Abstract

Objective

This clinical study aimed to evaluate the practical value of integrating an AI diagnostic model into clinical practice for caries detection using intraoral images.

Methods

In this prospective study, 4,361 teeth from 191 consecutive patients visiting an endodontics clinic were examined using an intraoral camera. The AI model, combining MobileNet-v3 and U-net architectures, was used for caries detection. The diagnostic performance of the AI model was assessed using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy, with the clinical diagnosis by endodontic specialists as the reference standard.

Results

The overall accuracy of the AI-assisted caries detection was 93.40%. The sensitivity and specificity were 81.31% (95% CI 78.22%-84.06%) and 95.65% (95% CI 94.94%-96.26%), respectively. The NPV and PPV were 96.49% (95% CI 95.84%-97.04%) and 77.68% (95% CI 74.49%-80.58%), respectively. The diagnostic accuracy varied depending on tooth position and caries type, with the highest accuracy in anterior teeth (96.04%) and the lowest sensitivity for interproximal caries in anterior teeth and buccal caries in premolars (approximately 10%).

Conclusion

The AI-assisted caries detection tool demonstrated potential for clinical application, with high overall accuracy and specificity. However, the sensitivity varied considerably depending on tooth position and caries type, suggesting the need for further improvement. Integration of multimodal data and development of more advanced AI models may enhance the performance of AI-assisted caries detection in clinical practice.

Keywords: Dental caries, Artificial intelligence, Intraoral camera, Diagnostic test

Introduction

Dental caries is a significant global oral health issue that affects a substantial portion of the population. Epidemiological surveys have revealed that the prevalence of dental caries exceeds 50% among Chinese residents [1]. The high morbidity rate poses a considerable burden on oral health worldwide [2].

Early detection of dental caries, in conjunction with improved oral hygiene practices and preventive interventions, can effectively halt the progression of lesions and reduce both treatment time and costs [3]. However, the diagnosis of dental caries typically entails a combination of visual inspection and tactile probing by specialized dental professionals. In complex cases, such as subgingival caries and early interproximal caries where visual and probe detection is insufficient, X-rays may be necessary to provide additional evidence. Moreover, due to the inherent subjectivity involved in the examination process, it is often challenging to completely detect and document all caries present in a patient’s oral cavity.

The intraoral digital camera is a compact device specifically designed for capturing images within the oral cavity. It shares a similar size to the widely used clinical mouth mirror but offers the distinct advantage of providing high-definition internal oral images. This enables dental professionals to obtain clear and precise visualizations of dental caries. Previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility and potential of digital photography in supporting the diagnosis of dental caries [4].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to machines capable of performing human-like tasks, encompassing machine learning techniques that identify patterns in data to make predictions. In dentistry, AI applications aim to enhance diagnostics, treatment planning, and patient care through image analysis, prediction modeling, and data management [5]. Multiple experiments have validated that the application of various AI models to existing case photos yields a higher level of agreement compared to expert diagnosis [6].

However, it is important to note that most existing researches in this field were based on pre-existing cases, with separate training and testing sets [6, 7]. This research methodology may be subject to certain limitations. The existing dataset might not encompass all possible clinical conditions and variations, thereby rendering the model’s performance on the test set inconclusive in real clinical scenarios. Moreover, the AI model could potentially encounter overfitting issues within the confines of the existing dataset, subsequently leading to performance degradation when exposed to novel cases with greater degree of variation and noise. Consequently, testing with random data from real clinical settings better simulates practical scenarios, allowing for a thorough evaluation of the model’s performance and robustness [8].

The purpose of this clinical study was to evaluate the accuracy of AI-assisted intraoral photographic examination. An established dental caries diagnostic model was utilized to diagnose continuous outpatients, its diagnostic performance in routine clinical work was assessed.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The present clinical study obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University (2023-KY-050-01). The project was registered and approved in Medical Research Registration System (medicalresearch.org.cn) of National Health Security Information Platform (MR-44-23-015681).

We prospectively enrolled consecutive patients visiting the endodontics clinics (J. Z. and F. Z.) at Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, from April to June 2023. Patients under 18 years of age, with mouth opening ≤ 3.5 cm, or unable to complete additional examinations (e.g., X-ray) for diagnosis purpose were excluded. The written informed consent was obtained from each volunteer prior to participation.

A total of 4361 teeth in 191 participants were recorded. Among these participants, 126 (71%) were women and 18 (29%) were men. The average age was 46 years (range 23–86 years). Of the 4361 teeth, 1517 were anterior teeth, 1518 were premolars, and 1326 were molars.

AI-assisted caries detection

Caries detection was achieved with a commercially available device (Aiyakankan, Aicreate, Zhuhai, China). Briefly, the architecture employs MobileNet-v3 as the backbone network for feature extraction and combines it with a 5-layer U-net for semantic segmentation of teeth. The entire model-building process used a dataset consisting of over 150,000 professionally visually annotated images. Of these, 15% of the images were set aside for testing. Image augmentation techniques are applied to enhance network robustness, including random adjustments in translation, cropping, rotation, brightness, and chromaticity. Images are resized to 512 × 512 and normalized before training using the PyTorch framework. MobileNet-v3 is chosen for its compact size, low computational requirements, and compatibility with mobile devices. Depthwise separable convolutions, residual structures from ResNet, and attention mechanisms are incorporated for accurate predictions. Batch normalization and dropout ensure training stability. The learning rate follows a dynamic decay algorithm with a factor of 0.99. MobileNet-v3 provides 5 feature outputs that are combined with U-net using a 5-layer upsampling and concatenation approach for pixel-level classification. The training process includes multiple iterations, each building upon the previous checkpoint. Each iteration involves 100 epochs, starting with a batch size of 8 and reducing it to 2. The loss function is cross-entropy, and optimization is performed using the Adam optimizer.

Intraoral images

Image acquisition was performed using an A9X intraoral camera (Aicreate), maintaining a distance of 20–50 mm from the dental surfaces. Images were captured at a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels and stored in JPEG format. Three distinct views—incisor/occlusal, vestibular/buccal, and palatal/lingual—were obtained for each tooth. Images exhibiting inadequate quality, such as those out of focus, fogged, or incomplete, were excluded and retaken. A tooth was classified as negative only if the AI detected no evidence of carious lesions across all three views.

The intraoral camera was operated through a provided computer system, which was included as part of the A9X package from the manufacturer Aicreate. The system specifications included a monitor resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels, a 60 Hz refresh rate, an Intel i7-3537U CPU, 8GB RAM, a 256GB SSD, and the Windows 10 operating system.

One of the authors (J. Z.) conducted all image acquisitions and quality assessment. After photographing, J. Z. and F. Z. conducted diagnostic confirmation and subsequent treatment in accordance with clinical routine. The observers did not modify the images and were unaware of the AI’s assessments until the completion of all experiments. The AI’s findings were strictly employed for research purposes and did not factor into any clinical decisions.

Clinical detection of caries

For each patient enrolled in the study, carious lesions were evaluated according to the WHO standard (Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods, 5th edition) [9] by J. Z. and F. Z. (each with 5 years of clinical practice) independently. In cases of differing opinions, a more experienced doctor (X. S., with over 20 years of clinical practice) makes the final decision, providing rationale until the three doctors reach a consensus diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.3 (GraphPad Software). The values of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN) were determined by comparing them to the clinical diagnosis, which served as the reference standard. Sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for different types of caries. Accuracy (ACC) was defined as ACC = (TN + TP) / (TN + TP + FN + FP). F1 Score were calculated as F1 = 2TP / (2TP + FP + FN).

Results

All the recorded teeth were diagnosed using the AI-assisted device, with the clinicians’ diagnoses serving as a reference. The overall accuracy (ACC) for the AI-assisted caries detection was 93.40%; the F1 score was 0.71; the sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP) were 81.31% (95% CI: 78.22-84.06%) and 95.65% (95% CI: 94.94-96.26%), respectively; the negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) were 96.49% (95% CI: 95.84-97.04%) and 77.68% (95% CI: 74.49-80.58%), respectively.

The AI-assisted device exhibited high specificity, indicating a strong ability to correctly identify non-caries cases. However, the specificity for occlusal surfaces in premolars and molars was slightly lower, at 87.54% and 81.56%, respectively. The sensitivity was considerably lower for most surfaces, except for occlusal surfaces, where it identified 94.12% and 94.44% of actual caries in premolars and molars. This suggested that while the system was excellent at ruling out non-caries, it struggled to identify all cases of caries.

The negative predictive values were high across all surfaces, which suggested that a negative result from this device could be highly trusted. This was valuable in clinical settings to reduce unnecessary treatments. However, the varying positive predictive values, particularly the lower values for proximal surfaces, indicated that positive detections should be carefully reviewed by clinicians for confirmation.

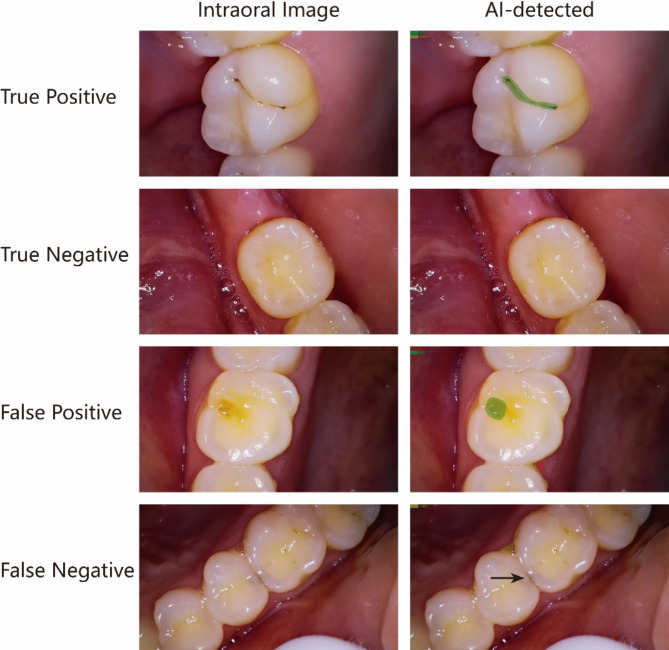

The values per site and type of caries were summarized in Table 1. Representative diagnostic example images were shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence-assisted caries detection

| True positive | True negative | False positive | False negative | Diagnostic performance | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ACC | F1 | SE (95% CI) | SP (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | |||||

| Anterior teeth | ||||||||||||||||||

| Incisal | 5 | 50.00 | 300 | 99.34 | 2 | 0.66 | 5 | 50.00 | 97.76 | 0.59 | 50.00 | (23.66–76.34) | 99.34 | (97.62–99.88) | 98.36 | (96.22–99.30) | 71.43 | (35.89–94.92) |

| Proximal | 2 | 11.11 | 192 | 97.96 | 4 | 2.04 | 16 | 88.89 | 90.65 | 0.17 | 11.11 | (1.97–32.80) | 97.96 | (94.87–99.20) | 92.31 | (87.87–95.21) | 33.33 | (5.92-70.00) |

| Labial | 3 | 33.33 | 623 | 99.68 | 2 | 0.32 | 6 | 66.67 | 98.74 | 0.43 | 33.33 | (12.06–64.58) | 99.68 | (98.84–99.94) | 99.05 | (97.93–99.56) | 60.00 | (23.07–92.89) |

| Palatal/Lingual | 13 | 50.00 | 319 | 96.37 | 12 | 3.63 | 13 | 50.00 | 93.00 | 0.51 | 50.00 | (32.06–67.94) | 96.37 | (93.77–97.91) | 96.08 | (93.42–97.70) | 52.00 | (33.50-69.97) |

| Total | 23 | 36.51 | 1434 | 98.62 | 20 | 1.38 | 40 | 63.49 | 96.04 | 0.43 | 36.51 | (25.72–48.85) | 98.62 | (97.88–99.11) | 97.29 | (96.33-98.00) | 53.49 | (38.92–67.49) |

| Premolars | ||||||||||||||||||

| Occlusal | 96 | 94.12 | 302 | 87.54 | 43 | 12.46 | 6 | 5.88 | 89.04 | 0.80 | 94.12 | (87.76–97.28) | 87.54 | (83.63–90.61) | 98.05 | (95.82–99.10) | 69.06 | (60.95–76.15) |

| Proximal | 25 | 43.86 | 286 | 96.62 | 10 | 3.38 | 32 | 56.14 | 88.10 | 0.54 | 43.86 | (31.77–56.72) | 96.62 | (93.89–98.15) | 89.94 | (86.14–92.78) | 71.43 | (54.95–83.67) |

| Buccal | 1 | 11.11 | 445 | 99.11 | 4 | 0.89 | 8 | 88.89 | 97.38 | 0.14 | 11.11 | (0.57–43.50) | 99.11 | (97.73–99.65) | 98.23 | (96.55–99.10) | 20.00 | (1.03–62.45) |

| Palatal/Lingual | 1 | 25.00 | 255 | 99.61 | 1 | 0.39 | 3 | 75.00 | 98.46 | 0.33 | 25.00 | (1.28–69.94) | 99.61 | (97.82–99.98) | 98.84 | (96.64–99.68) | 50.00 | (2.57–97.44) |

| Total | 123 | 71.51 | 1288 | 95.69 | 58 | 4.31 | 49 | 28.49 | 92.95 | 0.70 | 71.51 | (64.35–77.73) | 95.69 | (94.47–96.65) | 96.34 | (95.19–97.22) | 67.96 | (60.85–74.32) |

| Molars | ||||||||||||||||||

| Occlusal | 340 | 94.44 | 261 | 81.56 | 59 | 18.44 | 20 | 5.56 | 88.38 | 0.90 | 94.44 | (91.58–96.38) | 81.56 | (76.95–85.43) | 92.88 | (89.26–95.35) | 85.21 | (81.39–88.36) |

| Proximal | 17 | 58.62 | 178 | 98.89 | 2 | 1.11 | 12 | 41.38 | 93.30 | 0.71 | 58.62 | (40.74–74.49) | 98.89 | (96.04–99.80) | 93.68 | (89.29–96.35) | 89.47 | (68.61–98.13) |

| Buccal | 37 | 88.10 | 180 | 93.26 | 13 | 6.74 | 5 | 11.90 | 92.34 | 0.80 | 88.10 | (75.00-94.81) | 93.26 | (88.82–96.02) | 97.30 | (93.83–98.84) | 74.00 | (60.45–84.13) |

| Palatal/Lingual | 17 | 89.47 | 175 | 95.63 | 8 | 4.37 | 2 | 10.53 | 95.05 | 0.77 | 89.47 | (68.61–98.13) | 95.63 | (91.61–97.77) | 98.87 | (95.97–99.80) | 68.00 | (48.41–82.79) |

| Total | 411 | 91.33 | 794 | 90.64 | 82 | 9.36 | 39 | 8.67 | 90.87 | 0.87 | 91.33 | (88.37–93.60) | 90.64 | (88.53–92.39) | 95.32 | (93.66–96.56) | 83.37 | (79.82–86.39) |

| All | 557 | 81.31 | 3516 | 95.65 | 160 | 4.35 | 128 | 18.69 | 93.40 | 0.79 | 81.31 | (78.22–84.06) | 95.65 | (94.94–96.26) | 96.49 | (95.84–97.04) | 77.68 | (74.49–80.58) |

ACC, accuracy; F1, F1 score; SE, sensitivity; SP, specificity; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; CI, confidence interval

Fig. 1.

Example images taken by intraoral camera and the corresponding results detected by the AI model. The caries areas were marked in green by the AI model automatically. The black arrow was added by the authors to indicate interproximal caries. All images associated with this study are available from the corresponding author (Y. G.) upon reasonable request

Discussion

In this prospective study, we evaluated the performance of a deep learning-based AI model for caries detection using intraoral images in a real-time clinical setting. The AI model, which combined MobileNet-v3 and U-net architectures, achieved an overall accuracy of 93.40% compared to professional clinical diagnosis. The highest diagnostic accuracy was observed in anterior teeth (96.04%), with premolars and molars also exceeding 90%. While the AI-assisted diagnosis showed high specificity (95.65%), the sensitivity was suboptimal at 81.31%. For specific tooth positions and types of caries, such as interproximal caries in anterior teeth and buccal caries in premolars, sensitivity was as low as approximately 10%. Consequently, the model exhibited a high negative predictive value (NPV) but a generally low positive predictive value (PPV).

The AI model’s architecture leverages the strengths of MobileNet-v3 for efficient feature extraction and U-net for precise pixel-level classification of caries lesions. MobileNet-v3’s compact design, incorporating depthwise separable convolutions, residual structures, and attention mechanisms, enables accurate predictions while maintaining low computational requirements, making it suitable for deployment on mobile devices [10]. The U-net architecture’s 5-layer upsampling and concatenation approach allows for detailed segmentation of caries lesions [11]. Recent studies utilizing digital photographs for caries diagnosis have demonstrated promising results. Employing a YOLOX-modified architecture, one study achieved an overall accuracy of 89.5% and an F1 score of 0.807 for caries detection [12]. Another study implemented a cascade R-CNN model, resulting in an average mean average precision score of 0.769 [13]. A Mobilenet V2 model tuned from only 2417 images demonstrated successful caries detection in 92.5% of cases [14]. These modeling efforts highlight the potential of deep learning in aiding clinical decision-making for caries diagnosis. Our study, which applied a well-trained model to a clinical outpatient population, corroborated these findings, suggesting the potential for AI-assisted caries detection in clinical practice.

However, our results revealed that while the model’s specificity was consistently high (> 95%), its sensitivity varied considerably (11.11–94.44%) depending on tooth position and caries type. This variability may be attributed to the complex clinical manifestations of caries, which can be more diverse than those represented in pre-existing datasets used in other studies [14]. The prospective design of our study, which enrolled consecutive patients visiting an endodontics clinic, likely captured a wider range of caries presentations compared to studies relying on curated datasets.

The limitations of image-based AI models in detecting visually subtle caries contributed to the higher number of false negatives in our study. This finding is consistent with the lower sensitivity reported in most image-based caries detection studies [15, 16]. Even for experienced clinicians, detecting early-stage caries often requires additional diagnostic methods, such as probing and radiography [17]. The reliance on visual information alone may not be sufficient for comprehensive caries detection, highlighting the need for multimodal diagnostic approaches.

The low PPV across all tooth positions and caries types suggests that the current AI model is more suitable as a screening tool and adjunct to clinical practitioners rather than a standalone diagnostic method. The high NPV might be influenced by the higher proportion of healthy teeth in the study population. It is important to consider that these findings are based on patients in a clinical setting; the PPV and NPV may differ in the general population with caries prevalence [18]. Therefore, the model’s performance should be interpreted in the context of the target population and the intended use case.

Given the inherent limitations of image-based AI models and the maturity of the model used in this study, further improvements in diagnostic performance may require the integration of multimodal data, such as information from laser-fluorescence detection [19], photothermal analysis [20], and radiography [21]. The development of multimodal diagnostic models represents a promising avenue for future research. By leveraging complementary information from various sources, AI models can potentially overcome the limitations of visual inspection alone and provide a more comprehensive assessment of caries presence and severity. While our study demonstrates the potential of AI in caries detection, its real-world value will depend on how effectively it can be integrated into clinical workflows and how it influences treatment planning and patient care. Longitudinal studies evaluating the long-term effects of AI-assisted caries detection on caries management and oral health outcomes would provide valuable insights into the clinical utility of these tools.

Another notable limitation of this study is the AI model’s focus on mineral loss detection rather than caries activity assessment. Future research should address this by incorporating longitudinal imaging at multiple time points to evaluate caries progression. The accessibility of photographic documentation presents an opportunity for patient-driven, longitudinal data collection, potentially reducing the frequency of clinical follow-ups and complex examinations. The integration of intraoral photography into daily oral hygiene regimens warrants exploration as a novel approach to caries prevention. This paradigm shift could significantly enhance early detection and intervention strategies in dental care.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the AI-assisted caries detection tool has potential for clinical application but still requires significant improvement. The integration of multimodal data and the development of more advanced AI models may enhance the sensitivity and overall performance of AI-assisted caries detection in clinical practice. Future research should focus on refining AI models, exploring multimodal diagnostic approaches, and evaluating the clinical impact of AI-assisted caries detection on patient care and outcomes.

Author contributions

Y.G designed the study, analyzed the data, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; J.Z. and F.Z. made substantial contributions to acquisition of data; J.F. tuned the algorithms and contributed to analysis of data; X.S. interpreted the data; J.Z. and B.M. had been involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20212BAB206084), the Guangdong Medical Research Foundation (A2023123) and President Foundation of ZhuJiang Hospital, Southern Medical University (YZJJ2022MS20).

Data availability

Update about the project can be screened on the Medical Research Registration System (medicalresearch.org.cn) of National Health Security Information Platform (MR-44-23-015681). All images involved in this study are available from the corresponding author (Y. G.), upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present clinical study obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University (2023-KY-050-01). The Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers prior to their participation. Detailed information about the project can be screened on the Medical Research Registration System (medicalresearch.org.cn) of National Health Security Information Platform (MR-44-23-015681).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jing-wen Zhang and Jie Fan contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Qing Shen, Email: 1061787412@qq.com.

Yuan-Ming Geng, Email: gym@smu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Si Y, Tai B, Hu D, Lin H, Wang B, Wang C, Zheng S, Liu X, Rong W, Wang W, et al. Oral health status of Chinese residents and suggestions for prevention and treatment strategies. Global Health J. 2019;3(2):50–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien KJ, Forde VM, Mulrooney MA, Purcell EC, Flaherty GT. Global status of oral health provision: identifying the root of the problem. Public Health Challenges. 2022;1:e6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez J. Detection and diagnosis of the early caries lesion. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(Suppl 1):S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kargozar S, Jadidfard MP. Teledentistry accuracy for caries diagnosis: a systematic review of in-vivo studies using extra-oral photography methods. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwendicke F, Samek W, Krois J. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: chances and challenges. J Dent Res. 2020;99(7):769–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moharrami M, Farmer J, Singhal S, Watson E, Glogauer M, Johnson AEW, Schwendicke F, Quinonez C. Detecting dental caries on oral photographs using artificial intelligence: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2024;30(4):1765–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding B, Zhang Z, Liang Y, Wang W, Hao S, Meng Z, Guan L, Hu Y, Guo B, Zhao R, et al. Detection of dental caries in oral photographs taken by mobile phones based on the YOLOv3 algorithm. Annals Translational Med. 2021;9(21):1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohammad-Rahimi H, Motamedian SR, Rohban MH, Krois J, Uribe SE, Mahmoudinia E, Rokhshad R, Nadimi M, Schwendicke F. Deep learning for caries detection: a systematic review. J Dent. 2022;122:104115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen PE, Baez RJ, World Health Organization. &. Oral health surveys: basic methods, 5th ed. World Health Organ 2013. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/97035

- 10.Howard A, Sandler M, Chen B, Wang W, Chen L, Tan M, Chu G, Vasudevan V, Zhu Y, Pang R et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.02244

- 11.Park EY, Cho H, Kang S, Jeong S, Kim EK. Caries detection with tooth surface segmentation on intraoral photographic images using deep learning. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong Y, Zhang H, Zhou S, Lu M, Huang J, Huang Q, Huang B, Ding J. Simultaneous detection of dental caries and fissure sealant in intraoral photos by deep learning: a pilot study. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon K, Jeong HM, Kim JW, Park JH, Choi J. AI-based dental caries and tooth number detection in intraoral photos: model development and performance evaluation. J Dent. 2024;141:104821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kühnisch JA-O, Meyer O, Hesenius M, Hickel R, Gruhn V. Caries Detection on Intraoral images using Artificial Intelligence. J Dent Res. 2022;101(2):158–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Liang Y, Li W, Liu C, Gu D, Sun W, Miao L. Development and evaluation of deep learning for screening dental caries from oral photographs. Oral Dis. 2022;28(1):173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thanh MT, Van Toan N, Ngoc VT, Tra NT, Giap CN, Nguyen DM. Deep learning application in Dental Caries Detection using intraoral photos taken by smartphones. Appl Sci. 2022;12(11):5504. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JA-OX, Kruger E, Nicholls W, Estai M, Winters J, Tennant M. Comparing the outcomes of gold-standard dental examinations with photographic screening by mid-level dental providers. Clin oral Invest. 2019;23(5):2383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elger WA-O, Kiess W, Körner A, Schrock A, Vogel M, Hirsch C. Influence of overweight/obesity, socioeconomic status, and oral hygiene on caries in primary dentition. J Invest Clin Dent. 2019;10:e12394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreher D, Schmalz G, Haak R, Ziebolz D. Laser fluorescence is a predictor of lesion depth in non-cavitated root carious lesions - an in vitro study. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2023;41:103243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elnaz Baradaran S, Damber T, Robert W, Koneswaran S, Andreas M. Quantitative photothermal analysis and multispectral imaging of dental structures: insights into optical and thermal properties of carious and healthy teeth. J Biomed Opt. 2024;29(1):015003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heck K, Litzenburger F, Ullmann V, Hoffmann L, Kunzelmann KH. In vitro comparison of two types of digital X-ray sensors for proximal caries detection validated by micro-computed tomography. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2021;50(3):20200338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Update about the project can be screened on the Medical Research Registration System (medicalresearch.org.cn) of National Health Security Information Platform (MR-44-23-015681). All images involved in this study are available from the corresponding author (Y. G.), upon reasonable request.