Abstract

The diagnosis of Takayasu's arteritis can be made reliably in the absence of angiography and histopathology based on established criteria

The patient was well until 2 months prior to admission, when she developed bilateral lower extremity claudication. The pain progressed gradually until it occurred at rest. She also experienced fatigue and fevers. The legs slowly became black below the knees. She presented to an outside hospital, where she was given unknown treatment without improvement. Her family requested transfer to our institution.

Cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, and orthopnea were absent, as were abdominal complaints.

Past Medical History: None.

Medications: None.

Social History: The patient is a housewife. She does not smoke tobacco or drink alcohol.

Family History: Noncontributory.

Physical Exam: The blood pressure was 132/78 mm Hg in the right arm and 136/86 in the left. The pulse was 130/minute, respiratory rate 28/minute, temperature 39.5° Celsius, and oxygen saturation 88% breathing ambient air. The patient appeared acutely toxic and was delirious. She was oriented to person and place but not to time and could not understand her condition. The oropharynx was clear and there was no scleral icterus. The neck was supple and the jugular venous pressure elevated. Palpable lymphadenopathy was absent. She had a tachycardic but regular rhythm with an S4 gallop. Cardiac auscultation revealed a harsh 2/6 aortic and 3/6 pulmonic systolic murmur. Bruits could be heard in the right subclavian, right carotid, and left renal arteries. The brachial and radial pulses were palpable and equal bilaterally, but the femoral, popliteal, and pedal pulses were absent. Lung examination revealed rales in the left base. The abdomen was soft. Below the knees, both legs, right more than left, were cold, black, and wooden without sensation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The patient's legs at presentation

Data: hemoglobin 3.2, hematocrit 12.4, white blood cell count 16,000 with 75% polymorphonuclear cells. The mean corpuscular volume was 52 and the platelet count 333,000. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate measured greater than 130. Chemistries revealed sodium 117, potassium 2.6, and creatinine 1.1. A malaria smear and serum VDRL were negative. Blood cultures were also ultimately negative.

An anteroposterior chest x-ray suggested possible widening of the mediastinum. Cardiac ultrasound showed normal left ventricular function. The aortic root diameter was within normal limits, measuring 2.2 centimeters. Abdominal ultrasound was unrevealing.

A clinical diagnosis was made based on established diagnostic criteria.

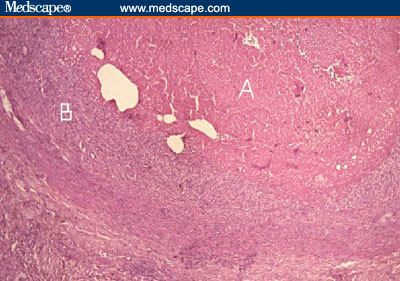

The following day, the patient underwent bilateral above-the-knee amputations. Blood flow was poor at the stump sites. The femoral arteries were involved bilaterally. The gross findings were similar (thrombosed vessel with minimal blood flow), but only one was sent for pathology (Figure 2). On histology, transmural arteritis was evident (Figure 3; label B) and organizing thrombus occluded the lumen (Figure 3; label A). The intima was obscured by inflammation and thrombus.

Figure 2.

Grossly thrombosed femoral artery found at surgery

Figure 3.

Microscopically, there was organizing thrombus occluding the lumen (A) and transmural arteritis involving the vessel wall (B)

Takayasu's arteritis, also known as pulseless disease, is a large vessel vasculitis usually involving the aorta, its main offshoots, and the upper extremities. It occurs much more frequently in women than men and primarily affects individuals younger than 40 years of age. Although more common in Asian populations, the disease occurs worldwide.[1]

Constitutional symptoms, such as malaise and fatigue, are common, and in the West patients usually do not initially present with vascular complaints, the most common of which is extremity claudication. Coronary, mesenteric, and cerebral ischemia may all occur, and the pulmonary artery may be involved in up to half of cases. Arthralgias and erythema nodosum are other potential manifestations.

Although angiography is available at our institution, the capabilities are limited and the surgeon expressed concern regarding vascular access. The diagnosis of Takayasu's arteritis can be made reliably in the absence of angiography and histopathology based on established criteria:[2]

Disease onset prior to 40 years of age;

Extremity claudication;

Decreased brachial artery pressure;

Upper extremity blood pressure differential more than 10 mm Hg;

Subclavian or aortic bruit; and

Arteriographic evidence of arterial narrowing or occlusion of the aorta, its primary branches, or large arteries of the upper or lower extremities that is not attributable to another cause (eg, atherosclerosis).

This patient met criteria (1), (2), and (5). The diagnosis can be made if 3 of the 6 criteria are met. This standard yields a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 97%. In this case, the upper extremities did not appear to be markedly affected; the subclavian bruit disappeared as the patient's coexisting sepsis and tachycardia resolved, but later an abdominal bruit was also appreciated. Multiple measurements, both manual and automated, failed to detect a blood pressure differential between the arms. Patients often have hypertension, and it is possible that measurement of central aortic pressures would have been high but that similar degrees of upper extremity artery involvement masked this state. In 17% of cases, the iliac and its branches are involved, as with this patient.[3]

Major considerations in the differential diagnosis include syphilitic aortitis and giant cell arteritis. The negative VDRL and peripheral arterial involvement were not consistent with syphilis. Giant cell arteritis occurs in older populations and generally has a different vascular distribution. Endocarditis should also be considered, but the widespread bruits, negative blood cultures, and subsequent course (see below) argued against this diagnosis.

The mainstay of treatment for Takayasu's arteritis is corticosteroids, although disagreement exists as to whether this therapy alters the ultimate prognosis. The dose can be tapered as the signs and symptoms of inflammation subside. For patients not achieving a remission with steroids, methotrexate has shown promise,[4] while there are fewer data to recommend cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil. Fixed stenoses will not respond to immunosuppression, and angioplasty may be warranted.

Initiation of steroids was delayed because the patient developed a large sacral decubitus ulcer with exposed bone. Also, both stumps began to break down, causing concern that the patient may require bilateral hip disarticulation. She remained tachycardic but otherwise well, and her wounds healed slowly. Approximately 2 months after admission, the patient suddenly became delirious and febrile, followed by a seizure. The white blood cell count was 16,000 and a smear for malaria parasites negative. Dexamethasone at a dose of 12 mg every 6 hours was administered intravenously (the equivalent of 500 mg of methylprednisolone), and by the next morning, she had returned to baseline. She was maintained on prednisolone 40 mg twice per day and discharged. She returned 1 month later having exhausted her supply of steroids several days previously. She was tachycardic and complaining of abdominal pain; the stump sites were healed. Her family declined admission, citing distance and expense. Steroids were restarted. After 13 additional months, the patient has not returned for follow-up.

References

- 1.Hunder GG. Takayasu's arteritis. In: Rose BD, editor. UpToDate. Wellesley Mass: UpToDate; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arend WP, Michel BA, Block MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;330:1129. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fauci AS. The vasculitis syndromes. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al., editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 14th ed. New York NY: McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, Kerr GS, et al. Treatment of glucocorticoid-resistant or relapsing Takayasu arteritis with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:578–582. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370420. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]