Abstract

This study focuses on Bangladeshi university entrance test-taking students mental health problems and explores the geographical distribution of these problems using GIS technique. A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 1523 university entrance test-taking students. Data were collected on participants' socio-demographic characteristics, COVID-19-related factors, admission tests, depression, and anxiety. Chi-square tests and logistic regression were performed using SPSS software. GIS mapping was used to visualize the distribution of mental health problems across districts using ArcGIS. The study found that the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety among university entrance examinees were 53.8% and 33.2%, respectively. Males exhibited higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to females, while repeat test-taking students were more susceptible to these mental health issues compared to first-time test-takers. Factors such as urban residence, personal/familial COVID-19 infections, and COVID-19 deaths in close relationships were associated with increased mental health problems. District-based distribution showed no significant variation in depression, but anxiety varied significantly. Post-hoc GIS analysis revealed variations in the distribution of depression and anxiety among males, as well as variations in anxiety distribution based on student status across districts. This study emphasizes the high prevalence of depression and anxiety among university entrance examinees, emphasizing the importance of addressing mental health risks in this population. It also suggests the need for reforms in the university entrance test-taking system to reduce psychological problems and advocates for a more inclusive approach to student admissions to alleviate mental health burdens.

Keywords: Academic achievement, Depression, Anxiety, Prevalence and risk factors, University admission test, Bangladeshi students

Subject terms: Psychology, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

Mental health problems have become a growing concern worldwide, impacting the quality of life and work productivity. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 970 million people globally live with at least one mental disorder, with depression and anxiety being the most reported conditions1. Adolescents aged 10–19 are particularly affected, with an estimated 14% experiencing unrecognized and untreated mental health problems2. This period of transition from childhood to adulthood can exacerbate mental health issues due to the physiological changes that occur3.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted mental health, particularly among adolescent students. Research has shown that rates of depression and anxiety have significantly increased during the pandemic, with 27.6% and 25.6% increments in depression and anxiety disorders reported4. In Bangladesh, a recent meta-analysis of the studies conducted during the pandemic found that 47% of the population experienced both depression and anxiety during the pandemic, with students being more affected than the general population5. Before the pandemic, the rate was 30.5% and 16.4% for depression and anxiety in Bangladeshi adolescents6, and it appeared to be as high as 59.16% and 53.99% among university students7. In another Bangladeshi systematic review of mental health problems among students in general, 46.92% to 82.4% and 26.6% to 96.82% rates of mild to severe symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectively, were reported by Al Mamun et al.8. Similar findings were reported in other countries; for instance, a Chinese study found that the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms was 43.7% and 37.4% among high school students during the COVID-19 outbreak9. Overall, a meta-analysis suggested that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in adolescents aged 13–18 during the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly higher compared to other age groups, with 34.4% and 29.1% vs children aged ≤ 12 years 11.8% and 15.7% respectively10. Therefore, mental health problems are anticipated to be higher after the post-pandemic era than before the COVID-19 pandemic among students in Bangladesh.

On 8 March 2020, Bangladesh recorded its first COVID-19 case11 leading to the closure of educational institutions due to the virus's rapid spread. This forced the implementation of a new schooling method, which posed significant challenges for many students, including difficulty comprehending study materials, technical issues, lack of interest in attending classes, and limited access to online educational resources11,12. Consequently, several studies have been conducted to measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ mental health8. For example, a previous study among 874 university students reported that 40% had moderate to severe anxiety, and 72% had depressive symptoms13. Another study among 601 high school, medical college, and university students reported that 43.3% suffered from depression, and 32.6% had anxiety problems14. In addition, lower monthly family income, urban residence, family size, being smokers, not performing physical exercise, dissatisfaction with sleep, and dissatisfaction with academic studies were identified as the escalators of mental health problems among students8.

However, in Bangladesh, students must pass the Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSC) or equivalent exams before being eligible to take the university entrance test. Since the university entrance test is a highly competitive exam and is a pathway to higher study, students might suffer from psychological problems. Notably, academic performance, pressure to succeed, and post-graduation plans increased the risk of depression and anxiety among students15. Considering the situation, a previous study before the COVID-19 pandemic was conducted by Mamun and colleagues and found that nearly half of the university admission test-takers experienced depression (47.9%), while 28.9% experienced anxiety16. However, as the pandemic has brought about significant changes in the education system, resulting in increased mental health problems and uncertainty for students, it is anticipated that there will be an increased prevalence of mental health problems among university entrance test takers. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the prevalence of depression and anxiety among these students after the COVID-19 pandemic's impact. In addition, the spatial distribution of mental health problems was also presented using Geographical Information System (GIS) techniques, which adds new dimensions in visualizing the data. By investigating the pandemic's impact on these students' mental health, interventions can be designed to address the mental health needs of university entrance test takers in Bangladesh, which could ultimately improve their academic performance and overall well-being.

Methods

Study participants and procedure

This cross-sectional study was undertaken within a specific time frame between September 4th and 11th, 2022. The participants of this study were university students who were undergoing the process of taking an entrance exam at Jahangirnagar University in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Those who expressed an interest in participating in the study and were present in the university residence halls during the admission test period were included in the research. To collect the data, a self-administered survey was utilized, with a non-probability sampling technique being employed. Before the data collection process, all participants were thoroughly briefed about the terminology used within the survey questionnaire. The study included 1574 students, and upon the removal of incomplete questionnaires, 1523 data were deemed suitable for analysis. Notably, the survey was conducted using an English version questionnaire, and since all the participants were prospective university students, they did not have any difficulty understanding the English questionnaire.

Measures

Sociodemographic factors

The survey collected socio-demographic information from the participants, including but not limited to gender, permanent residence (distinguishing between urban and rural areas), family type, monthly family income, religion, smoking status, and substance use status. The participant's socioeconomic status (Poor = income was less than 15,000 Bangladeshi Taka [BDT]; middle-class = income ranged between 15,000 and 30,000 BDT; and high class = income was more than 30,000 BDT) was determined based on their monthly family income.

COVID-19-related variables

Participants were asked to divulge whether they had previously been contacted with the COVID-19 virus. Subsequently, information related to their family members or friends infected or died due to COVID-19 infection was also collected. All the questions were responded to in a yes/no manner.

Admission-related variables

Data about the test-taking status of the participants, namely whether they were first-time or repeat test takers, as well as their previous educational background in high school and the various dimensions thereof, alongside their public exams GPA (Grade Point Average), was gathered. Additionally, the participants were inquired about their preparation for the examination, including whether they sought the aid of tutors or coaching facilities and their performance on practice exams. In addition, they were also asked about their monthly expenditure during the admission test preparation and their preferred institution of admission.

Patient Health Questionnaire

The depression status of participants in this study was assessed utilizing the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)17. The PHQ-9 is composed of 9 items, and participants were asked to respond to them using a four-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half of the days, and 3 = nearly every day), reflecting their experiences over the past two weeks. The scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depression. A cut-off score of ≥ 10 was employed to identify the presence of depression among participants17. The internal consistency of the PHQ-9 was measured by Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.76) in the present study.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

This study employed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale to assess anxiety18. The GAD-7 consists of 7 items that are responded to using a four-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half of the days, and 3 = nearly every day), reflecting the participant's experiences over the past two weeks. The scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater severity of anxiety. A cut-off score of ≥ 10 was utilized to identify the presence of anxiety among participants18. The internal consistency of the GAD-7 was measured by Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.83) in the present study.

Ethical considerations

The Helsinki Declaration of 2013 was conscientiously adhered to ensure that the human participants were treated with the utmost care and respect. Additionally, the research protocol was thoroughly scrutinized and approved by the CHINTA Research Bangladesh review board. Before requesting the participants to enroll in the study, a comprehensive briefing session was held to inform them about the study's objectives, and the right to participate or withdraw at any point, among other relevant matters. Finally, a written informed consent form was obtained from each participant to affirm their willingness to participate in the survey.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2019 was utilized to input and cleanse the data, while the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25 was employed for statistical analysis. The study used descriptive (i.e., frequency and percentages) and inferential statistics (i.e., chi-square and logistic regression). The chi-square test was conducted to ascertain the association between depression and anxiety and the variables under study. Binary logistic regression was performed to extract the associated factors of depression and anxiety. The results from binary logistic regression were presented as the odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval. ArcGIS 10.8 was used for spatial analysis across districts in terms of depression and anxiety. The shape file for the GIS data is available at http://diva-gis.org/. All statistical tests were considered significant at p < 0.05, with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Description of the study participants

The study involved 1523 participants, predominantly male (76.8%, n = 1169) and living in rural areas (74.9%). Religion-wise, most participants were Muslim (87.1%) and belonged to nuclear families (76.2%). The percentage of participants who reported smoking was 10%, while the rate of those who reported drug use was 4%. Regarding COVID-19-related information, 8.4% of participants reported being infected with the virus, while 18.3% and 9.6% reported their family members or friends being infected and dying due to the virus, respectively. Additionally, 71.5% of the participants were first-time test takers, and 73.1% took professional help to prepare for their tests (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the study variables by gender and test-taking student status.

| Variables | Total sample | Gender | Student status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n; (%) | Male; n (%) | Female, n (%) | p-value | Fresher test-taker; n (%) | Repeat test-taker; n (%) | p-value | |

| Socio-demographic variables | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 354; 23.2% | – | – | – | 263; 24.2% | 91; 21% | 0.184 |

| Male | 1169; 76.8% | – | – | 826; 75.8% | 343; 79% | ||

| Permanent residence | |||||||

| Rural | 1127; 74.9% | 843; 72.9% | 284; 81.6% | 0.001 | 824; 76.7% | 303; 70.5% | 0.011 |

| Urban | 377; 25.1% | 313; 27.1% | 64; 18.4% | 250; 23.3% | 127; 29.5% | ||

| Religion | |||||||

| Muslim | 1298; 87.1% | 1005; 86.9% | 293; 87.7% | 0.705 | 937; 88% | 361; 84.9% | 0.114 |

| Others | 192; 12.9% | 151; 13.1% | 41; 12.3% | 128; 12% | 64; 15.1% | ||

| Family type | |||||||

| Nuclear | 1115; 76.2% | 860; 75.4% | 255; 78.9% | 0.191 | 808; 77.5% | 307; 72.9% | 0.060 |

| Joint | 348; 23.8% | 280; 24.6% | 68; 21.1% | 234; 22.5% | 114; 27.1% | ||

| Monthly income (BDT) | |||||||

| < 15,000 | 375; 36.5% | 307; 35% | 68; 45.3% | 0.041 | 266; 37.8% | 109; 33.5% | 0.214 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 383; 37.3% | 332; 37.8% | 51; 34% | 263; 37.4% | 120; 36.9% | ||

| > 30,000 | 270; 26.3% | 239; 27.2% | 31; 20.7% | 174; 24.8% | 96; 29.5% | ||

| Cigarette smoking status | |||||||

| Yes | 152; 10.3% | 101; 8.7% | 51; 15.9% | < 0.001 | 97; 9.2% | 55; 12.9% | 0.037 |

| No | 1328; 89.7% | 1059; 91.3% | 269; 84.1% | 955; 90.8% | 373; 87.1% | ||

| Drug usage status | |||||||

| Yes | 59; 4% | 49; 4.2% | 10; 3.1% | 0.369 | 40; 3.8% | 19; 4.5% | 0.535 |

| No | 1422; 96% | 1111; 95.8% | 311; 96.9% | 1017; 96.2% | 405; 95.5% | ||

| COVID-19 related information | |||||||

| Personal COVID-19 infection | |||||||

| Yes | 126; 8.4% | 104; 9% | 22; 6.5% | 0.153 | 88; 8.2% | 38; 8.9% | 0.651 |

| No | 1373; 91.6% | 1057; 91% | 316; 93.5% | 985; 91.8% | 388; 91.1% | ||

| Family members/friend’s COVID-19 infection | |||||||

| Yes | 275; 18.3% | 244; 21% | 31; 9.2% | < 0.001 | 193; 18% | 82; 19.2% | 0.569 |

| No | 1224; 81.7% | 917; 79% | 307; 90.8% | 880; 82% | 344; 80.8% | ||

| Family members/friend’s COVID-19 death | |||||||

| Yes | 144; 9.6% | 114; 9.8% | 30; 8.7% | 0.546 | 92; 8.5% | 52; 12.1% | 0.033 |

| No | 1362; 90.4% | 1048; 90.2% | 314; 91.3% | 985; 91.5% | 377; 87.9% | ||

| Admission-related variables | |||||||

| Appearance in the admission test | |||||||

| First timer | 1089; 71.5% | 826; 70.7% | 263; 74.3% | 0.184 | – | – | – |

| Repeat test-takers | 434; 28.5% | 343; 29.3% | 91; 25.7% | – | |||

| Secondary School Certificate (SSC) grade point average | |||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 300; 22.7% | 258; 23.1% | 42; 20.5% | 0.660 | 219; 23.7% | 81; 20.5% | 0.017 |

| Moderate | 481; 36.4% | 402; 36.1% | 79; 38.5% | 351; 38% | 130; 32.8% | ||

| High (5) | 539; 40.8% | 455; 40.8% | 84; 41% | 354; 38.3% | 185; 46.7% | ||

| Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) grade point average | |||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 146; 11.1% | 125; 11.2% | 21; 10.3% | 0.678 | 91; 9.9% | 55; 13.9% | 0.014 |

| Moderate | 383; 29.1% | 328; 29.5% | 55; 27.1% | 257; 27.9% | 126; 31.9% | ||

| High (5) | 786; 59.8% | 659; 59.3% | 127; 62.6% | 572; 62.2% | 214; 54.2% | ||

| Coached by professional coaching centers | |||||||

| No | 381; 26.9% | 304; 27% | 77; 26.4% | 0.823 | 195; 19.4% | 186; 45.4% | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 1036; 73.1% | 821; 73% | 215; 73.6% | 812; 80.6% | 224; 54.6% | ||

| Desired institute/department for admission | |||||||

| Varsity | 1100; 76.4% | 860; 75.2% | 240; 81.1% | 0.063 | 801; 78.3% | 299; 71.9% | < 0.001 |

| Medical | 217; 15.1% | 179; 15.7% | 38; 12.8% | 146; 14.3% | 71; 17.1% | ||

| Engineering | 89; 6.2% | 79; 6.9% | 10; 3.4% | 64; 6.3% | 25; 6% | ||

| Agriculture | 33; 2.3% | 25; 2.2% | 8; 2.7% | 12; 1.2% | 21; 5% | ||

| Satisfied with previous mock tests | |||||||

| Yes | 508; 37.5% | 406; 37.2% | 102; 38.6% | 0.661 | 365; 37.6% | 143; 37.2% | 0.915 |

| No | 848; 62.5% | 686; 62.8% | 162; 61.4% | 607; 62.4% | 241; 62.8% | ||

| Average monthly expenditure (BDT) | |||||||

| < 5000 | 203; 19.9% | 165; 19.2% | 38; 23.8% | 0.261 | 135; 18.9% | 68; 22.3% | 0.270 |

| 5000–10,000 | 601; 58.9% | 507; 58.9% | 94; 58.8% | 421; 58.8% | 180; 59% | ||

| > 10,000 | 217; 21.3% | 189; 22% | 28; 17.5% | 160; 22.3% | 57; 18.7% | ||

| Educational background | |||||||

| Science | 886; 58.6% | 698; 60% | 188; 54.3% | 0.179 | 601; 55.6% | 285; 66.3% | < 0.001 |

| Arts | 516; 34.1% | 385; 33% | 131; 37.9% | 405; 37.5% | 111; 25.8% | ||

| Commerce | 109; 7.2% | 82; 7% | 27; 7.8% | 75; 6.9% | 34; 7.9% | ||

| Mental health problems | |||||||

| Depression | |||||||

| No | 704; 46.2% | 502; 42.9% | 202; 57.1% | < 0.001 | 526; 48.3% | 178; 41% | 0.010 |

| Yes | 819; 53.8% | 667; 57.1% | 152; 42.9% | 563; 51.7% | 256; 59% | ||

| Anxiety | |||||||

| No | 1018;66.8% | 757; 64.8% | 261; 73.7% | 0.002 | 759; 69.7% | 259; 59.7% | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 505; 33.2% | 412; 35.2% | 93; 26.3% | 330; 30.3% | 175; 40.3% | ||

The overall prevalence of depression and anxiety among the participants was 53.8% and 33.2%, respectively. In terms of gender-based mental health suffering, 57.1% and 35.2% of males significantly suffered from depression and anxiety, respectively, whereas it was 42.9% and 26.3% of females. With respect to student status, repeat test-taking students were significantly more likely to suffer from depression (59.0% vs. 51.7%) and anxiety (40.3% vs. 30.3%) (Table 1).

Association between depression and the study variables

In terms of the total sample, the female gender showed a significantly higher rate of depression suffering (χ2 = 21.79, p < 0.001) than males. Participants' permanent residence (χ2 = 20.809, p < 0.001), monthly family income (χ2 = 5.701, p < 0.05), personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 11.403, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 21.219, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 21.775, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with depression status. In addition, their desired institute for admission (χ2 = 17.042, p < 0.001), average monthly expenditure during the admission test preparation time (χ2 = 6.927, p < 0.05), satisfied with previous mock tests (χ2 = 12.778, p < 0.001), educational background (χ2 = 14.164, p < 0.001), and anxiety (χ2 = 318.338, p < 0.001) significantly differed in terms of their depression status (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between depression and the study variables with respect to gender and student status.

| Variables | Total sample | Gender | Student status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Fresher test-taker | Repeat test-taker | |||||||

| Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | |

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 152; 42.9% | 21.792** | – | – | – | – | 102; 38.8% | 23.163** | 206; 60.1% | 0.777 |

| Female | 354; 57.1% | – | – | 461; 55.8% | 50; 54.9% | |||||

| Permanent residence | ||||||||||

| Urban | 571; 50.7% | 20.809** | 461; 54.7% | 9.056** | 110; 38.7% | 12.031** | 401; 48.7% | 17.145** | 170; 56.1% | 3.161 |

| Rural | 242; 64.2% | 202; 64.5% | 40; 62.5% | 159; 63.6% | 83; 65.4% | |||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Muslim | 697;53.7% | 0.870 | 567; 56.4% | 1.433 | 130; 44.4% | 0.123 | 483; 51.5% | 1.357 | 214; 59.3% | 0.048 |

| Others | 110; 57.3% | 93; 60.6% | 17; 39.4% | 73; 57% | 37; 57.8% | |||||

| Family type | ||||||||||

| Nuclear | 594; 53.3% | 2.150 | 487; 56.6% | 0.610 | 107; 42% | 1.971 | 411; 50.9% | 2.978 | 183; 59.6% | 0.024 |

| Joint | 201; 57.8% | 166; 59.3% | 35; 51.5% | 134; 57.3% | 67; 58.8% | |||||

| Monthly income (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 15,000 | 207;55.2% | 5.701* | 175; 57% | 3.307 | 32; 47.1% | 3.076 | 138; 51.9% | 4.923 | 69; 63.3% | 0.884 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 237; 61.9% | 205; 61.7% | 32; 62.7% | 154; 58.6% | 83; 69.2% | |||||

| > 30,000 | 172; 63.7% | 154; 64.4% | 18; 58.1% | 108; 62.1% | 64; 66.7% | |||||

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||||||||

| Yes | 94;61.8% | 3.267 | 70; 69.3% | 6.580* | 24; 47.1% | 0.006 | 60; 61.9% | 3.333 | 34; 61.8% | 0.131 |

| No | 719; 54.1% | 594; 56.1% | 125; 46.5% | 498; 52.1% | 221; 59.2% | |||||

| Drug usage status | ||||||||||

| Yes | 38; 64.4% | 2.340 | 35; 71.4% | 4.256* | 3; 30% | 1.037 | 27; 67.5% | 3.701 | 11; 57.9% | 0.033 |

| No | 772; 54.3% | 628; 56.6% | 144; 46.3% | 529; 52% | 243; 60% | |||||

| COVID-19 related information | ||||||||||

| Personal COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 86; 68.3% | 11.403** | 76; 73.1% | 12.114** | 10; 45.5% | 0.037 | 56; 63.6% | 5.533* | 30; 78.9% | 6.471* |

| No | 722; 52.6% | 585; 55.3% | 137; 43.4% | 498; 50.6% | 224; 57.7% | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 183; 66.5% | 21.219** | 167; 68.4% | 16.209** | 16; 51.6% | 0.916 | 119; 61.7% | 9.128** | 64; 78% | 14.319** |

| No | 627; 51.2% | 496; 54.1% | 131; 42.7% | 437; 49.7% | 190; 55.2% | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 death | ||||||||||

| Yes | 104; 72.2% | 21.775** | 87; 76.3% | 19.622** | 17; 56.7% | 2.280 | 65; 70.7% | 14.443** | 39; 75% | 6.281* |

| No | 706; 51.8% | 573; 54.7% | 133; 42.4% | 492; 49.9% | 214; 56.8% | |||||

| Admission-related variables | ||||||||||

| Appearance in the admission test | ||||||||||

| Fresher | 563; 51.7% | 6.630 | 461; 55.8% | 1.784 | 102; 38.8% | 7.207** | – | – | – | – |

| Repeat | 256; 59% | 206; 60.1% | 50; 54.9% | – | – | – | ||||

| Secondary School Certificate (SSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 178; 59.3% | 4.866 | 150; 58.1% | 5.241 | 28; 66.7% | 3.870 | 131; 59.8% | 6.521* | 47; 58% | 0.421 |

| Moderate | 260; 54.1% | 221; 55% | 39; 49.4% | 180; 51.3% | 80; 61.5% | |||||

| High (5) | 327; 60.7% | 285; 62.6% | 42; 50% | 212;59.9% | 115; 62.2% | |||||

| Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 83; 56.8% | 1.949 | 67; 53.6% | 8.319* | 16; 76.2% | 11.061** | 59; 64.8% | 5.661 | 24; 43.6% | 8.401* |

| Moderate | 212; 55.4% | 177; 54% | 35; 63.6% | 132; 51.4% | 80; 63.5% | |||||

| High (5) | 468; 59.5% | 412; 62.5% | 56; 44.1% | 330; 57.7% | 138; 64.5% | |||||

| Coached by professional coaching centers | ||||||||||

| No | 198; 52% | 3.138 | 161; 53% | 3.256 | 37; 48.1% | 0.159 | 97; 49.7% | 1.782 | 101; 54.3% | 5.020* |

| Yes | 593; 57.2% | 484; 59% | 109; 50.7% | 447; 55% | 146; 65.2% | |||||

| Desired institute/department for admission | ||||||||||

| Varsity | 578; 52.5% | 17.042** | 464; 54% | 17.787** | 114; 47.5% | 6.671 | 411; 51.3% | 10.355* | 167; 55.9% | 6.215 |

| Medical | 143; 65.9% | 118; 65.9% | 25; 65.8% | 95; 65.1% | 48; 67.6% | |||||

| Engineering | 54; 60.7% | 50; 63.3% | 4; 40% | 38; 59.4% | 16; 64% | |||||

| Agriculture | 23; 69.7% | 21; 84% | 2; 25% | 7; 58.3% | 16; 76.2% | |||||

| Satisfied with previous mock tests | ||||||||||

| No | 255; 50.2% | 12.778** | 209; 51.5% | 11.823** | 46; 45.1% | 1.142 | 176; 48.2% | 10.659** | 79; 55.2% | 2.293 |

| Yes | 510; 60.1% | 426; 62.1% | 84; 51.9% | 358; 59% | 152; 63.1% | |||||

| Average monthly expenditure (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 5000 | 111; 54.7% | 6.927* | 89; 53.9% | 7.901* | 22; 57.9% | 0.177 | 69; 51.1% | 10.438** | 42; 61.8% | 0.616 |

| 5000–10,000 | 353; 58.7% | 302; 59.6% | 51; 54.3% | 233; 55.3% | 120; 66.7% | |||||

| > 10,000 | 145; 66.8% | 129; 68.3% | 16; 57.1 | 109; 68.1% | 36; 63.2% | |||||

| Educational background | ||||||||||

| Science | 511; 57.7% | 14.164** | 425; 60.9% | 12.372** | 86; 45.7% | 1.217 | 337; 56.1% | 11.564** | 174; 61.1% | 1.384 |

| Arts | 244; 47.3% | 192; 49.9% | 52; 39.7% | 183; 45.2% | 61; 55% | |||||

| Commerce | 59; 54.1% | 48; 58.8% | 11; 40.7% | 40; 53.3% | 19; 55.9% | |||||

| Mental health problems | ||||||||||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||

| Yes | 384; 37.7% | 318.338** | 305; 40.3% | 246.43** | 79; 30.3% | 65.05** | 282; 37.2% | 212.19** | 102; 39.4% | 102.03** |

| No | 435; 86.1% | 362; 87.9% | 73; 78.5% | 281; 85.2% | 154; 88% | |||||

*Significant at 0.05 level; **Significant at 0.01 level.

In terms of the gender-based analysis, permanent residence was significantly associated with the depression status of males (χ2 = 9.056, p < 0.001) and female samples (χ2 = 12.031, p < 0.001). In addition, cigarette smoking status (χ2 = 6.580, p < 0.05), drug usage status (χ2 = 4.256, p < 0.05), personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 12.114, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 16.209, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 19.622, p < 0.001), HSC GPA (χ2 = 8.319, p < 0.05), desired institute for admission (χ2 = 17.787, p < 0.001), satisfaction with their previous mock tests (χ2 = 11.823, p < 0.001), average monthly expenditure (χ2 = 7.901, p < 0.05), educational background (χ2 = 12.372, p < 0.001) had a significant association with male depression status. In addition, anxiety (χ2 = 246.43, p < 0.001) significantly differed in terms of male depression status. However, female depressive symptoms were significantly associated with appearance with admission test (χ2 = 7.207, p < 0.001), HSC GPA (χ2 = 11.061, p < 0.001), and anxiety (χ2 = 65.05, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

In terms of the student-status-based analysis, first-time test-taker's depression was associated with personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 5.533, p < 0.05), family/friends COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 9.128, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 14.443, p < 0.001), SSC GPA (χ2 = 6.521, p < 0.05), desired institute/department for admission (χ2 = 10.355, p < 0.001), satisfaction with previous mock tests (χ2 = 10.659, p < 0.001), average monthly expenditure (χ2 = 10.438, p < 0.001), and educational background (χ2 = 11.564, p < 0.001). In addition, a significant association was also reported between first-time test-taker's depressive symptoms and anxiety (χ2 = 212.19, p < 0.001). However, COVID-19-related information such as personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 6.471, p < 0.05), family/friends COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 14.319, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 6.281, p < 0.05); admission test related variables such as HSC GPA (χ2 = 8.401, p < 0.05), coached by professional coaching centers (χ2 = 5.020, p < 0.05) had a profound association with repeat test-takers depression. In addition, anxiety (χ2 = 102.03, p < 0.001) was significantly associated with repeat test-taker’s depression (Table 2).

Association between anxiety and the study variables

In terms of the total sample, gender showed a significant difference with anxiety (χ2 = 9.870, p < 0.001). Participants' permanent residence (χ2 = 18.080, p < 0.001), monthly family income (χ2 = 11.357, p < 0.001), cigarette smoking (χ2 = 6.618, p < 0.05), drug usage (χ2 = 11.434, p < 0.001), personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 15.402, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 10.646, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 15.548, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with anxiety. In addition, appearance in admission test (χ2 = 14.056, p < 0.001), SSC GPA (χ2 = 15.215, p < 0.001), HSC GPA (χ2 = 7.063, p < 0.05), their desired institute for admission (χ2 = 17.739, p < 0.001), satisfied with previous mock tests (χ2 = 29.891, p < 0.001), educational background (χ2 = 14.234, p < 0.001), and depression (χ2 = 318.338, p < 0.001) significantly differed in terms of their anxiety status (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between anxiety and the study variables with respect to gender and student status.

| Variables | Total sample | Gender | Student status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Fresher test-taker | Repeat test-taker | |||||||

| Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | Yes (n; %) | χ2 test value | |

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 93;26.3% | 9.870** | – | – | – | – | 59; 22.4% | 10.167** | 34; 37.4% | 0.419 |

| Female | 412;35.2% | – | – | 271; 32.8% | 141; 41.1% | |||||

| Permanent residence | ||||||||||

| Urban | 341;30.3% | 18.080** | 276; 32.7% | 10.115** | 65; 22.9% | 7.127** | 229; 27.8% | 12.609** | 112; 37% | 3.941* |

| Rural | 159; 42.2% | 134; 42.8% | 25; 39.1% | 99; 39.6% | 60; 47.2% | |||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Muslim | 413; 33.2% | 0.560 | 350; 34.8% | 0.739 | 81; 27.6% | 0.012 | 284; 30.3% | 1.239 | 147; 40.7% | 0.234 |

| Others | 69; 35.9% | 58; 38.4% | 11; 26.8% | 45; 35.2% | 24; 37.5% | |||||

| Family type | ||||||||||

| Nuclear | 372; 33.4% | 0.465 | 306; 35.6% | 0.005 | 66; 25.9% | 2.366 | 244; 30.2% | 1.348 | 128; 41.7% | 0.544 |

| Joint | 123; 35.3% | 99; 35.4% | 24; 35.3% | 80; 34.2% | 43; 37.7% | |||||

| Monthly income (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 15,000 | 114; 30.4% | 11.357** | 99; 32.2% | 6.502* | 15; 22.1% | 7.004* | 70; 26.3% | 10.933** | 44; 40.4% | 1.469 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 152; 39.7% | 135; 40.7% | 17; 33.3% | 94; 35.7% | 58; 48.3% | |||||

| > 30,000 | 114; 42.2% | 99; 41.4% | 15; 48.4% | 71; 40.8% | 43; 44.8% | |||||

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||||||||

| Yes | 66; 43.4% | 6.618* | 50; 49.5% | 9.579** | 16; 31.4% | 0.157 | 39; 40.2% | 3.967* | 27; 49.1% | 1.757 |

| No | 438; 33% | 361; 34.1% | 77; 28.6% | 290; 30.4% | 148; 39.7% | |||||

| Yes | 32; 54.2% | 11.434** | 28; 57.1% | 10.638** | 4; 40%% | 0.690 | 20; 50% | 7.071** | 12; 63.2% | 4.022* |

| No | 469; 33% | 382; 34.4% | 87; 28% | 307; 30.2% | 162; 40% | |||||

| COVID-19 related information | ||||||||||

| Personal COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 62; 49.2% | 15.402** | 56; 53.8% | 17.534** | 6; 27.3% | 0.001 | 36; 40.9% | 4.925* | 26; 68.4% | 13.131** |

| No | 439; 32% | 352; 33.3% | 87; 27.5% | 291; 29.5% | 148; 38.1% | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 114; 41.5% | 10.646** | 106; 43.4% | 9.338** | 8; 25.8% | 0.001 | 76; 39.4% | 9.004** | 38; 46.3% | 1.754 |

| No | 382; 31.2% | 302; 32.9% | 80; 26.1% | 250; 28.4% | 132; 38.4% | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 death | ||||||||||

| Yes | 69; 47.9% | 15.548** | 59; 51.8% | 15.543** | 10; 33.3% | 0.661 | 41; 44.6% | 9.740** | 28; 53.8% | 4.333* |

| No | 413; 31.6% | 348; 33.2% | 83; 26.4% | 285; 28.9% | 146; 38.7% | |||||

| Admission-related variables | ||||||||||

| Appearance in the admission test | ||||||||||

| Fresher | 330; 30.3% | 14.056** | 271; 32.8% | 7.314** | 59; 22.4% | 7.779** | – | – | – | – |

| Repeat | 175; 40.3% | 141; 41.1% | 34; 37.4% | – | – | – | ||||

| Secondary School Certificate (SSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 111; 37% | 15.215** | 97; 37.6% | 15.366** | 14; 33.3% | 0.695 | 79; 36.1% | 12.666** | 32; 39.5% | 2.417 |

| Moderate | 139;28.9% | 118; 29.4% | 21; 26.6% | 91; 25.9% | 48; 36.9% | |||||

| High (5) | 218; 40.4% | 192; 42.2% | 26; 31% | 134; 37.9% | 84; 45.4% | |||||

| Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 47; 32.2% | 7.063* | 42; 33.6% | 10.903** | 5; 23.8% | 1.801 | 33; 36.3% | 9.688** | 14; 25.5% | 6.571* |

| Moderate | 118; 30.8% | 98; 29.9% | 20; 36.4% | 65; 25.3% | 53; 42.1% | |||||

| High (5) | 301; 38.3% | 266; 40.4% | 35; 27.6% | 206; 36% | 95; 44.4% | |||||

| Coached by professional coaching centers | ||||||||||

| No | 129; 33.9% | 0.120 | 107; 35.2% | 0.036 | 22; 28.6% | 0.180 | 57; 29.2% | 0.669 | 72; 38.7% | 1.258 |

| Yes | 361; 34.8% | 294; 35.8% | 67; 31.2% | 262; 32.3% | 99; 44.2% | |||||

| Desired institute/department for admission | ||||||||||

| Varsity | 349; 31.7% | 17.739** | 283; 32.9% | 14.054** | 66; 27.5% | 5.225 | 241; 30.1% | 4.177 | 108; 36.1% | 18.309** |

| Medical | 99; 45.6% | 82; 45.8% | 17; 44.7% | 56; 38.4% | 43; 60.6% | |||||

| Engineering | 28; 31.5% | 26; 32.9% | 2; 20% | 22; 34.4% | 6; 24% | |||||

| Agriculture | 15; 45.5% | 13; 52% | 2; 25% | 4; 33.3% | 11; 52.4% | |||||

| Satisfied with previous mock tests | ||||||||||

| No | 129; 25.4% | 29.891** | 106; 26.1% | 25.051** | 23; 22.5% | 4.732* | 76; 20.8% | 33.539** | 53; 37.1% | 1.377 |

| Yes | 339; 40% | 282; 41.1% | 57; 35.2% | 235; 38.7% | 104; 43.2% | |||||

| Average monthly expenditure (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 5,000 | 62; 30.5% | 4.088 | 52; 31.5% | 3.557 | 10; 26.3% | 1.590 | 36; 26.7% | 5.874 | 26; 38.2% | 4.501 |

| 5000–10,000 | 228; 37.9% | 195; 38.5% | 33; 35.1% | 140; 33.3% | 88; 48.9% | |||||

| > 10,000 | 84; 38.7% | 77; 40.7% | 7; 25% | 64; 40% | 20; 35.1% | |||||

| Educational background | ||||||||||

| Science | 324; 36.6% | 14.234** | 274; 39.3% | 18.463** | 50; 26.6% | 0.317 | 201; 33.4% | 11.836** | 123; 43.2% | 2.690 |

| Arts | 139; 26.9% | 103; 26.8% | 36; 27.5% | 99; 24.4% | 40; 36% | |||||

| Commerce | 40; 36.7% | 34; 41.5% | 6; 22.2% | 29; 38.7% | 11; 32.4% | |||||

| Mental health problems | ||||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||

| Yes | 70; 9.9% | 318.338** | 50; 10% | 246.43** | 20; 9.9% | 65.05** | 49; 9.3% | 212.19** | 21; 11.8% | 102.03** |

| No | 436; 53.1% | 362; 54.3% | 73; 48% | 281; 49.9% | 154; 60.2% | |||||

*Significant at 0.05 level; **Significant at 0.01 level.

In terms of the gender-based analysis, permanent residence was significantly associated with the anxiety status of males (χ2 = 10.115, p < 0.001) and female samples (χ2 = 7.127, p < 0.001). In addition, monthly family income (χ2 = 6.502, p < 0.05), cigarette smoking status (χ2 = 9.579, p < 0.001), drug usage status (χ2 = 10.638, p < 0.001), personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 17.534, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 9.338, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 15.543, p < 0.001), appearance in the admission test (χ2 = 7.314, p < 0.001), SSC GPA (χ2 = 15.366, p < 0.001), HSC GPA (χ2 = 10.903, p < 0.001), desired institute for admission (χ2 = 14.054, p < 0.001), satisfaction with their previous mock tests (χ2 = 20.051, p < 0.001), educational background (χ2 = 18.463, p < 0.001) had a significant association with male anxiety status. In addition, depression (χ2 = 246.43, p < 0.001) significantly differed in terms of male anxiety status. However, female anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with permanent residence (χ2 = 7.127, p < 0.001), monthly family income (χ2 = 7.004, p < 0.05), appearance with admission test (χ2 = 7.779, p < 0.001), Satisfaction with previous mock tests (χ2 = 4.732, p < 0.05), and depression (χ2 = 65.05, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

In terms of the student-status-based analysis, first-time test-takers anxiety was associated with permanent residence (χ2 = 12.609, p < 0.001), monthly family income (χ2 = 10.933, p < 0.001), cigarette smoking status (χ2 = 3.967, p < 0.05), drug usage status (χ2 = 7.071, p < 0.001), personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 4.925, p < 0.05), family/friends COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 9.004, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 9.740, p < 0.001), SSC GPA (χ2 = 12.666, p < 0.001), HSC GPA (χ2 = 9.688, p < 0.001), satisfaction with previous mock tests (χ2 = 35.539, p < 0.001), and educational background (χ2 = 11.836, p < 0.001). In addition, a significant association was also reported between first-time test-takers anxiety symptoms and depression (χ2 = 212.19, p < 0.001). However, permanent residence (χ2 = 3.941, p < 0.05), drug usage status (χ2 = 4.022, p < 0.05), COVID-19-related information such as personal COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 13.131, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (χ2 = 4.333, p < 0.05); admission tests related variables such as HSC GPA (χ2 = 6.571, p < 0.05), desired institute/department for admission (χ2 = 18.309, p < 0.001), and depression (χ2 = 102.03, p < 0.001) was significantly associated with repeat test takers anxiety (Table 3).

Factors associated with depression

In terms of the total sample, males were more likely to suffer from depression than females (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.38–2.24, p < 0.001). Participants from the urban area were at 1.74 times higher risk of suffering from depression than the rural participants (OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.37–2.22, p < 0.001). Personal COVID-19 infection (OR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.31–2.86, p = 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 infection (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.43–2.49, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.65–3.53, p < 0.001), not satisfied with previous mock tests (OR = 1.49, 95% CI = 1.19–1.86, p < 0.001), and suffering from anxiety (OR = 10.26, 95% CI = 7.73–13.60, p < 0.001) increased the risk of depression among participants (Table 4).

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression analysis concerning depression and the study variables with respect to gender and student status.

| Variables | Total sample | Gender | Student status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Fresher test-taker | Repeat test-taker | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 1.76 (1.38–2.24) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – | 1.99 (1.50–2.64) | < 0.001 | 1.23 (0.77–1.96) | 0.378 |

| Female | Reference | – | – | – | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Permanent residence | ||||||||||

| Urban | 1.74 (1.37–2.22) | < 0.001 | 1.50 (1.15–1.97) | 0.003 | 2.63 (1.50–4.61) | 0.001 | 1.84 (1.37–2.46) | < 0.001 | 1.47 (0.96–2.26) | 0.076 |

| Rural | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Muslim | 0.35 (0.63–1.17) | 0.351 | 0.80 (0.56–1.14) | 0.232 | 1.12 (0.58–2.18) | 0.726 | 0.80 (0.55–1.16) | 0.245 | 1.06 (0.62–1.82) | 0.826 |

| Others | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Family type | ||||||||||

| Nuclear | 0.83 (0.65–1.06) | 0.143 | 0.897 (0.68–1.17) | 0.435 | 0.68 (0.39—1.16) | 0.162 | 0.77 (0.57–1.03) | 0.085 | 1.03 (0.66–1.60) | 0.876 |

| Joint | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Monthly income (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 15,000 | 0.70 (0.50–0.96) | 0.058 | 0.73 (0.51–1.03) | 0.192 | 0.64 (0.27–1.51) | 0.218 | 0.65 (0.44–0.97) | 0.086 | 0.86 (0.48–1.53) | 0.643 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 0.89 (0.63–1.25) | 1.21 (0.48–3.02) | 0.86 (0.58–1.27) | 1.12 (0.63–1.99) | |||||

| > 30,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.37 (0.97–1.93) | 0.072 | 1.76 (1.13–2.74) | 0.011 | 1.02 (0.56–1.86) | 0.938 | 1.48 (0.96–2.28) | 0.069 | 1.11 (0.62–1.99) | 0.717 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Drug usage status | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.52 (0.88–2.62) | 0.129 | 1.92 (1.02–3.61) | 0.042 | 0.49 (0.12–1.95) | 0.317 | 1.91 (0.97–3.75) | 0.058 | 0.91 (0.36–2.32) | 0.855 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| COVID-19 related information | ||||||||||

| Personal COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.93 (1.31–2.86) | 0.001 | 2.19 (1.39–3.43) | 0.001 | 1.08 (0.45–2.59) | 0.848 | 1.71 (1.08–2.68) | 0.020 | 2.74 (1.22–6.14) | 0.014 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.89 (1.43–2.49) | < 0.001 | 1.84 (1.36–2.48) | < 0.001 | 1.43 (0.68–3.03) | 0.340 | 1.63 (1.18–2.24) | 0.003 | 2.88 (1.63–5.06) | < 0.001 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 death | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2.41 (1.65–3.53) | < 0.001 | 2.67 (1.70–4.18) | < 0.001 | 1.78 (0.83–3.79) | 0.135 | 2.41 (1.51–3.84) | < 0.001 | 2.28 (1.18–4.42) | 0.014 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Admission-related variables | ||||||||||

| Appearance in the admission test | ||||||||||

| Fresher | 0.74 (0.59–0.93) | 0.010 | 0.84 (0.65–1.08) | 0.182 | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) | 0.008 | – | – | – | – |

| Repeat | Reference | Reference | Reference | – | – | – | ||||

| Secondary School Certificate (SSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 0.94 (0.70–1.26) | 0.088 | 0.82 (0.60–1.13) | 0.073 | 2.00 (0.92–4.32) | 0.151 | 0.99 (0.70–1.40) | 0.039 | 0.84 (0.49–1.43) | 0.811 |

| Moderate | 0.76 (0.59–0.97) | 0.72 (0.55–0.95) | 0.97 (0.52–4.32) | 0.70 (0.52–0.95) | 0.97 (0.61–1.54) | |||||

| High (5) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 0.89 (0.62–1.27) | 0.378 | 0.69 (0.47–1.01) | 0.016 | 4.05 (1.40–11.75) | 0.005 | 1.35 (0.85–2.14) | 0.060 | 0.42 (0.23–0.77) | 0.017 |

| Moderate | 0.84 (0.65–1.07) | 0.70 (0.53–0.91) | 2.21 (1.15–4.25) | 0.77 (0.57–1.04) | 0.95 (0.60–1.51) | |||||

| High (5) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Coached by professional coaching centers | ||||||||||

| No | 1.23 (0.97–1.56) | 0.077 | 0.78 (0.60–1.02) | 0.071 | 0.90 (0.53–1.51) | 0.690 | 0.80 (0.59–1.10) | 0.182 | 0.63 (0.42–0.94) | 0.025 |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Desired institute/department for admission | ||||||||||

| Varsity | 0.48 (0.22–1.02) | 0.001 | 0.22 (0.07–0.65) | 0.001 | 2.71 (0.53–13.71) | 0.096 | 0.75 (0.23–2.39) | 0.017 | 0.39 (0.14–1.10) | 0.109 |

| Medical | 0.84 (0.38–1.85) | 0.36 (0.12–1.12) | 5.76 (1.01–32.70) | 1.33 (0.40–4.40) | 0.65 (0.21–2.0) | |||||

| Engineering | 0.67 (0.28–1.57) | 0.32 (0.10–1.05) | 2.00 (0.26–15.38) | 1.04 (0.29–3.64) | 0.55 (0.15–2.02) | |||||

| Agriculture | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Satisfied with previous mock tests | ||||||||||

| No | 1.49 (1.19–1.86) | < 0.001 | 1.54 (1.20–1.98) | 0.001 | 1.31 (0.79–2.15) | 0.286 | 1.54 (1.18–2.00) | 0.001 | 1.38 (0.90–2.10) | 0.130 |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Average monthly expenditure (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 5000 | 0.59 (0.40–0.89) | 0.032 | 0.54 (0.35–0.84) | 0.020 | 1.03 (0.38–2.76) | 0.915 | 0.48 (0.30–0.78) | 0.006 | 0.94 (0.45–1.95) | 0.735 |

| 5000–10,000 | 0.70 (0.51–0.97) | 0.68 (0.48–0.97) | 0.89 (0.38–2.08) | 0.58 (0.39–0.85) | 1.16 (0.62–2.17) | |||||

| > 10,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Educational background | ||||||||||

| Science | 1.15 (0.77–1.72) | 0.001 | 1.10 (0.69–1.75) | 0.002 | 1.22 (0.54–2.78) | 0.545 | 1.11 (0.69–1.80) | 0.003 | 1.23 (0.60–2.53) | 0.501 |

| Arts | 0.76 (0.50–1.15) | 0.70 (0.43–1.14) | 0.95 (0.41–2.22) | 0.72 (0.44–1.18) | 0.96 (0.44–2.08) | |||||

| Commerce | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Mental health problems | ||||||||||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||

| Yes | 10.26 (7.73–13.60) | < 0.001 | 10.72 (7.71–14.91) | < 0.001 | 8.40 (4.80–14.73) | < 0.001 | 9.70 (6.92–13.59) | < 0.001 | 11.28 (6.71–18.97) | < 0.001 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In terms of gender-based analysis, urban males were at higher risk of depression than rural males (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.15–1.97, p = 0.003). Male cigarette smokers (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.13–2.74, p = 0.011), drug users (OR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.02–3.61, p = 0.042), self-infected with COVID-19 (OR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.39–3.43, p = 0.001), family/friends infected with COVID-19 (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.36–2.48, p < 0.001), family/friends died due to COVID-19 (OR = 2.67, 95% CI = 1.70–4.18, p < 0.001), not satisfied with previous mock tests (OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.20–1.98, p = 0.001), and suffering from anxiety (OR = 10.72, 95% CI = 7.71–14.91, p < 0.001), increased the risk of depression. However, female depressive symptoms increased in terms of urban residence (OR = 2.63, 95% CI = 1.50–4.61, p = 0.001), HSC GPA (OR = 4.05, 95% CI = 1.40–11.75, for poor and OR = 2.21, 95% CI = 1.15–4.25, for moderate; p = 0.005), and anxiety (OR = 8.40, 95% CI = 4.80–14.73, p < 0.001) (Table 4).

In terms of student status-based analysis, urban residence (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.37–2.46, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 infection (OR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.18–2.24, p = 0.003), family/friends COVId-19 death (OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.51–3.84, p < 0.001), not satisfied with previous mock tests (OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.18–2.00, p = 0.001), and suffering from anxiety (OR = 9.70, 95% CI = 6.92–13.59, p < 0.001), increased the risk of depression among first-time test-takers. Repeat test-takers risk of depression was increased by 2.74 times (OR = 2.74; 95% CI = 1.22–6.14, p = 0.014), 2.88 times (OR = 2.88; 95% CI = 1.63–5.06, p < 0.001), and 2.28 times (OR = 2.28; 95% CI = 1.18–4.42, p = 0.014) due to personal COVID-19 infection, family/friends COVID-19 infection, and family/friends COVID-19 death, respectively (Table 4).

Factors associated with anxiety

In terms of the total sample, males were more likely to suffer from anxiety than females (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.17–1.99, p = 0.002). Participants from the urban area were at a 1.68 times higher risk of suffering from depression than the rural participants (OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.32–2.13, p < 0.001). Cigarette smoking (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.10–2.19, p = 0.011), drug usage (OR = 2.40, 95% CI = 1.42–4.06, p = 0.001), personal COVID-19 infection (OR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.42–2.97, p < 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 infection (OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.19–2.04, p = 0.001), family/friends COVID-19 death (OR = 1.98, 95% CI = 1.40–2.81, p < 0.001), not satisfied with previous mock tests (OR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.53–2.49, p < 0.001), and suffering from depression (OR = 10.26, 95% CI = 7.73–13.60, p < 0.001) increased the risk of anxiety among participants (Table 5).

Table 5.

Binary logistic regression analysis concerning anxiety and the study variables with respect to gender and student status.

| Variables | Total sample | Gender | Student status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Fresher test-taker | Repeat test-taker | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 1.52 (1.17–1.99) | 0.002 | – | – | – | – | 1.68 (1.22–2.33) | 0.002 | 1.17 (0.72–1.88) | 0.518 |

| Female | Reference | – | – | – | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Permanent residence | ||||||||||

| Urban | 1.68 (1.32–2.13) | < 0.001 | 1.53 (1.17–2.00) | 0.002 | 2.16 (1.21–3.83) | 0.008 | 1.70 (1.26–2.29) | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.00–2.32) | 0.048 |

| Rural | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Muslim | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.454 | 0.85 (0.60–1.21) | 0.390 | 1.04 (0.49–2.17) | 0.913 | 0.80 (0.54–1.18) | 0.266 | 1.14 (0.66–1.98) | 0.628 |

| Others | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Family type | ||||||||||

| Nuclear | 0.91 (0.71–1.17) | 0.495 | 1.01 (0.76–1.33) | 0.946 | 0.64 (0.36–1.13) | 0.126 | 0.83 (0.61–1.13) | 0.246 | 1.18 (0.75–1.83) | 0.461 |

| Joint | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Monthly income (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 15,000 | 0.59 (0.43–0.82) | 0.004 | 0.67 (0.47–1.35) | 0.039 | 0.30 (0.12–0.74) | 0.034 | 0.51 (0.34–0.77) | 0.004 | 0.83 (0.47–1.45) | 0.481 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 0.90 (0.65–1.23) | 0.96 (0.69–1.35) | 0.53 (0.21–1.33) | 0.80 (0.54–1.19) | 1.15 (0.67–1.97) | |||||

| > 30,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.55 (1.10–2.19) | 0.011 | 1.89 (1.25–2.85) | 0.002 | 1.14 (0.59–2.17) | 0.692 | 1.54 (1.00–2.36) | 0.048 | 1.46 (0.83–2.58) | 0.187 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Drug usage status | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2.40 (1.42–4.06) | 0.001 | 2.54 (1.42–4.54) | 0.002 | 1.71 (0.47–6.23) | 0.411 | 2.31 (1.22–4.36) | 0.010 | 2.57 (0.99–6.67) | 0.052 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| COVID-19 related information | ||||||||||

| Personal COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2.06 (1.42–2.97) | < 0.001 | 2.33 (1.55–3.50) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.37–2.60) | 0.979 | 1.65 (1.05–2.58) | 0.028 | 3.51 (1.72–7.17) | 0.001 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 infection | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.56 (1.19–2.04) | 0.001 | 1.56 (1.17–2.08) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.42–2.29) | 0.976 | 1.63 (1.18–2.26) | 0.003 | 1.38 (0.85–2.25) | 0.186 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Family/friend’s COVID-19 death | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.98 (1.40–2.81) | < 0.001 | 2.15 (1.46–3.18) | < 0.001 | 1.39 (0.62–3.09) | 0.418 | 1.97 (1.28–3.04) | 0.002 | 1.84 (1.03–3.30) | 0.039 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Admission-related variables | ||||||||||

| Appearance in the admission test | ||||||||||

| Fresher | 0.64 (0.51–0.81) | < 0.001 | 0.70 (0.54–0.90) | 0.007 | 0.48 (0.29–0.81) | 0.006 | – | – | – | – |

| Repeat | Reference | Reference | Reference | – | – | – | ||||

| Secondary School Certificate (SSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 0.86 (0.64–1.15) | 0.001 | 0.82 (0.60–1.12) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (0.50–2.46) | 0.707 | 0.92 (0.65–1.31) | 0.002 | 0.78 (0.46–1.33) | 0.300 |

| Moderate | 0.59 (0.46–0.77) | 0.56 (0.42–0.75) | 0.80 (0.40–1.59) | 0.57 (0.41–0.79) | 0.70 (0.44–1.11) | |||||

| High (5) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) grade point average | ||||||||||

| Poor (< 4.5) | 0.76 (0.52–1.11) | 0.030 | 0.74 (0.50–1.11) | 0.004 | 0.82 (0.28–2.41) | 0.409 | 1.01 (0.63–1.60) | 0.008 | 0.42 (0.22–0.83) | 0.042 |

| Moderate | 0.71 (0.55–0.93) | 0.63 (0.47–0.83) | 1.50 (0.76–2.94) | 0.60 (0.43–0.83) | 0.90 (0.58–1.41) | |||||

| High (5) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Coached by professional coaching centers | ||||||||||

| No | 0.95 (0.74–1.22) | 0.729 | 0.97 (0.73–1.28) | 0.849 | 0.88 (0.49–1.56) | 0.672 | 0.86 (0.61–1.22) | 0.414 | 0.79 (0.53–1.18) | 0.262 |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Desired institute/department for admission | ||||||||||

| Varsity | 0.55 (0.27–1.11) | 0.001 | 0.45 (0.20–1.00) | 0.003 | 1.13 (0.22–5.78) | 0.168 | 0.86 (0.25–2.88) | 0.246 | 0.51 (0.21–1.25) | 0.001 |

| Medical | 1.00 (0.48–2.10) | 0.78 (0.33–1.80) | 2.42 (0.43–13.60) | 1.24 (0.35–4.32) | 1.39 (0.52–3.71) | |||||

| Engineering | 0.55 (0.24–1.24) | 0.45 (0.18–1.13) | 0.75 (0.08–6.95) | 1.04 (0.28–3.86) | 0.28 (0.08–1.00) | |||||

| Agriculture | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Satisfied with previous mock tests | ||||||||||

| No | 1.95 (1.53–2.49) | < 0.001 | 1.97 (1.51–2.58) | < 0.001 | 1.86 (1.05–3.28) | 0.031 | 2.40 (1.77–3.24) | < 0.001 | 1.28 (0.84–1.97) | 0.241 |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Average monthly expenditure (BDT) | ||||||||||

| < 5000 | 0.69 (0.46–1.04) | 0.131 | 0.66 (0.43–1.03) | 0.170 | 1.07 (0.35–3.28) | 0.454 | 0.54 (0.33–0.89) | 0.054 | 1.14 (0.55–2.38) | 0.107 |

| 5000–10,000 | 0.96 (0.70–1.33) | 0.90 (0.64–1.27) | 1.62 (0.62–4.21) | 0.74 (0.51–1.08) | 1.77 (0.95–3.28) | |||||

| > 10,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Educational background | ||||||||||

| Science | 0.99 (0.65–1.50) | 0.001 | 0.91 (0.57–1.45) | < 0.001 | 1.26 (0.48–3.32) | 0.854 | 0.79 (0.48–1.30) | 0.003 | 1.58 (0.74–3.38) | 0.262 |

| Arts | 0.63 (0.41–0.98) | 0.51 (0.31–0.84) | 1.32 (0.49–3.55) | 0.51 (0.30–0.86) | 1.17 (0.52–2.66) | |||||

| Commerce | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Mental health problems | ||||||||||

| Anxiety | ||||||||||

| Yes | 10.26 (7.73–13.60) | < 0.001 | 10.72 (7.71–14.91) | < 0.001 | 8.40 (4.80–14.73) | < 0.001 | 9.70 (6.92–13.59) | < 0.001 | 11.28 (6.71–18.97) | < 0.001 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In terms of gender-based analysis, urban males were at higher risk of anxiety than rural males (OR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.17–2.00, p = 0.002). Male cigarette smokers (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.25–2.85, p = 0.002), drug users (OR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.42–4.54, p = 0.002), self-infected with COVID-19 (OR = 2.33, 95% CI = 1.55–3.50, p < 0.001), family/friends infected with COVID-19 (OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.17–2.08, p < 0.001), family/friends died due to COVID-19 (OR = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.46–3.18, p < 0.001), not satisfied with previous mock tests (OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.51–2.58, p < 0.001), and suffering from depression (OR = 10.72, 95% CI = 7.71–14.91, p < 0.001), increased the risk of depression. However, female anxiety symptoms increased in terms of urban residence (OR = 2.16, 95% CI = 1.21–3.83, p = 0.008), not satisfied with previous mock tests (OR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.05–3.28, p = 0.031), and depression (OR = 8.40, 95% CI = 4.80–14.73, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

In terms of student’s status-based analysis, urban residence (OR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.26–2.29, p < 0.001), drug user (OR = 2.31, 95% CI = 1.22–4.36, p = 0.010), family/friends COVID-19 infection (OR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.18–2.26, p = 0.003), family/friends COVID-19 death (OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.28–3.04, p = 0.002), not satisfied with previous mock tests (OR = 2.40, 95% CI = 1.77–3.24, p < 0.001), and suffering from depression (OR = 9.70, 95% CI = 6.92–13.59, p < 0.001), increased the risk of depression among first-time test-takers. Repeat test-taker's risk of anxiety was increased by 3.51 times (OR = 3.51; 95% CI = 1.72–7.17, p = 0.001), 1.84 times (OR = 1.84; 95% CI = 1.03–3.30, p = 0.039), and 11.28 times (OR = 11.28; 95% CI = 6.71–18.97, p < 0.001), due to personal COVID-19 infection, family/friends COVID-19 death, and depression, respectively (Table 5).

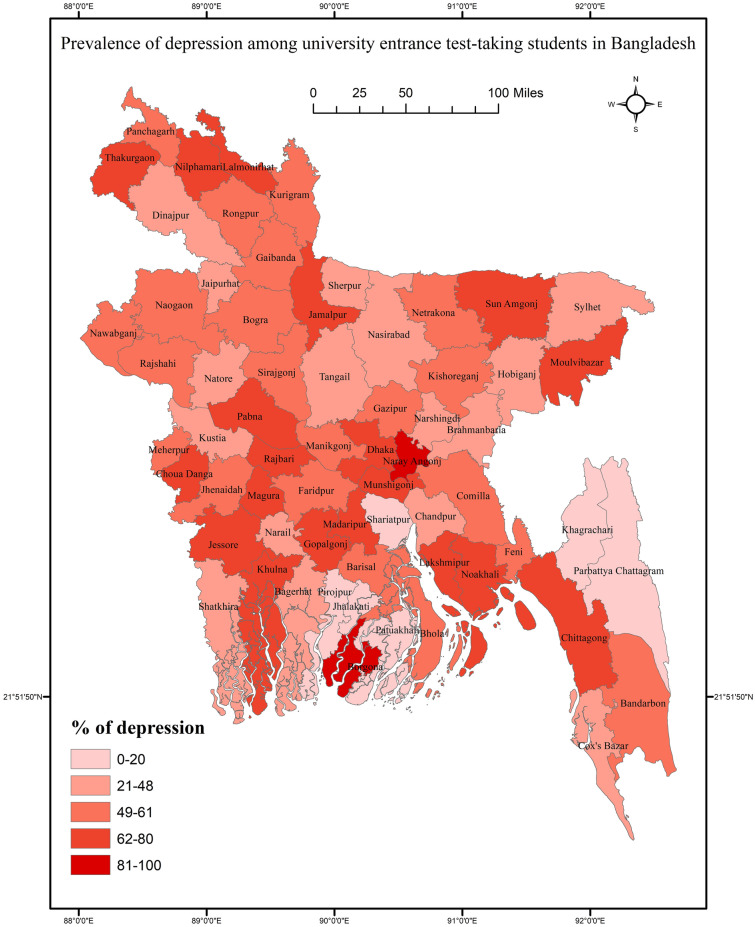

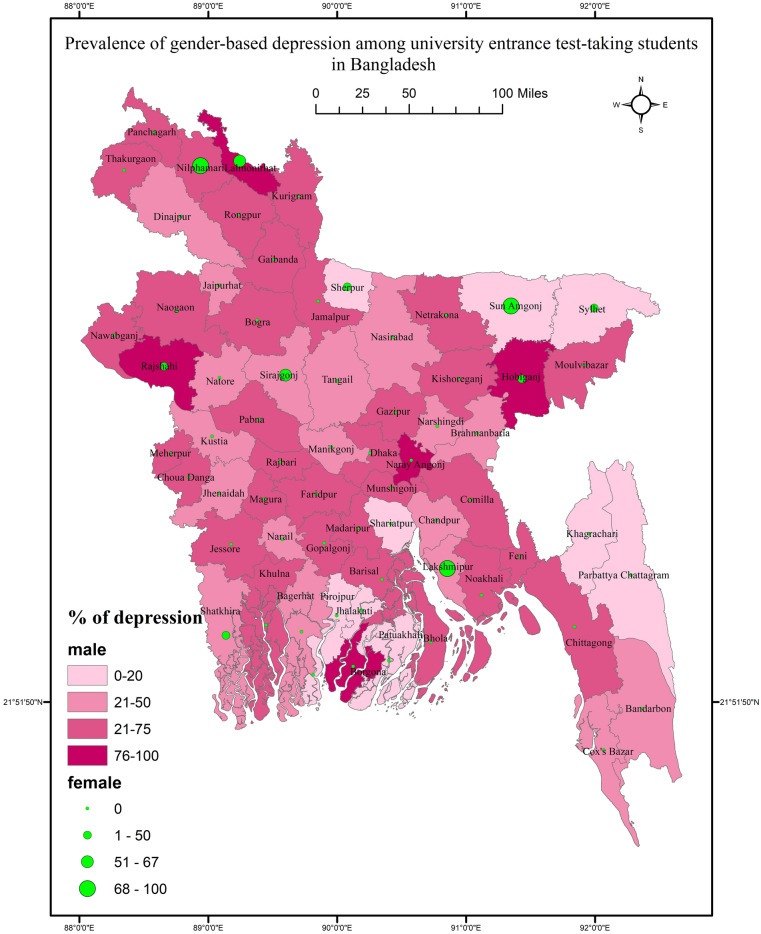

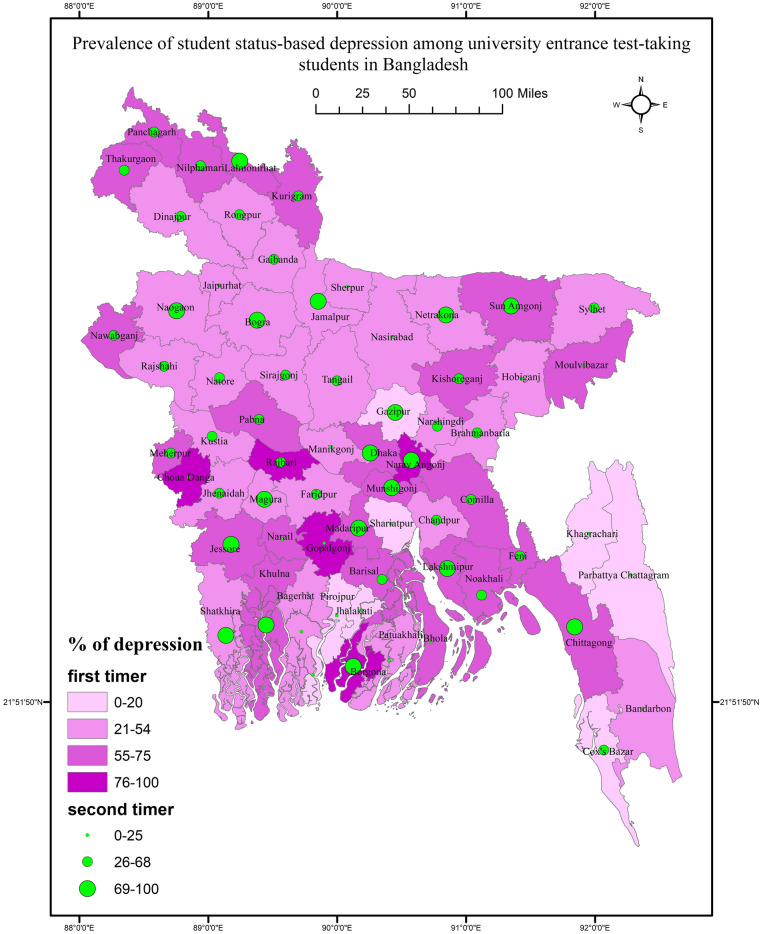

GIS-based distribution of depression across districts

Results suggested no significant association between the district and depression (χ2 = 65.226, p = 0.332). The prevalence of depression was high in some northern districts, such as Thakurgaon, Nilphamari, and Lalmonirhat, and in some western districts, such as Pabna, Rajbari, Magura, Chuadanga, Jashore, and Khulna. However, low prevalence was reported in Tangail, Sylhet, Khagrachari, and Sherpur (Fig. 1). Depression was not significantly differed in terms of gender (χ2 = 63.615, p = 0.211, for males, and χ2 = 8.316, p = 0.628, for females) and student status (χ2 = 51.237, p = 0.833, for first-time test-takers; and χ2 = 61.747, p = 0.098 for repeat test-takers). However, the rate of gender-based depression was high in Lalmonirhat, Rajshahi, and Hobiganj (Fig. 2). Regarding student status, Lalmonirhat, Thakurgaon, Borgona, Sunamganj, and Narayanganj showed a high prevalence of depression (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of depression among university entrance test-taking students in Bangladesh.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of gender-based depression among university entrance test-taking students in Bangladesh.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of student status-based depression among university entrance test-taking students in Bangladesh.

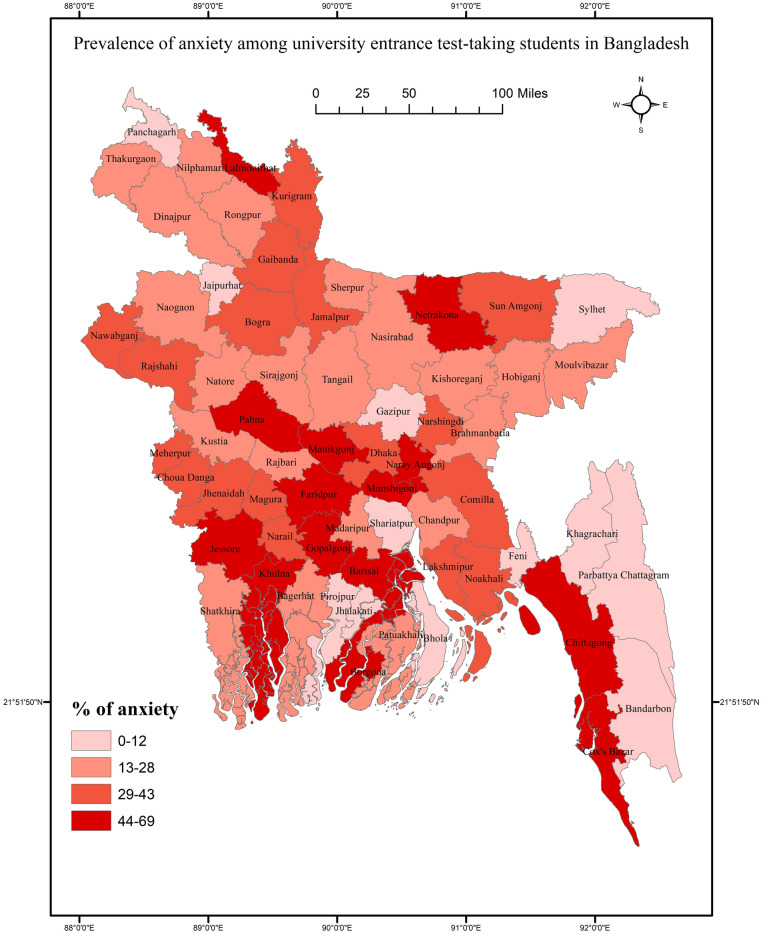

GIS-based distribution of anxiety across districts

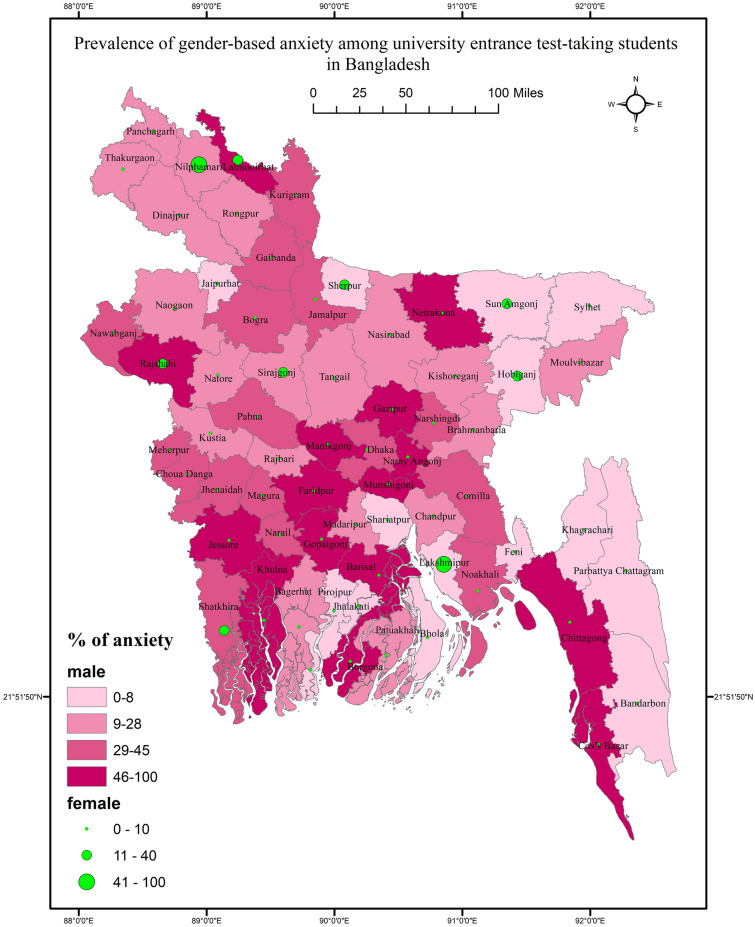

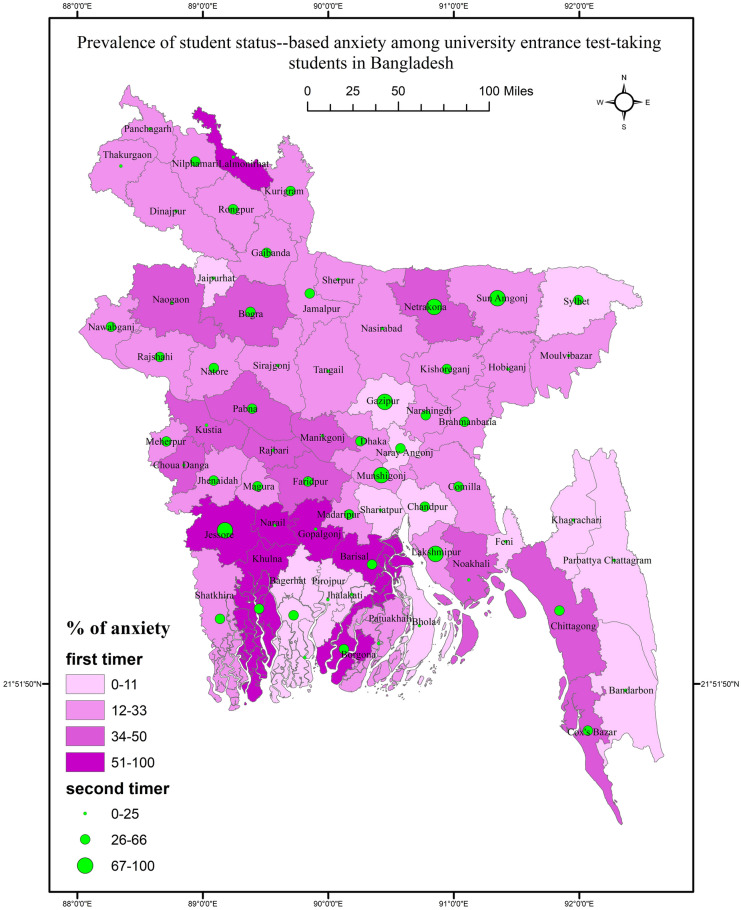

Results suggested a significant association between the districts and anxiety (χ2 = 111.966, p < 0.001). The prevalence rate of anxiety was high in Netrakona, Pabna, Manikganj, Jashore, Khulna, Barislal, and Chittagong (Fig. 4). Gender-based anxiety was only significant for males (χ2 = 112.191, p < 0.001). The gender-based anxiety was high in Rajshahi and Lalmonirhat districts (Fig. 5). In terms of student status, the prevalence rate significantly differed for first-time test takers (χ2 = 79.403, p = 0.026) and repeat test-takers (χ2 = 80.060, p < 0.001). The student status-based anxiety was high in Jashore, Barisal, Netrakona, and Borgona (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of anxiety among university entrance test-taking students in Bangladesh.

Fig. 5.

Prevalence of gender-based anxiety among university entrance test-taking students in Bangladesh.

Fig. 6.

Prevalence of student status-based anxiety among university entrance test-taking students in Bangladesh.

Discussion

This study represents the first examination of the prevalence of mental health conditions, specifically depression and anxiety, among Bangladeshi university entrance examinees following the COVID-19 outbreak, utilizing GIS distribution. The findings reveal a significant increase in the rates of depression and anxiety compared to a previous study conducted among a similar population. This study reports that 53.8% of the participants are depressed, while 33.3% are anxious, showing a dramatic rise from the previous figures of 47.9% and 28.9%, respectively16. This increase is not surprising, as COVID-19 has had a profound impact on student mental health. Furthermore, the university entrance phase is a critical transitional period in students' educational lives, and the disruption caused by the pandemic, including the extended academic year and the challenges faced during exam preparation, may have contributed to the heightened mental health problems observed. Notably, the present study also revealed higher mental health problems among repeat test-takers.

The study also highlights the influence of COVID-19-related factors on the student's mental health. Previous studies have indicated that COVID-19 patients tend to experience high levels of depression19, and this study echoes those findings, suggesting that factors such as the fear of infection, fear of assault or humiliation, financial difficulties, and inadequate food supply significantly contribute to mental health problems among students8. Additionally, the fear of social isolation and loneliness may exacerbate psychological suffering20. These COVID-19-related factors are important to consider when examining the mental health status of university entrance examinees. The pandemic has created a unique set of stressors and challenges that impact individuals' mental well-being. The fear and uncertainty surrounding COVID-19, coupled with the disruptions in daily life and potential health risks, can significantly contribute to the development or exacerbation of mental health illness as well as extreme conditions like suicide21. The findings of this study emphasize the need for targeted interventions and support systems to address the specific concerns arising from the pandemic and its impact on the mental health of university entrance examinees.

This study also highlights the influence of participants' residential areas on their mental health status, particularly among university entrance examinees. While this finding emphasized the higher prevalence of mental health issues among urban students, it's essential to recognize the challenges faced by students in rural areas as well. Previous studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic consistently reported that individuals residing in urban areas are more susceptible to experiencing psychological problems8. Consistent with these findings, the present study revealed that urban students were 1.74 times more likely to suffer from depression and 1.68 times more likely to experience anxiety compared to rural students. Several factors may contribute to the higher prevalence of psychological problems among urban students. Firstly, the lack of close-knit community ties in urban areas can lead to feelings of isolation and a reduced support system, which in turn can negatively impact mental well-being22,23. Additionally, easy access to substances and the associated risks of substance abuse may be more prevalent in urban environments24, further contributing to mental health issues25. Moreover, the widespread availability and excessive use of the Internet among urban students can lead to addictive behaviors and social media-related stress, which have been linked to mental health problems26. Finally, parents in urban areas may have higher academic expectations for their children, creating additional pressure and stress that may increase the risk of depression and anxiety among students27. However, understanding the relationship between residential areas and mental health status is crucial for developing targeted interventions and support systems. Recognizing the unique challenges faced by both urban and rural students and addressing the underlying factors that contribute to their mental health problems can help mitigate the impact of these issues. Effective strategies may involve fostering community connections, promoting healthy coping mechanisms, providing mental health support services, and engaging parents in open and supportive communication regarding academic expectations. By tailoring interventions to the specific needs of students from diverse geographical backgrounds, it is possible to improve their mental well-being and ultimately enhance their overall academic performance and quality of life.

The gender-based comparison in this study revealed a surprising finding, that is, male students exhibited higher levels of depression and anxiety compared to females, which contradicts the results of previous studies that reported higher rates of depression among females conducted in different student cohorts28,29. But it is worthy of note that the female entrance test appearing students reported having a higher risk of suicidality16 as well as burnout symptoms30, as reported in the previous studies from the same project. However, the causes of depression among males may stem from various factors. Firstly, male students often face high levels of stress and pressure to excel academically, which can contribute to the development of depressive symptoms15. Additionally, societal and cultural expectations of masculinity may further exacerbate the risk of depression and anxiety among male students31. Traditional notions of masculinity often discourage the expression of emotions and vulnerability, leading to suppressed feelings that can manifest as mental health issues32. These unique stressors and societal pressures faced by male students may explain the higher rates of depression and anxiety observed in this study.

Furthermore, this study found that depression and anxiety rates were significantly higher among repeat test-takers compared to first-time test-takers. This finding is not surprising considering that repeat test-takers have already experienced academic failure and the loss of an entire academic year. These circumstances can induce significant psychological pressure and act as triggering factors for burnout. Previously, it has been indicated that repeat test-takers are at a higher risk of suffering from burnout symptoms compared to first-time test-takers, with burnout itself being significantly associated with depression and anxiety among students30. The added stress of repeating the exam, coupled with the disappointment and frustration from previous academic setbacks33, likely contributes to the elevated rates of depression and anxiety among repeat test-takers. Additionally, the present study highlighted that dissatisfaction with previous mock test results further increases the risk of mental health problems. Negative experiences and perceived inadequacy in performance can contribute to a cycle of self-doubt and psychological distress34. Thus, academic institutions and mental health professionals can implement strategies to address the academic pressures faced by test-taking students and provide them with resources to cope effectively. In addition, support programs can be designed to assist repeat test-takers in managing the psychological burden associated with their academic setbacks and help them build resilience.

The GIS distribution analysis in this study revealed interesting patterns related to the prevalence of depression and anxiety across different districts. While districts like Thakurgaon, Nilphamari, and Lalmonirhat, as well as other western districts, showed a higher prevalence of depression, the differences observed were not statistically significant. This indicates that there may be some geographic variability in the rates of depression, but further investigation is needed to determine the underlying factors contributing to these differences. Similarly, the GIS-based analysis did not find any significant association between any gender and districts in terms of depression prevalence. However, when considering the student status of repeat test-takers, a significant difference in depression distribution across the districts was observed. This suggests that the geographic distribution of depression among repeat test-takers varies significantly, indicating potential contextual factors influencing mental health outcomes in specific districts, for instance, districts near the capital and northwest districts. In contrast to depression, anxiety was found to be significantly associated with districts. This finding suggests that the geographic location of participants plays a role in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms. In Bangladesh, students are often required to travel from one institution to another to attend university entrance tests. This traveling requirement can create added stress and logistical challenges for students, such as managing accommodations and completing the journey. These factors may contribute to the development of anxiety symptoms among students, particularly those from different districts who have to adapt to new environments and navigate unfamiliar circumstances. Additionally, the lack of confidence in performing well on the exam, financial burdens associated with traveling and food expenses, and social and cultural factors may also influence anxiety levels among the participants from different districts. However, understanding the geographic distribution of mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, can help inform targeted interventions and support services. By identifying areas with higher prevalence rates, resources can be allocated to provide adequate mental health support and interventions tailored to the specific needs of those districts. Besides, addressing the unique challenges faced by students traveling for university entrance tests, such as improving accessibility and reducing logistical burdens, can help alleviate anxiety symptoms and promote better mental well-being among these individuals.

Stigma reduction and promoting mental health literacy

For reducing stigma and improving mental health literacy among university entrance test-taking students, several strategies can be suggested. By implementing these strategies, academic institutions can create a supportive and inclusive environment that promotes mental health awareness, reduces stigma, and empowers university entrance test-takers to prioritize their well-being.

Education and awareness campaigns: Implementing educational initiatives aimed at increasing awareness and understanding of mental health issues among university entrance test-takers can help combat stigma. These campaigns can include workshops, seminars, and informational sessions that provide accurate information about mental health disorders, symptoms, and available support services.

Peer support programs: Establishing peer support programs within academic settings can create safe spaces for students to discuss their mental health concerns openly. Peer support groups, led by trained facilitators or mental health professionals, can offer emotional support, validation, and practical coping strategies to help students navigate their mental health challenges.

Integration of mental health education into curriculum: Incorporating mental health education into the curriculum of university entrance test preparation programs can promote mental health literacy among students. By integrating topics related to stress management, self-care, and seeking help for mental health concerns, students can develop the skills and knowledge needed to maintain their well-being.

Destigmatizing language and attitudes: Promoting language that is inclusive, respectful, and non-stigmatizing when discussing mental health can help create a more supportive academic environment. Encouraging faculty, staff, and students to use person-first language and avoid derogatory terms can contribute to reducing the stigma surrounding mental health.

Accessible mental health resources: Ensuring access to mental health resources and support services for university entrance test-takers is essential for reducing stigma and promoting help-seeking behaviors. This can include establishing counseling centers, helplines, and online resources that provide confidential support and information about available mental health resources.

Training for faculty and staff: Providing training for faculty and staff on recognizing signs of mental distress, responding effectively to students in crisis, and referring them to appropriate support services can facilitate early intervention and support for students struggling with mental health issues.

Collaboration with mental health organizations: Partnering with mental health organizations and advocacy groups can enhance efforts to reduce stigma and promote mental health literacy among university entrance test-takers. Collaborative initiatives can include organizing events, campaigns, and outreach activities aimed at raising awareness and destigmatizing mental health issues within academic settings.

Evaluation and feedback mechanisms: Establishing mechanisms for collecting feedback and evaluating the effectiveness of stigma reduction and mental health literacy initiatives is crucial for continuous improvement. Regular assessments can help identify areas for improvement and ensure that interventions are meeting the needs of university entrance test-takers effectively.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Firstly, the study's cross-sectional design restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between mental health problems and the studied variables. The findings provide a snapshot of the participants' mental health at a specific point in time, but long-term effects and causality cannot be determined. Secondly, the sampling technique employed in this study, which relied on convenience sampling, introduces potential biases. The study’s exclusive focus on a single center restricts the generalizability of the findings, as center-specific factors may impact the results. Furthermore, the unequal distribution of participants across gender, student status, and districts is another limitation. Although attempts were made to address this issue through statistical analysis, there is still a possibility of unequal representation, potentially affecting the study's findings. In particular, we recognize the need for a more inclusive gender analysis to explore the experiences of non-binary and transgender students. Moreover, the reliance on quantitative methods may not fully capture the depth of students' experiences with anxiety and depression. While our research question primarily focused on quantitative analysis, we acknowledge the value of incorporating qualitative methods to provide richer insights into mental health issues among students. Lastly, reliance on self-reported data introduces inherent limitations, such as subjectivity and recall biases. Thus, acknowledging these limitations is crucial while interpreting the findings appropriately and understanding the scope and generalizability of the study's conclusions. Future research should address these limitations through longitudinal designs, more representative sampling techniques, and objective measures to strengthen the validity and reliability of the findings.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the mental health of university entrance test-takers, as evidenced by the higher prevalence of depression and anxiety found in this study compared to previous research. These findings emphasize the urgent need for targeted interventions to support the mental well-being of students facing academic stressors. Following are some specific recommendations that could mitigate the burden of mental health problems among university entrance students. The recommendations provide a comprehensive plan to address the pressing issue of mental health among university entrance test-takers. Reforms in the test-taking system, such as flexible formats and scheduling options, can alleviate stress. Besides, enhancing campus mental health support through counseling, peer programs, and staff training is crucial. Collaboration among stakeholders, including academic institutions and families, is essential for developing effective support programs. Conducting follow-up studies can offer insights into long-term mental health outcomes. Overall, implementing these recommendations can create a supportive environment for students, reducing the burden of mental health issues during the university entrance process.

Acknowledgements

MMA acknowledges funding support from Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University: Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R563), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

FAM and MM: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation. FAM, AMA, MMA, MM and MAM: writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing, visualization, validation supervision, software. All authors reviewed the final version and agreed for publication.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Mental disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (Accessed 4 Jul 2022) (2022).

- 2.World Health Organization. Mental health of adolescents. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health. (Accessed 10 May 2023) (2021)

- 3.Kazdin, A. E. Adolescent mental health. Prevention and treatment programs. Am. Psychol.48, 127–141. 10.1037/0003-066x.48.2.127 (1993). 10.1037/0003-066x.48.2.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet398, 1700–1712. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 (2021). 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosen, I., Al-Mamun, F. & Mamun, M. A. Prevalence and risk factors of the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Ment. Health8, e47. 10.1017/gmh.2021.49 (2021). 10.1017/gmh.2021.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moonajilin, M. S., Rahman, M. E. & Islam, M. S. Relationship between overweight/obesity and mental health disorders among Bangladeshi adolescents: A cross-sectional survey. Obes. Med.18, 100216. 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100216 (2020). 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehareen, J., Rahman, M. A., Dhira, T. A. & Sarker, A. R. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of depression, anxiety, and co-morbidity during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study among public and private university students of Bangladesh. J. Affect. Disord. Rep.5, 100179. 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100179 (2021). 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Mamun, F. et al. Mental disorders of Bangladeshi students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag.14, 645–654. 10.2147/PRBM.S315961 (2021). 10.2147/PRBM.S315961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]