Abstract

Background/Objective:

The spectrum and incidence of influenza-associated neuropsychiatric complications are not well-characterized. The objective of this study was to define the incidence of specific neurologic and psychiatric complications associated with influenza in children and adolescents.

Methods:

We assembled a retrospective cohort of children 5–17 years with an outpatient or emergency department ICD-10 influenza diagnosis and enrolled in Tennessee Medicaid from 2016–2020. Serious neurologic or psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization were identified using a validated algorithm. Incidence rates of complications were expressed per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza and 95% CIs were reported.

Results:

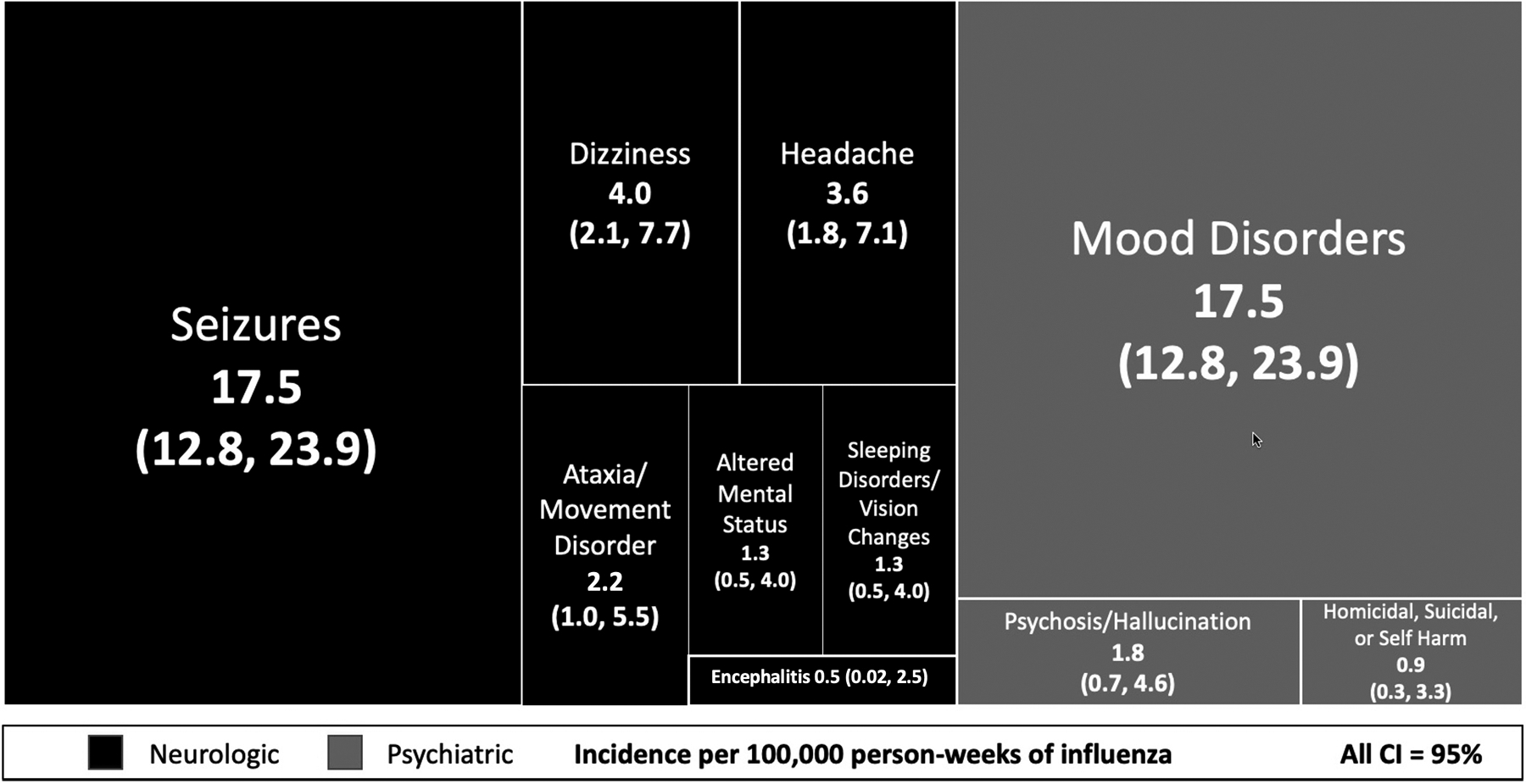

A total of 156,661 influenza encounters (median age of 9.3 years) were included. The overall incidence of neurologic complications was 30.5 (95% CI 24.0–38.6) per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza, and 1880.9 (95% CI 971.9–3285.5) among children with an underlying neurologic comorbidity. The distribution of antiviral treatment was similar among those with and without neurologic or psychiatric complications. The overall incidence of psychiatric complications was 20.2 (95% CI 15.1–27.0) per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza, and 111.8 (95% CI 77.9–155.5) among children with an underlying psychiatric comorbidity. Seizures (17.5; 95% CI 12.8–23.9) were the most common neurologic complications whereas encephalitis (0.5; 95% CI 0.02–2.5) was rare. Mood disorders (17.5, 95% CI, 12.8–23.9) were the most frequent psychiatric complications and self-harm events (0.9, 95% CI 0.3–3.3) were least common.

Discussion:

Our findings reveal that the incidence of neuropsychiatric complications of influenza is overall low; however, the incidence among children with underlying neurologic or psychiatric conditions is significantly higher than children without these conditions.

Keywords: influenza, neurologic, encephalitis, psychiatric, self-harm

INTRODUCTION

Influenza is a common diagnosis in children and is associated with numerous complications including pneumonia, hospitalization, and death.1 Neurologic complications associated with influenza in children include seizures, altered mental status, and encephalitis.2 These are more common in children with underlying medical conditions, but can also affect previously healthy children.3,4 These complications, especially influenza-associated encephalitis, may be severe with the potential for significant morbidity and mortality in children3. Although influenza has been associated with increased risk of suicide and other psychiatric complications among adults,5 psychiatric complications associated with influenza in children remain understudied. Influenza is a vaccine-preventable illness and characterization of complications of the virus and those who are at increased risk could aid in targeted education and vaccination efforts in the pediatric population.

The overall incidence of influenza-associated neuropsychiatric complications requiring hospitalization was recently reported6; however, that study did not provide granular information on specific neurologic complications such as encephalitis or seizures, or on psychiatric complications such as self-harm behaviors or psychosis. A better understanding of the specific neurologic and psychiatric complications of influenza would aid providers and families in evaluating the risks and benefits of the prevention and treatment of influenza. The objective of this study is to report the incidence of specific neurologic and psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization associated with influenza in children.

METHODS

Study Design

We nested our analyses within a retrospective cohort of children 5–17 years of age with a diagnosis influenza and enrolled in Tennessee Medicaid during the 2016–2020 influenza seasons.6 The Tennessee Medicaid database contains administrative, pharmacy, and clinical data on over 13 million children, including more than half of all children and adolescents in the state of Tennessee. Children < 5 were excluded because psychiatric diagnoses are difficult to characterize in young children.

Influenza Exposure

Outpatient (clinic, urgent care and emergency department) influenza infections were identified using ICD-10 diagnoses codes for influenza.7 An outpatient clinic emergency department ICD-10 influenza diagnosis are highly predictive of test-positive influenza (outpatient positive predictive value >85%, emergency department >90%) during the study period.8,9 To further mitigate misclassification of influenza infections, each influenza season was defined by the 13 consecutive weeks including the maximum number of laboratory-confirmed influenza cases in Tennessee.10 Seasonal influenza activity in the state of Tennessee was obtained from the CDC Flu Activity & Surveillance program.11

Outcome

The primary outcome of influenza-associated serious neurologic or psychiatric complications was defined as an influenza-associated hospitalization with a neurologic or psychiatric diagnosis and identified using a validated algorithm.7 Complications were categorized as either neurologic (seizures, altered mental status, encephalitis, ataxia/movement disorders, dizziness, headache, sleeping disorders/vision changes) or psychiatric (homicidal/suicidal ideation or self-harm, mood disorders, or psychosis/hallucinations).7 Febrile seizures were excluded as these are generally self-limiting in children, even if they require hospitalization, and are uncommon in children older than 6 years of age.12 Individuals were permitted to contribute person-time to more than one influenza season. Within each season, however, an individual’s follow-up began on the date of influenza diagnosis and was censored at the earliest of 10 days, loss of enrolment in Tennessee Medicaid, end of influenza season, death, or defined outcome event. Therefore, an individual with a serious neurologic or psychiatric complication would have their follow-up censored at the neurologic or psychiatric hospitalization date.

Statistical Analysis

Incidence rates of serious neurologic and psychiatric complications were calculated by dividing the number of complications by the total influenza person-time and expressed per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza. We reported 95% Poisson Confidence Intervals using exact method. Person-weeks was used to report the incidence as influenza illness duration is typically 7–10 days and this timeframe is easily interpretable. Analyses were conducted using R, version 4.3.2

RESULTS

A total of 156,661 influenza encounters among 134,379 unique patients (median age of 9.3 years) were included. Among those with an influenza diagnosis, 51% were male and 14% had an underlying neurologic or psychiatric co-morbidity (Table 1). Influenza-associated neurologic or psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization most often occurred in adolescents (53% 12–17 years), those without underlying complex chronic conditions (80%), and in those with underlying neurologic or psychiatric comorbidities (60%). Two-thirds of the total cohort (68%) received antiviral treatment, with a similar distribution among those with and without neurologic or psychiatric complications.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| Overall | No Neurologic or Psychiatric Complication | Neurologic or Psychiatric Complication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza Diagnosis | N | 156661 | 156548 | 113 |

| Age | Median [IQR] | 9.32 [6.91, 12.63] | 9.32 [6.91, 12.63] | 12.36 [9.27, 15.17] |

| 5–11 years | 110675 (71%) | 110622 (71%) | 53 (47%) | |

| 12–17 years | 45986 (29%) | 45926 (29%) | 60 (53%) | |

| Sex | Male | 80016 (51%) | 79960 (51%) | 56 (50%) |

| Race | White | 96890 (62%) | 96839 (62%) | 51 (45%) |

| Black | 23907 (15%) | 23893 (15%) | 14 (12%) | |

| American Indian | 304 (<1%) | 304 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian | 1626 (1%) | 1626 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 33934 (22%) | 33886 (22%) | 48 (43%) | |

| Number of Complex Chronic Conditions | Any | 3075 (2%) | 3052 (2%) | 23 (20%) |

| 0 | 153586 (98%) | 153496 (98%) | 90 (80%) | |

| 1 | 2857 (2%) | 2840 (2%) | 17 (15%) | |

| 2–3 | 215 (<1%) | 209 (<1%) | 6 (5%) | |

| >3 | 3 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) | 0 (0) | |

| Neuropsychiatric Comorbidity | Any | 22213 (14%) | 22145 (14%) | 68 (60%) |

| Psychiatric | 22005 (14%) | 21939 (14%) | 66 (58%) | |

| Neurologic | 460 (<1%) | 446 (<1%) | 14 (12%) | |

| Antiviral Medication | Oseltamivir | 104618 (67%) | 104541 (67%) | 77 (68%) |

| Zanamavir | 10 (<1%) | 10 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Baloxavir | 149 (<1%) | 149 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Risk Factor for Influenza Complications | Children with Chronic conditions | 3075 (2%) | 3052 (2%) | 23 (20%) |

| Asthma | 11435 (7%) | 11417 (7%) | 18 (16%) | |

| Immunosuppressed Children | 13 (<1%) | 13 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Pregnancy or Post-partum | 16 (<1%) | 16 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Obesity | 4576 (3%) | 4566 (3%) | 10 (9%) | |

| Neurologic Co-morbidity | 460 (<1%) | 446 (<1%) | 14 (12%) | |

| Location of Influenza Diagnosis | ED | 33767 (22%) | 33712 (22%) | 55 (49%) |

| Outpatient Office | 122894 (78%) | 122836 (78%) | 58 (51%) | |

| Influenza Season | 2016–2017 | 25469 (16%) | 25453 (16%) | 16 (14%) |

| 2017–2018 | 40927 (26%) | 40886 (26%) | 41 (36%) | |

| 2018–2019 | 40173 (26%) | 40152 (26%) | 21 (19%) | |

| 2019–2020 | 50092 (32%) | 50057 (32%) | 35 (31%) |

Neurologic Complications

A total of 68 neurologic complications were reported. The incidence of influenza-associated neurologic complications was 30.5 (95% CI 24.0–38.6) per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza, and 1880.9 (95% CI 971.9–3285.5) per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza among children with an underlying neurologic comorbidity. The most common neurologic complication was seizure (17.5; 95% CI 12.8–23.9), while the least common was encephalitis (0.5; 95% CI 0.02–2.5). Dizziness (4.0, 95% CI 2.1–7.7), headache (3.6, 95% CI 1.8–7.1), ataxia/movement disorder (2.2, 95% CI 1.0–5.5), altered mental status (1.3, 95% CI 0.5–4.0), and sleeping disorders/vision changes (1.3, 95% CI 0.5–4.0) were also reported (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Incidence of Influenza Associated Neurologic and Psychiatric Complications.

Tree map chart of the distribution of pediatric influenza-associated serious neuropsychiatric complications requiring hospitalization. The tree map chart provides a hierarchical visualization of the relative incidence quantities. The sizes of the rectangles are on a relative scale from largest category incidence (seizures) to the smallest (encephalitis).

Of note, mood disorders include anxiety or stress disorders.

Psychiatric Complications

There were a total of 45 psychiatric complications. The incidence of influenza-associated psychiatric complications was 20.2 (95% CI 15.1–27.0) per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza. The incidence was 111.8 (95% CI 77.9–155.5) per 100,000 person-weeks of influenza among children with an underlying psychiatric comorbidity. The most common psychiatric complication was mood disorder (17.5, 95% CI, 12.8–23.9), and self-harm events (0.9, 95% CI 0.3–3.3) were least common (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of a statewide, population-based, Medicaid cohort, the incidence of neurologic or psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization in children with influenza was low. The incidence of neurologic complications requiring hospitalization was slightly higher than psychiatric complications requiring hospitalizations, and seizures and mood disorders were the most common in each domain, respectively. The incidence of these complications requiring hospitalization is higher in children with underlying neurologic and psychiatric comorbidities, which is consistent with other reports in the literature.2,13 To our knowledge, this is the first study to report population-based incidence of influenza-associated neurologic and psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization in U.S. children ages 5–17.3–5,13,14

Studies conducted in Australia and Japan also report a low incidence of neurologic complications in children with influenza.4,14 A single center study performed in the U.S. reported a higher incidence of influenza-associated neurologic complications (18%) in children with inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of influenza.15 The incidence among our population of children is lower, likely due to differences in study design and population characteristics. The previous study only included children evaluated at a quaternary care center in Colorado and included inpatient influenza diagnosis. Our study included children and adolescents throughout the state of Tennessee and excluded inpatient influenza diagnosis. The population in our study likely represents a healthier cohort than the population of patients evaluated in the study from Colorado.15

Similar to our findings, studies out of Australia and France identify seizures as the most common influenza-associated neurologic complication.3 Seizures, especially those progressing to status epilepticus, can result in long-term morbidity in the pediatric population. Cognitive impairment, development of significant anxiety or mood disorder, and other medical comorbidities are associated with seizures in children.11 Additionally, seizures in the pediatric population contribute significantly to healthcare costs as the surrounding workup is often very comprehensive.16

Encephalitis, especially acute necrotizing encephalitis, is a severe neurologic complication of influenza which can progress rapidly and lead to death or serious neurologic impairment.4 Our study, along with Japanese and Australian studies, report that influenza-associated encephalitis in children is uncommon. However, due to the association of neurologic complication with poor outcomes in children with influenza, including the need for ICU-level care, significant neurologic impairment, and death,4,14 further study to determine the role of vaccination efforts and antiviral treatment in the prevention of these complication is warranted.

There are few reports of psychiatric complications related to influenza diagnosis in children. A 2020 Korean study documented a low incidence of serious psychiatric complications associated with influenza among children between 8–18 years of age13. In concordance with our findings, risk was increased in those with underlying psychiatric conditions. Additionally, this study revealed no significant difference in psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization between children who received oseltamivir and those who did not, a significant finding given the oseltamivir black box warning for neuropsychiatric events. We also report similar incidences of neurologic and psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization among those with and without oseltamivir treatment, though our study was not specifically designed to assess the association between influenza, antivirals, and neurologic or psychiatric complications.

An alternative Korean study examined suicide rates associated with influenza-like illnesses in adults and found a positive association with suicide-related mortality.5 The combined incidence of psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization related to influenza in our population is overall low; however, this is not insignificant when considering the morbidity and mortality that are associated with severe psychiatric complications including self-harm and suicide.17 Our study, and the overall dearth of information regarding psychiatric complications in the setting of pediatric influenza, emphasizes the importance of further investigation into psychiatric complications of influenza.

Strengths of this population-based study include the use of a strictly-defined influenza season and a validated outcome measurement, each of which serves to minimize misclassification of our primary exposure and outcome. Limitations include lack of information on influenza vaccination status and laboratory-confirmation of influenza infection. Our study included school-age children and adolescents enrolled in Tennessee Medicaid and may not be representative of other populations.

Our findings reveal that neurologic and psychiatric complications related to influenza in the pediatric population are uncommon but can be severe and result in hospitalization.3,17 These data emphasize the importance of awareness and recognition of neuropsychiatric complications of influenza in children, particularly in children with underlying neurologic or psychiatric comorbid conditions. Better recognition of these influenza-associated complications can lead to appropriate treatment along with targeted education in the clinical and public health settings. These findings emphasize the importance of mitigating influenza through prevention and vaccination efforts to prevent potentially life-altering influenza complications.

Funding Disclosure:

Research reported in this publication was supported the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers K23 AI168496 (Dr. Antoon) and K24 AI148459 (Dr. Grijalva). The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosures:

Dr. Antoon reported serving on a scientific advisory board for AstraZeneca outside of the submitted work. Dr. Williams reported receiving nonfinancial support for procalcitonin assays from Biomérieux outside the submitted work. Dr. Zhu reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) during the conduct of the study. Dr. Grijalva reported receiving grants from the CDC, the US Food and Drug Administration, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Syneos and receiving personal fees from Merck outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolf RM, Antoon JW. Influenza in Children and Adolescents: Epidemiology, Management, and Prevention. Pediatr Rev. Nov 1 2023;44(11):605–617. doi: 10.1542/pir.2023-005962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoon JW, Hall M, Herndon A, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Influenza-Associated Neurologic Complications in Children. J Pediatr. Dec 2021;239:32–38 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.06.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goetz V, Yang DD, Abid H, et al. Neurological features related to influenza virus in the pediatric population: a 3-year monocentric retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr. Jun 2023;182(6):2615–2624. doi: 10.1007/s00431-023-04901-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnelley E, Teutsch S, Zurynski Y, et al. Severe Influenza-Associated Neurological Disease in Australian Children: Seasonal Population-Based Surveillance 2008–2018. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. Dec 28 2022;11(12):533–540. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piac069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung SJ, Lim SS, Yoon JH. Fluctuations in influenza-like illness epidemics and suicide mortality: A time-series regression of 13-year mortality data in South Korea. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0244596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoon JW, Williams DJ, Bruce J, et al. Population-Based Incidence of Influenza-Associated Serious Neuropsychiatric Events in Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. Sep 1 2023;177(9):967–969. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.2304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antoon JW, Feinstein JA, Grijalva CG, et al. Identifying Acute Neuropsychiatric Events in Children and Adolescents. Hosp Pediatr. May 1 2022;12(5):e152–e160. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2021-006329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benack K, Nyandege A, Nonnenmacher E, et al. Validity of ICD-10-based algorithms to identify patients with influenza in inpatient and outpatient settings. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. Apr 2024;33(4):e5788. doi: 10.1002/pds.5788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoon JW ST, Amarin JZ, et al. Accuracy of Influenza ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes in Identifying Influenza Illness in Children. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(4): e248255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Flu View. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm Date accessed: May 4, 2023.

- 11.Prevention UCfDCa. Weekly U.S. influenza surveillance report. https://www-cdc-gov.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/flu/weekly/index.htm

- 12.Biltz S, Speltz L. Febrile Seizures. Pediatr Ann. Oct 2023;52(10):e388–e393. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20230829-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huh K, Kang M, Shin DH, Hong J, Jung J. Oseltamivir and the Risk of Neuropsychiatric Events: A National, Population-based Study. Clin Infect Dis. Dec 3 2020;71(9):e409–e414. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuno H, Yahata Y, Tanaka-Taya K, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Influenza-Associated Encephalopathy Cases Among Children and Adults in Japan, 2010–2015. Clin Infect Dis. Jun 1 2018;66(12):1831–1837. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao S, Martin J, Ahearn MA, et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Influenza A(H3N2) Infection in Children During the 2016–2017 Season. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. Feb 28 2020;9(1):71–74. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piy130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine A, Wirrell EC. Seizures in Children. Pediatr Rev. Jul 2020;41(7):321–347. doi: 10.1542/pir.2019-0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hua LL, Lee J, Rahmandar MH, et al. Suicide and Suicide Risk in Adolescents. Pediatrics. Jan 1 2024;153(1)doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-064800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]