao M, Gabriel DW, Liang W, Song L (2020) Secretome-Wide Analysis of Lysine Acetylation in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici provides novel insights into infection-related proteins. Front Microbiol 11:559440. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.559440 10.3389/fmicb.2020.559440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma M, Sengupta A, Ghosh R, Agarwal G, Tarafdar A, Nagavardhini A, Pande S, Varshney RK (2016) Genome wide transcriptome profiling of Fusarium oxysporum f sp. ciceris conidial germination reveals new insights into infection-related genes. Sci Rep 6:37353. 10.1038/srep37353 10.1038/srep37353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Diepeningen AD, Brankovics B, Iltes J, Van Der Lee TAJ, Waalwijk C (2015) Diagnosis of Fusarium infections: approaches to identification by the Clinical Mycology Laboratory. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 9:135–143. 10.1007/s12281-015-0225-2 10.1007/s12281-015-0225-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abastabar M, Al-Hatmi AMS, Vafaei Moghaddam M, De Hoog GS, Haghani I, Aghili SR, Shokohi T, Hedayati MT, Daie Ghazvini R, Kachuei R, Rezaei-Matehkolaei A, Makimura K, Meis JF, Badali H (2018) Potent activities of Luliconazole, Lanoconazole, and eight comparators against Molecularly Characterized Fusarium species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e00009–18. 10.1128/AAC.00009-18 10.1128/AAC.00009-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown NA, Goldman GH (2016) The contribution of aspergillus fumigatus stress responses to virulence and antifungal resistance. J Microbiol 54:243–253. 10.1007/s12275-016-5510-4 10.1007/s12275-016-5510-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carolus H, Pierson S, Lagrou K, Van Dijck P (2020) Amphotericin B and other Polyenes—Discovery, Clinical Use, Mode of Action and Drug Resistance. J Fungi 6:321. 10.3390/jof6040321 10.3390/jof6040321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlin DS, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Alastruey-Izquierdo A (2017) The global problem of antifungal resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect Dis 17:e383–e392. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30316-X 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30316-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermeulen P, Gruez A, Babin A-L, Frippiat J-P, Machouart M, Debourgogne A (2022) CYP51 mutations in the Fusarium Solani Species Complex: First Clue to understand the low susceptibility to Azoles of the Genus Fusarium. J Fungi 8:533. 10.3390/jof8050533 10.3390/jof8050533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herkert PF, Al-Hatmi AMS, De Oliveira Salvador GL, Muro MD, Pinheiro RL, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, De Hoog GS, Meis JF (2019) Molecular characterization and Antifungal susceptibility of clinical Fusarium species from Brazil. Front Microbiol 10:737. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00737 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes J, Abdolrasouli A, Dunne K, Sewell TR, Zhang Y, Ballard E, Brackin AP, Van Rhijn N, Chown H, Tsitsopoulou A, Posso RB, Chotirmall SH, McElvaney NG, Murphy PG, Talento AF, Renwick J, Dyer PS, Szekely A, Bowyer P, Bromley MJ, Johnson EM, Lewis White P, Warris A, Barton RC, Schelenz S, Rogers TR, Armstrong-James D, Fisher MC (2022) Population genomics confirms acquisition of drug-resistant aspergillus fumigatus infection by humans from the environment. Nat Microbiol 7:663–674. 10.1038/s41564-022-01091-2 10.1038/s41564-022-01091-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization (2022) WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research development and public health action. World Health Organ.. www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241. Accessed 15 October 2023

- 15.Fisher MC, Denning DW (2023) The WHO fungal priority pathogens list as a game-changer. Nat Rev Microbiol 21:211–212. 10.1038/s41579-023-00861-x 10.1038/s41579-023-00861-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2008) M38-A2: Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi; Approved Standard—Second Edition. Wayne, PA

- 17.Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havli J, Olsen JV, Mann M (2006) In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat Protoc 1:2856–2860. 10.1038/nprot.2006.468 10.1038/nprot.2006.468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox J, Hein MY, Luber CA, Paron I, Nagaraj N, Mann M (2014) Accurate Proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol Cell Proteom 13:2513–2526. 10.1074/mcp.M113.031591 10.1074/mcp.M113.031591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, Blondel M, Prettenhofer P, Weiss R, Dubourg V, Vanderplas J, Passos A, Cournapeau D (2011) Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. Mach Learn PYTHON 2825–2830

- 20.Lex A, Gehlenborg N, Strobelt H, Vuillemot R, Pfister H (2014) UpSet: visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 20:1983–1992. 10.1109/TVCG.2014.2346248 10.1109/TVCG.2014.2346248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waskom M (2021) Seaborn: statistical data visualization. J Open Source Softw 6:3021. 10.21105/joss.03021 10.21105/joss.03021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter JD (2007) Matplotlib: a 2D Graphics Environment. Comput Sci Eng 9:90–95. 10.1109/MCSE.2007.55 10.1109/MCSE.2007.55 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rangel DEN, Alder-Rangel A, Dadachova E, Finlay RD, Kupiec M, Dijksterhuis J, Braga GUL, Corrochano LM, Hallsworth JE (2015) Fungal stress biology: a preface to the fungal stress responses special edition. Curr Genet 61:231–238. 10.1007/s00294-015-0500-3 10.1007/s00294-015-0500-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowen LE, Sanglard D, Howard SJ, Rogers PD, Perlin DS (2015) Mechanisms of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5:a019752. 10.1101/cshperspect.a019752 10.1101/cshperspect.a019752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroll K, Pähtz V, Kniemeyer O (2014) Elucidating the fungal stress response by proteomics. J Proteom 97:151–163. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.06.001 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stępień Ł, Lalak-Kańczugowska J (2021) Signaling pathways involved in virulence and stress response of plant-pathogenic Fusarium species. Fungal Biol Rev 35:27–39. 10.1016/j.fbr.2020.12.001 10.1016/j.fbr.2020.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao M, Glenn AE, Blacutt AA, Gold SE (2017) Fungal lactamases: their occurrence and function. Front Microbiol 8:1775. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01775 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jashni MK, Dols IHM, Iida Y, Boeren S, Beenen HG, Mehrabi R, Collemare J, De Wit PJGM (2015) Synergistic action of a metalloprotease and a serine protease from Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici cleaves chitin-binding Tomato chitinases, reduces their antifungal activity, and enhances fungal virulence. Mol Plant-Microbe Interactions® 28:996–1008. 10.1094/MPMI-04-15-0074-R 10.1094/MPMI-04-15-0074-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Huang H, Wu B, Xie J, Viljoen A, Wang W, Mostert D, Xie Y, Fu G, Xiang D, Lyu S, Liu S, Li C (2021) The M35 metalloprotease effector FocM35_1 is required for full virulence of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4. Pathogens 10:670. 10.3390/pathogens10060670 10.3390/pathogens10060670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciechanover A (2005) Proteolysis: from the lysosome to ubiquitin and the proteasome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:79–87. 10.1038/nrm1552 10.1038/nrm1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minina EA, Moschou PN, Bozhkov PV (2017) Limited and digestive proteolysis: crosstalk between evolutionary conserved pathways. New Phytol 215:958–964. 10.1111/nph.14627 10.1111/nph.14627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao C, Xue C (2021) More than just cleaning: ubiquitin-mediated Proteolysis in Fungal Pathogenesis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11:774613. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.774613 10.3389/fcimb.2021.774613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han J, Kaufman RJ (2016) The role of ER stress in lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. J Lipid Res 57:1329–1338. 10.1194/jlr.R067595 10.1194/jlr.R067595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Revie NM, Iyer KR, Maxson ME, Zhang J, Yan S, Fernandes CM, Meyer KJ, Chen X, Skulska I, Fogal M, Sanchez H, Hossain S, Li S, Yashiroda Y, Hirano H, Yoshida M, Osada H, Boone C, Shapiro RS, Andes DR, Wright GD, Nodwell JR, Del Poeta M, Burke MD, Whitesell L, Robbins N, Cowen LE (2022) Targeting fungal membrane homeostasis with imidazopyrazoindoles impairs azole resistance and biofilm formation. Nat Commun 13:3634. 10.1038/s41467-022-31308-1 10.1038/s41467-022-31308-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li G, Gong Z, Dulal N, Marroquin-Guzman M, Rocha RO, Richter M, Wilson RA (2023) A protein kinase coordinates cycles of autophagy and glutaminolysis in invasive hyphae of the fungus Magnaporthe oryzae within rice cells. Nat Commun 14:4146. 10.1038/s41467-023-39880-w 10.1038/s41467-023-39880-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou J, Wang J-J, Lin H-Y, Feng M-G, Ying S-H (2020) Roles of autophagy-related genes in conidiogenesis and blastospore formation, virulence, and stress response of Beauveria Bassiana. Fungal Biol 124:1052–1057. 10.1016/j.funbio.2020.10.002 10.1016/j.funbio.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jukic E, Blatzer M, Posch W, Steger M, Binder U, Lass-Flörl C, Wilflingseder D (2017) Oxidative stress response Tips the Balance in Aspergillus Terreus Amphotericin B Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00670–e00617. 10.1128/AAC.00670-17 10.1128/AAC.00670-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olzmann JA, Carvalho P (2019) Dynamics and functions of lipid droplets. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20:137–155. 10.1038/s41580-018-0085-z 10.1038/s41580-018-0085-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarc E, Petan T (2019) Lipid Droplets and the Management of Cellular Stress [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Yaakoub H, Mina S, Calenda A, Bouchara J-P, Papon N (2022) Oxidative stress response pathways in fungi. Cell Mol Life Sci 79:333. 10.1007/s00018-022-04353-8 10.1007/s00018-022-04353-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Q, Chen D, Wu M, Zhu J, Jiang C, Xu J-R, Liu H (2018) MFS transporters and GABA Metabolism are involved in the Self-Defense against DON in Fusarium Graminearum. Front Plant Sci 9:438. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00438 10.3389/fpls.2018.00438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee Y, Robbins N, Cowen LE (2023) Molecular mechanisms governing antifungal drug resistance. Npj Antimicrob Resist 1:5. 10.1038/s44259-023-00007-2 10.1038/s44259-023-00007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen L, Geng X, Ma Y, Zhao J, Chen W, Xing X, Shi Y, Sun B, Li H (2019) The ER Lumenal Hsp70 protein FpLhs1 is important for conidiation and plant infection in Fusarium pseudograminearum. Front Microbiol 10:1401. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01401 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lv F, Xu Y, Gabriel DW, Wang X, Zhang N, Liang W (2022) Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals important roles of the Acetylation of ER-Resident Molecular chaperones for Conidiation in Fusarium oxysporum. Mol Cell Proteom 21:100231. 10.1016/j.mcpro.2022.100231 10.1016/j.mcpro.2022.100231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blatzer M, Blum G, Jukic E, Posch W, Gruber P, Nagl M, Binder U, Maurer E, Sarg B, Lindner H, Lass-Flörl C, Wilflingseder D (2015) Blocking Hsp70 enhances the efficiency of amphotericin B treatment against resistant aspergillus terreus strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3778–3788. 10.1128/AAC.05164-14 10.1128/AAC.05164-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher MC, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Berman J, Bicanic T, Bignell EM, Bowyer P, Bromley M, Brüggemann R, Garber G, Cornely OA, Gurr SJ, Harrison TS, Kuijper E, Rhodes J, Sheppard DC, Warris A, White PL, Xu J, Zwaan B, Verweij PE (2022) Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:557–571. 10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1 10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abán CL, Verdenelli R, Gil SV, Huidobro DJ, Meriles JM, Brandan CP (2021) Service crops improve a degraded monoculture system by changing common bean rhizospheric soil microbiota and reducing soil-borne fungal diseases. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 97:fiaa258. 10.1093/femsec/fiaa258 10.1093/femsec/fiaa258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gutierrez-Gongora D, Geddes-McAlister J (2022) Peptidases: promising antifungal targets of the human fungal pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. FACETS 7:319–342. 10.1139/facets-2021-0157 10.1139/facets-2021-0157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].