Abstract

We have characterized the functional integrity of seven primary Nef isolates: five from a long-term nonprogressing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individual and one each from two patients with AIDS. One of the seven Nefs was defective for CD4 downregulation, two others were defective for PAK-2 activation, and one Nef was defective for PAK-2 activation and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I downregulation. Five of the Nefs were tested and found to be functional for the enhancement of virus particle infectivity. The structural basis for each of the functional defects has been analyzed by constructing a consensus nef, followed by mutational analysis of the variant amino acid residues. Mutations A29V and F193I were deleterious to CD4 downregulation and PAK-2 activation, respectively, while S189R rendered Nef defective for both MHC class I downregulation and PAK-2 activation. A search of the literature identified HIVs from five patients with Nefs predominantly mutated at F193 and from one patient with Nefs predominantly mutated at A29. A29 is highly conserved in all HIV subtypes except for subtype E. F193 is conserved in subtype B (and possibly in the closely related subtype D), but none of the other HIV group M subtypes. Our results suggest that functional distinctions may exist between HIV subtypes.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Nef has multiple, well-defined functions, including the downregulation of cell surface CD4 (18), downregulation of cell surface major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I (55), the enhancement of viral infectivity (14), and the activation of a 62-kDa protein kinase that has been recently identified as PAK-2 (3, 49). Determining which Nef functions are crucial for high rates of virus replication and pathogenesis in HIV disease will provide new targets for anti-HIV drug development (29).

HIV replicates actively and mutates rapidly; therefore, any mutation that prevents an optimal rate of replication would be rapidly selected against (10, 22, 60). Conversely, some Nef functions may be dispensable after the establishment of infection and of little significance in disease progression. Therefore, finding primary isolate nef genes that are functionally defective suggests that the lost functions may not be required for efficient viral replication in vivo. We have previously characterized a primary isolate of Nef (233 Nef) for CD4 downregulation, PAK-2 activation, and enhancement of infectivity. 233 Nef was found to be deficient in PAK-2 activation (36). Primary isolate nef genes defective in CD4 downregulation have also been reported (40, 42).

To further explore the possibility that some in vitro-defined Nef functions are not required for efficient replication in vivo, we have characterized the functional integrity of five primary isolate Nefs from a long-term nonprogressing HIV-infected individual (patient D [24]). These Nefs exhibit considerable functional diversity despite a high degree of structural similarity. The structural basis for each of the functional defects have been analyzed by constructing a nef gene (D.con) with the consensus sequence of the five primary isolates and by mutational analysis of the variant amino acid residues. The structural basis for the PAK-2 activation defect of 233 Nef has also been determined. A literature search based on our results support the conclusion that PAK-2 activation may be a less-conserved function of Nef than CD4 and MHC class I downregulation and infectivity enhancement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary Nef isolates.

Of 16 clones (AAA63812-AAA63827) encoding intact nef genes derived from patient D (24), 5 were adapted by PCR to have EcoRI ends. DNA sequencing of the PCR constructs revealed no changes in the derived amino acid sequences and the GenBank sequences except that amino acids 26 and 27 encoded by the D90-7 nef are EP and not DA (AAA63827). Since all of the other 15 clones are E26-P27 the D90-7 nef PCR clone was used in these studies. The D.con nef was constructed as a combination of D85-11E160A nef and D88-11 nef (Fig. 1). The five primary isolate nef clones contain a second XhoI site 5′ to the site in SF2 nef. This second site was mutated in D.con nef.

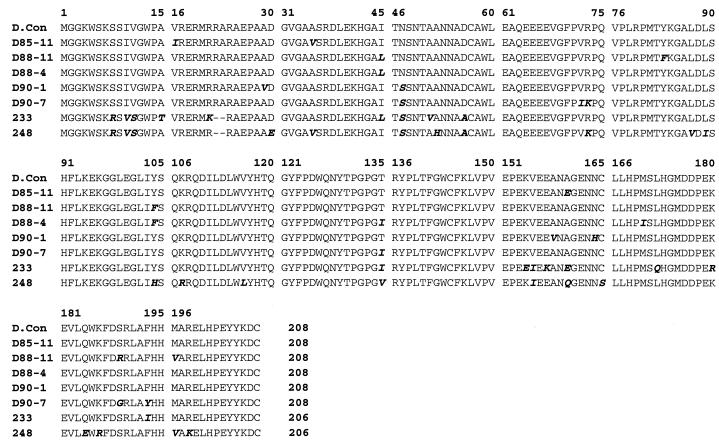

FIG. 1.

Five sequences of primary isolate nef genes derived from a single patient are aligned under their consensus sequence. Deviations from the consensus sequence are in boldface type. Differences between GenBank sequences of these nef genes and Fig. 3 of reference 24 have been corrected. One correction in the GenBank sequence has also been made (see Materials and Methods). Sequences from primary isolate nef genes from two different AIDS patients (233 and 248) are also included (56).

Plasmid expression constructs and transfections.

nef isolates were cloned into the retrovirus vector pLXSN as previously described (18). Plasmids were cotransfected into 293T cells by the calcium phosphate method (8) to transiently generate amphotropic vectors as previously described (36). At 36 to 48 h after transfection, vector-containing media were collected for transduction of CEM and HuT78 human T cells, and then transfected cells were harvested to test for Nef expression by Western blot and in vitro kinase assays.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Desired alterations in nef sequences were made by use of the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. All modified clones were sequenced and cloned into pLXSN (18).

Cell lines and culture conditions.

Human CEM and HuT78 T-cells were transduced to express only the neomycin phosphotransferase gene (neo) or else nef and the neo resistance gene as described previously (18). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), 50 IU of penicillin per ml, 50 μg of streptomycin per ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. Transduced cells were selected by the addition of 1.5 mg of G418 per ml to the culture medium. 293T and HeLa-MAGI cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 IU of penicillin per ml, 50 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine. Cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Western blot analysis.

Nef expression was determined with sheep polyclonal anti-SF2 Nef serum (1:4,000 dilution), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-sheep immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1:20,000; Chemicon International). HRP conjugates were visualized by using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham).

Flow cytometry analysis.

For analysis of cell surface CD4 and MHC class I levels, transduced CEM cells (5 × 105) were first incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-haplotype A1, A11, and A26 MHC class I antibody (One Lambda) for 20 min on ice, and then the cells were washed twice in 2 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% calf serum and 0.1% NaN3. Cells were then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled rabbit anti-mouse IgG for 20 min on ice. Cells were washed as indicated above, incubated for 20 min on ice with 2 μg of unfractionated mouse IgG, and washed again. Cells were then incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibody to human CD4 (Exalpha) and incubated for 20 min on ice. Stained cells were washed as indicated above and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan instrument equipped with LYSYS II software. All fluorescence data were collected in log mode. CEM cells transduced with LXSN served as positive and negative controls. In the latter case isotype control antibody replaced anti-MHC class I, and PE-conjugated mouse IgG1 (Exalpha) replaced PE-conjugated anti-CD4. The flow cytometry data presented below Fig. (See 2 and 4) was collected as part of the same experiment.

In vitro kinase assay.

The NAK assay was performed as previously described (52) except that a 1 M MgCl2 wash prior to autophosphorylation was included. Immunoprecipitations were performed using the sheep anti-SF2 Nef serum. After the kinase assay, reactions were stopped by the addition EDTA to a final concentration of 33 mM. Proteins were eluted from the beads by the addition of 1.5× Laemmli protein loading buffer, denatured at 96°C for 5 min, and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Dried gels were then exposed to a phosphorimager screen (Packard).

Provirus plasmid construction.

To generate SF2 proviruses with chimeric nef genes, the XhoI-BspEI fragment from the SF2 provirus clone p9B18 encoding amino acids 39 to 204 of Nef was replaced by the corresponding fragment from the primary isolates clones by triple ligation (36). In all cases the corresponding chimera was confirmed by DNA restriction analysis.

Production of HIV-1SF2 and chimeric viruses.

Infectious HIV-1SF2 and chimeras were prepared in 293T cells (106) transfected with p9B18 or its chimeric derivatives (3 μg), using either Lipofectamine (Life Technologies)-mediated transfection according to the manufacturer's instructions or calcium phosphate coprecipitation (8). Virus was harvested 48 h posttransfection, filtered through a 0.45-μm (pore-size) filter, and stored frozen in aliquots at −70°C. Lysates from the transfected cells were used for analysis of Nef expression by Western blot analysis (10% of total lysate) and for PAK-2 activity by in vitro kinase assay (90% of total cell lysate).

Infectivity assay.

HeLa-MAGI cells (6 × 104) were plated in 12-well plates and infected 24 h later in triplicate with 5 ng of p24 of wild-type viruses containing Nef chimeras in 400 μl of cell culture medium containing 20 μg of DEAE-Dextran (Sigma) per ml at 37°C in an incubator with 5% CO2. At 2 h after inoculation, 1.6 ml of culture medium was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 36 h. The cells were then fixed and stained as described previously (36). Blue cells were counted as an indicator of infected cells.

Metabolic labeling and pulse-chase experiments.

Hut78/LN cells and Hut78/LnefSN cells expressing either SF2 Nef, SF2R109L/R110L Nef, SIVmac239 Nef, or SIVmac239R137L/R138L Nef were starved for 30 min in methionine- and cysteine-free RPMI 1640 (ICN) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 IU of penicillin per ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin per ml. Cells were metabolically labeled for 45 min at 37°C in the same medium containing 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum and 100 μCi of Tran35S-label (ICN) per 3 × 106 cells. After the labeling, the cells were washed, resuspended in RPMI complete medium, and chased at 37°C. Cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and disrupted in 1 ml of Lysis Buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.15 M NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 10 min on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were incubated with rabbit anti-Nef serum for 60 min at 4°C. For immunoadsorption, 40 μl of settled protein A beads was added, and samples incubated for 60 min at 4°C with rotation. The immunoprecipitates were washed four times with ice-cold Lysis Buffer containing 0.2% SDS, solubilized with 40 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer (5 min at 95°C), electrophoresed on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, dried, and exposed to X-ray film.

RESULTS

The sequences of five primary isolates of the nef gene from a single patient (designated D [24]) are presented relative to their consensus sequence (Fig. 1). There were a total of 17 clones representing 16 intact sequences isolated from this patient over a span of 5 years. The patient was a long-term nonprogressor. In previous work the D85-11 nef clone and single clones isolated from nine other long-term nonprogressors were tested for their ability to enhance HIV infectivity by Huang et al. (25). All 10 of these Nefs enhanced HIV infectivity. We have confirmed and extended these results and found that the D85-11, D88-11, D90-1, and D90-7 Nefs all enhanced HIV infectivity by a single-round infection assay (not shown). We have previously demonstrated that 233 Nef enhances HIV infectivity (36). Therefore, of the 14 primary isolate nef genes tested from 10 HIV nonprogressors and 1 progressor, all have been found to be functional for this activity.

The five nef genes from patient D encode very similar amino acid sequences despite the 5-year span between the isolations. Only 2% of the amino acid residues (22 of 1,040) are not identical to the consensus sequence. Also shown are the sequences of the 233 nef and the 248 nef from two AIDS patients (56). We constructed a pLXSN expression vector encoding a protein with the consensus sequence (see Materials and Methods). This protein was designated D.con Nef to distinguish it from a previously reported consensus nef (56).

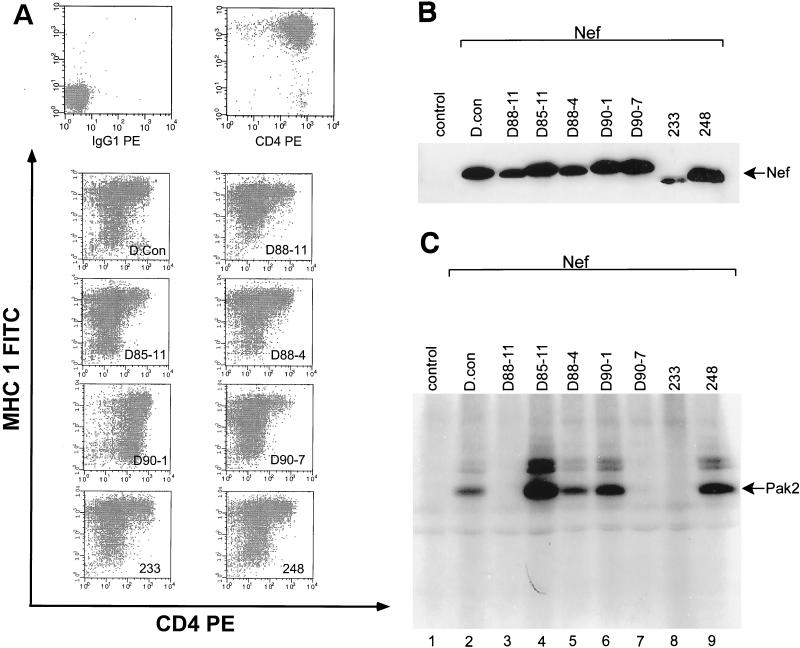

The ability of each of the eight Nefs to downregulate CD4 and MHC class I (Fig. 2A), and activate PAK-2 (Fig. 2C) was determined. The D.con, D85-11, D88-4, and 248 Nefs were functional for all three Nef phenotypes. The more widely studied SF2 Nef is also functional for these three phenotypes (reference 36 and data not shown). D90-1 Nef failed to downregulate CD4, while D88-11 Nef was defective in MHC class I downregulation (45% of D.con Nef and 36% of D90-1). Three Nefs (D88-11, D90-7, and 233) failed to activate PAK-2. The SF2 Nef (not shown) and all primary isolate Nefs except 233 Nef were expressed at near the level of D.con Nef (Fig. 2B). Thus, the seven primary isolate Nefs exhibited considerable functional diversity, particularly in the activation of PAK-2.

FIG. 2.

Seven primary isolate nef genes and D. con nef were stably expressed in CEM cells. The function of these Nefs in CD4 and MHC class I downregulation and activation of PAK-2 was determined. The level of expression for each Nef was determined by Western blot analysis. (A) Two-color analysis for CD4 (PE) and MHC class I (FITC) cell surface expression in transduced CEM cells was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. (Top left) CEM LXSN cells (negative control). (Top right) CEM LXSN cells (positive control). (B) Western blot analysis of Nef expression in extracts from transduced CEM cells. Control, CEM LXSN cell extracts. (C) Activation of p21-activated protein kinase-2 (Pak2) by Nef was assayed with extracts from transduced CEM cells. Control, CEM LXSN cell extracts. We have reported 233 Nef to be expressed at near the same level as SF2 Nef with a rabbit anti-Nef serum (36). The apparent reduced expression of 233 Nef in Fig. 2B seems to result from a reduced immunoreactivity of 233 Nef to the sheep anti-SF2 Nef serum used for these studies. A similar observation was made for NefEE155QQ in reference 2.

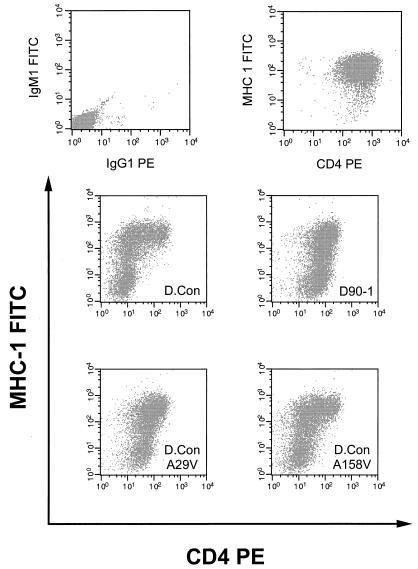

These data suggest that each of the four Nef functions studied are genetically separable. To simplify the analysis, we determined the minimal amino acid differences that can account for each of the defects observed. First, each of the four variant amino acids in D90-1 Nef was singly incorporated into D.con Nef (Fig. 1). The N47S and N164H mutations had no effect on D.con Nef expression or function (not shown). D.conA29V Nef exhibited a clearly diminished ability to downregulate CD4, while a smaller defect was observed for D.conA158V Nef (Fig. 3). MHC class I downregulation (Fig. 3), PAK-2 activation (not shown), and protein expression (not shown) were not affected by these mutations. Thus, the defect in CD4 downregulation by D90-1 Nef is mostly accounted for by A29V.

FIG. 3.

The effect of D90-1 derived mutations, A29V and A158V, on D.con Nef function in CEM cells was determined. Two-color analysis for CD4 (PE) and MHC class I (FITC) cell surface expression in transduced CEM cells was determined by FACS. (Top left) CEM LXSN cells (negative control). (Top right) CEM LXSN cells (positive control).

CD4 downregulation has been previously reported to be lost when back-to-back acidic residues (DD or ED) near the C terminus are mutated to alanine (2, 27). Mangasarian et al. (39) also reported a 75% diminution of MHC class I downregulation by this mutation, in contrast to Greenberg et al. (19), who found no effect. To assess the discrepancy in the literature, we constructed the SF2E178A/D179A nef. This mutant Nef was stable, downregulated MHC class I, activated PAK-2, but failed to downregulate CD4 (not shown). Therefore, our data support the conclusions of lafrate et al. (27) that the N-terminal and C-terminal flexible segments of Nef each contain a functional domain that can be mutated specifically to knock out the Nef's CD4 downregulation function.

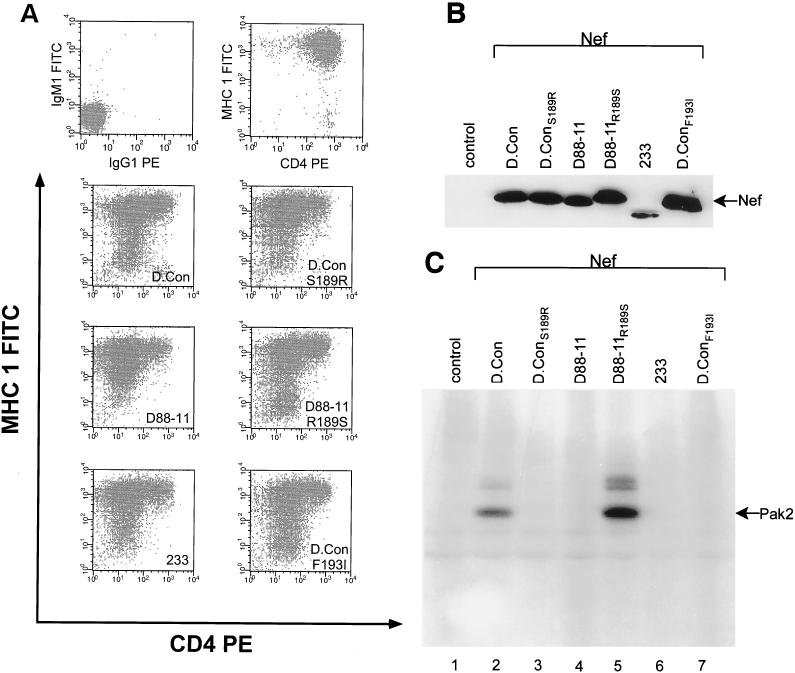

233 Nef, D88-11 Nef, and D90-7 Nef all failed to bind PAK-2. Domain swaps demonstrated that all three defects resided in the C-terminal third of the protein (not shown). In addition, the SF2K156E/E159K nef was constructed in an attempt to discover the defect in 233 Nef (these positions correspond to positions 152 and 155 in 233 Nef). This mutant was found to be fully stable, activate PAK-2, and downregulate CD4 and MHC class I (not shown). Next, we made D.conF193I nef and D.conS189R nef. Both of these constructs failed to activate PAK-2 (Fig. 4C) and accounted for the kinase defects in 233 Nef and D88-11 Nef. Unlike 233 Nef, D.conF193I Nef was expressed at the same level as D.con Nef, demonstrating that the F193I mutation specifically knocks out PAK-2 activation (Fig. 4C). Since the PAK-2 activation defect in D90-7 Nef has been localized to the final third of the protein, G189 and/or Y193 account for D90-7 Nef's kinase defect (Fig. 1). We further determined that D.conS189A Nef fully activates PAK-2 and downregulates CD4 and MHC class I (not shown and reference 61), which suggests that Y193 is responsible for the defect. Nef from the brain isolate, JR-CSF, also fails to activate PAK-2 (not shown). This Nef has leucine (L211) instead of F193 (33).

FIG. 4.

The effects of mutations of S189R and F193I on D.con Nef function and R189S on D88-11 Nef function in CEM cells were determined. (A) Two-color analysis for CD4 (PE) and MHC class I (FITC) cell surface expression in transduced CEM cells was determined by FACS. (Top left) CEM LXSN cells (negative control). (Top right) CEM LXSN cells (positive control). (B) Western blot analysis of Nef expression in extracts from transduced CEM cells. Control, CEM LXSN cell extracts. (C) Activation of p21-activated protein kinase-2 (Pak2) by Nef was assayed with extracts from transduced CEM cells. Control, CEM LXSN cell extracts.

The ability of D.conF193I Nef to strongly downregulate MHC class I (Fig. 4A) (140% of D.con Nef) would seem to preclude a direct dependence of this function on PAK-2 activation. On the other hand, D.con S189R Nef was found to downregulate CD4 but was less effective in MHC class I downregulation (60% of D.con) (Fig. 4A). The reverse mutation, D88-11R189S Nef, was made, and this change restored the ability of D88-11 Nef to activate PAK-2 (Fig. 4C) and to downregulate MHC class I (Fig. 4A)(112% of D.con Nef). The dual phenotype of R189S may result from interaction of this mutation with other variant residues in D88-11 Nef. We tested the D88-11F83Y and D88-11F104Y Nefs and found no restoration of PAK-2 activation or MHC class I phenotypes (not shown). Therefore, we consider that the likely explanation for the multiply defective phenotype of R189 is the drastic structural change that results from substituting R for S. This conclusion is supported by the observation that D.conS189A Nef is fully functional.

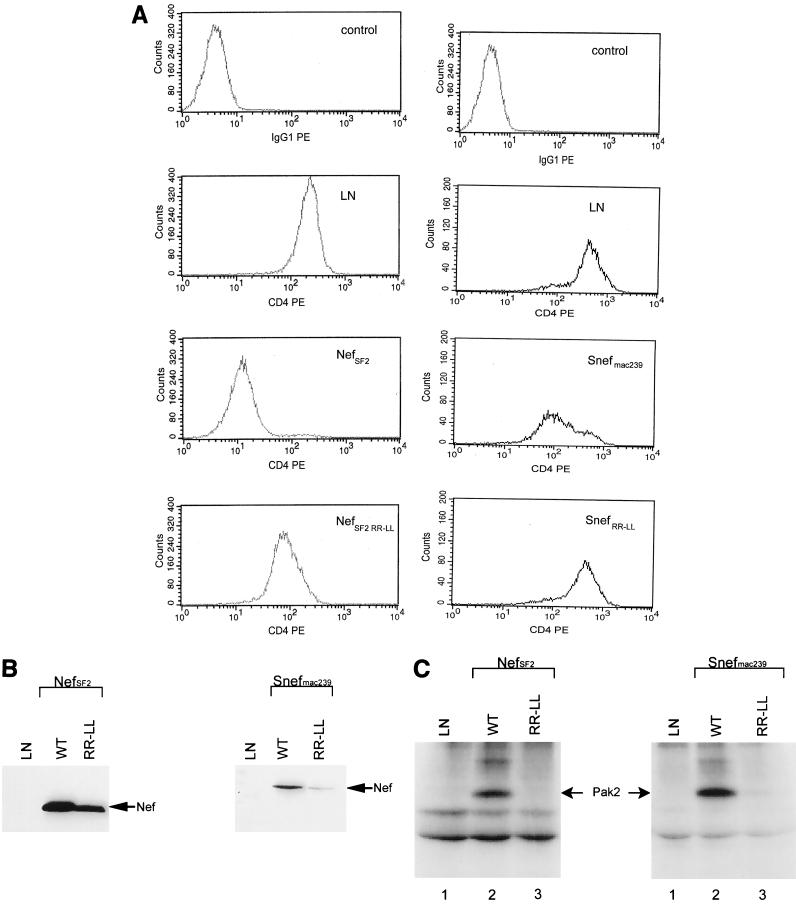

We were interested in comparing our PAK-2 activation mutants with the previously reported RRLL mutant that has been used for macaque studies (53). First, we constructed the SF2R109L/R110L nef mutant. We found this mutant to be defective for PAK-2 activation (Fig. 5C, left) and, as previously reported for NL4-3R105L/R106L Nef (23), for CD4 downregulation (Fig. 5A, left). Western blot analysis also revealed this mutant to be expressed at lower levels than was the wild type (Fig. 5B, left). The simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) version of this mutation (SIVmac239R137L/R138L Nef) was then made because it has been reported to be stable (53), although SIVmac239R137A/R138A Nef was reported to be unstable (27). We found SIVmac239R137L/R138L Nef to lack CD4 downregulation and PAK-2 activation functions and, like SF2R109L/R110L Nef, to be weakly expressed (Fig. 5). Consistent with the Western blot results, both RRLL mutants exhibited greatly reduced stability in pulse-chase experiments. SIVmac239R137L/R138L Nef was found to have a half-life of less than 1 h (not shown). Therefore, we conclude that this mutant is not useful as a specific mutation for PAK-2 activation because it is multiply defective and unstable relative to the parent Nefs, SF2 and SIVmac239.

FIG. 5.

The effects of R109L/R110L on the function of SF2 Nef and of R137L/R138L on the function of SIVmac239 Nef in transduced HuT78 cells were determined. (A) Downregulation of CD4 was determined by FACS: left side, negative and positive controls (LN), SF2 Nef (NefSF2), and SF2R109L/R110L Nef (NefSF2 RR-LL); right side, negative and positive control (LN), SIVmac239 Nef (Snefmac239), and SIVmac239R137L/R138L Nef (SnefRR-LL). (B) Western blot analysis of Nef expression: left, negative control (LN), SF2 Nef (WT), and SF2R109L/R110L Nef (RR-LL); right, negative control (LN), SIVmac239 Nef (WT), and SIVmac239R137L/R138L Nef (RR-LL). (C) Activation of p21-activated protein kinase-2 (Pak2). Left, SF2 Nef (WT) and SF2R109L/R110L Nef (RR-LL); right, SIVmac239 Nef (WT) and SIVmac239R137L/R138L Nef (RR-LL).

DISCUSSION

In the late 1980s initial reports described four functions for Nef. Nef reduced viral infectivity (58), exhibited GTP-dependent autophosphorylation (20), was phosphorylated on threonine 15 by protein kinase C (20), and downregulated CD4 (20). Subsequently, it was shown that Nef enhances viral infectivity (14), that it does not bind GTP (21), and that threonine 15 was not conserved and Nefs with alanine 15 were fully functional (63). Only CD4 downregulation remains as a function of Nef and that was questioned at the time (9). In the last 10 years there has been an dramatic increase in the number of putative Nef functions (50). As occurred previously, confusing and conflicting results have been reported. For example, cells in which CD4 has been downregulated by Nef have been reported to have reduced CD4 flux to the cell membrane (38) and to accelerate CD4 endocytosis (1). Not only are these two scenarios in stoichiometric conflict with each other, they also conflict with clear evidence that CD4 flux to the cell membrane is unaltered by Nef (51). Quantitative data on CD4 flux will be required to resolve the mechanism of CD4 downregulation. In addition, it has been suggested that it is critical for Nef to bind to β-COP at a highly conserved diacidic peptide: EE155 (44). We (and others [40, 48]) have shown that this proposed interaction is not critical since both 233 Nef and SF2K156E/E159K Nef have K instead of the second E. It should also be noted that the EE155 motif is only modestly conserved (See below.).

Other conflicts include the fact that NAK activation has been reported to be required for infectivity enhancement by Nef (61) or that it is unnecessary for this function (36). The significance of the reported interactions of Nef with PAK-1 (15), hck (16), NBP-1 (35), and thioesterase (34) has also been questioned (3, 7, 44, 45). Finally, we also found here that the RRLL mutation on which the in vivo significance of PAK-2 activation is based (53) is multiply defective and unstable.

Establishing which functions of Nef are valid is an enormous task facing those working in the Nef field. Renkema and Saksela (50) suggest that determining the host proteins that interact with Nef is crucial, and they list 19 proteins reported to bind to Nef. (In fact, there are more than 20. See references 4, 15, 28, 46, and 47.) According to Renkema and Saksela, the list is excessive and continues to grow. Their view is difficult to dispute given the fact Nef is only 206 amino acids long. Nonetheless, we feel that Nef multifunctionality is a highly significant feature of HIV replication. Tat and Rev establish the early and late periods of virus transcription by turning a weak promoter producing multiply spliced mRNAs into a strong promoter producing large amounts of unspliced and once-spliced mRNAs. This gives the virus time to optimize the host cell environment for the massive viral particle synthesis that occurs during the late period. As the only other protein expressed during the early period, Nef is responsible for this optimization. An instructive analogy is that of the T-antigens, which alter the cellular environment prior to active virus particle production. Although the T-antigens are more complex and larger than Nef (simian virus 40 T-antigens are 708, 174, and 135 amino acids long) and, by analogy, perform Tat and Rev functions as well, it is interesting to note that there are 25 cellular proteins reported to bind large and middle T-antigens (6).

Nef's crucial role in HIV replication makes it an appealing target for therapeutic intervention in HIV disease. Before this can be achieved it will be important to delimit possible Nef functions by gaining a better understanding of Nef's role in pathogenesis. One major approach has been to investigate the role of Nef in simian AIDS (50). The major advantage of this approach is the ability to induce disease with molecular clones of SIV. The major disadvantage is the fact that HIV and SIV Nefs are not functionally equivalent (50). This lack of functional equivalence has significant implications for the study of Nef function in simian AIDS. Mutations introduced into SIV Nef based on studies of HIV Nef must be shown to inactivate the same function in both Nefs. Protein stability must not be in the least compromised or reversion of the mutation is going to occur in order to establish Nef function in general and not to restore a specific function disrupted by the mutation (12, 30). This is a major problem for the initial characterization of Nef mutations. For example, in a series of 24 alanine scanning mutations, more than half of the mutants were clearly less stable than the parent Nef (2). While primary isolates seem to be much more stable than induced mutations (9 of 10 primary isolate Nefs we have expressed were stable [data not shown]), stability remains an important consideration. It is also important that an inactivating mutation affects only one function of Nef. For these reasons the reversion of the RRLL mutation cannot be interpreted as establishing the significance of PAK-2 activation in pathogenesis (53). From our results, we conclude that E178A/D179A, F193I, and A29V mutations could be good candidates for investigating Nef function in SIV or SHIV AIDS (32, 37). S189R, which affects both PAK-2 and MHC class I downregulation, is not.

A second complementary approach to understanding the role of Nef in AIDS involves obtaining primary isolate nef clones by PCR of peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) DNA from progressing and nonprogressing patients (5, 24, 31, 41, 42, 48). Approximately 90% of the Nef clones are found to encode intact and apparently functional Nefs (31). Further, many of the nonfunctional nefs may come from PBMCs infected by defective virus that are long-lived and accumulate (54). Cells infected by functional virus are rapidly killed (22, 60). To determine which Nef functions are highly conserved, we looked for the stable mutations that we have characterized in this study (Table 1) in the sequences of 1,167 intact subtype B nef clones. Since it is not always evident if sequences present in the GenBank are from primary isolates, we have included all of the nef genes that we could find.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Nef point mutations and their associated phenotypesa

| Mutation | Lost function |

|---|---|

| A29V | CD4 downregulation |

| E156K/E159K | None |

| E178A/D179A | CD4 downregulation |

| S189R | MHC class I downregulation PAK-2 activation |

| F193I | PAK-2 activation |

The phenotypes of five Nef mutations that maintain protein stability are listed. The numbering of homologous amino acid residues varies between Nefs. The standard length of the Nef is 206 amino acids. 233 Nef, 248 Nef, and NL4-3 Nef are each 206 amino acids long. The five primary isolates from patient D are 208 amino acids long, because amino acids 22 and 23 are duplicated (Fig. 1). SF2 Nef is 210 amino acids long because amino acids 21 to 24 are duplicated.

In our sample of 1,167 nef genes there were only 14 mutations of A29 (6V, 3P, 2R, 2T, and one small deletion), which suggests an important role for CD4 downregulation in HIV infection and AIDS. (The expected number of errors for a single amino acid residue in 1,167 nef genes that result from Taq polymerase misincorporation is one or two [13]). Since A29V only affects CD4 downregulation, leaving MHC class I, PAK-2 activation, and infectivity enhancement intact, the conservation of A29 likely reflects the importance of CD4 downregulation for efficient viral replication. We found, consistent with this observation, only 34 mutations of (E/D)D177. Michael et al. (42) have reported, in apparent conflict with our results, a large number of CD4 downregulation-defective primary isolate nef genes. The mutations responsible for these defective nef genes were not characterized, making it difficult to compare their results to ours. Other reports are more consistent with our results that CD4 downregulation is conserved in primary isolate nef genes (40, 48).

There are two exceptions to the conservation of A29. One is the nef clones from patient D. Although none of the 10 intact nef clones obtained in 1985 and 1988 contain A29V, 5 of 6 clones from 1990 (D90-7 nef is the single A29) had the A29V mutation (24). This suggests that in long-term infections CD4 downregulation can (in rare cases) have diminished significance. The other exception is HIV subtype E in which T29 predominates.

If our analysis is correct that functional significance of a specific residue in Nef corresponds to the infrequent mutation of that residue, then we would expect the E155K mutation to be much more common than mutations to A29 and (E/D)D177 (note that EE155 motif is EE159 in SF2 Nef, EK155 in 233 Nef, and EE157 in D.con Nef). This is in fact the case since there are 231 mutations of the EE155 motif (204 are E155K). We also considered the possibility that the ability of 233 Nef to downregulate CD4 may depend on EE152 (see Fig. 1) acting as an alternative diglutamate motif. This potential alternative to the proposed diglutamate motif of Piguet et al. (44) is found in 78 of the 231 mutations of EE155, leaving 153 Nefs devoid of any possible diglutamate motif.

There are 71 mutations of F193 in our collection of 1,167 nef sequences. These are 31L, 13Y, 11V, 9R, 4I, 1H, 1S, and 1C. Our data suggest most of these would be defective for PAK-2 activation, but not other Nef functions. Interestingly, 32 of the 71 mutations of F193 are derived from only five patients (two progressors, one slow progressor, and two nonprogressors), where the mutant nef genes predominate over nonmutant nef genes (5, 41, 42). In these fives cases it appears likely that PAK-2 activation is not required HIV replication.

The few instances in which CD4 downregulation or PAK-2 activation may have been lost during HIV infection could have resulted from the necessity to escape cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) targeting of Nef (62). Since Nef is the largest and most abundant early protein, it is possible that avoiding CTL targeting of Nef may outweigh maintaining CD4 downregulation or PAK-2 activation in isolated cases. On the other hand, we have not found mutations where infectivity enhancement or MHC class I downregulation have been specifically lost. The multiply defective S189R mutation is rare, occurring only four times in 1,167 Nefs. There are 18 other mutations of S189 (10G, 4N, 3T, and 1C). Whether any of these affect MHC class I downregulation or PAK-2 activation is an open question, given the lack of an effect observed for S189A. We suspect our inability to find mutations that are specifically defective in MHC class I downregulation and infectivity enhancement reflects the importance of these functions to HIV replication efficiency. Clearly, more data is needed before drawing definite conclusions.

The conservation of F193 in subtype B Nefs is not found in non-B subtypes. We have inspected the relatively few non-B nef sequences from the Los Alamos HIV database (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov) and found the amino acids at the positions corresponding to F193 to be as follows: subtype A, 10L, 3R, and 1F; subtype C, 27R, 19H, 5L, and 1Y; subtype D, 5F and 1L; subtype E, 48R; subtype F, 5L and 2F; subtype G, 8R; subtype H, 4F, 2L, and 1R; subtype J, 2R; and subtype K, 3R. We have also looked at the four nef genes most closely related to the major group of HIV to determine the ancestral situation with respect to F193. These nef genes are: chimpanzeeCAM3-L, chimpanzeeUS-R, chimpanzeeGabon1-L, and group N-R (11, 17, 26, 57).

Though less highly conserved than A29 and (E/D)D179, it is evident that F193 is important for subtype B virus (and likely subtype D) and that the prevalence of F193 in subtype B arose after the virus was established in human populations (64). The significance of F193 (and Pak-2 activation) to subtype B virus pathogenesis remains to be determined, but it seems to be indicated by its maintenance after infection of macaques (32, 37) and a chimpanzee that progressed to AIDS (43, 59). The striking contrast between subtypes B, C, and E for F193 and between subtype E and all other group M subtypes for A29 indicates an additional level of complexity in Nef functions. The functional consequences of structural differences exhibited by nef genes of the various HIV subtypes must be investigated before the role of the nef gene in AIDS can be fully evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jay Evans for sharing his expertise for the flow cytometry experiments and Danielle Todd, Preston Rodgers, and Robyn Livingston for technical assistance. We thank R. Koup, R. Gaynor, and D. Foster for continued support for this work.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI33331 and GM60805 (J.V.G.) and AI40387, AI41534, and AI42848 (D.D.H.). V.K.A. was supported in part by training grant CA 09082.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiken C, Konner J, Landau N R, Lenburg M E, Trono D. Nef induces CD4 endocytosis: requirement for a critical dileucine motif in the membrane-proximal CD4 cytoplasmic domain. Cell. 1994;76:853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken C, Krause L, Chen Y-L, Trono D. Mutational analysis of HIV-1 Nef: identification of two mutants that are temperature-sensitive for CD4 downregulation. Virology. 1996;217:293–300. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora V K, Molina R P, Foster J L, Blakemore J L, Chernoff J, Fredericksen B L, Garcia J V. Lentivirus Nef specifically activates Pak2. J Virol. 2000;74:11081–11087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11081-11087.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baur A S, Sass G, Laffert B, Willbold D, Cheng-Mayer C, Peterlin B M. The N-terminus of Nef from HIV-1/SIV associates with a protein complex containing Lck and a serine kinase. Immunity. 1997;6:283–291. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brambilla A, Turchetto L, Gatti A, Bovolenta C, Veglia F, Santagostino E, Gringeri A, Clementi M, Poli G, Bagnarelli P, Vicenzi E. Defective nefalleles in a cohort of hemophiliacs with progressing and nonprogressing HIV-1 infection. Virology. 1999;259:349–368. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodsky J L, Pipas J M. Polyomavirus T antigens: molecular chaperones for multiprotein complexes. J Virol. 1998;72:5329–5334. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5329-5334.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown A, Wang X, Sawai E, Cheng-Mayer C. Activation of the PAK-related kinase by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef in primary human peripheral blood lymphocytes and macrophages leads to phosphorylation of a PIX-p95 complex. J Virol. 1999;73:9899–9907. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9899-9907.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng-Mayer C, Iannello P, Shaw K, Luciw P A, Levy J A. Differential effects of nefon HIV replication: implications for viral pathogenesis in the host. Science. 1989;246:1629–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.2531920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffin J M. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbet S, Muller-Trutwin M C, Versmisse P, Delarue S, Ayouba A, Lewis J, Brunak S, Martin P, Brun-Vezinet F, Simon F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Mauclere P. envsequences of simian immunodeficiency viruses from chimpanzees in Cameroon are strongly related to those of human immunodeficiency virus group N from the same geographic area. J Virol. 2000;74:529–534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.529-534.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig H M, Pandori M W, Riggs N L, Richman D D, Guatelli J C. Analysis of the SH3-binding region of HIV-1 Nef: partial functional defects introduced by mutations in the polyproline helix and the hydrophobic pocket. Virology. 1999;262:55–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delassus S, Cheynier R, Wain-Hobson S. Evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nefand long terminal repeat sequences over 4 years in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1991;65:225–231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.225-231.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Ronde A, Klaver B, Keulen W, Smit L, Goudsmit J. Natural HIV-1 NEF accelerates virus replication in primary human lymphocytes. Virology. 1992;188:391–395. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90772-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fackler O T, Lu X, Frost J A, Geyer M, Jiang B, Luo W, Abo A, Alberts A S, Peterlin B M. p21-activated kinase 1 plays a critical role in cellular activation by Nef. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2619–2627. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2619-2627.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foti M, Cartier L, Piguet V, Lew D P, Carpentier J-L, Trono D, Krause K-H. The HIV Nef protein alters Ca2+signaling in myelomonocytic cells through SH3-mediated protein-protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34765–34772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson D L, Chen Y, Rodenburg C M, Michael S F, Cummins L B, Arthur L O, Peeters M, Shaw G M, Sharp P M, Hahn B H. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature. 1999;397:436–441. doi: 10.1038/17130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia J V, Miller A D. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature. 1991;350:508–511. doi: 10.1038/350508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg M E, Iafrate A J, Skowronski J. The SH3 domain-binding surface and an acidic motif in HIV-1 Nef regulate trafficking of class I MHC complexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2777–2789. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy B, Kieny M P, Riviere Y, Le Peuch C, Dott K, Girard M, Montagnier L, LeCocq J-P. HIV F/3′ orfencodes a phosphorylated GTP-binding protein resembling an oncogene product. Nature. 1987;330:266–269. doi: 10.1038/330266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris M, Hislop S, Patsilinacos P, Neil J C. In vivo derived HIV-1 nefgene products are heterogeneous and lack detectable nucleotide binding activity. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1992;8:537–543. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho D D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hua J, Blair W, Truant R, Cullen B R. Identification of regions in HIV-1 Nef required for efficient downregulation of cell surface CD4. Virology. 1997;231:231–238. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Zhang L, Ho D D. Characterization of nefsequences in long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1995;69:93–100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.93-100.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, Zhang L, Ho D D. Biological characterization of nefin long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1995;69:8142–8146. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8142-8146.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huet T, Cheynier R, Meyerhans A, Roelants G, Wain-Hobson S. Genetic organization of a chimpanzee lentivirus related to HIV-1. Nature. 1990;345:356–359. doi: 10.1038/345356a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iafrate A J, Bronson S, Skowronski J. Separable functions of Nef disrupt two aspects of T cell receptor machinery: CD4 expression and CD3 signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:673–684. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karn T, Hock B, Holtrich U, Adamski M, Strebhardt K, Rubsamen-Waigmann H. Nef proteins of distinct HIV-1 or HIV-2 isolates differ in their binding properties for Hck: isolation of a novel Nef binding factor with characteristics of an adaptor protein. Virology. 1998;246:45–52. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kestler H W, III, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nefgene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan I H, Sawai E T, Antonio E, Weber C J, Mandell C P, Montbriand P, Luciw P A. Role of the SH3-ligand domain of simian immunodeficiency virus Nef in interaction with Nef-associated kinase and simian AIDS in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1998;72:5820–5830. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5820-5830.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchhoff F, Easterbrook P J, Douglas N, Troop M, Greenough T C, Weber J, Carl S, Sullivan J L, Daniels R S. Sequence variations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef are associated with different stages of disease. J Virol. 1999;73:5497–5508. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5497-5508.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirchhoff F, Munch J, Carl S, Stolte N, Matz-Rensing K, Fuchs D, Ten Haaft P, Heeney J L, Swigut T, Skowronski J, Stahl-Hennig C. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef gene can to a large extent replace simian immunodeficiency virus nefin vivo. J Virol. 1999;73:8371–8383. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8371-8383.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koyanagi Y, Miles S, Mitsuyasu R T, Merrill J E, Vinters H V, Chen I S Y. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science. 1987;236:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.3646751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu L X, Margottin F, Le Gall S, Schwartz O, Selig L, Benarous R, Benichou S. Binding of HIV-1 Nef to a novel thioesterase enzyme correlates with Nef-mediated CD4 down-regulation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13779–13785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu X, Yu H, Liu S-H, Brodsky F M, Peterlin B M. Interactions between HIV1 Nef and vacuolar ATPase facilitate the internalization of CD4. Immunity. 1998;8:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo T, Livingston R A, Garcia J V. Infectivity enhancement by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef is independent of its association with a cellular serine/threonine kinase. J Virol. 1997;71:9524–9530. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9524-9530.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandell C P, Reyes R A, Cho K, Sawai E T, Fang A L, Schmidt K A, Luciw P A. SIV/HIV nefrecombinant virus (SHIVnef) produces simian AIDS in rhesus macaques. Virology. 1999;265:235–251. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mangasarian A, Foti M, Aiken C, Chin D, Carpentier J-L, Trono D. The HIV-1 Nef protein acts as a connector with sorting pathways in the golgi and at the plasma membrane. Immunity. 1997;6:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mangasarian A, Piguet V, Wang J-K, Chen Y-L, Trono D. Nef-induced CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) down-regulation are governed by distinct determinants: N-terminal alpha helix and proline repeat of Nef selectively regulate MHC-I trafficking. J Virol. 1999;73:1964–1973. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1964-1973.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mariani R, Skowronski J. CD4 down-regulation by nefalleles isolated from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5549–5553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Holloway G, Smith K, Deacon N, Pemberton L, Brew B J. Anomalies in Nef expression within the central nervous system of HIV-1 positive individuals/AIDS patients with or without AIDS dementia complex. J Neurovirol. 1998;4:291–300. doi: 10.3109/13550289809114530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michael N L, Chang G, D'Arcy L A, Tseng C J, Birx D L, Sheppard H W. Functional characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type I nefgenes in patients with divergent rates of disease progression. J Virol. 1995;69:6758–6769. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6758-6769.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mwaengo D M, Novembre F J. Molecular cloning and characterization of viruses isolated from chimpanzees with pathogenic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infections. J Virol. 1998;72:8976–8987. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8976-8987.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piguet V, Gu F, Foti M, Demaurex N, Gruenberg J, Carpentier J-L, Trono D. Nef-induced CD4 degradation: a diacidic-based motif in Nef functions as a lysosomal targeting signal through the binding of β-COP in endosomes. Cell. 1999;97:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piguet V, Schwartz O, Le Gall S, Trono D. The downregulation of CD4 and MHC-I by primate lentiviruses: a paradigm for the modulation of cell surface receptors. Immunol Rev. 1999;168:51–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piguet V, Wan L, Borel C, Mangasarian A, Demaurex N, Thomas G, Trono D. HIV-1 Nef protein binds to the cellular protein PACS-1 to downregulate class I major histocompatibility complexes. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:163–167. doi: 10.1038/35004038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poulin L, Levy J A. The HIV-1 nefgene product is associated with phosphorylation of a 46 kD cellular protein. AIDS. 1992;6:787–791. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratner L, Joseph T, Bandres J, Ghosh S, Vander Heyden N, Templeton A, Hahn B, Powderly W, Arens M. Sequence heterogeneity of Nef transcripts in HIV-1-infected subjects at different stages of disease. Virology. 1996;223:245–250. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Renkema G H, Manninen A, Mann D A, Harris M, Saksela K. Identification of the Nef-associated kinase as p21-activated kinase 2. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1407–1410. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renkema G H, Saksela K. Interactions of HIV-1 Nef with cellular signal transducing proteins. Front Biosci. 2000;5:268–283. doi: 10.2741/renkema. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rhee S S, Marsh J W. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef-induced down-modulation of CD4 is due to rapid internalization and degradation of surface CD4. J Virol. 1994;68:5156–5163. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5156-5163.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sawai E T, Baur A, Struble H, Peterlin B M, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with a cellular serine kinase in T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1539–1543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawai E T, Khan I H, Montbriand P M, Peterlin B M, Cheng-Mayer C, Luciw P A. Activation of PAK by HIV and SIV nef: importance for AIDS in rhesus macaques. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz D H, Viscidi R, Laeyendecker O, Song H, Ray S C, Michael N. Predominance of defective proviral sequences in an HIV+long-term non-progressor. Immunol Lett. 1996;51:3–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwartz O, Marechal V, Le Gall S, Lemonnier F, Heard J-M. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat Med. 1996;2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shugars D C, Smith M S, Glueck D H, Nantermet P V, Seillier-Moiseiwitsch F, Swanstrom R. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nefgene sequences present in vivo. J Virol. 1993;67:4639–4650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4639-4650.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simon F, Mauclere P, Roques P, Loussert-Ajaka I, Muller-Trutwin M C, Saragosti S, Georges-Courbot M C, Barre-Sinoussi F, Brun-Vezinet F. Identification of a new human immunodeficiency virus type 1 distinct from group M and group O. Nat Med. 1998;4:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terwilliger E, Sodroski J G, Rosen C A, Haseltine W A. Effects of mutations within the 3′ orfopen reading frame region of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type III (HTLV-III/LAV) on replication and cytopathogenicity. J Virol. 1986;60:754–760. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.754-760.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei Q, Fultz P N. Extensive diversification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype B strains during dual infection of a chimpanzee that progressed to AIDS. J Virol. 1998;72:3005–3017. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3005-3017.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G M. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wiskerchen M, Cheng-Mayer C. HIV-1 Nef association with cellular serine kinase correlates with enhanced virion infectivity and efficient proviral DNA synthesis. Virology. 1996;224:292–301. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zanotto P M de A, Kallas E G, de Souza R F, Holmes E C. Genealogical evidence for positive selection in the nefgene of HIV-1. Genetics. 1999;153:1077–1089. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.3.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zazopoulos E, Haseltine W A. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Eli Nef function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6634–6638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu T, Korber B T, Nahmias A J, Hooper E, Sharp P M, Ho D D. An African HIV-1 sequence from 1959 and implications for the origin of the epidemic. Nature. 1998;391:594–597. doi: 10.1038/35400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]