Abstract

Context:

Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is a very rare but deadly infection of the central nervous system. Since the disease was first identified in 1965, fewer than 200 cases have been observed worldwide.

Objective:

The author performed a literature review of the reports of PAM in Thailand in order to study the clinical summary of PAM among Thai patients.

Design:

This study was designed as a descriptive retrospective study. A literature review of the papers concerning PAM in Thailand was performed.

Results:

According to this study, there have been at least 12 reports of PAM in Thailand, of which 2 cases were nonlethal. The mean age was 15.2 ± 16.1 years with a male:female ratio of about 2:1. History of risk behaviors such as suffocation of surface water during swimming was demonstrated in 6 cases. Also, 2 interesting cases involved possible water contact according to the Thai tradition and culture. Concerning the patients' clinical features, fever, headache, impaired consciousness, and stiff neck were seen in all cases. However, some unusual presentations such as intermittent abdominal pain and convulsion were also seen in this series. Similar to worldwide findings, most cases occurred during the summer months. Most of the cases involved young males from rural provinces in various regions of Thailand. Concerning the laboratory investigation, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) profile presented the polymorphonuclear (PMN) pleomorphic with hypoglycorhachia pattern. Trophozoite could be identified in all but 2 cases in this series.

Conclusion:

PAM is sporadically reported in Thailand but remains a public health issue. The clinical diagnosis of PAM is usually difficult as many clinicians are unfamiliar with the disease. The prognosis outcome is usually grave although broad medications are prescribed.

Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is a very rare but deadly infection of the central nervous system.

Introduction

PAM is a very rare disease of the brain.[1] Naegleria fowleri is the principal protozoa, commonly referred to as pathogenic free-living amoebae, that causes PAM.[2] PAM occurs very rarely but is usually fatal. Since the disease was first identified in 1965,[3] fewer than 200 cases have been identified worldwide.[1,2,4] N fowleri are ubiquitous in the environment, in soil, water, and air.[5] Infections in humans are rare and are acquired through water entering the nasal passages (usually during swimming) and by inhalation.

Most human victims of PAM are exposed to free-living amoebae while swimming in warm surface water. This may include ponds, lakes, streams, rivers, and improperly maintained swimming pools. The risk of acquiring PAM increases as water temperatures rise.[1,5] Transmission to humans occurs when the organism gains access to brain tissues through the nasal passages. The organism can enter the nasal passages when water containing the organism is forced up the nose through activities such as diving, jumping into water, and underwater swimming. Luckily, PAM is not transmitted from person to person.[1,2,4]

In Thailand, the first case report of PAM was published in 1983 by Jariya and colleagues.[6] Since the first case report, there have been sporadic reports of PAM in Thailand. Here, the author performed a literature review on the reports of PAM in Thailand in order to study the clinical summary of PAM among Thai patients.

Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a descriptive retrospective study. The author performed the literature review on PAM reports in Thailand from a database of the published works cited in the Index Medicus and Science Citation Index. The author also reviewed the published works in all 256 local Thai journals that are not included in the international citation index for reports of PAM in Thailand. The literature review was focused on the years 1983 to 2001.

As a result of the literature review, 9 reports were recruited for further study. The details of clinical presentations of the patients (such as clinical manifestation, history of risk behavior, length of stay in the hospital, diagnosis, treatment, and discharge status) in all included reports were studied. The demographic data of all cases, including age, sex, and address, were reviewed as well. Descriptive statistics were used in analyzing the patient characteristics and laboratory parameters for each group. All of the statistical analyses in this study were made using SPSS 7.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

According to this study, there have been reports of at least 12 incidences of PAM, of which 2 cases were nonlethal (Table 1). The mean age was 15.2 ± 16.1 years (range, 8 months–61 years) with a male:female ratio of about 2:1. According to the series, only 9 cases (66.7%) had a history of exposure to water, while the other 3 cases were without clear history. Concerning these 9 cases, history of suffocation of surface water during swimming was demonstrated in 6 cases. The possible sources of surface water were ponds along the water supply canal (3 cases), rice field ponds (1 case), rivers (1 case), and community pools (1 case). Of the other 3 cases, 1 presented with a history of exposure to water during Songkran, the traditional Thai festival in which celebrants throw water at each other, 1 presented with a history of falling into a drain in a garden, and 1 presented with a history of exposure to holy water from a Buddhist temple.

Table 1.

Clinical Presentations of the 12 Thai Cases of PAM

| No | Year (authors) | Age (years) | Sex | Address* | Period of Onset† | Length of Hospitalization | Primary Diagnosis | Treatment | Discharge Status |

| 1 | 1983 (Jariya et al) |

5 | Male | NE | Rainy season | 3 days | CSF examination | No specific treatment | Dead |

| 2 | 1987 (Somboonyosdej et al) |

14 | Male | E | Summer | 10 hours | CSF examination | IV penicillin, oral metronidazole, & chloramphenicol | Dead |

| 3‡ | 1987 (Somboonyosdej et al) |

0.67 | Male | E | Summer | 12 hours | CSF examination | IV gentamicin, oral rifampicin & ampicillin & metronidazole | Dead |

| 4 | 1988 (Charoenlarp et al) |

17 | Male | C | Summer | 2 days | CSF examination | IV & IT amphotericin B, oral rifampicin & Sulfadiazine & tetracycline | Dead |

| 5 | 1989 (Sirinavin et al) |

4.5 | Female | C | Summer | 5 days | CSF examination | IV amphotericin B, oral rifampicin | Dead |

| 6 | 1991 (Poungvarin et al) |

61 | Male | NE | Summer | 30 days | CSF examination | IV amphotericin B, oral rifampicin & ketoconazole | Cure |

| 7 | 1993 (Chotmongkol et al) |

18 | Female | NE | Summer | 30 days | CSF examination | IV amphotericin B, oral rifampicin & iraconazole | Cure |

| 8 | 1996 (Wattanaweeradej et al) |

5 | Male | C | Summer | 6 days | CSF examination | IV amphotericin B, oral rifampicin | Dead |

| 9 | 1997 (Viriyavejakul et al) |

12 | Male | C | Summer | 5 days | Autopsy | No specific treatment | Dead |

| 10‡ | 1997 (Petchsuwan et al) |

9 | Female | N | Summer | 14 days | Autopsy | No specific treatment | Dead |

| 11‡ | 2000 (Bunjongpak) |

9.75 | Female | NE | Summer | 2 days | Autopsy | No specific treatment | Dead |

| 12 | 2001 (Sithinamsuwan et al) |

27 | Male | C | Summer | 4 days | CSF examination | IV & IT amphotericin B, oral rifampicin | Dead |

*Address is classified according to the region of Thailand: NE = Northeastern, C = Central, E = Eastern, N = Northern

†There are 3 seasons in Thailand: summer (February–May), rainy season (June–September), and winter (October–January)

‡Cases 3, 10, and 11 had no clear history of water exposure.

The patients' clinical features on admission are shown in Table 2. Fever, headache, impaired consciousness, and stiff neck were seen in all cases. On admission, complete blood count (data available in 5 cases) showed an average white blood count of 16.0 ± 7.9 × 1000 WBC/mm3 (range, 6.5–26.4 WBC/mm3) and an average relative neutrophil count of 79.0% ± 12.1% (range, 58% to 88%). The lumbar puncture revealed an increased white blood count (average, 5.7 ± 8.9 × 1000 WBC/mm3; range, 0.2–23.0 × 1000 WBC/mm3) with PMN cell predominance (average, 93.1% ± 7.7%; range, 82% to 100%). Average CSF protein and glucose were 568.1 ± 248.9 mg/dL (range, 284.1–1020 mg/dL) and 13.2 ± 11.1 mg/dL (range, 0–22 mg/dL), respectively. In 9 cases, the primary diagnosis of PMN was made by detection of the organism in the CSF. The other 3 cases were primarily diagnosed by autopsy. In all cases, the organisms were identified on smear and confirmed by culture. All incidences of death occurred within 1 week after admission (average, 3.2 ± 2.1 days; range, 10 hours–6 days). Of the 10 cases of death, autopsy studies were performed in 8 cases and revealed the brain pathology as diffuse exudative with hemorrhagic pattern and several Naegleria trophozoites.

Table 2.

Clinical Manifestations on Admission in 12 Cases With PAM

| Clinical Manifestations | Number of Patients (%) |

| Fever | 12 (100%) |

| Headache | 12 (100%) |

| Impaired consciousness | 12 (100%) |

| Stiff neck | 12 (100%) |

| Vomiting | 3 (25.0%) |

| Convulsion | 2 (16.7%) |

| Running nose | 1 (8.3%) |

| Blurred vision | 1 (8.3%) |

| Intermittent abdominal pain | 1 (8.3%) |

| Deviated gait | 1 (8.3%) |

Discussion

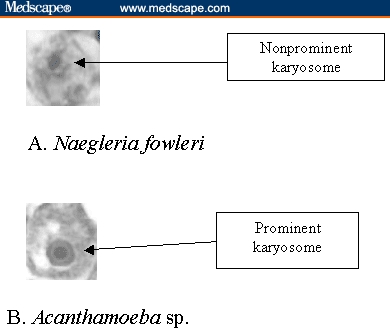

PAM is the most deadly infection of the central nervous system apart from rabies. It is rare but fatal. Since the first report in 1965,[3] fewer than 200 cases have been reported worldwide, from the United States, England, Eastern Europe, Africa, and Asia.[1,2,4] However, the causative organism is thermophilic and grows well in tropical and subtropical climates, so most cases have been reported from those areas.[1] In Thailand, PAM has been sporadically reported since 1983.[6] In this review, only 12 cases of PAM in Thai patients were detected and used for further analysis.[6-16] All of these patients were confirmed for this infection; other similar amoeba infections were ruled out, especially Acanthamoeba or Hartmanella sp., which can produce a similar illness. A summative description with photomicrographs to help readers depict the organisms is presented in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3.

| Items | Naegleria fowleri | Acanthamoeba sp. |

| 1. Pathologic presentation | Presented as PAM, usually acute | Presented as granulomatous amoebic encephalitis or keratitis, usually subacute |

| 2. Background | History of water exposure | Impaired immunity |

| 3. Organism morphology | 10–15 mcg trophozoite with nonprominent karyosome | 25–35 mcg trophozoite with prominent karyosome |

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of Naegleria fowleri compared with similar amoeba

The clinical symptoms and signs in the Thai patients with PAM were similar to those in previous reports.[17] The symptoms and signs such as fever, headache, impaired consciousness, and stiff neck can be found in all cases. Some patients presented symptoms similar to those found in upper respiratory tract infections, such as running nose, as well. According to the literature review, most cases of PAM are usually misdiagnosed as acute bacterial meningitis and delayed for specific treatment. However, some unusual presentations such as intermittent abdominal pain and convulsion can be seen.

Epidemiologic data from the patients with PAM in Thailand agree with the worldwide finding that the cases usually occur during the summer months.[1,18] Since raised temperatures during the hot summer months facilitate the growth of the pathogenic thermophilic amoeba, high prevalence in the summer can be expected.[1] Most of the cases were young males from the rural provinces of various regions of Thailand. Indeed, due to the hot weather during summer months, most of rural Thai children prefer swimming in nearby water reservoirs. Therefore, accidental suffocation of the surface water can be expected. According to this series, none of the patients had been exposed to a common source. Surface water from most of the referred water sources was collected for further investigation and the culture revealed contamination of the organism. Indeed, this organism can be found elsewhere, in water, air, and soil.[5] According to a recent surveillance of water from 162 sources in Thailand,[19] up to 70% of samples were contaminated with this organism.

Of interest, there were also some cases without a history of swimming. One case yielded a history of water exposure during the Thai water festival Songkran, during which the people splash water on each other, practicing a tradition called “playing water.”[8] This festival is rooted deeply among the Thais; if there is no control of the water quality for “water playing,” similar cases of PAM can be expected. Another interesting case depicted a male patient with a history of exposure to holy water.[16] Holy water is another facet of old culture among the Thais; many believe that holy water has spiritual power and can bring good luck to them. Generally, holy water is prepared by a Buddhist monk in the temple; the water actually originates from several sources. The monk splashes the holy water onto the head and face of the believers; therefore, if contaminated water is used to prepare holy water, invasion of the pathogenic organism through the nasal passage can be expected. According to a recent study,[20] most of the holy water in rural areas is contaminated with many bacteria; therefore, additional surveillance of contamination by this pathogenic organism is needed.[16,21]

Concerning the laboratory investigation, the neutrophilia can be detected from complete blood count. In most cases, the CSF profile presented the PMN pleomorphic with hypoglycorhachia pattern. These findings are similar to the CSF profile in acute bacterial meningitis; the detection of amoebic trophozoite in the CSF requires an experienced microscopist.[21] In this series, there were 3 cases in which the organism could not be detected in the CSF despite the fact that there were numerous organisms detected in the autopsy study. Inability to detect the amoebic trophozoite can be another cause of delayed specific treatment. In this series, all cases had already been treated as bacterial infections before the diagnosis of PAM was made. The summative distinction between bacterial meningitis and PAM is presented in Table 4.[22] PAM should be considered in any patient with a previous history of water exposure and presenting with pyogenic meningitis without evidence of bacteria by staining, antigen detection, and culture.[23] In those cases, specific free-living amoeba culture is recommended.[23]

Table 4.

The Summative Distinction Between Bacterial Meningitis and PAM

| Item | Bacterial Meningitis | PAM |

| 1. Supportive clinical history | With history of previous bacterial infection | With history of exposure to water expsoure |

| 2. CSF profile[22] | PMN pleomorphic with hypoglycorhachia pattern | PMN pleomorphic with hypoglycorhachia pattern but mobile amoebic organism can be seen |

| 3. Culture method[22] | Routine bacterial culture | Specific free-living amoeba culture |

Concerning the treatment and outcome, the literature review shows that PAM is a fatal disease, and there is no gold standard regimen for therapy. However, there were 2 nonfatal cases in our series.[10,11] These 2 cases were diagnosed early, and the history of water exposure was well derived. In the first nonlethal case, the combination of intravenous amphotericin B for 14 days and oral rifampicin and oral ketoconazole for 1 month cured the patient with no recurrence.[10] In the other nonlethal case, the combination of intravenous amphotericin B for 14 days and oral rifampicin and oral itraconazole for 1 month cured the patient with no recurrence as well.[11] These 2 cases represent the very rare condition of nonfatal PAM, of which there are fewer than 10 records in the literature.[10,11,24-26]

In this series, there was 1 case with concomitant involvement of the spinal cord. This case is the third case in the world with this presentation. This case was the case with primary diagnosis of PAM by autopsy[13]; unlike the previous cases with spinal cord involvement,[27] the signs and symptoms of spinal cord damage were not clinically detected because the patient was unconscious throughout hospitalization.

If we compare the cases from Thailand with reports from another country, namely Australia, there seem to be more cases from Australia. In Australia, the problem usually occurs in summer, like in the Thai study, when people swim in public pools. Thus, swimming pool control is an important preventive strategy for free-living amoebic infection.[28-30] A strong positive association of free chlorine with bacteriologic quality and the absence of Naegleria sp. has been mentioned.[28] Water supply drained through pipes placed on the ground facilitates growth of the amoebae and subsequently causes the problem. According to a study by Dorsch and colleagues,[29] public pools, rather than the domestic environment, are a potential source of infection; the importance of free chlorine in control of Naegleria sp. is mentioned. Of interest, treatment with rifampicin or tetracycline combined with amphotericin, similar to the present study, is recommended as well.

In conclusion, PAM is a fatal CNS infection that is sporadically reported in Thailand but remains a public health concern.[20] The clinical diagnosis of PAM is usually difficult because of the scarcity of cases and clinicians' unfamiliarity with the infection. The prognosis is usually grave although broad medications are prescribed.

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; IV = intravenous; IT = intrathecal

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; PMN = polymorphonuclear

References

- 1.Martinez AJ. Free-living, amphizoic and opportunistic amebas. Brain Pathol. 1997;7:583–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1997.tb01076.x. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parija SC, Jayakeerthee SR. Naegleria fowleri: a free living amoeba of emerging medical importance. J Commun Dis. 1999;31:153–159. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler N, Carter RT. Acute pyogenic meningitis probably due to Acantamoeba sp: a preliminary report. Br Med J. 1965;2:740–742. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5464.734-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ockert G. Review article: occurrence, parasitism and pathogenetic potency of free-living amoeba. Appl Parasitol. 1993;34:77–88. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Zaragoza S. Ecology of free-living amoebae. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1994;20:225–241. doi: 10.3109/10408419409114556. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jariya P, Makeo S, Jaroonvesama N, Kunaratanapruk S, Lawhanuwat C, Pongchaikul P. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: a first reported case in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1983;14:525–527. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somboonyosdej S, Pinkaew P. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: a report of two cases in Trad Hospital. J Ped Soc Thai. 1987;26:6–8. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charoenlarp K, Jariya P, Junyandeegul P, Panyathanya R, Jaroonvesama N. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: a second reported case in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 1988;71:581–586. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirinavin S, Jariya P, Lertlaituan P, Chuahirun S, Pongkripetch M. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in Thailand: report of a case and review literatures. J Med Assoc Thai. 1989;72(suppl 1):174–176. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poungvarin N, Jariya P. The fifth nonlethal case of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. J Med Assoc Thai. 1991;74:112–115. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chotmongkol V, Pipitgool V, Khempila J. Eosinophilic cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis and primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1993;24:399–401. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wattanaweeradej W, Rudeewilai S, Simasathien S. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis: the first case report in Pramongkutklao Hospital and literature review. Royal Thai Army Med J. 1996;49:221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viriyavejakul P, Rochanawutanon M, Sirinavin S. Case report: Naegleria meningomyeloencephalitits. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28:237–240. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petchsuwan K, Reungsuwan S. Pathology and cytology of primary amoebic meningoenephalitis. Buddhachinaraj Med J. 1997;15:62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bunjongpuk S. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) Thai J Ped. 2000;39:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sithinamsuwan P, Sangruchi T, Chiewvit P, Poungvarin N. Free living ameba infections of the central nervous system in Thailand. Report of two patients. Int Med J Thai. 2000;17:350–360. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett ND, Kaplan A, Hopkin RJ, Saubolle MA, Rudinsky MF. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis with Naegleria fowleri: clinical review. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;15:230–234. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(96)00173-7. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon MW, Wilson D. The amoebic meningoencephalitis. Ped Infect Dis J. 1986;5:562–569. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198609000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jariya P, Taeowcharoen S, Lertlaiduan P, Junnoo W, Suwittayasiri W. Survey of Naegleria fowleri the causative agent of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) in stagnant waters around factory area in Thailand. Siriraj Hosp Gaz. 1997;49:222–229. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phatthararangrong N, Chantratong N, Jitsurong S. Bacteriological quality of holywater from Thai temples in Songkhla Province, southern Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 1998;81:547–550. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanachiwanawin D. What have we learnt from recent infection of the pathogenic free-living protozoa in Thailand?; Program and abstracts of the Joint International Tropical Medicine Meeting 2001; August 8–10, 2001; Bangkok Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiwanitkit V. Cerebrospinal fluid examination and interpretation. Buddhachinaraj Med J. 2000;17:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain RR, Prabhakar SS, Modi MM, Bhatia RR, Sehgal RR. Naegleria meningitis: a rare survival. Neurology India. 2002;50:4702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson K, Jameison A. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. Lancet. 1972;1:902–903. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)90772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apley J, Clarke SKR, Roome AP, et al. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in Britain. Br Med J. 1970;1:596–599. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5696.596. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang A, Kay R, Poon WS, Ng HK. Successful treatment of amoebic meningoencephalitis in a Chinese living in Hong Kong. Clin Neuro Neurosurg. 1993;95:249–252. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(93)90132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duma RJ, Rosenblum WI, McGehee RF, Jones MM, Nelson EC. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria. Two new cases, response to amphotericin B, and a review. Ann Intern Med. 1971;74:921–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-6-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esterman A, Roder DM, Cameron AS, et al. Determinants of the microbiological characteristics of South Australian swimming pools. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:325–328. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.2.325-328.1984. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorsch MM, Cameron AS, Robinson BS. The epidemiology and control of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis with particular reference to South Australia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:372–377. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90167-0. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller G, Cullity G, Walpole I, O'Connor J, Masters P. Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 1982;1:352–357. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1982.tb132348.x. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]