Abstract

Background:

New targeted anticancer therapies often benefit only a subset of patients with a given cancer. Definitive evaluation of these agents may require phase III randomized clinical trial designs that integrate evaluation of the new treatment and the predictive ability of the biomarker that putatively determines the sensitive subset.

Purpose:

We propose a new integrated biomarker design, the Marker Sequential Test (MaST) design, that allows sequential testing of the treatment effect in the biomarker-subgroups and overall population while controlling the relevant type I error rates.

Methods:

After defining the testing and error framework for integrated biomarker designs, we review the commonly used approaches to integrated biomarker testing. We then present a general form of the MaST design and describe how it can be used to provide proper control of false-positive error rates for biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups. The operating characteristics of the MaST design are compared by analytical methods and simulations to the sequential subgroup-specific design that sequentially assesses the treatment effect in the biomarker subgroups. Practical aspects of MaST design implementation are discussed.

Results:

The MaST design is shown to have higher power relative to the sequential subgroup-specific design in situations where the treatment effect is homogeneous across biomarker subgroups, while preserving the power for settings where treatment benefit is limited to biomarker-positive subgroup. For example, in the time-to-event setting considered with 30% biomarker-positive prevalence, the MaST design provides up to a 30% increase in power in the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups when the treatment benefits all patients equally, while sustaining less than a 2% loss of power against alternatives where the benefit is limited to the biomarker-positive subgroup.

Limitations:

The proposed design is appropriate for settings where it is reasonable to assume that the treatment will not be effective in the biomarker-negative patients unless it is effective in the biomarker-positive patients.

Conclusion:

The MaST trial design is a useful alternative to the sequential subgroup-specific design when it is important to consider the treatment effect in the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups.

Introduction

Many new anticancer therapies are molecularly targeted and therefore may only benefit a subgroup of a histologically defined population. Efficient development of these agents depends on the availability of predictive biomarkers that can identify a sensitive subpopulation. Based on the earlier development of the agent (e.g., a phase II trial [1]), if one is confident that the biomarker-negative patients will not be helped by the targeted therapy, then an enrichment phase III trial design, which randomizes only biomarker-positive patients, is appropriate [2,3]. However, at the time the definitive phase III trial is designed, there is often uncertainty about whether the treatment benefit, if any, extends to biomarker-negative patients. In this case, the phase III trial design should integrate treatment and biomarker evaluation [4,5].

A clinically useful predictive biomarker differentiates the patient population into a subgroup that benefits from the therapy versus the remaining population where the benefit is insufficient for the therapy to be recommended. Integrated phase III designs should provide reliable assessment of the risk-to-benefit ratio in each of the biomarker-defined subgroups to allow informed treatment recommendations for each subgroup. A direct way to address this is to use a parallel subgroup-specific design that evaluates treatment effects separately in the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative populations. When the biomarker can effectively separate patients who sufficiently benefit versus patients who do not, this approach provides direct evidence on the clinical utility of the biomarker. However, the subgroup-specific design has less power (than a design that uses an overall comparison) for detecting treatment benefit when the treatment effect is homogeneous across the biomarker subgroups.

This relative lack of power against a homogeneous treatment effect motivated use of designs that take an indirect approach to integrating treatment/biomarker evaluation by formally assessing treatment benefit in the overall population and in the biomarker-positive patients but not in the biomarker-negative patients. These designs have improved power under a homogeneous treatment effect and may be useful when the evidence for the predictive ability of the biomarker is weak. However, they may have a high probability of recommending the treatment for biomarker-negative patients when the treatment has no benefit in that subgroup [6]. To address this concern, Freidlin et al. [7] proposed an alternative design that incorporates analyses of the biomarker-subgroups and overall population while reducing the false-positive error rate for biomarker-negative patients. In this paper we restrict attention to situations where it is appropriate to control false-positive rates for both biomarker subgroups, e.g., when the evidence for the predictive ability of the biomarker is relatively strong.. Within this framework we define a general form of the design proposed in Freidlin et al [7], which we denote the Marker Sequential Test (MaST) design, and describe how the MaST design can be used to control false-positive error rates at a pre-specified level.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we briefly review existing integrated biomarker designs. Next we introduce the general form of the MaST design and describe how to adjust its design parameters to provide a proper control of the false-positive error rate for both the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups. We then compare power characteristics of the MaST and the subgroup-specific designs. The handling of unavailable biomarker data and interim monitoring of trial results using the MaST design are then discussed. We end with a discussion of why the MaST design works well.

Goal of an Integrated Biomarker Clinical Trial

The goal of an integrated biomarker clinical trial is to establish whether the new treatment improves clinical outcome in each biomarker subgroup. This implies testing two subgroup-specific null hypotheses and against the corresponding subgroup-specific superiority alternative hypotheses and , where and are treatment effects in the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups, respectively. (The alternative treatment effects are parameterized to have positive values correspond to benefit.) In theory, there are three possible null hypotheses that could be considered in the evaluation of a design type I error structure: (a) global null: , (b) and (c) . However, an implicit assumption in the biomarker setting is that when the new treatment does not work in biomarker-positive patients it also does not work in the biomarker-negative patients (i.e. if is true then is true). Therefore, we will only require control of type I error rate under the null hypotheses and Specifically, we want (1) the probability of rejecting either or under the global null hypothesis to be , and (2) the probability of rejecting under to be for all possible values of .

In addition to testing the two subgroup-specific null hypotheses, one could consider as part of an analysis approach using the overall study population to test the global null hypothesis against a homogeneous alternative , where denotes the overall treatment effect (as would be done in a traditional trial that ignores the biomarker). If this test rejected the null hypothesis, the treatment would be recommended for all patients, regardless of biomarker status.

Commonly used biomarker designs

A direct way to provide integrated evaluation of a new treatment and the corresponding biomarker is to use a parallel subgroup-specific design that tests treatment effect separately in the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative populations (sometimes referred to as a biomarker-stratified design [4]). A common approach to controlling the type I error at level in this design is to use a Bonferroni correction: allocate the between the tests of the null hypotheses of no treatment effect in each of the biomarker subgroups (e.g., with one could use .015 level for testing and .01 level for testing ). As was mentioned above, in the biomarker settings it is typically assumed that if treatment does not work in the biomarker-positive patients then it also does not work in the biomarker-negative patients. Therefore, a sequential version of the subgroup-specific design is often used to improve design efficiency: First test for the treatment effect in the biomarker-positive patients using the significance level ; if this test is significant, then test the treatment effect in the biomarker-negative patients using the same (see, e.g. Ref [8]).

It can be easily seen that for both the parallel and sequential versions of the subgroup-specific design (1) the probability of rejecting either or under the global null hypothesis and (2) the probability of rejecting under is less than or equal to . While it is not required here, it is useful to note that subgroup-specific designs also provide -level control of the probability of rejecting under .

A commonly used alternative design takes an indirect approach to integrating treatment/biomarker evaluation by testing the treatment effect in the overall population and in the biomarker-positive patients, but not in the biomarker-negative patients. In a parallel version of this overall/biomarker-positive approach, the treatment effect is assessed in both the overall population and the biomarker-positive patients, with type I error typically controlled by allocating between the tests of the null hypothesis in the overall population and in the biomarker-positive subgroup (see, e.g. Ref. [9]). There are two sequential versions of the overall/biomarker-positive design. One is the fall-back design [10]: first test the overall population using the reduced significance level , if the test is significant consider the treatment effective in the overall population; if the overall test is not significant then test the treatment effect in the biomarker-positive subgroup using an level test. This design may be useful when the rationale for the biomarker is weak (that is, the treatment is expected to be broadly effective), and the fall-back analysis of the biomarker-positive patients is designed to cover a less likely contingency that the benefit is limited to a relatively small biomarker subgroup (or when the biomarker is developed only if the overall test is not significant [11].) For the other sequential version, first test the biomarker-positive subgroup using significance level ; if the test is significant then test the treatment effect in the overall population using the same (see, e.g. Ref. [12]). These overall/biomarker-positive designs control the probability of rejecting either or under the global null at level . However, these designs do not control the probability of rejecting when the treatment only works in biomarker-positive patients (). In fact, the probability of erroneously recommending the new treatment for biomarker-negative patients can be very large if the treatment works very well in the biomarker-positive patients. Therefore the overall/biomarker-positive designs do not meet our type I error requirement and will not be considered further here.

MaST design

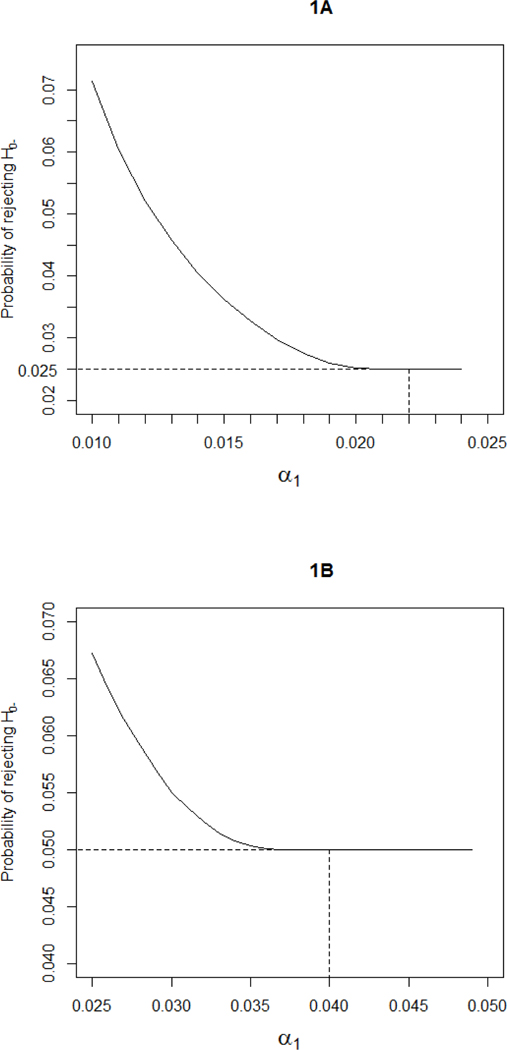

We consider settings where, a priori, one cannot rule out possible treatment benefit in biomarker-negative patients. In that context, the sequential subgroup-specific design has less power to find any treatment effect than a traditional overall test of the entire population when the new treatment has similar benefit across the biomarker subgroups. To improve power for such homogeneous treatment effects while controlling the probability of false-positive results in the biomarker-negative subgroup, the design has been proposed [7]. This design sequentially tests the treatment effect in the subgroups and the overall population. First, the biomarker-positive subgroup is tested at a reduced level . (a) If it is significant then the biomarker-negative subgroup is tested at the level . (b) If the biomarker-positive subgroup test is not significant, then the overall population is tested at the level. For any choice of (in ) the design controls the probability of rejecting or under the global null at level . Moreover, because the MaST design only tests the overall population when no significant effect is detected in the biomarker-positive subgroup, the probability of erroneously concluding overall benefit when the overall effect is driven by the biomarker-positive patients is minimized. The probability of incorrectly rejecting depends on the choice of . Figure 1 presents the upper bound (over all possible values of biomarker-positivity prevalence and biomarker-positive subgroup treatment effects ) of the probability of rejecting under as a function of for and 0.05. Using for controls the false positive error rate for biomarker-negative patients at .025, and using for controls the false positive error rate for biomarker-negative patients at .05. We recommend using for , MaST(.025,.022) in our notation, and for (MaST(.05,.04)).

Figure 1:

The maximum probability of rejecting under , over all possible values of biomarker-positivity prevalence and biomarker-positive subgroup treatment effects , as a function of : (A) MaST(0.025, ), designs with control the false-positive error rate for biomarker-negative patients at 0.025 level; (B) MaST(0.05, ), designs with control the false-positive error rate for biomarker-negative patients at 0.05 level.

Comparison of MaST and Sequential group-specific design

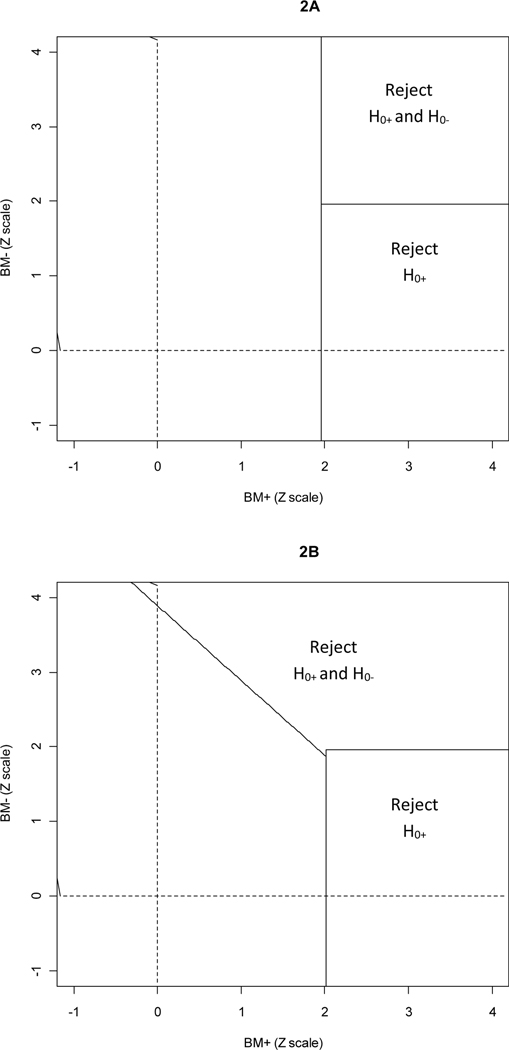

To motivate advantages of the MaST approach it is instructive to consider the rejection regions for the relevant designs. Figure 2 presents rejection regions for the 0.025-level sequential subgroup-specific design and the MaST(.025, .022) design. In the first stage, the MaST(.025, .022) design uses a slightly reduced significance level for testing the biomarker-positive subgroup (.022 for MaST versus .025 for subgroup-specific) – this is reflected by the vertical border of the rejection region for MaST design being slightly to the right of that for the subgroup-specific design (it will be shown below that this results in negligible loss of power in settings where the benefit is limited to the biomarker-positive patients). On the other hand, MaST’s sequential use of the overall test (in cases where no strong benefit is detected in the biomarker-positive subgroup) allows it to borrow power across subgroups as is reflected by larger rejection region for and that includes points with moderate effect in both biomarker subgroups.

Figure 2:

Rejection regions on the standardized Z-scale: (A) Sequential subgroup-specific 0.025-level design; (B) MaST(0.025,0.022) design, assuming 50% biomarker-positive prevalence.

To compare power characteristics of the sequential subgroup-specific design and the proposed MaST design, we tabulated powers of these tests under various treatment effect and biomarker prevalence scenarios. In Table 1, normally distributed outcomes analyzed with z-statistic are assumed; the results are obtained using numerical integration. (Note that these results can be considered as an asymptotic approximation for any setting that uses asymptotically normal tests.) The first two columns of Table 1 give the true treatment effects in biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups. The effects are given in units corresponding to an effect that gives 90% power in the biomarker-positive subgroup assuming 50% biomarker positive prevalence. The next two columns give the probability of rejecting a null hypothesis by a .025 level test in the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups. The fifth column gives the power of a traditional overall-effect design that compares the two treatment arms without the use of the biomarker. Powers for rejecting and are given for the sequential subgroup-specific and MaST designs in the last four columns. It can be seen that for situations where the treatment effect is limited to the biomarker-positive patients the MaST design preserves the power to detect the benefit in the biomarker-positive subgroup relative to the sequential subgroup-specific design (<2% reduction in power). On the other hand, the MaST design provides substantial improvement in power when the treatment is efficacious in both biomarker–subgroups. For example, consider a setting where the treatment effect is the same in all patients with the effect magnitude corresponding to 60% power for a .025 test in each subgroup (row 8 of Table 1). Use of the MaST design (compared to the sequential subgroup-specific design) would increase the power in the biomarker-positive subgroup from 60% to 74% and power in the biomarker-negative subgroup from 36% to 51%. Table 1 also illustrates that the MaST(.025,.022) design controls type I error rates at the .025 level.

Table 1:

Operating characteristics of the Sequential Subgroup-specific design versus The MaST(.025,.022) design: Normally distributed data

| True treatment effects in subgroups* | Powers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual 0.025 level tests | Overall test ignoring biomarker | Sequential subgroup-specific design | MaST(.025,.022) | |||||

| BM+ | BM- | BM+ | BM- | BM+ | BM- | BM+ | BM- | |

| Biomarker-positive prevalence 50% | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | .0250 | .0250 | .0250 | .0250 | .0006 | .0233 | .0018 |

| 1 | 0 | .9000 | .0250 | .6301 | .9000 | .0225 | .8916 | .0237 |

| .683 | 0 | .6000 | .0250 | .3465 | .6000 | .0150 | .5829 | .0185 |

| .443 | 0 | .300 | .025 | .1724 | .3000 | .0075 | .2859 | .0114 |

| 1 | 1 | .9000 | .9000 | .9957 | .9000 | .8100 | .9976 | .8885 |

| 1 | .683 | .9000 | .6000 | .9711 | .9000 | .5400 | .9399 | .5838 |

| 1 | .443 | .9000 | .3000 | .9110 | .9000 | .2700 | .9119 | .2888 |

| .683 | .683 | .6000 | .6000 | .8790 | .6000 | .3600 | .7366 | .5050 |

| .683 | .443 | .6000 | .3000 | .7324 | .6000 | .1800 | .6438 | .2385 |

| .443 | .443 | .3000 | .3000 | .5280 | .3000 | .0900 | .3607 | .1637 |

| Biomarker-positive prevalence 25% | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | .0250 | .0250 | .0250 | .0250 | .0006 | .0241 | .0027 |

| 1.414 | 0 | .9000 | .0250 | .3672 | .9000 | .0225 | .8916 | .0236 |

| .966 | 0 | .6000 | .0250 | .1967 | .6000 | .0150 | .5831 | .0186 |

| .626 | 0 | .3000 | .0250 | .1071 | .3000 | .0075 | .2866 | .0121 |

| 1.414 | 1.414 | .9000 | 1 | .9999 | .9000 | .8999 | .9999 | .9998 |

| 1.414 | .966 | .9000 | .9695 | .9986 | .9000 | .8726 | .9926 | .9655 |

| 1.414 | .626 | .9000 | .7007 | .9652 | .9000 | .6307 | .9536 | .6871 |

| .966 | .966 | .6000 | .9695 | .9932 | .6000 | .5817 | .9613 | .9436 |

| .966 | .626 | .6000 | .7007 | .9032 | .6000 | .4204 | .7992 | .6259 |

| .626 | .626 | .3000 | .7007 | .8189 | .3000 | .2102 | .6087 | .5244 |

| Biomarker-positive prevalence 75% | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | .0250 | .0250 | .0250 | .0250 | .0006 | .0224 | .0009 |

| .816 | 0 | .9000 | .0250 | .8016 | .9000 | .0225 | .8909 | .0230 |

| .558 | 0 | .6000 | .0250 | .4828 | .6000 | .0150 | .5807 | .0162 |

| .362 | 0 | .3000 | .0250 | .2368 | .3000 | .0075 | .2832 | .0088 |

| .816 | .816 | .9000 | .4647 | .9627 | .9000 | .4183 | .9139 | .4374 |

| .816 | .558 | .9000 | .2476 | .9314 | .9000 | .2228 | .9006 | .2308 |

| .816 | .362 | .9000 | .1290 | .8965 | .9000 | .1161 | .8949 | .1195 |

| .558 | .558 | .6000 | .2476 | .7243 | .6000 | .1486 | .6063 | .1707 |

| .558 | .362 | .6000 | .1290 | .6448 | .6000 | .0774 | .5910 | .0867 |

| .362 | .362 | .3000 | .1290 | .3812 | .3000 | .0387 | .2940 | .0488 |

Treatment effects are given in units corresponding to treatment effect that has 90% power for biomarker-positive subgroup assuming 50% biomarker positive prevalence

Many definitive phase III studies use a time-to-event endpoint. To illustrate the relevance of the asymptotic results in Table 1, Table 2 presents the operating characteristics of the MaST and the sequential subgroup-specific design in this setting (obtained by simulation). The results are presented for 30% biomarker positivity. Similar to the results of Table 1, the MaST design is shown to preserve the power (less than 2% loss) against alternatives where the benefit is limited to the biomarker-positive subgroup. At the same time, the MaST design provides considerable improvement in power when the treatment effect is present in both biomarker-subgroups. For example, when the new treatment produces a 29% reduction in the hazard of an event (hazard ratio=.71) regardless of biomarker status, then use of the MaST design (relative to the subgroup-specific design) increases the power from 60% to 92% in the biomarker-positive subgroup and from 55% to 87% in the biomarker-negative subgroup (row 8 of Table 2).

Table 2.

Power of the Sequential Subgroup-specific design vs. MaST(.025,.022) design, with 30% biomarker-positive prevalence: time-to-event data*

| True treatment effects in subgroups: hazard ratio (experimental/control) | Powers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual 0.025 level tests | Overall test ignoring biomarker | Sequential subgroup-specific design | MaST(.025,.022) | |||||

| BM+ | BM- | BM+ | BM- | BM+ | BM- | BM+ | BM- | |

| 1 | 1 | .0256 | .0257 | .0249 | .0256 | .0007 | .0241 | .0025 |

| .60 | 1 | .902 | .0253 | .469 | .902 | .023 | .894 | .024 |

| .71 | 1 | .600 | .0252 | .243 | .600 | .015 | .584 | .019 |

| .80 | 1 | .301 | .0255 | .125 | .301 | .007 | .288 | .012 |

| .60 | .60 | .902 | .998 | 1 | .902 | .901 | .999 | .998 |

| .60 | .71 | .902 | .930 | .997 | .902 | .839 | .985 | .923 |

| .60 | .80 | .902 | .624 | .960 | .902 | .563 | .947 | .611 |

| .71 | .71 | .600 | .920 | .981 | .600 | .552 | .921 | .874 |

| .71 | .80 | .600 | .608 | .870 | .600 | .365 | .759 | .531 |

| .80 | .80 | .301 | .596 | .748 | .301 | .178 | .533 | .417 |

The trial designs assume accrual rate of 20 patient per month with accrual continuing until 250 biomarker-positive patients are enrolled. Median survival in the control arm is 10 months regardless of biomarker status. The trial is analyzed when 164 events are observed in biomarker-positive subgroup (164 events give 90% power at .025 one-sided significance level for the HR .6 in the biomarker-positive subgroup). Results are based on 100,000 simulations.

Unavailable biomarker status

In many clinical trials biomarker status will be unavailable in a fraction of study patients. This could be because of logistical reasons (e.g., no specimen submitted), technical reasons (e.g., inadequate specimen or assay failure), or clinical reasons (e.g., tumor inaccessible or too small to be biopsied). The subgroup-specific designs do not use these patients in the analyses. For the MaST design there are two options: (1) do not include patients with unavailable biomarker status or (2) include these patients in the overall test. Option 1 is straightforward and does not require any statistical adjustment (albeit it forgoes some information). Option 2 is potentially attractive because it allows some use of the information from patients with unavailable biomarker status. However, presence of such patients alters the correlation structure between subgroup-specific and overall tests and thus may inflate false-positive rate for the biomarker-negative subgroup above the nominal level, even when biomarker status is missing completely at random. For example, when the MaST(.025, .022) design is used with 50% biomarker positivity and 20% of patients have unavailable biomarker status then, assuming a missing completely at random mechanism for biomarker unavailability, the probability of rejecting under could be as high as .030 instead of .025. (Note that the probability of falsely rejecting is always controlled under in the MaST design.)

In theory, if one is willing to assume a missing-completely-at-random mechanism for biomarker unavailability (i.e., a simple random sample of patients in the population have unavailable biomarker status), then one could adjust the MaST design to control the type I error rate. For example, to approximately control this type I error, the following adjustment for the significance level could be used for the overall test:

where is the proportion of unavailable biomarker values and is the power of the overall test when the treatment is effective only in the biomarker-positive patients with 90% power in that subgroup. However, this adjustment results in a design with power characteristics very similar to option 1 which does not use patients with unavailable biomarker values. Moreover, the missing-completely-at-random assumption cannot generally be verified and if it is violated, the adjustment does not control the error rate. Therefore, we would generally not recommend using patients with unavailable biomarker values in the MaST design.

Interim monitoring

Most large randomized clinical trials incorporate interim monitoring for early evidence of efficacy or futility/inefficacy. For the MaST design, interim monitoring could be conducted as follows. For efficacy monitoring, first test the biomarker-positive subgroup to see if the efficacy boundary is crossed in that subgroup. If the biomarker-positive efficacy boundary is crossed then test whether biomarker-negative subgroup efficacy boundary is crossed. If the biomarker-positive subgroup efficacy boundary is not crossed, the biomarker-negative subgroup is not evaluated for efficacy stopping at that time point. We recommend truncated O’Brien-Fleming boundaries [13] using the Lan-DeMets spending function approach [14], with and levels for the biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative subgroups, respectively. In theory, to mimic the MaST testing sequence, one could consider adding interim monitoring on the overall population if the biomarker-positive subgroup did not cross its efficacy boundary. However, we would not generally recommend this because it may interfere with validating clinical utility of the biomarker.

For futility/inefficacy monitoring: the biomarker subgroups should be monitored separately as follows. If the biomarker-positive subgroup crosses its inefficacy boundary, then the entire study should be stopped. If the biomarker-negatives subgroup crosses its inefficacy boundary then that subgroup is stopped. In each subgroup the inefficacy boundary should be chosen based on the power and significance level used in that subgroup using, for example, using the approach described in Freidlin et al [15].

Discussion

When the MaST design is compared to the sequential subgroup-specific design, there is a minor (and arguably negligible) loss of power under the alternatives where the treatment benefit is limited to the biomarker-positive patients. In addition, while both designs control the probability of falsely rejecting at the designated level , the sequential subgroup-specific design typically has a smaller probability of rejecting (when true) compared to the MaST design, especially under the global null (e.g., .006 vs .018 in first row of Table 1). This conservativeness of sequential subgroup-specific design, which is due to its sequential nature, is contributing to MaST’s advantage. This can be seen by considering the rejection regions in Figure 2, where the MaST design trades a small vertical strip for rejecting for a much larger triangular region that rejects both and We are not aware of any simple way of making the sequential design less conservative without relinquishing control of the probability of rejecting under . (In particular, use of parallel subgroup-specific design that allocates the between the subgroup-specific tests does not improve subgroup-specific design performance in the relevant settings). It should also be noted that, in theory, by manipulating the shapes of the rejection regions for and for and in Figure 2B, one could further optimize power against a specific family of alternatives. This however, would likely result in a complex design with no simple clinical motivation.

In the settings considered here, when the a priori evidence for the predictive ability of the biomarker is relatively strong, sample size considerations are driven by the need to have sufficient number of biomarker-positive patients to detect a clinically meaningful effect in that subgroup. Therefore, a standard sample size calculation can be used for MaST design. If one is willing to accept the minor loss of power (when benefit is limited to the biomarker-positive subgroup), then one can use the same calculation that would be used to size a sequential subgroup-specific design. In particular, the size of the biomarker-positive subgroup is determined using and the desired power for a clinically meaningful treatment effect. Alternatively, to achieve the desired power exactly, one can calculate sample size of the biomarker-positive subgroup using (instead of ). This results in only a minor increase in sample size compared to the corresponding sequential subgroup-specific design: e.g., for , less than a 4% increase in sample size. (Note that sample size for the overall trial can be calculated as the sample size calculated for the biomarker-positive subgroup divided by biomarker-positivity prevalence.)

It should be noted that the MaST design was developed to increase the power against alternatives where the treatment effect is homogeneous across the biomarker-subgroups (while controlling the appropriate false-positive error rates), rather than to decrease the sample size of the study (which it does not do). For example, in the time-to-event setting with 30% prevalence of biomarker-positivity (Table 2), both the MaST and sequential subgroup-specific procedures could be designed targeting a hazard ratio 0.6 in the biomarker-positive subgroup with 90% power and : this can be achieved by continuing accrual until 250 biomarker-positive patients have been enrolled (with an average of 583 biomarker-negative patients enrolled). In this case, use of the MaST design would provide a dramatic improvement in the study ability to detect treatments that benefit all patients while preserving power for treatments that benefit only the biomarker-positive patients.

Typically, when a trial is being designed, there is some uncertainty about the prevalence of the biomarker-positivity. Therefore, the MaST procedure is designed to control the false-positive error rates for the biomarker-negative subgroup over all possible prevalence values. Theoretically, if one can narrow the range of possible prevalence values, then a smaller value of could be used. However, the decrease in would be small unless the prevalence range could be restricted to extreme values (<20% or >80%).

As we stated earlier, a key assumption inherent in the biomarker designs is that when a new treatment does not work in the biomarker-positive patients then it also does not work in the biomarker-negative patients. This assumption is central in justifying our requirement for type I error control: controlling the false-positive error rate under the global null and the false-positive error rate under but not controlling the false-positive error rate under . This requirement is satisfied by the subgroup-specific designs, and we show that it is also satisfied by the MaST design with a proper choice of . However, it is instructive to note that unlike the subgroup-specific designs, the MaST design does not control type I error under . While we believe that this is acceptable in the biomarker settings considered here, it may be an important consideration in other applications. An alternative approach to integrating treatment and biomarker evaluation while minimizing type I error rates in the biomarker positive and negative subgroups is proposed by Karuri and Simon [16] using a two-stage Bayesian design.

To summarize, the MaST approach structures sequential evaluation of biomarker-subgroups and the overall study population to limit testing of the overall population to situations where no strong signal is observed in the biomarker-positive subgroup. This improves the power of MaST as compared to the subgroup-specific design in situations where the treatment effect is homogeneous by allowing borrowing power across biomarker subgroups. At the same time, the MaST design is shown to preserve the power for settings where treatment benefit is limited to biomarker-positive subgroup and to control the relevant type I error rates.

Footnotes

Research Support: None

References

- 1.Freidlin B, McShane LM, Polley MY, et al. Randomized phase II trial designs with biomarkers. J Clin Oncol 30:3304–9, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon R, Maitournam A. Evaluating the efficiency of targeted designs for randomized clinical trials. Clinical Cancer Research 10:6759–63, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enrichment strategies for clinical trials to support approval of human drugs and biological products. FDA Draft Guidance; 2012. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM332181.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freidlin B, McShane LM, Korn EL. Randomized clinical trials with biomarkers: design issues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 102:152–60, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon R. Clinical trials for predictive medicine. Statist Med 31:3031–40, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothmann MD, Zhang JJ, Lu L et al. Testing in a prespecified subgroup and the intent-to-treat population. Drug Inf J 46:175–179, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freidlin B, Sun Z, Gray R, et al. Phase III clinical trials that integrate treatment and biomarker evaluation. J Clin Oncol April 8 2013. [E-published ahead of print]. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol 28:4697–705, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 11:521–9, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon R. The use of genomics in clinical trial design. Clin Cancer Res 14:5984–5993, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freidlin B, Simon R. Adaptive signature design: an adaptive clinical trial design for generating andprospectively testing a gene expression signature for sensitive patients. Clin Cancer Res 11:7872–8, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston S, Pippen J Jr, Pivot X, et al. , Lapatinib combined with letrozole versus letrozole and placebo as first-line therapy for postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:5538–46, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials.Biometrics. 35(3):549–56, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan KK, DeMets DL. Changing frequency of interim analysis in sequential monitoring.Biometrics. 45(3):1017–20, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freidlin B, Korn EL, Gray R. A general inefficacy interim monitoring rule for randomized clinical trials.Clin Trials. 7(3):197–208, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karuri SW, Simon R. A two-stage Bauesian design for co-development of new drugs and companion diagnostics. Statist Med 31:901–904 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]