Abstract

Using a Tn3-based transposon mutagenesis approach, we have generated a pool of murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) mutants. In this study, one of the mutants, RvM27, which contained the transposon sequence at open reading frame M27, was characterized both in tissue culture and in immunocompetent BALB/c mice and immunodeficient SCID mice. Our results suggest that the M27 carboxyl-terminal sequence is dispensable for viral replication in vitro. Compared to the wild-type strain and a rescued virus that restored the M27 region, RvM27 was attenuated in growth in both BALB/c and SCID mice that were intraperitoneally infected with the viruses. Specifically, the titers of RvM27 in the salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys of the infected SCID mice at 21 days postinfection were 50- to 500-fold lower than those of the wild-type virus and the rescued virus. Moreover, the virulence of the mutant virus appeared to be attenuated, because no deaths occurred among SCID mice infected with RvM27 for up to 37 days postinfection, while all the animals infected with the wild-type and rescued viruses died within 27 days postinfection. Our observations provide the first direct evidence to suggest that a disruption of M27 expression results in reduced viral growth and attenuated viral virulence in vivo in infected animals. Moreover, these results suggest that M27 is a viral determinant required for optimal MCMV growth and virulence in vivo and provide insight into the functions of the M27 homologues found in other animal and human CMVs as well as in other betaherpesviruses.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is an important opportunistic pathogen affecting individuals whose immune functions are compromised or immature (4, 29). The virus is a leading cause of retinitis-associated blindness and other debilitating conditions such as pneumonia and enteritis among AIDS patients (15, 35, 45, 46). Moreover, it causes mental and behavioral dysfunctions in children who were infected in utero (14). HCMV also accounts for serious posttransplant complications among allograft recipients undergoing immunosuppressive treatment (4).

HCMV contains a linear DNA genome of 230 kb that is predicted to encode more than 200 proteins (7). This virus belongs to the family of betaherpesviruses whose members have the common characteristic of being highly species specific (4, 29). This characteristic precludes the use of experimental animals in studying HCMV infections. There is currently no animal model suitable for studying HCMV pathogenesis. Consequently, other related model systems involving animal CMVs, such as murine, rat, guinea pig, and primate CMVs, have to be used to provide insight into the tissue tropism, virulence, latency, and reactivation of HCMV (19, 22, 29).

Murine CMV (MCMV) is a natural pathogen of mice that possesses a remarkable biological resemblance to HCMV. The two viruses have extensive homology in many of their genes (7, 38), and they exhibit a strikingly similar pathogenesis in their respective hosts (19, 22, 29). Comparison of the complete genomic sequence of HCMV and MCMV revealed that more than 75 open reading frames in these two viruses show extensive sequence homology (7, 38). Both viruses initiate acute infection by targeting common organs and tissues in their hosts, after which infection typically progresses to persistence, latency, and periodic reactivation (19, 22, 29). The similarities between the two viruses, plus the availability of a vast pool of genetically defined strains of mice, have made MCMV an excellent model system for studying the biology of CMV infections and virus-host interactions and providing insight into the mechanism of HCMV pathogenesis. An understanding of the function of MCMV-encoded genes, especially those that are highly homologous to those encoded by HCMV, in mice is expected to provide insight into the functions of their HCMV counterparts in viral pathogenesis in humans.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the power of mutagenesis in studying the functions of herpesvirus genes (see reviews in references 29 and 41). By specifically mutagenizing a gene and then analyzing the phenotype of the mutated virus both in vitro in tissue culture and in vivo in animal models, it has been possible to map on the herpesvirus genome specific viral functions, such as those involved in replication, tropism, virulence, and other biological phenomena such as viral immune evasion. The construction of herpesvirus mutants was first reported using site-directed homologous recombination and transposon-mediated insertional mutagenesis (21, 30, 37, 40, 55). Furthermore, methods using overlapping cosmid DNA fragments to generate mutants of HCMV and other herpesviruses have also been reported (8, 10, 23, 50, 51). More recently, the MCMV genome as well as the genomes of other herpesviruses have been cloned into a bacterial artificial chromosome and viral mutants have been successfully generated from the bacterial artificial chromosome-based viral genome by a bacterial mutagenesis procedure (3, 5, 12, 28, 43, 47–49, 54). These studies have greatly facilitated the identification of the functions of viral genes in tissue culture and in animals.

Many of the CMV genes have been found to be dispensable for growth in cultured cells. Their presence in the viral genome indicates that they are probably needed to perform functions involved in modulating viral interactions with the respective human or animal hosts. For example, MCMV open reading frame M83, which encodes one of the most abundant proteins found in the tegument and is dispensable for viral replication in vitro, is required for efficient viral replication and virulence in vivo (9, 31, 57). Thus, studies of viral mutants carrying mutations in genes found to be dispensable in tissue culture are valuable for understanding the function of the genes in viral pathogenesis and virus-host interactions.

We have previously reported on the use of a Tn3-based transpositional mutagenesis approach to disrupt genes in the MCMV genome and the construction of recombinant viruses that carry the disrupted genes (56, 57). In this approach, the transposon is randomly inserted into the MCMV genomic DNA fragments in a plasmid library in Escherichia coli. Regions bearing an insertion mutation are then transferred to the MCMV genome by homologous recombination between the plasmid library and purified MCMV genomic DNA in NIH 3T3 cells. In the present study, we have characterized an MCMV mutant, RvM27, which contains a transposon insertion in open reading frame M27, a homologue of the HCMV UL27 open reading frame (7, 38). The function of M27 as well as that of UL27 is currently unknown. Indeed, the M27 and UL27 open reading frames have not been extensively characterized either transcriptionally or translationally. Our results provide the first direct evidence to suggest that a disruption of open reading frame M27 leads to attenuation of viral virulence and deficient growth in vivo. When the mutant virus was used to infect immunocompetent BALB/c mice and immunodeficient SCID mice intraperitoneally, the viral titers in the salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys were significantly lower than those in mice inoculated with the wild-type virus and a revertant virus that rescued the mutation and restored the M27 open reading frame. Moreover, the viral mutant was attenuated in killing SCID mice. These results suggest that M27 is a viral determinant for MCMV pathogenicity and is required for optimal viral virulence and growth in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

The Smith strain of MCMV, mouse NIH 3T3 cells, and STO cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). The Smith strain, viral mutant RvM27, and rescued virus RqM27 were grown in NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC CRL 1658) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Nu-Serum (Collaborative Research Inc., Waltham, Mass.), 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 0.1 mM MEM amino acids (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). STO cells (ATCC CRL 1503) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL) plus 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Animals.

The immunocompetent BALB/c-ByJ mice and immunodeficient CB17 SCID mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bay Harbor, Maine) and National Cancer Institute (Frederick, Md.), respectively, and used at 3 to 5 weeks of age. Mice were acclimatized for 2 to 3 days prior to infection. Mice were housed in microisolator cages and fed and watered ad libitum throughout the experiments.

Construction of MCMV mutants by transposon-based shuttle mutagenesis and generation of rescued virus.

The transposon Tn3gpt, which is derived from the Tn3 transposon from E. coli (6, 42, 44), contains the expression cassette encoding guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (gpt) (which contains the gpt coding sequence driven by a promoter and a transcription termination signal) and an additional transcription termination site (Fig. 1A) (56). Isolation of viral genomic DNA, construction of an MCMV genomic subclone pool, and transposon-based shuttle mutagenesis to generate a pool of MCMV DNA fragments (MCMV-Tn3gpt) containing a Tn3gpt insertion were performed as described by Zhan et al. (56). To generate a pool of MCMV mutants that contained the transposon sequence, full-length MCMV genomic DNA and plasmid DNA containing MCMV-Tn3gpt fragments were cotransfected into NIH 3T3 cells using a calcium phosphate precipitation protocol (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). The recombinant MCMV was selected in the presence of mycophenolic acid (25 μg/ml; Gibco-BRL) and xanthine (50 μg/ml) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and plaque purified three times following the protocol described previously (57). To confirm the integration of the transposon in the viral genome and identify the genes that contained the transposon insertion, viral DNA was purified and directly sequenced using the primer FL110OPRIM (5′-GCAGGATCCTATCCATATGAC-3′) by the Fmol cycle sequencing kit (Promega, Inc., Madison, Wis.).

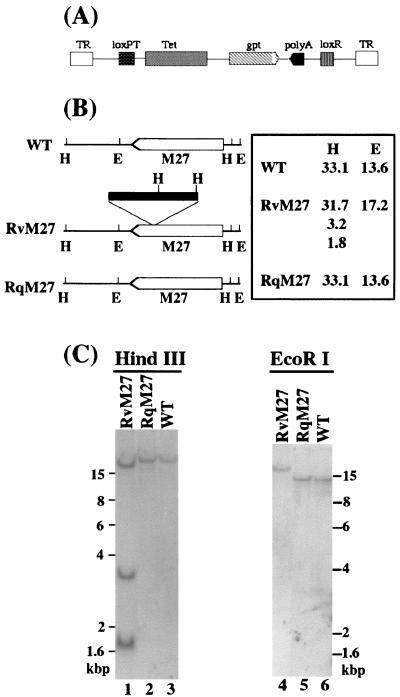

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the structure of the transposon construct used for mutagenesis. Tet, tetracycline resistance gene; gpt gene that encodes guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (gpt); poly(A), transcription termination signal. (B) Location of the transposon insertion in the recombinant virus. The transposon sequence is shown as a solid bar, while the coding sequence of open reading frame M27 is represented by an open arrow. The orientation of the arrow represents the direction of translation and transcription predicted from the nucleotide sequence (38). The numbers represent the sizes of the DNA fragments of the viruses that were generated by digestion with HindIII (H) or EcoRI (E). (C) Southern analyses of the recombinant viruses. The DNA fractions were isolated from cells infected with the wild-type (WT) virus, RvM27, or RqM27. The DNA samples (10 μg) were digested with either HindIII or EcoRI, separated on 1% agarose gels, transferred to a Zeta-Probe membrane, and hybridized to a DNA probe. The probe used for the analyses was the plasmid that contained the MCMV DNA fragment carrying the transposon sequence.

To construct the rescued virus RqM27, the full-length genomic DNA of RvM27 was isolated from virus-infected cells as described previously (57). The DNA sequence that contained the coding sequence of M27 was generated by PCR using MCMV genomic DNA as the template, the 5′ primer M27-sense (5′-ACCTGTAGCTAGACCCGATG-3′), and the 3′ primer M27-antisense (5′-TGCGTCCAGCGCGACATGGA-3′). The PCR product that contained the M27 coding sequence (3 to 10 μg) and the full-length intact RvM27 genomic DNA (8 to 12 μg) were subsequently cotransfected into mouse STO cells using a calcium phosphate precipitation protocol (Gibco-BRL). The recombinant virus was selected in STO cells in the presence of 6-thioguanine (25 μg/ml; Sigma) and purified by six rounds of amplification and plaque purification, following the protocol described previously (17). For each cotransfection, several viral plaques were picked and expanded. Viral stocks were prepared by growing the viruses in roller bottles of NIH 3T3 cells.

Northern and Southern analyses of recombinant viruses.

For Northern blot analysis, cells were infected with virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 and harvested at different time points postinfection. In the experiments to assay the expression of immediate-early transcripts, cells were treated with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml; Sigma) and then infected with viruses and harvested at 6 h postinfection (25). Total cytoplasmic RNA was isolated from NIH 3T3 cells infected with the viruses as described previously (24). Viral RNAs were separated in 0.8 to 1% agarose gels that contained formaldehyde, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, hybridized with the 32P-radiolabeled DNA probes that contained the MCMV sequences, and finally analyzed with a STORM840 phosphoimager. The DNA probes used for Northern analyses were generated by PCR using viral DNA as the template and radiolabeled with a random primer synthesis kit in the presence of [α-32P]dCTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). The 5′ PCR primers used in the construction of DNA probes for the Northern analysis of the M27 and M25 transcripts were M27-5′NDS (5′-GGATTCGTCGGGCTCCGACG-3′) and M25-5′NDS (5′-CGACGACGATGACGACGATG-3′), respectively. The 3′ PCR primers used were M27-3′NDS (5′-CCGCTCCACCACAAACTCGG-3′) and M25-3′NDS (5′-GTCCTGACCGCTCACTACAC-3′), respectively.

For Southern blot analysis, viral DNA was purified from NIH 3T3 cells infected with the viruses as described previously (52, 56). Briefly, cells that exhibited 100% cytopathic effect were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed using a solution that contained sodium dodecyl sulfate and proteinase K. The genomic DNA was purified by extraction with phenol-chloroform followed by precipitation with 2-propanol. The DNA was then digested with HindIII or EcoRI, separated on agarose gels (0.8 to 1%), transferred to Zeta-Probe nylon membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), hybridized with the 32P-radiolabeled DNA probes that contained the transposon and the MCMV M27 sequence, and finally analyzed with a STORM840 phosphoimager (57). The labeled DNA probes were prepared by random primer synthesis (Boehringer Mannheim).

Analysis of growth of viruses in vitro.

The growth kinetics of the viruses was determined as described previously (57). Briefly, NIH 3T3 cells grown to 60 to 75% confluence were inoculated with virus at an MOI of either 0.5 or 5. At 0, 1, 2, 4, and 7 days postinfection, the infected cells together with medium were harvested, and an equal volume of 10% skim milk was added before sonication. Virus titer was determined by plaque assays in NIH 3T3 cells. The titers reported are the averages of triplicate experiments.

Analysis of viral virulence in SCID mice.

The virulence of the viruses was studied by determining the mortality rates of animals infected with the Smith strain, RvM27, or RqM27. Male CB17 SCID mice (4 to 6 weeks old, five animals per group) were infected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of each virus. The viral inoculum used for the infection of animals were prepared by growing the viruses in NIH 3T3 cells. The animals were observed twice daily, the mortality of the infected animals was monitored for at least 41 days postinfection, and the survival rates for each virus were determined.

Analysis of growth of viruses in BALB/c and SCID mice.

The viral inoculum used for the infection of animals were prepared by growing the viruses in NIH 3T3 cells. Male BALB/c-ByJ mice (3 to 4 weeks old) or CB17 SCID mice (4 to 6 weeks old) were infected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of each virus. The infected animals were sacrificed at 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days postinoculation. Moreover, the salivary glands were also collected from the BALB/c mice at 28 and 35 days postinfection. For each time point, at least three animals were used as a group and infected with the same virus. The salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys were harvested and sonicated as a 10% (wt/vol) suspension in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and 10% skim milk. The sonicates were stored at −80°C until plaque assays were performed.

Plaque assays were performed in NIH 3T3 cells plated overnight to about 60 to 75% confluence in six-well cluster plates (Costar, Corning, N.Y.). Tenfold serial dilutions of virus in 1 ml of DMEM were inoculated onto each well of NIH 3T3 cells. After 90 min of incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, the cells were washed with DMEM and then overlaid with DMEM containing 1% low-melt-point agarose (Sigma). Viral plaques were counted after 4 to 6 days under an inverted microscope. Each sample was assayed in triplicate, and the titer of the sample was expressed as the average of the three values. Viral titers were recorded as PFU per milliliter of organ homogenate. The limit of virus detection in the organ homogenates was 10 PFU/ml of the sonicated mixture. Those samples that were negative at a 10−1 dilution were designated as having a titer of 10 (101) PFU/ml.

RESULTS

Construction of an MCMV mutant containing the transposon insertion at open reading frame M27 and the rescued virus that restored the mutation.

We have constructed a pool of MCMV mutants using an E. coli Tn3-based transposon mutagenesis system (57). In our mutagenesis procedure, an MCMV genomic library containing a randomly inserted transposon (designated Tn3gpt) in each viral DNA fragment was first generated using a shuttle mutagenesis method described previously (56). Such a pool of MCMV genomic fragments containing randomly inserted Tn3gpt sequence were then cotransfected with the full-length genomic DNA of the wild-type virus (Smith strain) into mouse NIH 3T3 cells, in which homologous recombination occurred. The cells that harbored the progeny viruses expressing the gpt gene were selected for growth in the presence of mycophenolic acid and xanthine (17, 32, 52). Individual recombinant viruses were isolated after multiple rounds of selection and plaque purification. The location of the inserted transposon was determined by directly sequencing the genomic DNA of the recombinants. One of the recombinant viruses, designated RvM27, contained the transposon insertion within open reading frame M27 (Fig. 1B). Figure 1A shows the structure of the transposon used to generate the MCMV mutant. The transposon contains the expression cassette consisting of the gpt gene driven by a promoter and a transcription termination signal and an additional transcription termination site, which allows the selection of MCMV mutants in mammalian cells and the truncation of the transcript expressed from the disrupted gene (56). The gpt expression cassette was inserted so that its transcription termination site functioned in the opposite direction from the other poly(A) signal in the transposon (Fig. 1A). Such a design would ensure that the transcription of the targeted gene is disrupted without altering the expression of nearby genes that may share a poly(A) signal with the disrupted gene. Sequence analyses of the junction between the transposon and the viral sequence in RvM27 revealed that the transposon is located at nucleotide position 32863 (amino acid residue 477 of the 682-amino-acid-long open reading frame) in reference to the genome sequence of the wild-type Smith strain (38) (Fig. 1B and data not shown).

It has been observed that spontaneous mutations within the viral genome, including deletion and rearrangement, can be generated during construction of viral mutants using a homologous recombination approach (26) (G. Abenes, X. Zhan, M. Lee, and F. Liu, unpublished results). To exclude the possibility that the phenotype observed with RvM27 might be due to some other adventitious mutations in the genome of the viral mutant rather than to the disruption of the M27 open reading frame, a rescued virus, RqM27, was derived from RvM27 by restoration of the wild-type M27 sequence in RvM27 (Fig. 1B). Construction of the rescued virus was carried out using a procedure similar to that used for generating the viral mutant. A DNA fragment that contained the M27 coding region was cotransfected with the full-length RvM27 genomic DNA into mouse STO cells to allow homologous recombination to occur. The cells that harbored the progeny viruses were allowed to grow in the presence of 6-thioguanine, which selects against gpt expression (17, 32). The rescued virus, designated RqM27, which did not express the gpt-encoded protein and no longer contained the transposon, was isolated after multiple rounds of selection and plaque purification.

Characterization of mutant RvM27 and rescued virus RqM27 in tissue culture.

The genomic structures of the recombinant viruses were examined by Southern blot hybridization and compared to that of the wild-type Smith strain, using a DNA probe containing both the transposon and the viral sequences (Fig. 1B and 1C). The sizes of the RvM27 hybridized DNA fragments (Fig. 1C) were consistent with the predicted digestion patterns of the viral mutant based on the MCMV genomic sequence (38) and the location of the transposon insertion in the viral genome as determined by sequence analysis (Fig. 1B). The restriction enzyme digestion patterns of the regions of the RvM27 genomic DNA other than the transposon insertion site appeared to be identical to those of the parental Smith strain, as indicated by ethidium bromide staining of the digested DNAs (data not shown). This observation suggested that regions of the viral genome other than the region containing the transposon insertion remained intact in this MCMV mutant. Analysis of the RqM27 DNA samples digested with HindIII and EcoRI showed that the sizes of the hybridized DNA fragments for the rescued virus were identical to those of the hybridized fragments for strain Smith and were different from those for RvM27 (Fig. 1B and C, lanes 2 and 5). These results indicate that RqM27 did not contain the transposon sequence and that the M27 region was restored (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 and 5). Moreover, the restriction enzyme digestion patterns of the regions of the rescued RqM27 genomic DNA samples other than the M27 region appeared to be identical to those of the parental RvM27, as indicated by ethidium bromide staining of the digested DNAs (data not shown). This observation suggested that the regions of the genome of RqM27 other than the M27 region remained intact and were identical to those of RvM27. Thus, RqM27 represents a rescued virus derived from RvM27.

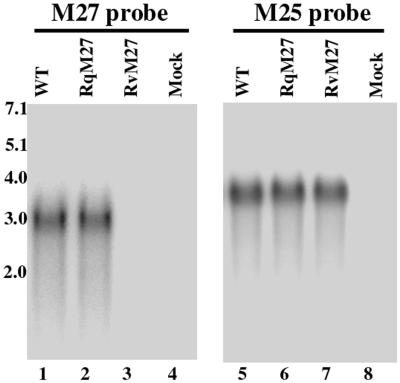

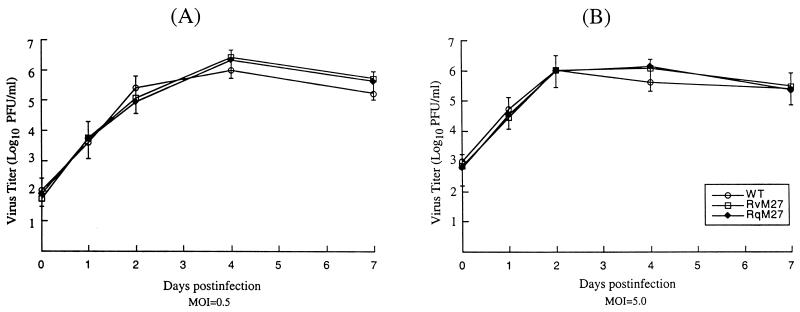

Transcription from the target M27 region is expected to be disrupted due to the presence of the two transcription termination signals within the transposon (Fig. 1A). In particular, the region of the M27 open reading frame downstream from the transposon insertion site is not expected to be expressed. To determine whether this is the case, cytoplasmic RNAs were isolated from cells infected with the mutant virus at different time points (4, 12, and 24 h) postinfection. Northern analysis was carried out to examine the expression of the transcripts from the M27 open reading frame downstream from the transposon insertion site (Fig. 2). The probe (the 3′ probe) used in the Northern analyses contained the DNA sequence complementary to the 3′ M27 coding region that is within 200 nucleotides downstream from the site of the transposon insertion. An RNA species of about 3 kb was detected in the RNA fractions isolated from cells that were infected with the wild-type Smith strain (Fig. 2, lane 1). This ∼3-kb RNA species was also readily detected from cells infected with the Smith strain using a DNA probe (the 5′ probe) complementary to the 5′-terminal sequence of M27 open reading frame that is within 300 nucleotides downstream from the M27 translation initiation site (data not shown) (56). These results suggest that this ∼3-kb RNA species represents the transcript expressed from the M27 open reading frame. However, this transcript was not detected in the RNA fractions isolated from cells infected with RvM27 when the 3′ probe, which is complementary to the M27 coding region downstream from the site of the transposon insertion, was used in the Northern analyses (Fig. 2, lane 3). These observations suggest that transcription from the M27 region downstream from the transposon insertion site was disrupted in RvM27. Meanwhile, expression of the transcript was found in the RNA fractions from cells infected with the rescued virus RqM37 (Fig. 2, lane 2). The level of MCMV M25 transcript (11, 57) was used as the internal control for expression of the M27 transcript. As shown in Fig. 2, the levels of the M25 transcript detected in cells that were infected with RvM27 and RqM27 were found to be similar to that of M25 transcript in cells infected with the Smith strain (Fig. 2, lanes 5 to 8). Thus, the transposon insertion in RvM27 appeared to disrupt the transcript expressed from the M27 open reading frame, whereas the wild-type expression of the transcript was restored in RqM27. In order to determine whether these viruses had any growth defects in vitro, experiments were carried out to study the growth rates of the recombinant viruses in NIH 3T3 cells. Cells were infected with these viruses at both low and high MOIs, and their growth rates were assayed in triplicate experiments. No significant difference was found in growth rates among RvM27, RqM27, and the Smith strain (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Northern analyses of RNA fractions isolated from cells that were mock infected (lanes 4 and 8) or infected with the wild-type (WT) virus (lanes 1 and 5), RqM27 (lanes 2 and 6), and RvM27 (lanes 3 and 7). A total of 5 × 106 NIH 3T3 cells were infected with each virus at an MOI of 5 PFU per cell, and cells were harvested at 24 h postinfection. RNA samples (20 μg in lanes 1 to 4 and 10 μg in lanes 5 to 8) were separated on agarose gels that contained formaldehyde, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and hybridized to a 32P-radiolabeled probe that contained the sequence of M27 (M27 probe) (lanes 1 to 4) or M25 (M25 probe) (lanes 5 to 8). Sizes are shown in kilobase pairs.

FIG. 3.

In vitro growth of MCMV mutants in tissue culture. Mouse NIH 3T3 cells were infected with each virus at an MOI of either 0.5 PFU (A) or 5 PFU (B) per cell. At 0, 1, 2, 4, and 7 days postinfection, cells and culture medium were harvested and sonicated. The viral titers were determined by plaque assays on NIH 3T3 cells. The titers represent the averages obtained from triplicate experiments. The standard deviation is indicated by the error bars.

Deficient growth of recombinant virus RvM27 in immunocompetent animals.

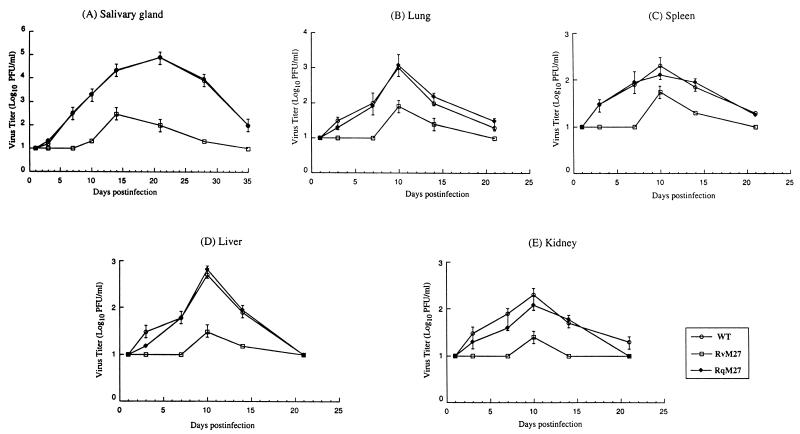

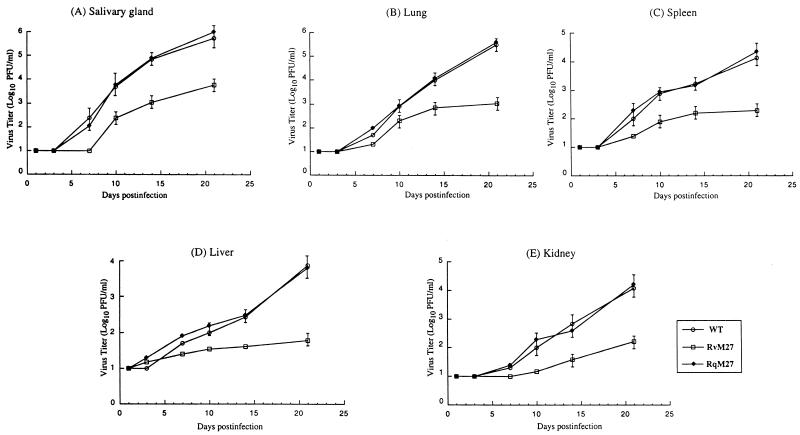

To determine whether disruption of M27 adversely affects viral replication in vivo, BALB/c-ByJ mice were injected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of RvM27, RqM27, or the wild-type Smith strain. The viral inocula used for the infection of animals were prepared by growing the viruses in NIH 3T3 cells. At 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days postinfection, salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys were harvested, and the viral particles in these five organs were counted on NIH 3T3 cells. Moreover, the titers of viruses from the salivary glands at 28 and 35 days postinfection were also determined. These organs are among the major targets for MCMV infection (4, 19, 22, 29). At 21 and 28 days postinfection, the titers of RvM27 found in the salivary glands were about 500-fold lower than those of the Smith strain (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the peak titers of RvM27 found in the lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys of the infected animals at 10 days postinfection were about 10-, 2-, 10-, and 5-fold lower, respectively, than the titers in the same organs from animals infected with the Smith strain (Fig. 4B to E). In contrast, the titers of the rescued virus RqM27 found in the same organs were similar to the titers of the Smith strain. Previous studies have shown that the presence of the transposon sequence per se within the viral genome does not significantly affect viral growth in BALB/c mice in vivo (57). Thus, these results suggest that the growth deficiency of RvM27 in the organs examined is due to the disruption of M27 and that open reading frame M27 is important for optimal viral growth in vivo, at least in these organs in BALB/c mice.

FIG. 4.

Titers of MCMV mutants in the salivary glands (A), lungs (B), spleens (C), livers (D), and kidneys (E) of infected BALB/c mice. BALB/c-Byj mice were infected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of each virus. At 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days postinfection, the animals (three mice per group) were sacrificed. The salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys were collected and sonicated. Moreover, the salivary glands were also collected from animals at 28 and 35 days postinfection. The viral titers in the tissue homogenates were determined by standard plaque assays in NIH 3T3 cells. The limit of detection was 10 PFU/ml of tissue homogenate. The titers represent the averages obtained from triplicate experiments. The error bars indicate the standard deviation. Some error bars are not evident because the standard deviation bar is less than or equal to the height of the symbols.

Attenuated virulence and deficient growth of recombinant virus RvM27 in immunodeficient SCID mice.

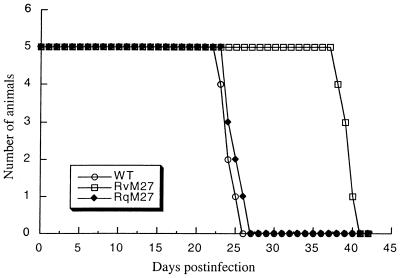

Immunodeficient animals have been shown to be extremely susceptible to MCMV infection (18, 34, 36, 39). For example, CB17 SCID mice, which lack functional T and B lymphocytes, are sensitive to low levels of viral replication, as these animals succumb to as little as 10 PFU of MCMV (34, 36). Analysis of viral replication in these mice serves as an excellent model for comparing the virulence of different MCMV strains and mutants and for studying how they cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised hosts. To determine whether the M27 open reading frame plays a significant role in MCMV virulence, the survival rates of animals infected with RvM27 were determined and compared to those of animals infected with RqM27 and the wild-type Smith strain. The viral inocula used for the infection of animals were prepared by growing the viruses in NIH 3T3 cells. For each virus, five SCID mice were injected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of RvM27, RqM27, or the Smith strain. All the mice that were infected with either strain Smith or RqM27 died within 25 to 26 days postinfection (Fig. 5). In contrast, no animals infected with RvM27 died until 37 days postinfection (Fig. 5). This observation indicated that RvM27 was attenuated in viral virulence in killing SCID mice. It has recently been demonstrated in our laboratory that the presence of the transposon sequence per se within the viral genome does not significantly affect MCMV virulence in killing SCID mice (57). Thus, these results suggest that disruption of the M27 open reading frame diminishes viral virulence and that M27 plays an important role in MCMV virulence in SCID mice.

FIG. 5.

Mortality of SCID mice infected with strain Smith, (WT), RvM27, and RqM27. CB17 SCID mice (five animals per group) were infected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of each virus. Mortality of mice was monitored for at least 41 days postinfection, and survival rates were determined.

To further study the pathogenesis of the mutant virus in these immunodeficient animals, the replication of RvM27 in different organs of the animals was studied during a 21-day infection period before the onset of mortality of the infected animals. In these experiments, SCID mice were injected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of each virus (RvM27, RqM27, or the wild-type Smith strain). At 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days postinfection, three mice from each virus group were sacrificed, and the salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys were harvested. The levels of viral growth in these five organs were determined by assaying the viral titers in the organs. The titers of RqM27 in each of the organs examined were similar to those of the Smith strain (Fig. 6). In contrast, the titers of the mutant virus RvM27 were consistently lower than those of the wild-type virus at every time point examined. At 21 days postinfection, the titers of RvM27 in the salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys of the infected animals were lower than the titers of the wild-type virus by 50-, 400-, 50-, 100-, and 50-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). Therefore, RvM27 appears to grow poorly in the organs of the immunodeficient animals. Previous studies have shown that the presence of the transposon sequence per se within the viral genome does not significantly affect viral growth in SCID mice in vivo (57). Thus, these results suggest that the attenuated growth of RvM27 in these organs is probably due to the disruption of M27 and that open reading frame M27 may be required for optimal growth of MCMV in these organs in immunodeficient hosts.

FIG. 6.

Titers of MCMV wild-type (WT) and mutants in the salivary glands (A), lungs (B), spleens (C), livers (D), and kidneys (E) of infected SCID mice. CB17 SCID mice were infected intraperitoneally with 104 PFU of each virus. At 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 days postinfection, the animals (three mice per group) were sacrificed. The salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys were collected and sonicated. The viral titers in the tissue homogenates were determined by standard plaque assays in NIH 3T3 cells. The limit of detection was 10 PFU/ml of tissue homogenate. The titers represent the averages obtained from triplicate experiments. The error bars indicate the standard deviation. Some error bars are not evident because the standard deviation bar is less than or equal to the height of the symbols.

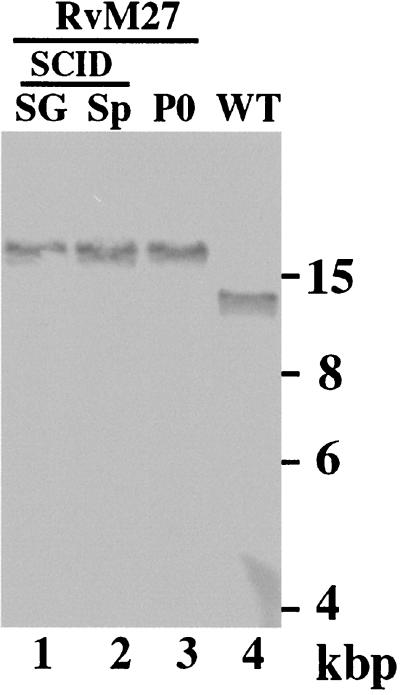

Genome and transposon mutation of RvM27 are stable during viral growth in SCID mice.

It has been found that some MCMV mutants with an insertional sequence are not stable and generate spontaneous mutations during replication in vitro and in vivo (2, 26) (Abenes et al., unpublished results). It is possible that the transposon sequence in RvM27 is not stable during the viral replication in vivo and the introduction of an adventitious mutation may be responsible for the observed phenotypes of the virus in animals. To address this issue, the salivary glands and spleens of RvM27-infected SCID mice were harvested at 21 days postinfection. The viruses were subsequently recovered from these organs by infecting NIH 3T3 cells with the sonicated tissue homogenates. Viral DNAs were purified from the infected cells, and their restriction digestion patterns were analyzed in agarose gels. Figure 7 shows a Southern analysis of the RvM27 viral DNAs with a DNA probe that contained the transposon and the M27 open reading frame sequence. The results showed that no change in the hybridization patterns of RvM27 occurred as a result of viral growth in animals for 21 days (lanes 1 to 4). Moreover, the overall HindIII digestion patterns of RvM27 DNA isolated from either infected cultured cells or animals were identical to those of the original recombinant virus RvM27, as visualized by ethidium bromide staining of the viral DNAs (data not shown). Thus, the transposon insertion in RvM27 appeared to be stable, and the genome of RvM27 remained intact during replication in the infected animals.

FIG. 7.

Stability of the genome and the transposon mutation of RvM27 during replication in SCID mice. Viral DNAs were isolated from cells that were infected with RvM27 (MOI of <0.01) and allowed to grow in culture for 5 days (P0) (lane 3) or from cells that were infected with the virus recovered from either the salivary glands (SG, lane 1) or spleen (Sp, lane 2) of SCID mice at 21 days after intraperitoneal inoculation with 104 PFU of RvM27. Southern analyses of the viral DNA fractions digested with EcoRI are shown. The DNA of the wild-type virus (WT) is shown in lane 4. The 32P-radiolabeled probe was derived from the same plasmid which was used for Southern analyses of RvM27 in Fig. 1 and contained the transposon and M27 open reading frame sequence.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized the virulence and growth of a recombinant virus in vitro and in both immunocompetent BALB/c mice and immunodeficient SCID mice. This viral mutant, RvM27, contained an insertional mutation at open reading frame M27. Our results provide the first direct evidence to suggest that disruption of the M27 open reading frame results in attenuated virulence and reduced growth of the virus in both BALB/c and SCID mice. Moreover, the results presented in this study suggest that M27 functions in supporting efficient viral replication in vivo and is required for optimal viral virulence in immunodeficient hosts.

Our results indicate that the transposon sequence was inserted into the M27 region and disrupted the coding sequence of the open reading frame (Fig. 1B). Moreover, transcription from the region downstream from the transposon insertion site was not detected in cells infected with the mutant virus (Fig. 2). Thus, the region of the target open reading frame downstream from the transposon insertion site, which includes the 3′ M27 coding sequence, was not expressed. RvM27 replicated in vitro in NIH 3T3 cells as well as the wild-type Smith strain and the rescued virus RqM27 (Fig. 3). These results suggest that M27 is dispensable for MCMV growth in vitro in NIH 3T3 cells.

MCMV infection in mice has been an excellent model for studies of CMV infections in vivo and for providing insights in HCMV pathogenesis in humans (19, 22, 29). For example, both MCMV and HCMV are opportunistic pathogens and cause severe infections in immunodeficient hosts (e.g., SCID mice and AIDS patients). In SCID mice, MCMV causes a systemic infection and replicates efficiently in most of the organs (see Fig. 6) (34, 36). The high viral titers in many of the organs and the destruction of host cells and tissues by viral infection usually lead to the death of the animals. The function of M27 is currently unknown. Indeed, to our knowledge, neither the transcript nor the protein product coded by this open reading frame has been extensively characterized. Our results indicate that a transcript of about 3,000 nucleotides is expressed from the M27 open reading frame. RvM27 was found to be deficient in replication in the salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys of both BALB/c and SCID mice that were intraperitoneally infected. For example, at 21 days postinfection, the titers of RvM27 in the salivary glands, lungs, spleens, livers, and kidneys of the infected SCID mice were lower than the titers of the wild-type virus by 50-, 400-, 50-, 100-, and 50-fold, respectively (Fig. 6). Moreover, no deaths occurred among SCID mice infected with RvM27 for up to 37 days postinfection, while all of the mice infected with the Smith strain or RqM37 died within 26 days postinfection (Fig. 5). These results strongly suggest that M27 is a viral determinant for MCMV growth in vivo in these animals and for viral virulence in killing SCID mice.

It is possible that the observed change in the level of replication of the mutant is due to adventitious mutations introduced during the construction and growth of the recombinant virus in cultured cells or in animals. However, several lines of evidence strongly suggest that this is unlikely. First, the wild-type phenotypes for growth and virulence in the infected mice were restored in RqM27 upon restoration of the wild-type sequence into RvM27 (Fig. 1, 4, 5, and 6). Furthermore, the restoration of the wild-type phenotypes in RqM27 occurred together with the restoration of M27 expression (Fig. 2). These observations suggest that the transposon insertion rather than an adventitious mutation is responsible for the observed attenuation of RvM27 replication and virulence in vivo. Second, our previous studies indicated that a virus mutant (Rvm09) with a transposon insertion at the m09 open reading frame replicated as well in both BALB/c and SCID mice as the wild-type virus (57). Moreover, mutant Rvm09 exhibited a level of virulence in killing SCID mice similar to the wild-type virus. These observations indicated that the transposon sequence per se in the viral genome does not significantly affect viral replication and virulence in the infected animals (57). Third, the genome and the transposon insertion in the viral mutant were stable during replication in animals. There was no change in the hybridization patterns of the DNAs from the mutant viruses that were recovered from the salivary glands and spleens of the infected animals after 21 days of infection (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Moreover, the HindIII digestion patterns of the RvM27 mutant DNAs, other than the transposon insertion region, appeared to be identical to those of the wild-type virus DNA (data not shown). Thus, the observed change in the level of RvM27 replication and virulence in the infected mice is probably due to the disruption of M27 expression as a result of the transposon insertion.

A transposon insertion mutagenesis approach, as demonstrated successfully by many other laboratories, is convenient for identifying gene functions in viral, bacterial, and yeast systems, especially when little is known about the genes and their functions. Results presented in this study as well as in our other recent studies (56, 57) further demonstrate that the Tn3 system can be used for simultaneous isolation of multiple viral mutants and may have advantages over traditional homologous recombination system for systematic generation of viral mutants. Each of these viral mutants contained a transposon insert of ∼3.6 kb, since the transposon sequence includes the selection marker genes coding for both the gpt and tetracycline resistance functions. These two markers were used for selection of the transposon-containing sequence in E. coli and in mammalian cell cultures. Viral mutants containing more subtle mutations (e.g., single point mutations in M27) can be generated from our transposon-containing mutants by traditional homologous recombination and selection against gpt expression, in a procedure similar to that used for the construction of RqM27. Further characterization of these mutants will facilitate the identification of the functional domains of M27 important for viral virulence and growth in vivo.

Homologues of M27 have been found in animal and human betaherpesviruses (e.g., rat CMV and HCMV) but not in alpha- and gammaherpesviruses (e.g., herpes simplex virus and Epstein-Barr virus) (7, 13, 16, 20, 27, 29, 33, 38, 41, 53). For example, M27 (38) has sequence homology with UL27 of HCMV (7), R27 of rat CMV (53), and U5/U7 of human herpesviruses 6 and 7 (13, 16, 20, 27, 33). The high degree of conservation of this open reading frame among animal and human CMVs suggests that the functions of M27 and its homologues are important in the pathogenesis and virulence of these viruses in vivo (7, 38, 53). Meanwhile, the low degree of sequence homology of these M27 homologues with genes found in other herpesviruses as well as in other organisms and hosts in the database suggest that their functions are unique in infections with these betaherpesviruses (7, 38, 53) (M. Lee, A. McGregor, G. Abenes, and F. Liu, unpublished results). The function of UL27 as well as other M27 homologues (e.g., R27 of rat CMV) is currently unknown. Indeed, to our knowledge, the products coded by these open reading frames have not been reported or characterized. Our results in this study provide the first direct evidence to suggest that M27 plays a significant role in MCMV virulence and growth in both immunocompetent BALB/c mice and immunodeficient SCID mice. It will be interesting to determine whether UL27 and other M27 homologues are also dispensable for viral replication in vitro and are also required for optimal viral growth and virulence in vivo. These studies will reveal whether these highly conserved open reading frames have similar functions in the pathogenesis and virulence of CMVs and betaherpesviruses.

A key question arising from our results is how the lack of a protein, such as M27, leads to a change in the level of viral growth and virulence. Very few viral mutants that contain a mutation at a single locus in the viral genome have been characterized for their growth and virulence in both BALB/c and SCID mice. Attempts have been made to compare the in vivo phenotypes of RvM27 with the phenotypes of other viral mutants, including those that were generated in our laboratory by transposon insertion at different loci of the viral genome (G. Abenes, M. Lee, J. Xiao, E. Haghjoo, T. Tuong, J. Kim, A. Tam, W. Dunn, X. Zhan, and F. Liu, unpublished results). These results revealed that the levels of attenuation in the growth and virulence of RvM27 in the infected animals are very similar to those of the viral mutants that contain a transposon mutation or a deletion in the M83 open reading frame, which encodes one of the most abundant viral tegument proteins (9, 31, 57). However, there is currently no evidence to suggest that the CMV virion or tegument contains UL27/M27 proteins (1). Moreover, the function of M83 as well as UL83 in vivo is currently not completely understood. Equally elusive is the mechanism of how the viral mutants with mutations at M83 diminished their growth and virulence in vivo. It is possible that a viral mutant disrupted in M83 or M27, while capable of replicating normally in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts, is deficient in its ability to spread to the target organs, to enter permissive cells, or to replicate in cells of particular organs or tissues in the infected animals. More detailed studies on the in vitro and in vivo growth of these mutants will reveal whether M27 functions similarly to M83 in supporting optimal growth and virulence of MCMV in vivo. These studies, along with studies of other viral mutants exhibiting similar phenotypes, will lead to identification of the viral determinants for optimal growth and virulence in vivo and will provide insights into how these determinants function in CMV pathogenesis and infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Edward Mocarski of Stanford University for helpful discussions and Michael Snyder of Yale University for providing the Tn3 transposon constructs and the E. coli strains for transposon shuttle mutagenesis.

M.L. is a recipient of the predoctoral dissertation fellowship of the State of California AIDS research program (D00-B-105). E.H. acknowledges fellowship support from the Biology Fellow program (University of California–Berkeley). F.L. is a Pew Scholar in Biomedical Sciences and a recipient of a Basil O'Connor Starter Scholar Research Award (March of Dimes National Birth Defects Foundation) and a Regents Junior Faculty Fellowship (University of California). This research was supported in part by a Chancellor's Special Initiative Grant Award (University of California–Berkeley).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldick C J, Jr, Shenk T. Proteins associated with purified human cytomegalovirus particles. J Virol. 1996;70:6097–6105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6097-6105.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boname J M, Chantler J K. Characterization of a strain of murine cytomegalovirus which fails to grow in the salivary glands of mice. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2021–2029. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borst E, Hahn G, Koszinowski U H, Messerle M. Cloning of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial chromosome in Escherichia coli: a new approach for construction of HCMV mutants. J Virol. 1999;73:8320–8329. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8320-8329.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britt W J, Alford C A. Cytomegalovirus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields Virology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 2493–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brune W, Menard C, Hobom U, Odenbreit S, Messerle M, Koszinowski U H. Rapid identification of essential and nonessential herpesvirus genes by direct transposon mutagenesis. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:360–364. doi: 10.1038/7914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns N, Grimwade B, Ross-Macdonald P B, Choi E Y, Finberg K, Roeder G S, Snyder M. Large-scale analysis of gene expression, protein localization, and gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1087–1105. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chee M S, Bankier A T, Beck S, Bohni R, Brown C M, Cerny R, Horsnell T, Hutchison C A, Kouzarides T, Martignetti J A. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;154:125–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J I, Seidel K E. Generation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and viral mutants from cosmid DNAs: VZV thymidylate synthetase is not essential for replication in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7376–7380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cranmer L D, Clark C L, Morello C S, Farrell H E, Rawlinson W D, Spector D H. Identification, analysis, and evolutionary relationships of the putative murine cytomegalovirus homologs of the human cytomegalovirus UL82 (pp71) and UL83 (pp65) matrix phosphoproteins. J Virol. 1996;70:7929–7939. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7929-7939.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham C, Davison A J. A cosmid-based system for constructing mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology. 1993;197:116–124. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dallas P B, Lyons P A, Hudson J B, Scalzo A A, Shellam G R. Identification and characterization of a murine cytomegalovirus gene with homology to the UL25 open reading frame of human cytomegalovirus. Virology. 1994;200:643–650. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delecluse H J, Hilsendegen T, Pich D, Zeidler R, Hammerschmidt W. Propagation and recovery of intact, infectious Epstein-Barr virus from prokaryotic to human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8245–8250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominguez G, Dambaugh T R, Stamey F R, Dewhurst S, Inoue N, Pellett P E. Human herpesvirus 6B genome sequence: coding content and comparison with human herpesvirus 6A. J Virol. 1999;73:8040–8052. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8040-8052.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler K B, Stagno S, Pass R F, Britt W J, Boll T J, Alford C A. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:663–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203053261003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallant J E, Moore R D, Richman D D, Keruly J, Chaisson R E. Incidence and natural history of cytomegalovirus disease in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease treated with zidovudine. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1223–1227. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gompels U A, Nicholas J, Lawrence G, Jones M, Thomson B J, Martin M E, Efstathiou S, Craxton M, Macaulay H A. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology. 1995;209:29–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greaves R F, Brown J M, Vieira J, Mocarski E S. Selectable insertion and deletion mutagenesis of the human cytomegalovirus genome using the Escherichia coli guanosine phosphoribosyl transferase (gpt) gene. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2151–2160. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grundy J E, Melief C J. Effect of Nu/Nu gene on genetically determined resistance to murine cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 1982;61:133–136. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-61-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson J B. The murine cytomegalovirus as a model for the study of viral pathogenesis and persistent infections. Arch Virol. 1979;62:1–29. doi: 10.1007/BF01314900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isegawa Y, Mukai T, Nakano K, Kagawa M, Chen J, Mori Y, Sunagawa T, Kawanishi K, Sashihara J, Hata A, Zou P, Kosuge H, Yamanishi K. Comparison of the complete DNA sequences of human herpesvirus 6 variants A and B. J Virol. 1999;73:8053–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8053-8063.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins F J, Casadaban M J, Roizman B. Application of the mini-Mu-phage for target-sequence-specific insertional mutagenesis of the herpes simplex virus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4773–4777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan M C. Latent infection and the elusive cytomegalovirus. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:205–215. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemble G, Duke G, Winter R, Spaete R. Defined large-scale alterations of the human cytomegalovirus genome constructed by cotransfection of overlapping cosmids. J Virol. 1996;70:2044–2048. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.2044-2048.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu F, Roizman B. The herpes simplex virus 1 gene encoding a protease also contains within its coding domain the gene encoding the more abundant substrate. J Virol. 1991;65:5149–5156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5149-5156.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F Y, Roizman B. The promoter, transcriptional unit, and coding sequence of herpes simplex virus 1 family 35 proteins are contained within and in frame with the UL26 open reading frame. J Virol. 1991;65:206–212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.206-212.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning W C, Stoddart C A, Lagenaur L A, Abenes G B, Mocarski E S. Cytomegalovirus determinant of replication in salivary glands. J Virol. 1992;66:3794–3802. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3794-3802.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Megaw A G, Rapaport D, Avidor B, Frenkel N, Davison A J. The DNA sequence of the RK strain of human herpesvirus 7. Virology. 1998;244:119–132. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Messerle M, Crnkovic I, Hammerschmidt W, Ziegler H, Koszinowski U H. Cloning and mutagenesis of a herpesvirus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14759–14763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mocarski E S. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields Virology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 2447–2492. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mocarski E S, Post L E, Roizman B. Molecular engineering of the herpes simplex virus genome: insertion of a second L-S junction into the genome causes additional genome inversions. Cell. 1980;22:243–255. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrello C S, Cranmer L D, Spector D H. In vivo replication, latency, and immunogenicity of murine cytomegalovirus mutants with deletions in the M83 and M84 genes, the putative homologs of human cytomegalovirus pp65 (UL83) J Virol. 1999;73:7678–7693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7678-7693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulligan R C, Berg P. Selection for animal cells that express the Escherichia coli gene coding for xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2072–2076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholas J. Determination and analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of human herpesvirus. J Virol. 1996;70:5975–5989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5975-5989.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okada M, Minamishima Y. The efficacy of biological response modifiers against murine cytomegalovirus infection in normal and immunodeficient mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1987;31:45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1987.tb03067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palella F J, Jr, Delaney K M, Moorman A C, Loveless M O, Fuhrer J, Satten G A, Aschman D J, Holmberg S D. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollock J L, Virgin H W., IV Latency, without persistence, of murine cytomegalovirus in the spleen and kidney. J Virol. 1995;69:1762–1768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1762-1768.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Post L E, Roizman B. A generalized technique for deletion of specific genes in large genomes: alpha gene 22 of herpes simplex virus 1 is not essential for growth. Cell. 1981;25:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rawlinson W D, Farrell H E, Barrell B G. Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1996;70:8833–8849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8833-8849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds R P, Rahija R J, Schenkman D I, Richter C B. Experimental murine cytomegalovirus infection in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1993;43:291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roizman B, Jenkins F J. Genetic engineering of novel genomes of large DNA viruses. Science. 1985;229:1208–1214. doi: 10.1126/science.2994215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roizman B, Sears A E. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields Virology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 2231–2296. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross-Macdonald P, Coelho P S, Roemer T, Agarwal S, Kumar A, Jansen R, Cheung K H, Sheehan A, Symoniatis D, Umansky L, Heidtman M, Nelson F K, Iwasaki H, Hager K, Gerstein M, Miller P, Roeder G S, Snyder M. Large-scale analysis of the yeast genome by transposon tagging and gene disruption. Nature. 1999;402:413–418. doi: 10.1038/46558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saeki Y, Ichikawa T, Saeki A, Chiocca E A, Tobler K, Ackermann M, Breakefield X O, Fraefel C. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA amplified as bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: rescue of replication-competent virus progeny and packaging of amplicon vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2787–2794. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seifert H S, Chen E Y, So M, Heffron F. Shuttle mutagenesis: a method of transposon mutagenesis for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:735–739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selik R M, Chu S Y, Ward J W. Trends in infectious diseases and cancers among persons dying of HIV infection in the United States from 1987 to 1992. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:933–936. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-12-199512150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selik R M, Karon J M, Ward J W. Effect of the human immunodeficiency virus epidemic on mortality from opportunistic infections in the United States in 1993. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:632–636. doi: 10.1086/514083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith G A, Enquist L W. Construction and transposon mutagenesis in Escherichia coli of a full-length infectious clone of pseudorabies virus, an alphaherpesvirus. J Virol. 1999;73:6405–6414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6405-6414.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith G A, Enquist L W. A self-recombining bacterial artificial chromosome and its application for analysis of herpesvirus pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4873–4878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080502497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stavropoulos T A, Strathdee C A. An enhanced packaging system for helper-dependent herpes simplex virus vectors. J Virol. 1998;72:7137–7143. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7137-7143.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomkinson B, Robertson E, Yalamanchili R, Longnecker R, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus recombinants from overlapping cosmid fragments. J Virol. 1993;67:7298–7306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7298-7306.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Zijl M, Quint W, Briaire J, de Rover T, Gielkens A, Berns A. Regeneration of herpesviruses from molecularly cloned subgenomic fragments. J Virol. 1988;62:2191–2195. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2191-2195.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vieira J, Farrell H E, Rawlinson W D, Mocarski E S. Genes in the HindIII J fragment of the murine cytomegalovirus genome are dispensable for growth in cultured cells: insertion mutagenesis with a lacZ/gpt cassette. J Virol. 1994;68:4837–4846. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4837-4846.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vink C, Beuken E, Bruggeman C A. Complete DNA sequence of the rat cytomegalovirus genome. J Virol. 2000;74:7656–7665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7656-7665.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagner M, Jonjic S, Koszinowski U H, Messerle M. Systematic excison of vector sequences from the BAC-cloned herpesvirus genome during virus reconstitution. J Virol. 1999;73:7056–7060. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.7056-7060.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weber P C, Levine M, Glorioso J C. Rapid identification of nonessential genes of herpes simplex virus type 1 by Tn5 mutagenesis. Science. 1987;236:576–579. doi: 10.1126/science.3033824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhan X, Abenes G, Lee M, VonReis I, Kittinunvorakoon C, Ross-Macdonald P, Snyder M, Liu F. Mutagenesis of murine cytomegalovirus using a Tn3-based transposon. Virology. 2000;266:264–274. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhan X, Lee M, Xiao J, Liu F. Construction and characterization of murine cytomegaloviruses that contain a transposon insertion at open reading frames m09 and M83. J Virol. 2000;74:7411–7421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7411-7421.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]