Abstract

Objective

To identify FPs with additional training and focused practice activities relevant to the needs of older patients within health administrative data and to describe their medical practices and service provision in community-based primary care settings.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Ontario.

Participants

Family physicians with Certificates of Added Competence in care of the elderly from the College of Family Physicians of Canada or focused practice billing designations in care of the elderly.

Main outcome measures

Evidence of additional training or certification in care of the elderly or practice activities relevant to the care of older adults.

Results

Of 14,123 FPs, 242 had evidence of additional scope to better support older adults. These FPs mainly practised in team-based care models, tended to provide comprehensive care, and billed for core primary care services. In an unadjusted analysis, factors statistically significantly associated with greater likelihood of having additional training or focused practices relevant to the care of older patients included physician demographic characteristics (eg, female sex, having completed medical school in Canada, residential instability at the community level), primary care practice model (ie, focused practice type), primary care activities (eg, more likely to provide consultations, practise in long-term care, refer patients to psychiatry and geriatrics, bill for complex house call assessments, bill for home care applications, and bill for long-term care health report forms), and patient characteristics (ie, older average age of patients).

Conclusion

The FP workforce with additional training or focused practices in caring for older patients represents a small but specialized group of providers who contribute a portion of the total primary care activities for older adults. Health human resource planning should consider the contributions of all FPs who care for older adults, and enhancing geriatric competence across the family medicine workforce should be emphasized.

Résumé

Objectif

Repérer, dans les données administratives sur la santé, les médecins de famille qui possèdent une formation supplémentaire ou qui mènent des activités de pratique ciblées en rapport avec les besoins des patients âgés, et décrire leurs pratiques médicales et les services qu’ils offrent dans des milieux de soins communautaires de première ligne.

Type d’étude

Étude de cohorte rétrospective.

Contexte

L’Ontario.

Participants

Médecins de famille possédant un certificat de compétence additionnelle en soins aux personnes âgées du Collège des médecins de famille du Canada ou utilisant des désignations de facturation liées à la pratique ciblée sur les soins aux aînés.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Preuve de formation supplémentaire ou de certification additionnelle en soins aux personnes âgées ou d’activités de pratique en rapport avec ces soins.

Résultats

Les auteurs ont constaté que 242 des 14 123 médecins de famille avaient une portée de pratique supplémentaire pour mieux soutenir les personnes âgées. Ces médecins travaillaient surtout dans des modèles de soins dispensés en équipe, avaient tendance à fournir des soins complets et facturaient des services de soins primaires de base. Dans une analyse non ajustée, des facteurs statistiquement significatifs ont été associés à une plus grande probabilité de formation supplémentaire ou de pratique ciblée relatives avec les soins aux personnes âgées. Il s’agit des caractéristiques démographiques du médecin (p. ex. le sexe féminin, le fait d’avoir fait ses études de médecine au Canada, l’instabilité de la résidence au niveau communautaire), du modèle de pratique des soins primaires (c.-à-d. un type de pratique ciblé), des activités liées aux soins primaires (p. ex. une plus grande probabilité de donner des consultations, de pratiquer en soins de longue durée, de demander des consultations en psychiatrie et en gériatrie, et de facturer des évaluations complexes à domicile et des demandes de soins à domicile, et de facturer pour remplir des formulaires de rapports sur la prestation de soins de longue durée) et des caractéristiques des patients (c.-à-d. leur âge moyen plus avancé).

Conclusion

L’effectif de médecins de famille qui possèdent une formation supplémentaire ou une pratique ciblée sur les soins aux personnes âgées représente un groupe petit, mais spécialisé de fournisseurs qui consacrent une partie de leurs activités de soins primaires à cette population. Pour la planification des ressources humaines en santé, il faudrait tenir compte des contributions de tous les médecins de famille qui prodiguent des soins aux aînés et mettre l’accent sur l’amélioration des compétences en gériatrie de l’effectif des médecins de famille.

Primary care systems across the world are grappling with shortages in the FP workforce1-4 prompted by exits from practice during the COVID-19 pandemic,5 narrowing scopes of practice,6 and waning interest in comprehensive family medicine.7,8 While family medicine involves caring for patients across the age spectrum, FPs are central to the care of older persons.9 Compared with other age groups, older adults (aged ≥65 years) are the most frequent users of primary care services, accounting for almost one-third of family medicine services.9 Older patients’ greater medical complexity and chronicity and higher rates of health service use across settings are best managed when FPs play a central role in care coordination and continuity of care.10 However, as the population of older adults continues to expand, gaps between what older patients need and what FPs have the capacity to provide are also growing.11

Comprehensive primary care is associated with better health equity and efficiency, care continuity, and patient and provider satisfaction, as well as with fewer emergency department visits, hospital admissions, specialist referrals, and health system costs.12-18 Despite the centrality of comprehensiveness to family medicine training and professional identity,19 FPs are increasingly choosing to provide comprehensive care to distinct population groups or focus their practices in specific clinical areas.20-25 Pursuit of additional training or focused scope of practice is driven by many factors, including geography, remuneration, personal interests or values, support from colleagues, positive training experiences, and desire to decrease breadth to handle complexity in a focused area.20,26-29 There is a gap in understanding factors associated with FPs acquiring additional skills or using billing designations specific to the needs of older patients, including the range of clinical services delivered.

Family physicians with additional training or focused practices related to the care of older adults are not identified in health administrative data. In the absence of a validated classification, little is known about their individual and practice characteristics, including their impact on quality of care and patient outcomes. We aimed to identify FPs with additional training or certification in care of the elderly (COE) or who practise with a focus on care of older adults within population-based health administrative data holdings in Ontario. We then sought to describe their medical practice characteristics and service provision.

METHODS

Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to examine the characteristics of FPs with additional training and practice activities suggesting a focus on older adults in the 2019 calendar year. Our reporting follows the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement (Appendix 1, available from CFPlus*).30

Data sources

We linked multiple data sets at ICES, an independent, non-profit research institute that collects and analyzes health care and demographic data about publicly funded encounters in Ontario (Appendix 2, available from CFPlus*).31 Data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. We conducted a project-specific linkage with the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) membership database for physicians with Certificates of Added Competence (CACs) in COE. Data were accessed using the ICES remote access environment. We ascertained most responsible provider (MRP) practice in long-term care (LTC) using a previously established classification.32

Sample

We established a cohort of physicians who had submitted at least 1 Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) fee claim in 2019. We excluded physicians whose main specialty in the ICES physician database was not family medicine or general practice and we excluded nonresidents of Ontario.

We identified FPs with additional training or a focus on older adults using 2 methods related to their education or training and practice organization. First, we identified FPs with CACs in COE (CAC-COE) by importing a validated list from the CFPC.33,34 Second, we classified physicians as “focused scope of practice in COE” (FSP-COE) if they had submitted at least 1 billing for 1 of the 5 OHIP fee codes eligible to FPs enrolled in a focused practice funding arrangement in COE.35,36 Our methodology is detailed in Appendix 3, available from CFPlus.*

Physicians who did not fall within our classification of having additional skills in COE were grouped together, although they exhibit heterogeneity; some provide comprehensive care, hold CACs in other domains of care, or have focused practices in other domains of care.

Analysis

We reported measures of central tendency in descriptive tables (eg, medians and interquartile ranges [IQRs] for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables). We performed  2 tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to assess differences between CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs and others using 2-sided tests with the conventional 95% threshold for statistical significance. We used data visualization techniques to illustrate the number of CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs per 100,000 persons aged 65 or older by health region (known as Local Health Integration Networks [LHINs] in Ontario at the time).37 We used unadjusted logistic regression to examine factors associated with FPs having additional training or focused practices in caring for older adults. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with an increased threshold for relevant fee codes to classify FSP-COE FPs. Cases with missing data were excluded from each analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4.

2 tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to assess differences between CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs and others using 2-sided tests with the conventional 95% threshold for statistical significance. We used data visualization techniques to illustrate the number of CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs per 100,000 persons aged 65 or older by health region (known as Local Health Integration Networks [LHINs] in Ontario at the time).37 We used unadjusted logistic regression to examine factors associated with FPs having additional training or focused practices in caring for older adults. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with an increased threshold for relevant fee codes to classify FSP-COE FPs. Cases with missing data were excluded from each analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4.

Ethics

This project was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (11391). Use of ICES data is authorized under Section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which allows ICES to collect and analyze health care and demographic data without consent for health system evaluation and improvement.38

RESULTS

Cohort creation

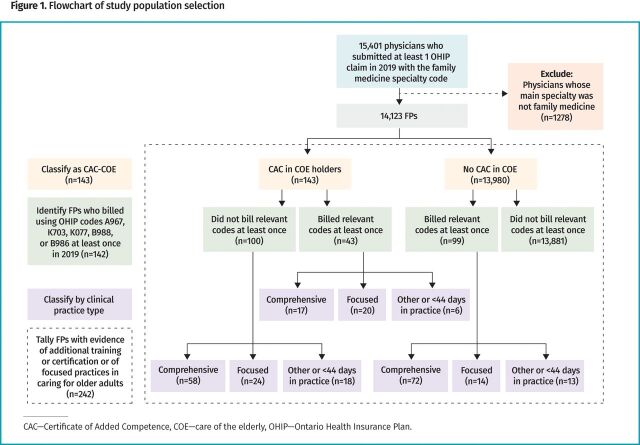

A total of 14,123 FPs satisfied our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). We identified 242 FPs with additional training or focused practices in COE: 100 as CAC-COE only, 99 as FSP-COE only, and 43 who satisfied both the CAC-COE and FSP-COE classifications. That is, of the 143 total CAC-COE FPs, 43 billed using the FSP-COE OHIP fee codes.36

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study population selection

For the purposes of description, we considered the remaining 13,881 FPs as lacking evidence of having additional training in or providing focused care of older adults.

Descriptive findings

Characteristics of FPs with and without additional training or focused practices in the care of older adults in Ontario and characteristics of their practices are summarized in Table 1.36 Family physicians in the CAC-COE or FSP-COE group were more likely to be female than other FPs (59.92% versus 48.66%, respectively; P<.001) and to be younger (median age 45 [IQR=16] versus 49 [IQR=23]; P<.001). Their median time in practice was shorter (17 years [IQR=18] versus 22 years [IQR=24]; P<.001) and they were more likely to be Canadian medical graduates (65.29% versus 54.93%; P=.004).

Table 1.

Characteristics of FPs in Ontario with and without additional training or focused practices in the care of older adults

| CHARACTERISTIC | CAC-COE AND FSP-COE FPs(n=242) | FPs WITHOUT EVIDENCE OF ADDITIONAL TRAINING OR FOCUSED PRACTICES (n=13,881) | P VALUE* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female), n (%) | 145 (59.92) | 6754 (48.66) | <.001* |

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 45 (16) | 49 (23) | <.001* |

| Years in practice, median (IQR) | 17 (18) | 22 (24) | <.001* |

| Based in rural location,† n (%) | 20 (8.26) | 1236 (8.90) | .73 |

| Community size,‡ n (%) | |||

|

90 (37.19) | 6136 (44.20) | .19 |

|

49 (20.25) | 2499 (18.00) | |

|

60 (24.79) | 2802 (20.19) | |

|

23 (9.50) | 1208 (8.70) | |

|

20 (8.26) | 1236 (8.90) | |

| ED in physician’s census subdivision, n (%) | 200 (82.64) | 10,723 (77.25) | .05* |

| Location of medical school training, n (%) | |||

|

158 (65.29) | 7625 (54.93) | .004* |

|

27 (11.16) | 2340 (16.86) | |

|

57 (23.55) | 3916 (28.21) | |

| Community-level marginalization score in primary practice location,§ median (IQR) | |||

|

0.04 (0.22) | 0.02 (0.21) | <.001* |

|

−0.12 (0.19) | −0.12 (0.43) | .45 |

|

−0.16 (0.46) | −0.16 (0.55) | .19 |

|

−0.07 (0.93) | −0.07 (1.22) | <.001* |

| Full-time affiliation with a patient enrolment model, n (%) | 155 (64.05) | 9059 (65.26) | .69 |

| Practice type, n (%) | |||

|

147 (60.74) | 9581 (69.02) | <.001* |

|

58 (23.97) | 2172 (15.65) | |

|

37 (15.29) | 2128 (15.33) | |

| Type of patient enrolment model, n (%) | |||

|

20 (8.26) | 2861 (20.61) | <.001* |

|

43 (17.77) | 2888 (20.81) | |

|

82 (33.88) | 2823 (20.34) | |

|

87 (35.95) | 3957 (28.51) | |

|

10 (4.13) | 1352 (9.74) | |

| More than 50% of payments attributed to fee-for-service, n (%) | 96 (39.67) | 6978 (50.27) | <.001* |

| Total OHIP billings ($), median (IQR)‖ | 160,733 (142,935) | 159,789 (158,491) | .79 |

| Billings attributed to core primary care services, n (%) | |||

|

166 (68.60) | 10,218 (73.61) | .10 |

|

53 (21.90) | 2315 (16.68) | |

|

23 (9.50) | 1348 (9.71) | |

| Number of patient visits, median (IQR) | 2636 (2513) | 3005 (3019) | .06 |

| Number of consultations, median (IQR) | 48 (128.50) | 2 (31) | <.001* |

| Submitted billings for adults aged ≥65 (OHIP billing code), n (%) | |||

|

56 (23.14) | 0 (0) | <.001* |

|

108 (44.63) | 0 (0) | <.001* |

|

23 (9.50) | 0 (0) | <.001* |

|

20 (8.26) | 0 (0) | <.001* |

|

19 (7.85) | 0 (0) | <.001* |

|

121 (50.00) | 3232 (23.28) | <.001* |

|

135 (55.79) | 8364 (60.26) | .16 |

|

141 (58.26) | 5166 (37.22) | <.001* |

|

196 (80.99) | 7757 (55.88) | <.001* |

| Most responsible physician in long-term care, n (%) | 91 (37.60) | 1409 (10.15) | <.001* |

| Number of specialist referrals made, median (IQR) | |||

|

3 (10) | 1 (4) | <.001* |

|

25 (41) | 28 (45) | .23 |

|

6 (11) | 2 (7) | <.001* |

| Patients with a health services encounter, median (IQR) | |||

|

860 (993) | 1273 (1249) | <.001* |

|

323 (285) | 299 (314) | .007* |

|

389 (776) | 704 (979) | <.001* |

|

377.50 (529) | 474 (939) | .002* |

| Average age of patients (y), median (IQR) | |||

|

54 (28) | 44 (14) | <.001* |

|

55 (31) | 44 (13) | <.001* |

| Percentage of patients cared for aged ≥65, median (IQR) | 39 (54) | 23 (19) | <.001* |

CAC-COE—Certificate of Added Competence in care of the elderly, ED—emergency department, FSP-COE—focused scope of practice in care of the elderly, IQR—interquartile range, OHIP—Ontario Health Insurance Plan.

Statistically significant difference.

Defined as <10,000 population in census metropolitan area.

Based on census metropolitan area size.

Based on Ontario Marginalization Index factor score; higher scores imply higher degrees of marginalization.

Gross billing amounts and payments according to the OHIP Schedule of Benefits.36 These amounts may not reflect net payments made or approved by the Ministry of Health.

While most CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs had comprehensive practices, they were less likely than other FPs to have comprehensive practices (60.74% versus 69.02%; P<.001). While the most common patient enrolment model used by CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs and for other FPs was “Other or no enrolment group” (35.95% versus 28.51%, P<.001), CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs were more likely to work under a blended salary model than other FPs (33.88% versus 20.34%; P<.001). Median OHIP gross payments for CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs did not vary significantly compared with those of other FPs ($160,733 [IQR=$142,935] versus $159,789 [IQR=$158,491]; P=.79).

Family physicians with additional training or focused practices in COE tended to have fewer total patient visits, but this difference was not statistically significant (median number of patient visits=2636 [IQR=2513] versus 3005 [IQR=3019]; P=.06). However, they also tended to provide more consultations than other FPs (median=48 [IQR=128.5] versus 2 [IQR=31]; P<.001) and tended to have more encounters with patients aged 65 and older (median=323 [IQR=285] versus 299 [IQR=314); P=.007). A total of 91 CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs (37.60%) practised as MRPs in LTC, a significantly higher proportion than among other FPs (10.15%; P<.001).

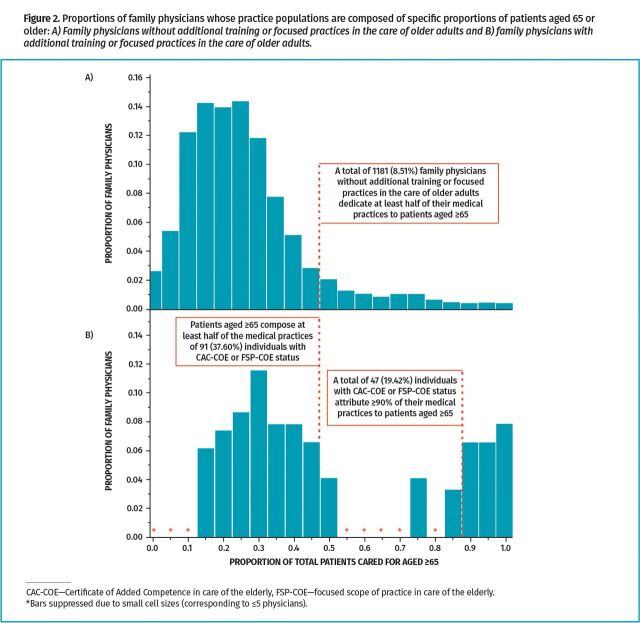

Submitted billings pointed to significant differences between the 2 groups in clinical activities involving patients aged 65 or older, including frequency of house call assessments, completion of home care applications, and completion of LTC health report forms, with CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs being more likely to bill for these activities. The CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs also tended to make significantly more referrals to geriatricians than other FPs made (median=3 [IQR=10] versus 1 [IQR=4]; P<.001) and more referrals to psychiatrists for patients aged 65 or older (median=6 [IQR=11] versus 2 [IQR=7]; P<.001). Patients aged 65 or older tended to compose significantly greater proportions of the medical practices of CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs than of other FPs (median=39% [IQR=54%] versus 23% [IQR=19%]; P<.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportions of family physicians whose practice populations are composed of specific proportions of patients aged 65 or older: A) Family physicians without additional training or focused practices in the care of older adults and B) family physicians with additional training or focused practices in the care of older adults.

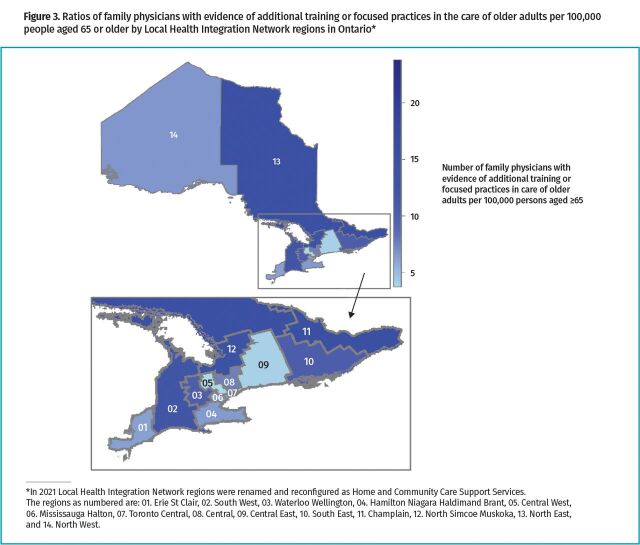

Family physicians in the CAC-COE or FSP-COE group practised primarily in the Champlain, Toronto Central, Central, Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant, and North East LHINs in Ontario. Figure 3 shows the ratio of CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs to older adults in each LHIN region.

Figure 3.

Ratios of family physicians with evidence of additional training or focused practices in the care of older adults per 100,000 people aged 65 or older by Local Health Integration Network regions in Ontario*

Table 2 describes characteristics of CAC-COE FPs. Most held 1 CAC (90.91%). Seventeen (11.89%) CAC-COE individuals were affiliated with the CFPC’s Section of Researchers and 43 (30.07%) were members of the Section of Teachers; these are CFPC committees whose participants provide leadership in these areas.

Table 2.

Characteristics of FPs in Ontario with CACs in COE: N=143.

| CHARACTERISTIC | FPs WITH CACs IN COE, n (%) |

|---|---|

| CACs earned | |

|

143 (100) |

|

7 (4.90) |

|

8 (5.59) |

| Number of CACs held | |

|

130 (90.91) |

|

13 (9.09) |

| Calendar year CAC in COE earned | |

|

55 (38.46) |

|

56 (39.16) |

|

32 (22.38) |

| Section of Researchers† member | 17 (11.89) |

| Section of Teachers† member | 43 (30.07) |

CAC—Certificate of Added Competence, COE—care of the elderly.

Other CAC domains include addiction medicine, emergency medicine, enhanced surgical skills, family practice anesthesia, obstetric surgical skills, and sport and exercise medicine.

Voluntary committee of the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Inferential findings

Table 3 shows the following factors were significantly associated with greater likelihood of being a CAC-COE or FSP-COE FP: physician and community demographic characteristics (ie, female sex, community size, being a Canadian medical graduate, and having higher residential instability at the community level), maintaining a focused practice type, engaging in specific primary care activities (ie, providing higher numbers of consultations; being an MRP in LTC; billing for ≥1 complex house calls, home care applications, or LTC health report forms; and referring patients aged 65 or older to psychiatry and geriatric specialists), and providing care to older patients. Two factors were statistically significantly associated with decreased odds of additional scope in COE: greater number of years in practice and greater community-level ethnic diversity.

Table 3.

Factors associated with FPs in Ontario having additional training or focused practices in the care of older adults

| CHARACTERISTIC | UNADJUSTED ANALYSIS | |

|---|---|---|

| ODDS RATIO (95% CI) | P VALUE | |

| Sex (female) | 1.58 (1.22-2.04) | <.001* |

| Years in practice | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | <.001* |

| Community size† | ||

|

ref | ref |

|

1.34 (0.94-1.90) | .11 |

|

1.46 (1.05-2.03) | .02* |

|

1.30 (0.82-2.06) | .27 |

|

1.10 (0.68-1.80) | .69 |

| Completed medical school training in Canada | 1.80 (1.19-2.71) | .01* |

| Community-level marginalization score in primary practice location‡ | ||

|

1.51 (1.19-1.91) | <.001* |

|

0.74 (0.38-1.45) | .38 |

|

1.41 (0.93-2.14) | .11 |

|

0.69 (0.57-0.85) | <.001* |

| Full-time affiliation with a patient enrolment model | 0.95 (0.73-1.24) | .69 |

| Practice type | ||

|

ref | ref |

|

1.74 (1.28-2.37) | <.001* |

|

1.13 (0.79-1.63) | .50 |

| Visits per 1000 patients | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | .09 |

| Consultations per 1000 patients | 1.82 (1.39-2.38) | <.001* |

| Submitted billings for adults aged ≥65 (OHIP billing code) | ||

|

3.30 (2.55-4.25) | <.001* |

|

0.83 (0.64-1.08) | .16 |

|

2.36 (1.82-3.05) | <.001* |

|

3.36 (2.44-4.64) | <.001* |

| Most responsible physician in long-term care | 5.33 (4.09-6.96) | <.001* |

| Number of specialist referrals made for patients aged ≥65 | ||

|

1.01 (1.00-1.01) | <.001* |

|

1.00 (1.00-1.00) | .02* |

| Patients aged ≥65 with a health services encounter | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | .08 |

| Average age of patients | ||

|

1.07 (1.06-1.08) | <.001* |

|

1.07 (1.06-1.08) | <.001* |

OHIP—Ontario Health Insurance Plan, OR—odds ratio, ref—reference group.

Statistically significant.

Based on census metropolitan area size.

Based on Ontario Marginalization Index factor score.

Sensitivity analysis

A total of 83 FPs billed the FSP-COE fee codes more than once, reducing our CAC-COE or FSP-COE cohort to 186 FPs (Appendix 4, available from CFPlus*). Compared with the main analysis, we observed similarities for most descriptive factors.

DISCUSSION

We established the first working classification of FPs with additional training or focused practices in the care of older adults using health administrative data in Ontario. To date, examining individual and medical practice characteristics of CAC-COE and FSP-COE FPs has been limited to survey methods and environmental scans39-42 or case studies.27

We found these FPs primarily practise in team-based models and in comprehensive practice types, and more than two-thirds attribute more than half of their billings to core primary care services. Therefore, despite having additional training or focused practices, CAC-COE and FSP-COE FPs remain engaged in contributing to comprehensive care. While some FPs deliver skilled care to focused populations of older patients, their practices align with the CFPC’s Triple C Competency-Based Curriculum by maintaining continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated care centred in family medicine.43 This finding aligns with previous studies where CAC-COE FPs credited their CACs with improving patient access to specialized geriatric care, supporting continuity of care as their patients age, and enabling community-adaptive care.27

Our findings support and extend prior work describing FPs with CACs or focused practices. Our cohort classification and examination of remuneration align with prior findings of substantial differences in how CAC-COE FPs are compensated and a lack of financial incentive to pursue focused practice designations.27,44 In previous work examining differences between focused practice physicians (in any clinical domain) and others, relationships with community size of the physician’s practice location and with remuneration models differed substantially.20 Our findings conflict with studies suggesting focused practice FPs and medical directors in LTC are not early-career physicians, as we found FPs with additional scope for older patients tended to be younger and had fewer years in practice.23,32 However, this difference may reflect our reliance on the CAC in COE to determine focused practice. The CAC in COE is most commonly achieved through a full-time postgraduate training year that, while open to all physicians, is typically completed by younger individuals.39

Previous health human resource initiatives found large discrepancies between the limited supply of physicians delivering specialized geriatric services and population-level needs.27,40-42 Given the small number of CAC-COE FPs identified, these findings might be explained by fewer applicants to CAC-COE and geriatric medicine postgraduate training45 and by an increasing number of vacant positions in recent years.46,47 Practice locations that we identified as having a greater supply of CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs affirmed prior work; these health regions have been regarded as being successful in negotiating funding arrangements to attract and retain CAC-COE FPs.42 Further, the frequent engagement of CAC-COE and FSP-COE FPs in consultative work affirms their expertise as skilled resources and reflects their practice in settings where clinical services focused on older adults are delivered (eg, inpatient rehabilitation, memory clinics).48

Given the small number of FPs with additional expertise or focused practices relevant to the needs of older adults, most older persons will receive care from FPs without advanced clinical training in geriatrics.41 As the Canadian population ages, postgraduate training programs could benefit from engaging CAC-COE FPs as leaders to enhance geriatric competencies among all FPs who increasingly deliver care to older populations.

Limitations

Our classification of FPs with additional scope was sensitive but not specific. Although the OHIP Schedule of Benefits and Fees stipulates that only FPs with billing designations are eligible to use focused practice fee codes,36 some may have billed using these codes in error. In the absence of a validated list of FSP-COE FPs, we could not assess the validity of our classification and may have overestimated the workforce, although the sensitivity analysis affirmed our main findings. Our reliance on administrative data (ie, physician fee codes for reimbursement) may not accurately reflect clinical practice.49 Finally, FPs’ practice compositions may be influenced by natural aging or proximity to areas more densely populated by older adults. As such, FPs could provide more care for older adults without identifying as having additional expertise or focused practices.

Conclusion

We established the first working classification to identify FPs with additional scope in the care of older adults within health administrative data in Ontario. Our findings demonstrate substantial practice differences between CAC-COE or FSP-COE FPs and those without evidence of additional training or focused practices. Given the limited numbers of CAC-COE and FSP-COE FPs identified, the contributions of all FPs who care for older adults should be considered in health human resource planning, and efforts to increase interest in enhanced skills training in COE should be emphasized. Our classification should enable future work examining the impact of FP practices on older patients’ outcomes and quality of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The data set used for this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (eg, health care organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at https://www.ices.on.ca/DAS (email das@ices.on.ca). The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification. Parts of this material are based on data or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Ontario Health, and the Ontario Ministry of Health. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. This document used data adapted from the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion File, which is based on data licensed from Canada Post Corporation, or data adapted from the Ontario Ministry of Health Postal Code Conversion File, which contains data copied under licence from Canada Post Corporation and Statistics Canada. We thank the Toronto Community Health Profiles Partnership for providing access to the Ontario Marginalization Index. This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. Dr Rebecca H. Correia was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Graduate Scholarship (funding reference #181540). Dr Meredith Vanstone is supported by a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) in Ethical Complexity in Primary Care. Dr M. Ruth Lavergne is supported by a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) in Primary Care. Dr Andrew P. Costa is supported by a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) in Integrated Care for Seniors. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Appendices 1 to 4 are available from https://www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Contributors

Dr Rebecca H. Correia, Dr Henry Y.H. Siu, Dr Aaron Jones, Dr Meredith Vanstone, Steve Slade, and Dr Andrew P. Costa contributed to the study conception and design. David Kirkwood and Dr Glenda Babe contributed to data set preparation. Dr Rebecca H. Correia, Dr Chris Frank, David Kirkwood, Dr Henry Y.H. Siu, Dr Aaron Jones, Dr Meredith Vanstone, Dr M. Ruth Lavergne, Steve Slade, and Dr Andrew P. Costa contributed to the analysis and interpretation of results. Dr Rebecca H. Correia prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.Lemire F. Addressing family physician shortages. Can Fam Physician 2022;68:392 (Eng), 391 (Fr). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawson E. The global primary care crisis [editorial]. Br J Gen Pract 2023;73(726):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glazier RH. Our role in making the Canadian health care system one of the world’s best. How family medicine and primary care can transform—and bring the rest of the system with us [Commentary]. Can Fam Physician 2023;69:11-6 (Eng), e1-7 (Fr). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiran T. Keeping the front door open: ensuring access to primary care for all in Canada [comment]. CMAJ 2022;194(48):E1655-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiran T, Green ME, Wu CF, Kopp A, Latifovic L, Frymire E, et al. Family physicians stopping practice during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. Ann Fam Med 2022;20(5):460-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal M, Oandasan I, editors. Scope of practice of family physicians in Canada: an Outcomes of Training Project evidence summary. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2022. p. 10. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/Resources/Education/AFM-OTP-Summary7-Scope-of-Practice.pdf. Accessed 2024 Jul 30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.FM/ES data and reports. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2023. Available from: https://www.carms.ca/data-reports/fmes-data-reports. Accessed 2023 Oct 18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirianni G, Xu QYA.. Canada’s crisis of primary care access: Is expanding residency training to 3 years a solution? CMAJ 2023;195(41):E1418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slade S, Shrichand A, Dimillo S.. Health care for an aging population: a study of how physicians care for seniors in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez G, Matchar D, Koh GCH, Tyagi S, van der Kleij RMJJ, Chavannes NH, et al. Revisiting the four core functions (4Cs) of primary care: operational definitions and complexities. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2021;22:e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health and health care for an aging population: policy summary of the Canadian Medical Association. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Medical Association; 2013. Available from: https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/2018-11/CMA_Policy_Health_and_Health_Care_for_an_Aging-Population_PD14-03-e_0.pdf. Accessed 2024 Aug 9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.She Z, Gaglioti AH, Baltrus P, Li C, Moore MA, Immergluck LC, et al. Primary care comprehensiveness and care coordination in robust specialist networks results in lower emergency department utilization: a network analysis of Medicaid physician networks. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11:2150132720924432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee A, Kiyu A, Milman HM, Jimenez J.. Improving health and building human capital through an effective primary care system. J Urban Health 2007;84(Suppl 1):i75-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J.. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83(3):457-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL Jr.. More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med 2015;13(3):206-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sans-Corrales M, Pujol-Ribera E, Gené-Badia J, Pasarín-Rua MI, Iglesias-Pérez B, Casajuana-Brunet J.. Family medicine attributes related to satisfaction, health and costs. Fam Pract 2006;23(3):308-16. Epub 2006 Feb 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weidner AKH, Phillips RL Jr, Fang B, Peterson LE.. Burnout and scope of practice in new family physicians. Ann Fam Med 2018;16(3):200-5. Erratum in: Ann Fam Med 2018;16(4):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Malley AS, Rich EC.. Measuring comprehensiveness of primary care: challenges and opportunities. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(Suppl 3):568-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemire F. Comprehensiveness during and after a pandemic. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:868 (Eng), 867 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marbeen M, Freeman TR, Terry AL.. Focused practice in family medicine. Quantitative study. Can Fam Physician 2022;68:905-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman TR, Boisvert L, Wong E, Wetmore S, Maddocks H.. Comprehensive practice. Normative definition across 3 generations of alumni from a single family practice program, 1985 to 2012. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:750-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weidner AKH, Chen FM.. Changes in preparation and practice patterns among new family physicians. Ann Fam Med 2019;17(1):46-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavergne MR, Rudoler D, Peterson S, Stock D, Taylor C, Wilton AS, et al. Declining comprehensiveness of services delivered by Canadian family physicians is not driven by early-career physicians. Ann Fam Med 2023;21(2):151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan BTB. The declining comprehensiveness of primary care. CMAJ 2002;166(4):429-34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oandasan IF, Archibald D, Authier L, Lawrence K, McEwen LA, Mackay MP, et al. Future practice of comprehensive care. Practice intentions of exiting family medicine residents in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:520-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabir M, Randall E, Mitra G, Lavergne MR, Scott I, Snadden D, et al. Resident and early-career family physicians’ focused practice choices in Canada: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2022;72(718):e334-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correia RH, Grierson L, Allice I, Siu HYH, Baker A, Panday J, et al. The impact of care of the elderly Certificates of Added Competence on family physician practice: results from a pan-Canadian multiple case study. BMC Geriatr 2022;22(1):840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong E, Stewart M.. Predicting the scope of practice of family physicians. Can Fam Physician 2010;56:e219-25. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/56/6/e219.long. Accessed 2024 Aug 9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Judson TJ, Press MJ, Detsky AS.. The decline of comprehensiveness and the path to restoring it [editorial]. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(5):1582-3. Epub 2019 Oct 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(8):573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.About ICES. Our organization. Toronto, ON: ICES. Available from: https://www.ices.on.ca/our-organization. Accessed 2023 Jun 20. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Correia RH, Dash D, Poss JW, Moser A, Katz PR, Costa AP.. Physician practice in Ontario nursing homes: defining physician commitment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2022;23(12):1942-7. Epub 2022 May 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Certificates of Added Competence in family medicine. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/cac. Accessed 2021 Nov 3. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank C, Seguin R.. Care of the elderly training. Implications for family medicine. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:510-1.e1-4. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/55/5/510.full.pdf. Accessed 2024 Aug 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKay M, Lavergne MR, Lea AP, Le M, Grudniewicz A, Blackie D, et al. Government policies targeting primary care physician practice from 1998-2018 in three Canadian provinces: a jurisdictional scan. Health Policy 2022;126(6):565-75. Epub 2022 Mar 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.OHIP schedule of benefits and fees. Toronto, ON: Government of Ontario; 2024. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ohip-schedule-benefits-and-fees. Accessed 2024 Aug 2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapter 3. Section 3.08. LHINs—Local Health Integration Networks. In: Office of the Auditor General of Ontario 2015 annual report. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2015. Available from: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/reports_en/en15/3.08en15.pdf. Accessed 2024 Aug 2. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Personal health information protection act, 2004, S.O. 2004, c. 3, Sched. A. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/04p03. Accessed 2024 Aug 2.

- 39.Elma A, Vanstone M, Allice I, Barber C, Howard M, Mountjoy M, et al. The Certificate of Added Competence credentialling program in family medicine: a descriptive survey of the family physician perspective of enhanced skill practices in Canada. Can Med Educ J 2023;14(5):121-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basu M, Cooper T, Kay K, Hogan DB, Morais JA, Molnar F, et al. Updated inventory and projected requirements for specialist physicians in geriatrics. Can Geriatr J 2021;24(3):200-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hogan DB, Borrie M, Basran JFS, Chung AM, Jarrett PG, Morais JA, et al. Specialist physicians in geriatrics—report of the Canadian Geriatrics Society physician resource work group. Can Geriatr J 2012;15(3):68-79. Epub 2012 Sep 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borrie M, Cooper T, Basu M, Kay K, Prorok JC, Seitz D.. Ontario geriatric specialist physician resources 2018. Can Geriatr J 2020;23(3):219-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tannenbaum D, Kerr J, Konkin J, Organek A, Parsons E, Saucier D, et al. Triple C competency-based curriculum: report of the Working Group on Postgraduate Curriculum Review—part 1. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2011. p. 101. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/Resources/Education/WGCR_TripleC_Report_English_Final_18Mar11.pdf. Accessed 2024 Aug 2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elma A, Vanstone M, Allice I, Barber C, Howard M, Mountjoy M, et al. The Certificate of Added Competence credentialling program in family medicine: a descriptive survey of the family physician perspective of enhanced skill practices in Canada. Can Med Educ J 2023;14(5):121-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Correia RH, Dash D, Hogeveen S, Woo T, Kay K, Costa AP, et al. Applicant and match trends to geriatric-focused postgraduate medical training in Canada: a descriptive analysis. Can J Aging 2023;42(3):396-403. Epub 2023 Apr 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.2022 Family medicine/enhanced skills match (Table 9: positions filled/unfilled by discipline). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2022. Available from: https://www.carms.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2022_fmes9e.pdf. Accessed 2023 Oct 21. [Google Scholar]

- 47.2023 Family medicine/enhanced skills match (Table 9: positions filled/unfilled by discipline). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2023. Available from: https://www.carms.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/fmes9e.pdf. Accessed 2023 Oct 21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kay K. Planning for health services for older adults living with frailty: asset mapping of specialized geriatric services (SGS) in Ontario. Provincial Geriatrics Leadership Ontario; 2019. Available from: https://geriatricsontario.ca/resources/planning-for-older-adults-living-with-frailty-sgs-asset-mapping-report. Accessed 2023 Dec 5. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz A, Halas G, Dillon M, Sloshower J.. Describing the content of primary care: limitations of Canadian billing data. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:7. Epub 2012 Feb 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.