Abstract

Background

The introduction of a noninvasive diagnostic algorithm in 2016 led to increased awareness and recognition of cardiac amyloidosis (CA).

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to analyze the impact of the introduction of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm on diagnosis and prognosis in a multicenter Italian CA cohort.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of 887 CA patients from 5 Italian Cardiomyopathies Referral Centers: 311 light-chain CA, 87 variant transthyretin (TTR)-related CA, 489 wild-type TTR-related CA. Clinical characteristics and outcomes (all-cause mortality and heart failure [HF] hospitalizations) were compared overall and for each CA subtype between patients diagnosed before versus after 2016. Outcomes were further compared by propensity score weighted Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression analysis.

Results

CA diagnoses increased after 2016, in particular for wild-type TTR-related CA. Patients diagnosed after versus before 2016 were older, had less frequently a history of HF prior to diagnosis, and NYHA functional class III-IV at diagnosis. Over a median follow-up of 18 months, 172 (86%) patients diagnosed before 2016 died or had an HF hospitalization, versus 300 (44%) diagnosed after 2016. Propensity score weighted Kaplan-Meier analysis showed worse outcomes (P < 0.001) for patients diagnosed before 2016. At Cox regression analysis, CA diagnosis after 2016 was an independent protective factor for the composite outcome (HR: 0.69; P = 0.001), with interaction by CA subtype (significant in TTR-related CA and null in light-chain).

Conclusions

CA patients diagnosed after 2016 showed a less severe phenotype and a better prognosis. The impact of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm on outcomes was particularly relevant in TTR-related CA.

Key words: AL cardiac amyloidosis, cardiac amyloidosis, heart failure, noninvasive diagnosis, transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis

Central Illustration

Over the last decades, the epidemiology of cardiac amyloidosis (CA), once defined as a rare and fatal disease, has rapidly evolved. In hospitalized patients aged more than 65 years, the incidence of CA has tripled from 2000 to 2012.1 While up to the first decade of 2000s the most known subtype of CA was that related to immunoglobulin light-chain (AL), in the last years an authentic exponential increase in the number of diagnoses of transthyretin (TTR)-related CA was witnessed.2 A fundamental turning point in the history of CA, leading to increased recognition and, thus, awareness of the disease, was represented by the introduction in 2016 of a noninvasive diagnostic algorithm by Gillmore and colleagues. By combining hematological exams (to rule out a monoclonal gammopathy) and technetium-labeled radionuclide bone scintigraphy, the algorithm allows a diagnosis of TTR-related CA without the need for histological confirmation in most of cases.3 Moreover, the emergence of novel disease-modifying therapies led to a further interest of the medical community toward CA, offering a potential cure for a disease once believed incurable.4 In AL, the combination of several drugs, as cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone, plus the recently introduced monoclonal antibody daratumumab, represents a first-line therapy which has shown to achieve a very good response in more than 70% of patients.5,6 In TTR-related CA, the TTR tetramer stabilizer tafamidis is the only approved agent shown to reduce mortality and morbidity.7 Other compounds that silence or block the synthesis of the TTR protein, as inotersen, patisiran, and the second-generation vutisiran, are currently under investigation.8 Mortality and morbidity, particularly related to heart failure (HF), however, remain high in CA.9,10

Most of contemporary epidemiological and clinical reports in CA have been provided by single-center experiences or insurance databases and were dedicated mainly to TTR-related CA. A study from the National Amyloid Center (NAC) in the United Kingdom showed that in the last 20 years patients with TTR-related CA were diagnosed earlier in the disease process and presented a significant improvement in outcomes.2 A Danish investigation based on data from national prescription registries evaluating all CA subtypes confirmed the increase of diagnoses, especially for TTR-related cases, with patients showing milder clinical characteristics than those of previous descriptions, and a reduction in mortality.11

The aim of this study was to analyze the impact of the introduction of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm on clinical characteristics at diagnosis and outcomes in a large, contemporary, real-world, nationwide CA cohort.

Methods

This study presents data from a CA registry set up by 5 Italian Regional Cardiomyopathies referral centers (Bologna, Ospedale Sant’Orsola, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna; Firenze, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Careggi; Genova, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino; Roma, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Sant’Andrea; Trieste, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano-Isontina), which maintains a longitudinal database capturing clinical and outcomes data of patients under care. All CA patients included in the registry between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2022, with available follow-up information were enrolled in the present study (n = 887). Institutional Review Board and ethics approval was obtained in accordance with policies applicable in each site.

Diagnosis of CA was made according to guidelines and recommendations contemporary to clinical practice.3,12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Diagnosis of AL was confirmed by biopsy of abdominal fat pad or of an involved organ with amyloid deposits characterized as AL type by immunohistochemistry, optic/immunoelectron microscopy, or proteomics. Before 2016, TTR-related CA was diagnosed on the basis of HF symptoms together with characteristic echocardiographic findings, and proof of TTR amyloid either on direct endomyocardial biopsy or in an extracardiac biopsy. After 2016, diagnosis of TTR-related CA was established according to the Gillmore algorithm.3 All patients with TTR-related CA, before and after 2016, underwent genetic sequencing of the TTR gene to distinguish variant TTR-related CA (ATTRv) and wild-type TTR-related CA (ATTRwt).

For AL patients, the 2004 Mayo score at diagnosis was calculated;17, 18, 19 for ATTRv and ATTRwt patients, the NAC score at diagnosis was calculated20—data to obtain the scores were available for 505 patients. The first version of Mayo score dated 2004, with the 2008 European update, was used to reflect the disease stage at cardiac level more accurately, as compared to the 2012 Mayo score.

Statistical methods

We compared patients, overall and in each CA subtype, according to year of diagnosis (before versus after January 1, 2016—the year of the publication of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm).3 Over a median follow-up of 18 (IQR: 8-33) months, we evaluated as outcomes all-cause mortality and HF hospitalizations, either as a composite event and separated. For the purposes of survival analyses, ATTRv and ATTRwt patients were grouped together (due to the small size of the first group). Median follow-up was not statistically different between patients diagnosed before versus after 2016, overall (before 2016: 14 [IQR: 5-60] months vs after 2016: 19 [IQR: 9-34], P = 0.90), in AL (before 2016: 12 [IQR: 4-43] months vs after 2016: 12 [IQR: 4-32], P = 0.52), in ATTRv (before 2016: 48 [IQR: 17-90] months vs after 2016: 31 [IQR: 15-48], P = 0.09), and in ATTRwt (before 2016: 27 [IQR: 10-65] months vs after 2016: 20 [IQR: 10-33], P = 0.10).

Results were presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and compared between 2 groups by using Student’s t-test. For continuous variables which were not normally distributed, IQRs (25th–75th percentiles) were used and groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were presented as n (%) and compared using chi-square tests.

After qualitative evaluation of proportional hazard (PH) using graphical method, univariable analysis with Cox PH regression model was performed to identify variable related to the composite outcome, all obtained Cox PH regression models received quantitative analysis of the residuals for PH condition confirmation, using Schoenfeld and Martingale residual tests. In order to rebalance selection bias, a propensity score (PS) for each patient was calculated using covariate balancing PS method that offered the best common support.21 The PS estimation included major confounding variables and risk factors: sex, age, weight, interventricular septum (IVS) thickness, left atrial diameter, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, natriuretic peptides values, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, restrictive filling pattern, moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation, left bundle branch block, low voltage at electrocardiogram (ECG), and treatment with disease-modifying therapies, Mayo or NAC score; the variables were chosen by clinical implications considering univariable analysis with P value <0.10.

After Kaplan-Meier PS-weighted (PSW) analysis for univariable binary variables and competing risk analysis for competing events (all-cause mortality for HF hospitalizations), performing log-rank or Gray tests, outcome comparison analysis was made by inverse probability of treatment weighting and for sensitivity analysis PS matching, performed using the 2:1 nearest neighbor matching method and a caliper width of 0.25 SDs (chosen after optimal matching and assessment of balance of covariates), “within group” matching, adopting random effect model for amyloidosis subtype and for hospital levels, for excluding bias due to underlying disease or epidemiologic variables.22 For inverse probability of treatment weighting survey-weighted mixed effect, Cox PH models were adopted, and the hospital centers were adopted as random variable for mixed effect. Univariable and multivariable for double-adjustment models23 were used to estimate the HRs and 95% CIs of the independent association between year of diagnosis and the composite outcome at 1 year.

After outcome analysis, PS sensitivity analyses were performed using Rosenbaum sensitivity test for PS matching and sensitivity analysis without assumptions of Vanderweele using E-value test for both models.24

Statistical analyses were performed with R software (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing), using as main packages: covariate balancing PS, CMatching, WeightIt, survival, survey, and coxme (The R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

The study included 887 CA patients, of which 311 (35%) with AL, 87 (10%) with ATTRv, and 489 (55%) with ATTRwt. There was a male predominance, overall and in each CA subtype. The mean age at diagnosis was 73 ± 10 years, with the older patients in the TTR-related CA subtypes (66 ± 11 in AL, 69 ± 12 in ATTRv, 78 ± 6 in ATTRwt). Overall and in each CA subtype, number of diagnoses increased over time (199 versus 688 CA patients diagnosed before versus after 2016); a steep surge in ATTRwt diagnoses was observed after 2016 (Figure 1). Supplemental Table 1 sums up characteristics at diagnosis of the overall cohort and of each CA subtype. Supplemental Table 2 illustrates distribution of TTR mutations in the ATTRv group. Supplemental Table 3 reports characteristics at diagnosis of patients divided by center.

Figure 1.

Number of CA Diagnoses Over Time, in the Overall Cohort and for Each CA Subtype

AL = light-chain; ATTRv = variant transthyretin-related CA; ATTRwt = wild-type transthyretin-related CA; CA = cardiac amyloidosis.

Differences in patients’ profile before versus after 2016

In the overall CA cohort, male predominance and age at diagnosis significantly increased after 2016 (Table 1). There was a greater prevalence of arterial hypertension and history of atrial fibrillation prior to diagnosis after 2016. A history of HF prior to diagnosis was less common and prevalence of NYHA functional class III-IV at diagnosis decreased after 2016. At ECG, low voltages were less common after 2016. At echocardiography, mean maximal IVS wall thickness was lower, LVEF and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion were higher, and a restrictive filling pattern was less common after 2016.

Table 1.

Characteristics of CA Patients Diagnosed Before vs After 2016

| Before 2016 (n = 199) | After 2016 (n = 688) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Males | 133 (67) | 559 (81) | |

| Females | 66 (33) | 129 (19) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 67 ± 11 | 75 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension | 96 (48) | 411 (60) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29 (15) | 98 (14) | 0.99 |

| CKD | 64 (32) | 206 (30) | 0.60 |

| History of CAD | 27 (14) | 106 (15) | 0.59 |

| History of HF prior to diagnosis | 145 (73) | 410 (60) | 0.001 |

| History of AF prior to diagnosis | 68 (34) | 302 (44) | 0.01 |

| History of PMK prior to diagnosis | 16 (8) | 90 (13) | 0.07 |

| History of ICD prior to diagnosis | 2 (1) | 20 (3) | 0.20 |

| Low voltages at ECG | 85 (48) | 200 (32) | <0.001 |

| LBBB | 12 (7) | 49 (8) | 0.82 |

| NYHA functional class at diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| I-II | 105 (58) | 497 (72) | |

| III-IV | 94 (47) | 191 (28) | |

| IVS (mm) | 18 ± 3 | 17 ± 3 | 0.02 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 47 ± 6 | 46 ± 6 | 0.44 |

| LVEF (%) | 48 ± 14 | 52 ± 11 | 0.003 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 14 ± 5 | 17 ± 5 | 0.007 |

| Restrictive filling pattern | 70 (44) | 195 (32) | <0.001 |

| Moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation | 37 (21) | 157 (23) | 0.53 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD. Significant P-values are indicated in bold.

AF = atrial fibrillation; CAD = coronary artery disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; ECG = electrocardiogram; HF = heart failure; ICD = implanted cardioverter defibrillator; IVS = interventricular septum; LA = left atrial; LBBB = left bundle branch block; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA = New York Heart Association; PMK = pacemaker; TAPSE = tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Among AL patients, a history of HF prior to diagnosis was less common and prevalence of NYHA functional class III-IV at diagnosis decreased after 2016 (Table 2). At echocardiography, mean maximal IVS wall thickness and left atrial diameter were lower, and a restrictive filling pattern was less common after 2016.

Table 2.

Characteristics of AL Patients Diagnosed Before vs After 2016

| Before 2016 (n = 145) | After 2016 (n = 166) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.81 | ||

| Males | 84 (58) | 94 (57) | |

| Females | 61 (42) | 72 (43) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 66 ± 11 | 67 ± 11 | 0.73 |

| Arterial hypertension | 62 (43) | 64 (39) | 0.45 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (12) | 17 (10) | 0.67 |

| CKD | 46 (32) | 50 (30) | 0.76 |

| History of CAD | 16 (11) | 18 (11) | 0.95 |

| History of HF prior to diagnosis | 113 (78) | 108 (65) | 0.01 |

| History of AF prior to diagnosis | 42 (29) | 36 (22) | 0.14 |

| History of PMK prior to diagnosis | 9 (6) | 9 (5) | 0.76 |

| History of ICD prior to diagnosis | 1 (1) | 6 (4) | 0.08 |

| Low voltages at ECG | 68 (54) | 81 (52) | 0.72 |

| LBBB | 4 (3) | 6 (4) | 1.00 |

| NYHA functional class at diagnosis | 0.01 | ||

| I-II | 67 (46) | 99 (56) | |

| III-IV | 78 (54) | 67 (40) | |

| IVS (mm) | 16 ± 3 | 15 ± 2 | 0.01 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 45 ± 8 | 43 ± 6 | 0.01 |

| LVEF (%) | 54 ± 12 | 56 ± 9 | 0.08 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 18 ± 5 | 18 ± 4 | 0.91 |

| Restrictive filling pattern | 52 (44) | 60 (41) | 0.04 |

| Moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation | 25 (20) | 40 (25) | 0.35 |

| Mayo scorea | 0.17 | ||

| I | 25 (27) | 33 (30) | |

| II | 26 (28) | 40 (37) | |

| III | 42 (45) | 36 (33) | |

| Treatment with bortezomib or daratumumab | 59 (41) | 103 (62) | <0.001 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD. Significant P-values are indicated in bold.

AL = light-chain; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Available for 202 patients.

Among ATTRv patients (Table 3), there were no significant differences between those diagnosed before versus after 2016, except for a lower male predominance in the latter group.

Table 3.

Characteristics of ATTRv Patients Diagnosed Before vs After 2016

| Before 2016 (n = 15) | After 2016 (n = 72) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.02 | ||

| Males | 15 (100) | 52 (72) | |

| Females | 0 | 20 (28) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 67 ± 14 | 69 ± 11 | 0.43 |

| Arterial hypertension | 7 (47) | 36 (50) | 0.81 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 9 (13) | 0.14 |

| CKD | 3 (20) | 10 (14) | 0.54 |

| History of CAD | 4 (27) | 8 (11) | 0.11 |

| History of HF prior to diagnosis | 6 (40) | 27 (38) | 0.85 |

| History of AF prior to diagnosis | 6 (40) | 19 (26) | 0.28 |

| History of PMK prior to diagnosis | 2 (13) | 9 (13) | 0.93 |

| History of ICD prior to diagnosis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0.64 |

| Low voltages at ECG | 5 (33) | 18 (27) | 0.82 |

| LBBB | 2 (13) | 4 (6) | 0.64 |

| NYHA functional class at diagnosis | 0.23 | ||

| I-II | 14 (93) | 58 (81) | |

| III-IV | 1 (7) | 14 (19) | |

| IVS (mm) | 17 ± 3 | 16 ± 4 | 0.34 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 44 ± 6 | 43 ± 5 | 0.81 |

| LVEF (%) | 53 ± 12 | 56 ± 10 | 0.37 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 16 ± 3 | 18 ± 5 | 0.34 |

| Restrictive filling pattern | 4 (37) | 14 (19) | 0.90 |

| Moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation | 3 (20) | 15 (21) | 1.00 |

| NAC scorea | 0.94 | ||

| I | 2 (67) | 27 (69) | |

| II | 1 (33) | 10 (26) | |

| III | 0 | 2 (5) | |

| Treatment with disease-modifying therapiesb | 5 (33) | 44 (61) | 0.05 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD. Significant P-values are indicated in bold.

ATTRv = variant transthyretin-related CA; NAC = National Amyloid Center; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Available for 42 patients.

Tafamidis, patisiran, or inotersen.

Among ATTRwt, age at diagnosis increased and prevalence of NYHA functional class III-IV at diagnosis decreased after 2016 (Table 4). At echocardiography, mean maximal IVS wall thickness was slightly lower, and a restrictive filling pattern was less common after 2016.

Table 4.

Characteristics of ATTRwt Patients Diagnosed Before vs After 2016

| Before 2016 (n = 39) | After 2016 (n = 450) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.32 | ||

| Males | 34 (87) | 413 (92) | |

| Females | 5 (13) | 37 (8) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 74 ± 8 | 79 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension | 27 (69) | 311 (69) | 0.98 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (31) | 72 (16) | 0.01 |

| CKD | 15 (39) | 146 (32) | 0.44 |

| History of CAD | 7 (18) | 80 (18) | 0.97 |

| History of HF prior to diagnosis | 26 (67) | 275 (61) | 0.49 |

| History of AF prior to diagnosis | 20 (51) | 247 (55) | 0.66 |

| History of PMK prior to diagnosis | 5 (13) | 72 (16) | 0.60 |

| History of ICD prior to diagnosis | 1 (3) | 13 (3) | 0.90 |

| Low voltages at ECG | 12 (32) | 101 (25) | 0.48 |

| LBBB | 6 (16) | 39 (10) | 0.37 |

| NYHA functional class at diagnosis | 0.05 | ||

| I-II | 24 (61) | 340 (76) | |

| III-IV | 15 (39) | 110 (24) | |

| IVS (mm) | 18 ± 4 | 17 ± 3 | 0.05 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 46 ± 6 | 47 ± 6 | 0.40 |

| LVEF (%) | 55 ± 11 | 54 ± 10 | 0.47 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 17 ± 2 | 18 ± 5 | 0.59 |

| Restrictive filling pattern | 14 (36) | 121 (27) | 0.003 |

| Moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation | 9 (24) | 102 (23) | 1.00 |

| NAC scorea | 0.13 | ||

| I | 9 (69) | 127 (51) | |

| II | 4 (31) | 94 (38) | |

| III | 0 | 27 (11) | |

| Treatment with tafamidis | 4 (10) | 64 (14) | 0.34 |

Clinical course before versus after 2016

In the overall CA cohort, over a median follow-up of 18 (IQR: 8-33) months, 172 (out of 199, 86%) patients diagnosed before 2016 died or had an HF hospitalization, versus 300 (44%) diagnosed after 2016. The number of events before and after 2016 is shown in Supplementary Figure 1, overall and for each CA subtype.

The hazard rate for the composite outcome at 1 year in the overall CA cohort was 0.61 for patients diagnosed before 2016 versus 0.22 for those diagnosed after 2016 (P < 0.001). Hazard rates for events before and after 2016 are shown in Table 5, overall, for AL and for ATTRv and ATTRwt grouped together.

Table 5.

Hazard Rates for Clinical Outcomes at 1-Year Before and After Propensity Weighting Analysis

| Unweighted |

Weighted |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 2016 | After 2016 | P Value | Before 2016 | After 2016 | P Value | |

| Overall CA | ||||||

| Composite outcome | 0.61 (0.49-0.75) | 0.22 (0.19-0.26) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.35-0.49) | 0.23 (0.19-0.26) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality | 0.46 (0.36-0.56) | 0.16 (0.13-0.19) | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.27-0.40) | 0.17 (0.14-0.20) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 0.50 (0.45-0.56) | 0.21 (0.19-0.24) | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.17-0.32) | 0.11 (0.08-0.15) | 0.01 |

| AL | ||||||

| Composite outcome | 0.73 (0.57-0.91) | 0.52 (0.40-0.65) | 0.04 | 0.51 (0.42-0.58) | 0.41 (0.33-0.48) | 0.35 |

| ATTR | ||||||

| Composite outcome | 0.36 (0.21-0.55) | 0.15 (0.12-0.18) | 0.002 | 0.29 (0.16-0.40) | 0.15 (0.11-0.17) | 0.03 |

| Composite outcome in ATTRwt | 0.42 (0.24-0.72) | 0.15 (0.12-0.20) | 0.001 | 0.36 (0.19-0.48) | 0.16 (0.13-0.20) | 0.02 |

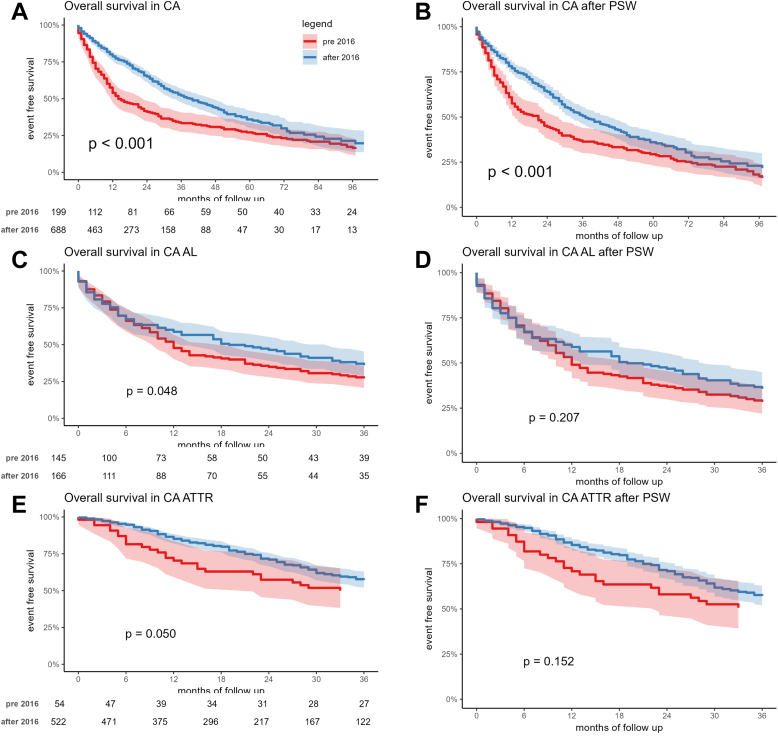

Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a worse survival free from the composite outcome, from all-cause mortality, and from HF hospitalization (respectively, log-rank tests P < 0.001, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001) for patients diagnosed before versus after 2016 in the overall CA cohort (Figure 2A, Supplemental Figure 2A and 2C), in AL (Figure 2C) (P = 0.048), and in ATTRv and ATTRwt grouped together (Figure 2E) (log-rank tests P = 0.050).

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier Curves for the Composite Outcome

Kaplan-Meier curves for the composite outcome in the overall CA cohort before (A) and after (B) PSW, in the AL group before (C) and after (D) PSW, and in the TTR group before (E) and after (F) PSW. PSW = propensity score weighted; TTR = transthyretin; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Propensity score weighted survival analysis

As shown in Table 5, after PSW analysis, the hazard rate for the composite outcome at 1 year in the overall CA cohort was 0.42 for patients diagnosed before 2016 versus 0.23 for those diagnosed after 2016 (P < 0.001). The hazard rates for all-cause mortality (0.33 vs 0.17; P < 0.001) and HF hospitalization (0.25 vs 0.11; P = 0.01) at 1 year remained significantly greater in patients diagnosed before versus after 2016. Moreover, in ATTRv and ATTRwt grouped together, the hazard rate for the composite outcome was significantly greater in those diagnosed before versus after 2016 (0.29 vs 0.15; P = 0.03), whereas in AL it decreased in those diagnosed after 2016, but without reaching statistical significance (0.51 vs 0.41, P = 0.35). The hazard rate for the composite outcome was significantly greater before versus after 2016 also when analyzing ATTRwt alone.

New Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed a worse survival free from the composite outcome, from all-cause mortality, and from HF hospitalization (respectively, log-rank tests P < 0.001, P < 0.001 and P = 0.02) for patients diagnosed before versus after 2016 in the overall CA cohort (Figure 2B, Supplemental Figure 2B and 2D). Survival free from the composite outcome before versus after 2016 was not significantly different in AL (Figure 2D) (log-rank tests P = 0.21) and in ATTRv and ATTRwt grouped together (Figure 2F) (P log = 0.15).

At multivariable Cox regression analysis (Supplementary Figure 3), CA diagnosis after 2016 was a protective factor for the composite outcome (HR: 0.72 [95% CI: 0.53-0.97], P = 0.03), as were female sex (HR: 0.62 [95% CI: 0.43-0.89], P = 0.01) and treatment with disease-modifying therapies (HR: 0.69 [95% CI: 0.50-0.93], P = 0.02), whereas NYHA functional class III/IV (HR: 1.71 [95% CI: 1.39-2.10], P < 0.0001), maximal IVS wall thickness (HR: 1.05 [95% CI: 1.01-1.08], p 0.01), left bundle branch block (HR: 1.57 [95% CI: 1.18-2.08], p 0.002), AL subtype (HR: 2.92 [95% CI: 2.09-4.90], P < 0.0001) were risk factors. There was a significant interaction between year of diagnosis (ie, CA diagnosis before versus after 2016) and CA subtype. The favorable impact conferred by a diagnosis after 2016 appeared significant in ATTRv and ATTRwt grouped together (HR: 0.51 [95% CI: 0.41-0.63], P < 0.0001), while its influence was null in AL (HR: 0.96 [95% CI: 0.75-1.23], P = 0.73). Sensitivity analysis showed an E value of about 1.91, meaning that an unobserved variable would need to be about double in one arm and to have about double protective power in respect to year of diagnosis, to make the last one no more significant.

Discussion

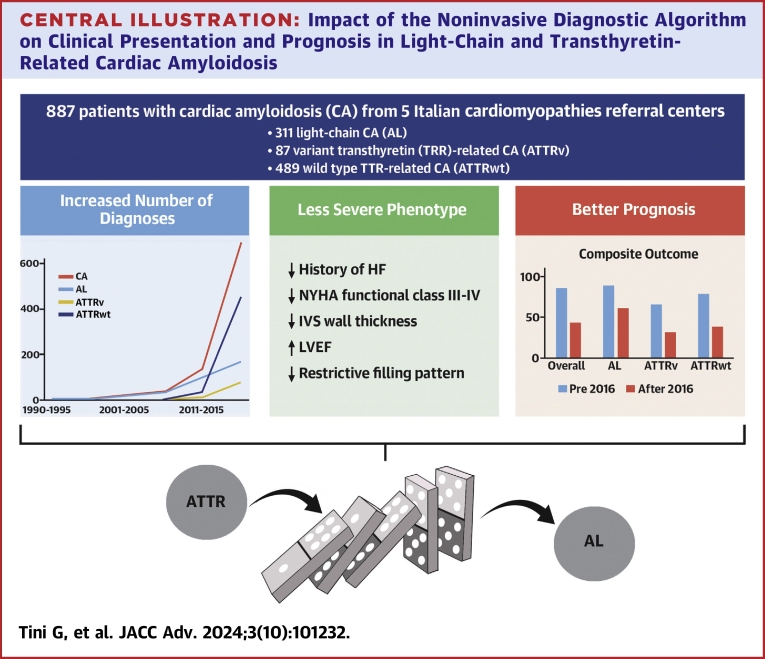

Our multicentric, real-world, nationwide investigation depicts the evolving landscape of CA in Italy over the last 30 years. Findings of our study demonstrate that the introduction of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm3 represented a turning point in the history of CA, with a significant impact on: 1) number of CA diagnoses; 2) patients’ presenting features; and 3) prognosis, especially in the short term (Central Illustration).

Central Illustration.

Impact of the Noninvasive Diagnostic Algorithm on Clinical Presentation and Prognosis in Light-Chain and Transthyretin-Related Cardiac Amyloidosis

Evolving landscape of CA after the introduction of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm: Increased number of diagnoses, less severe phenotype at diagnosis, better short-term prognosis. The impact of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm onto the TTR-related CA group diagnoses and features influenced the AL group as well with a “Domino-Effect”. HF = heart failure; IVS = interventricular septum; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

A significant surge in the number of diagnoses, already described for TTR-related CA,1,9,11,25, 26, 27, 28, 29 is confirmed in our Italian cohort. We found an increase of the overall number of CA diagnoses after the year 2016 greater than 250%. This was primarily driven by ATTRwt, but all CA subtypes showed an increase in the number of newly identified patients (Figure 1). Such a trend demonstrates the increased cultural sensibility toward CA, a disease once considered of minor interest for cardiologists, and mostly managed exclusively by other clinicians (ie, hematologists and neurologists).15,30 In recent years, the implementation and diffusion of a cardiomyopathy mindset and of a red-flags diagnostic approach,31 paved the way for a cardiologic reappraisal of CA, and hence for the fundamental development of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm.3,32,33 Cardiomyopathy centers have since witnessed CA progressively becoming one of the most prevalent diagnosis in their cohorts.34

Moreover, clinical characteristics at diagnosis of CA patients significantly changed over time. Those diagnosed after 2016 were older and less symptomatic; had less frequently low voltages at ECG; had lower maximal IVS wall thickness values, greater LVEF and less commonly a restrictive filling pattern at echocardiography, as compared to patients diagnosed before 2016. While in the small group of ATTRv no differences were highlighted in the two time periods, in the larger AL and ATTRwt groups these results were confirmed. Overall, these clinical, ECG35 and echocardiographic36,37 features are consistent with a less severe disease phenotype in patients diagnosed after 2016. This changing scenario is likely to be ascribed to an improved (ie, “easier”) diagnostic approach, allowing to reach a diagnosis earlier in the disease process, sometimes even in an incidental manner.29,38 As this has been clearly demonstrated for TTR-related CA, it is interesting to note this trend also in AL. The focus toward TTR-related CA in recent years is responsible for a “domino-effect,” by which AL cases were more easily unveiled as well, thanks to the standardized39 diagnostic algorithm (in that hematologic exams are always needed to reach the final diagnosis).

Differences between patients diagnosed before versus after 2016 were also observed in outcomes. Despite a similar follow-up time in the two groups, we found that the absolute number of events dramatically decreased after 2016, overall and in each CA subtype, both for mortality and morbidity. About 90% of our CA patients diagnosed before 2016 experienced death or an HF hospitalization in their clinical course, as compared to less than 50% of those diagnosed after 2016, and such reduction was consistent in all CA subtypes. Notably, clinical benefit was evident early, with a separation of the curves in the first year at Kaplan-Meier analysis. Indeed, the risk for the composite outcome fell of about 40% in the first year in the overall CA cohort, and of 20% in each CA subtype (Table 5). This dramatic change in CA prognosis was surely influenced by the introduction of disease-modifying therapies, in both AL and TTR-related CA. Nevertheless, to minimize confounding bias, we performed a PSW analysis, that confirmed the significant impact of the introduction of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm (ie, a CA diagnosis after 2016) on outcomes in the overall CA cohort. A significant interaction between year of diagnosis and CA subtype was observed, and the positive impact of the introduction of the Gillmore algorithm was evident only for TTR-related CA patients. Remarkably, however, a diagnosis after 2016 was significantly associated with a more favorable outcome independently from clinical characteristics and disease-modifying therapies. This finding further highlights how the introduction of a standardized diagnostic approach to CA, achieved over years of intensive interest and research, translated not only into more diagnoses but also into an improved clinical and therapeutic patient management. Finally, it is of note that variables negatively and independently associated with prognosis were echocardiographic, electrocardiographic, and clinical (ie, a NYHA functional class III-IV) related to an advanced disease. This is clinically relevant, as an advanced NYHA functional class at diagnosis was still found in one-third of patients diagnosed after 2016, underlying how efforts to reach earlier CA diagnosis are still needed. It also highlights the complex management of this group of patients, who have limited access to disease-modifying therapies and advanced HF treatments.7,29,40,41

Study Limitations

The number of TTR-related CA patients (in particular ATTRwt) diagnosed before 2016 in our study was limited. Mayo and NAC scores were available for 60% of patients, mostly due to the different assays for natriuretic peptides and troponin used in and within each center over time. Both facts may, at least in part, explain the absence of differences in Mayo and NAC scores before versus after 2016 in our AL and TTR-related CA cohort. Median follow-up duration was relatively short, possibly influencing number of events especially for those patients most recently diagnosed. Nevertheless, follow-up duration was one of the variables considered in the PW analysis. Despite these shortcomings, our study presents one of the few examples of a large CA cohort, encompassing 30 years of dedicated clinical experience from a nationwide collaboration between 5 Cardiomyopathy Referral centers across different regions of Italy, each one linked with a network of spoke sites in less central areas.

Conclusions

After the introduction into clinical practice of the noninvasive diagnostic algorithm, CA diagnoses have increased, overall and in each subtype, with the greatest increase seen in ATTRwt. Patients diagnosed after 2016 showed a less severe disease phenotype and a better prognosis, especially in the short term (ie, first year). The significant impact of the Gillmore algorithm on outcomes is particularly relevant in TTR-related CA, likely due to a heightened awareness and a proactive approach toward the disease.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: The introduction of a noninvasive diagnostic algorithm in CA led to an increase in the number of diagnoses and to the identification of patients with less severe phenotypes at presentation, both in AL and TTR-related CA. Similarly, patients diagnosed after 2016 showed better outcomes.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: A dramatic reduction in the rate of adverse outcomes was observed in CA, especially in the short term. Awareness of evolving clinical presentation and outcomes may not only improve management of CA patients but also inform current and future trials design and interpretation.

Funding support and author disclosures

The work reported in this publication was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, RC-2022-2773270 project. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Gilstrap L.G., Dominici F., Wang Y., et al. Epidemiology of cardiac amyloidosis-associated heart failure hospitalizations among fee-for-service medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannou A., Patel R.K., Razvi Y., et al. Impact of earlier diagnosis in cardiac ATTR amyloidosis over the course of 20 years. Circulation. 2022;146:1657–1670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillmore J.D., Maurer M.S., Falk R.H., et al. Nonbiopsy diagnosis of cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016;133:2404–2412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin J.M., Rosenblum H., Maurer M.S. Pathophysiology and therapeutic approaches to cardiac amyloidosis. Circ Res. 2021;128:1554–1575. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett C.D., Dobos K., Liedtke M., et al. A changing landscape of mortality for systemic light chain amyloidosis. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:958–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palladini G., Kastritis E., Maurer M.S., et al. Daratumumab plus CyBorD for patients with newly diagnosed AL amyloidosis: safety run-in results of ANDROMEDA. Blood. 2020;136:71–80. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maurer M.S., Schwartz J.H., Gundapaneni B., et al. Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1007–1016. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quarta C.C., Fontana M., Damy T., et al. Changing paradigm in the treatment of amyloidosis: from disease-modifying drugs to anti-fibril therapy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1073503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauppe R., Liseth Hansen J., Fornwall A., et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and mortality of patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in the Nordic countries. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9:2528–2537. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palladini G., Schönland S., Merlini G., et al. The management of light chain (AL) amyloidosis in Europe: clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and efficacy outcomes between 2004 and 2018. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:19. doi: 10.1038/s41408-023-00789-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westin O., Butt J.H., Gustafsson F., et al. Two decades of cardiac amyloidosis: a Danish nationwide study. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3:522–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gertz M.A., Comenzo R., Falk R.H., et al. Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis. Am J Hematol. 2005;79:319–328. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gertz M.A., Benson M.D., Dyck P.J., et al. Diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy of transthyretin amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2451–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gertz M.A. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: 2020 update on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:848–860. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapezzi C., Merlini G., Quarta C.C., et al. Systemic cardiac amyloidoses: disease profiles and clinical courses of the 3 main types. Circulation. 2009;120:1203–1212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.843334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorbala S., Ando Y., Bokhari S., et al. ASNC/AHA/ASE/EANM/HFSA/ISA/SCMR/SNMMI expert consensus recommendations for multimodality imaging in cardiac amyloidosis: Part 2 of 2—diagnostic criteria and appropriate utilization. J Card Fail. 2019;25:854–865. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber N., Mollee P., Augustson B., et al. Management of systemic AL amyloidosis: recommendations of the myeloma foundation of Australia medical and scientific advisory group. Intern Med J. 2015;45:371–382. doi: 10.1111/imj.12566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dispenzieri A., Gertz M.A., Kyle R.A., et al. Serum cardiac troponins and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide: a staging system for primary systemic amyloidosis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3751–3757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palladini G., Foli A., Milani P., et al. Best use of cardiac biomarkers in patients with AL amyloidosis and renal failure. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:465–471. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillmore J.D., Damy T., Fontana M., et al. A new staging system for cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2799–2806. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan J., Imai K., Lee I., Liu H., Ning Y., Yang X. Optimal covariate balancing conditions in propensity score estimation. J Bus Econ Stat. 2023;41:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuentes A., Lüdtke O., Robitzsch A. Causal inference with multilevel data: a comparison of different propensity score weighting approaches. Multivar Behav Res. 2022;57:916–939. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2021.1925521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin P.C. Double propensity-score adjustment: a solution to design bias or bias due to incomplete matching. Stat Methods Med Res. 2017;26:201–222. doi: 10.1177/0962280214543508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cinelli C., Hazlett C. Making sense of sensitivity: extending omitted variable bias. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 2020;82:39–67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zampieri M., Nardi G., Del Monaco G., et al. Changes in the perceived epidemiology of amyloidosis: 20 year-experience from a tertiary referral centre in tuscany. Int J Cardiol. 2021;335:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porcari A., Allegro V., Saro R., et al. Evolving trends in epidemiology and natural history of cardiac amyloidosis: 30-year experience from a tertiary referral center for cardiomyopathies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1026440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane T., Fontana M., Martinez-Naharro A., et al. Natural history, quality of life, and outcome in cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. Circulation. 2019;140:16–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nativi-Nicolau J., Siu A., Dispenzieri A., et al. Temporal trends of wild-type transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in the transthyretin amyloidosis outcomes survey. JACC CardioOncology. 2021;3:537–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2021.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tini G., Milani P., Zampieri M., et al. Diagnostic pathways to wild-type transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: a multicentre network study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:845–853. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapezzi C., Lorenzini M., Longhi S., et al. Cardiac amyloidosis: the great pretender. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20:117–124. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapezzi C., Arbustini E., Caforio A.L.P., et al. Diagnostic work-up in cardiomyopathies: bridging the gap between clinical phenotypes and final diagnosis. A position statement from the ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1448–1458. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perugini E., Guidalotti P.L., Salvi F., et al. Noninvasive etiologic diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis using 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid scintigraphy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapezzi C., Quarta C.C., Guidalotti P.L., et al. Role of 99mTc-DPD scintigraphy in diagnosis and prognosis of hereditary transthyretin-related cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damy T., Zaroui A., De Tournemire M., et al. Changes in amyloidosis phenotype over 11 years in a cardiac amyloidosis referral centre cohort in France. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;116:433–446. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2023.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cipriani A., De Michieli L., Porcari A., et al. Low QRS voltages in cardiac amyloidosis: clinical correlates and prognostic value. JACC CardioOncology. 2022;4:458–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2022.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aimo A., Tomasoni D., Porcari A., et al. Left ventricular wall thickness and severity of cardiac disease in women and men with transthyretin amyloidosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:510–514. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar S., Dispenzieri A., Lacy M.Q., et al. Revised prognostic staging system for light chain amyloidosis incorporating cardiac biomarkers and serum free light chain measurements. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:989–995. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merlo M., Pagura L., Porcari A., et al. Unmasking the prevalence of amyloid cardiomyopathy in the real world: results from Phase 2 of the AC-TIVE study, an Italian nationwide survey. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;13:2022. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rauf M.U., Hawkins P.N., Cappelli F., et al. Tc-99m labelled bone scintigraphy in suspected cardiac amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:2187–2198. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maroun B.Z., Allam S., Chaulagain C.P. Multidisciplinary supportive care in systemic light chain amyloidosis. Blood Res. 2022;57:106–116. doi: 10.5045/br.2022.2021227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Razvi Y., Porcari A., Di Nora C., et al. Cardiac transplantation in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: outcomes from three decades of tertiary center experience. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1075806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.