Abstract

N2-Monomethylguanosine-10 (m2G10) and N2,N2-dimethylguanosine-26 (m22G26) are the only two guanosine modifications that have been detected in tRNA from nearly all archaea and eukaryotes but not in bacteria. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, formation of m22G26 is catalyzed by Trm1p, and we report here the identification of the enzymatic activity that catalyzes the formation of m2G10 in yeast tRNA. It is composed of at least two subunits that are associated in vivo: Trm11p (Yol124c), which is the catalytic subunit, and Trm112p (Ynr046w), a putative zinc-binding protein. While deletion of TRM11 has no detectable phenotype under laboratory conditions, deletion of TRM112 leads to a severe growth defect, suggesting that it has additional functions in the cell. Indeed, Trm112p is associated with at least four proteins: two tRNA methyltransferases (Trm9p and Trm11p), one putative protein methyltransferase (Mtc6p/Ydr140w), and one protein with a Rossmann fold dehydrogenase domain (Lys9p/Ynr050c). In addition, TRM11 interacts genetically with TRM1, thus suggesting that the absence of m2G10 and m22G26 affects tRNA metabolism or functioning.

tRNAs are transcribed as precursor molecules by RNA polymerase III, then the primary transcripts undergo posttranscriptional maturation before becoming functional. tRNA maturation includes the removal of leader and trailer sequences, the addition of a CCA at the 3′ end, sometimes the splicing of an intron, and the modification of numerous nucleotides (34, 42, 57). In yeast tRNA, modified nucleotides are detected at 35 different positions out of 76. They are formed posttranscriptionally and require various types of enzymatic activities such as 2′-O-ribose methyltransferases (MTases), base MTases, pseudouridylases, deaminases, thiolases, reductases, and oxidases. Base and ribose methylations are by far the most frequent modifications in tRNA (26, 57). In yeast, cytoplasmic tRNAs sequenced so far contain 15 methylated bases and five 2′-O-methylriboses, while mitochondrially encoded tRNA possess only 4 methylated bases, none of which are unique to mitochondria (57). It is likely that the formation of all these methylated nucleotides is catalyzed by unisite- or multisite-specific MTases. The first identified yeast tRNA MTase (Trm) Trm1p, is required for the formation of N2,N2-dimethylguanosine at position 26 (m22G26) in cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA (19). Later, several tRNA MTases were identified, by either genetic screening, bioinformatic analysis, or biochemical genomics (34). Out of the 10 tRNA MTases that have been characterized to date in yeast, only Trm6p and Trm61p, which form a heterodimer required for the formation of m1A58, are essential for cell growth (2). Deletion of either TRM5 or TRM7 leads to a severe growth defect (8, 51), while the genes encoding other Trm proteins can be deleted without apparent cell growth defects under laboratory conditions.

With the exception of only one tetrahydrofolate-dependent enzyme (17), all known MTases acting on nucleic acids use S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) as a cofactor (10, 14). Although AdoMet-dependent MTases can be classified into at least six unrelated superfamilies based on structural and evolutionary considerations (54), all DNA MTases and most RNA MTases belong to the largest class I of Rossmann fold-like MTases (RFMs) (11). A characteristic feature of these enzymes is the presence of nine common motifs that map onto the catalytic face of the common fold, with motifs I to III involved in AdoMet binding, and motif IV and often motifs VI, VIII, and X involved in binding to the target nucleotide and in methyl transfer reactions (20).

Using a combination of protein fold recognition and modeling-based identification of potential catalytic and RNA-binding residues, we previously identified 20 putative RNA MTases (termed MTase candidates or Mtcs) (14) and then tested their involvement in tRNA methylation. Here, we report the characterization of the activity responsible for the formation of m2G10 in yeast tRNA. The enzyme is composed of at least two subunits: Trm11p is the catalytic subunit that contains the RFM domain, and Trm112p shows similarity to an uncharacterized family of putative Zn-binding proteins. Trm112p appears to belong to a complex network of enzymatic activities, suggesting that it has additional functions in the cell. While preventing the formation of either m2G10 or m22G26 did not measurably affect cell growth rate under laboratory conditions, preventing the formation of both led to a growth defect. This result suggests that, for some tRNAs, these two modifications act coordinately to permit efficient tRNA synthesis or functioning.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbiological methods and recombinant DNA work.

Yeast cells were grown, handled, and transformed as previously described (23, 28). The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. A trm11::kanMX4 cassette was amplified using primers OBL197 and OBL198 (oligonucleotides used in this study are listed on Table 2), and genomic DNA was prepared from strain yol124c::kanMX4 (strain S288c; Euroscarf, Frankfurt, Germany). Then, the purified PCR fragment was transformed into strain BMA64 (a derivative of W303 provided by F. Lacroute) to delete the TRM11 gene. trm112-0 and mtc6-0 (ynr046w::kanMX4 and ydr140w::kanMX4; Euroscarf) were also transferred to BMA64 using primer pairs OBL254-OBL255 and OBL185-OBL186, respectively. TRM9 was deleted in BMA64 by a PCR-based method (6) with primers OBL163-OBL164 and pRS314 as a template (55). Similarly, TRM1 and LYS9 were deleted with OBL230-OBL231 and OBL250-OBL251, respectively, and pRS316 as a template (55). TRM11 was tagged with the tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag using primers OBL238-OBL239 and pBS1479 as a template (53) and transformed into BMA64. The TRM11-TAP gene was amplified using genomic DNA and primers OBL236-OBL237 and cloned into the SphI and KpnI sites of pFL39 (9) to yield pBL640. Point mutations on the TRM11-TAP gene were constructed with a QuikChange kit (Stratagene) using pBL640 as a template and primers OBL244-OBL245 (to yield pBL645) and primers OBL246-OBL247 (to yield pBL646). Strain YBL4663 (trm112-0) was made by backcrossing a haploid strain obtained from the sporulation of Y25421 (Euroscarf) four times with BMA64. The TRM112 gene was amplified with primers OBL254-OBL282 and cloned as an SphI-KpnI fragment into pFL39 to yield pBL652, which was then used to complement YBL4663 to yield YBL4665.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Plasmid | Main property | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMA64-1A | MATaa | 6 | ||

| ZZ-Nop1p | MATα nop1-0::HIS3a | pZZ-Nop1p | 21 | |

| YBL4494 | MATα trm7-0::TRP1a | pBL598 | TRM7-ZZ | 51 |

| Y16274 | MATayol124c::kanMX4b | trm11-0 | Euroscarf | |

| YBL4577 | MATα trm11-0::kanMX4a | trm11-0 | This work | |

| Y14074 | MATaydr140w::kanMX4b | mtc6-0 | Euroscarf | |

| YBL4586 | MATα ydr140w::kanMX4a | mtc6-0 | This work | |

| YBL4557 | MATatrm9-0::TRP1a | trm9-0 | This work | |

| YBL4589 | MATα lys9-0::URA3a | lys9-0 | This work | |

| YBL4581 | MATatrm1-0::URA3a | trm1-0 | This work | |

| YBL4580 | MATα TRM11::TAP-TRP1a | Trm11-TAPp (chromosome) | This work | |

| YBL4588 | MATα trm11-0::kanMX4a | pBL640 | Trm11-TAPp (plasmid) | This work |

| YBL4597 | MATα trm11-0::kanMX4a | pBL645 | Trm11(D215A)-TAP | This work |

| YBL4598 | MATα trm11-0::kanMX4a | pBL646 | Trm11(D291A)-TAP | This work |

| YBL4583 | MATatrm1-0::URA3/trm11-0::kanMX4a | trm1-0 trm11-0 | This work | |

| Y25421 | MATa/α trm112::kanMX4/TRM112b | TRM112/trm112-0 | Euroscarf | |

| YBL4663 | MATatrm112::kanMX4a | trm112-0 | This work | |

| YBL4665 | MATatrm112::kanMX4a | pBL652 | TRM112 | This work |

| SC1438 | MATaYNR046w::TAP-Kl URA3c | Trm112-TAPp | Euroscarf | |

| YBL4634 | MATaTRM112::TAP-Kl URA3a | Trm112-TAPp | This work | |

| YBL4635 | MATaTRM112::TAP-Kl URA3 TRM11::TAP TRPa | Trm11-TAPp Trm112-TAPp | This work | |

| Ynr046w-YFP | MATa/α TRM112-YFP-kanMX4d | Trm112-YFPp | 31 | |

| YBL4689 | MATaTRM11-TAP TRM112-YFPa | Trm11-TAPp Trm112-YFPp | This work |

Other markers are ade2-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-0 can1-100.

Other markers are his3Δ1 leu2-0 lys2-0 MET15/met15-0 ura3-0.

Other markers are ade2 arg4 leu2-3,112 trp1-289 ura3-52.

Other markers are ade2-1oc ADE3/ade3-0 can1-100 CYH2s/cyh2r his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Name | Description | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| OBL163 | TRM9 deletion 5′ | ATTCGGTAATGAACTGAACAGAGATGAGGTCTCGAAGAGCCAAGAAATAACGGGTGTTGGCGGGTGTC |

| OBL164 | TRM9 deletion 3′ | CCTGCTGCTACAAAATACACTGTCTACCTATATATCACCTTCATCTCTTCCTGATGCGGTATTTTCTCCT |

| OBL185 | MTC6 5′ | TTCAGCTAAAAGTTGTTCG |

| OBL186 | MTC6 3′ | TGATTTATATGGTTGTGGTG |

| OBL197 | TRM11 5′ | TACCCGTAATATGGAGATG |

| OBL198 | TRM11 3′ | TTTTTCACTTGTATTTTTG |

| OBL230 | TRM1 deletion 5′ | TCGCAAAGTTACAGATCCTGAGCAGTCATAAGTTGATACCTTTCCTCTTACACGGGTGTTGGCGGGTGTC |

| OBL231 | TRM1 deletion 3′ | ATATATATTTATTTATTTTTTACACATACATACTGCCCTCCTGATTACTTCTGATGCGGTATTTTCTCCT |

| OBL236 | TRM11 cloning 5′ | AACTGCAGATTACAGTGGCGGAAAGGAG |

| OBL237 | TRM11 cloning 3′ | CCCAAGCTTAATGCGGAGCTGATAAGG |

| OBL238 | TRM11-TAP 5′ | TAAAACGTTCAAAAGATAATTTCAGGGAGCGGTACTTCAATAATTTTAACTCCATGGAAAAGAGAAG |

| OBL239 | TRM11-TAP 3′ | TTCTACATGATGGAACATAAACATAAATATAGGTATAGATAAATTGTTCTTACGACTCACTATAGGG |

| OBL244 | TRM11-D215A 5′ | GAACTATAATGTACGCCCCGTTTGCAGGTAC |

| OBL245 | TRM11-D215A 3′ | GTACCTGCAAACGGGGCGTACATTATAGTTC |

| OBL246 | TRM11-D291A 5′ | GATACTATTTTGTGTGCTCCTCCATATGGTA |

| OBL247 | TRM11-D291A 3′ | TACCATATGGAGGAGCACACAAAATAGTATC |

| OBL250 | LYS9 deletion 5′ | GTAGGGAAAACTTATCAGGACAATTGAGTTATATTAACGTATTATATATT CGGGTGTTGGCGGGTGTC |

| OBL251 | LYS9 deletion 3′ | AATAGCCAATACTTTTTAGACTAAAGGTAGACGACTTACTAGCGGTTCAACTGATGCGGTATTTTCTCCT |

| OBL254 | TRM112 5′ | AATCAGCATCCTCAAACT |

| OBL255 | TRM112 3′ | GTTGAAGGGAATCGTGTT |

| OBL282 | TRM112-TAP 3′ | ACATGCATGCGTTGAAGGGAATCGTGTT |

Nucleotides in boldface type correspond to the mutations that were introduced in TRM11.

Protein analysis, Western blotting, and immunofluorescence microscopy.

Native protein extracts were prepared as described previously (50), except that cells were broken in 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μg/ml pepstatine, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride supplemented with yeast protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bradford protein assay (Sigma). Protein fractionation on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, immunoblotting assays, and immunoprecipitation were carried out as described previously (50). For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were prepared according to reference 50. Immunodetection was achieved with fluorescent immunoglobulin Gs (IgGs) (Alexa 488; Molecular Probes); images were acquired with a Leitz microscope.

tRNA MTase activity assay.

In vitro testing for MTase activity was performed essentially as described previously (25, 37). A total of 50 to 100 fmol of in vitro-transcribed and purified [32P]tRNA were incubated at 30°C for 2 h in 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), 100 mM ammonium acetate, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μM S-adenosyl-l-methionine, and S10 extract (∼10 μg of protein). Modified tRNA was then extracted and digested with nuclease P1 (Roche), and the modified nucleotides were separated by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (2D-TLC) as described previously (25, 37). In vivo labeling with [32P]orthophosphate and purification of total yeast tRNA, prior to their analysis, was done according to references 25 and 60.

RESULTS

m2G10 formation requires the catalytic activity of Trm11p.

Mtc1p to Mtc20p were selected as putative RNA MTases in yeast (14). To test whether any of these candidates was involved in tRNA methylation, yeast strains deleted for the corresponding open reading frame (ORF) were constructed, and various tRNA modification activities were assayed in vitro using different synthetic tRNA as substrates. Cytoplasmic tRNAs contain five 2′-O-methylriboses at positions 4, 18, 32, 34, and 44 and 15 methylated bases at 12 different positions: 9, 10, 26, 32, 34, 37, 40, 46, 48, 49, 54, and 58 (Fig. 1A). Most of these modifications are achieved by unisite-specific enzymes, while there are also two multisite-specific enzymes, Trm4p (m5C MTase) (44) and Trm7p (2′-O-ribose MTase) (51). Up to now, 10 MTases have been characterized, which catalyze the formation of 14 methylated nucleotides, leaving six orphan positions: Am/Cm4, m2G10, m3C32, ncm5Um34, yW37 (probably two or three methyl groups), and Um44. In addition, two modifications have been reported previously that appear now as oddities compared to other known modifications: tRNALysCUU (Table 3, footnote b) was reported to have an m2G at position 9 (56), while all other yeast tRNA modified at that position have an m1G that is formed by Trm10p (36). Similarly, tRNAValCAC (Table 3, footnote b) was reported to contain an m2G at position 26 (24), while all other yeast tRNA modified at that position possess an m22G that is formed by Trm1p (19).

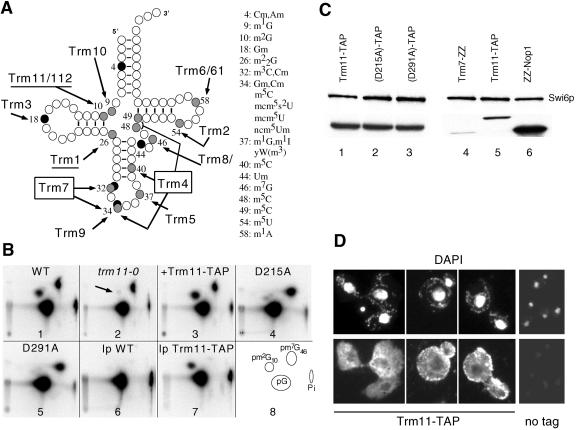

FIG. 1.

Trm11p is required for m2G10 formation in vitro. (A) Cloverleaf representation of yeast tRNA showing the position of methylated nucleotides. Black circles, 2′-O-methylriboses; shaded circles, methylated bases. The position and the nature of the modified nucleotides are listed on the right side of the figure. The 11 known tRNA MTase activities (including Trm11/Trm112) are shown, with their target(s). The sites of action of the two multisite specific enzymes, Trm4 and Trm7, have been boxed. (B) In vitro methylation analysis of [α-32P]GTP-radiolabeled intronless tRNAIleUAU, using S10 extracts prepared from various strains. Panels: 1, wild-type (BMA64); 2, trm11-0 (YBL4577); 3, trm11-0 plus Trm11-TAP (YBL4588); 4, Trm11-D215A-TAP mutant protein (YBL4597); 5, Trm11-D291A-TAP mutant protein (YBL4598); 6, control immunoprecipitation using a wild-type extract and IgG-Sepharose beads; 7, immunoprecipitation of Trm11-TAP (YBL4580); 8, reference map indicating the location of the three nucleotides of interest (pG, pm2G10, and pm7G46). Pi, inorganic phosphate. The arrow points to the m2G10 spot that is absent in the trm11-0 strain. The solvent system used for the TLC was NI/RII (37). (C) Western blot analysis of TAP-tagged proteins. Similar amounts of protein were loaded in each lane, as demonstrated by the detection of Swi6p (47), which is used here as a control. Comparison of the signal obtained for wild-type Trm11p (lane 1) and for the two mutant proteins D215A (lane 2) and D291A (lane 3) is shown. The signal obtained for Trm11-TAPp (lane 5) was compared with those obtained for Trm7-ZZp (lane 4) (51) and ZZ-Nop1p (lane 6) (21). (D) Immunofluorescence detection of Trm11-TAP in yeast cells. (Top) Cells were labeled with DAPI to visualize the structures containing DNA, nuclei and mitochondria (different fields with representative cells are shown). (Bottom) Fluorescent IgGs detect the S. aureus protein A fragment, expressed as a fusion with Trm11p. No tag, wild-type cells expressing no tagged protein (lower magnification).

TABLE 3.

Modified nucleotides at positions 9, 10, and 26 in yeast tRNAsa

| Name | Abundance | Anticodon | No. of genes | Position

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1G9 | m2G10 | m22G26 | ||||

| Ala | Minor | UGC | 5 | ND | ND | ND |

| Arg | Rare | CCU | 1 | ND | ND | ND |

| Arg | Rare | CCG | 1 | ND | ND | ND |

| Leu | Rare | GAG | 1 | ND | ND | ND |

| Thr | Minor | UGU | 4 | ND | ND | ND |

| Glu | Minor | CUC | 2 | ND | ND | A |

| Thr | Rare | CGU | 1 | ND | ND | U |

| Asp | Major | GUC | 16 | − | − | − |

| Cys | Major | GCA | 4 | − | − | − |

| Gln | Major | UUG | 7 | − | − | U |

| Gln | Minor | UUG | 2 | − | − | U |

| Gln | Rare | CUG | 1 | − | − | U |

| Glu | Major | UUC | 14 | − | − | A |

| Gly | Major | GCC | 16 | + | − | C |

| Gly | Minor | UCC | 3 | − | − | C |

| Gly | Minor | CCC | 2 | − | − | U |

| His | Major | GUG | 7 | − | − | A |

| Pro | Major | UGG | 10 | + | − | U |

| Pro | Minor | AGG | 2 | − | − | C |

| Val | Major | AAC | 14 | + | − | A |

| Ile | Major | AAU | 13 | + | + | C |

| Ile | Minor | UAU | 2 | − | + | U |

| Trp | Major | CCA | 6 | + | + | Ψ |

| Ala | Major | AGC | 11 | + | − | + |

| Lysb | Major | CUU | 14 | + | − | + |

| Ser | Major | AGA | 11 | − | − | + |

| Ser | Minor | GCU | 4 | − | − | + |

| Ser | Minor | UGA | 3 | − | − | + |

| Ser | Rare | CGA | 1 | − | − | + |

| Arg | Major | ACG | 6 | + | + | + |

| Arg | Major | UCU | 11 | + | + | + |

| Asn | Major | GUU | 10 | − | + | + |

| Leu | Major | CAA | 10 | − | + | + |

| Leu | Major | UAA | 7 | − | + | + |

| Leu | Minor | UAG | 3 | − | + | + |

| Lys | Major | UUU | 7 | − | + | + |

| Meti | Initiator | CAU | 5 | + | + | + |

| Met | Elongator | CAU | 5 | − | + | + |

| Phe | Major | GAA | 8 | − | + | + |

| Phe | Minor | GAA | 2 | − | + | + |

| Thr | Major | AGU | 11 | − | + | + |

| Tyr | Major | GUA | 8 | − | + | + |

| Val | Minor | UAC | 2 | − | + | + |

| Valb | Minor | CAC | 2 | − | + | ?? |

+, the modification is present at that position; −, the G at that position is not methylated. This table has been prepared according to reference 57. The number of genes for each tRNA is given according to references 30 and 43. For the first seven tRNAs, no information concerning the modification status is available, since these tRNAs have not yet been sequenced. ND, not determined; ??, uncertain.

These tRNAs (Lys, Val) are discussed in the text.

We selected intronless-tRNAIleUAU (59) as a template to test for m2G10 formation in vitro. When transcribed in the presence of [α-32P]GTP, this tRNA permits detection of the formation of m2G and m7G after incubation with a cellular extract prepared from a wild-type strain. No other methylated G is formed on this tRNA that contains a U at position 26, therefore preventing the formation of m22G at that position (49). Based on the sequence of this tRNA, we assumed that, in vitro, m2G is formed at position 10 and m7G is formed at position 46. These modifications are also found at these positions in numerous other yeast tRNAs (57). When comparing enzymatic activities from extracts prepared from a wild-type and an mtc12-0 (yol124c-0) mutant strain, a spot corresponding to m7G, which is catalyzed by Trm8/82p (1), was detected on both TLCs (Fig. 1B, panels 1 and 2). In contrast, a spot corresponding to m2G was formed with the wild-type extract on tRNAIle but not with the mtc12-0 mutant extract. This result suggested that Mtc12p is required for the formation of m2G10 in vitro, and it was designated Trm11p, following the current nomenclature for yeast tRNA MTases. A centromeric plasmid expressing wild-type Trm11p was able to fully restore the formation of m2G in a trm11-0 strain, thus demonstrating that Trm11p is necessary for the formation of m2G10 in vitro.

To detect and purify Trm11p, the TRM11 sequence was fused to a TAP tag (53), and the resulting TRM11-TAP gene was cloned on a centromeric plasmid and transformed into the trm11-0 strain. Trm11-TAPp is functional, since it is able to restore the formation of m2G10 in tRNAIleUAU (Fig. 1B, panel 3). From multiple sequence alignment and modeling of Trm11p (see below and see Fig. 7), we predicted that the two aspartate D215 and D291 are key residues involved in AdoMet binding and MTase catalytic activity, respectively. Residue D215 belongs to motif I of the AdoMet-binding subdomain, and it is equivalent to D49 of Trm7p, which catalyzes the formation of two 2′-O-methylriboses at positions 32 and 34 in yeast tRNA (51), and D52 of Spb1p, which catalyzes the formation of Gm2922 in yeast 25S rRNA (41). These aspartate residues were shown to be critical for the enzymatic activities of Trm7p and Spb1p (41, 51). Residue D291 of Trm11p belongs to motif IV, which has been found to be important for the catalytic activity of many nucleic acid MTases (11). Therefore, a point mutation was introduced into the TRM11-TAP gene to change either D215 or D291 into an alanine (Trm11-D215A-TAP or Trm11-D291A-TAP). MTase activity was nearly abolished in the two mutant strains (Fig. 1B, panels 4 and 5), thus demonstrating that these two aspartate residues are essential for the MTase activity of Trm11p. We confirmed by Western blot analysis that these two mutant proteins were expressed at a level similar to that of the wild-type Trm11-TAP protein and thus that the phenotype observed for the two mutants was not due to a change in the protein level (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 to 3). We conclude from these results that Trm11p exerts MTase catalytic activity, as predicted from the bioinformatics study (14).

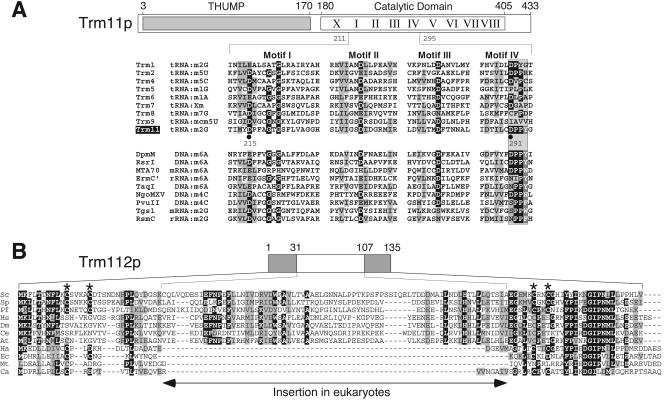

FIG. 7.

Sequence and structure analysis of Trm11p and Trm112p. (A) A schematic representation of Trm11p, with its two structural domains: the N-terminal THUMP (residues 1 to 180, shaded box) and the C-terminal catalytic RFM (with nine conserved motifs indicated by roman numerals). The sequence of Trm11p from S. cerevisiae is shown for a region corresponding to the most conserved motifs I to IV (residues 211 to 295), of which the AdoMet-binding motifs I to III are common to other tRNA MTases from yeast (top), but only the catalytic motif IV is evidently common with representative exocyclic amino MTases (bottom). The catalytic DPPY motif has been boxed. Identical and physicochemically similar residues are shown on a black and gray background, respectively. The two critical aspartate residues (D215 and D291) that have been mutated are shown with a black dot. (B) The sequence alignment of Trm112p from S. cerevisiae (Sc) and its orthologs from six eukaryotes (Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Pf, Plasmodium falciparum; Hs, Homo sapiens; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; At, Arabidopsis thaliana), one archaeon (Ha; Halobacterium sp. NRC-1), and three bacteria (Ec, E. coli; Mt, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Ca, C. aurantiacus).

As another means to demonstrate that the catalytic activity actually depends on Trm11p, the protein was immunoprecipitated and tested in vitro for m2G10 formation. Immunoprecipitation was performed with native S100 extracts prepared from strains expressing either wild-type untagged Trm11p as a control (Fig. 1B, panel 6) or a Trm11-TAP fusion protein (YBL4580) and IgGs coupled to Sepharose beads. m2G10 formation activity in tRNAIleUAU was mostly detected in the pellet containing the Trm11-TAP protein, thus demonstrating that Trm11p is required for this activity (Fig. 1B, panel 7).

The abundance of Trm11p in the cell was compared to that of Trm7p, another tRNA modifying enzyme, as well as to the abundant nucleolar protein Nop1p, used here as a control (7, 51). Trm11p is ∼20 times less abundant than Nop1p, and it is ∼10 times more abundant than Trm7p (Fig. 1C, lanes 4 to 6), as estimated from serial dilution experiments (data not shown). Trm11-TAP was then localized in the cell by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) decorates the nucleus and the mitochondria throughout the cytoplasm, due to their DNA content (Fig. 1D). Fluorescent IgGs revealed Trm11-TAPp throughout the cytoplasm, while it appeared to be mostly excluded from the nucleus.

m2G10 formation also requires Trm112p, which is associated with Trm11p.

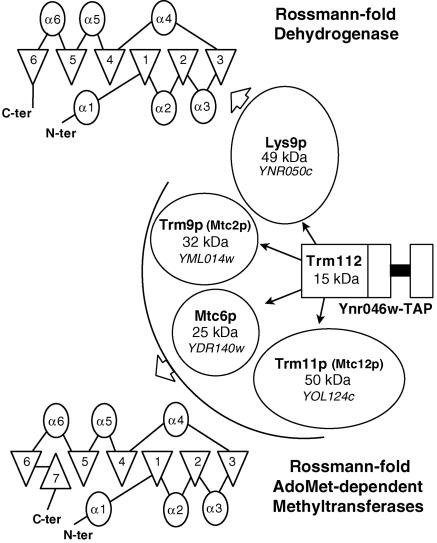

Formation of m1A58 and m7G46 requires heterodimeric enzymes: Trm6/61p and Trm8/82p, respectively (1, 2). Therefore, we investigated whether Trm11p is sufficient for m2G10 formation or requires other factors. Recombinant Trm11p expressed in Escherichia coli exhibited no m2G10 formation activity (data not shown), suggesting that an essential factor could be missing in E. coli. A global analysis of protein complexes in yeast had reported an interaction of Trm11p with the product of an uncharacterized ORF, YNR046w (which will be referred to as TRM112) (22). In that study, Trm112p was reported to interact with four proteins: Trm11p, Trm9p (Yml014w) (38), Mtc6p (Ydr140w), and Lys9p (Ynr050c) (52) (Fig. 2). It is striking that the four proteins interacting with Trm112p share sequence similarities: Trm11p, Trm9p, and Mtc6p possess an MTase domain, and Trm11p and Trm9p are proven tRNA MTases (this work and reference 38), while Mtc6p is an ortholog of the N(5)-glutamine protein MTase HemK, which is involved in the regulation of translation by modifying release factors (32, 46). The fourth protein, Lys9p, is related to Rossmann fold dehydrogenases, which resemble the RFM except for the lack of the C-terminal antiparallel β-strand (Fig. 2). To investigate whether any of these proteins were required to assist Trm11p in m2G10 formation, the corresponding ORFs were deleted. The four resulting yeast strains were viable, and lys9-0 and mtc6-0 strains did not exhibit any growth defect compared to the wild type. In contrast, the trm9-0 strain had a mild growth defect, with a generation time of ∼120 min, and growth of the trm112-0 strain was severely impaired, with a generation time of ∼360 min (Fig. 3A). Double-mutant strains were then constructed by combining any of the five deletions (data not shown). No synthetic effect was observed for any of these strains, and the double-mutant strain trm11-0 trm9-0 had a generation time of ∼120 min, similar to that of the trm9-0 strain (see Discussion).

FIG. 2.

Trm112p interacts with several proteins, including Trm11p. Large-scale analysis of protein complexes (22) has revealed an interaction of Trm112p with Lys9p, Trm9p, Mtc6p, and Trm11p, as schematically shown. Molecular masses of the five proteins are given in kilodaltons. A secondary structure representation is shown for the Rossmann fold and for the MTase domain. α-Helices are represented by ovals and β-strands are represented by triangles.

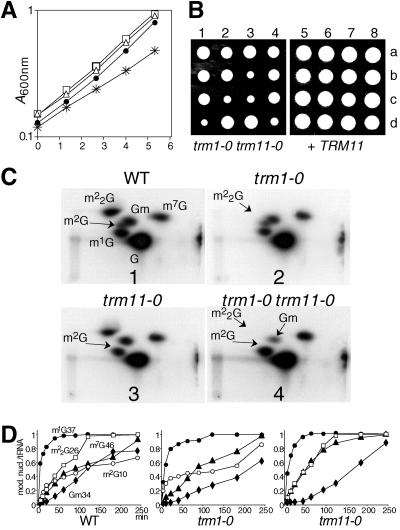

FIG. 3.

Trm11p and Trm112p are both required in vivo for the formation of m2G10. (A) Growth curves of wild-type and mutant strains in YPD at 30°C. Black circles, wild type (BMA64); open squares, trm11-0 (YBL4577); open diamonds, trm9-0 (YBL4557); open circles, trm112-0 (YBL4663). A600 nm was plotted on a semilogarithmic graph as a function of time in hours. (B) Autoradiogram of selected 2D-TLC of modified nucleotides after nuclease P1 digestion of in vivo-labeled [32P]tRNA. Hydrolysates of total tRNA were analyzed with the chromatographic system NI/RII (37). Panels: 1, wild type (WT); 2, trm11-0; 3, trm112-0; 4, mtc6-0; 5, trm9-0; 6, lys9-0. The spots of interest are shown on the wild-type panel. The arrows indicate the positions for m2G10.

The pattern of modified nucleotides was examined with bulk radiolabeled tRNA extracted from the trm11-0, trm112-0, mtc6-0, trm9-0, and lys9-0 strains. In vivo-labeled tRNA digested with nuclease P1 revealed a complex pattern of modified nucleotides, among which the nonmodified 5′ monophosphate nucleotides pA, pC, pG, and pU gave the most intense signals (Fig. 3B, panel 1). Radiolabeled spots corresponding to ribothymidine (pT), dihydrouridine (pD), and pseudouridine (pΨ), which are present in all naturally occurring yeast tRNAs, were also readily detected. Other modified nucleotides, which are present only in certain tRNAs, yield less-intense spots that can still be easily identified on the autoradiogram with the previously established maps, as long as they do not comigrate with other modified nucleotides (25).

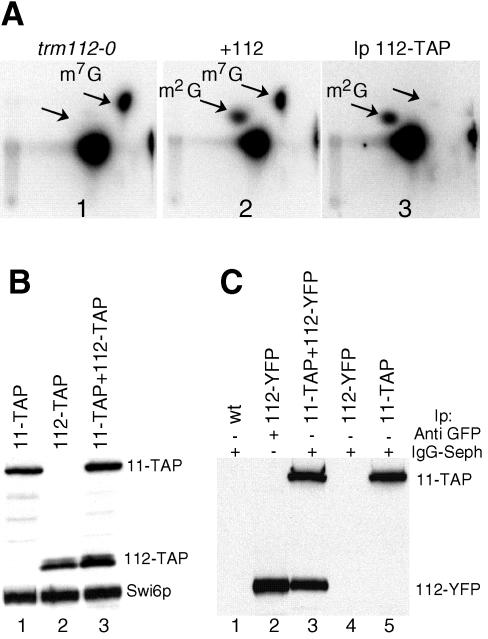

The spot on the TLC plate corresponding to m2G in the wild-type strain is clearly missing in tRNA extracted from the trm11-0 and trm112-0 strains (Fig. 3B, panels 2 and 3). In contrast, this spot was visible in tRNA extracted from the mtc6-0 (plate 4), trm9-0 (plate 5), and lys9-0 (plate 6) strains. To confirm the data obtained in vivo, cellular extracts were prepared from the trm112-0 strain and tested in vitro, using a synthetic intronless tRNAIleUAU transcribed in vitro in the presence of [α-32P]GTP as a substrate. This extract was unable to catalyze the formation of m2G10 in vitro, while m7G46 was correctly formed (Fig. 4A, panel 1). A plasmid carrying the wild-type TRM112 gene transformed into the trm112-0 strain was able to restore its wild-type growth (data not shown) and its ability to catalyze the formation of m2G10 (Fig. 4A, panel 2). These results demonstrate that Trm112p and Trm11p are both required for the formation of m2G10 in vivo as well as in vitro.

FIG. 4.

Trm112p is required for the formation of m2G10 in vitro and is associated with Trm11p. (A) [α-32P]GTP-labeled intronless tRNAIleUAU was incubated with S10 cell extracts prepared from various strains or with an immunoprecipitated fraction, and then modified nucleotides were analyzed as in Fig. 1. Panel 1, trm112-0 (YBL4663); panel 2, +112 (strain trm112-0 complemented with a TRM112 gene on a centromeric plasmid [YBL4665]); panel 3, Ip 112-TAP (Trm112-TAPp immunoprecipitated from an S100 extract prepared from strain YBL4634 and tested for m2G10 formation activity). (B) Comparison of the abundance of Trm112-TAPp and Trm11-TAPp. Western blot analysis was performed using IgGs coupled to peroxidase, and extracts were prepared from cells expressing protein A-tagged proteins. Lanes: 1, Trm11-TAPp(YBL4580); 2, Trm112-TAPp(YBL4634); 3, Trm11-TAPp/Trm112-TAPp(YBL4635). Similar amounts of proteins were loaded in each lane, as demonstrated by using anti-Swi6p antibodies. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation experiment. Cellular extracts prepared from strains expressing either Trm11-TAPp, Trm112-YFPp, or both were incubated with IgG-Sepharose beads, the pellets were washed under stringent conditions, and then proteins were eluted and tested by Western blot analysis, using an anti-GFP serum that detects both fusion proteins. Lane 1, wild-type strain; lanes 2 and 4, Ynr046w-YFP; lane 3, YBL4689; lane 5, YBL4580. In the results shown in lane 2, immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-GFP and protein A-Sepharose beads.

The Trm112 protein fused to the TAP tag was immunoprecipitated from an S100 cell extract, and its activity was tested in vitro as described above (Fig. 4A, panel 3). The result demonstrates that Trm112-TAPp is immunoprecipitated with the m2G10 formation activity but not m7G46. In addition, no activity was precipitated with an untagged strain, thus confirming the specificity of the immunoprecipitation. Lys9p and Mtc6p were also fused to the TAP tag, but no m2G10 formation activity could be precipitated with these proteins (data not shown). To evaluate the relative abundance of Trm11p and Trm112p, a strain expressing the two tagged proteins expressed from their natural promoters was tested by Western blot analysis. The two proteins were present in comparable amounts in the cell, an observation compatible with the hypothesis that they form a complex (Fig. 4B, lane 3).

The direct association of Trm11p and Trm112p was then tested by coimmunoprecipitation analysis. TRM112 fused to the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) gene drives the expression of Trm112-YFP that can be detected with antibodies raised against green fluorescent protein (GFP) (31). Cellular extracts were prepared from a strain expressing both Trm11-TAPp and Trm112-YFP, and then Trm11-TAPp was precipitated with IgGs coupled to Sepharose beads (Amersham). The result clearly shows that Trm112p is coprecipitated with Trm11p, thus confirming the physical association of the two proteins (Fig. 4C, lane 3). No Trm112-YFP was precipitated in the absence of Trm11-TAP (lane 4), and the signal truly depended on Trm112-YFP (lane 5). Interestingly, the two mutant proteins Trm11-D215Ap and Trm11-D291Ap were both able to precipitate Trm112p, thus indicating that the interaction between the two proteins did not depend on the MTase activity (data not shown). Trm112p also coprecipitated with Lys9-TAPp, Mtc6-TAPp, and Trm9-TAPp, thus confirming the data obtained previously (22).

We then tested whether Trm112p exerted its effect through the synthesis or maintenance of Trm11p. To this end, the abundance of Trm11-TAPp was compared in a wild-type and in a trm112-0 strain and found to be similar. Conversely, Trm112-TAPp was expressed at the same level in a wild-type or in a trm11-0 strain (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that Trm11p and Trm112p form a complex and that both subunits are required to achieve the catalytic formation of m2G10 in vivo and in vitro. We cannot yet conclude whether these two subunits are sufficient to catalyze this reaction, since their coexpression in E. coli failed to reconstitute the activity (data not shown), and it cannot be excluded that the active complex coprecipitated from the yeast includes some other components.

TRM11 interacts genetically with TRM1.

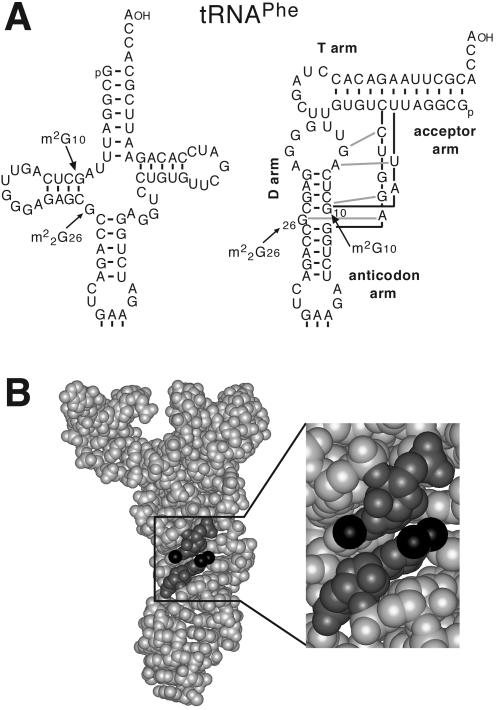

The trm11-0 strain growth rate was indistinguishable from that of a wild-type strain under laboratory conditions (Fig. 5A and B). Therefore, we tested the effect of combining the deletion of TRM11 with the deletion of certain tRNA-modifying activities or the partners of Trm112p. When trm11-0 was combined with either trm1-0, trm7-0, trm8-0, trm9-0, lys9-0, or mtc6-0, there was a genetic interaction only between TRM11 and TRM1. Trm1p catalyzes the formation of m22G26 in both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA (19, 33). While the trm1-0 and the trm11-0 single-mutant strains had no detectable growth defect under laboratory conditions (doubling time, ∼90 min), the double-mutant strain trm1-0 trm11-0 had a doubling time of ∼140 min at 30°C (Fig. 5A and B). This synthetic defect was abolished when the cells were complemented with a wild-type copy of one of the two genes (Fig. 5B, right, and data not shown). The double-mutant cells were ∼10% larger on the average than those of the wild type and they had a lengthened cell cycle G1 phase (data not shown). To test whether formation of m2G10 and m22G26 was dependent on each other, we examined these activities in each mutant strain using [α-32P]GTP-radiolabeled synthetic intronless yeast tRNAPheGAA as a substrate (see Fig. 6 for its sequence). Formation of m2G in vitro with an extract prepared from a trm1-0 strain was normal, as was the formation of m22G using a trm11-0 strain (Fig. 5C, panels 2 and 3). Kinetic analysis confirmed that the rate of formation of m2G was independent of the presence or the absence of Trm1p (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the formation of Gm34 in tRNAPhe (Fig. 5D), which depends on tRNA tertiary structures (F. Lecointe and H. Grosjean, unpublished data), was mildly reduced in either trm1-0 or trm11-0 single-mutant strain and significantly diminished in the trm1-0 trm11-0 double-mutant strain (Fig. 5C, panel 4; Fig. 5D; and data not shown), thus suggesting that the absence of these modifications may affect tRNAPhe tertiary structure (61). Due to tRNA folding and formation of the D-loop arm, m2G10 and m22G26 were brought near to each other (Fig. 6). Tertiary structure examination of yeast tRNAPhe revealed that the two modified nucleotides are stacked on each other, with the exocyclic amines N2 appearing on the same face of the tRNA and pointing in opposite directions (Fig. 6).

FIG. 5.

TRM11 and TRM112 interact genetically with TRM1. (A) Growth curves of various strains at 30°C in YPD. Filled circles, wild-type; open triangles, trm1-0; open squares, trm11-0; asterisks, trm1-0 trm11-0. (B) Spore analysis of a diploid strain heterozygous for the two loci trm1-0::URA3/TRM1 and trm11-0::kanMX4/TRM11 (YBL4611) or the same strain transformed with a plasmid containing the TRM11 wild-type gene and an LEU2 marker. Spores 1d, 2c, 3b, 3c, and 4d were trm1-0 trm11-0. Spores 5a, 5b, 6a, 7d, and 8b were also deleted for trm1-0 and trm11-0; however, they contained the TRM11 gene on an LEU2 plasmid (pBL640). Each colony was scored for Ura+, Leu+, or G418 resistance on appropriate panels. (C) 2D-TLC analysis of [α-32P]GTP-labeled intronless tRNAPhe incubated with S10 cell extracts as shown in Fig. 1. Panels: 1, extracts prepared from a wild-type strain (WT); 2, trm1-0; 3, trm11-0; 4, the double-mutant strain trm1-0 trm11-0. Arrows point to the spots corresponding to m2G10, m22G26, and Gm34. (D) Kinetic analysis of the formation of modified nucleotides in vitro, using S10 extracts prepared from wild-type (WT), trm1-0, and trm11-0 strains. For each time point, nucleotides were separated by 2D-TLC, and each spot was quantified by phosphorimaging.

FIG. 6.

(A) Cloverleaf and L-shape representations (35) of yeast tRNAPhe, depicting the relative positions of m2G10 and m22G26. (B) Three-dimensional structure of tRNAPhe (1eHz file, available at http://www.resb.org/pdb/) with the two methylguanosines stacked on each other and a close-up view indicating the direction of the two methyl groups.

Bioinformatic analysis of Trm11p and Trm112p.

Sequence analysis of Trm11p suggests that it comprises an RNA-binding THUMP (thiouridine synthases, RNA methyltransferases, and pseudouridine synthases) domain (3) in the N terminus and an MTase catalytic domain in the C terminus (Fig. 7A and see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The protein fold recognition analysis failed to reveal the similarity of the THUMP domain to any known three-dimensional protein structures. In contrast, we were able to generate confident sequence alignment between the C-terminal domain of Trm11p (residues 211 to 295) and known MTase structures. The tertiary model of the Trm11p structure was build using the “FRankenstein's monster” approach (39). Analysis of the structure of the model and the residues invariant in the Trm11p family suggested that D215 (in motif I) and D291 (in motif IV) were the key residues involved in AdoMet binding and MTase catalytic activity. Interestingly, we found that the putative active site of Trm11p (motif IV) resembled the active site of a number of MTases involved in generation of m2G, m6A, and m4C in DNA or RNA (12) rather than the active site of any other tRNA MTase (Fig. 7A). Members of the Trm11p family exhibited the DPPY tetrapeptide in motif IV (Fig. 7), a variant of a [D-N-S]-P-P-[Y-F-W-H] motif found in the majority of MTases that modify exocyclic amino groups of bases in DNA and RNA, including rRNA:m2G MTases: RsmC/RsmD specific for bacterial 16S rRNA (12) and Tgs1p specific for eukaryotic mRNA:cap-m7G (45).

Sequence database searches revealed that the putative orthologous lineage of proteins closely related to Trm11p (PSI-BLAST E values of <10−30 in three iterations) and exhibiting the DPPY motif in the catalytic domain was conserved in eukaryotes and archaea but was not found in bacteria, suggesting that it may encode a function specific to only two domains of life (5). Other THUMP-MTase fusion proteins related to Trm11p could be identified in all three phyla (3), but these similarities were more remote (PSI-BLAST E values of <10−15 in the third iteration) and exhibited different forms of the catalytic motif (for instance, NPPY), suggesting paralogous rather than orthologous relationships and different substrate specificity.

Database searches using the Trm112p sequence as a query revealed a large family of uncharacterized proteins from eukaryotes (typical length, about 130 residues), archaea (length, 55 to 141 residues), and bacteria (typical length, about 60 residues; representative member, putative protein YcaR from E. coli). Sequence analysis (Fig. 7B) revealed that Trm112p comprises two domains, one inserted into another: residues 1 to 31 and 107 to 135 are conserved in all members, while residues 32 to 106 correspond to an insertion specific for eukaryotic members only. Structure prediction and protein fold recognition analyses carried out via the GeneSilico metaserver gateway (40) failed to identify any homologs for the “inner” domain. However, the “outer” domain of Trm112p, as well as the entire sequence of the homologous protein YcaR, exhibited similarity to a number of different nucleic acid-binding proteins containing Zn finger motifs with a four-stranded β-sheet (data not shown). Interestingly, in some bacterial members of the family (e.g., hypothetical proteins Chlo2137 and Chlo0356 from Chloroflexus aurantiacus and GSU0900 from Geobacter sulfurreducens), the newly predicted Zn finger domain was fused to an RFM domain, which nonetheless did not contain the DPPY active site signature and apparently belongs to a family different from the RFM domain in Trm11p.

A fusion of a Zn finger domain remotely related to the “outer” domain of Trm112p with a C-terminal MTase domain was found in another family of RNA modification enzymes, RlmAI/RlmAII (13, 16), which catalyze the formation of m1G in 23S rRNA (27). In the crystal structure of RlmAI, the Zn-binding domain, suggested to be responsible for specific recognition and binding of the rRNA substrate, binds to the edge of the catalytic domain, forming an extension of the central β-sheet (16). It is tempting to speculate that Trm11p and Trm112p interact in a manner similar to that of the two domains of RlmAI (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). It is noteworthy that the putative Zn-binding residues are missing from many homologs of Trm112p (for instance, from the human ortholog of Trm112p), which indicates that the metal-binding site probably has a purely structural role as a stabilization center, rather than as a part of the MTase active site. Interestingly, a Zn finger domain is also present in some members of the Trm1p family, where it probably fulfills a structural role (15); while in the yeast tRNA pseudouridine synthase Pus1p, this structural role has been demonstrated (4). It remains to be determined experimentally whether the cluster of four Cys residues in Trm112p from yeast is essential for the activity of the Trm11p/Trm112p complex and how the two proteins interact with each other and with the tRNA substrate.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report the identification of the MTase activity responsible for the formation of m2G10 in yeast cytoplasmic tRNA. At least two subunits are required for the formation of this modified nucleotide. Trm11p is likely the catalytic subunit, since it possesses the structural characteristics of a bona fide AdoMet-dependent MTase, it is required both in vivo and in vitro for the formation of m2G10, two point mutations predicted to affect the AdoMet binding, and the catalytic domains nearly abolished its activity. Trm112p is also required for the formation of m2G10, since a trm112-0 strain is unable to catalyze the formation of m2G10 in vivo or in vitro, similar to a trm11-0 strain. Moreover, m2G10 formation activity can be immunoprecipitated with Trm112p, and this protein interacts in vivo with the catalytic subunit Trm11p. However, the precise function of Trm112p is not yet known. Deletion of TRM112 leads to a severe growth defect, while deletion of TRM11 has no detectable phenotype, thus suggesting that Trm112p has an additional function(s) in the cell. The other proteins that interact with Trm112p (Trm9p, Mtc6p, and Lys9p) do not appear to be required for the formation of m2G10. However, it is quite striking that among the four known partners of Trm112p there are two tRNA MTases (Trm9p and Trm11p), one putative protein MTase (Mtc6p), and a protein with a Rossmann fold domain (Lys9p). Our data do not plead for the existence in yeast cells of a stable pentameric complex containing all these proteins. Indeed, while m2G10 formation activity is clearly associated with Trm11p and Trm112p, immunoprecipitation of either Lys9p or Mtc6p failed to precipitate this activity, although they coprecipitated Trm112p (data not shown). This experiment suggests that Trm112p interacts independently with its various partners. Since Trm112p is a small protein (15 kDa) with a predicted Zn finger domain, it could interact with its different partners through the same domain in an exclusive manner, rather than being a docking platform for the simultaneous attachment of all these proteins. Orthologs from bacteria and archaea do not possess the “inner domain” that could specify a eukaryotic-only function (Fig. 7B). In bacteria, there is no m2G10 in tRNA and thus there is no Trm11 activity; while in archaea, the ortholog of Trm11p, PabTrm-G10, can catalyze the formation of m2G10/m22G10 in the absence of additional proteins (5). It is thus conceivable that the inner domain of Trm112p is responsible for interacting with Trm11p in S. cerevisiae and possibly in all eukaryotes, a possibility that will be tested in future work. Although PabTrm-G10 and Trm11p belong to the same cluster of orthologous groups (COG1041), the archaeal enzyme behaves differently. Not only does it catalyze the formation of m2G10, like Trm11/Trm112p, but it can also direct the formation of m22G10, depending on the type of the tRNA substrate (5), an activity not shared by the yeast enzyme, since no yeast tRNA sequenced so far was shown to contain m22G10 (57).

Among the various tRNA MTases identified so far in S. cerevisiae, Trm6/Trm61p (previously known as Gcd10/Gcd14p) and Trm8/Trm82p have also been shown to be formed by the heteromeric association of two subunits (1, 2). For Trm6 activity (catalyzing the formation of m1A58), one of the two subunits (Trm61/Gcd14p) is required for tRNA binding, while the other (Trm6/Gcd10p) binds to AdoMet and catalyzes the methylation reaction. Comparison of their sequences has revealed that Trm6/Gcd10 and Trm61/Gcd14p are evolutionarily related and probably arose by gene duplication, followed by speciation of each subunit. For Trm8/82p (catalyzing the formation of m7G46), the two subunits are not evolutionarily related and only Trm8p contains the catalytic RFM domain (1).

To fully understand the role of Trm112p in the cell, it will be necessary to decipher its relationship with its other partners (Trm9p, Mtc6p, and Lys9p). It is worthwhile to notice that the double-mutant strain trm11-0 trm9-0 has the same growth defect as the single-mutant trm9-0 (∼120 min). Therefore, the strong growth defect of the trm112-0 strain cannot simply be due to a synthetic effect between trm11-0 and trm9-0. No synthetic interaction was observed between any of the genes encoding the factors associated with Trm112p (double or triple mutants). Interestingly, Lys9p, a Rossmann fold protein that may utilize NAD/NADP as a cofactor could play a negative regulatory role on several tRNA modification activities through its interaction with Trm112p (29).

tRNALysCUU was reported to contain an m2G at position 9 (56), while all other tRNAs modified at that position possessed an m1G (57). However, we did not detect the formation of m2G in vitro using a synthetic tRNALysCUU transcript while both m1G9 and m22G26 were formed. In addition, no m2G was detected in vivo in bulk tRNA prepared from a trm11-0 strain. Due to the sensitivity of the method, we cannot exclude that there are very small amounts of m2G still made in these cells that remain undetected, although this seems unlikely. Instead, it suggests that Trm11p is the sole activity catalyzing the formation of m2G in yeast tRNA and that it is detected exclusively at position 10. The lack of m2G in the absence of Trm11p also indicates that there is no detectable accumulation of an intermediate species of m2G26 in yeast and that m22G26 is the normal end product of Trm1p. Earlier maturation studies using yeast tRNA injected into Xenopus oocytes had concluded that formation of m2G and m22G can occur before the removal of the intron (48). Also, formation of m22G26 in yeast was shown to occur in vitro in two steps with an intermediate of m2G26 (18). However, we did not detect this intermediate in naturally occurring tRNA prepared from yeast cells, thus suggesting that under physiological conditions m22G26 must be formed rapidly with no detectable pool of m2G26. Our data also suggest that tRNAValCAC most likely contains an m22G at position 26, not an m2G.

Certain tRNA modifications are extremely well conserved throughout the evolution, suggesting that they play a major role either in tRNA metabolism or in translation. Therefore, the absence of these highly conserved modifications should be detrimental to the cell. However, in several cases, deletion of the genes coding for tRNA modification enzymes led to no detectable phenotype. Although a large proportion of yeast tRNA have an m2G10 (16 out of 37 sequences) or an m22G26 (∼19 out of 37) (Table 3), deletion of either TRM1 or TRM11 led to no detectable phenotype. Interestingly, we report here a genetic interaction between TRM1 and TRM11. The double-mutant strain exhibits a slow-growth phenotype at 30°C that could be a consequence of the absence of the modifications at both positions 10 and 26 rather than the absence of another function associated with these proteins. Indeed, the expression of either mutant protein Trm11-D215A or Trm11-D291A was unable to rescue the growth defect of the double-mutant strain trm1-0 trm11-0. This result suggests that the presence of both modifications might be required, at least for certain tRNA, for the cell to grow at a wild-type rate. Formation of Gm34, which is catalyzed by Trm7p, strongly depends on correct tRNA folding (Lecointe and Grosjean, unpublished). Our observation that Gm34 is formed at a significantly lower rate in the absence of m2G10 and m22G26 suggests that these two latter modifications could be important for certain tRNAs to be properly folded, as suggested for dimethylguanosines by previous studies (58).

In conclusion, we demonstrate here that methylation of the exocyclic amine of guanine 10 in S. cerevisiae strictly depends on two evolutionary unrelated proteins (Trm11p/Trm112p) that form a complex located in the cytoplasm. Moreover, methylations of guanosines at position 10 (catalyzed by Trm11p/Trm112p) and at position 26 (catalyzed by Trm1p) are functionally related.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Bertrand, R. Bordonné, and M. Sitbon for stimulating discussions. We are grateful to E. Schwob and L. Dirick for their help with yeast analysis and for sharing supplies and equipment.

This work was supported by a grant from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (no. 5914), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. J.M.B. was supported by a EMBO/HHMI Young Investigator award and by a fellowship from the Foundation for Polish Science. H.G. was supported by a grant from the CNRS (Programme Interdépartemental de Géomicrobiologie des Environnements Extrêmes, Geomex 2002-2003). S.K.P. was a fellow from the Ministère des Affaires Étrangères and then from the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexandrov, A., M. R. Martzen, and E. M. Phizicky. 2002. Two proteins that form a complex are required for 7-methylguanosine modification of yeast tRNA. RNA 8:1253-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, J., L. Phan, R. Cuesta, B. A. Carlson, M. Pak, K. Asano, G. R. Björk, M. Tamame, and A. G. Hinnebusch. 1998. The essential Gcd10p-Gcd14p nuclear complex is required for 1-methyladenosine modification and maturation of initiator methionyl-tRNA. Genes Dev. 12:3650-3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 2001. THUMP: a predicted RNA-binding domain shared by 4-thiouridine, pseudouridine synthases and RNA methylases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:215-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arluison, V., C. Hountondji, B. Robert, and H. Grosjean. 1998. Transfer RNA-pseudouridine synthetase Pus1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains one atom of zinc essential for its native conformation and tRNA recognition. Biochemistry 37:7268-7276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armengaud, J., J. Urbonavicius, B. Fernandez, G. Chaussinand, J. M. Bujnicki, and H. Grosjean. 2004. N2-Methylation of guanosine at position 10 in tRNA is catalyzed by a THUMP domain-containing, S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase, conserved in Archaea and Eukaryota. J. Biol. Chem. 279:37142-37152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baudin, A., O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, A. Denouel, F. Lacroute, and C. Cullin. 1993. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:3329-3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergès, T., E. Petfalski, D. Tollervey, and E. C. Hurt. 1994. Synthetic lethality with fibrillarin identifies NOP77p, a nucleolar protein required for pre-rRNA processing and modification. EMBO J. 13:3136-3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Björk, G. R., K. Jacobsson, K. Nilsson, M. J. Johansson, A. S. Byström, and O. P. Persson. 2001. A primordial tRNA modification required for the evolution of life? EMBO J. 20:231-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonneaud, N., O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, G. Y. Li, M. Labouesse, L. Minvielle-Sebastia, and F. Lacroute. 1991. A family of low and high copy replicative, integrative and single-stranded S. cerevisiae/E. coli shuttle vectors. Yeast 7:609-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borek, E. 1971. Transfer RNA and transfer RNA modification in differentiation and neoplasia. Introduction. Cancer Res. 31:596-597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bujnicki, J. M. 1999. Comparison of protein structures reveals monophyletic origin of the AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase family and mechanistic convergence rather than recent differentiation of N4-cytosine and N6-adenine DNA methylation. In Silico Biol. 1:175-182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bujnicki, J. M. 2000. Phylogenomic analysis of 16S rRNA:(guanine-N2) methyltransferases suggests new family members and reveals highly conserved motifs and a domain structure similar to other nucleic acid amino-methyltransferases. FASEB J. 14:2365-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bujnicki, J. M., R. M. Blumenthal, and L. Rychlewski. 2002. Sequence analysis and structure prediction of 23S rRNA:m1G methyltransferases reveals a conserved core augmented with a putative Zn-binding domain in the N-terminus and family-specific elaborations in the C-terminus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:93-99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bujnicki, J. M., L. Droogmans, H. Grosjean, S. K. Purushothaman, and B. Lapeyre. 2004. Bioinformatics-guided identification and experimental characterization of novel RNA methyltransferases, p. 139-168. In J. M. Bujnicki (ed.), Practical bioinformatics, vol. 15. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bujnicki, J. M., R. A. Leach, J. Debski, and L. Rychlewski. 2002. Bioinformatic analyses of the tRNA: (guanine 26, N2,N2)-dimethyltransferase (Trm1) family. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:405-415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das, K., T. Acton, Y. Chiang, L. Shih, E. Arnold, and G. T. Montelione. 2004. Crystal structure of RlmAI: implications for understanding the 23S rRNA G745/G748-methylation at the macrolide antibiotic-binding site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4041-4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delk, A. S., J. M. Romeo, D. P. Nagle, Jr., and J. C. Rabinowitz. 1976. Biosynthesis of ribothymidine in the transfer RNA of Streptococcus faecalis and Bacillus subtilis. A methylation of RNA involving 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate. J. Biol. Chem. 251:7649-7656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edqvist, J., K. Blomqvist, and K. B. Straby. 1994. Structural elements in yeast tRNAs required for homologous modification of guanosine-26 into dimethylguanosine-26 by the yeast Trm1 tRNA-modifying enzyme. Biochemistry 33:9546-9551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis, S. R., M. J. Morales, J. M. Li, A. K. Hopper, and N. C. Martin. 1986. Isolation and characterization of the TRM1 locus, a gene essential for the N2,N2-dimethylguanosine modification of both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic tRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9703-9709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauman, E. B., R. M. Blumenthal, and X. Cheng. 1999. Structure and function of AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases, p. 1-38. In X. Cheng and R. M. Blumenthal (ed.), S-Adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases: structures and functions. World Scientific, Inc., Singapore, Singapore.

- 21.Gautier, T., T. Bergès, D. Tollervey, and E. Hurt. 1997. Nucleolar KKE/D repeat proteins Nop56p and Nop58p interact with Nop1p and are required for ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:7088-7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavin, A. C., M. Bosche, R. Krause, P. Grandi, M. Marzioch, A. Bauer, J. Schultz, J. M. Rick, A. M. Michon, C. M. Cruciat, M. Remor, C. Hofert, M. Schelder, M. Brajenovic, H. Ruffner, A. Merino, K. Klein, M. Hudak, D. Dickson, T. Rudi, V. Gnau, A. Bauch, S. Bastuck, B. Huhse, C. Leutwein, M. A. Heurtier, R. R. Copley, A. Edelmann, E. Querfurth, V. Rybin, G. Drewes, M. Raida, T. Bouwmeester, P. Bork, B. Séraphin, B. Kuster, G. Neubauer, and G. Superti-Furga. 2002. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gietz, D., A. St. Jean, R. A. Woods, and R. H. Schiestl. 1992. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorbulev, V. G., V. D. Axel'rod, and A. A. Bayev. 1977. Primary structure of baker's yeast tRNAVal2b. Nucleic Acids Res. 4:3239-3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grosjean, H., G. Keith, and L. Droogmans. 2004. Detection and quantification of modified nucleotides in RNA using thin-layer chromatography. Methods Mol. Biol. 265:357-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grosjean, H., M. Sprinzl, and S. Steinberg. 1995. Posttranscriptionally modified nucleosides in transfer RNA: their locations and frequencies. Biochimie 77:139-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gustafsson, C., and B. C. Persson. 1998. Identification of the rrmA gene encoding the 23S rRNA m1G745 methyltransferase in Escherichia coli and characterization of an m1G745-deficient mutant. J. Bacteriol. 180:359-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guthrie, C., and G. R. Fink (ed.). 1991. Methods in enzymology, vol. 194. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif. [PubMed]

- 29.Halpern, R. M., S. Q. Chaney, B. C. Halpern, and R. A. Smith. 1971. Nicotinamide: a natural inhibitor of tRNA methylase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 42:602-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hani, J., and H. Feldmann. 1998. tRNA genes and retroelements in the yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:689-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hazbun, T. R., L. Malmstrom, S. Anderson, B. J. Graczyk, B. Fox, M. Riffle, B. A. Sundin, J. D. Aranda, W. H. McDonald, C. H. Chiu, B. E. Snydsman, P. Bradley, E. G. Muller, S. Fields, D. Baker, J. R. Yates III, and T. N. Davis. 2003. Assigning function to yeast proteins by integration of technologies. Mol. Cell 12:1353-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heurgue-Hamard, V., S. Champ, A. Engstrom, M. Ehrenberg, and R. H. Buckingham. 2002. The hemK gene in Escherichia coli encodes the N(5)-glutamine methyltransferase that modifies peptide release factors. EMBO J. 21:769-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hopper, A. K., A. H. Furukawa, H. D. Pham, and N. C. Martin. 1982. Defects in modification of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial transfer RNAs are caused by single nuclear mutations. Cell 28:543-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopper, A. K., and E. M. Phizicky. 2003. tRNA transfers to the limelight. Genes Dev. 17:162-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishitani, R., O. Nureki, N. Nameki, N. Okada, S. Nishimura, and S. Yokoyama. 2003. Alternative tertiary structure of tRNA for recognition by a posttranscriptional modification enzyme. Cell 113:383-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackman, J. E., R. K. Montange, H. S. Malik, and E. M. Phizicky. 2003. Identification of the yeast gene encoding the tRNA m1G methyltransferase responsible for modification at position 9. RNA 9:574-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang, H. Q., Y. Motorin, Y. X. Jin, and H. Grosjean. 1997. Pleiotropic effects of intron removal on base modification pattern of yeast tRNAPhe: an in vitro study. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2694-2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalhor, H. R., and S. Clarke. 2003. Novel methyltransferase for modified uridine residues at the wobble position of tRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:9283-9292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosinski, J., I. A. Cymerman, M. Feder, M. A. Kurowski, J. M. Sasin, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2003. A “FRankenstein's monster” approach to comparative modeling: merging the finest fragments of fold-recognition models and iterative model refinement aided by 3D structure evaluation. Proteins 53(Suppl. 6):369-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurowski, M. A., and J. M. Bujnicki. 2003. GeneSilico protein structure prediction meta-server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3305-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lapeyre, B., and S. K. Purushothaman. 2004. Spb1p-directed formation of Gm2922 in the ribosome catalytic center occurs at a late processing stage. Mol. Cell 16:663-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Limbach, P. A., P. F. Crain, and J. A. McCloskey. 1994. Summary: the modified nucleosides of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:2183-2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marck, C., and H. Grosjean. 2002. tRNomics: analysis of tRNA genes from 50 genomes of Eukarya, Archaea, and Bacteria reveals anticodon-sparing strategies and domain-specific features. RNA 8:1189-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Motorin, Y., and H. Grosjean. 1999. Multisite-specific tRNA:m5C-methyltransferase (Trm4) in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the gene and substrate specificity of the enzyme. RNA 5:1105-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mouaikel, J., J. M. Bujnicki, J. Tazi, and R. Bordonne. 2003. Sequence-structure-function relationships of Tgs1, the yeast snRNA/snoRNA cap hypermethyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:4899-4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakahigashi, K., N. Kubo, S. Narita, T. Shimaoka, S. Goto, T. Oshima, H. Mori, M. Maeda, C. Wada, and H. Inokuchi. 2002. HemK, a class of protein methyl transferase with similarity to DNA methyl transferases, methylates polypeptide chain release factors, and hemK knockout induces defects in translational termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1473-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasmyth, K., and L. Dirick. 1991. The role of SWI4 and SWI6 in the activity of G1 cyclins in yeast. Cell 66:995-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishikura, K., and E. M. De Robertis. 1981. RNA processing in microinjected Xenopus oocytes. Sequential addition of base modifications in the spliced transfer RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 145:405-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogden, R. C., M. C. Lee, and G. Knapp. 1984. Transfer RNA splicing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: defining the substrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:9367-9382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pintard, L., D. Kressler, and B. Lapeyre. 2000. Spb1p is a yeast nucleolar protein associated with Nop1p and Nop58p that is able to bind S-adenosyl-l-methionine in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1370-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pintard, L., F. Lecointe, J. M. Bujnicki, C. Bonnerot, H. Grosjean, and B. Lapeyre. 2002. Trm7p catalyses the formation of two 2′-O-methylriboses in yeast tRNA anticodon loop. EMBO J. 21:1811-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramos, F., E. Dubois, and A. Pierard. 1988. Control of enzyme synthesis in the lysine biosynthetic pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Evidence for a regulatory role of gene LYS14. Eur. J. Biochem. 171:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rigaut, G., A. Shevchenko, B. Rutz, M. Wilm, M. Mann, and B. Séraphin. 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:1030-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schubert, H. L., R. M. Blumenthal, and X. Cheng. 2003. Many paths to methyltransfer: a chronicle of convergence. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:329-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith, C. J., H. S. Teh, A. N. Ley, and P. D'Obrenan. 1973. The nucleotide sequences and coding properties of the major and minor lysine transfer ribonucleic acids from the haploid yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C. J. Biol. Chem. 248:4475-4485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sprinzl, M., C. Horn, M. Brown, A. Ioudovitch, and S. Steinberg. 1998. Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:148-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steinberg, S., and R. Cedergren. 1995. A correlation between N2-dimethylguanosine presence and alternate tRNA conformers. RNA 1:886-891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z., B. Senger, G. Keith, F. Fasiolo, and H. Grosjean. 1994. Intron-dependent formation of pseudouridines in the anticodon of Saccharomyces cerevisiae minor tRNAIle. EMBO J. 13:4636-4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Warner, J. R. 1991. Labeling of RNA and phosphoproteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 194:423-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zagryadskaya, E. I., N. Kotlova, and S. V. Steinberg. 2004. Key elements in maintenance of the tRNA L-shape. J. Mol. Biol. 340:435-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.