Visual Abstract

Key Words: β1-adrenoceptor, contractility, heart failure, myofilament, myosin light chain, nitric oxide synthetase, protein kinase G

Highlights

-

•

Carvedilol induces β1AR coupling to NOS3 to promote myofilament PKG1 signaling.

-

•

Myofilament PKG1 promotes the phosphorylation of MYPT1 and MLC.

-

•

The myofilament PKG1 enhances EC coupling without increase in cellular calcium.

-

•

In human and mouse HF, cardiac β1AR switches coupling from NOS1 to NOS3.

-

•

Targeting the myofilament β1AR-NOS3-PKG1 enhances contractility in ischemic heart.

Summary

Phosphorylation of myofilament proteins critically regulates beat-to-beat cardiac contraction and is typically altered in heart failure (HF). β-Adrenergic activation induces phosphorylation in numerous substrates at the myofilament. Nevertheless, how cardiac β-adrenoceptors (βARs) signal to the myofilament in healthy and diseased hearts remains poorly understood. The aim of this study was to uncover the spatiotemporal regulation of local βAR signaling at the myofilament and thus identify a potential therapeutic target for HF. Phosphoproteomic analysis of substrate phosphorylation induced by different βAR ligands in mouse hearts was performed. Genetically encoded biosensors were used to characterize cyclic adenosine and guanosine monophosphate signaling and the impacts on excitation-contraction coupling induced by β1AR ligands at both the cardiomyocyte and whole-heart levels. Myofilament signaling circuitry was identified, including protein kinase G1 (PKG1)–dependent phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase, myosin phosphatase target subunit 1, and myosin light chain at the myofilaments. The increased phosphorylation of myosin light chain enhances cardiac contractility, with a minimal increase in calcium (Ca2+) cycling. This myofilament signaling paradigm is promoted by carvedilol-induced β1AR–nitric oxide synthetase 3 (NOS3)–dependent cyclic guanosine monophosphate signaling, drawing a parallel to the β1AR–cyclic adenosine monophosphate–protein kinase A pathway. In patients with HF and a mouse HF model of myocardial infarction, increasing expression and association of NOS3 with β1AR were observed. Stimulating β1AR-NOS3-PKG1 signaling increased cardiac contraction in the mouse HF model. This research has characterized myofilament β1AR-PKG1-dependent signaling circuitry to increase phosphorylation of myosin light chain and enhance cardiac contractility, with a minimal increase in Ca2+ cycling. The present findings raise the possibility of targeting this myofilament signaling circuitry for treatment of patients with HF.

As the central contractile apparatus within cardiac muscle cells, myofilaments play a pivotal role in signal reception and transduction in healthy and diseased hearts.1,2 Protein phosphorylation is a rapid and crucial mechanism to control myofilament function and is commonly dysregulated in heart failure (HF). Reduction in the phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain (MLC) has emerged as a key event contributing to the contractile dysfunction of ischemic and hypertrophic failing hearts,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 yet the underlying molecular signaling remain elusive. Cardiac β-adrenoceptor (βAR) signaling to the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)–protein kinase A (PKA) pathway is recognized as the primary driving force for activating ion channels and transporters and increasing calcium (Ca2+) cycling to promote contractile force and cardiac output.8, 9, 10 Although the β-adrenergic regulation of Ca2+ cycling is well established, how βAR regulates signaling on the myofilaments is less understood. There has been growing clinical interest in therapeutics that modulate the myofilaments for HF treatment.11,12 Thus, it is imperative to understand the regulation of βAR signaling to the myofilaments in physiological and disease settings.

By using subcellular-localized fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET)–based biosensors to measure cAMP-PKA activity, recent studies have illuminated distinct local cAMP-PKA signaling at the myofilaments and the sarcoplasmic reticulum.13,14 Precise coordination of substrate phosphorylation is indispensable for increasing cardiac excitation-contraction coupling, whereas a simple increase in a particular substrate phosphorylation, such as myofilament binding protein C, is not sufficient to lead to a greater increase in excitation-contraction coupling.13 Furthermore, phosphodiesterase isoforms differentially regulate local cAMP-PKA signals in healthy and diseased hearts. A recent study demonstrated that direct inhibition of phosphodiesterase 1 leads to increased sarcomere shortening in cardiomyocytes, with moderate increases in Ca2+ transient.15 Similarly, we have recently shown that stimulation of β1AR can drive a cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)–protein kinase G (PKG)–mediated increase in myocyte sarcomere shortening, with little change in Ca2+ transient.16 These findings suggest that selective targeting of the myofilament signaling circuitry may increase cardiac contractility. Such a strategy could offer a promising HF therapy with fewer side effects associated with increases in Ca2+ cycling.

In this study, we used unbiased phosphoproteomic discovery and identified a concerted PKG1-dependent signaling network in the myofilaments, including MLC kinase (MLCK), MLC2, and myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1; also known as PPP1r12a), a phosphatase that controls MLC phosphorylation.17 The phosphorylated MLC enhances Ca2+ sensitivity and cross-bridging, which promotes contractile shortening.18 We demonstrated that a β1AR–Gi–protein kinase B (Akt)–nitric oxide synthetase 3 (NOS3) signaling pathway triggered PKG1-dependent phosphorylation of MLC2 and MYPT1, thereby enhancing cardiac contractile shortening with a minimal increase in Ca2+ cycling. This myofilament signaling paradigm draws a parallel to the β1AR-cAMP-PKA pathway, which augments both Ca2+ cycling and contractility. Intriguingly, we also observed elevated expression of NOS3 and its association with β1AR in a mouse model of HF and in human HF. Manipulating the β1AR-NOS3-PKG1 signaling pathway improved myocyte sarcomere shortening and cardiac ejection fraction (EF) in failing hearts with myocardial infarction. Our data uncover novel myofilament-based PKG1-MLCK-MPYT-MLC signaling circuitry to enhance cardiac contractility in HF.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J wild-type (WT), β1AR-knockout (KO),19 NOS1-KO,20 NOS3-KO,21 and PKG2-KO22 mice have been characterized previously and were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. PKG1-flox mice, described previously,23 were crossed with MHC-cre (IMSR_JAX:009074) to generate PKG1–conditional KO mice. Male and female mice (2-4 months of age) and New Zealand white rabbits (3-6 months of age) were used in this study. All animals were housed in specific pathogen–free conditions at 22 °C with a light/dark cycle of 12 hours and monitored per ethical guidelines. All operations were conducted following the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments and National Institutes of Health guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocols 20957 and 20234) at the University of California-Davis.

Reagents

(−)-Isoproterenol hydrochloride (I6504), dobutamine hydrochloride (D0676), Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (N5751-5G), carvedilol (C3993-250MG), metoprolol tartrate salt (M5391-1G), ICI-118,551 hydrochloride (I127-5MG), and CGP-20712A methane-sulfonate salt (C231-10MG) (all from Sigma-Aldrich); pertussis toxin (179B, List Biological Laboratories); LY-294002 (ST-420, Biomol); and MK-2206 (S1078, Selleck Chemicals) were used in this study.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Forty milligrams of mouse heart tissue was homogenized by 2 mL lysis buffer (25 mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.4], 5 mmol/L EDTA, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors including 2 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mmol/L NaF, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 mmol/L bestatin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, and 2 μg/mL pepstatin A) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was precleared by 10 μL Protein A-Sepharose beads (GE17-0780-01, Millipore) and 0.1 μg immunoglobulin G antibody (sc-66931, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The precleared supernatant (1 mL) was then incubated with 30 μL Protein A-Sepharose beads and 2 μg anti-β1AR (sc-568, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti–immunoglobulin G antibody overnight at 4 °C. Bead-bound proteins were then solubilized with 2 × sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer (161-0747, Bio-Rad Laboratories) for electrophoresis.

Proximity ligation assay

Adult ventricular myocytes (AVMs) from WT, NOS3-KO, and NOS1-KO mice were subjected to the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) using Duolink kit (DUO92101, Sigma-Aldrich). Two proteins within proximity (<40 nm) will be detected.24 Briefly, freshly isolated AVMs were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked as described previously. Then, AVMs were incubated with antibodies against β1AR (rabbit, 1:100; SC-568, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) plus NOS1 (mouse, 1:100; sc-5302, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or NOS3 (mouse, 1:100; sc-376751, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) control immunoglobulin G (mouse, 1:100; sc-2025, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by PLUS/MINUS secondary antibodies, PLA probe ligation, and polymerase amplification. After amplification, cells were mounted and visualized using a TCS SP8 Falcon confocal microscope (Leica) in TCS8 mode. Z-stack confocal images were obtained at 405-nm excitation for 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and 555-nm excitation for PLA-positive signals. Three-dimensional images of AVMs with PLA dots were processed and analyzed using LAS X version 3.0 (Leica Microsystems) and ImageJ.

Tissue collection and AVM isolation

Mice were sacrificed under anesthetization with 3% isoflurane. Hearts were quickly excised and perfused on a Langendorff perfusion apparatus with isoproterenol (0.1 mmol/L), dobutamine (1 µmol/L), or carvedilol (1 µmol/L). After 10 minutes of drug stimulation, the left ventricle was quickly excised for biochemistry and proteomic analyses.

Isolation of mouse AVMs was conducted as previously described.16 Hearts were perfused on a Langendorff perfusion apparatus with a mixed collagenase and protease solution (0.1 mg/mL protease IX and 0.5 mg/mL collagenase). After digestion, the left ventricle was dissociated into single cells. Suspended AVMs were subjected to a serial Ca2+ recovery solution before assay.

Contractility and Ca2+ imaging

AVM contraction and Ca2+ imaging were performed as previously described.16 Freshly isolated AVMs were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 (2 mmol/L). AVMs were treated with β-blockers or agonists under 1-Hz electric pacing at 50 V. Cell length and Ca2+ transient before and after stimulation were recorded simultaneously using a Zeiss AX10 microscope. The percentage of sarcomere length shortening was analyzed using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). The Ca2+ transient analysis was calculated using Gai Lab custom-written software (Interactive Data Language, ITT).

FRET assay

Isolated AVMs expressing biosensors (A kinase activity reporter for PKA, Gi500 for cGMP, and H187 for cAMP) were used in this assay. A kinase activity reporter, H187, and Gi500 have been reported previously.25,26 AVMs were infected with A kinase activity reporter, H187, and Gi500 recombinant adenovirus and then subjected to FRET recording. FRET images were recorded on an inverted Zeiss AX10 microscope with MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices). FRET images of cyan fluorescent protein and yellow fluorescent protein were acquired as previously described and analyzed using MATLAB. The Δ cyan fluorescent protein/yellow fluorescent protein ratio was calculated and normalized to baseline.26

Human left ventricular tissues

Left ventricular myocardium from nonfailing hearts from brain-dead donors with no histories of heart diseases but unsuitable for heart transplantation were used as control tissues in this study. The donor heart tissues were obtained from University of Wisconsin Organ and Tissue Donation. The HF tissue samples were collected from the explanted failing hearts of transplant recipients with informed consent from patients. The use of human heart tissue samples was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. All tissue samples were excised from the free wall of the left ventricle, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Heart tissues were lysed in HEPES buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors before applying to western blots.

Western blot

Left ventricular tissues were homogenized as previously reported.25 Protein supernatants were solved on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and detected with anti-NOS3 (1:1,000; 9572, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-NOS3 serine 1177 (1:1,000; 9571, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-β1AR (1:500; SC-568, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (1:500; SC-46668, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti–phospho–vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein serine 157 (1:500; 3111, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–phospho–vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein serine 239 (1:500; 3114, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-phospholamban serine 16 (1:1,000; 14388. Abmart), anti-phospholamban (1:1,000; DAM1641081, Millipore), anti–phospho–ryanodine receptor serine 2808 (1:1,000; Ab59225, Abcam), anti–ryanodine receptor 2 (1:1,000; 9765-1-AP, Invitrogen), anti-phosphor-Cav1.2 serine 1928 (1:1,000; 25787-1, Abmart), anti-Cav1.2 (1:500; 75-257, NeuroMab), anti–phospho–troponin I serine 23/24 (1:500; 4004S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti–troponin I (1:1,000; 4002, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-MYPT1 (1:500; 8574, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-Akt2 serine 474 (1:1,000; 8599, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-Akt1 serine 473 (1:1,000; 9018, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Akt (1:1,000; sc-81434, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-phospho-MYPT1 serine 507 (1:500; 3040, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-MYPT1 threonine 696 (5163, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-phospho-MYPT1 threonine 853 (1:500; 4563, Cell Signaling Technology). All primary antibodies were then revealed by IRDye 800 CW goat secondary antibodies using ChemiDoc MP Imagers (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The intensity was analyzed using ImageJ.

TMT phosphoproteomic analysis

Heart tissues were lysed by Douncing in ice-cold lysis buffer (6 M guanidine HCl, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor cocktail [S8830, Sigma-Aldrich], and PhosSTOP [04906837001, Roche]). A total of 400 μg of protein was used for phosphoproteomic analysis. Digested peptides were labeled with TMT6plex (lot UF288619, Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Five percent of the sample was saved for proteomic analysis, and the rest of the fractions were dried completely using a speed vacuum for phosphopeptide enrichment. Immobilized metal affinity chromatography enrichment of phosphopeptides was adapted from Mertins et al27 with modifications. The enriched phosphopeptides were further desalted using Empore C18 (2215, 3M) StageTip before nano–liquid chromatographic/tandem mass spectrometric analysis.28

Nano–liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry was performed using a Dionex rapid separation liquid chromatographic system with an Eclipse (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Phosphorylation on serine, threonine, and tyrosine was also considered for dynamic modification when phosphoproteomic data were searched. Percolator was used for result validation. A concatenated reverse database was used for the target-decoy strategy. High confidence for proteins and peptides was defined as a false discovery rate of <0.01, and medium confidence was defined as a false discovery rate of <0.05. Values were corrected for the isotopic impurity of reporter ions. The abundance was further normalized to the summed abundance value for each channel overall peptides identified within a file.

Protein and phosphopeptide results were exported from Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and further analyzed using Perseus version 1.6.10.43 (MaxQuant). Groups were compared using Student’s t-test with equal variance, requiring 2 valid total values. The q value was calculated using a permutation test. Enrichment analysis was performed for the differentially phosphorylated proteins using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery version 6.8.29 The heat map was generated in R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Echocardiography

Mice were anesthetized with 1% to 2% isoflurane and imaged using the Vevo 2100 Imaging System with a 22- to 55-MHz MS550D linear probe (VisualSonics). Mice were monitored with body temperature, respiratory rate, and electrocardiography. Ventricular imaging was performed using M-mode, short-axis echocardiography before and after intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg/kg isoproterenol, dobutamine, or carvedilol.30

Myocardial infarction and long-term isoproterenol infusion

Two- to three-month-old male mice were used to perform left anterior descending coronary artery ligation surgery, as previously described.31 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% for induction and 2%-3% for maintenance) in pure oxygen flow (0.8 L/min). Ventilation was applied at a respiratory rate of 110 to 130 breaths/min and a tidal volume of 0.2 mL. While monitoring the electrocardiogram, the chest cavity was opened to visualize the heart. Then, the left anterior descending coronary artery was identified under a surgical microscope and ligated using an 8-0 suture for 30% to 40% infarction of the left ventricle. Electrocardiography confirmed the establishment of infarction. Analgesia (buprenorphine 0.1 mg/kg) was given immediately after surgery and after recovery. Cardiac function was measured on echocardiography to confirm the myocardial infarction model.

Two- to three-month-old WT male mice were subjected to 14 days of isoproterenol or intraperitoneal saline injection, as previously reported.32 Cardiac function before and after 14 days of treatment (60 mg/kg isoproterenol or saline) was measured using echocardiography.

cAMP and cGMP measurement

Isolated AVMs from WT mice were added to 96-well plates (4,000 cells/well). Cells were treated with vehicle control, (−)-isoproterenol hydrochloride (100 nmol/L), dobutamine (1 μmol/L), and carvedilol (1 μmol/L, 10 minutes) per the manufacturer’s protocol (cAMP Glo Max Assay TM347, Promega). Ten microliters of 5× cAMP detection solution was added to each well and then incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Finally, 10 μL Kinase-Glo reagent (Promega) was added into the wells and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. The luminescence output of each well was detected using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices).

The cGMP level of isolated AVMs (10,000 cells/well) after vehicle control, (−)-isoproterenol hydrochloride (100 nmol/L), dobutamine (1 μmol/L), and carvedilol (1 μmol/L, 10 minutes) stimulation was assessed using the Cyclic GMP Complete ELISA Kit (ab133052, Abcam). Briefly, 100 μL of the supernatant, 50 μL Cyclic GMP Complete alkaline phosphatase conjugate, and 50 μL Cyclic GMP Complete antibody were pipetted into the appropriate wells. The optical density absorbance at 405 nm was read using the SpectraMax M5 plate reader.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Animals were randomized 1:1 to each group for experiments. Blinded data analysis was performed. Representative images or curves were selected to reflect the average of each experiment of n ≥ 5. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test in Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software), with significance at alpha = 0.05. Groups were compared using unpaired or paired 2-tailed Student’s t-tests with equal variance. Comparisons between >2 groups were performed using 1-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons. Prism 9.0 was used. A 2-sided P value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Proteomic analysis reveals a unique set of myofilament protein phosphorylation in the hearts

Recent studies have revealed that carvedilol can drive a β1AR-Gi-biased signaling and promote cardiac contractility, with little increase in Ca2+ cycling.16 We aimed to characterize the carvedilol-induced phosphosubstrates in the myocardium and to compare them with those induced by the classic inotropes dobutamine and isoproterenol. The phosphoproteomics of WT mouse hearts treated with β1AR ligands revealed specific increases in phosphorylated substrates compared with the saline control group (Figure 1A). Carvedilol, isoproterenol, and dobutamine increased the phosphorylation of 210, 407, and 390 unique residues of proteins relative to saline control (Figure 1A). The phosphorylated sites induced by carvedilol displayed much less overlap with those induced by isoproterenol (48) and dobutamine (59) (Figure 1A), including 30 phosphorylated sites from 26 proteins induced by all 3 drugs (Supplemental Table 1). Isoproterenol and dobutamine shared a high degree of overlap in 231 phosphorylated sites. The Gene Ontology enrichment analysis showed distinct functional clusters of proteins with ligand-induced phosphorylation (Figures 1B to 1D, Supplemental Figure 1). All 3 compounds induced phosphorylation of proteins in Z discs, A and M bands, intercalated discs, sarcolemma, and costamere (Figures 1B to 1D). Additionally, isoproterenol and dobutamine increased the phosphorylation of proteins in the sarcomere, action potential, and muscle contraction (Figures 1B to 1D, Supplemental Figures 1A to 1C). Interestingly, carvedilol uniquely promoted increases in the phosphorylation of NOS3 and Ak2 (also known as protein kinase B-β), an upstream kinase that phosphorylates NOS3 at serine 1177 (Figures 1E and 1F). Carvedilol also uniquely promoted the phosphorylation of a set of myofilament proteins, including MYPT1, MYLK, and MLC2 (Figures 1E and 1F). Both MYPT1 and MYLK play critical roles in modulating MLC phosphorylation. The phosphoproteomic data suggest that the inotropic effects of carvedilol are associated with myofilament phosphorylation.

Figure 1.

Phosphoproteomics Identifies Myofilament-Specific Phosphorylation of Downstream Substrates in Mouse Hearts

Wild-type mouse hearts were Langendorf perfused with vehicle control (Ctrl), isoproterenol (ISO) (0.1 μmol/L), dobutamine (DOB) (1 μmol/L), or carvedilol (CAR) (1 μmol/L) for 10 minutes (n = 5 in each group). Heart lysates were subjected to phosphoproteomic analysis. (A) Pie distribution of phosphoproteins induced by ISO, DOB, and CAR in mouse hearts. (B to D) Cellular organelle enrichment annotation of phosphoproteins induced by ISO, DOB, and CAR in mouse hearts. (E) Volcano plots of phosphoproteins induced by ISO, DOB, and CAR in mouse hearts. (F) Heatmap showing a selective set of phosphoproteins induced by ISO, DOB, and CAR in mouse hearts. (G) Western blots showing the phosphorylation of nitric oxide synthetase 3 (NOS3) at serine 1177 (serine 1178 in the volcano plot), Akt1 at serine 473, Akt2 at serine 474, myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 (MYPT1) at serine 507, threonine 696, and threonine 853, and myosin regulatory light chain (MLC) at serine 19 induced by ISO, DOB, and CAR in mouse hearts. Akt = protein kinase B; GO = Gene Ontology.

We then confirmed the specific phosphorylation of residues in heart tissues using western blotting. Carvedilol selectively increased the phosphorylation of MYPT1 at serine 507 and MLC at serine 19, whereas isoproterenol and dobutamine preferentially enhanced the phosphorylation of MYPT1 at threonine 696 and threonine 853 (Figure 1G, Supplemental Figure 2A). Carvedilol also selectively enhanced the phosphorylation of Akt2 at serine 474 and NOS3 at serine 1177 but did not affect the phosphorylation of Akt1 (serine 473), whereas isoproterenol and dobutamine did not (Figure 1G, Supplemental Figure 2A). Together, these findings suggest that stimulation of β1AR-NOS3 with carvedilol induces a novel signaling circuitry of MYPT1-MYLK-MLC on the myofilaments.

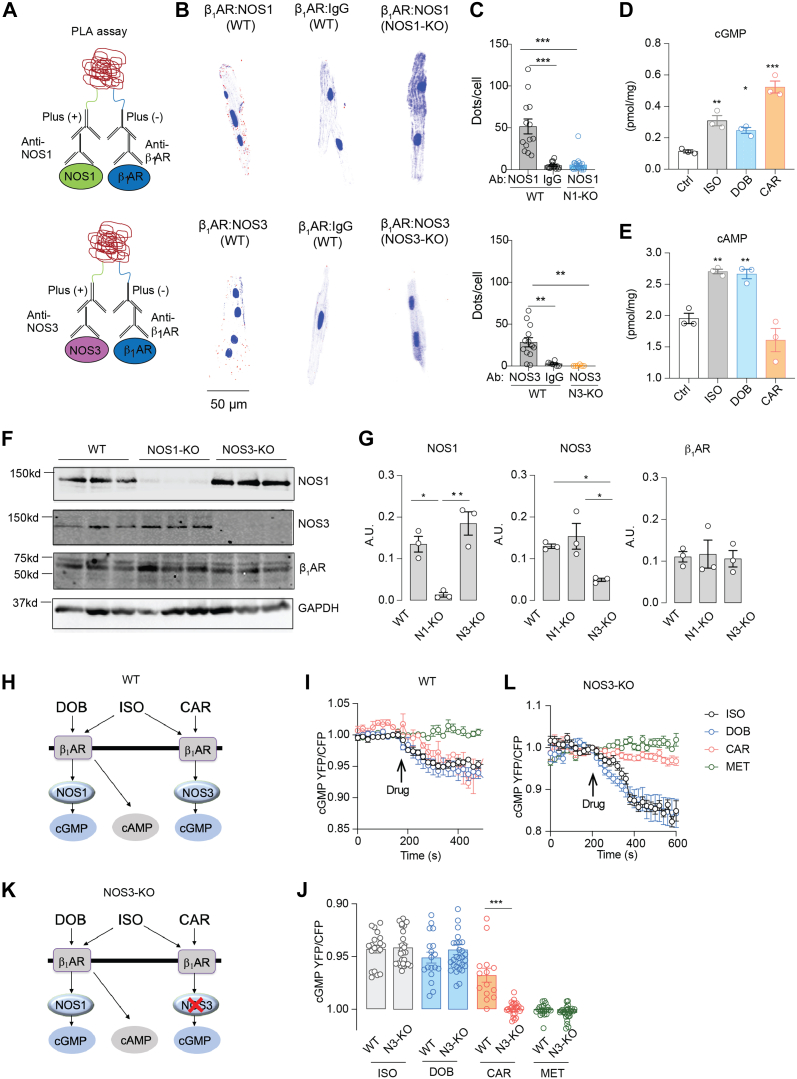

NOS1 and NOS3 dictate spatially biased cyclic nucleotide signals in a β1AR ligand–specific manner

We then explored the β1AR signaling cascade(s) leading to myofilament protein phosphorylation. Recent research suggests that subcellular-localized β1AR signalosomes and their specific downstream signaling components act as a key for precise cell function in the heart.24,32 NOS1 and NOS3 also display distinct subcellular distributions33,34 and may form distinct β1AR signalosomes in AVMs. Using the in situ PLA in isolated WT AVMs, we observed that NOS1 and NOS3 were in proximity with the β1AR in AVMs (Figures 2A to 2C). Stimulation of AVMs with carvedilol, dobutamine, and isoproterenol promoted cGMP signals; dobutamine and isoproterenol also promoted cAMP signals (Figures 2D and 2E). Deleting a NOS isoform (NOS1 or NOS3) did not affect the expression of β1AR (Figures 2F and 2G) but abolished the corresponding PLA costaining puncta of the β1AR in AVMs (Figures 2B and 2C). Both cAMP and cGMP are crucial secondary messengers regulating cardiac function, mainly through PKA-dependent and PKG-dependent protein phosphorylation.35,36 To examine the downstream signaling of individual β1AR-NOS complexes in the heart, we used FRET-based biosensors to characterize cGMP and cAMP signals and PKA activity in response to β1AR ligands. Using the cGMP biosensor Gi500, the cAMP biosensor H187, and the PKA biosensor A kinase activity reporter,25,26 we found that carvedilol selectively enhanced cGMP signals in WT but not NOS3-KO AVMs, whereas isoproterenol and dobutamine triggered increases in cGMP signals (Figures 2H to 2J) and cAMP and PKA activities in both WT and NOS3-KO AVMs (Supplemental Figures 3A to 3F). In a control, the β-blocker metoprolol did not induce any signaling in AVMs.

Figure 2.

Biased Activation of β1AR-NOS1 and β1AR-NOS3 Complexes Transduces cGMP Signal in AVMs

(A) Schematic depicting the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) of β1-adrenoceptor (β1AR) and nitric oxide synthetase (NOS) isoforms. (B, C) Adult ventricular myocyte (AVMs) were double-labeled with antibodies (Abs) against β1AR/NOS1, β1AR/NOS3, or β1AR/immunoglobulin G (IgG), respectively. The cells were then processed with secondary Ab labeling and polymerase reaction to reveal fluorescence signals according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data show representative fluorescence images and quantification of positive PLA puncta signals in WT, NOS1–knockout (KO), and NOS3-KO AVMs. The AVMs were from 6 WT, 6 NOS1-KO, and 6 NOS3-KO mice. PLA signals (red) were quantified using Image J. (D,E) Isolated WT AVMs were stimulated with saline (Ctrl) or ISO (0.1 μmol/L), DOB (1 μmol/L), or CAR (1 μmol/L) for 10 minutes. The cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels in AVMs were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Data represent AVMs isolated from 3 WT mice. (F, G) Western blots show the expression of β1AR and NOS3 in WT, NOS1-KO, and NOS3-KO mouse hearts. (H,K) Schematic of ligand-specific β1AR-induced cGMP signal in WT and NOS3-KO AVMs. Fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET)–based biosensors Gi500 (cGMP) were expressed in AVMs. Cells were stimulated with ISO (0.1 μmol/L), DOB (1 μmol/L), CAR (1 μmol/L), and metoprolol (MET; 1 μmol/L). (I, L) Time courses and quantification of cGMP responses in WT and NOS3-KO AVMs after drug treatments, as indicated by arrows. (J) The maximal increases in cGMP FRET biosensor are presented as mean ± SEM of AVMs isolated from 6 WT and 10 NOS3-KO mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values were calculated using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test. ∗∗P < 0.01. CFP = cyan fluorescent protein; GAPDH = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; YFP = yellow fluorescent protein; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

The increase in cGMP induced by carvedilol was abolished by deleting NOS3 (Figures 2J to 2L). Deleting NOS3 also prevented carvedilol from enhancing MYPT1 and MLC phosphorylation in hearts (Supplemental Figures 4A and 4B). In contrast, isoproterenol and dobutamine enhanced the phosphorylation of multiple Ca2+-handling proteins, such as phospholamban (PKA site serine 16), L-type calcium channel (PKA site serine 1928), and ryanodine receptor (PKA site serine 2808) (Supplemental Figures 5A and 5B), consistent with their roles in increasing Ca2+ cycling, and troponin I, which desensitizes the myofilament response to Ca2+.37 In comparison, carvedilol failed to induce the phosphorylation of Ca2+-handling proteins (Supplemental Figures 5A and 5B). These data indicate that carvedilol activates the β1AR-NOS3 complex to induce the cGMP pathway and promote myofilament protein phosphorylation selectively.

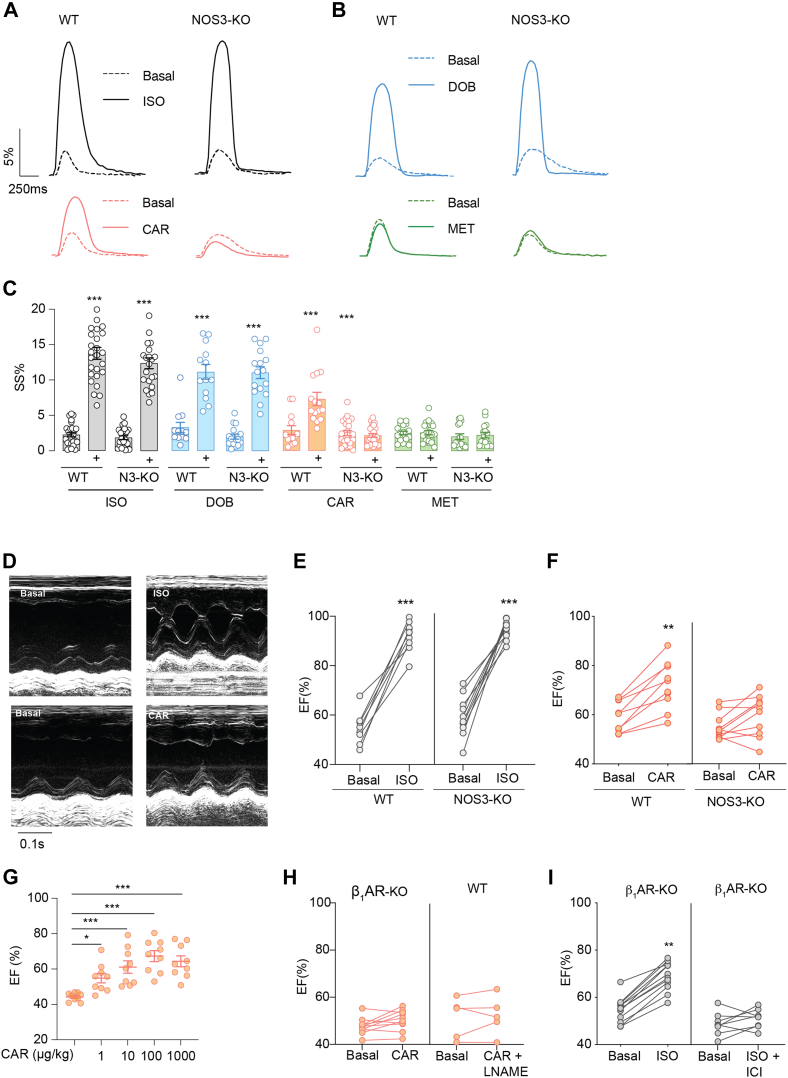

In agreement, carvedilol promoted sarcomere shortening in WT AVMs but not in NOS3-KO AVMs (Figures 3A to 3C). Isoproterenol and dobutamine promoted sarcomere shortening in both WT and NOS3-KO AVMs, whereas metoprolol did not enhance the contractility in either cell. Unlike isoproterenol and dobutamine, carvedilol did not enhance Ca2+ cycling in WT and NOS3-KO myocytes (Supplemental Figures 5C to 5E). Moreover, carvedilol (intraperitoneal injection) increased cardiac EF in WT but not NOS3-KO mice in a dose-dependent manner, which had a maximized response at 100 μg/kg (Figures 3D to 3G, Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). As control, deletion of β1AR prevented the cardiac contractile response to carvedilol stimulation (Figure 3H). The carvedilol-induced increase in cardiac EF was abolished by NOS inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (Figure 3H). Additionally, deletion of β1AR significantly reduced the cardiac EF response to isoproterenol stimulation, and the remaining response was abolished by the β2AR-selective antagonist ICI-118,551 (Figure 3I). In comparison, NOS3 deletion did not affect the cardiac response to isoproterenol stimulation (Figures 3D and 3E). Together, these data suggest that NOS3 is necessary for myofilament-specific β1AR signaling to promote substrate phosphorylation and cardiac contractility.

Figure 3.

NOS3 Is Essential for Myofilament-Specific β1AR Signaling to Promote Cardiac Contractility

(A to C) AVMs from WT and NOS3-KO mice are loaded with fluo-4 Ca2+ dye and paced at 1 Hz. Sarcomere shortening and calcium cycling were recorded at baseline and after stimulation with ISO (black; 0.1 μmol/L), DOB (blue; 1 μmol/L), CAR (orange; 1 μmol/L), or MET (green; 1 μmol/L). Representative curves show dynamics of sarcomere shortening, which was quantified as percentage of sarcomere length shortening (SS%) in WT and NOS3-KO AVMs before (dashed line) and after ligand stimulation. AVMs were isolated from 6 WT and 7 NOS3-KO mice. (D to G) WT, β1AR-KO, and NOS3-KO mice were subjected to echocardiographic measurements before and after stimulation with ISO (100 μg/kg) or CAR (1-1,000 μg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection as indicated (n = 9-12). Data show representative echocardiographic images of the left ventricle before and after drug treatment. (H,I) WT and β1AR-KO mice were subjected to echocardiographic measurements. Mice were treated with ISO (100 μg/kg) or CAR (100 μg/kg) in the presence of the β2AR antagonist NOS inhibitor Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (LNAME) (100 μg/kg) or ICI-118,551 (ICI; 100 μg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection. Cardiac ejection fraction (EF) was quantified as mean ± SEM (n = 5-9). For B, C, and G, P values were calculated using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test (∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001). For E, F, H, and I, P values were calculated using paired Student’s t-tests (∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001). Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Activation of the myofilament β1AR-PKG1-MLCK pathway enhances substrate phosphorylation and cardiac contractile function

We further validate the effects of cGMP signals on downstream kinase-mediated substrate phosphorylation. Consistent with the FRET assays on cyclic nucleotide signals, carvedilol, isoproterenol, and dobutamine promoted the PKG phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein at serine 239, whereas isoproterenol and dobutamine also enhanced the PKA-dependent phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein at serine 157 (Figures 4A and 4B). Two PKG isoforms, PKG1 and PKG2, are expressed in the heart. Cardiac-specific deletion of PKG1 (PKG1–cardiac KO) but not PKG2 deletion (PKG2-KO) abrogated the carvedilol-induced increases in cardiac EF in mice (Figures 4C and 4D). In a control, carvedilol induced increases in cardiac EF in mice expressing MHC-cre only (Figure 4C). Deleting PKG1 abolished the carvedilol-induced phosphorylation of MYPT1 at serine 507 and MLC at serine 19 in the hearts (Figures 4E and 4F) without affecting the cAMP and cGMP signals (Supplemental Figures 6A and 6B). Additionally, deleting PKG1 also abolished carvedilol-induced increases in sarcomere shortening in AVMs without affecting Ca2+ cycling but did not affect the responses induced by isoproterenol and dobutamine (Figures 5A to 5E). Moreover, inhibition of MLCK, the kinase that promotes phosphorylation of MLC, with ML-7, a MYLK inhibitor, also prevented the carvedilol-induced increase in sarcomere shortening (Figures 5F and 5G). These data suggest that a PKG1-MLCK pathway is necessary for myofilament-specific β1AR-cGMP signaling to promote substrate phosphorylation and cardiac contractility.

Figure 4.

PKG1 Is Necessary for Myofilament-Specific β1AR Signaling to Promote Protein Phosphorylation and Cardiac Contractility

(A, B) WT mice hearts were perfused with saline (Ctrl), ISO (0.1 μmol/L), DOB (1 μmol/L), or CAR (1 μmol/L) for 10 minutes, and the phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) at serine 157 and serine 239 was probed and quantified (n = 5). (C, D) PKG1-flox/flox (PKG1-FF), cardiac deletion of PKG1 (PKG1-CKO), CRE, WT, and whole-body deletion of PKG2 (PKG2-KO) mice were subjected to echocardiographic measurements before and after stimulation with CAR (intraperitoneal injection, 100 μg/kg). Cardiac EF was quantified in PKG1-flox, PKG1-CKO, and CRE mice (n = 8) (C) and in PKG2-KO and WT mice (n = 8) (D). (E, F) PKG1-FF and PKG1-CKO hearts were subjected to Langendorf perfusion with saline and CAR (1 μmol/L) for 10 minutes. Heart tissues were lysed to probe the phosphorylation of phospholamban (PLB), MYPT1, and MLC (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared with basal condition or between indicated groups. P values were calculated using 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc or paired Student’s t-tests. Abbreviations as in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3.

Figure 5.

A PKG1-MLCK Pathway Is Necessary for Myofilament-Specific β1AR Signaling to Promote Excitation-Contraction Coupling in AVMs

Isolated AVMs from PKG1-FF or PKG1-CKO mice were loaded with Ca2+ dye fluo-4 and paced at 1 Hz. Sarcomere shortening and Ca2+ cycling were recorded at baseline and after stimulation with ISO (0.1 μmol/L), DOB (1 μmol/L), or CAR (1 μmol/L). (A,B) Representative curves show dynamics of sarcomere shortening, which were quantified as SS% in AVMs. (C-E) Representative curves show dynamics of Ca2+ cycling, which were quantified as intracellular Ca2+ amplitude and tau in AVMs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of AVMs from 3 PKG1-FF and 3 PKG1-CKO mice. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 compared with basal condition or between indicated groups. P values were calculated using 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test or paired Student’s t-test. (F,G) Sarcomere shortening and Ca2+ cycling were recorded at baseline and after stimulation with CAR (1 μmol/L) in the presence and absence of the MYLK inhibitor ML-7 (1 μmol/L). Representative curves show dynamics of sarcomere shortening and Ca2+ cycling, which were quantified as SS%, CaT, and tau, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of AVMs from 5 mice. P values were obtained using paired Student’s t-test. ∗P < 0.05 compared with basal. Abbreviations as in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4.

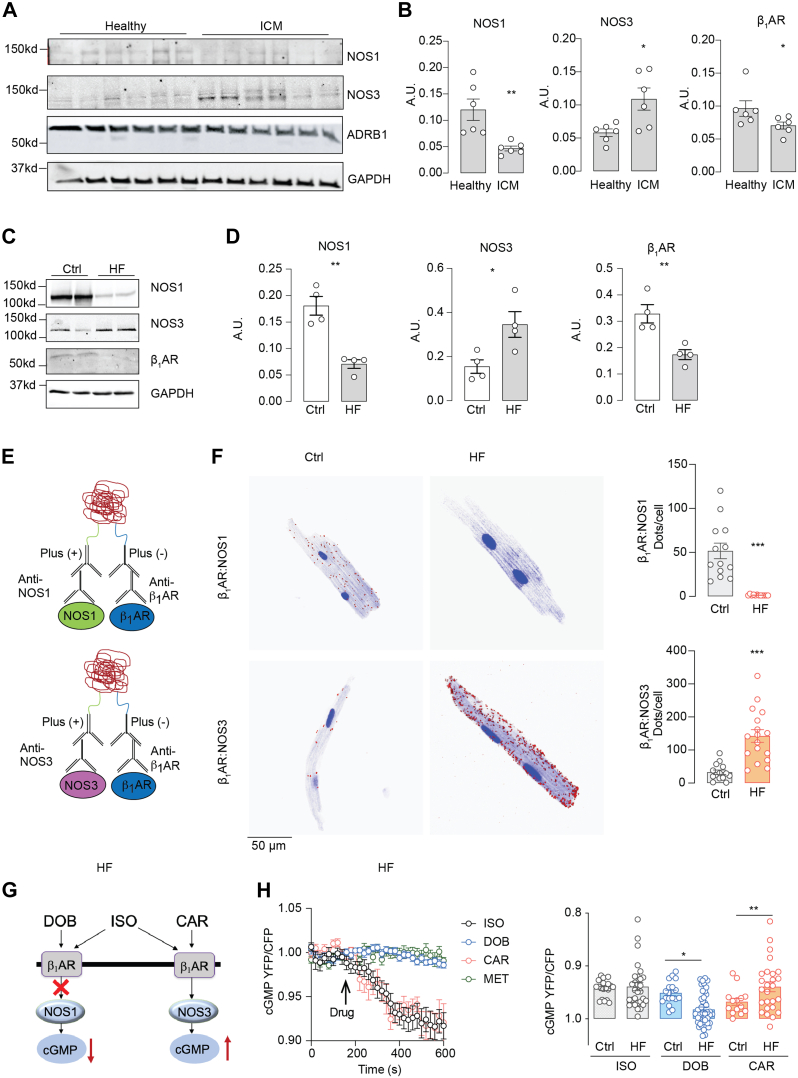

Chronic β-adrenergic stimulation in HF shifts the cardiac β1AR from NOS1 to NOS3

Both cAMP and cGMP signals are blunted in patients with HF, along with depressed cardiac contractility.38 We investigated the expression and integrity of β1AR-NOS3 signalosomes in failing AVMs. In human ischemia cardiac myopathy, we detected an increased expression of NOS3 but reduced expression of β1AR and NOS1 (Figures 6A and 6B). In a mouse model of cardiomyopathy induced by chronic β-adrenergic stimulation (60 mg/kg [−]-isoproterenol hydrochloride injection, 2 weeks),32 we detected similar changes in NOS3, NOS1, and β1AR expression to those in human HF (Figures 6C and 6D). Consequently, we detected much less PLA signal for β1AR-NOS1 costaining in failing mouse AVMs than the control cells after chronic saline infusion (Figures 6E and 6F). However, the PLA signals from β1AR-NOS3 costaining were increased in failing AVMs relative to the controls (Figures 6E and 6F). We subsequently determined the ligand-induced cAMP and cGMP signals in failing AVMs using FRET biosensors (Figures 6G and 6H, Supplemental Figure 7). The carvedilol-induced cGMP signals were enhanced in failing myocytes relative to the controls, whereas the dobutamine-induced cGMP signal was blunted (Figures 6F and 6G). The cAMP signals induced by isoproterenol and dobutamine were reduced in HF vs control (Supplemental Figures 7A and 7B). These data demonstrate that β1AR switches from NOS1 to NOS3 to drive the cGMP-PKG1 signaling pathway in HF.

Figure 6.

Cardiac β1AR Switches Coupling From NOS1 to NOS3 in Failing Hearts

(A, B) Human ventricle samples from 6 healthy donor human hearts and 6 ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) patient hearts were lysed to examine the expression of NOS1, NOS3, and β1AR with western blot. (C, D) Mice underwent chronic infusion of saline or ISO (60 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks. The expression of NOS1, NOS3, and β1AR in mouse hearts was examined and quantified (n = 4). The protein expression levels in western blots were quantified. (E) Schematics depicting the PLAs to probe β1AR-NOS1 and β1AR-NOS3 complex in failing myocytes from mice after long-term infusion of ISO. (F) AVMs were isolated from the mice after long-term infusion with saline and ISO and processed for PLA staining with antibodies against β1AR/NOS1 or β1AR/NOS3. The PLA signals in healthy control (Ctrl, n = 3) and heart failure (HF, n = 4) mouse AVMs were imaged and quantified. (G) A schematic diagram shows the alteration of β1AR-NOS1 and β1AR-NOS3 cascades and cGMP signaling in HF. (H) AVMs were isolated from the mice after chronic infusion with ISO. AVMs expressing Gi500 FRET biosensor were stimulated with ISO, DOB, CAR, or MET as indicated. Representative time course and quantification of cyclic GMP FRET response to ISO (0.1 μmol/L), DOB (1 μmol/L), CAR (1 μmol/L), or MET (1 μmol/L) in Ctrl and HF AVMs. Data represent AVMs isolated from 5 Ctrl and 6 HF mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values were calculated using Student’s t-test (B, D, and F), 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc, or paired Student’s t-test (H). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared with healthy control condition. Abbreviations as in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4.

To investigate the functional effects of the elevated myofilament-specific β1AR-NOS3-cGMP signaling in HF, we assessed the contractile response in AVMs from mice after long-term isoproterenol infusion. Carvedilol enhanced sarcomere shortening without raising the intracellular Ca2+ transient peak (Figures 7A to 7E), whereas dobutamine and metoprolol minimally enhanced sarcomere shortening in failing AVMs. Isoproterenol increased sarcomere shortening and intracellular Ca2+ cycling. We further evaluated the short-term effects of carvedilol on cardiac contractility in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Compared with sham mice, mice displayed 35% infarction in the left ventricle with a reduced cardiac EF 7 days after myocardial infarction (Supplemental Figures 8A to 8C, Supplemental Table 4). In healthy mice, carvedilol and dobutamine also induced dose-dependent increases in cardiac EF, which were maximized at 100 μg/kg and 1,000 μg/kg, respectively (Supplemental Figure 8D). In mice with myocardial infarction, carvedilol induced a more robust and dose-dependent increase in cardiac EF than those induced by dobutamine (Figures 7F to 7H, Supplemental Table 5). Our data validate the myofilament-specific β1AR-NOS3 pathway underlying the inotropic benefits of carvedilol and point out a potential role of the PKG1-dependent myofilament signaling circuitry in providing inotropic support in HF.

Figure 7.

Stimulation of Myofilament-Specific β1AR-NOS3 Signaling Enhances Cardiac Contractility in Failing Hearts

AVMs were isolated from HF mice induced by long-term infusion of ISO. HF AVMs were loaded with fluo-4 (2 μmol/L) and paced at 1 Hz. (A, B) Sarcomere shortening and (C to E) Ca2+ cycling were recorded at baseline and after stimulation with ISO (0.1 μmol/L), DOB (1 μmol/L), CAR (1 μmol/L), or MET (1 μmol/L). Representative curves show the kinetics of sarcomere shortening and Ca2+ cycling, which were quantified as SS%, CaT amplitude, and tau in response to βAR stimulation. Data represent AVMs isolated from 7 HF mice. (F to H) WT mice were subjected to myocardial infarction surgery to induce the acute HF model. At 7 days after myocardial infarction, mice were subjected to echocardiographic measurements at baseline or after treatment with DOB or CAR (0.1-1,000 μg/kg, intraperitoneal injection, n = 10). Data show representative echocardiographic images of the left ventricle before and after drug treatment. DOB and CAR induced dose-dependent increases in cardiac EF (half maximal effective concentrations of 31.36 mg/kg for DOB and 0.61 mg/kg for CAR) (G). The maximal cardiac EF is quantified in (H). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values were calculated using paired t-tests between 2 groups (H, left) or 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc or paired Student’s t-test (B, D, E, and H, right). ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 between indicated groups. Abbreviations as in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4.

Discussion

Cardiac β-adrenergic stimulation transduces signals to different subcellular compartments to coordinate excitation-contraction coupling. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and myofilaments are 2 critical cellular compartments targeted by β-adrenergic signal to enhance excitation-contraction coupling. Although prior research has concentrated predominantly on dissecting the impacts of β-adrenergic signaling at the plasma membrane and sarcoplasmic reticulum in regulating ion channels, transporters, and the intricate cycle of Ca2+, there remains a dearth of understanding the mechanisms through which β-adrenergic signals interact with myofilaments in the context of cardiac physiology and pathology.2 Myofilament dysfunction is linked to depressed phosphorylation and diminished cardiac contractility, which is typified by desensitization of β-adrenergic signaling.3, 4, 5,39 Myofilament dysfunction thus emerges as an important mechanism and therapeutic target in failing hearts.11,12,40 Through a combinational analysis of phosphoproteomics, FRET biosensors, and KO animals, we have identified a myofilament-specific signaling circuitry, including PKG1-dependent phosphorylation of MLCK, MYPT1, and MLC, which can be activated by β1AR-NOS3-cGMP cascade and promotes cardiac contractility with minimal enhancing Ca2+ cycling. Notably, the β1AR-NOS3 signaling is preserved and effectively promotes phosphorylation of MYPT1 and MLC and cardiac contractility in failing hearts. Thus, we define this myofilament-specific PKG1-MLCK-MYPT1-MLC signaling circuitry as a potential therapeutic target in HF.

Through our proteomic screening, a coordinated phosphorylation of several myofilament proteins, including MLC2, MLCK and MYPT1, was unveiled upon β1AR-NOS3 stimulation. Cardiomyocytes contractility is heavily dependent upon the phosphorylation of MLC2, which enhances myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and is regulated by the balance between MLCK and MYPT1 activity.37,38 Our study showed that stimulation of β1AR-NOS3 signaling can selectively promote the phosphorylation of MLCK at serine 1801, MLC2 at serine 19, and MYPT1 at serine 507. We show that PKG1 but not PKG2 is necessary for β1AR-induced phosphorylation of MYPT1 and MLC2, consistent with the role of PKG1 in promoting MLC phosphorylation in smooth muscle cells.41 PKG1 could be an upstream kinase to indirectly promote MLC2 phosphorylation via phosphorylating MLCK and MYPT1. In this case, the phosphorylation of MYPT1 at serine 507 might inhibit the phosphatase activity, indirectly enhancing the phosphorylation of MLC2. Additionally, stimulation of β1AR-NOS3 also promotes PKG-dependent phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C at serine 282.16 In comparison, stimulation of β1AR with isoproterenol and dobutamine promotes phosphorylation of MYPT1 at threonine 696 and threonine 853, myosin binding protein C at serine 273 and serine 302, and troponin I at serine 23/24.16,42 These observations suggest the precise spatial actions of cyclic nucleotides and their downstream kinases in promoting phosphorylation of substrates on the myofilaments. Indeed, our data reveal that the impacts of βAR-NOS coupling can be shaped by the subcellular location of βARs and in a ligand-specific manner. NOS3 and NOS1 are localized to the sarcolemma and sarcoplasmic reticulum,33,34 coincident with 2 distinct pools of β1AR identified at the sarcolemma and sarcoplasmic reticulum, respectively.24,32 Both β1AR and NOS3 are located at the transverse tubule membranes,43 which are proximal to the myofilaments and can facilitate the β1AR-NOS3 signaling to this cellular compartment. Meanwhile, a recent study showed that inhibition of phosphodiesterase 1 enhances cardiac contractility, with limited increases in Ca2+ cycling.15 Future studies could examine other regulators, including phosphodiesterase isoforms, in shaping myofilament-specific cGMP-PKG1 activities and downstream substrate phosphorylation and contractility in physiological responses and heart diseases.

In pigs with HF, reduction of NOS3 and PKG1 expression and cGMP contents are linked to impaired cardiac function, which are restored by dapagliflozin treatment.44 Evidence also supports the role of NO-cGMP in regulating Ca2+ transient and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity through NO- and cGMP-PKG-dependent mechanisms in the heart.37,45, 46, 47 The phosphorylation of MLC2 at serine 19 and MYPT1 at serine 507 is critical for cardiac myofilament contraction.48, 49, 50 The phosphorylation of MLC2 at serine 19 improves myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and promotes cross-bridging, thus enhancing contractility in the heart.51 It is worth noting that prior work implicated multiple myofilament proteins, such as myosin binding protein C and troponin I,16,42 in modulating cardiomyocyte function, including contraction and relaxation. Thus, the observed effects on cardiac contraction in the present study might result from the cumulative impact of various myofilament proteins. Recent studies have convincingly demonstrated that loss of MLC phosphorylation leads to pathologic cardiac hypertrophy and HF.3, 4, 5, 6 Direct overexpression of PKG1 in stem cells increases cell survival and cardiac function after myocardial infarction.52 Stimulating myocardial α1-adrenoceptor or 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A receptors enhances MLC phosphorylation and offers contractile support in the failing heart.53 Here, we observed an increased NOS3 expression in human and mouse HF, which was accompanied by increased β1AR association with NOS3. We were able to rescue the depressed cardiac EF in myocardial infarction by stimulating the β1AR-NOS3 pathway. In the same vein, the NO-cGMP signal has recently been recognized as a feasible therapeutic target for HF with reduced EF, including a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator, vericiguat,54 and several phosphodiesterase inhibitors.15,55,56 Further studies will determine whether these therapeutic strategies lead to increased phosphorylation of MLC and other proteins, such as myosin binding protein C, in the myofilaments. Nevertheless, the newly characterized myofilament-specific PKG1-dependent MYPT1-MLCK-MLC circuitry will facilitate analysis of the specific alternations of phosphorylation in different etiologies of HF and offer a platform for identifying novel molecular targets for HF therapies.

G protein–coupled receptors can transduce biased signaling by activating specific downstream signaling and regulatory proteins.57 βAR activates NO-cGMP pathways in parallel with cAMP/PKA signaling, both necessary for cardiac inotropic responses.25,33,36,58 Although structural studies have revealed little difference between carvedilol-bound β1AR and other ligand-bound receptors,59,60 the uniqueness of carvedilol appears to be linked to its ability to drive β1AR coupling to Gi to transduce downstream signaling cascades,16,61,62 including this NOS3/cGMP/PKG1/MLC2 signaling at the myofilaments. The characterization of 2 dynamic pools of β1AR at the plasma membrane and sarcoplasmic reticulum24,32 and their potential selective association with NOS isoforms could offer additional avenues to selectively regulate cardiac excitation and contraction in HF.34,43,63 Additionally, targeting increased β1AR-PKG1-MLC2 signaling may offer a unique opportunity for supporting cardiac inotrope and preventing cardiac remodeling.16,64,65 The myofilament-mediated inotropy can provide safer therapeutic options, devoid of adverse effects of inotropic agents such as dobutamine and milrinone,66 while mitigating cardiac remodeling and hypertrophy.8,67

Clinically, carvedilol is recognized for its efficacy in chronic HF leading to improved cardiac EF and inotropy.68 Specifically, carvedilol has shown effectiveness in treating patients with HF after acute myocardial infarction.69 However, existing literature attributes these benefits to a biological reverse-remodeling process, with salutary changes in EF becoming evident after months of clinical exposure.68 Additionally, carvedilol, like other β-blockers, requires careful up-titration in patients with HF to ensure tolerability. Despite its well-established benefits, investigations of the acute effects of carvedilol in patients are scarce. Our studies are limited to observations in mouse cardiomyocytes and hearts; whether these acute responses to carvedilol are translatable to humans remains to be examined. Meanwhile, the impacts of carvedilol treatment on cardiac adenosine triphosphate and oxygen consumption are yet to be examined. Given that enhanced cardiac inotropy may demand increased adenosine triphosphate and oxygen consumption, further research is essential. There is potential for a combination therapy with carvedilol and agents to enhance cardiac metabolism, which could offer more favorable long-term therapeutic effects in patients with HF.

Study limitations

Our investigation was primarily limited to mice. Whether carvedilol could mildly enhance cardiac output in healthy and diseased human hearts remains to be elucidated. There are significant species differences between mice and humans. Therefore, confirming the potential inotropic effects of carvedilol in humans is essential. Additionally, we demonstrated that phosphorylation of MYPT1 at Serine 507 was a downstream target of carvedilol-transduced myofilament-specific cAMP-PKG signaling. A myofilament-specific manipulation of cGMP should be designed to confirm if the phosphorylation of MYPT1 at Serine 507 is controlled by myofilament-localized cGMP. It is yet to be elucidated whether the phosphorylation of MYPT1 is essential and necessary for the inotropic effect of carvedilol.

Conclusions

Collectively, we have identified myofilament PKG1-dependent MLCK-MYPT1-MLC2 circuitry driven by a β1AR-NOS3 pathway that enhances cardiac contractility with a minimal increase in Ca2+ cycling. Our study raises the possibility of targeting this myofilament-specific signaling circuitry for treatment of patients with HF.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Phosphorylation of myofilament proteins is critically regulated to coordinate beat-to-beat contraction and relaxation in the heart. The phosphorylation of myofilament proteins is often depressed in HF. The causes of depressed phosphorylation of myofilament protein and its contribution to HF are poorly understood. Our studies have identified novel β1AR-PKG1 signaling cascades to drive myofilament protein phosphorylation and have provided evidence on the impairment of this signaling pathway in HF, contributing to contractile dysfunction.

TRANSLATION OUTLOOK: Impaired left ventricular systolic performance is a hallmark feature of HF. Altered myofilament phosphorylation may contribute to the impaired systolic performance of HF. Our study provides evidence that PKG1-mediated MLC2 phosphorylation presents a potential therapeutic target to restore cardiac contractility in patients with HF. Phosphorylation of myofilaments is critically regulated to coordinate beat-to-beat contraction and relaxation in the heart. The phosphorylation of myofilament proteins is often depressed in HF. Our studies have identified local PKG1 signaling on the myofilaments, which promotes MLC2 phosphorylation and contractility with minimal effects on calcium cycling. Furthermore, we characterized biased cardiac β1AR-Gi-NOS3 signaling that can drive activation of myofilament PKG1. This work presents evidence that myofilament phosphorylation can be selectively modulated in heart diseases. PKG1-mediated MLC2 phosphorylation presents a potential therapeutic target to restore cardiac contractility in patients with HF.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-HL147263 and HL162825, VA Merit grants IK6BX005753 and BX005100 (to Dr Xiang). Drs Wang and Zhu are recipients of American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship. Dr Xiang is an established American Heart Association investigator. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental figures and tables, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Braunwald E. The war against heart failure: the Lancet lecture. Lancet. 2015;385:812–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorenzen-Schmidt I., Clarke S.B., Pyle W.G. The neglected messengers: Control of cardiac myofilaments by protein phosphatases. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;101:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheikh F., Ouyang K., Campbell S.G., et al. Mouse and computational models link Mlc2v dephosphorylation to altered myosin kinetics in early cardiac disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1209–1221. doi: 10.1172/JCI61134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren S.A., Briggs L.E., Zeng H., et al. Myosin light chain phosphorylation is critical for adaptation to cardiac stress. Circulation. 2012;126:2575–2588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.116202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan C.C., Muthu P., Kazmierczak K., et al. Constitutive phosphorylation of cardiac myosin regulatory light chain prevents development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E4138–E4146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505819112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman E.A., Aballo T.J., Melby J.A., et al. Defining the sarcomeric proteoform landscape in ischemic cardiomyopathy by top-down proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2023;22:931–941. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tucholski T., Cai W., Gregorich Z.R., et al. Distinct hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genotypes result in convergent sarcomeric proteoform profiles revealed by top-down proteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:24691–24700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006764117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poole-Wilson P.A., Swedberg K., Cleland J.G., et al. Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Carvedilol or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13800-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajam T., Ajam S., Devaraj S., Mohammed K., Sawada S., Kamalesh M. Effect of carvedilol vs metoprolol succinate on mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 2018;199:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.01.005. d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chourdakis E., Koniari I., Velissaris D., Tsigkas G., Kounis N.G., Osman N. Beta-blocker treatment in heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation: challenges and perspectives. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2021;18:362–375. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2021.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teerlink J.R., Diaz R., Felker G.M., et al. for the GALACTIC-HF Investigators. Effect of ejection fraction on clinical outcomes in patients treated with omecamtiv mecarbil in GALACTIC-HF. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maack C., Eschenhagen T., Hamdani N., et al. Treatments targeting inotropy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3626–3644. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surdo N.C., Berrera M., Koschinski A., et al. FRET biosensor uncovers cAMP nano-domains at beta-adrenergic targets that dictate precise tuning of cardiac contractility. Nat Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbagallo F., Xu B., Reddy G.R., et al. Genetically encoded biosensors reveal PKA hyperphosphorylation on the myofilaments in rabbit heart failure. Circ Res. 2016;119:931–943. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller G.K., Song J., Jani V., et al. PDE1 inhibition modulates Cav1.2 channel to stimulate cardiomyocyte contraction. Circ Res. 2021;129:872–886. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q., Wang Y., West T.M., et al. Carvedilol induces biased beta1 adrenergic receptor-nitric oxide synthase 3-cyclic guanylyl monophosphate signalling to promote cardiac contractility. Cardiovasc Res. 2021;117:2237–2251. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedowitz N.J., Batt A.R., Darabedian N., Pratt M.R. MYPT1 O-GlcNAc modification regulates sphingosine-1-phosphate mediated contraction. Nat Chem Biol. 2021;17:169–177. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0640-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Somlyo A.P., Somlyo A.V. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1325–1358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang Y., Devic E., Kobilka B. The PDZ binding motif of the beta 1 adrenergic receptor modulates receptor trafficking and signaling in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33783–33790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gyurko R., Leupen S., Huang P.L. Deletion of exon 6 of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene in mice results in hypogonadism and infertility. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2767–2774. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shesely E.G., Maeda N., Kim H.S., et al. Elevated blood pressures in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13176–13181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeifer A., Aszodi A., Seidler U., Ruth P., Hofmann F., Fassler R. Intestinal secretory defects and dwarfism in mice lacking cGMP-dependent protein kinase II. Science. 1996;274:2082–2086. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wegener J.W., Nawrath H., Wolfsgruber W., et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase I mediates the negative inotropic effect of cGMP in the murine myocardium. Circ Res. 2002;90:18–20. doi: 10.1161/hh0102.103222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y., Shi Q., Li M., et al. Intracellular beta1-adrenergic receptors and organic cation transporter 3 mediate phospholamban phosphorylation to enhance cardiac contractility. Circ Res. 2021;128:246–261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West T.M., Wang Q., Deng B., et al. Phosphodiesterase 5 associates with beta2 adrenergic receptor to modulate cardiac function in type 2 diabetic hearts. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy G.R., West T.M., Jian Z., et al. Illuminating cell signaling with genetically encoded FRET biosensors in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2018;150:1567–1582. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201812119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mertins P., Qiao J.W., Patel J., et al. Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat Methods. 2013;10:634–637. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rappsilber J., Mann M., Ishihama Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1896–1906. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiao X., Sherman B.T., da Huang W., et al. DAVID-WS: a stateful web service to facilitate gene/protein list analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1805–1806. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts251. d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu B., Li M., Wang Y., et al. GRK5 controls SAP97-dependent cardiotoxic beta1 adrenergic receptor-CaMKII signaling in heart failure. Circ Res. 2020;127:796–810. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng B., Zhang Y., Zhu C., et al. Divergent actions of myofibroblast and myocyte beta2-adrenoceptor in heart failure and fibrotic remodeling. Circ Res. 2023;132:106–108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.321816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y., Zhao M., Shi Q., et al. Monoamine oxidases desensitize intracellular beta1AR signaling in heart failure. Circ Res. 2021;129(10):965–967. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barouch L.A., Harrison R.W., Skaf M.W., et al. Nitric oxide regulates the heart by spatial confinement of nitric oxide synthase isoforms. Nature. 2002;416:337–339. doi: 10.1038/416337a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carnicer R., Suffredini S., Liu X., et al. The subcellular localisation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase determines the downstream effects of NO on myocardial function. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:321–331. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaccolo M., Movsesian M.A. cAMP and cGMP signaling cross-talk: role of phosphodiesterases and implications for cardiac pathophysiology. Circ Res. 2007;100:1569–1578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.144501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziolo M.T., Maier L.S., Piacentino V., III, Bossuyt J., Houser S.R., Bers D.M. Myocyte nitric oxide synthase 2 contributes to blunted beta-adrenergic response in failing human hearts by decreasing Ca2+ transients. Circulation. 2004;109:1886–1891. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124231.98250.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamdani N., Bishu K.G., von Frieling-Salewsky M., Redfield M.M., Linke W.A. Deranged myofilament phosphorylation and function in experimental heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;97:464–471. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs353. d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamel R., Leroy J., Vandecasteele G., Fischmeister R. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases as therapeutic targets in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:90–108. doi: 10.1038/s41569-022-00756-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szczesna D., Ghosh D., Li Q., et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in the regulatory light chains of myosin affect their structure, Ca2+ binding, and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7086–7092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pabel S., Wagner S., Bollenberg H., et al. Empagliflozin directly improves diastolic function in human heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:1690–1700. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho J.S., Han Y.S., Jensen C., Sieck G. Effects of arginase inhibition on myocardial Ca2+ and contractile responses. Physiol Rep. 2022;10 doi: 10.14814/phy2.15396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thoonen R., Giovanni S., Govindan S., et al. Molecular screen identifies cardiac myosin-binding protein-C as a protein kinase G-Ialpha substrate. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:1115–1122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ziolo M.T., Bers D.M. The real estate of NOS signaling: location, location, location. Circ Res. 2003;92:1279–1281. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000080783.34092.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang N., Feng B., Ma X., Sun K., Xu G., Zhou Y. Dapagliflozin improves left ventricular remodeling and aorta sympathetic tone in a pig model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18:107. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang L., Liu G., Zakharov S.I., Bellinger A.M., Mongillo M., Marx S.O. Protein kinase G phosphorylates Cav1.2 alpha1c and beta2 subunits. Circ Res. 2007;101:465–474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Irie T., Sips P.Y., Kai S., et al. S-nitrosylation of calcium-handling proteins in cardiac adrenergic signaling and hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2015;117:793–803. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vandecasteele G., Verde I., Rucker-Martin C., Donzeau-Gouge P., Fischmeister R. Cyclic GMP regulation of the L-type Ca2+ channel current in human atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2001;533:329–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0329a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kampourakis T., Sun Y.B., Irving M. Myosin light chain phosphorylation enhances contraction of heart muscle via structural changes in both thick and thin filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E3039–E3047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602776113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kampourakis T., Irving M. Phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain controls myosin head conformation in cardiac muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;85:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samson S.C., Elliott A., Mueller B.D., Ki, et al. p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) phosphorylates myosin phosphatase and thereby controls edge dynamics during cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:10846–10862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Velden J., Papp Z., Boontje N.M., et al. The effect of myosin light chain 2 dephosphorylation on Ca2+-sensitivity of force is enhanced in failing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L., Pasha Z., Wang S., et al. Protein kinase G1 alpha overexpression increases stem cell survival and cardiac function after myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hussain R.I., Qvigstad E., Birkeland J.A., et al. Activation of muscarinic receptors elicits inotropic responses in ventricular muscle from rats with heart failure through myosin light chain phosphorylation. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:575–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armstrong P.W., Pieske B., Anstrom K.J., et al. for the VICTORIA Study Group Vericiguat in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1883–1893. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takimoto E., Champion H.C., Li M., et al. Chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2005;11:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mishra S., Sadagopan N., Dunkerly-Eyring B., et al. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase type 9 reduces obesity and cardiometabolic syndrome in mice. J Clin Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI148798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gurevich V.V., Gurevich E.V. Biased GPCR signaling: possible mechanisms and inherent limitations. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;211 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang X., Szeto C., Gao E., et al. Cardiotoxic and cardioprotective features of chronic beta-adrenergic signaling. Circ Res. 2013;112:498–509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warne T., Moukhametzianov R., Baker J.G., et al. The structural basis for agonist and partial agonist action on a beta(1)-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 2011;469:241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature09746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Warne T., Edwards P.C., Leslie A.G., Tate C.G. Crystal structures of a stabilized beta1-adrenoceptor bound to the biased agonists bucindolol and carvedilol. Structure. 2012;20:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang J., Hanada K., Staus D.P., et al. Galphai is required for carvedilol-induced beta1 adrenergic receptor beta-arrestin biased signaling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1706. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim J., Grotegut C.A., Wisler J.W., et al. The beta-arrestin-biased beta-adrenergic receptor blocker carvedilol enhances skeletal muscle contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:12435–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1920310117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bendall J.K., Damy T., Ratajczak P., et al. Role of myocardial neuronal nitric oxide synthase-derived nitric oxide in beta-adrenergic hyporesponsiveness after myocardial infarction-induced heart failure in rat. Circulation. 2004;110:2368–2375. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145160.04084.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sawangkoon S., Miyamoto M., Nakayama T., Hamlin R.L. Acute cardiovascular effects and pharmacokinetics of carvedilol in healthy dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2000;61:57–60. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2000.61.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DasGupta P., Broadhurst P., Lahiri A. The effects of intravenous carvedilol, a new multiple action vasodilatory beta-blocker, in congestive heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991;18(suppl 4):S12–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Toma M., Starling R.C. Inotropic therapy for end-stage heart failure patients. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2010;12:409–419. doi: 10.1007/s11936-010-0090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gheorghiade M., Marti C.N., Sabbah H.N., et al. for the Academic Research Team in Heart Failure Soluble guanylate cyclase: a potential therapeutic target for heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18:123–134. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9323-1. d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Poole-Wilson P.A. Commentary on the Carvedilol or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(suppl):40B–42B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otterstad J.E., Ford I. The effect of carvedilol in patients with impaired left ventricular systolic function following an acute myocardial infarction. How do the treatment effects on total mortality and recurrent myocardial infarction in CAPRICORN compare with previous beta-blocker trials? Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4:501–506. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.